Abstract

Objective

To examine the prevalence and secular trends in benzodiazepine (BZD) prescribing in the Irish paediatric population. In addition, we examine coprescribing of antiepileptic, antipsychotic, antidepressant and psychostimulants in children receiving BZD drugs and compare BZD prescribing in Ireland to that in other European countries.

Setting

Data were obtained from the Irish General Medical Services (GMS) scheme pharmacy claims database from the Health Service Executive (HSE)—Primary Care Reimbursement Services (PCRS).

Participants

Children aged 0–15 years, on the HSE-PCRS database between January 2002 and December 2011, were included.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Prescribing rates were reported over time (2002–2011) and duration (≤ or >90 days). Age (0–4, 5–11, 12–15) and gender trends were established. Rates of concomitant prescriptions for antiepileptic, antipsychotics, antidepressants and psychostimulants were reported. European prescribing data were retrieved from the literature.

Results

Rates decreased from 2002 (8.56/1000 GMS population: 95% CI 8.20 to 8.92) to 2011 (5.33/1000 GMS population: 95% CI 5.10 to 5.55). Of those children currently receiving a BZD prescription, 6% were prescribed BZD for >90 days. Rates were higher for boys in the 0–4 and 5–11 age ranges, whereas for girls they were higher in the 12–15 age groups. A substantial proportion of children receiving BZD drugs are also prescribed antiepileptic (27%), antidepressant (11%), antipsychotic (5%) and psychostimulant (2%) medicines. Prescribing rates follow a similar pattern to that in other European countries.

Conclusions

While BZD prescribing trends have decreased in recent years, this study shows that a significant proportion of the GMS children population are being prescribed BZD in the long term. This study highlights the need for guidelines for BZD prescribing in children in terms of clinical indication and responsibility, coprescribing, dosage and duration of treatment.

Keywords: PAEDIATRICS, CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study aims to examine the prevalence and trends in benzodiazepine (BZD) prescribing in an Irish paediatric population, as well as concomitant use of antipsychotic, antidepressant and psychostimulant drugs.

The Health Service Executive—Primary Care Reimbursement Services (HSE-PCRS) General Medical Services (GMS) scheme pharmacy claims database represents approximately one-third of Irish children and over-represents more socially disadvantaged children in the Irish population. This may result in an overestimation of the true trends in BZD prescription rates, given that children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to be prescribed a psychotropic medication and are at greater risk of epilepsy and anxiety-related disorders.

The database does not contain information about the clinical indication for prescriptions or the setting in which the prescription was initiated (eg, primary care, hospital or specialist setting). It is unclear why certain classes of BZD were prescribed, and why changes in the rates of prescribing were observed over the 10-year period.

Introduction

The use of psychotropic medications among children and adolescents has increased markedly in the past two decades.1–4 In the USA, for example, paediatric use of psychotropic drugs increased threefold between 1987 and 1996.5 A similar trend was observed in nine countries worldwide between 2000 and 2002.6 Reports suggest that this trend is driven by a greater use of stimulants, antidepressants and antipsychotics.7 Fewer studies have reported data on the use of benzodiazepines (BZDs) in children. Furthermore, no studies have considered prescribing patterns of z drugs to children.i Those that have examined BZD prescribing practices in children and adolescents report slight increases over time.5 Despite these trends, the literature supporting such increases is sparse and it remains unclear what information is guiding clinicians BZD prescribing practices.5

BZDs are often used to control several types of seizures in young children. Among the most common BZDs for this indication are diazepam, clonazepam and lorazepam. Diazepam is most frequently used in the treatment of status epileptics and cerebral convulsions.8 Clinicians recommend caution when prescribing BZD to children, and research into long-term prescribing in this population advocates short-term courses (6–12 weeks) because of their depressant properties and potential for tolerance and dependency.9 10 Furthermore, long-term use can result in increased risk of cognitive deficits11 12 and presentation of mild withdrawal syndrome.13

