Abstract

Objectives

This study was designed to investigate changes in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with acromegaly in Korea after medical treatment with octreotide LAR using the validated Korean version of the acromegaly quality of life questionnaire (AcroQoL).

Design

A prospective, open-label, single-arm study.

Setting

11 tertiary centres in Korea.

Participants

58 Korean patients (aged 21–72 years) who were newly diagnosed with acromegaly between 2009 and 2012 were prescribed octreotide LAR 20 mg at the time of enrolment. During 24 weeks of observation, AcroQoL survey questionnaires and measurement of growth hormone insulin-like growth factor 1(GH/IGF-I) were performed at baseline, week 12 and week 24.

Main outcome measures

We assessed the HRQoL of Korean patients with acromegaly after medical treatment with octreotide LAR using the validated Korean version of the AcroQoL questionnaire.

Results

Patients had a mean age of 47.2 years (29 males), and GH and IGF-I significantly decreased during the first 12 weeks (GH: 4.8 vs 1.9 μg/L, p<0.001; IGF-I: 497 vs 265 μg/L, p<0.001), but showed insignificant change at week 24 (GH: 2.3 μg/L; IGF-I: 294 μg/L). Only AcroQoL scores for the psychological appearance subdomain showed a significant increase during the entire 24 weeks (p<0.05). The change in the psychological appearance subdomain of AcroQoL scores demonstrated a significant but weak negative correlation with change in IGF-I levels (r=−0.282, p=0.039). When patients were divided into two groups according to their disease activity at week 24 (controlled vs uncontrolled), there was no difference in AcroQoL scores, but the psychological appearance subdomain of the two groups appeared to change differently over the entire 24-week period (p=0.047).

Conclusions:

Medical treatment with octreotide LAR in patients with acromegaly has a limited contribution to HRQoL as assessed by the AcroQoL.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study which applied acromegaly quality of life questionnaire (AcroQoL) to Korean patients.

This study highlights the limited contribution of medical treatment with octreotide LAR in Korean patients with acromegaly to HRQoL as assessed by the AcroQoL.

The limitation of this study is that the final analyses included less patients than initially calculated.

Introduction

Acromegaly is a rare chronic disease mainly caused by hypersecretion of growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I). The main cause of acromegaly is a GH-producing pituitary adenoma, and it is often associated with increased mortality and morbidity due to its various complications such as hypertension, insulin resistance or diabetes mellitus, cardiomyopathy and sleep apnoea.1 Thus, the goal of treatment is to ameliorate excessive production of GH and IGF-I2 and to manage these complications,3 which may restore mortality and morbidity to a level similar to that of the general population.4 The first-line treatment is usually a trans-sphenoidal approach, but medical treatment may be required to achieve disease control when surgery is not successful or indicated.2 Random serum GH level below 2.5 μg/L and normalisation of IGF-I after treatment are known to reduce the mortality of patients to that of the general population.5 6 However, disease control does not always guarantee the improvement of symptoms such as morphological changes in bone and cartilage,7 which play a substantial role in the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with acromegaly.

Recently, in addition to the improvement of biochemical markers such as GH and IGF-I, there have been numerous endeavours to evaluate and improve the individual HRQoL of patients with acromegaly. In 2002, Webb et al8 first developed an acromegaly quality of life questionnaire (AcroQoL) which attempted to evaluate the HRQoL of patients with acromegaly, and also demonstrated that their HRQoL was remarkably impaired when compared with the general population. Since then, there have been a number of additional studies assessing the HRQoL of patients with acromegaly using AcroQoL.7 9–12 The aim of this study was to assess the HRQoL of Korean patients with acromegaly after medical treatment with octreotide LAR using the validated Korean version of the AcroQoL questionnaire.

