Abstract

Current data support the idea that hypothalamic neuropeptide orexin A (OxA; hypocretin 1) mediates resistance to high fat diet-induced obesity. We previously demonstrated that OxA elevates spontaneous physical activity (SPA), that rodents with high SPA have higher endogenous orexin sensitivity, and that OxA-induced SPA contributes to obesity resistance in rodents. Recent reports show that OxA can confer neuroprotection against ischemic damage, and may decrease lipid peroxidation. This is noteworthy as independent lines of evidence indicate that diets high in saturated fats can decrease SPA, increase hypothalamic apoptosis, and lead to obesity. Together data suggest OxA may protect against obesity both by inducing SPA and by modulation of anti-apoptotic mechanisms. While OxA effects on SPA are well characterized, little is known about the short- and long-term effects of hypothalamic OxA signaling on intracellular neuronal metabolic status, or the physiological relevance of such signaling to SPA. To address this issue, we evaluated the neuroprotective effects of OxA in a novel immortalized primary embryonic rat hypothalamic cell line. We demonstrate for the first time that OxA increases cell viability during hydrogen peroxide challenge, decreases hydrogen peroxide-induced lipid peroxidative stress, and decreases caspase 3/7 induced apoptosis in an in vitro hypothalamic model. Our data support the hypothesis that OxA may promote obesity resistance both by increasing SPA, and by influencing survival of OxA-responsive hypothalamic neurons. Further identification of the individual mediators of the anti-apoptotic and peroxidative effects of OxA on target neurons could lead to therapies designed to maintain elevated SPA and increase obesity resistance.

Keywords: Orexin, Hypothalamus, Lipid peroxidation, Apoptosis, Caspase-3, Neuroprotection

INTRODUCTION

The orexins (hypocretins) are hypothalamic neuropeptides (orexin A and orexin B; also known as hypocretin-1 and -2) that act on two related G-coupled protein receptors (OxR1 and OxR2) to influence diverse physiological processes such as control of food intake, sleep-wake behavior, arousal, energy balance, and energy expenditure [12, 19, 32, 37]. The most immediate cellular response to orexin receptor activation in both overexpression and in vivo models is increased intracellular Ca2+ influx, by either protein kinase C-dependent activation or by voltage-gated Ca2+ receptors [2, 3]. Additional downstream pathways of activated orexin receptors include the kinase activity of extracellular-signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2) and p38 mitogen activated phosphate kinase (MAPK) [3, 36]. The degree of orexin-induced pathway activation at either receptor appears to be influenced by cell type and specific G-α subunit proteins receptor coupling [3, 18].

The biological control of physical activity is relatively unexplored [25], but is important to body weight regulation. Activities outside of volitional exercise are known as spontaneous physical activity (SPA), which generates non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) [23, 44]. Data suggest that NEAT can vary by as much as 2000 kcal per day between individuals [26], and that NEAT and SPA levels are predictive of weight gain and obesity resistance (OR) in humans [24] and rodents [19]. SPA effects on OR and weight gain depend in part upon OxA signaling in the rostral lateral hypothalamus (rLH) [44]. OxA promotes SPA when injected into rLH, and rats with higher OxA responsiveness have higher gene expression levels for OxA receptors [32, 42, 44]. At present the intracellular signaling mechanisms through which OxA might mediate short- or long-term changes in SPA and OR are unknown.

Given the multiple physiological processes and second messenger pathways it activates, OxA potentially has pleiotropic effects. OxA alters intracellular metabolic function and cell survival in neuronal tissue [15, 39, 40, 49]. OxA-induced neuroprotective mechanisms are due in part to increases in HIF-1α and decreased oxidative stress [15, 39, 49]. OxA increases ATP via induction of the transcription factor hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) in mouse hypothalamic tissue under normoxic conditions [39]. In ischemic conditions, OxA promotes the survival of primary cortical neurons in vitro, and suppresses neuronal damage by regulating post-ischemic glucose intolerance in vivo [15, 39, 40, 49]. No published studies have evaluated the potential neuroprotective effects of OxA in the hypothalamus.