To date, very little work has been conducted to systematically assess the role of BZDs in child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Little is known about the efficacy of BZDs in the treatment of psychiatric symptoms in children,5 14 15 and there is no firmly established indication for their use with childhood psychiatric disorders.10 Studies that have examined the efficacy of BZDs in the treatment of childhood psychiatric disorders report significant improvements in symptoms. For example, several studies have shown that alprazolam reduces anxiety in children who meet the criteria for anxiety disorder.16–18 However, there are inconsistencies in the literature. For example, a well-controlled double-blind pilot study revealed no clinically significant effects on anxiety in a small sample of children with a diagnosis of one or more anxiety disorders.19 Furthermore, a study of social phobia in children and adolescents did not support the use of BZD in anxiety treatment.20 The differences observed in research findings may be attributed to a number of issues such as a shortage of well-designed studies with longitudinal examination of the effects, an inability to replicate the studies that do demonstrate promising results and the long-term safety concerns of prescribing BZD in younger age groups. Furthermore, research to date has focused mostly on adult populations, with limited focus on paediatric prescribing of BZDs in community settings.5 This is a common feature among many psychotropic medications whereby they are not trialled in children, so little or no information is available on their effectiveness and safety.

The aim of the current study is to investigate BZD and z drug prescribing in an Irish paediatric population from a predominantly low socioeconomic group receiving free medical care over a 10-year period (2002–2011) and to establish long-term prescribing patterns, gender and age trends, and concomitant prescribing rates of BZD in children. An additional aim is to compare the prescribing Irish rates with those of European studies.

Methods

Study population and study design

Data were obtained from the Irish General Medical Services (GMS) scheme pharmacy claims database from the Health Service Executive (HSE)—Primary Care Reimbursement Services (PCRS). The pharmacy claims database contains basic demographic information and details on monthly dispensed medications, coded using the WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system, for each individual within the scheme. The scheme is means tested and provides free health services. It represents approximately 28% of Irish children (<15 years old) but over-represents socially deprived populations. Permission was given by the data controller to use the GMS data set if it was anonymised and analysed at the group level. Therefore, it was unnecessary to seek specific ethical approval for this study.

Children aged 0–15 years on the HSE-PCRS database between January 2002 and December 2011 were included in this study. All BZD medication prescriptions (ATC codes: N03AE, N05BA, N05CD and N05CF)21 were extracted from the database. Concomitant prescriptions of antipsychotic medications (N05A), psychostimulant medications (N06B), antiepileptic medications (N03) and antidepressants (N06A) were also extracted.

Data analysis

The prevalence rates of benzodiazepines per 1000 GMS population per year and associated 95% CIs for children aged 0–15 years were calculated as a proportion of all eligible children (0–15 years) entitled to free health services, as identified from the annual reports produced by the PCRS. Prevalence rates are to be interpreted as the prevalence of children under the age of 15 years receiving at least one benzodiazepine prescription per 1000 GMS population, as determined from the GMS database. Prevalence rates per 1000 eligible population and associated 95% CIs were also calculated across years (2002–2011). Prevalence of short-term (≤90 days) and long-term (>90 days) use among children (≤15 years) was investigated. Additionally, age groups (0–4, 5–11 and 12–15) and gender trends were established. Rates of concomitant prescribing of other psychotropic medication in childhood were calculated.

A negative binomial regression model was used to determine trends in prescribing rates. The log of the GMS population was used as the offset term and year, age group, gender and all possible interactions between these variables were included as fixed effects in the model. The Bonferroni method was used to control for multiple comparisons, p values were adjusted and p values <0.01 were deemed significant.

Data analyses were performed using Stata V.11 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) and SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute Inc Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Comparison to European studies

Comparison studies examining overall psychotropic medication trends in paediatric populations were identified from a search of the published literature from 1980 to 2013. Articles were included if they reported paediatric BZD prescribing rate in a community setting and provided overall rates of BZD prescribing. Studies which reported overall percentage prevalence were transformed to per 1000 prevalence rate to facilitate comparison.

Results

Population sample

During the study period January 2002 to December 2011, the number of children ≤15 years in Ireland, as identified from the HSE-PCRS pharmacy database, ranged between 188 833 and 311 579. On average, 51% of the study population were male and 49% were female.

