Abstract

Objective

To examine arthritis impact among U.S. adults with self-reported, doctor-diagnosed arthritis using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) framework (domains=Impairments, Activity Limitations, Environmental, and Personal factors; outcome=social participation restriction (SPR)) 1) overall and among those with SPR, and 2) to identify correlates of SPR.

Methods

Cross-sectional 2009 National Health Interview Survey data were analyzed to examine the distribution of ICF domain components. Unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated to identify correlates of SPR. Analyses in SAS v9.2 survey procedures accounted for the complex sample design.

Results

SPR prevalence was 11% (5.7 million) of adults with arthritis. After initial multivariable adjustment by ICF domain, Serious Psychological Distress (Impairments) (PR=2.5, 95% CI=2.0-3.2, ≥5 medical office visits (Environmental) (PR=3.4, 95% CI=2.5-4.4) , and physical inactivity (Personal) (PR=4.8, 95% CI=3.6=6.4) were most strongly associated with SPR. A combined measure, Key Limitations (walking, standing, or carrying) (PR=31.2 (22.3-43.5) represented the Activity Limitations domain. After final multivariable adjustment incorporating all ICF domains simultaneously, the strongest associations with SPR were Key Limitations (PR= 24.3 (16.8-35.1), ≥9 hours sleep (PR=1.6, 95% CI=1.3-2.0), and income-to-poverty ratio <2.00 and severe joint pain (PR=1.4, 95% CI=1.2-1.6 for both).

Conclusion

SPR affects 1-in-9 adults with arthritis. This work is the first to use the ICF framework in a population-based sample to identify specific functional activities, pain, sleep, and other areas for priority intervention to reduce negative arthritis impacts, including SPR. Increased use of existing clinical and public health interventions is warranted.

Arthritis is common, affecting 50 million adults in the United States (1), costly, at an annual total exceeding $128 billion (USD) (2), and has been the most common cause of disability among U.S. adults for more than fifteen years (3). Despite this staggering impact, the complex process through which arthritis leads to disability is not fully understood (4). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) is a system developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to “provide a unified and standard language and framework for the description of health and health-related states” (5). This approach considers the anatomical/physiological (impairment), individual (activity limitation), and societal (participation restriction) consequences of health conditions in the context of personal and environmental factors and reflects a continuum between positive (functional and structural integrity) and negative functioning (impairments, activity limitations, and participation restriction), with negative aspects indicating disability. At the societal level, participation is “involvement in a life situation,” while participation restriction (PR) is “problems an individual may experience in involvement in life situations” and reflects difficulties in activities such as getting out and about, visiting friends, and leisure activities (5). WHO has proposed that the ICF be used to investigate consequences of health conditions; the comprehensive scope makes it ideal for studying arthritis (5, 6).

Although the ICF has been mapped to different clinical outcome measures for arthritis (7-9), and ICF core sets have been developed for osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and other chronic musculoskeletal conditions (10), no population-based studies have applied an inclusive view of all ICF domains to assess PR in adults with arthritis (11). While population-based and clinical studies have often focused on disease impacts considered activity limitations or impairments in the ICF, examining PR using all of the ICF domains, including the contextual personal and environmental factors, provides an opportunity to explore a more comprehensive approach to assessing and describing one aspect of disability among adults with arthritis.

Recently there has been a growing interest in PR (12-17)—in part due to the recognition that the social consequences of musculoskeletal conditions (e.g., difficulty shopping or visiting relatives) may be of greater concern to individuals than impairments (e.g., pain) or specific activity limitations (e.g., walking more than half a mile). Participation is an important outcome for examining the effectiveness of clinical (e.g., joint replacements) and public health (e.g., psychoeducational courses) interventions even when it may not be the target; the secondary benefits of these interventions may be improvements in the ability to go on errands, look after friends and family, work, and be a part of the community. Importantly, even in the presence of ongoing signs (radiographic change), symptoms (pain), and activity limitation (walking limitation), participation can be maintained (14).

Despite increased attention to participation, to our knowledge, there are no ICF-based studies of PR among the U.S. adult population with arthritis (11). Furthermore, in most existing studies, the conceptualization of participation has been limited (e.g., measurement specification (17), hypothesis testing (16), psychosocial aspects of role value and performance (15)). The purpose of this study is to examine arthritis impact among U.S. adults with self-reported, doctor-diagnosed arthritis using the entire ICF framework 1) overall and among those with and without SPR, and 2) to identify correlates of SPR.

Materials and Methods

Study sample

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is an annual health survey of people of all ages. It uses a complex sample design to select a sample representing the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population (18). Data are collected through in-home interview by trained interviewers. We studied adults (≥18 years) who, in 2009 (the most recent year with all relevant variables), had records in the sample adult core, family, household, and person files (n=27,731); conditional and final response rates in the sample adult core were 80.1% and 65.4%, respectively (18).

Definitions

Doctor-diagnosed arthritis

The sample was limited to people with self-reported, doctor-diagnosed arthritis (hereafter “arthritis”) (n=6,696), identified by “yes” to: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus or fibromyalgia?”

Social Participation Restriction

Respondents who answered “very difficult” or “can’t do at all” to either of the following were classified as having social participation restriction (SPR): “By yourself, and without using any special equipment, how difficult is it for you to…” 1) “Go out to things like shopping, movies, or sporting events?” and 2) “Participate in social activities such as visiting friends, attending clubs and meetings, going to parties?”

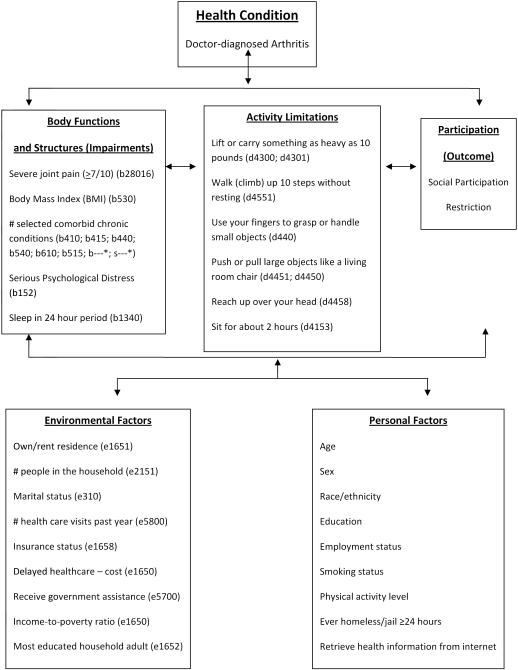

Prior to analysis, we reviewed the NHIS documentation to identify all variables that could be coded to ICF domains. We used three criteria to select variables for analysis: 1) conceptual relevance, 2) sufficient sample size (≥50 cases), and/or 3) meaningful prevalence in the population (≥5%). Several variables (e.g., housing density, excess alcohol consumption, US Census region) were initially considered but failed to meet these criteria. All variables analyzed are presented in Figure 1. Detailed ICF codes for each measure are provided in Appendix A, with the exception of variables representing personal factors (e.g., age, race/ethnicity) because, per WHO, personal factors are not assigned codes (5).

Figure 1.

International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) domains with codes and National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) variables used in analysis, adapted from the WHO ICF figure (5).

Appendix A.

