Randomized controlled trials investigating ultrasound surveillance of individuals at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma have reported improved survival and cost benefits. However, its sensitivity in North American settings has been questioned, especially in cases in which patient size may limit sound transmission. The authors of this study aimed to determine whether ultrasound surveillance was as effective as the primary surveillance tools currently in use and, additionally, to identify possible patient-, liver- or tumour-related factors associated with surveillance success.

Keywords: Canada, Effectiveness, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Surveillance, Ultrasound

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The effectiveness of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) using ultrasound (US) in North America has been questioned due to the predominance of patients of Caucasian ethnicity and larger body habitus.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the effectiveness of US surveillance for HCC in a Canadian hepatobiliary centre and to identify independent variables associated with early detection of tumour(s).

METHODS:

A retrospective review of patients with first HCC in a US surveillance population at the authors’ hospital yielded 201 patients (over a 10.5-year period). Patients were categorized into three groups: regular surveillance (frequency of surveillance ≤12 months [n=109]); irregular surveillance (frequency of surveillance >12 months [n=38]); or first surveillance (tumour detected on first scan [n=54]). The Milan criteria for transplantation and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system were used as outcome measures. Effective surveillance was defined as tumour detection within Milan criteria or curative BCLC stages 0 and A; its association with multiple patient- and disease-related variables was tested.

RESULTS:

When using the Milan criteria as outcome, 84 of 109 (77%) regular surveillance patients, 23 of 38 (61%) irregular surveillance patients and 40 of 54 (74%) first surveillance patients had tumours meeting the transplantation criteria. The difference between regular and irregular surveillance was statistically significant (P=0.03). When using the BCLC staging system, 87 of 109 (80%) regular surveillance patients, 26 of 38 (68%) irregular surveillance patients and 41 of 54 (76%) first surveillance patients had their tumours detected in BCLC curative stages (0 and A; P=0.11). Regular surveillance was the only variable significantly associated with detection of tumour(s) within the Milan criteria (OR 2.76 [95% CI 1.10 to 6.88]). Tumours detected more recently were more likely to be <2 cm in size (BCLC stage 0; OR 2.38 [95% CI 1.07 to 5.31]).

CONCLUSION:

A high rate of HCC surveillance success was achieved using US alone when performed regularly in a specialized hepatobiliary centre.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

L’efficacité de la surveillance du carcinome hépatocellulaire (CHC) par échographie (ÉG) en Amérique du Nord a été remise en question en raison de la prédominance de patients de race blanche d’un type morphologique plus imposant.

OBJECTIF :

Déterminer l’efficacité de la surveillance ÉG du CHC dans un centre hépatobiliaire canadien et les variables indépendantes associées à la détection précoce des tumeurs.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Une analyse rétrospective des patients ayant un premier CHC dans une population sous surveillance ÉG à l’hôpital des auteurs a révélé 201 patients atteints (sur une période de 10,5 ans). Les patients ont été classés en trois groupes : surveillance régulière (fréquence de la surveillance ≤12 mois [n=109]), surveillance irrégulière (fréquence de la surveillance >12 mois [n=38]) ou première surveillance (tumeur décelée à la première ÉG [n=54]). Les chercheurs ont utilisé les mesures de résultats suivantes : critères de Milan pour la transplantation et la classification de la clinique pour le cancer du foie de Barcelone (acronyme BCLC en anglais). Ils ont défini une surveillance efficace comme la détection de tumeurs conformément aux critères de Milan ou à la classification BCLC aux stades curatifs 0 et A. Ils en ont vérifié l’association avec des variables pathologiques touchant de multiples patients.

RÉSULTATS :

Lorsque les critères de Milan servent de mesure de résultat, 84 des 109 patients sous surveillance régulière (77 %), 23 des 38 patients sous surveillance irrégulière (61 %) et 40 des 54 patients sous première surveillance (74 %) avaient des tumeurs respectant les critères de transplantation. La différence entre une surveillance régulière et irrégulière était statistiquement significative (P=0,03). Lorsqu’on utilise les stades de classification BCLC, 87 des 109 patients sous surveillance régulière (80 %), 26 des 38 patients sous surveillance irrégulière (68 %) et 41 des 54 patients sous première surveillance (76 %) se sont fait déceler une tumeur aux stades curatifs de la classification BCLC (0 et A; P=0,11). La surveillance régulière était la seule variable associée de manière significative à la détection des tumeurs selon les critères de Milan (RC 2,76 [95 % IC 1,10 à 6,88]). Les tumeurs décelées plus récemment étaient plus susceptibles d’être de dimension inférieure à 2 cm (stade de BCLC 0; RC 2,38 [95 % IC 1,07 à 5,31]).

CONCLUSION :

L’ÉG seule s’associait à un taux élevé de réussite de la surveillance du CHC lorsqu’elle était effectuée régulièrement dans un centre hépatobiliaire spécialisé.