Prescribing time trends

Table 1 shows the prevalence of benzodiazepines for 2002–2011. In 2002, 8.56/1000 GMS population (95% CI 8.20 to 8.92) received at least one benzodiazepine prescription and this rate decreased to 5.33/1000 GMS population (95% CI 5.10 to 5.55) in 2011. Benzodiazepine prescribing decreased nearly every year over the study period, except for 2005 and 2011 where there were slight increases from the previous year (table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence rates (95% CIs) of prescribing benzodiazepines to children aged 0–15 years from 2002 to 2011

| Year | Prevalence rate per 1000 GMS population (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| 2002 | 8.56 (8.20 to 8.92) |

| 2003 | 8.64 (8.28 to 9.00) |

| 2004 | 8.20 (7.84 to 8.56) |

| 2005 | 8.42 (8.06 to 8.78) |

| 2006 | 7.34 (7.01 to 7.67) |

| 2007 | 6.88 (6.57 to 7.19) |

| 2008 | 6.32 (6.04 to 6.60) |

| 2009 | 5.95 (5.69 to 6.21) |

| 2010 | 5.27 (5.03 to 5.50) |

| 2011 | 5.33 (5.10 to 5.55) |

GMS, General Medical Services.

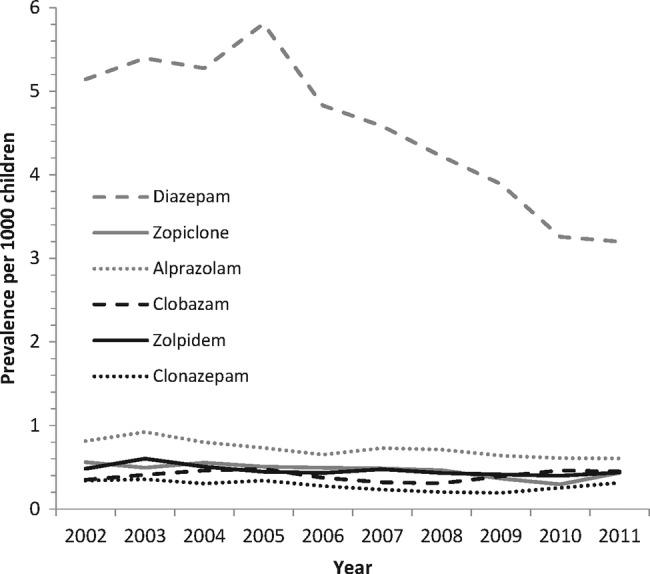

During the study period, diazepam was the most frequently prescribed benzodiazepine. Following the overall benzodiazepine trend, the prevalence decreased from 5.14/1000 GMS population (95% CI 4.86 to 5.42) in 2002 to 3.20/1000 GMS population (95% CI 3.02 to 3.38) in 2011. Rates of zopiclone, alprazolam, clobazam, zolpidem and clonazepam remained relatively stable over the 10 years (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence rates of the six most frequently prescribed benzodiazepines per 1000 General Medical Services population aged 0–15 years for 2002–2011.

Long-term use

Between January 2002 and December 2006, a total of 7844 children had at least one benzodiazepine prescription and 5.7% of these children were taking benzodiazepines for longer than 90 days. From January 2007 to December 2011, 7453 children had at least one benzodiazepine prescription and 6.2% of these children were taking benzodiazepines for longer than 90 days. Table 2 shows the breakdown of children taking benzodiazepines on a long-term basis by gender and age group. This table shows that the highest percentage of children taking benzodiazepines on a long-term basis are between 5 and 11 years of age. Additionally, from 2002–2006 to 2007–2011, the percentage of males and females with long-term use increased slightly for all age groups except for males aged 12–15 years.

Table 2.

The number and percentage of children, per age group, identified as taking benzodiazepines in the long term (>90 days)

| Males |

Females |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤90 days | >90 days | Total | ≤90 days | >90 days | Total | |

| 2002–2006 | ||||||

| 0–4 years | 1360 (95.6%) | 62 (4.4%) | 1422 | 1114 (96.0%) | 46 (4.0%) | 1160 |

| 5–11 years | 1381 (93.7%) | 93 (6.3%) | 1474 | 1101 (91.9%) | 97 (8.1%) | 1198 |

| 12–15 years | 1162 (93.6%) | 80 (6.4%) | 1242 | 1280 (95.0%) | 67 (5.0%) | 1348 |

| 2007–2011 | ||||||

| 0–4 years | 1166 (95.4%) | 56 (4.5%) | 1222 | 923 (94.6%) | 53 (5.4%) | 976 |

| 5–11 years | 1325 (92.9%) | 101 (7.1%) | 1426 | 956 (91.6%) | 88 (8.4%) | 1044 |

| 12–15 years | 1234 (94.0%) | 79 (6.0%) | 1313 | 1388 (94.3%) | 84 (5.7%) | 1472 |

