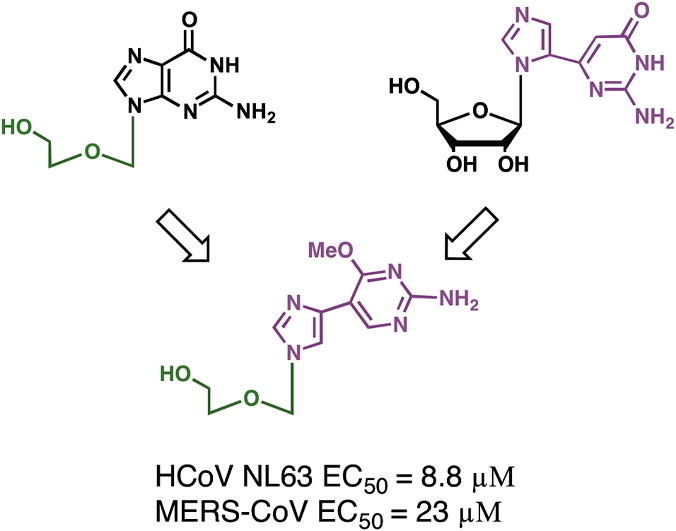

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Fleximers, Coronaviruses, SARS, MERS-CoV, Nucleosides, Acyclovir, Antiviral

Abstract

A series of doubly flexible nucleoside analogues were designed based on the acyclic sugar scaffold of acyclovir and the flex-base moiety found in the fleximers. The target compounds were evaluated for their antiviral potential and found to inhibit several coronaviruses. Significantly, compound 2 displayed selective antiviral activity (CC50 >3× EC50) towards human coronavirus (HCoV)-NL63 and Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus, but not severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus. In the case of HCoV-NL63 the activity was highly promising with an EC50 <10 μM and a CC50 >100 μM. As such, these doubly flexible nucleoside analogues are viewed as a novel new class of drug candidates with potential for potent inhibition of coronaviruses.

Currently there are no approved treatments or vaccines for human coronaviruses (HCoVs) or potentially lethal zoonotic CoVs, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). The current MERS outbreak has been ongoing for almost three years, with well over a thousand confirmed cases having been documented, with a mortality rate of about 40%.1 Since the 2002–2003 SARS outbreak, there have been extensive efforts to target the coronavirus family, including the screening of libraries of already approved antiviral drugs such as acyclovir (ACV), ganciclovir, lamivudine, and zidovudine. Unfortunately, none of these well known antiviral drugs exhibited any activity against SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV in vitro.2

The SARS-CoV screening efforts did, however, yield a small number of leads including the nucleoside analogue ribavirin, a guanosine-like analogue that has exhibited broad-spectrum antiviral activity.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Ribavirin was found to inhibit coronavirus replication in vitro, but with an inhibitory concentration much higher (500–5000 μg/ml) than that needed to inhibit other viruses (50–100 μg/ml). Consequently, it does not appear to represent a viable treatment option. Moreover, a recent study has suggested that in the case of the coronaviruses, ribavirin’s antiviral activity is not primarily due to lethal mutagenesis, but rather to its effect on the cell’s GTP biosynthesis.8 Beyond these studies, there are very few reports of (novel) nucleoside inhibitors being studied or developed to combat coronavirus infection.

HCoVs were first identified in the 1960s with only two species known at the time, HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43. These viruses are known to cause a large number of common colds with typically mild symptoms, with the exception of those suffering from other illnesses, particularly immunocompromised systems.9 In 2002 a new coronavirus pathogen associated with severe lung disease emerged in Guangzhou, and later spread to Southern China and Hong Kong. The new virus was named SARS-CoV,10 and before the end of the outbreak over 8000 cases were confirmed in several countries, resulting in about 812 fatalities. Since then two additional coronaviruses, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1, were discovered in humans and most recently, in 2012, MERS-CoV was identified as a second zoonotic coronavirus that can cause lethal respiratory infections in humans.

