Abstract

Objective

The Chicago south side, even more so than national populations, continues to be burdened with widening gaps of disparities in cancer outcomes. Therefore, Chicago community members were engaged in addressing the following content areas for a cancer disparities curriculum: (1) the south side Chicago community interest in participating in curriculum design, (2) how community members should be involved in designing cancer disparities curriculum, and (3) what community members believe the curriculum should address to positively impact their community.

Methods

Eighty-six community members from 19 different zip code areas of Chicago attended the deliberative session. A survey composed of three quantitative and three short-answer content questions was analyzed.

Results

The majority of participants were from the south side of Chicago (62 %) and females (86 %). Most, 94 %, believed community members should be involved in cancer disparities curriculum development. Moreover, 56 % wanted to be involved in designing the curriculum, and 61 % reported an interest in taking a course in cancer disparities.

Three categorical themes were derived from the qualitative questions: (1) community empowerment through disparities education—“a prescription for change,” (2) student skill development in community engagement and advocacy training, and (3) community expression of shared experiences in cancer health disparities.

Conclusion

The community provided valuable input for cur-ricular content and has an interest in collaborating on cancer disparities curriculum design. Community participation must be galvanized to improve disparities curricular development and delivery to successfully address the challenges of eliminating disparities in health.

Keywords: Community based participatory education, Cancer disparities, Medical education, Curriculum development, Health disparities, Urban health, African American health, Deliberative methods and community members

Introduction

Health disparities in America continue to be a national crisis. A recurrent theme from Healthy People 2010 and 2020 is to eliminate health disparities [1, 2]. In 2014, although some gains have been accomplished, substantial progress has not been achieved, especially in relation to cancer disparities. Gaps in health-care access when comparing black and white populations continue to widen [3], and the disparities in cancer care have become more prominent [4]. While many of the causes and consequences of health and health-care disparities are well known, this knowledge has not translated into significant reductions in disparities in health [5].

Medical institutions and professional organizations have had increasing interest in reducing disparities through curricular innovation [5]. In 2007, the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) outlined curricular guidelines for institutions and organizations interested in disparities curricular design [6]. Similarly, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) formed The Health Disparities Committee to develop programmatic and policy solutions to reduce disparities in cancer care and outcomes [7]. Using these frameworks and others to further advance disparities education, a growing number of medical institutions have integrated disparities education into their curricula. To date, disparities curriculum has been shown to impact students' knowledge, skills, and attitudes toward vulnerable populations [8–12], increase underrepresented minority recruitment to medical school [13], and improve the institutional diversity climate [14]. These findings are significant as minority physicians are more likely to serve minority populations and contribute to the reduction of health disparities [15, 16]. While current curricula commonly incorporate the community voice within curricular dissemination through service projects, few curricula have included community within the curriculum development process.

Traditionally, medical school faculty and medical education experts have worked together to create health disparities curricula [8, 10–12, 17–23]. A small number of institutions have used student need-based assessments to contribute to health disparities curriculum design [17, 19, 20, 24, 25]. Aspects of these curriculum development models are efficacious and impactful. Yet those most impacted by disparities, the minority and underserved communities, have had little input into curriculum development. To date, only a limited number of studies describe community participation in the curriculum development process [5, 12, 21, 24, 26, 27]. Although important, the existing studies do not detail the involvement or curricular contribution of community members and are therefore difficult to reproduce. Furthermore, these studies have utilized a number of proxies for the community including (1) community business leaders, who may have minimal personal experience with disparities [26]; (2) patients, who may have personal experience with disparities but are able to access the health-care system [24]; and (3) community councils, which funnel the community voice through one or two people [5, 12]. Consequently, we cannot be certain that the curriculum we develop to address healthcare disparities in academia truly speaks to the issues most pertaining to the community. The full impact and potential benefit of translating health disparities' knowledge into policy, advocacy, and action may not be achieved without a significant community input into the design and implementation of a curriculum intended to address the needs of the community.