Surveillance of populations at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) using ultrasound (US) has been suggested to improve survival in a randomized controlled trial, is cost effective, and is recommended by American and international associations dedicated to the study of liver disease (1–5). It is, nevertheless, an imperfect test and its effectiveness has been questioned in the North American setting, in which patient size may limit sound transmission (6,7). The method of HCC surveillance in North America is variable, with serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also being used as primary surveillance tools (8,9).

Approximately 3000 patients undergo active HCC surveillance in our combined hospitals. We aimed to determine the proportion of patients whose tumour was detected at a potentially curable stage using US surveillance alone. Furthermore, we wanted to know whether there were any patient-, liver- or tumour-related factors that were associated with success of surveillance (ie, was the detection of the tumour in a curative stage). The aim of the present study was, therefore, twofold: to determine the effectiveness of US surveillance for HCC in a specialized Canadian liver disease centre; and to determine independent variables that were associated with success of surveillance.

METHODS

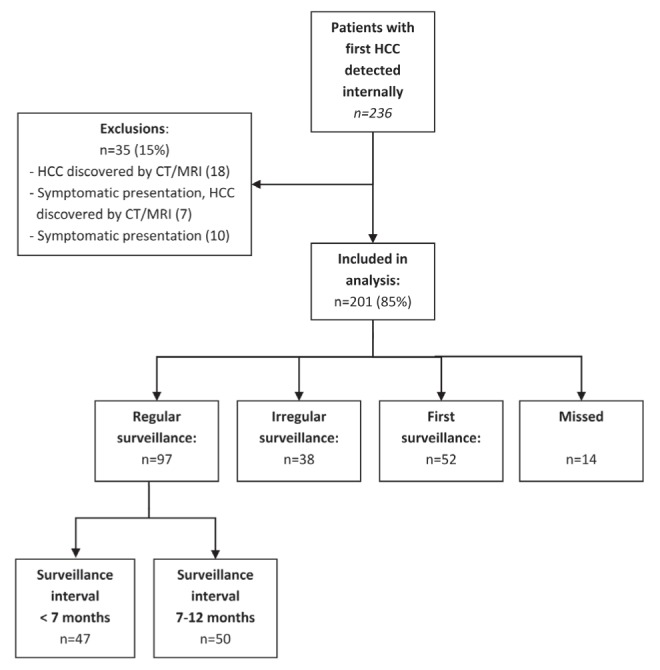

The present study was approved by the institution’s research ethics board and informed consent was waived. Electronic patient charts, available at one of the surveillance centres (Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, Ontario), were retrospectively reviewed to identify all 236 patients with a new diagnosis of HCC between January 2000 and June 2010, and whose tumour was discovered first at the authors’ centre. Patients who presented symptomatically or whose tumour was found using other modes of imaging were excluded (Figure 1). The reasons for other modes of imaging were: long-term follow-up of a different, ultimately benign nodule detected by US surveillance (10); symptomatic presentation (7); imaging for unrelated disease (5); surveillance by CT for previous HCC >2 years from the original tumour (3).

Figure 1).

Patient population. CT Computed tomography; HCC Hepatocellular carcinoma; MRI Magnetic resonance imaging

A total of 201 patients were included in the analysis; their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The diagnosis of HCC was confirmed for all patients using the following criteria: updated American Association for Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) HCC management guidelines’ imaging diagnostic criteria of one positive contrast-enhanced imaging scan in at-risk patients; positive histopathology from core biopsy or explant specimens; or recurrence of tumour after treatment (3). All relevant imaging was directly and retrospectively reviewed by a fellowship-trained abdominal imager with expertise in hepatobiliary imaging (12 years of practice) to ensure compliance with the latest imaging criteria and to confirm staging. The reviewer was blinded to the surveillance intervals.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics (n=201)

| Age, years | |

| Mean ± SD | 62.3±10.3 |

| Median (range) | 61 (31–86) |

| Male sex | 159 (79) |

| Ethnicity | |

| African | 7 (4) |

| Asian, East/Southeast | 49 (24) |

| Asian, South | 10 (5) |

| Caribbean | 2 (1) |

| Caucasian | 125 (62) |

| Latin American | 3 (2) |

| Middle Eastern | 5 (3) |

| Cause of liver disease | |

| Hepatitis C | 97 (48) |

| Hepatitis B | 42 (21) |

| More than one cause | 30 (15) |

| Alcohol | 19 (9) |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 8 (4) |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 2 (1) |

| Alagille syndrome | 1 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 1 |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome | 1 |

| Child-Pugh score | |

| 0 (not cirrhotic) | 2 (1) |

| A | 142 (71) |

| B | 48 (24) |

| C | 9 (5) |

| Surveillance intervals | |

| First scan detection | 54 (23) |

| <7 months | 59 (25) |

| 7–12 months | 50 (21) |

| 13–24 months | 23 (10) |

| >24 months | 15 (6) |

| BCLC stage | |

| 0 | 62 (31) |

| A | 104 (52) |

| B | 16 (8) |

| C | 12 (6) |

| D | 7 (3) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

Determining effectiveness

The Milan criteria for treatment of HCC by transplantation was used as an outcome measure with successful US surveillance defined as fulfilling the criteria of one nodule <5 cm in size, or three nodules <3 cm in size, with no vascular invasion or distant metastases (10). The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging classification was also used as an additional outcome measure (11). Successful surveillance was defined as detection of tumour using US in potentially curative stages 0 (one nodule <2 cm) or A (one resectable nodule of any size or three nodules <3 cm) of disease. Failure was defined as presentation in the palliative stages B to D.

