Abstract

We studied the biodegradation of green polyethylene (GP) by Pleurotus ostreatus. The GP was developed from renewable raw materials to help to reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases. However, little information regarding the biodegradation of GP discarded in the environment is available. P. ostreatus is a lignocellulolytic fungus that has been used in bioremediation processes for agroindustrial residues, pollutants, and recalcitrant compounds. Recently, we showed the potential of this fungus to degrade oxo-biodegradable polyethylene. GP plastic bags were exposed to sunlight for up to 120 days to induce the initial photodegradation of the polymers. After this period, no cracks, pits, or new functional groups in the structure of GP were observed. Fragments of these bags were used as the substrate for the growth of P. ostreatus. After 30 d of incubation, physical and chemical alterations in the structure of GP were observed. We conclude that the exposure of GP to sunlight and its subsequent incubation in the presence of P. ostreatus can decrease the half-life of GP and facilitate the mineralization of these polymers.

Introduction

Due to the high per capita consumption, the accumulation of plastic waste in the environment is a primary source of pollution [1,2]. Plastic polymers are stable and barely undergo degradation in the cycle of nutrients of the biosphere [3]. It is estimated that polyethylene requires more than 100 years to be mineralized in the soil [4]. An alternative to reduce the accumulation of plastic wastes in the environment is the development of biodegradable plastic polymers that are economically viable and environment friendly.

In da Luz et al. [5], we showed that Pleurotus ostreatus can degrade and produce mushrooms using oxo-biodegradable plastic waste without any prior physical treatment. In da Luz [6], we evaluated the abiotic and biotic degradation of oxo-biodegradable plastic bags throughout 120 days of sunlight exposure and 90 days of fungal growth. Oxo-biodegradable polymers contain pro-oxidants and pro-degrading compounds [2,7] that are incorporated into the polymer chain to accelerate photo- or thermo-oxidation [2,7,8]. In this study, we investigated the degradation of green polyethylene by P. ostreatus. Green plastics are polymers developed from renewable raw materials such as sugarcane. Because plants capture and sequester carbon dioxide (CO2) during their growth, these biopolymers can help to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases [9]. These plastics can also be recycled [9]. However, there is no information available regarding the half-life or the degradation rate of these green polymers when discarded in the environment.

P. ostreatus is a lignocellulolytic fungus that can use lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose as carbon and energy sources [10–12]. This fungus has been used in the degradation of agroindustrial residues [10,13,14], the bioremediation of pollutants [12,15] and pulp bleaching [15]. The ability of lignocellulolytic fungi to degrade a large range of compounds is related to the high efficiency of their enzymatic system [14].

Materials and Methods

Plastic bags were kindly donated by Fundação Arthur Bernandes. According to the manufacturer, these plastic bags are produced using low-density polyethylene and contain more than 50% green polymers that were developed from renewable raw materials. The information provided by the manufacturer regarding the types of polymers was confirmed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR).

Pleurotus ostreatus PLO6 (GenBank accession number KC782771) used in this study belongs to the collection of the Department of Microbiology of the Federal University of Viçosa, MG, Brazil. The stock cultures were maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Mycelium of each stock culture were grown at 25°C on PDA agar in Petri dishes. After 15 d, mycelial disks were punched out with a 7 mm diameter cork borer and used to inoculate the substrates.

2.1 Abiotic degradation

The green polyethylene was exposed to sunlight for 30, 60, 90, and 120 days during the summer at a site protected from rainwater [6]. In this season, the duration of sunlight is 9 hours with a maximum intensity between noon and 3 hours. After each period of exposure, the plastic bags were submitted to physical and chemical analysis (see item 2.4).

2.2 Biotic degradation

Plastic bags were cut into fragments (5 cm x 1 cm), and 10 g of this material was placed in a 100 mL glass flask with 0.1 g of a commercially available paper towel [5]. Five milliliters of mineral medium [8,16] supplemented with 0.1 mL of filter-sterilized thiamine-HCl were added to the flasks. Four discs of agar containing the mycelium of P. ostreatus were inoculated into flasks, and the flasks were incubated at 25°C for 30, 60 or 90 days.

Plastic bags that had not been exposed to sunlight served as an experimental control.

