Abstract

Two mechanisms, suppression and enhancement, are proposed to improve referential access. Enhancement improves the accessibility of previously mentioned concepts by increasing or boosting their activation; suppression improves concepts’ accessibility by decreasing or dampening the activation of other concepts. Presumably, these mechanisms are triggered by the informational content of anaphors. Six experiments investigated this proposal by manipulating whether an anaphoric reference was made with a very explicit, repeated name anaphor or a less explicit pronoun. Subjects read sentences that introduced two participants in their first clauses, for example, “Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race,” and the sentences referred to one of the two participants in their second clauses, “but Pam/she came in first very easily.” While subjects read each sentence, the activation level of the two participants was measured by a probe verification task. The first two experiments demonstrated that explicit, repeated name anaphors immediately trigger the enhancement of their own antecedents and immediately trigger the suppression of other (nonantecedent) participants. The third experiment demonstrated that less explicit, pronoun anaphors also trigger the suppression of other nonantecedents, but they do so less quickly—even when, as in the fourth experiment, the semantic information to identify their antecedents occurs prior to the pronouns (e.g., “Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race. But after winning the race, she …”). The fifth experiment demonstrated that more explicit pronouns – pronouns that match the gender of only one participant—trigger suppression more powerfully. A final experiment demonstrated that it is not only rementioned participants who improve their referential access by triggering the suppression of other participants; newly introduced participants do so too (e.g., “Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race, but Kim …”). Thus, both suppression and enhancement improve referential access, and the contribution of these two mechanisms is a function of explicitness. The role of these two mechanisms in mediating other referential access phenomena is also discussed.

Comprehending a narrative requires knowing who’s doing what to whom. But how do comprehenders successfully track who or what is being referred to? Like all languages, English has a variety of devices for referring back to previously mentioned concepts. Such devices are called anaphors, and the concepts they refer back to are called antecedents. For example, to refer to the antecedent John in the sentence, “John went to the store,” one of several anaphoric devices could be used: a repeated noun phrase, such as John, a definite noun phrase, such as the guy, or a pronoun, such as he.

How language users negotiate anaphora has been the focus of a growing body of psycholinguistic research. Why has anaphora captured so much attention? One reason is that anaphors are very common linguistic devices. Consider only pronoun anaphors; in English, they are some of the most frequently occurring lexical units (Kučera & Francis, 1967).1 To study the comprehension of anaphors is, therefore, to study the comprehension of very common words.

Moreover, the process of understanding anaphors presents an interesting case of lexical access: Perhaps more than other lexical units, the meanings of some anaphors greatly depend on the context in which they occur. Consider the pronoun, it. Its meaning is constrained only to the extent that the concept be inanimate and singular;2 beyond that, it can take on a host of different meanings. For instance, in just the present paper, the lexical unit it has over 50 different antecedents. Some anaphors seem to be, in a sense, lexically transparent.

Despite the ubiquity and transparency of some anaphors, for each anaphor, a comprehender must access an appropriate antecedent; in other words, comprehenders must access each anaphor’s unique referent (Clark & Sengul, 1979; van Dijk & Kintsch, 1983). How does this happen?

Let us consider how a typical, nonanaphoric word is uniquely accessed. Commonly, this process is described in terms of activation (either in the traditional sense of individual nodes becoming activated or in the distributed sense in which a pattern of activation represents an individual word). During an initial recognition phase, information provided by the word activates various candidates. Then, during an identification phase, constraints provided by lexical, semantic, syntactic, and other sources of information alter the candidates’ levels of activation. Eventually, one candidate becomes most strongly activated. The most strongly activated candidate is the lexical representation that the comprehender can most easily access, and that is the representation which is incorporated into the comprehender’s developing discourse representation (these proposals are culled from the models of Becker, 1976; Kintsch & Mross, 1985; Marslen-Wilson & Welsch, 1978; McClelland & Rumelhart, 1981; Norris, 1986).

The process of comprehending anaphors could proceed similarly. This process has also been conceived of in terms of activation (Corbett & Chang, 1983; Dell, McKoon, & Ratcliff, 1983; McKoon & Ratcliff, 1980). Like the meaning of a word, the identity of an anaphor—its antecedent—is presumably the candidate representation that becomes the most strongly activated (Kintsch, 1988; Walker & Yekovich, 1987).3

Behavioral data support this proposal. Consider the following sentence:

-

(1)

Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race, but she came in first very easily.

The antecedent of the pronoun, she, is the participant, Pam; the other participant, Ann, is what I shall refer to as a nonantecedent. When activation is measured after comprehenders have finished reading this sentence, the pronoun’s antecedent, Pam, is indeed more activated than the nonantecedent, Ann (Corbett & Chang, 1983).

But how does an anaphor’s antecedent become the most activated concept? Two cognitive mechanisms might play a role in this process. These two mechanisms belong to a framework I have proposed that describes some general, cognitive processes involved in comprehension (Gernsbacher, 1985, 1989). According to the framework, the goal of comprehension is to build a coherent mental representation or “structure.” The two proposed mechanisms enable building these structures by moderating the activation of mental representations. One mechanism, enhancement, increases or boosts activation; the other mechanism, suppression, dampens or decreases activation. Although these mechanisms are considered general, cognitive mechanisms, they potentially play a role in many language comprehension phenomena.

For instance, I have suggested that the mechanism of suppression plays a role in how comprehenders disambiguate homographs. Immediately after comprehenders hear or read a homograph such as bug, multiple meanings are often activated—even when a particular meaning is specified by the preceding semantic context (e.g., “spiders, roaches, and other bugs,” Swinney, 1979), or the preceding syntactic context (e.g., “I like the watch” versus “I like to watch,” Tanenhaus, Leiman, & Seidenberg, 1979). However, after a quarter of a second, only the more appropriate meaning remains activated. What happens to the inappropriate meanings? One explanation is that a suppression mechanism, triggered by the semantic and syntactic context, decreases the less appropriate meanings’ activation (Gernsbacher, Varner, & Faust, 1989; Kintsch, 1988; Swinney, 1979).

The mechanism of suppression as well as enhancement might also play a role in how comprehenders access the appropriate antecedent for an anaphor. The role they play might be to improve an antecedent’s accessibility by modifying the activation levels of mental representations. Perhaps an antecedent becomes more accessible because it is enhanced, that is, its activation level is increased. Perhaps an antecedent also becomes more accessible because other concepts are suppressed. That is, a rementioned concept might rise to the top of the queue of potential referents because the activation levels of other concepts are decreased. So, enhancement might increase the antecedent’s activation, and suppression might decrease the activation of nonantecedents. The two mechanisms’ net effect would be that an anaphor’s antecedent would become substantially more activated than other concepts; therefore, the antecedent could be easily accessed and incorporated into the comprehender’s developing discourse structure. The experiments reported here examined this proposal.

But what triggers the mechanisms of suppression and enhancement? In the case of anaphoric reference, they are most likely triggered by information that specifies the antecedent’s identity. The most available source of such information is the anaphor itself. However, anaphors differ in how much information they provide about their antecedents. Some anaphors, such as repeated noun phrases, are very explicit; they match their antecedents exactly (e.g., “John went to the store. John bought a quart of milk.”). Other anaphors, such as the pronoun it, are less explicit; they often match several potential antecedents, and the information to uniquely identify their antecedents comes only from sources external to the anaphors.

Intuitively, more explicit anaphors seem more accessible than less explicit anaphors; empirically, sentences containing more explicit anaphors are read more rapidly than comparable sentences containing less explicit anaphors (Haviland & Clark, 1974; Yekovich & Walker, 1978). Furthermore, the antecedents of more explicit anaphors are more activated than the antecedents of less explicit anaphors (Corbett & Chang, 1983; McKoon & Ratcliff, 1980).

For instance, compare sentence (2) below with sentence (1) above.

-

(2)

Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race, but Pam came in first very easily.

In sentence (2), the second-clause anaphor is the repeated proper name, Pam. This is an example of a very explicit anaphor; it matches its antecedent exactly. In contrast, the anaphor in sentence (1), the pronoun, she, is considerably less explicit. It could refer to either participant, and only the semantic information in the second clause identifies its unique antecedent.4 When Corbett and Chang (1983) measured activation after comprehenders read these two types of sentences, the antecedents were more activated than the nonantecedents (as mentioned above). Perhaps more intriguing, this difference was considerably larger when the anaphors were explicit proper names rather than less explicit pronouns.

This finding suggests that the information content of an anaphor affects its antecedent’s accessibility. And it does so by separating its antecedent’s activation level from other concepts’ activation levels. One way this would happen is if the information available in an anaphor triggers the mechanisms of suppression and enhancement. If so, then the more explicit the anaphor (i.e., the more information it provides about its antecedent), the more likely it should be to trigger the suppression of nonantecedents and the enhancement of its own antecedent. In other words, the effects of suppression and enhancement should be a function of anaphoric explicitness. The experiments reported here examined this proposal.

How does an anaphor trigger the mechanisms of suppression and enhancement? If we consider an anaphor as analogous to a retrieval cue, we can draw upon models of recognition memory to illuminate this process. According to many models, a retrieval cue makes previously represented traces accessible in the same way that a tuning fork evokes vibrations from tuning forks of similar frequencies. Indeed, Ratcliff (1978) describes retrieval as “resonance” (and uses the tuning fork analogy), and Hintzman (1987, 1988) describes it as a “probe” evoking an “echo.”

Furthermore, in such models, the more similar a retrieval cue is to a previously experienced trace, the greater the resonance or the more intense the echo. In other words, accessibility (through retrieval) is a function of the similarity between a retrieval cue and a memory trace. Simulations and experiments confirm this assumption (these proposals are culled from the models of Bower, 1967; Hintzman, 1987, 1988; McClelland & Rumelhart, 1986; Raaijmakers & Shiffrin, 1981; Ratcliff, 1978).

