Abstract

Objective

There is no standardized approach to the initial treatment of polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (pJIA) among pediatric rheumatologists. Understanding the comparative effectiveness of the diverse therapeutic options available will result in better health outcomes for pJIA. The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) developed consensus treatment plans (CTP) for use in clinical practice to facilitate such studies.

Methods

case-based survey was administered to CARRA members to identify the common treatment approaches for new-onset pJIA. Two face-to-face consensus conferences employed modified nominal group technique to identify treatment strategies, operational case definition, endpoints and data elements to be collected. A core workgroup reviewed the relevant literature, refined plans and developed medication dosing and monitoring recommendations.

Results

The initial case-based survey identified significant variability among treatment approaches for new onset pJIA. We developed 3 CTPs based on treatment strategies, for the first 12 months of therapy, as well as case definitions and clinical and laboratory monitoring schedules. The CTPs include a Step-Up Plan (non-biologic DMARD followed by a biologic DMARD), Early Combination Plan (non-biologic and biologic DMARD combined within a month of treatment initiation), and a Biologic Only Plan. This approach was approved by 96% of the CARRA JIA Research Committee members attending the 2013 CARRA face-to-face meeting.

Conclusion

Three standardized CTPs were developed for new-onset pJIA. Coupled with data collection at defined intervals, use of these CTPs will enable the study of their comparative effectiveness in an observational setting to optimize initial management of pJIA.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common pediatric rheumatologic disease, with prevalence estimates ranging from 1–4 per 1,000 children which are similar to the prevalence of Type I diabetes mellitus.1, 2 The term JIA describes a clinically heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by arthritis that begins before age 16 and persists for a minimum of 6 weeks. The majority of children with JIA have a polyarticular form of the disease (pJIA), defined as arthritis in > 4 joints during their disease course. For the purposes of CTP development, pJIA refers to all JIA with > 4 joints involved (cumulatively), excluding children with systemic JIA. This group therefore includes children with rheumatoid factor (RF)+ and (RF)− polyarticular JIA, extended oligoarticular JIA, and children with enthesitis-related (ERA), psoriatic, or undifferentiated JIA and > 4 joints involved. Children with pJIA have a particularly refractory disease course compared to those with fewer joints, with longer periods of active disease which places them at higher risk for joint damage, decreased quality of life, and poorer functional outcomes.3, 4 As with all categories of JIA, the objectives of pJIA treatment are to achieve clinical inactive disease and to prevent long-term morbidities including growth disturbances, joint contractures and destruction, functional limitations, and blindness or visual impairment from chronic uveitis.5

A variety of therapies are currently used in the treatment of pJIA, including both non-biologic and biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Etanercept, adalimumab, tocilizumab, and abatacept are each approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for pJIA. However, FDA approval for these drugs are restricted for children who are at least 2 years (etanercept, tocilizumab), 4 years (adalimumab), or 6 years (abatacept) of age. The initial trials of these medications were designed to obtain regulatory approval, included placebo comparators, and required children to have previously failed additional DMARD therapy.6–8 Subsequent studies have varied in study design and inclusion criteria, making the comparison of medication effectiveness between studies difficult.9 As a result, the comparative effectiveness and safety of these medications is not known, and data are not available regarding the optimal timing of introduction of these medications during the disease course, the optimal combinations of biologic and non-biologic DMARDs, and the relative effectiveness of these medications among JIA categories. In the absence of these data, there is wide variation in treatment practices amongst pediatric rheumatologists.

Large, multi-center randomized controlled trials (RCTs) capable of comparing the efficacy of treatment regimens for pJIA have limited feasibility because of the relatively low prevalence of the disease and the financial and logistical constraints associated with traditional RCTs. Observational studies, and comparative effectiveness research (CER) methodologies specifically, are likely to be more efficient and feasible to execute in such a patient population and these methodologies are central to generating data regarding the relative effectiveness of the available treatments in order to optimize care for children with pJIA. A novel approach to conducting CER is to implement consensus treatment plans (CTPs) within the setting of an observational patient registry in order to reduce treatment variability and allow for comparisons of effectiveness.10 The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA), a North American organization of pediatric rheumatologists who have joined together to facilitate research in these diseases, has developed a multicenter registry of pediatric rheumatic diseases. To date, members of CARRA have collaborated to develop CTPs to facilitate CER in the following diseases: systemic JIA, juvenile dermatomyositis, lupus nephritis, and localized scleroderma.11–15 The objective of this current project was to use consensus methodology to develop CTPs for pJIA for subsequent implementation within the context of the CARRA Registry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The CTP’s were developed through a combination of approaches, including surveys of the CARRA membership and face-to-face meetings using modified nominal group techniques to attain consensus. The face-to-face meetings were conducted at CARRA Annual Scientific Meetings held in June 2011, April 2012, and April 2013.

