Abstract

Background

The effectiveness of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) in preventing brain metastases in patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is unclear.

Methods

Preclinical studies were conducted to determine the steady-state brain and plasma concentrations of sorafenib and sunitinib in mice deficient in the drug efflux transporters, p-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP). A single-institution retrospective analysis of patients treated from 2008 to 2010 was conducted to assess the incidence of brain metastases before and during TKI treatment

Results

Transport of sorafenib and sunitinib across the blood-brain barrier was restricted. Retrospective analysis revealed that median time to develop metastatic brain disease was 28 months (range:1-108) while on TKI therapy and 11.5 months (range:0-64) in patients not receiving TKI therapy.

The incidence of brain metastases per month in patients not treated with TKI therapy was 1.6 higher than the incidence in patients treated with TKI therapy.

Conclusions

Penetration of sorafenib or sunitinib through intact blood-brain barrier to brain tissue is limited; however, the incidence of brain metastases per unit time is decreased in patients on TKI therapy in comparison to the “cytokine” era.

Keywords: sorafenib, sunitinib, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, brain metastases, renal cell carcinoma, ATP-binding cassette drug efflux transporters, ABCB1, ABCG2, p-glycoprotein, breast cancer resistance protein

INTRODUCTION

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common histological type of kidney cancer, and almost 30% of cases are metastatic at the time of diagnosis [1]. The five-year survival rate of metastatic RCC is less than 10% [2]. RCC is considered to be a chemo-resistant tumor and before the era of targeted therapy, cytokine treatment with interferon or interleukin-2 was the most commonly offered treatment for this cancer [3]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as sunitinib, sorafenib, and pazopanib have improved overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with advanced RCC [4]. VEGF is considered to be the most potent pro-angiogenic protein in tumor angiogenesis. In RCC, VEGF expression is associated with inactivation of the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene, and the majority of clear cell RCC tumors demonstrate VHL inactivation [5].

Historically, brain metastases in RCC patients are associated with poor prognosis and a median survival of approximately 1-10 months after diagnosis [6-7]. Currently, there are no standard guidelines for screening RCC patients for brain metastases, and clinical data on the effectiveness of TKIs against RCC brain metastases is limited. In one case series sunitinib was found to elicit partial responses in metastatic tumors [6], and in a phase III trial sorafenib was found to reduce the occurrence of brain metastases [8]. However, there is evidence that the accumulation of TKIs in the brain may be reduced by ATP-binding cassette (ABC) drug efflux transporters [9]. Indeed, p-glycoprotein (P-gp, also known as ABCB1) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP, ABCG2) in brain tissue have been shown to work in concert to restrict brain penetration of several TKIs [10-12]. P-gp is dominant in limiting transport of many dual P-gp/BCRP substrates across the blood-brain barrier [13-14]. Both these proteins are expressed on human brain microvascular endothelial cells comprising the blood-brain barrier [15-16], and therefore could potentially prevent TKIs from inhibiting tumor growth by making these cells relatively resistant to VEGF TKI by means of enhanced efflux of these molecules from brain endothelial cells. In our own clinical practice, we were intrigued by the seemingly increased number of patients with metastatic RCC who developed brain metastases during oral TKI therapy with sunitinib or sorafenib. Although this could possibly be explained by the fact that RCC patients live longer, we hypothesized that oral TKI therapy may not prevent the growth of microscopic brain metastases that existed prior to treatment. In order to address this hypothesis, we performed preclinical analyses of sorafenib and sunitinib distribution in brain tissue. Additionally, we evaluated the incidence of brain metastases in RCC patients treated with TKIs versus cytokines in a meta-analysis of the medical literature and a retrospective analysis of patients treated at our institution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Steady-State Brain Distribution of Sorafenib and Sunitinib

