Abstract

In human lens proteins, advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) originate from the reaction of glycating agents, e.g., vitamin C and glucose. AGEs have been considered to play a significant role in lens aging and cataract formation. Although several AGEs have been detected in the human lens, the contribution of individual glycating agents to their formation remains unclear. A highly sensitive liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry multimethod was developed that allowed us to quantitate 21 protein modifications in normal and cataractous lenses, respectively. N6-Carboxymethyl lysine, N6-carboxyethyl lysine, N7-carboxyethyl arginine, methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone 1, and N6-lactoyl lysine were found to be the major Maillard protein modifications among these AGEs. The novel vitamin C specific amide AGEs, N6-xylonyl and N6-lyxonyl lysine, but also AGEs from glyoxal were detected, albeit in minor quantities. Among the 21 modifications, AGEs from the Amadori product (derived from the reaction of glucose and lysine) and methylglyoxal were dominant.

The high potential of vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid) for the in vivo Maillard reaction (protein glycation) has been recognized in many studies.1–3 In human eye lenses, vitamin C levels can reach ~3 mM,4 and it is perceived to be a major precursor for advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs). Because of the potential pathogenic role in age-related disorders (age-related macular degeneration)5 as well as vision-impairing diseases (diabetic retinopathy6 and cataract7), the formation of AGE from vitamin C has drawn major attention from many researchers.

Besides ascorbic acid, glucose is known to generate AGEs in lens proteins.8 Although their chemical structures are different, ascorbic acid and glucose generate, in most cases, with the exception of their D- and L-stereochemistry, the very same products.9,10 The α-dicarbonyl compounds, such as threosone, 3-deoxythreosone, or pentosone, that have been measured in human lenses11 are not suitable for evaluating the impact of vitamin C on AGE formation in lens proteins, as these are reactive intermediates in the course of Maillard reactions of both glucose and ascorbic acid. Also, none of the 15 or so protein-bound advanced lysine and arginine modifications that have been detected in the human lens12 allows the distinction between ascorbic acid- and glucose-mediated AGE formation. Furthermore, the situation in the lens becomes even more complex because other AGE precursors like glyoxal and methylglyoxal, which are generated during Maillard degradation, also originate from in vivo pathways (glyoxal from DNA oxidation and lipid peroxidation,13 methylglyoxal from triosephosphate metabolism, ketone bodies, aminoacetone, and catabolism of threonine14).

Recently, we published a mechanistic study of ascorbic acid breakdown, which allowed us to explain 75% of its total degradation pathways in a Maillard reaction model system. We found that the formation of N6-xylonyl/lyxonyl lysine and N6-threonyl lysine (C5 and C4 lysine amide-AGEs) is specific for the Maillard reaction of ascorbic acid degradation products.10

The formation of lens AGEs has been reported before. However, the data published focused on single or very few modifications based on noncomparable workup and analytical approaches. The aim of this work was therefore to quantitate all known major AGEs in individual lenses and then to evaluate the relationship between the novel C5 and C4 lysine amide-AGEs with lens age and cataract. For our study, 25 human lenses of healthy donors between 12 and 74 years of age (normal lenses) were obtained from the Heartland Lions Eye Bank (Columbia, MO), and 20 cataractous lenses from 47- to 96-year-old donors were from Iladevi Cataract and IOL Research Centre. We were able to demonstrate the effect of age and cataract on 21 modifications, 19 of which were AGEs originating from the precursor compounds methylglyoxal, glyoxal, the Amadori product of glucose and lysine, and ascorbic acid, and two oxidized amino acid modifications (AAMs). For this purpose, the target compounds were released from the lens protein by an established enzymatic procedure15 and quantitated by a highly sensitive liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) multimethod.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Chemicals of the highest grade available were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany, or St. Louis, MO) and Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) unless otherwise indicated. Pyrraline was obtained from PolyPeptide Laboratories (Strasbourg, France). N6-Lactoyl lysine,16 glycolic acid lysine amide (GALA),15 glyoxal lysine amide (GOLA),15 N6-oxalyl lysine,10 C4 lysine amide,10 C5 lysine amide,10 N6-carboxymethyl lysine (CML),17 N6-carboxyethyl lysine (CEL),18 argpyrimidine,19 and N7-carboxymethyl arginine (CMA)20 were synthesized according to the literature. Methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone 1 (MG-H1), methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone 3 (MG-H3), N7-carboxyethyl arginine (CEA), and N5-(4-carboxy-4,6-dimethyl-5,6-dihydroxy-1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-yl)-L-ornithine (THP) were isolated from methylglyoxal/arginine reaction mixtures as described in a previous paper by our working group.21 Glucosepane was isolated from a glucose-N1-tBOC-lysine22 and methylglyoxal imidazolimine (MODIC) from a methylglyoxal-N1-tBOC-lysine reaction mixture23 as described by the Lederers group.

Preparation of Lens Proteins

A total of 25 human lenses of healthy donors between 12 and 74 years of age were obtained from the Heartland Lions Eye Bank. Cataractous lenses (47–96-year-old donors) were from Illadevi Cataract and IOL Research Center. Lenses were stored at −80 °C until they were used. Each lens was decapsulated and homogenized in 1.0 mL of 10 mM PBS buffer containing 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4) for 3 min on ice. An aliquot of the homogenate was dialyzed against 10 mM PBS buffer using membrane tubes (cutoff of 6000–8000, Spectrum Laboratories Inc., Rancho Dominguez, CA). The protein was obtained as a powder after lyophilization. Solutions of 3 mg of protein powder/mL of 1 mM PBS buffer were used for the acidic and enzymatic hydrolysis protocol.

Acidic Hydrolysis

Aliquots of protein powder (0.6 mg) were dried, dissolved in 400 μL of 6 N HCl, and heated for 20 h at 110 °C under an argon atmosphere. Volatiles were removed in a vacuum concentrator, and the residue was diluted with water to concentrations appropriate for LC–MS/MS analysis. Prior to injection into the LC system, samples were filtered through 0.45 μm cellulose acetate Costar SpinX filters (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). Each sample was prepared at least three times.

