SUMMARY

Mutant p53 (mtp53) is an oncogene that drives cancer cell proliferation. Here we report that mtp53 associates with the promoters of numerous nucleotide metabolism genes (NMG). Mtp53 knockdown reduces NMG expression and substantially depletes nucleotide pools, which attenuates GTP dependent protein (GTPase) activity and cell invasion. Addition of exogenous guanosine or GTP restores the invasiveness of mtp53 knockdown cells, suggesting that mtp53 promotes invasion by increasing GTP. Additionally, mtp53 creates a dependency on the nucleoside salvage pathway enzyme deoxycytidine kinase (dCK) for the maintenance of a proper balance in dNTP pools required for proliferation. These data indicate that mtp53 harboring cells have acquired a synthetic sick or lethal phenotype relationship with the nucleoside salvage pathway. Finally, elevated expression of NMG correlates with mutant p53 status and poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Thus, mtp53’s control of nucleotide biosynthesis has both a driving and sustaining role in cancer development.

INTRODUCTION

Wildtype p53 (WTp53) plays an important role in the control of cellular metabolism, such as glycolysis (negatively regulates Warburg effect), mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation1, 2, 3, 4, 5, glutaminolysis6, 7, lipid metabolism8, 9, antioxidant defense10, 11, 12, 13 and energy homeostasis14. Mutation of the p53 gene can result in the production of a protein with oncogenic capacities, which are generally referred to as gain-of-function activities15. These neomorphic properties of mtp53 include promotion of cell growth, chemotherapy resistance, angiogenesis and metastasis15. Many studies have provided evidence that mtp53 can mediate these pro-oncogenic activities by regulating gene expression15, 16, 17, 18. However, unlike WTp53, mtp53 does not appear to bind to a specific DNA motif directly, rather it can be recruited to gene promoters via protein-protein interactions with other transcription factors. To date, several transcription factors have been shown to tether mtp53 to promoters that contain their respective canonical binding sites17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23.

Compelling evidence suggests that mutant p53 (mtp53) reprograms the metabolic activities of cancer cells in order to sustain proliferation and survival. For example, p53R273H inhibits the expression of phase 2 detoxifying enzymes and promotes survival under high levels of oxidative stress24. Mtp53 disrupts mammary tissue architecture via upregulation of the mevalonate pathway19. Mtp53 has also been demonstrated to stimulate the Warburg effect by increasing glucose uptake25. Mtp53 harboring cancer cells can utilize pyruvate as an energy source in the absence of glucose, thereby promoting survival under metabolic stress26.

Nucleotide metabolism has been reported to be transcriptionally regulated by both oncogenes (e.g. myc) and tumor suppressor genes (e.g. pRb)27, 28, 29,30. Importantly, decreased expression of guanosine monophosphate reductase (GMPR) increases GTP levels, which drives melanoma invasion31. Thus, perturbations in nucleotide metabolism not only impact proliferation but also invasion and metastasis.

In this study, we have observed that knockdown of mtp53 in several human cancer cell lines significantly reduces proliferation. We demonstrate that mtp53 regulates nucleotide pools by transcriptionally upregulating nucleotide biosynthesis pathways, thereby supporting cell proliferation and invasion. Additionally we demonstrate that suppression of one of mtp53’s target genes, GMPS, abrogates the metastatic activity of a breast cancer cell line. Our data reveal that mtp53 utilizes the nucleotide biosynthesis machinery to drive its oncogenic activities.

RESULTS

Knockdown of mtp53 down-regulated nucleotide metabolism genes

Knockdown of endogenous mtp53 in three breast cancer cell lines, HCC38, BT549 and MDAMB231 significantly reduced their proliferation (Fig. 1a). In contrast, WTp53 knockdown had no effect in normal (MCF10a) or cancer derived (MCF7, ZR751, ZR7530) breast epithelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Importantly, introduction of the R249S p53 mutant into MCF10a cells enhanced their proliferative rate (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Since loss of WTp53 function had no effect in these cells, we attributed the accelerated growth rate to the gain-of-function activity of the R249S mtp53. Likewise, introduction of the R175H p53 mutant into H1299 (which lack endogenous p53) accelerated their proliferation rate (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Taken together, the regulation of cell growth by mtp53 is a gain-of-function activity.

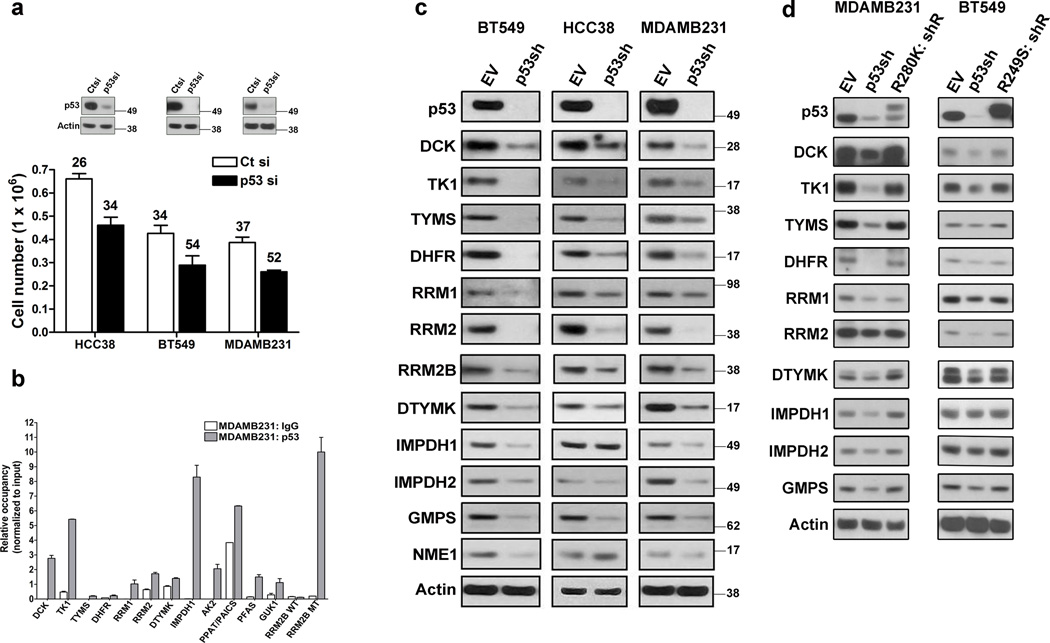

Figure 1. Nucleotide metabolism genes are targets of mtp53.

(a) HCC38, BT549 and MDAMB231 cells were transfected with either a control (Ct) or p53 siRNA (p53si) and cell counts and doubling times were determined after 72 hours. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of three independent replicates. Inset is western blot showing p53 knockdown. (b) Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed on MDAMB231 cells with either a control (IgG) or p53 antibody and real-time PCR was used to detect the presence of the indicated promoter regions. The data was normalized to input DNA. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of two independent replicates. (c) BT549, HCC38 and MDAMB231 cells were infected with an empty vector (EV) or p53 shRNA (p53sh), selected for 3 days and then processed for western blot analysis of the indicated proteins. (d) Rescue experiments were performed by infecting p53 shRNA cells with R280K and R249S expression vectors, selected for 7 days and then processed for western blot analysis of the indicated proteins.

We mined our previously reported mtp53 ChIP-Seq dataset for genes involved in cell proliferation and initially identified deoxcytidine kinase (dCK), an enzyme involved in the nucleoside salvage pathway17. This observation raised the possibility that mtp53 might promote cell proliferation by controlling nucleotide pool levels, thus we analyzed if mtp53 associates with the promoters of other nucleotide metabolism genes (NMG). Strikingly, we observed that several NMG were putative mtp53 targets. Indeed, ChIP analysis on MDAMB231 and MiaPaCa-2 cell lines confirmed the presence of mtp53 on the promoters of these NMG (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1g). Interestingly, our ChIP-seq data also indicated that mtp53 associates with the promoter of RRM2b, a WTp53 target gene32, 33. However, mtp53 associates with the promoter region of RRM2b (referred to as RRM2b MT), and not the intronic WTp53 binding site (referred to as RRM2B WT) located approximately 1.5 kilobases downstream (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1g,j).

shRNA knockdown of mtp53 in BT549, HCC38 and MDAMB231 cells resulted in decreased expression of multiple NMG at both the mRNA and protein level (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1c,d,e). Similarly, mtp53 knockdown reduced NMG expression in the MiaPaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells (Supplementary Fig.1h,i). Transient knockdown of mtp53 with a different siRNA also reduced NMG expression (Fig. 2a). Of note, these cell lines carry different p53 mutations (BT549: R249S, HCC38: R273L, MDAMB231: R280K, MiaPaCa-2: R248W) indicating that NMG are common transcriptional targets of different p53 mutants.

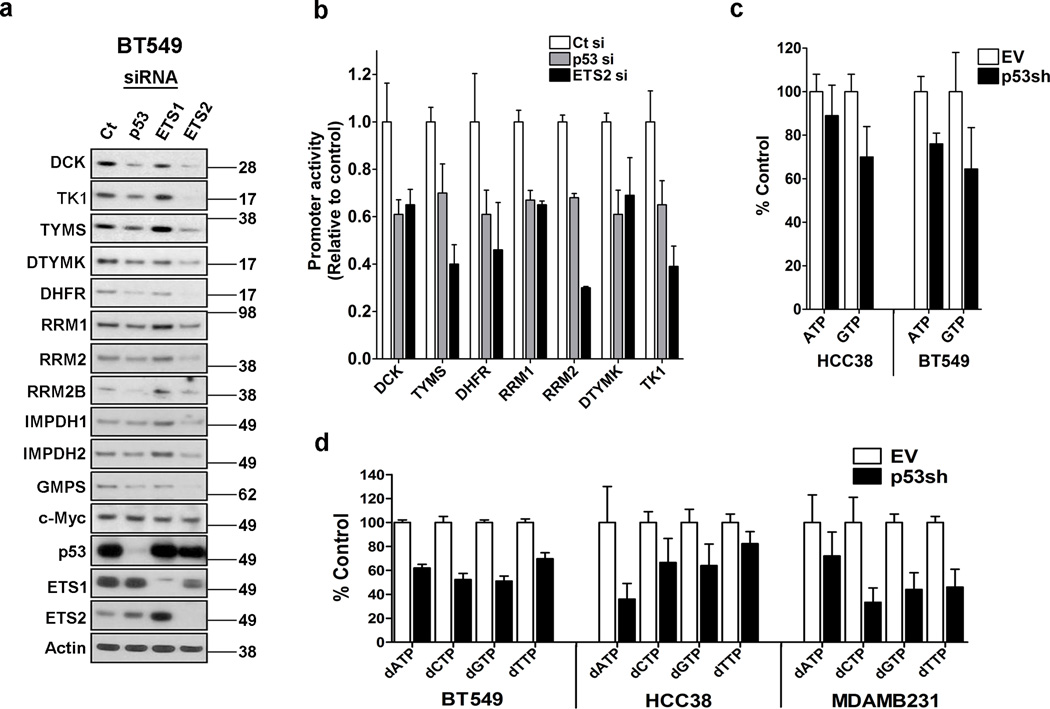

Figure 2. Mtp53 and ETS2 control nucleotide metabolism gene expression.