We determined the steady-state brain and plasma concentrations of sorafenib and sunitinib in FVB wild-type, and Abcb1a/b−/−Abcg2−/−mice (P-gp/BCRP deficient, n=4 each). Sorafenib and sunitinib were infused at a constant rate in the peritoneal cavity by using Alzet Osmotic Minipumps (model 1003D; Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA), as previously described [10]. Briefly, minipumps were filled with a 30 mg/ml solution of sorafenib or sunitinib in DMSO and then equilibrated by soaking them overnight in sterile saline solution at 37°C. Each minipump operated at a flow rate of 1 μL/hr yielding an infusion rate of 30 μg/hour (1 mg/hour/kg). Mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane (Boynton Health Service Pharmacy, Minneapolis, MN) and were maintained under anesthesia with 2% isoflurane in oxygen. Each primed pump was inserted into the peritoneal cavity. After 48 hours, mice were euthanized by using a CO2 chamber. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and whole brain was harvested. Plasma was obtained by centrifuging the blood sample at 7500 rpm for 10 minutes. Plasma and brain specimens were stored at –80 °C until analysis by LC-MS/MS. The LC-MS/MS methods for sunitinib (manuscript in preparation)and sorafenib [17]. Were developed and validated before analysis. All sunitinib experiments were performed in light-protected conditions. Experiments were performed according to a protocol approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Retrospective review

We conducted a database search of patients treated at University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center between August 2008 and August 2010. We included patients with clear cell, sarcomatoid, papillary, urothelial, and unclassified features on histological examination. Medical records review was conducted to extract the following information: age, gender, nephrectomy status, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center risk score, treatment with TKIs (sunitinib, sorafenib, or pazopanib), development of brain metastasis, and duration of follow-up. To evaluate the potential effect of TKIs on brain metastases, patients were divided into the following groups: patients who developed a brain metastasis during treatment with TKI and patients who had a preexisting brain metastasis diagnosed before the start of TKI treatment. Survival calculations included all patients treated with TKIs regardless of when they received the agent relative to the development of brain metastasis. Overall survival curves were estimated for patients with and without brain metastases using Kaplan-Meier estimation and compared using the log-rank test. In order to identify predictors of overall survival, Cox proportional hazards regression models were used. This retrospective analysis was approved by Institutional Review Board of University of Minnesota.

RESULTS

Brain levels of sorafenib and sunitinib

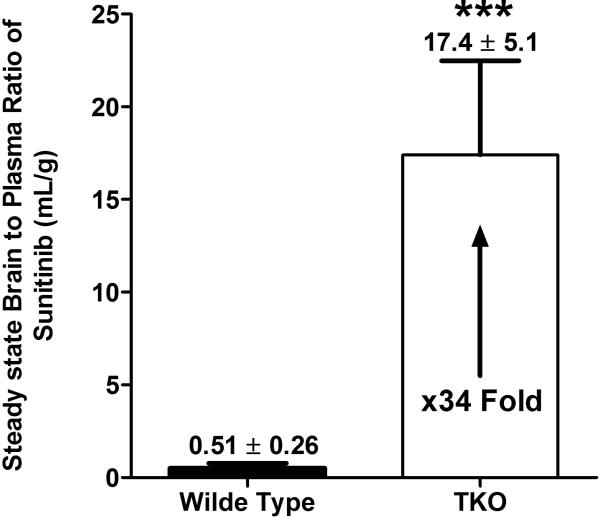

We first examined whether P-gp and BCRP were involved in the active efflux of sorafenib and sunitinib from the brain by determining the steady-state brain and plasma concentrations of these drugs in wild-type and Abcb1a/b−/−Abcg2−/−mice. The steady-state plasma concentrations of sorafenib were approximately 1 μg/ml in wild-type and Abcb1a/b−/−Abcg2−/−mice. However, the steady-state brain concentration of sorafenib was 0.13 ± 0.07 μg/ml in wild-type mice but was significantly higher at 1.64 ±0.31 μg/ml in Abcb1a/b−/−Abcg2−/−mice (p< 0.05). The steady-state brain-to-plasma (B/P) ratio for sorafenib was approximately 14-fold higher in Abcb1a/b−/−Abcg2−/− mice than in wild-type mice (p< 0.05, Figure 1A). Similar results were seen with sunitinib, where the steady-state plasma concentrations were 0.196 μg/ml and 0.264 μg/ml in wild-type Abcb1a/b−/−Abcg2−/−mice, respectively. The steady-state brain concentration was 0.09 ± 0.06 μg/ml in wild-type mice, but was over 50-fold higher at 4.46 ± 1.66 μg/ml in Abcb1a/b−/−Abcg2−/− mice (p< 0.05) (Table 1). The corresponding B/P ratio in wild-type and Abcb1a/b−/−Abcg2−/− mice was 0.51 ± 0.26 and 17.4 ± 5.0, respectively (p< 0.05, Figure 1B). For all mice, differences between brain and plasma concentrations were statistically different (p< 0.05). Taken together, these data show that the absence of P-gp and BCRP at the blood brain barrier leads to a marked increase in the concentrations of sorafenib and sunitinib in the brain of Abcb1a/b−/−Abcg2−/−mice, suggesting that these drug efflux transporters restrict the movement of sorafenib and sunitinib across the blood-brain barrier.

