Abstract

Objective: Earlier smaller studies have shown associations between child and adolescent psychiatric disorders and schizophrenia. Particularly, attention-deficit/hyperactivity-disorder and autism have been linked with schizophrenia. However, large-scale prospective studies have been lacking. We, therefore, conducted the first large-scale study on the association between a broad spectrum of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders and the risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia. Methods: Danish nationwide registers were linked to establish a cohort consisting of all persons born during 1990–2000 and the cohort was followed until December 31, 2012. Data were analyzed using survival analyses and adjusted for calendar year, age, and sex. Results: A total of 25138 individuals with child and adolescent psychiatric disorders were identified, out of which 1232 individuals were subsequently diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders was highly elevated, particularly within the first year after onset of the child and adolescent psychiatric disorder, and remained significantly elevated >5 years with an incidence rate ratio of 4.93 (95% confidence interval: 4.37–5.54).We utilized the cumulated incidences and found that among persons diagnosed with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder between the ages 0–13 years and 14–17 years, 1.68% and 8.74 %, respectively, will be diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder <8 years after onset of the child and adolescent psychiatric disorder. Conclusions: The risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders after a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder was significantly increased particularly in the short term but also in the long-term period.

Key words: epidemiology, psychiatry, cohort study

Introduction

Adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders often have comorbid symptoms overlapping with some of the psychiatric disorders usually diagnosed in childhood, such as inattention, restlessness, irritability, anxiety, and depression. These symptoms resemble several of the negative symptoms in schizophrenia and may, therefore, lead to other psychiatric diagnoses in childhood and adolescence before eventually being diagnosed with schizophrenia.1,2 Furthermore, schizophrenia and some child psychiatric disorders may also have shared risk factors, such as obstetrical complications3–5 and risk-genes,2,6–8 which might explain some of the observed comorbidity. In addition, autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity-disorder (ADHD) and schizophrenia are all hypothesized to be of a neurodevelopmental origin.5,6 Furthermore, chronic neuroinflammation might be a common risk factor for both child and adolescent psychiatric disorders and later schizophrenia.9 The first manifestation of schizophrenia might be nonpsychotic disorders or symptoms as part of the prodromal phase or as steps on the pathway to schizophrenia,10 and could be present already in childhood. Furthermore, it has been shown that many individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia initially have been diagnosed with a child psychiatric disorder.11 However, little is known about which psychiatric disorders precede the development of psychosis and large-scale prospective studies are lacking.

Some of the earlier studies have been limited in sample size and have mostly studied a single psychiatric disorder in the childhood or adolescence as the exposure; primarily ADHD or autism.11–16 Attention-deficit/hyperactivity-disorder was in two separate studies found to be associated with a 4-fold increased risk of schizophrenia.11,13 Furthermore, two long-term follow-up studies found that 3.4% of individuals with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder were later diagnosed with schizophrenia17 and that almost half of the individuals with a schizophreniform disorder in adulthood had been diagnosed earlier with a psychiatric disorder in the childhood.11 In addition, earlier studies have observed a tendency towards developing schizophrenia with an earlier age of onset if having a prior child and adolescent psychiatric disorder.12,18 This might point to a shared neurodevelopmental pathway between child psychiatric disorders and schizophrenia. Regarding the remaining child and adolescent psychiatric disorders and the association with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, the knowledge is still very sparse, and primarily case-reports and small-scale studies have been reported.17,19–21

Duration of untreated psychosis may have a negative impact on the prognosis for individuals with schizophrenia.22 Therefore, knowledge about the risk of a subsequent diagnosis of schizophrenia following a psychiatric disorder in the childhood and adolescence might lead to earlier diagnosis and interventions, which can possibly lead to a better prognosis for individuals with schizophrenia.22,23 The prior research has primarily been regarding the possible association between ADHD or autism and the subsequent diagnosis of schizophrenia. We, therefore, undertook a comprehensive nationwide study of the risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders following a broad spectrum of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders based on the entire Danish population.