For each patient, reports and images of all US scans were reviewed to determine the date of the earliest positive surveillance US of a nodule. This scan was noted as the ‘detection scan’ and was used to determine tumour stage. If a nodule ≥1 cm had been detected by a surveillance US but followed by imaging and subsequently proven to be malignant, the tumour stage at the time of the original detection scan, rather than at time of proof of malignancy, was used. The surveillance US images were reviewed to ensure that the nodule(s) detected corresponded to that characterized as malignant on contrast-enhanced imaging; if it did not, the malignant nodule was designated either as ‘missed’ by surveillance (if within three months of the surveillance US) or detected by other means and excluded (if ≥3 months of the surveillance US). Nodules <1 cm were not examined for the purposes of the present study because these were conventionally followed (3).

Missed tumours

If a surveillance US was negative and a HCC was detected within three months by other means (imaging or AFP, including a repeat US scan), it was defined as ‘missed’ by surveillance. Three months was used as a cut-off because a fast-growing malignant tumour may be truly undetectable on one surveillance image but present on the next. ‘Missed’ nodules were omitted from statistical analysis of effectiveness of surveillance (above) and also of potential determinants of successful surveillance (below) because it would not be possible to determine what proportion of these would be detected by next surveillance US still in a curable stage.

The contribution of AFP

The charts of all patients were reviewed and level and dates of serum AFP measurements were recorded. Only measurements within 90 days of the final surveillance US were included (from 90 days before to 90 days after). If multiple measurements were available before the last surveillance scan, then the highest level was used. If multiple measurements were available after the detection of tumour, the closest measurement to the date of US was used. An AFP level >20 mg/mL was defined as positive.

Potential determinants of successful surveillance

For the present analysis, patients whose tumours were detected on the first surveillance US scan were omitted because theirs were representative of a screening (prevalence) and not of a surveillance (incidence) population. On the first surveillance scan, a tumour may be detected in the advanced stage just for the reason that there was no previous surveillance. On subsequent surveillance scans, a tumour may be detected in an advanced stage due to patient- or tumour-related variables that led to failure of surveillance.

The following variables were tested for an association with successful surveillance: age, sex, ethnicity, cause of liver disease, severity of liver disease, year of detection, location of residence and surveillance frequency. Due to the limited size of the study population, variables were broadly grouped where appropriate. Ethnicity was divided into two groups of Caucasian (European descent) and others (including East/Southeast Asian, African, Middle-Eastern, South-Asian, Caribbean and Latin American). Causes of liver disease included chronic hepatitis B virus infection, chronic hepatitis C virus infection, other causes and multiple causes (ie, patients with more than one cause of disease). This latter category (multiple causes) was created because these patients are more likely to be closely followed and screened. The Child-Pugh score was used for severity of liver disease, with noncirrhotic patients grouped with Child’s A versus patients with Child’s B and C scores. Year of detection was divided into two groups of 2000 to 2005 and 2006 to 2010, to determine the effect of implementation of the first AASLD HCC guidelines in 2005 in addition to installation of the latest generation of scanners at the authors’ institution in 2006. Patients were divided based on their residence into metropolitan (greater Toronto area) versus beyond metropolitan groups to determine whether there was a difference in urban versus rural populations. Finally, surveillance frequency was grouped into ≤12 months (regular) and >12 months (irregular). The authors acknowledge that a six-month surveillance interval is the standard of care; however, because the present study covers a substantial period before publication of the AASLD guidelines in 2005, 12-month follow-up interval may still have been considered to be appropriate by some clinicians. Therefore, for the sake of consistent terminology, both within the present study and with other studies that cover a similar period of examination (9), frequency of ≤12 months has been defined as ‘regular surveillance’.

Statistical methods

A two-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used to compare effectiveness between regular and irregular surveillance groups. χ2 analysis, t test (for age) and unadjusted logistic regression were used to identify potential determinants of successful surveillance. Patients’ region of residence were derived using the Postal Code Conversion File + Version 5 (12). Postal Code Conversion File + Version 5 is a series of files created by Statistics Canada based on the most recent Canadian census data and assigns geographical identifiers based on postal codes. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a significant association. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, USA) and SPSS version 17.0 (IBM Corporation, USA) for Windows (Microsoft Corporation, USA).