Figure 1.

Steady state brain-to-plasma ratio of sorafenib (A) and sunitinib (B) in wild-type and Abcb1a/b−/−Abcg2−/− (TKO) mice. Drugs were delivered at a constant rate of 1 mg/hr/kg, and the ratio of the brain and plasma concentrations at 48 hrs was determined. Data represent mean ± SD; n=4 for all data points. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.0001. 95%C.I. = confidence interval calculates as (estimate ± 1.96*standard deviation/sqrt(n))

Table 1.

Steady state plasma and brain concentrations of sorafenib and sunitinib in FVB wild-type and Abcb1a/b−/− Abcg2−/− mice (TKO).

| Drug | Plasma Concentration (μg/mL) | Brain Concentration (μg/gm) | Brain-to-Plasma ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVB - WT | TKO | FVB - WT | TKO | FVB - WT | TKO | |

| Sorafenib | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.2a | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 1.6 ± 0.3b | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 1.5 ± 0.2b |

| Sunitinib | 0.19 ± 0.16 | 0.26 ± 0.09a | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 4.5 ± 1.7b | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 17.4 ± 5.1b |

not significantly different from wild-type mice (p > 0.05)

significantly different compared to the wild-type mice (p < 0.05)

TKO indicate mice lacking both p-gp and Bcrp (Abcb1a/b−/− Abcg2−/− mice)

Retrospective analysis of RCC patients treated at the University of Minnesota

A total of 92 patients with a diagnosis of RCC were identified as being treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors between August 2008 and August 2010 (Table 2). A large majority of patients had stage IV disease, and 21 patients had brain metastases. Brain metastases were treated gamma knife radiation in 17 patients, in 2 patients treatment consisted of whole brain radiation, and one patient was treated with surgical resection followed by whole brain radiation. One patient did not receive local brain metastases therapy. Patients who developed brain metastases during the course of treatment had a lower median survival (33 months, 95% CI= 17-63 months) than patients without brain metastases (80 months, 95% CI= 56-inestimable months) (Figure 2). Factors associated with better survival included having a MSKCC risk score other than “poor” (hazard ratio = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.14, 0.63) and longer time from diagnosis to TKI treatment (hazard ratio per month = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.94, 0.99). Of the 21 patients with brain metastases, 13 developed metastatic disease while on TKI therapy and the remaining 8 developed before TKI treatment. The median time to develop metastatic brain disease was 28 months (range, 1-108) while on TKI treatment and 11.5 months (range, 0-64) before TKI therapy ( p=0.08). The incidence of brain metastases per month before TKI was 0.0497, and incidence of brain metastases per month while on TKI therapy was 0.0317, with a per month incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 1.568 (95% CI: 1.06, 2.33).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics (n=92)

| Age | 59.5 +/− 11.1 y |

| Sex | |

| Male | 66 (71.7%) |

| Female | 26 (28.3%) |

| Histology | |

| Clear Cell | 75 (81.5%) |

| Other | 17 (18.5%) |

| MSKCC Score | |

| Favorable | 13 (14.1%) |

| Intermediate | 51 (55.4%) |

| Poor | 23 (25.0%) |

| Other | 5 (5.5%) |

| Disease Stage | |

| I | 1 (1.1%) |

| II | 1 (1.1%) |

| III | 9 ( 9.8%) |

| IV | 81 (88.0%) |

| Surgery | |

| Neph & Lym | 3 (3.3%) |

| Nephrec | 3 (3.3%) |

| Par neph | 1 (1.1%) |

| NA | 85 (92.4%) |

Figure 2.

Overall survival curves were estimated for TKI-treated patients with or without brain metastases using Kaplan-Meier estimation and compared using the log-rank test.