In a similar way, an anaphor might evoke (or trigger) the mechanisms of suppression and enhancement in order to improve its antecedent’s accessibility. If so, the greater the similarity between an anaphor and its antecedent—in other words, the more explicit the anaphor is—the more powerfully the anaphor should trigger suppression and enhancement.

Information about an antecedent’s identity also comes from sources beyond the anaphor, just as factors beyond the nature of the retrieval cue affect retrieval, and para-lexical (e.g., semantic and syntactic) information affects the recognition of nonanaphoric words. Presumably, information from these other sources also triggers suppression and enhancement, but most likely it does so more slowly (or perhaps less powerfully). The experiments reported here examined this proposal.

In essence, the model sketched above suggests that comprehenders access the appropriate antecedents for anaphors somewhat similarly to how they access the appropriate meanings of nonanaphoric words. In both cases, comprehenders access the most activated mental representations. The novel proposal is that two mechanisms play a role in this process by modifying activation. Suppression decreases the activation of other, nonantecedent concepts, while enhancement increases the antecedents’ activation. The model also suggests that the mechanisms of suppression and enhancement are triggered by information that specifies the antecedents’ identity. Foremost is the information provided by the anaphors. Therefore, more explicit anaphors should trigger more suppression and enhancement, just like more explicit retrieval cues evoke more resonance. Information from other sources (e.g., semantic and pragmatic information) should also trigger suppression and enhancement, but more slowly. Thus, the role of the two mechanisms is to improve a referent’s accessibility. Comprehenders can then access that referent and incorporate it into their developing discourse structures.

Experiment 1

The first experiment investigated whether more versus less explicit anaphors immediately trigger suppression or enhancement. To investigate this, the activation levels of antecedents versus nonantecedents were measured immediately before versus immediately after comprehenders read explicit versus less explicit anaphors.

Subjects read two clause sentences such as (1) or (2) above. In the first clause of each sentence, two participants were introduced, just as Ann and Pam are introduced in the first clauses of sentences (1) and (2). In the second clause of each sentence, one of those two participants was anaphorically referenced by either a less explicit, pronoun anaphor, such as she in sentence (1) or a more explicit, repeated name anaphor, such as Pam in sentence (2).

Immediately before and immediately after subjects read these anaphors, the activation level of the anaphors’ antecedents (e.g., Pam) and nonantecedents (e.g., Ann) was measured. This was accomplished through a probe verification task: Subjects were presented with a probe word, and they rapidly verified whether the probe word had occurred in the sentence they were reading. Faster verification latencies reflect higher levels of activation (Ratcliff, Hockley, & McKoon, 1985). For the experimental sentences, the probe words were the names of the antecedents (e.g., Pam) or nonantecedents (e.g., Ann).

Three variables were manipulated: anaphor type (whether the anaphors were names or pronouns), probe name (whether the probe names were the antecedents or nonantecedents), and test point (whether the probe names were tested immediately before or immediately after the anaphors). A fourth variable was also manipulated; it was antecedent position (whether the antecedents were the first-mentioned participants, NP1s, or the second-mentioned participants, NP2s, in the first clause). An example of an NP1, and an NP2 experimental sentence appears in Table 1.

Table 1.

Example stimulus sentences for Experiments 1, 2, and 3

| NP1 type sentence |

| PRONOUN - ANTECEDENT (BILL) |

| Bill handed John some tickets to a concert2 but1 he1, 2, 3 took the tickets back immediately.3 |

| NAME - ANTECEDENT (BILL) |

| Bill handed John some tickets to a concert2 but1 Bill1, 2, 3 took the tickets back immediately.3 |

| PRONOUN - NONANTECEDENT (JOHN) |

| Bill handed John some tickets to a concert2 but1 he1, 2, 3 took the tickets back immediately.3 |

| NAME - NONANTECEDENT (JOHN) |

| Bill handed John some tickets to a concert2 but1 Bill1, 2, 3 took the tickets back immediately.3 |

| NP2 type sentence |

| PRONOUN - ANTECEDENT (PAM) |

| Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race2 but1 she1, 2, 3 came in first very easily.3 |

| NAME - ANTECEDENT (PAM) |

| Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race2 but1 Pam1, 2, 3 came in first very easily.3 |

| PRONOUN-NONANTECEDENT(ANN) |

| Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race2 but1 she1, 2, 3 came in first very easily.3 |

| NAME-NONANTECEDENT(ANN) |

| Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race2 but1 Pam1, 2, 3 came in first very easily.3 |

Note: For each sentence, the probe name appears in parentheses, the antecedent appears in boldface, the anaphor is in italics, and the two test points are superscripted with the experiment’s number.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 128 undergraduates at the University of Oregon. As in all the following experiments, the subjects participated as a means of fulfilling an introductory psychology course requirement; they were all native American English speakers, and no subject participated in more than one experiment.

Materials and design

Sixty-four experimental sentences were constructed. All contained two clauses, mentioned two participants in the first clause (NP1, and NP2), and rementioned one of those two participants in the second clause. Many were modifications of Corbett and Chang’s (1983) experimental sentences but with two additional properties controlled. The first property was the distance between the first mention of the NP2s in the first clause and the anaphors in the second clause (for example, the distance between John and either the pronoun he or the rementioned name Bill in the first sentence shown in Table 1). Six words always intervened between those two points. The second property was the distance between the anaphors and the ends of the sentences. Five words always intervened between those two points.

To ensure that the information in the second clauses identified a unique antecedent, the following normative data were collected. Fifty subjects at the University of Texas, who were otherwise uninvolved with any of the experiments reported here, read the experimental sentences in their pronoun-anaphor forms (e.g., “Bill handed John some tickets to a concert, but he took the tickets back immediately”). The subjects indicated which of the two participants the pronouns referred to. Only sentences that elicited more than 90% agreement with the experimenter were used in the experiment. These sentences are listed in Appendix A.

In each sentence, the two participants’ names were typical, American first names that were matched for perceived familiarity and length in letters. They were names commonly ascribed to only one gender (for instance, names such as “Pat” were avoided). Across all the sentences, half the names were stereotypically female, and half were stereotypically male. But within each sentence, the two names were stereotypic of the same gender.

To encourage comprehension, each experimental sentence was followed by a two-alternative WH question, with the two answers being the two participants’ names. Half the questions were about the first clause, and half were about the second clause. When the anaphors were pronouns, the questions were about the second clause. This served the purpose of discovering whether subjects understood who the pronouns referred to. Examples of this type of question for the NP1 and NP2 sentences in Table 1 are “Who took the tickets back immediately?” and “Who came in first very easily?”, respectively. When the anaphors were names, the questions were about the first clauses. And, as a finer division, half the questions were about the first-mentioned participants’ activity in the first clause (e.g., “Who handed someone some tickets?” or “Who predicted that someone would lose a race?”), and half were about the second-mentioned participants’ activity in the first clause (e.g., “Who was handed some tickets?” or “Who was predicted to lose the race?”).

Forty-eight lure sentences were constructed. A lure sentence was one in which the probe name did not occur. The lure sentences had one of the following three syntactic forms: (i) 16 were identical to the NP1 experimental sentences with half the anaphors being pronouns and half being the names of NP1 (ii) 16 were identical to the NP2 experimental sentences with half the anaphors being pronouns and half being the names of NP2, and (iii) 16 had first clauses identical to the experimental sentences, but the anaphors were the plural pronoun they, for example, “Bobby saw David walking over to the library, and they decided to walk there together.” In these lure sentences, the probe names were tested at one of four different locations. In 12 lure sentences (four each of the three syntactic forms), the probe names were tested relatively early in the sentence; in another 12 sentences, the probe names were tested relatively late in the sentence; in another 12, the probe names were tested immediately prior to the anaphors (just like the experimental sentences) and in the final 12, the probe names were tested immediately after the anaphors (again, just like the experimental sentences).

Eight material sets were formed. Within a material set, there was an equal number of experimental sentences in the eight experimental conditions. Across material sets, each experimental sentence occurred in all eight of its experimental conditions. Twelve subjects were randomly assigned to each material set; thus, each subject was exposed to an experimental sentence in only one of its conditions. The lure sentences occurred in the same randomly selected order in each material set.

Procedure

The stimulus sentences appeared word-by-word in the center of a video display monitor. How long each word remained on the screen was a function of its length plus a constant. The function was 16.667 ms per character, and the constant was 300 ms. For example, a five-letter word was shown for 383.3 ms. These timing parameters were based on the reading times produced by 12 subjects, who were otherwise uninvolved with the experiment, and who read self-paced, word-by-word through the experimental materials. Even the slowest of these 12 subjects read comfortably faster than the rate produced by the above function.

Each trial began with a warning signal, which was a plus sign that appeared for 750 ms in the center of the screen. After that, each word of the sentence appeared with an interword interval of 150 ms. When the probe names were tested, they appeared in capital letters at the top of the screen. When the probe names were tested before the anaphors, they appeared 150 ms after the offset of the word immediately prior to the anaphors. When they were tested immediately after the anaphors, they appeared 150 ms after the offset of the anaphors. The probe names remained on the screen until either the subjects responded or 2.5 seconds elapsed. Subjects responded with their dominant hand, pressing one key with their index finger and another with their middle finger.

After each experimental sentence, the word Test appeared for 750 ms toward the bottom of the screen to warn subjects that a comprehension question would appear next. Appearing along with the comprehension question were its two answer choices (i.e., the two participants’ names). One answer choice appeared in the bottom left corner, and the other in the bottom right corner. The answer choice in each corner was correct half the time. The questions and answer choices remained on the screen until either the subjects responded by pressing one of two response keys, or 10 s elapsed. After responding, the subjects were given feedback about their accuracy.

Subjects were replaced if they failed to meet the following criteria: 90% accuracy at responding to experimental probe names (requiring a “yes” response), 90% accuracy at responding to lure probe names (requiring a “no” response), and 85% accuracy at answering the two-choice comprehension questions.

Results

The following is true of all the analyses reported for this and the subsequent experiments: The correct response times were analyzed in two sets of analyses of variance (ANOVAs). In the first set, subjects was treated as a random effect; in the second, items was treated as a random effect. The results reported here are based on the minF’ statistic (Clark, 1973) and a significance level of p < .05 or lower.