Mounting data suggest that diets high in saturated fats may induce hypothalamic neurodegenerative pathways [29, 45] and contribute to several disease processes including obesity. High fat diets (HFD) are linked to obesity and increases in lipid peroxidative metabolites, induction of oxidative stress, neurodegeneration, and subsequent changes in neural plasticity [14, 48]. Broader hypothalamic neurodegeneration through apoptotic mechanisms induced by HFD consumption and increased oxidative stress has been shown [45, 46]. HFD can promote obesity purely through changes in energy balance, but findings of hypothalamic inflammation, neurodegeneration, and apoptosis imply additional critical factors that have not been fully explored.

It is unclear if these disturbances alter hypothalamic control of SPA, but HFD (particularly high saturated fat diet) increases brain oxidative stress and inflammation in rats [5, 51], whereas moderate physical activity reduces CNS oxidative stress [31]. While OxA signaling promotes SPA [21, 22, 44], and increased SPA protects against obesity [43, 44], whether OxA protects against HFD-induced oxidative stress in the hypothalamus is unknown. Multiple models link changes in OxA or orexin receptors to neurodegenerative conditions [13, 17], suggesting that orexin signaling pathways help maintain neuronal survival. Increased survival of neurons responsible for mediating SPA might explain the long-term benefits of OxA in obesity resistance, but how OXA-induced intracellular mechanisms affect short-term neuronal survival or SPA response is poorly understood.

The lack of appropriate cell lines has proven an obstacle to modeling neuroendocrine mechanisms such as those underlying the pleiotropic effects of OxA. The recent development of immortalized hypothalamic cell lines provides an opportunity for preliminary evaluation of cellular signaling mechanisms without the complexity of the intact architecture of hypothalamus. In this study a novel clonal immortalized embryonic rat hypothalamic cell line was used to evaluate whether OxA protects against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis [4, 28]. Experiments were performed to test whether pretreatment with OxA could increase cell survival, reduce apoptotic caspase activity, and reduce lipid oxidative damage in hypothalamic cells during an oxidative stress challenge using the pro-oxidant hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

METHODS

Cell Culture and Reagents

Immortalized embryonic rat hypothalamic cells (R7; CELLutions-Cedarlane, NC, USA) were used for all studies. R7 clonal cells were derived from E17 rat hypothalamic primary cultures, immortalized by retroviral transfer of simian virus of T antigen subcloned to homogeneity [4, 28]. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 37°C with 5% CO2 and plated at 25,000 per well in 96 well plates. OxA peptide (American Peptides, Sunnyvale, CA USA) was suspended in artificial cerebrospinal fluid and diluted to final concentrations of 50, 100, or 300 nM in DMEM. Hydrogen peroxide (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was diluted to final concentration (50 μM) in DMEM as previously described [47].

For all assays, cells were incubated with DMEM/vehicle, OxA alone, H2O2 alone, or H2O2 plus OxA. Manufacturer protocols were followed for all kits used, and for all assays SpectraMax-M5 reader (Molecular Probes, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used to determine relative fluorescence (RFU) or luminance (RLU).

Real-Time RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR for Ox1R and Ox2R was performed using 200–250 ng of total RNA from Sprague Dawley rat lateral hypothalamus or R7 cells. Extraction methods, PCR primers, and methodology have been previously described [10, 20, 44]. Amplification products were visualized by electrophoresis using a 2% agarose gel stained with SYBR green (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY).

Western Blots

Orexin receptor protein levels were assayed using 50 μg of R7 cell, rat whole hypothalamic tissue (positive control), and human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell (negative control [41]) lysate. Western blots were prepared as previously described [7]. Primary antibodies for Ox1R (AB3092; Millipore, Billerica, MA) and Ox2R (H00003062-Q01; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) were used at a final dilution of 1:1000 and visualized using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Novus) [7].

