Abstract

Developments in nanomedicine are expected to provide solutions to many of modern medicine’s unsolved problems, so it is no surprise that literature is flush with articles discussing the subject. However, existing reviews tend to focus on specific sectors of nanomedicine or take a very forward looking stance and fail to provide a complete perspective on the current landscape. This article provides a more comprehensive and contemporary inventory of nanomedicine products. A keyword search of literature, clinical trial registries, and the Web, yielded 247 nanomedicine products that are approved or in various stages of clinical study. Specific information on each was gathered, so the overall field could be described based on various dimensions, including: FDA classification, approval status, nanoscale size, treated condition, nanostructure, and others. In addition to documenting the large number of nanomedicine products already in human use, this study indentifies some interesting trends forecasting the future of nanomedicine.

Keywords: Nanomedicine, Biomedical Nanotechnology, Clinical Trials, Human Subjects Research

Background

Nanotechnology will significantly benefit society, producing major advances in energy, including economic solar cells [1] and high-performance batteries [2]; electronics, with ultrahigh density data storage [3] and single-atom transistors [4]; and food and agriculture, offering smart delivery of nutrients and increased screening for contaminants [5]. However, one of the most exciting and promising domains for advancement is health and medicine. Nanotechnology offers potential developments in pharmaceuticals [6], medical imaging and diagnosis [7,8], cancer treatment [9], implantable materials [10], tissue regeneration [11], and even multifunctional platforms combining several of these modes of action into packages a fraction the size of a cell [12,13]. Although there have been articles describing the expected benefits of nanotechnology in medicine, there has been less effort placed on providing a comprehensive picture of its present-day status and how this will guide the future trajectory. Wagner et al. summarized the findings of a 2005 study commissioned by the European Science and Technology Observatory (ETSO) [14,15], including a list of approved products and data on developing applications and the companies involved, but with more emphasis on the economic potential than trends in the technology. A number of articles have analyzed specific sectors of nanomedicine, including: liposomes [16,17], nanoparticles for drug delivery [18,19], emulsions [20], imaging [21], biomaterials [22,23], and in vitro diagnostics [24], but such focused discussions do not provide insight into the overall trajectory of nanomaterials in medicine. Industry market reports describing companies and their products related to nanomedicine and nanobiotechnology have also begun to emerge in the last several years [25,26], but this information is difficult to access for the average researcher or engineer, due to the high subscription costs. The objective of this review is then to fill an important gap in literature by analyzing the current nanomedicine landscape (commercialized and investigational nanomedicine products) on a number of important dimensions to identify the emerging trends. This original approach provides a solid groundwork for anticipating the next phases of nanomedicine development, highlighting valuable perspectives relevant to the field.

Scope of Analysis

The core definitions of nanotechnology and nanomedicine continue to be an area of controversy, with no universally accepted classification. Because an operational definition is required for the purposes of this study, nanomedicine is taken as the use of nanoscale or nanostructured materials in medicine, engineered to have unique medical effects based on their structure, including structures with at least one characteristic dimension up to 300nm. Nanomedicine takes advantage of two general phenomena that occur at the nanoscale- transitions in physiochemical properties and transitions in physiological interactions. Many of the early definitions of nanotechnology employ a cut-off around 100nm (including that of the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI) [27]), focusing on the former, where quantum effects are often restricted to structures on the order of ones to tens of nanometers [28,29]. However, unique physiochemical behavior sometimes emerges for nanomaterials with defining features greater than 100nm (e.g., the plasmon-resonance in 150nm diameter gold nanoshells that are currently under clinical investigation for cancer thermal therapy [30]). In addition, many of the benefits (and risks) of nanomedicine are related to the unique physiological interactions that appear in the transition between the molecular and microscopic scales. At the systemic level, drug bioavailability is increased due to the high relative surface area of nanoparticles [31] and it has been shown that liposomes around 150–200nm in diameter remain in the bloodstream longer than those with diameters less than 70nm [32]. At the tissue level, many nanomedicine products attempt to passively target sites through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, with feature sizes typically in the 100nm to 200nm range, but particles up to 400nm have demonstrated extravasation and accumulation in tumors [33] (although this is an extreme case). At the cellular level, nanoparticle uptake and processing pathways depend on many properties [34], but size is a critical factor. While optimal cellular uptake for colloidal gold has been shown for sizes of around 50nm [35], macrophages can easily phagocytose polystyrene beads up to 200nm in diameter [36]. So, although much of nanomedicine utilizes feature sizes at or below 100nm, this cut-off excludes many applications with significant consequence to the field. Thus we chose 300nm to better encompass the unique physiological behavior that is occurring on these scales. It should also be noted that all this behavior is highly material- and geometry-specific, with much of the previous discussion focusing on spherical nanoparticles, as they are the most prominent in literature. However, many newly developing particles utilize high aspect ratios or nanoscale features on microscale platforms to enhance vascular extravasation [37] and should still fall under the purview of our definition.

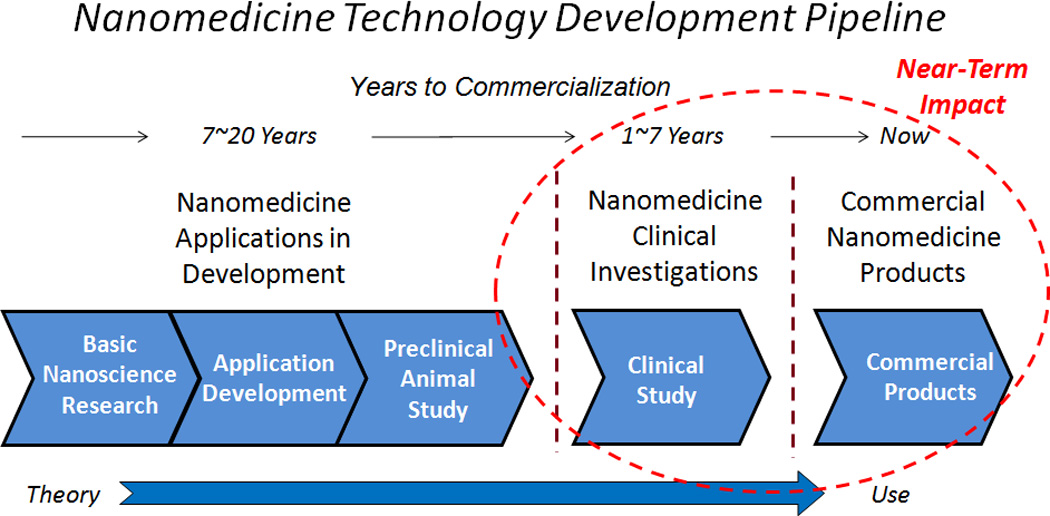

An application will generally move through 5 developmental phases, from basic science to a commercialized medical product (Figure 1). In order to depict and analyze the nanomedicine landscape, we focused on identifying applications that are undergoing or on the verge of clinical investigation in human participants, as well as products already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or foreign equivalent. This excludes applications that are earlier in the pipeline, such as those in bench science or early animal testing. Many of the revolutionary nanomedicine technologies anticipated in literature may be twenty or more years from clinical use. It is difficult to speculate about the forms in which these may finally be implemented and the ultimate impact they may have. For instance, in a 2006 survey, academic, government, and industry experts did not expect to see nanomachines capable of theranostics (combined therapy and diagnostics) in human beings until 2025 [38]. Our study thus focuses on applications and products that are already being tested or used in humans. These applications and products will have the most significant impact on industry, regulation, and society for the foreseeable future.

Figure 1.

Five general stages of nanomedicine development. This study focuses on the applications and products approved and under clinical investigation because they will have the highest impact on the direction of nanomedicine over the foreseeable future.

Methods

We used a structured sequence of Internet searches to identify nanomedicine applications and products. Targeted searches on PubMed.gov, Google and Google Scholar, and a number of clinical trial registries produced a range of resources, including: journal articles, consumer websites, commercial websites, clinical trial summaries, manufacturer documents, conference proceedings, and patents. All of these were used to identify potential nanomedicine applications and products. Information was gathered on each of the identified applications and products through additional searches and the results were recorded and sorted in several Microsoft Excel databases. All searches were performed by Michael Etheridge under the supervision of Jeff McCullough, with input and feedback from Susan Wolf and the full project working group funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) (#1-RC1-HG005338-01).

To offer a more detailed description of the search methodology and classification process, initial searches were conducted through web-based search engines including PubMed.gov, Google, and Google Scholar. The initial searches and filtering were conducted in January through March of 2010, then rerun in May of 2011 to capture any new material published in the interim. The search terms used were: “nanomedicine AND product(s),” “nanomedicine AND commercial,” “nanobiotechnology AND product(s),” “nanobiotechnology AND commercial,” “nanotechnology AND product(s),” “nanotechnology AND commercial,” “nano AND product(s),” and “nano AND commercial.” We filtered the results to capture lists, tables, and databases cataloging nanotechnology applications and products related to medicine (generally identified as “nanomedicine,” “nanobiotechnology,” or “medical nanotechnology”). These lists, tables, and databases appeared in review articles that detailed applications in a specific sector of nanomedicine and public service websites that cataloged nanotechnology products for consumer awareness (such as The Project for Emerging Nanotechnologies [39]). No significant filtering of the applications and products themselves was performed at this point; all applications and products identified as nanotechnology related to medicine were recorded for further analysis.