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) measures used in analysis with detailed International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) codes and definitions, NHIS 2009

| NHIS measure used in analysis |

ICF Chapter Heading (sub-chapter) |

First branching level |

ICF code |

Remaining branching levels→ ICF definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Social

participation restriction |

Activities and Participation (9) |

Community, social, and civic life |

d910; d920 |

Community, social, and civic life→ Community Life; Recreation and Leisure |

| Impairments | ||||

|

Severe joint pain

(≥7/10) |

Body Functions (2) |

Sensory functions and pain |

b28016 | Pain→ Sensation of pain→ Pain in joints |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Body Functions (5) |

Functions of the digestive, metabolic and endocrine systems |

b530 | Functions related to the digestive system→ Weight maintenance functions |

| Number of selected comorbid conditions (max 10) | ||||

| Hypertension | Body Functions (4) |

Functions of the cardiovascular, haematological, immuniological, and respiratory systems |

b 415 | Functions of the cardiovascular system→ Blood vessel functions |

| Heart disease (coronary heart disease, angina, myocardial infarction, other heart disease) |

Body Functions (4) |

Functions of the cardiovascular, haematological, immuniological, and respiratory systems |

b 410 | Functions of the cardiovascular system→ Heart functions |

| Stroke | Body Functions (4) |

Functions of the cardiovascular, haematological, immuniological, and respiratory systems |

b 415 | Functions of the cardiovascular system→ Blood vessel functions |

| Emphysema | Body Functions (4) | Functions of the respiratory system |

b 440 | Respiratory functions |

| Asthma | Body Functions (4) |

Functions of the respiratory system |

b 440 | Respiratory functions |

| Cancer | All Body Functions and Body Structures |

b---; s--- | Because cancer can affect virtually any body structure and influence function and because we queried regarding any type of cancer, this item cannot be further classified |

|

| Diabetes | Body Functions (5) |

Functions of the digestive, metabolic, and endocrine systems |

b 540 | Functions related to metabolism and the endocrine system→ General metabolic function |

| Chronic bronchitis |

Body Functions (4) |

Functions of the respiratory system |

b 440 | Respiratory functions |

| Weak/failing kidneys |

Body Functions (6) |

Genitourinary and reproductive functions |

b 610; b6100 |

Urinary excretory functions→ Filtration of urine by the kidneys |

| Liver disease | Body Functions (5) |

Functions of the digestive, metabolic, and endocrine systems |

b 515 | Functions related to the digestive system→ Digestive functions |

|

Serious

Psychological Distress |

Body Functions (1) |

Mental functions | b 152 | Specific mental functions→ Emotional functions |

|

Sleep in 24 hour

period |

Body Functions (1) |

Mental functions | b1340 | Global mental functions→ Sleep functions→ Amount of sleep |

|

Limitations

(defined as “very difficult” or “cannot do”) | ||||

| Carry/lift something as heavy as 10 pounds |

Activities and Participation (4) |

Mobility | d4300; d4301; d4302 |

Carrying, moving and handling objects→ Lifting and carrying objects→ Lifting; Carrying in the hands; Carrying in the arms |

| Climb up 10 steps without resting |

Activities and Participation (4) |

Mobility | d4551 | Carrying, moving, and handling objects→ Walking and moving → Moving around→ Climbing (e.g., climbing steps or stairs) |

| Grasp/handle small objects with your fingers |

Activities and Participation (4) |

Mobility | d440; d4401; d4402 |

Carrying, moving, and handling objects→ Fine hand use→ Grasping; Manipulating |

| Push/pull large objects (living room chair) |

Activities and Participation (4) |

Mobility | d4451; d4450 |

Carrying, moving, and handling objects→ Hand and arm use→ Pushing; Pulling |

| Reach up over your head |

Activities and Participation (4) |

Mobility | d4458 | Carrying, moving, and handling objects→ Hand and arm use→ Hand and arm use, other specified |

| Sit for about 2 hours |

Activities and Participation (4) |

Mobility | d4153 | Changing and maintaining body position→ Maintaining a body position→ Maintaining a sitting position |

| Stand or be on your feet for about 2 hours |

Activities and Participation (4) |

Mobility | d4154 | Changing and maintaining body position→ Maintaining a body position→ Maintaining a standing position |

| Stoop, bend, or kneel |

Activities and Participation (4) |

Mobility | d4106; d4105; d4102 |

Changing and maintaining body position→ Changing basic body position→ Shifting the body’s centre of gravity; Bending; Kneeling |

| Walk ¼ mile or 3 city blocks |

Activities and Participation (4) |

Mobility | d4500 | Walking and moving→ Walking→ Walking short distances |

| Environmental Factors | ||||

| Homeownership | Environmental (1) |

Products and technology |

e1651 | Assets→ Tangible assets (e.g., houses and land) |

|

Household size (#

people in household) |

Environmental (2) |

Natural environment and human-made changes to environment |

e2151 | Population→ Population density |

| Marital status | Environmental (3) |

Support and relationships |

e310 | Immediate family (e.g., related by marriage; spouse) |

|

Medical office

visits in the past year |

Environmental (5) |

Services, systems, and policies |

e5800 | Health services, systems, and policies→ Health services (e.g., primary care services, acute care, rehabilitation, and long- term care services) |

| Health insurance | Environmental (1) |

Products and technology |

e1658 | Assets→ Assets, other specified |

|

Delayed

healthcare due to cost (yes) |

Environmental (1) |

Products and technology |

e1650 | Assets→ Financial assets |

|

Received

government assistance last calendar year (yes) |

Environmental (5) |

Services, systems, and policies |

e5700 | Social security services, systems, and policies→ Social security services (e.g., public assistance) |

|

Income-to-poverty

ratio |

Environmental (1) |

Products and technology |

e1650 | Assets→ Financial assets |

|

Most educated

household adult |

Environmental (1) |

Products and technology |

e1652 | Assets→ Intangible assets (e.g., knowledge and skills) |

|

Personal factors-not classified due to substantial social and cultural variance associated with them; “Contextual factors that relate to the individual such as age, gender, social status, life experiences and so on, which are not currently classified in ICF but which users may incorporate in their applications of the classification (5).” | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Education | ||||

| Employment status | ||||

| Current smoker | ||||

| Physical activity level-aerobic | ||||

| >2 hours homeless or in jail | ||||

| Retrieve health information from internet | ||||

Impairments

Respondents rated their joint pain in the past 30 days on a scale of 0 (none) to 10 (“as bad as it can be”); ratings ≥7 were classified as severe joint pain (19, 20). Body Mass Index (BMI) (weight in kg/height in m²) was calculated from self-reported weight and height. Respondents were asked whether they had ever been diagnosed with a series of chronic conditions. We examined: hypertension, heart disease (coronary heart disease, angina, myocardial infarction, other heart disease), stroke, emphysema, asthma, cancer, diabetes, chronic bronchitis, weak/failing kidneys, and liver disease. Responses (yes = 1, no = 0) were summed (range 0-10) and categorized to represent the number of selected comorbid conditions (0; 1-2; ≥3). Serious psychological distress was measured with the Kessler 6 (K6), a scale developed to identify and monitor population-level prevalence and trends of non-specific serious psychological distress (21). The K6, consisting of 6 questions rated on a 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time) scale asks how often in the past 30 days the respondent felt each of: sad; worthless; nervous; restless; hopeless; that everything was an effort. Values were summed for a total score (0-24); scores ≥13 identified respondents with serious psychological distress (21). In an article examining the relationship of sleep to several health outcomes, Knutson commented on the u-shaped curve observed in self-reported and clinically measured sleep and noted that, across studies, “short sleep” is generally <6 hours per night while “long sleep” is generally >8 hours (22). Therefore, we categorized average number of sleep hours in a 24-hour period in this study: 1-5; 6-8; ≥9 hours.