Enzymatic Hydrolysis

Here, a protocol of Glomb and Pfahler15 was used with some small modifications. In brief, 1.5 mg aliquots of protein powder were diluted with 0.5 mL of PBS buffer and treated with enzymes 0.3 unit of Pronase E (two additions), 1 unit of leucine aminopeptidase, and 0.95 unit of carboxypeptidase Y. The enzymes were applied stepwise, and incubations with each were for 24 h at 37 °C in a shaker incubator. A small crystal of thymol was added with the first digestion step. Once the total digestion procedure was completed, reaction mixtures were filtered through molecular weight cutoff 3000 filters (VWR International, Radnor, PA). Filtrates were diluted to appropriate concentrations prior to injection into the LC–MS/MS system. Each sample was prepared at least three times. Effciencies of the acidic and enzymatic hydrolysis for each sample were compared by LC–MS/MS analysis of acid stable CML. Acid hydrolysis was assigned 100% effciency in the test method.

Ninhydrin Assay

The protein content of lens protein solutions was measured by the ninhydrin method with BSA as the reference standard; 0.6 mg of BSA was subjected to acidic hydrolysis and prepared as described above. After complete workup, the absorbance of protein and BSA standard solutions was determined at 546 nm with a microplate reader (Tecan Infinite M200) using 96-well plates. Each sample was prepared at least three times.

Ascorbic Acid Artifact Control Experiment

L-Ascorbic acid (42 mM) and N1-t-BOC-lysine (42 mM) were dissolved in a phosphate-buffered solution (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and incubated at 37 °C in a shaker incubator (New Brunswick Scientific, Nürtingen, Germany) for 4 days. Afterward, 200 μL aliquots of the incubation solution were frozen and stored at −80 °C for different periods of time. After 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 days, samples were thawed and diluted with 6 M HCl to a final HCl concentration of 3 M. For quantitative removal of the BOC protection group, the samples were kept at room temperature for 30 min. Each sample was prepared two times. Solutions were diluted on a scale of 1:5 with water prior to injection into the LC–MS/MS system. The concentrations of the C4 lysine amide stayed at the initial level of 12.1 ± 0.4 pmol/mg of t-BOC-lysine.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Mass Spectrometry Detection (LC–MS/MS)

The high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) apparatus (Jasco, Groß-Umstadt, Germany) consisted of a pump (PU-2080 Plus) with a degasser (LG-2080–02) and a quaternary gradient mixer (LG-2080-04), a column oven (Jasco Jetstream II), and an autosampler (AS-2057 Plus). Mass spectrometric detection was conducted on a API 4000 QTrap LC-MS/MS system (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex, Concord, ON) equipped with a turbo ion spray source using electrospray ionization in positive mode: sprayer capillary voltage of 2.5 kV, nebulizing gas flow of 70 mL min−1, heating gas of 80 mL min−1 at 650 °C, and curtain gas of 30 mL min−1. Chromatographic separations were performed on a stainless steel column packed with RP-18 material (250 mm × 3.0 mm, Eurospher-100 C18A, 5 μm, KNAUER, Berlin, Germany) using a flow rate of 0.7 mL min−1. The mobile phase used was water (solvent A) and methanol with water [7:3 (v/v), solvent B]. To both solvents (A and B) was added 1.2 mL/L heptafluorobutyric acid. Analysis was performed at a column temperature of 25 °C using gradient elution: 2% B (0–9.7 min) to 10% B (16 min) to 60% B (32 min) to 100% B (33.5–40.5 min). For mass spectrometric detection, the scheduled multiple-reaction monitoring (sMRM) mode was used, utilizing collision-induced dissociation (CID) of the protonated molecules with compound specific orifice potentials and fragment specific collision energies (Table 1). Limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ) for all compounds monitored are given also in Table 2. Quantitation was based on the standard addition method. More precisely, increasing concentrations of authentic reference compounds at factors of 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 times the concentration of the analyte in the sample were added to separate aliquots of the sample. The aliquots were analyzed, and a regression of response versus concentration was used to determine the concentration of the analyte in the sample. Calibration with this method resolves potential matrix interference. Data for AGEs obtained by LC–MS/MS showed coeffcients of variation of <10%.

Table 1.

Mass Spectrometry Parameters for AGE and AAM Quantitation

| precursor ion |

product ion 1a |

product ion 2b |

product ion 3b |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE/AAM | retention time (min) | m/z (amu) | DP (V) | m/z (amu) | CE (eV) | CXP (V) | m/z (amu) | CE (eV) | CXP (V) | m/z (amu) | CE (eV) | CXP (V) |

| methionine SOd | 2.7 | 165.9 | 33.0 | 74.2 | 20.0 | 12.0 | 56.1 | 30.0 | 10.0 | 102.1 | 19.0 | 18.0 |

| CML | 3.1 | 205.1 | 50.0 | 130.2 | 17.0 | 9.5 | 84.1 | 46.0 | 13.0 | 56.1 | 59.0 | 8.0 |

| C5 lysine amide | 3.3 | 295.2 | 50.0 | 147.2 | 19.0 | 12.0 | 84.2 | 45.0 | 14.0 | 130.2 | 27.0 | 11.0 |

| C4 lysine amide | 3.3 | 265.2 | 55.0 | 147.1 | 18.0 | 13.0 | 84.2 | 42.0 | 14.0 | 130.2 | 25.0 | 10.0 |

| N6-oxalyl lysine | 3.4 | 219.4 | 50.0 | 112.3 | 20.0 | 7.0 | 84.3 | 40.0 | 13.0 | 156.1 | 22.0 | 12.0 |

| GALA | 4.0 | 205.2 | 40.0 | 142.1 | 20.0 | 11.0 | 84.1 | 36.0 | 14.0 | 159.1 | 15.0 | 13.0 |

| CEL | 4.0 | 219.1 | 54.0 | 84.1 | 33.0 | 7.0 | 130.1 | 18.0 | 11.0 | 56.1 | 59.0 | 8.0 |

| N6-formyl lysine | 4.7 | 175.1 | 40.0 | 112.1 | 20.0 | 13.0 | 84.1 | 35.0 | 7.0 | 129.1 | 15.0 | 13.0 |