The Chicago south side, even more so than national populations, continues to be burdened with disparities in cancer mortality [3, 28]. The south side of Chicago is one of the nation's largest contiguous urban majority African American communities. Moreover, 7 of the 8 poorest communities in Chicago are found in the south side [29]. Recent data shows a startling increase in the disparities gap for breast cancer mortality between whites and blacks in Chicago [30]. Over the past 20 years, the disparity in breast cancer mortality between African Americans and whites in Chicago has increased to 21 %[28], despite a national decline in breast cancer incidence and mortality [31]. Studies continue to stress the importance of obtaining and using local data to inform community-based initiatives [32–35], as health is ultimately local. To that end, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has called on academia to collaborate with their community in an effort to eliminate disparities [36], as solutions should be guided by a local and regional context. Therefore, the University of Chicago (UC) and Chicago State University (CSU) developed an innovative and timely partnership, the Chicago South Side Cancer Disparities Initiative (CSCDI) to address these growing concerns. To pilot and evaluate curricular models better suited for our institutions' service areas, the CSCDI aimed to explore community interest and potential curricular contributions in designing an innovative cancer disparities curriculum for medical and public health students. The objectives were to determine (1) the south side Chicago community's interest in participating in curriculum design, (2) how community members should be involved in designing a cancer disparities curriculum, and (3) what community members believe the curriculum should address to positively impact their community.

Methods

This was a mixed methods study including quantitative and qualitative inductive content analysis of community responses from a deliberative method approach to understand cancer disparities on Chicago's south side. The deliberative approach provides an informed discussion among parties with different backgrounds, interests, and values [37]. This method not only expands the participants' knowledge and insight on an issue, but it also can increase participants' willingness to participate in the discussion to allow both parties to come to a more reasoned and informed consensus about priorities for research and other community concerns [37, 38]. The University of Chicago exempted this study (IRB-CA165582-01A1).

In 2012, The University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center (UCCCC), a research-intensive academic medical center, and Chicago State University (CSU), a designated minority serving institution with a master's of public health program, were supported through a National Cancer Institute award to build an infrastructure for cancer education, training, and outreach. We felt this was a timely collaboration as the AAMC has noted the importance of building collaborations between academic medicine and public health programs to stimulate and advance health disparities research and community outreach [39]. One aim of this grant was to develop a multi-faceted cancer disparities curriculum for UC medical students and CSU master's of public health students. CSCDI members decided to combine traditional cancer disparities content as outlined by SGIM's curricular guidelines [6] and service learning opportunities within the south side community. To better inform the curriculum development process, deliberative sessions were conducted with community members, students, and faculty during separate sessions to assess both academic and community perspectives. The information from these sessions will be utilized to develop and pilot mini-courses on cancer disparities and eventually the final curriculum. In this manuscript, we describe the community results from the community deliberative approach to understanding interest in cancer disparities on Chicago's south side.

Defining Community Interest in Disparities Curriculum

Using principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR), specifically the recognition of the unique community voice, our study concept was derived directly from a monthly cancer support group in the south side Roseland community. During these informal sessions, community members described their feelings that the medical community did not understand the disparities-related barriers that occur locally. The community demonstrated a real interest in being part of the solution. Therefore, the impetus for this study originated from the community and in collaboration with the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center's Office of Community Engagement and Cancer Disparities (OCECD).

Community Member Engagement

To gain further community input, Chicago's south side community residents were recruited to participate in a deliberative session entitled Emancipation from Health Disparities: a Juneteenth Conversation. The UC and CSU community network list-serves were used to recruit participants. Recruitment was also accomplished through community flyers, word of mouth communication, and local radio announcements. All community members were asked to register for the event online. Those who failed to register were not excluded from participation. No compensation was provided for attending the deliberative session or completing the survey.

Assessing Community Interest in Cancer Disparities

The deliberative session took place at CSU and lasted for 3 h. The session was facilitated by faculty from both UC and CSU and included a presentation from a community member. The goals of the deliberative method were to provide the academic community with a better understanding of the community's attitudes and beliefs about cancer disparities, to expand the community knowledge and awareness about cancer disparities, and to understand the community's interest in cancer disparities curricular development. The authors facilitated the session and presented information on CSCDI, traditional cancer disparities curriculum development, and the local and national cancer disparities landscape. The authors also delivered a brief presentation on the effects of methanol cigarettes within minority populations as a specific example of cancer disparities content with the potential for community engaged policy interventions. After the presentations, community members were encouraged to ask questions and provide comments and suggestions regarding their experiences with disparities. To further engage participants in this discussion, audience response system (ARS) technology was utilized. This technology has been shown to effectively engage minority communities to enhance feedback on cancer disparities and other community issues [40]. ARS technology was used to engage community members in a non-threatening, anonymous way to provide instant feedback and trigger further discussion for the deliberative session.