Initial CARRA membership survey

An electronic, case-based survey of the entire CARRA voting membership was conducted in May 2011 to identify the most commonly used treatment approaches for new-onset pJIA. The survey addressed the treatment of moderate-to-severe pJIA (defined as physician global assessment of 4–7 on a 10-point numeric rating scale with 10 representing the most severe disease) and included patients with RF− pJIA, RF+ pJIA, ERA with or without sacroiliitis, and psoriatic JIA. Subsequently in the consensus process, however, a numerical rating of disease activity was not employed to define the patients for whom these plans would be considered. Participants were asked to provide information about which medications they would use as initial therapy and which medications they would use as subsequent therapy, in the case of inadequate response or no response to the initial therapy.

First face-to-face meeting

The June 2011 CARRA annual meeting was used as an initial working consensus meeting to begin the process of refining and converting the survey results described above into CTPs. Data from the Trial of Early Aggressive Therapy in Polyarticular JIA (TREAT) and the Aggressive Combination Drug Therapy in Very Early Polyarticular JIA (ACUTE-JIA), both of which tested TNFα inhibitors as first-line therapy for pJIA, were also specifically reviewed.16, 17 The group was divided into 3 smaller groups and a modified nominal group technique (NGT) and consensus approach were followed to agree on elements of the operational case definition and general approaches to developing the CTPs.

Role of the core workgroup

A core workgroup of pediatric rheumatologists with specific interest in the treatment of pJIA was convened following the 2011 CARRA meeting. The pJIA CTP core workgroup subsequently met regularly via teleconference throughout the process of CTP development. The workgroup was tasked with using the survey data and results of the initial face-to-face meeting to define preliminary aspects of the protocols, including the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the definition of primary and secondary outcomes for efficacy and safety, the interval between monitoring radiographs for joint damage, reasonable/feasible patient assessment intervals, and the definition of when patients should be considered discontinued from the CTP. The core workgroup examined the indications, dosing and safety monitoring for the medications used in treating polyarticular forms of JIA based on considerations from the published literature, including manuscripts from the RA literature when relevant. This work led to the development of the initial draft CTPs that were presented to the CARRA JIA specific committee at the 2012 CARRA Annual Scientific Meeting (see below). Following the 2012 meeting, the workgroup continued to meet regularly to refine and finalize the CTPs.

Additional face-to-face meetings

At the 2012 CARRA meeting, members of the CARRA JIA research committee were divided into 4 groups, each led by members of the core workgroup, to ensure active participation by all members of the committee. Each group was tasked with in-depth review of the preliminary CTPs, case definition, medication dosing and monitoring plans, and the primary and secondary endpoints. Each group provided feedback to the group at-large regarding areas where there was disagreement.

At the 2013 CARRA meeting, in a single group setting, members of the CARRA JIA research committee re-reviewed the following aspects of the protocols: inclusion and exclusion criteria, the definition of primary and secondary outcomes, patient assessment intervals, and the finalized CTP strategies. After discussion participants were asked to fill out a paper survey indicating whether or not they agreed with the operational case definition, the decision making method outline in the CTP flow diagrams (patient much improved, physician global ≤2 and/or off glucocorticoids), and whether they would be willing to implement the CTPs as outlined. An 80% level of agreement was required for consensus.

RESULTS

The initial CARRA survey was completed by 138 of 230 voting CARRA members (60% response rate). The survey identified substantial variability in the treatment approach for new-onset pJIA (Table 1). The most common therapies across all pJIA categories included NSAIDs, methotrexate (oral or subcutaneous), and glucocorticoids. No one indicated use of an IL-1 inhibitor or rituximab as an initial therapy for any category of pJIA. The frequency of using a non-biologic DMARD alone, biologic DMARD alone, and Non-biologic DMARD and biologic DMARD combination are shown in Table 1. These common strategies are reflected in the final CTPs. NSAIDs, subcutaneous methotrexate, and TNFα inhibitors were the most common therapies that would be added at 3 months for patients with inadequate response across all pJIA categories. For a pJIA patient without poor prognostic risk factors (specified as one or more of the following: positive RF, positive anti-CCP, arthritis of the hip or cervical spine, or radiographic damage) and no response at 3 months, 84% of participants indicated that they would use TNFα inhibitors. While TNFα inhibitors were the most commonly used class of biologic agents for pJIA patients at any time point, 57% of physicians indicated a willingness to use other classes of biologics as the initial biologic treatment.

Table 1.