Methods

Patients

This study was conducted as a prospective, open-label, single-arm multicentre study. Between 2009 and 2012, seventy-two patients with acromegaly attending routine care at one of 11 tertiary centres in Korea were enrolled in this study. The inclusion criteria were patients with a confirmed diagnosis of acromegaly and evidence of active disease despite previous medical, surgical and/or radiotherapy. Patients with known hypersensitivity or allergy to octreotide LAR, or patients receiving chronic systemic glucocorticoid therapy at pharmacological dose, were excluded. Also, patients with previous histories that may preclude them from completing the study protocol, such as drug or alcohol abuse, psychiatric disorders including dementia, pregnant or breast feeding patients, or patients intending to become pregnant during the study period, were excluded. The diagnosis of acromegaly was confirmed when an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) failed to suppress GH levels below 1.0 μg/L, and when the IGF-I level was above the upper normal range for age,2 defined as >1.0× the upper limit of normal for age. All of the enrolled patients were scheduled to receive octreotide LAR 20 mg intramuscularly weekly for 24 weeks. GH and IGF-I levels were measured at weeks 0, 12 and 24. A dose escalation to octreotide LAR 30 mg was permitted, but not mandatory, at week 12, based on biochemical response (GH > 2.5 μg/L and/or IGF-I above the upper normal range for age). Dose decreases to octreotide LAR 10 mg were also permitted for tolerability and in the case of improved GH (<1.0 μg/L) and IGF-I levels (within the normal range for age) as well as symptom improvement.

According to the previous report by Webb et al, the change of the AcroQoL global score between baseline and 6 months after treatment was from 52.84±19.52 to 67.97±18.46.6 On the basis of this result, we estimated that the change of AcroQoL after medical treatment with octreotide LAR would be 10 and the SD was set to be 27 when assuming that the correlation between baseline and 6 months after treatment would be 0. Thus, the sample size in this study was calculated to be at least more than 70 when the level of significance was less than 5% with a statistical power of 90%.

AcroQoL

AcroQoL was first proposed and published in 2002. AcroQoL contains 22 survey questions which are divided into two scales which measure physical and psychological aspects. Psychological aspects are further divided into two subdomains: appearance and personal relationships. Each question has five possible responses scored from 1 (worst) to 5 (best), and the higher the total score, the better was the quality of life (QoL) expected. The results are quoted as a percentage, with a minimum score of 0% and a maximum score of 100%. First developed in Spanish, a number of translated versions in other languages, including English, are available at present.8

Following the previously recommended standard methodology,13 the Spanish version of the AcroQoL questionnaire was translated into Korean by two professional translators bilingual in Korean and Spanish. This version underwent the backward translation independently by another professional translator to ascertain equivalent significance in both languages. This translated version was presented to five Korean-speaking patients with acromegaly to evaluate its comprehensiveness, clarity, cultural relevance and suitable wording. Finally, this version was certified by Dr Susan Webb, the original developer of AcroQoL, for its accuracy and completeness of the translation. All of the enrolled patients in this study were asked to complete the AcroQoL questionnaire at weeks 0 (baseline), 12 and 24.

Measurement of GH and IGF-I

Serum GH concentration was measured using commercial radioimmunoassay (RIA) kits (hGH-RIACT, Cisbio Bioassays, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA). Standards and controls for this assay were calibrated against the second WHO IRP IS 98/574. The sensitivity of this kit was 0.01 μg/L, with an intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) of 3.8–5% and an inter-assay CV of 1.3–2.1%. Serum IGF-I concentrations were determined by commercial immunoradiometric assay kits (IGF-I NEXT IRMA CT, IDA S.A., Liège, Belgium). The minimum detectable concentration of IGF-I was 1.25 μg/L. The intra-assay and inter-assay CVs were 2.6–4.4% and 7.4–9.1%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data were described as the median (range). Changes in GH and IGF-I levels as well as the AcroQoL score over the 24 weeks were analysed by the Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test. The Jonckheere-Terpstra test was also applied to investigate the ordered difference of AcroQoL scores during the 24 weeks of the study period. At the end of the study period, all subjects were divided into either the controlled or uncontrolled group based on remission criteria proposed previously,2 and the linear mixed model was used to observe the changes in the AcroQoL scores of the two groups over the entire 24 weeks and whether these changes differed between the two groups. The same analysis was performed between those who received radiotherapy and those who did not. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated between the change in IGF-I levels and AcroQoL scores. All statistical analyses were performed with PASW (V.18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA), and a p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Results