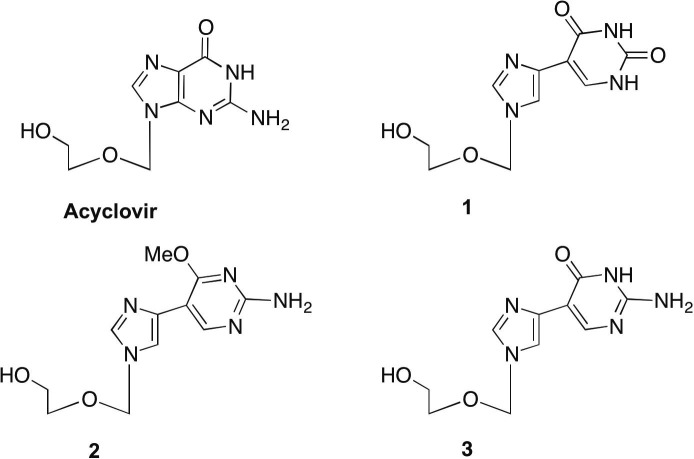

Our laboratory has spent a number of years developing different series of flexible, or ‘split’ purine base analogues. These unique nucleoside analogues have been termed ‘fleximers’ and were designed to explore how nucleobase flexibility affects the recognition, binding, and activity of nucleoside(tide) analogues.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 The fleximers possess a purine base scaffold in which the imidazole and pyrimidine moieties are attached by a single carbon–carbon bond, rather than being ‘fused’ as is typical for the purines (Fig. 1 ). These analogues are designed to retain all of the requisite purine hydrogen bonding patterns while allowing the nucleobase to explore alternative binding modes. Previous work from our group have shown these analogues to have several strategic advantages—increased binding affinity compared to the corresponding rigid inhibitors, binding affinity to atypical enzymes, as well as the ability to overcome point mutations in biologically significant binding sites.11, 12, 17

Figure 1.

Acyclovir (ACV) and target fleximer analogues (1–3).

In designing the target molecules the flex-base modification of the fleximers was combined with the acyclic sugar moiety of acyclovir (ACV). ACV is a nucleoside polymerase inhibitor currently approved for the treatment of herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) infections.18 Recently, it was also found to have activity against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) when McGuigan’s ProTide technology was employed.19 It was found to suppress the replication of both HIV-1 and HSV-2 in the submicromolar range in lymphoid and cervicovaginal human tissues and at 3–12 μmol/L in CD4+ T cells.19 Our analogues were designed in hopes of mimicking this broad-spectrum biological activity.

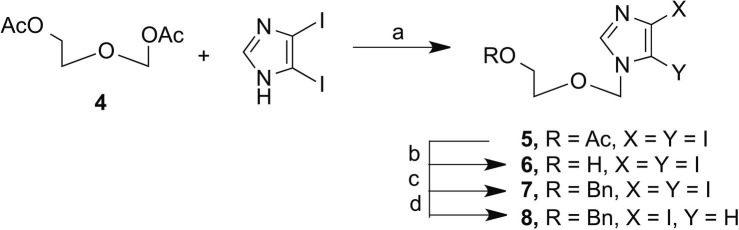

In approaching the synthesis of these analogues we began with the previously published route to the acyclic sugar moiety and then utilized a series of organometallic coupling techniques in order to construct the flexible base.

The route to 8 involved coupling 2-aceteoxyethyl acetoxymethylether (4), synthesized according to published procedures,20 to diiodoimidazole using modified Vorbruggen conditions.20 This was followed by removal of the more labile acetate protecting group and subsequent protection with the more robust benzyl. Then, selective deiodination of the C5-iodo with EtMgBr (Scheme 1 ) yielded key intermediate 8.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide, acetonitrile, TMSOTf; (b) NH4OH, EtOH; (c) Bu4NI, NaH, BnBr; (d) EtMgBr, anhydrous DMF.