Initial therapy preferences for pJIA – Results from Provider Survey (n=138)

| pJIA ILAR category | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Typical pJIA, no risk factors* N (%) |

pJIA, with risk factors* N (%) |

ERA, no sacroiliitis N (%) |

ERA, with sacroiliitis N (%) |

PsA N (%) |

Oligo-articular, extended ^ N (%) |

|

|

| ||||||

| Intraarticular glucocorticoid injections | 31 (24) | 34 (27) | 21 (17) | 25 (21) | 23 (19) | 30 (25) |

|

| ||||||

| Glucocorticoids | ||||||

| IV pulse | 3 (2) | 7 (6) | 2 (2) | 5 (4) | 4 (3) | ** |

| Oral, <0.5 mg/kg/day | 38 (30) | 45 (36) | 28 (23) | 27 (23) | 22 (18) | |

| Oral, > 0.5 mg/kg/day | 10 (8) | 24 (19) | 5 (4) | 10 (8) | 5 (4) | |

|

| ||||||

| IL-6 inhibitor | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ** |

|

| ||||||

| Methotrexate (any route) | 103 (81) | 119 (88) | 74 (54) | 66 (49) | 97 (71) | 104 (89) |

| Oral# | 56 (44) | 57 (46) | 40 (32) | 29 (24) | 50 (42) | |

| Subcutaneous# | 54 (43) | 69 (55) | 39 (32) | 44 (37) | 54 (45) | |

|

| ||||||

| NSAIDs | 103 (81) | 85 (68) | 100 (81) | 85 (71) | 98 (82) | 53 (45) |

|

| ||||||

| Sulfasalazine | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 30 (24) | 19 (16) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) |

|

| ||||||

| T cell co-stimulation inhibitor | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | ** |

|

| ||||||

| TNF-alpha inhibitor | 13 (10) | 65 (52) | 23 (19) | 68 (57) | 20 (17) | 71 (62) |

|

| ||||||

| Treatment Strategies | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Non-biologic DMARD alone | 103 (81) | 56 (41) | 76 (56) | 38 (28) | 80 (59) | 46 (34) |

|

| ||||||

| Biologic DMARD alone | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 7 (5) | 31 (23) | 3 (2) | 13 (10) |

|

| ||||||

| Non-biologic DMARD and biologic DMARD | 12 (9) | 63 (46) | 16 (12) | 38 (28) | 17 (13) | 58 (43) |

Medication options were not mutually exclusive.

pJIA: polyarticular JIA; RF: rheumatoid factor; ERA: enthesitis-related arthritis; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; Il-6: interleukin-6; NSAID: non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug; DMARD: disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

Choice of oral and subcutaneous route of methotrexate not mutually exclusive.

Risk factors: positive RF, positive anti-CCP, arthritis of the hip or cervical spine, radiographic damage.

First visit that the oligoarticular JIA patient extends disease to involved more than 4 joints.

Medication not presented as an option.

Seventy-two CARRA members participated in the JIA research committee during the face-to-face consensus meeting in June 2011. Using a modified nominal group technique, greater than 80% consensus was reached on the following items: 1) inclusion of all categories (except systemic JIA) of treatment-naïve JIA presenting prior to their 19th birthday with arthritis for at least 6 weeks affecting 5 or more joints; 2) CTPs defined as treatment “strategies” consisting of varying the timing of introduction of general categories of medications (non-biologic and biologic DMARDs); 3) prior treatment with NSAIDs and/or intra-articular glucocorticoids was allowed; 4) prior treatment with any biologic or non-biologic DMARD (including methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine) would not be allowed. The inclusion of all categories of JIA with polyarticular involvement was based on review of the 2011 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) JIA Treatment Recommendations that similarly grouped these JIA categories.18 Results from the initial CARRA survey (Table 1) indicated that initial therapy tended to be similar for JIA patients with polyarticular involvement regardless of the specific ILAR category to which they belonged. Consensus was not initially obtained on the following issues but was reached in subsequent consensus meetings: 1) CTP duration; 2) duration of biologic DMARD use prior to assessment of response; 3) allowance for prior oral glucocorticoid treatment before starting CTP; 4) dosing of adjunct glucocorticoid with the CTP; 5) inclusion of annual radiographs as a secondary outcome; 6) inclusion of patients with uveitis. The pJIA core workgroup conducted conference calls throughout the year to discuss and refine findings from the survey and face-to-face meeting. The core workgroup also examined the indications, dosing, and safety monitoring for the following medications in depth: glucocorticoids (systemic and intraarticular), non-biologic DMARDs (methotrexate, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine), and biologic DMARDs (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, golimumab, abatacept, tocilizumab, rituximab) (Appendix A). Based on these findings the following strategies were developed to be used as CTPs: Step-Up Plan (non-biologic DMARD followed by a biologic DMARD if inadequate response in 3–6 months, similar to the ACR JIA Treatment Recommendations18; Early Combination Plan (non-biologic and biologic DMARD within a month of treatment initiation, similar to ACUTE-JIA TNF arm and TREAT-JIA most intensive treatment arm16, 17); and Biologic Only Plan (biologic DMARD started without initiation of non-biologic DMARD). These approaches were aligned with the most common treatment timing strategies employed by pediatric rheumatologists in the initial treatment survey.

