Dodds et al. (1) present a universal positivity bias—in 10 human languages—that they claim is independent of word frequency. This result contradicts previous findings (2, 3) in which a relationship between word happiness and frequency is reported for a variety of languages and large-scale datasets. To better understand this contradiction, we reanalyze the labMT (language assessment by Mechanical Turk) data produced in Dodds et al. (1) against a larger reference lexicon (3). Our reanalysis shows that the data used in Dodds et al. (1) does not support their claims. The code required to reproduce our analysis is available upon request.

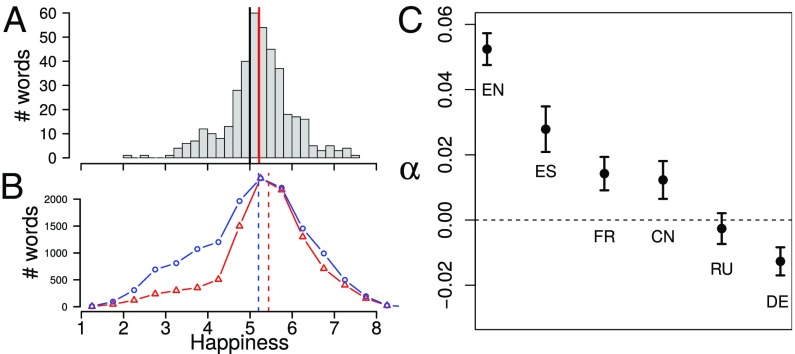

The online setup of Dodds et al. (1) does not control for acquiescence (2), allowing for a positive measurement bias (3). LabMT includes function words like prepositions (“of”) and articles (“the”), which are not expected to express happiness or unhappiness, as mentioned in Dodds et al. (1). This way, the 399 function words of LIWC (linguistic inquiry and word count) (4) serve as a gold standard of neutral emotional content, allowing us to test if there is a positive measurement bias in labMT. Fig. 1A shows the distribution of function word happiness in labMT, revealing that the measurement method introduces a positive bias in which even neutral words are scored above 5 (Wilcoxon P < 10−11, median = 5.25).

Fig. 1.

(A) Distribution of happiness values for LIWC function words. The vertical red line shows the median of the distribution. (B) Distributions and medians of happiness values for English in Dodds et al. (1) (red) and in the reference lexicon (3) (blue). (C) Robust regression estimates and confidence intervals of α when using logarithm frequency in Google Books since 1990 instead of a rank transformation for English (EN), Spanish (ES), French (FR), Chinese (CN), Russian (RU), and German (DE).

The response format used in Dodds et al. (1) is composed of a scale of emoticons. This approach introduces a measurement bias because nonsmiling facial expression is perceived as slightly negative (5). We capture this bias by comparing the English labMT with a reference lexicon (3), produced in a very similar experiment also using Amazon MT with the same scale and definition of word happiness, but with numeric scales instead of emoticons. Fig. 1B shows that word happiness in labMT is higher than in the reference lexicon (Wilcoxon P < 10−15, median difference = 0.28). This difference also exists in the intersection between lexica, composed of 4,502 words, for which we calculated the difference between the happiness scores in labMT and in the reference lexicon. The result is a positive measurement bias even at the level of individual words (t test P < 10−15, mean = 0.07).

The independence of happiness from frequency reported by Dodds et al. (1) is based on a rank transformation of frequency, which loses information of the empirical word frequencies. We reanalyze labMT and Google Books in six languages using a loglinear model havg = α log(f) + β, using the actual frequency rather than the rank. Fig. 1C shows the estimates of α, revealing a significant and sizable dependence for four languages. For English, the increase of happiness on the frequency range is 1.06, an effect much larger than after the rank transformation of Dodds et al. (1), and its associated information loss. This analysis shows a language-dependent relationship between word happiness and frequency, and that the reported “self-similarity” of Dodds et al. (1) is far from being universal.

In summary, our reanalysis shows: (i) that the reported positivity bias is explained by a measurement bias rather than a universal feature of human language, and (ii) that the reported independence between word happiness and frequency is an artifact of the data processing. However, this does not subtract importance from the methodological contribution of Dodds et al. (1), namely a multilingual lexicon of happiness that will be of key importance for future studies of human emotions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Simon Schweighofer for useful discussions. This study was supported in part by Swiss National Science Foundation Grant CR21I1_146499 (to D.G. and F.S.)

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dodds PS, et al. Human language reveals a universal positivity bias. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(8):2389–2394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411678112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia D, Garas A, Schweitzer F. Positive words carry less information than negative words. EPJ Data Science. 2012;1(1):3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warriner AB, Kuperman V. Affective biases in English are bi-dimensional. Cogn Emotion. 2014:1–21. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2014.968098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pennebaker JW, Chung CK, Ireland M, Gonzales A, Booth RJ. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC2007. LIWC.net; Austin, TX: 2007. Available at www.liwc.net/LIWC2007LanguageManual.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee E, Kang JI, Park IH, Kim J-J, An SK. Is a neutral face really evaluated as being emotionally neutral? Psychiatry Res. 2008;157(1-3):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]