Calcium Assay

Change in intracellular Ca2+ concentration following incubation with OxA was measured using the Fluo-4 Direct Calcium Assay Kit (Invitrogen).

Viability Assay

Cell viability was determined using a resazurin-based assay (Invitrogen). Data are reported as percent RFU change vs. control.

Caspase Activity

Caspase 3/7 activity was determined by the addition of a DEVD substrate (Promega, Madison WI USA). Data are reported as percent RLU change vs. control.

Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) Assay

Lipid peroxidation was measured by determining the generation of malondialdehyde (MDA; Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) as previously described [11].

Statistical Methods

Significant differences were determined by unpaired, two-tailed t-test using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

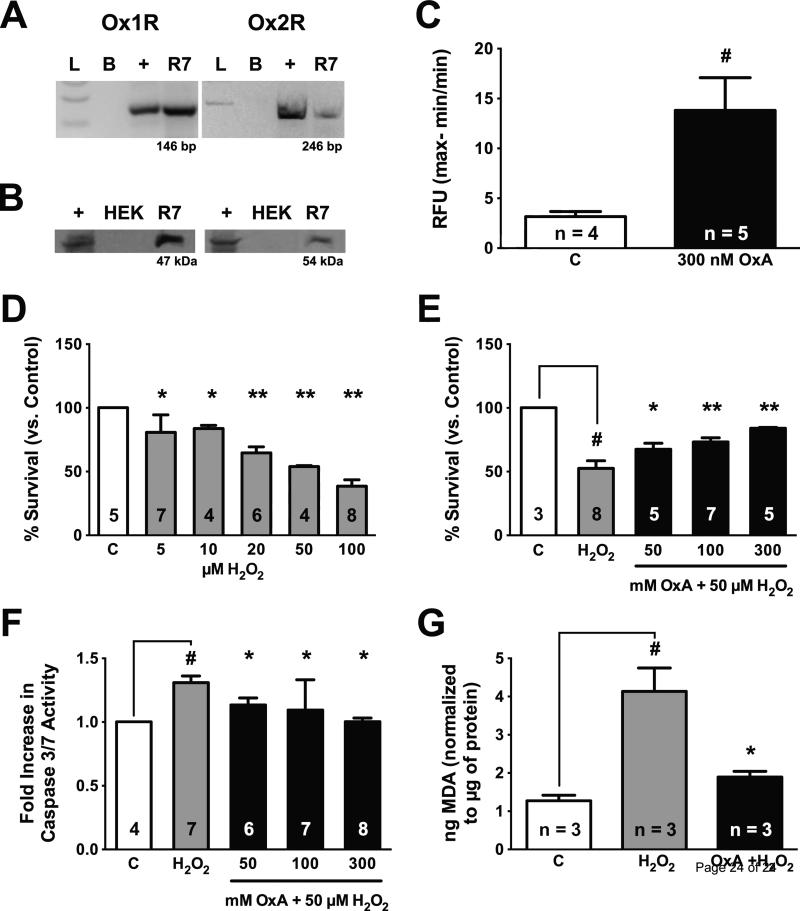

Real-time RT-PCR shows that rat R7 cells express orexin receptor mRNA (Figure 1A), and western blot data show that this mRNA is translated into mature receptor protein (Figure 1B). Receptor function was determined using calcium assay, as the binding of OxA to Ox1R or Ox2R is associated with a robust increase in intracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]i) [16]. R7 cells incubated with 300 nM OxA showed an immediate significant increase in [Ca2+]i (p = 0.0249; Figure 1C). Together these results suggest that R7 cells are a suitable in vitro model for studying the potential pleiotropic effects of OxA.

Figure 1.