We conducted additional searches through web-based clinical trial registries. ClinicalTrials.gov was the main focus of our research efforts, but the results were supplemented with reviews of: Biomedical Research Alliance of New York (http://www.brany.com/), Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled-trials.com), Forest Laboratories (www.frx.com), International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (www.ifpma.org), Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (www.oicr.on.ca), Stroke Trials (www.strokecenter.org/trials/), and the World Health Organization (www.who.int/trialsearch/). Nine other clinical trial registries were considered, but were not used due to redundancy with ClinicalTrials.gov or the impracticality of searching their databases. The initial searches in the clinical trial registries were conducted in March of 2010, then rerun in May of 2011 to capture any new clinical trials posted in the interim. A comprehensive list of 44 nanomedicine-related search terms was developed and used as the basis for keyword searches in the registries (Table 1). The search terms fell into two categories: general nano terminology (nano, nanotechnology, etc.) and specific nanotechnology platforms (nanoparticle, liposome, emulsion, etc.). The keyword searches resulted in identification of over 1000 distinct clinical trials, which were then reviewed for relevance to nanomedicine. Any information provided (such as sponsor, product name, published literature, etc.), was used to conduct follow-up, Web-based searches (through Google and Google Scholar) to identify the nanomedicine application or product involved.

Table 1.

ClinicalTrials.gov search terms with the number of results.

| Search Terms | Search Results |

|---|---|

| Aerosol OR Nanoaerosol | 159 |

| Colloid OR Colloidal OR Nanocolloid OR Nanocolloidal OR Nanosuspension OR Nanocoll | 142 |

| Dendrimer OR Dendrimeric | 0 |

| Emulsion OR Nanoemulsion | 149 |

| Fleximer | 1 |

| Fullerene | 0 |

| Hydrogel | 113 |

| Hydrosol | 0 |

| Liposome OR Liposomal OR Nanosome OR Nanosomal | 485 |

| Micelle OR Micellar | 10 |

| Nano | 21 |

| Nanobiotechnology | 0 |

| Nanobottle | 0 |

| Nanocapsule OR Nanoencapsulation | 0 |

| Nanoceramic | 0 |

| Nanocoating OR Nanocoated | 0 |

| Nanocomposite | 0 |

| Nanocrystal OR Nanocrystallite OR Nanocrystalline | 10 |

| Nanodiamond | 0 |

| Nanodrug | 0 |

| Nano-Enabled | 0 |

| Nanofiber OR Nanofilament | 0 |

| Nanofilter or Nanomesh | 0 |

| Nanogel | 0 |

| Nanomaterial | 4 |

| Nanomedicine | 0 |

| Nanometer | 3 |

| Nanoparticle OR Nanosphere | 79 |

| Nanopore OR Nanoporous | 1 |

| Nanorod | 0 |

| Nanoscaffold | 0 |

| Nanoscale | 3 |

| Nanosensor | 0 |

| Nanoshell | 0 |

| Nanosilver | 1 |

| Nanostructure | 4 |

| Nanotechnology | 6 |

| Nanotherapeutic | 0 |

| Nanotube | 0 |

| Nanowire | 0 |

| Quantum Dot | 0 |

| Solgel | 0 |

| Superparamagnetic OR Iron Oxide OR SPIO OR USPIO | 66 |

| Virosome | 8 |

Applications and products identified through the above searches were then subjected to an additional round of Web-based searches to add to the information on each application or product. We reviewed manufacturer websites for product information and additional nanomedicine products in their developmental pipeline. We searched Google Scholar for literature containing technical product details. We consulted FDA.gov for approval status, date, and application number. Additional searches were conducted through Google if more information was still needed. We created a database containing the following information (where available/applicable) for each application or product: product name, sponsoring company/institution, FDA classification, treated condition or device application, delivered therapeutic, nanocomponent, nanoscale dimension, approval status, FDA approval date and application number (for approved products), delivery route, and a short application or product description.

Each application or product was then classified using the following 5 graduated categories, to describe the likelihood that the application or product involved nanomedicine (per our definition): Confirmed – a medical application or product with literature reference citing a functional component with dimension at or less than 300nm (i.e., “nanoscale”). Likely – a medical application or product with literature reference suggesting a functional component on the nanoscale (e.g., literature notes that product takes advantage of EPR effect), but specific size information was not available. Potential – medical application or product with a functional component that could be on the nanoscale (e.g., liposomes), but without literature reference providing a strong indication of size. Unlikely – medical application or product with literature reference suggesting potential nanocomponent larger than nanoscale (e.g., multilaminar liposomes), but without specific size information. Questionable – applications and products identified in literature as “nanomedicine” or “nanotechnology,” but without any clear medical relevance or with a size clearly larger than nanoscale.

Results

The targeted search of clinical trial registries yielded 1265 potentially relevant clinical trial results. Duplicate results and trials involving clearly non-nano applications or products were eliminated, leaving 789 clinical trials with potential nanomedicine applications or products. The application or product (application/product name and company) was identified for each of these trials, yielding a total of 141 unique applications and products (many were associated with multiple trials). Thirty-eight of these were already approved products, being investigated for new conditions or being used as active comparators for new products, and the other 103 were new investigational products. The products identified through the clinical trial search were combined with 222 unique applications and products identified through the literature search, resulting in a total of 363 potential nanomedicine applications and products which were the basis for subsequent analyses. This population was then evaluated on various criteria in an attempt to identify representative trends.

Relevance to Nanomedicine and Developmental Phase

Table 2 provides a breakdown of all the applications and products analyzed by their assigned relevance to nanomedicine and investigational phase. Investigational products that are under study for multiple uses are classified based on their latest phase of development. Applications in Phase 0 and Phase IV trials are classified as preclinical and commercial, respectively. A majority of the applications and products identified did demonstrate a high relevance to the nanomedicine definition used; 247 (or 68%) of the applications and products fell into the confirmed or likely categories. Much of the remaining analysis will focus on this subset, since the other applications and products did not demonstrate clear-cut relevance to nanomedicine. In terms of developmental phase, we found a significant number of commercially available products (100 confirmed and likely) and identified a notable drop-off in the number of products beyond Phase II development.

Table 2.

Number of applications and products found, sorted by developmental phase and by relevance to our definition of nanomedicine.

| Investigational | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- Clinical |

Phase I | Phase I/II |

Phase II | Phase II/III |

Phase III |

Total | Commercial | |

| Confirmed | 14 | 29 | 8 | 32 | 3 | 7 | 93 | 54 |

| Likely | 18 | 18 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 6 | 54 | 46 |

| Potential | 10 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 26 | 18 |

| Unlikely | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 7 |

| Questionable | 3 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 24 |

| Terminated /Discontinued | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 14 | 1 |

| Totals: | 47 | 72 | 13 | 54 | 4 | 23 | 213 | 150 |

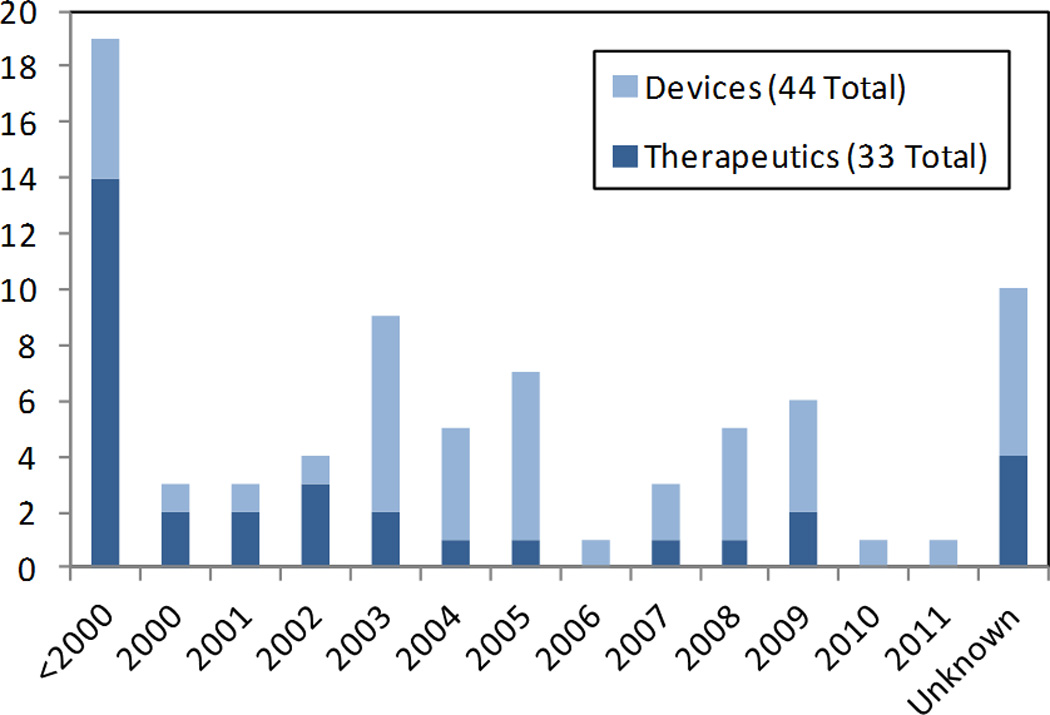

Year of Approval

Our analysis of the year of approval includes only confirmed and likely products that were submitted to the FDA regulatory approval process in the U.S. or a foreign approval process outside the U.S. (i.e., this does not include research-use-only and exempt products) (Figure 2). The analysis uses the FDA approval year if the product is U.S. approved or an equivalent foreign approval year if it is not approved within the U.S. Products with an unknown approval date include foreign products for which a date is not readily available. Most of the products approved before the year 2000 were therapeutics, rather than devices. However, in the last decade, approval for therapeutics appears to have remained fairly steady, while there is a marked increase in the number of medical devices.

Figure 2.

Year of approval for confirmed and likely nanomedicine products identified.