Fifty-eight CARRA members participated in the JIA research committee workgroup at the 2nd face-to-face consensus meeting in April 2012. After small group breakout sessions and subsequent discussion, 80% consensus was achieved on the following items: operational case definition (including age <19 at onset of symptoms and inclusion of patients with uveitis), data collection time points, disease activity measures to be collected and the medication dosage and monitoring guidelines. Consensus was not reached on whether the primary endpoint should be a pediatric ACR 90 or inactive disease at 6 or 12 months. The pJIA core workgroup met throughout the year to discuss and refine the CTPs and decided that the primary endpoint would be the Pediatric ACR 90 score at 12 months off glucocorticoids. The pJIA core workgroup continued to meet following the face-to-face meeting and discussed the endpoints to be used, and continued to refine the CTPs.

Seventy-two CARRA members participated in the JIA research committee 3rd face-to-face meeting for this project in April 2013. The final operational case definition, CTP flow diagrams, assessment intervals, and primary and secondary endpoints were presented and discussed, followed by voting. Seventy-seven percent of respondents agreed with the operational case definition (Table 2). Ninety-six percent consensus was reached regarding the decision-making method outlined in the CTP flow diagrams (patient much improved, physician global ≤2 and/or off glucocorticoids), and 96% of respondents voted they would be willing to implement the CTPs as currently outlined. Intra-articular glucocorticoid injections are permitted prior to starting on a CTP as long as there are still at least 5 active joints at the baseline visit. Systemic glucocorticoids that are intended as treatment for arthritis are not permitted in the month prior to starting on a CTP.

Table 2.

Operational Case Definition of pJIA

Patient should have:

|

Patients MAY have:

|

Patient should NOT have:

|

The operational case definition is not meant to represent diagnostic or International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) classification criteria for polyarticular JIA.

Swelling within a joint, or limited range of motion with joint pain or tenderness, is observed by a physician, and is not due to primarily mechanical disorders or to other identifiable causes.