Methods

Study Population

The Danish Civil Registration System was established in 1968,24 where all people alive and living in Denmark were registered. Among other variables, it includes information on personal identification number of all individuals, gender, date and place of birth, personal identifiers of parents, and provides continuously updated information on vital status. The personal identification number is used in all national registers enabling accurate linkage. Our study population included all persons born in Denmark between January 1, 1990 and December 31, 2000, who were alive and resided in Denmark at their 10th birthday, and whose both parents were born in Denmark, thereby effectively controlling for the increased risk of psychiatric disorder associated with immigration.25

Assessment of Psychiatric Illness

Persons within the study cohort, their parents, and siblings were linked through their personal identifier to the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register26 and the Danish National Patient Register27 to obtain information of psychiatric illness. The Danish Psychiatric Central Register was digitalized in 1969 and contains data on all admissions to Danish psychiatric inpatient facilities. The Danish National Patient Register was established in 1977 and contains data on all admissions to public hospitals in Denmark. In both registers, information on outpatient visits was included from 1995 and onwards. From 1969 to 1993, the diagnostic system used was the Danish modification of International Classification of Diseases, 8th revision (ICD-8),28 and from 1994, it was the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Diagnostic Criteria for Research (ICD-10-DCR).29 Cohort members were classified with a psychiatric disorder if they had been admitted to in- or outpatient care at a psychiatric or somatic hospital. The psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence considered are shown in online supplementary table 1 along with the ICD-10 codes. For each psychiatric disorder, the date of onset was defined as the first day of the first contact (in- or outpatient) given the diagnosis of interest. Multiple disorders were recorded if developed by the individual. Because some children with psychiatric disorders are treated in somatic departments, we also included cases from the National Patient Register in the analyses. Parents and siblings were classified as having a history of a psychiatric disorder if they had a contact at a psychiatric or somatic hospital and were given a psychiatric diagnosis (ICD8: 290–315, ICD10: F00-F99).

Study Design and Statistical Analyses

Individuals were followed from their 10th birthday until onset of schizophrenia spectrum disorder, death, emigration from Denmark, or December 31, 2012, whichever came first.

The incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for schizophrenia spectrum disorders were estimated by log-linear Poisson regression.30,31 All IRRs were adjusted for calendar period, age, gender, and its interaction with age.32 Age and calendar period were treated as time-dependent variables,33 whereas all other variables were treated as variables independent of time. Potential confounders included history of psychiatric disorder in a parent or sibling,34 obstetrical complications, such as birth weight, gestational age, Apgar score, and parental age. P values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were based on likelihood ratio tests.33 The adjusted-score test35 suggested that the regression models were not subject to overdispersion.

The absolute risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders following onset with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder were estimated using competing risk survival analyses to account for the fact that persons simultaneously are at risk of a psychiatric disorder, dying, or emigrating from Denmark. Ignoring censoring from emigration and/or death will bias the estimated cumulative incidences upwards.36 These analyses were performed for each child and adolescent psychiatric disorder and were subdivided by age of onset of the child and adolescent psychiatric disorder. The cumulative incidence measures the percentages of persons in the population who will be treated for the disorder before a given point in time. To estimate the cumulative incidence for persons without child and adolescent psychiatric disorders, we adopted a slightly alternative strategy. For each person with any child and adolescent psychiatric disorder, we randomly selected five persons of the same date of birth who had no history of any child psychiatric disorder (time matched). Using the strategy described earlier, we followed up this healthy population to provide estimates of cumulative incidences among persons with no history of child psychiatric disorders.

Results

The study population consisted of 603348 persons born in Denmark in the years 1990–2000, who were followed from their 10th birthday until the end of 2012. Overall, the cohort was followed for a total of 4.54 million person-years. During this period, 25138 individuals were diagnosed with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder, and 3085 members were diagnosed for the first time with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. A total of 1232 individuals were diagnosed with both a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder and a schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

Table 1 displays the absolute risks of schizophrenia spectrum disorders by age at onset and numbers of years after a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder. Among individuals who had their first diagnosis with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder at age 0–13 years, we estimated that 1.68% was diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder <8 years after onset of the child psychiatric disorder. Among individuals with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder at age 14–17 years, we estimated that 8.74% were diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder <8 years after onset of the child psychiatric disorder.

Table 1.

