Abstract

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal disorder in which cells of the myeloid lineage undergo massive clonal expansion as well as resistance to conventional chemotherapy. Gene therapy hold a great promise for treatment of malignancies based on the transfer of genetic material to the tissues. In this study, we explore whether chimeric oncolytic adenovirus-mediated transfer of human interleukin-24 (IL-24) gene induce the enhanced antitumor potency. Our results showed that chimeric oncolytic adenovirus carrying hIL-24 (AdCN205-11-IL-24) could produce high levels of hIL-24 in CML cancer cells, as compared with constructed double-regulated oncolytic adenovirus expressing hIL-24 (AdCN205-IL-24). AdCN205-11-IL-24 could specifically induce cytotoxocity to CML cancer cells, but little or no effect on normal cell lines. AdCN205-11-IL-24 exhibited remarkable anti-tumor activities and induce higher antitumor activity to CML cancer cells by inducing apoptosis in vitro. Our study may provides a potent and safe tool for CML gene therapy.

Keywords: Chimeric oncolytic adenovirus, chronic myeloid leukemia, fiber, IL-24 gene, gene-therapy

Introduction

Remarkable advances have been made in the past decades in our understanding of the molecular genetic basis of human leukaemias. The vast majority of leukaemias are sporadic, and are the consequence of acquired somatic mutation in haematopoietic progenitor cells.

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML)-a haematological stem-cell disorder that is characterized by excessive proliferation of cells of the myeloid lineage-represented a particularly interesting case. CML is characterized by a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22. The shortened version of chromosome 22, which is known as the Philadelphia chromosome, was discovered by Nowell and Hungerford, and provided the first evidence of a specific genetic change associated with human cancer [1,2]. The molecular consequence of this inter-chromosomal exchange is the creation of the BCR-ABL gene, which encodes a protein with elevated tyrosine-kinase activity [3]. The discovery and development of Glivec has shown that is possible to produce rationally designed, molecular-targeted drugs for the treatment of a specific cancer [4]. At present, the gene therapy may be offering new hope for expanded treatment options for patients with CML.

Gene therapy offers a new approach for treatment of cancer. It is based on the introduction of genetic material into the cells of the patient with the aim of producing a therapeutic effect [5-7]. The anti-tumor activities of adenovirus have been widely studied, but the mechanism by which adenovirus induces cancer cell death remains elusive. Oncolytic viruses have been used to crack tumor cellls directly and at the same time used to express therapeautic genes of anti-tumor [8,9]. Therefore, there are kinds of viruses, including adenovirus, adeno-associated virus, herpes simplex virus, retroviruses, lentivirus, hepatitis B virus, and Newcastle disease virus, genetically manufactured to adapt for therapy of cancer [8-13]. The common strategy used to design oncolytic adenoviruse is to recode adenoviral E1A protein. The CR2 region of adenoviral E1A could bind to retinoblastoma protein (RB) and the RB-related proteins and the proteins regulate the E2F family of transcription factors. Since the tumor cells often have dysfunctional RB, deletion of CR2 region allows this engineered adenovirus to selectively replicate in tumor cells but not in quiescent normal cells [14,15]. Previously, we have constructed several conditionally replicative adenovirus systems which viral replication was only occurred in cancer cells with high expression of hTERT and abnormal cell cycle checkpoint [16,17]. We have constructed the AdCN205 system, in which therapeutic gene expression is controlled by adenovirus E3 endogenous promoter. We have proven that this vector could express therapeutic genes in a predictable and safe manner [18]. The Human adenovirus serotype 11 (Ad11), with a fiber different from that of Ad5, can entry cells which could secrete complement regulatory proteins CD46 (a specific membrane protein) to cytomembrane. Ad11 adenoviral vector is an alternative tool for leukemia cancer therapy [19,20]. Therefore, we have developed the AdCN205-11 system to selectively replicate in chronic myeloid leukaemia cell lines and exhibit remarkable antitumor activity.

Different cytokines or chemokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7; IL-12, GM-CSF) have been used to activate antitumoral activity. IL-24 is among the cytokines with most potent antitumoral activity. The melanoma differentiation-associated gene-7 (mda-7) was cloned by subtraction hybridization as a molecule whose expression is elevated in terminally differentiated human melanoma cells. Current information based on structural and sequence homology, has led to the recognition of MDA-7 as an IL-10 family cytokine member and its renaming as IL-24 [21]. A notable property of MDA-7/IL-24 is its ability to induce apoptosis in a large spectrum of human cancer derived cell lines, in mouse xenografts and upon intratumoral injection in human tumors (phase I clinical trials). IL-24 can induce tumor cell apoptosis, inhibit angiogenesis and has a bystander effect [22,23]. In addition to increasing immunity, IL-24 is widely used in cancer gene therapy for a dramatic antitumor effect [18,24]. We have shown that the application of IL-24 in the gene therapy system not only results in a strong antitumor effect, but also enhances the effect of other therapeutic genes such as TRAIL, p53; chemotherapeutic agents such as ADM, DDP and dichloroacetate, and RNA interference, such as shRNA-COX2 [25-28].

