Abstract

Marital status was found to be an independent prognostic factor for survival in various cancer types, but it hasn’t been fully studied in colorectal cancer (CRC). The Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database was used to compare survival outcomes with marital status in each stage. In total, 112, 776 eligible patients were identified. Patients in the widowed group were more frequently elderly women, more common of colon cancer, and more stage I/II in tumor stage (P < 0.001), but the surgery rate was comparable to that for the married group (94.72% VS 94.10%). Married CRC patients had better 5year cause-specific survival (CSS) than those unmarried (P < 0.05). Further analysis showed that widowed patients always presented the lowest CSS compared with that of other’ group. Widowed patients had 5% reduction 5-year CSS compared with married patients at stage I (94.8% vs 89.8%, P < 0.001), 9.4% reduction at stage II (85.9% vs 76.5%, P < 0.001), 16.7% reduction at stage III (70.6% vs 53.9%, P < 0.001) and 6.2% reduction at stage IV(14.4% VS 8.2%, P < 0.001). These results showed that unmarried patients were at greater risk of cancer specific mortality. Despite favorable clinicpathological characteristics, widowed patients were at highest risk of death compared with other groups.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, marital status, SEER, survival analysis

INTRODUCTION

Married individuals enjoy longer overall survival and lower mortality for many major causes of death compared with those who have never married, separated, widowed, or divorced [1–3]. Extensive research has shown that marital status is an independent prognostic factor of survival in various cancer types [4–9]. In a larger population-based study on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database indicated that unmarried patients are at significantly higher risk of presentation with metastatic cancer, undertreatment, and death resulting from their cancer in ten leading causes of cancer-related death [4]. Similarly, Johansen et al. [8] and Wang et al. [9] reported that patients with colon cancer who were married at the date of diagnosis survived significantly longer than those who had never been married. However, the study by Johansen et al. compared survival outcomes of married and unmarried individuals without differentiating among single, divorced and widowed status. Additionally, marital statuses in the population, stage at presentation, mortality, as well as therapy options, have changed in more recent years. This change may be related to possible increases or decreases in the proportion of married and unmarried individuals and their effect on cause-specific survival (CSS) [10, 11]. Moreover, two reported reasons of poor survival among unmarried patients were delayed diagnosis and undertreatment. If this were true, marital status may have no effect on early CRC, because these patients do not require adjuvant therapy. Given that CRC is one of the most common malignancies and is ranked as the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the USA [12] and marriage is an important aspect of adult life, it is important to explore the relationship between marital status and CRC and the potential underlying mechanisms. In this study, we used data from the SEER cancer-registry program of individuals diagnosed between 2004 and 2008 to explore in detail what aspects of marital status affects cancer survival. Our hypothesis was that the unmarried subgroup of CRC patients may differ in terms of survival outcomes.

RESULTS

Patient baseline characteristics

A total of 112, 776 eligible patients were identified during the 4-year study period, including 57, 921 male and 54, 855 female patients. Of these, 62, 255 (55.20%) were married, 21, 279 (18.87%) were widowed, and 15, 043 (13.34%) had never married. The 1, 044 (0.93%) individuals who were separated and 10, 155 (9.00%) who were divorced were grouped together in the divorced/separated group in our study [9]. Patients in the widowed group had the highest proportion of women, more common of colon cancer, more prevalence of elderly patients (≥60 years), and more tumor at stage I/II, all of which were statistically significant (P < 0.001). The rate of surgery performed was comparable between the married and widowed groups (94.72% vs 94.10%), but higher than that in the never married (91.31%) and divorced/separated (92.47%) group. Patient demographics and pathological features are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and tumor characteristics of patients in SEER database.

| Characteristic | Total | Married | Widowed | Never married | Divorced/Separated | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 112776) | (n = 62255) N (%) | (n = 21279) N (%) | (n = 15043) N (%) | (n = 11199) N (%) | ||