RESULTS

Effectiveness of US surveillance

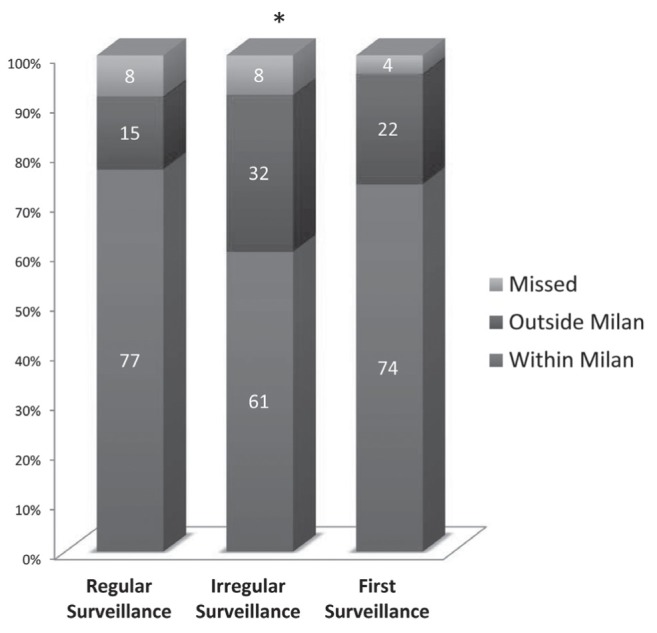

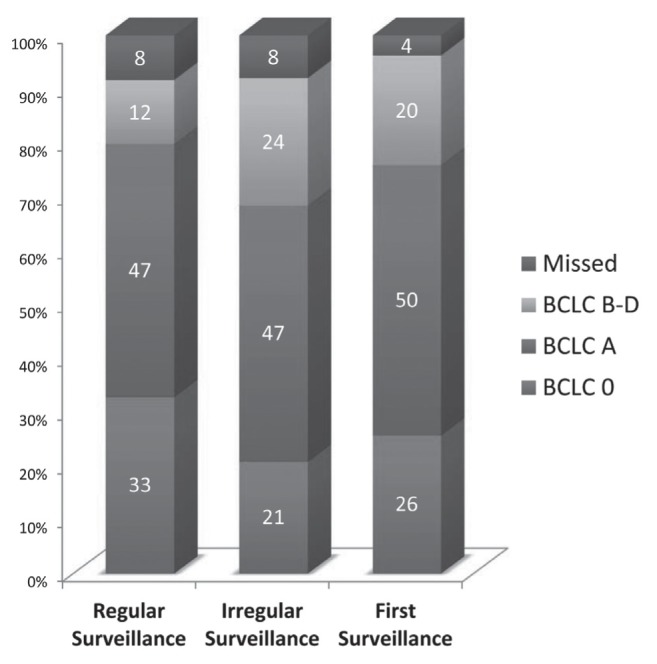

The stage of tumour at detection by US using end points of Milan criteria and BCLC staging system are listed in Tables 2 and 3, and graphically depicted in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. Seventy-seven percent of tumours were discovered within the Milan criteria through regular US surveillance. Similarly, 80% of patients undergoing regular surveillance had their tumour detected by US in BCLC curative stages of 0 (33%) and A (47%).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of surveillance interval using Milan criteria for liver transplantation

| Surveillance | Total, n | Milan criteria | Missed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Within | Outside | |||

| Regular* | 109 | 84 (77) | 16 (15) | 9 (8) |

| Irregular† | 38 | 23 (61) | 12 (32) | 3 (8) |

| First | 54 | 40 (74) | 12 (22) | 2 (4) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Surveillance intervals ≤12 months;

Surveillance intervals >12 months

TABLE 3.

Comparison of surveillance interval and tumour stage determined using the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system

| Surveillance | Total, n | BCLC stage | Missed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 0 | A | B to D | |||

| Regular* | 109 | 36 (33) | 51 (47) | 13 (12) | 9 (8) |

| Irregular† | 38 | 8 (21) | 18 (47) | 9 (24) | 3 (8) |

| First | 54 | 14 (26) | 27 (50) | 11 (20) | 2 (4) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Frequency of surveillance ≤12 months;

Frequency of surveillance >12 months

Figure 2).

Hepatocellular carcinoma ultrasound intervals according to Milan criteria for liver transplantation. *Indicates statistically significant difference in distribution between regular surveillance (frequency ≤12 months) and irregular (frequency >12 months) surveillance intervals (P=0.03)

Figure 3).

Hepatocellular carcinoma ultrasound intervals according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system. Regular surveillance: frequency ≤12 months; Irregular surveillance: frequency >12 months

When comparing the proportion of patients within and outside the Milan criteria for transplantation, there was a statistically significant difference between patients undergoing regular surveillance versus those undergoing irregular surveillance (P=0.03). The difference between regular and irregular surveillance did not reach significance when using the BCLC staging system as the end point (P=0.11).

