Abstract

Growing evidence indicates that various chronic pain syndromes exhibit tissue abnormalities caused by microvasculature dysfunction in the blood vessels of skin, muscle or nerve. We tested whether topical combinations aimed at improving microvascular function would relieve allodynia in animal models of complex regional pain syndrome type I (CRPS-I) and neuropathic pain. We hypothesized that topical administration of either α2-adrenergic (α2A) receptor agonists or nitric oxide (NO) donors combined with either phosphodiesterase (PDE) or phosphatidic acid (PA) inhibitors would effectively reduce allodynia in these animal models of chronic pain. Single topical agents produced significant dose-dependent anti-allodynic effects in rats with chronic post-ischemia pain, and the anti-allodynic dose-response curves of PDE and PA inhibitors were shifted 2.5–10 fold leftward when combined with non-analgesic doses of α2A receptor agonists or NO donors. Topical combinations also produced significant anti-allodynic effects in rats with sciatic nerve injury, painful diabetic neuropathy and chemotherapy-induced painful neuropathy. These effects were shown to be produced by a local action, lasted up to 6 h after acute treatment, and did not produce tolerance over 15 days of chronic daily dosing. The present results support the hypothesis that allodynia in animal models of CRPS-I and neuropathic pain is effectively relieved by topical combinations of α2A or NO donors with PDE or PA inhibitors. This suggests that topical treatments aimed at improving microvascular function may reduce allodynia in patients with CRPS-I and neuropathic pain.

Perspective

This article presents the synergistic anti-allodynic effects of combinations of α2A or NO donors with PDE or PA inhibitors in animal models of CRPS-I and neuropathic pain. The data suggest effective clinical treatment of chronic neuropathic pain may be achieved by therapies that alleviate microvascular dysfunction in affected areas.

Keywords: Nociception, allodynia, analgesia, synergy, endothelial cell dysfunction

Introduction

Over the past several years, we have generated evidence that pain in an animal model of complex regional pain syndrome type I (CRPS-I) depends on local microvascular dysfunction14,56,93. Evidence suggests that in rats with chronic post-ischemia pain (CPIP), and patients with CRPS, ischemic tissue injury leads to the generation of oxygen free radicals and pro-inflammatory cytokines which cause microvascular injury, including arterial vasospasm and capillary slow-flow/no-reflow in the blood vessels of muscle and nerve56,93. Vasospasm (associated with reduced nitric oxide (NO) and increased vasoactive responses to norepinephrine (NE)), and capillary slow-flow/no-reflow (where blood flow to the many capillary beds is compromised), lead to poor muscle oxygenation and the build-up of muscle lactate, all of which contribute to the pain56,93. Thus, CPIP animals have pain, allodynia, vasospasm, poor tissue perfusion, and oxidative stress14,56,93. Evidence suggests that there is also microvascular dysfunction and poor tissue oxygenation in human CRPS limbs51,64,79,87.

It has been known for many years that microvascular dysfunction and resulting oxidative stress contribute to the pain of angina57,85 and peripheral arterial disease8,69. Recent parallel studies by other groups suggest that microvascular dysfunction and the resulting production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species may contribute to neuropathic pain (including chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve2,3,31, painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN)21,24,42,45,48,74 and chemotherapy-induced painful neuropathy (CIPN)20,22,49,50. Therefore, it is expected that treatments aimed at enhancing tissue oxygenation by reducing arterial vasospasm and capillary slow-flow/no-reflow will also relieve allodynia in animal models of nerve constriction, PDN and CIPN.

A predominant mediator controlling regional blood flow is the vasoconstrictive transmitter NE released from sympathetic post-ganglionic neurons, which contracts vascular smooth muscles28,39. A second key mediator is the vasodilatory substance NO that is released from vascular endothelial cells and relaxes vascular smooth muscles72,89. Thus, pharmacological agents that reduce NE release or binding, or agents that increase NO, are used to alleviate conditions with poor blood flow17,41, including microvascular dysfunction. Various isoforms of phosphodiesterase enzymes (PDEs) also regulate blood flow92. Thus, PDE4,7 and 8 hydrolyse cAMP, PDE5,6 and 9 hydrolyse cGMP, and PDE1,2,3,10 and 11 hydrolyse both cAMP and cGMP78. While PDE inhibitors that reduce cGMP hydrolysis enhance blood flow59, PDE inhibitors that reduce cAMP hydrolysis also reduce platelet aggregation38, decrease blood viscosity44, and increase the flexibility of red blood cells44, all of which relieve microvascular dysfunction. Thus, PDE inhibitors have been developed for conditions such as peripheral arterial disease (PAD)77 and intermittent claudication44, where micovascular injury leads to capillary slow flow/no reflow and reduced tissue oxygenation. Pentoxifylline is a PDE4 inhibitor commonly used to treated these ischemic disorders44,77. A major metabolite of pentoxifylline, lisofylline shares many of the actions of its prodrug60,61,90, but also inhibits the conversion of lysophophatidic acid to phosphatidic acid (PA), a pathway critical to the production of various cytokines76.

Although α2A receptor agonists10,18,58 and NO donors1,33,63 have been used topically to alleviate chronic pain, PDE and PA inhibitors have not been previously used topically to alleviate pain. Furthermore, these agents have neither been combined systemically, nor combined in topical preparations for the treatment of chronic pain. However, α2A receptor agonists, NO donors and PDE inhibitors have been used systemically in patients or preclinical animal models to treat pain associated with angina13,43,66, PAD19,52,82, CRPS18,40,63,74, neuropathic pain32,53,60 and PDN16,24,48,84 indicating their usefulness in these syndromes. PA inhibitors have not been used to treat chronic pain, but should be equally or more effective than PDE inhibitors since they have anti-oxidant7,34, anti-cytokine68,76, anti-chemotaxic70,91, immunosuppressant15,23, and mitochondrial protective12 effects, in addition to the vasodilator61, anti-ischemic90 and anti-platelet aggregation62 effects they share with PDE inhibitors.

In the present study, we have tested the hypothesis that agents aimed at increasing tissue oxygenation by increasing blood flow and reducing microvascular dysfunction (α2A receptor agonists or NO donors, combined with PDE or PA inhibitors) can be used topically, either alone or in combination, on the hind paw to reduce allodynia in animal models of CRPS-I, nerve constriction, PDN and CIPN.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Long Evans or Sprague Dawley rats (225–250 g, Charles River, St. Constant, QC) arrived at least 7 days before experiments. Methods were approved by the animal care committee of McGill University, and conformed to ethical guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and the International Association for the Study of Pain.

Drugs

Drugs used included linsidomine (nitric oxide donor) (Tocris, Ellisville, MO), lisofylline (phosphatidic acid inhibitor) (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan), apraclonidine (α2 adrenergic receptor agonist), clonidine (α2 adrenergic receptor agonist), pentoxifylline (phosphodiesterase inhibitor) and S-nitroso-N-acetyl- penicillamine (SNAP) (nitric oxide donor) (all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Drug formulations

Ointment-type formulations containing the above-mentioned drugs were formulated using a composite, water-soluble polyethylene glycol base system consisting of carbowax (PEG 3350) and PEG 400 (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in the ratio of 60:40 respectively. All topical formulations were water-miscible/soluble ointments used to reduce irritation at the point of application and to ensure uniform and fast absorption. In the experiments with CIPN rats, 0.5% low molecular weight dextran sulfate was added as a tissue penetration enhancer. Briefly, the required amounts of the active ingredients were first weighed out and then added to the already molten base in decreasing order of their melting points, and stirred well. After uniform melting, the formulation was brought to room temperature to ensure proper solidification. A standard amount of 150 mg (mean ± SEM = 150.88 ± 2.7 mg) of the ointment was rubbed into the skin of the plantar and dorsal rat hind paw for 15 seconds using gloved finger tips, and the animals were immediately transferred to their respective cages. No rats were ever observed licking their hind paws after ointment application.