Activity Limitation

Respondents reported their ability, using a 5 point scale (not at all difficult; only a little difficult; somewhat difficult; very difficult; can’t do at all; do not do this activity) to do the following nine specific activities critical to independent functioning: “By yourself, and without using any special equipment, how difficult is it for you to…. 1) Lift or carry something as heavy as 10 pounds such as a full bag of groceries, 2) Walk (climb) up 10 steps without resting, 3) Use your fingers to grasp or handle small objects, 4) Push or pull large objects like a living room chair, 5) Reach up over your head, 6) Sit for about 2 hours, 7) Stand or be on your feet for about 2 hours, 8) Stoop, bend or kneel, 9) Walk ¼ mile or 3 city blocks. Each limitation was coded as a 2-level variable with those indicating “very difficult” or “can’t do at all” classified as “yes” and all others as not limited. Very few respondents (range n=14 (0.2%) (grasp) to n=432 (6.5%) (push)) reported “do not do this activity;” because it is not possible to determine whether these individuals choose not to perform these activities or are unable to do them, the most conservative approach was including them in the “not limited” group. For programmatic and surveillance purposes, two summary limitation variables were created reflecting ≥1 limitation (versus none) and ≥3 limitations (versus 0-2).

Anticipating high multicollinearity among the above activity limitations, we created a combination variable for the regression analyses. The two authors with clinical backgrounds (RW [physiotherapy]; JMH [sports medicine/athletic training]) nominated each of lower extremity, upper extremity, mobility, and endurance as the most important capacities to include in a combined variable. These capacities were represented by three variables: walk (lower limb mobility); carry (upper limb mobility and strength) and stand (overall endurance). The presence of key limitations was defined as a response of “very difficult” or “can’t do at all” for any of the three.

Contextual Factors per ICF

The ICF distinguishes contextual factors as environmental (i.e., external) or personal (i.e., internal) factors.1 Environmental categories include one’s immediate inter-personal and physical environment, use of services, and support and relationships. Personal factors include individual characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education, social background, past experience, coping style) (5).

Environmental Factors

Respondents were queried regarding homeownership, household size (number of people in household), and marital status. Participants were also asked a series of questions about their number of medical office visits in the past year, if they had health insurance, or had delayed health care due to cost in the past year. Receipt of government assistance was assessed by a “yes” response to receiving ≥1 type of government assistance in the previous calendar year (i.e., welfare; food stamps; other assistance). NHIS provides a calculated variable of family income divided by the relevant poverty threshold (poverty thresholds account for family size and are therefore more informative than income alone) (18, 23). Depth of poverty can be assessed by the income-to-poverty ratio. Although the U.S. Census Bureau does not use this term, ratios of >1.00 ≤ 1.99 are often cited as “near poverty” (23). For this study, the income-to-poverty ratio was categorized as: <2.00; ≥2.00. Finally, the most educated household adult was classified as: less than high school; GED/high school graduate; some college, no college degree; college degree or more.

Personal Factors

Personal factors identified from the NHIS were 1) sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, respondent’s education (defined as above), employment), 2) health behaviors ((aerobic-physical activity level per 2008 criteria (meets physical activity guidelines recommendations; insufficient; inactive) (24), current smoker, retrieve health information from the internet)), and 3) whether the respondent had ever spent ≥24 hours homeless or in jail. The last three variables were coded as 1= yes; all others = no.

Missing values for the non-dichotomous variables ranged from n=1 (employment) to n=250 (BMI), (0.0% to 3.7% of the sample, respectively), with the exception of the income-to-poverty ratio which had n=712 missing, (10.6% of the sample).

Data Analysis

To address our first aim of describing the profile of people with arthritis using the ICF framework, we calculated distributions of all study variables across U.S. adults with arthritis overall and among those with arthritis with and without SPR. Analyses were conducted using SAS v9.2 survey procedures (25); sampling weights were applied to derive nationally representative estimates and the standard error calculations accounted for the complex sample design. All reported estimates have a relative standard error <20%.

To address our second aim of examining associations with SPR and identifying correlates, regression modeling proceeded in four steps.

First, independent associations between each variable and SPR were estimated with unadjusted prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Second, we used the following criteria to identify eligible variables for the multivariable-adjusted models by examining: 1) potential modifiability (possibly amenable to intervention); 2) known relationship with SPR from other studies; 3) statistical significance in the univariable regression stage; and 4) a moderate to strong association (defined as a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of ≥0.4). For example, if the Spearman’s correlation coefficient between two variables was ≥0.4, the variable that was not modifiable or had no known relationship to SPR was excluded. Statistical significance in univariable regression was defined as having CIs which did not include 1.0; statistically significant differences in PRs was defined as non-overlapping 95% CIs. This is a more conservative approach than significance testing and more appropriate for our study given the large sample size, number of variables, and multiple comparisons (26).

Third, once the candidate variables for each ICF domain were identified, the entire group of variables in each domain was analyzed simultaneously. We ran a series of multivariable models for each domain and tested for potential collinearity using the Condition Index (SAS proc reg). For each model, we identified the variable with the largest individual condition index ≥30.0 (27). Then, the model was re-run excluding this variable with the final model including variables with a condition index of <30 only.

Fourth, once the multivariable model for each ICF domain was finalized, a multivariable “meta” model incorporating all ICF domains was created using the same process described in step three. This multivariable meta-model was created to identify the strongest statistically significant independent associations with SPR when variables across all ICF domains were examined simultaneously.

Results

Study Population (Table 1)

Table 1.

Distribution of International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) characteristics, by domain, among U.S. adults ≥18 years with self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis overall and with and without social participation restriction (SPR) (weighted number, percent and 95% confidence intervals (CI)), National Health Interview Survey, 2009.

| All adults with arthritis N= 52,106,717 |

Adults with arthritis but not SPR N=46,382,370 |

Adults with arthritis and SPR N=5,724,347 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N in 1,000s |

% (95% CI) |

N in 1,000s |

% (95% CI) |

N in 1,000s |

% (95% CI) |

|

|

Social participation

restriction |

5,724 | 11.0 (10.0-12.0) | 0 | 0.0 | 5,724 | 100.0 |

| Impairments | ||||||

| Severe joint pain (≥7/10) | 14,116 | 27.1 (25.6-28.6) | 10,940 | 23.6 (22.1-25.1) | 3,176 | 55.5 (51.9-59.1) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | ||||||

| Under or normal weight (<25.0) |

13,715 | 27.4 (26.0-28.7) | 12,128 | 27.1 (25.7-28.5) | 1,588 | 29.4 (25.9-33.0) |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 17,247 | 34.4 (33.0-35.8) | 15,696 | 35.1 (33.5-36.6) | 1,551 | 28.8 (25.4-32.1) |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 19,183 | 38.3 (36.8-39.8) | 16,928 | 37.8 (36.2-39.4) | 2,255 | 41.8 (38.1-45.6) |

| Number of selected comorbid conditions | ||||||

| 0 | 12,412 | 23.8 (22.5-25.1) | 11,820 | 25.5 (24.1-26.9) | 592 | 10.3 (8.5-12.1) |