For Experiment 1, the design of both sets of ANOVAs was 2 (Anaphor Type: name vs. pronoun) × 2 (Probe Name: antecedent vs. nonantecedent) × 2 (Test Point: before vs. after the anaphors) × 2 (Antecedent Position: NP1 vs. NP2). In the subjects’ analysis, all four factors were within-subjects. In the items’ analysis, antecedent position (NP1 vs. NP2) was a between-items factor.

One main effect was significant: Responses were faster when the probe names were the antecedents (M = 861) than the nonantecedents (M = .905), minF’(1,120) = 24.69; in other words, the antecedents were more activated than the nonantecedents. This effect replicates Corbett and Chang (1983).

Four interactions were significant. One was between antecedent position (NP1 vs. NP2) and probe name (antecedents vs. nonantecedents), minF’(1,151) = 37.59. This interaction is actually an effect of order of mention: Responses were significantly faster when the probe names were the first-mentioned participants (i.e., the antecedent position was NP1 and the probe names were the antecedents, or the antecedent position was NP2 and the probe names were the nonantecedents) than when the probe names were the second-mentioned participants (i.e., the antecedent position was NP2 and the probe names were the antecedents, or the antecedent position was NP1 and the probe names were the nonantecedents). In other words, first-mentioned participants were verified more rapidly (M = 853) than second-mentioned participants (M = 913).

This advantage for first-mentioned participants has been observed before (Corbett & Chang, 1983; Stevenson, 1986; Von Eckardt & Potter, 1985). Among its more trivial explanations is the notion that the first-mentioned participants’ names (although assigned randomly) were more salient. However, even in Experiment 4 when antecedent position was manipulated within-items, the same advantage held. The source of this advantage will be discussed in the General Discussion.

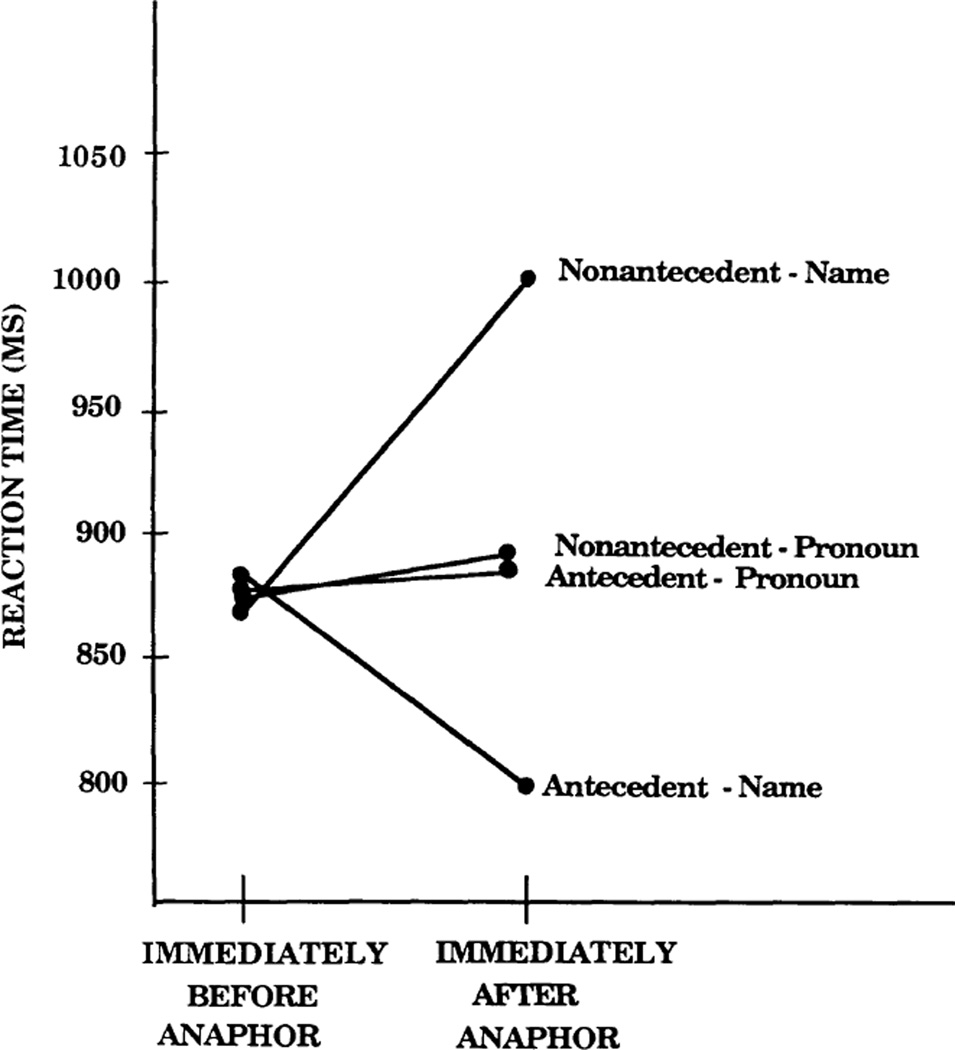

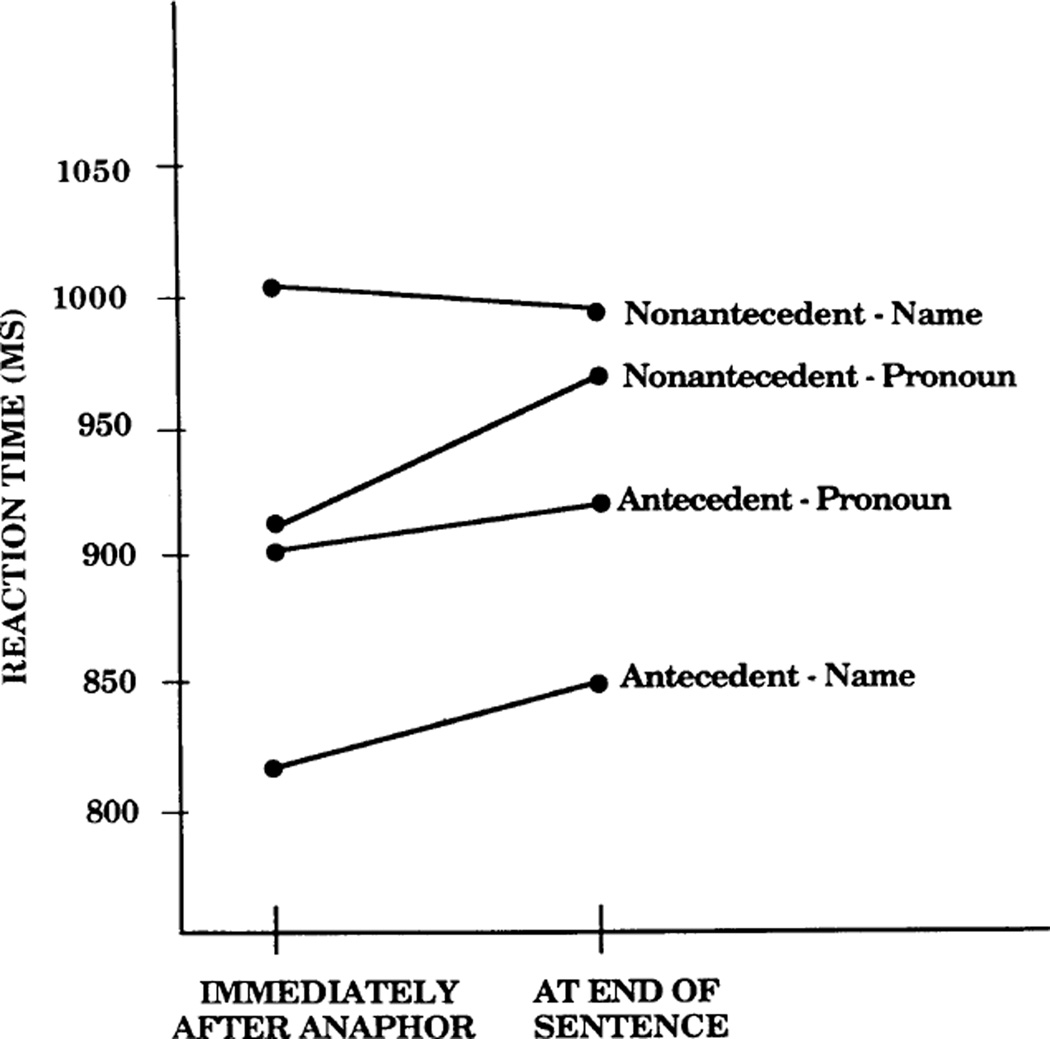

Of the three other significant interactions, one was between anaphor type and probe name, minF’(1,160) = 43.51, and one was between probe name and test point, minF(1,121) = 37.26. However, both of these interactions were qualified by the remaining significant interaction, a three-way interaction involving anaphor type (name vs. pronoun), probe name (antecedent vs. nonantecedent), and test point (before vs. after the anaphors), minF’(1,162) = 53.74. This three-way interaction is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Subjects’ mean response times in Experiment 1.

Consider first what happened when the anaphors were explicit, repeated names. As illustrated in Figure 1, when the anaphors were names, probe name interacted with test point, minF’(1,151) = 103.26, in the following way: Responses to the nonantecedents were 122 ms slower after the name anaphors (M = 990) than before (M = 868), minF’(1,155) = 66.90. On the other hand, responses to the antecedents were 76 ms faster after the name anaphors (M = 803) than before (M = 879), minF’(1,117) = 22.60.

This is the pattern one expects if name anaphors trigger both the suppression of nonantecedent participants—which is why the nonantecedents were less activated immediately after the anaphors than before—as well as the enhancement of their own antecedents—which is why the antecedents were more activated immediately after the anaphors than before. Thus, explicit, repeated name anaphors appear to improve their antecedents’ accessibility by triggering both of the proposed mechanisms.