| Sex | < 0.001 | |||||

| male | 57921 | 39890(61.1) | 4539(21.3) | 8212(54.6) | 5280(47.1) | |

| female | 54855 | 25365(38.9) | 16740(78.7) | 6831(45.4) | 5919(52.9) | |

| Primary Site | < 0.001 | |||||

| Colon | 94496 | 54139(83.0) | 18913(88.9) | 12396(82.4) | 9048(80.8) | |

| Rectum | 18280 | 11116(17.0) | 2366(11.1) | 2647(17.6) | 2151(19.2) | |

| Age | < 0.001 | |||||

| <60 | 35126 | 22522(34.5) | 874(4.1) | 7415(49.3) | 4315(38.5) | |

| ≥60 | 77650 | 42733(65.5) | 20405(95.9) | 7628(50.7) | 6884(61.5) | |

| Race | < 0.001 | |||||

| White | 90608 | 53736(82.3) | 17630(82.9) | 10557(70.2) | 8685(77.6) | |

| Black | 12729 | 5329(8.2) | 2204(10.4) | 3333(22.2) | 1863(16.6) | |

| Other* | 9136 | 6001(9.2) | 1409(6.6) | 1104(7.3) | 622(5.6) | |

| Unknown | 303 | 189(0.3) | 36(0.2) | 49(0.3) | 29(0.3) | |

| Pathological grading | < 0.001 | |||||

| High/Moderate | 83291 | 48680(70.6) | 15418(72.5) | 11079(73.6) | 8114(72.5) | |

| Poor/Anaplastic | 21969 | 12368(19.0) | 4588(21.6) | 2773(18.4) | 2240(20.0) | |

| Unknown | 7516 | 4207(6.4) | 1273(6) | 1191(7.9) | 845(7.5) | |

| Histotype | < 0.001 | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 102078 | 59181(90.7) | 19149(90.0) | 13580(90.3) | 10168(90.8) | |

| Mucinous cell | 9309 | 5243(8) | 1919(9.0) | 1247(8.3) | 900(8.0)) | |

| Signet ring cell | 1389 | 831(1.3) | 211(1.0) | 216(1.4) | 131(1.2) | |

| TNM stage | < 0.001 | |||||

| I | 23689 | 14785(22.7) | 4251(20.0) | 2562(17.0) | 2091(18.7) | |

| II | 32877 | 18387(28.2) | 7084(33.3) | 4223(28.1) | 3183(28.4) | |

| III | 31746 | 18575(28.5) | 5861(27.5) | 4171(27.7) | 3139(28.0) | |

| IV | 24464 | 13508(20.7) | 4083(19.2) | 4087(27.2) | 2786(24.9) |

Other includes American Indian/Alaska native, Asian/Pacific Islander, etc.