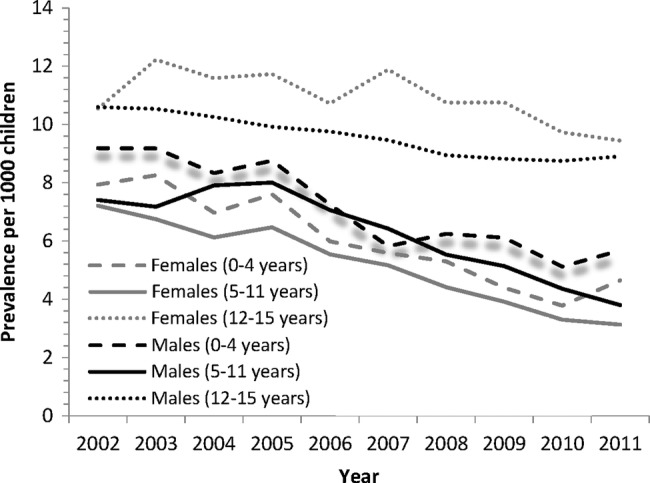

Gender and age

Figure 2 shows the prevalence rates of benzodiazepines for all years for males and females and all age groups (0–4, 5–11 and 12–15). The interactions between age group×year (p<0.01) and age group×gender (p<0.01) were significant. This means that the effect of age group on the prevalence of benzodiazepines differed over the years, and over males and females separately. Significant differences were observed between males and females for all age groups; males had higher rates at 0–4 and 5–11 years, whereas females had higher rates at 12–15 years. Additionally, significant differences were seen for all years between age groups whereby 12–15 years had significantly higher rates of prescribing than 0–4 years and also 5–11 years.

Figure 2.

Prevalence rates of benzodiazepines per 1000 General Medical Services population aged 0–15 years for 2002–2011 classified by gender and age group.

Concomitant medications

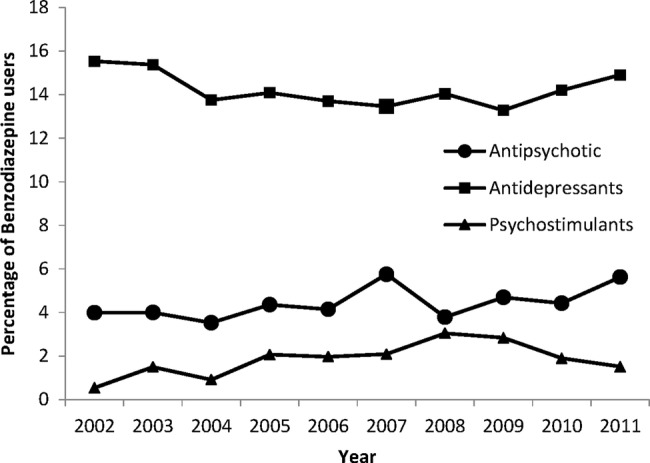

An antiepileptic was coprescribed to 28% of BZD users, an antidepressant to 11% of users, antipsychotics to 5% and a psychostimulant to 2% of users (table 4). The proportion of concomitant medications changed significantly during the observation period. Rates of concomitant antiepileptic prescribing increased between 2002 and 2004, and between 2006 and 2008. Rates of concomitant prescribing of psychostimulants increased from 2002 to 2009 inclusively (table 4). Excluding patients who took antiepileptics, antipsychotic medication was prescribed to 4% of all benzodiazepine users, an antidepressant to 14% and psychostimulants to 2% of users (figure 3).

Table 4.