2.3 Fungal respiratory activity and dry mass

The respiratory activity was measured by coupling the flasks to a continuous-flow respirometer coupled to an infrared CO2 detector (TR-RM8 Respirometer Multiplexer–Sable systems). CO2 measurements were performed every 24 h [17], and the flasks remained coupled to the respirometer throughout the study period.

To determine the dry mass, the flasks containing the fungal mycelium and substrates were dried at 105°C until a constant weight was obtained [6].

2.4 Analysis of the biodegradation of green polymers

The mineral composition of the green polyethylene before and after 120 days of exposure to sunlight was determined by SEM coupled with X-ray diffraction [5]. This technique is a semi-quantitative method and the percentage was calculated with base in the minerals analyzed (Table 1).

Table 1. Chemical composition of the green polyethylene before and after 120 d of exposure to sunlight.

| Mineral Composition* | Exposure time to sunlight (days) | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 120 | |

| Si | 41.19 A | 35.83 B |

| Mn | 8.51 A | 7.41A |

| Fe | 7.74 A | 6.73 A |

| Co | 6.31 A | 5.49 A |

| Cu | 3.05 A | 2.65 A |

| Zn | 8.08 A | 7.03 A |

| Cd | 22.06 A | 19.19 B |

| N | 2.80 A | 2.44 A |

* Relative concentration of elements ((weight %) at the surface of the plastic bags, analyzed by scanning electron microscopy coupled to X ray diffraction (semi-quantitative method). Means followed by different letters within the same line differ at Tukey test (P<0.05).

Physical changes, such as the formation of pits and cracks, and fungal colonization of the plastic surface were analyzed by SEM (Leo, 1430VP) with a magnification of 5000 X [5,7,18].

Alterations of the mechanical properties of the plastic were analyzed using universal testing equipment (Instron model 3367).

Chemical changes, such as the disappearance or formation of new functional groups and bond scission, were analyzed by FTIR [2,8,19]. The plastic strip fragment was placed in an appropriate support for solid sampling in the spectrophotometer (Thermo Nicolet).

2.5 Statistical analyses

The experiment followed a completely randomized design with five replicates. The data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). For chemical composition, mean values were compared by Tukey’s test, and dry mass and respiratory activity were subjected to regression analysis. These statistical analyses were performed using Saeg software (version 9.1, Universidade Federal de Viçosa) at a 5% significance value (p < 0.05). For mechanical properties, the average and standard deviation are presented.

Results

3.1 Abiotic degradation

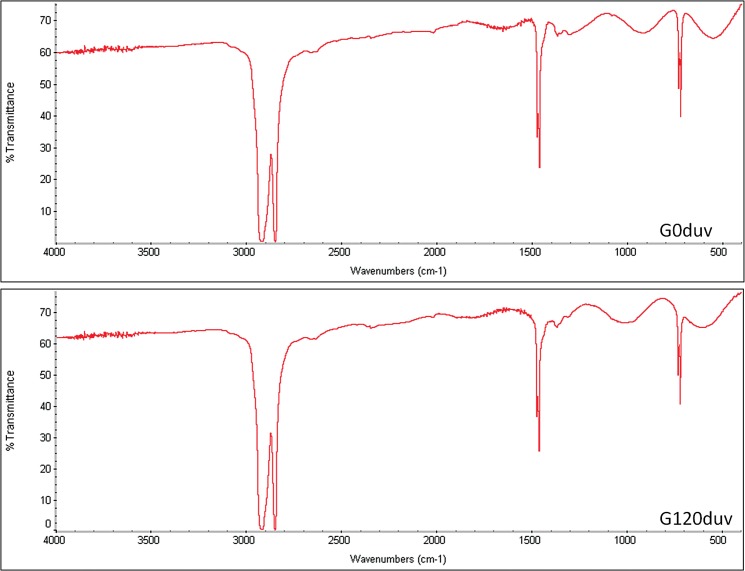

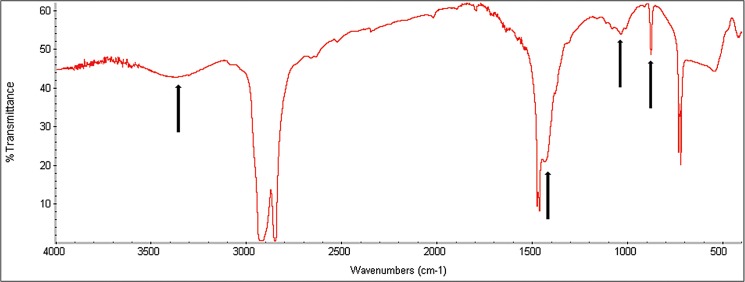

The bands of the FTIR spectrum before exposure to sunlight confirmed the information provided by the manufacturer that the plastic bags were produced using low-density polyethylene (Fig 1).