However, as also illustrated in Figure 1, this is what happens with explicit name anaphors, but not necessarily less explicit pronouns. Indeed, when the anaphors were pronouns, the probe name by test point interaction was far from reliable, F1(1,127) = 0.04, F2(1,62) = 0.03 (which was the basis of the three-way interaction between anaphor type, probe name, and test point). In fact, response times after the pronouns (M = 885) were statistically indistinguishable from response times before the pronouns (M = 877), both Fs < 1, and this was true for both the antecedents and the nonantecedents, both minFs < 1. In other words, there was no immediate change in activation as a result of subjects reading the pronouns.

Discussion

Experiment 1 demonstrated that explicit name anaphors immediately improve their antecedents’ accessibility by both suppression and enhancement. The evidence that name anaphors immediately trigger the suppression of other nonantecedent participants came from the finding that the nonantecedents were considerably less activated after the names than before; the evidence that name anaphors immediately trigger the enhancement of their antecedents came from the finding that the antecedents were considerably more activated after their anaphors than before. The two mechanisms’ net effect was that the antecedents and nonantecedents differed markedly in their levels of activation; thus, together the two mechanisms greatly improved their antecedents’ accessibility.5

In contrast to explicit name anaphors, less explicit pronouns do not appear to immediately trigger either suppression or enhancement. This contrast suggests that the anaphors’ informational content (their explicitness) affects how rapidly (and possibly how powerfully) they affect their antecedents’ accessibility. More explicit anaphors, such as repeated names, appear to immediately trigger suppression and enhancement; less explicit anaphors, such as pronouns that match the gender, number, and case of multiple participants, do not immediately affect the activation of either their antecedents or nonantecedents.

Indeed, in Experiment 1, the pronouns’ antecedents and nonantecedents were just as activated before the pronouns as immediately after. This suggests that both the antecedents and nonantecedents were already activated before the pronouns, and they simply remained at that level of activation immediately afterward. Although this finding conflicts with many psycholinguists’ assumption that pronouns immediately “reactivate” their antecedents, it confirms many functional linguists’ assumption that speakers and writers use pronouns to refer to concepts that are already activated in their listeners’ and readers’ mental representations.

For instance, according to Karmiloff-Smith (1980), “anaphoric pro-nominalization functions as an implicit instruction for the addressee not to recompute for retrieval of an antecedent referent, but rather to treat the pronoun as the default case for the thematic subject of a span of discourse.” Similarly, in Chafe’s (1974) view, pronouns are used to refer to “given information” about which he writes: “If the exploration in terms of consciousness is correct, it is misleading to speak as if the addressee needs to perform some operation of recovery for given information. The point is rather that such information is already on stage in the mind.” In recent work, Chafe (1987) has translated his conception of “on stage in the mind” into cognitive psychologists’ nomenclature of “already active.”

Other behavioral data corroborate Experiment 1 and thereby support functional linguists’ assumption. For instance, in a study by Tyler and Marslen-Wilson (1982), subjects heard sentences such as

-

(3)

The sailor tried to save the cat, but he/it fell overboard instead.

Each sentence introduced a human and a nonhuman participant (e.g., sailor and cat), and in the second clause of each sentence, one of the participants was referred to with a human versus nonhuman pronoun (e.g., he or it). While listening to each sentence, comprehenders made lexical decisions to probe words, which on the experimental trials were related to one of the two participants. For instance, the probe word for sentence (3) might have been boat or dog.

The probe words were responded to more rapidly when they were related to one of the two participants than when they were presented during control (unrelated) sentences. But it did not matter whether the probe words were tested before versus after the pronouns; neither did it matter whether the probe words were related to the pronouns’ antecedents or the nonantecedents. The same level of semantic facilitation was observed in each case. In other words, like Experiment 1, there was evidence that both the antecedents and nonantecedents were already activated prior to the pronouns, and like Experiment 1, this level of activation did not change immediately because of the pronouns.

Indeed, Tyler and Marslen-Wilson (1982) concluded that “the analysis that fits the results best [is] that both [participants] are activated early in the second clause, and remain activated for at least the next few words” (p. 281).

So, the Tyler and Marslen-Wilson (1982) data, as well as Experiment 1, demonstrate that less explicit, pronoun anaphors do not immediately trigger suppression or enhancement to improve their antecedents’ accessibility. But surely, at some point, the pronouns’ antecedents and nonantecedents must differ in their activation level. How else would comprehenders access the pronouns’ unique referents? Experiments 3, 4, and 5 in this series explored how and when this occurs.

Before turning toward those experiments, an alternative explanation for one aspect of Experiment l’s results needs elimination. Perhaps the before-the-anaphor test point demonstrated that the antecedents and nonantecedents were already activated because that test point occurred at the beginning of a clause. Perhaps, at the beginning of a clause, recently mentioned concepts are automatically reactivated. Such a hypothesis falls out of certain processing models that treat clauses as their processing units. In such models, it seems advantageous if—at the beginning of a new processing cycle (e.g., a clause)—concepts from the prior cycle were made more accessible. Experiment 2 attempted to rule out this explanation and while doing so provided an opportunity to replicate Experiment 1.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 was identical to Experiment 1 except that the before-the-anaphor test point was moved up one word. Recall that in Experiment 1, the before-the-anaphor test point was immediately after the conjunctions and, therefore, after the first words of the second clauses. In Experiment 2, the before-the-anaphor test point was immediately after the last words of the first clauses, that is, immediately prior to the conjunctions. This revised test point is indicated in Table 1 with the superscript 2. As indicated in Table 1, the after-the-anaphor test point was identical to Experiment 1.

Method

The only methodological difference between Experiment 2 and Experiment 1 was that when the probe names were tested before the anaphors, they appeared 150 ms after the offset of the first clauses’ final words. Ninety-six subjects participated.

Results

The design of the ANOVAs was the same as in Experiment 1, and the results were identical. Responses were faster when the probe names were the antecedents (M = 922) than the nonantecedents (M = 974), minF’(1,108) = 20.13. This replicates both Experiment 1 and Corbett & Chang (1983). In addition, antecedent position (NP1 vs. NP2) interacted with probe name, minF’(1,106) = 23.39, again, demonstrating that, in general, first-mentioned participants were verified more rapidly (M = 920) than second-mentioned participants (M = 976).

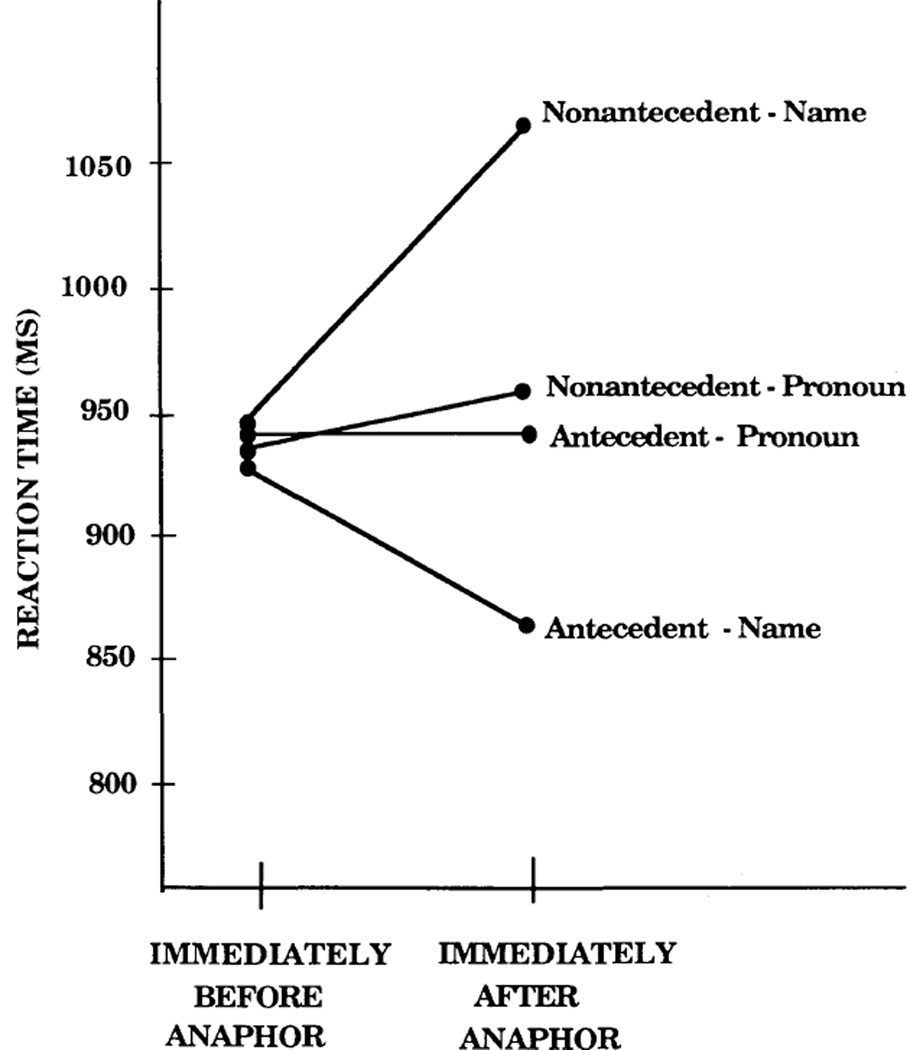

Furthermore, as in Experiment 1, three other interactions were significant. One interaction was between anaphor type and probe name, minF’(1,139) = 35.68, and another was between probe name and test point, minF’(1,116) = 10.23. However, both interactions were again qualified by a three-way interaction involving anaphor type, probe name, and test point, minF’(1,87) = 8.26, and this three-way interaction is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Subjects’ mean response times in Experiment 2.