Materials and methods

Cell cultures

The K562 (Human chronic myeloid leukemia cell) cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA). The L02 (Normal human liver cell) cell line was purchased from the Shanghai Cell Collection (Shanghai, China). The HEK293 cell line was purchased from Microbix Biosystems Inc. (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). K562 cell lines was grown in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS. L02 and HEK293 cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO BRL), 4 mM glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin ,and 50 mg/ml streptomycin. All cell lines were incubated at 37°C in a humidified air atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Construction of oncolytic adenoviral vectors

The constructs including pCN205-11-EGFP and pCN205-11-IL-24 were generated according to the standard molecular cloning protocol. The homologous recombination between pCN205-11-EGFP and pCN205-11-IL-24 plasmids and pCN103 plasmid carrying oncolytic adenoviral backbone was done in was done in E.coli strain BJ5183, to create pAdCN205-EGFP and pAdCN205-IL-24, respectively. Viral particles were produced in HEK293 cells by transfection with PacI-digested pAdCN205-EGFP and pAdCN205-IL-24 to obtain recombinant AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24.

Generation, purification and titration of recombinant adenoviruses

To get the viruses, the plasmid pCN205-11-EGFP and pCN205-11-IL-24 were digested by PacI and transfected into HEK293 cells by Effectene (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The recombinant adenoviruses were amplified in HEK293 cells and purified by cesium chloride gradient ultracentrifugation. The titration of recombinant adenovirus was carried out with tissue culture infectious dose 50 assays on HEK293 cells.

Virus progeny assay

To determine virus progeny, chronic myeloid leukemia or normal cells were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-EGFP, or AdCN205-11-IL24 at a MOI of 10. After 48 h, the supernatants and cells were collected separately. The cells were resuspended in PBS, and the virus was released by freeze and thaw for three cycles. Virus production in supernatants and cell lysates were determined by tissue culture infectious dose 50 assays on HEK293 cells.

Cell viability by the colorimetric MTT assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1×104 per well. When cells grew to subconfluence, they were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-EGFP, or AdCN205-11-IL24 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Fresh medium containing 0.5 mg/ml (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-dipenyltetrazolium bromide) (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) solution was added to each well at different time after infection. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h, and then 150 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to each well and mixed thoroughly for 10 min. Absorbance was read at 595 nm with a DNA expert (Tecan, Switzerland). The percentage of cell viability was calculated as follows: (mean A595 of infected cells)/(mean A595 of uninfected cells) ×100%.

In vitro transduction studies

For suspension cells, the day before infection, 3×105 k562 cells per well (24-well plate) were seeded. The next day, attached cells were counted and viruses were added at the multiplicities of infection (MOI) indicated in the figure legends in 1 ml of growth medium. Cells were incubated with virus for hours, incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Percentages of GFP-positive cells were detected by fluorescent microscopy.

Apoptotic cell staining

The k562 cells were cultured in each well (4×105) of 6-well plates. The 12 hours later, the cells were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-EGFP, or AdCN205-11-IL24 at a MOI of 10. Forty-eight hours after infection, the medium was replaced with PBS and then the cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (25 µg/mL). The percentage of apoptotic cells was analyzed with and observed under the fluorescence microscope.

Flow cytometric analysis

To quantitate apoptosis using flow cytometry analysis, the k562 cells were seeded in 6-well culture plates and infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-EGFP, or AdCN205-11-IL24 at a MOI of 10. Cells infected with adenovirus were trypsinized and washed once with complete medium. Aliquots of cells (1×105) were resuspended in 500 μl of binding buffer and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled annexin V and propidium iodide ((BioVision, Palo Alto, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. A fluorescence-activated cell sorting (BD Biosciences) assay was performed immediately after staining. To determine transduction efficiency of the virus, k562 cells were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-IL-24 at an MOI of 10 for 48 h, and then subjected to flow cytometric analysis.