Absolute Risks of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders by Age at Onset and Numbers of Years After a Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Disorder

| Age at Onset of Childhood Psychiatric Disorder | Cumulative Incidences by the Number of Years After Onset with a Childhood Psychiatric Disorder | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Year | 2 Years | 5 Years | 8 Years | 10 Years | ||

| Any child and adolescent psychiatric disorder | 0–13 Years | 0.33 (0.27–0.40) | 0.49 (0.41–0.57) | 0.97 (0.86–1.09) | 1.68 (1.52–1.86) | 2.22 (2.02–2.44) |

| Any child and adolescent psychiatric disorder | 14–17 Years | 2.47 (2.20–2.78) | 3.60 (3.26–3.97) | 6.90 (6.31–7.55) | 8.74 (7.84–9.73) | NA |

| No child and adolescent psychiatric disorder | 0–13 Years | 0.01 (0.00–0.01) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | 0.11 (0.09–0.13) | 0.29 (0.26–0.33) | 0.46 (0.41–0.50) |

| No child and adolescent psychiatric disorder | 14–17 Years | 0.07 (0.06–0.10) | 0.21 (0.17–0.25) | 0.74 (0.65–0.86) | 1.18 (0.95–1.47) | NA |

Note. The cumulative incidence measure the percentage of persons in the population who will be diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder before some point in time, measured as the number of years after onset of a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder.

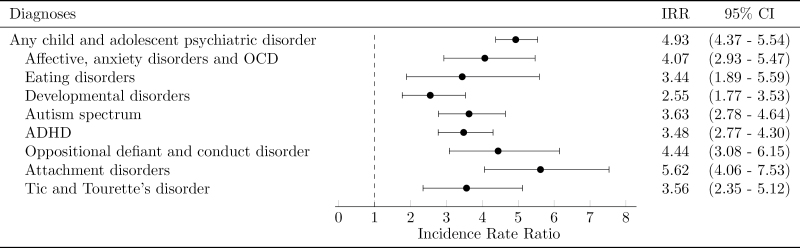

The risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders was found to be highest within the first year after the diagnosis of any child and adolescent psychiatric disorder with an IRR of 41.32 (95% CI: 36.83–46.25) and was gradually diminishing in the subsequent years (table 2). The risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders within the first year after exposure was found to be highly elevated in the group diagnosed with anxiety disorders, affective disorders, or OCD with an IRR of 51.67 (95% CI: 45.41–58.52). For this and all of the remaining groups of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders, the risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders decreased with increasing number of years after onset of the child and adolescent psychiatric disorder, but remained highly elevated 5 years after onset (table 2, figure 1).

Table 2.

Risk of Schizophrenia by Time Since First Childhood Psychiatric Disorder

| Diagnoses | Total Cases | 0–1 Years | 1–2 Years | 2–5 Years | 5+ Years | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | IRR | CI | Cases | IRR | CI | Cases | IRR | CI | Cases | IRR | CI | ||

| Any child and adolescent psychiatric disorders | 1232 | 456 | 41.32 | 36.83–46.25 | 148 | 14.53 | 12.22–17.13 | 297 | 9.59 | 8.46–10.82 | 331 | 4.93 | 4.37–5.54 |

| Affective/anxiety spectrum and OCD | 577 | 285 | 51.67 | 45.41–58.52 | 105 | 18.55 | 15.14–22.47 | 146 | 9.85 | 8.29–11.61 | 41 | 4.07 | 2.93–5.47 |

| Eating disorders | 109 | 35 | 15.12 | 10.60–20.81 | 28 | 12.41 | 8.33–17.66 | 33 | 5.92 | 4.11–8.21 | 13 | 3.44 | 1.89–5.59 |

| Developmental disorders | 55 | 6 | 7.99 | 3.17–16.23 | 9 | 10.59 | 5.08–19.12 | 7 | 2.24 | 0.96–4.34 | 33 | 2.55 | 1.77–3.53 |

| Autism spectrum | 186 | 44 | 19.40 | 14.16–25.82 | 30 | 11.90 | 8.11–16.74 | 51 | 6.86 | 5.13–8.95 | 61 | 3.63 | 2.78–4.64 |

| Attention-deficit/ hyperactivity-disorder | 230 | 47 | 11.11 | 8.20–14.66 | 25 | 5.28 | 3.46–7.64 | 74 | 5.40 | 4.25–6.76 | 84 | 3.48 | 2.77–4.30 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder | 78 | 17 | 26.26 | 15.64–40.90 | 10 | 12.60 | 6.31–22.14 | 18 | 6.44 | 3.90–9.92 | 33 | 4.44 | 3.08–6.15 |

| Attachment disorders | 85 | 15 | 28.07 | 16.12–44.87 | 9 | 14.90 | 7.15–26.91 | 20 | 9.44 | 5.88–14.24 | 41 | 5.62 | 4.06–7.53 |

| Tic and Tourette’s disorder | 61 | 7 | 12.52 | 5.37–24.30 | 11 | 15.33 | 7.94–26.33 | 19 | 6.55 | 4.02–9.98 | 24 | 3.56 | 2.35–5.12 |

Note. IRR, incidence rate ratio; CI, confidence interval. Estimates were adjusted for calendar year, age, gender and its interaction with age. Significant findings are mentioned in bold.