Fig 1. FTIR spectrum of the green polyethylene before (G0duv) and after 120 d of exposure to sunlight (G120duv).

The bands: 3000–2500 cm-1 –Bond carbon-hydrogen (CH2 or CH3); 1500–1400 cm-1—Bond carbon-hydrogen (CH) and 800–700 cm-1—Bond carbon-carbon (C-C).

Silicon and cadmium were the main minerals found in the plastic bags used in this study (Table 1). Silicon can be involved in polyethylene polymerization by metallocene catalysts [20]. Some chemical elements that are essential for microbial growth, such as nitrogen, manganese, iron and zinc, were also detected (Table 1). Dyes that are commonly used in the production of commercial plastic bags may be the source of these and of the other elements shown in Table 1.

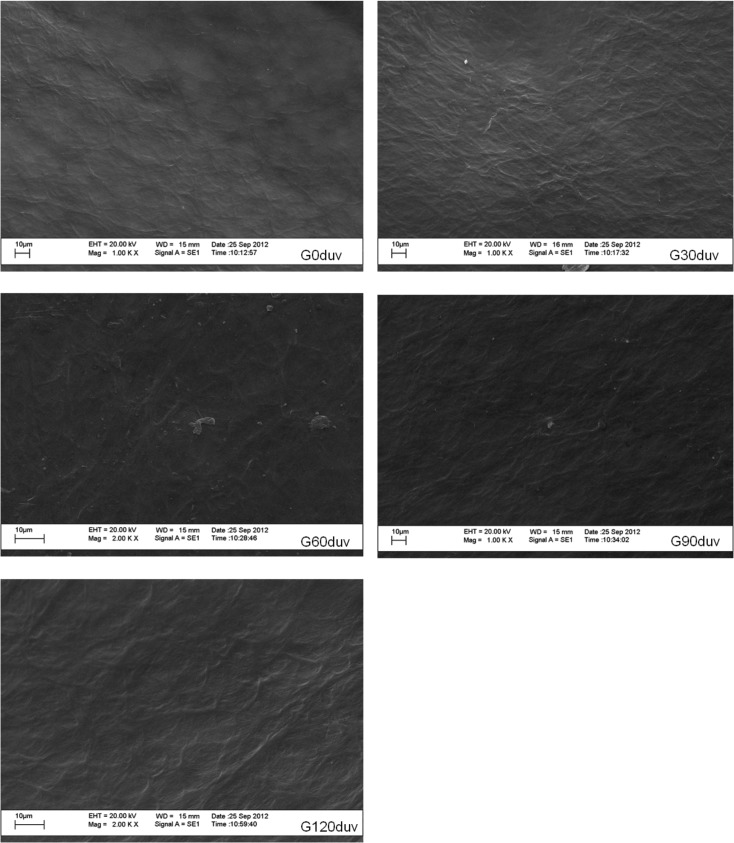

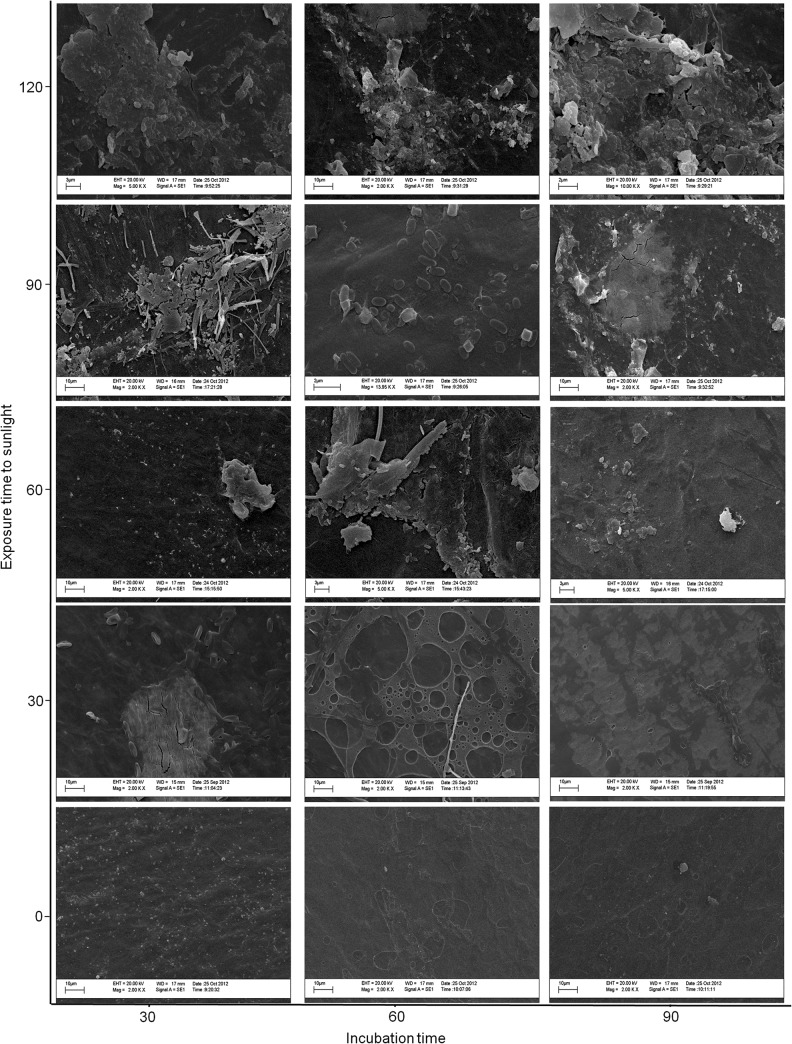

After 120 d of exposure to sunlight, we observed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the relative concentrations of silicon and cadmium (Table 1). No cracks, pits or new functional groups were observed after this period (Figs 1 and 2), demonstrating that sunlight was not able to induce the abiotic degradation of these green plastics. However, sunlight exposure altered the mechanical properties of the material (Table 2). After 90 d of exposure to sunlight, the plastic was much