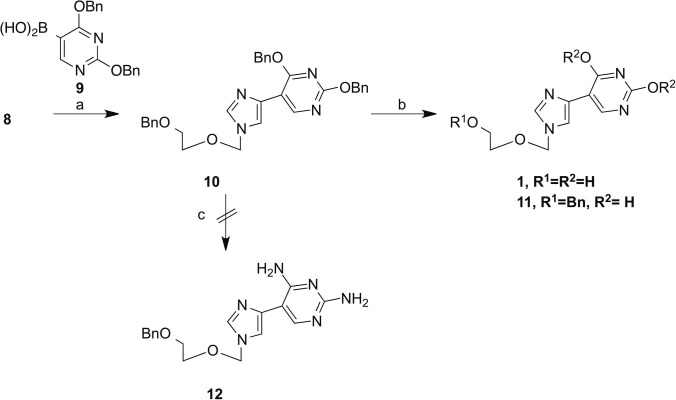

This product served as a key intermediate for a series of organometallic coupling reactions. The first coupling partner selected was the boronic acid derivative of 2,4-dibenzyluracil (9). This analogue was chosen due to the versatility of compound 10. As had been previously published by our group,13 it was hypothesized it would be possible to obtain both the Flex-xanthosine and Flex-guanosine analogues from 10 (Scheme 2 ). Preparation of the boronic acid 9 followed established procedures21 and was used immediately without further characterization. Using standard Suzuki reaction conditions in the presence of freshly prepared Pd(PPh3)4, 10 was obtained in a 45% yield. In order to obtain the xanthosine analogue, 10 was treated with Pd/C to remove the benzyl protecting groups to yield final compound 1 in a 26% yield. It was also discovered that by lowering the temperature of the reaction, the benzyl groups could be selectively removed from the base. This is convenient, as it would allow for future functionalization of 11 without the need to selectively reprotect the free hydroxyl.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Pd(PPh3)4, NaHCO3, dimethoxyethane; (b) Pd/C, ammonium formate, EtOH, for 1:120 °C, 18 h, for 11:60 °C for 18 h; (c) methanolic ammonia, 210 °C.

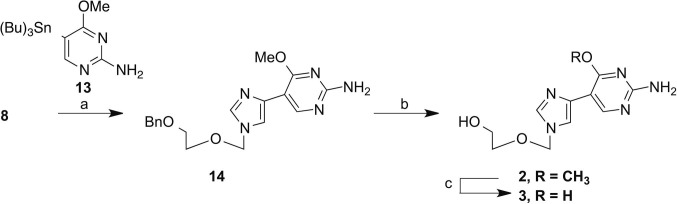

In an attempt to obtain the guanosine analogue, 10 was treated with methanolic ammonia under pressure, at 210 °C to yield the intermediate diamino compound 12. Unfortunately, the reaction resulted in a single site transformation at the 4-position. Due to extreme reaction conditions and low yield this route was abandoned. Ultimately, the guanosine analogues were obtained through Stille coupling of key intermediate 8 with the appropriate pyrimidine 13. Pyrimidine 13 was prepared from commercially available 2-amino-5-chloro-6-methoxy pyrimidine according to published procedures. The subsequent coupling was completed using modified Stille coupling conditions based on the findings of Mee et al.22

In order to acquire final compound 2, a selective deprotection was used to remove the benzyl group, while leaving the 6-methoxy intact. This was done with Pd/C in the presence of ammonium formate in EtOH under reflux for 18 h. This yielded 2 in a 24% yield, with the remainder (52%) retrievable as starting material, which could be recycled. The final deprotection was accomplished with BBr3 at room temperature to yield 3 in a 24% yield (Scheme 3 ).

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Pd(PPh3)4, CuI, TBAF, DMF, 45 °C, 18 h; (b) Pd/C, ammonium formate, EtOH, 120 °C, 18 h; (c) BBr3.

