Abstract

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies of the risk of HIV-1 transmission per heterosexual contact. The search to September 2008 identified 43 publications based on 25 different study populations. Pooled female-to-male (0·0004,95%CI=0·0001-0·0014) and male-to-female (0·0008,CI=0·0006-0·0011) transmission estimates in developed countries reflected a low risk of infection in the absence of antiretrovirals. Developing country female-to-male (0·0038,CI=0·0013-0·0110) and male-to-female (0·0030,CI=0·0014-0·0063) estimates in absence of commercial sex(CS) work were higher. In meta-regression analysis, the infectivity across estimates in absence of CS work was significantly associated with gender, setting, the interaction between setting and gender and HIV prevalence. The pooled receptive anal intercourse estimate was much higher (0·017,CI=0·003-0·089). Estimates for the early and late phase of HIV infection were 9·2(CI=4·5-18·8) and 7·3(CI=4·5-11·9)-fold larger than for the asymptomatic phase, respectively. After adjusting for CS exposure, presence or history of genital ulcers in either couple member increased per-act infectivity 5·3(CI=1·4-19·5)-fold compared to no sexually transmitted infection. Study estimates among non-circumcised men were at least twice those among circumcised men. Developing country estimates were more heterogeneous than developed country estimates, which indicates poorer study quality, greater heterogeneity in risk factors or under-reporting of high-risk behaviour. Efforts are needed to better understand these differences and quantify infectivity in developing countries.

INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, mother-to-child transmission and iatrogenic transmission through contaminated blood products and unsafe injections have decreased due to improved health procedures and treatment options, especially in developed countries1-5. However, the notion that different patterns of sexual behaviours and/or biological factors such as male circumcision and genital ulcer disease (GUD) can explain worldwide differences in heterosexual epidemic size has recently been questioned6-9. Some believe that sexual transmission has been overestimated, while iatrogenic transmission has been underestimated10-12. Quantifying the risk of HIV infection following sexual intercourse with an infected partner is important to better understand the epidemiology of HIV infection worldwide and to take appropriate public health decisions.

Sexual transmission estimates fall broadly into two categories: per-act transmission probabilities13-23, which quantify the risk of infection per sexual contact, and per-partner transmission probabilities13,24-27, which measure the cumulative risk of infection over many sex acts during a partnership. In both cases, transmission probabilities depend upon the infectiousness of the HIV-infected partner and the susceptibility of the HIV-uninfected partner. Infectiousness and susceptibility depend on behavioural, biological, genetic and immunological risk factors of the host and/or the virus5-6,21-24,28-42. Per-act transmission probabilities are methodologically difficult to measure43. The time of seroconversion of the index case and the transmission to his/her partner, the number of unprotected sex acts, duration of exposure to HIV and potential HIV cofactors among the index cases and the susceptible partners at the time of transmission are rarely known precisely, especially for time-varying cofactors such as recurrent sexually transmitted infections (STI)5,16,43-45.

Early narrative or methodological reviews have reported a limited selection of per-act estimates10-12,42,46-48. More recently, Powers et al49 published a systematic review of per-act HIV-1 transmission probabilities of 27 articles based on 15 unique study populations. Our systematic review extends this work by including 43 publications based on 25 different study populations. Our objectives were to provide summary estimates of HIV-1 transmission probabilities per heterosexual contact, to perform in-depth univariate and multivariate meta-regression analyses to explore the variation across study estimates, and to estimate the influence of key risk factors on infectivity. The review focuses on HIV-1 which is more pathogenic and prevalent than HIV-250-51.

METHODS

Search strategy

The literature search to September 6th 2008 was conducted in three stages. First, PubMed, Science Direct and NLM Gateway online databases were searched to September 2006 using search terms: "HIV transmission probability" OR "HIV transmission probabilities" OR "HIV infectivity" OR "HIV infectiousness" NOT "perinatal" NOT "mother to child" NOT "mother-to-child" and by replacing "HIV" by the terms, "LAV", "HTLV-III" and "HTLV III". PubMed was searched by titles. Science Direct and NLM Gateway were searched by abstracts, titles, keywords and authors. The PubMed search was updated twice (to June 29th 2007, and again to September 6th 2008) using more efficient search terms and Boolean operators, for matches under any field: (HIV OR LAV OR HTLV III OR HTLV-III OR AIDS OR human immunodeficiency virus OR human T-lymphotropic virus III OR acquired immunodeficiency) AND (infectiousness OR infectivity OR probability OR contact OR contacts OR partner OR partners OR wives OR spouses OR husbands OR couples OR discordant OR (transmission AND (heterosexual OR homosexual OR risk OR female OR male OR anal))). Bibliographies of relevant articles were examined for additional references. Four of six authors contacted provided complementary information.

Selection criteria and data extraction

Publications reporting empirical per-act heterosexual HIV-1 transmission probability estimates, or sufficient information to derive one were included. Indirect estimates from mathematical modelling studies, reviews, pre-1990 abstracts, and studies with sample sizes fewer than ten were excluded. No other restrictions were put on language, location, study design or type of exposure. Each publication was examined by two reviewers(RFB,MCB) to extract information on per-act estimates (denoted pi for the ith study), 95%CI, as well as study and participant characteristics, which were used to define covariates. M-to-F and F-to-M estimates were extracted preferably to estimates combining gender(C). Per-act estimates stratified by anal intercourse, genital ulcers, disease stage of the index cases, male circumcision status, and viral load were also extracted.

Meta-analysis

Pooled transmission probability estimates and 95%CI were derived using a random effects model based on the inverse variance method52-54. Natural log (ln)-transformed study estimates were used to avoid problems associated with heteroscedasticity55. If not explicitly stated in the publication, per-act transmission probabilities were derived using reports of total or frequency of sexual contacts. To improve consistency across studies, infectivity estimates reported as rates were converted into per-act transmission probabilities56. Heterogeneity across study estimates was explored using the Q-statistic, sub-group and sensitivity analyses and meta-regression techniques52-54. Random-effects meta-regression models were fitted on ln-transformed study estimates using the procedure “proc Mixed” in SAS 9·13. Pooled estimates were exponentiated to obtain estimates on the original scale. Forest plots were produced in R 2.7.057.

Analysis plan

First, we conducted a principal meta-analysis using the crude gender-specific estimates from each publication. Where multiple publications reported estimates based on the same study population, the estimate from the largest or most recent sample was included. We then conducted sensitivity analyses by calculating pooled estimates for different sub-groups of studies (e.g. for females only, with and without CS exposure). We also used univariate and multivariate meta-regression techniques to explore potential sources of heterogeneity across estimates using the following covariates: study design, setting, year of publication, gender, exposure, condom, STI, contamination and ANC HIV prevalence. Finally, we conducted a series of secondary analyses using transmission estimates stratified by risk factors.

Covariates were defined using available information from each study. The covariate setting was used as a marker of unmeasured risk-factors (e.g. viral subtype, co-infection)49. The covariate “Exposure” differentiated between studies conducted among partners following commercial sex(CS) work, as clients or FSWs, or among partners of index cases infected following blood transfusion, or exposed to various sources(including intravenous drug use(IDU), or infected heterosexually. “Contamination” was defined to reflect the likelihood of exposure to HIV via sources (sexual or blood) other than sex with the main index partner. “Condom” characterised studies where its use was rare or somewhat controlled for. “STI” was defined to capture the level of ulcerative STI reported in each study. HIV prevalence from antenatal clinics(ANC) at the time and study location reported from independent sources(e.g. www.who.int/globalatlas), was used as a marker of potential unmeasured parenteral or extramarital exposure, assuming that the risk would increase with HIV prevalence. Further details are provided in Webonly Methods.

RESULTS

Search results

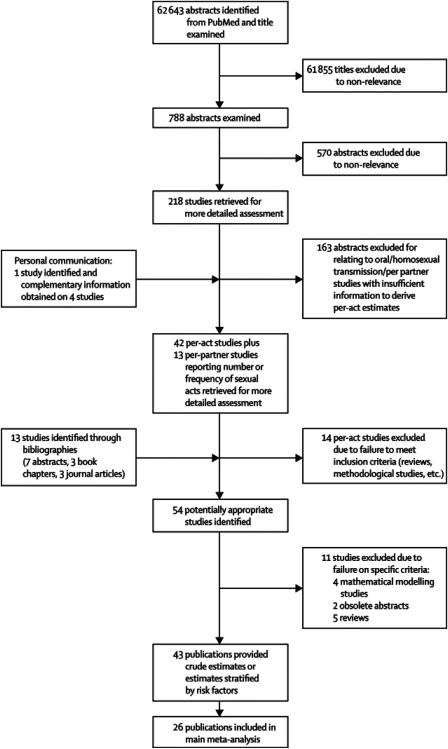

Titles of 62,643 articles from the search were examined. Abstracts of 788 articles were read and 218 papers retrieved for more detailed examination. Most studies were excluded because they were risk factor analyses, reported non-sexual or homosexual transmission, per partner estimates, or did not provide enough information to derive an estimate. Forty-two studies reporting at least one per-act heterosexual HIV-1 transmission estimate and thirteen studies reporting sufficient information to derive one were identified from the PubMed search and in one case by personal communication. Fourteen publications, mainly reviews or methodological studies, were rejected. Thirteen additional publications were identified by perusing the bibliographies of relevant articles. Eleven publications were rejected based on our pre-defined criteria. Forty-three publications reporting crude per-act estimates and/or estimates stratified by risk factors were found14-21,56,58-60,62-70,72-73,75-89,91-94, based on 25 study populations6,24-28,30,58-59,61,64,68-71,74,77-79,81-82,86,90,93-94(Figure 1, Webonly table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart summarising results of the search on heterosexual per-act HIV-1 transmission probabilities. The 11 publications rejected on specific criteria consisted in four mathematical modelling studies22,23,47,95, two obsolete abstracts,96-97 and five reviews10,42,98-100. The 43 publications included 26 publications included in the principle meta-analysis and seven publications only included in the sub-analyses by risk factor17,20,46,76,79,89,92. The remaining publications were duplicates and not included in any analysis but are shown in Webonly table 1 for completion.