(a) BT549 cells were transfected with either a control (Ct), p53 siRNA (p53si), ETS1 siRNA (ETS1si), or ETS2 siRNA (ETS2si) and harvested for western blot detection of the indicated proteins. (b) Promoter luciferase constructs of the indicated nucleotide metabolism genes were transfected with either a control (Ct), p53 (p53si) or ETS2 (ETS2si) siRNA into MiaPaca-2 cells. Two days after transfection, the cells were processed to determine luciferase activity. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of two independent replicates each having 6 technical replicates. (c) HCC38 and BT549 cells were infected with an empty vector (EV) or p53shRNA vector (p53sh), selected for 3 days and then processed to detect purine rNTP levels. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of three independent replicates. (d) HCC38, BT549 and MDAMB231 cells were infected with an empty vector (EV) or p53 shRNA vector (p53sh), selected for 3 days and then processed to detect dNTP levels. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of three independent replicates.

shRNA resistant mtp53 restored NMG expression in MDAMB231 or BT549 cells in which endogenous mtp53 had been depleted by shRNA (Fig. 1d). Furthermore, introduction of either the R249S or R175H mtp53 cDNAs into the MCF10a or H1299 cells upregulated NMG expression (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Additionally, we observed that despite the fact that serum starvation of HCC38 cells arrested them in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, this minimally affected NMG expression (Supplementary Fig. 1k). Likewise, serum starved H1299 cells carrying the R273H mtp53 had higher NMG expression relative to empty vector control cells (Supplementary Fig. 1k). Lastly, serum starvation of the WTp53 containing ZR751 cells resulted in decreased expression of the NMG (Supplementary Fig. 1l). These data indicate that the reduction in NMG expression upon mtp53 knockdown is a direct consequence of loss of its gain-of-function activity, rather than a secondary effect resulting from reduced proliferation.

Mtp53 cooperates with ETS2 to activate NMG

Previously we reported that the ETS family member ETS2 recruits mtp53 to promoters containing ETS binding sites (GGAAG)17. NMG have ETS binding sites in their promoters, raising the possibility that mtp53 regulates their expression in a similar manner. We transfected cells with either a control, p53, ETS1 or ETS2 siRNA and examined NMG expression. Both p53 and ETS2, but not ETS1, significantly down regulated 11 of the NMG that we screened (Fig. 2a). To further substantiate that mtp53 and ETS2 transcriptionally regulate NMG expression, we cloned 7 of their promoters into luciferase constructs and assessed their response to mtp53 or ETS2 knockdown. Mtp53 or ETS2 knockdown reduced the activity of the promoters from 40–70%, depending on the promoter (Fig. 2b). These results support the notion that mtp53 and ETS2 cooperatively regulate NMG expression.

We have reported that both structural (R175H) and DNA binding p53 (R248W) mutants interact with ETS2, and thus we speculated that ETS2 also interacts with the mtp53 proteins in the breast cancer cells (i.e. R273L, R249S and R280K). Immunoprecipitation of endogenous mtp53 confirmed that ETS2 interacts with the different p53 mutants (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Furthermore, siRNA knockdown of ETS2 in either the R249S expressing MCF10a or the R175H expressing H1299 cells resulted in reduced NMG expression (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Taken together, our results support a role for ETS2 as a common mediator of the transcriptional regulatory activity of diverse p53 mutants.

mtp53 knockdown reduces rNTP and dNTP pools

Next, we assessed if mtp53 knockdown affected rNTP and dNTP pools. Knockdown of mtp53 reduced ATP by 11% in HCC38 and by 24% in BT549 (Fig. 2c). The decrease in GTP was more pronounced in both cell lines, with mtp53 knockdown reducing this purine rNTP by 30% in HCC38 and 35% in BT549 (Fig. 2c). Our assay did not permit us to detect the levels of the pyrimidine rNTPs.

Mtp53 knockdown significantly reduced both purine and pyrimidine dNTP pools in BT549, HCC38 and MDAMB231 (Fig. 2d). The degree of changes in the dNTP levels varied, with the BT549 and MDAMB231 cells exhibiting a dramatic decrease of all nucleotides. A similar pattern resulted in HCC38 cell line except the decrease in dTTP was more modest. Therefore, these data reveal that the transcriptional control of the NMG by mtp53 is sufficient to impact the rNTP and dNTP pools.

NMG are targets of mtp53 but not WTp53

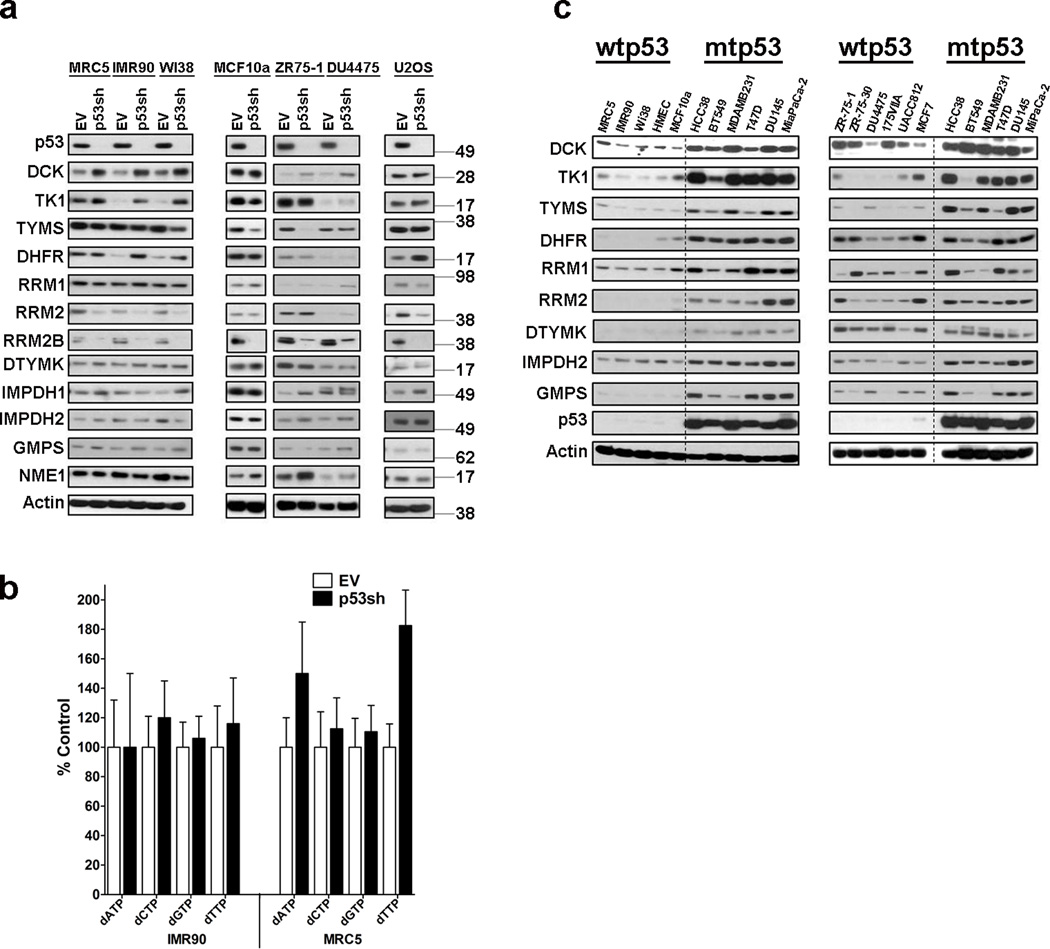

To determine if WTp53 also regulated multiple NMG we knocked it down in three normal, non-immortalized fibroblast strains (MRC5, IMR90 and WI38), a normal mammary epithelial cell line (MCF10a), two breast cancer cell lines (ZR-75-1 and DU4475) and an osteosarcoma cell line (U2OS). Unlike the consistent decrease in NMG expression after mtp53 knockdown, the response to WTp53 knockdown was more varied. We observed a modest induction in dCK, TK1, and DHFR, and also a decrease in RRM2 and TYMS levels (Fig. 3a). Although the changes in protein level did not occur uniformly, overall it appeared that the normal fibroblasts strains had more changes than the immortalized cell lines. ChIP analysis revealed that WTp53 does not occupy the promoter regions of these NMG in either unstressed or doxorubicin treated cultures (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). These data agree with our previous observation that mtp53 and WTp53 binding sites do not overlap17. In contrast, we detected WTp53 association with the previously reported p53 binding site in the RRM2b promoter, but not the one occupied by mtp53 (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). Taken together, mtp53’s interaction with these genomic targets is a gain-of-function activity.

Figure 3. Wildtype p53 knockdown minimally impacts expression of NMG and dNTP Pools.

(a) Analysis of response to WTp53 knockdown in various normal and cancer cell lines. The normal lung fibroblasts strains (MRC5, IMR90 and WI-38), the immortalized noncancerous mammary epithelial cells (MCF10a), the breast cancer cell lines (ZR75-1 and DU4475) and an osteosarcoma cell line (U2OS) were infected with either an empty vector (EV) or p53 shRNA (p53sh), selected and then processed for western blot analysis of indicated proteins. (b) Analysis of dNTP levels in IMR90 and MRC5 cells infected with either empty vector (EV) or p53 shRNA (p53sh). Error bars indicate mean ±SD of three independent replicates. (c) Comparison of nucleotide metabolism gene expression between cells of different p53 genotypes was performed using western blot analysis for indicated proteins. Left panel: normal, non-immortal cell strains (MRC5, IMR-90, WI38, HMEC), immortalized cell line (MCF10a) and mtp53 expressing cell lines (HCC38, BT549, MDAMB231, T47D, DU145, MiaPaCa2). Right panel: WTp53 expressing breast cancer cell lines (ZR-75-1, ZR-75-30, DU4475, MDAMB174VIIA, UACC812, MCF7) and mtp53 expressing cancer cell lines (HCC38, BT549, MDAMB231, T47D, DU145, MiaPaCa-2).