DISCUSSION

The present study found that the transport of sorafenib and sunitinib across the blood-brain barrier was markedly restricted by P-gp and BCRP. The B/P ratio of sorafenib and sunitinib was approximately 14-fold and 34-fold higher in mice deficient in P-gp and BCRP than in wild-type mice. This finding shows that active efflux of TKIs is mediated by P-gp and BCRP and is an important determinant of TKI transport to the brain that could potentially influence its therapeutic activity in the brain. These findings are consistent with our previous report for sorafenib [10] and with those by Tang et al [11].

In our retrospective study, we found that patients developed brain metastases a median of 16.5 months later while on TKI therapy than patients not on TKI therapy and developed about 20% fewer brain metastatic tumors while on TKI therapy than patients who ddi not receive TKI therapy. Thus, we conclude that there may be fewer metastatic events discovered in the brain per unit of time in the era of TKI therapy as compared to cytokine era.

In a literature review, we identified studies by searching the MEDLINE and EBSCO databases using the mesh terms “carcinoma, renal cell” and key words “renal cell carcinoma and “brain metastasis”. We limited the search to English language reports published between January, 1980 and April, 2011. Trials were reviewed if the prevalence of brain metastases from RCC could be directly abstracted or calculated and were excluded if the study sample size was less than 50. In a review of the literature, we identified 12 studies describing 9752 RCC patients and found that the prevalence of brain metastases before and after 2005, when TKIs were first introduced, remained relatively unchanged at approximately 9% (pooled prevalence of brain metastases was 8.5% (95%CI 7.1-10%) in cytokine era and 9.7% (95%CI 4.7-18.8%) in the kinase inhibitors era) (Table 3). We also examined PFS and OS data from 5 available studies from both time periods. PFS was comparable in all the studies, but OS in our retrospective study from the TKI era was much higher than historical data (33 vs 9.2-13.4 months). The median PFS and OS after the diagnosis of brain metastasis ranged from 3.6-8.7 months and 6.2-33.0 months, respectively, as reported in 5 studies (Table 4).

Table 3.

Prevalence of brain metastases in patients with renal cell carcinoma

| Cytokine Era | Kinase Inhibitors Era | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Study sample (n) | Brain metastasis (n) | Prevalence (%) | Study sample (n) | Brain metastasis (n) | Prevalence (%) | P-value |

| Saitoh (1981)1 | 1451 | 144 | 9.92 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Kavolius (1998)2 | 278 | 21 | 7.55 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Harada (1998)3 | 325 | 18 | 5.54 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Mai (2001)4 | 348 | 19 | 5.46 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Shuch (2008)5 | 1855 | 138 | 7.44 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Gore (2009)6 | 4371 | 321 | 7.34 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Steiner (2010)7 | 61 | 6 | 9.84 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Vogl (2010)8 | 114 | 12 | 10.53 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Elfiky (2010)9 | 71 | 6 | 8.45 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Massard (2010)10 | 69 | 8 | 11.59 | 70 | 2 | 2.86 | 0.07 |

| Verma (2011)11 | 184 | 29 | 15.76 | 154 | 15 | 9.74 | 0.10 |

| Dudek (present) | -- | -- | -- | 92 | 15 | 16.30 | -- |

Table 4.

Survival rates after the diagnosis of brain metastasis

| Author (year) | Brain Metastasis (n) | PFS (months) | OS (months) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gore (2009)6 | 321 | 5.6 | 9.2 |

| Vogl (2010)8 | 12 | 8.7 | 13.4 |

| Elfiky (2010)9 | 6 | 3.62 | 12.47 |

| Verma (2011)11 | 15 | NA | 6.15 |

| Dudek (present) | 15 | 5 | 33 |

Study Limitation and Conclusion

Although our preclinical data suggests that there is limited penetration of sorafenib or sunitinib into brain tissue in the normal brain, this result might be different in brain with RCC metastases, where the blood-brain barrier vasculature is leaky [18-20]. In addition, although markedly suppressed by TKI therapy, a steady seeding of cancer cells from other metastatic sites to the brain may cause less metastatic brain disease per unit of time in patients with metastatic RCC who live longer, resulting in the same overall prevalence of brain metastases in the current era as compared to the cytokine era. We recognize that there are several limitations to our conclusions. Not only are the data for our study and studies in the meta-analysis of a retrospective nature but the controls were taken from historical literature across three decades. In addition, the prevalence of brain metastases was compared between the cytokine era and TKI era, but the inability to extract “incidence per year” in the meta-analysis made interpreting these data challenging. Finally, due to the significant variation in patient samples and study design, the statistical power of heterogeneity testing is expected to be low. In conclusion, TKI therapy may not prevent the occurrence of brain metastases, but it may delay progression of clinically significant disease in brain.