Data extraction and study characteristics

Many publications reported results from the same study population (e.g. five publications14,16,83-85 were based on the US-CDC study25) and estimates from the most recent or largest sample were included. Roth and Allen reported on two samples of the same study population that we assumed independent59,60.

Essentially four study designs have been used: retrospective-partner, prospective-discordant-couple, and simple prospective and retrospective studies. In retrospective-partner studies, the infection status of each partner becomes known only at the time of the study. The index case and time of infection are determined based on exposure to a salient risk factor15-16,43,87,92. However, in transfusion studies, the infection time of index cases can be determined more precisely from the date of the transfusion16,25, 27,43,77,81-82. Otherwise, it is estimated by exploring possible dates of infection or by defining a distribution of possible infection times using information from questionnaires and local epidemic curves or CD4+ cell counts15-16,45,83-84,87,92. In prospective-discordant-couple studies, stable (preferably monogamous) HIV serodiscordant couples are followed-up after diagnosis of the index partner19-20,68,70. The sexual history and seroconversion of the partner are assessed prospectively. With simple prospective or retrospective studies, susceptible or infected and susceptible individuals (not necessarily monogamous) are recruited respectively, following sexual contact with potentially infected, high-risk partners. As index cases are not recruited, exposure to HIV is estimated using HIV prevalence in the pool of potential partners and the reported coital frequency21,62-63,72,73.

To avoid duplication, 26 of the 43 publications were included in the principal meta-analysis of crude estimates(Webonly table 1). All but one75 of these 26 publications reported on data collected pre-2001 from developed (Europe, North America) or developing (Africa, Asia, Haiti) country settings. Seven19,59,60,64,68-70 developing country publications were from prospective-discordant couple studies, five21,58,62,72,75 were simple retrospective or prospective studies and one65 was a retrospective-partner study. Developed country estimates were all derived from prospective-discordant-couple18,77,82,86,91,93-94 or retrospective-partner studies15-16,78,80,81,83,91.

Study quality

The reported information on study quality and potential sources of biases varied across studies. For example, in retrospective-partner studies, the identification of index cases and time of infection may be more precise when index cases have been infected through contaminated blood products rather than IDU, bisexual or casual sex. Partners of index cases infected through high-risk behaviour (IDU, sexual promiscuity) may also have higher-risk activities, and therefore higher rates of STIs and/or additional sources of exposure other than sex with the index. Six retrospective-partner studies included index cases who were transfusion recipients16,77-78,81-83; seven included index cases infected through various sources15,18,80,86,91,93-94, including mainly IDU93-94; and eight included index cases probably infected heterosexually19,59-60,64-65,68-70. All five non-partner (i.e. simple prospective or retrospective) studies were conducted in developing country among participants following CS exposure, as FSW clients58,62, FSWs72,75 or men with multiple partners (including sex with FSWs)21, also with high rates of STIs21,58,62.

Many retrospective partner or discordant couple studies attempted to exclude partners with additional sources of HIV exposure other than sex with the index partner using various exclusion criteria15, 27,30-31,78,90,93,94. For example, Marincovich94 excluded partners who reported parenteral exposure, blood transfusion, tattooing and multiple partners, whereas Pedraza93 excluded IDU and promiscuous participants. Infrequent exposure of partners to blood through injections from traditional healers or multiple sexual partners was reported by a few participants in studies by Allen59 and Roth60. Based on reported information, we judged that contamination was possible in ten publications due to occasional reports of extramarital sex15,21,59,60,62,80,83,86 and/or potential exposure to blood58,60,62,72. Due to the high-risk associated with CS exposure, it was generally assumed to be the source of infection, which may not always be the case58,71. “Contamination” was considered unlikely for Wawer20 and Fideli70 since HIV transmissions within couples were matched by molecular linkage. Failure to control for condom use may lead to over-estimation of unprotected sex acts and underestimation of infectivity. Only three publications did not report any attempt to control for condom use or did not provide sufficient information58,62,80(Webonly table 1).

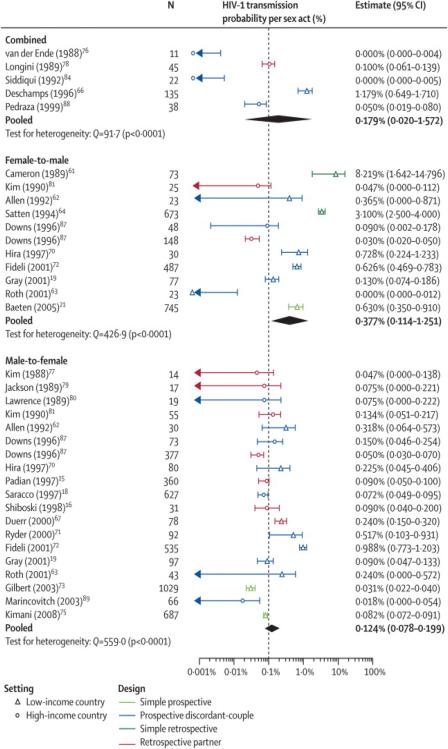

Principal meta-analysis

The meta-analysis included 35 crude gender-specific (M-to-F, F-to-M, C) transmission risk estimates(Webonly table 1). One publication reported independent estimates from both the prospective-discordant and retrospective partner study components, which were both included91. Per-act estimates ranged from 0·00077,86,94 to 0·08258 and displayed considerable heterogeneity (Q=1591,p-value<0·0001)(Table 1, Figure 2). The highest and less precise estimates were mostly from developing countries. The heterogeneity across estimates remained significant even after stratification by gender(Table 1). With further stratification by setting (developed versus developing countries), the heterogeneity across gender-specific study estimates was no longer significant for developed countries only. The pooled C, F-to-M and M-to-F developed country estimates were 0·0008(95%CI 0·0004-0·0016), 0·0004(0·0001-0·0014) and 0·0008(0·0006-0·0011) respectively. In contrast, the pooled F-to-M and M-to-F estimates for developing countries were 0·0087(0·0028-0·0270) and 0·0019 (0·0009-0·0043), respectively. The pooled M-to-F estimate with CS exposure only was much lower than the F-to-M estimates, reflecting the relatively lower Senegalese72 and recent Kenyan estimates75(Webonly table 1). Interestingly, after excluding estimates following CS exposure, which were the only ones from simple prospective and retrospective studies and were exclusively from developing countries, the pooled M-to-F estimates increased, whereas the F-to-M estimates decreased(Table 1). The heterogeneity between developing country estimates remained.

Table 1.

Pooled estimates for subsets of crude study estimates stratified by setting, gender and lack of commercial sex exposure

| Subset of studies | Heterogeneity statistic, Qa |

p-value | prandom | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N=35) | 1590·5 | <0·0001 | 0·0018 | (0·0011-0·0030) |

| Combined (N=5) | 91·4 | <0·0001 | 0·0018 | (0·0002-0·0157) |

| F-to-M (N=11) | 426·9 | <0·0001 | 0·0038 | (0·0011-0·0125) |

| M-to-F (N=19) | 559·0 | <0·0001 | 0·0012 | (0·0008-0·0020) |

| F-to-M without CS exposure b (N=8) | 147·5 | <0·0001 | 0·0016 | (0·0006-0·0048) |

| M-to-F without CS exposure b (N=17) | 356·9 | <0·0001 | 0·0014 | (0·0009-0·0023) |

| F-to-M with CS expsure only c(N=3) | 48·1 | <0·0001 | 0·0244 | (0·0069-0·0866) |

| M-to-F with CS exposure only c(N=2) | 36·3 | <0·0001 | 0·0005 | (0·0002-0·0013) |

| C developed country (N=4) | 3·7 | 0·30 | 0·0008 | (0·0004-0·0016) |

| C developing country (N=1)* | -- | -- | 0·0118 | -- |

| F-to-M developed country (N=3) | 3·9 | 0·1411 | 0·0004 | (0·0001-0·0014) |

| F-to-M developing country (N=8) | 218·4 | <0·0001 | 0·0087 | (0·0028-0·0270) |

| M-to-F developed country (N=10) | 14·8 | 0·0976 | 0·0008 | (0·0006-0·0011) |

| M-to-F developing country (N=9) | 519·5 | <0·0001 | 0·0019 | (0·0009-0·0043) |

| F-to-M developing without CS exposure b (N=5) | 40·9 | <0·0001 | 0·0038 | (0·0013-0·0110) |

| M-to-F developing country without CS exposure b(N=7) | 109·2 | <0·0001 | 0·0030 | (0·0014-0·0063) |

On the ln scale;

Removed to asses their influence:

estimates CS exposure were all from developing countries and the only ones from non-partner studies;

CI=Confidence interval; M-to-F: male-to-female; F-to-M: female-to-male; C: combining gender; CS: commercial sex; -- not applicable; N= Number of study estimates;

reference 64·

Figure 2.