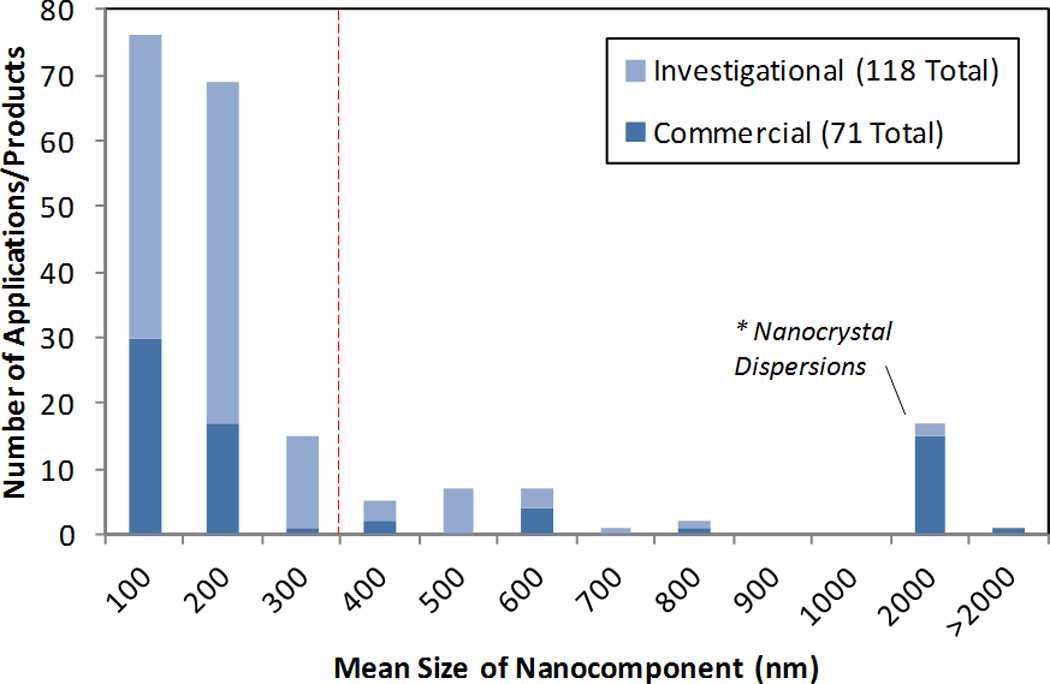

Size of Nanocomponents

Figure 3 shows the mean size of the nanocomponents incorporated in all applications and products for which the information was available. It should be noted that this includes any size information that was available, so the data compare measurements made using a variety of techniques (and in some cases, size data were listed without referencing the measurement technique used). Most applications and products utilize nanocomponents with features at or below 200nm. The peak at 2000nm includes a number of products utilizing “nanocrystal” dispersion technology, in which drug particulate is milled down to increase bioavailability, but the resulting size distribution ranges from tens of nanometers up to 2 microns [40].

Figure 3.

Mean size of nanocomponents for all nanomedicine applications and products for which the data were available. The dotted line indicates the cut-off for this study’s definition of nanomedicine, below which a significant number of the products fall. The notable peak around 2000nm consists of a number of “nanocrystal dispersion” products.

FDA Intervention Type [41]

Of the confirmed and likely nanomedicine products approved for commercial use, 7 fall under the FDA classification for biologics, 38 for devices, and 32 for drugs (Table 3). Of those applications in clinical study, 26 are biologics, 21 are devices, 91 are drugs, 6 are genetic, and 2 are listed as “other.” Thus, the majority of products under clinical study are drugs, but it does appear that nanomedicine biologics are poised to represent a larger segment of the field then they have in the past. Drugs generally include chemically synthesized, therapeutic small molecules, but most nanoparticle imaging contrast applications are also approved under the drug classification. Biologics are sugars, proteins, or nucleic acids or complex combinations of these substances, or may contain living entities such as cells and tissues. Genetic interventions include gene transfer, stem cells, and recombinant DNA. FDA devices provide medical action by means other than pharmacological, metabolic, or immunological pathways. Products listed as “other” interventions included two nanoparticles that were capable of emitting radiation.

Table 3.

FDA intervention class for confirmed and likely nanomedicine applications and products.

| Intervention | Investigational | Commercial |

|---|---|---|

| Biologic | 26 | 7 |

| Device | 21 | 38 |

| Drug | 91 | 32 |

| Genetic | 6 | 0 |

| Other | 2 | 0 |

| Research Use / Exempt | 1 | 23 |

| Totals: | 147 | 100 |

Type of Nanostructure

Table 4 provides a breakdown of the type of nanostructures utilized in the confirmed and likely nanomedicine products. The various forms of free nanoparticles were the most prevalent categories, with significant numbers in both commercial products and investigational applications. However, nanoparticles can also be incorporated into nanocomposites and coatings, and these were classified separately. The high level of development in nanoscale liposomes and emulsions should be highlighted; many developing drug-delivery platforms take advantage of liposomal and emulsion formulations.

Table 4.

Type of nanostructure for confirmed and likely nanomedicine applications and products, by developmental status.

| Nanocomponent | Investigational | Commercial | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic | Device | Total | Therapeutic | Device | Total | |

| Hard Nanoparticle | 3 | 12 | 15 | 0 | 28 | 28 |

| Nanodispersion | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Polymeric Nanoparticle | 23 | 0 | 23 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Protein Nanoparticle | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Liposome | 53 | 0 | 53 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Emulsion | 18 | 1 | 19 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Micelle | 8 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Dendrimer / Fleximer | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Virosome | 6 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Nanocomposite | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 18 |

| Nanoparticle Coating | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Nanoporous Material | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Nanopatterned | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Quantum Dot | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Fullerene | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hydrogel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Carbon Nanotube | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Totals: | 122 | 25 | 147 | 33 | 67 | 100 |

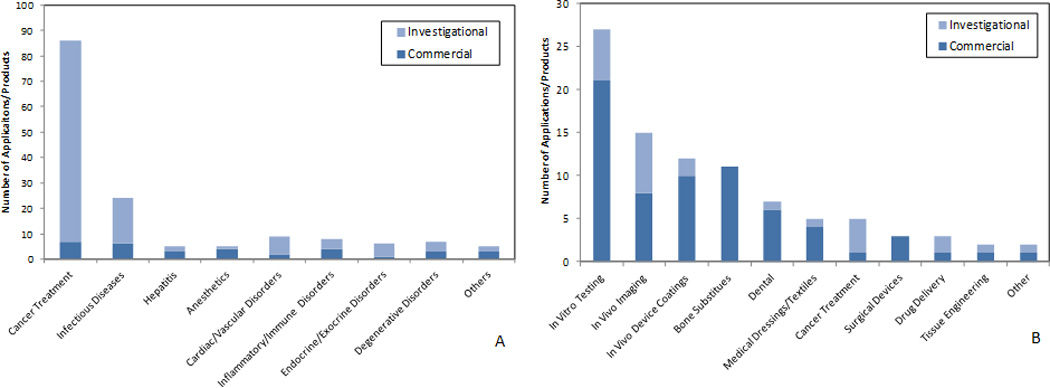

Applications for Therapeutics

“Therapeutics” were generally defined to include drugs, vaccines, and biologics that are intended to directly remedy a medical condition. The uses for each of the confirmed and likely therapeutic products were grouped into nine categories based on the approved or intended use: cancer treatment, hepatitis, (other) infectious diseases, anesthetics, cardiac/vascular disorders, inflammatory/immune disorders, endocrine/exocrine disorders, degenerative disorders, and others (Figure 4). The number of approved products is similar across all the categories. However, about two-thirds of the investigational applications identified are focused on cancer treatment.

Figure 4.

Medical uses for confirmed and likely nanomedicine therapeutics (A) and devices (B) identified.

Applications for Medical Devices

All other applications and products were generally classified as devices and a similar categorization approach was used (Figure 4). The device categories included: in vitro testing, in vivo imaging, in vivo device coatings, bone substitutes, dental, medical dressings/textiles, cancer treatment, surgical devices, drug delivery, tissue engineering, and other. In vitro testing and in vivo imaging were the most prominent categories, followed by in vivo device coatings and bone substitutes. It should also be noted that many fewer investigational devices were found than investigational therapeutics. This may be due to the differences in the nature of the approval processes between drugs and devices; clinical drug data are generated more often than data for devices, which are often approved through alternative approval paths (e.g., the 510k pathway).