| 1-2 | 27,569 | 52.9 (51.4-54.4) | 24,891 | 53.7 (52.9-55.3) | 2,678 | 46.8 (43.1-50.5) |

| 3-10 | 12,126 | 23.3 (21.9-24.6) | 9,671 | 20.9 (19.4-22.3) | 2,454 | 42.9 (39.0-46.8) |

|

Serious Psychological

Distress |

8,501 | 16.3 (15.1-17.5) | 1,900 | 4.1 (3.4-4.8) | 1,292 | 22.6 (19.2-25.9) |

| Sleep in 24 hour period (hours) | ||||||

| 1-5 | 6,518 | 12.7 (11.7-13.7) | 5,343 | 11.6 (10.6-12.7) | 1,174 | 21.5 (18.2-24.7) |

| 6-8 | 38,787 | 75.4 (74.1-76.7) | 35,752 | 77.8 (76.4-79.2) | 3,035 | 55.4 (51.5-59.4) |

| ≥9 | 6,139 | 11.9 (10.9-13.0) | 4,874 | 10.6 (9.5-11.7) | 1,265 | 23.1 (20.2-26.0) |

|

Activity Limitations

(defined as “very difficult” or “cannot do”) | ||||||

| Carry/lift something as heavy as 10 pounds |

6,465 | 12.4 (11.5-13.4) | 2,999 | 6.5 (5.7-7.2) | 3,466 | 60.6 (57.0-64.1) |

| Climb up 10 steps without resting |

7,985 | 15.3 (14.3-16.3) | 4,298 | 9.3 (8.4-10.2) | 3,687 | 64.4 (61.1-67.7) |

| Grasp/handle small objects with your fingers |

2,848 | 5.5 (4.8-6.1) | 1,530 | 3.3 (2.8-3.8) | 1,317 | 23.0 (19.6-26.4) |

| Push/pull large objects (living room chair) |

9,489 | 18.2 (17.0-19.5) | 5,519 | 11.9 (10.8-13.0) | 3,970 | 69.4 (66.0-72.7) |

| Reach up over your head | 3,667 | 7.0 (6.3-7.8) | 1,928 | 4.2 (3.5-4.8) | 1,739 | 30.4 (27.0-33.8) |

| Sit for about 2 hours | 5,115 | 9.8 (8.9-10.8) | 3,228 | 7.0 (6.1-7.8) | 1,887 | 33.0 (29.6-36.3) |

| Stand or be on your feet for about 2 hours |

14,226 | 27.3 (25.8-28.8) | 9,416 | 20.3 (18.8-21.8) | 4,809 | 84.0 (81.5-86.5) |

| Stoop, bend, or kneel | 14,150 | 27.2 (25.7-28.6) | 9,755 | 21.0 (19.7-22.4) | 4,395 | 76.8 (73.6-79.9) |

| Walk ¼ mile or 3 city blocks | 10,933 | 21.0 (19.7-22.3) | 6,441 | 13.9 (12.7-15.1) | 4,492 | 78.5 (75.5-81.5) |

| Summary limitation variables | ||||||

| ≥1 limitation | 22,160 | 42.5 (40.9-44.1) | 16,614 | 35.8 (34.2-37.5) | 5,546 | 96.9 (95.4-98.3) |

| ≥3 limitations | 12,190 | 23.4 (22.0-24.8) | 7,297 | 15.7 (14.5-17.0) | 4,893 | 85.5 (82.8-88.2) |

| Key limitations

(walk/stand/carry) |

17,020 | 32.7 (31.1-34.2) | 11,650 | 25.1 (23.6-26.7) | 5,369 | 93.8 (92.1-95.5) |

| Environmental Factors | ||||||

| Homeownership | ||||||

| Own/being bought | 39,587 | 76.0 (74.6-77.5) | 35,934 | 77.5 (76.0-79.0) | 3,653 | 63.9 (60.8-67.1) |

| Rent/other | 12,485 | 24.0 (22.5-25.4) | 10,422 | 22.5 (21.0-24.0) | 2,063 | 36.1 (32.9-39.2) |

| Household size (# of people in household) | ||||||

| Single | 12,308 | 23.6 (22.5-24.8) | 10,541 | 22.7 (21.5-23.9) | 1,767 | 30.9 (28.0-33.7) |

| 2 | 22,732 | 43.6 (42.1-45.2) | 20,563 | 44.3 (42.7-46.0) | 2,169 | 37.9 (34.5-41.3) |

| ≥ 3 | 17,066 | 32.7 (31.1-34.4) | 15,278 | 32.9 (31.2-34.7) | 1,788 | 31.2 (27.6-34.9) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/living with partner | 32,837 | 63.1 (61.6-64.6) | 30,117 | 65.0 (63.5-66.5) | 2,720 | 47.5 (43.6-51.4) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 14,878 | 28.6 (27.2-29.9) | 12,429 | 26.8 (25.5-28.2) | 2,449 | 42.8 (39.3-46.3) |

| Never married | 4,336 | 8.3 (7.5-9.1) | 3,781 | 8.2 (7.3-9.0) | 555 | 9.7 (7.8-11.6) |

| Medical office visits in the past year | ||||||

| 0-1 visits | 7,459 | 14.5 (13.4-15.6) | 7,055 | 15.4 (14.2-16.6) | 404 | 7.2 (5.6-8.9) |

| 2-4 visits | 26,684 | 51.9 (50.4-53.5) | 24,592 | 53.7 (52.0-55.4) | 2,092 | 37.5 (34.6-40.5) |

| ≥ 5 visits | 17,252 | 33.6 (32.0-35.1) | 14,175 | 30.9 (29.3-32.6) | 3,077 | 55.2 (51.9-58.6) |

| Health insurance (no) | 4,498 | 8.6 (7.7-9.6) | 4,007 | 8.7 (7.7-9.7) | 490 | 8.6 (6.7-10.5) |

|

Delayed healthcare due to

cost in past year (yes) |

8,074 | 15.5 (14.5-16.5) | 6,815 | 14.7 (13.6-15.8) | 1,259 | 22.0 (19.0-25.0) |

|

Received government

assistance last calendar year (yes) |

4,531 | 8.7 (7.9-9.5) | 3,268 | 7.0 (6.2-7.9) | 1,263 | 22.1 (19.0-25.2) |

| Income-to-poverty ratio | ||||||

| < 2.00 (Below or near poverty) |

14,358 | 30.6 (29.1-32.2) | 11,476 | 27.5 (25.9-29.1) | 2,882 | 56.3 (52.9-59.7) |

| ≥ 2.00 | 32,504 | 69.3 (67.8-70.9) | 30,266 | 72.5 (70.9-74.1) | 2,238 | 43.7 (40.3-47.1) |

| Most educated household adult | ||||||

| Less than high school | 5,189 | 10.0 (9.1-10.8) | 4,030 | 8.7 (7.9-9.5) | 1,159 | 20.3 (17.4-23.2) |

| GED or high school graduate | 13,302 | 25.6 (24.2-27.0) | 11,574 | 25.0 (23.6-26.4) | 1,728 | 30.3 (27.2-33.4) |

| Some college, no degree | 10,893 | 20.9 (19.6-22.3) | 9,708 | 21.0 (19.6-22.4) | 1,186 | 20.8 (17.9-23.7) |