As illustrated in Figure 2, when the anaphors were names, probe name (antecedent vs. nonantecedent) strongly interacted with test point (before vs. after the anaphors), minF’(1,116) = 34.64. And the pattern of this interaction was identical to Experiment 1: Responses to the nonantecedents were 127 ms slower after the name anaphors (M = 1069) than before (M = 942), minF’(1,111) = 34.81. On the other hand, responses to the antecedents were 85 ms faster after the name anaphors (M = 864) than before (M = 949), minF’(1,124) = 14.19.

As in Experiment 1, this pattern suggests that name anaphors immediately trigger both the suppression of nonantecedents—which is why the nonantecedents were less activated after the anaphors than before—and the enhancement of their antecedents—which is why the antecedents were more activated after the anaphors than before. So, like Experiment 1, Experiment 2 provided evidence that explicit, repeated name anaphors improve their antecedents’ accessibility by immediately triggering both of the proposed mechanisms.

However, also like Experiment 1, this evidence was observed only for the name anaphors. Indeed, when the anaphors were less explicit pronouns, the probe name by test point interaction was far from reliable, minF’ < 1.0. That is, response times after the pronouns (M = 942) were statistically indistinguishable from response times before the pronouns (M = 937), both Fs < 1. And again, this was true for both the antecedents and the nonantecedents, both minFs < 1. Thus, there was no immediate change in activation as a result of subjects reading the pronouns.

Discussion

Experiment 2 perfectly replicated Experiment 1 in demonstrating that explicit name anaphors immediately improve their antecedents’ accessibility by both suppression and enhancement. Experiment 2 also perfectly replicated Experiment 1 in demonstrating that, in contrast to explicit name anaphors, less explicit pronouns do not trigger suppression or enhancement immediately. As in Experiment 1, the pronouns’ antecedents were activated at the same level as their nonantecedents both before and after the pronouns. This pattern again suggests that the two sentence participants were already activated prior to the anaphors, and the pronouns did not alter those activation levels. Furthermore, Experiment 2 demonstrated that when this pattern was observed in Experiment 1, it was not due to the participants being reactivated at the beginnings of their second clauses.

But, as mentioned before, surely at some point following the pronouns, their antecedents and nonantecedents should be activated at different levels. How else would comprehenders access the pronouns’ unique referents? Indeed, when Corbett and Chang (1983) measured activation at the ends of the sentences, they found that the pronouns’ antecedents and nonantecedents differed in activation.

Perhaps the semantic information presented in the second clauses combines with information provided by the pronouns.6 This combined information might also trigger suppression or enhancement, but it might do so less quickly or less powerfully than if the information was explicitly provided by the anaphor. Experiment 3 investigated this proposal by measuring activation immediately after the anaphors (as in Experiments 1 and 2) and at the ends of the sentences (as in Corbett & Chang’s study, 1983).

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 was identical to Experiments 1 and 2 except that activation was measured immediately after the anaphors and at the ends of the sentences. These two points are indicated in Table 1 with the superscript 3. Measuring activation immediately after the anaphors provided the opportunity to replicate the after-the-anaphor test point data from Experiments 1 and 2; measuring activation at the ends of the sentences provided the opportunity to replicate Corbett and Chang (1983). Comparing the two test points provided the opportunity to document what happens over the second clauses of the sentences to make the pronouns’ antecedents more accessible.

Method

Experiment 3 used the same materials as Experiments 1 and 2. The procedure was also identical, with the following major exception: The probe names were presented either 150 ms after the offset of the anaphors or 150 ms after the offset of the final words of the sentences. Recall that six words always intervened between the introduction of the second sentence participants (NP2) and the anaphors, and five words always intervened between the anaphors and the ends of the sentences. Ninety-six subjects participated.

Results

The design of the ANOVAs was the same as in Experiments 1 and 2. Two main effects were significant. First, responses were faster to the antecedents (M = 849) than the nonantecedents (M = 947), minF’(1,95) = 40.54. Second, responses were faster immediately after the anaphors (M = 891) than at the ends of the sentences (M = 914), minF’(1,116) = 5.55.

Three interactions were significant. First, as in Experiments 1 and 2, antecedent position interacted with probe name, minF’(1,99) = 23.88, again demonstrating that, in general, first-mentioned participants were verified more rapidly (M = 870) than second-mentioned participants (M = 936).

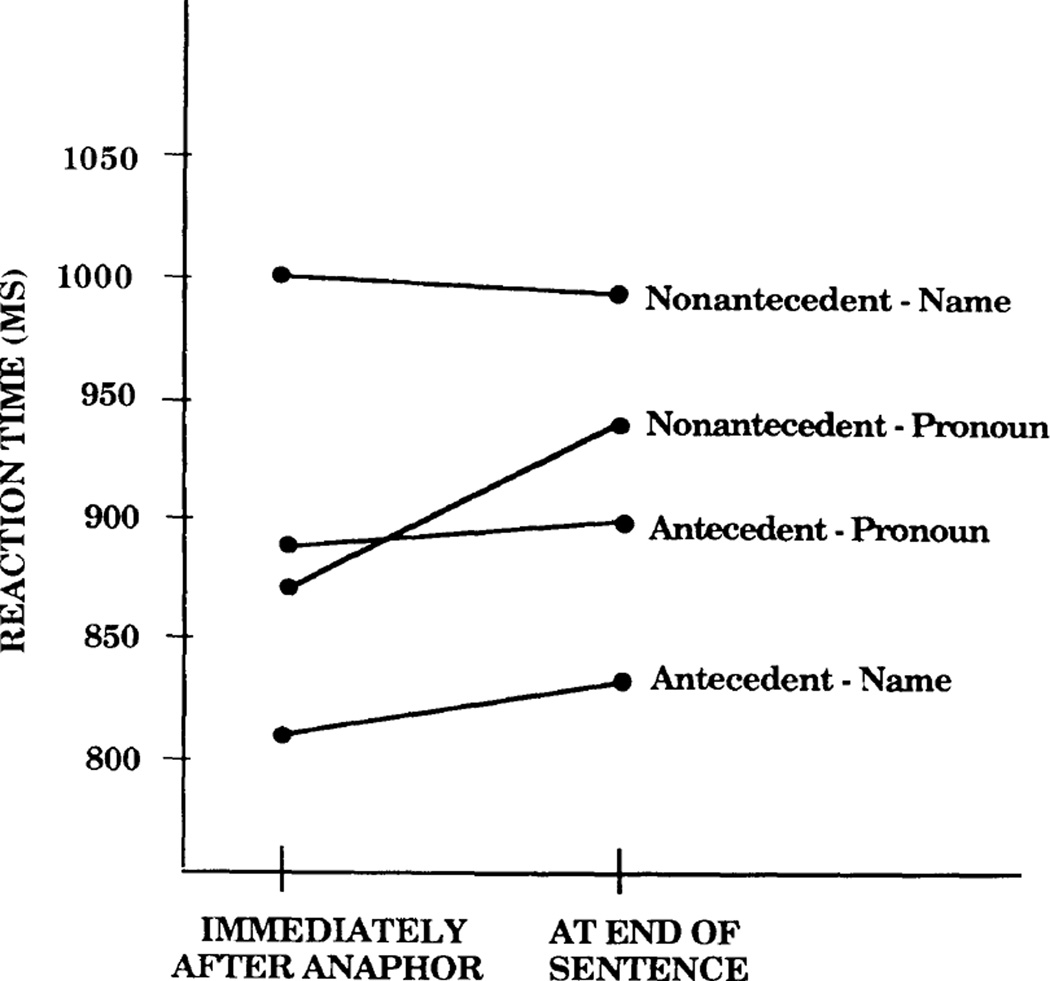

Second, probe name interacted with anaphor type, minF’(1,143) = 86.21. But this two-way interaction was qualified by the only other significant interaction: a three-way interaction involving probe name, anaphor type, and test point, minF’(1,120) = 7.47. This three-way interaction is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Subjects’ mean response times in Experiment 3.

As illustrated in Figure 3, when the probe names were the nonantecedents, anaphor type (name vs. pronoun) interacted with test point, minF’(1,119) = 10.28, creating the following effect: The difference between response times when the anaphors were names versus pronouns was much larger immediately after the anaphors (134 ms) than at the ends of the sentences (55 ms), although both differences were reliable, minF’(1,121) = 49.87, and minF’(1,119) = 11.03, respectively. On the other hand, when the probe names were the antecedents, anaphor type did not interact with test point, minF’ < 1; the difference between response times when the anaphors were names versus pronouns was about the same immediately after the anaphors as at the ends of the sentences.

Another way to think about this three-way interaction is that the effect of test point was greatest on one particular combination of anaphor type and probe name. That combination was when the anaphors were pronouns, and the probe names were nonantecedents. For that combination, and that combination alone, the difference between the two test points was reliable (all other minFs, < 1). This difference arose because responses to the pronouns’ nonantecedents were significantly slower at the ends of the sentences (M = 933) than they were immediately after the anaphors (M = 866), minF’(1,106) = 12.49.

In other words, only the activation level of the pronouns’ nonantecedents changed as subjects read the second clauses. As illustrated in Figure 3, the change was that the pronouns’ nonantecedents became less activated. One interpretation of this change is that the information provided by the pronouns, combined with the semantic information available in the second clauses, triggered the suppression of the nonantecedents. Thus, like repeated name anaphors, semantically-biased pronouns also appear to trigger suppression, but they do so more slowly and less powerfully.

Further analyses compared Experiment 3 with Experiment 1, Experiment 2, and Corbett and Chang (1983). First, consider the data collected immediately after the pronouns in Experiment 3. Those data perfectly replicated Experiments 1 and 2. All three experiments found that response times to the pronouns’ antecedents versus nonantecedents were statistically indistinguishable (minF’ < 1 for Experiment 3). So, again, there was no evidence that pronouns immediately affect the activation of either their antecedents or nonantecedents.