Western blotting analysis

To determine the expression of various proteins, western blot analysis was performed as described previously. Total proteins were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride filter membranes (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk, incubated with primary antibodies, detected by the appropriate secondary antibodies, and revealed with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The primary antibodies included rabbit monoclonal anti-mda-7 (melanoma differentiation associated gene 7)/IL-24(Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1/2 (H-250) rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), β-actin, rabbit monoclonal (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA). The membranes were then incubated with anti-rabbit infrared dye 700. The fluorescent signal was detected with an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times. Statistical analyses were done with Student’s t test to determine the significance. Pearson’s m2 test was also used to test the hypothesis of no association of columns and rows in tabular data. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The constructiom of the chimeric oncolytic adenoviral vectors

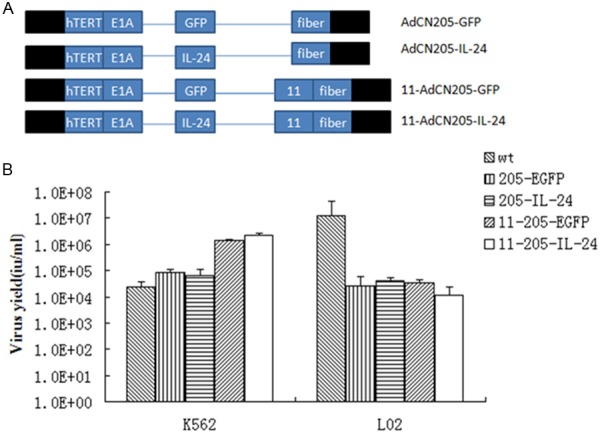

Previously, our group have successfully constructed an efficient tumor-selective oncolytic adenovirus system, AdCN205, in which hTERT promoter was used to control the expression of CR2 deleted E1A region and the 6.7 K/gp19 K of E3 region were substituted by the exogenous genes. And then, when adenoviruses infect and replicate in tumor cells, the exogenous genes, usually anti-tumor genes, in the vector controlled by the adenovirus endogenous E3 promoter are also expressed in the tumor cells and against uncontrolled tumor cells. In the present study, most importantly, human adenovirus serotype 11 (Ad11) with a fiber different from that of Ad5 can entry cells which could secret complement regulatory proteins CD46 (a specific membrane protein) to cytomembrane. Ad11 adenoviral vector is an alternative means for cancer therapy, especially leukemia. We constructed AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL24 by the fibers on the human adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) replacing with the human adenovirus type 11 (Ad11). The structures of AdCN205-GFP, AdCN205-IL24, AdCN205-11-GFP and AdCN205-11-IL24 were shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Construction and characterization of chimeric oncolytic adenoviral vectors. A. Structures of chimeric oncolytic adenoviral vectors carrying EGFP and IL-24. Schematic description of the structures of AdCN205, AdCN205-11-GFP and AdCN205-11-IL24. In AdCN205, the E1A promoter was replaced by hTERT promoter and deletion of the adenoviral genome 923 to 946 nucleotides, which enables viral replication within malignant cells with abnormal RB functions. The fibers on the human adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) replacing with the human adenovirus type 11 (Ad11). In AdCN205-GFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-GFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24, were substituted by GFP reporter gene and hIL-24 therapeutic gene, respectively. B. Selective replication of recombinant adenoviruses in vitro. The Chronic myeloid leukaemia cell lines (K562) and normal cell lines (L02) were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24 at a MOI of 10. After 48 h, the supernatants and cells were collected separately. The cells were resuspended in PBS and subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles. The virus yield was measured in supernatants and cell lysates. *P<0.01 as compared with groups of AdCN205-EGFP or Ad-wt group. IL-24, interleukin-24; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MOI, multiplicity of infection.

Selective replication chimeric oncolytic adenoviral vectors in vitro

In order to transduce the IL-24 gene into chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) cells with high efficiency, our group engineered recombinant oncolytic adenoviral vectors carrying IL-24 (AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24). To examine whether transgenes could interfere with the selective replication ability of recombinant adenoviruses, a progeny assay was made in CML cells (K562) and normal cells (L02) infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24 at MOI of 10. As shown in Figure 1B. AdCN205-11-IL-24 and AdCN205-11-EGFP replicated at similar levels in CML cells, which were comparable to CML cells infected with Ad-wt,AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24. In contrast, the replication capacity of these vectors was much reduced in normal cells. These data indicated that expression of IL-24 and EGFP did not affect the selective replication ability of oncolytic vectors.