Fig. 1.

Risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders >5 years after onset of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders.

For the group with delayed onset of schizophrenia spectrum disorders; ie, >5 years after onset with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder, the risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders are displayed in table 3. When adjusting the estimates for psychiatric family history, a slight decrease was observed from an IRR of 4.93 (95% CI: 4.37–5.54) to an IRR of 3.98 (95% CI: 3.58–4.49). In the fully adjusted model, which had additionally adjustments for birth weight, gestational age, Apgar score, and parental age, the estimates were still significantly elevated with an IRR of 3.87 (95% CI: 3.43–4.36) for children and adolescents with any psychiatric disorder. The same pattern was observed for the disorders when considered individually.

Table 3.

Long-Term Consequences of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Disorders on the Risk of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders >5 Years After the First Diagnosis

| Diagnoses | Cases | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | CI | IRR | CI | IRR | CI | ||

| Any child and adolescent psychiatric disorders | 331 | 4.93 | 4.37–5.54 | 3.98 | 3.58–4.49 | 3.87 | 3.43–4.36 |

| Affective, anxiety spectrum and OCD | 41 | 4.07 | 2.93–5.47 | 3.25 | 2.34–4.37 | 3.22 | 2.32–4.34 |

| Eating disorders | 13 | 3.44 | 1.89–5.59 | 2.85 | 1.56–4.71 | 2.83 | 1.55–4.68 |

| Developmental disorders | 33 | 2.55 | 1.77–3.53 | 1.96 | 1.36–2.72 | 1.92 | 1.33–2.66 |

| Autism spectrum | 61 | 3.63 | 2.78–4.64 | 2.83 | 2.17–3.62 | 2.78 | 2.13–3.55 |

| ADHD | 84 | 3.48 | 2.77–4.30 | 2.56 | 2.04–3.17 | 2.43 | 1.93–3.01 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder | 33 | 4.44 | 3.08–6.15 | 2.99 | 2.07–4.14 | 2.83 | 1.96–3.92 |

| Attachment disorders | 41 | 5.62 | 4.06–7.53 | 2.78 | 2.00–3.74 | 2.59 | 1.87–3.50 |

| Tic and Tourette’s disorder | 24 | 3.56 | 2.35–5.12 | 2.90 | 1.92–4.18 | 2.84 | 1.88–4.09 |

Note: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity-disorder; the abbreviations IRR and CI are explained in notes section of Table 2. Model 1—Adjusted for calendar period, age, and gender and it’s interaction with age. Model 2—Adjusted for calendar period, age, gender and it’s interaction with age, and history of mental illness in a parent or sibling. Model 3—Fully adjusted model; Adjusted for calendar period, age, gender and it’s interaction with age, history of mental illness in a parent or sibling, birth weight, gestational age, Apgar score at 5 min and parental age at time of child’s birth. Significant findings are mentioned in bold.

Individuals with onset of child psychiatric disorders >10 years had the highest risk of later being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders when compared with individuals with onset <10 years, and both groups had higher risk than those without a diagnosed child psychiatric disorder. However, when mutually adjusting for age at onset with the exposure diagnosis and time since this diagnosis with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder, age at onset no longer had any effect on the risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (P = .19) (table 4). Furthermore, no evidence for interaction with age at diagnosis of the child and adolescent psychiatric disorders was found (P = .056).

Table 4.

