Abstract

The discovery of a novel peripherally acting and selective Cav3.2 T-type calcium channel blocker, ABT-639, is described. HTS hits 1 and 2, which have poor metabolic stability, were optimized to obtain 4, which has improved stability and oral bioavailability. Modification of 4 to further improve ADME properties led to the discovery of ABT-639. Following oral administration, ABT-639 produces robust antinociceptive activity in experimental pain models at doses that do not significantly alter psychomotor or hemodynamic function in the rat.

Keywords: Cav3.2, T-type calcium channel, pain, sulfonamides, ADME

Voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) play an important role in the regulation of calcium influx into cells in response to change membrane conductance, thereby activating various physiological functions, such as neurotransmitter release, cellular excitability, muscle contraction and many others.1 These channels can be classified into low-voltage activated T-type, high-voltage activated L-type, and P/Q-, N-, and R-type calcium channels. N-type calcium channels are found primarily at presynaptic terminals and are involved in neurotransmitter release.2,3 T-type channels are primarily involved in postsynaptic excitability.4 Recent studies have shown that T-type calcium channels may be important therapeutic targets for the treatment of several neurophysiological disorders, including epilepsy,5 pain,6−8 hypertension,9 sleep architecture,10 tremor,11 and Parkinson’s disease.12,13

Cav3.2 is the predominant T-type calcium channel isoform in sensory nerves that modulate nociception and is expressed in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons, peripheral receptive fields, spinal cord dorsal horn, and brain.14 Bourinet et al. demonstrated that silencing of Cav3.2 channel strongly reduced acute and neuropathic nociception.15 Intrathecal administration or local injection of Cav3.2-specific, but not Cav3.1- and Cav3.3-specific antisense oligonucleotides, produces a significant knockdown of Cav3.2 T-type currents in nociceptive DRG neurons, and robust long-lasting and reversible mechanical and thermal antinociceptive effects. Jagodic et al. demonstrated that following chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve induced upregulation of T-type calcium channel currents in small rat DRG.16 Modulation of the Cav3.2 (α1H) channel controls the sensitization of nociceptors, the peripheral pain-sensing neurons.17 These results further support Cav3.2 T-type channels as a mechanism for modulating nociceptive sensitivity.

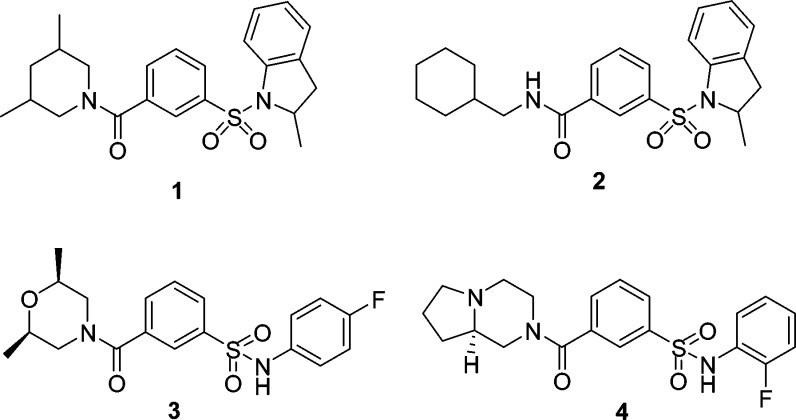

High throughput screening (HTS) generated a number of sulfonamide hits including 1 (IC50 = 3 μM) and 2 (IC50 = 5 μM) (Figure 1) against Cav3.2 T-type channel in a FLIPR based Ca2+ flux assay.18,19 However, HTS hits 1 and 2 are metabolically unstable in rats and both have very poor oral bioavailability (F = 0.5% and 1.9%, respectively) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of hits 1 and 2 and leads 3 and 4.

Table 1. RLM and PK Parameters of Compounds 1, 2, 3, and 4.

| RLMa (%) | cLogP | Vβ (L/kg) | CLp (L/h/kg) | t1/2 (h) | F (%) (p.o.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.3 | 4.4 | 4.94 | 1.90 | 1.80 | 0.5b |

| 2 | 0.1 | 5.3 | 11.1 | 3.47 | 2.16 | 1.9b |

| 3 | 46 | 3.1 | 0.75 | 1.66 | 0.31 | 29.0c |

| 4 | 68 | 2.8 | 0.65 | 1.79 | 0.25 | 31.3c |

Rat Liver Microsomal stability. Percentage remaining after 30 min at 1 μM.