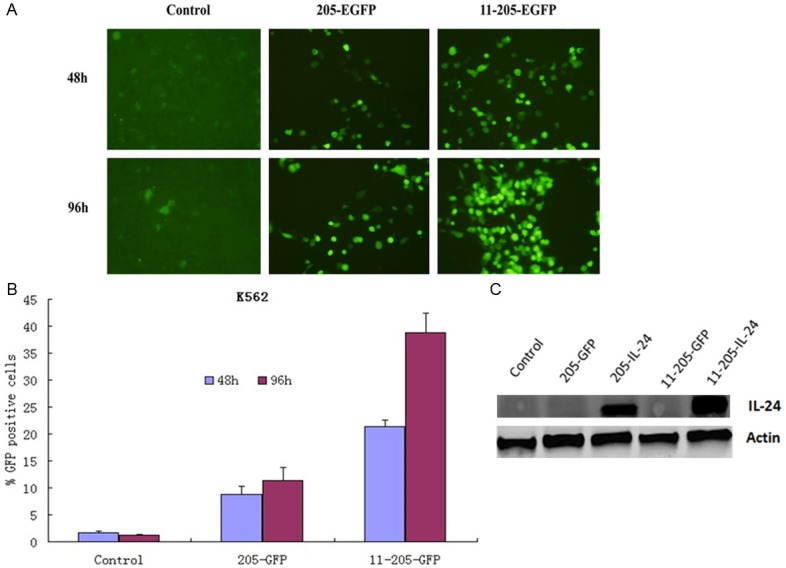

To confirm whether exogenous gene could be expressed properly in the CML cells infected with oncolytic adenoviruses, the K562 cell lines was infected with AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-11-EGFP or Ad-wt at the MOI of 10. Our results showed that the K562 cells infected with AdCN205-11-EGFP expressed a high level of EGFP protein and as compared with the K562 cells infected with AdCN205-EGFP or Ad-wt by observed under a fluorescence microscope. Figure 3A.

Figure 3.

Specific selective replication of recombinant adenoviruses in vitro. A. Representative photomicrographs was obtained from K562 cells infected with AdCN205-EGFP AdCN205-11-EGFPor Ad-wt at a MOI of 10. Original magnification, 200×. B. The transduction efficiency of the virus, K562 cells were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-11-EGFP at a MOI of 10 for 48, 96 h, and then subjected to flow cytometric analysis. CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MOI, multiplicity of infection. C. Detection of IL-24 in K562 cells after infection with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24 at a MOI of 10. The total protein from those treated cells after 48 h of infection was subjected to western blotting with antibodies against total IL-24 and β-actin. IL-24, interleukin-24; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MOI, multiplicity of infection.

To estimate the transduction efficiency of the recombinant oncolytic adenoviral, K562 cells were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, or AdCN205-11-EGFP at an MOI of 10 for 48 h, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. Figure 3B. The AdCN205-11-EGFP was illustrated specificity selective replication ability to K562 cells then Ad-wt or AdCN205-EGFP.

Thus, these results indicated that chimeric oncolytic adenoviral vectors armed with IL-24 could selectively replicate in CML cells, but not in normal cells.

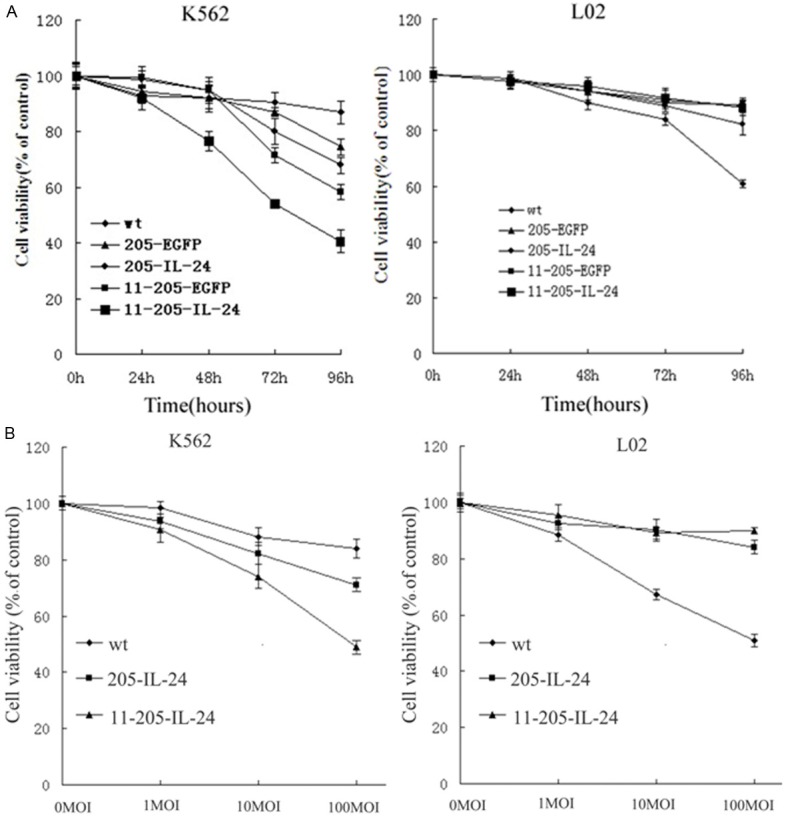

Cytotoxicity induced by chimeric oncolytic adenoviral vectors in Chronic myeloid leukaemia cells in vitro