Risk of Schizophrenia by Time Since Any Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Disorder and Age at Onset

| Age at Childhood Psychiatric Diagnosis | <1 Year | 1 Year | 2–4 Years | >5 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | CI | IRR | CI | IRR | CI | IRR | CI | |

| 0–4 years | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4.70 | 3.18–6.66 |

| 5–9 years | — | — | — | — | 12.86 | 8.59–18.53 | 4.93 | 4.20–5.74 |

| 10–14 years | 52.55 | 43.43–63.19 | 17.30 | 13.21–22.24 | 9.29 | 7.70–11.11 | 4.75 | 3.88–5.74 |

| 15+ | 36.62 | 31.71–42.13 | 13.21 | 10.51–16.37 | 9.34 | 7.79–11.10 | 6.09 | 3.71–9.39 |

Note: The abbreviation IRR and CI are explained in notes section of Table 2. When mutually adjusting for age at onset with the exposure diagnosis and time since this diagnosis with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder, age at onset no longer had any effect on the risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (P =.19).

Sensitivity analyses revealed the same significantly elevated risk for being diagnosed with a narrow definition of schizophrenia (ICD-10: F20) as for the broader diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (ICD-10: F20-29) with an IRR of 5.20 (95% CI: 4.36–6.16) in the time period >5 years after the initial diagnosis with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder.

Excluding persons with a history of substance abuse (ICD-10: F10-19) had no influence on the findings presented.

Discussion

This national cohort study is the first large-scale study on the association between a broad spectrum of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders and the risk of later being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. We found that being diagnosed with any child or adolescent psychiatric disorder increased the risk significantly for later being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders was highly elevated, particularly in the first year after the child psychiatric disorder was diagnosed, and remained clearly elevated until the end of follow-up for all studied child psychiatric disorders. We utilized the cumulated incidences and found that among persons diagnosed with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder in the age 0–13 years and those in the age 14–17 years, 1.68% and 8.74%, respectively, will be diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder <8 years after onset of the child and adolescent psychiatric disorder.

Our findings, showing a highly increased risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders after a diagnosis with a childhood psychiatric disorder, strongly support the findings from earlier smaller studies.11,13,17 The association between child psychiatric disorders and the risk of later being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders could be in part due to co-occurrence of the disorders or schizophrenia symptoms resembling other psychiatric disorders. The schizophrenia disorder might initially be diagnosed as a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder due to either the clinician’s lack of questions regarding psychotic symptoms or from the patient’s reluctance to tell about psychotic symptoms. However, detection bias seems unlikely to explain the entire association between psychiatric disorders diagnosed in childhood and adolescence and schizophrenia spectrum disorders, because the risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders were clearly elevated even >5 years after the child psychiatric disorder had initially been diagnosed. Therefore, other factors seem more valid to explain the observed association between child and adolescent psychiatric disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. One of these could be chronic neuroinflammation which has been suggested as a risk factor for the development of schizophrenia,9,37 and chronic neuroinflammation might, for instance, cause a range of psychiatric symptoms diagnosed as child and adolescent psychiatric disorders before the later onset of psychotic symptoms leading to the diagnosis with schizophrenia.

The observed long-term association between a previous child psychiatric disorder and the increased risk of later being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders might also be due to the overlapping risk factors, symptoms, and particularly genetics observed between these disorders. We found the long-term risk of schizophrenia spectrum disorders to be elevated by 4.9× during the time period >5 years after the child and adolescent psychiatric disorder was diagnosed. Some of the association could also be a result of the pathway towards schizophrenia spectrum disorders truly going through childhood psychiatric disorders or as a transition from childhood psychiatric disorders to schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychosis in adolescents might start with nonspecific mood, anxiety, and psychosis symptoms which may manifest later as psychotic disorder. An earlier study by Häfner et al10 revealed that the first symptoms of schizophrenia are often manifesting as depression or depressive mood in the early prodromal or premorbid phase. This is in line with our study finding that depression, OCD, and anxiety in the childhood or adolescence were actually the most common diagnoses prior to the schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses.

If shared risk genes are causing this highly elevated risk, these genes must affect many different disorders and not just one, because we found the risk to be elevated following all of the studied childhood psychiatric disorders.