3 μM/kg iv and po.

5 μM/kg iv and 30 μM/kg po. Oral formulation: PEG400/cremophor EL/oleic acid (10:10:80, by weight 2 mL/kg).

Since the potency of 1 and 2 were in a similar range to other previously described T/N-type calcium channel blockers, lead optimization efforts were focused on improving ADME properties for these hits.20 Modification of both sulfonamide and amide sides of these hits led to identification of a new lead 3, which has a lower cLogP than 1 and 2. Compound 3 afforded 29% oral bioavailability in rats. Unfortunately, the half-life (t1/2) of 3 following i.v. dosing at 5 μmol/kg was only 0.31 h, mainly due to the high plasma clearance rate (CLp) of 1.66 L/h/kg and a low volume distribution (Vβ) of 0.75 L/kg (Table 1).

After evaluating several diamines, a rigid bicyclic diamine was identified to replace dimethylmorpholine in 3. Compound 4 demonstrated better stability in rat liver microsomes compared to 1, 2, and 3. However, the plasma clearance rate of 4 is still high (1.79 L/h/kg) with a volume distribution (Vβ) of 0.65 L/kg in rats. In order to further improve the ADME properties and PK profile of 4, compounds 5 to 9 and the (S)-enantiomers 4b to 6b with different R2 groups, which have electron-withdrawing substituents on anilines, were investigated to compare their plasma clearance (CLp) and oral bioavailability (Table 2). We observed that the plasma clearance (CLp) rate of the (R)-enantiomers (4, 5, and 6) is lower than that of the (S)-enantiomers (4b, 5b, and 6b), and the oral bioavailability in rats is improved for the (R)-enantiomers; i.e. compound 4b, the (S)-enantiomer of 4, shows higher plasma clearance (3.36 L/h/kg) than the (R)-enantiomer of 4. Compound 7 with 2-chloroaniline had increased CLp and decreased bioavailability compared to 4, but compounds 5, 8, 6, and 9 with 2,3-, 2,6-difluoroaniline, and 4-, 2-(trifluoromethyl)aniline had lower CLp and higher bioavailability. Compounds 6 and 6b have an excellent PK profile with CLp of 0.45–0.81 L/h/kg and oral bioavailability of 76–100%. However, compound 4 is the only one in Table 2 that shows IC50 = 10.6 μM potency; other compounds in Table 2 are weak Cav3.2 T-type calcium channel blockers (<30% inhibition @ 10 μM). Our next attempt was to add the halogen atoms to the central aromatic ring since it is possible that the high plasma clearance rate was also due to the metabolic oxidation of the central aromatic ring.

Table 2. Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Compounds 4 to 9 and 4b to 6ba.

5 μM/kg iv and 30 μM/kg po. Oral formulation: PEG400/cremophor EL/oleic acid (10:10:80, by weight 2 mL/kg).

Substituent on aromatic ring can influence the microsomal stability and pharmacokinetic properties of the compounds.21 Introduction of the F or Cl atom to the central aromatic ring of 4 led to the discovery of ABT-639 (Figure 2), which has a significantly decreased plasma clearance rate of 0.55 L/h/kg. The volume distribution (Vβ) was increased to 2.7 L/kg, and the half-life (t1/2) of ABT-639 was improved to 3.3 h in rats. The oral bioavailability in rats was also significantly improved (F = 73%). The increase in volume distribution in rat and monkey may be due to the increase of tissue-binding or partitioning into fat since the cLogP (3.8) of ABT-639 is larger than the cLogP (1.79) of 4.22 Compound 10 with dichloro substitutes on the central aromatic ring was prepared and showed weaker potency (IC50 = 19 μM) against Cav3.2 T-type calcium channel with 44% oral bioavailability. Addition of a methyl group to the sulfonamide side of ABT-639 gives compound 11 (Figure 2). Remarkably, compound 11 had decreased stability in rat (RLM) and human liver microsomes (HLM) from 81–95% to less than 0.01%. The (S)-enantiomer of ABT-639 was also synthesized, it has 57% oral bioavailability in rats.