Chronic post-ischemia pain (CPIP)

Chronic post-ischemia pain (CPIP) was generated following prolonged hind paw ischemia and reperfusion, as previously described14. Briefly, male Long Evans rats were anesthetized over a 3 h period with a bolus (55 mg/kg, i.p.) followed by chronic i.p. infusion (0.15 ml/h) of sodium pentobarbital (Ceva Santé Animale, Libourne, France) for 2 h. After induction of anesthesia, a Nitrile 70 Durometer O-ring (O-rings West, Seattle, WA) with 5.5 mm internal diameter was placed around the rat’s left hind limb proximal to the ankle joint. The tight-fitting O-ring produces a complete blockade of arterial blood flow as measured using laser Doppler flowmetry56. The ring was then left in place for 3 h, and the rats recovered from anesthesia 30–60 min following reperfusion. Rats were tested between 2 and 14 days post-IR injury.

Chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve

Unilateral mononeuropathy was produced in rats using CCI of the sciatic nerve, as described by Bennett and Xie6. Briefly, male Long Evans rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (55 mg/kg, i.p.), the common left sciatic nerve was exposed by skin incision and blunt dissection just above the trifurcation point, and four loose ligatures were then made with 4-0 chromic gut suture around the nerve, with about 1 mm spacing in between. The wound was then closed in layers with 3-0 silk thread and wound clips. The animals were then transferred to their home cages and left to recover. Rats were tested between 7 and 14 days post-CCI.

Diabetic neuropathy

Diabetic neuropathy was induced in male Sprague Dawley rats by a single injection of streptozotocin (STZ, 60 mg/kg, i.p.), and the rats were given 10% sucrose solution in their drinking water for 48 h after the injection. Blood samples from the tail vein were taken at 72 h and at one and two weeks following STZ injection, and only rats with blood glucose levels above 300 mg/dl (i.e., diabetic rats) were used. Rats were tested between days 14 and 21 after STZ injection.

Chemotherapy-induced painful neuropathy

Following habituation to the behavioural testing environment, male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–300 g) were injected intraperitoneally with the chemotherapeutic agent paclitaxel (Taxol®, Bristol–Myers–Squibb). Paclitaxel (2 mg/kg), prepared as a solution of 6 mg/ml in Cremophor EL vehicle diluted with saline was injected i.p. on four alternate days (days 0, 2, 4 and 6) as previously described87. Rats were tested daily between days 28 and 43 post-paclitaxel treatment.

Mechanical sensitivity testing

The plantar surface of the ipsilateral hind paw was tested for mechanical allodynia (paw-withdrawal thresholds, PWTs) in CPIP and CCI rats, as well as bilaterally in PDN rats. Nylon monofilaments (von Frey hairs) were applied in either ascending (after negative response) or descending (after positive response) force as necessary to determine the filament closest to the threshold of response. Each filament was applied for 10 s or until a flexion reflex occurred. The minimum stimulus intensity was 1 g and the maximum was 15 g. Based on the response pattern, and the force of the final filament (5th stimulus after first direction change), the 50% threshold (grams) was calculated as (10[Xf+kδ])/10000 where Xf= filament number of the final von Frey hair used, k=value for the pattern of positive/negative responses and δ=mean difference in log unit between stimuli (here, δ=0.220, for more details see Chaplan et al. 11). All behavioural testing was performed with the experimenter unaware of the treatment condition.

Pharmacological treatments

Chronic post-ischemia pain

The topical formulations containing an NO donor, α2A receptor agonist or a PDE or PA inhibitor were tested for their anti-allodynic effects, either singly, or in combination with each other, at concentrations selected from the published literature for use as topical agents. Accordingly, the rats received 150 mg of the respective ointment with the first half on the plantar aspect of their hind paws followed by the second half applied on the dorsal surface; in both cases by uniform gentle application using gloved fingers. The rats were monitored for several minutes after application to make sure they did not lick their paws. In the single drug pharmacological trials, clonidine was tested at 0.007, 0.015, 0.03 and 0.06% W/W (n = 6); apraclonidine at 0.005, 0.01, 0.02 and 0.04% W/W (n = 6); linsidomine at 0.2, 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6% W/W (n = 8); SNAP at 0.063, 0.125, 0.25 and 0.5% W/W (n = 7); pentoxifylline at 0.6, 1.2, 2.5 and 5% W/W (n = 6); and lisofylline at 0.063, 0.09, 0.125 and 0.25% W/W (n = 10).

In separate groups of CPIP rats, formulations containing pentoxifylline or lisofylline were tested in combinations with non-effective concentrations of clonidine, linsidomine, or SNAP. Accordingly, the formulations tested in the combination trials included clonidine (0.0075% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.3, 0.6 and 1.2% W/W) (n = 9), linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + lisofylline (0.0313, 0.0625 and 0.0932% W/W) (n = 10), and SNAP (0.0625% W/W) + lisofylline (0.008, 0.015, 0.033 and 0.063% W/W) (n = 7). A third cohort of rats was used to confirm the local action of the tested formulations. For this study, the formulations were applied to the contralateral paw and the ipsilateral paw was tested for anti-allodynic effects. The most effective drug combinations were tested in this manner. Accordingly, the combinations included clonidine (0.0075% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.6% W/W) (n = 9), linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + lisofylline (0.09% W/W) (n = 10) and SNAP (0.0625% W/W) + lisofylline (0.0625% W/W) (n = 7). In addition, vehicle (ointment base) application to the ipsilateral paw was also evaluated. All of the rats underwent initial baseline PWT assessment before application of the ointment followed by testing at 45 min post-application.

Nerve Constriction

In CCI rats, effective drug combinations (previously determined from the CPIP experiments described above) or vehicle ointment were tested for their anti-allodynic effects following either ipsilateral or contralateral hind paw application. The combinations included clonidine (0.0075% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.6% W/W) (n = 7), apraclonidine (0.005% W/W) + lisofylline (0.03125% W/W) (n = 7), linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.3% W/W) (n = 7) and SNAP (0.0625% W/W) + lisofylline (0.0625% W/W) (n = 7). All of the rats underwent initial baseline PWT assessment before application of the ointment followed by testing at 45 min post-application.

Painful diabetic neuropathy

Three drug combinations were tested in PDN rats and age-matched control rats, including apraclonidine (0.0075% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.6% W/W) (n = 4); apraclonidine (0.005% W/W) + lisofylline (0.0315% W/W) (n = 5); or linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + lisofylline (0.075% W/W) (n = 5) (separate groups). All of the rats underwent an initial pre-drug PWT assessment of both hind paws before application of the ointment to one hind paw followed by mechanical allodynia testing of both hind paws from 20–90 min post-application.

Chemotherapy-induced painful neuropathy

Two drug combinations were tested in CIPN rats, including apraclonidine (0.005% W/W) + lisofylline (0.03% W/W) (n = 10), or linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.4% W/W) (n = 10) (separate groups). All of the rats underwent an initial pre-drug PWT assessment of both hind paws before application of the topical combination to one hind paw and vehicle ointment base to the other hind paw daily for 15 days, followed by mechanical allodynia testing of both hind paws 1, 3, 6 and 24 h post-application on day 1 of treatment, or 3 h post-application on days 4, 8, 11 and 15 of treatment.

Data analysis

PWTs were averaged by group and treatment time and subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using repeated measures. Pair-wise comparisons of group means were performed using Fisher’s LSD tests after the observation of significant effects of drug treatment.

Shifts in drug anti-allodynic potency obtained by the use of combination treatments were illustrated by first calculating the difference between pre- and post-drug measures for each rat, then averaging these differences by treatment group. Mean differences were then plotted on a semilog scale of the amount of drug used per application. For each drug condition tested, unweighted linear regressions of ΔPWT versus log dose were calculated for individual subjects, and the regression x-intercept estimates were then compared between drug alone and drug combination groups by one-way ANOVA in order to assess shifts in the dose-response profiles.