To investigate the antitumor ability of the recombinant adenoviruses with therapeutic gene mda-7/IL-24 to wreck tumor cells, we conducted cytotoxicity assay of the cells after infection with chimeric oncolytic adenoviruses. The chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) cell lines (K562) and a normal cell line (L02) were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24 at an MOI of 10. And cell survival was determined by MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-dipenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. As shown in Figure 2, The AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, and Ad-wt could induce apparent cytotoxicity to CML cells at a similar level in a time-dependent manner. Moreover, AdCN205-11-IL-24 could significantly reduce the viability of CML cells, as compared with that induced by Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24 or AdCN205-11-EGFP. In contrast, oncolytic adenoviruses AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24 did not induce equal cytotoxicity to normal cell line L02. Furthermore, we observed increased cytotoxicity to CML cells in a dose-dependent manner, as compared with that induced by AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24or Ad-wt (Figure 3B). These result suggested that AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24 can selectively replicate in cancer cells and AdCN205-11-IL-24 displayed a powerful efficacy in killing CML cells in vitro.

Figure 2.

Induction of cytotoxicity by chimeric oncolytic adenoviral vectors in vitro. A. Chronic myeloid leukaemia cell lines (K562) and normal cell lines (L02) were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24 at a MOI of 10. Cell viability was determined by (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-dipenyltetrazolium bromide) assay at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 96 h after infection. B. K562 and L02 cells were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-IL-24 and AdCN205-11-IL-24 at different MOIs. Cell viability was determined by (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dipenyltetrazolium bromide) assay at 48 h after infection. The cell viability was calculated as a percentage with respect to cells without viral infection. Data were presented as the means ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *P<0.01 as compared with groups of AdCN205-EGFP or Ad-wt. IL-24, interleukin-24; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MOI, multiplicity of infection.

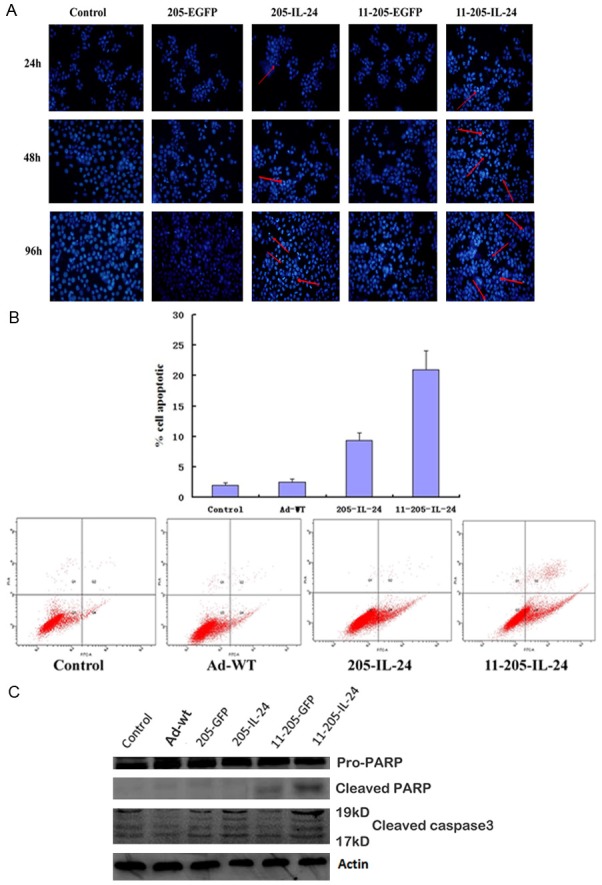

Induction of apoptosis in Chronic myeloid leukaemia cells after infection with chimeric oncolytic adenoviral vectors