Percentage of benzodiazepine users (aged 0–15 years) from 2002 to 2011 taking concomitant medications

| Year | Benzodiazepine users (n) |

Concomitant antipsychotics n (%) |

Concomitant antiepileptics n (%) |

Concomitant antidepressants n (%) |

Concomitant psychostimulants n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2127 | 81 (3.81) | 498 (23.41) | 272 (12.79) | 20 (0.94) |

| 2003 | 2154 | 87 (4.04) | 553 (25.67) | 266 (12.35) | 35 (1.62) |

| 2004 | 1990 | 84 (4.22) | 572 (28.74) | 215 (10.80) | 21 (1.06) |

| 2005 | 2031 | 91 (4.48) | 633 (31.17) | 219 (10.78) | 45 (2.22) |

| 2006 | 1928 | 92 (4.77) | 556 (28.84) | 215 (11.15) | 37 (1.92) |

| 2007 | 1916 | 116 (6.05) | 579 (30.22) | 204 (10.65) | 36 (1.88) |

| 2008 | 1895 | 91 (4.80) | 549 (28.97) | 213 (11.24) | 51 (2.69) |

| 2009 | 1996 | 116 (5.81) | 550 (27.56) | 211 (10.57) | 50 (2.51) |

| 2010 | 1951 | 95 (4.87) | 528 (27.06) | 222 (11.38) | 36 (1.85) |

| 2011 | 2067 | 130 (6.29) | 557 (26.95) | 255 (12.34) | 40 (1.94) |

Percentage of benzodiazepine users aged 0–15 years who also received concomitant antipsychotics (column 3) or antiepileptics (column 4) or antidepressants (column 5) or psychostimulants (column 6) medication from 2002 to 2011.

Figure 3.

Percentage of benzodiazepine users aged 0–15 years who are also taking antipsychotics, antidepressants and psychostimulant medications for the years 2002–2011 (excluding patients who took antiepileptics, codes under Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification as N03).

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies included for comparative data and a comparison of average prescribing rates per 1000 GMS children between 2001 and 2011 with European rates per 1000 children

| Study (publication year) | Country (year data represent) | Sample size | Age | Rate of BZD prescribing (per 1000) | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquaviva et al (2009) | France (2003–2005) | 14 070 021 | 0–18 | 7.8 | National health insurance system data |

| Hugtenburg et al (2004) | The Netherlands (1995–2001) | 1 000 000 | 0–18 | 9 | Dispensing data from retail pharmacies |

| Gyllenberg and Sourander (2012) | Finland (1994–2005) | 60 007 | 0–24 | 4.4 | National drug prescription register |

| Schirm et al (2001) | The Netherlands (1995–1999) | 31 140 | 0–19 | 6.9 | Dispensing data from community pharmacy database |

| GMS data | Ireland (2002–2011) | 311 579 | 0–15 | 6.7 | Primary care reimbursement service pharmacy claims |

BZD, benzodiazepine; GMS, General Medical Services.

Comparison with European countries

Studies examining overall psychotropic medication trends in paediatric populations and reporting a BZD prescribing rate in a community setting between 1990 and 2013 were identified. Two studies were identified from the Netherlands, one from France and one from Finland.

The overall prescribing rate of BZD for this study was 6.7/1000 GMS population. This is higher than 4.4/1000 in Finland (1994–2005) but lower than 7.8/1000 in France (2003–2005). Two studies were identified from the Netherlands with rates of 6.5/1000 (1995–1999) and 9/1000 (1995–2001). This shows that the rates of BZD prescribing in paediatrics in Europe varies a lot and indicates that Ireland is ranked near the median. However, there is high heterogeneity across the different studies, in terms of age groups, sample size and year in which the data are assessed.

Discussion and conclusion

Prescribing trends

The overall rate of BZD prescribing according to the dispensed medication data has decreased between 2002 and 2011, with the exception of 2005 and 2011 where small increases were observed. Over the study period, it was also seen that diazepam was prescribed most frequently. The rate of prescribing to children on the GMS scheme was close to the median value, relative to the European countries with data available for comparison. Ireland reported lower rates than France and the Netherlands but higher rates than Finland.