Survey Instrument

We developed the survey instrument to further investigate common themes that were discussed during feedback sessions with both OCECD and the Roseland cancer support group. In developing the community participatory concept, many community members suggested that they should be involved in both the curriculum design as well as participate in the final curriculum. Based on this input, the authors used open-ended questions to stimulate a broader spectrum of ideas about cancer disparities curriculum.

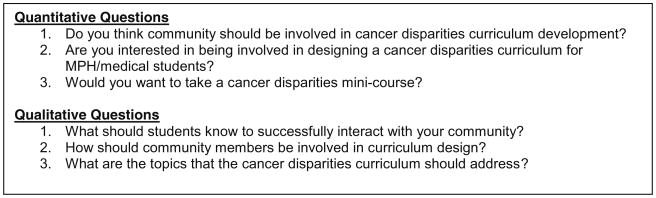

Demographics including age, gender, and zip code were obtained from participants. Zip code data served as a proxy for neighborhood location. We intentionally did not collect education level, reported income, and other socioeconomic factors in order to fully engage the audience in a manner that was not perceived of as intrusive. At the end of the deliberative session, a 1-page survey with both quantitative and qualitative questions was administered to capture additional targeted responses. Three quantitative and three qualitative questions focused on community interest in developing cancer disparities curriculum and taking a mini-course on cancer disparities. The mini-course is a pre-curricular “sneak peek” into potential topics of interest for students and community members and was described during the deliberative session. A sample of the survey is detailed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Questions from deliberative session.

Theme Validation of Content Analysis

Our approach to the qualitative analysis was guided by grounded theory [41]. Content answers from all participants were de-identified and compiled. Seven of the authors (CF, KN, YW, LH, GC, HL, KK) independently reviewed and coded the data for preliminary codes. Individual codes were compared and preliminary themes were discussed and developed during multiple group meetings. After unanimous agreement from all authors, categorical themes for each qualitative question were determined. A summary of all coded themes and developed categories were sent to all authors after the meeting for final review and comment. Qualitative analysis was conducted using MAXQDA trial software.

Results

Community Analysis

Eighty-six community members from at least 19 different Chicago neighborhoods participated in the community forum. The majority of participants were from the south side of Chicago (61.6 %) and female (86.0 %). South side of Chicago is defined as a 95-mile2 region including 34 of Chicago's 77 community areas and is one of the nation's largest contiguous urban African American communities (72 % of 1.1 million people) and was our targeted population for this study. The average age of the participants was 52±17 years.

The survey response rate was 81.9 % (86/105). Most, 94.2 %, of the study participants strongly supported the incorporation of community members in cancer disparities curriculum development (81/83). The majority, 55.8 %, of participants (48/81) were interested in helping with the development of cancer disparities curriculum for UC/CSU health professional students. Further, 60.5 % of the participants were interested in taking part in a mini-course on cancer disparities on the south side of Chicago (52/79). Community response results are further detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Quantitative community response data.

| Question | Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Not sure n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Do you think community should be involved in cancer disparities curriculum development? | 81 (94.2) | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 83 (96.5) |

| 2) Are you interested in being involved in designing a cancer disparities curriculum for MPH/medical students? | 48 (55.8) | 12 (14.0) | 21 (24.4) | 81 (94.2) |

| 3) Would you want to take a cancer disparities mini-course? | 52 (60.5) | 9 (10.5) | 18 (20.9) | 79 (91.9) |

Categorical Themes

Three categorical themes were developed from the content questions posed to the community members.

Theme 1. Community Empowerment Through Disparities Education—“a Prescription for Change”

Chicago community members have a strong desire to develop a deeper understanding of how historical and current events relate to health and cancer disparities. There was a robust response to the information that was presented on menthol use among African Americans. Numerous comments focused on the need to teach students about these issues and to develop mechanisms to address them. One community member stated, “Our community needs a better understanding of health basics and preventative care…and that information should be circulated in supermarkets and churches to effectively reach our community.” Another community member stated, “students and community members should have an understanding of the relationship between one's zip code, health environment, and access to food.” Community members expressed a strong need for a better community education on cancer disparities. Although community members are motivated to change, they expressed feelings of being unaware of what they can do to effect change. They hope to take part in the cancer disparities mini-course alongside students to better bridge the gap between the community impact and curriculum components.