| THP | 5.0 | 319.2 | 52.0 | 70.2 | 66.0 | 11.0 | 116.3 | 36.0 | 9.0 | 186.4 | 32.5 | 10.0 |

| N6-lactoyl lysine | 5.7 | 219.2 | 40.0 | 156.2 | 20.0 | 8.0 | 84.1 | 35.0 | 9.0 | 173.1 | 17.0 | 8.0 |

| CMA | 5.7 | 233.1 | 55.0 | 70.1 | 27.5 | 12.0 | 116.1 | 23.0 | 10.0 | 118.2 | 22.0 | 5.5 |

| N6-acetyl lysine | 6.3 | 189.2 | 40.0 | 126.1 | 18.0 | 10.0 | 84.2 | 31.0 | 5.0 | 143.1 | 14.0 | 10.0 |

| CEA | 10.7 | 247.1 | 51.0 | 70.2 | 48.0 | 11.0 | 116.2 | 25.0 | 10.0 | 132.1 | 24.0 | 10.0 |

| MG-H1 | 11.3 | 229.2 | 55.0 | 70.1 | 43.0 | 12.0 | 116.2 | 20.5 | 9.0 | 114.1 | 22.5 | 9.0 |

| MG-H3 | 12.3 | 229.2 | 45.0 | 114.2 | 21.0 | 9.0 | 70.2 | 45.0 | 11.0 | 116.1 | 21.0 | 9.0 |

| GOLA | 15.9 | 333.2 | 45.0 | 84.3 | 54.0 | 13.0 | 169.1 | 26.0 | 12.0 | 130.2 | 32.0 | 9.0 |

| o-tyrosine | 20.6 | 182.1 | 35.0 | 136.2 | 18.0 | 24.0 | 91.1 | 42.0 | 4.5 | 119.1 | 27.0 | 6.2 |

| glucosepane | 23.5/25.4c | 429.3 | 15.0 | 384.5 | 41.0 | 19.0 | 269.2 | 55.0 | 20.0 | 339.2 | 55.0 | 20.0 |

| pyrraline | 26.6 | 255.2 | 38.0 | 175.2 | 17.0 | 13.0 | 237.2 | 12.0 | 19.0 | 148.3 | 29.0 | 13.0 |

| MODIC | 27.3 | 357.3 | 25.0 | 312.2 | 35.0 | 7.0 | 267.3 | 45.0 | 15.0 | 197.4 | 45.0 | 14.0 |

| argpyrimidine | 27.8 | 255.3 | 50.0 | 70.2 | 44.0 | 12.0 | 140.0 | 24.0 | 10.0 | 192.1 | 28.0 | 13.0 |

MRM transition used for quantitation (quantifier).

MRM transition used for confirmation (qualifier).

Two diastereomeric compounds of glucosepane are present in the human lens.

SO is sulfoxide.

Table 2.

Limits of Detection (LOD) and Limits of Quantitation (LOQ) of AGEs and Oxidized AAMs

| AGE/AAM | LOD (pmol/mg of protein)a | LOQ (pmol/mg of protein)a |

|---|---|---|

| methionine SOb | 0.51 | 1.54 |

| CML | 2.44 | 7.33 |

| C5 lysine amide | 0.16 | 0.49 |

| C4 lysine amide | 2.45 | 7.34 |

| N6-oxalyl lysine | 0.24 | 0.73 |

| GALA | 0.84 | 2.53 |

| CEL | 4.17 | 12.50 |

| N6-formyl lysine | 1.75 | 5.25 |

| THP | 0.09 | 0.28 |

| N6-lactoyl lysine | 0.67 | 2.00 |

| CMA | 2.30 | 6.91 |

| N6-acetyl lysine | 1.28 | 3.84 |

| CEA | 1.72 | 5.15 |

| MG-H1 | 1.52 | 4.57 |

| MG-H3 | 6.24 | 18.73 |

| GOLA | 1.10 | 3.30 |

| o-tyrosine | 4.26 | 12.78 |

| glucosepane | 0.91 | 2.74 |

| pyrraline | 0.18 | 0.54 |

| MODIC | 0.22 | 0.67 |

| argpyrimidine | 0.28 | 0.83 |

Replicate analyses (n = 3).

SO is sulfoxide.

Preparative High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Fluorescence Detection (HPLC-FLD)

To obtain fragmentation spectra of vitamin C specific amide-AGEs in lens protein workup solutions, the target material was first enriched by repeated collection from the following HPLC system. The HPLC apparatus (Jasco) consisted of a pump (PU-2080 Plus) with a degasser (LG-2080–54) and a quaternary gradient mixer (LG-2080-04), a column oven (Jasco Jetstream II), an autosampler (AS-2055 Plus), and a fluorescence detector (FP-2020). The fluorescence detector was attuned to 340 nm for excitation and 455 nm for emission. Prior, a postcolumn derivatization reagent was added at a rate of 0.5 mL min−1. This reagent consisted of 0.8 g of o-phthaldialdehyde, 24.73 g of boric acid, 2 mL of 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1 g of Brij35 in 1 L of H2O adjusted to pH 9.75 with KOH. Chromatographic separations were performed on a stainless steel column packed with RP-18 material (model no. 218TP54, 250 mm × 4.0 mm, RP 18, 5 μm, VYDAC CRT, Hesperia, CA) using a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1. The mobile phase used was water (solvent A) or methanol and water [7:3 (v/v), solvent B]. To both solvents (A and B) was added 1.2 mL/L heptafluorobutyric acid. Analysis was performed at a column temperature of 25 °C using isocratic elution at 98% A and 2% B. The retention time of the target analytes was checked with the authentic references. To isolate the amide-AGEs from the lens protein, the HPLC system was used without postcolumn derivatization. After solvent evaporation in vacuo, the residue was dissolved in water and reinjected, using a CID experiment. The fragmentation spectra of the authentic references were obtained with the same parameters. For the C5 lysine amide, the following parameters were used: declustering potential (DP) of 50 V, collision energy (CE) of 30 eV, collision cell exit potential (CXP) of 10 V, and scan range of m/z 60–300 (4 s).