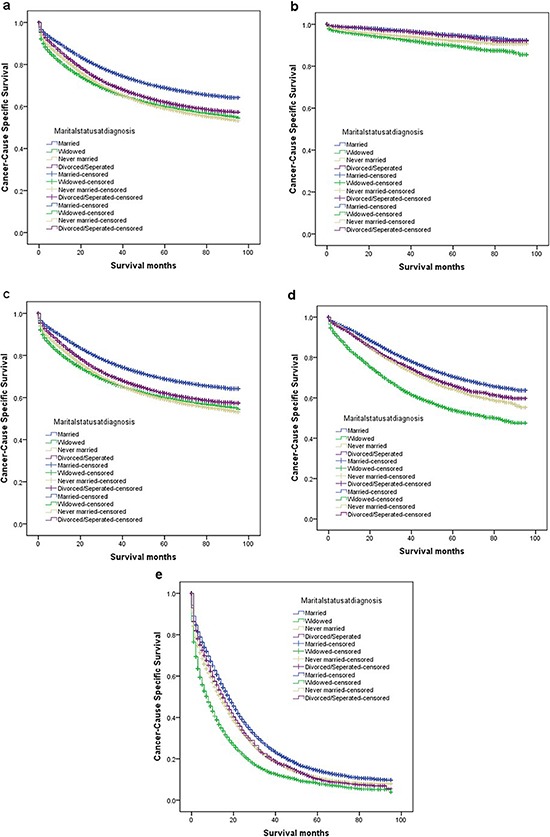

Effect of marital status on CSS in the SEER database

The overall 5-year CSS was 68.9% in the married group, 60.0% in the widowed group, 59.2% in the never married group, and 60.0% in the divorced/separated group, which were all significantly different according to the univariate log-rank test (P < 0.001) (Figure 1). Additionally, elderly patients (P < 0.001), male sex (P < 0.001), black ethnicity (P < 0.001), poor or undifferentiated tumor grade (P < 0.001), mucinous or signet-ring cancer (P < 0.001), higher American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage (P < 0.001), and no surgery (P < 0.001) were identified as significant risk factors for poor survival on univariate analysis (Table 2). When multivariate analysis with Cox regression was performed, all seven variables were validated as independent prognostic factors. These included age (≥60 years, hazard ratio (HR) 1.522, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.487–1.558), ethnicity(black, HR 1.182, 95%CI 1.147–1.218; others, HR 0.899, 95% CI 0.865–0.935), pathological grading(poor or undifferentiated tumor, HR 1.457, 95% CI 1.422–1.492; unknown, HR 1.689, 95% CI 1.623–1.739), histologic type (mucinous/signet ring cell, HR 1.091, 95% CI 1.056–1.127), AJCC stage(stage II, HR 2.723, 95% CI 2.570–2.885; stage III, HR 5.897, 95% CI 5.581–6.231; stage IV, HR 30.707, 95% CI 29.101–32.401), surgery (no surgery performed, HR 2.123, 95%CI 2.053–2.196), marital status(widowed, HR 1.485, 95%CI 1.445–1.526; never married, HR 1.307, 95%CI 1.269–1.347; divorced/separated, HR1.181, 95% CI 1.142–1.222).

Figure 1. Survival curves in colorectal patients according to marital status.

(a) stage I-IV: χ2 = 1096.367, P < 0.001; (b) stage I: χ2 = 154.618, P < 0.001; (c) stage II: χ2 = 346.777, P < 0.001; (d) stage III: χ2 = 646.624, P < 0.001; (e) stage IV: χ2 = 602.869, P < 0.001.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate survival analysis for evaluating the influence of marital status on colorectal cause-specific survival in SEER database.

| Variable | 5-year CCS | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log rank χ2 test | P | HR(95%CI) | P | ||

| Primary Site | 0.944 | 0.331 | NI | ||

| Colon | 65.5% | ||||

| Rectum | 64.3% | ||||

| Sex | 1.768 | 0.184 | NI | ||

| Male | 64.9% | ||||

| Female | 65.7% | ||||

| Age | 195.03 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| <60 | 67.4% | Reference | |||

| ≥60 | 64.3% | 1.522(1.487–1.558) | |||

| Race | 406.282 | <0.001 | |||

| White | 66.1% | Reference | <0.001 | ||

| Black | 57.3% | 1.182(1.147–1.218) | |||

| Other* | 68.2% | 0.899(0.865–0.935) | |||

| Grade | 5557.256 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| High/Moderate | 70.6% | Reference | |||

| Poor/Anaplastic | 52.3% | 1.457(1.422–1.492) | |||

| Unknown | 43.6% | 1.689(1.623–1.739) | |||

| Histotype | 284.69 | <0.001 | 0.571 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 66.1% | Reference | |||

| Mucinous/signet ring cell | 57.9% | 1.009(0.977–1.043) | |||

| TNM Stage | 62866.96 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| I | 93.6% | Reference | |||

| II | 82.8% | 2.723 (2.570–2.885) | |||

| III | 66.4% | 5.897(5.581–6.231) | |||

| IV | 12.3% | 30.707(29.101–32.401) | |||

| Marital Status | 1096.367 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Married | 68.9% | Reference | |||

| Windowed | 60.0% | 1.485(1.445–1.526) | |||

| Never married | 59.2% | 1.307(1.269–1.347) | |||

| Divorced/Separated | 62.0% | 1.181(1.142–1.222) | |||

Other includes American Indian/Alaska native, Asian/Pacific Islander, and unknown.

NI: not included in the multivariate survival analysis.

Subgroup analysis for evaluating the effect of marital status according to AJCC stage

One reason previously reported of poor prognosis of unmarried patients is delayed diagnosis. If this is true, once the tumor is diagnosed, marital status should not affect CSS. Another reason reported is undertreatment. If so, patients at an early stage should not be affect by marital status because they do not require adjunctive therapy. Therefore, we made further analysis of the effects of marital status on survival in each tumor stage. We observed three interesting findings. First, marital status was an independent prognostic factor in each tumor stage both in univariate and multivariate analysis (P < 0.001). Second, patients in the widowed group always had the lowest survival rate when compared with patients in the other groups. Widowed patients had 5% reduction in 5-year CSS compared with married patients at stage I (94.8% vs 89.8%, P < 0.001), 9.4% reduction at stage II (85.9% vs 76.5%, P < 0.001), 16.7% reduction at stage III (70.6% vs 53.9%, P < 0.001) and 6.2% reduction at stage IV(14.4% vs 8.2%, P < 0.001). Third, the difference between the divorced/separated and never married group was not apparent. Compared with patients in the never married group, patients in the divorced/separated group at stage I-III had an increase of 1.3–2.4% in 5-year CSS and, a 0.6% decreased in survival at stage IV Table 3.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of marital status on colorectal cancer cause specific survival based on different cancer stage.