(A-C) Rat R7 cells endogenously express functional orexin receptors. (A) Real time RT-PCR demonstrating expression of Ox1R and Ox2R mRNA. L, ladder; B, blank; +, rat lateral hypothalamus positive control; R7, rat R7 cell line. (B) Western blot showing Ox1R and Ox2R receptor protein. +, rat hypothalamic lysate; HEK, human embryonic kidney cell (negative control); R7, rat R7 cell lysate. (C) Calcium assay showing orexin receptors are functional. R7 neurons treated with 300 nM OxA significantly increased intracellular Ca2+ relative to control (p = 0.0249). (D-G) Orexin A pretreatment attenuates H2O2-induced cell death, apoptosis, and lipid peroxidation in R7 cells. (D) 24 h H2O2 treatment significantly and dose-dependently decreased cell viability (fold change in RFU). (E) Pretreatment with OxA significantly and dose-dependently reversed effects of H2O2 challenge. Neurons were pretreated with OxA (50, 100 or 300 nM) for 24 h and then challenged with 50 μM H2O2. Additional dose of OxA was given at the time of H2O2 challenge. Viability was assayed 24 h post-challenge to determine the percentage of living cells. (F) 1 h challenge with 50 μM H2O2 significantly increased caspase 3/7 activity (fold increase in RLU), and 24 h pretreatment with OxA significantly decreased caspase 3/7 activity in H2O2 challenged cells. (G) H2O2 challenged cells showed significantly increased lipid peroxidation (determined by the generation of malondialdehyde (MDA) using the TBARS assay), and OxA pretreatment significantly reduced effects of H2O2. Data in C expressed as relative fluorescent units (RFU); data in D-G normalized relative to controls. Group sizes indicated by numbers on columns. # p < 0.05 vs. control; * p < 0.05 vs. H2O2; ** p < 0.0001 vs. H2O2.

To study the effect of OxA during oxidative stress, we used H2O2, which induces neuronal apoptosis at low concentrations (Figure 1D) [1, 47]. To determine if OxA can prevent H2O2-induced cell death and apoptosis, cells were pretreated for 24 h with different concentrations of OxA (either 0, 50, 100, or 300 nM). Following pretreatment with OxA, cells were then challenged with 50 μM H2O2 for 24 h in the presence of a second dose of 0, 50, 100, or 300 nM OxA. Viability in H2O2-treated cells was significantly reduced (p < 0.0001), and pretreatment with OxA significantly increased viability at all doses (50 nM: p = 0.0009; 100, 300 nM: p < 0.0001), indicating that OxA pretreatment was neuroprotective in a dose dependent manner (Figure 1E).

To test whether OXA pretreatment decreased apoptosis, cells were pretreated with OxA using the doses and time course described above, and caspase 3/7 activity was assayed following a 3 h exposure to 50 μM H2O2. Duration of treatment was based on a prior study examining H2O2-induced apoptosis in primary mouse neuronal culture [47]. Consistent with this previous study, H2O2 treatment significantly increased caspase 3/7 activity relative to controls (p = 0.0075; Figure 1F). Remarkably, at all doses tested, OxA pretreatment significantly decreased caspase activity relative to H2O2-treated cells without pretreatment (50 nM: p = 0.0137; 100 nM: p = 0.0367; 300 nM: p = 0.0108).

OxA has previously been shown to decrease oxidative cell death in mouse cerebral cortical tissue [15]. To determine whether a similar mechanism may exist in hypothalamic cells, we tested if OxA could decrease lipid peroxidation during H2O2 challenge. Cells were pretreated with 300 nM OxA for 24 h and then challenged with 50 nM H2O2 for 24 h as described above. Samples were normalized to μg of protein and reported as ng MDA. H2O2 challenge significantly increased lipid peroxidation relative to controls (p = 0.0103; Figure 1G), and OxA pretreatment significantly decreased lipid peroxidation relative to non-pretreated H2O2-treated cells (p = 0.0236).