Missed tumours

Of the 201 patients undergoing US surveillance who developed HCC, 14 (7%) had their tumour missed by surveillance US but detected through other means (six by CT, four by a second US and four by AFP) within three months of surveillance. The repeat US were all for unrelated reasons. Thirteen of the patients had a single HCC, and one had three HCCs. The median size of missed tumours was 2.4 cm (range 0.8 cm to 7.8 cm). The BCLC stage of the missed tumours were stage 0 (four of 14 [29%]), stage A (eight of 14 [57%]) and stage C (two of 14 [14%]).

Role of AFP

Of the 201 patients undergoing US surveillance, 129 (64%) had serum AFP levels measured within 180 days of US (from 90 days before to 90 days after). Of these 129 patients, 69 (53%) had serum AFP measured before or on the same day as the surveillance US. Only 26 of 69 (38%) of these measurements were performed after 2005 (AASLD guidelines published) and some may have been performed on the same day as the US scan due to a positive US.

The results of serology are shown in Table 4. The overall sensitivity of AFP detection of tumour within Milan criteria was 32% using a threshold of 20 ng/mL. AFP was able to detect tumour within three months of a negative surveillance US (ie, missed) in four patients, all of whom were undergoing regular surveillance. Because 70 of 129 patients with available serum AFP were undergoing regular US surveillance, the addition of AFP resulted in detection of HCC in four of 70 (6%) of patients undergoing regular US surveillance.

TABLE 4.

Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels in hepatocellular carcinomas within and outside Milan criteria for liver transplantation

| AFP, ng/mL | Milan criteria, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Within | Outside | |

| <20 | 67 (68) | 8 (27) |

| 20–199 | 23 (23) | 10 (33) |

| 200–400 | 6 (6) | 4 (13) |

| >400 | 3 (3) | 8 (27) |

Potential determinants of success of surveillance by US

The results of univariate analysis using Milan transplantation criteria are summarized in Table 5. Regular surveillance was the only statistically significant variable associated with detection of tumour meeting the Milan criteria (P=0.01). Because there were only 25 patients outside the Milan criteria, only two variables with the lowest P values (surveillance interval and age) were used in the multivariate analysis. Regular surveillance remained significantly associated with detection meeting Milan criteria (OR 2.76 [95% CI 1.10 to 6.88]).

TABLE 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of potential determinants of success of hepatocellular carcinoma ultrasound surveillance using Milan criteria for liver transplantation

| Milan criteria, n (%) | P | OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Outside (n=25) | Within (n=110) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 8 (32) | 21 (19) | 0.156 | 0.50 (0.19–1.32) | |

| Male | 17 (68) | 89 (81) | 1.00 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 16 (64) | 66 (60) | 0.712 | 1.00 | |

| Other | 9 (36) | 44 (40) | 1.19 (0.48–2.92) | ||

| Surveillance interval | |||||

| ≤12 | 13 (52) | 84 (76) | 0.014 | 2.98 (1.21–7.33) | 2.76 (1.10–6.88) |

| >12 | 12 (48) | 26 (24) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Cause(s) of hepatocellular carcinoma | |||||

| Hepatitis B | 4 (16) | 27 (25) | 0.806 | 1.88 (0.44–7.94) | |

| Hepatitis C | 12 (48) | 51 (46) | 1.18 (0.37–3.82) | ||

| Combined | 4 (16) | 14 (13) | 0.97 (0.22–4.31) | ||

| Other/unknown | 5 (20) | 18 (16) | 1.00 | ||

| Age, years | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 65.8±9.2 | 62.1±10.3 | 0.099* | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) |

| Median | 66 (50–86) | 61 (31–84) | |||

| Detection year | |||||

| 2000 to 2005 | 11 (44) | 45 (41) | 0.777 | 1.00 | |

| 2006 to 2010 | 14 (56) | 65 (59) | 1.14 (0.47–2.73) | ||

| Child-Pugh class | |||||

| A | 8 (32) | 28 (25) | 0.504 | 1.38 (0.54–3.54) | |

| B/C | 17 (68) | 82 (75) | 1.00 | ||

| Residence area | |||||

| Beyond metropolitan | 4 (16) | 18 (16) | 0.965 | 1.03 (0.32–3.35) | |

| Metropolitan area | 21 (84) | 92 (84) | 1.00 | ||

The results of univariate analysis using the BCLC staging system as the end point are summarized in Table 6. In none of the variables tested was there a statistically significant correlation with detection in the palliative stages of tumour (BCLC B to D). Table 7 shows the results when using BCLC stage 0 (ie, detection in very early stage of tumour [<2 cm] as an end point). Univariate analysis revealed that the year of detection (2000 to 2005 versus 2006 to 2010) was the only significant variable associated with discovery of tumour <2 cm (stage 0; P=0.02). In an adjusted multivariate analysis, tumours discovered after 2006 had a significantly higher probability of being in BCLC stage 0 (OR 2.38 [95% CI 1.07 to 5.31]).

TABLE 6.