For students to effectively collaborate with community members on these efforts, students need to have an understanding of the community's educational background. One community participant stated, “I think students should be taught that education levels and health literacy levels vary greatly within our community and this should be taken into account when sharing resources and education within our community.” Community members identified student's knowledge and dissemination of resources as one of the most important ways for health professionals to positively impact the health habits for Chicago's minority communities.

Theme 2. Student Skill Development in Community Engagement and Advocacy Training

Community members felt that students would be better suited to work in their community, if their education provided opportunities for positive experiences within the community. Specifically, community members noted, “community and student engagement through service learning” as a necessary component of the cancer disparities curriculum. Community members would like academia to host “focus groups in their community to better identify local issues prior to designing the curriculum.” This process would allow both community members and medical education faculty to gauge knowledge, identify gap areas, and to work together on effectively disseminating this information to students.

More importantly, community members report they would like students to be advocates and champions for shaping policies to reduce disparities. For example, one community member noted, “students should learn how to be an advocate for underserved areas so that quality health care can reach our communities.” In addition, community members themselves want a greater capacity to become advocates and feel that students might bridge this gap. One community member stated, “I wish the students could teach us how to advocate for ourselves, too.” Advocacy training for both student and community members was a recurring theme throughout the community data.

Theme 3. Community Expression of Shared Experiences in Cancer Health Disparities

The most prominent themes were opportunities to express their personal experiences with cancer disparities and survivorship. One community member expressed, “students should seek out community members who have actually experienced the disparities they are learning about… members of the community can provide unique personal stories.” Another community participant stated, “stories of community member survivorship will hopefully empower students.” A number of community members conveyed a strong interest in sharing their experiences with students through personal stories, journaling, and community forums. Survivorship was also a common theme shared throughout the session. The deliberative session was able to unravel the interest that community members have about sharing their personal experiences with students to further develop student empathy and improve their understanding of the unique health challenges faced by south side communities.

Discussion

This study advances the literature on disparities by describing the community's participatory interest in cancer disparities curriculum development. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of the community voice for research [42] and health-care delivery [43]. Yet there continues to be minimal discussion regarding the community's input on education, specifically disparities curriculum. Moreover, minority involvement in such curriculum endeavors has been noted as limited and problematic [44]. Our study demonstrates that the minority community can provide a unique voice and has an interest in collaborating on curriculum design.

The Chicago south side community demonstrated a strong interest in participating in cancer disparities curriculum design. The community provided valuable input for how community member participation can be integrated into curricular design and dissemination. Moreover, south side community members specified particular content for the curriculum, the need for advocacy training and community engagement in order to positively impact their community. For example, community members believed the student curriculum should expand beyond the traditional classroom, and they provided a number of avenues for community involvement in curriculum. Interestingly, we found that the majority of community members also wanted to take the cancer disparities mini-course with students to better understand mechanisms for health-care advocacy and solutions to reduce disparities. By including community in the curriculum development process, we feel that our disparities curriculum will have a greater impact on both the educational experience and community relevance.

There are multiple implications that can be derived from this innovative study. First, community participants were not only willing, but also able to provide significant input for the development of curriculum addressing cancer disparities. This is significant since many studies have shown decreased participation of minorities in clinical trials and research. Our findings clearly suggest that community members are interested and willing to engage in a bidirectional dialogue with university faculty around cancer disparities. Second, community participants expressed significant interest in learning more about cancer disparities. Despite the numerous studies that describe the growth in cancer disparities among the African American community, especially among Chicago south side residents, and the clear evidence that supports cancer prevention, this study is another example of how we (i.e., the health-care system) may have “missed the mark,” in effective dissemination. Empowerment models have shown the positive benefits of including community members in health education [45]. One such benefit is the enhancement of community member's ability and belief to improve their situation [45]. Furthermore, community empowerment has also been linked to positive health outcomes [45]. Thus, the importance of community collaboration with academia to identify issues and solutions is critical [46]. Empowering the community to work with academic institutions to develop an advocacy platform and to engage in the dialogue around disparities solutions, may move knowledge to action and to the eventual reduction of disparities in health and health care. Third, community participants recognize that their personal experiences with disparities are valuable information for students, and they want to share it. Incorporating these personal stories will enhance communication, increase empathy, and help bridge the cultural divide between students and the local communities that they will eventually serve.