Out of 72 patients, 14 were excluded for reasons such as screening failure (n=7) and dropout (n=7), and 58 were included in the final analyses. Of these 58 patients, 29 were male, and the median age was 47 years, with a range between 21 and 72 years (table 1). At baseline, 40 patients had received pituitary surgery and a further 12 had undergone additional γ-knife surgery (GKS) and/or conventional radiation therapy. There was one patient who received GKS only, and five who had no history of treatment. None of the enrolled patients demonstrated symptoms of hypopituitarism or required hormonal replacement therapy during the study period. The baseline median GH level was 4.8 μg/L (range, <1 to 184.6), and the IGF-I level was 497 μg/L (range, 111–1231). Those who had baseline GH levels below 2.5 μg/L (n=14) failed to suppress GH secretion during the 75 g OGTT. In addition, the patient with very low IGF-I (111 μg/L) also demonstrated the failure of GH secretion during the OGTT and accompanying uncontrolled diabetes which may explain the exceptionally low IGF-I level. Median GH and IGF-I levels decreased significantly after the first 12 weeks (4.8–1.9 μg/L for GH and 497–265 μg/L for IGF-I), but post hoc analyses revealed that there was no further significant improvement of these two markers in the last 12 weeks (table 2). There were 21 patients who had a dose escalation of octreotide LAR to 30 mg and one of them demonstrated a further decrease of GH/IGF-I levels to achieve the disease control. Finally, 22 patients satisfied the biochemical criteria of disease control at week 24.

Table 1.

Demographic data of patients with acromegaly

| Variables | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 58 |

| Age (years) | 47 (21–72) |

| Sex (n, male) | 29 |

| Years from diagnosis | 6.0 (<1–30) |

| Previous treatment for acromegaly | |

| Surgery alone (n) | 40 |

| GKS alone (n) | 1 |

| CRT alone (n) | 0 |

| Surgery+GKS±CRT (n) | 12 (surgery+GKS=9/surgery+GKS+CRT=3) |

| Neither (n) | 5 |

| Baseline GH/IGF-I | |

| GH (μg/L, basal) | 4.8 (<1–184.6) |

| IGF-I (μg/L) | 497 (111–1231) |

| Associated complications | |

| Diabetes mellitus (n) | 19 |

| Hypertension (n) | 26 |

| Hyperlipidaemia (n) | 10 |

Data are displayed as the median (range).

CRT, conventional radiation therapy; GH, growth hormone; GKS, γ-knife surgery; IGF-I insulin-like growth factor 1.

Table 2.

Change of basal GH and IGF-I levels at baseline (week 0), week 12 and week 24

| Baseline | Week 12 | Week 24 | p Value* | p Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median GH (μg/L; range) | 4.8 (<1–184.6) | 1.9 (<1–14.1) | 2.3 (<1–16.2) | <0.001* | <0.001 |

| Median IGF-I (μg/L; range) | 497 (111–1231) | 265 (25–1600) | 284 (66–821) | <0.001* | <0.001 |

Data are displayed as the median (range).

*p Value was calculated by statistical analyses using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

†p Value was calculated by post hoc analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test between baseline and week 12.

GH, growth hormone; IGF-I insulin-like growth factor 1.

The median total score of AcroQoL at baseline was 75.3% (33.6–95.5, table 3). Although AcroQoL scores of most other domains showed no significant changes after 24 weeks of treatment with octreotide LAR, the psychological appearance subdomain of AcroQoL scores demonstrated a significant ordered difference between baseline and 24 weeks (from 68.6% to 75.4%, p=0.029, table 3).

Table 3.

Overall quality-of-life scores (%) at baseline (week 0), week 12 and week 24

| Overall AcroQoL scores (%) | Baseline | Week 12 | Week 24 | Difference between baseline and week 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 75.3 (33.6–95.5) | 76.9 (32.7–95.5) | 77.9 (32.7–99.1) | 3.8 (−30.9–21.8) |

| 1. Physical | 68.8 (30.0–97.5) | 71.9 (32.5–97.5) | 72.9 (35.0–100.0) | 2.3 (−22.5–22.5) |

| 2. Psychological | 76.4 (27.1–95.7) | 79.0 (27.1–97.1) | 79.4 (27.1–98.6) | 3.4 (−35.7–22.9) |

| Appearance* | 68.6 (22.9–91.4) | 73.5 (22.9–94.3) | 75.4 (22.9–97.1) | 6.0 (−25.7–34.3) |

| Personal relations | 83.9 (31.4–100.0) | 82.6 (31.4–100.0) | 85.0 (31.4–100.0) | −0.4 (−45.7–22.9) |

Data are displayed as the median (range).

*Analyses with the Jonckheere-Terpstra test demonstrated that the AcroQoL psychological appearance scores were significantly increased at week 24 when compared with those at baseline (p=0.029).