Paediatric clinical trials into the safety and efficacy of BZD have found it difficult to overcome the concern about the potential for addiction or other adverse events (eg, disinhibition).1 While trends indicate a decrease in prescribing rates in recent times, there is still a significant proportion of the GMS children population who are being prescribed BZD. The rate of children being prescribed BZD is lower than that of adults on the GMS scheme; in 2002, an Irish report revealed that 11.6% of adults were in receipt of a BZD prescription22 and that this rate was steadily increasing.23 This shows that a lower proportion of children on the GMS scheme are being prescribed BZD than adults, and while the current trends show reduced prescribing rates, they also highlight the need for more large-scale, well-designed studies that address the safety concerns associated with prescribing BZD to children, the clinical indication for the BZD, the dosage and duration of prescribing.24

Long-term use

The long-term prescribing of BZD in Ireland was investigated and it was found that 5.9% of children prescribed BZD were taking them for a period longer than 90 days. The prevalence of long-term use increased across the study period and the highest percentage of children taking BZD in the long term were in the 5–11 age group. No formal studies of the long-term safety of children on BZD were found. Long-term use of BZD in adults has resulted in significant cognitive deficits,18 withdrawal syndrome25 and increased risk of dependency.10 The current findings suggest that the proportion of children being prescribed BZD in the long term may be at increased risk of these effects. A report in 2002 reviewed BZD prescribing in adults and provided clinical guidelines for BZD prescribing.22 Clinicians were advised that they should examine the benefit–risk ratio in each individual case early in BZD treatment. Furthermore, clinical guidance is that if BZD are used as anxiolytics for children, there should be a careful assessment of the clinical indication, and treatment duration should be kept to a minimum due to the risk of dependence. The observation that long-term use is increasing over this study period, while overall rates are decreasing, may indicate the need for specific clinical practice recommendations for BZD prescribing to children.

Gender and age

The age differences that were observed here are consistent with the literature from Denmark26 and France,27 with the prevalence of prescription rates of BZD increasing with age. The current data show that children aged 12–15 year were prescribed more BZD. The prevalence rate for children aged 12–15 year in this study was slightly higher than that observed in Denmark.25 Significant differences in gender rates of prescribing of BZD were also seen. Compared with females, males were prescribed more BZD in the 0–4 and 5–11 age groups. However, this pattern reversed for the children aged 12–15 year and females were prescribed significantly more. This observation is consistent with the European comparison studies whereby the frequency of BZD prescribing is higher in boys until age 13 when adolescent girls are then prescribed double that for adolescent boys.28 This observation may relate to gender differences in the incidence of anxiety disorders. Women are twice as likely to meet the criteria for generalised anxiety disorder as men,29 and gender differences in prevalence of general anxiety disorder usually emerge in early adolescence.30

Concomitant medications

Coprescribing was most common with antiepileptic medication (27%), followed by antidepressants (11%), and less so with antipsychotics (5%) and psychostimulants (2%). The comparative European data show that antidepressants were most commonly prescribed with BZD (24%) and that this was at a higher rate than that for the Irish population;31 however, in one comparison study, concomitant BZD prescribing was so low that it was not reported.32 When patients who were prescribed antiepileptic were excluded from the analysis, the percentage of concomitant prescribing of antidepressants increased, whereas antipsychotics and psychostimulant prescribing remained similar. This finding may indicate that children who are being prescribed BZDs with antidepressants are doing so for psychiatric symptoms.

The efficacy of drug combinations in treating paediatric symptoms is underexplored. A systematic review examined the treatment of depression with a BZD and antidepressant combination versus an antidepressant only approach. Results showed that the BZD and antidepressant combination had a significant impact on patient behaviour whereby it decreased dropout rates. However, 6–8 week follow-up revealed no differences in depression symptoms. The review did, however, highlight an increased risk of dependence in the combination group (1 in 3 patients) and discussed the likelihood of reduced effects of BZD in the combination group due to increased tolerance levels and drug interactions.33 In adult clinical practice, BZD is regularly coprescribed with antidepressants in the treatment of depression. A study in Japan found that 60% of patients who presented with major depression were prescribed a combination of BZD and antidepressants on their first psychiatric visit.34 In spite of high rates of coprescribing, the efficacy of combined antidepressants and BZD in the treatment of psychiatric symptoms has not been established.

When considering paediatric prescribing practices, the potential for interaction between psychotropic drugs is an area of concern. Fluoxetine and paroxetine are antidepressants that are regularly prescribed to children with depression. Animal and human research has shown that these can reduce the rate of metabolism of BZD,34 and in one recent animal study the combination of fluoxetine and BZD actually reversed fluoxetine's anxiogenic effects.35 These findings, and the observation that a significant proportion of children on BZD are also being prescribed antidepressants, suggest that an examination of the interactive effects of BZD and other psychotropic drugs are an important area of further investigation in paediatric prescribing.