DISCUSSION

These data indicate that the novel rat R7 hypothalamic cell line represents a suitable in vitro model for evaluation of OxA-induced changes in cell survival following oxidative stress. A major advantage of the R7 line is derivation from differentiated primary hypothalamic neurons. The resulting cells likely exhibit characteristics more typical of normal hypothalamic cells, and derived cell line data thus more likely represent the potential neuroprotective role of OxA in vivo.

R7 cells express functional orexin receptors (as shown by RT-PCR, western blot, and increased [Ca2+]i following OxA treatment; Figure 1A–C). Consistent with prior publications, H2O2 challenge in R7 cells decreased cell viability (Figure 1D–E), increased caspase activity (Figure 1F), and increased lipid peroxidative damage (Figure 1G). In all cases, OxA pretreatment significantly reversed H2O2-induced damage. These data indicate that OxA neuroprotection may involve decreased onset of caspase-committed apoptosis. This is the first time that OxA has been shown to decrease apoptosis in hypothalamic tissue. Likewise, while OxA has previously been reported to decrease ischemia-induced peroxidative damage in cortex and gastric tissues in vitro and in vivo [6, 15, 49], this is the first report that OxA can reduce peroxidative damage in a hypothalamic cells. Given that hypothalamic regions receive greater innervation by orexin fibers than does cortex [33], OxA-mediated neuroprotective mechanisms established in cortex may be even more important in the hypothalamus.

Little is known about the short- and long-term effects of OxA signaling on intracellular neuronal metabolic status or the physiological relevance of this signaling to SPA. Collectively, emerging evidence indicates that activation of OX1R/OX2R by OxA alters proteins involved in intracellular metabolic function [39]. Recently, OxA has been shown to increase ATP and hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) in hypothalamic tissue under normoxic conditions [39]. This is noteworthy given that HIF-1α increases oxidative phosphorylation. Additional independent studies have shown that HIF-1α expression is regulated in part by mitogen-activated protein kinases and the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α [9, 34, 38]. PGC-1α is a regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, and can simultaneously upregulate genes that protect against oxidative stress, while increasing ATP production [27]. The specific function of PGC-1α in brain and neuronal metabolism is still under investigation, and there is increasing interest in its role in neuronal survival and systemic energy balance [35]. A recent study showed that mice lacking functional HIF-1α and HIF-2α proteins in hypothalamic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons (POMC/HIFβ mice) have impaired energy expenditure, hyperphagia, and increased fat mass [50]. In the same study, viral overexpression of HIF-1α in the mediobasal hypothalamus resulted in obesity resistance during HFD feeding. Mediobasal hypothalamic neuropeptide Y and POMC neurons are directly responsive to OxA [30], and OxA is known to increase HIF-1α expression in target neurons, suggesting at least one direct connection between OxA signaling and intracellular mechanisms that may influence individual resistance to obesity.

Collectively the data here and previously published support the idea that OxA actions on responsive neurons result not only in promotion of short-term behavioral activity outputs such as SPA, but may also trigger pleiotropic cell signaling effects important in mediating long-term changes in OxA responsiveness and cell survival [8]. As earlier work suggests [32, 42], OxA integrates signals that elevate SPA, and these data provide an additional framework in which OxA alters genes that increase intracellular metabolic resistance to HFD-induced oxidative stress. Put into context physiologically, OxA could stimulate neuroprotective mechanisms in OxA-responsive rLH neurons. Increased survival of these SPA-promoting rLH neurons could help individuals resist the damage caused by HFD feeding, conferring resistance to obesity by allowing maintenance of a higher level of both OxA responsiveness and OxA-induced SPA. Conversely, individuals with poor orexin responsiveness might be more susceptible to HFD-induced neurodegeneration, damaging SPA-inducing rLH neurons, leading to obesity. This argument appears to be consistent with previous publications showing that rats resistant to HFD-induced obesity have higher endogenous expression of orexin receptors and greater responsiveness to orexin than do obesity-prone rodents [32, 42, 44]. Future studies evaluating OxA-induced changes in gene expression and regulation of important second messenger pathways in intracellular neuronal metabolism will elucidate the impact of OxA signaling on long-term energy expenditure changes and weight gain propensity. Understanding the long-term metabolic effects of OxA on hypothalamic target neurons could lead to therapies designed to maintain elevated SPA and increase obesity resistance.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Orexin A (hypocretin 1) increases neuroprotection in a hypothalamic cell line