Results

Effects of topical treatments on mechanical allodynia in CPIP rats

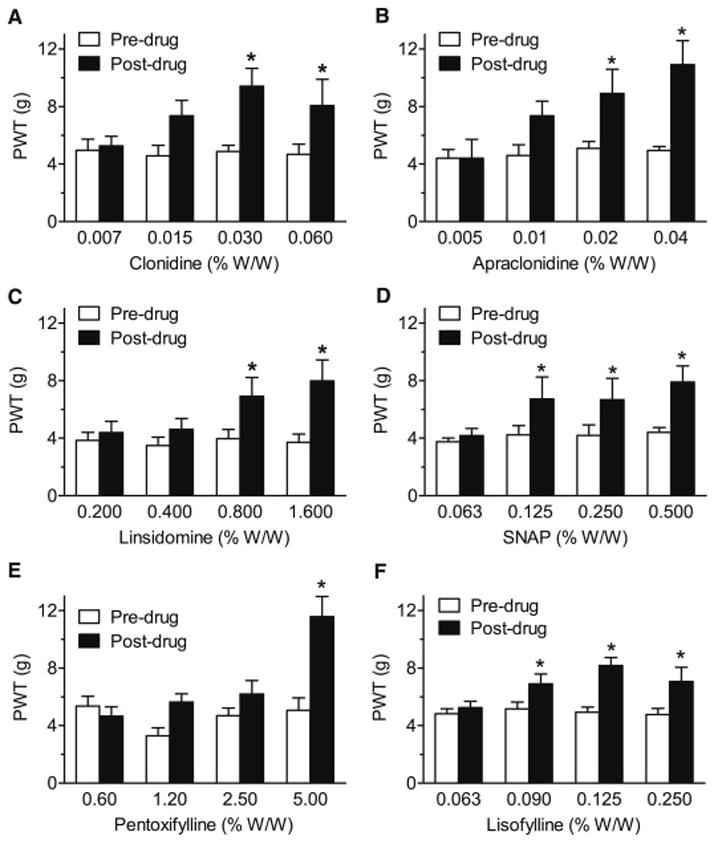

In the single drug trials, hind paw topical application produced significant, dose-related anti-allodynic effects in CPIP rats for each of the six agents tested (Fig. 1A–F). Clonidine significantly elevated PWTs above pre-drug levels at 0.03 and 0.06% W/W (P = 0.0104 and P = 0.0451, respectively); apraclonidine at 0.02 and 0.04% W/W (P = 0.0175 and P = 0.0008, respectively); linsidomine at 0.8 and 1.6% W/W (P = 0.0054 and P = 0.0002, respectively); SNAP at 0.125, 0.25 and 0.5% W/W (P = 0.0117, P = 0.0123 and P = 0.0009, respectively); pentoxifylline at 5% W/W (P = 0.0003); and lisofylline at 0.09, 0.125 and 0.25% W/W (P = 0.0128, P = 0.0001 and P = 0.0016, respectively). Application of ointment base alone (vehicle) was without effect on ipsilateral PWTs for every agent tested (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Assessment of the effects of single topical agents clonidine, apraclonidine, linsidomine, SNAP, pentoxifylline and lisofylline (A–F) on paw-withdrawal thresholds (PWTs) to von Frey stimulation of the ipsilateral (injured) hind paw in day 2–14 CPIP rats. Singly, each agent produces dose-related anti-allodynic effects, with higher concentrations producing significant elevations of PWTs and the lowest concentrations failing to produce significant anti-allodynic effects. *P < 0.05 between pre- and post-drug mean PWTs.

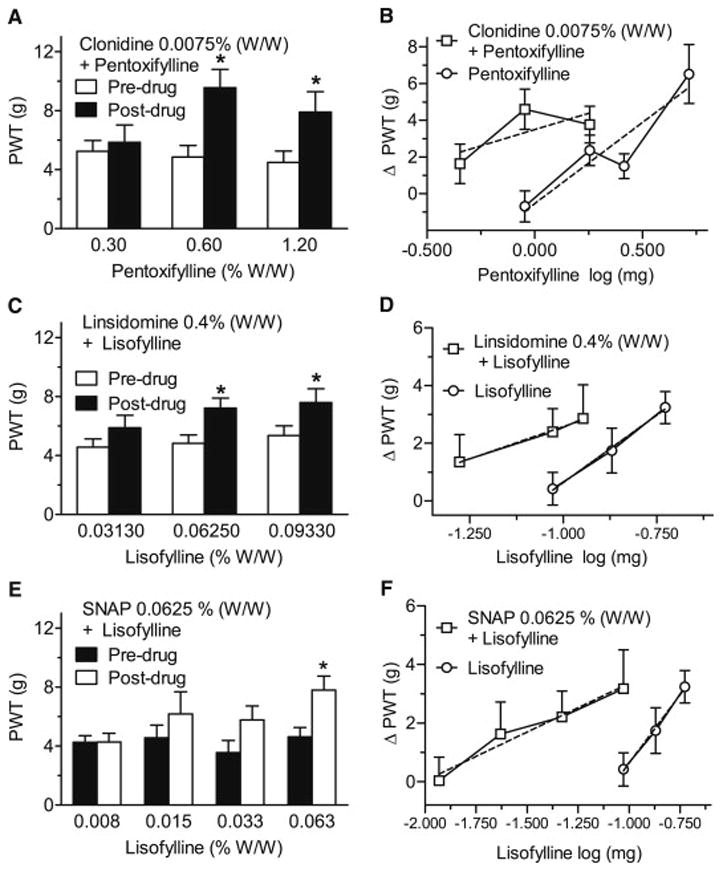

Combination of α2A receptor agonists or NO donors with either PDE or PA inhibitors dramatically reduced the doses required to relieve allodynia in CPIP rats. Thus, the combination of a sub-active dose of clonidine (0.0075% W/W) with pentoxifylline increased PWTs at 0.6 and 1.2% W/W of pentoxifylline (P = 0.0001 and P = 0.0009, respectively; Fig. 2A), and the pentoxifylline log dose-response x-intercept shifted from 1.572 ± 1.114 mg to 0.2919 ± 0.178 mg (P = 0.0418; Fig. 2B). Combining a sub-active dose of linsidomine (0.4% W/W) with lisofylline increased PWTs over pre-drug values at 0.0625 and 0.0932% W/W of lisofylline (P = 0.0227 and P = 0.0315, respectively; Fig. 2C), and shifted the x-intercept value of the log dose-response curve for lisofylline from a dose of 0.093 ± 0.011 mg to 0.059 ± 0.010 mg (P = 0.0406; Fig. 2D). When administered with a sub-active dose of SNAP (0.0625% W/W), lisofylline was anti-allodynic at 0.063% W/W (P = 0.0096; Fig. 2E), and the value of the x-intercept of the log dose-response curve for lisofylline shifted from 0.077 ± 0.013 mg to 0.012 ± 0.004 mg (P = 0.0010; Fig. 2F). Note that sub-active doses of the α2A receptor agonists or NO donors were selected from the results of single agents presented in Fig. 1.

Fig 2.

Assessment of the effects of topical combinations of pentoxifylline or lisofylline given with either vehicle or ineffective concentrations of clonidine (A,B), linsidomine (C,D) and SNAP (E,F) on paw-withdrawal thresholds (PWTs; A,C,E) and anti-allodynic (ΔPWT) pentoxifylline or lisofylline dose-response curves alone or in combination with clonidine, linsidomine or SNAP (B,D,F) in the ipsilateral (injured) hind paw of day 2–14 CPIP rats. The combinations significantly increased PWTs at concentrations much lower than in Fig. 1, and shifted the anti-allodynic dose-response curve for lisofylline between 2 and 10 fold to the left. *P < 0.05 between pre- and post-drug mean PWTs.

