A 75 year old female presented to clinic in April, 2013 complaining of bruising to her left breast over the last 3 months. Her past medical history was significant for left breast cancer treated with lumpectomy 8 years prior. Her cancer was stage I, pT1N0 (sn), grade 2, estrogen receptor (ER)/progesterone receptor (PR) positive, HER2 negative, infiltrating ductal carcinoma. The margins of resection were negative and she was treated with adjuvant partial breast radiation via Mammosite and anastrozole, which she stopped after a few weeks due to side effects. She declined any further adjuvant therapy. She was followed with annual clinical exams and mammograms, which were all negative. In January 2013, the patient noted yellow discoloration of her left breast. A mammogram in March 2013 showed architectural distortion central to the nipple suspicious for malignancy with prominent skin thickening (Fig. 1). A biopsy was obtained, which contained an atypical spindle cell proliferation suspicious for angiosarcoma; however, only a two millimeter focus in one of three core fragments contained the lesion. Therefore, she underwent a surgical biopsy. This time pathology confirmed high-grade angiosarcoma. An MRI was also obtained with a representative image shown in Figure 2. Positron Emission Tomography revealed the hypermetabolic left breast mass and there was no evidence of metastases. She was then referred to our center for further management.

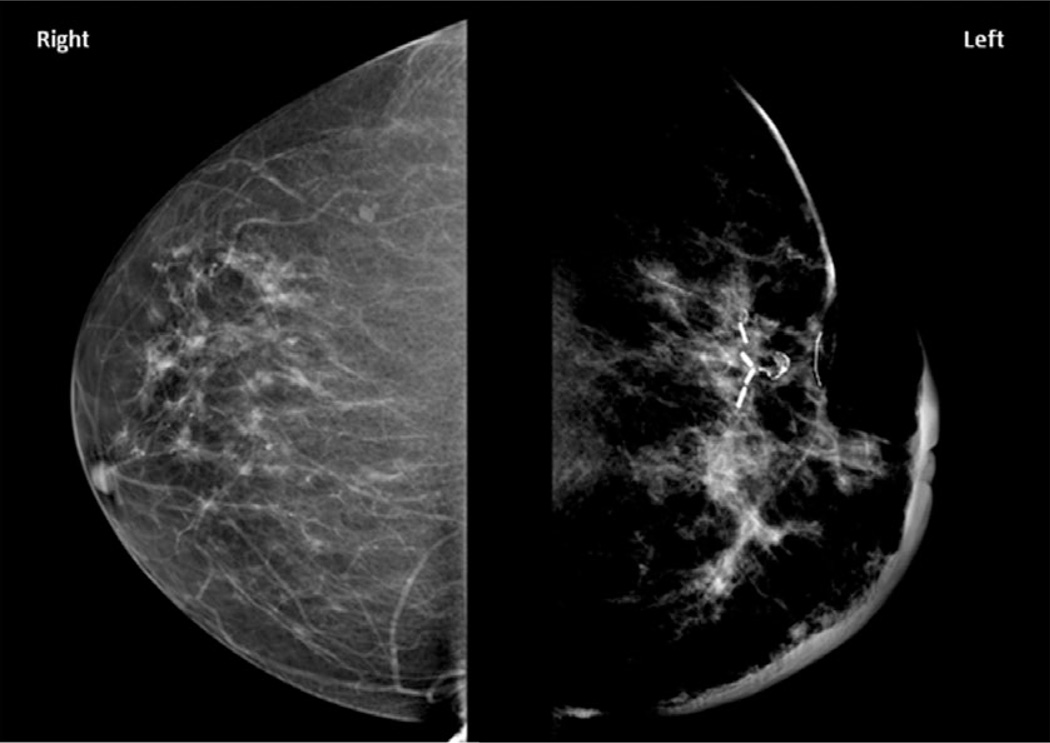

Figure 1.

Mammography, craniocaudal views demonstrating architectural distortion of the left breast with significant skin thickening. Surgical clips from prior lumpectomy are present.