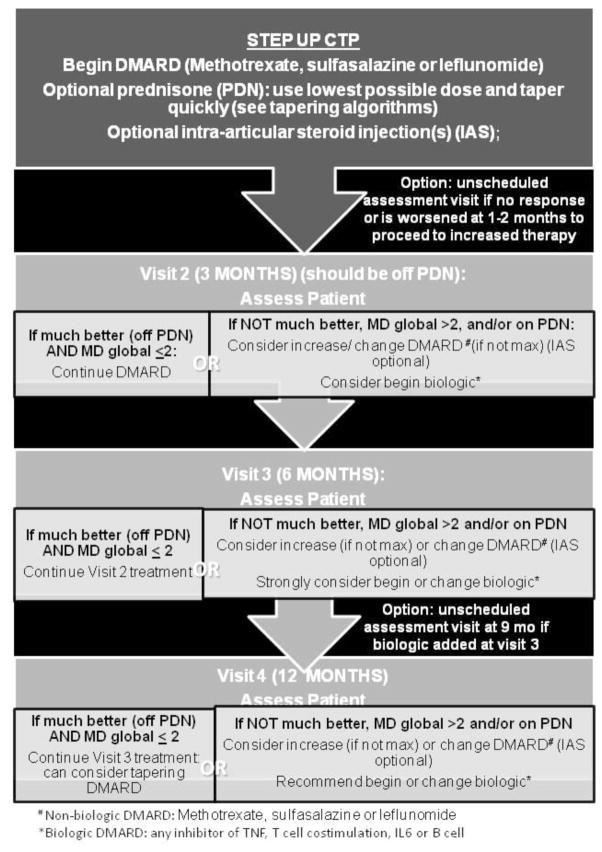

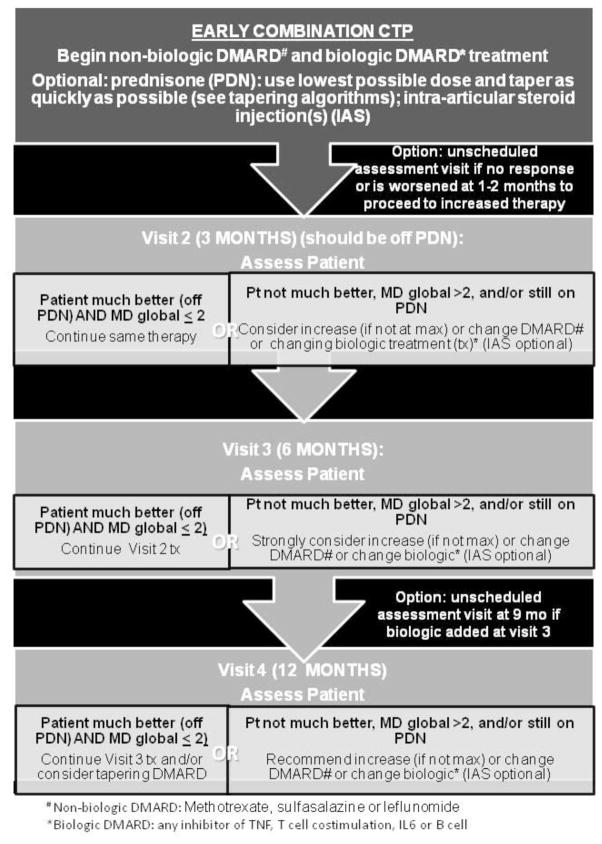

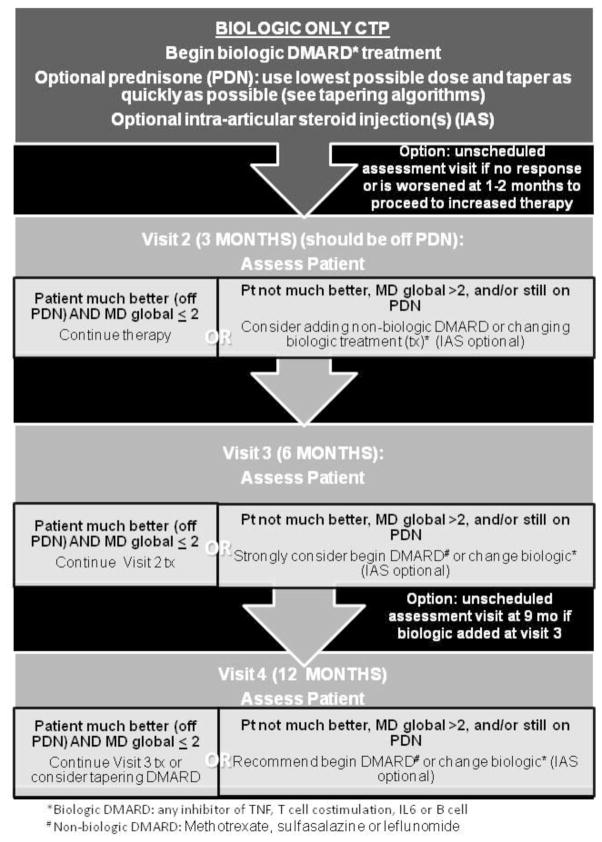

The final CTP flow diagrams are shown in figures 1–3. All strategies suggest treatment modifications at 3–4 month interval assessments in the following circumstances: the patient is not much better, MD global is ≥2, and/or the patient is still on glucocorticoids. Duration of the CTPs is for 12 months after treatment initiation. All 3 CTPs allow concomitant initiation of systemic glucocorticoids. It is recommended that the treating physician discontinue systemic glucocorticoids by 3 months, if possible. Suggested glucocorticoid tapering regimens are shown in Appendix B. The step up strategy allows for an increase in non-biologic DMARD dose, initiation of an alternate non-biologic DMARD, or initiation of a biologic DMARD at 3 months if there is inadequate response. In the early combination strategy patients are started on both a non-biologic DMARD and a biologic DMARD within the first month. The non-biologic DMARD and/or the biologic DMARD can be changed at 3 months if there is an inadequate response. The biologic DMARD only strategy allows for an alternate biologic DMARD at 3 months and/or initiation of a non-biologic DMARD at 6 months if there is inadequate response. A standardized clinical assessment schedule and clinical data collection are shown in Table 3. If medication changes are required and are clinically indicated at interim visits, additional data collection is suggested.

Figure 1. Step Up Strategy CTP.

Non-biologic DMARD at treatment initiation followed by the option to start a biologic DMARD at 3 months or thereafter based on clinical assessment. DMARD= non-biologic DMARD; biologic= biologic DMARD; IAS= intraarticular glucocorticoid injection. DMARD choices include methotrexate, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine. Biologic choices include any inhibitor of TNF, T cell co-stimulation, IL6 or B cells.

Figure 2. Early Combination CTP.

Early Combination Plan defined as a non-biologic and biologic DMARD combined within a month of treatment initiation. DMARD= non-biologic DMARD; biologic= biologic DMARD; IAS= intraarticular glucocorticoid injection. DMARD choices include methotrexate, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine. Biologic choices include any inhibitor of TNF, T cell co-stimulation, IL6 or B cells.

Figure 3. Biologic Only CTP.

Biologic DMARD at treatment initiation followed by the option to start a non-biologic DMARD at 3 months or thereafter based on clinical assessment. DMARD= non-biologic DMARD; biologic= biologic DMARD; IAS= intraarticular glucocorticoid injection. DMARD choices include methotrexate, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine. Biologic choices include any inhibitor of TNF, T cell co-stimulation, IL6 or B cells.

Table 3.