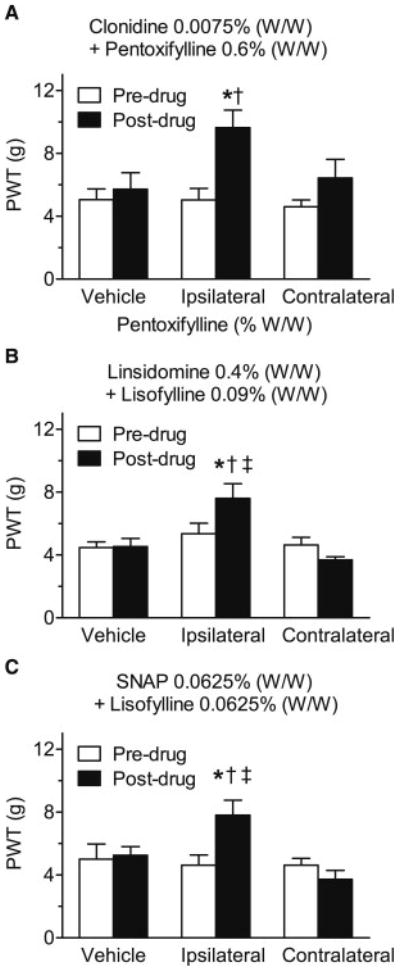

Application of the most effective drug combinations to the contralateral paw was without effect on the PWTs measured from the injured paw, when compared to pre-drug values. PWTs were thus significantly lower after contralateral paw treatment than after ipsilateral ointment application to the injured paw following treatment with clonidine (0.0075% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.6% W/W) (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3A), linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + lisofylline (0.09% W/W) (P = 0.0029; Fig. 3B) or SNAP (0.0625% W/W) + lisofylline (0.0625% W/W) (P = 0.0001; Fig. 3C), In addition, for all combinations tested, application of vehicle (ointment base) to the ipsilateral paw was without effect on the PWTs measured from the injured paw, when compared to pre-drug values.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the effects of topical vehicle application, or ipsilateral versus contralateral application of the most effective concentrations of the topical combinations used in Figs. 2 (clonidine + pentoxifylline (A), linsidomine + lisofylline (B) and SNAP + lisofylline (C)) on paw-withdrawal thresholds (PWTs) in the ipsilateral (injured) hind paw of day 2–14 CPIP rats. In all trials, topical application of vehicle failed to significantly alter PWTs. Furthermore, although each combination significantly increased PWTs when applied to ipsilateral hind paw, they were all ineffective when applied to the contralateral hind paw. *P < 0.05 between pre- and post-drug mean PWTs; †P < 0.05 from post-drug vehicle; ‡P < 0.05 from post-drug contralateral PWT.

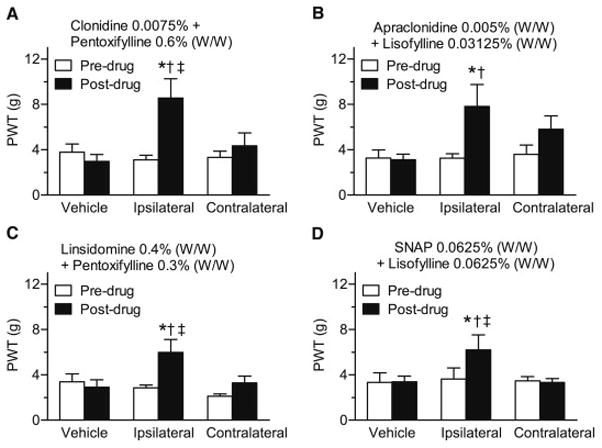

Effects of topical treatments on mechanical allodynia in rats with CCI, PDN or CIPN

CCI rats developed unilateral allodynia in the hind paw of the injured hind limb. Low concentration combinations of four of the formulations reduced allodynia in CCI rats. These effects were due to a local effect, as the effects were produced by ipsilateral, but not contralateral treatment. Thus, application of clonidine (0.0075% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.6% W/W) (Fig. 4A), apraclonidine (0.005% W/W) + lisofylline (0.03125% W/W) (Fig. 4B), linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.3% W/W) (Fig. 4C) or SNAP (0.0625% W/W) + lisofylline (0.0625% W/W) (Fig. 4D) to the injured paw increased PWTs above pre-drug values (P = 0.0024, P = 0.0008, P = 0.0111, and P = 0.0009, respectively), and increased PWTs above values measured after ipsilateral vehicle application (P = 0.0024, P = 0.0001, P = 0.0018, and P = 0.0005, respectively). Application of the same combinations to the contralateral hind paw were without effect when compared to pre-drug values, and PWTs obtained after ipsilateral application were higher than those measured after contralateral application for clonidine (0.0075% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.6% W/W) (P = 0.0013), linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.3% W/W) (P =0.0018) and SNAP (0.0625% W/W) + lisofylline (0.0625% W/W) (P = 0.0004) (Fig. 4A–D).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the effects of topical vehicle administration, or ipsilateral versus contralateral administration of the effective concentrations of four topical combinations (clonidine + pentoxifylline (A), apraclonidine + lisofylline (B) linsidomine + pentoxifylline (C) and SNAP + lisofylline (C)), on paw-withdrawal thresholds (PWTs) in the ipsilateral (injured) hind paw of day 7–14 CCI rats. In all trials, topical application of vehicle failed to significantly alter PWTs. Furthermore, although each combination significantly increased PWTs when applied to ipsilateral hind paw, they were all ineffective when applied to the contralateral hind paw. *P < 0.05 between pre- and post-drug mean PWTs. †P < 0.05 from post-drug vehicle. ‡P < 0.05 from post-drug contralateral PWT.

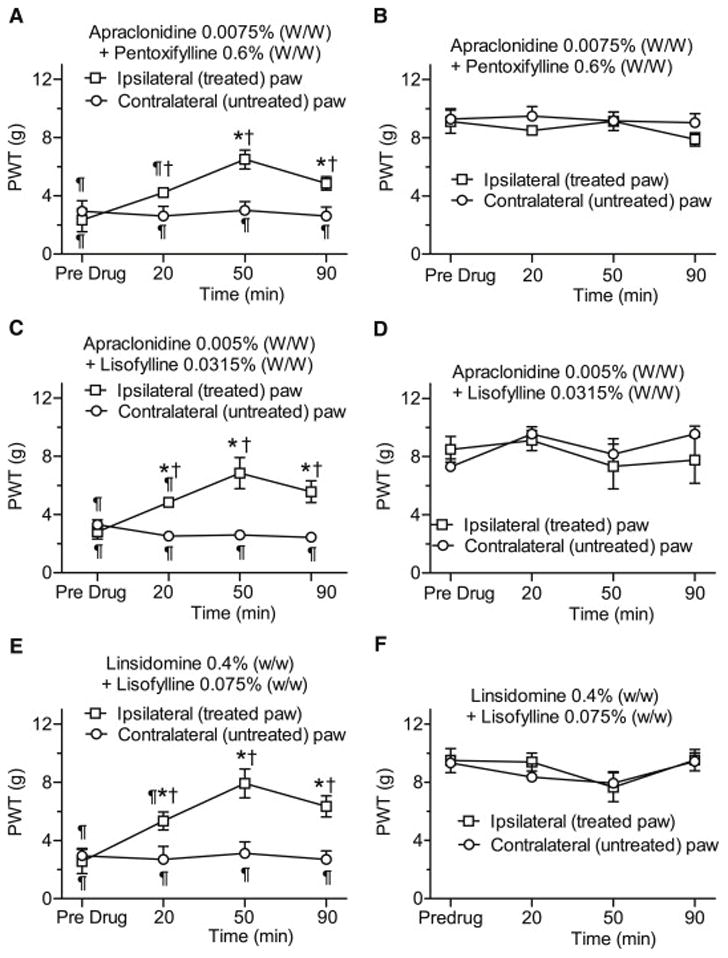

PDN rats developed symmetrical bilateral allodynia in both hind paws. Three low dose combinations reduced mechanical allodynia in the treated (ipsilateral), but not untreated (contralateral), hind paw of PDN rats, without altering paw-withdrawal thresholds of age-matched control rats. Combination of apraclonidine (0.0075% W/W) and pentoxifylline (0.6% W/W), increased diabetic PWTs above pre-drug values when measured at 20, 50 and 90 min following drug application (P = 0.0184, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0027, respectively). PWTs following ointment application were higher than PWTs obtained from the untreated hind paw of diabetic animals at 20, 50 and 90 min (P = 0.0057, P = 0.0012 and P = 0.0063, respectively) (Fig. 5A, B). A combination of apraclonidine (0.005% W/W) + lisofylline (0.0315% W/W) increased PWTs above pre-drug values when measured at 20, 50 and 90 min following drug application (P = 0.0167, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0023, respectively, Fig. 5C, D), also producing higher PWTs compared to untreated diabetic PWT values at 20, 50 and 90 min post application (P = 0.0076, P < 0.0001 and P < 0.0001, respectively). Comparable results were obtained with linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + lisofylline (0.075% W/W) which similarly increased diabetic PWTs above pre-drug values when measured at 20, 50 and 90 min following drug application (P = 0.0011, P< 0.0001 and P < 0.0001, respectively), and above untreated diabetic PWT values at 20, 50 and 90 min post application (P = 0.0015, P < 0.0001 and P < 0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 5E, F).