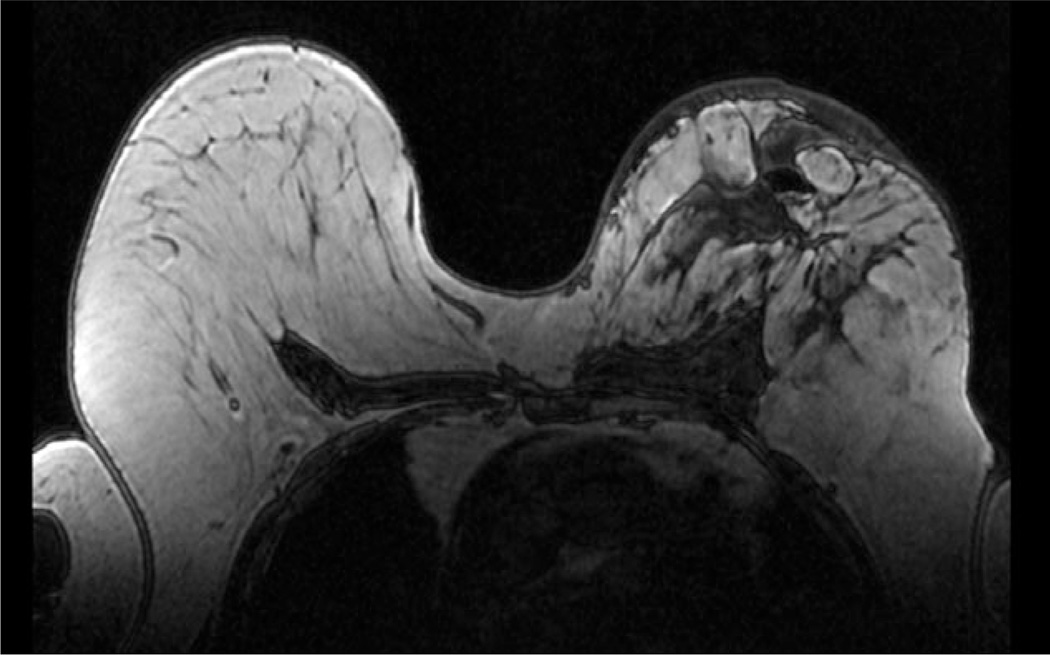

Figure 2.

MRI, T1, Axial image demonstrating loss of normal beast architecture. Skin thickening is again demonstrated.