AcroQoL. acromegaly quality of life questionnaire.

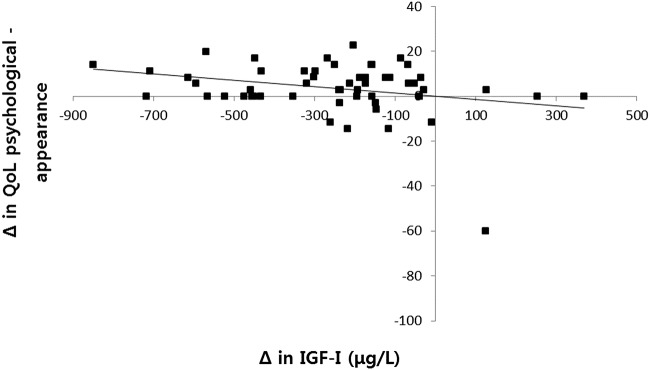

Correlation analyses indicated that significant negative correlations were observed between change in IGF-I and change in QoL when measured by total AcroQoL (r=−0.325, p=0.016), and the physical (r=−0.410, p=0.002) and psychological appearance (r=−0.282, p=0.039, figure 1) subdomains of AcroQoL during the first 12 weeks. However, the changes in IGF-I and the AcroQoL scores during the second 12 weeks (week 12 vs 24) were not statistically significant (data not shown).

Figure 1.

AcroQoL scores on psychological appearance demonstrated a negative correlation with change in IGF-I levels (r=−0.282, p=0.039; AcroQoL. acromegaly quality of life questionnaire; IGF-I insulin-like growth factor 1).

In the comparison between patients with controlled or uncontrolled disease activity based on their GH and IGF-I levels during the entire 24 weeks, the changes in both the GH and IGF-I levels were significantly different (p=0.025 for GH and p=0.029 for IGF-I, table 4). The changes of AcroQoL scores for the psychological appearance subdomain during the entire study period were significantly different between the controlled and uncontrolled groups (p=0.047, table 4). Similarly, the additional analysis according to the previous treatment with radiotherapy also revealed that only the changes of the psychological appearance subdomain during the entire 24 weeks were significantly different between those with (n=12) and without radiotherapy (n=46; 62.3→70.8→73.6% for the radiotherapy group; 67.3→71.2→72.4% for the non-radiotherapy group, p=0.040, data not shown).

Table 4.

Change of AcroQoL scores in patients with controlled and uncontrolled acromegaly

| Controlled (n=22) |

Uncontrolled (n=36) |

p Value* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Week 12 | Week 24 | Baseline | Week 12 | Week 24 | ||

| Biochemical markers (μg/L) | |||||||

| GH | 2.6 (0.8–10.8) | 0.4 (0.1–6.2) | 0.6 (0.1–0.9) | 7.5 (0.4–184.6) | 3.1 (0.1–14.1) | 3.8 (1.2–16.2) | 0.025 |

| IGF-I | 424 (263–967) | 209 (64–317) | 190 (66–320) | 494 (111–1214) | 360 (25–1161) | 334 (68–821) | 0.029 |

| AcroQoL scores (%) | |||||||

| Total | 77.3 (25.5–95.5) | 77.3 (39.1–94.6) | 80.5 (32.7–99.1) | 74.6 (33.6–93.6) | 74.1 (32.7–99.5) | 77.3 (32.7–95.5) | 0.552 |

| 1. Physical | 70.0 (30.0–95.0) | 72.5 (32.5–97.5) | 78.6 (35.0–100.0) | 67.5 (30.0–97.5) | 71.3 (40.0–97.5) | 71.3 (42.5–97.5) | 0.173 |

| 2. Psychological | 81.4 (38.6–95.7) | 81.4 (42.8–94.3) | 78.6 (31.4–98.6) | 74.3 (27.1–91.4) | 78.6 (27.1–97.1) | 78.6 (27.1–97.1) | 0.101 |

| Appearance | 74.3 (31.4–91.4) | 74.3 (37.1–94.3) | 74.3 (28.6–97.1) | 65.7 (22.9–88.6) | 72.3 (22.9–94.3) | 77.1 (22.9–97.1) | 0.047 |

| Personal relations | 88.6 (45.7–100.0) | 87.1 (48.6–100.0) | 90.0 (34.3–100.0) | 82.9 (31.4–100.0) | 80.0 (31.4–100.0) | 85.7 (31.4–100.0) | 0.357 |

Data are displayed as the median (range).