Forest plots of crude per-act study estimates in the absence of commercial sex exposure for: a) Combined M-to-F and F-to-M estimates; b) F-to-M; and c) M-to-F HIV transmission. The point estimate, sample size (N) and 95%CI for each study are represented. The indice ‘d’ indicates that the 95%CI were derived from available data. The indice “i” indicates that the estimate and CI were derived from information provided in main study; the indice “r” indicates that the original rate estimates and CI were converted into probabilities. For reference, a vertical dotted line is shown at 0·001 because this has previously been a commonly cited value for HIV-1 per-act transmission probability49. Light and dark blue lines show estimates from simple prospective and prospective-discordant couple studies, respectively. Green and red lines show estimates from simple retrospective and retrospective-partner studies, respectively. Triangles identify developing country estimates. Circles identify developed country estimates. Note that only the lower bound of the 95%CI of Cameron et al58 and Satten et al62 estimates appear on the F-to-M transmission forest plot because they are too large. “L” and “R” denote the prospective-discordant-couple and retrospective-partner-study components of Downs et al91, respectively.

In univariate meta-regression analyses, a statistically significant fraction of the variability across all 35 study estimates could be explained by either exposure, setting, STI level, condom, design, or ANC prevalence(Table 2). Greater infectivity was associated with CS exposure, developing country setting, studies that did not control for condom use, non-partner studies, and higher STI or higher ANC HIV prevalence. The covariates condom and STI (borderline) were no longer significant after excluding estimates with CS exposure(Table 2). Among all developing country estimates, only gender, condom and year of publication (negative association) were significantly associated with infectivity; no association were found after removing the estimates with CS exposure (details not shown).

Table 2.

Univariate meta-regression analyses for different subset of crude study estimates

| Covariate | Developed and Developing country estimates | Developing country study estimates only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All N=35 |

Exclude CS exposure estimates N=30 |

All N=17 |

Exclude CS exposure estimates N=12 |

|||

| Pooled #

estimate (95%CI) |

Variance explained a (p-value) |

Variance explained a (p-value) |

Pooled #

estimate (95%CI) |

Variance explained a (p-value) |

Variance explained a (p-value) |

|

| Gender | 15·4% | 0·6% | 34·3% | 23·2% | ||

| Combined | 0·0018 (0·0004-0·0073) | (0·07) | (0·89) | 0·0118 (0·0000-0·0999)! | (0·02) | (0·20) |

| F-to-M | 0·0039 (0·0018-0·0085) | 0·0087 (0·0038-0·0198) | ||||

| M-to-F | 0·0012 (0·0007-0·0022) | 0·0019 (0·0009-0·0040) | ||||

| Design | 21·6% | 24·9% | 1·6% | 3·6% | ||

| P-DC | 0·0022 (0·0012-0·0039) | (0·02) | (0·0074) | 0·0038 (0·0017-0·0084) | (0·85) | (0·56) |

| R-PS | 0·0008 (0·0004-0·0017) | 0·0024 (0·0002-0·0314)* | ||||

| Non-partner | 0·0050 (0·0018-0·0141) | 0·0050 (0·0016-0·0160) | ||||

| Exposure | 40·2% | 63·1% | 0·9% | |||

| Commercial sex | 0·0049 (0·0020-0·0122) | (0·0001) | (<0·0001) | 0·0050 (0·0016-0·0160) | (0·65) | (--) |

| TR | 0·0008 (0·0003-0·0021) | -- | ||||

| Various | 0·0007 (0·0003-0·0013) | -- | ||||

| Hetero | 0·0037 (0·0020-0·0068) c | 0·0036 (0·0017-0·0078) | ||||

| Setting | 39·8% | 62·6% | 0% | |||

| Developed | 0·0007 (0·0004-0·0012) | (<0·0001) | (<0·0001) | -- | (--) | (--) |

| Developing | 0·0040 (0·0024-0·0067) | 0·0040 (0·0021-0·0076) | ||||

| Condom | 23·5% | 1·0% | 46·7% | |||

| Not controlled | 0·0130 (0·0034-0·0498) | (0·0025) | (0·67) | 0·0487 (0·0122-0·1943) | (0·0002) | (--) |

| Controlled | 0·0015 (0·0010-0·0023) | 0·0028 (0·0017-0·0047) | ||||

| STI | 30·2% | 28·5% | 16·7% | 5·2% | ||

| L1 | 0·0008 (0·0003-0·0021) | (0·01) | (0·06) | 0·0052 (0·0004-0·0615) | (0·37) | (0·89) |

| L2 | 0·0010 (0·0003-0·0027) | -- | ||||

| L3 | 0·0041 (0·0008-0·0204) | 0·0041 (0·0007-0·0232) | ||||

| L4 | 0·0042 (0·0022-0·0082) | 0·0059 (0·0027-0·0131) | ||||

| Unknown | 0·0011 (0·0005-0·0026) | 0·0017 (0·0006-0·0053) | ||||

| Contamination | 9·1% | 6·9% | 8·8% | 10·2% | ||

| Unlikely | 0·0011 (0·0005-0·0023) | (0·17) | (0·35) | 0·0053 (0·0013-0·0221) | (0·47) | (0·57) |

| Possible | 0·0033 (0·0014-0·0077) | 0·0061 (0·0021-0·0174) | ||||

| No information | 0·0019 (0·0009-0·0043) | 0·0027 (0·0011-0·0066) | ||||

| ANC HIV prevalencei, u1 | 1·06 (1·02-1·11) | 19·6% | 53·9% | 0·99 (0·94-0·1·07) | 0·0% | 10·9% |

| (0·0063) | (<0·0001) | (0·99) | (0·33) | |||

| Year of Publicationi, u2, y |

0·88 (0·53-1·46) | 1·2% | 6·4% | 0·43 (0·26-0·70) | 41·9% | 4·3% |

| (0·62) | (0·23) | (0·0009) | (0·50) | |||

| Variance across study estimates in absence of any covariate a |

1·73 | 0·97 | 1·71 | 0·57 | ||

Fraction of the variability across study estimates explained by each covariate on the ln scale;

Estimateswith CS exposure were all from developing countries and the only estimates from non-partner studies;

For categorical variables this corresponds to infectivity estimates;

For continuous variables this corresponds to a linear change in the logarithm of the infectivity estimate of 0.058 per

1% prevalence;

normalised years;

Infectivity estimates are higher because this category includes only developing country study estimates.

CS=commercial sex; ANC=Antenatal clinic data; M-to-F=male-to-female; N= number of study estimates; F-to-M= Female-to-male; STI=sexually transmitted infections; IDU= intravenous drug use; --Not applicable because no study had that characteristic. Covariates: Design: P-DC=prospective-discordant-couple; R-PS=retrospective partner study; Non-partner=simple prospective (C-L) or simple retrospective (X-R); TR= transfusion recipient; “Exposure”: partners exposed to CS, index cases infected by transfusion (TR), through IDU, heterosexually, or transfusion (Various) or mainly heterosexually(Hetero). STI is at baseline or during follow-up (for C-L and P-DC studies) or history (for X-R and R-PS studies) among partners or index cases: L1≤ 1%, 1%< L2≤ 5%, 5%<L3≤ 10%; L4: >10% for ulcerative STI or L4: >25% any STI history;

year of start of the study was also explored but not significant in any of the subsets(results not shown);

reference 65 only;

reference 64 only.