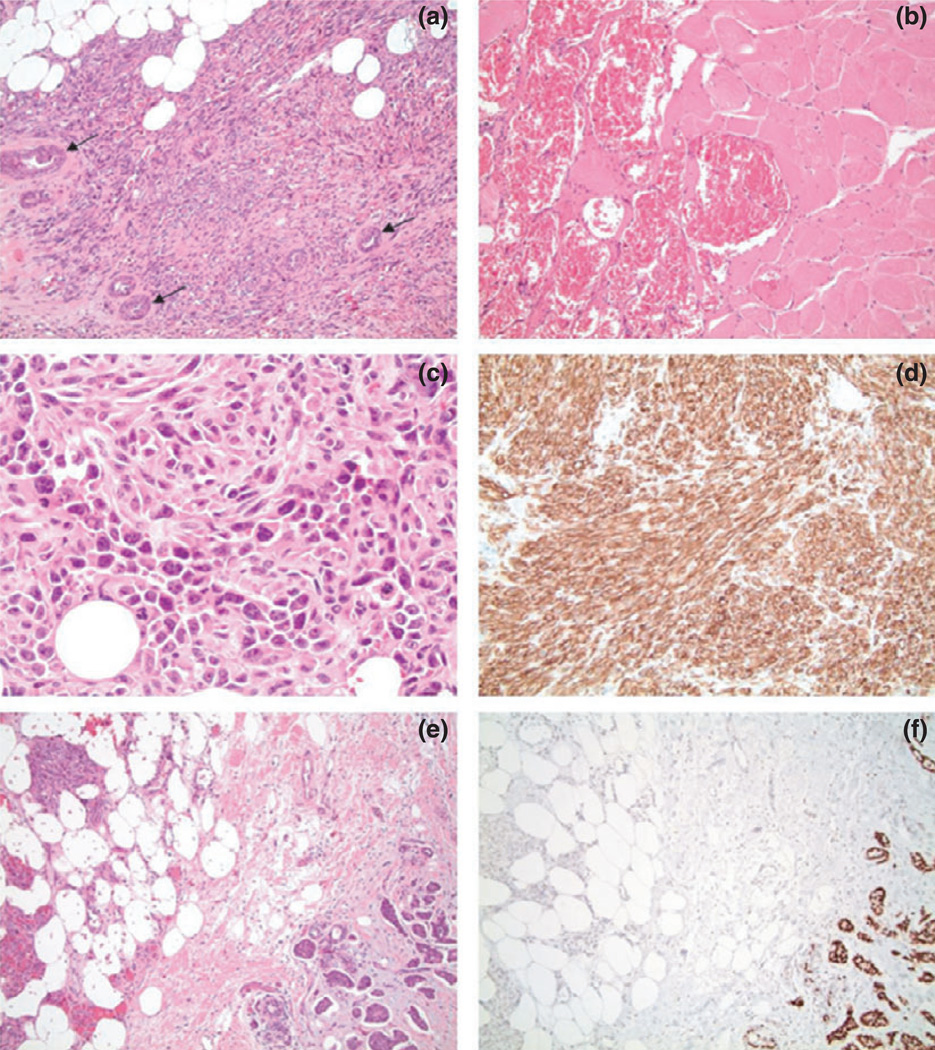

A left mastectomy was performed in May 2013. The pectoralis major appeared to be involved focally; therefore full thickness muscle was included with the surgical specimen in this area (Fig. 3a–c). Pathology from this surgery confirmed high grade angiosarcoma with skeletal muscle invasion (Fig. 3d). In addition, both invasive ductal carcinoma, 0.8 cm, grade 2, ER/PR positive, HER2 negative, and focal ductal carcinoma in situ, cribriform and solid, intermediate nuclear grade were present with invasive carcinoma abutting angiosarcoma (Fig. 3e and f). Surgical margins were negative for both angiosarcoma and carcinoma.

Figure 3.

(a) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stained slides at of the surgical specimen depicting angiosarcoma with residual entrapped breast ducts (arrows) (10× magnification). (b) H&E at revealing large vascular structures filled with blood invading skeletal muscle (20× magnification). (c) H&E of a solid area of the angiosarcoma depicting high-grade features including nuclear atypia and mitotic figures (40× magnification). (d) CD34 immunostain of the angiosarcoma with strong expression, corroborating the diagnosis of angiosarcoma (20× magnification). (e) H&E demonstrating collision of angiosarcoma (left) and infiltrating ductal carcinoma (right) (10× magnification). (f) Estrogen receptor (ER) immunostain corresponding to the H&E in the prior image showing strong nuclear positivity in the infiltrating ductal carcinoma (right) while the angiosarcoma (left) is negative (10× magnification).

Her postoperative course was uncomplicated. She was placed on letrozole and is tolerating this well. She has also undergone external beam radiation at her home institution. Five months postsurgery, she is without complaints. She continues close surveillance of the mastectomy site.

Radiation induced sarcomas constitute one of the most fatal complications of radiation-therapy. Only one other case report describes angiosarcoma following MammoSite brachytherapy. These authors reported a latency of 4 years postcompletion of MammoSite radiation. The sarcoma in this case was located in the skin closest to the MammoSite applicator surface. In the MammoSite registry trial with 1,449 treatments and 4 year follow-up, angiosarcoma was not described. Risk of radiation induced sarcoma is related to dose of radiation received. In general, for Mammosite brachytherapy, the prescription dose is 34 Gy in 10 fractions delivered twice daily at least 6 hours apart over five consecutive working days. This is similar to common treatment plans using accelerated external beam partial breast irradiation of 35–38.5 Gy in 10 fractions, twice a day, over 1 week. This raises the concern that higher radiation dose per fraction may increase late toxicity.

To our knowledge, no other reports of a collision tumor between ductal carcinoma and angiosarcoma exist in the literature. This highlights the need for complete pathologic sampling and a keen clinical suspicion in patients that have received radiation. Although two histologically distinct tumors are rare, this should always be kept on the differential.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report that they have no conflicts of interest to report.