Next, consider the data collected immediately after the names in Experiment 3. Those data also perfectly replicated Experiments 1 and 2. All three experiments demonstrated that immediately after the more explicit name anaphors, the antecedents and nonantecedents were activated at considerably different levels. In Experiment 3 this difference was 191 ms; in Experiment 1 it was 187 ms; and in Experiment 2 it was 202 ms. Experiments 1 and 2 suggested that this difference arose because name anaphors immediately trigger both the suppression of their nonantecedents and the enhancement of their antecedents.

Finally, consider the data collected at the ends of the sentences in Experiment 3. Those data perfectly replicated Corbett & Chang (1983). In both studies, anaphor type interacted with probe name. That is, the difference between the antecedents versus nonantecedents was greater when the anaphors were explicit names than it was when they were less explicit pronouns. Again, this suggests that the more explicit the anaphor—that is, the more information it provides about its antecedent—the more likely it is to trigger suppression and enhancement.

Discussion

Experiment 3 further illustrated the role that the mechanism of suppression plays in improving referential access. Experiment 3 demonstrated that semantically-biased pronouns also trigger the suppression of nonantecedents. This demonstration came from the following effect: Immediately after the pronouns, the antecedents and nonantecedents did not differ in activation (replicating Experiments 1 and 2), but by the ends of the sentences, they did (replicating Corbett & Chang, 1983). As illustrated in Figure 3, this difference arose because the nonantecedents lost activation. So, it appears that pronouns also improve their antecedents’ referential access by triggering the suppression of other concepts, but they do so more slowly (and perhaps less powerfully).

Why do pronouns trigger suppression more slowly than name anaphors? One explanation is that pronouns are less explicit than repeated name anaphors. That is, even though—as in the sentences presented in these experiments—semantic information often helps disambiguate pronouns, pronouns per se are less explicit than other forms of anaphora. So, the suppression mechanism is triggered more slowly, perhaps because information has to be gathered from other sources.

Unfortunately, this assumption is hard to test directly with the sentences used in Experiment 3 because it was not until the second clauses that the semantic information occurred: That factor alone could explain why the effects of suppression were not observed until the test point at the end of the sentences. A stronger test of this proposal could be made if the semantic information occurred prior to the pronouns, and the second clauses were neutral. If suppression is still triggered more slowly, this would suggest that information available in the anaphors is what primarily triggers the mechanism of suppression during referential access. Experiment 4 explored this proposal.

Experiment 4

In Experiment 4, the two-clause sentences of Experiments 1, 2, and 3 were expanded into sentence pairs. The first sentence of each pair introduced the two participants and created a context, as in

-

(4)

Bill lost a tennis match to John.

These first sentences remained constant across all the conditions. The second sentence of each pair began with a participial phrase. These preposed phrases were what provided the semantic information to further identify the anaphors, as in

-

(5)

Accepting the defeat, he walked quickly toward the showers.

-

(6)

Enjoying the victory, he walked quickly toward the showers.

The second sentence of each pair had two versions. In one version, the participial phrases referred to the first-mentioned participants (NP1), as in (5) above; in the other version, the phrases referred to the second-mentioned participants (NP2), as in (6) above. In this way, the antecedent position variable was manipulated within-items. However, both versions of the second sentences had identical main clauses, and these were intended to be neutral vis-à-vis the anaphors’ identities. In this way, the semantic information was restricted to the preposed participial phrases (i.e., the information occurring before the anaphors).

As in Experiment 3, the variables anaphor type (whether the anaphors were names or pronouns), probe name (whether the probe names were the antecedents or nonantecedents), and test point (whether the probe names were tested immediately after the anaphors or at the ends of the sentences) were also manipulated. An example experimental sentence appears in Table 2.

Table 2.

Example stimulus sentences for Experiment 4

| NP1 version | |||

| PRONOUN - ANTECEDENT (BILL) | |||

| Bill lost a tennis match to John. | |||

| Accepting the defeat, he4 walked slowly toward the showers.4 | |||

| NAME - ANTECEDENT (BILL) | |||

| Bill lost a tennis match to John. | |||

| Accepting the defeat, Bill4 walked slowly toward the showers.4 | |||

| PRONOUN - NONANTECEDENT (JOHN) | |||

| Bill lost a tennis match to John. | |||

| Accepting the defeat, he4 walked slowly toward the showers.4 | |||

| NAME - NONANTECEDENT (JOHN) | |||

| Bill lost a tennis match to John. | |||

| Accepting the defeat, Bill4 walked slowly toward the showers.4 | |||

| NP2 version | |||

| ANTECEDENT - PRONOUN (JOHN) | |||

| Bill lost a tennis match to John. | |||

| Enjoying the victory, he4 walked slowly toward the showers.4 | |||

| ANTECEDENT - NAME (JOHN) | |||

| Bill lost a tennis match to John. | |||

| Enjoying the victory, John4 walked slowly toward the showers.4 | |||

| NONANTECEDENT - PRONOUN (BILL) | |||

| Bill lost a tennis match to John. | |||

| Enjoying the victory, he4 walked slowly toward the showers.4 | |||

| NONANTECEDENT - NAME (BILL) | |||

| Bill lost a tennis match to John. | |||

| Enjoying the victory, John4 walked slowly toward the showers.4 | |||

Note: For each sentence, the probe name appears in parentheses, the antecedent appears in boldface, the anaphor is in italics, and the two test points are superscripted with the experiment’s number.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 192 undergraduates at the University of Oregon.

Materials and design

Sixty-four experimental sentence pairs were constructed. As mentioned above, a sentence pair comprised a context-setting sentence that introduced the two participants, followed by a sentence that referred to only one of the two participants. The second sentences began with one of two participial phrases. The two participial phrases were as similar in form as possible, and, although they were not identical in length, they typically varied by only a couple of characters. The distance between the anaphors and the ends of the sentences was always five words.

To make sure that the preposed participial phrases did indeed refer to only one of the participants, the following normative data were collected. Fifty subjects at the University of Texas, who were otherwise uninvolved with any of the experiments reported here, read the experimental sentence pairs with the second sentence of each pair in its pronoun-anaphor form. For example, the subjects read, “Bill lost a tennis match to John. Accepting the defeat, he walked quickly toward the showers.” Or they read, “Bill lost a tennis match to John. Enjoying the victory, he walked quickly toward the showers.” The subjects indicated which of the two participants the pronouns referred to. Only sentence pairs that elicited more than 90% agreement with the experimenter were used in Experiment 4.

In addition, to make sure that the information following the anaphors was neutral, more normative data were collected. Another group of 50 subjects at the University of Texas, who were otherwise uninvolved with the experiments, also read the sentences in their pronoun forms. But for these subjects, the second clauses of the second sentences were replaced with ellipses. For example, these subjects read, “Bill lost a tennis match to John. Accepting the defeat, he … .” Or they read, “Bill lost a tennis match to John. Enjoying the victory, he … .” Again, subjects indicated which of the two participants the pronouns referred to. Only sentence pairs that elicited over 95% agreement between this second group of subjects and the first group (who had received the sentence pairs with their final clauses intact) were used in Experiment 4. The 64 experimental sentence pairs appear in Appendix B.

As in Experiments 1, 2, and 3, the names of the two participants in each sentence pair were matched for perceived familiarity and length in letters and were stereotypic of only one gender. Across all sentence pairs, half the names were stereotypically female, and half were stereotypically male.

Also as in Experiments 1, 2, and 3, to encourage comprehension, each experimental sentence was followed by a two-alternative WH question. The two answers were the two participants. Half the questions were about the first sentences (the context-setting sentences), and half were about the second sentences. When the anaphors were pronouns, the questions were about the second sentences. And, as a finer division, half were about the participial phrases; for example, for the sentence in Table 2, these questions were “Who enjoyed the victory?” and “Who accepted the defeat?” The other half were about the main clauses (e.g., “Who walked quickly toward the showers?”). These questions tested whether subjects had identified who the pronouns referred to. When the anaphors were names, the questions were about the first sentences. And, as a finer division, half were about the first-mentioned participants’ activity (e.g., “Who lost a tennis match?”), and the other half were about the second-mentioned participants’ activity (e.g., “Who won a tennis match?”).

Forty-eight lure sentence pairs were constructed with the following syntactic forms: (i) 16 were identical to the NP1 experimental sentence pairs, with half the anaphors being pronouns and half being the names of NP1, (ii) 16 were identical to the NP2 experimental sentence pairs, with half the anaphors being pronouns and half being the names of NP2 and (iii) 16 had first sentences identical to the experimental sentence pairs, but the anaphors in the second sentences were the plural pronoun they, for example, “Bobby showed the new computer to David. After setting it up, they wanted to try it out.”

Sixteen material sets were formed. Within a material set, there was an equal number of experimental sentences in the 16 experimental conditions. Across material sets, each sentence occurred in all of its experimental conditions. Twelve subjects were randomly assigned to each material set; thus, each subject was exposed to an experimental sentence in only one of its conditions. The lure sentences occurred in the same randomly selected order on each material set.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to that of Experiment 3.

Results

The design of both the subjects’ and items’ ANOVAs was a 2 (Anaphor Type: name vs. pronoun) × 2 (Probe Name: antecedent vs. nonantecedent) × 2 (Test Point: immediately after the anaphors vs. at the ends of the sentences) × 2 (Antecedent Position: NP1-vs. NP2). In both sets of ANOVAs, all four factors were within-subjects (or items) factors.

Two main effects were significant, the same ones as in Experiment 3. Responses were faster to the antecedents (M = 888) than the nonantecedents (M = 989), minF’(1,133) = 171.18. And responses were faster immediately after the anaphors (M = 920) than at the ends of the sentences (M = 958), minF’(1,129) = 29.08.

Three interactions were also significant. First, as in Experiments 1, 2, and 3, antecedent position (NP1 vs. NP2) interacted with probe name, minF’(1,131) = 52.03, again demonstrating that, in general, first-mentioned participants were verified more rapidly (M = 909) than second-mentioned participants (M = 969).