The multivariate meta-regression analyses aimed to explain the heterogeneity across the 30 developed and developing country estimates without CS exposure, which were all based on discordant-couple or retrospective-partner studies. When controlling for gender(p-value>0.23) and study design(p-value>0.49), only setting, ANC prevalence and exposure were independently associated with infectivity(p-value<0·0001) and explained 62-68% of the variability(details not shown). In models including design(p-value>0.10), gender(p-value<0.015), setting(p-value<0.0001), the interaction term between setting and gender(p-value<0.036), only contamination(p-value=0.009) or ANC prevalence(p-value=0.006) remained statistically significant and together explained 82-85% of the variance(details not shown). Lower infectivity estimates were associated with the contamination category “no information” compared to the categories “possible” or “unlikely”, which were not statistically different(p-value =0·45). Thus, our final model excluded design and included ANC prevalence(Webonly table 2). Combined and M-to-F developed country estimates, adjusted for prevalence, were ~1·6(0·6-4·3)- and ~1·8-(0·8-3·9)-fold larger than F-to-M estimate, respectively, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. F-to-M and M-to-F developing country estimates were of similar magnitude(RR 1·0,p-value=0·93). M-to-F and F-to-M developing country estimates were 1·8(0·9-3·9)-fold and 3·3(1·1-9·7)-fold larger than developed country estimates, respectively. The natural logarithm of the infectivity estimate was increased by an average 0·046-fold for each 1% increase in ANC HIV prevalence(Webonly table 2).

Secondary analysis by risk factors

Only two publications89,92 reported M-to-F estimates for receptive anal intercourse (RAI)(pooled=0·017, CI:0·003-0·089,Q=4·2) and five16,18,68,81,92 explicitly reported M-to-F estimates for vaginal sex only (pooled=0·0008,CI:0·0005-0·0009,Q=9·5)(Additional information available from the authors)).

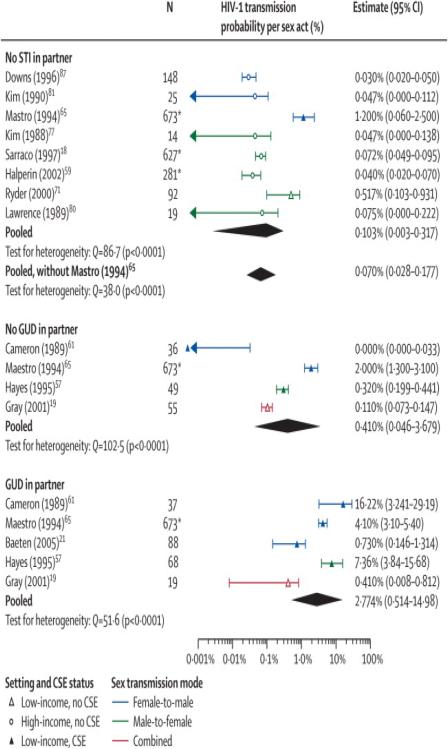

Six publications reported developing country estimates stratified by GUD status of the HIV-1 susceptible partners19,21,58,63,67,76(reflecting increased HIV susceptibility due to GUD or by GUD status of the index case19 (reflecting increased HIV infectivity). Gray reported a lower infectivity in presence of GUD than the other study estimates in presence of CS exposure21,58,63,76. An additional eight study estimates in absence of STI were also included18,63,69,78,82-83,89,91. Due to the small number of estimates, simple explanatory meta-regression analyses were undertaken. We classified the estimates into three categories: study participants without STI; without GU but potentially other STI; and with GU and potentially other STI as well(Table 3). The covariate GU status alone explained 57% of the variability across study estimates. The meta-regression model with the covariates CS exposure and GU status explained a larger fraction of the variability(81%) than GU status with either covariates setting(77%) or gender (70%)(details not shown). Estimates in the presence of GU were 5-fold larger than estimates in absence of STI, whereas CS exposure was associated with an 11-fold increase in infectivity compared to estimates without CS exposure(Table 4).

Table 3.

Per-act and pooled estimates for the sub-analysis of study estimates stratified by genital ulcer disease status

| Reference | Setting | Exposure | Gender | N2 | Qa | Estimate (95%CI) | Included | ||||

| No sexually transmitted infection among the HIV-1 susceptible partner | |||||||||||

| Downs (1996)91 | Developed | Non CS | F-to-M | 148 | 0·0003 (0·0002-0·0005) | √ | |||||

| Kim (1990)83 | Developed | Non CS | F-to-M | 25 | 0·0005 (0·0000-0·0011)d | √ | |||||

| Mastro (1994)63 | Developing | CS | F-to-M | 673 t | 0·0120 (0·0006-0·0250) | √ | |||||

| Kim (1988)78 | Developed | Non CS | M-to-F | 14 | 0·0005 (0·0000-0·0014)i | √ | |||||

| Saracco (1997)18 | Developed | Non CS | M-to-F | 627t | 0·0007 0·0005-0·0010)r | √ | |||||

| Halperin (2002)89 | Developed | Non CS | M-to-F | 281t | 0·0004 (0·0002-0·0007)adj | √ | |||||

| Ryder (2000)69 | Developing | Non CS | M-to-F | 92 | 0·0052 (0·0010-0·0093)i | √ | |||||

| Lawrence (1989)82 | Developed | Non CS | M-to-F | 19 | 0·0008 (0·0000-0·0022)i | √ | |||||

| Pooled | All | 8 | 86·7 | 0·0010 (0·0003-0·0011) | |||||||

| Pooled- without Mastro | 7 | 38·0 | 0·0007 (0·0003-0·0017) | ||||||||

| No genital ulcer diseases among the HIV-1 susceptible partner1 | |||||||||||

| Cameron (1989)58 | Developing | CS | F-to-M | 36 | 0·0000 (0·0000-0·0003)d | √ | |||||

| Mastro (1994)63 | Developing | CS | F-to-M | 673t | 0·0200 (0·0130-0·0310) | √ | |||||

| Hayes (1995)76 | Developing | CS | M-to-F | 49 | 0·0032 (0·0020-0·0044)d | √ | |||||

| Gray (2001)19 | Developing | Non-CS | C | 55 | 0·0011 (0·0007-0·0015)d | √ | |||||

| Corey (2004)67 | Developing | Non-CS | C | nr | 0·0004 (nr)ne | ||||||

| C | nr | 0·0019 (nr)po | |||||||||

| Pooled | All | 4 | 102·5 | 0·0041 (0·0005-0·0368) | |||||||

| Presence of genital ulcer diseases in the HIV-1 susceptible partner 1 | |||||||||||

| Cameron (1989)58 | Developing | CS | F-to-M | 37 | 0·1622 (0·0324-0·2919)d | √ | |||||

| Mastro (1994)63 | Developing | CS | F-to-M | 673t | 0·0410 (0·0310-0·0540) | √ | |||||

| Baeten (2005)21 | Developing | CS | F-to-M | 88 | 0·0073 (0·0015-0·0131)d | √ | |||||

| Hayes (1995)76 | Developing | CS | M-to-F | 68 | 0·0736 (0·0384-0·1568)d,e | √ | |||||

| 0·0051 (0·0037-0·0065)i, f | |||||||||||

| Gray (2001)19 | Developing | Non-CS | C | 19 | 0·0041 (0·0001-0·0081)d | √ | |||||

| Corey (2004)67 | Developing | Non-CS | C | nr | 0·0031 (nr)po | ||||||

| Pooled | All | 5 | 51·6 | 0·0277 (0·0051-0·1498) | |||||||

Heterogeneity statistics calculated on the ln scale;

Only one publication

reported GU status for the index cases rather than for HIV susceptible; nr: excluded because 95%CI could not be derived from available information;

estimate adjusted for anal intercourse, condom use, STI history;

N= number of subjects for individual studies or number of estimates included in pooled estimate; C: combined male-to-female and female-to-male transmission; FUP: During follow-up period;

total sample size;

during episodes of GU;

during follow-up period which includes period with and without GU episodes;

The 95%CI was derived;

Estimate and CI derived from information provided in main study;

original rate and CI estimates converted into probabilities;

HSV-2 positive;

HSV-2 negative; All: include study estimates from any gender.

Table 4.