In the first screen, the effect of the three target fleximer analogues on the replication of HCoV-NL63 was evaluated. HCoV-NL63 infection does not result in full cytopathy in the Vero-118 cell culture model used. For this reason, the antiviral effect was analyzed microscopically by scoring virus-induced cytopathogenic effects (CPE) in each well on a scale of 1 (mild) to 5 (severe). These scores were then used to calculate the percentage of inhibition by normalization to control wells. As shown in Table 1 , in contrast to acyclovir, one of the tested nucleosides, nucleoside 2, demonstrated selective antiviral activity (CC50 > 10x).

Table 1.

Antiviral activity of nucleoside analogues

| HCoV-NL63 on Vero118 |

MERS-CoV on Huh7 |

MERS-CoV on Vero |

SARS-CoV on VeroE6 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50a | CC50b | EC50 | CC50 | EC50 | CC50 | EC50 | CC50 | |

| 1 | 92 ± 68 | >200 | NDc | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 2 | 8.8 ± 1.5 | 120 ± 37 | 27 ± 0.0 | 149 ± 6.8 | 23 ± 0.6 | 71 ± 14 | No effect | 138 ± 69 |

| 3 | >200 | >200 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Acyclovir | >100 | >100 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

EC50: effective concentration showing 50% inhibition of virus-induced CPE (in μM).

CC50: cytotoxic concentration showing 50% inhibition of cell survival (in μM).

ND: not determined.

Based on these results we also evaluated the activity of nucleoside 2 on the more pathogenic viruses MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV. Infection of Huh7 and Vero cells with MERS-CoV and VeroE6 cells with SARS-CoV resulted in complete CPE. This allowed for the quantification of the antiviral effect by using a commercial cell viability assay as described previously.23, 24 Inhibition of virus-induced CPE (i.e., enhanced cell viability compared to untreated, virus-infected cells) was determined in the presence of different compound concentrations. The results depicted in Table 1 indicate that compound 2 can block the replication of MERS-CoV but not SARS-CoV while acyclovir had no effect (Table 1).

The effect of 2 on HCoV-NL63 is significant with an EC50 <10 μM and a CC50 >100 μM. Our experiments showed that 2 reduced the viability of different cell lines at different concentrations suggesting a cell-specific effect. The different sensitivity of the cell lines towards this nucleoside could be caused by differences in growth rate, compound uptake and metabolism, or other cell line-specific characteristics.

The need for new and more effective antiviral therapeutics, particularly those targeting emerging and reemerging infectious diseases and pathogens continues to increase. Herein we have described the design, synthesis and preliminary screening of a series of novel nucleoside analogues that employ a strategy of combining the flex-base motif with the flexible acyclic sugar scaffold of the FDA-approved drug acyclovir. We have shown that this approach produces medicinally relevant molecules capable of inhibiting HCoV-NL63 and MERS-CoV replication in cell culture. Although the parental compound, acyclovir, serves as a polymerase inhibitor,25, 26 it is yet unclear how these novel analogues disrupt viral replication. Efforts are now underway to pursue additional analogues that will be used to elucidate the mechanism of action.

Moreover, a comparison of the activity profiles of compounds 2 and 3 draws speculation that the methoxy group may be serving as a prodrug, as has been established in other antiviral nucleoside analogues.27 Thus, additional prodrug moieties will be pursued in subsequent studies, as this approach has been shown to greatly enhance antiviral activity of nucleoside analogues. These conclusions will aid us in our efforts to more effectively design a second generation of analogues. In addition, further functionalization will be pursued in order to further explore these analogues’ potential as antiviral agents. The results of those studies will be reported elsewhere as they become available.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessika Zevenhoven-Dobbe for technical assistance. This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health [R21AI097685 (K.S.R.) and T32GM066706 (K.S.R. and H.L.P.)], and the EU FP7 project SILVER (260644, D.J., J.N., A.dW., C.C.P., and E.J.S.).

Footnotes

Supplementary data (synthetic procedures and structural characterization) associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.05.039.