Univariate analysis of potential determinants of success of hepatocellular cancer ultrasound surveillance in the detection of tumour in curable stages (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer [BCLC] stages 0 or A)

| BCLC stage | P | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| B/C/D (n=22) | 0/A (n=113) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 7 (32) | 22 (19) | 0.255 | 0.52 (0.19–1.42) |

| Male | 15 (68) | 91 (81) | 1.00 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 14 (64) | 68 (60) | 0.761 | 1.00 |

| Other | 8 (36) | 45 (40) | 1.16 (0.45–2.99) | |

| Surveillance interval, months | ||||

| ≤12 | 13 (59) | 84 (74) | 0.146 | 2.01 (0.78–5.18) |

| >12 | 9 (41) | 29 (26) | 1.00 | |

| Cause(s) | ||||

| Hepatitis B | 2 (9) | 29 (26) | 0.402 | 3.05 (0.51–18.34) |

| Hepatitis C | 12 (55) | 51 (45) | 0.90 (0.26–3.12) | |

| Combined | 4 (18) | 14 (12) | 0.74 (0.16–3.47) | |

| Other/unknown | 4 (18) | 19 (17) | 1.00 | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 65.8±9.2 | 62.2±10.3 | 0.125 | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) |

| Median (range) | 65 (50–86) | 61 (31–84) | ||

| Year of detection | ||||

| 2000–2005 | 10 (45) | 46 (41) | 0.679 | 1.00 |

| 2006–2010 | 12 (55) | 67 (59) | 1.21 (0.48–3.04) | |

| Child-Pugh class | ||||

| A | 9 (41) | 27 (24) | 0.099 | 2.21 (0.85–5.72) |

| B/C | 13 (59) | 86 (76) | 1.00 | |

| Residence area | ||||

| Beyond metropolitan | 3 (14) | 19 (17) | 0.770 | 1.28 (0.34–4.76) |

| Metropolitan | 19 (86) | 94 (83) | 1.00 | |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated

TABLE 7.

Univariate analysis of potential determinants of success of hepatocellular cancer ultrasound surveillance in the detection of tumour in very early stage (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer [BCLC] stage 0)

| Determinant | BCLC stage | P | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| A/B/C/D (n=91) | 0 (n=44) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 17 (19) | 12 (27) | 0.255 | 1.63 (0.70–3.81) | |

| Male | 74 (81) | 32 (73) | 1.00 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 55 (60) | 27 (61) | 0.918 | 1.00 | |

| Other | 36 (40) | 17 (39) | 0.96 (0.46–2.01) | ||

| Surveillance interval, months | |||||

| ≤12 | 62 (68) | 35 (80) | 0.167 | 1.82 (0.77–4.28) | 1.88 (0.77–4.61) |

| >12 | 29 (32) | 9 (20) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Cause(s) | |||||

| Hepatitis B | 21 (23) | 10 (23) | 0.142 | 3.18 (0.76–13.24) | 2.70 (0.63–11.64) |

| Hepatitis C | 38 (42) | 25 (57) | 4.39 (1.18–16.33) | 4.11 (1.07–15.79) | |

| Combined | 12 (13) | 6 (14) | 3.33 (0.70–15.86) | 2.93 (0.60–14.41) | |

| Other/unknown | 20 (22) | 3 (7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Age, years | |||||

| Mean | 63.2±10.0 | 61.8±10.6 | 0.441 | 0.99 (0.95–1.02) | |

| Median | 63 (31–86) | 60.5 (37–82) | |||

| Year of detection | |||||

| 2000–2005 | 44 (48) | 12 (27) | 0.020 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2006–2010 | 47 (52) | 32 (73) | 2.50 (1.14–5.45) | 2.38 (1.07–5.31) | |

| Child-Pugh class | |||||

| A | 26 (29) | 10 (23) | 0.472 | 1.36 (0.59–3.15) | |

| B/C | 65 (71) | 34 (77) | 1.00 | ||

| Residence area | |||||

| Beyond metropolitan | 14 (15) | 8 (18) | 0.680 | 1.22 (0.47–3.18) | |

| Metropolitan | 77 (85) | 36 | 1.00 | ||

Six-month versus 12-month surveillance strategy was not analyzed because the former may not have been considered to be the standard of care before publication of the AASLD guidelines in 2005. However, it was noted that of the 166 patients with a previous surveillance history, there was a small rise in the proportion of patients who underwent six-month surveillance after 2005 (38 of 87 [44%]) compared with 2005 and before (21 of 60 [35%]).

DISCUSSION

The present study showed that in a diverse Canadian population, regular US surveillance performed in a hepatobiliary centre resulted in detection of tumour in curative stages in at least 80% of patients. In addition, at least 77% of patients met the Milan criteria for liver transplantation. Furthermore, regular surveillance resulted in detection of tumour in the curable stages in a significantly higher proportion of patients than in irregular surveillance or screening (first surveillance) populations. In other words, regular surveillance for HCC resulted in stage migration. Tumours detected by other means within three months of negative US surveillance were designated as ‘missed’ in the present study because some of these would likely be detected within a curable range on a future surveillance scan; therefore, the true effectiveness of US in our centre is likely higher.