| College degree or more | 22,637 | 43.5 (41.9-45.1) | 20,999 | 45.3 (43.7-47.0) | 1,637 | 28.7 (25.6-31.8) |

| Personal factors | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18-44 | 8,963 | 17.2 (15.9-18.5) | 8,164 | 17.6 (16.2-19.0) | 799 | 14.0 (11.4-16.6) |

| 45-64 | 23,844 | 45.8 (44.0-47.5) | 21,559 | 46.5 (44.6-48.4) | 2,286 | 39.9 (36.3-43.5) |

| 65+ | 19,299 | 37.0 (35.3-38.7) | 16,660 | 35.9 (34.1-37.7) | 2,639 | 46.1 (43.0-49.2) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 20,775 | 39.9 (38.5-41.3) | 18,957 | 40.9 (39.4-42.4) | 1,818 | 31.8 (28.4-35.1) |

| Female | 31,332 | 60.1 (58.7-61.5) | 27,425 | 59.1 (57.6-60.6) | 3,907 | 68.2 (64.9-71.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 40,549 | 77.8 (76.4-79.2) | 36,513 | 78.7 (77.3-80.2) | 4,036 | 70.5 (67.5-73.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5,728 | 11.0 (9.9-12.0) | 4,865 | 10.5 (9.4-11.5) | 863 | 15.1 (12.8-17.3) |

| Hispanic | 3,793 | 7.3 (6.5-8.0) | 3,306 | 7.1 (6.3-8.0) | 487 | 8.5 (6.9-10.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 2,037 | 3.9 (3.3-4.5) | 1,698 | 3.7 (3.0-4.3) | 340 | 5.9 (4.1-7.7) |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 8,720 | 16.8 (15.7-18.0) | 6,775 | 14.7 (13.5-15.8) | 1,945 | 34.2 (31.2-37.3) |

| GED or high school graduate | 16,376 | 31.6 (30.1-33.0) | 14,594 | 31.6 (30.1-33.1) | 1,782 | 31.3 (28.3-34.4) |

| Some college, no degree | 10,530 | 20.3 (19.0-21.6) | 9,591 | 20.8 (19.4-22.2) | 938 | 16.5 (13.7-19.3) |

| College degree or more | 16,227 | 31.3 (29.7-32.9) | 15,206 | 32.9 (31.3-34.6) | 1,022 | 18.0 (15.1-20.8) |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Working | 27,802 | 53.4 (51.7-55.0) | 24,748 | 53.4 (51.6-55.2) | 3,054 | 53.4 (49.8-56.9) |

| Not working | 24,300 | 46.6 (45.0-48.3) | 21,631 | 46.6 (44.8-48.4) | 2,670 | 46.6 (43.1-50.2) |

| Current smoker (yes) | 10,868 | 20.9 (19.5-22.2) | 9,301 | 20.1 (18.6-21.5) | 1,567 | 27.4 (23.6-31.2) |

| Aerobic Physical activity level | ||||||

| Meets Recommended | 18,451 | 36.2 (34.5-38.0) | 17,855 | 39.4 (37.6-41.3) | 596 | 10.6 (8.5-12.7) |

| Insufficient | 11,261 | 22.1 (20.7-23.5) | 10,420 | 23.0 (21.5-24.5) | 841 | 15.0 (12.4-17.5) |

| Inactive | 21,195 | 41.6 (39.9-43.4) | 17,022 | 37.6 (35.8-39.4) | 4,174 | 74.4 (71.0-77.8) |

|

≥2 hours homeless or in jail

(yes) |

3,529 | 6.8 (5.9-7.6) | 2,845 | 6.1 (5.3-7.0) | 684 | 12.0 (9.1-14.8) |

|

Retrieve health information

from internet (yes) |

24,588 | 47.2 (45.6-48.8) | 23,153 | 49.9 (48.2-51.6) | 1,434 | 25.1 (21.9-28.2) |

NOTE: Numbers may not sum to 100.0 due to rounding

Detailed characteristics of the population (U.S. adults ≥18 years with arthritis) are presented in Table 1 and Appendix B.

The prevalence of SPR was 11% (5.7 million) of adults with arthritis. Compared with those without SPR, adults with SPR reported greater than five times the prevalence of serious psychological distress (22.6% vs. 4.1%) and three to ten times the prevalence of activity limitations. Nearly all (96.9%) respondents with SPR reported ≥1 limitation, and 85.5% reported ≥3 limitations, compared with 35.8% and 15.7%, respectively, for those without SPR. Those with SPR also reported double the prevalence of an income-to-poverty ratio <2.00 (56.3% vs. 27.5%). Most respondents with SPR were non-Hispanic whites (70.5%) and women (68.2%); 46.1% were ≥65 years. Respondents with SPR tended to have low education (34.2% less than a high school; 31.3% GED or high school graduate). Employment was the same across groups.

Prevalence ratios, unadjusted (Table 2)

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations (prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs)) of International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) characteristics, by domain, with Social Participation Restriction (SPR) among U.S. adults ≥18 years with self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis, National Health Interview Survey, 2009.

| Unadjusted associations with SPR PR (95% CI) |

Multivariate ICF domain- specific models PR (95% CI) |

Meta Multivariate model (includes all ICF domains)* PR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Impairments | |||

| Severe joint pain (≥7/10) (ref = no) | 3.4 (2.9-4.0) | 1.7 (1.4-2.0) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | |||

| Underweight/normal (<25.0) | 1.0 | - | - |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | - | - |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | - | - |

| Number of selected comorbid conditions | |||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | - |

| 1 to 2 | 2.0 (1.6-2.7) | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) | - |

| ≥3 | 4.2 (3.2-5.6) | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) | - |

| Serious Psychological Distress (ref = no) | 4.5 (3.7-5.4) | 2.5 (2.0-3.2) | - |

| Sleep in 24 hour period (hours) | |||

| 1-5 | 2.3 (1.9-2.9) | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) |

| 6-8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| ≥9 | 2.6 (2.1-3.2) | 1.5 (1.3-1.9) | 1.6 (1.3-2.0) |

| Limitations (defined as “very difficult” or “cannot do”) (ref = not limited) | |||

| Carry or lift something as heavy as 10 pounds | 10.8 (9.2-12.7) | - | - |

| Climb up 10 step without resting | 10.0 (8.5-11.8) | - | - |

| Grasp or handle small objects with your fingers | 5.2 (4.4-6.1) | - | - |

| Push or pull large objects (e.g., living room chair) | 10.2 (8.5-12.2) | - | - |

| Reach up over your head | 5.8 (4.9-6.8) | - | - |

| Sit for about 2 hours | 4.5 (3.9-5.3) | - | - |

| Stand for about 2 hours | 14.0 (11.1-17.7) | - | - |

| Stoop, bend, or kneel | 8.9 (7.3-10.8) | - | - |

| Walk 1/4 mile or 3 city blocks | 13.7 (11.1-17.0) | - | - |

| Summary limitation variables | |||

| ≥1 limitation (ref = no) | 41.9 (25.5-68.8) | - | - |

| ≥3 limitations (ref = no) | 19.3 (15.0-24.9) | - | - |

| Key limitation (walk/stand/carry) (ref = no) | 31.2 (22.3-43.5) | 31.2 (22.3-43.5) | 24.3 (16.8-35.1) |