Fluorescence Measurements

The fluorescence (excitation at 335 nm, emission at 385 nm) of protein solutions after enzymatic workup was determined with a fluorometer (FluoroMax 4, Horiba Scientific) after dilution to appropriate concentrations. Each sample was prepared at least three times.

Pigmentation Measurements

The absorbance at 350 nm of protein solutions after enzymatic workup was determined with a microplate reader (Tecan Infinite M200) using 96-well plates. Each sample was prepared at least three times.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Digestion of Lens Protein

The effciency of the enzymatic digestion of lens proteins was calculated on the basis of comparison of N6-carboxymethyl lysine (CML) values measured after acidic hydrolyses. Acid hydrolysis was assigned 100% digestion. On the basis of the CML levels, we estimated that the enzymatic digestion ranged between 52 and 91%. AGE concentrations are expected to be higher in highly cross-linked proteins of aged and cataractous lenses relative to proteins of young lenses. Thus, the enzyme digestion effciency is expected to be lower in aged and cataractous lenses than in young lenses. The effciency ratio was calculated for each single lens to compensate for such effects.

Novel Vitamin C Specific Amide-AGEs

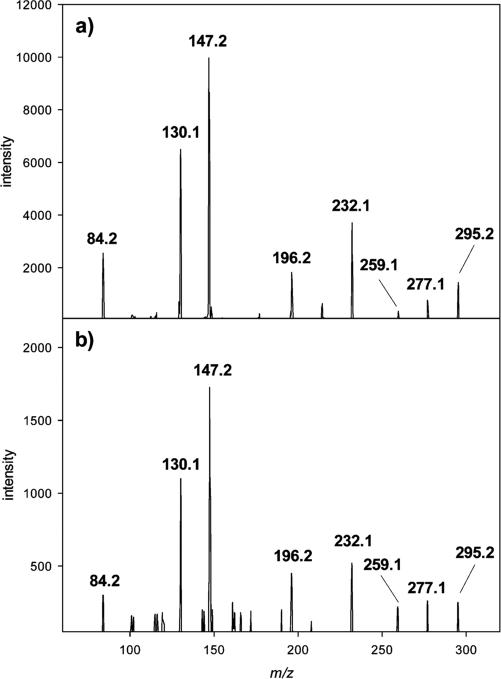

In our previous paper on ascorbic acid degradation in vitro, we proved the formation of specific C4 and C5 lysine amides from 2,3-diketogulonic acid via amine-induced oxidative α-dicarbonyl cleavage and β-dicarbonyl cleavage, and via decarboxylation.10 Here for the first time, the existence of these novel C4 and C5 lysine amide-AGEs was confirmed in lens proteins by mass spectrometric measurements. Figure 1 shows, as a result of a CID experiment, the fragmentation pattern of the C5 lysine amide obtained from a human normal lens compared to that of synthesized N6-xylonyl lysine. The protonated molecular ion [M + H]+ at m/z 295.2 is expected to undergo dehydration to the ions at m/z 277.1 and 259.1. Simultaneous loss of formic acid and ammonia gives the ion at m/z 232.1 starting from the protonated molecular ion, or m/z 196.2 derived from that at m/z 259.1, respectively. The ion at m/z 147.2 presents protonated lysine. Cyclization of the C5 lysine amide to a six-membered ring and elimination of the N6 functionalities yield the ion at m/z 130.1. The ion at m/z 84.2 displays the pyrrolinium ion.

Figure 1.

Verification of C5 lysine amide by collision-induced dissociation (CID) of m/z 295.2 [M + H]+: (a) authentic reference N6-xylonyl lysine and (b) protein workup of normal lenses.

From the mechanistic point of view, it has to be mentioned that degradation of ascorbic acid leads to two diastereomeric amides N6-xylonyl and N6-lyxonyl lysine as explained in our previous paper.10 Because of the co-elution of both compounds in the applied analytical method and because of the virtually same mass spectra, these amides are given as a sum parameter that is termed C5 lysine amide.

Content of Protein Modifications in Human Lenses

Table 3 summarizes the levels of 19 AGEs and the two oxidized amino acid modifications (AAMs), methionine sulfoxide and o-tyrosine, in normal and cataractous lenses. Compared to other studies focusing on selected AGEs levels for methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone 1 (MG-H1), glucosepane, CML, and N6-carboxyethyl lysine (CEL) were within the same range.24–26 To demonstrate the effect of age on protein modifications, correlation coeffcients were calculated for each structure quantitated by LC–MS/MS. Here, correlation coeffcients (r) of >0.8 represent strong and those of >0.6 good positive linear correlations. As AGEs are known to cause lens pigmentation (absorbance at 350 nm) and fluorescence (excitation wavelength of 335 nm, emission wavelength of 385 nm), these parameters were also included.

Table 3.

Contents of AGEs and Oxidized AAMs, Pigmentation, and Fluorescence Matched with the Age of Normal and Cataractous Lenses

| normal lenses (12–74 years of age) |

cataractous lenses (47–96 years of age) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| minimum | maximum | age-matched correlation coefficient (r) | minimum | maximum | mean | age-matched correlation coefficient (r) | |

| AGEs (pmol/mg of protein) | |||||||

| CML (N6-carboxymethyl lysine) | 888 | 5484 | 0.780 | 2279 | 7703 | 4181 | –0.156 |

| CEL (N6-carboxyethyl lysine) | 440 | 1453 | 0.827 | 756 | 1862 | 1303 | –0.047 |

| CMA (N6-carboxymethyl arginine) | 29 | 84 | 0.604 | 37 | 131 | 67 | 0.230 |

| CEA (N6-carboxyethyl arginine) | 150 | 1192 | 0.808 | 287 | 1134 | 582 | 0.388 |

| MG-H1 (methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone 1) | 229 | 1892 | 0.847 | 745 | 2397 | 1341 | 0.386 |

| MG-H3 (methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone 3) | 33 | 500 | 0.741 | 173 | 741 | 328 | 0.110 |