Multivariate meta-regression models for the sub-analysis by GU status and disease stage

| GU status (N=17) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | RR | 95%CI | p-value |

| GU status | 0·0162 | ||

| No STI | 1 | -- | |

| No GU | 1·11 | (0·30, 4·14) | |

| GU | 5·29 | (1·43,19·58) | |

| CS exposure | <0·0001 | ||

| No | 1 | -- | |

| Yes | 11·08 | 3·47 (3·47, 35·35) | |

| Total fraction of the total variance explained = 81% a | |||

| Disease stage (N=14) | |||

| Covariate | RR | 95%CI | p-value |

| Disease stage | <0·0001 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 1 | -- | |

| Early | 9·17 | (4·47, 18·81) | |

| Late | 7·27 | (4·45, 11·88) | |

| Setting | 0·347 | ||

| Developing | 1 | -- | |

| Developed | 0·79 | (0·49, 1·29) | |

| Fraction of the total variance explained= 96%a | |||

CI= Confidence interval; N= Number of estimates;

On the ln scale

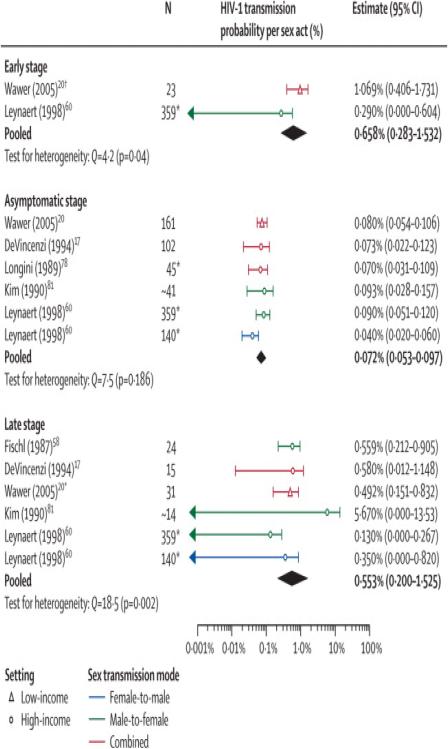

Seven publications, two on the same developing country population20,56, reported estimates by disease stage of index partners from partner studies(Table 5)17,20,56,79-80,83,92. Estimates ranged from 0·0010 to 0·0107, 0·0004 to 0·0010 and 0·0013 to 0·0567 for the early, asymptomatic and late stage, respectively. Wawer20 reported many estimates from different sub-samples of discordant couples where index cases had been infected for different lengths of time. We used the estimate from couples where index cases had seroconverted for less than five months(pi=0·0107), which was larger than from couples 6-15 months and 16-35 months after the index cases had seroconverted(Table 5). The estimate from all couples with prevalent index cases(pi=0·0008) was used for the asymptomatic stage. The late stage estimate used corresponded to 6-15 months before death of index cases (pi=0·0049). Disease stage alone explained 95% of the variability across estimates. After adjusting for disease stages, the addition of the covariate “Setting” was not significant(Table 4). The impact of gender could not be explored due to lack of data. The risk in the early(RR=9·2,CI:4·5-18·8) and late stage (RR=7·3,CI:4·5-11·9) adjusted for setting were significantly larger than for the asymptomatic phase(Table 4).

Table 5.

Per-act and pooled estimates for the sub-analysis of study estimates stratified by disease stage

| Reference | Setting | Gender | N2 | Qa | Estimate (95%CI) | Included | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early stage | |||||||

| Wawer (2005)20 | Developing | C | 23 | 0·0107 (0·0041-0·0173) r | < 5months s | √ | |

| C | 13 | 0·0017 (0·0002-0·0040) r | 6-15 monthss | ||||

| C | 7 | 0·0010 (0·0000-0·0031) r | 6-35 monthss | ||||

| C | 43m | 0·0043 (0·0020-0·0067) r | All incident index | ||||

| Pinkerton (2008)56 | Developing | C | 23 | 0·0107 (0·0041-0·0173)d | < 5 months s | ||

| 13 | 0·0017 (0·0002-0·0040)d | 6-15 monthss | |||||

| 7 | 0·0010 (0·0000-0·003 1) d | 16-35 monthss | |||||

| Leynaert (1998)92 | Developed | M-to-F | 359t | 0·0029 (0·0000-0·0060)d | √ | ||

|

| |||||||

| Pooled | All | 2 | 4-2 | 0·0066 (0·0028-0·0153) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Asymptomatic stage | |||||||

| Wawer(2005)20 | Developing | C | 161 | 0·0009 (0·0004-0·0014) r | 0·10 months FUP | ||

| C | 129 | 0·0007 (0·0002-0·001 1) r | 11-20 months FUP | ||||

| C | 92 | 0·0010 (0·0004-0·0016) r | 21-30 months FUP | ||||

| C | 45 | 0·0004 (0·0000-0·0008) r | 31-40 months FUP | ||||

| C | 161 | 0·0008 (0·0006-0·001 1) r | All prevalent index | √ | |||

| DeVincenzi (1994)17 | Developed | C | 102 | 0·0007 (0·0002-0·0012) r | √ | ||

| Longini (1989)80 | Developed | C | 45 t | 0·0007 (0·0003-0·001 1)d | √ | ||

| Kim (1990)83 | Developed | M-to-F | ~41 | 0·0009 (0·0003-0·0016)d | √ | ||

| Leynaert (1998)92 | Developed | M-to-F | 359 t | 0·0009 (0·0005-0·0013) | √ | ||

| F-to-M | 140 t | 0·0004 (0·0002-0·0006) | √ | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Pooled | All | 6 | 7-5 | 0-0007 (0·0005-0·0010) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Late stage | |||||||

| Longini (1989)80 | Developed | C | 45t | 0·0057 (0·0026-0·0088) | |||

| DeVincenzi (1994)17 | C | 15 | 0·0058 (0·0001-0·0115) r | √ | |||

| Wawer (2005)20 | Developed | C | 22 | 0·0015 (0·0000-0·0035) r | 26-35 months before death | ||

| C | 35 | 0·0037 (0·0013-0·0062) r | 16-25 months before death | ||||

| C | 31 | 0·0049 (0·0015-0·0083) r | 6-15 months before death | √ | |||

| C | 51 | 0·0039 (0·0021-0·0056) r | All late index | ||||

| Kim (1990)83 | Developed | M-to-F | ~14 | 0·0567 (0·0000-0·1353)d | √ | ||

| Fischl (1987)79 | Developed | M-to-F | 24 | 0·0056 (0·0021-0·0091)i | √ | ||

| F-to-M | 8 | 0·0051 (0·0000-0·0109)i | |||||

| Leynaert (1998)92 | Developed | M-to-F | 359 t | 0·0013 (0·0000-0·0027) | √ | ||

| F-to-M | 140 t | 0·0035 (0·0000-0·0082) | √ | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Pooled | All | 6 | 18-5 | 0-0055 (0·0020-0·0153) | |||

Heterogeneity statistics calculated on the ln scale;

since seroconversion of index case;

used both the retrospective and prospective component of Fischl et al’s data79;

The 95%CI derived;

Estimate and CI derived from information provided in main study;

original rate estimates and CI converted into probabilities;

C: combined male-to-female and female-to-male transmission; FUP: follow-up period;

total sample size;

Different from Table 1 in Wawer et al20 because there is a mistake in the original paper (denominator reported as 23 when actually 43);

~Approximation; All: include study estimates from any gender.

Only two publications reported empirical estimates stratified by level of either semen or serum viral load on the same study population19,20(additional information available from the authors). Partners of index cases who had a median serum viral load ~30,000 HIV RNA copies/ml(range<400-3,100,000 copies/ml <5 months after seroconversion) had a higher infectivity (pi=0·0107) than those with a median serum viral load ~2600 copies/ml by 15 months20, and even higher than Gray’s estimate(pi=0·0023) when viral load exceeded 38,500 copies/ml19. Wawer’s20 estimate from couples where prevalent index cases were followed-up for 0-10 months was higher(pi=0·0009,~10,300 copies/ml), albeit not significantly, than when followed-up for more than 30 months(pi=0·0004,~15,000 copies/ml). Gray’s19 combined estimates at high(>38,500 serum copies /ml); medium(~1700-12,499 or 12,500-38,499 copies/ml), and low(<1700 copies/ml) viral loads were pi=0·0023, pi=0·0013 or pi=0·0014, and pi=0·0001, respectively. Pilcher22 and Chakraborty23 also reported higher infectivity at higher viral load but their estimates were not directly comparable because they were derived from theoretical studies based on measurement of HIV-1 viral load by volume of semen.

Only two publications reported F-to-M estimates by circumcision status21,58(additional information available from the authors). Baeten’s21 crude F-to-M transmission estimate among uncircumcised men was approximately 2·6 times that among circumcised men(pi=0·013,CI:0·005-0·020 vs pi=0·005,CI:0·003-0·007) and 4·5 times larger in non-circumcised than circumcised men in the presence of GUD (pi=0·018,CI:0·000-0·037 vs pi= 0·004,CI:0·000-0·009)21. In Cameron’s study58, crude estimates were higher among uncircucmsied(pi=0·185,CI:0·023-0·348) than circumcised(pi=0·022,CI:0·000-0·064) men. Amongst those with GU, estimates were six-fold higher among uncircumcised(pi= 0·428,CI:0·0126-0·730) than circumcised men(pi=0·067,CI:0·000-0·192). In the absence of GU, no HIV transmission occurred in circumcised or uncircumcised men58.