| Environmental Factors | |||

| Homeownership | |||

| Own/being bought | 1.0 | - | - |

| Rent/other | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) | - | - |

| Household size (# of people in household) | |||

| Single | 1.0 | - | - |

| 2 | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | - | - |

| ≥ 3 | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | - | - |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/living with partner | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 2.0 (1.7-2.4) | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) |

| Never married | 1.6 (1.2-2.0) | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) |

| Medical office visits in past year | |||

| 0-1 visits | 1.0 | 1.0 | - |

| 2-4 visits | 1.5 (1.1-2.0) | 1.6 (1.2-2.2) | - |

| ≥5 visits | 3.3 (2.4-4.5) | 3.4 (2.5-4.4) | - |

| Health insurance status | |||

| Have health insurance | 1.0 (0.7-1.3) | - | - |

| No health insurance | 1.0 | - | - |

| Delayed healthcare due to cost (ref = no) | 1.5 (1.3-1.9) | - | - |

|

Received government assistance last calendar year

(ref = no) |

3.0 (2.5-3.6) | - | - |

| Income-to-poverty ratio (10.6% missing) | |||

| (Below or near poverty) < 2.00 | 2.9 (2.5-3.4) | 2.5 (2.1-3.0) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) |

| ≥2.00 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Most educated household adult | |||

| Less than high school | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | - | - |

| GED or high school graduate | 1.0 | - | - |

| Some college, no degree | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | - | - |

| College degree or more | 0.6 (0.5-0.7) | - | - |

| Personal Factors | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| 18-44 | 1.0 | 1.0) | - |

| 45-64 | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | - |

| 65+ | 1.5 (1.2-2.0) | 1.2 (1.0-1.6) | - |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) |

| Hispanic | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) | 1.0 (0.7-1.3) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 1.7 (1.2-2.4) | 1.7 (1.2-2.4) | 1.4 (1.0-1.9) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 2.1 (1.7-2.5) | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) | - |

| GED or high school graduate | 1.0 | 1.0 | - |

| Some college, no degree | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | - |

| College degree or more | 0.6 (0.5-0.8) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | - |

| Employment status | |||

| Working | 1.0 | - | - |

| Not working | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) | - | - |

| Current smoker (ref = no) | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) |

| Physical activity level-aerobic | |||

| Recommended | 1.0 | 1.0 | - |

| Insufficient | 2.3 (1.6-3.3) | 2.0 (1.5-2.9) | - |

| Inactive | 6.1 (4.6-8.1) | 4.8 (3.6-6.4) | - |

| ≥24 hours homeless or in jail (ref = no) | 1.9 (1.5-2.4) | - | - |

|

Retrieve health information from the internet

(ref = no) |

0.4 (0.3-0.5) | - | - |

NOTE: The Multivariate ICF domain-specific models column presents associations for each domain examined independently. The Meta Multivariate model column presents associations for all ICF domains examined simultaneously in the same model.

A detailed discussion of the unadjusted associations is presented in Appendix B.

Correlates of SPR, Domain-Specific Multivariable Models (Table 2)

Impairments

After multivariable adjustment, serious psychological distress continued to be the impairment most strongly associated with SPR (PR=2.5). There was ≥50% increased probability of SPR among those with severe joint pain, ≥3 selected comorbid conditions, and ≥9 hours of sleep.

Limitations

Those with key limitations were 31 times more likely to report SPR compared with those without key limitations (PR = 31.2, CI=22.3-43.5).

Environmental Factors

The highest frequency of office visits in the past year (≥5) and <2.00 income-to-poverty ratio were the strongest correlates of SPR in the multivariate environmental model; each was associated with a more than double increase in the likelihood of SPR (PR = 3.4 and 2.5, respectively).

Personal Factors

There were small increases in the likelihood of SPR for women and smokers (PR=1.3 for both). Non-Hispanic Others and those with less than a high school education had at least a 70% greater likelihood of SPR. The strongest associations with SPR were for low physical activity (insufficient and inactive, PR=2.0 and 4.8, respectively).

Multivariable correlates of SPR, Meta-Model(Table 2)

No personal domain variables remained significant in the meta-model. Also, the strength of association between SPR and key limitations was attenuated in the meta-model, dropping to PR=24.3 (16.8-35.1). Nevertheless, key limitations remained the single strongest correlate of SPR after adjustment, with the remaining significant PRs demonstrating associations between 30 and 40% higher likelihood of SPR.

Discussion

By identifying the characteristics of adults with arthritis who are most likely to have SPR, researchers can further refine the development and targeting of interventions that enhance quality-of-life and decrease disability and healthcare costs. Our results provide the first population-based examination of arthritis disability in U.S. adults using all ICF domains. Our approach extends the literature by presenting both ICF domain-specific multivariate models and a meta-model to demonstrate associations with SPR. The domain-specific models present numerous potentially modifiable characteristics, while the meta-model results can be viewed as identifying priority areas with the strongest and possibly most important relationships requiring immediate resolution.

Findings from the domain-specific impairment multivariate model were consistent with existing literature. For example, using the same measure of serious psychological distress as in our study, Okoro et al. found that adults with disability and serious psychological distress were worse off than those with just self-reported disability (28). In our study, domain-specific multivariate association of serious psychological distress with SPR was quite strong (PR=2.5), and, coupled with existing evidence (28-31), suggests that people with arthritis could benefit from more aggressive and targeted control of mental health symptoms. Although the negative impacts of mental health effects and physical disability appear to be cyclical (32), it is reasonable to attempt to “break the cycle” through existing, effective but underused interventions—such as pharmacological- and cognitive behavioral therapy, self-management education, and aerobic exercise—for the depression and anxiety components of serious psychological distress among those with arthritis (30).

Among the variables that remained statistically significant in the meta-model, key limitations was by far the most strongly associated with SPR (PR= 24.3). This finding reiterates the importance of targeting the component activities (walking ¼ mile, standing for about 2 hours, carrying something weighing about 10 pounds) for improved performance among people with arthritis. Both aerobic and muscle strengthening exercise programs have been shown to improve pain, functional performance measures (6 minute walk, timed up-and-go, chair stands, etc.), self-reported physical function (e.g., Health Assessment Questionnaire score), cardiorespiratory fitness (endurance), strength, and balance in randomized controlled and comparative effectiveness trials among adults with arthritis (33-36). Improvements in impairments and limitations via exercise may delay or reduce risk of disability. For example, the Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial reported an approximately 43% reduced risk of incident activity of daily living disability 18 months after a structured aerobic and muscle strengthening intervention among older adults with osteoarthritis (37).

The persistent association of severe joint pain with SPR after all adjustments in the meta-model (PR=1.4) was expected and is consistent with existing literature regarding joint pain in people with arthritis. For example, Wilkie et al. found that the highest level of knee pain severity was strongly associated with restricted mobility outside of the home (adjusted OR=2.4) (13). Hawker et al. determined that unpredictable, intense, emotionally draining pain “resulted in significant avoidance of social and recreational activities” (38). Osteoarthritis pain impact on sleep onset and continuation was also associated with greater disability, fatigue, and mood disturbances (38). These findings call into question whether the participants in our study reporting ≥9 hours of sleep per 24 hours are actually sleeping that entire time and what the quality of their sleep is; a low quality of sleep may explain the association between high number of sleeping hours and SPR. Unfortunately, quality of sleep was not assessed in the NHIS.