Supplementary data

Synthetic procedures and structural characterization.

References and notes

- 1.In Global alert and response. Middle East Respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV); World Health Organization: 2015; Vol. 2014.

- 2.Tan E.L., Ooi E.E., Lin C.Y., Tan H.C., Ling A.E., Lim B., Stanton L.W. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:581. doi: 10.3201/eid1004.030458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Momattin H., Mohammed K., Zumla A., Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfiq J.A. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;17:e792. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Momattin H., Dib J., Memish Z.A. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgenstern B., Michaelis M., Baer P.C., Doerr H.W., Cinatl J., Jr. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;326:905. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen F., Chan K.H., Jiang Y., Kao R.Y., Lu H.T., Fan K.W., Cheng V.C., Tsui W.H., Hung I.F., Lee T.S., Guan Y., Peiris J.S., Yuen K.Y. J. Clin. Virol. 2004;31:69. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falzarano D., de Wit E., Rasmussen A.L., Feldmann F., Okumura A., Scott D.P., Brining D., Bushmaker T., Martellaro C., Baseler L., Benecke A.G., Katze M.G., Munster V.J., Feldmann H. Nat. Med. 2013;19:1313. doi: 10.1038/nm.3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith E.C., Blanc H., Vignuzzi M., Denison M.R. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003565. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyrc K., Berkhout B., van der Hoek L. Expert Rev. Anti-infect. Ther. 2007;5:245. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W., Nicholls J., Yee W.K., Yan W.W., Cheung M.T., Cheng V.C., Chan K.H., Tsang D.N., Yung R.W., Ng T.K., Yuen K.Y. Lancet. 2003;361:1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quirk S., Seley K.L. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10854. doi: 10.1021/bi0503605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seley K.L., Quirk S., Salim S., Zhang L., Hagos A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1985;2003:13. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seley K.L., Salim S., Zhang L. Org. Lett. 2005;7:63. doi: 10.1021/ol047895v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seley K.L., Zhang L., Hagos A. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3209. doi: 10.1021/ol0165443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seley K.L., Zhang L., Hagos A., Quirk S. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3365. doi: 10.1021/jo0255476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wauchope O.R., Velasquez M., Seley-Radtke K. Synthesis. 2012;44:3496. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1316791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quirk S., Seley K.L. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13172. doi: 10.1021/bi051288d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.In Zovirax Prescribing Information; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: 2003; NDA 18-603/5-027.

- 19.Vanpouille C., Lisco A., Derudas M., Saba E., Grivel J.C., Brichacek B., Scrimieri F., Schinazi R., Schols D., McGuigan C., Balzarini J., Margolis L. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201:635. doi: 10.1086/650343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boncel S., Gondela A., Maczka M., Tuszkiewicz-Kuznik M., Grec P., Hefczyc B., Walczak K. Synthesis-Stuttgart. 2011:603. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schinazi R. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:841. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mee S.P., Lee V., Baldwin J.E. Chemistry. 2005;11:3294. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Wilde A.H., Raj V.S., Oudshoorn D., Bestebroer T.M., van Nieuwkoop S., Limpens R.W., Posthuma C.C., van der Meer Y., Barcena M., Haagmans B.L., Snijder E.J., van den Hoogen B.G. J. Gen. Virol. 2013;94:1749. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.052910-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Wilde A.H., Jochmans D., Posthuma C.C., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J.C., van Nieuwkoop S., Bestebroer T.M., van den Hoogen B.G., Neyts J., Snijder E.J. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4875. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03011-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furman P.A. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:9575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuirt P.V., Furman P.A. Am. J. Med. 1982;73:67. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGuigan C., Madela K., Aljarah M., Gilles A., Brancale A., Zonta N., Chamberlain S., Vernachio J., Hutchins J., Hall A., Ames B., Gorovits E., Ganguly B., Kolykhalov A., Wang J., Muhammad J., Patti J.M., Henson G. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:4850. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Synthetic procedures and structural characterization.