To determine if loss of WTp53 function had an effect on dNTP levels, we assessed the impact of p53 knockdown on dNTPs in the IMR90 and MRC5 cells (Fig. 3b). We observed two distinct responses to WTp53 knockdown in the IMR90 and MRC5 cell strains. In IMR90, p53 knockdown minimally impacted the dNTP pools. In contrast, the MRC5 cells exhibited a 1.8 fold increase in dTTP, a 1.6 fold increase in dATP and essentially no change in dGTP and dCTP levels. We speculated that these divergent responses might be idiosyncratic and thus we assessed if there were any changes in dATP and dTTP levels in the WTp53 containing cell line, U2OS (Supplementary Fig. 3c). WTp53 knockdown in U2OS did not alter these dNTPs, suggesting that the changes observed in the MRC5 cells are not a general response. Thus, we conclude that unlike mtp53, WTp53 does not control steady-state dNTP levels.

Next, we compared protein expression levels of several NMG between cells that have either WTp53 or mtp53. Relative to both the normal and cancer cell lines that carry WTp53, the mtp53 harboring cell lines express higher levels of most of the NMG (Fig. 3c).

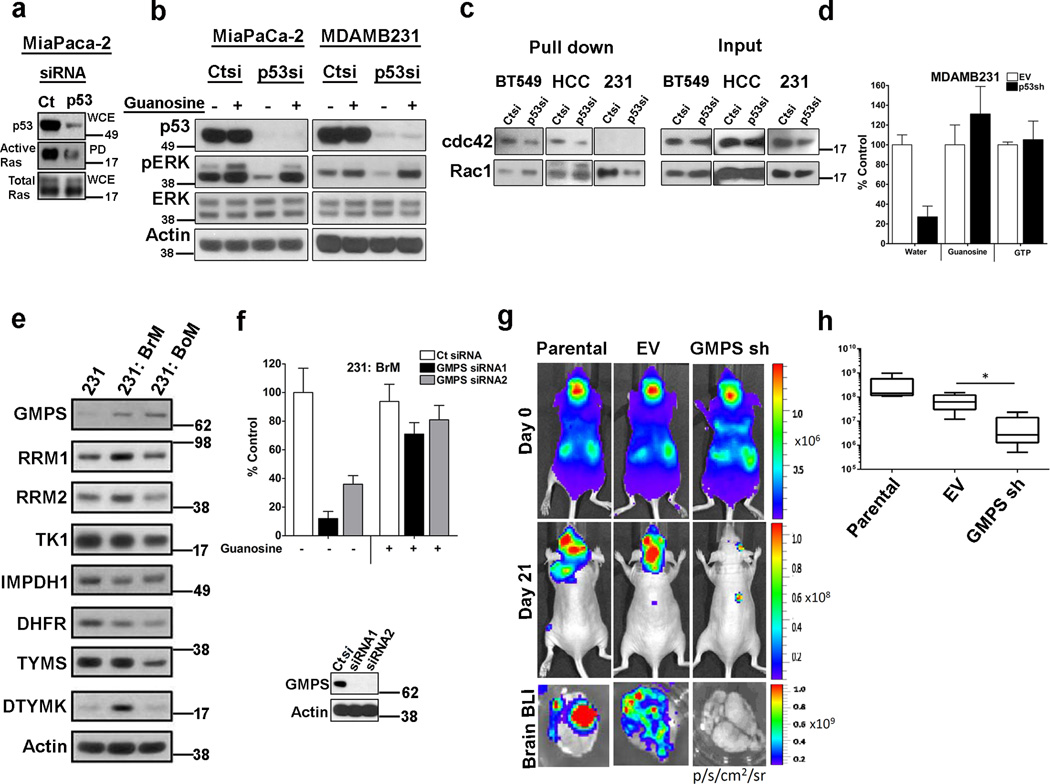

Impact of GTP levels on invasion phenotype

The GTP binding proteins, GTPases (e.g. Ras, Rac1, RhoA, Cdc42), cycle between active (GTP bound) and inactive (GDP bound) states regulated by their interactions with GEFs and GAPs. Previously, it had been demonstrated that depletion of GTP levels by inhibiting IMPDH with mycophenolic acid leads to decreased activity of the GTPases Rho, Rac and cdc4234. Since mtp53 knockdown reduced GTP levels (Fig. 2c), we determined if those changes were sufficient to impact GTP-dependent protein activity. Using the active Ras pulldown assay, we determined that mtp53 knockdown in MiaPaCa-2 cells reduced the amount of active Ras (Fig. 4a). Consistent with the diminished Ras activity, mtp53 knockdown reduced phospho-ERK levels (Fig. 4b). Similarly, p53 knockdown in MDAMB231 cells reduced phospho-ERK levels. Importantly, addition of guanosine to the medium was sufficient to restore phospho-ERK levels (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, addition of GTP to the medium, which has been reported to be internalized by cells, also restored the phospho-ERK levels35 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). We also assessed the impact of p53 knockdown on the activation state of the GTPases, Rac1 and cdc42. Mtp53 knockdown in BT549 and HCC38 cells reduced GTP-bound cdc42 (Fig. 4c). We could not detect cdc42 activity in the MDAMB231 cells. In the MDAMB231 cells, mtp53 knockdown reduced the level of GTP-bound Rac1 (Fig. 4c). Next we assessed if the reduction in GTP correlated with changes in invasive activity after mtp53 knockdown. Knockdown of mtp53 in MDAMB231 cells reduced cell invasion by approximately 70% (Fig. 4d). We reasoned that since addition of exogenous guanosine or GTP to the culture media restored phospho-ERK levels, then they might also be able to rescue the invasion defect observed upon mtp53 knockdown. Indeed, addition of either guanosine or GTP restored the invasive activity of these cells (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig.4b). A similar phenotype was observed in BT549 (Supplementary Fig. 4c). These data suggest that mtp53's maintenance of the intracellular GTP concentration contributes to intracellular signaling and cell invasion.

Figure 4. Maintenance of GTP levels is important for cell invasion.

(a) The active Ras pulldown assay was performed on MiaPaCa-2 cells transfected with either control (Ct) or p53 siRNA (p53si). (b) MiaPaCa-2 and MDAMB231 cells were transfected with either control (Ct) or p53 siRNA (p53si) and then harvested for western blot analysis to detect phospho-ERK. (c) The active Rho GTP ases pulldown assays were performed on HCC38, BT549 and MDAMB231 cells transfected with either control (Ct) or p53 siRNA (p53). (d) The Matrigel invasion assay was performed on cells infected with empty vector (EV) or p53 shRNA (p53sh); 100 µM of exogenous guanosine or 1 mM of GTP was supplemented in the medium as indicated. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of two independent replicates. (e) Western blot analysis of parental MDAMB231 (231) and its derivatives: MDAMB231-BrM (231-BrM), MDAMB231-BoM (231-BoM). (f) Analysis of GMPS knockdown in 231-BrM invasive activity and rescue by supplementation of guanosine or GTP in the medium. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of three independent replicates. Inset is a western blot analysis of GMPS levels after control or GMPS siRNA transfection. (g) Top and middle panels; Representative images from each group showing bioluminescence imaging (BLI) of brain metastatic lesions on day 0 and day 21. Lower panel; representative BLI images of whole brains from each experimental group. (h) Total photon flux of brain metastatic lesions was measured BLI at the end point. n=5; * indicates p<0.05. Two-tailed t-test was used to calculate P values. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of five replicates.

GMPS knockdown perturbed invasion and metastasis

Thus far, our study established that mtp53 regulates NMG which contributes to the proliferation and invasiveness phenotype of cancer cells. The latter phenotype is thought to correlate with metastasis in vivo, and thus we wanted to determine if NMG expression correlated with metastatic potential. For this analysis, we compared NMG expression between cell lines that differ in their metastatic ability. To reduce the probability that gene expression differences reflect unknown variables, we performed this comparison on the isogenic cell lines, MDAMB231 and its highly metastatic derivatives MDAMB231-BrM (231:BrM) and MDAMB231-BoM (231-BoM)36, 37. These 231:BrM and 231:BoM cell lines were derived through in vivo selection based on their high predilection for metastasis to the brain and bone, respectively36, 37. Our analysis revealed a modest upregulation of RRM1 and RRM2, and a more pronounced increase in DTYMK and GMPS in the BrM line. In the 231:BoM cell line, only GMPS was distinctly upregulated (Fig. 4e). Hence we asked if GMPS, which catalyzes the final step of de novo synthesis of GMP, contributes to the invasive phenotype of these cells. Initially, comparison of the invasive activity of the 231 and 231:BrM cells revealed that the latter exhibited ~2 fold higher invasive capacity (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Stable depletion of GMPS decreased GTP by 30%, which led us to speculate that it might also impact GTP dependent processes (Supplementary Fig. 4e). GMPS knockdown in the MDAMB231 cells reduced phospho-ERK levels, which could be rescued by addition of guanosine to the media (Supplementary Fig. 4f). Since the 231 BrM cells had higher levels of NMG expression, we further characterized it by determining if GMPS knockdown affected their matrigel invasive activity (Fig. 4f). Two different GMPS siRNAs potently reduced cell invasion by 90% (siRNA1) and 65% (siRNA2) (Fig. 4f and Supplementary 4g). Exogenous guanosine restored invasive activity to approximately 70% (siRNA1) and 75% (siRNA2) (Fig. 4f). Taken together, these data reinforce the notion that alterations in NMG expression can impact cell invasion.

The IMPDH enzymes (IMPDH1 and IMPDH2) catalyze the rate-limiting step in the de-novo synthesis of GMP, the GTP precursor, and they function directly upstream of GMPS. Since IMPDH2 was also downregulated by mtp53 knockdown, we assessed if the IMPDH inhibitor AVN-944 could synergize with GMPS knockdown. AVN-944 reduced cell invasion by approximately 40% (Supplementary Fig. 4h). The combined knockdown of GMPS and AVN-944 treatment reduced cell invasion by approximately 80% (Supplementary Fig. 4h). Thus, the dual targeting of the GMP synthesis pathway effectively suppresses cell invasion.