Routine assessment schedule and clinical data collection

Assessment Intervals

|

| Assessments | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Variables | Baseline | Follow-up visits (every 3–4 months) |

|

| ||

| Demographics | ||

| Month/year of birth | X | |

| Sex | X | |

| Race and ethnicity | X | |

| Date of symptom onset | X | |

| Physician assigned ILAR JIA category | X | |

| Clinical variables | ||

| ESR and/or CRP | X | X |

| Number of joints with LROM | X | X |

| Number of joints with swelling | X | X |

| Physician Global Assessment of Disease Activity | X | X |

| Patient/Parent Global Assessment of Disease Activity | X | X |

| CHAQ (Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire) | X | X |

| Morning stiffness (< or ≥15 minutes) | X | X |

| Uveitis | ||

| Present in the 3 months prior to visit | X | X |

| Topical steroid therapy | X | X |

| Quality of Life measure | X | X |

| Medication exposures | ||

| Pre-CTP intraarticular glucocorticoid injections | X | |

| Pre-CTP NSAIDs | X | |

| Pre-CTP hydroxycholoroquine | X | |

| CTP-related exposures | ||

| Intraarticular glucocorticoid injections | X | X |

| Topical or ophthalmic glucocorticoids | X | X |

| Systemic glucocorticoids | X | X |

| Adverse events | ||

| Serious Adverse Events | X | X |

| Important Medical Events | X | X |

| Medication side effects | X | X |

| Reasons for changing treatment | X | X |

| Radiograph of involved joint (wrist/hand preferred) | X | X |

DISCUSSION

This article documents the development of standardized consensus derived treatment plans for polyarticular forms of JIA. CTPs have been developed and are being piloted for systemic JIA.11 These plans focus on evaluating the importance of timing of initiation of various therapeutic classes of medication rather than use of specific medications in pJIA, and address issues that remain unresolved despite recent randomized clinical trials.16, 17 Clinical trials have been conducted successfully to compare the effectiveness of different treatment strategies rather than specific medications for rheumatoid arthritis.19, 20 The CTPs include recommendations on medication dosing and monitoring, and tapering of glucocorticoids along with a recommended schedule of visits and monitoring parameters. These plans are not intended to be identical to each individual clinician’s usual practices, but are intended to represent the general and most common approaches to the treatment of pJIA by pediatric rheumatologists across North America, and were endorsed by consensus formation among CARRA members. Three different CTPs were developed – Step-Up Plan, Early Combination Plan, and Biologic Only Plan (Figures 1–3). These plans are intended for guidance to reduce variation in care. It is anticipated that the fidelity with which clinicians will follow them will be according to their clinical judgment of the patient’s progress. Data regarding adherence to the CTPs will be necessary in order to understand whether there are aspects of the protocols that require modification in order to be feasible in the setting of routine clinical care.

The intent of all CARRA CTPs is to reduce variation in treatments, which together with prospective data collection in a large number of patients, will facilitate comparative research of medication effectiveness, safety, and tolerability in clinical practice in an observational setting like the CARRA Registry. The CARRA Registry is the largest prospective pediatric rheumatic diseases registry in the world, with more than 9,000 patients enrolled in 62 of the more than 100 CARRA sites across North America as of November 2013. By building additional data fields into the basic disease information collected by the Registry, information resulting from the use of the CTPs can be used to learn about the effectiveness of these treatment approaches. Generating knowledge from this approach requires analytic methods to reduce bias and confounding by indication, which may include regression with adjustment for known confounders, propensity scores, and instrumental variable approaches. Given the current variability in treatment patterns evidenced by our surveys, each CTP is expected to be used in patients with differing characteristics and disease activity. As new evidence and knowledge from the use of the CTPs become available, the CTPs will be updated and revised in an iterative fashion.

There was some disagreement at the 3rd face-to-face meeting (2013) about the inclusion of patients with inflammatory arthritis and onset of disease at greater than 16 years as they would not strictly fulfill the ILAR age criteria.21 Despite this, 77% of participants agreed with the operational case definition including this criterion, and 96% agreed that they would use the CTPs as presented. Additionally, in the two previous CARRA consensus meetings, greater than 80% agreement (consensus) had been achieved that the CTPs could be used in patients up to the 19th birthday, as long as the patient agreed to be followed for at least a year. This was a reflection of pediatric rheumatology treatment practices that generally see new patients up until at least 18 years of age rather than based on the ILAR criteria. Lastly, the operational case definition being used for the CARRA systemic JIA CTPs has the same age criterion.11 There was also discussion regarding the inclusion of children with concomitant inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease and trisomy 21. Children with inflammatory bowel disease were ultimately excluded because the majority of participants felt that bowel disease activity would the primary driver of treatment decisions. Patients with celiac disease were excluded since dietary changes may affect their musculoskeletal symptoms, and children with trisomy 21 were excluded because of concerns over sensitivity to medications (such as methotrexate) and the need for individually tailored therapy.22–25

The endpoints were also a topic of discussion: there was general agreement that the primary endpoint should be a meaningful and robust outcome. There was discussion about whether it should be a pediatric ACR 90 score or inactive disease, and whether this should be at 6 or 12 months. Ultimately, it was decided that that the pediatric ACR 90 score was a very robust, meaningful and achievable outcome. Pediatric ACR 90 at twelve months was felt to be clinically meaningful. If there are not significantly different outcomes between the strategies at 12 months then the costs and relative risks of additional months of medication exposure on one strategy versus the others will need to be closely considered. The use of radiographic outcome measures was also a subject of debate because it would not be feasible to have X-rays read in a standardized fashion centrally and the low likelihood that significant X-ray changes would be seen one year from treatment initiation. However, ultimately it was decided that X-ray changes were an important and objective outcome and that most pediatric rheumatologists could agree to obtain X-rays of at least one involved joint at baseline and on a yearly basis.