Limitations

The HSE-PCRS GMS scheme pharmacy claims database represents approximately one-third of Irish children and over-represents more socially disadvantaged children in the Irish population. This may result in an overestimation of the true trends in BZD prescription rates, given that children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to be prescribed a psychotropic medication30 36 and are at greater risk of epilepsy37 and anxiety-related disorders.30 Direct comparison of European prescribing rates for low socioeconomic populations was not possible because of a lack of published data in this subpopulation.

The HSE-PCRS GMS data set does not collect information about the indication for prescriptions or about the setting in which the prescription was initiated (eg, primary care, hospital or specialist setting). Therefore, it is unclear why certain classes of BZD were prescribed, and why changes in the rates of prescribing were observed over the 10-year period. It could be speculated that the reduced incidence of BZD prescribing in children may be related to physician preferences, changes in knowledge about the long-term effects of BZD or the development of new medications. Not knowing the clinical indication for which the prescription was administered makes it difficult to fully comment on the quality and appropriateness of BZD prescribing rates, especially as BZDs are often indicated to treat epilepsy. In this study, it is impossible to know whether BZD was prescribed to treat anxiety or epilepsy. To the best of our knowledge, in Ireland, there is no publication giving an estimation of the rates of benzodiazepines used against anxiety or epilepsy together. However, as was observed in other studies, the proportion of benzodiazepines used to treat epilepsy is likely to be very low compared with psychiatric/psychological indications.26

Conclusions

Trends of BZD prescribing in the GMS population in Ireland show that BZD prescribing has decreased over the study period and that prescribing rates are close to the median value relative to available European countries. However, it remains that children are still being prescribed BZDs, both for short-term and long-term use, and little is known about the long-term effects of BZD prescribing. Future studies should examine the long-term effects of BZD prescribing set against initial clinical indication for initiating and continuing BZD drugs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the HSE-PCRS for supplying the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed to the development of this manuscript. TF, KB, NM and UR conceived and designed the study; they also contributed to the analysis and preparation of the manuscript. DK and FB created the analytical model with contributions from KO and NM. KO prepared the manuscript. KB, TF, FB and KO edited the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Health Research Board (HRB) of Ireland through the HRB Centre for Primary Care Research under grant HRC/2007/1.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Z drugs are considered under the same umbrella of BZD from this point onwards in this article due to the similar effects and indications for which they are prescribed.