Next we assessed the role of GMPS using an in vivo metastasis model. The 231:BrM cells exhibit a high predilection for metastasis to the brain, and thus we employed these cells to examine the impact of GMPS depletion on their metastatic activity. Parental 231:BrM, or derivative cells infected with either an empty lentiviral vector (EV) or a GMPS shRNA (GMPS sh) were injected into nude mice, and then the mice were monitored for tumor growth by bioluminescent imaging. Analysis of bioluminescence immediately after injection of all three cell groups revealed the presence of cancer cells throughout the body (Fig. 4g). After three weeks, brain metastatic lesions could be detected by bioluminescent imaging in the parental and empty vector cells (Fig. 4g,h). In stark contrast, GMPS depleted cells were unable to produce similar brain lesions (Fig. 4g,h). Ex-vivo analysis of whole brains confirmed that the parental and empty vector cells metastasized to the brain and the GMPS knockdown cells did not (Fig. 4g,h). Therefore, GMPS is required for the development of these brain metastatic lesions.

Role of dCK in sensitivity of mtp53 cells to chemotherapy

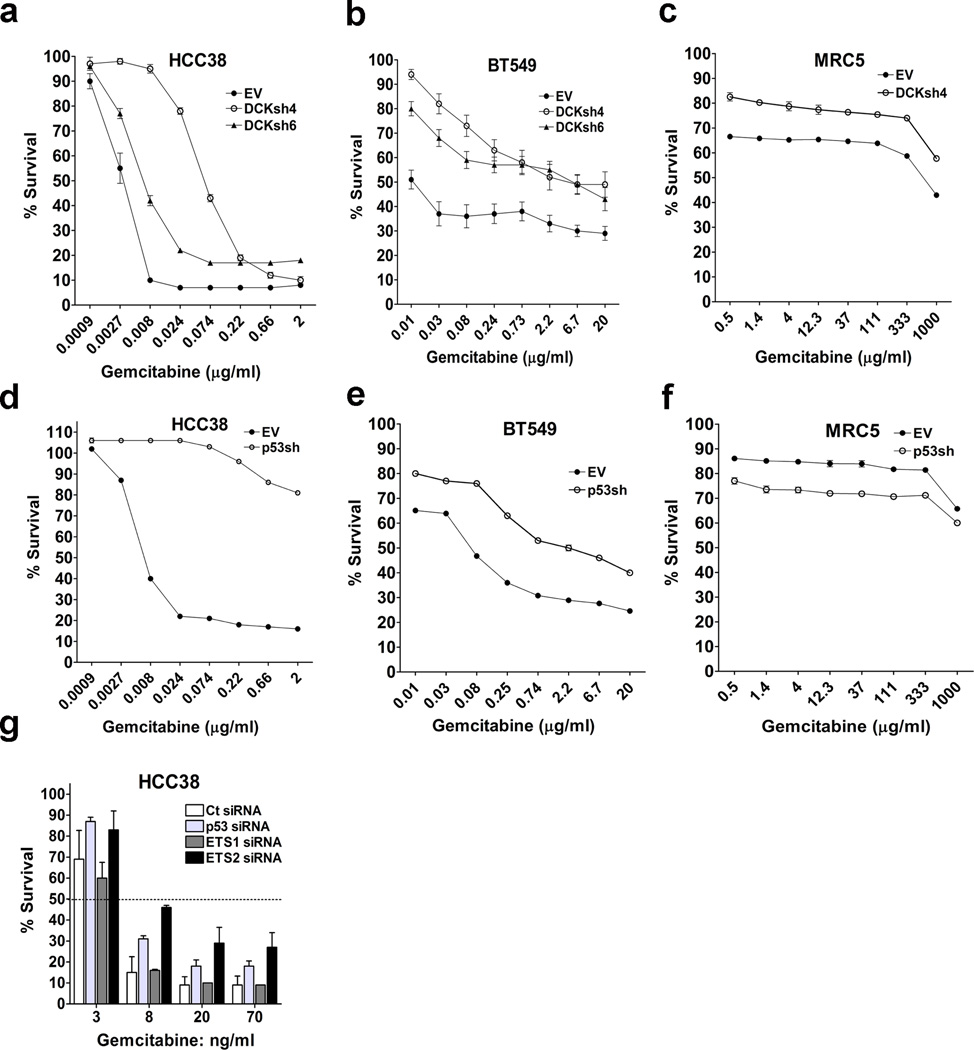

dCK catalyzes the rate-limiting phosphorylation step for activation of gemcitabine, thus making it a key regulator of the sensitivity to this prodrug38, 39, 40, 41. Mtp53 upregulates dCK expression in multiple cell lines (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 5a). Also, comparison of cell lines that differ in p53 status revealed that dCK expression was higher in those harboring mtp53 than in normal and WTp53 containing cancer cells (Fig. 3c). Given that dCK expression correlates with responsiveness to gemcitabine and that mtp53 upregulates dCK, we assessed if p53 status correlated with sensitivity to this drug. The normal cells, MRC5, were essentially refractory to gemcitabine (Supplementary Table 1). Likewise, cancer cells that have WTp53 (ZR751, ZR7530, MDAMD175V11a, UACC893, A549, and U2OS) were relatively resistant (Supplementary Table 1). On the other hand, breast cancer (HCC38 and BT549) and pancreatic (MiaPaCa-2) cells that harbor mtp53 were orders of magnitude more sensitive (Supplementary Table 1). dCK knockdown significantly conferred resistance to gemcitabine in the mtp53 cell lines, which is in agreement with the requirement of dCK for activation of nucleoside analogs39, 40, 41 (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 5b). As expected, dCK knockdown in MRC5 further decreased the sensitivity to gemcitabine (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 5b). We reasoned that since mtp53 induced dCK, then suppression of mtp53 should lead to reduced dCK expression and resistance to gemcitabine. Indeed, depletion of mtp53 (HCC38 and BT549), but not WTp53 (MRC5, MCF10a, MCF7 and ZR751), significantly induced resistance (Fig. 5d,e,f and Supplementary Fig. 5b,f,g,h). IC50 values and resistant factors can be seen in Supplementary Table 2. Consistent with our observation that mtp53 conferred sensitivity to gemcitabine, mtp53 expression in either MCF10a (R249S) or H1299 (R175H) also sensitized these cells (Supplementary Fig. 5i,j). The ability of dCK or p53 knockdown to confer resistance to gemcitabine in the mtp53 cells was specific to this drug since these cells were not protected from the non-nucleoside analog agents, cisplatin and doxorubicin (Supplementary Fig. 5c,d,e). To further investigate the link between mtp53 and sensitivity to gemcitabine, we assessed if knocking down its transcriptional regulatory partner, ETS2, would also provide resistance. Transient knockdown of either p53 or ETS2, but not ETS1, significantly induced resistance to gemcitabine. Since mtp53 and ETS2 (and not ETS1) cooperate to induce dCK expression, these results provide an additional line of evidence that upregulation of dCK expression by mtp53 sensitizes cells to gemcitabine (Fig. 5g). Taken together, our study suggests that by upregulating dCK, mtp53 renders cancer cells more sensitive to nucleoside analogs.

Figure 5. Role of dCK and p53 in cellular sensitivity to gemcitabine.

(a–c) Cells infected with either an empty vector (EV) or dCK shRNA (dCKsh4 or dCKsh6) were treated with different doses of Gemcitabine and after 72 hours, analyzed by MTT assay. (d–f) Cells infected with either an empty vector (EV) or p53 shRNA (p53shRNA) were treated for 72 hours and then analyzed by MTT assay. (g) HCC38 cells were transfected with either of these siRNAs: control (Ct), p53 (p53si), ETS1 (ETS1si) or ETS2 (ETS2si). The cells were then treated for 72 hours with the indicated doses of Gemcitabine. For all dose-response curves error bars indicate mean ±SD of three independent replicates.

Mtp53 is dependent on dCK to prevent replication stress

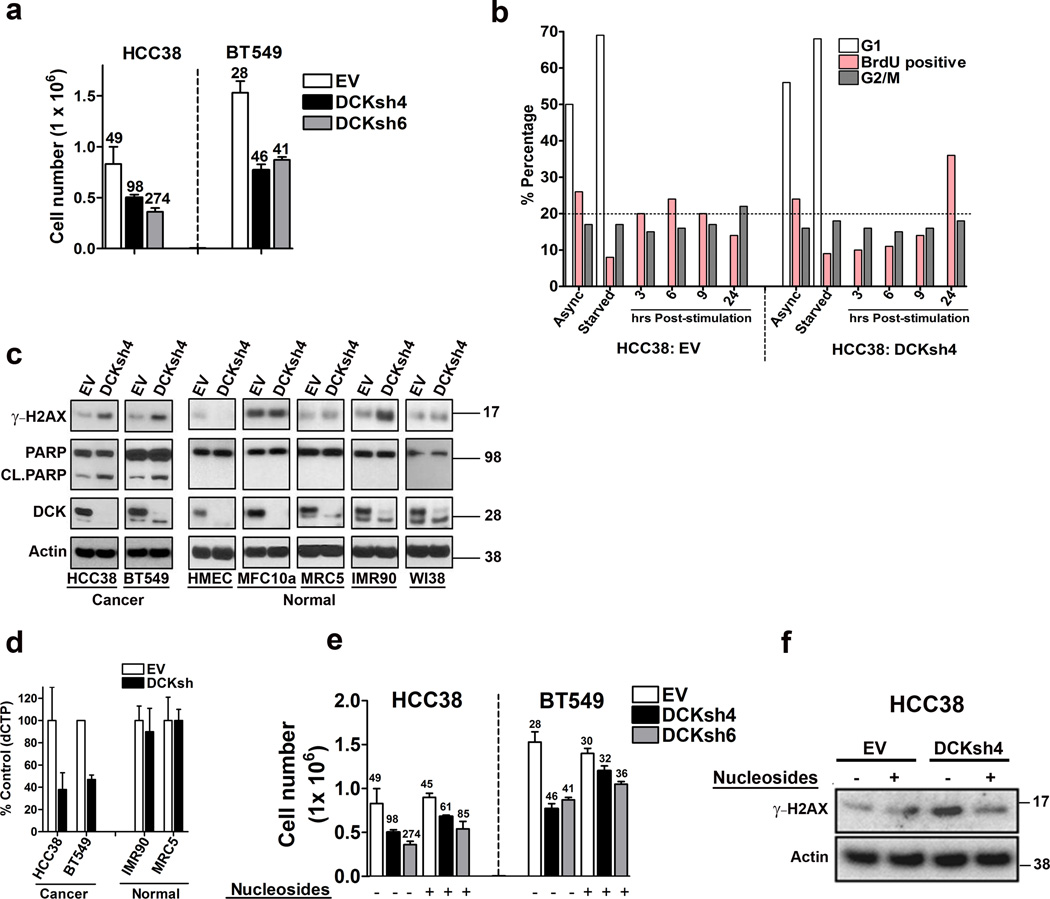

We were struck by the observation that mtp53 upregulates both the de novo synthesis and nucleoside salvage pathways. The upregulation of dCK might reflect a need for higher levels of dNTP pools to sustain a high proliferation rate. Previous studies have suggested that dCK is not required for proliferation and dCK knockout mice are born at normal Mendelian ratios39, 40, 41, 42, 43. However, these mice display severe hematopoietic defects affecting both lymphoid and erythroid lineages42, 43. Unexpectedly, upon longterm propagation (> 1 week) of cells with dCK knockdown, we observed a greatly reduced proliferative rate in the mtp53 harboring cells (Fig. 6a). Indeed, knockdown of dCK in HCC38 and BT549 reduced cell proliferation by more than 50% as determined by cell count (Fig. 6a). To eliminate the possibility that this was an off-target effect, we tested 10 different dCK shRNAs and we observed similar a reduction in proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Importantly, dCK knockdown in the normal human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC), or the lung fibroblasts MRC5, IMR90 or WI38 did not impact their proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Thus, these data suggested that mtp53 harboring cells exhibited a synthetic sick or lethal phenotype upon dCK knockdown.