Arthritis pain, while complex, is treatable. Over-the-counter medications (acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications), topical preparations (Capsaicin), thermal modalities (heat and cold packs), aerobic, aquatic, and muscle strengthening exercise, weight loss, assistive devices (e.g., cane or crutch), orthotics/braces, and self-management education have all been shown to reduce osteoarthritis pain (39, 40). In cases where pain is not controlled with these first line treatments, intra-articular corticosteroid injections, hyaluronate injections, duloxetine, and opioids can be used (39, 40). In review of this evidence, it seems clear that uncontrolled pain among people with arthritis is substantially damaging to their function and quality-of-life and that better control of joint pain could have positive cascading effects on sleep, mental health, and disability.

The literature has demonstrated that poor socioeconomic status is associated with poor health outcomes in general (41, 42) and for specific condition groups, including arthritis (43, 44). Our study shows univariate (PR=2.9), domain-specific multivariate (PR=2.5), and meta-model (PR=1.4) associations between <2.00 income-to-poverty ratio and SPR. In addition to income-to-poverty ratio, two other measures, delayed healthcare due to cost (PR=1.5) and received government assistance (PR=3.0), had strong univariate associations with SPR, suggesting that financial resources may have a key role in the process of arthritis disability. These findings may have important policy implications both from the perspectives of reducing and addressing disability among adults with arthritis (45).

This study has at least four limitations. First, doctor-diagnosed arthritis was self-reported and may be subject to recall bias. This case-finding question, however, is considered valid for public health surveillance (46, 47). Second, cross-sectional study data cannot be used to infer causation. Third, there were conceptual limitations in variables available to measure some elements; e.g., marital status and household size were also proxies for the broader concept of a social network. Similarly, as described in the introduction, social participation can be conceptualized in many ways, so our measure of SPR assesses only those aspects captured in the NHIS questions, which represent the “capacity” aspect of participation. The ICF defines “capacity” as what an individual can do in a standard environment without barriers or facilitators to participation and “performance” as what an individual can do in their usual environment including barriers (e.g., no sidewalks) and facilitators (e.g., walking aids). If the NHIS measured the performance of social participation, the proportion with SPR may have been lower (48). Fourth, the NHIS does not measure all ICF elements, so some important concepts were not included. In particular, there were no available variables on specific environmental characteristic (e.g., built environment features such as sidewalks, curbs, transportation access) whose modification, especially in conjunction with assistive mobility technologies, could be expected to influence SPR (49).

This study has several strengths. First, the NHIS is a unique and rich data source for examining ICF-based correlates of disability, represented by SPR, including personal and environmental factors frequently absent from clinical studies. Next, the study had a sufficiently large sample to estimate precise moderate associations in the meta-model. Third, this is also the first nationally representative application of the ICF among adults with arthritis, and the findings are generalizable to U.S. adults with arthritis. This study has addressed a gap by providing an inclusive, descriptive application of the ICF to arthritis in the U.S. Fourth, our findings can be used to develop applied research questions to explore arthritis impacts and relationships to improve our understanding of and ability to modify adverse arthritis outcomes, including SPR.

Social participation represents an important life domain for many people. Social activity has longitudinal associations of decreased risk of incident disability among community-dwelling older adults (50), and a growing number of studies demonstrate the potentially protective effects of “having and retaining favorite pastimes” (32). Our study findings empirically demonstrate some of the complex relationships across ICF domains and provide priority areas for clinical and public health interventions to decrease pain, address mental health impacts, control arthritis symptoms, and create environments in which people with limitations or impairments are still able to participate.

Significance and Innovations.

2-4 bullet points highlighting the significance and/or innovative findings from your article

This is the first nationally representative application of the ICF among U.S. adults with arthritis.

5.7 million U.S. adults with arthritis report social participation restriction

We observed a novel association between social participation restriction and sleep among adults with arthritis.

An income-to-poverty ratio of <2.00 and other measures of assets and public assistance suggest financial resources may have a key role in the process of arthritis disability.

Appendix B

Population Characteristics (Table 1)

The majority of adults with arthritis were non-Hispanic white (77.8%), and women (60.1%); a plurality were 45 to 64 years of age (45.8%). Respondents tended to be fairly well educated, with 31.1% having at least a college degree. Nearly a third of respondents (30.6%) reported an income-to-poverty ratio <2.00. Most respondents were either overweight (34.4%) or obese (38.3%). Nearly one in six respondents reported serious psychological distress. Prevalence of the nine specific activity limitations ranged from 5.5% (grasp) to 27.2% (stoop, bend, or kneel), and >12% of adults with arthritis had six limitations. More than four in ten (42.5%) reported ≥1 limitation, and almost a quarter (23.4%) reported ≥3 limitations.

Prevalence ratios, unadjusted (Table 2)

Impairments

There was a strong association between SPR and reporting serious psychological distress (PR=4.5), having ≥3 comorbid conditions (PR=4.2), and severe joint pain (PR= 3.4). People who reported 1-5 or ≥9 hours of sleep were moderately more likely to have SPR (PR = 2.3 and 2.6, respectively).

Activity Limitations

All limitations were significantly and strongly associated with SPR. PRs ranged from 5.2 (grasp) to 14.0 (stand), and five limitations (climb, push, carry, walk, stand) had a PR ≥ 10.0. Respondents with key limitations had the strongest association with PR = 31.2 (95% CI= 22.3-43.5).

Environmental Factors

Eight of the nine examined environmental factors had significant univariate associations with SPR. Living in a multiple person household (PR = 0.7) and a college-educated most educated adult in the household (PR =0.6) were protective for SPR. All remaining variables had at least one category that was associated with ≥50% greater likelihood of SPR. The strongest univarate associations were for an income-to-poverty ratio <2.00 (PR =2.9), receiving government assistance in the past year (PR =3.0), and ≥5 office visits in the past year (PR =3.3). Having health insurance did not have a significant relationship with SPR (PR= 1.0; 95% CI = 0.7-1.3).

Personal Factors

With the exception of employment, all examined personal factors were significantly associated with SPR. A college degree (PR= 0.6) and retrieving health information from the internet (PR=0.4) were protective. Less than a high school education (PR= 2.1) and insufficient physical activity (PR=2.3) or being inactive (PR=6.1) were most strongly associated with SPR.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Not all categories of contextual factors (e.g., attitudes) were available in the NHIS.