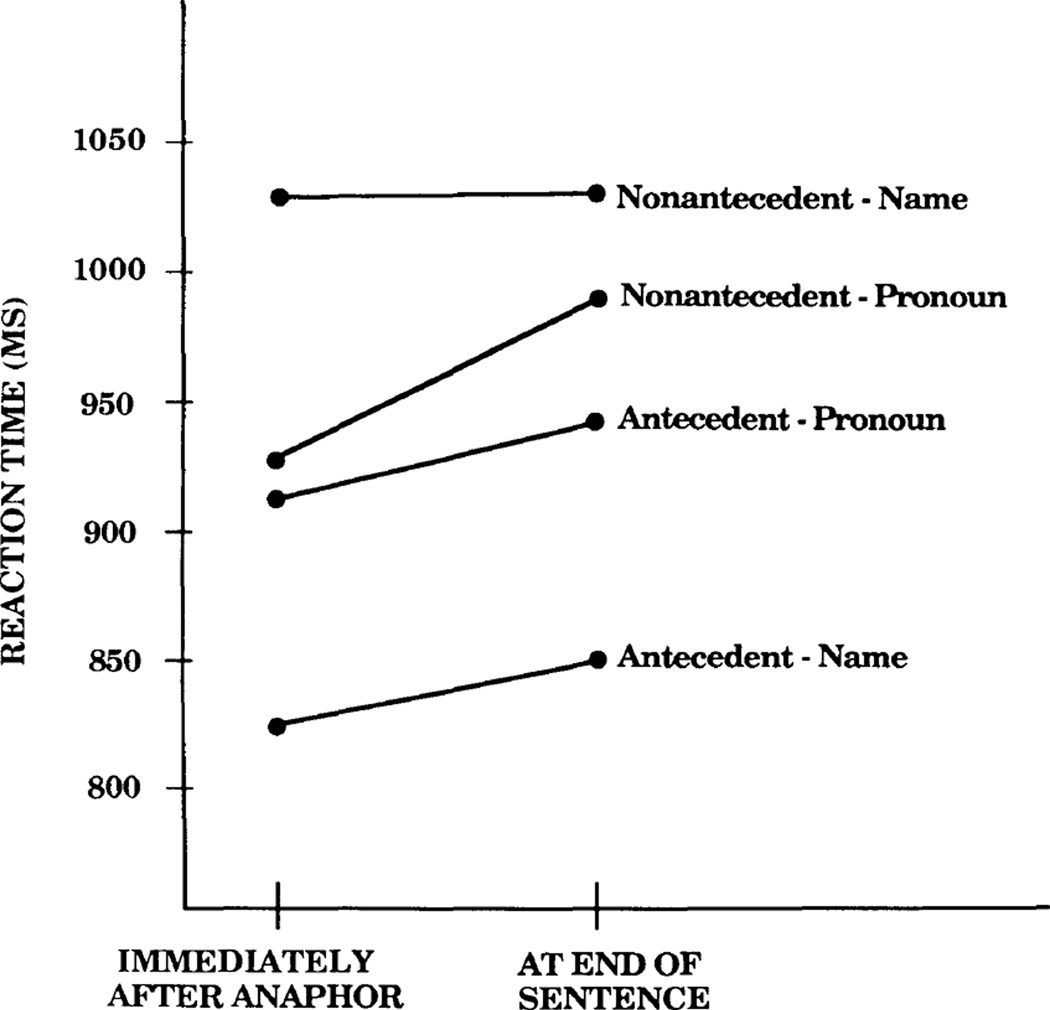

The second significant interaction also replicated Experiment 3. It was between probe name and anaphor type, minF’(1,170) = 128.66. And again it was qualified by the only other significant interaction, a three-way interaction involving probe name, anaphor type, and test point, minF’(1,127) = 6.881. The three-way interaction is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Subjects’ mean response times in Experiment 4.

As illustrated in Figure 4, when the probe names were the nonantecedents, anaphor type (name vs. pronoun) interacted with test point (immediately after the anaphors vs. at the ends of the sentences), minF’(1,133) = 6.746, in the following way: The difference between response times when the anaphors were names versus pronouns was larger immediately after the anaphors (102 ms) than at the ends of the sentences (49 ms). In contrast, when the probe names were the antecedents, anaphor type did not interact with test point, minF’ < 1; the difference between response times when the anaphors were names versus pronouns was about the same immediately after the anaphors as at the ends of the sentences.

This three-way interaction suggests, as it did in Experiment 3, that the combination of anaphor type and probe name most affected by test point was when the anaphors were pronouns, and the probe names were the nonantecedents. In other words, the activation of the pronouns’ nonantecedents changed the most across the second clauses of the sentences. As illustrated in Figure 4, this change resulted from the pronouns’ nonantecedents becoming less activated. One interpretation of this change is that the information provided by the pronouns, combined with the semantic information provided by the participial phrases, triggered the suppression mechanism.

Further analyses suggested that it was not the semantic information alone that triggered suppression. Had that been the case, then the pronouns’ nonantecedents should have been less activated at the earlier test point, because the semantic information had already occurred by then. However, at the early test point, response times to the pronouns’ antecedents versus nonantecedents were statistically indistinguishable, minF’(1,206) = 1.365, p > .25. In contrast, by the ends of the sentences, responses were significantly slower to the pronouns’ nonantecedents than their antecedents, minF’(1,152) = 5.749.

Discussion

Experiment 4, like Experiment 3, further illustrated the role that the mechanism of suppression plays in improving referential access. Experiment 4 also demonstrated that semantically-biased pronouns improve their antecedents’ accessibility by triggering the suppression of nonantecedents. In fact, Experiment 4 replicated Experiment 3, even though in Experiment 4 the semantic information occurred before the pronouns. However, like Experiment 3, the pronouns’ nonantecedents were not observably suppressed until the test point at the ends of the sentences. This suggests that semantic information alone is insufficient to trigger suppression. Rather, semantic information must be combined with information provided by the anaphor. And because pronouns—even pronouns biased by a previous semantic context—are less explicit than repeated name anaphors, suppression is triggered more slowly.

What if the pronouns were made more explicit? What if they matched the gender of only one of the two participants? If the mechanism of suppression is primarily triggered by the informational content of the anaphor, then gender-explicit pronouns should trigger suppression more rapidly or more powerfully.

Existing data support this prediction. For instance, a pronoun’s antecedent is overtly identified more rapidly when the pronoun matches the gender of only one participant, as in

-

(7)

John phoned Susan because he needed some information.

than when the pronoun matches the gender of more than one participant, as in

-

(8)

John phoned Bill because he needed some information.

(Caramazza, Grober, Garvey, & Yates, 1977; Erhlich, 1980; Vonk, 1985). Similarly, clauses containing gender-explicit pronouns (like the second clause of sentence (7)) are read more rapidly than identical clauses containing less explicit pronouns (like the second clause of sentence (8)) (Garnham & Oakhill, 1985). These data demonstrate that the antecedents of gender-explicit pronouns are more accessible.

Perhaps they are more accessible because gender-explicit pronouns trigger suppression more rapidly or more powerfully. More data to support this prediction come from a study by Chang (1980). Chang (1980) measured activation at the ends of sentences and found that the nonantecedents of gender-explicit pronouns were no more activated than the nonantecedents of repeated name anaphors. To account for Chang’s data, one can assume that the gender-explicit pronouns’ nonantecedents were never activated. Or one can assume that they were once as activated as the antecedents, but by the ends of the sentences they had been suppressed very powerfully. Experiment 5 empirically examined these alternatives.

Experiment 5

Experiment 5 was identical to Experiment 3 except that the two participants in each sentence differed in gender. (And therefore the pronouns matched the gender of only one participant). In all other respects, the two experiments were identical.

Method

The materials used in Experiment 5 were modified from those used in Experiment 3 by assigning a stereotypically female name to one of the two participants and a stereotypically male name to the other. The two names were matched for perceived familiarity and length in letters. Half the antecedents at each antecedent position were female, and half were male. Sixty-four subjects participated.

Results

The design of the ANOVAs was identical to Experiment 3. Two main effects were significant, the same two as in Experiments 3 and 4. First, responses were faster to the antecedents (M = 882) than the nonantecedents (M = 971), minF’(1,118) = 47.37. Second, responses were faster immediately after the anaphors (M = 912) than at the ends of the sentences (M = 941), minF’(1,99) = 4.409.

Three interactions were significant. As in the first four experiments, antecedent position interacted with probe name, minF’(1,118) = 8.068, again demonstrating that, in general, first-mentioned participants were verified more rapidly (M = 907) than second-mentioned participants (M = 946).

The second significant interaction was also the same as in Experiments 3 and 4. It was between probe name and anaphor type, minF’(1,116) = 45.56. And, as in Experiments 3 and 4, it was qualified by a three-way interaction involving probe name, anaphor type, and test point, minF’(1,118) = 6.564. This three-way interaction is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Subjects mean response times in Experiment 5.

As shown in Figure 5, when the probe names were the nonantecedents, anaphor type interacted with test point, minF’(1,117) = 7.925, creating the following effect: The difference between response times when the anaphors were names versus pronouns was greater immediately after the anaphors (101 ms) than at the ends of the sentences (25 ms). In contrast, when the probe names were the antecedents, anaphor type did not interact with test point, both Fs < 1; the difference between response times when the anaphors were names versus pronouns was about the same immediately after the anaphors as at the ends of the sentences.

Further analyses examined the data from the pronoun conditions only. Immediately after the pronouns, response times to the pronouns’ antecedents versus nonantecedents were statistically indistinguishable, both Fs < 1. Thus, despite a strong cueing by gender, the pronouns had no immediate effect on either their antecedents or nonantecedents. This finding corroborates Tyler and Marslen-Wilson (1982), who found that pronouns matching the human status of only one participant did not immediately affect the activation of their antecedents or nonantecedents.

In contrast, by the ends of the sentences in Experiment 5, responses were significantly slower to the pronouns’ nonantecedents than their antecedents, F1(1,56) = 5.256, F2(1,62) = 3.778. In other words, by the ends of the sentences, the pronouns’ antecedents and nonantecedents differed in their levels of activation. As in Experiments 3 and 4, the clearest interpretation of this pattern is that the information provided by the pronouns, combined with the semantic information provided by the second clauses, triggered the suppression of the nonantecedents.