Figure 6. dCK knockdown induces synthetic lethal phenotype involving replication stress in mtp53 expressing cells.

(a) HCC38 and BT549 cells were infected with an empty vector (EV), or dCK shRNA (dCKsh4 or dCKsh6) and then seeded to determine cell doubling times. The numbers above the bars indicate the cell doubling time. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of three independent replicates. (b) HCC38 cells infected with an empty vector (EV) or dCK shRNA (dCKsh4) were left in serum containing medium (Async), or serum starved overnight (starved). The cells were then stimulated to grow by the addition of medium supplemented with serum for the indicated time. The cells were pulse labeled with BrdU for 1 hour prior to harvest at the indicated time points, and then processed to determine BrdU incorporation and cell cycle distribution by FACS analysis. (c) Western blot analysis was performed to detect the presence of γ-H2AX, PARP and cleaved Parp (Cl. PARP), dCK and actin in the indicated mtp53 expressing cell lines (HCC38 and BT549) and the normal cells (HMEC, MCF10a, MRC5, IMR90 and WI38). (d) Empty vector or dCKsh4 infected cells were analyzed for dCTP content. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of three independent replicates. (e) Cell Doubling time was analyzed in empty vector (EV) or dCK shRNA (dCKsh4 or dCKsh6) infected cells. Nucleosides (AUGC) were added to the medium as indicated. The numbers above the bars indicate the cell doubling time. Error bars indicate mean ±SD of three independent replicates. (f) Western blot analysis of HCC38 cells infected with empty vector (EV) or dCK shRNA (dCKsh). The cells were treated with nucleosides as indicated and western blot analysis was done to assess H2AX phosphorylation (γ-H2AX).

Imbalance in dNTP pools can lead to decreased proliferation due to the activation of a replication stress response. Furthermore, cells exposed to elevated intracellular thymidine concentrations are dependent on the dCK to maintain proper dNTP pools43, 44. Therefore, an alternative explanation for the upregulation of dCK by mtp53 is that it is required to maintain dNTP pools in the presence of elevated dTTP levels. This possibility was bolstered by the observation that among the many NMG upregulated by mtp53 are enzymes from the de novo and nucleoside salvage pathways involved in the synthesis of dTTP (DHFR, TYMS, DTYMK and TK1). To begin to dissect this possibility, we first compared dTTP levels between normal and mtp53 harboring cancer cells. Whereas IMR90 and MRC5 cells had approximately 2 pmol/million cells of dTTP, BT549 had almost 5 times more (9 pmol/million cells) and HCC38 had approximately 16× more (32 pmol/million cells). These data supported the possibility that dCK knockdown triggered an imbalance in the dNTP pools, resulting in replication stress. If this is the case, then cell proliferation defects, especially during S phase, should be present upon dCK knockdown in mtp53 harboring cells. Therefore, we characterized the progression of these cells through the cell cycle. We synchronized cells by overnight serum starvation, serum stimulated them to promote entry into the cell cycle and pulsed them with BrdU to examine entry and progression through S phase. In cells infected with an empty vector (PLKO), an increase in BrdU incorporation was evident by 3 hours after serum stimulation, peaked at 6 hours and then gradually decreased afterwards (Fig. 6b). The decrease in BrdU incorporation correlated with an increase in the G2/M fraction, indicating that the cells have completed S phase and proceeded to the next phase. In contrast, dCK knockdown cells exhibited a substantial delay in entry and passage through S phase. Whereas 6 hours after stimulation, the PLKO control cells had approximately 25% of the cells staining positive for BrdU, the dCK knockdown cells only had 12%. A substantial increase in BrdU incorporation in the dCK knockdown cells was apparent only at 24 hours post-stimulation (32% positive) (Fig. 6b). Additionally, the G2/M fraction did not substantially increase, indicating that the large proportion of cells in S phase were likely undergoing replication stress and were unable to proceed to the next phase. A similar trend was observed in the MDAMB231 and BT549 cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 6c,d). To substantiate these observations we examined the phosphorylation of the histone variant H2AX (γ-H2AX), a biochemical marker of replication stress. dCK knockdown increased γ-H2AX levels in the mtp53 harboring cells (HCC38 and BT549), but not in the WTp53 cells (HMEC, MRC5, IMR90, WI38, MCF10a) (Fig. 6c). Additionally, we observed PARP cleavage, an indicator of apoptotic cell death, only in the mtp53 harboring cells. Taken together, these data support the notion that mtp53 harboring cells are dependent on dCK and that its knockdown provokes a synthetic sick or lethal response involving replication stress.

Our data suggested that mtp53 harboring cancer cells, and not normal cells, are dependent on dCK activity to prevent an imbalance in the dNTP pool. If this interpretation is correct, then we would anticipate that dCK knockdown should only impact dCTP levels in the mtp53 harboring cells and not the normal cells. Therefore, we infected mtp53 harboring cells (HCC38 and BT549) and normal cells (IMR90 and MRC5) with an empty vector (PLKO) or dCK shRNA and compared dCTP levels. In accordance with our prediction, dCK knockdown reduced dCTP levels in HCC38 and BT549 by approximately 60%, whereas it had no effect in IMR90 and MRC5 (Fig. 6d). The other dNTPs were not appreciably affected in any of the cells that we examined. Ribonucleotide Reductase (RNR) synthesis of deoxycytidine diphosphate (dCDP) from CDP can be allosterically inhibited by elevated dTTP levels, thereby preventing the subsequent formation of dCTP through the de novo nucleotide synthesis pathway45, 46. In contrast, excess dTTP levels do not prevent RNR from producing the purine dNTPs45. Since purine dNTPs were not affected by dCK knockdown, this was in line with a mechanism whereby in mtp53 harboring cells, elevated dTTP levels attenuate the production of dCTP via the de novo nucleotide synthesis pathway by inhibiting RNR production of dCDP. Hence, mtp53 harboring cells are dependent on dCK to maintain a balance in the dNTP pool in order to avert replication stress. If this is the case, then we would predict that supplementing the cell culture media with nucleosides should rescue cell proliferation and reduce replication stress. To test the validity of this putative mechanism, we supplemented dCK knockdown cultures with exogenous nucleosides in order to restore the activity of the de novo nucleotide synthesis pathway. Indeed, addition of exogenous nucleosides rescued the decreased proliferation rate that occurred upon dCK knockdown in HCC38 and BT549 (Fig. 6e). Furthermore, the nucleosides also suppressed the elevated γ−H2AX levels detectable by western blot, suggesting that the ability of the nucleosides to restore the proliferative activity of the dCK knockdown cells was due to suppression of replication stress (Fig. 6f). In summary, the de novo nucleotide synthesis pathway alone is not sufficient to maintain balanced dNTP pools and dCK is required to avert replication stress in mtp53 harboring cells.

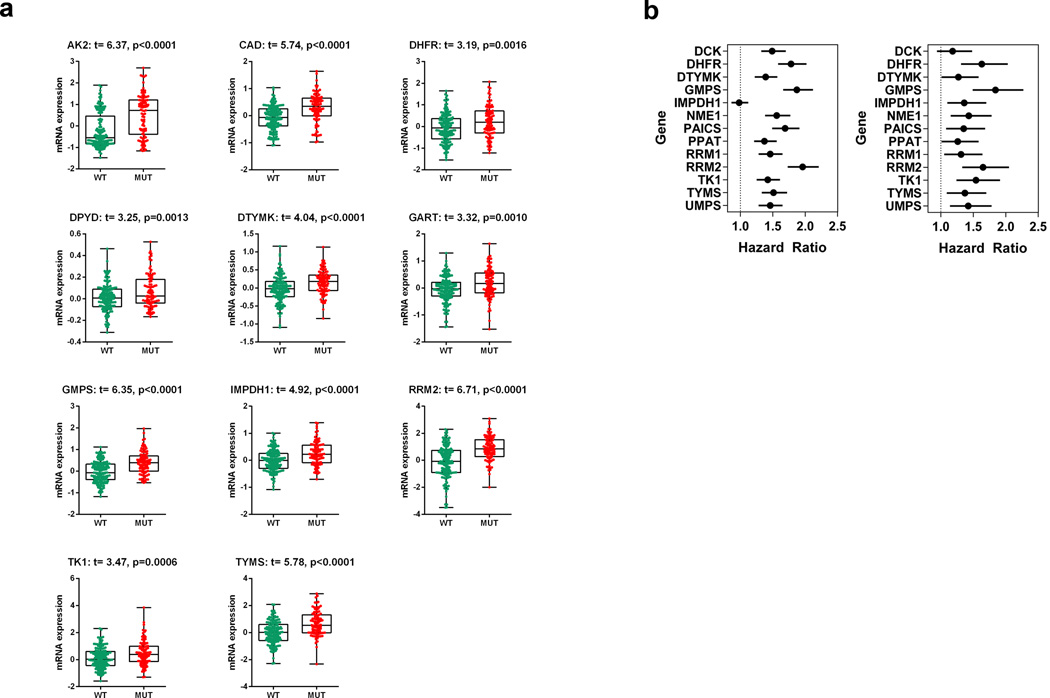

Elevated expression of NMG in breast cancer patients

Mtp53 is known to promote metastasis and our in vitro studies above suggest that the upregulation of NMG may contribute to this process. We then asked if regulation of nucleotide metabolism pathways by mtp53 is observed in human breast cancer patients. For this, we examined a data set of 537 breast cancer transcriptomes. Only samples with known p53 status (145 WT and 94 mutants) were stratified and included in this analysis. Remarkably, out of 16 genes analyzed, 11 exhibited significantly elevated expression in mtp53 breast tumors (Fig. 7a). We propose that this should be referred to as the mtp53 NMG signature expression pattern. Next we wanted to know if up-regulation of nucleotide metabolism pathway genes has any correlation with patient prognosis, specifically clinical outcome. For this we used a dataset of 4142 breast cancer transcriptomes with clinical outcome data. We assessed the correlation between NMG expression levels and relapse free survival (RFS) and distant metastasis free survival (DMFS). Strikingly, elevated expression of signature NMG is associated with a significantly poorer RFS and unfavorable DMFS. Moreover the hazard ratios for most of the genes (for both RFS and DMFS) are ≥1.5 and some are very close to 2 (RRM2 and GMPS) (Fig. 7b). Kaplan-Meier curves for RFS and DMFS are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7a,b,c,d. Thus, the elevated NMG expression not only correlated with mtp53 status in cancers, but also with poorer outcome in terms of RFS and DMFS.