*p Value was calculated by statistical analyses using LMM.

AcroQoL. acromegaly quality of life questionnaire; GH, growth hormone; IGF-I insulin-like growth factor 1; LMM, linear mixed modelling.

Discussion

This study was the first prospective study which applied the Korean version of AcroQoL to evaluate the HRQoL of Korean patients with acromegaly after medical treatment with octreotide LAR. AcroQoL scores were not significantly improved by treatment with octreotide LAR, but the psychological appearance subdomain of AcroQoL demonstrated a tendency to improve after 24 weeks. There was a significant negative correlation between change in IGF-I and change in AcroQoL scores. Although there was no significant difference in AcroQoL scores between those with controlled and uncontrolled disease activity, it was found that AcroQoL scores for the psychological appearance subdomain in the two groups changed differently over the entire 24 weeks.

The HRQoL of patients with acromegaly is impaired by various accompanying morbidities such as depression,14 lethargy,15 decreased libido and sexual dysfunction as well as social withdrawal.16 In addition, morphological change, which remains the same or is aggravated even after successful treatment, is another feature of acromegaly which has considerable impact on HRQoL. Rapid regression of soft tissue swelling even after surgical tumour resection may contribute to more prominent morphological distortion, especially in the face, possibly leading to a worsening of the psychological aspects of HRQoL. In order to assess the HRQoL of patients with acromegaly, the AcroQoL questionnaire was first developed by Webb et al,8 and its validation against well-authenticated measures of QoL has demonstrated good internal consistency and construct validity.9 10 A number of studies have validated this questionnaire and, in agreement with our study, also revealed that the HRQoL of patients with acromegaly was impaired.7 9 11 12

However, previous studies investigating whether changes in the AcroQoL score differed significantly according to disease control have revealed inconsistent results. This study found no significant difference in AcroQoL scores between the controlled and uncontrolled groups, and only a change in the psychological appearance subdomain of the AcroQoL score over 24 weeks was found to be different between the two groups with marginal statistical significance (p=0.047, table 4). However, Matta et al11 demonstrated that the psychological appearance subdomain of AcroQoL scores was significantly different between the controlled and uncontrolled groups. It was previously reported that although the AcroQoL questionnaire was generally unable to discriminate between normal patients and patients with acromegaly, it was effective when subdomain analyses were performed and the most affected items were in the psychological appearance subdomain.7 It was also interesting to notice that the pattern of increase in the psychological appearance subdomain of the AcroQoL score in the uncontrolled group was more obvious than that of the controlled group (65.7→72.3→74.3% for the uncontrolled group; 74.3→74.3→77.1% for the controlled group, table 4). Our findings may be due to the higher baseline GH levels in the uncontrolled group than the controlled group (7.5 (0.4–184.6) μg/L for the uncontrolled group vs 2.6 (0.8–10.8) μg/L for the controlled group, table 4), and thus the amount of GH reduction in the uncontrolled group after 24 weeks of treatment was larger than that in the controlled group, leading to a more noticeable change of GH and consequent improvement of the AcroQoL score related to appearance after treatment.

This finding is in accord with the results of correlation analyses between the change of IGF-I and that of AcroQoL: there was a significant negative correlation between the change in IGF-I and change in the total, physical and psychological appearance subdomains of the AcroQoL. Paisley et al10 reported similar results that a change in GH and IGF-I was significantly correlated with a psychological subscale appearance score, and Rowles et al9 also reported significant negative correlations between change in IGF-I and total and other subdomains of AcroQoL, including appearance. However, the correlation analyses between change in AcroQoL scores and that of biochemical markers such as GH and IGF-I have not always exhibited consistent results. It has been suggested that the lack of correlation between the change in the AcroQoL score and that of biochemical markers could be due to other as yet unidentified factors.16 It should be also addressed that, in our study, a significant correlation was found only during the first 12 weeks of treatment with octreotide LAR and not during the entire 24 weeks. Previous studies have reported that the use of octreotide LAR was shown to improve biochemical markers only during the first 12 weeks.17 Thus, amelioration of GH hypersecretion at an early stage of treatment is believed to contribute to the improvement of HRQoL. It is well known that the longer the duration of the disease, the more difficult it is to achieve control of biochemical parameters, as well as to reverse morphological change,18 19 which emphasises the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly to achieve disease activity and to improve HRQoL.