Neuroprotection is partly due to decreases in caspase 3/7 and lipid peroxidation

Suggests mechanism through which orexin could protect against high-fat diet

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Jesús A. Cabrera for assistance with cell culture equipment and scientific comments. Research was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development and R01 DK078985.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ERK1/2

Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2

- HEK

Human embryonic kidney

- HFD

High fat diet

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha

- p38 MAPK

p38 mitogen activated phosphate kinase

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- NEAT

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis

- OR

Obesity resistance

- OxA

Orexin A / Hypocretin 1

- OxR1

Orexin / hypocretin receptor 1

- OxR2

Orexin / hypocretin receptor 2

- POMC

Proopiomelanocortin

- RFU

Relative fluorescent units

- rLH

Rostral lateral hypothalamus

- RLU

Relative luminance units

- RT-PCR

Real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- SPA

Spontaneous physical activity

- TBA

Thiobarbituric acid

- TBARS

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aksenova MV, Aksenov MY, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Cell culture models of oxidative stress and injury in the central nervous system. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 2005;2:73–89. doi: 10.2174/1567202052773463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammoun S, Holmqvist T, Shariatmadari R, Oonk HB, Detheux M, Parmentier M, Akerman KE, Kukkonen JP. Distinct recognition of OX1 and OX2 receptors by orexin peptides. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;305:507–514. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.048025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ammoun S, Johansson L, Ekholm ME, Holmqvist T, Danis AS, Korhonen L, Sergeeva OA, Haas HL, Akerman KE, Kukkonen JP. OX1 orexin receptors activate extracellular signal-regulated kinase in Chinese hamster ovary cells via multiple mechanisms: the role of Ca2+ influx in OX1 receptor signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006;20:80–99. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belsham DD, Cai F, Cui H, Smukler SR, Salapatek AM, Shkreta L. Generation of a phenotypic array of hypothalamic neuronal cell models to study complex neuroendocrine disorders. Endocrinology. 2004;145:393–400. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benani A, Troy S, Carmona MC, Fioramonti X, Lorsignol A, Leloup C, Casteilla L, Penicaud L. Role for mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in brain lipid sensing: redox regulation of food intake. Diabetes. 2007;56:152–160. doi: 10.2337/db06-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulbul M, Tan R, Gemici B, Ongut G, Izgut-Uysal VN. Effect of orexin-a on ischemia-reperfusion-induced gastric damage in rats. J. Gastroenterol. 2008;43:202–207. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butterick TA, Igbavboa U, Eckert GP, Sun GY, Weisman GA, Muller WE, Wood WG. Simvastatin stimulates production of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 via endothelin-1 and NFATc3 in SH-SY5Y cells. Mol. Neurobiol. 2010;41:384–391. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8122-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butterick TA, Nixon JP, Perez-Leighton CE, Billington CJ, Kotz CM. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. Vol. 41. Washington, D.C.: 2011. Orexin A influences lipid peroxidation and neuronal metabolic status in a novel immortalized hypothalamic cell line. p. 88.04. Online. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caretti A, Morel S, Milano G, Fantacci M, Bianciardi P, Ronchi R, Vassalli G, von Segesser LK, Samaja M. Heart HIF-1alpha and MAP kinases during hypoxia: are they associated in vivo? Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2007;232:887–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomczynski P. A reagent for the single-step simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA and proteins from cell and tissue samples. BioTechniques. 1993;15:532–534, 536-537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawn-Linsley M, Ekinci FJ, Ortiz D, Rogers E, Shea TB. Monitoring thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARs) as an assay for oxidative damage in neuronal cultures and central nervous system. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2005;141:219–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dohi K, Ripley B, Fujiki N, Ohtaki H, Shioda S, Aruga T, Nishino S. CSF hypocretin-1/orexin-A concentrations in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) Peptides. 2005;26:2339–2343. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guyenet SJ, Schwartz MW. Clinical review+#: Regulation of food intake, energy balance, and body fat mass: implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:745–755. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harada S, Fujita-Hamabe W, Tokuyama S. Effect of orexin-A on post-ischemic glucose intolerance and neuronal damage. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011;115:155–163. doi: 10.1254/jphs.10264fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmqvist T, Akerman KE, Kukkonen JP. High specificity of human orexin receptors for orexins over neuropeptide Y and other neuropeptides. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;305:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01839-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irving EA, Harrison DC, Babbs AJ, Mayes AC, Campbell CA, Hunter AJ, Upton N, Parsons AA. Increased cortical expression of the orexin-1 receptor following permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 2002;324:53–56. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karteris E, Machado RJ, Chen J, Zervou S, Hillhouse EW, Randeva HS. Food deprivation differentially modulates orexin receptor expression and signaling in rat hypothalamus and adrenal cortex. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;288:E1089–1100. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00351.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotz CM. Integration of feeding and spontaneous physical activity: role for orexin. Physiol. Behav. 2006;88:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotz CM, Levine AS, Billington CJ. Effect of naltrexone on feeding, neuropeptide Y and uncoupling protein gene expression during lactation. Neuroendocrinology. 1997;65:259–264. doi: 10.1159/000127183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotz CM, Teske JA, Levine JA, Wang C. Feeding and activity induced by orexin A in the lateral hypothalamus in rats. Regul. Pept. 2002;104:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotz CM, Wang C, Teske JA, Thorpe AJ, Novak CM, Kiwaki K, Levine JA. Orexin A mediation of time spent moving in rats: neural mechanisms. Neuroscience. 2006;142:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine JA. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;16:679–702. doi: 10.1053/beem.2002.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine JA, Eberhardt NL, Jensen MD. Role of nonexercise activity thermogenesis in resistance to fat gain in humans. Science. 1999;283:212–214. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5399.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine JA, Lanningham-Foster LM, McCrady SK, Krizan AC, Olson LR, Kane PH, Jensen MD, Clark MM. Interindividual variation in posture allocation: possible role in human obesity. Science. 2005;307:584–586. doi: 10.1126/science.1106561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine JA, Vander Weg MW, Hill JO, Klesges RC. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis: the crouching tiger hidden dragon of societal weight gain. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:729–736. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000205848.83210.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang H, Ward WF. PGC-1alpha: a key regulator of energy metabolism. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2006;30:145–151. doi: 10.1152/advan.00052.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer CM, Fick LJ, Gingerich S, Belsham DD. Hypothalamic cell lines to investigate neuroendocrine control mechanisms. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:405–423. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moraes JC, Coope A, Morari J, Cintra DE, Roman EA, Pauli JR, Romanatto T, Carvalheira JB, Oliveira AL, Saad MJ, Velloso LA. High-fat diet induces apoptosis of hypothalamic neurons. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muroya S, Funahashi H, Yamanaka A, Kohno D, Uramura K, Nambu T, Shibahara M, Kuramochi M, Takigawa M, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T, Shioda S, Yada T. Orexins (hypocretins) directly interact with neuropeptide Y, POMC and glucose-responsive neurons to regulate Ca 2+ signaling in a reciprocal manner to leptin: orexigenic neuronal pathways in the mediobasal hypothalamus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;19:1524–1534. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navarro A, Gomez C, Lopez-Cepero JM, Boveris A. Beneficial effects of moderate exercise on mice aging: survival, behavior, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial electron transfer. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2004;286:R505–511. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00208.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nixon JP, Kotz CM, Novak CM, Billington CJ, Teske JA. Neuropeptides controlling energy balance: orexins and neuromedins. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2012:77–109. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-24716-3_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nixon JP, Smale L. A comparative analysis of the distribution of immunoreactive orexin A and B in the brains of nocturnal and diurnal rodents. Behav. Brain Funct. 