Administration and Targeting

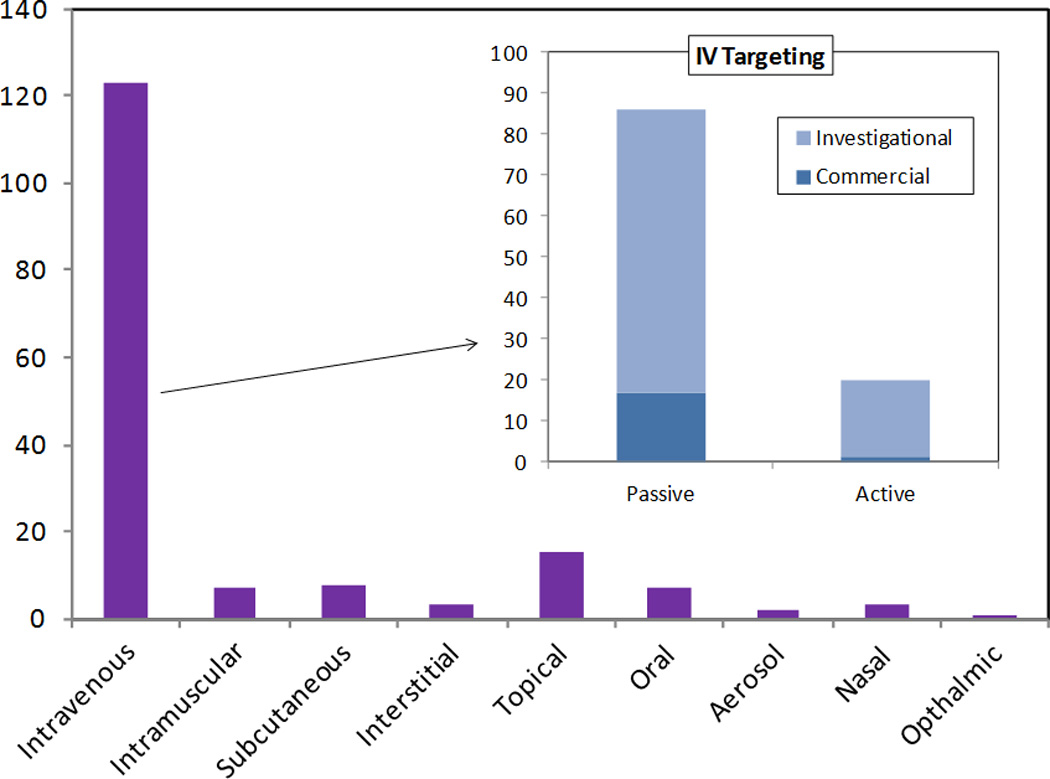

One of the key benefits offered by nanoscale structures in medicine is the ability to achieve unique biodistribution profiles that are not possible with purely molecular or microscale delivery, and well-designed nanosystems offer the possibility to preferentially target specific tissues. One of the important factors in determining the resulting biodistribution profile is the route of administration. The confirmed and likely applications and products identified demonstrated a heavy focus on intravenous (IV) administration (Figure 5). Over 120 (or 73%) of the directly administered applications and products were intended for IV use. Another 15 were intended for topical administration. The remaining products were relatively evenly distributed among intramuscular, subcutaneous, and interstitial injection and oral, aerosol, nasal, and ophthalmic ingestion.

Figure 5.

Route of administration for confirmed and likely nanomedicine applications and products identified, with a description of passive versus active targeting for those utilizing intravenous delivery.

Once a product is administered into the body, the nanoplatform design can take advantage of various mechanisms to affect the subsequent biodistribution and preferentially target a specific tissue. However, the sophistication of targeting varies. As discussed earlier, many delivery platforms are attempting to take advantage of the EPR effect, and this purely size- and geometry-dependent mode of action is generally termed “passive targeting.” However, “active targeting” is another term used frequently in literature and, for the purposes of this study, it is defined as utilizing a mechanism beyond size-dependent biodistribution to enhance preferential delivery to a specific tissue.

Further expanding the analysis in Figure 5, seventeen of the approved products utilized passive targeting and only one took advantage of active targeting. However, there are 69 products under clinical study that capitalize on passive targeting and another 19 that exploit active targeting. All of the actively targeted products are aimed at diagnosing or treating various forms of cancer (Table 5). The dominant targeting mechanism is functionalizing the nanoparticle with ligands (transferrin, antibodies, etc.) for receptors that are overexpressed in the cancer cells or matrix. However, two products take a unique approach, limiting therapeutic activation until the target tissue is reached. Opaxio™ is a polymeric nanoparticle that delivers a form of Paclitaxel and is only activated once enzyme activity specific to the tumor site cleaves the therapeutic molecule [42]. ThermoDox® utilizes a thermosensitive lipid, which will only deliver the Doxorubicin payload when an external heat source is applied. This heat source can be limited to the target site, releasing the drug from the liposomes that were passively delivered [43]. A drug emulsion is also listed which does not strictly fit the definition of active targeting, but is notable as the only application identified which claims the ability to cross the blood-brain-barrier and thus demonstrates a higher level of targeting than the other passive modes of delivery [44].

| Application(s)/Product(s) | Company | Status | Condition | Nanocomponent | Targeting Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontak [45,46] | Seragen, Inc. | Approved (1999) | T-Cell Lymphoma | Protein Nanoparticle | IL-2 Protein |

| MBP-Y003, MBP-Y004, MBP-Y005 [47] | Mebiopharm Co., Ltd | Preclinical | Lymphoma | Liposome | Transferrin |

| MBP-426 [47–49] | Mebiopharm Co., Ltd | Phase I/II | Solid Tumors | Liposome | Transferrin |

| CALAA-01 [19,50] | Calando Pharmaceuticals | Phase I | Solid Tumors | Nanoparticle | Transferrin |

| SGT-53 [19,51] | SynerGene Therapeutics, Inc. | Phase I | Solid Tumors | Liposome | Transferrin |

| MCC-465 [48,52] | Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp | Phase I | Stomach Cancer | Liposome | GAH Antibody |

| Actinium-225-HuM195 [53] | National Cancer Institute | Phase I | Leukemia | Nanoparticle | HuM195 Antibody |

| AS15 [54] | GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals | Phase I/II | Metastatic Breast Cancer | Liposome | dHER2 Antibody |

| PK2 [48,55] | Pharmacia & Upjohn Inc. | Phase I | Liver Cancer | Polymeric Nanoparticle | Galactose |

| Rexin-G, Reximmune-C [56,57] | Epeius Biotechnologies | Phase I/II | Solid Tumors | Nanoparticle | von Willebrand factor (Collagen-Binding) |

| Aurimune (CYT-6091) [19,58] Auritol (CYT-21001) [59] |

CytImmune Sciences, Inc. | Phase II Preclinical | Solid Tumors | Colloid Gold | TNF-α |

| SapC-DOPS[60,61] | Bexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Preclinical | Solid Tumors | Liposome | Saposin C |

| Targeted Emulsions [62,63] | Kereos, Inc. | Preclinical | In Vivo Imaging | Emulsion | "Ligands" |

| Opaxio [42,64] | Cell Therapeutics, Inc. | Phase III | Solid Tumors | Polymeric Nanoparticle | Enzyme-Activated |

| ThermoDox [43] | Celsion Corporation | Phase II/III | Solid Tumors | Liposome | Thermosensitive |

| DM-CHOC-PEN [44,65] | DEKK-TEC, Inc. | Phase I | Brain Neoplasms | Emulsion | Penetrate Blood-Brain-Barrier |

Table 5.

Confirmed and likely nanomedicine applications and products identified, that utilize active targeting.

| Application(s)/Product(s) | Company | Status | Condition | Nanocomponent | Targeting Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontak [85,86] | Seragen, Inc. | Approved (1999) | T-Cell Lymphoma | Protein Nanoparticle | IL-2 Protein |

| MBP-Y003, MBP-Y004, MBP-Y005 [87] | Mebiopharm Co., Ltd | Preclinical | Lymphoma | Liposome | Transferrin |

| MBP-426 [87–89] | Mebiopharm Co., Ltd | Phase I/II | Solid Tumors | Liposome | Transferrin |

| CALAA-01 [19,90] | Calando Pharmaceuticals | Phase I | Solid Tumors | Nanoparticle | Transferrin |

| SGT-53 [19,91] | SynerGene Therapeutics, Inc. | Phase I | Solid Tumors | Liposome | Transferrin |

| MCC-465 [88,92] | Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp | Phase I | Stomach Cancer | Liposome | GAH Antibody |

| Actinium-225-HuM195 [93] | National Cancer Institute | Phase I | Leukemia | Nanoparticle | HuM195 Antibody |

| AS15 [94] | GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals | Phase I/II | Metastatic Breast Cancer | Liposome | dHER2 Antibody |

| PK2 [88,95] | Pharmacia & Upjohn Inc. | Phase I | Liver Cancer | Polymeric Nanoparticle | Galactose |

| Rexin-G, Reximmune-C [96,97] | Epeius Biotechnologies | Phase I/II | Solid Tumors | Nanoparticle | von Willebrand factor (Collagen-Binding) |

| Aurimune (CYT-6091) [19,98] Auritol (CYT-21001) [99] | CytImmune Sciences, Inc. | Phase II Preclinical | Solid Tumors | Colloid Gold | TNF-α |

| SapC-DOPS[100,101] | Bexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Preclinical | Solid Tumors | Liposome | Saposin C |

| Targeted Emulsions [69,102] | Kereos, Inc. | Preclinical | In Vivo Imaging | Emulsion | "Ligands" |

| Opaxio [42,103] | Cell Therapeutics, Inc. | Phase III | Solid Tumors | Polymeric Nanoparticle | Enzyme-Activated |

| ThermoDox [43] | Celsion Corporation | Phase II/III | Solid Tumors | Liposome | Thermosensitive |

| DM-CHOC-PEN [44,104] | DEKK-TEC, Inc. | Phase I | Brain Neoplasms | Emulsion | Penetrate Blood-Brain-Barrier |

Nanomedicine Companies: We found that a total of 241 companies and institutions (universities and medical centers) were associated with the initial 363 products identified. One-hundred and sixty-nine companies and institutions were associated with the confirmed or likely nanomedicine applications and products, with 54 of these companies and institutions developing more than one application or product (ranging between two and ten). This means that over one-third of the development in the field is occurring at companies and institutions with only one nanotechnology-based application or product. It should also be noted that this only includes companies and institutions directly responsible for developing the nanomedicine applications and products. Other reviews and market reports cite larger numbers of “nanomedicine companies,” but these lists often include firms that are investing heavily in nanomedicine development, companies with processes or technology enabling nanomedicine production, and companies developing applications with unrealized or long-term potential in nanomedicine.