Figure 2.

ABT-639 and its analogues 10 and 11.

Synthesis of ABT-639 and its analogues is outlined in Scheme 1. ABT-639 was obtained in 77% overall yield in three steps with one-step purification from commercially available starting materials. 2-Chloro-5-(chlorosulfonyl)-4-fluorobenzoyl chloride was prepared by reaction of 2-chloro-5-(chlorosulfonyl)-4-fluorobenzoic acid with oxalyl chloride at room temperate in the presence of DMF as a catalyst. Addition of one equivalent of (R)-octahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine to this resulting benzoyl chloride slowly over 1 h generated the amide intermediate, (R)-4-chloro-2-fluoro-5-(octahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-2-carbonyl)benzene-1-sulfonyl chloride. Since the amide formation is at a much faster rate than the sulfonamide formation, very little or no side products were detected by LC–MS. Subsequent sulfonamide formation was completed overnight by addition of 2-fluoroaniline to afford ABT-639 after purification by chromatography. Compound 10 was prepared starting from commercially available 2,4-dichloro-5-(chlorosulfonyl)benzoic acid by following the same synthetic route of preparation of ABT-639. Compound 11 was obtained in 71% overall yield by using the same procedures. 2-Fluoro-N-methylaniline was used at the last step (Scheme 1, step d). Compounds 3 to 9 and 4b to 6b were synthesized in 50–89% yield by a one-pot reaction from the commercially available 3-(chlorosulfonyl)benzoyl chloride by following the same procedures (Scheme 1, steps b and c).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of ABT-639 and Compounds 4–11.

Reagents and conditions: (a) oxalyl chloride, CH2Cl2, RT, overnight; (b) (R)-octahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine, Na2CO3, CH2Cl2, RT, 5–18 h; (c) 2-fluoroaniline or other substituted-anilines, RT, overnight; (d) 2-fluoro-N-methylaniline, RT, overnight.

ABT-639 is a selective voltage-dependent Cav3.2 T-type calcium channel blocker. It blocks human T-type (Cav3.2) channels with IC50 = 2.3 μM and also blocks low voltage activated currents in native rat DRG neurons (IC50 = 7.6 μM).18 ABT-639 shows little or no activity at other calcium channels (L-type, N-type, and P/Q-type) and is inactive (IC50 > 10 μM) across a wide array of cell surface receptors and ion channels.18

The pharmacokinetic profile of ABT-639 was evaluated in rat, dog, and monkey, respectively. The data are shown in Table 3. ABT-639 exhibits moderate to low plasma clearance (CLp) ranging from 0.55 L/h/kg in rat to 0.045 L/h/kg in dog. It also demonstrates moderate to low-moderate volume distribution values in these three animal species. The half-life (3.3, 4.9, and 8.3 h) and high oral bioavailability (73, 88, and 95%) in rat, dog, and monkey are in agreement with the liver microsomal stability data (81–100% remaining after 30 min). ABT-639 shows good aqueous solubility of 489 μM in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) and over 9.5 mM in 0.1 HCl solution. In rats, the plasma concentration of ABT-639 was increased proportionally in dose escalation at 30, 100, and 300 mg/kg. ABT-639 has low protein binding (88.9% in rat and 85.2% in human). The brain to plasma concentration ratio was 1:20 in rats. ABT-639 is not a competitive inhibitor of CYP1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4 (IC50 > 10 μM). ABT-639 showed no CYP3A4 (PXR) induction (EC50 > 10 μM) and no CYP1A2 mRNA induction (EC50 > 10 μM).

Table 3. Pharmacokinetic Profile of ABT-639 Across Species.

| species | CLp (L/h/kg) | Vβ (L/kg) | t1/2 (h) | F (%)a | microsomal stability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ratb | 0.55 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 73 | 81 |

| dogc | 0.045 | 0.3 | 4.9 | 88 | 100 |

| monkeyc | 0.11 | 1.35 | 8.3 | 95 | 88 |

Oral formulation: PEG400/cremophor EL/oleic acid (10:10:80, by weight 2 mL/kg).

5 μM/kg iv and 30 μM/kg po.

1 mg/kg iv and po.