Although this study has implications for disparities curriculum development, it also has limitations. First, self-selection of more interested and motivated community participants could have favorably skewed our results. However, since the majority of participants were from the south side, we believe that these community members and their collective experiences are representative of our local minority communities. Second, requesting online registration could have skewed the participant pool to community members with increased access to technology and potentially other resources, though we did not exclude those who did not register for the event. Third, we used a deliberative approach to engage the community that may have provided less rigorous qualitative assessment of community interests. However, we chose this approach to keep our dialogue open ended in order to encourage honest and robust participation.

These findings provide the rationale to develop a conceptual model for community-based participatory education (CBPE). This CBPE model will provide the framework to describe community participation in disparities curriculum development for health professionals in order to maximize the potential for community benefit and effective knowledge transfer to ultimately reduce health disparities. Currently, we are integrating the results from this study into the development of our cancer disparities curriculum. Our future work will not only concentrate on inviting community members to take the cancer disparities course work alongside the students, but also integrating community members into the delivery of our curriculum through journaling and shared experiences.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Chicago south side community members are willing and highly motivated to be active participants in cancer disparities curriculum design. Community members have a strong desire to directly interact with health professional students to share personal experiences with cancer disparities. Lastly, community members would like cancer disparities curriculum to focus on community empowerment and skills in advocacy. Without this important input and collaboration, the true intent of teaching cancer disparities to our students, to provide knowledge that will ensure health equity and the highest quality of care for all, will never be reached.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Chicago Urban Health Initiative, Chicago State University Department of Health Studies, and the Chicago community residents.

Funders National Cancer Institute P-20: Chicago South Side Cancer Disparities Initiative Award (P20-CA165582-01A1).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest C.D.L. Fritz, K. Naylor, Y. Watkins, T. Britt, L. Hinton, G. Curry, H. Lam, and K. Kim declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report.

Informed Consent All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

Contributor Information

Cassandra Fritz, University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Avenue, MC 4076, Chicago, IL 60637, USA.

Keith Naylor, Chicago State University Department of Health Studies, Chicago, USA.

Yashika Watkins, Chicago State University, Chicago, USA.

Thomas Britt, University of Chicago, Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center, Office of Community Engagement and Cancer Disparities, Chicago, USA.

Lisa Hinton, Department of Health Studies and Health Information, Administration, Chicago State University, Chicago, USA.

Gina Curry, Department of Health Studies, Chicago State University, Chicago, USA.

Fornessa Randal, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, USA.

Helen Lam, Department of Health Studies and Health Information, Administration, Chicago State University, Chicago, USA.

Karen Kim, Email: kekim@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu, Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. 2000. pp. 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services and Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orsi JM, Margellos-Anast H, Whitman S. Black-white health disparities in the United States and Chicago: a 15-year progress analysis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):349–56. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed September 2013];2012 National Healthcare Disparities Report. www.ahrq.gov.

- 5.Cené CW, Peek ME, Jacobs E, Horowitz CR. Community-based teaching about health disparities: combining education, scholarship, and community service. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(2):130–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1214-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith W, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, Bussey-Jones J, Stone VE, Phillips CO, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):654–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Society of Clinical Oncology. [Accessed 30 March 2014]; http://www.asco.org/practice-research/health-disparities.