more fragile and brittle, and these characteristics prevented the determination of its mechanical properties (Table 2). This suggests that the exposure of GP to sunlight can promote some sort of modification, and this in turn may improve the biological degradation of these plastic polymers.

Fig 2. Scanning electron micrography of green polyethylene surface before (G0duv) and after 30 d (G30duv), 60 d (G60duv), 90 d (G90duv) or 120 d (G120duv) of exposure to sunlight.

Note the absence of any expressive modification in the plastic surface due to sunlight exposure.

Table 2. Mechanical properties of the green polyethylene before and after 30, 60, 90 and 120 days of exposure to sunlight.

| Mechanical properties | Exposure time to sunlight (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 30 | 60 | <90* | |

| Maximum load of break (N) | 3.119 ± 0.461 | 2.938 ± 0.347 | 2.718 ± 0.486 | nd |

| Energy at break (J) | 0.720 ± 0.010 | 0.490 ± 0.08 | 0.350 ± 0.02 | |

| Tensile extension at break (cm) | 5.193 ± 0.708 | 4.430 ± 0.654 | 4.198 ± 0.858 | |

| Load at tensile strength (N) | 2.067 ± 0.334 | 2.037 ± 0.761 | 1.743 ± 0.304 | |

| Elastic modulus (MPa) | 23.992 ± 2.567 | 20.905 ± 1.344 | 15.798 ± 0.861 | |

* nd- values were not determined due to the high fragility of the material.