Fig. 5.

Time course of the anti-allodynic effects of low concentration topical combinations of apraclonidine + pentoxifylline (A,B), apraclonidine + lisofylline (C,D) and linsidomine + lisofylline (E,F) on paw-withdrawal thresholds (PWTs) both ipsilateral and contralateral to the topical treatments in rats with streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic neuropathy (A,C,E) or in age-matched vehicle-injected controls (B,D,F). Each topical combination significantly increased PWTs of the ipsilateral (treated), but not the contralateral (untreated) hind paws of rats with diabetic neuropathy. Conversely, the topical combinations had no effects on PWTs in the ipsilateral or contralateral hind paws in age-matched (STZ vehicle-injected) control rats. *P < 0.05 between pre- and post-drug mean PWTs within a group. †P < 0.05 between ipsi- and contralateral PWTs, and ¶P < 0.05 between diabetic and control PWTs at each time point.

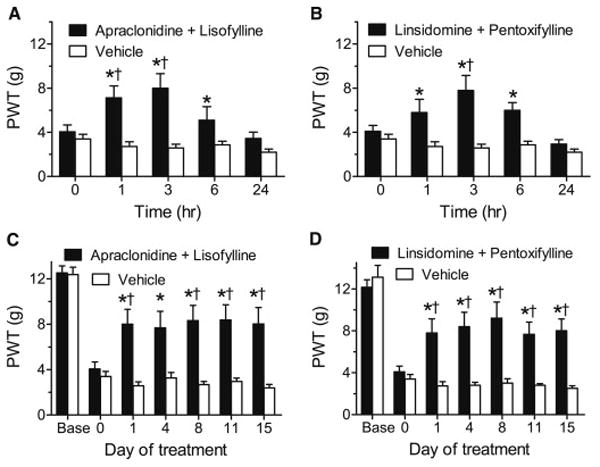

CIPN rats developed symmetrical bilateral allodynia in both hind paws. Two low dose combinations acutely reduced mechanical allodynia in the treated (ipsilateral), while vehicle treatment had no effect in the (contralateral), hind paw of CIPN rats. Thus, on the first day of treatment, apraclonidine (0.005% W/W) + lisofylline (0.03% W/W) increased PWTs above vehicle values when measured at 1, 3 and 6 h following drug application (P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0243, respectively, Fig. 6A). The treatment also elevated PWTs above pre-drug baseline PWTs at 1 and 3 h post-application (P = 0.0209, P = 0.0016, respectively, Fig. 6A). A combination of linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.4% W/W) similarly increased PWTs above vehicle values on the first day of treatment when measured at 1, 3 and 6 h following drug application (P = 0.0001, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0006, respectively, Fig 6B). The treatment also elevated PWTs above pre-drug baseline PWTs at 3 h post-application (P = 0.0017, Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Anti-allodynic effects over an acute time course (A,B) and chronic daily dosing (C,D) of topical combinations of apraclondine + lisofylline (A,C) or linsidomine + pentoxifylline (B,D) in rats with CIPN. Each combination produced acute anti-allodynic effects lasting 6 h after the first topical application (*P < 0.05 compared to vehicle, †P < 0.05 compared to pre-drug baseline (0)), and produced significant anti-allodynia on each test day during chronic daily dosing for 15 days (*P < 0.05 compared to vehicle, †P < 0.05 compared to pre-drug baseline (0)).

Chronic daily treatment with apraclonidine (0.005% W/W) + lisofylline (0.03% W/W) also significantly elevated PWTs compared to vehicle treatment or to the pre-drug baseline (day 0), with significant differences between drug and vehicle on days 1, 4, 8, 11 and 15 (P = 0.00014, P = 0.0015, P = 0.00008, P = 0.00014, P = 0.00008, respectively), and between drug and baseline on days 1, 8, 11 and 15 (P = 0.0399, P = 0.0212, P = 0.0190, P = 0.0384, respectively, Fig. 6C). Chronic daily treatment with linsidomine (0.4% W/W) + pentoxifylline (0.4% W/W) also significantly elevated PWTs compared to vehicle treatment or to the pre-drug baseline (day 0), with significant differences between drug and vehicle on days 1, 4, 8, 11 and 15 (P = 0.0002, P< 0.0001, P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0001, respectively) and between drug and baseline on days 1, 4, 8, 11 and 15 (P = 0.0138, P = 0.0170, P = 0.0003, P = 0.0186, P = 0.0075, respectively, Fig. 6D).

Discussion

Most pharmacological therapies for CRPS-I and neuropathic pain include oral systemic treatments (NSAIDs, opioids, NSAIDs, pregabalin, etc.) that cause significant side-effects, which can include nausea, confusion, dizziness, stomach bleeding, constipation and dependence25,65,71. These side-effects hinder the ability to use therapeutically effective dose levels and reduce patient compliance55. Use of topical agents in low doses should avoid these side-effects. With topical treatment, drug concentrations are higher at local target sites, but plasma concentrations are typically less than 10% of the same dose given orally36. Furthermore, topical treatment avoids gastrointestinal (GI) tract and hepatic first pass metabolism, and allows more drug to be active locally with less potential liver or GI toxicity9.

In CPIP rats, the topical combinations we have tested produce similar effects as 5 to 55 times higher systemic doses of the individual agents alone, and have efficacy greater than systemic acetaminophen, ibuprofen, dexamethasone or amitriptyline67. They also produce maximal effects in both animal models of CRPS and neuropathic pain that are equivalent to those produced by systemic doses of morphine and pregabalin 54,67.

We have previously shown that CPIP rats exhibit both enhanced vasoconstriction or vasospasm in response to close intra-arterial NE administration, as well as having evidence of slow flow/no-reflow, indicated by capillary endothelial cell swelling, poor microvascular perfusion and reduced oxygenation in hind paw muscle56,93. Furthermore, hind paw injection of various vasoconstrictive agents including NE, endothelin-1/2 and vasopressin, as well as the endothelial nitric oxide inhibitor, N5-(1-iminoethyl)-L-ornithine dihydrochloride, produce enhanced painful responses in CPIP rats, likely because these vasoconstrictors exacerbated the poor microvascular perfusion in CPIP hind paws67,93. Indeed, we have shown that the painful responses to hind paw NE injection in CPIP rats are dose-dependently and significantly reduced by systemic administration of either an α2A receptor antagonist or an NO donor93, both of which would increase peripheral vasodilation. We have also recently shown that systemic administration of the PDE4 inhibitor pentoxifylline reduces both allodynia and microvascular (endothelial cell) dysfunction, as measured by post-occlusion reactive hyperemia75. Importantly, post-occlusive reactive hyperemia (dependent on nitric oxide release from microvascular endothelial cells) is significantly reduced in CPIP rats, and this endothelial dysfunction is alleviated following systemic pentoxifylline administration75. These various signs of microvascular dysfunction and vasospasm and poor perfusion-related pain responses suggest that pain in CPIP rats, and possibly also CRPS, would benefit from topical treatments aimed at increasing local blood flow and reducing microvascular dysfunction.

It has previously been shown that CCI rats, and rats with sciatic nerve lesions, exhibit enhanced xanthine oxidase in sciatic nerve47 and reduced vasodilatory responses to either the neuropeptides substance P and CGRP or the nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside applied at the base of a skin blister on the foot pad2,3,47. These findings indicate that nerve injury can induce endoneurial oxidative stress and diminished vascular reactivity in hind paw skin. These authors also showed that systemic treatment with antioxidants improved the skin vascular reactivity in CCI rats, as well as reducing concomitant thermal hyperalgesia47. Sciatic nerve lesion has also been shown to produce microvascular disturbances in rats, including capillary stasis (decreased blood flow) and increased venular permeability31. Importantly, both the microvascular disturbances and signs of deafferentation pain in these rats were reduced by prophylactic systemic administration of clonidine53 or pentoxifylline32. Once again, the reduced blood flow and microvascular dysfunction evidenced in rats with nerve lesions suggests that our topical treatments may be useful for neuropathic pain.