To confirm whether exogenous expression of IL-24 could induce apoptosis in CML cells, CML cells were infected with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24 AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN-205-11-IL-24 at an MOI of 10 for 48 h. Figure 4A shows that infection of K562 cell with AdCN205-11-IL-24 led to remarkably morphological changes representing apoptosis. Evidence of apoptotic cell death was revealed by features such as chromatin condensation in K562 cells. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was performed to examine apoptosis induced by AdCN205-11-IL-24. Our results indicated that the apoptotic proportion induced by AdCN205-11-IL-24 was significantly higher than that induced by AdCN205-11-EGFP, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24 or Adwt. Figure 4B. Furthermore, activation of the caspase-dependent apoptosis pathway was examined to explore the mechanism of CML cell apoptosis. Expression of key proteins involved in the extrinsic apoptosis pathways was evaluated by western blotting. As shown in Figure 4C, the cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP was obviously increased in K562 cells treated with AdCN205-11-IL-24, as compared with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCNE205-11GFP or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). These results suggested that AdCN205-11-IL-24 could remarkably induce the apoptosis of k562 cells by activation of the caspase-dependent apoptosis pathway. Figure 4C.

Figure 4.

Expression of IL-24 and Induction of cell apoptosis in CML cells after infection with AdCN205-11-IL-24 in vitro. A. Chronic myeloid leukaemia cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 after infection with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24 AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24 at a MOI of 10 for 48 h. Arrows indicated positive apoptotic cells. Original magnification, ×100. B. Detection of apoptosis by staining with anti-annexin V in K562 cells after infection with Ad-wt, AdCN205-IL-24 and AdCN205-11-IL-24 at a MOI of 10, after 48 h by the Flow cytometric analysis. C. Detection of cleaved caspase 3 and PARP in K562 cells after infection with Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24, AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24 at a MOI of 10. The total protein from those treated cells after 48 h of infection was subjected to western blotting with antibodies against total cleaved caspase 3 and PARP and β-actin. IL-24, interleukin-24; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MOI, multiplicity of infection.

Discussion

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal myeloproliferative disorder characterized by the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome, which results from t (9; 22) balanced reciprocal translocation. The molecular consequence of the Ph chromosome is the generation of the BCR-ABL oncogene that encodes for the chimeric BCR-ABL oncoprotein, with constitutive kinase activity that promotes the growth advantage of leukemic cells [2,3]. This represents a critical issue in the effort to design molecular therapies.

Conventional therapeutic options include interferon-based regimens and stem cell transplantation, with stem cell transplantation being the only curative therapy. Through rational drug development, STI571, a Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has emerged as a paradigm for gene product targeted therapy, offering new hope for expanded treatment options for patients with CML [4]. Biological therapies, including gene therapy, have shown great promise for the treatment of CML. However, present strategies are not effective enough to eliminate cancer completely, particularly in human patients. Therefore, it is needed to explore the potent vectors and therapeutic genes for this purpose.

Studies by researchers have uncovered many of mda-7/IL-24’s unique properties, including cancer-specific apoptosis induction cell cycle regulation, an ability to inhibit angiogenesis, potent “bystander antitumor activity” and a capacity to enhance the sensitivity of tumor cells to radiation, chemotherapy and monoclonal antibody therapy. The mda-7/IL-24 represents a unique cytokine gene with potential for therapy of human cancers [22,23]. Our previous work has confirmed that mda-7/IL-24 exerted strong antitumor activity ability in vitro and in vivo [18]. Clinical trial with replication-defective adenovirus expressing IL-24 has shown a safe profile and some partial responses in patients with cancers. In this study, we investigated whether IL-24 could be used as therapeutic gene for treatment of CML.

To get targeting of chronic myeloid leukemia cells and improved safety in normal cells, it is needed to apply replication-competent viral vectors. It has shown that oncolytic adenoviruses could transduce tumor cells effectively and exhibit safety profile [29,30]. Our previous studies have constructed double-regulated oncolytic adenoviral vectors (AdCN205-EGFP and AdCN205-IL-24) that could target human telomerase reverse transcriptase and retinoblastoma pathways [15]. These double-regulated oncolytic adenoviral vectors showed that expression of transgenes was restricted to tumor cells. The high level of expression of IL-24 and adenoviral greatly improved the oncolytic effects of this vector under both in vitro and in vivo conditions. At the same time, we also had constructive of oncolytic adenoviral vectors that the fibers on the human adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) replacing with the human adenovirus type 11 (Ad11) can only targeting specificity selective replication of recombinant adenoviruses in leukemia cells. This vector only selectively infects and replicates in chronic myeloid leukemia cells [20,31,32]. Therefore, we used this triple-regulated chimeric oncolytic adenovirus AdCN205-11-IL-24 vector to deliver IL-24 gene (AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-11-IL-24) for the therapy of CML cells.