It has been suggested earlier that individuals with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder are diagnosed with schizophrenia at an earlier age when compared with persons with no history of such psychiatric disorders.12,18 This might, in particular, be apparent regarding autism spectrum disorders, because it has been shown earlier, that autism and very early onset schizophrenia often co-occur in patients.16 The findings in this study could therefore support the already-suggested hypothesis of a shared neurodevelopmental pathway between childhood psychiatric disorders and early onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders. However, we did not find that autism facilitates a higher risk for the later diagnosis with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder when compared with the remaining child psychiatric disorders. Neither did ADHD which have also been suggested earlier to be particularly linked with the development of schizophrenia.11,13

In absolute numbers, the cumulative incidences of schizophrenia, the first 8 years after a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder, were 8.74% of the individuals diagnosed with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder in the ages 14–17 years, and 1.68% of individuals diagnosed with a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder diagnosed in the ages 0–13 years. This is higher than the findings of an earlier study17 based upon a smaller number of cases, where 3.4% were diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder after a childhood psychiatric disorder; however, this was not calculated as cumulative incidences. In our study, on a cohort with early onset schizophrenia <22 years, we found that almost half of the individuals diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder in our cohort had an earlier diagnosis with a child psychiatric disorder, which is similar to a smaller prospective cohort study.11

Strengths and Limitations

Major strengths of this study are the prospective design with a large national population-based cohort and a 12-year follow-up period, with all data based on the National Danish registers. The exposure and outcome had been registered independently, which virtually eliminates the risk of recall bias. Furthermore, restricting the cohort to people born in 1990–2000 provided us with complete follow-up and definition of exposure based solely on the ICD-10 diagnostic system, enabling accurate comparability. However, the length of the follow-up period can be considered both a major strength and a limitation. Because the cohort was followed to a maximum of age 22 years, we have no data to estimate the possible association between child and adolescent psychiatric disorders and the risk of later onset schizophrenia.

Limitations to the study include that diagnoses in the registers are clinical diagnoses and not research criteria-based diagnoses. However, specific diagnoses like schizophrenia,38,39 ADHD,40 and autism41 have been shown to have high validity in the Danish registers. In addition, the exposed may be representing a selected group consisting of children and adolescents with more severe psychiatric disorders requiring hospital care (both in- and outpatient care). Hence, we cannot predict the outcome for milder exposed cases, which might affect the generalizability of the study. Furthermore, the age of the oldest cohort member could also be seen as a limitation, because we do not see how having a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder affects the risk of schizophrenia on a longer basis. No one can predict the potential results had we been able to include a longer follow-up. However, the current study utilizes the longest follow-up of the effect of childhood mental disorders on the risk of schizophrenia while estimating both IRRs and absolute risks.

Conclusion and Perspectives

The results found in this study clearly showed a high risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders within the first year after a child and adolescent psychiatric disorder was diagnosed and the risk was still highly elevated >5 years later. This may imply that the early pathways to schizophrenia truly go through child psychiatric disorders or that early signs of schizophrenia can mimic other disorders such as OCD, anxiety, and depression. Furthermore, it might indicate that clinicians need to be more aware of the possible early psychotic symptoms displayed in children, which would make early interventions possible and might improve the prognosis in the long term. Further studies in this area are needed to reveal more about the pathway from child psychiatric disorders towards schizophrenia and to examine genetic factors which may underlie both child and adolescent psychiatric disorders and schizophrenia.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophre niabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

Stanley Medical Research Institute , Bethesda, Maryland, and by grants from The Lundbeck Foundation, Denmark.