It has been well established that STZ diabetic rats have evidence of microvascular dysfunction, including reduced blood flow in nerve42,48 and skin45. Importantly, the reduced blood flow42,45,48, and associated tactile allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia42, are alleviated by systemic treatment with antioxidants, PDE inhibitors or rheologic agents that reduce blood clotting. STZ rats also exhibit increased platelet aggregation24. and thickening of capillary walls and basement membrane of endoneurial blood vessels84. Importantly, both platelet aggregation24 and associated mechanical hyperalgesia16, are alleviated by the α2A receptor agonist clonidine, while endoneurial capillary abnormalities are reduced following systemic administration of the PDE inhibitor cilostazol84. These findings again suggest that topical treatments that increase blood flow and reduce microvascular dysfunction would be useful for treating PDN.

Growing evidence also suggests that there is microvascular dysfunction in rats with CIPN. Endoneurial blood flow is markedly reduced in association with nerve degeneration in rats treated with the chemotherapeutic agents cisplatin49 or taxol50. Importantly, endoneurial blood flow is increased and nerve degeneration is reduced in CIPN rats by increasing the level of vascular endothelial growth factor, which promotes angiogenesis49,50. Recent evidence also shows that mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in CIPN rats can be alleviated by systemic treatment with agents that reduce reactive oxygen20 and nitrogen22 species, both of which are elevated in association with microvascular dysfunction. Clinically, in addition to CIPN it has often been reported that chemotherapy induces Raynaud’s phenomenon4,5,86, a condition where patients develop poor capillary blood flow in the fingers and toes. Evidence indicates that this complication of chemotherapy can be treated with spinal cord stimulation86 (which increases peripheral blood flow) or with PDE5 inhibitors, which were shown to increase blood flow4. The findings of microvasular abnormalities associated with CIPN again suggest that topical treatments that increase blood flow and reduce microvascular dysfunction would be therapeutically useful for CIPN.

The concentrations of topical agents used in our combinations are much lower than the recommended concentrations used for neuropathic/ischemic pain or other clinical uses, typically clonidine (0.1–0.3%), apraclonidine (0.5–1.0%), linsidomine (2%), pentoxifylline (5–15%), and lisofylline (0.5–5%). Thus, the combinations of these agents used resulted in significant anti-allodynic effects at topical concentrations that are 5 to 640 times lower than those used typically for the single agents. The finding that these combinations produced effects when given to the hind paw ipsilateral, but not contralateral, to injury in both CPIP and CCI rats, and had no effects on allodynia in the untreated hind paw of PDN and CIPN rats, suggests that the agents produce their anti-allodynic effects locally. Thus, by using combinations that greatly potentiate anti-allodynic effects at a local site, it is possible to use even lower topical drug concentrations that are less likely to produce adverse side-effects. Also, combinations that employ apraclonidine, which does not cross the blood brain barrier83, would further reduce the potential systemic side-effects of α2A receptor agonists, which lower blood pressure largely by actions at α2A and/or imidazoline receptors in the brain stem88. Furthermore, although the half-life of some of the agents when given systemically is fairly short (e.g., pentoxifylline: 0.84 h; linsidomine: 1.0 h)80,81, slow skin penetration after topical administration is known to produce a prolongation of drug half-life by 5–10 fold26. This likely explains our finding that topical treatment with combinations including these agents produced anti-allodynic effects lasting up to 6 hours in CIPN rats, and why the combinations were effective when tested 3 hours post-application during chronic dosing trials in CIPN rats. Finally, the ability of these combinations to produce equivalent anti-allodynic effects each testing day during chronic dosing, indicates that these agents do not produce tolerance, at least over the 15 days of treatment in CIPN rats.

Our conclusion must be tempered by the known non-specific effects of the agents we used. For example, clonidine acts at imidazoline receptors as well as α2A receptors88, and pentoxiphylline is a non-specific PDE inhibitor that produces anti-inflammatory effects by interacting with various biological systems. Furthermore, although lisofylline is a phosphatidic acid inhibitor, it is a metabolite of pentoxifylline62,76, and shares many of pentoxifylline’s PDE inhibitor activities, including inhibition of various cytokines76. However, topical administered clonidine is unlikely to have significant effects at brainstem imidazoline receptors, especially at the low concentrations we have used. Also, clonidine’s anti-allodynic effects were mimicked by apraclondine, which does not cross the blood brain barrier83. In addition, the many of the various anti-inflammatory activities of pentoxifylline and lisofylline are linked with their vascular effects7,62,76,91, as microvascular function is key to various processes involved in the inflammatory response, including plasma extravasation, platelet aggregration, leukocyte migration, cytokine activation, among others.

In conclusion, combining topical agents designed to enhance local blood flow and reduce microvascular dysfunction, produce significant anti-allodynic effects in animal models of CRPS-I, neuropathic pain due to nerve constriction, PDN and CIPN. Furthermore, the dramatic potentiation of anti-allodynic effects of PDE and PA inhibitors when combined with α2A receptor agonists or NO donors, should reduce the potential systemic side-effects of these low concentration topical treatments. Acute time course and chronic daily dosing trial in CIPN rats also indicate that these combinations produce long-lasting effects without exhibiting drug tolerance.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Louise and Alan Edwards Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-143406), and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (194525-09) to TJC.

Footnotes

Disclosures

JVR, AL and TJC are listed as inventors on a patent based on some of the results presented here and could potentially receive compensation from commercialization of the IP. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

J. Vaigunda Ragavendran, Alan Edwards Centre for Research on Pain, Dept. of Anesthesia, McGill University.

André Laferrière, Alan Edwards Centre for Research on Pain, Dept. of Anesthesia, McGill University.

Wen Hua Xiao, Alan Edwards Centre for Research on Pain, Dept. of Anesthesia and Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University

Gary J. Bennett, Alan Edwards Centre for Research on Pain, Dept. of Anesthesia and Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University

Satyanarayana S.V. Padi, Alan Edwards Centre for Research on Pain, Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University

Ji Zhang, Alan Edwards Centre for Research on Pain, Dept. of Neurology and Neurosurgery and Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University

Terence J. Coderre, Alan Edwards Centre for Research on Pain, Depts. of Anesthesia, Neurology & Neurosurgery, and Psychology, McGill University and McGill University Health Centre Research Institute