Our results show that US surveillance in North America is as effective as the best published rates. A recent meta-analysis of prospective studies assessing the effectiveness of US surveillance for HCC reported a combined sensitivity of 63% for detection of tumour within Milan criteria for transplantation (13). However, most studies used in this particular analysis were old, with only three of 12 study analyses performed in the past decade, and only one after 2006. Imaging technology is continually improving and important sonographic innovations, such as harmonic and compound imaging, have become part of standard-imaging US scanners over the past decade (14). A review of prospective and retrospective US surveillance studies with or without AFP published over the past two years show a sensitivity of 69% to 88% for detection of tumour within Milan criteria (15–19). Furthermore, detection of very early HCC (BCLC stage 0, <2 cm) is reported to be 8% to 43% (15–19). Our rates of 77% for detection of HCC within Milan criteria and 33% for detection of very early HCC are well within this reported range.

Regular surveillance was the only independent variable associated with detection of disease in early, curable stages. Regular surveillance increased the odds of detecting tumour within Milan criteria by a factor of 2.76 (95% CI 1.10 to 6.88). Just as importantly, there was no significant difference in sensitivity of US surveillance between Caucasian and non-Caucasian ethnicity. The present study was the first to directly demonstrate similar sensitivities within different ethnic groups; previously, this was inferred by comparing effectiveness rates published in Europe and Asia (1,3). Furthermore, a significantly higher proportion of tumours were detected in the very early BCLC stage of 0 (<2 cm) in the latter half of our study period; that is, from 2006 to 2010 than in 2000 to 2005 (P=0.02). This is an important finding because treatment of tumours <2 cm in size result in five-year survival rates of up to 90% (5). The reason for increased detection of smaller tumours in 2006 to 2010 may be because of improved US technology; all of our scanners were upgraded in 2006 to the latest generation of high-end equipment. It was also due to increased frequency of surveillance because the proportion of patients undergoing six-month surveillance intervals rose from 38% to 44% after the publication of the first HCC management guidelines from the AASLD (20).

In the present study, we used tumour stage at time of detection by US rather than tumour stage at time of treatment. This was done to assess US alone as a surveillance test in a Canadian setting. In a companion study involving the same cohort to assess effectiveness of our surveillance program compared with patients referred to our own institution, we used tumour stage at time of treatment (21). Occasionally, the surveillance test is effective in detection but the work-up strategy fails to diagnose a HCC as malignant. Sometimes a false-positive surveillance test for a benign nodule leads to incidental detection of a HCC by the work-up imaging (such as CT or MRI). Finally, some HCCs are detected on CT/MRI for patients undergoing follow-up imaging for indeterminate nodules detected elsewhere by surveillance US. These scenarios explain why, in the present study, in which US surveillance effectiveness was assessed, tumour stage is BCLC 0/A 83% (Table 1), whereas in our companion study, in which effectiveness of the comprehensive surveillance program was measured, it was 75%.

The present study demonstrates the limited role of serum AFP levels in a surveillance setting. Using a threshold of 20 ng/mL, AFP was able to detect 73% of tumours beyond Milan criteria, but only 32% of tumours within Milan. More importantly, in only 6% of patients did AFP detect a tumour when US was negative. The present study demonstrates that when US is performed effectively, most tumours are detected before reaching a differentiation sufficiently advanced, or a volume sufficiently large, to produce even a low threshold of AFP. The present study supports the AASLD recommendation of elimination of AFP in the setting of regular US surveillance (3). We hope that this result further promotes the abandonment of AFP as a surveillance test, because even in our own practice, we have found multiple examples of noncompliance with the AASLD guidelines in this regard.

Studies that assess clinical performance of US in HCC surveillance demonstrate acceptable sensitivity (15–19). However, studies that assess sensitivity of US with explant correlation show an unacceptably low performance, leading some to advocate its replacement by CT or MRI (7,22). Why the discrepancy? First, the per-patient sensitivity – rather than per-lesion sensitivity – is relevant to US surveillance because all patients with positive US undergo CT or MRI, in which additional nodules can be detected. Second, the assumption with explant correlation studies is that every HCC is significant and, therefore, its detection affects patient survival. However, this is a faulty assumption; it is tumour biology – rather than its mere presence – that affects patient survival (23). Multiple studies have shown that markers of aggressive tumour behaviour, such as poor histological differentiation, serum AFP, vascular invasion and tumour size are all stronger predictors of poor survival outcomes (23–26). The fact that multiple proposed expansions of the Milan criteria for transplantation allows for inclusion of additional tumours is a reflection of the relative lower clinical significant of tumour number (27). Finally, the slow growth rate of early HCC allows for multiple chances for US to detect a nodule; repeated application of the test improves its overall sensitivity.