3.2 Biotic degradation

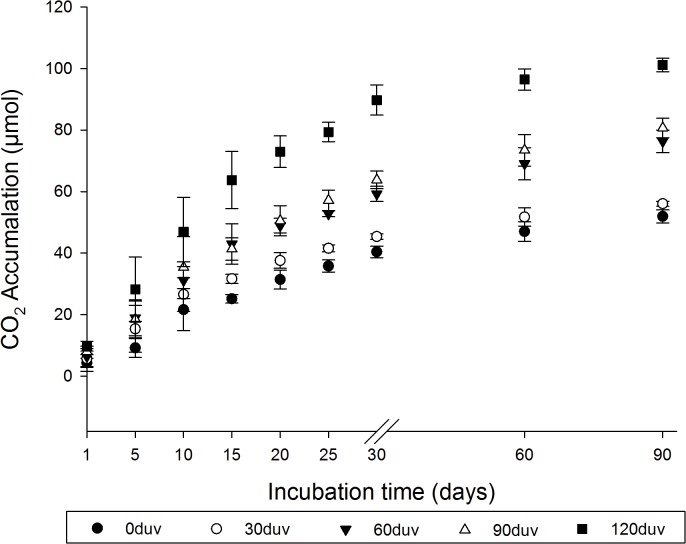

The CO2 emissions from the microcosms inoculated with P. ostreatus were the highest in plastics with 120 d of exposure to sunlight (Fig 3). No differences (p > 0.05) in the CO2 emissions were observed between the microcosms with plastics exposed to sunlight for zero and 30 days, or for 60 and 90 days (Fig 3). These results shows that (a) P. ostreatus can grow independent of exposure to sunlight using green polyethylene as a substrate and (b) alterations of the mechanical properties caused by sunlight (Table 2) may have contributed to the fungal growth by increasing the contact surface.

Fig 3. Respiratory activity of Pleurotus ostreatus grown during 90 days in green polyethylene before (Oduv) and after 30 d (30duv), 60 d (60duv), 90 d (90duv) or 120 d (120duv) days of exposure to sunlight.

The fungi caused the greatest reductions in the mechanical properties of plastics that had been previously exposed to sunlight for a longer period of time (Table 3). It was not possible to determine the mechanical properties (Table 3) or chemical alterations by FTIR due to the fragility of some of the plastic fragments.

Table 3. Mechanical properties of green polyethylene exposure or not to sunlight after 30, 60 or 90 d of incubation with Pleurotus ostreatus.

| Mechanical properties | Time of incubation (days) | Exposition time of the ultraviolet light (days) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 30 | 60 | ||

| Maximum load of break (N) | 30 | 2.839 ± 0.483 | 2.069 ± 0.311 | 0.548 ± 0.087 |

| 60 | 1.728 ± 0.341 | 1.309 ± 0.305 | nd | |

| 90 | nd | |||

| Energy at break (J) | 30 | 0.628 ± 0.058 | 0.420 ± 0.020 | 0.122 ± 0.031 |

| 60 | 0.479 ± 0.043 | 0.401 ± 0.027 | nd | |

| 90 | nd | |||

| Tensile extension at break (cm) | 30 | 5.021 ± 0.738 | 3.180 ± 0.952 | 1.390 ± 0.199 |

| 60 | 4.425 ± 0.679 | 3.022 ± 0.843 | nd | |

| 90 | nd | |||

| Load at tensile strength (N) | 30 | 1.761 ± 0.644 | 1.128 ± 0.313 | 0.258 ± 0.050 |

| 60 | 1.352 ± 0.873 | 0.639 ± 0.150 | nd | |

| 90 | nd | |||

| Elastic modulus (MPa) | 30 | 21.962 ± 4.771 | 15.798 ± 1.195 | 4.222 ± 0.781 |

| 60 | 20.470 ± 3.341 | 10.073 ± 2.352 | nd | |

| 90 | nd | |||

nd-values were not determined due to the high fragility of the plastic wastes.

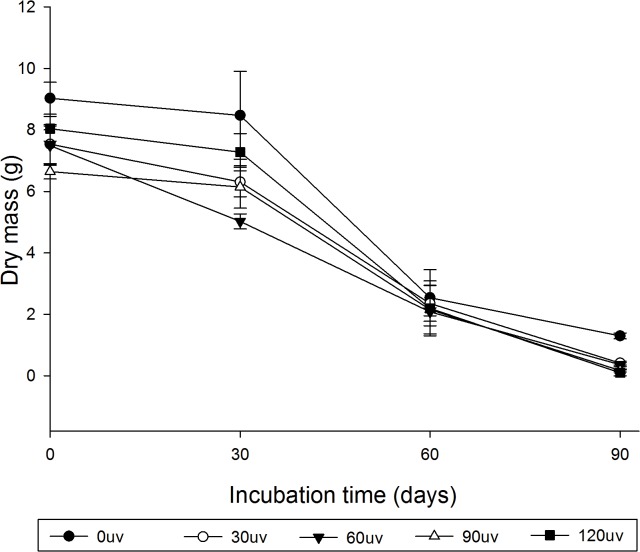

We observed a significant reduction in the dry mass of the substrates during the incubation period (Fig 4). This occurred independently of the period of exposure to sunlight (Fig 4). These results show that P. ostreatus could metabolize the green polyethylene without prior physical treatment.