Discussion

This study identified a significant number of nanomedicine products approved for or nearing in-human use. It is difficult to extrapolate these numbers directly, because growth in medical industries is so heavily influenced by swings in the economy and regulatory processes. However, we observed some definite trends related to the future of nanomedicine. The most prominent theme throughout is the relative adolescence of the field. Although all the applications identified represent significant technological advancements, they are only scratching the surface of the potential available and it will be the continued refinement and combination of these technologies that will lead to the truly transformative capabilities envisioned for nanomedicine.

One of the major observations in conducting this study is the difficulty in locating basic information on nanomedicine products. This is partly due to the lack of a clear definition and categorization of nanomedicine as a unique product class. But aside from the fundamental question of how to define “nanomedicine,” efforts are being made to better standardize characterization of and information collected on nanomedicine products. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) established the Nanotechnology Characterization Lab (NCL), which has developed a “standardized analytical cascade that tests the preclinical toxicology, pharmacology, and efficacy of nanoparticles and devices” [66]. This battery of tests provides physiochemical, in vitro, and in vivo characterization of nanoplatforms, supplying results in a standard report format, in an attempt to better prepare products for the clinical approval process. The NCL has characterized over 200 nanomaterials from academia, government, and industry using their standardized protocols [67]. In addition, the FDA Office of Pharmaceuticals Science (OPS) recently released a Manual of Policies and Procedures (MAPP 5015.9) document instructing reviewers on gathering information on nanomaterial size, functionality, and other characteristics for use in a developing database. The document also includes a more inclusive definition of “nanoscale” and “nanomedicine” which encompasses any material with at least one dimension smaller than 1,000nm [68], which is intended as a broad net to capture all relevant information in these early stages. These steps demonstrate the type of standardization and information sharing that will be necessary to facilitate coordination in this developing field.

The most overwhelming trend observed in the data is the large number of cancer treatments under development. This can be tied to the significant investments NCI has made in nanotechnology over the past decade [69], the fact that cancer is the worldwide leading cause of death [70], and the inherent benefits that nanoplatforms offer for therapeutic delivery. However, it might also be due in part to the sense that life-threatening cancers warrant the investigation of treatments using emerging technologies such as nanotechnology. Forty-seven percent of all the confirmed and likely in vivo products were intended for acutely life-threatening conditions (mostly advanced cancers). Some uncertainty about risks, especially longer-term risks, may be more tolerable in such cases.

The majority of the cancer treatment applications identified in this study were aimed at increasing the efficacy of therapeutic delivery, but the envisioned impact of nanotechnology in cancer medicine is much more transformative, including the advent of personalized medicine and point-of-care diagnostics. The key to this field is adequate identification and understanding of the biomarkers involved in different disease states. Important developments in nanotechnology over the last decade have provided the tools necessary to probe this understanding [71], while also providing the platforms to implement the improved diagnostics and therapies applying this knowledge. It is this synergistic role of nanotechnology as both driver and vehicle, which has allowed the field to reach a tipping point where accelerated growth is likely.

Another theme playing a major role in today’s nanomedicine which is likely to undergo significant development in the near future is in vivo targeting. A large number of products utilizing the EPR effect were identified, as well as several taking advantage of more active modes of targeting. The value of targeting in nanomedicine has certainly been acknowledged, but there is still much debate around the role and importance of different factors. A lot of work is still needed to characterize the true impact of size, shape, surface chemistry, delivery method, the EPR effect, biomolecular targeting, characteristics of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-coatings, formation of the protein corona, and intracellular targeting, before truly effective delivery can be realized [59,72,73]; but this is and will continue to be a major focus in nanomedicine.

One of the major concerns regarding the use of nanotechnology in the body is the question of persistence. Traditional molecular therapeutics are generally processed by the body and the metabolites are excreted soon after administration, but some nanoparticles have demonstrated persistent in vivo deposits for months or years [74,75]. Examination of the in vivo applications and products identified demonstrates a much higher prevalence of “soft” (157 applications and products) versus “hard” (30 applications and products) nanostructures. The hard nanoparticles identified generally consist of iron-oxide, gold, silver, or ceramic, but several applications nearing clinical study planned to use carbon [76] or hafnium-oxide [77] nanoparticles. “Soft” is a term generally used in contrast to hard material nanoparticles [78] and here is taken to include liposomes, micelles, emulsions, dendrimers, and other polymeric and protein nanostructures. Iron oxide particles are used in MR contrast [79,80] and cancer thermal therapies [75,81]. Colloidal gold is being used in systemic delivery of therapeutic biologics [82] and for cancer thermal therapies [83]. Nanosilver is being used in antimicrobial coatings for several implanted devices and catheters [22,84,85]. Ceramic nanoparticles are used as strength and optical enhancers in a number of dental composites [86]. Although all these materials have demonstrated biocompatibility through current standards, there is some question whether persistence in the body may produce longer-term toxicities not seen with current medicines and treatments. A notable number of bone implant applications also utilized hydroxyapatite [14,62,77,87,88] or calcium phosphate [62,89] nanocrystals (13 applications and products), but these were not included in the hard nanoparticle count because these forms naturally occur in the body [77]. It is likely that both hard and soft nanoparticles will find established roles in the future of nanomedicine. Biodegradable platforms will likely be preferred for therapeutic delivery applications, but most of the unique physiochemical behavior arises only in metallic or semiconductor nanoparticles, so these will be required for future imaging and electromagnetic wave based therapies.

Nanomaterials for tissue regeneration is another highly touted area of development in nanomedicine [71]. However, this study was only able to identify two applications related to tissue regeneration. Both were implantable soft-tissue scaffolds with nanostructured surfaces [39,90]. It is likely that nanomaterials will be critical in developing the surfaces and structures required for ex vivo tissue growth and implantation of engineering tissues, but a better understanding of the adequate conditions and biological signals to trigger growth and proliferation is necessary, before these materials can be properly designed.

As noted in Table 2, fifteen products were identified that were discontinued after approval or during clinical investigation. However, the literature showed no clear reason in common among these cases. One nanocrystal drug formulation was discontinued after being on the market since the 1980’s [91], but there was no indication that this was due to postmarket safety concerns; this formulation was most likely displaced by newer products. Reasons for terminating clinical investigation were fairly evenly distributed among lack of efficacy, systemic toxicity, low enrollment, and licensing or funding issues. However, we found no explanation for terminating study in three cases. In addition, a number of other applications and products were associated with clinical trials that had been terminated, but development continued with adjusted drug formulations or for other indications.

The clinical approval process is structured to ensure that sponsors demonstrate adequate safety and efficacy before a product is released to market. However, the 510k device approval process has recently come under fire as a potential pathway for allowing unsatisfactory products to market [92]. Our study identified a significant number of nanomedicine products that were approved through the 510k process (Table 6), falling into general categories of bone substitutes, dental composites, device coatings, in vitro assays, medical dressings, dialysis filters, and tissue scaffolds. Many of these products have been in use for a number of years without issue. This suggests that safety concerns about the 510k process have not been borne out to date by nanomedicine products. That said, information may become available in the future on potential toxicological risks associated with the use of in vivo nanomaterials and this points to the importance of clearly identifying products that incorporate some form of nanotechnology so they can be adequately tracked.

| Use | Application(s)/Product(s) | Company | Approval Year | Nanocomponent Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Substitute | Vitoss [14] | Orthovita | 2003 | 100 nm Calcium-Phosphate Nanocrystals |

| Ostim [87] | Osartis | 2004 | 20 nm Hydroxapatite Nanocrystals | |

| OsSatura [62] | Isotis Orthobiologics US | 2003 | Hydroxapatite Nanocrystals | |

| NanOss [77] | Angstrom Medica, Inc. | 2005 | Hydroxapatite Nanocrystals | |

| Alpha-bsm, Beta-bsm, Gamma-bsm, EquivaBone, CarriGen [93] | ETEX Corporation | 2009 | Hydroxapatite Nanocrystals | |

| Dental Composite | Ceram × Duo [94] | Dentspley | 2005 | Ceramic Nanoparticles |

| Filtek [95] | 3M Company | 2008 | Silica and Zirconium Nanoparticles | |

| Premise [14] | Sybron Dental Specialties | 2003 | "Nanoparticles" | |

| Nano-Bond [96] | Pentron® Clinical Technologies, LLC | 2007 | "Nanoparticles" | |

| Device Coating | ON-Q SilverSoaker / SilvaGard™ [97] | I-Flow Corporation / AcryMed, Inc. | 2005 | Anti-Microbial Nanosilver |

| EnSeal Laparoscopic Vessel Fusion [39] | Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. | 2005 | Nanoparticle Coated Electrode | |

| NanoTite Implant [98] | Biomet | 2008 | Calcium Phosphate Nanocrystal Coating | |

| In Vitro Assay | CellTracks® [14] | Immunicon Corporation | 2003 | Magnetic Nanoparticles |

| NicAlert [14] | Nymox | 2002 | Colloidal Gold | |

| Stratus CS [62] | Dade Behring | 2003 | Dendrimers | |

| CellSearch® Epithelial Cell Kit [99] | Veridex, LLC (Johnson & Johnson) | 2004 | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | |

| Verigene [100,101] | Nanosphere, Inc. | 2007 | Colloidal Gold | |

| MyCare™ Assays [102] | Saladax Biomedical | 2008 | "Nanoparticles" | |

| Medical Dressing | Acticoat® [97,103] | Smith & Nephew, Inc. | 2005 | Anit-Microbial Nanosilver |

| Dialysis Filter | Fresenius Polysulfone® Helixone® [104] | NephroCare | 1998 | Nanoporous Membrane |

| Tissue Scaffold | TiMESH [39] | GfE Medizintechnik GmbH | 2004 | 30 nm Titanium Coating |

Table 6.