Figure 7. MTp53 correlates with enhanced NMG signature expression and worse prognosis.

(a) Comparison of mtp53 target gene (DHFR, DTYMK, GMPS, IMPDH1, RRM2, TK1, TYMS) expression was performed on a dataset of 537 breast cancer transcriptomes61. Samples were divided based on their p53 status (145 wildtype vs. 94 mutant) and the microarray dataset was normalized using the Robust Multi-array Average (RMA) algorithm, and the baseline adjusted to the median of all samples62. A t-test was performed on log2 transformed expression data, and only P values of less <0.05 were considered statistically significant and genes that met that criterion are shown. (b) Estimated hazard ratios for the RFS and DMFS (Hazard ratio; the relative risk for one unit increasing in the gene expression) with 95% confidence intervals and log rank test P value. P values <0.05 mtp53 target genes were significantly associated with RFS and DMFS.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate that mtp53 upregulates nucleotide biosynthesis, a metabolic activity that both drives and sustains cancer development. Mtp53 regulates the nucleotide pools by transcriptionally inducing the expression of multiple genes involved in the de novo nucleotide synthesis and salvage pathways. We demonstrated that mtp53 together with its binding partner, ETS2, directly regulates the expression of multiple NMG.

It is intriguing that both WTp53 and mtp53 induce RRM2b. However, WTp53 induces RRM2b in response to genotoxic stress to repair DNA damage and in contrast, mtp53 constitutively upregulates its expression. Whether or not RRM2b contributes to DNA repair in mtp53 cells remains to be determined.

Our data support the concept that altering nucleotide pools can impact a cell’s invasive phenotype and we implicate the control of nucleotide pools by mtp53 as an important component of its gain-of-function activities. We noted that although endogenous WTp53 knockdown did not affect cell invasion, mtp53 expression in either MCF10a or H1299 cells made them more invasive (Supplementary Fig. 8a,b). Mtp53 knockdown reduced GTPase activity, phospho-ERK levels and matrigel invasion. The fact that supplementation with exogenous guanosine or GTP rescued these phenotypes suggests that mtp53 metabolically drives these processes by elevating GTP levels. We also demonstrated that GMPS knockdown, results in reduced GTP levels and blocks the development of metastatic lesions. These data are in line with previous studies which found that decreased GTP abundance impacts cell migration and invasion by downregulating GTPase activity31, 34. GMPR is downregulated in metastatic melanoma cells resulting in elevated GTP levels, and activation of GTPases and invasion. Since restored expression of GMPR reduced GMP levels and suppressed invasion, this supports the possibility that targeting GTP biosynthetic pathways may have clinical utility. Indeed we observed that the combined suppression of GMP biosynthetic enzymes (GMPS and IMPDH) decreased cell invasion (Supplemental Fig. 4h).

Importantly, a retrospective analysis revealed up-regulation of nucleotide metabolism genes specifically in cancer patients with mtp53, and this correlated with reduced cancer free survival and metastasis. Two of the mtp53 target genes, GMPS and dCK, are part of the MammaPrint 70-gene signature that is associated with poor clinical outcome in breast cancer patients47. Moreover, RRM2, p53R2 and TYMS have also have been correlated with a poor prognosis in breast and other cancers48. Taken together, mtp53 collectively upregulates NMG expression and thus provides the fuel to drive its gain-of-function repertoire (i.e. aberrant proliferation, invasion and metastasis).

We observed that different mtp53 proteins regulate NMG expression, indicating that this is a common gain-of-function activity of diverse p53 mutants. However, in vivo studies have shown that not all mutant p53 proteins exhibit the same degree of gain-of-function activities49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54. Importantly, even a seemingly subtle difference of one amino acid (R248W vs. R248Q) can have a large impact on the in vivo gain-of-function activity of mtp5349, 53. In vitro studies also have shown that single amino acid differences in mtp53 proteins can impact their protein-protein interactions55, 56, 57. Mtp53 proteins containing an arginine at codon 72 bind and disable p73, whereas mtp53 proteins containing a proline at this codon cannot55, 56. Moreover, certain mtp53 proteins have the capacity to form aggregates and disable interacting transcription factors58. Therefore, mtp53 proteins can exhibit a multitude of nuanced properties that manifest as gain-of-function capacities. We speculate that in addition to these inherent differences in the mtp53 proteins, other genetic lesions in cancer cells may further influence mtp53’s ability to function as an oncogene.

Several mtp53 target genes that have been implicated in playing a role in its gain-of-function activities including regulation of cell survival (Bcl-xL), nucleotide metabolism (MYC), invasion (MMP3, MMP13) and proliferation (EGFR, CCNA, CDK1, CDC25C, MYC, and PCNA)59. Transient knockdown of mtp53 was sufficient to reduce expression of nucleotide metabolism genes, proliferation and invasion, but within the same time span we did not observe a consistent decrease in expression of most of these mtp53 target genes (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Of significant note, we did not observe any changes in myc protein levels after mtp53 knockdown which is important because myc also regulates NMG expression (Fig. 2a)27. Therefore, it is unlikely that mtp53 indirectly induces NMG transcription by upregulating myc. We did observe that MMP3 expression decreased after mtp53 knockdown in all three cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 8c). We cannot rule out the possibility that MMP3 plays a role in the mtp53 driven invasion process in these cells, however, the finding that either guanosine or GTP supplementation restored cell invasion suggests that the maintenance of GTP levels by mtp53 is an integral component of this gain-of-function activity.

Our study also revealed that by upregulating NMG involved in dTTP production, mtp53 causes cells to be dependent on dCK. We speculate that the elevated dTTP levels in mtp53 harboring cells allosterically attenuate dCDP production through the de novo nucleotide synthesis pathway (i.e. RNR)45, 46. Mtp53 harboring cells compensate for the elevated levels of dTTP by utilizing dCK to recycle deoxycytidine through the nucleoside salvage pathway. The fact that exogenous nucleotides suppress these phenotypes (replication stress and proliferation defect) supports the notion that dCK is required to maintain a balance in the dNTP pools. These data reveal the mechanism underlying the synthetic sick or lethal genetic interaction between mtp53 and dCK.

Finally, we contend that the elevation of dCK expression can be viewed as a liability in the mtp53 transcriptome that may permit therapeutic intervention. Thus, the status of p53 may aid in the selection of chemotherapeutic agents used as first line treatment.

Methods

Cell lines and drugs

The cell lines were purchased from ATCC and cultured according to the vendor’s instructions. The p53 null H1299 cells were transfected with either an empty vector or vector expressing either the R175H or R273H mutant p53 cDNA and selected with neomycin. Single cell clones expressing mtp53 were selected and propagated in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FCS. Gemcitabine, cisplatin and doxorubicin were purchased from the University of Mississippi Pharmacy. AVN-944 was purchased from Chemie Tek (USA).

Cell proliferation assay

5000 cells for cancer cell lines and 10000 for normal cell lines were seeded in 80 µl of media and incubated overnight. Several drug concentrations were prepared by serial dilutions and 20 µl (5×) of each drug concentration was added in triplicates. After 72 hours of incubation, 10 µl of MTT (5mg/ml) (Boston bioproducts) was added. Cells were incubated in a tissue culture incubator for 3 hours, after which 50 µl of SDS lysis buffer (10% SDS pH 5.5; 0.01M HCl) was added and incubated overnight. Plates were read at 570 nm using a Synergy plate reader. Percentage survival for each dose was calculated by multiplying absorbance values with 100 and divided by control absorbance value.

Colony formation assay

1000 cells were seeded in 6 well plates and incubated until several colonies appeared. Media was replenished every two days. The media was then removed, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then 1ml of staining solution (0.5% crystal violet, 6% glutaraldehyde) was added and incubated for 30 minutes. Plates were washed with distilled water several times until all the excess stain was removed.

Invasion assay and GTP rescue

Invasion assay was carried our according to manufacturer’s instructions (BD BioCoat 24 well matrigel invasion chambers). GTP (1mM, Sigma) was added both in upper and lower chambers for invasion rescue. Invasion of mtp53 knockdown cells was expressed as a percentage relative to control cells.

In vivo animal experiments

For in vivo metastasis assay, Nu/Nu female mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). All animal studies were conducted in accordance with NIH animal use guidelines and a protocol approved by UMMC animal care committee. 8 to 9 weeks old mice were randomly divided into 3 groups. Each group was injected with 500,000 luciferase-labeled cells in 100 µl PBS into left cardiac ventricle. Mice were immediately imaged for photon flux measurement using IVIS Xenogen bioimager (Caliper) to ensure successful injection without any leakage. The brain metastasis progression was monitored every week and the luminescence was quantified using Living Image version 4.4 software. After 3 weeks, the whole brains were excised from the mice incubated in 0.5mg/ml luciferin containing PBS and photon flux was measured.

Active Ras Pulldown Assay

MiaPaCa-2 cells were transfected with either a control or p53 siRNA, and two days later, the cells were lysed and active ras was detected using the Active Ras Pulldown and Detection kit (Pierce) following the manufacture’s protocol.

Active Rho GTP ases Pulldown Assay

HCC38, BT549 and MDAMB231 cells were transfected with either control or p53 siRNA. Two days later, the cells were lysed and active Rho A, Rac1 and cdc42 were detected using the Active Rho A GTP ases Pulldown and Detection kit (CELL BIOLABS, INC.) following the manufacture’s protocol.