References

- 1.Agrawal RP, Choudhary R, Sharma P, Sharma S, Beniwal R, Kaswan K, Kochar DK. Glyceryl trinitrate spray in the management of painful diabetic neuropathy: a randomized double blind placebo controlled cross-over study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77:161–177. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basile S, Khalil Z, Helme RD. Skin vascular reactivity to the neuropeptide substance P in rats with peripheral mononeuropathy. Pain. 1993;52:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90134-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassirat M, Helme RD, Khalil Z. Effect of chronic sciatic nerve lesion on the neurogenic inflammatory response in intact and acutely injured denervated rat skin. Inflamm Res. 1996;45:380–385. doi: 10.1007/BF02252932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumhaekel M, Scheffler P, Boehm M. Use of tadalafil in a patient with a secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon not responding to sildenafil. Microvasc Res. 2005;69(3):178–179. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger CC, Bokemeyer C, Schneider M, Kuczyk MA, Schmoll HJ. Secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon and other late vascular complications following chemotherapy for testicular cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:2229–2238. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33:87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhat VB, Madyastha KM. Antioxidant and radical scavenging properties of 8-oxo derivatives of xanthine drugs pentoxifylline and lisofylline. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:1212–1217. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Böger RH, Bode-Böger SM. Endothelial dysfunction in peripheral arterial occlusive disease: from basic research to clinical use. Vasa. 1997;26:180–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown MB. Dermal and Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems: Current and Future Prospects. Drug Delivery. 2006;13:175–187. doi: 10.1080/10717540500455975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell CM, Kipnes MS, Stouch BC, Brady KL, Kelly M, Schmidt WK, Petersen KL, Rowbotham MC, Campbell JN. Randomized control trial of topical clonidine for treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. Pain. 2012;153:1815–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen M, Yang Z, Wu R, Nadler JL. Lisofylline, a novel antiinflammatory agent, protects pancreatic beta-cells from proinflammatory cytokine damage by promoting mitochondrial metabolism. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2341–2348. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cocco G, Strozzi C, Haeusler G, Chu D, Amrein R, Padovan GC. The therapeutic value of clonidine in patients with coronary heart disease. Eur J Cardiol. 1979;10:221–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coderre TJ, Xanthos DN, Francis L, Bennett GJ. Chronic post-ischemia pain (CPIP): a novel animal model of complex regional pain syndrome-type I (CRPS-I; reflex sympathetic dystrophy) produced by prolonged hind paw ischemia and reperfusion in the rat. Pain. 2004;112:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coon ME, Diegel M, Leshinsky N, Klaus SJ. Selective pharmacologic inhibition of murine and human IL-12-dependent Th1 differentiation and IL-12 signaling. J Immunol. 1999;163:6567–6574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Courteix C, Bardin M, Chantelauze C, Lavarenne J, Eschalier A. Study of the sensitivity of the diabetes-induced pain model in rats to a range of analgesics. Pain. 1994;57:153–160. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cubeddu LX. New alpha 1-adrenergic receptor antagonists for the treatment of hypertension: role of vascular alpha receptors in the control of peripheral resistance. Am Heart J. 1988;116:133–162. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis KD, Treede RD, Raja SN, Meyer RA, Campbell JN. Topical application of clonidine relieves hyperalgesia in patients with sympathetically maintained pain. Pain. 1991;47:309–317. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90221-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dawson DL, Cutler BS, Hiatt WR, Hobson RW, 2nd, Martin JD, Bortey EB, Forbes WP, Strandness DE., Jr A comparison of cilostazol and pentoxifylline for treating intermittent claudication. Am J Med. 2000;109:523–530. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00569-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Cesare Mannelli L, Zanardelli M, Failli P, Ghelardini C. Oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy: oxidative stress as pathological mechanism. Protective effect of silibinin. J Pain. 2012;13:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doupis J, Lyons TE, Wu S, Gnardellis C, Dinh T, Veves A. Microvascular reactivity and inflammatory cytokines in painful and painless peripheral diabetic neuropathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2157–2163. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle T, Chen Z, Muscoli C, Bryant L, Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S, Dagostino C, Ryerse J, Rausaria S, Kamadulski A, Neumann WL, Salvemini D. Targeting the overproduction of peroxynitrite for the prevention and reversal of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6149–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6343-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du C, Cooper JC, Klaus SJ, Sriram S. Amelioration of CR-EAE with lisofylline: effects on mRNA levels of IL-12 and IFN-gamma in the CNS. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;110:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunbar JC, Reinholt L, Henry RL, Mammen E. Platelet aggregation and disaggregation in the streptozotocin induced diabetic rat: the effect of sympathetic inhibition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1990;9:265–272. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(90)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duthie DJ, Nimmo WS. Adverse effects of opioid analgesic drugs. Br J Anaesth. 1987;59:61–77. doi: 10.1093/bja/59.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferry JJ, Shepard JH, Szpunar GJ. Relationship between contact time of applied dose and percutaneous absorption of minoxidil from a topical solution. J Pharm Sci. 1990;79:483–486. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600790605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujita R, Kiguchi N, Ueda H. LPA-mediated demyelination in ex vivo culture of dorsal root. Neurochem Int. 2007;50:351–355. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giessler C, Wangemann T, Silber RE, Dhein S, Brodde OE. Noradrenaline-induced contraction of human saphenous vein and human internal mammary artery: involvement of different alpha-adrenoceptor subtypes. NS Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366:104–109. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0582-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goris RJA. Conditions associated with impaired oxygen extraction. In: Guitierrez G, Vincent JL, editors. Tissue Oxygen Utilization. Springer Verlag; Berlin: 1991. pp. 350–369. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goris RJA. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: model of a severe regional inflammatory response syndrome. World Journal of Surgery. 1998;22:197–202. doi: 10.1007/s002689900369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gorizontova MP, Mironova IV. Microcirculatory changes during the long-term course of deafferentation pain syndrome. Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1993;115:233–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorizontova MP, Mironova IV. The effect of prophylactic administration of pentoxifylline (trental) on development of a neuropathic pain syndrome and microcirculatory disorders caused by it. Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1995;119:485–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groeneweg G, Niehof S, Wesseldijk F, Huygen FJ, Zijlstra FJ. Vasodilative effect of isosorbide dinitrate ointment in complex regional pain syndrome type. 1. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:89–92. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318156db3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guidot DM, Bursten SL, Rice GC, Chaney RB, Singer JW, Repine AJ, Hybertson BM, Repine JE. Modulating phosphatidic acid metabolism decreases oxidative injury in rat lungs. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L957–L966. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.5.L957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heerschap A, den Hollander JA, Reynen H, Goris RJ. Metabolic changes in reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a 31P NMR spectroscopy study. Muscle and Nerve. 1993;16:367–373. doi: 10.1002/mus.880160405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heyneman CA, Lawless-Liday C, Wall GC. Oral versus topical NSAIDs in rheumatic diseases: a comparison. Drugs. 2000;60:555–574. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higa M, Takasu N, Tamanaha T, Nakamura K, Shimabukuro M, Sasara T, Tawata M. Nitroglycerin spray rapidly improves pain in a patient with chronic painful diabetic neuropathy. Diabet Med. 2004;21:1053–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horlington M, Watson PA. Inhibition of 3′5′-cyclic-AMP phosphodiesterase by some platelet aggregation inhibitors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1970;19:955–956. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(70)90262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hrometz SL, Edelmann SE, McCune DF, Olges JR, Hadley RW, Perez DM, Piascik MT. Expression of multiple alpha1-adrenoceptors on vascular smooth muscle: correlation with the regulation of contraction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:452–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyland WT. Treating reflex sympathetic dystrophy with transdermal nitroglycerin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:195. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198901000-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ignarro LJ, Napoli C, Loscalzo J. Nitric oxide donors and cardiovascular agents modulating the bioactivity of nitric oxide: an overview. Circ Res. 2002;90:21–28. doi: 10.1161/hh0102.102330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inkster ME, Cotter MA, Cameron NE. Treatment with the xanthine oxidase inhibitor, allopurinol, improves nerve and vascular function in diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;561:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Insel J, Halle AA, Mirvis DM. Efficacy of pentoxifylline in patients with stable angina pectoris. Angiology. 1988;39:514–519. doi: 10.1177/000331978803900604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacoby D, Mohler ER., 3rd Drug treatment of intermittent claudication. Drugs. 2004;64:1657–1670. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin HY, Lee KA, Song SK, Liu WJ, Choi JH, Song CH, Baek HS, Park TS. Sulodexide prevents peripheral nerve damage in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;674:217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jin SM, Noh CI, Yang SW, Bae EJ, Shin CH, Chung HR, Kim YY, Yun YS. Endothelial dysfunction and microvascular complications in type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:77–82. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khalil Z, Liu T, Helme RD. Free radicals contribute to the reduction in peripheral vascular responses and the maintenance of thermal hyperalgesia in rats with chronic constriction injury. Pain. 1999;79:31–37. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kihara M, Schmelzer JD, Low PA. Effect of cilostazol on experimental diabetic neuropathy in the rat. Diabetologia. 