ABT-639 dose-dependently attenuates nociception in a capsaicin-induced secondary mechanical hyperalgesia model (Cap-SMH) (Figure 3). The antinociceptive activity of ABT-639 in this model is consistent with its dose-dependent antinociceptive activity in multiple models of neuropathic pain.18,23 Additionally, ABT-639 did not produce any decrement in balance or motor performance in the rat Edge test (ED50 > 300 mg/kg, or rat plasma 114 μg/mL, p.o.). In rat cardiovascular (CV) studies, intravenous administration (i.v.) of ABT-639 yielded negligible changes from vehicle control on mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), left ventricular contractility (dP/dt50), and vascular resistance (VR) at dose of 30 mg/kg (plasma concentration of 43.9 μg/mL).18

Figure 3.

ABT-639 dose-dependently reduces tactile allodynia in the rat Cap-SMH model. ABT-639 was administered 1 h before behavioral testing. Gabapentin (Gaba, 500 μM/kg, i.p.) was included as a positive control for assay sensitivity.

We have described here the discovery of a novel selective T-type calcium channel blocker, ABT-639. Starting from HTS hits 1 and 2 with poor metabolic stability, we replaced the 2-methylindoline with aniline to improve the rat (RLM) and human liver (HLM) microsomal stability. Subsequently, we optimized the new lead 3 by incorporating a novel bicyclic fused diamine. We then introduced the F and Cl atoms to the central aromatic ring to improve the oral bioavailability and metabolic stability, decrease the plasma clearance rate, and increase the half-life (t1/2), and led to discovery of a novel T-type calcium channel blocker ABT-639. ABT-639 displayed good selectivity against N-type, P/Q-type, and L-type calcium channel and hERG channel. ABT-639 has an excellent PK profile with high oral bioavailability in all species. In vivo, ABT-639 dose-dependently reduces nociception in a chronic pain model, with no significant cardiovascular effects at analgesic doses.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- HTS

high throughput screening

- VGCC

voltage-gated calcium channels

- RLM

rat liver microsomes

- HLM

human liver microsomes

- HT-ADME

high throughput-absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- FLIPR

fluorescent imaging plate reader

- EP

electrophysiology

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- PK

pharmacokinetics

Supporting Information Available

Experimental and characterization data for all compounds and the capsaicin-induced secondary mechanical hyperalgesia assay are provided. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00023.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version.