However, in contrast to Experiments 3 and 4, the data collected at the ends of the sentences replicate Chang (1980). Recall that Chang found that at the ends of the sentences the pronouns’ nonantecedents were activated at the same level as the names’ nonantecedents. Similarly, at the ends of the sentences in Experiment 5, responses to the pronouns’ nonantecedents versus the names’ nonantecedents differed by only a marginally significant 25 ms, minF’(1,86) = 3.22, p < .10. Actually, Chang’s data can be approximated even more closely by considering only the Experiment 5 data for the antecedent position that he tested; for those data, the difference was a nonsignificant 12 ms. Thus, the pronouns’ greater explicitness more powerfully triggered the suppression of their nonantecedents.

Discussion

Experiment 5 further illustrated the role that the mechanism of suppression plays in improving referential access. Experiment 5 demonstrated that gender-explicit pronouns also trigger the suppression of their nonantecedents, and when compared to Experiments 3 and 4, they do so more powerfully than gender-ambiguous pronouns.

How general is the role that the suppression mechanism plays in improving referential access? That is, is it only rementioned participants who improve their accessibility by triggering the suppression of other participants? Or is the mechanism’s role more general so that simply the most recently mentioned participants—regardless of whether they are reinstated or novel—trigger suppression in order to improve their accessibility? Experiment 6 answered these questions.

Experiment 6

The experimental sentences in Experiment 6 were similar to those in Experiment 1; in fact, in one condition of Experiment 6, the sentences were identical to the Experiment 1 name-anaphor sentences, for example:

-

(9)

Bill handed John some tickets to a concert, but Bill took the tickets back immediately.

However, in another condition, the sentences were modified: Instead of one of the two original participants being rementioned at the beginning of their second clause, a new participant was introduced, as in

-

(10)

Bill handed John some tickets to a concert, but Mark said the tickets were counterfeit.

Three variables were manipulated. In the interest of simplicity, though not accuracy, one will be referred to as “anaphor” type. This variable simply refers to who the subjects of the second clauses were. Half the time the “anaphors” were repeated, anaphoric, or what will be referred to as “old” names. An example is the rementioned Bill in sentence (9) above. The other half of the time the “anaphors” were new names, for example, the newly introduced Mark in sentence (10) above. In this second situation, the label “anaphors” was clearly a misnomer. Manipulating this variable revealed whether introducing a new participant (e.g., Mark) had the same effect on the other participant (e.g., John) as re mentioning an old participant (e.g., Bill).

The second variable was probe name: The probe names were the names of either the antecedents or the nonantecedents. This variable also lost its meaning when the “anaphors” were new names. Given that the new names were not truly anaphors, they had neither antecedents nor nonantecedents. So the distinction boiled down to a comparison between the two original participants. When the “anaphors” were the new names, no differences between response times to the two original participants were expected. But the distinction was preserved in the interest of a balanced experimental design. Finally, the third variable was antecedent position: The antecedents were either the NP1 or the NP2 of the first clause.

To summarize, the three variables were “anaphor” type (whether the “anaphors” were old names or new names), probe name, and antecedent position. Unlike the previous five experiments, test point was not manipulated. Because the experimental question was whether the effects on previously mentioned participants are the same after introducing new participants versus rementioning old participants, response times were measured at only one test point: immediately after the “anaphors” (i.e., immediately after either NP1 or NP2 was repeated or NP3 was introduced). An example experimental sentence of both antecedent position types appears in Table 3.

Table 3.

Example stimulus sentences for Experiment 5

| NP1 type sentence |

| OLD NAME - ANTECEDENT (BILL) |

| Bill handed John some tickets to a concert but Bill took the tickets back immediately. |

| NEW NAME - “ANTECEDENT” (BILL) |

| Bill handed John some tickets to a concert but Mark said the tickets were counterfeit. |

| OLD NAME - NONANTECEDENT (JOHN) |

| Bill handed John some tickets to a concert but Bill took the tickets back immediately. |

| NEW NAME - “NONANTECEDENT” (JOHN) |

| Bill handed John some tickets to a concert but Mark said the tickets were counterfeit. |

| NP2 type sentence |

| OLD NAME - ANTECEDENT (PAM) |

| Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race but Pam came in first very easily. |

| NEW NAME - “ANTECEDENT” (PAM) |

| Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race but Jan predicted that Pam would win. |

| OLD NAME - NONANTECEDENT (ANN) |

| Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race but Pam came in first very easily. |

| NEW NAME - “NONANTECEDENT” (ANN) |

| Ann predicted that Pam would lose the track race but Jan predicted that Pam would win. |

Note: For each sentence, the probe name appears in parentheses, and the “anaphor” is in italics.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 48 undergraduates at the University of Oregon.

Materials and design

The materials were modified from the sentences used in Experiment 1 in the following ways. First, for each experimental sentence, an alternative second clause was written that introduced a new participant. The new participant’s name matched the original two participants’ names in perceived familiarity, length in letters, and gender.

Second, the comprehension questions were reconstructed. Half the questions were about the first clause, and half were about the second clause. The questions were about the first clause whenever the “anaphors” were the new names. And, as a finer division, half of these questions were about the first-mentioned participants’ activity (e.g., “Who handed someone some tickets?”), and half were about the second-mentioned participants’ activity (e.g., “Who was handed some tickets?”). The questions were about the second clause whenever the “anaphors” were the old names (e.g., “Who took the tickets back immediately?”).

Third, 24 of the 48 lure sentences were reconstructed so that they too introduced a third participant. In addition, in 12 of the lure sentences the probe names were tested toward the ends of their sentences, and, in another 12, the probe names were tested toward the beginnings of their sentences. As in Experiments 1 and 2, this variation was intended to discourage subjects from expecting the probe names to be tested always in the middle of the sentences.

Four material sets were formed. Within a material set, there was an equal number of experimental sentences in each of the four experimental conditions. Across material sets, each sentence occurred in all four experimental conditions. Twelve subjects were randomly assigned to each material set so that each subject was exposed to an experimental sentence in only one of its experimental conditions. The lure sentences occurred in the same randomly selected order on each material set.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to Experiment 1, with the major exception that all the probe names were presented 150 ms after the offset of the “anaphors.”

Results

The subjects’ average correct response times are shown in Table 4. The design of both the subjects’ and items’ ANOVAs was a 2 (“Anaphor” Type: old name vs. new name) × 2 (Probe Name: antecedent vs. nonantecedent) × 2 (Antecedent Position: NP1 vs. NP2). In the subjects’ analysis, all three factors were within-subjects factors. In the items’ analysis, antecedent position was a between-items factor.

Table 4.

Average correct response times in Experiment 6

| Probe type | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent | Nonantecedent | ||

| “Anaphor” type | Old name | 851 | 1018 |

| New name | 1005 | 1009 | |

Two main effects were significant. The first was an effect of probe name: Responses were faster to antecedents (M = 928) than nonantecedents (M = 1013), minF’(1,106) = 29.95. The second was an effect of “anaphor” type: Responses were faster following old names (M = 934) than new names (M = 1007), minF’(1,104) = 33.10.

Two interactions were significant. The first was the familiar antecedent position by probe name interaction, minF’(1,101) = 10.81, again demonstrating that, in general, first-mentioned participants were verified more rapidly (M = 943) than second-mentioned participants (M = 998).

The other interaction was between “anaphor” type and probe name, minF’(1,103) = 35.51. This interaction indicated that the effect of probe name was greater when the “anaphors” were old names than it was when they were new names. In fact, when the “anaphors” were new names, there was no effect of probe name: Response times to the antecedents were statistically indistinguishable from response times to the nonantecedents, both Fs < 1. As mentioned above, this was expected as when the “anaphors” were new names, as in sentence (10) above, the distinction between antecedents and nonantecedents was meaningless. On the other hand, when the anaphors were old names, responses were faster to the antecedents than the nonantecedents, minF’(1,93) = 59.64. Replicating the previous five experiments, this suggests that name anaphors improve their antecedents’ accessibility, most likely by triggering the mechanisms of suppression and enhancement.

Other planned comparisons suggested that suppression was not limited to anaphoric names; introducing new participants also triggered the mechanism. That is, response times to the nonantecedents following old names were statistically indistinguishable from response times to either the new-name antecedents or the new-name nonantecedents, all Fs < 1. Although, of course, responses to the antecedents following old names were significantly faster than responses to either the new-name antecedents or the new-name nonantecedents, minF’(1,102) = 60.01 and minF’(1,106) = 56.78, respectively.

Discussion

Experiment 6 further illustrated the role that the mechanism of suppression plays in improving referential access. Experiment 6 demonstrated that rementioned participants are not the only ones who gain a privileged status by triggering the suppression of other participants. Rather, simply the most recently mentioned participants, regardless of whether they are new or old, use this mechanism to improve their referential access.

In fact, this suppression mechanism is probably not limited to participants either. Most likely the mechanism is triggered by concepts in general. Several studies support this proposal.

For instance, data from Dell et al. (1983) can be interpreted as demonstrating that new concepts trigger the suppression of previously mentioned concepts. In their study, subjects read four-sentence texts whose first lines contained a critical noun phrase, for example, a burglar as in

-

(11)

A burglar surveyed the garage set back from the street.

In one condition, the texts’ fourth lines contained an anaphoric noun phrase, which was a semantic superordinate of the critical noun phrase, for example,

-

(12)

The criminal slipped away from the street lamp.

Responses to the critical noun phrases (e.g., burglar) were slightly (12 ms) faster immediately after subjects read the anaphors (e.g., criminal) than immediately before. In other words, the noun phrase anaphors appeared to trigger the enhancement of their antecedents.

In a second condition, the anaphoric noun phrases in the fourth line were replaced with novel noun phrases, for example, a cat as in

-

(13)

A cat slipped away from the street lamp.