| THP (tetrahydropyrimidine) | 8.0 | 72 | 0.763 | 22 | 168 | 76 | –0.125 |

| argpyrimidine | <LOQ | 18 | 0.608 | 8.5 | 38 | 20 | 0.292 |

| MODIC (methylglyoxal imidazolimine) | 1.3 | 89 | 0.904 | 45 | 250 | 116 | 0.200 |

| glucosepane | 16 | 374 | 0.742 | 93 | 669 | 255 | 0.141 |

| pyrraline | <LOQ | 16 | 0.754 | <LOQ | 6.8 | 3 | –0.539 |

| GOLA (glyoxal lysine amide) | 7.6 | 63 | 0.820 | 43 | 151 | 97 | 0.725 |

| GALA (glycolic acid lysine amide) | 7.5 | 55 | 0.877 | 19 | 79 | 44 | 0.073 |

| N6-lactoyl lysine | 181 | 967 | 0.729 | 240 | 673 | 460 | 0.315 |

| N6-oxalyl lysine | 2.8 | 31 | 0.869 | 11 | 52 | 28 | 0.190 |

| N6-formyl lysine | 169 | 631 | 0.670 | 200 | 648 | 356 | 0.216 |

| N6-acetyl lysine | 1237 | 5506 | 0.239 | 3177 | 7012 | 4375 | 0.073 |

| C4 lysine amide | 33 | 231 | 0.182 | 121 | 582 | 318 | 0.035 |

| C5 lysine amide | 1.9 | 8.3 | 0.811 | 2.9 | 6.6 | 4.4 | 0.237 |

| AAMs (pmol/mg of protein) | |||||||

| methionine SOa (pmol/mg of protein) | 861 | 7424 | 0.936 | 306 | 1750 | 812 | 0.050 |

| o-tyrosine (pmol/mg of protein) | 75 | 306 | 0.728 | 91 | 718 | 290 | 0.415 |

| fluorescence (excitation at 335 nm/emission at 385 nm, arbitrary units) | 4.70 | 29.16b | 0.881 | 16.13 | 77.57b | 39.66b | 0.116 |

| pigmentation (absorbance at 350 nm, arbitrary units) | 0.078 | 0.147 | 0.872 | 0.107 | 0.192 | 0.137 | 0.248 |

SO is sulfoxide.

Values × 104.

In cataractous lenses, a weak, negligible, or negative correlation of age to the protein modifications was observed with the exception of GOLA. This single high correlation cannot be explained and appears to be entirely random. Nevertheless, the overall finding confirmed that AGE levels in cataracts are higher than in normal aging lenses.

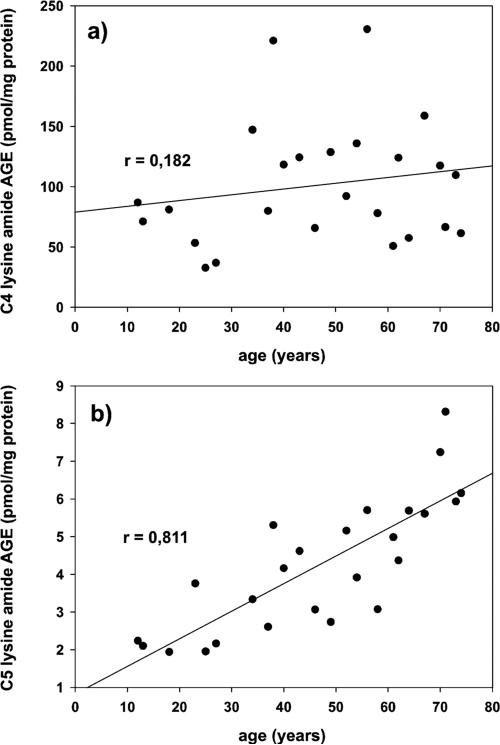

On the other hand in normal lenses, 9 of the 21 protein modifications showed strong and 10 moderately good positive linear correlations to age. Surprisingly, N6-acetyl lysine (r = 0.239) and the C4 lysine amide (r = 0.182) did not exhibit this relationship.

Stable amide-AGEs are expected to accumulate along with the other AGEs and oxidized AAMs during lens aging because of negligible turnover rates of the protein. The acetylation of the lens protein was already published and discussed to enhance the chaperone function of αA-crystallin.27 Compared to other amides, N6-acetyl lysine occurs in much higher concentrations in the lens (factor of ~10 to ~100) that might be explained by additional non-Maillard in vivo reactions as they are known, e.g., for enzymatic histone acetylation.28 The existence of these additional and presumably enzymatic pathways is further reflected by the negligible correlation of N6-acetyl lysine to age in normal lenses.

Unexpectedly, the C4 lysine amide did not correlate with donor age in contrast to the C5 lysine amide (see Figure 2), both supposed to be vitamin C specific protein modifications. As ascorbic acid oxidation was reported to proceed below freezing temperatures29 and the C4 lysine amide is indeed a product of a Bayer Villiger oxidation of 2,3-diketogulonic acid,10 we conducted a control experiment to overcome the notion that noncorrelating amide levels might be a product of oxidative artifact formation during storage and workup of the lenses. L-Ascorbic acid and t-BOC-lysine were incubated under physiological conditions for 4 days to produce an initial concentration of C4 lysine amide close to the measured amounts in the lenses. Starting from this point aliquots of the incubation solution were frozen and stored at −80 °C for different time periods of ≤25 days. No changes in the C4 lysine amide concentration were observed. This means that in contrast to literature, where high concentrations of ascorbic acid and large solution volumes were used,29 the specific storage and workup conditions used herein did not produce any false positive artifacts from ascorbic acid leading, e.g., to the C4 lysine amide but also to other AGEs formed via oxidative pathways. This result was further substantiated by the fact that the counterpart of the C4 lysine amide in the Bayer Villiger oxidation of 2,3-diketogulonic acid N6-oxalyl lysine indeed showed a strong correlation to the donor age. Taken together, this strongly implies that the C4 lysine amide does only result in part from the oxidative cleavage reaction of ascorbic acid and that in addition major other unknown pathways must occur in the lens to lead to this specific amide-AGE (due to unknown in vivo precursors, and the fact that the stereochemistry cannot be differentiated with the present analytical method, the term “C4 lysine amide” instead of N6-threonyl lysine is used herein).