Confirmed and likely nanomedicine products identified, that have been approved by the FDA through the 510k process.

| Use | Application(s)/Product(s) | Company | Approval Year | Nanocomponent Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Substitute | Vitoss [14] | Orthovita | 2003 | 100 nm Calcium-Phosphate Nanocrystals |

| Ostim [68] | Osartis | 2004 | 20 nm Hydroxapatite Nanocrystals | |

| OsSatura [69] | Isotis Orthobiologics US | 2003 | Hydroxapatite Nanocrystals | |

| NanOss [57] | Angstrom Medica, Inc. | 2005 | Hydroxapatite Nanocrystals | |

| Alpha-bsm, Beta-bsm, Gamma-bsm, EquivaBone, CarriGen [95] | ETEX Corporation | 2009 | Hydroxapatite Nanocrystals | |

| Dental Composite | Ceram × Duo [96] | Dentspley | 2005 | Ceramic Nanoparticles |

| Filtek [97] | 3M Company | 2008 | Silica and Zirconium Nanoparticles | |

| Premise [14] | Sybron Dental Specialties | 2003 | "Nanoparticles" | |

| Nano-Bond [98] | Pentron® Clinical Technologies, LLC | 2007 | "Nanoparticles" | |

| Device Coating | ON-Q SilverSoaker / SilvaGard™ [99] | I-Flow Corporation / AcryMed, Inc. | 2005 | Anti-Microbial Nanosilver |

| EnSeal Laparoscopic Vessel Fusion [39] | Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. | 2005 | Nanoparticle Coated Electrode | |

| NanoTite Implant [100] | Biomet | 2008 | Calcium Phosphate Nanocrystal Coating | |

| In Vitro Assay | CellTracks® [14] | Immunicon Corporation | 2003 | Magnetic Nanoparticles |

| NicAlert [14] | Nymox | 2002 | Colloidal Gold | |

| Stratus CS [69] | Dade Behring | 2003 | Dendrimers | |

| CellSearch® Epithelial Cell Kit [101] | Veridex, LLC (Johnson & Johnson) | 2004 | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | |

| Verigene [102,103] | Nanosphere, Inc. | 2007 | Colloidal Gold | |

| MyCare™ Assays [104] | Saladax Biomedical | 2008 | "Nanoparticles" | |

| Medical Dressing | Acticoat® [99,105] | Smith & Nephew, Inc. | 2005 | Anit-Microbial Nanosilver |

| Dialysis Filter | Fresenius Polysulfone® Helixone® [106] | NephroCare | 1998 | Nanoporous Membrane |

| Tissue Scaffold | TiMESH [39] | GfE Medizintechnik GmbH | 2004 | 30 nm Titanium Coating |

Much of the forecasted promise of nanotechnology in medicine takes the form of smart technologies, such as theranostic platforms that can target, diagnose, and administer appropriate treatment to different disease states in the body. However, the current study shows that nanomedicine is still in an early state. As with any emerging field of science, progress is made in steps and some developing applications are just beginning to demonstrate higher levels of sophistication. Active forms of targeting have already been discussed, but active nanomedicine can be more generally defined as nanostructures that induce a mechanism of action beyond purely size-dependent biological and chemical interactions. Table 7 lists the additional active applications and products identified (beyond active targeting) and several of the areas are discussed in more detail below.

| Use | Application(s)/Product(s) | Company | Status | Nanocomponent | Active Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Tumor Hyperthermia | NanoTherm [77] | MagForce Nanotechnologies AG | Approved | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | AC Magnetic Heating |

| Targeted Nano-Therapeutics [105] | Aspen Medisys, LLC. (Formerly Triton BioSystems, Inc.) | Pre-Clinical | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | AC Magnetic Heating | |

| AuroShell [83] | Nanospectra Biosciences | Phase I | Gold Nanoshell | IR Laser Heating | |

| Solid Tumor Treatment | NanoXray [77] | Nanobiotix | Phase I | Proprietary Nanoparticle | X-Ray Induced Electron Emission |

| In Vivo Imaging | Feridex IV, Gastromark Combidex (Ferumoxtran-10) [79,106] | Advanced Magnetics | Approved (1996) Phase III | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Enhanced MRI Contrast |

| Endorem, Lumirem, Sinerem [79,106] | Guebert | Approved / Investigational | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Enhanced MRI Contrast | |

| FeraSpin [107] | Miltenyi Biotec | Research Use Only | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Enhanced MRI Contrast | |

| Clariscan [79] | Nycomed | Phase III | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Enhanced MRI Contrast | |

| Resovist [79,106] Supravist [80] | Schering | Approved (2001) Phase III | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Enhanced MRI Contrast | |

| In Vivo Imaging | Qdot Nanocrystals [108] | Invitrogen Corporation | Research Use Only | Quantum Dot | Fluorescent Emission |

| Nanodots [109] | Nanoco Group PLC | Research Use Only | Quantum Dot | Fluorescent Emission | |

| TriLite™ Nanocrystals [110] | Crystalplex Corporation | Research Use Only | Quantum Dot | Fluorescent Emission | |

| eFluor Nanocrystals [111] | eBiosciences | Research Use Only | Quantum Dot | Fluorescent Emission | |

| NanoHC [112] | DiagNano | Investigational (Research Only) | Quantum Dot | Fluorescent Emission | |

| In Vitro Cell Separation | CellSearch® Epithelial Cell Kit [99] | Veridex, LLC (Johnson & Johnson) | Approved (2004) | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Magnetic Separation |

| NanoDX [113] | T2 Biosystems | Research Use Only | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Magnetic Separation |

Table 7.

Confirmed and likely nanomedicine products identified, which exhibit active behavior, beyond active targeting.

| Use | Application(s)/Product(s) | Company | Status | Nanocomponent | Active Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Tumor Hyperthermia | NanoTherm [57] | MagForce Nanotechnologies AG | Approved | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | AC Magnetic Heating |

| Targeted Nano-Therapeutics [107] | Aspen Medisys, LLC. (Formerly Triton BioSystems, Inc.) | Pre-Clinical | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | AC Magnetic Heating | |

| AuroShell [64] | Nanospectra Biosciences | Phase I | Gold Nanoshell | IR Laser Heating | |

| Solid Tumor Treatment | NanoXray [57] | Nanobiotix | Phase I | Proprietary Nanoparticle | X-Ray Induced Electron Emission |

| In Vivo Imaging | Feridex IV, Gastromark Combidex (Ferumoxtran-10) [80,108] | Advanced Magnetics | Approved (1996) Phase III | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Enhanced MRI Contrast |

| Endorem, Lumirem, Sinerem [80,108] | Guebert | Approved / Investigational | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Enhanced MRI Contrast | |

| FeraSpin [109] | Miltenyi Biotec | Research Use Only | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Enhanced MRI Contrast | |

| Clariscan [59] | Nycomed | Phase III | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Enhanced MRI Contrast | |

| Resovist [80,108] Supravist [60] | Schering | Approved (2001) Phase III | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Enhanced MRI Contrast | |

| In Vitro Imaging | Qdot Nanocrystals [110] | Invitrogen Corporation | Research Use Only | Quantum Dot | Fluorescent Emission |

| Nanodots [111] | Nanoco Group PLC | Research Use Only | Quantum Dot | Fluorescent Emission | |

| TriLite™ Nanocrystals [112] | Crystalplex Corporation | Research Use Only | Quantum Dot | Fluorescent Emission | |

| eFluor Nanocrystals [113] | eBiosciences | Research Use Only | Quantum Dot | Fluorescent Emission | |

| NanoHC [114] | DiagNano | Investigational (Research Only) | Quantum Dot | Fluorescent Emission | |

| In Vitro Cell Separation | CellSearch® Epithelial Cell Kit [101] | Veridex, LLC (Johnson & Johnson) | Approved (2004) | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Magnetic Separation |

| NanoDX [115] | T2 Biosystems | Research Use Only | Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles | Magnetic Separation |

Several forms of electromagnetically activated nanoparticles intended for cancer treatment are currently nearing or progressing through clinical development. NanoTherm® and Targeted Nano-Therapeutics utilize interstitial or intravenous delivery of iron-oxide nanoparticles, which are then heated by an externally applied alternating magnetic field, to provide hyperthermia treatment localized to a tumor [75,81]. AuroShell® uses intravenously injected gold nanoshells, which are heated by a fiberoptic, infrared laser probe to provide high temperatures localized to the tumor area [83]. An additional preclinical nanoparticle platform, NanoXray™, is excited by x-rays, to induce local electron emission in the tumor, leading to free radicals that cause intracellular damage [77,114].

Nanoparticles are also being used to enhance imaging techniques. Five approved applications utilizing iron-oxide nanoparticles for in vivo MRI enhancement were identified, with another four under clinical investigation [79,80]. The iron-oxide nanoparticles passively collect in different tissues and provide enhanced contrast due to localized magnetic effects. Six in vitro applications were also identified, in which quantum dots with biomolecular tagging are used for fluorescent microscopy. However, uncertainty remains as to whether quantum dots in their current form will ever find in vivo use, due to the potential toxicity associated with the heavy metals used [115].

Two other products were identified in which iron-oxide nanoparticles are used for magnetic detection of cells in vitro (CellSearch® and NanoDX™). The magnetic nanoparticles are tagged with cell-specific markers and an external field is used to separate or aggregate the bound cells in solution, allowing detection [113,116]. Similar techniques have been used to enhance drug targeting in animal models [117] and have been proposed for detoxifying circulating blood [118]. One Phase I clinical trial attempted to demonstrate the benefits of magnetic drug targeting in humans in the mid-1990s, but met with limited efficacy [119]. Some companies are pursuing new methods of magnetically enhanced drug delivery and release, but have not yet moved into human trials [120].