Q.Z., Z.X., S.J., V.E.S., and M.F.J. are employees of AbbVie. The research described herein is solely funded by AbbVie. AbbVie contributed to the study design, research, and interpretation of data.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Catterall W. A. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3 (8), a00394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T.; Takahara A. Recent updates of N-type calcium channel blockers with therapeutic potential for neuropathic pain and stroke. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 377–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern J. G. Targeting N-type and T-type calcium channels for the treatment of pain. Drug Discovery Today 2006, 11, 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H. S.; Cheong E. J.; Choi S.; Lee J.; Na H. S. T-type Ca2+ channels as therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2008, 8, 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravani H.; Zamponi G. W. Voltage-gated calcium channels and idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Physiol. Rev. 2006, 86 (3), 941–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M. T.; Todorovic S. M.; Perez-Reyes E. The role of T-type calcium channels in epilepsy and pain. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12 (18), 2189–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogrul A.; Gardell L. R.; Ossipov M. H.; Tulunay F. C.; Lai J.; Porreca F. Reversal of experimental neuropathic pain by T-type calcium channel blockers. Pain 2003, 105, 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardetti F.; Zamponi G. W. Linking calcium-channel isoforms to potential therapies. Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs 2008, 9, 707–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima T.; Ozono R.; Yano Y.; Higashi Y.; Teragawa H.; Miho N.; Ishida T.; Ishida M.; Yoshizumi M.; Kambe M. Beneficial effect of T-type calcium channel blockers on endothelial function in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 2005, 28 (11), 889–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. Q.; Schlegel K. S.; Shu Y.; Reger T. S.; Cube R.; Mattern C.; Coleman P. J.; Small J.; Hartman G. D.; Ballard J.; Tang C.; Kuo Y.; Prueksaritanont T.; Nuss C. E.; Doran S.; Fox S. V.; Garson S. L.; Li Y.; Kraus R. L.; Uebele V. N.; Taylor A. B.; Zeng W.; Fang W.; Chavez-Eng C.; Troyer M. D.; Luk J. Ann; Laethem T.; Cook W. O.; Renger J. J.; Barrow J. C. Short-acting T-type calcium channel antagonists significantly modify sleep architecture in rodents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1 (9), 504–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa H.; Kondo T. T-type calcium channel as a new therapeutic target for tremor. Cerebellum 2011, 10 (3), 563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa H.; Koh J.; Kajimoto Y.; Kondo T. Effects of T-type calcium channel blockers on a parkinsonian tremor model in rats. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 2011, 97 (4), 656–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. Q.; Barrow J. C.; Shipe W. D.; Schlegel K. A.; Shu Y.; Yang F. V.; Lindsley C. W.; Rittle K. E.; Bock M. G.; Hartman G. D.; Uebele V. N.; Nuss C. E.; Fox S. V.; Kraus R. L.; Doran S. M.; Connolly T. M.; Tang C.; Ballard J. E.; Kuo Y.; Adarayan E. D.; Prueksaritanont T.; Zrada M. M.; Marino M. J.; Graufelds V. K.; DiLella A. G.; Reynolds I. J.; Vargas H. M.; Bunting P. B.; Woltmann R. F.; Magee M. M.; Koblan K. S.; Renger J. J. Discovery of 1,4-substituted piperidines as potent and selective inhibitors of T-type calcium channels. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 6471–6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 117–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E.; Alloui A.; Monteil A.; Barrère C.; Couette B.; Poirot O.; Pages A.; McRory J.; Snutch T. P.; Eschalier A.; Nargeot J. Silencing of the CaV3.2 T-type calcium channel gene in sensory neurons demonstrates its major role in nociception. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagodic M. M.; Pathirathna S.; Joksovic P. M.; Lee W.; Nelson M. T.; Naik A. K.; Su P.; Jevtovic-Todorovic V.; Todorovic S. M. Upregulation of the T-type calcium current in small rat sensory neurons after chronic constrictive injury of the sciatic nerve. J. Neurophysiol 2008, 99, 3151–3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M. T.; Woo J.; Kang H. W.; Vitko I.; Barrett P. Q.; Perez-Reyes E.; Lee J. H.; Shin H. S.; Todorovic S. M. Reducing agents sensitize C-type nociceptors by relieving high-affinity zinc inhibition of T-type calcium channels. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 8250–8260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis M. F.; Scott V. E.; McGaraughty S.; Chu K. L.; Xu J.; Niforatos W.; Milicic I.; Joshi S.; Zhang Q.; Xia Z. A peripherally acting, selective T-Type calcium channel blocker, ABT-639, effectively reduces nociceptive and neuropathic pain in rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 89, 536–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vortherms T. A.; Swensen A. M.; Niforatos W.; Limberis J. T.; Neelands T. R.; Janis R. S.; Thimmapaya R.; Donnelly-Roberts D. L.; Namovic M. T.; Zhang D.; Brent Putman C.; Martin R. L.; Surowy C. S.; Jarvis M. F.; Scott V. E. Comparative analysis of inactivated-state block of N-type (Cav2.2) calcium channels. Inflamm. Res. 2011, 60, 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott V. E.; Vortherms T. A.; Niforatos W.; Swensen A. M.; Neelands T.; Milicic I.; Banfor P. N.; King A.; Zhong C.; Simler G.; Zhan C.; Bratcher N.; Boyce-Rustay J. M.; Zhu C. Z.; Bhatia P.; Doherty G.; Mack H.; Stewart A. O.; Jarvis M. F. A-1048400 is a novel, orally active, state-dependent neuronal calcium channel blocker that produces dose-dependent antinociception without altering hemodynamic function in rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 406–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossetter A. G. A statistical analysis of in vitro human microsomal metabolic stability of small phenyl group substituents, leading to improved design sets for parallel SAR exploration of a chemical series. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 4405–4414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers T.; Leahy D.; Rowland M. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling 1: Predicting the tissue distribution of moderate-to-strong bases. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 1259–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra J.; Jones M.; Sumalla M.; Jarvis M. F. ABT-639, a selective, peripherally acting T-type calcium channel blocker, inhibits spontaneous activity of C-nociceptors in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Soc. Neurosci. 2013, 829, 02/H. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.