Fig 4. Dry mass of the substrate used by Pleurotus ostreatus for up to 90 d of incubation.

Green polyethylene before (0duv) and after 30 d (30duv), 60 d (60duv), 90 d (90duv) or 120 d (120duv) of exposure to sunlight.

The primary chemical alterations in the structure of the green polyethylene after fungal incubation resulted in the formation of four bands with wavelengths between 3500–3200 cm-1 and 1500–950 cm-1 (Fig 5). The band at 3500–3200 cm-1 is typical of a hydrogen-oxygen bond (OH), and the other bands are related to carbon-oxygen (CO), carbon-hydrogen (CH or CH2), and hydrogen-oxygen (OH) bonds.

Fig 5. Espectrum of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of the green polyethylene after 120 d of exposure to sunlight and 90 d of incubation with Pleurotus ostreatus.

The arrows show the bands that were observed after the fungal incubation (See also Fig 1).

Regardless of exposure to sunlight, we observed physical alterations at the surface of the green polyethylene (Fig 6). However, these alterations were more evident in the polymers that were exposed to sunlight for a longer period before incubation with P. ostreatus than in the polymers without any previous sunlight exposure (Fig 6). These alterations confirm that green polyethylene can be degraded by P. ostreatus.

Fig 6. Scanning electron microscopy of green polyethylene exposed to sunlight for 0–120 d and incubated with Pleurotus ostreatus by 30, 60 or 90 d.

Discussion

It has been suggested for at least 30 years that exposure to UV light, thermal heating or acid hydrolysis can initiate the thermal or photo-oxidation of polyethylene and thus promote fragmentation and possible microbial attack [2,18]. In this study, we did not observe any fragmentation or formation of new functional groups (Fig 1 and Fig 2) in the structure of green polyethylene after exposure to sunlight for up to 120 days. However, alterations in the mechanical properties of these polymers caused by sunlight (Table 2) were important for fungal growth (Fig 3) and for the biotic degradation of the green polyethylene (Fig 6). Thus, GP exposure to sunlight before composting or dumping in landfills may accelerate its biodegradation.

The degradation of a polymer in nature depends on various factors, such as humidity, light intensity, pH, the chemical structure of the polymer and the potential of microorganisms to use the polymer as a carbon or energy source [7,21,22]. In this study we showed the capability of P. ostreatus PLO6 to degrade green polyethylene (Fig 6). This potential was attributed to the complex of lignocellulolytic enzymes produced by this fungus. Several studies have suggested the participation of this enzymatic complex in the degradation of plastic polymers [23,24]. Da Luz et al. [5] showed that laccase, cellulase and xylanase are active during the growth of P. ostreatus on substrates containing oxo-biodegradable plastics and paper towels. According to these authors, the degradation of oxo-biodegradable polymers was primarily due to the activity of the laccases. Therefore, once conditions for microbial growth are established, principally those required for the growth of lignocellulolytic fungi, green polyethylene could be readily metabolized.

Nitrogen availability is a limiting factor for microbial growth [16,25]. The abundance of this element in the green polyethylene was lower than 3% (Table 1). Da Luz et al. [6] reported the presence of endomycotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the fungal hyphae of P. ostreatus PLO6. Other authors have also reported the presence of these bacteria in the hyphae of this species [26,27]. Thus, the growth of P. ostreatus (Fig 3) on green polyethylene may have been facilitated by the presence of these microorganisms that may have provided nitrogen for its growth. Yara et al. [27] suggested that interactions between nitrogen-fixing microorganisms and P. ostreatus can be an important factor in bioleaching and bioremediation.