The effect of medical treatment on AcroQoL scores has also given rise to controversy. In this study, only the psychological appearance subdomain of AcroQoL appeared to improve after treatment with octreotide LAR (table 3). Sonino et al20 previously reported that the HRQoL of patients with acromegaly was improved through the use of lanreotide. In contrast, a Taiwanese study by Hua et al21 reported that those with controlled disease activity by use of lanreotide exhibited impaired HRQoL after treatment compared with those with uncontrolled disease activity. It is noteworthy that both studies were based on patients treated with lanreotide, and not octreotide LAR,20 21 and that the Taiwanese study assessed HRQoL using tools (symptom questionnaire, cognitive scale of the screening list for psychological problems and social situation questionnaire) other than the AcroQoL21; thus, these results may not be directly comparable to our data. Recently, Webb et al used the AcroQoL to demonstrate improvement in HRQoL after treatment with octreotide LAR over 4 years.12 However, this study had some limitations as a retrospective observational study with only six patients who completed the entire 4-year follow-up period. Thus, it remains unclear whether medical treatment with octreotide LAR in acromegaly is able to improve the HRQoL of patients.

Unlike previous reports that radiotherapy in patients with acromegaly was associated with a reduction in AcroQoL scores,22–24 this study showed that those in the radiotherapy group experienced a greater increase in AcroQoL scores for the psychological appearance subdomain than the non-radiotherapy group. The study by van der Klaauw et al22 investigated the change of HRQoL in patients with acromegaly with stable controlled disease activity, while the HRQoL of patients in this study were evaluated as their treatment was ongoing, which makes the two studies less comparable. However, it should also be noted that radiotherapy may require more than 15 years to observe its treatment effect.25 In addition, hypopituitarism and especially GH deficiency after treatment of acromegaly have been reported as possible causes of HRQoL deterioration.26 27 There were four patients whose IGF-I levels at the end of the study period were below the normal range; however, none of them experienced symptoms or signs of GH deficiency. Accordingly, there is a limitation to conclude the effect of radiotherapy and hypopituitarism to HRQoL in Korean patients with acromegaly in this study, and a further study is necessary to observe their effects on the long-term change of HRQoL.

In conclusion, after using octreotide LAR, the AcroQoL scores of Korean patients with acromegaly did not show significant improvement, but their appearance subdomain scores demonstrated a trend towards improvement after 24 weeks of treatment. There was a significant negative correlation between change in IGF-I and change in AcroQoL scores. Although there was no significant difference in AcroQoL scores between patients with controlled and uncontrolled disease activity, change in the psychological appearance AcroQoL subdomain scores over the entire 24 weeks was significantly different between the two groups. It is speculated that appearance is one of the aspects which determines the HRQoL of patients with acromegaly, and medical treatment with octreotide LAR in patients with acromegaly has a limited contribution to HRQoL as assessed by the AcroQoL. Radiotherapy and the possible presence of hypopituitarism would have also resulted in the limited contribution of medical treatment to HRQoL in patients with acromegaly.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms Sung-Yoon Lee and Ms Ji Hyun Hong (research nurses at the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism in Kyung Hee University Hospital) for their diligence in managing the completion and collection of questionnaires and data. English editing assistance was provided by eWorldEditing Inc, Eugene, Oregon, USA.