References

- 1.Hugtenburg JG, Heerdink ER, Egberts ACG. Increased psychotropic drug consumption by children in the Netherlands during 1995–2001 is caused by increased use of methylphenidate by boys. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2004;60:377–9. 10.1007/s00228-004-0765-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chirdkiatgumchai V, Xiao H, Fredstrom BK et al. National trends in psychotropic medication use in young children: 1994–2009. Pediatrics 2013;132:615–23. 10.1542/peds.2013-1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zito J, Safer D, Berg L et al. A three-country comparison of psychotropic medication prevalence in youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2008;25:26–32. 10.1186/1753-2000-2-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong I, Murray M, Camilleri-Novak D et al. Increased prescribing trends of paediatric psychotropic medications. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:1131–2. 10.1136/adc.2004.050468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witek MW, Rojas V, Alonso C et al. Review of benzodiazepine use in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Q 2005;76:283–96. 10.1007/s11126-005-2982-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong I, Camilleri-Novak D, Stephens P. Rise in psychotropic drug prescribing in children in the UK: an urgent public health issue. Drug Saf 2003;26:1117–18. 10.2165/00002018-200326150-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L et al. National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:679–85. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walkup JT, Labellarte MJ, Ginsburg GS. The pharmacological treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002;14:135–42. 10.1080/09540260220132653 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donoghue J, Lader M. Usage of benzodiazepines: a review. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2010;14:78–87. 10.3109/13651500903447810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilomäki R, Ilomäki E, Hakko H et al. Psychotropic medication history of inpatient adolescents—is there a rationale for benzodiazepine prescription? Addict Behav 2011;36:161–5. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutcher SP, MacKenzie S. Successful clonazepam treatment of adolescents with panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1988;8:299–301. 10.1097/00004714-198808000-00029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simeon JG, Ferguson HB. Alprazolam effects in children with anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1987;32:570–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simeon JG, Ferguson HB, Knott V et al. Clinical, cognitive, and neurophysiological effects of alprazolam in children and adolescents with overanxious and avoidant disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992;31:29–33. 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graae F, Milner J, Rizzotto L et al. Clonazepam in childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994;33:372–6. 10.1097/00004583-199403000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernstein GA, Garfinkel BD, Borchardt CM. Comparative studies of pharmacotherapy for school refusal. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990;29:773–81. 10.1097/00004583-199009000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsia Y, Neubert A, Sturkenboom MCJM et al. Comparison of antiepileptic drug prescribing in children in three European countries. Epilepsia 2010;51:789–96. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Brien CP. Benzodiazepine use, abuse, and dependence. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66(Suppl 2):28–33. 10.4088/JCP.v66n0104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paterniti S, Dufouil C, Alperovitch A. Long-term benzodiazepine use and cognitive decline in the elderly: the Epidemiology of Vascular Aging Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002;22:285–93. 10.1097/00004714-200206000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barker MJ, Greenwood KM, Jackson M et al. Persistence of cognitive effects after withdrawal from long-term benzodiazepine use: a meta-analysis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2004;19:437–54. 10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00096-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busto U, Sellers EM. Pharmacologic aspects of benzodiazepine tolerance and dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat 1991;8:29–33. 10.1016/0740-5472(91)90024-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2012. Oslo, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benzodiazepine Committee. Report of the Benzodiazepine Committee, August 2002. Dublin: Department of Health and Children, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galvin B. Use of minor tranquillisers and sedatives in the WRDTF area. Drugnet Ireland, Issue 30, Summer 2009:10–11.

- 24.The College of Psychiatry of Ireland. A consensus statement on the use of Benzodiazepines in specialist mental health services. Dublin. Council of the College of Psychiatry of Ireland; 2012.

- 25.Rickels K, Case W, Downing RW et al. Long-term diazepam therapy and clinical outcome. JAMA 1983;250:767–71. 10.1001/jama.1983.03340060045024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinhausen HC, Bisgaard C. Nationwide time trends in dispensed prescriptions of psychotropic medication for children and adolescents in Denmark. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014;129:221–31. 10.1111/acps.12155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acquaviva E, Legleye S, Auleley G et al. Psychotropic medication in the French child and adolescent population: prevalence estimation from health insurance data and national self-report survey data. BMC Psychiatry 2009;9:72 10.1186/1471-244X-9-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madsen H, Andersen M, Hallas J. Drug prescribing among Danish children: a population-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2001;57:159–65. 10.1007/s002280100279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pigott TA. Anxiety disorders in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;26:621–72, vi–vii 10.1016/S0193-953X(03)00040-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2009;32:483–524. 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gyllenberg D, Sourander A. Psychotropic drug and polypharmacy use among adolescents and young adults: findings from the Finnish 1981 Nationwide Birth Cohort Study. Nord J Psychiatry 2012;66:336–42. 10.3109/08039488.2011.644809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schirm E, Tobi H, Zito J et al. Psychotropic medication in children: a study from the Netherlands. Pediatrics 2001;108:E25 10.1542/peds.108.2.e25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furukawa TA, Streiner DL, Young LT. Antidepressant and benzodiazepine for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(1):CD001026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saber-Tehrani AS, Bruce RD, Altice FL. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions and adverse consequences between psychotropic medications and pharmacotherapy for the treatment of opioid dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37:1–11. 10.3109/00952990.2010.540279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zito J, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology. Pharmacoepidemiology: recent findings and challenges for child and adolescent psychopharmacology. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:966–7. 10.4088/JCP.v68n0622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLaughlin KA, Costello EJ, Leblanc W et al. Socioeconomic status and adolescent mental disorders. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1742–50. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Currie J, Stabile M. Socioeconomic status and child health: why is the relationship stronger for older children? Am Econ Rev 2003;93:1813–23. 10.1257/000282803322655563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]