Acknowledgments

The funders had no involvement in any aspect of the study. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Hurtig TM, Taanila A, Veijola J, et al. Associations between psychotic-like symptoms and inattention/hyperactivity symptoms. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Konstantareas MM, Hewitt T. Autistic disorder and schizophrenia: diagnostic overlaps. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ. Comparison of children with autism spectrum disorder with and without schizophrenia spectrum traits: gender, season of birth, and mental health risk factors. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:2285–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Larsson HJ, Eaton WW, Madsen KM, et al. Risk factors for autism: perinatal factors, parental psychiatric history, and socioeconomic status. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:916–9–25; discussion 926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peralta V, de Jalón EG, Campos MS, Zandio M, Sanchez-Torres A, Cuesta MJ. The meaning of childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity symptoms in patients with a first-episode of schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2011;126:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jandl M, Steyer J, Kaschka WP. Adolescent attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and susceptibility to psychosis in adulthood: a review of the literature and a phenomenological case report. Early Interv Psychiatr. 2012;6:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. King BH, Lord C. Is schizophrenia on the autism spectrum? Brain Res. 2011;1380:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Owen MJ. Intellectual disability and major psychiatric disorders: a continuum of neurodevelopmental causality. Br J Psychiatr. 2012;200:268–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davis J, Moylan S, Harvey BH, Maes M, Berk M. Neuroprogression in schizophrenia: Pathways underpinning clinical staging and therapeutic corollaries. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 2014;48:512–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Häfner H, Maurer K, an der Heiden W. ABC Schizophrenia study: an overview of results since 1996. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:1021–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2003;60:709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bevan Jones R, Thapar A, Lewis G, Zammit S. The association between early autistic traits and psychotic experiences in adolescence. Schizophr Res. 2012;135:164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dalsgaard S, Mortensen PB, Frydenberg M, Maibing CM, Nordentoft M, Thomsen PH. Association between attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in childhood and schizophrenia later in adulthood. Eur Psychiatr. 2014;29:259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Skokauskas N, Gallagher L. Psychosis, affective disorders and anxiety in autistic spectrum disorder: prevalence and nosological considerations. Psychopathology. 2010;43:8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stahlberg O, Soderstrom H, Rastam M, Gillberg C. Bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other psychotic disorders in adults with childhood onset AD/HD and/or autism spectrum disorders. J Neural Transm. 2004;111:891–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rapoport J, Chavez A, Greenstein D, Addington A, Gogtay N. Autism spectrum disorders and childhood-onset schizophrenia: clinical and biological contributions to a relation revisited. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2009;48:10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Engqvist U, Rydelius PA. The occurrence and nature of early signs of schizophrenia and psychotic mood disorders among former child and adolescent psychiatric patients followed into adulthood. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health. 2008;2:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Margari F, Petruzzelli MG, Lecce PA, et al. Familial liability, obstetric complications and childhood development abnormalities in early onset schizophrenia: a case control study. BMC Psychiatr. 2011;11:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kerbeshian J, Burd L. Tourette disorder and schizophrenia in children. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1988;12:267–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Müller N, Riedel M, Zawta P, Günther W, Straube A. Comorbidity of Tourette’s syndrome and schizophrenia—biological and physiological parallels. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatr. 2002;26:1245–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sandyk R, Bamford CR. Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome associated with chronic schizophrenia. Int J Neurosci. 1988;41:83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2005;62:975–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatr. 2005;162:1785–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pedersen CB, Gøtzsche H, Møller JO, Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53:441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cantor-Graae E, Pedersen CB. Full spectrum of psychiatric disorders related to foreign migration: a Danish population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatr. 2013;27:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:54–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Health Organization. Klassifikation af Sygdomme; Udvidet Dansk-Latinsk Udgave af Verdenssundhedsorganisationens Internationale Klassifikation af Sygdomme. 8 Revision, 1965 [Classification of Diseases: Extended Danish-Latin Version of the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases, 8th Revision, 1965]. Copenhagen: Danish National Board of Health; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: WHO; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30. SAS Institute Inc. The GENMOD Procedure. SAS/STAT 9.2 User’s Guide.Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2008:1609–1–730. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research Volume II - The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies. IARC Scientific Publications No. 82; 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pedersen CB, Mors O, Bertelsen A, et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatr. 2014;71:573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clayton D, Hills M. Statistical Models in Epidemiology. Oxford, New York, Tokyo: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pedersen CB, Mortensen PB. Family history, place and season of birth as risk factors for schizophrenia in Denmark: a replication and reanalysis. Br J Psychiatr. 2001;179:46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Breslow NE. Generalized linear models: checking assumptions and strengthening conclusions. Statistica Applicata 1996;8:23–41. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andersen PK, Geskus RB, de Witte T, Putter H. Competing risks in epidemiology: possibilities and pitfalls. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:861–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Benros ME, Nielsen PR, Nordentoft M, Eaton WW, Dalton SO, Mortensen PB. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for schizophrenia: a 30-year population-based register study. Am J Psychiatr. 2011;16:1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jakobsen KD, Frederiksen JN, Parnas J, Werge T. Diagnostic agreement of schizophrenia spectrum disorders among chronic patients with functional psychoses. Psychopathology. 2006;39:269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Uggerby P, Østergaard SD, Røge R, Correll CU, Nielsen J. The validity of the schizophrenia diagnosis in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register is good. Dan Med J. 2013;60:A4578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Linnet KM, Wisborg K, Secher NJ, et al. Coffee consumption during pregnancy and the risk of hyperkinetic disorder and ADHD: a prospective cohort study. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lauritsen MB, Jørgensen M, Madsen KM, et al. Validity of childhood autism in the Danish Psychiatric Central Register: findings from a cohort sample born 1990–1999. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.