DISCUSSION

Summary of the results

Our systematic review and meta-analysis of HIV-1 transmission probabilities per heterosexual act comprehensively updates and extends the findings of a recent similar review49. We confirmed the earlier observation of considerable heterogeneity in per-act estimates49, provided gender-specific transmission estimates and identified additional sources of heterogeneity by exploring interactions between covariates. We also reported the influence of key risk factors on infectivity in terms of relative risk, instead of risk difference, which is easier to interpret. Heterogeneity across crude study estimates could be mostly explained by commercial sex exposure as FSWs or clients, setting, gender and the ANC HIV prevalence at the time and study location. Although a previous review only found a weak association between gender and infectivity 49, our results suggested that this may vary by settings. In the subset of estimates without CS exposure, the pooled F-to-M transmission estimate for developed countries, adjusted for HIV prevalence, was about half the M-to-F or Combined estimates(RR~0·5), although the difference failed to reach statistical significance. In contrast, the adjusted developing country F-to-M and M-to-F estimates were very similar(RR~1·0), and the F-to-M developing country estimate(RR~3·3) significantly larger than the F-to-M developed country estimate. The M-to-F or Combined pooled estimates in our sub-analyses in absence of RAI, GU, CS exposure, or for the asymptomatic phase were of similar magnitude(~0·0007) to the M-to-F and Combined pooled estimates from developed countries(~0·0008), which would suggest that they represent the average per-vaginal-sex-act transmission in absence of cofactors, during the asymptomatic phase.

Despite differences in some selection criteria and the strategy adopted for the analysis, we confirmed the findings of previous reviews on the weak influence of study quality49 and the importance of key risk factors16,39,42,49,67,105 on infectivity. In agreement with studies among homosexuals5,101-103 our pooled estimate by RAI supports that it is a more risky practice than receptive vaginal sex. Two studies reporting per-act estimates by circumcision status21,58 suggested a ~3 to 8-fold increase in HIV infection among uncircumcised males overall or in presence of GUD. This is consistent, yet somewhat higher, with the results of two meta-analyses104-105 and three recent randomised controlled trials of male circumcision106-108. We found that the presence of GU and CS exposure were independently associated with increased infectivity. Our GU cofactor estimate(RR 5·3) was intermediate between previous estimates for high-risk groups (10-50 and 50-300 for M-to-F and F-to-M transmission per act respectively)76 and those from a meta-analysis of observational studies which reported a 2·8-fold(2·0-4·0) and 4·4-fold (2·9-6·6) increase in female and male susceptibility due to GUD109, respectively. Both our RR and estimates from observational studies may be biased due to misclassification, undiagnosed STI, misreporting of symptoms. In addition, the intermittent nature of GU means that it is unlikely to have been present throughout the at-risk period and per-contact cofactor effects may therefore be underestimated44,76. Our cofactor estimate predominantly captured the increased HIV susceptibility due to GU (as only one study19 reported estimates stratified by GU status of index cases). Thus, the increased risk associated with CS exposure may partly reflect increases in HIV infectivity since high-risk index cases (FSW, clients) would likely have also been infected with GU or other STIs. Baeten’s F-to-M study estimate from men with multiple partners (31% monogamous, 57% sex with FSW) was higher than from the sub-sample of men who only reported sex with their wives (pi=0·0068 vs 0·0038, p-value>0·10)21.

Interestingly, the early Kenyan and Thai FSW-to-client estimates58,62 were considerably larger than the Senegalese and the recent Kenyan client-to-FSW estimates72-73,75. Although these estimates are likely imprecise since they were based on simple retrospective or cross-sectional study design, the large difference (>35-fold) could also be due to cofactors. STI rates may have been lower among Senegalese FSWs because of an early governmental public health programme, whereby self-identified FSW regularly attended health clinics providing free STI treatment110-111. In contrast, the client studies were conducted in East Africa (early in the epidemic) and Thailand, where circumcision prevalence is lower than in West Africa112 and at a time when STI and GUD were virtually ubiquitous and when FSW were experiencing an explosive HIV epidemic, and index partners were more likely to be in the primary phase of HIV infection46,61,113. For example, Limpakarnjanarat reported 21% Haemophilus ducreyi, 80% Herpes Simplex Virus-2, and 9% GUD among Thai FSWs63,113. Kimani also suggested that the decline in per-act infectivity observed over calendar time in their study correlated with a decline in STI prevalence among FSWs75.

Previous individual-based studies showed an association between HIV infectivity and viral load or time since infection22,24,28,114-117. Our risk factor analysis also suggested increased infectivity for index cases in the early and late phase of infection compared to the asymptomatic phase. The difference between estimates for the early and late stages was not statistically significant, which may reflect similar infectivity, under-sampling of couples with most recently infected and highly infectious index cases, imprecise definition of the duration of the early phase or a lack of statistical power. A recent re-analysis of Wawer’s data suggested that primary infection and late-stage infection were 26 and 7 times higher than asymptomatic infection and that the high infectiousness during primary infection lasted ~ 3 months118.

Study limitations

We initially did not impose any inclusion criteria based on study design since each design has intrinsic biases, even prospective discordant-partner studies, which are seen as the most appropriate design to estimate transmission probabilities. Although discordant partner studies are likely to reduce recall biases regarding type and frequency of unprotected contacts and HIV cofactors, the reporting of sensitive behaviour is still subject to social desirability biases. Frailty selection, whereby the most vulnerable couples of “high and fast transmitters” rapidly become seroconcordant16,45, may also result in over-sampling of less susceptible partners and/or less infective index cases who remain uninfected longer and become more likely to be enrolled in discordant couples studies. Frailty selection would result in under-estimation of infectivity. Shiboski also suggested that heterogeneity in infectivity was not well reflected in the US-CDC25, CDC-HATS27 retrospective-partner studies because the duration of many relationships was too short compared to the time since infection of index cases16,45.

Results from our risk factor analyses are mainly explanatory. The estimates of the magnitude of the cofactor effects may not be very precise due to the small number of studies and covariates that could be explored, the heterogeneity across study estimates, differences in risk factor exposure definitions across studies and because study estimates were based on sub-groups of the study sample. Publication biases may also be present since estimates by risk factor may not be reported from studies that did not find a significant association.

The independent positive association between infectivity and setting or ANC HIV prevalence for studies without CS exposure is difficult to interpret but is unlikely to be due to study design or analytic methods. As reported previously49, study design was only weakly associated with infectivity. In addition, we converted estimates reported as rates into probabilities which improved comparability across studies. Larger transmission probabilities may lead to higher HIV prevalence in the general population, as estimated in developing countries. Alternatively, higher HIV prevalence may increase the likelihood of “contamination” due to exposure to additional sources of infection other than sex with the main index partner and bias estimates upward. Developing country estimates displayed greater heterogeneity than developed country estimates. Gender, date of publication, or the covariate condom (confounded with CS exposure) only explained a significant fraction of the variation across developing country estimates (when estimates with CS were included). This is not entirely surprising given the limited number of studies and that the STI, contamination, and condom use covariates could only be defined broadly, leading to potential misclassification. Thus, the heterogeneity may reflect un-captured “contamination” or variation in the prevalence of key risk factors. For example, the larger F-to-M than M-to-F estimates in three19,59,68 discordant couples studies in developing countries may indicate contamination since men often report more extramarital sex than females prior or during the study period28,59,60,64,69,119. Interestingly, in Fideli’s study70, where transmission events within couples could be epidemiologically linked, F-to-M transmission was lower than M-to-F transmission. However, Fideli’s estimates were larger than Wawer’s estimates, where infections within couples were also confirmed by molecular linkage, which reduces the risk of misclassification, but does not reduce biases due to misreporting of number of unprotected sex acts or unmeasured risk factors120. As many studies in developing countries were carried out within the context of interventions involving an important counselling component19-20,59,68-69, condom use may have been over-reported by study participants, leading to higher infectivity estimates. Nevertheless, reported condom use remained low or even decreased in some studies19,68. Other studies tried to minimise misreporting biases on sexual behaviour by checking for concordance between both members in the couple or using sexual diaries19,64. In Roth’s study, because men reported more protected sex acts then women, we used the sexual activity reported females to minimise biases in our estimates60. Conflicting evidence remains regarding unmeasured exposure to contaminated equipment or blood transfusion that may have increased developing country estimates7,8,10-12,121-123. An early cohort study of registered Senegalese FSWs reported high prevalence of transfusion, scarification, excision or tattoos, yet HIV prevalence in West Africa and the reported transmission probability estimate for this population are low71-73,110-111.

Potential role of risk factors

We cannot exclude the possibility that our high and heterogeneous developing country estimates are due to unmeasured heterogeneity in the prevalence of risk factors. To assert that a 3·5-fold difference in F-to-M pooled estimates between developing and developed countries is solely due to contamination would imply that ~70% of infections are acquired outside the main relationship. While this seems inconsistent with the relatively low proportion of unlinked infections reported in at least two studies19,70,119, this remains a subject of debate121-124. Powers et al reported a weak association between region and infectivity, which they assumed was a proxy for viral subtypes49. However, they also found greater heterogeneity across estimates from Africa. The reason for the differences by setting is likely to be multi-factorial. Lack of male circumcision may be more important in developing countries than in Europe, where circumcision is rare, due to interacting cofactors such as ulcerative STI39,125-128. It is possible that between-settings differences may never be completely understood because risk factors such as STI prevalences may have changed since the beginning of the epidemic75,129. Greater heterogeneity in risk factors or median viral loads in developing countries may exacerbate frailty selection over time. Median plasma viral load as high as 6·1 log10 copies/ml has been observed among acutely infected men in Malawi and presence of STI was the stronger risk factor associated with high viral load42,128. Thus, intermittent interaction between risk factors may result in very high peaks of infectivity during the incubation period and results in frailty selection at the population level42,128. This may also explain why estimates tended to be lower (albeit not significantly) for couples with prevalent index cases with 31-40 months follow-up(pi=0·0004), compared to 0-10 months(pi=0·0009), despite the higher median viral load reported after 30 months20. However, unmeasured reduction in prevalence of risk factors due to longer exposure to the study or other intervention is also possible.