Our results showed that AdCN205-11-IL-24 exerted much strong cytotoxicity to CML cells compared with that induced by control vector AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24 or Ad-Wt. AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-11-EGFP and Ad-Wt induced similar cytotoxicity to CML cells. Our data revealed that the cytotoxic effect of the AdCN205-11-IL-24 is much higher than that induced by Ad-wt, AdCN205-EGFP, AdCN205-IL-24. In contrast, both AdCN205-11-EGFP and AdCN205-IL-24 did not induce cytotoxic effect to normal cells. We also demonstrated that transfer of IL-24 gene by AdCN205-11-IL-24 could dramatically expression in CML cells and AdCN205-IL-24 can hardly be detected. These data indicated that our newly constructed chimeric oncolytic adenoviral vectors not only maintained their intrinsic capacity of viral replication in tumor cells but also induced high and sustained expression of therapeutic gene. These results indicated that strong cytotoxic effect of AdCN205-11-IL-24 on CML cells might be induced by alternation of cell cycle and induction of cells’ apoptosis. Our data further demonstrated that AdCN205-11-IL-24 could induce cell apoptosis by induction of cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP, the important mechanisms for induction of the caspase-dependent cell apoptosis [33]. The study suggested that AdCN205-11-IL-24 could induce CML cell apoptosis through the activation of the caspase-dependent apoptosis pathway. The studies have also shown that arming oncolytic adenovirus with suicide gene or cytokine gene can also significantly increase therapeutic index [33,34].