Figure 2.

Effect of age on the (a) C4 and (b) C5 lysine amide content in human normal lens protein.

Mechanistically, the C5 lysine amides originate via decarboxylation from the hemiaminal of 2,3-diketogulonic acid with lysine. In the degradation pathways of ascorbic acid, the corresponding carboxylic acids are formed as competitive, much more dominant reaction products to the amides in aqueous systems. In our model system, 12% of ascorbic acid's total degradation resulted in C5 carboxylic acids and 60% in oxalic acid.10 On the basis of this fact, N6-oxalyl lysine and the C5 lysine amides are also expected to be dominant AGEs when assuming that degradation mechanisms in vitro can be transferred to the in vivo situation and that ascorbic acid has a strong impact on lens protein modification. However, in comparison to concentrations of most measured AGEs in normal lenses, the C5 lysine amide and N6-oxalyl lysine (maximal concentrations of 8.3 and 31 pmol/mg of lens protein in normal lenses, respectively) are formed in only relatively small amounts. Thus, we must conclude that the C5 lysine amide as the single vitamin C specific parameter is quantitatively not as significant as other protein modifications.

Precursor Compounds of Advanced Glycation End-products

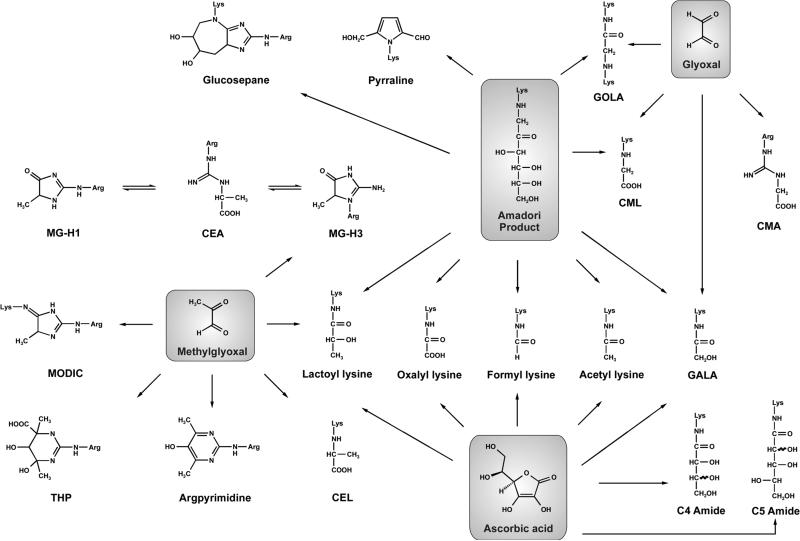

As documented in Table 3, major Maillard protein modifications among the 19 measured in the lens are CML, CEL, N7-carboxyethyl arginine (CEA), MG-H1, and N6-lactoyl lysine with maximal concentrations of 5484, 1453, 1192, 1892, and 967 pmol/mg of lens protein in normal lenses, respectively. Scheme 1 reveals the formation pathways of 19 AGEs present in the lens, which are generated from the precursors methylglyoxal, glyoxal, ascorbic acid, and the Amadori product of glucose and lysine (fructose lysine).

Scheme 1.

In the Human Lens, 19 AGEs Are Formed from the Amadori Product (fructose lysine), Methylglyoxal, Glyoxal, and Ascorbic Acid

CML, the most abundant lens AGE, is known to be formed from ascorbic acid, fructose lysine, and glyoxal. Dunn et al. proposed a mechanism of formation for CML from the Amadori product of threose during degradation of ascorbic acid.30 On the other hand, in our study of ascorbic acid breakdown threose was not detected as a degradation product.10 Thus, on the basis of the current literature, the formation of CML from glyoxal, which has been established in the course of ascorbate breakdown, is the only experimental proven pathway to lead to CML from ascorbic acid. Fructose lysine and glyoxal remain therefore as the two direct CML precursors. First, fructose lysine through oxidative fragmentation releases CML and erythronic acid as the counterproduct;31 second, CML formation occurs via hydration and tautomerization of the imine after nucleophilic attack of lysine at the carbonyl moiety of glyoxal.15 However, the impact of glyoxal on CML formation in lens appears to be low considering the relatively minor amounts of N7-carboxymethyl arginine (CMA, maximal concentration of 84 pmol/mg lens of protein in normal lenses) because CMA is solely generated from the reaction of glyoxal with arginine residues. If the rearrangement reaction leading from glyoxal to CML proceeds to the imine carbon atom GALA (glycolic acid lysine amide) is formed, which was verified in normal lenses as a quantitatively minor AGE. In vitro in glyoxal lysine incubations, GOLA (glyoxal lysine amide) as a lysine–lysine cross-link structure was generated unlike here only at trace levels compared to GALA but can be formed alternatively from the oxidative cleavage of fructose lysine like CML.15 We can thus conclude that CML and at much lower concentrations also GOLA originate almost entirely from fructose lysine via oxidative processes in vivo, which are independently envisioned by the formation of significant amounts of methionine sulfoxide and especially of o-tyrosine (up to 7424 and 306 pmol/mg of protein in normal lenses, respectively).

Once established as a parameter of heat-treated food32 and formed nonoxidatively via the 3-deoxyglucosone route from fructose lysine,33 pyrraline is expected in negligible amounts at physiological temperatures, which was supported by the results of the study presented here (maximal concentration of 16 pmol/mg of lens protein in normal lenses). Interestingly, considerably high levels of glucosepane (maximal concentration of 374 pmol/mg of protein in normal lenses) were observed. This AGE is derived from the long-range carbonyl shift within the Amadori structure.34 Hence, fructose lysine or its precursor glucose appears to be a major protein modifier in the lens.