Heterogeneity across estimates may also be due to population-level declines in infectivity over calendar time59-60,75-76 as the fraction of recent seroconverters is expected to decrease in maturing epidemics. Nonoxynol-9 spermicide, which has been associated with increased susceptibility to GU and HIV infection36,130-131, was also reported in at least four early African studies59-60,68,70. However, in Allen’s study59, only 12% of females reported the use of Nonoxynol-9 without condoms, 6% and 19% reported a history of STI in the past year and past two years, respectively, which were comparable to rates reported in the Rakai study19. Most studies were carried out before wide-scale use of antiretroviral therapy and which is therefore unlikely to have influenced results29,32.

Implications of findings

Our results indicated higher transmission probabilities for developing than for developed country studies. The greater heterogeneity of developing country estimates is itself interesting and may suggest poorer study quality, greater heterogeneity in risk factors or greater under-reporting of high-risk behaviour in these studies. More research is needed to better understand these differences, and particularly the low estimates from Rakai19-20. Greater heterogeneity may also be due to differential infectivity of the different viral subtypes, mutation of chemokine-receptor genes, contraception method, genetic, biological and virologic host factors, and interaction with other infectious diseases5,33--41,50,115-118,125,130-132. A better quantification of per-act infectivity is important to improve understanding of the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS worldwide, to predict the future HIV/AIDS pandemic and when designing appropriate prevention strategies. The design of discordant-partner studies could be improved by designing and powering them for carefully planned risk factor analyses, including epidemiological linkage, using data collection methods to reduce social desirability biases, cross validating sexual history in couples and carefully documenting non-sexual potential sources of contamination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (R.F.B. [GR082623MA] and R.G.W. [GR078499MA]), GlaxoSmithKline (R.F.B) and the UK Medical Research Council (R.G.W). B.M. and L.W.: part of this work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy Infectious Diseases of the US National Institutes of Health (5U01AI068615). Michel Alary is a National Researcher of the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec, Canada (grant # 8722). M.C.B: Support for this study was partly provided by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

We thank Elizabeth Baggaley and Dr Kamal Desai for language translations, and Dr Peter Gilbert and Dr Stephen Shiboski for personal communication. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for very useful comments.

RFB was supported during part of the research by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Antenatal clinic

- C

Gender combined HIV-1 transmission probability estimate

- CS

Commercial sex

- FSW

Female sex worker

- F-to-M

Female-to-male HIV-1 transmission probability estimate

- GUD

Genital ulcer disease

- IDU

Intravenous drug use(r)

- M-to-F

Male-to-female HIV-1 transmission probability estimate

- RAI

Receptive anal intercourse

- RR

Relative risk

- STI

Sexually transmitted infections

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

None

References

- 1.Brewer TH, Hasbun J, Ryan CA, et al. Migration, ethnicity and environment: HIV risk factors for women on the sugar cane plantations of the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 1998;12(14):1879–87. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199814000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiscus SA, Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, et al. Perinatal HIV infection and the effect of zidovudine therapy on transmission in rural and urban counties. JAMA. 1996;275(19):1483–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris NS, Thomson SJ, Call R, et al. Zidovudine and perinatal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission: a population-based approach. Pediatrics. 2002;109(4):e60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thaithumyanon P, Thisyakorn U, Limpongsanurak S, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal zidovudine treatment in reduction of perinatal HIV-1 transmission in Bangkok. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001;84(9):1229–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggaley RF, Boily MC, White RG, Alary M. Systematic review of HIV-1 transmission probabilities in absence of antiretroviral therapy. UNAIDS report. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plummer FA, Simonsen JN, Cameron DW, et al. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:233–239. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmid GP, Buve A, Mugyenyi P, et al. Transmission of HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africa and effect of elimination of unsafe injections. Lancet. 2004;363(9407):482–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15497-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buve A, Bishikwabo-Nsarhaza K, Mutangadura G. The spread and effect of HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2002;359(9322):2011–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08823-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyindo M. Complementary factors contributing to the rapid spread of HIV-1 in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. East Afr Med J. 2005;82(1):40–6. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v82i1.9293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deuchert E, Brody S. Plausible and implausible parameters for mathematical modeling of nominal heterosexual HIV transmission. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):237–44. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisselquist D, Potterat JJ, Brody S, Vachon F. Let it be sexual: how health care transmission of AIDS in Africa was ignored. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(3):148–61. doi: 10.1258/095646203762869151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gisselquist D, Potterat JJ, Brody S. Running on empty: sexual co-factors are insufficient to fuel Africa's turbocharged HIV epidemic. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(7):442–52. doi: 10.1258/0956462041211216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garnett GP, Rottingen JA. Measuring the risk of HIV transmission. AIDS. 2001;15(5):641–3. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103300-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EH. Modeling HIV infectivity: must sex acts be counted? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3(1):55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padian NS, Shiboski SC, Glass SO, Vittinghoff E. Heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in northern California: results from a ten-year study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(4):350–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiboski SC, Padian NS. Epidemiologic evidence for time variation in HIV infectivity. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;19:527–535. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199812150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Vincenzi IA. Longitudinal study of human immunodeficiency virus transmission by heterosexual partners. European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:341–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408113310601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saracco A, Veglia F, Lazzarin A. Risk of HIV-1 transmission in heterosexual stable and random couples. The Italian Partner Study. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 1997;11(1-2):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Brookmeyer R, et al. Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2001;357(9263):1149–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(9):1403–9. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baeten JM, Richardson BA, Lavreys L, et al. Female-to-male infectivity of HIV-1 among circumcised and uncircumcised Kenyan men. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(4):546–53. doi: 10.1086/427656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilcher CD, Tien HC, Eron JJ, Jr, et al. for the Quest Study; Duke-UNC-Emory Acute HIV Consortium Brief but efficient: acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(10):1785–92. doi: 10.1086/386333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakraborty H, Sen PK, Helms RW, et al. Viral burden in genital secretions determines male-to-female sexual transmission of HIV-1: a probabilistic empiric model. AIDS. 2001;15(5):621–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103300-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group N Engl J Med. 2000;342(13):921–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterman TA, Stoneburner RL, Allen JR, et al. Risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission from heterosexual adults with transfusion associated infections. JAMA. 1988;259:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padian N, Marquis L, Francis DP, et al. Male-to-female transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. JAMA. 1987;258(6):788–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Brien TR, Busch MP, Donegan E, et al. Heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from transfusion recipients to their sex partners. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7(7):705–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tovanabutra S, Robison V, Wongtrakul J, et al. Male viral load and heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 subtype E in northern Thailand. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29(3):275–83. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200203010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porco TC, Martin JN, Page-Shafer KA, et al. Decline in HIV infectivity following the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2004;18:81–88. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000096872.36052.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV Comparison of female to male and male to female transmission of HIV in 563 stable couples. BMJ. 1992;304:809–813. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6830.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV Risk factors for male to female transmission of HIV. BMJ. 1989;298:411–415. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6671.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson DP, Law MG, Grulich AE, Cooper DA, Kaldor JM. Relation between HIV viral load and infectiousness: a model-based analysis. Lancet. 2008 Jul 26;372(9635):314–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmberg SD, Horsburgh CR, Jr, Ward JW, Jaffe HW. Biologic factors in the sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 1989;160(1):116–25. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buchacz KA, Wilkinson DA, Krowka JF, et al. Genetic and immunological host factors associated with susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1998;12(Suppl A):S87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz BJ, et al. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature. 1996;382(6593):722–5. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Damme L, Ramjee G, Alary M, et al. COL-1492 Study Group Effectiveness of COL-1492, a nonoxynol-9 vaginal gel, on HIV-1 transmission in female sex workers: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9338):971–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hudgens MG, Longini IM, Vanichseni S, et al. Subtype-specific transmission probabilities for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 among injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(2):159–68. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soto-Ramirez LE, Renjifo B, McLane MF, et al. HIV-1 Langerhans' cell tropism associated with heterosexual transmission of HIV. Science. 1996;271:1291–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wasserheit JN. Epidemiological synergy. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19(2):61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laga M, Alary M, Nzila N, et al. Condom promotion, sexually transmitted diseases treatment, and declining incidence of HIV-1 infection in female Zairian sex workers. Lancet. 1994;344(8917):246–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sewankambo N, Gray RH, Wawer MJ, et al. HIV-1 infection associated with abnormal vaginal flora morphology and bacterial vaginosis. Lancet. 1997;350(9077):546–50. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)01063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen MS, Pilcher CD. Amplified HIV transmission and new approaches to HIV prevention. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(9):1391–3. doi: 10.1086/429414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shiboski S, Padian NS. Population- and individual-based approaches to the design and analysis of epidemiologic studies of sexually transmitted disease transmission. J Inf Dis. 1996;174(Suppl 2):S188–200. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_2.s188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boily MC, Anderson RM. Measure Human immunodeficiency virus transmission and the role of other sexually transmitted diseases. Measures of association and study design. Sex Transm Dis. 1996;23(4):312–32. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiboski SC, Jewell NP. Statistical analysis of the time dependence of HIV infectivity based on partner study data. JASA. 1992;87(418):360–372. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mastro TD, de Vincenzi I. Probabilities of sexual HIV-1 transmission. AIDS. 1996;10(Suppl A):S75–82. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.May RM, Anderson RM. Transmission dynamics of HIV infection. Nature. 1987;326(6109):137–42. doi: 10.1038/326137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gisselquist D, Potterat JJ. Heterosexual transmission of HIV in Africa: an empiric estimate. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(3):162–73. doi: 10.1258/095646203762869160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Powers KA, Poole C, Pettifor AE, Cohen MS. Rethinking the heterosexual infectivity of HIV-1: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious Diseases. Sep;8(9):553–63. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70156-7. Epub 2008 Aug 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poulsen AG, Kvinesdal BB, Aaby P, et al. Lack of evidence of vertical transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 in a sample of the general population in Bissau. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Cock KM, Adjorlolo G, Ekpini E, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of HIV-2: why there is no HIV-2 pandemic. JAMA. 1993;270:2083–2086. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.17.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in context. 2nd. BMJ Publishing Group; London: 2001. chap 15. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulze R, Holling H, Bohning D, editors. Meta-Analysis New Developments and Applications in Medical and Social Sciences. Hogrefe & Huber Publishers; Germany: 2003. chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Houwelingen HC, Arends LR, Stijnen T. Tutorial in Biostatistics: Avdvanced methods in meta-analysis: multivariate apporach and meta-regression. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21:589–624. doi: 10.1002/sim.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baggaley RF, Boily MC, White RG, Alary M. Risk of HIV-1 transmission for parenteral exposure and blood transfusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2006;20(6):805–12. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000218543.46963.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pinkerton SD. Probability of HIV transmission during acute infection in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008 Sep;12(5):677–84. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9329-1. Epub 2007 Dec 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.R language and environment for statistical computing and graphics. http://www.r-project.org/