Transient and stable gene knockdowns

siRNA knockdowns were performed using RNAiMax (Invitrogen). For shRNA knockdown, 293FT cells were used to generate lentiviruses carrying the shRNA, the target cells were infected and then selected for 2–3 days with puromycin. All siRNA and shRNA sequences were listed in supplementary methods.

Nucleoside rescue

Cells were seeded at a density of 50000–100000 cells in duplicates. For one set of wells nucleosides were added (EmbryoMax nucleosides: Millipore) and incubated for 72 hours. Every other day, the media was replenished and nucleosides were added. The media was aspirated and then the cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, spun down and resuspended in media and counted using a Beckman coulter single cell.

Cell cycle analysis

0.5 × 106 cells were seeded in 60 mm dishes and incubated overnight. Media was aspirated and washed once with PBS and trypsinized. Cells were collected and centrifuged at 500 g for 5 minutes at 4°C and washed with PBS. Finally cells were fixed in 1ml of ice cold 70% ethanol and stored at −20°C until analysis. After overnight fixation, cells were washed with PBS and treated with RNase (10 mg/ml) for 15 minutes followed by staining with propidium iodide (Sigma) (50 µg/ml). Stained cells were analyzed using Beckman coulter flow cytometer (488 Argon laser).

BrdU staining

0.5 × 106 cells were seeded in 60 mm dishes and incubated overnight. To one set of plates, media was removed and washed two times with PBS. Cells were either maintained in serum containing media, or serum starved for 24 hrs by culturing them in media without FBS. After 24 hrs 10 µM of BrdU (Millipore) was added to the zero hour plate and incubated for 30 minutes. Media was aspirated and washed once with PBS and the cells were trypsinized. Cells were collected and centrifuged at 500 g for 5 minutes at 4°C and washed with PBS, fixed in 1ml of ice cold 70% ethanol and stored at −20°C until analysis. For the serum starved plates, fresh media with FBS was added, and the cells were pulse labeled with BrdU at different time points and processed as above. After overnight fixation, cells were stained with BrdU antibody (Novus biologicals) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and analyzed using a Beckman coulter flow cytometer (488 Argon laser).

Western blotting

To prepare cell lysates for western blotting, the cells were lysed on the dish using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, scraped and placed into microcentrifuge tubes, sonicated, and centrifuged at 20,000g at 4C to remove insoluble material. Protein concentration was determined using the Micro BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo) and equal amounts of protein were resolved on Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels. Antibody information can be found in supplemental methods. The most important uncropped scanned full blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

QPCR

RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Molecular research center, Inc.) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity was verified using RNA chip (Agilent bioanalyzer). 1 µg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA (20 µl reaction) (Biorad’s Iscript select cDNA synthesis kit) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was diluted 1:10 and used for QPCR with SYBR green detection (Invitrogen). Phusion HF reaction buffer, phusion HF DNA polymerase and dNTPs used for QPCR were purchased from New England Biolabs. Biorad CFX96 Touch real-time PCR detection system was used. Biorad CFX manger software was used to calculate fold changes in gene expression. All primers sequences were listed in supplementary methods. All NMG are defined in supplementary table 3.

CHIP and Immunoprecipitation assays

All CHIP assays were performed using the EZ Chip protocol (Millipore). All primers used for CHIP were listed in the supplementary methods. For co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) of proteins, cells were washed with PBS, harvested, and lysed in IP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05 mM EDTA, 1% NP40, 10% glycerol). Lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 × g (4°C) for 20 mins, pre-cleared with BSA-salmon sperm blocked protein-G agarose (KPL) for 1 hr at 4°C and then p53 (D01) was used for immunoprecipitation. Uncropped scanned full blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Luciferase assay

Cell based luciferase assays were performed using the dual luciferase Promega kit. 15000 cells were seeded in a white 96-well clear bottom plates. In tube A, pGL4 luciferase vector with or without promoter of interest, siRNAs (Consi or p53si or ETS2si) and pRLTK stocks were diluted in optimem media. In tube B, lipofectamine and optimem mixtures were prepared. The ratio of lipofectamine vs DNA plasmid is 1:3, which means for every µg of DNA we added 3 µl of lipofectamine. Contents in tube B were mixed with A and incubated for 20 minutes. 24 µl of master mix (50 ng of pGL4 control luciferase vector or pGL4 test plasmids (NMG promoters cloned into pGL4), 5 ng of pRLTK (Renilla luciferase internal control) and 50 ng of siRNA) was dispensed to each well in 6 replicates using multichannel pipette. After 48 hrs, 50 µl of dual glo luciferase reagent was added and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. Luminescence was measured using PerkinElmer 1420 multilabel counter VICTOR3. Then 50 µl of dual glo stop and glo reagent was added and after 10 minutes again luminescence was measured. Reporter activity from internal control was used to normalize the test reporter data. Fold changes were calculated by dividing average reporter activity in Consi wells with either p53si or ETS2si wells. Promoters of NMG were amplified using the primers listed in supplementary methods.

dNTPs and rNTPs quantification

dNTPs were quantified following the protocol as previously described43. In brief, cells were collected and resuspended in 1 ml of ice-cold 60% methanol, vortexed and stored overnight at −20C, evaporated and then the dry pellets were resuspended in hexylamine. dNTP concentrations were determined using LC-MS/MS. For rNTP extraction, media was discarded by turning the 10 cm culture dish upside down and then edge of the dish was wiped with kim-wipe to wick away media left behind, and then 200 µl of ice-cold 0.4N perchloric acid was quickly added. Cell lysates were scraped and transferred to 1.5 ml tubes. Samples were incubated on ice for 5 minutes and centrifuged at 4°C for 2 minutes at maximum speed. Supernatant was transferred to new tubes and added 40 µl of 2.2 M KHCO3, and the pH of the samples were verified to be between the required range of pH 5–8. Samples were incubated on ice for 15 minutes and centrifuged at maximum speed for 5 minutes. Supernatants were transferred to new tubes and stored at −80°C until analysis. GTP was measured in the cell extracts using a coupled enzymatic assay as described previously60. Briefly, after depleting the extracts of ATP using firefly luciferase, GTP was converted to ATP using the enzyme nucleoside diphosphate kinase in the presence of excess ADP; the resultant ATP was measured by the firefly luciferase assay system. Because the second reaction generates light and is irreversible, the first reaction proceeds to completion. The assay is highly sensitive (to fmol amounts of GTP) and specific (no other nucleotides or deoxynucleotides interfere with the assay).

Gene expression analysis

mtp53 target gene expression was analyzed from a dataset of 537 breast cancer transcriptomes61. The dataset consist of 537 breast cancer tumor samples that were hybridized to Affymetrix U133-Plus2.0 arrays. CEL files were downloaded from the public ArrayExpress repository (accession # E-MTAB-365) and imported into GeneSpring GX 12.5 software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Microarray dataset was normalized using the Robust Multi-array Average (RMA) algorithm and the baseline adjusted to the median of all samples62. Only samples with reported p53 status (145 WT and 94 mutant) were analyzed for mtp53 target genes expression using t-test in log2 transformed expression data. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Kaplan-Meier analysis

To study the relationship between mtp53 target gene expression and relapse free survival (RFS) and distant metastasis free survival (DMFS) we perform Kaplan-Meier analysis using a dataset of 4142 breast cancer transcriptomes with clinical outcome data (version 2014)63 Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed dividing the patient cohort between samples in the upper quartile of expression for each particular gene and the rest of the samples. Analysis were performed using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter software (kmplot.com) using the default parameters. Results are expressed as a hazard ratio with 95% confidence intervals and log rank test P value. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

L.A.M. is supported by NCI CA166974-01A1. Flow cytometry experiments were performed at the UMMC Cancer Institute Flow Cytometry Core facility. We thank Dr. Sibali Bandyopadhyay for assistance with Flow Cytometry Analysis. We thank Beverly Mitchell for providing the DCK promoter luciferase construct.

Footnotes

Authors Contributions

M.K. and L.A.M designed research. M.K performed the majority of the work and L.A.M, Z.I.C., K.M.C., G.R., and K.W. assisted. E.D, T.C. and C.G.R. performed the dNTP analysis. A.C. and G.R.B performed the rNTP analysis. D.G.R. analyzed the patient data sets. M.K. and L.A.M analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. K.C.V assisted in the in vivo metastasis study.