- 8.Vela MB, Kim KK, Tang H, Chin MH. Innovative health care disparities curriculum for incoming medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1028–32. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0584-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang WY, Malinow A. Curriculum and evaluation results of a third-year medical student longitudinal pathway on underserved care. Teach Learn Med. 2010;22:123–30. doi: 10.1080/10401331003656611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang TS, Fantone JC, Bozynski EA, Adams BS. Implementation and evaluation of an undergraduate sociocultural medicine program. Acad Med. 2002;77(6):578–85. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200206000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haq C, Stearns J, Brill J, Crouse B, Foertsch J, Knox K, et al. Training in urban medicine and public health: TRIUMPH. Acad Med. 2013;88:352–63. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182811a75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Florence JA, Goodrow B, Wachs J, Grover S, Olive KE. Rural health professions education at East Tennessee State University: survey of graduates from the first decade of the community partnership program. J Rural Health. 2007;23:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vela MB, Kim KK, Tang H, Chin MH. Improving underrepresented minority medical student recruitment with health disparities curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 2):82–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickins K, Levison D, Smith S, Humphrey HJ. The minority student voice at one medical school: lessons for all. Acad Med. 2013;88:77–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182769513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College of Physicians. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(3):226–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, Vranizan M, Lurie N, Keane D, et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(20):1305–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605163342006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doran KM, Kirley K, Barnosky AR, Williams JC, Cheng JE. Developing a novel poverty in healthcare curriculum for medical students at the University of Michigan Medical School. Acad Med. 2008;83(1):5–13. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31815c6791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross PT, Cene CW, Bussey-Jones J, Brown AF, Brown AF, Blackman D, et al. A strategy for improving health disparities education in medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 2):160–3. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meurer LN, Young SA, Meurer JR, Johnson SL, Gilbert IA, Diehr S. The urban and community health pathway: preparing socially responsive physicians through community-engaged learning. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 Suppl 3):S228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox ED, Koscik RL, Olson CA, Behrmann AT, Hambrecht MA, McIntosh GC, et al. Caring for the underserved: blending service learning and web-based curriculum. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(4):342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelley L, Chou CL, Dibble SL, Robertson PA. A critical intervention in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: knowledge and attitude outcomes among second-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20(3):248–53. doi: 10.1080/10401330802199567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsey PG, Coombs JB, Hunt DD, Marshall SG, Wenrich MD. From concept to culture: the WWAMI program at the University of Washington School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2001;76:765–75. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):782–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hobson WL, Avant-Mier R, Cochella S, Van Hala S, Stanford J, Alder SC, et al. Caring for the underserved: using patient and physician focus groups to inform curriculum development. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5(2):90–5. doi: 10.1367/A04-076R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez CM, Jada Bussey-Jones J. Disparities education: what do students want? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 2):102–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toney M. The long, winding road: one university's quest for minority health care professionals and services. Acad Med. 2012;87:1556–61. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826c97bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acosta D. Using a community-based participatory (CBP) approach to teaching medical students about minority health and health disparities: the CBP curriculum development tool. Hawaii J Med Publ Health. 2013;72(8 Suppl 3):11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margellos H, Abigail S, Whitman S. Comparison of health status indicators in Chicago: are black-white disparities worsening. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):116–21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salem E, Ferguson R. Casting Chicago's safety net: a 12-year review of Chicago's community-based primary care system. Chicago Department of Public Health, Planning and Development Division; Chicago: 2005. [Accessed 15 March 2014]. http://www.cityofchicago.org/dam/city/depts/cdph/policy_planning/PP_Casting.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30. [Accessed March 26, 2014];Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force—2007 report. http://www.chicagobreastcancer.org/site/epage/93666_904.htm.

- 31.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc.; 2009-2010. [Accessed 2 Apr 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon PA, Wold CM, Cousineau MR, Fielding JE. Meeting the data needs of a local health department: the Los Angeles county health survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1950–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howell EM, Pettit KL, Ormond BA, Kingsley GT. Using the national neighborhood indicators partnership to improve public health. J Publ Health Manag Prac. 2003;9(3):235–42. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200305000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah AM, Whitman S, Silva A. Variations in the health conditions of 6 chicago community areas: a case for local-level data. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1485–91. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.052076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fielding JE, Rrieden TR. Local knowledge to enable local action. Am J Prevent Med. 2004;27(2):183–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed 3 May 2014];Addressing racial disparities in health care: a targeted action plan for academic medical centers. 2009 https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Addressing%20Racial%20Disparaties.pdf.

- 37.Abelson J, Forest PG, Eyles J, Smith P, Martin E, Gauvin FP. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(2):239–51. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegel JE, Heeringa JW, Carman KL. Public deliberation in decisions about health research. Am Med Assoc J Ethics. 2013;15(1):56–64. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.1.pfor2-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Association of American Medical Colleges and Association of Schools of Public Health. Cultural competence education for students in medicine and public health: report of an expert panel. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis JL, McGinnis KE, Walsh ML, Williams C, Sneed KB, Baldwin JA, et al. An innovative approach for community engagement: using an audience response system. J Health Disparities Res Pract. 2012;5(2):1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–23. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams RL, Yanoshik K. Can you do a community assessment without talking to the community? J Community Health. 2001;26(4):233–47. doi: 10.1023/a:1010390610335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Towle A, Bainbridge L, Godolphin W, Katz A, Kline C, Lown B, et al. Active patient involvement in the education of health professionals. Med Educ. 2010;44:64–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire's ideas adapted to health education. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):379–94. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Introduction to community empowerment, participatory education, and health. Health Educ Q. 1994;21(2):142–8. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]