- 58.Cameron DW, Simonsen JN, D'Costa LJ, et al. Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men. Lancet. 1989;2:403–407. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allen S, Tice J, Van de Perre P, et al. Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. BMJ. 1992;304(6842):1605–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6842.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roth DL, Stewart KE, Clay OJ, et al. Sexual practices of HIV discordant and concordant couples in Rwanda: effects of a testing and counselling programme for men. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:181–188. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nopkesornn T, Mastro TD, Sangkharomya S, et al. HIV-1 infection in young men in Northern Thailand. AIDS. 1993;7:1233–39. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199309000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Satten GA, Mastro TD, Longini IM., Jr Modelling the female-to-male per-act HIV transmission probability in an emerging epidemic in Asia. Stat Med. 1994;13(19-20):2097–106. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mastro TD, Satten GA, Nopkesorn T, et al. Probability of female-to-male transmission of HIV-1 in Thailand. Lancet. 1994;343(8891):204–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90990-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deschamps MM, Pape JW, Hafner A, Johnson WD., Jr Heterosexual transmission of HIV in Haiti. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:324–330. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-4-199608150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duerr A, Hsia J, Nicolosi A, et al. Probability of male-to-female HIV transmission among couples with HIV subtype E and B. Int Conf AIDS. 2000 Jul 9-14;13 [abstract WePpC1319] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duerr A, Xia Z, Nagachinta T, Tovanabutra S, Tansuhaj A, Nelson K. Probability of male-to-female HIV transmission among married couples in in Chiang Mai, Thailand; 10th International Conference on AIDS; Yokahama, Japan. Aug, 1994. [abstr] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Corey L, Wald A, Celum CL, Quinn TC. The effects of herpes simplex virus-2 on HIV-1 acquisition and transmission: a review of two overlapping epidemics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004 Apr 15;35(5):435–45. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hira SK, Feldblum PJ, Kamanga J, et al. Condom and nonoxynol-9 use and the incidence of HIV infection in serodiscordant couples in Zambia. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8:243–250. doi: 10.1258/0956462971919994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ryder RW, Kamenga C, Jingu M, et al. Pregnancy and HIV-1 incidence in 178 married couples with discordant HIV-1 serostatus: additional experience at an HIV-1 counselling centre in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5:482–487. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fideli US, Allen SA, Musonda R, et al. Virologic and immunologic determinants of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:901–910. doi: 10.1089/088922201750290023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kanki P, M’Boup S, Marlink K, et al. Prevalence and risk determinants of Human Immunodeficiency virus type-2 (HIV-2) and Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) in Wes African Female prostitutes. AJE. 1992;36(7):895–907. doi: 10.1093/aje/136.7.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gilbert PB, McKeague IW, Eisen G, et al. Comparison of HIV-1 and HIV-2 infectivity from a prospective cohort study in Senegal. Stat Med. 2003;22(4):573–93. doi: 10.1002/sim.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Donnelly C, Leisenring W, Kanki P, Awerbuch T, Sandberg S. Comparison of transmission rates of HIV-1 and HIV-2 in a cohort of prostitutes in Senegal. Bull Math Biol. 1993;55(4):731–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02460671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rakwar J, Lavreys L, Thompson ML, et al. Cofactors for the acquisition of HIV-1 among heterosexual men: prospective cohort study of trucking company workers in Kenya. AIDS. 1999;13:607–614. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199904010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kimani J, Kaul R, Nagelkerke NJ, et al. Reduced rates of HIV acquisition during unprotected sex by Kenyan female sex workers predating population declines in HIV prevalence. AIDS. 2008 Jan 2;22(1):131–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f27035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hayes RJ, Schulz KF, Plummer FA. The cofactor effect of genital ulcers on the per-exposure risk of HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. J Trop Med Hygiene. 1995;98:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van der Ende ME, Rothbarth P, Stibbe J. Heterosexual transmission of HIV by haemophiliacs. BMJ. 1988;297:1102–1103. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6656.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim HC, Raska K, Clemow L, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in sexually active wives of infected hemophilic men. Am J Med. 1988;85:472–476. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fischl MA, Dickinson GM, Scott GB, et al. Evaluation of heterosexual partners, children, and household contacts of adults with AIDS. JAMA. 1987;257(5):640–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Longini IM, Scott Clark W, Haber M, Horsburgh R., Jr. The stages of HIV infection: waiting times and infection transmission probabilities. In: Castillo-Chavez C, editor. Mathematical and Statistical Approaches to AIDS Epidemiology. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1989. pp. p111–137. Lecture Notes in Biomathematics #83. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jackson JB, Kwork SY, Hopsicker JS, et al. Absence of HIV-1 infection in antibody negative sexual partners of HIV-1 infected hemophiliacs. Transfusion. 1989;29(3):265–267. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1989.29389162735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lawrence DN, Jason JM, Holman RC, Heine P, Evatt BL. Sex practice correlates of human immunodeficiency virus transmission and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome incidence in heterosexual partners and offspring of U.S. hemophilic men. Am J Hematol. 1989;30:68–76. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830300204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim MY, Lagakos SW. Estimating the infecivity of HIV from partner studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 1990;1:117–128. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(90)90003-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wiley JA, Herschkorn SJ, Padian NS. Heterogeneity in the probability of HIV transmission per sexual contact: the case of male-to-female transmission in penile-vaginal intercourse. Stat Med. 1989;8(1):93–102. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kramer I, Yorke JA, Yorke ED. Modelling non-monogamous heterosexual transmission of AIDS. Math Comput Model. 1990;13:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Siddiqui NS, Brown LS, Jr, Phillips RY, Vargas O, Makuch RW. No seroconversions among steady sex partners of methadone-maintained HIV-1-seropositive injecting drug users in New York City. Aids. 1992;6:1529–1533. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199212000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jewell NP, Shiboski SC. Statistical analysis of HIV infectivity based on partner studies. Biometrics. 1990;46:1133–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jewell NP, Malani HM, VIttinghoff E. Non parametric estimation for a form of doubly censored-data, with application to 2 problems in AIDS. J Am Stat Assoc. 1994:19897–19. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Halperin DT, Shiboski SC, Palefsky JM, Padian NS. High level of HIV-1 infection from anal intercourse: a neglected risk factor in heterosexual AIDS prevention; Int Conf AIDS 2002; [abstract ThPeC7438] [Google Scholar]