Clinical Practice Points.

TKI therapy may not prevent the occurrence of brain metastases, but it may delay progression of clinically significant disease in the brain.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Michael J. Franklin for editorial support.

Sources of funding: none

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Verma J, et al. Impact of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on the incidence of brain metastasis in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggener SE, et al. Renal cell carcinoma recurrence after nephrectomy for localized disease: predicting survival from time of recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(19):3101–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Bander NH, Nanus DM. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(12):865–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609193351207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gore ME, et al. Sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients with brain metastases. Cancer. 2011;117(3):501–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rini BI, Small EJ. Biology and clinical development of vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy in renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(5):1028–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shuch B, et al. Brain metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: presentation, recurrence, and survival. Cancer. 2008;113(7):1641–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harada Y, et al. Clinical study of brain metastasis of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 1999;36(3):230–5. doi: 10.1159/000068003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massard C, et al. Incidence of brain metastases in renal cell carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(5):1027–31. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang SC, et al. Brain accumulation of sunitinib is restricted by P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) and breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) and can be enhanced by oral elacridar and sunitinib coadministration. Int J Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ijc.26000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polli JW, Olson KL, Chism JP, John-Williams LS, Yeager RL, Woodard SM, Otto V, Castellino S, Demby VE. An unexpected synergist role of P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein on the central nervous system penetration of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib (N-{3-chloro-4-[(3-fluorobenzyl)oxy]phenyl}-6-[5-({[2-(methylsulfonyl)ethyl]amino}methyl)-2-furyl]-4-quinazolinamine; GW572016). Drug Metab Dispos. 2009 Feb;37(2):439–42. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.024646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou L, Schmidt K, Nelson FR, Zelesky V, Troutman MD, Feng B. The effect of breast cancer resistance protein and P-glycoprotein on the brain penetration of flavopiridol, imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), prazosin, and 2-methoxy-3-(4-(2-(5-methyl-2-phenyloxazol-4-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)propanoic acid (PF-407288) in mice. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009 May;37(5):946–55. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.024489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elmeliegy MA, Carcaboso AM, Tagen M, Bai F, Stewart CF. Role of ATP-binding cassette and solute carrier transporters in erlotinib CNS penetration and intracellular accumulation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Jan 1;17(1):89–99. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dai H, Marbach P, Lemaire M, Hayes M, Elmquist WF. Distribution of STI-571 to the brain is limited by P-glycoprotein-mediated efflux. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1085–1092. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.045260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Agarwal S, Shaik NM, Chen C, Yang Z, Elmquist WF. P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein influence brain distribution of dasatinib. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:956–963. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.154781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Declèves X, Regina A, Laplanche JL, Roux F, Boval B, Launay JM, Scherrmann JM. Functional expression of P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated protein (Mrp1) in primary cultures of rat astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2000 Jun 1;60(5):594–601. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000601)60:5<594::AID-JNR4>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo YC, Lu CH. Expression of P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated protein on human brain-microvascular endothelial cells with electromagnetic stimulation. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2012 Mar 1;91:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal S, et al. The role of the breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) in the distribution of sorafenib to the brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336(1):223–33. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arshad F, Wang L, Sy C, Avraham S, Avraham HK. Blood-brain barrier integrity and breast cancer metastasis to the brain. Patholog Res Int. 2010 Dec 29;2011:920509. doi: 10.4061/2011/920509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J, Baird A, Eliceiri BP. In vivo measurement of glioma-induced vascular permeability. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;763:417–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-191-8_28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Budde MD, Gold E, Jordan EK, Frank JA. Differential microstructure and physiology of brain and bone metastases in a rat breast cancer model by diffusion and dynamic contrast enhanced MRI. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012 Jan;29(1):51–62. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9428-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]