The CTPs differ from the 2011 ACR JIA Treatment Recommendations in a number of ways. The CTPs are based upon consensus opinion whereas the Recommendations are based on a different process, the RAND/University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Appropriateness Method.18 The RAND/UCLA method is primarily evidence-based with some accounting for expert opinion and specifically does not force consensus. The 2011 ACR Recommendations consider both poor prognostic features and disease activity levels, outline the currently recommended evidence based treatments, and are intended for use in JIA patients with polyarticular involvement at any time during their disease course. In contrast, the pJIA CTPs are developed by consensus, reflect treatment strategies that are in current use by pediatric rheumatologists, and are intended to be initiated in treatment-naïve recent onset pJIA patients. The ACR Treatment Recommendations for pJIA are most similar to the Step-Up CTP, but the CTPs additionally acknowledge that other treatment pathways commonly used by physicians to treat pJIA need to be evaluated (Early Combination and Biologic Only). It is anticipated that data collected from patients treated using CTPs will ultimately help inform future updates of the ACR JIA Treatment Recommendations.

Lastly, there is a effort under way to develop consensus guidelines for treatment and care of pediatric rheumatic diseases in European countries called SHARE (Single Hub and Access point for pediatric Rheumatology in Europe), which will differ from both the ACR JIA Treatment Recommendations and the CTPs.26 SHARE also does not aim to reflect current treatment practices among pediatric rheumatologists, but minimum recommended standards of care based on consensus among pediatric rheumatology expert panels rather than the widespread network-wide consensus process as was used to develop the CTPs.

Limitations of the CTPs include that they do not go beyond the initial 12 months, and do not address medication tapering aside from glucocorticoids. New immunomodulatory agents will need to be incorporated as they become available. The decision making process outlined in the CTPs may need to be adjusted, as ideally this would incorporate continuous measures of disease activity such as the JADAS once meaningful cut-points for decision making are validated.27 Additionally, the CTPs are based upon the practice and opinions of the CARRA physicians who participated in the consensus process, and may not reflect the current practice patterns outside of the North American CARRA membership, particularly in countries where there is less availability of biologics. These CTPs are meant for use in routine clinical care, and the ease of use of these CTPs and decision-making processes should be tested and improved upon through a piloting process prior to widespread dissemination.

CONCLUSIONS

Three CTPs for treatment-naïve pJIA were developed with the goal of reducing variation in care, and to ultimately facilitate evaluation of the comparative effectiveness of treatment selection and the timing of treatment introduction. These plans were acceptable to the majority of CARRA members. Widespread use of these CTPs in clinical practice, along with standardized assessments and data collection, may allow the study of comparative effectiveness of these strategies and will ultimately guide improved and evidence-based decision-making for children and adolescents with new-onset pJIA.

Supplementary Material

Significance and Innovations.

There is significant variability in the treatment of new-onset polyarticular forms of JIA (pJIA) among pediatric rheumatologists in the US and Canada

The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) developed consensus treatment plans (CTP) for new-onset pJIA

These CTPs will facilitate large-scale comparative effectiveness studies through observational registries such as the CARRA Registry

Acknowledgments

Research Support: This work was completed with support from a Rheumatology Research Foundation Disease Targeted Initiative Research Pilot Grant, CARRA, the Arthritis Foundation, the Wasie Foundation and Friends of CARRA. Dr Weiss is supported by grant number K23 AR059749 from the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr Ringold is supported by grant number K12HS019482 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Declared financial relationships include research grant from Hoffman LaRoche (K Onel) and consultant to Hoffman LaRoche (R. Schneider)

The authors would like to acknowledge Soko Setoguchi, MD, DrPH, for her expertise in pharmacoepidemiology and statistics, Brian Feldman, MD, MSc, for his assistance with trial design, and the participants of the CARRA consensus meetings including: Leslie Abramson, Alexandra Aminoff, Sheila Angeles-Han, Timothy Beukelman, April Bingham, James Birmingham, Elizabeth Chalom, Ciaran Duffy, Kimberly Francis, Jennifer Frankovich, Harry Gewanter, Thomas Griffin, Jaime Guzman, Lauren A. Henderson, Adam Huber, Elizabeth Kessler, Daniel Kingsbury, Sivia Lapidus, Melissa Lerman, Clara Lin, Nadia Luca, Melissa Mannion, Jay Mehta, Diana Milojevic, Terry Moore, Kimberly Morishita, Kabita Nanda, Marc Natter, Peter A. Nigrovic, JudyAnn Olson, Michael Ombrello, Christina Pelago, Michael Rapoff, Nanci Rascoff, Tova Ronis, Johannes Roth, Vivian Sapier, Ken Schikler, Heinrike Schmeling, Michael Shishov, Hemalatha Srinivasalu, Lynn Spiegel, Grant Syverson, Heather Tory, Shirley Tse, Marinka Twilt, Carol Wallace, Jennifer E. Weiss, Eveline Wu, Rae Yeung and Lawrence Zemel.