The next phases of development in nanomedicine are likely to take advantage of combined applications, in the form of both multimodal treatments (utilizing nanomedicine in combination with current treatments) and theranostic platforms (single nanomedicine applications with multiple modes of action). The MagForce NanoTherm®, magnetically heated iron oxide nanoparticles have already demonstrated synergistic effects in combined treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, allowing lower dosages for each [121]. In addition, Cytimmune’s TNF-α labeled gold nanoparticles have been shown to effect a tissues’ perfusion and increase sensitivity to thermal therapies [122], offering potential preconditioning for a number of applications. Gold nanoparticles have also demonstrated the capability to thermally treat tumors under laser-excitation [83] and are under preclinical study for disease diagnosis through surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy [123]. These current technologies could be combined in an endoscopic application for real-time diagnosis and treatment for many gastrointestinal cancers. As the basic capabilities of nanoparticles are established through single modes of action, it is likely that combined nanomedicine treatments will become more prevalent.

Conclusions

Nanomedicine is a diverse field and this creates some difficulty in creating clear definitions, as well as effective oversight and regulation. A detailed search of the literature, clinical trial data, and Web identified 247 applications and products that were confirmed or likely nanomedicine interventions (under our definition) and which were approved for use, under clinical study, or on the verge of clinical study. The intended uses ranged from the treatment of clinically-unresectable cancers to antibacterial hand gels; and the technologies ranged from liposomes, which have been in pharmaceutical use for decades, to hard nanoparticles, for which limited long-term clinical data are available and questions of persistence in the body have arisen. This study reveals two clear needs that should be addressed in order for any regulatory approach to nanomedicine to succeed: developing an effective and clear definition outlining the field and creating a standardized approach to gathering, sharing, and tracking relevant information on nanomedicine applications and products (without creating additional barriers for medical innovation). Both the NCL and FDA are taking steps in the right direction, but it will take broader reaching efforts to clarify the definition of “nanomedicine,” track key data, and facilitate coordination among agencies in this complex arena.

A categorical analysis of the identified applications and products also provides insight into the future directions of the field. We found a pronounced focus on development of cancer applications. This is a likely a result of a number of factors, including heavy investments made by NCI, the prevalence and impact of cancer in society, and the reality that the risks of many nanomedicine trials may be offset by the benefit sought in treating life-threatening cancers.

Finally, although nanomedicine has already established a substantial presence in today’s markets, this analysis also highlights the infancy of the field. This is not to downplay the advances made to date; engineered, nanoscale materials have already provided medical enhancements that are not possible on the molecular or microscale. However, a large portion of the nanomedicine applications identified are still in the research and development stage. Continued development and combination of these applications should lead to the truly revolutionary advances foreseen in medicine. Now is the time to put in place effective data-gathering strategies and analytical approaches that will advance understanding of this field’s evolution and help to optimize development of nanomedicine and to assure sound approaches to oversight.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of NIH or NHGRI. Thanks to the “Nanodiagnostics and Nanotherapeutics: Building Research Ethics and Oversight” Working Group for valuable input on methodology and analysis.

Research Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) / National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) grant #1-RC1-HG005338-01 (S. M. Wolf, PI; J. McCullough, R. Hall, and J. Kahn, Co-Is), through the University of Minnesota’s Consortium on Law and Values in Health, Environment & the Life Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No conflicts of interest identified.

Contributor Information

Michael L. Etheridge, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Department of Biomedical Engineering.

Stephen A. Campbell, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

Arthur G. Erdman, Department of Mechanical Engineering.

Christy L. Haynes, Department of Chemistry.

Susan M. Wolf, Law School, Medical School, Consortium of Law and Values in Health, Environment & the Life Sciences.

Jeffrey McCullough, Istitute for Engineering in Medicine, Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathology.

References

- 1.Law M, Greene LE, Johnson JC, Saykally R, Yang P. Nanowire dye-sensitized solar cells. Nat Mater. 2005;4(6):455–459. doi: 10.1038/nmat1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan CK, Peng H, Liu G, McIlwrath K, Zhang XF, Huggins RA, Cui Y. High-performance lithium battery anodes using silicon nanowires. Nat Nano. 2008;3(1):31–35. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vettiger P, Cross G, Despont M, Drechsler U, Durig U, Gotsmann B, Haberle W, Lantz M, Rothuizen HE, Stutz R, et al. The ‘millipede’ - nanotechnology entering data storage. IEEE Transactions on nanotechnology. 2002;1(1):39–55. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Franceschi S, Kouwenhoven L. Electronics and the single atom. Nature. 2002;417(6890):701–702. doi: 10.1038/417701a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sozer N, Kokini JL. Nanotechnology and its applications in the food sector. Trends in Biotechnology. 2009;27(2):82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sahoo SK, Labhasetwar V. Nanotech approaches to drug delivery and imaging. Drug Discovery Today. 2003;8(24):1112–1120. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02903-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain KK. Nanotechnology in clinical laboratory diagnostics. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2005;358(1–2):37–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Nanotechnology for Molecular Imaging and Targeted Therapy. Circulation. 2003;107(8):1092–1095. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000059651.17045.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nie S, Xing Y, Kim GJ, Simons JW. Nanotechnology applications in cancer. Biomedical Engineering. 2007;9 doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.152025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H, Webster TJ. Nanomedicine for implants: A review of studies and necessary experimental tools. Biomaterials. 2007;28(2):354–369. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engel E, Michiardi A, Navarro M, Lacroix D, Planell JA. Nanotechnology in regenerative medicine: the materials side. Trends in biotechnology. 2008;26(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasongkla N, Bey E, Ren J, Ai H, Khemtong C, Guthi JS, Chin SF, Sherry AD, Boothman DA, Gao J. Multifunctional polymeric micelles as cancer-targeted, MRI-ultrasensitive drug delivery systems. Nano Lett. 2006;6(11):2427–2430. doi: 10.1021/nl061412u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumer B, Gao J. Theranostic nanomedicine for cancer. Nanomedicine. 2008;3(2):137–140. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner V, Dullaart A, Bock AK, Zweck A. The emerging nanomedicine landscape. Nature Biotechnology. 2006;24(10):1211–1218. doi: 10.1038/nbt1006-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner V, Hüsing B, Gaisser S, Bock AK. Nanomedicine: Drivers for development and possible impacts. JRC-IPTS, EUR. 23494 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamil H. Liposomes: The next generation. Modern drug discovery. 2004;7:36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lasic DD, Papahadjopoulos D. Medical applications of liposomes. Elsevier; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zamboni WC. Concept and Clinical Evaluation of Carrier-Mediated Anticancer Agents. Oncologist. 2008;13(3):248–260. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bawa R. Nanoparticle-based therapeutics in humans: a survey. Nanotechnology Law & Business. 2008;5(2):135–155. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah P, Bhalodia D, Shelat P. Nanoemulsion: A pharmaceutical review. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy. 2010;1(1):24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krestin GP. Superparamagnetic iron oxide contrast agents: physicochemical characteristics and applications in MR imaging. Eur. Radiol. 2001;11:2319ą2331. doi: 10.1007/s003300100908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayman ML, et al. The Emerging Product and Patent Landscape for Nanosilver-Containing Medical Devices. Nanotechnology Law & Business. 2009;148:148–148–158. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong YWH, Yuen CWM, Leung MYS, Ku SKA, Lam HLI. Selected Applications of Nanotechnology in Textiles. AUTEX Research Journal. 2006;6(1) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobson MG, Galvin P, Barton DE. Emerging technologies for point-of-care genetic testing. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2007;7(4):359–370. doi: 10.1586/14737159.7.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.“Nanomedicine - Global Strategic Business Report.”

- 26.“Nanotechnology in Health Care to 2014 - Market Size, Market Share, Market Leaders, Demand Forecast, Sales, Company Profiles, Market Research, Industry Trends and Companies.”

- 27.“NNI What is Nanotechnology.”

- 28.Smith AM, Nie S. Semiconductor Nanocrystals: Structure, Properties, and Band Gap Engineering. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43(2):190–200. doi: 10.1021/ar9001069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daniel M-C, Astruc D. Gold Nanoparticles: Assembly, Supramolecular Chemistry, Quantum-Size-Related Properties, and Applications toward Biology, Catalysis, and Nanotechnology. Chemical Reviews. 2004;104(1):293–346. doi: 10.1021/cr030698+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.“Pilot Study of AuroLase(tm) Therapy in Refractory and/or Recurrent Tumors of the Head and Neck - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov.”

- 31.Van Eerdenbrugh B, Van den Mooter G, Augustijns P. Top-down production of drug nanocrystals: nanosuspension stabilization, miniaturization and transformation into solid products. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2008;364(1):64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Litzinger DC, Buiting AMJ, van Rooijen N, Huang L. Effect of liposome size on the circulation time and intraorgan distribution of amphipathic poly(ethylene glycol)-containing liposomes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1994;1190(1):99–107. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Neal DP, Hirsch LR, Halas NJ, Payne JD, West JL. Photo-thermal tumor ablation in mice using near infrared-absorbing nanoparticles. Cancer letters. 2004;209(2):171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chou LY, Ming K, Chan WC. Strategies for the intracellular delivery of nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1039/c0cs00003e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA, Chan WCW. Determining the Size and Shape Dependence of Gold Nanoparticle Uptake into Mammalian Cells. Nano Letters. 2006;6(4):662–668. doi: 10.1021/nl052396o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clift MJD, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Brown DM, Duffin R, Donaldson K, Proudfoot L, Guy K, Stone V. The impact of different nanoparticle surface chemistry and size on uptake and toxicity in a murine macrophage cell line. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2008;232(3):418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Decuzzi P, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Ferrari M. Intravascular delivery of particulate systems: does geometry really matter? Pharmaceutical research. 2009;26(1):235–243. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9697-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hauptman A, Sharan Y. Envisioned Developments in Nanobiotechnology. Expert Survey. Tel-Aviv. [Google Scholar]

- 39.“Nanotechnology and Medicine / Nanotechnology Medical Applications,” The Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies.