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matoba S, Kang JG, Patino WD, Wragg A, Boehm M, Gavrilova O, et al. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science (New York, NY. 2006;312(5780):1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1126863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, Vidal MN, Nakano K, Bartrons R, et al. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126(1):107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang P, Du W, Wang X, Mancuso A, Gao X, Wu M, et al. p53 regulates biosynthesis through direct inactivation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Nature cell biology. 2011;13(3):310–316. doi: 10.1038/ncb2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang C, Lin M, Wu R, Wang X, Yang B, Levine AJ, et al. Parkin, a p53 target gene, mediates the role of p53 in glucose metabolism and the Warburg effect. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(39):16259–16264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113884108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine AJ, Feng Z, Mak TW, You H, Jin S. Coordination and communication between the p53 and IGF-1-AKT-TOR signal transduction pathways. Genes & development. 2006;20(3):267–275. doi: 10.1101/gad.1363206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu W, Zhang C, Wu R, Sun Y, Levine A, Feng Z. Glutaminase 2, a novel p53 target gene regulating energy metabolism and antioxidant function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(16):7455–7460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001006107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki S, Tanaka T, Poyurovsky MV, Nagano H, Mayama T, Ohkubo S, et al. Phosphate-activated glutaminase (GLS2), a p53-inducible regulator of glutamine metabolism and reactive oxygen species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;107(16):7461–7466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002459107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assaily W, Rubinger DA, Wheaton K, Lin Y, Ma W, Xuan W, et al. ROS-mediated p53 induction of Lpin1 regulates fatty acid oxidation in response to nutritional stress. Molecular cell. 2011;44(3):491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buzzai M, Jones RG, Amaravadi RK, Lum JJ, DeBerardinis RJ, Zhao F, et al. Systemic treatment with the antidiabetic drug metformin selectively impairs p53-deficient tumor cell growth. Cancer research. 2007;67(14):6745–6752. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budanov AV, Sablina AA, Feinstein E, Koonin EV, Chumakov PM. Regeneration of peroxiredoxins by p53-regulated sestrins, homologs of bacterial AhpD. Science (New York, NY. 2004;304(5670):596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1095569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sablina AA, Budanov AV, Ilyinskaya GV, Agapova LS, Kravchenko JE, Chumakov PM. The antioxidant function of the p53 tumor suppressor. Nature medicine. 2005;11(12):1306–1313. doi: 10.1038/nm1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon KA, Nakamura Y, Arakawa H. Identification of ALDH4 as a p53-inducible gene and its protective role in cellular stresses. Journal of human genetics. 2004;49(3):134–140. doi: 10.1007/s10038-003-0122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan M, Li S, Swaroop M, Guan K, Oberley LW, Sun Y. Transcriptional activation of the human glutathione peroxidase promoter by p53. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274(17):12061–12066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang SJ, Yu G, Jiang L, Li T, Lin Q, Tang Y, et al. p53-Dependent regulation of metabolic function through transcriptional activation of pantothenate kinase-1 gene. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex. 2013;12(5):753–761. doi: 10.4161/cc.23597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller PA, Vousden KH. Mutant p53 in cancer: new functions and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer cell. 2014;25(3):304–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong S, Tu H, Kollareddy M, Pant V, Li Q, Zhang Y, et al. Pla2g16 phospholipase mediates gain-of-function activities of mutant p53. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(30):11145–11150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404139111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Do PM, Varanasi L, Fan S, Li C, Kubacka I, Newman V, et al. Mutant p53 cooperates with ETS2 to promote etoposide resistance. Genes & development. 2012;26(8):830–845. doi: 10.1101/gad.181685.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girardini JE, Napoli M, Piazza S, Rustighi A, Marotta C, Radaelli E, et al. A Pin1/mutant p53 axis promotes aggressiveness in breast cancer. Cancer cell. 2011;20(1):79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freed-Pastor WA, Mizuno H, Zhao X, Langerod A, Moon SH, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, et al. Mutant p53 disrupts mammary tissue architecture via the mevalonate pathway. Cell. 2012;148(1–2):244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampath J, Sun D, Kidd VJ, Grenet J, Gandhi A, Shapiro LH, et al. Mutant p53 cooperates with ETS and selectively up-regulates human MDR1 not MRP1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276(42):39359–39367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Agostino S, Strano S, Emiliozzi V, Zerbini V, Mottolese M, Sacchi A, et al. Gain of function of mutant p53: the mutant p53/NF-Y protein complex reveals an aberrant transcriptional mechanism of cell cycle regulation. Cancer cell. 2006;10(3):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stambolsky P, Tabach Y, Fontemaggi G, Weisz L, Maor-Aloni R, Siegfried Z, et al. Modulation of the vitamin D3 response by cancer-associated mutant p53. Cancer cell. 2010;17(3):273–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li D, Yallowitz A, Ozog L, Marchenko N. A gain-of-function mutant p53-HSF1 feed forward circuit governs adaptation of cancer cells to proteotoxic stress. Cell death & disease. 2014;5:e1194. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalo E, Kogan-Sakin I, Solomon H, Bar-Nathan E, Shay M, Shetzer Y, et al. Mutant p53R273H attenuates the expression of phase 2 detoxifying enzymes and promotes the survival of cells with high levels of reactive oxygen species. Journal of cell science. 2012;125(Pt 22):5578–5586. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang C, Liu J, Liang Y, Wu R, Zhao Y, Hong X, et al. Tumour-associated mutant p53 drives the Warburg effect. Nature communications. 2013;4:2935. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chavez-Perez VA, Strasberg-Rieber M, Rieber M. Metabolic utilization of exogenous pyruvate by mutant p53 (R175H) human melanoma cells promotes survival under glucose depletion. Cancer biology & therapy. 2011;12(7):647–656. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.7.16566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu YC, Li F, Handler J, Huang CR, Xiang Y, Neretti N, et al. Global regulation of nucleotide biosynthetic genes by c-Myc. PloS one. 2008;3(7):e2722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham JT, Moreno MV, Lodi A, Ronen SM, Ruggero D. Protein and nucleotide biosynthesis are coupled by a single rate-limiting enzyme, PRPS2, to drive cancer. Cell. 157(5):1088–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mannava S, Grachtchouk V, Wheeler LJ, Im M, Zhuang D, Slavina EG, et al. Direct role of nucleotide metabolism in C-MYC-dependent proliferation of melanoma cells. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex. 2008;7(15):2392–2400. doi: 10.4161/cc.6390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angus SP, Wheeler LJ, Ranmal SA, Zhang X, Markey MP, Mathews CK, et al. Retinoblastoma tumor suppressor targets dNTP metabolism to regulate DNA replication. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277(46):44376–44384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wawrzyniak JA, Bianchi-Smiraglia A, Bshara W, Mannava S, Ackroyd J, Bagati A, et al. A purine nucleotide biosynthesis enzyme guanosine monophosphate reductase is a suppressor of melanoma invasion. Cell reports. 2013;5(2):493–507. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakano K, Balint E, Ashcroft M, Vousden KH. A ribonucleotide reductase gene is a transcriptional target of p53 and p73. Oncogene. 2000;19(37):4283–4289. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka H, Arakawa H, Yamaguchi T, Shiraishi K, Fukuda S, Matsui K, et al. A ribonucleotide reductase gene involved in a p53-dependent cell-cycle checkpoint for DNA damage. Nature. 2000;404(6773):42–49. doi: 10.1038/35003506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mondin M, Moreau V, Genot E, Combe C, Ripoche J, Dubus I. Alterations in cytoskeletal protein expression by mycophenolic acid in human mesangial cells requires Rac inactivation. Biochemical pharmacology. 2007;73(9):1491–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ji Y, Gu J, Makhov AM, Griffith JD, Mitchell BS. Regulation of the interaction of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase with mycophenolic Acid by GTP. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281(1):206–212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, Drobnjak M, Kakonen SM, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer cell. 2003;3(6):537–549. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bos PD, Zhang XH, Nadal C, Shu W, Gomis RR, Nguyen DX, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to the brain. Nature. 2009;459(7249):1005–1009. doi: 10.1038/nature08021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergman AM, Pinedo HM, Peters GJ. Determinants of resistance to 2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine (gemcitabine) Drug Resist Updat. 2002;5(1):19–33. doi: 10.1016/s1368-7646(02)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geutjes EJ, Tian S, Roepman P, Bernards R. Deoxycytidine kinase is overexpressed in poor outcome breast cancer and determines responsiveness to nucleoside analogs. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012;131(3):809–818. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1477-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saiki Y, Yoshino Y, Fujimura H, Manabe T, Kudo Y, Shimada M, et al. DCK is frequently inactivated in acquired gemcitabine-resistant human cancer cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012;421(1):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Braas D, Ahler E, Tam B, Nathanson D, Riedinger M, Benz MR, et al. Metabolomics strategy reveals subpopulation of liposarcomas sensitive to gemcitabine treatment. Cancer discovery. 2012;2(12):1109–1117. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi O, Heathcote DA, Ho KK, Muller PJ, Ghani H, Lam EW, et al. A deficiency in nucleoside salvage impairs murine lymphocyte development, homeostasis, and survival. J Immunol. 2012;188(8):3920–3927. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Austin WR, Armijo AL, Campbell DO, Singh AS, Hsieh T, Nathanson D, et al. Nucleoside salvage pathway kinases regulate hematopoiesis by linking nucleotide metabolism with replication stress. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209(12):2215–2228. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nathanson DA, Armijo AL, Tom M, Li Z, Dimitrova E, Austin WR, et al. Co-targeting of convergent nucleotide biosynthetic pathways for leukemia eradication. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211(3):473–486. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bjursell G, Reichard P. Effects of thymidine on deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate pools and deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in Chinese hamster ovary cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1973;248(11):3904–3909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larsson KM, Jordan A, Eliasson R, Reichard P, Logan DT, Nordlund P. Structural mechanism of allosteric substrate specificity regulation in a ribonucleotide reductase. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2004;11(11):1142–1149. doi: 10.1038/nsmb838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van't Veer LJ, Dai H, Hart AA, Voskuil DW, et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;347(25):1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furuta E, Okuda H, Kobayashi A, Watabe K. Metabolic genes in cancer: their roles in tumor progression and clinical implications. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2010;1805(2):141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanel W, Marchenko N, Xu S, Yu SX, Weng W, Moll U. Two hot spot mutant p53 mouse models display differential gain of function in tumorigenesis. Cell death and differentiation. 20(7):898–909. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lang GA, Iwakuma T, Suh YA, Liu G, Rao VA, Parant JM, et al. Gain of function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119(6):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Ruhe ZC, Yin B, Willis NA, Bronson RT, et al. Mutant p53 gain of function in two mouse models of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119(6):847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu DP, Song H, Xu Y. A common gain of function of p53 cancer mutants in inducing genetic instability. Oncogene. 2010;29(7):949–956. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song H, Hollstein M, Xu Y. p53 gain-of-function cancer mutants induce genetic instability by inactivating ATM. Nature cell biology. 2007;9(5):573–580. doi: 10.1038/ncb1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee MK, Teoh WW, Phang BH, Tong WM, Wang ZQ, Sabapathy K. Cell-type, dose, and mutation-type specificity dictate mutant p53 functions in vivo. Cancer cell. 2012;22(6):751–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marin MC, Jost CA, Brooks LA, Irwin MS, O'Nions J, Tidy JA, et al. A common polymorphism acts as an intragenic modifier of mutant p53 behaviour. Nature genetics. 2000;25(1):47–54. doi: 10.1038/75586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bergamaschi D, Gasco M, Hiller L, Sullivan A, Syed N, Trigiante G, et al. p53 polymorphism influences response in cancer chemotherapy via modulation of p73-dependent apoptosis. Cancer cell. 2003;3(4):387–402. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coffill CR, Muller PA, Oh HK, Neo SP, Hogue KA, Cheok CF, et al. Mutant p53 interactome identifies nardilysin as a p53R273H-specific binding partner that promotes invasion. EMBO reports. 13(7):638–644. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu J, Reumers J, Couceiro JR, De Smet F, Gallardo R, Rudyak S, et al. Gain of function of mutant p53 by coaggregation with multiple tumor suppressors. Nature chemical biology. 2011;7(5):285–295. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freed-Pastor WA, Prives C. Mutant p53: one name, many proteins. Genes & development. 2012;26(12):1268–1286. doi: 10.1101/gad.190678.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Egawa K, Sharma PM, Nakashima N, Huang Y, Huver E, Boss GR, et al. Membrane-targeted phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mimics insulin actions and induces a state of cellular insulin resistance. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274(20):14306–14314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guedj M, Marisa L, de Reynies A, Orsetti B, Schiappa R, Bibeau F, et al. A refined molecular taxonomy of breast cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31(9):1196–1206. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics (Oxford, England) 2003;4(2):249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert C, Budczies J, Li Q, et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2010;123(3):725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.