References

- 1.Karvonen M, Viik-Kajander M, Moltchanova E, Libman I, LaPorte R, Tuomilehto J. Incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide. Diabetes Mondiale (DiaMond) Project Group. Diabetes Care. 2000 Oct;23(10):1516–1526. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.10.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacks JJ, Helmick CG, Luo YH, Ilowite NT, Bowyer S. Prevalence of and annual ambulatory health care visits for pediatric arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions in the United States in 2001–2004. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Dec 15;57(8):1439–1445. doi: 10.1002/art.23087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace CA, Huang B, Bandeira M, Ravelli A, Giannini EH. Patterns of clinical remission in select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Nov;52(11):3554–3562. doi: 10.1002/art.21389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ringold S, Seidel KD, Koepsell TD, Wallace CA. Inactive disease in polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis: current patterns and associations. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009 Aug;48(8):972–977. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace CA, Giannini EH, Huang B, Itert L, Ruperto N. American College of Rheumatology provisional criteria for defining clinical inactive disease in select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011 Jul;63(7):929–936. doi: 10.1002/acr.20497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A, et al. Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000 Mar 16;342(11):763–769. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003163421103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Goodman S, et al. Adalimumab with or without methotrexate in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2008 Aug 21;359(8):810–820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, et al. Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial. Lancet. 2008 Aug 2;372(9636):383–391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60998-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otten MH, Anink J, Spronk S, van Suijlekom-Smit LW. Efficacy of biological agents in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic review using indirect comparisons. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Nov 21; doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sox HC, Greenfield S. Comparative effectiveness research: a report from the Institute of Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2010;151(3):203–205. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeWitt EM, Kimura Y, Beukelman T, et al. Consensus treatment plans for new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012 Jul;64(7):1001–1010. doi: 10.1002/acr.21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber AM, Robinson AB, Reed AM, et al. Consensus treatments for moderate juvenile dermatomyositis: beyond the first two months. Results of the second Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance consensus conference. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012 Apr;64(4):546–553. doi: 10.1002/acr.20695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mina R, von Scheven E, Ardoin SP, et al. Consensus treatment plans for induction therapy of newly diagnosed proliferative lupus nephritis in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012 Mar;64(3):375–383. doi: 10.1002/acr.21558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li SC, Torok KS, Pope E, et al. Development of consensus treatment plans for juvenile localized scleroderma: a roadmap toward comparative effectiveness studies in juvenile localized scleroderma. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012 Aug;64(8):1175–1185. doi: 10.1002/acr.21687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huber AM, Giannini EH, Bowyer SL, et al. Protocols for the initial treatment of moderately severe juvenile dermatomyositis: results of a Children’s Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Consensus Conference. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010 Feb;62(2):219–225. doi: 10.1002/acr.20071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace CA, Giannini EH, Spalding SJ, et al. Trial of early aggressive therapy in polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Jun;64(6):2012–2021. doi: 10.1002/art.34343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tynjala P, Vahasalo P, Tarkiainen M, et al. Aggressive combination drug therapy in very early polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ACUTE-JIA): a multicentre randomised open-label clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Sep;70(9):1605–1612. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.143347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beukelman T, Patkar NM, Saag KG, et al. 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011 Apr;63(4):465–482. doi: 10.1002/acr.20460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004 Jul 17–23;364(9430):263–269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16676-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Mar 20;146(6):406–415. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-6-200703200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manner P, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):390–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peeters M, Poon A. Down syndrome and leukemia: unusual clinical aspects and unexpected methotrexate sensitivity. Eur J Pediatr. 1987 Jul;146(4):416–422. doi: 10.1007/BF00444952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lubrano E, Ciacci C, Ames PR, Mazzacca G, Oriente P, Scarpa R. The arthritis of coeliac disease: prevalence and pattern in 200 adult patients. Br J Rheumatol. 1996 Dec;35(12):1314–1318. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.12.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peeters MA, Rethore MO, Lejeune J. In vivo folic acid supplementation partially corrects in vitro methotrexate toxicity in patients with Down syndrome. Br J Haematol. 1995 Mar;89(3):678–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb08390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garre ML, Relling MV, Kalwinsky D, et al. Pharmacokinetics and toxicity of methotrexate in children with Down syndrome and acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Pediatr. 1987 Oct;111(4):606–612. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wulffraat NM, Vastert B. Time to share. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2013;11(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Consolaro A, Ruperto N, Bazso A, et al. Development and validation of a composite disease activity score for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 May 15;61(5):658–666. doi: 10.1002/art.24516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.