The remaining prominent lens AGEs, CEL, CEA, MG-H1, and N6-lactoyl lysine, all belong to the group of methylglyoxal-derived AGEs. The CEL formation pathway proceeds like the nonoxidative route for CML from glyoxal after nucleophilic attack of lysine at the ketone function of methylglyoxal.35 On the other hand at approximately half the concentration, nucleophilic attack at the aldehyde moiety results in N6-lactoyl lysine after keto–enol rearrangement.36 Furthermore, the reaction of methylglyoxal with arginine leads to methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone 3 (MG-H3) via a dihydroxyimidazolidine intermediate. The kinetically controlled MG-H3 is in an equilibrium with the thermodynamically more stable product MG-H1 via CEA,21 which fits well to the measured amounts in lens. The importance of methylglyoxal modifications over glyoxal modifications was also highlighted by the detection of the lysine–arginine cross-link structure MODIC (methylglyoxal imidazolimine, up to 89 pmol/mg of protein in normal lenses), while the respective glyoxal analogue GODIC (glyoxal imidazolimine) was not found. Although methylglyoxal is formed from ascorbic acid10 and glucose9 through Maillard chemistry, major parts of methylglyoxal in vivo can be traced back to the various physiological sources mentioned above.14 Regardless of its origin, methylglyoxal was found to be another major AGE precursor.

The low levels of ascorbic acid specific amide-AGEs were somewhat surprising because ascorbic acid has been perceived to be the dominant AGE precursor in the lens. It is possible that in the lens milieu, pathways leading to amide AGE formation are not favored. It should be noted here that the reaction of ascorbic acid with lens proteins generates a vast array of AGEs that possess mass spectral signatures identical to those in brunescent cataracts.3 However, their structure is not known. Additionally, Linetsky et al. demonstrated in in vitro experiments that tryptophan oxidation products, which are present in large amounts in the lens, can promote synthesis of 2,3-diketogulonic acid from vitamin C. This step is prerequisite for ascorbate-mediated AGE formation in the lens milieu.37 It should be noted that established lens AGEs, e.g., OP-lysine,38 K2P,39 CML,35 or N6-oxalyl lysine,40 can be traced back to carbohydrates derived from different sources apart from ascorbic acid as stated above. Given these observations, it must be strongly hypothesized that quantitative major ascorbic acid AGEs still need to be uncovered beside the specific but minor C5 amides.

CONCLUSION

With the LC–MS/MS multimethod presented here, a large spectrum of AGEs was quantitated for the first time simultaneously in the human lens. As shown in Scheme 1, these AGEs can be formed from the precursors methylglyoxal, glyoxal, the Amadori product of glucose and lysine, and vitamin C. The results of this study allowed us to evaluate the impact on AGE formation of each precursor in the lens. On the basis of the amounts of CML and glucosepane, the Amadori product of glucose and lysine appears to be the dominant AGE precursor in the lens at least for the broad array of structures targeted herein. The contribution of methylglyoxal to AGE formation is also significant. In contrast, the high concentrations of N6-acetyl lysine cannot be linked to Maillard chemistry. Thus, the formation pathways of this amide-AGE remain unclear.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by research grants from the Josef Schormüller-Gedächtnisstiftung (Berlin, Germany) and National Institutes of Health Grants EY022061, EY023286 (R.H.N.), and P30EY-11373 (Case Western Reserve University), Research to Prevent Blindness NY, and The Ohio Lions Eye Research Foundation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AGE

advanced glycation end product

- AAM

amino acid modification

- CML

N6-carboxymethyl lysine

- CEL

N6-carboxyethyl lysine

- CMA

N6-carboxymethyl arginine

- CEA

N6-carboxyethyl arginine

- GALA

glycolic acid lysine amide

- GOLA

glyoxal lysine amide

- MG-H

methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone

- THP

N5-(4-carboxy-4,6-dimethyl-5,6-dihydroxy-1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidin-2-yl)-L-ornithine

- MODIC

methylglyoxal imidazolimine

- GODIC

glyoxal imidazolimine

- OP-lysine

2-ammonio-6-(3-oxido-pyridinium-1-yl)hexanoate

- K2P

1-(5-amino-5-carboxypentyl)-4-(5-amino-5-carboxypentylamino)-3-hydroxy-2,3-dihydropyridinium