In conclusion, we successfully constructed an efficient tumor-selectively triple-regulated chimeric oncolytic adenovirus AdCN205-11-IL-24, which was can selectively replicate in chronic myeloid leukemia cells and exhibit remarkable antitumor activity in vitro. Introduction of the IL-24 gene in the triple-regulated chimeric oncolytic adenovirus resulted could induce CML cells’ apoptosis through the activation of the caspase-dependent apoptosis’ extrinsic pathway in vitro. These data indicated that this new types of AdCN205-11-IL-24 can provide potent and safe tool for the therapy of chronic myeloid leukemia cancers.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Kelly LM, Gilliland DG. Genetics of myeloid leukemias. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2002;3:179–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.3.032802.115046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Dwyer ME, Mauro MJ, Druker BJ. Recent advancements in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:369–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cilloni D, Saglio G. Molecular pathways: BCR-ABL. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:930–937. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capdeville R, Buchdunger E, Zimmermann J, Matter A. Glivec (STI571, imatinib), a rationally developed, targeted anticancer drug. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:493–502. doi: 10.1038/nrd839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sangro B, Prieto J. Gene therapy for liver cancer: clinical experience and future prospects. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2010;12:561–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander BL, Ali RR, Alton EW, Bainbridge JW, Braun S, Cheng SH, Flotte TR, Gaspar HB, Grez M, Griesenbach U, Kaplitt MG, Ott MG, Seger R, Simons M, Thrasher AJ, Thrasher AZ, Yla-Herttuala S. Progress and prospects: gene therapy clinical trials (part 1) Gene Ther. 2007;14:1439–1447. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma IM, Weitzman MD. Gene therapy: twenty-first century medicine. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:711–738. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.050304.091637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qian C, Sangro B, Prieto J. New strategies to enhance gene therapy efficiency. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:639–642. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong HH, Lemoine NR, Wang Y. Oncolytic Viruses for Cancer Therapy: Overcoming the Obstacles. Viruses. 2010;2:78–106. doi: 10.3390/v2010078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian C, Liu XY, Prieto J. Therapy of cancer by cytokines mediated by gene therapy approach. Cell Res. 2006;16:182–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirn D, Martuza RL, Zwiebel J. Replication-selective virotherapy for cancer: Biological principles, risk management and future directions. Nat Med. 2001;7:781–787. doi: 10.1038/89901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singer O, Verma IM. Applications of lentiviral vectors for shRNA delivery and transgenesis. Curr Gene Ther. 2008;8:483–488. doi: 10.2174/156652308786848067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormick F. Cancer gene therapy: fringe or cutting edge? Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:130–141. doi: 10.1038/35101008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berk AJ. Recent lessons in gene expression, cell cycle control, and cell biology from adenovirus. Oncogene. 2005;24:7673–7685. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Cai R, Luo J, Wang Y, Cui Q, Wei X, Zhang H, Qian C. The oncolytic adenovirus targeting to TERT and RB pathway induced specific and potent anti-tumor efficacy in vitro and in vivo for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:1726–1732. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.11.4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui Q, Jiang W, Wang Y, Lv C, Luo J, Zhang W, Lin F, Yin Y, Cai R, Wei P, Qian C. Transfer of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 by an oncolytic adenovirus induces potential antitumor activities in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;47:105–112. doi: 10.1002/hep.21951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papadakis ED, Nicklin SA, Baker AH, White SJ. Promoters and control elements: designing expression cassettes for gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2004;4:89–113. doi: 10.2174/1566523044578077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo J, Xia Q, Zhang R, Lv C, Zhang W, Wang Y, Cui Q, Liu L, Cai R, Qian C. Treatment of cancer with a novel dual-targeted conditionally replicative adenovirus armed with mda-7/IL-24 gene. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2450–2457. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Segerman A, Mei YF, Wadell G. Adenovirus types 11p and 35p show high binding efficiencies for committed hematopoietic cell lines and are infective to these cell lines. J Virol. 2000;74:1457–1467. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1457-1467.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu L, Shimozato O, Li Q, Kawamura K, Ma G, Namba M, Ogawa T, Kaiho I, Tagawa M. Adenovirus type 5 substituted with type 11 or 35 fiber structure increases its infectivity to human cells enabling dual gene transfer in CD46-dependent and -independent manners. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:2311–2316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pestka S, Krause CD, Sarkar D, Walter MR, Shi Y, Fisher PB. Interleukin-10 and related cytokines and receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:929–979. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebedeva IV, Emdad L, Su ZZ, Gupta P, Sauane M, Sarkar D, Staudt MR, Liu SJ, Taher MM, Xiao R, Barral P, Lee SG, Wang D, Vozhilla N, Park ES, Chatman L, Boukerche H, Ramesh R, Inoue S, Chada S, Li R, De Pass AL, Mahasreshti PJ, Dmitriev IP, Curiel DT, Yacoub A, Grant S, Dent P, Senzer N, Nemunaitis JJ, Fisher PB. mda-7/IL-24, novel anticancer cytokine: focus on bystander antitumor, radiosensitization and antiangiogenic properties and overview of the phase I clinical experience (Review) Int J Oncol. 2007;31:985–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sauane M, Gopalkrishnan RV, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Lebedeva IV, Dent P, Pestka S, Fisher PB. MDA-7/IL-24: novel cancer growth suppressing and apoptosis inducing cytokine. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:35–51. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian W, Liu J, Tong Y, Yan S, Yang C, Yang M, Liu X. Enhanced antitumor activity by a selective conditionally replicating adenovirus combining with MDA-7/interleukin-24 for B-lymphoblastic leukemia via induction of apoptosis. Leukemia. 2008;22:361–369. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang KJ, Wang YG, Cao X, Zhong SY, Wei RC, Wu YM, Yue XT, Li GC, Liu XY. Potent antitumor effect of interleukin-24 gene in the survivin promoter and retinoblastoma double-regulated oncolytic adenovirus. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:818–830. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan JK, Wei N, Ding M, Gu JF, Liu XR, Li BH, Qi R, Huang WD, Li YH, Xiong XQ, Wang J, Li RS, Liu XY. Targeting Gene-ViroTherapy for prostate cancer by DD3-driven oncolytic virus-harboring interleukin-24 gene. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:707–717. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao L, Dong A, Gu J, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Wang Y, He L, Qian C, Qian Q, Liu X. The antitumor activity of TRAIL and IL-24 with replicating oncolytic adenovirus in colorectal cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13:1011–1022. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Q, Lou W, Shen J, Ma L, Yang Z, Liu L, Luo J, Qian C. Potent antitumor activity in experimental hepatocellular carcinoma by adenovirus-mediated coexpression of TRAIL and shRNA against COX-2. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:3696–3705. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aghi M, Martuza RL. Oncolytic viral therapies-the clinical experience. Oncogene. 2005;24:7802–7816. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathis JM, Stoff-Khalili MA, Curiel DT. Oncolytic adenoviruses-selective retargeting to tumor cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:7775–7791. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segerman A, Atkinson JP, Marttila M, Dennerquist V, Wadell G, Arnberg N. Adenovirus type 11 uses CD46 as a cellular receptor. J Virol. 2003;77:9183–9191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9183-9191.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong HH, Jiang G, Gangeswaran R, Wang P, Wang J, Yuan M, Wang H, Bhakta V, Muller H, Lemoine NR, Wang Y. Modification of the early gene enhancer-promoter improves the oncolytic potency of adenovirus 11. Mol Ther. 2012;20:306–316. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strasser A, O’Connor L, Dixit VM. Apoptosis signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:217–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X, Liu YH, Zhang YP, Zhang S, Pu X, Gardner TA, Jeng MH, Kao C. Fas ligand delivery by a prostate-restricted replicative adenovirus enhances safety and antitumor efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5463–5473. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]