- 40.“Elan Drug Technologies - NanoCrystal® Technology.”

- 41.“FDA Basics.”

- 42.Shaffer SA, Baker-Lee C, Kennedy J, Lai MS, Vries P, Buhler K, Singer JW. In vitro and in vivo metabolism of paclitaxel poliglumex: identification of metabolites and active proteases. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;59(4):537–548. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindner LH. Dual role of hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine) in thermosensitive liposomes: Active ingredient and mediator of drug release. J.Controlled Release. 2008;125(2):112. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morgan LR, Struck RF, Waud WR, LeBlanc B, Rodgers AH, Jursic BS. Carbonate and carbamate derivatives of 4-demethylpenclomedine as novel anticancer agents. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64(4):829–835. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-0933-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faraji AH, Wipf P. Nanoparticles in cellular drug delivery. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 2009;17(8):2950–2962. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanaoka E. A novel and simple type of liposome carrier for recombinant interleukin-2. J.Pharm.Pharmacol. 2001;53(3):295. doi: 10.1211/0022357011775523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Website, “Mebiopharm - Product & Technologies.”

- 48.Matsumura Y, Kataoka K. Preclinical and clinical studies of anticancer agent-incorporating polymer micelles. Cancer science. 2009;100(4):572–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sankhala KK, Mita AC, Adinin R, Wood L, Beeram M, Bullock S, Yamagata N, Matsuno K, Fujisawa T, Phan A. A phase I pharmacokinetic (PK) study of MBP-426, a novel liposome encapsulated oxaliplatin. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:15s. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heidel JD, Yu Z, Liu JY, Rele SM, Liang Y, Zeidan RK, Kornbrust DJ, Davis ME. Administration in non-human primates of escalating intravenous doses of targeted nanoparticles containing ribonucleotide reductase subunit M2 siRNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(14):5715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701458104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Safety Study of Infusion of SGT-53 to Treat Solid Tumors - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov, ClinicalTrials.gov, SynerGene Therapeutics, Inc.

- 52.Hamaguchi T, Matsumura Y, Nakanishi Y, Muro K, Yamada Y, Shimada Y, Shirao K, Niki H, Hosokawa S, Tagawa T, et al. Antitumor effect of MCC-465, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin tagged with newly developed monoclonal antibody GAH, in colorectal cancer xenografts. Cancer science. 2004;95(7):608–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Targeted Atomic Nano-Generators (Actinium-225-Labeled Humanized Anti-CD33 Monoclonal Antibody HuM195) in Patients With Advanced Myeloid Malignancies - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov, ClinicalTrials.gov, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

- 54.Study to Assess dHER2+AS15 Cancer Vaccine Given in Combination With Lapatinib to Patients With Metastatic Breast Cancer - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov, ClinicalTrials.gov, Duke University.

- 55.Seymour LW, Ferry DR, Anderson D, Hesslewood S, Julyan PJ, Poyner R, Doran J, Young AM, Burtles S, Kerr DJ. Hepatic drug targeting: phase I evaluation of polymer-bound doxorubicin. Journal of clinical oncology. 2002;20(6):1668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morse M. Technology evaluation: Rexin-G, Epeius Biotechnologies. Current Opinion in Molecular Therapeutics. 2005;7(2):164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.“Epeius Biotechnologies - Targeting Cancer from the Inside.”

- 58.Paciotti GF, Kingston DG, Tamarkin L. Colloidal gold nanoparticles: a novel nanoparticle platform for developing multifunctional tumor-targeted drug delivery vectors. Drug development research. 2006;67(1):47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dobrovolskaia MA. Immunological properties of engineered nanomaterials. Nature nanotechnology. 2007;2(8):469. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Website, “Welcome to Bexion Pharmaceuticals.”

- 61.Qi X, Chu Z, Mahller YY, Stringer KF, Witte DP, Cripe TP. Cancer-Selective Targeting and Cytotoxicity by Liposomal-Coupled Lysosomal Saposin C Protein. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(18):5840–5851. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roszek B, Jong WH, Geertsma RE. Nanotechnology in medical applications: state-of-the-art in materials and devices. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmieder AH, Winter PM, Caruthers SD, Harris TD, Williams TA, Allen JS, Lacy EK, Zhang H, Scott MJ, Hu G, Robertson JD, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Molecular MR imaging of melanoma angiogenesis with ανβ3-targeted paramagnetic nanoparticles. Magn. Reson. Med. 2005;53(3):621–627. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Debbage P, Jaschke W. Molecular imaging with nanoparticles: giant roles for dwarf actors. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130(5):845–875. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0511-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Study of 4-Demethylcholesteryloxycarbonylpenclomedine (DM-CHOC-PEN) in Patients With Advanced Cancer - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov, ClinicalTrials.gov, DEKK-TEC, Inc.

- 66.“Assay Cascades - Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory.”

- 67.2010, “NIEHS and NCL/NCI Announce Partnership to Study Nanotechnology Safety,” NIEHS Press Release.

- 68.2010, “Reporting Format for Nanotechnology - Related Information in CMC Review.”

- 69.Jain KK. The handbook of nanomedicine. Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 70.“WHO | Cancer.”

- 71.Roco MC, Mirkin CA, Hersam MC. National Science Foundation and World Technology Evaluation Center (WTEC) Berlin, Germany, and Boston, MA: Springer; 2010. Nanotechnology Research Directions for Societal Needs in 2020. www.wtec.org/nano2/Nanotechnology_Research_Directions_to_2020. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang X, Peng X, Wang Y, Wang Y, Shin DM, El-Sayed MA, Nie S. A Reexamination of Active and Passive Tumor Targeting by Using Rod-Shaped Gold Nanocrystals and Covalently Conjugated Peptide Ligands. ACS Nano. 2010;4(10):5887–5896. doi: 10.1021/nn102055s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walkey CD, Chan WCW. Understanding and controlling the interaction of nanomaterials with proteins in a physiological environment. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1039/c1cs15233e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goel R, Shah N, Visaria R, Paciotti GF, Bischof JC. Biodistribution of TNF-alpha-coated gold nanoparticles in an in vivo model system. Nanomedicine. 2009;4(4):401–410. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johannsen M, Thiesen B, Wust P, Jordan A. Magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia for prostate cancer. International Journal of Hyperthermia. 2010;(0):1–6. doi: 10.3109/02656731003745740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mraz S. A new buckyball bounces into town [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gil PR. Nanopharmacy: Inorganic nanoscale devices as vectors and active compounds. Pharmacological research. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nayak S, Lyon LA. Soft nanotechnology with soft nanoparticles. Angewandte chemie international edition. 2005;44(47):7686–7708. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang Y-X, Hussain S, Krestin G. Superparamagnetic iron oxide contrast agents: physicochemical characteristics and applications in MR imaging. European Radiology. 2001;11(11):2319–2331. doi: 10.1007/s003300100908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang X, Bowen C, Gareua P, Rutt B. Quantitative Analysis of SPIO and USPIO Uptake Rate by Macrophages: Effects of Particle Size, Concentration, and Labeling Time. Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 2001;9 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dennis CL, Jackson AJ, Borchers JA, Hoopes PJ, Strawbridge R, Foreman AR, Lierop J, Grüttner C, Ivkov R. Nearly complete regression of tumors via collective behavior of magnetic nanoparticles in hyperthermia. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:395103. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/39/395103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Libutti SK, Paciotti GF, Byrnes AA, Alexander HR, Gannon WE, Walker M, Seidel GD, Yuldasheva N, Tamarkin L. Phase I and Pharmacokinetic Studies of CYT-6091, a Novel PEGylated Colloidal Gold-rhTNF Nanomedicine. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schwartz JA. Feasibility study of particle-assisted laser ablation of brain tumors in orthotopic canine model. Cancer Res. 2009;69(4):1659. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guggenbichler JP. Central Venous Catheter Associated Infections Pathophysiology, Incidence, Clinical Diagnosis, and Prevention-A Review. Materialwissenschaft und Werkstofftechnik. 2003;34(12):1145. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Masse A, Bruno A, Bosetti M, Biasibetti A, Cannas M, Gallinaro P. Prevention of pin track infection in external fixation with silver coated pins: clinical and microbiological results. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2000;53(5):600–604. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200009)53:5<600::aid-jbm21>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jandt KD, Sigusch BW. Future perspectives of resin-based dental materials. Dental Materials. 2009;25(8):1001–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spies CKG. The efficacy of Biobon and Ostim within metaphyseal defects using the Göttinger Minipig. Arch.Orthop.Trauma Surg. 2009;129(7):979. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0705-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rauschmann MA. Nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite and calcium sulphate as biodegradable composite carrier material for local delivery of antibiotics in bone infections. Biomaterials. 2005;26(15):677. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sato M, Sambito MA, Aslani A, Kalkhoran NM, Slamovich EB, Webster TJ. Increased osteoblast functions on undoped and yttrium-doped nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium. Biomaterials. 2006;27(11):2358–2369. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Website, “Nanovis Incorporated.”

- 91.“Drugs@FDA.”

- 92.Zuckerman DM, Brown P, Nissen SE. Medical device recalls and the FDA approval process. Archives of internal medicine. 2011;171(11):1006. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.“ETEX products are composed of a proprietary nanocrystalline calcium phosphate formulation that mimics the crystalline mineral structure of human bone.”