2007;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Hagan KA, Cocchiglia S, Zhdanov AV, Tambuwala MM, Cummins EP, Monfared M, Agbor TA, Garvey JF, Papkovsky DB, Taylor CT, Allan BB. PGC-1alpha is coupled to HIF-1alpha-dependent gene expression by increasing mitochondrial oxygen consumption in skeletal muscle cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:2188–2193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808801106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onyango IG, Lu J, Rodova M, Lezi E, Crafter AB, Swerdlow RH. Regulation of neuron mitochondrial biogenesis and relevance to brain health. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1802:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramanjaneya M, Conner AC, Chen J, Kumar P, Brown JE, Johren O, Lehnert H, Stanfield PR, Randeva HS. Orexin-stimulated MAP kinase cascades are activated through multiple G-protein signalling pathways in human H295R adrenocortical cells: diverse roles for orexins A and B. J. Endocrinol. 2009;202:249–261. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sang N, Stiehl DP, Bohensky J, Leshchinsky I, Srinivas V, Caro J. MAPK signaling up-regulates the activity of hypoxia-inducible factors by its effects on p300. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:14013–14019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209702200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sikder D, Kodadek T. The neurohormone orexin stimulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 activity. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2995–3005. doi: 10.1101/gad.1584307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sokolowska P, Urbanska A, Namiecinska M, Bieganska K, Zawilska JB. Orexins promote survival of rat cortical neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 2012;506:303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang J, Chen J, Ramanjaneya M, Punn A, Conner AC, Randeva HS. The signalling profile of recombinant human orexin-2 receptor. Cell. Signal. 2008;20:1651–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teske JA, Billington CJ, Kotz CM. Neuropeptidergic mediators of spontaneous physical activity and non-exercise activity thermogenesis. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87:71–90. doi: 10.1159/000110802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teske JA, Billington CJ, Kuskowski MA, Kotz CM. Spontaneous physical activity protects against fat mass gain. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2012;36:603–613. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teske JA, Levine AS, Kuskowski M, Levine JA, Kotz CM. Elevated hypothalamic orexin signaling, sensitivity to orexin A, and spontaneous physical activity in obesity-resistant rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006;291:R889–899. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00536.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thaler JP, Yi CX, Schur EA, Guyenet SJ, Hwang BH, Dietrich MO, Zhao X, Sarruf DA, Izgur V, Maravilla KR, Nguyen HT, Fischer JD, Matsen ME, Wisse BE, Morton GJ, Horvath TL, Baskin DG, Tschop MH, Schwartz MW. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:153–162. doi: 10.1172/JCI59660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Velloso LA, Schwartz MW. Altered hypothalamic function in diet-induced obesity. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2011;35:1455–1465. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whittemore ER, Loo DT, Watt JA, Cotman CW. A detailed analysis of hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death in primary neuronal culture. Neuroscience. 1995;67:921–932. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00108-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu A, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. The interplay between oxidative stress and brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates the outcome of a saturated fat diet on synaptic plasticity and cognition. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;19:1699–1707. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan LB, Dong HL, Zhang HP, Zhao RN, Gong G, Chen XM, Zhang LN, Xiong L. Neuroprotective effect of orexin-A is mediated by an increase of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 activity in rat. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:340–354. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318206ff6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang H, Zhang G, Gonzalez FJ, Park SM, Cai D. Hypoxia-inducible factor directs POMC gene to mediate hypothalamic glucose sensing and energy balance regulation. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang X, Dong F, Ren J, Driscoll MJ, Culver B. High dietary fat induces NADPH oxidase-associated oxidative stress and inflammation in rat cerebral cortex. Exp. Neurol. 2005;191:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]