| Variable | 5-year CCS | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log rank χ2 test | P | HR(95% CI) | P | ||

| TNM Stage | |||||

| Stage I | |||||

| Marital status | 154.618 | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 94.8% | Reference | |||

| Widowed | 89.8% | 1.722(1.522–1.947) | <0.001 | ||

| Never married | 92.1% | 1.592(1.355–1.872) | <0.001 | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 94.5% | 1.077(0.883–1.313) | 0.463 | ||

| Stage II | |||||

| Marital status | 346.77 | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 85.9% | Reference | |||

| Widowed | 76.5% | 1.532(1.434–1.637) | <0.001 | ||

| Never married | 80.5% | 1.555(1.434–1.688) | <0.001 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 81.8% | 1.314(1.197–1.441) | <0.001 | ||

| Stage III | |||||

| Marital status | 646.624 | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 70.6% | Reference | |||

| Widowed | 53.9% | 1.575(1.498–1.656) | <0.001 | ||

| Never married | 64.4% | 1.332(1.254–1.414) | <0.001 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 66.1% | 1.182(1.105–1.266) | <0.001 | ||

| Stage IV | |||||

| Marital status | 602.869 | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 14.4% | Reference | |||

| Widowed | 8.2% | 1.400(1.345–1.456) | <0.001 | ||

| Never married | 10.9% | 1.228(1.180–1.277) | <0.001 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 10.3% | 1.151(1.101–1.204) | <0.001 | ||

P-values refer to comparisons between two groups and were adjusted for age, race, pathological grading, and tumor histologic type as covariates.

NI: not included in the multivariate survival analysis.

DISCUSSION

Although the impact of marriage on CRC survival has been studied using both SEER as well as other country-specific cancer databases [4, 8, 9], no research has been performed on stage by stage comparisons of the effects of marital status on patient survival or focused on the heterogeneity of unmarried patients. Our study indicated that marital status was an independent prognostic factor in each TNM stage. Additionally, although patients in the widowed group had the highest percentage of early tumor stage (I/II), they had the worst survival when compared with those in the other group.

One hypothesis to explain the unfavorable prognosis of unmarried individuals is undertreatment. However, in any current guideline for CRC clinical practice, adjunctive therapy is not recommended for patients in stages I patients and II without risk factors. We found that patients in the widowed group still had a disadvantage of 5% in stage I and 9.4% in stage II regarding the 5-year CSS compared with those in the married group. Moreover, the rate of surgical resection was comparable between both the married and widowed groups. None of these finding could be explained by the hypothesis of undertreatment. Johansen et al, also found that the observed effect of marital status could not be attributed to treatment options for accessing to health care services is provided free in Denmark during the period under study [8]. Interestingly, delayed diagnosis was considered as another reason for poor prognosis in unmarried patients [4, 13, 14]. However, in our study group, the percentage of patients with CRC in stage I and II CRC patients was highest in the widowed group with 53.3% compared with 50.9%, 45.1%, and 47.1% in the married, never married, and divorced/separated group, respectively. Obviously, this result is paradoxical given the poor survival outcomes in the widowed group.

Our data revealed that unmarried patients have a survival disadvantage that persists in each TNM stage. The relationship between marital status and survival can be explained hypothetically by psychosocial factors that are independent of tumor characteristics and extent of treatment. It has been proposed that decreased psychosocial support and psychological stress alter immune function and contribute to tumor progression and mortality [15–17]. Levy et al. reported that a perceived lack of social support was associated with lower activity of natural killer cells [18]. Chronic stress may elicit prolonged secretion of cortisol [19], that triggers a counterregulatory response of white blood cells by downregulating their cortisol receptors. This downregulation, in turn, reduces the cell’ capacity to respond to anti-inflammatory signals and allows cytokine-mediated inflammatory processes to flourish [20], which have been validated as poor prognostic factors in CRC [21, 22]. Conversely, cortisol levels seem to be lower in patients with cancer who have adequate support networks, and diurnal cortisol patterns have been linked with natural-killer cell count and survival in patients with cancer [23, 24]. Additionally, depression and quality of life have been related to VEGF, which may stimulate endothelial cell migration, proliferation and proteolytic activity [25], in CRC [26]. Additionally, some other neuroendocrine mediators and cytokines present in depression and stress are linked with cancer metastasis [17]. Unrecognized clinical depression is strongly associated with poor adherence to medical treatment [27]. Meta-analyses of the impact of depression on cancer mortality confirm increased death rates between 19% and 39% [28, 29]. The loss of social support or the inability to cope with stress in the widowed groups seems very apparent, and may lead to excess mortality [30].