- BOC

butoxycarbonyl

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- ESI

electron spray ionization

- sMRM

scheduled multiple-reaction monitoring

- CID

collision-induced dissociation

- DP

declustering potential

- CE

collision energy

- CXP

collision cell exit potential

- LOD

limit of detection

- LOQ

limit of quantitation

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orwerth BJ, Olesen PR. Ascorbic acid-induced crosslinking of lens proteins: Evidence supporting a Maillard reaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1988;956:10–22. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(88)90292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan X, Reneker L, Obrenovich ME, Strauch C, Cheng R, Jarvis SM, Ortwerth BJ, Monnier VM. Vitamin C mediates chemical aging of lens crystallins by the Maillard reaction in a humanized mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:16912–16917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605101103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng R, Feng Q, Orwerth BJ. LC-MS display of the total modified amino acids in cataract lens proteins and in lens proteins glycated by ascorbic acid in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1762:533–543. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor A, Jacques PF, Nowell T, Perrone G, Blumberg J, Handelman G, Jozwiak B, Nadler D. Vitamin C in human and guinea pig aqueous, lens and plasma in relation to intake. Curr. Eye Res. 1997;16:857–864. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.16.9.857.5039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagai R, Mori T, Yamamoto Y, Kaji Y, Yonei Y. Significance of Advanced Glycation End Products in Aging-Related Disease. Anti-Aging Medicine. 2010;7:112–119. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stitt AW. AGEs and Diabetic Retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 2010;51:4867–4874. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franke S, Dawczynski J, Strobel J, Niwa T, Stahl P, Stein G. Increased levels of advanced glycation end products in human cataractous lenses. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 2003;29:998–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01841-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monnier VM, Cerami A. Nonenzymatic browning in vivo: Possible process for aging of long-lived proteins. Science. 1981;211:491–493. doi: 10.1126/science.6779377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gobert J, Glomb MA. Degradation of glucose: Reinvestigation of reactive α-dicarbonyl compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:8591–8597. doi: 10.1021/jf9019085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smuda M, Glomb MA. Maillard degradation pathways of vitamin C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:4887–4891. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nemet I, Monnier VM. Vitamin C degradation products and pathways in the human lens. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:37128–37136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.245100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagaraj RH, Linetsky M, Stitt AW. The pathogenic role of Maillard reaction in the aging eye. Amino Acids. 2012;42:1205–1220. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0778-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu MX, Requena JR, Jenkins AJ, Lyons TJ, Baynes JW, Thorpe SR. The advanced glycation end product, Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine, is a product of both lipid peroxidation and glycoxidation reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:9982–9986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.9982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Methylglyoxal, glyoxalase 1 and the dicarbonyl proteome. Amino Acids. 2012;42:1133–1142. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0783-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glomb MA, Pfahler C. Amides are novel protein modifications formed by physiological sugars. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:41638–41647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smuda M, Voigt M, Glomb MA. Degradation of 1-deoxy-d-erythro-hexo-2,3-diulose in the presence of lysine leads to formation of carboxylic acid amides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:6458–6464. doi: 10.1021/jf100334r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glomb MA, Monnier VM. Mechanism of protein modification by glyoxal and glycolaldehyde, reactive intermediates of the Maillard reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:10017–10026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujioka M, Tanaka M. Enzymic and chemical synthesis of ε-N-(l-propionyl-2)-l-lysine. Eur. J. Biochem. 1978;90:297–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shipanova IN, Glomb MA, Nagaraj RH. Protein modification by methylglyoxal: Chemical nature and synthetic mechanism of a major fluorescent adduct. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. Eur. 1997;344:29–36. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iijima K, Murata M, Takahara H, Irie S, Fujimoto D. Identification of Nω-carboxymethylarginine as a novel acid-labile advanced glycation end product in collagen. Biochem. J. 2000;347:23–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klöpfer A, Spanneberg R, Glomb MA. Formation of arginine modifications in a model system of Nα-tertbutoxycarbonyl (Boc)-arginine with methylglyoxal. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59:394–401. doi: 10.1021/jf103116c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lederer MO, Bühler HP. Cross-linking of proteins by Maillard processes: Characterization and detection of a lysine-arginine cross-link derived from d-glucose. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999;7:1081–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lederer MO, Klaiber RG. Cross-linking of proteins by Maillard processes: Characterization and detection of lysine-arginine cross-links derived from glyoxal and methylglyoxal. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999;7:2499–2507. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed N, Thornalley PJ, Dawczynski J, Franke S, Strobel J, Stein G, Haik GM. Methylglyoxal-derived hydroimidazolone advanced glycation endproducts of human lens proteins. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 2003;44:5287–5292. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan X, Sell DR, Zhang J, Nemet I, Theves M, Lu J, Strauch C, Halushka MK, Monnier VM. Anaerobic vs aerobic pathways of carbonyl and oxidant stress in human lens and skin during aging and in diabetis: A comparative analysis. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2010;49:847–856. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franke S, Dawczynski J, Strobel J, Niwa T, Stahl P, Stein G. Increased levels of advanced glycation end products in human cataractous lenses. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 2003;29:998–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01841-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagaraj RH, Nahomi RB, Shanthakumar S, Linetsky M, Padmanabha S, Pasupuleti N, Wang B, Santhoshkumar P, Panda AK, Biswas A. Acetylation of αA-crystallin in the human lens: Effects on structure and chaperone function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1822:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allfrey VG, Faulkner R, Mirsky AE. Acetylation and methylation of histones and their possible role in the regulation of RNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1964;51:786–794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.51.5.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson LU, Fennema O. Effect of freezing on oxidation of l-ascorbid acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1971;19:121–124. doi: 10.1021/jf60173a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunn JA, Ahmed MU, Murtiashaw MH, Richardson JM, Walla MD, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Reaction of ascorbate with lysine and protein under autoxidizing conditions: Formation of Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine by reaction between lysine and products of autoxidation of ascorbate. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10964–10970. doi: 10.1021/bi00501a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed MU, Dunn JA, Walla MD, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Oxidative degradation of glucose adducts to protein. Formation of 3-(Nε-lysino)-lactic acid from model compounds and glycated proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:8816–8821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiang GH. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of ε-pyrrole lysine in processed food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1988;36:506–509. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Förster A, Henle T. Glycation in food and metabolic transit of dietary AGEs (advanced glycation end-products): Studies on the urinary excretion of pyrraline. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31:1383–1385. doi: 10.1042/bst0311383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biemel KM, Conrad J, Lederer MO. Unexpected carbonyl mobility in aminoketoses: The key to major Maillard crosslinks. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:801–804. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020301)41:5<801::aid-anie801>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmed MU, Brinkmann Frye E, Degenhardt TE, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. N-ε-(Carboxyethyl)lysine, a product of the chemical modification of proteins by methylglyoxal, increases with age in human lens proteins. Biochem. J. 1997;324:565–570. doi: 10.1042/bj3240565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henning C, Smuda M, Girndt M, Ulrich C, Glomb MA. Molecular basis of Maillard amide-advanced glycation end product (AGE) formation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:44350–44356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.282442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linetsky M, Raghavan CT, Johar K, Fan X, Monnier VM, Vasavada AR, Nagaraj RH. UVA light-exited kynurenines oxidize ascorbate and modify lens proteins through the formation of advanced glycation endproducts. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:17111–17123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.554410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Argirov OK, Lin B, Orwerth BJ. 2-Ammonio-6-(3-oxidopyridinium-1-yl)hexanoate (OP-lysine) is a newly identified advanced glycation end product in cataractous and aged human lenses. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;279:6487–6495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng R, Feng Q, Argirov OK, Orwerth BJ. K2P: A novel cross-link from human lens protein. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1043:184–194. doi: 10.1196/annals.1333.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagaraj RH, Shamsi FA, Huber B, Pischetsrieder M. Immunochemical detection of oxalate monoalkylamide, an ascorbate-derived Maillard reaction product in the human lens. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:327–330. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]