Footnotes

Contributors: B-JK and S-WK contributed to the conception and design, critical revision of the manuscript, analysis and interpretation of the data and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript. CHC, Y-SC, HYK, I-JK, JGK, M-SK, S-YK, EJL and KYL contributed to the acquisition of the data. SOC wrote the paper. B-JK and S-WK contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by Novartis Korea.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Kyung Hee University Hospital (IRB No. KMC IRB 0903–03).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Melmed S. Medical progress: acromegaly. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2558–73. 10.1056/NEJMra062453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melmed S, Colao A, Barkan A et al. . Guidelines for acromegaly management: an update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:1509–17. 10.1210/jc.2008-2421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Klibanski A et al. . A consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly complications. Pituitary 2013;16:294–302. 10.1007/s11102-012-0420-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orme SM, McNally RJ, Cartwright RA et al. . Mortality and cancer incidence in acromegaly: a retrospective cohort study. United Kingdom Acromegaly Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:2730–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holdaway IM, Bolland MJ, Gamble GD. A meta-analysis of the effect of lowering serum levels of GH and IGF-I on mortality in acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol 2008;159:89–95. 10.1530/EJE-08-0267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katznelson L, Laws ER Jr, Melmed S et al. . Acromegaly: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:3933–51. 10.1210/jc.2014-2700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webb SM, Badia X, Surinach NL. Validity and clinical applicability of the acromegaly quality of life questionnaire, AcroQoL: a 6-month prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol 2006;155:269–77. 10.1530/eje.1.02214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webb SM, Prieto L, Badia X et al. . Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire (ACROQOL) a new health-related quality of life questionnaire for patients with acromegaly: development and psychometric properties. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002; 57:251–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowles SV, Prieto L, Badia X et al. . Quality of life (QOL) in patients with acromegaly is severely impaired: use of a novel measure of QOL: acromegaly quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:3337–41. 10.1210/jc.2004-1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paisley AN, Rowles SV, Roberts ME et al. . Treatment of acromegaly improves quality of life, measured by AcroQol. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;67:358–62. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02891.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matta MP, Couture E, Cazals L et al. . Impaired quality of life of patients with acromegaly: control of GH/IGF-I excess improves psychological subscale appearance. Eur J Endocrinol 2008;158:305–10. 10.1530/EJE-07-0697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mangupli R, Camperos P, Webb SM. Biochemical and quality of life responses to octreotide-LAR in acromegaly. Pituitary 2014;17:495–9. 10.1007/s11102-013-0533-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herdman M, Fox-Rushby J, Badia X. A model of equivalence in the cultural adaptation of HRQoL instruments: the universalist approach. Qual Life Res 1998;7:323–35. 10.1023/A:1008846618880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margo A. Acromegaly and depression. Br J Psychiatry 1981;139:467–8. 10.1192/bjp.139.5.467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flitsch J, Spitzner S, Ludecke DK. Emotional disorders in patients with different types of pituitary adenomas and factors affecting the diagnostic process. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2000;108:480–5. 10.1055/s-2000-8144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezzat S. Living with acromegaly. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1992;21:753–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercado M, Borges F, Bouterfa H et al. . A prospective, multicentre study to investigate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of octreotide LAR (long-acting repeatable octreotide) in the primary therapy of patients with acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:859–68. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02825.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajasoorya C, Holdaway IM, Wrightson P et al. . Determinants of clinical outcome and survival in acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1994;41:95–102. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb03789.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong JW, Ku CR, Kim SH et al. . Characteristics of acromegaly in Korea with a literature review. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2013;28:164–8. 10.3803/EnM.2013.28.3.164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonino N, Scarpa E, Paoletta A et al. . Slow-release lanreotide treatment in acromegaly: effects on quality of life. Psychother Psychosom 1999;68:165–7. 10.1159/000012326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hua SC, Yan YH, Chang TC. Associations of remission status and lanreotide treatment with quality of life in patients with treated acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol 2006;155:831–7. 10.1530/eje.1.02292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Klaauw AA, Biermasz NR, Hoftijzer HC et al. . Previous radiotherapy negatively influences quality of life during 4years of follow-up in patients cured from acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69:123–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03169.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biermasz NR, van Thiel SW, Pereira AM et al. . Decreased quality of life in patients with acromegaly despite long-term cure of growth hormone excess. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:5369–76. 10.1210/jc.2004-0669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kauppinen-Makelin R, Sane T, Sintonen H et al. . Quality of life in treated patients with acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:3891–6. 10.1210/jc.2006-0676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkins PJ, Bates P, Carson MN et al. . Conventional pituitary irradiation is effective in lowering serum growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I in patients with acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:1239–45. 10.1210/jc.2005-1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishii H, Shimatsu A, Okimura Y et al. . Development and validation of a new questionnaire assessing quality of life in adults with hypopituitarism: adult hypopituitarism Questionnaire (AHQ). PLoS ONE 2012;7:e44304 10.1371/journal.pone.0044304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazziotti G, Marzullo P, Doga M et al. . Growth hormone deficiency in treated acromegaly. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015;26:11–21. 10.1016/j.tem.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]