Da Luz et al. [6] suggested that the degradation of oxo-biodegradable plastics by P. ostreatus was possibly due to (a) the presence of pro-oxidant ions in the polymers, (b) the low specificity of the lignocellulolytic enzymes for their substrate and (c) the presence of endomycotic nitrogen-fixing microorganisms in the P. ostreatus fungal hyphae. In our study, 50% of the green polymers were derived from sugarcane and served a substitute for the pro-oxidant ion. The low specificity of the lignocellulolytic enzymes could be observed in the degradation of green polyethylene because green polyethylene has little to no structural similarity with lignocellulosic compounds. The low specificity of these enzymes has also been shown to allow for the biodegradation of many pollutants, including some recalcitrant molecules [28–31]. Roldán-Carrillo et al. [32] also showed the degradation of plastic polymers containing starch by enzymes produced by Phanerochaete chrysosporium.

The chemical alterations observed in this study have also been shown in others studies [5,19,33]. These alterations are evidence of the oxidation of green polyethylene by P. ostreatus.

Physical alterations on the surface of green polyethylene (Fig 6) and the loss of dry mass (Fig 4) are additional evidence for the mineralization of the substrate by P. ostreatus.

Conclusions

Regardless of exposure to sunlight, Pleurotus ostreatus PLO6 can degrade green polyethylene. The exposure of the plastic to sunlight and its subsequent incubation in the presence of the fungus could be an alternative way to decrease the half-life of plastic waste in dumps or landfills.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to FUNARBE for having donated the plastic bags and to the Núcleo de Microscópia of UFV for the use of the SEM.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the Brazilian Financial Agencies: CAPES, CNPq, and FAPEMIG. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Arutchelvi JSM, Arkatkar A, Soble M, Bhaduri S, Uppara PV. Biodegradation of polyethylene and polypropylene. Indian Journal of Biotechnology 2008;7: 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shah AA, Hasan F, Hameed A, Ahmed S. Biological degradation of plastics: A comprehensive review. Biotechnol Adv. 2008;26: 246–265. doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.12.005 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shimao M. Biodegradation of plastics. Curr Opin Biotech. 2001;12: 242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ohtake Y, Kobayashi T, Asabe H, Murakami N. Studies on biodegradation of LDPE—observation of LDPE films scattered in agricultural fields or in garden soil. Polym Degrad Stabil. 1998;60: 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luz JMR, Paes SA, Nunes MD, da Silva MCS, Kasuya MCM. Degradation of oxo-biodegradable plastic by Pleurotus ostreatus . PLOS ONE. 2013;8: e69386 10.1371/journal.pone.0069386.g003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. da Luz JMR, Paes SA, Bazzolli DMS, Totola MR, Demuner AJ, et al. Abiotic and biotic degradation of oxo-biodegradable plastic bags. PLOS ONE. 2013;9(11): e107438 10.1371/journal.pone.0107438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ojeda TFM, Dalmolin E, Forte MMC, Jacques RJS, Bento FM, et al. Abiotic and biotic degradation of oxo-biodegradable polyethylenes. Polym Degrad Stab. 2009;94: 965–970. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2009.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koutny M, Sancelme M, Dabin C, Pichon N, Delort AM, et al. Acquired biodegradability of polyethylenes containing pro-oxidant additives. Polym Degrad Stab. 2006;91: 1495–1503. doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2005.10.007 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braskem. Green Polyethylene Biopolymer, innovation transforming plastic into sustainability. 2013. Available: http://www.braskem.com.br/Portal/Principal/Arquivos/ModuloHTML/Documentos/846/AF_Catalogo_PE%20Verde_2014_ING_site.pdf.

- 10. Cavazzalli JRP, Brito MS, Oliveira MGA, Villas-Bôas SG, Kasuya MCM. Lignocellulolytic enzymes profile of three Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegler strains during cultivation on eucalyptus bark-based medium. Food Agric Environ. 2004;2: 291–297. [Google Scholar]