References

- 1.Cheng YJ, Hootman JM, Murphy LB, Langmaid GA, Helmick CG. Prevalence of Doctor-Diagnosed Arthritis and Arthritis-Attributable Activity Limitation - United States, 2007-2009. MMWR. 2010;59(39):1261–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yelin E, Murphy L, Cisternas M, Foreman A, Pasta D, Helmick CG. Medical care expenditures and earnings losses among persons with arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in 2003, and comparisons with 1997. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1397–407. doi: 10.1002/art.22565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brault MW, Hootman J, Helmick CG, Theis KA, Armour BS. Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults, United States, 2005. MMWR. 2009;58(16):421–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolf A, Akesson K. Understanding the burden of musculoskeletal conditions. The burden is huge and not refelcted in natinoal health priorities. BMJ. 2001;5:1079–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1079. 322(7294) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kostanjsek N. Use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a conceptual framework and common language for disability statistics and health information systems. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 4(S3)) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S4-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prodinger B, Cieza A, Williams DA, Mease P, Boonen A, Kerschan-Schindl K, et al. Measuring health in patients with fibromyalgia: content comparison of questionnaires based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(5):650–8. doi: 10.1002/art.23559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weigl M, Cieza A, Harder M, Geyh S, Amann E, Kostanjsek N, et al. Linking osteoarthritis-specific health-status measures to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2003;11(7):519–23. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(03)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollard B, Johnston M, Dieppe P. What do osteoarthritis health outcome instruments measure? Impairment, activity limitation, or participation restriction? J Rheumatol. 2006;33(4):757–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartzkopf SR, Ewert T, Dreinhofer KE, Cieza A, Stucki G. Towards an ICF Core Set for chronic musculoskeletal condtions: commonalities across ICF Core Sets for osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, low back pain and chronic widespread pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(11):1355–61. doi: 10.1007/s10067-008-0916-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weigl M, Cieza A, Cantista P, Reinhardt JD, Stucki G. Determinants of disability in chronic musculoskeletal health conditions: a literature review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2008;44(1):67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkie R, Peat G, Thomas E, Croft P. Factors associated with participation restriction in community-dwelling adults aged 50 years and over. Quality Of Life Research: An International Journal Of Quality Of Life Aspects Of Treatment, Care And Rehabilitation. 2007;16(7):1147–56. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkie R, Peat G, Thomas E, Croft P. Factors associated with restricted mobility outside the home in community-dwelling adults ages fifty years and older with knee pain: an example of use of the International Classification of Functioning to investigate participation restriction. Arthritis And Rheumatism. 2007;57(8):1381–9. doi: 10.1002/art.23083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkie R, Thomas E, Mottram S, Peat G, Croft P. Onset and persistence of person-perceived participation restriction in older adults: a 3-year follow-up study in the general population. Health And Quality Of Life Outcomes. 2008;6:92. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gignac M, Backman C, Davis A, Lacaille D, Mattison C, Montie P, et al. Understanding social role participation: what matters to people with arthritis? J Rheumatol. 2008;35(8):1655–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machado G, Gignac M, Badley E. Participation restrictions among older adults with osteoarthritis: a mediated model of physical symptoms, activitiy limitations, and depression. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(1):129–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Botha-Scheepers S, Watt I, Rosendall F, Breedveld F, Hellio le Graverand M, Kloppenburg M. Changes in outcome measures for impairment, activity limitation, and participation restriction over two years in osteoarthritis of the lower extremities. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(12):1750–5. doi: 10.1002/art.24080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Center for Health Statistics . Data file documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2009 (machine readable data file and documentation) National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Hyattsville (MD): 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen M, Turner J, Romano J, Fisher L. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain. 1999;83:157–62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapstad H, Hanestad B, Langeland N, Rustoen T, Stavern K. Cutpoints for mild, moderate and severe pain in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee ready for joint replacement surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9(55) doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, et al. Short Screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–76. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knutson KL. Sleep duration and cardiometabolic risk: A review of the epidemiologic evidence. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;24:731–43. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor B, Smith J. Current Population Reports, P60-238, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2009. Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health and Human Services . Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. USA: Oct, 2008. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.SAS Institute . SAS/STAT User's Guide. Version 9. SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schenker N, Gentleman J. On Judging the significance of differences by examing the overlap between confidence intervals. The American Statistician. 2001;55(3):182–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allison P. Logistic regression using the SAS system. Wiley Interscience, SAS Institute; Cary (NC): 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okoro CA, Strine TW, Balluz L, Crews JE, Dhingra S, Berry JT, et al. Serious psychological distress among adults with and without disabilities. Int J Public Health. 2009;54:S52–S60. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunlop D, Semanik P, Song J, Manheim L, Shih V, Chang R. Risk factors for functional decline in older adults with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1274–82. doi: 10.1002/art.20968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy LB, Sacks J, Brady TJ, Hootman JM, Chapman DP. Anxiety is more common than depression among U.S. adults with arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012 doi: 10.1002/acr.21685. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunlop D, Manheim L, Song J, Lyons J, Chang R. Incident disability among preretirement adults: The impact of depression. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(11):2003–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parmelee PA, Harralson TL, Smith LA, Schumacher HR. Necessary and discretionary activities in knee osteoarthritis: do they mediate the pain-depression relationship? Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass) 2007;8(5):449–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Callahan L, Mielenz T, Freburger J, Shreffler J, Hootman J, Brady T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the People with Arthritis Can Excercise Program: Symptoms, function, physical activity, and psychosocial outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(1):92–101. doi: 10.1002/art.23239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Callahan L, Shreffler J, Altpeter M, Schoster B, Hootman J, Houenou L, et al. Evaluation of group and self-directed formats of the Arthritis Foundation's Walk With Ease Program. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(8):1098–107. doi: 10.1002/acr.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelley G, Kelley K, Hootman JM, Jones D. Effects of community-deliverable exercise on pain and physical function in adults with arthritis and other rheumatic diseases: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(1):79–93. doi: 10.1002/acr.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ettinger W, Jr., Burns R, Messier S, Applegate W, Rejeski W, Morgan T, et al. A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST) JAMA. 1997;277(7):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pennix B, Messier S, Rejeski W, Williamson J, DiBari M, Cavazzini C, et al. Physical exersice and the prevention of disability in activities of daily living in older persons with osteoarthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(19):2309–16. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.19.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hawker G, Stewart L, French M, Cibere J, Jordan J, March L, et al. Understanding pain experience in hip and knee osteoarthritis--an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2008;16:415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hochberg M, Altman R, Toupin K, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies for osteoarthritis of the hand, hip and knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 doi: 10.1002/acr.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang W, Nuki G, Woskowitz R, Abramson S, Altman R, Arden N, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systemic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2010;18(4):476–99. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marra C, Lynd L, Harvard S, Grubisic M. Agreement between aggregate and individual-level measures of income and education: a comparision across three patient groups. BMC Health Services Research. 2011;11(69) doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-69. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/11/69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Franks P, Gold M, Fiscella K. Sociodemograhpics, self-rated health, and mortality in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(12):2505–14. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobi C, Mol G, Boshuizen H, Rupp I, Dinant H, Van Den Bos G. Impact of socioeconomic status on the course of rheumatoid arthritis and on related use of health care services. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(4):567–73. doi: 10.1002/art.11200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrison M, Tricker K, Davies L, Hassell A, Dawes P, Scott D, et al. The relationship between social deprivation, disease outcome measures, and response to treatment in patients with stable, long-standing rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(12):2330–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yelin E. Health policy and musculoskeletal conditions. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1992;4(2):167–73. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199204000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bombard J, Powell K, Martin L, Helmick CG, Wilson W. Validity and reliability of self-reported arthritis: Georgia senior centers, 2000-2001. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:251–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sacks J, Harold L, Helmick CG, Gurwitz J, Emani S, Yood R. Validation of a surveillance case definition for arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:340–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katz P, Morris A. Use of accommodations for Valued Life Activities: Prevalence and effects on disability scores. Arthritis Care Res. 2007;57(5):730–7. doi: 10.1002/art.22765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Theis KA, Furner S. Shut-In? Impact of chronic conditions on community participation restriction among older adults. J Aging Res. 2011;2011 doi: 10.4061/2011/759158. (Epub 2011 Aug 3):Article ID 759158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.James B, Boyle P, Buchman A, Bennett D. Relation of late-life social activity with incident disability among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66A(4):467–73. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]