1995;38:914–918. doi: 10.1007/BF00400579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirchmair R, Walter DH, Ii M, Rittig K, Tietz AB, Murayama T, Emanueli C, Silver M, Wecker A, Amant C, Schratzberger P, Yoon YS, Weber A, Panagiotou E, Rosen KM, Bahlmann FH, Adelman LS, Weinberg DH, Ropper AH, Isner JM, Losordo DW. Antiangiogenesis mediates cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy: attenuation or reversal by local vascular endothelial growth factor gene therapy without augmenting tumor growth. Circulation. 2005;111:2662–2670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.470849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirchmair R, Tietz AB, Panagiotou E, Walter DH, Silver M, Yoon YS, Schratzberger P, Weber A, Kusano K, Weinberg DH, Ropper AH, Isner JM, Losordo DW. Therapeutic angiogenesis inhibits or rescues chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: taxol- and thalidomide-induced injury of vasa nervorum is ameliorated by VEGF. Mol Ther. 2007;15:69–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koban M, Leis S, Schultze-Mosgau S, Birklein F. Tissue hypoxia in complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2003;104:149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00484-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kokesh J, Kazmers A, Zierler RE. Pentoxifylline in the nonoperative management of intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg. 1991;5:66–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02021781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kukushkin ML, Smirnova VS, Gorizontova MP, Mironova IV, Zinkevich VA. Effect of clofelin and propranolol on the development of neurogenic pain syndrome in rats. Patol Fiziol Eksp Ter. 1993;4:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar N, Laferriere A, Yu JSC, Leavitt A, Coderre TJ. Evidence that pregabalin reduces neuropathic pain by inhibiting the spinal release of glutamate. J Neurochem. 2010;113:552–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurita GP, Pimenta CA. Compliance with chronic pain treatment: study of demographic, therapeutic and psychosocial variables. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2003;61:416–425. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2003000300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laferrière A, Millecamps M, Xanthos DN, Xiao WH, Siau C, de Mos M, Sachot C, Ragavendran JV, Huygen FJ, Bennett GJ, Coderre TJ. Cutaneous tactile allodynia associated with microvascular dysfunction in muscle. Mol Pain. 2008;4:49. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lekakis JP, Papamichael CM, Vemmos CN, Voutsas AA, Stamatelopoulos SF, Moulopoulos SD. Peripheral vascular endothelial dysfunction in patients with angina pectoris and normal coronary arteriograms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:541–546. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li C, Sekiyama H, Hayashida M, Takeda K, Sumida T, Sawamura S, Yamada Y, Arita H, Hanaoka K. Effects of topical application of clonidine cream on pain behaviors and spinal Fos protein expression in rat models of neuropathic pain, postoperative pain, and inflammatory pain. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:486–494. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000278874.78715.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lincoln TM. Cyclic GMP and mechanisms of vasodilation. Pharmacol Ther. 1989;41:479–502. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(89)90127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu J, Feng X, Yu M, Xie W, Zhao X, Li W, Guan R, Xu J. Pentoxifylline attenuates the development of hyperalgesia in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Neurosci Lett. 2007;412:268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Magnusson M, Bergstrand IC, Björkman S, Heijl A, Roth B, Höglund P. A placebo-controlled study of retinal blood flow changes by pentoxifylline and metabolites in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:138–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Magnusson M, Gunnarsson M, Berntorp E, Björkman S, Höglund P. Effects of pentoxifylline and its metabolites on platelet aggregation in whole blood from healthy humans. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;581:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manahan AP, Burkman KA, Malesker MA, Benecke GW. Clinical observation on the use of topical nitroglycerin in the management of severe shoulder-hand syndrome. Nebr Med J. 1993;78:87–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsumura H, Jimbo Y, Watanabe K. Haemodynamic changes in early phase reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Scandinavian J Plastic Reconstr Surg and Hand Surg. 1996;30:133–138. doi: 10.3109/02844319609056395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mazoit JX. Conventional techniques for analgesia: opioids and non-opioids. Indications, adverse effects and monitoring. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1998;17:573–584. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(98)80041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Messin R, Fenyvesi T, Carreer-Bruhwyler F, Crommen J, Chiap P, Hubert P, Dubois C, Famaey JP, Géczy J. A pilot double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study of molsidomine 16 mg once-a-day in patients suffering from stable angina pectoris: correlation between efficacy and over time plasma concentrations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0597-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Millecamps M, Coderre TJ. Rats with chronic post-ischemia pain (CPIP) exhibit an analgesic sensitivity profile similar to human patients with complex regional pain syndrome type I (CRPS-I) Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niehörster M, Schönharting M, Wendel A. A novel xanthine derivative counteracting in vivo tumor necrosis factor alpha toxicity in mice. Circ Shock. 1992;37:270–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Novo S, Abrignani MG, Liquori M, Sangiorgi GB, Strano A. The physiopathology of critical ischemia of the lower limbs. Ann Ital Med Int. 1993;8(Suppl):66S–70S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oka Y, Hasegawa N, Nakayama M, Murphy GA, Sussman HH, Raffin TA. Selective downregulation of neutrophils by a phosphatidic acid generation inhibitor in a porcine sepsis model. J Surg Res. 1999;81:147–155. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Palos GR, Mendoza TR, Cantor SB, Aday LA, Cleeland CS. Perceptions of analgesic use and side effects: what the public values in pain management. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:460–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Palmer RM, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Polomano RC, Mannes AJ, Clark US, Bennett GJ. A painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat produced by the chemotherapeutic drug, paclitaxel. Pain. 2001;94:293–304. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00363-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Quattrini C, Harris ND, Malik RA, Tesfaye S. Impaired skin microvascular reactivity in painful diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:655–659. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ragavendran JV, Laferriere A, Khorashadi M, Coderre TJ. The early anti-allodynic effect of pentoxifylline on chronic post-ischemia pain depends on modulation of plantar blood flow. Abstracts of the XIII World Congress on Pain; PT: IASP Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rice GC, Brown PA, Nelson RJ, Bianco JA, Singer JW, Bursten S. Protection from endotoxic shock in mice by pharmacologic inhibition of phosphatidic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3857–3861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Robless P, Mikhailidis DP, Stansby GP. Cilostazol for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD003748. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003748.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rybalkin SD, Beavo JA. Multiplicity within cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:1005–1009. doi: 10.1042/bst0241005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schurmann M, Zaspel J, Grandl G, Wipfel A, Christ F. Assessment of the peripheral microcirculation using computer-assisted venous congestion plethysmography in post-traumatic complex regional pain syndrome type I. J Vasc Res. 2001;38:453–461. doi: 10.1159/000051078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith RV, Waller ES, Doluisio JT, Bauza MT, Puri SK, Ho I, Lassman HB. Pharmacokinetics of orally administered pentoxifylline in humans. J Pharm Sci. 1986;75:47–52. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600750111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Spreux-Varoquaux O, Doll J, Dutot C, Grandjean N, Cordonnier P, Pays M, Andrieu J, Advenier C. Pharmacokinetics of molsidomine and its active metabolite, linsidomine, in patients with liver cirrhosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;32:399–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb03919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sternitzky R, Seige K. Clinical investigation of the effects of pentoxifylline in patients with severe peripheral occlusive vascular disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 1985;9:602–610. doi: 10.1185/03007998509109641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stewart WC. Effect and side effects of apraclonidine. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1996;209:A7–A13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Suh KS, Oh SJ, Woo JT, Kim SW, Yang IM, Kim JW, Kim YS, Choi YK, Park IK. Effect of cilostazol on the neuropathies of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Korean J Intern Med. 1999;14:34–40. doi: 10.3904/kjim.1999.14.2.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sztajzel J, Mach F, Righetti A. Role of the vascular endothelium in patients with angina pectoris or acute myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:16–21. doi: 10.1136/pmj.76.891.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ting JC, Fukshansky M, Burton AW. Treatment of refractory ischemic pain from chemotherapy-induced Raynaud’s syndrome with spinal cord stimulation. Pain Pract. 2007;7:143–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2007.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.van der Laan L, ter Laak HJ, Gabreels-Festen A, Gabreels F, Goris RJA. Complex regional pain syndrome type I (RSD): pathology of skeletal muscle and peripheral nerve. Neurology. 1998;51:20–25. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Van Zwieten PA, Thoolen MJ, Timmermans PB. The pharmacology of centrally acting antihypertensive drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;15(Suppl 4): 455S–462S. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Waldman SA, Murad F. Cyclic GMP synthesis and function. Pharmacol Rev. 1987;39:163–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wattanasirichaigoon S, Menconi MJ, Delude RL, Fink MP. Lisofylline ameliorates intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction caused by ischemia and ischemia/reperfusion. Shock. 1999;11:269–275. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199904000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Waxman K, Daughters K, Aswani S, Rice G. Lisofylline decreases white cell adhesiveness and improves survival after experimental hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1724–1728. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199610000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weiss B, Hait WN. Selective cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1977;17:441–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.17.040177.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xanthos DN, Bennett GJ, Coderre TJ. Norepinephrine-induced nociception and vasoconstrictor hypersensitivity in rats with chronic post-ischemia pain. Pain. 2008;137:640–651. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]