Strengths and limitations

The present study was the first to investigate HCC surveillance effectiveness using US in Canadian patients with HCC. A major strength was the direct correlation of tumour to the original surveillance scan. By anatomically reviewing the exact location of every HCC to the surveillance US, we ensured that every HCC was truly detected by the US or otherwise designated as missed. Furthermore, the stringent inclusion criteria for the diagnosis of HCC and staging through review of the imaging and clinical features ensured that every nodule included fulfilled current criteria for malignancy and staging systems. Moreover, we accounted for missed tumours that were found by other means. However, the retrospective nature of the present study subjects it to inherent bias. For example, HCCs detected by surveillance in our centre but characterized elsewhere could not be included because the imaging was not available for staging. Our study shows a stage migration through regular surveillance, but we cannot demonstrate a direct survival benefit. In addition, the sample size of 135 patients used for uni- and multivariate analyses limited our ability to demonstrate small but significant differences. Finally, our results are reflective of an academic US department in a hepatobiliary centre with the latest generation of scanners, uniformity of scanning standards, and with continual training for sonographers and direct physician supervision.

CONCLUSION

The present study showed that US surveillance, when regularly performed in expert centres, is an efficacious tool resulting in the detection of HCC in treatable stages in 80% of patients. It also shows no difference in performance of US surveillance in Caucasian versus other ethnic populations, thereby validating its use as the surveillance tool in North America. Finally, the exclusion of serum AFP from HCC surveillance is supported because it improves the detection rate by only 6%.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:439–74. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9165-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang BH, Yang BH, Tang ZY. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:417–22. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: An update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman M, Bain V, Villeneuve JP, et al. The management of chronic viral hepatitis: A Canadian consensus conference 2004. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:715–28. doi: 10.1155/2004/201031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singal AG, Conjeevaram HS, Volk ML, et al. Effectiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:793–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Federle MP. Use of radiologic techniques to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35(5 Suppl 2):S92–S100. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200211002-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkar M, Stewart S, Yu A, Chen MS, Nguyen TT, Khalili M. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening practices and impact on survival among hepatitis B-infected Asian Americans. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:594–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davila JA, Morgan RO, Richardson PA, Du XL, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB. Use of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology. 2010;52:132–41. doi: 10.1002/hep.23615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forner A, Hessheimer AJ, Isabel Real M, Bruix J. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;60:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postal code conversion file. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2011. Statistics Canada Geography Division. < www.easl.eu/research/our-contributions/clinical-practice-guidelines/detail/easl-eortc-clinical-practice-guidelines-management-of-hepatocellular-carcinoma/report/1> (Accessed January 2, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singal A, Volk ML, Waljee A, et al. Meta-analysis: Surveillance with ultrasound for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:37–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irshad A, Anis M, Ackerman SJ. Current role of ultrasound in chronic liver disease: Surveillance, diagnosis and management of hepatic neoplasms. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2012;41:43–51. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo YH, Lu SN, Chen CL, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance and appropriate treatment options improve survival for patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:744–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian MY, Yuwei JR, Angus P, Schelleman T, Johnson L, Gow P. Efficacy and cost of a hepatocellular carcinoma screening program at an Australian teaching hospital. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:951–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trinchet JC, Chaffaut C, Bourcier V, et al. Ultrasonographic surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: A randomized trial comparing 3- and 6-month periodicities. Hepatology. 2011;54:1987–97. doi: 10.1002/hep.24545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santi V, Trevisani F, Gramenzi A, et al. Semiannual surveillance is superior to annual surveillance for the detection of early hepatocellular carcinoma and patient survival. J Hepatol. 2010;53:291–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noda I, Kitamoto M, Nakahara H, et al. Regular surveillance by imaging for early detection and better prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients infected with hepatitis C virus. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:105–12. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalili K, Menezes R, Yazdi LK, et al. Hepatocellular carcioma in a large Canadian urban centre: Stage at treatment and its potential determinants. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:150–4. doi: 10.1155/2014/561732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taouli B, Krinsky GA. Diagnostic imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis before liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(11 Suppl 2):S1–7. doi: 10.1002/lt.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DuBay D, Sandroussi C, Sandhu L, et al. Liver transplantation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma using poor tumour differentiation on biopsy as an exclusion criterion. Ann Surg. 2011;253:166–72. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e31820508f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wai CT, Woon WA, Tan YM, Lee KH, Tan KC. Younger age and presence of macrovascular invasion were independent significant factors associated with poor disease-free survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:516–9. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marelli L, Grasso A, Pleguezuelo M, et al. Tumour size and differentiation in predicting recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: External validation of a new prognostic score. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3503–11. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grasso A, Stigliano R, Morisco F, et al. Liver transplantation and recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: Predictive value of nodule size in a retrospective and explant study. Transplantation. 2006;81:1532–41. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000209641.88912.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao FY. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Beyond the Milan criteria. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1982–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]