Age is another factor that should be considered fully. The proportion of elderly patients (≥60 years) in the widowed group was extremely high (95.9%), which may be another reason for extremely poor survival in this group. Age itself is a prognostic factor in CRC [31, 32] that can be explained by aging impaired immune response, increased oxidative stress, shortening of telomeres, accumulation of senescent cells [33, 34].

This study adds to the current knowledge by answering more in-depth research questions about marital status and prognosis through the analysis of data from the large population-based SEER database. However, it had several potential limitations. First, the SEER database only provide the marital status at diagnosis. Whether the marital status changed after diagnosis is unknown, and this change may also affect patient’ survival. Second, SEER database lacks information of education, income status, insurance status, socioeconomic status and quality of marriage, which might confound the explanation of the disparity in survival between marital groups. For example, marital distress has long term immune consequences and enhances the risk of a variety of health problems [35]. Third, information on therapy options (surgical resection or palliative therapy), subsequent therapy, co-morbidities and recurrence is also lacking. Fourth, we hypothesized that psychosocial factors may be the main reasons for poor survival of unmarried patients, but we performed a retrospectively analysis using a public database, and we could not performed psychological tests to validate our hypothesis.

Despite these potential limitations, our study results confirmed that unmarried patients are at greater risk of cancer-specific mortality. Moreover, we indicated that the unmarried patients groups was heterogeneous, and the widowed patients were always at the highest risk of death of cancer than those in other groups. Psychosocial factors may be the main reasons for poor survival outcomes in unmarried patients. Physicians caring for unmarried patients with CRC, especially those who are widowed should be aware of their poorer outcomes. Additionally, social support systems should provide closer cares and interventions for these patients to help reduce the significant survival differences between married and unmarried patients with CRC cancer.

METHODS

Patient selection in the SEER database

The SEER Cancer Statistics Review (http://seer.cancer.gov/data/citation.html), a report on the most recent cancer incidence, mortality, survival, prevalence, and lifetime risk statistics, is published annually by the Data Analysis and Interpretation Branch of the National Cancer Institute, USA. The current SEER database consists of 17 population-based cancer registries that represent approximately 28% of the population in the US. It contains no identifiers and is widely used for studies of the relationship between marital status and survival outcomes of patients with cancer [4, 5, 7, 9–11].

Using the SEER-stat software (SEER*Stat 8.1.5), we searched for patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2008 with single primary CRC and a known marital status. Histological type were limited to adenocarcinoma (8150/3, 8210/3, 8261/3, 8263/3), mucinous adenocarcinoma (8480/3), and signet ring cell carcinoma (8490/3). Patients were excluded if age at diagnosis was less than 18 years, they had undefined TNM stage, had more than one primary cancer but the CRC wasn’t the first one, had unknown cause of death or unknown survival months.

Statistical analysis

Age, sex, ethnicity, extension of primary tumor invasion, lymph nodes status, histological grade, survival time, and CSS were extracted from the SEER database. All cases were restaged according to the criteria described in the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (7th edition, 2010). Within the SEER database, marital status of the patient is recorded at the time of diagnosis. Marital status is coded as married, divorced, widowed, separated, and never married. Individuals in the separated and divorced group were clustered together as the divorced/separated group in this study.

Patient baseline characteristics were compared with the χ2 test, as appropriate. The rate of CRC death was compared between groups using the Kaplan–Meier method. Multivariable Cox regression models were built for analysis of risk factors for survival outcomes. The primary endpoint of this study was CSS, which was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of cancer specific death. Deaths attributed to CRC were treated as events and deaths from other causes were treated as censored observations. All of statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package SPSS for Windows, version 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set at two-sided P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. This study was partially supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81372646, 81101586).