- 11. da Luz JMR, Paes SA, Nunes MD, Torres DP, da Silva MCS, et al. Lignocellulolytic enzyme production of Pleurotus ostreatus growth in agroindustrial wastes. Braz J Microbiol. 2012;43: 1508–1515. 10.1590/S1517-83822012000400035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pérez SR, Oduardo NG, Savón RCB, Boizán MF, Augur C. Decolourisation of mushroom farm wastewater by Pleurotus ostreatus . Biodegradation. 2009;19: 519–526. 10.1007/s10532-007-9157-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. da Luz JMR, Paes SA, Torres DP, Nunes MD, da Silva JS, et al. Production of edible mushroom and degradation of antinutritional factors in jatropha biodiesel residues. Food Sci Technol–LEB. 2013;50: 575–580. 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.08.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sánchez C. Lignocellulosic residues: Biodegradation and bioconversion by fungi. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27: 185–194. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cohen R, Persky L, Hadar Y. Biotechnological applica-tions and potential of wood-degrading mushrooms of the genusPleurotus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;58: 582–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nunes MD, da Luz JMR, Paes SA, Ribeiro JJO, da Silva MCS, et al. Nitrogen supplementation on the productivity and the chemical composition of oyster mushroom. JFR. 2012;1: 113–119. 10.5539/jfr.v1n2p113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heinemeyer O, Insam H, Kaiser EA, Walenzik G. Soil microbial biomass and respiration measurements: An automated technique based on infra-red gas analysis. Plant Soil. 1989;116: 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bonhomme S, Cuer A, Delort AM, Lemaire J, Sancelme M, et al. Environmental biodegradation of polyethylene. Polym Degrad Stab. 2003;81: 441–452. 10.1016/S0141-3910(03)00129-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sudhakar M, Doble M, Sriyutha MP, Venkatesan R. Marine microbe mediated biodegradation of low and high density polyethylenes. Intern Biodeter Biodegr 2008;61: 203–213. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2007.07.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li KT, Li CY. Nano-Sized Silica Supported Me2Si(Ind)2ZrCl2/MAO Catalyst for Ethylene Polymerization. J Appl Polym Sci. 2012;123: 1169–1175. 10.1002/app.34579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Contat-Rodrigo L, Ribes Greus A. Biodegradation studies of LDPE filled with biodegradable additives: Morphological changes. J Appl Polym Sci. 2002;83: 1683–1691. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gross RA, Kalra B. Biodegradable Polymers for the Environment. Science 2002;297: 803–807. 10.1126/science.297.5582.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sivan A. New perspectives in plastic biodegradation. Curr Opin Biotech. 2011;22: 1–5. 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Santo M, Weitsman R, Sivan A. The role of the copper-binding enzyme—laccase—in the biodegradation of polyethylene by the actinomycete Rhodococcus ruber . Int Biodeter Biodegr. 2013;84: 204–210. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2012.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. El-Sharkawi H. Effect of Nitrogen Sources on Microbial Biomass Nitrogen under Different Soil Types. ISRN Soil Science. 2012: 7 10.5402/2012/310727 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grube M, Berg G. Microbial consortia of bacteria and fungi with focus on the lichen symbiosis. Fungal biol rev. 2009;23: 72–85. 10.1016/j.fbr.2009.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yara R, Maccheroni W Jr, Horii J, Azevedo JL. A Bacterium Belonging to the Burkholderia cepacia Complex Associated with Pleurotus ostreatus . J Microbiol. 2006;44: 263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alberts JF, Gelderblom WCA, Botha A, van Zyl WH. Degradation of aflatoxin B1 by fungal laccase enzymes. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;135: 47–52. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kasuya MCM, da Luz JMR, Pereira LPS, da Silva JS, Montavani HC, et al. Bio-detoxification of jatropha seed cake and its use in animal feed In: Fang Z, editor. Feedstocks, production and applications. Rijeka, Croatia: Intech; 2012. p. 487. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Majcherczyk A, Johannes C, Hüttermann A. Oxidation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) by laccase of Trametes versicolor . Enzym Microbiol Technol 1998; 22: 335–341. 10.1016/S0141-(97)00199-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nyanhongo GS, Erlacher A, Schroeder M, Gubitz GM. Enzymatic immobilization of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) biodegradation products onto model humic substances. Enzym Microbiol Technol. 2006;39: 1197–1204. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2006.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roldán-Carrillo T, Rodríguez-Vázquez R, Díaz-Cervantes D, Vázquez-Torres H, Manzur-Guzmán A, et al. Starch-based plastic polymer degradation by the white rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium grown on sugarcane bagasse pith: enzyme production. Bioresour Technol. 2003;86: 1–5. 10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00142-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chiellini E, Corti A, D'Antone S. Oxo-biodegradable full carbon backbone polymers–biodegradation behaviour of thermally oxidized polyethylene in an aqueous medium. Polym Degrad Stab. 2007;92: 1378–1383. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2007.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.