Footnotes

Author contributions

QGL, XXL and SJC conceived of and designed the study. LG and LL performed the analyses. LG and LL prepared all figures and tables. QGL, XXL, and SJC wrote the main manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaplan RM, Kronick RG. Marital status and longevity in the United States population. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2006;60:760–765. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.037606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu YR, Goldman N. Mortality differentials by marital status: an international comparison. Demography. 1990;27:233–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikeda A, Iso H, Toyoshima H, Fujino Y, Mizoue T, Yoshimura T, Inaba Y, Tamakoshi A, Group JS. Marital status and mortality among Japanese men and women: the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. BMC public health. 2007;7:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, Mendu ML, Koo S, Wilhite TJ, Graham PL, Choueiri TK, Hoffman KE, Martin NE, Hu JC, Nguyen PL. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3869–3876. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denberg TD, Beaty BL, Kim FJ, Steiner JF. Marriage and ethnicity predict treatment in localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1819–1825. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torssander J, Erikson R. Marital partner and mortality: the effects of the social positions of both spouses. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2009;63:992–998. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.089623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelles JL, Joseph SA, Konety BR. The impact of marriage on bladder cancer mortality. Urologic oncology. 2009;27:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johansen C, Schou G, Soll-Johanning H, Mellemgaard A, Lynge E. Influence of marital status on survival from colon and rectal cancer in Denmark. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:985–988. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L, Wilson SE, Stewart DB, Hollenbeak CS. Marital status and colon cancer outcomes in US Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registries: does marriage affect cancer survival by gender and stage? Cancer epidemiology. 2011;35:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rippentrop JM, Joslyn SA, Konety BR. Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: evaluation of data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer. 2004;101:1357–1363. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kravdal H, Syse A. Changes over time in the effect of marital status on cancer survival. BMC public health. 2011;11:804. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osborne C, Ostir GV, Du X, Peek MK, Goodwin JS. The influence of marital status on the stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older women with breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2005;93:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-3702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nayeri K, Pitaro G, Feldman JG. Marital status and stage at diagnosis in cancer. New York state journal of medicine. 1992;92:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garssen B, Goodkin K. On the role of immunological factors as mediators between psychosocial factors and cancer progression. Psychiatry research. 1999;85:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sklar LS, Anisman H. Stress and coping factors influence tumor growth. Science. 1979;205:513–515. doi: 10.1126/science.109924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno-Smith M, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK. Impact of stress on cancer metastasis. Future oncology. 2010;6:1863–1881. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy SM, Herberman RB, Whiteside T, Sanzo K, Lee J, Kirkwood J. Perceived social support and tumor estrogen/progesterone receptor status as predictors of natural killer cell activity in breast cancer patients. Psychosomatic medicine. 1990;52:73–85. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiological reviews. 2007;87:873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller GE, Cohen S, Ritchey AK. Chronic psychological stress and the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines: a glucocorticoid-resistance model. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2002;21:531–541. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Formica V, Luccchetti J, Cunningham D, Smyth EC, Ferroni P, Nardecchia A, Tesauro M, Cereda V, Guadagni F, Roselli M. Systemic inflammation, as measured by the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, may have differential prognostic impact before and during treatment with fluorouracil, irinotecan and bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2014;31:166. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton TD, Leugner D, Kopciuk K, Dixon E, Sutherland FR, Bathe OF. Identification of prognostic inflammatory factors in colorectal liver metastases. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:542. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sephton SE, Lush E, Dedert EA, Floyd AR, Rebholz WN, Dhabhar FS, Spiegel D, Salmon P. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of lung cancer survival. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2013;30:S163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:994–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrara N, Davis-Smyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocrine reviews. 1997;18:4–25. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma A, Greenman J, Sharp DM, Walker LG, Monson JR. Vascular endothelial growth factor and psychosocial factors in colorectal cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2008;17:66–73. doi: 10.1002/pon.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009;115:5349–5361. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychological medicine. 2010;40:1797–1810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martikainen P, Valkonen T. Mortality after the death of a spouse: rates and causes of death in a large Finnish cohort. American journal of public health. 1996;86:1087–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chagpar R, Xing Y, Chiang YJ, Feig BW, Chang GJ, You YN, Cormier JN. Adherence to stage-specific treatment guidelines for patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:972–979. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serra-Rexach JA, Jimenez AB, Garcia-Alhambra MA, Pla R, Vidan M, Rodriguez P, Ortiz J, Garcia-Alfonso P, Martin M. Differences in the therapeutic approach to colorectal cancer in young and elderly patients. Oncologist. 2012;17:1277–1285. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duray A, Demoulin S, Petermans J, Moutschen M, Saussez S, Jerusalem G, Delvenne P. Revue medicale de Liege. 2014;69:276–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Geest KS, Abdulahad WH, Tete SM, Lorencetti PG, Horst G, Bos NA, Kroesen BJ, Brouwer E, Boots AM. Aging disturbs the balance between effector and regulatory CD4+ T cells. Experimental gerontology. 2014;60C:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaremka LM, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Marital distress prospectively predicts poorer cellular immune function. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2713–2719. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]