Abstract

The natural product aureobasidin A (AbA) is a potent, well-tolerated antifungal agent with robust efficacy in animals. Although native AbA is active against a number of fungi, it has little activity against Aspergillus fumigatus, an important human pathogen, and attempts to improve the activity against this organism by structural modifications have to date involved chemistries too complex for continued development. This report describes novel chemistry for the modification of AbA. The key step involves functionalization of the phenylalanine residues in the compound by iridium-catalyzed borylation. This is followed by displacement of the pinacol boron moiety to form the corresponding bromide or iodide and substitution by Suzuki biaryl coupling. The approach allows for synthesis of a truly wide range of derivatives and has produced compounds with A. fumigatus minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of <0.5 μg/mL. The approach is readily adaptable to large-scale synthesis and industrial production.

Keywords: SAR, antifungal, aureobasidin A, C−H borylation

An increasing number of cancer, transplantation, abdominal surgery, and other immuno-compromised patients that need treatment for fungal infections together with a drug inventory limited to only three classes of therapeutics, all with significant limitations, has created an urgent need for new and better antifungal drugs (e.g., refs (1−3)).

The Aureobasidium pullulans strain BP-1938 produces the cyclic depsipeptide, aureobasidin A (AbA; Scheme 1). This compound is a potent, fungicidal drug that is well tolerated in animals.4 AbA has a mode of action (MoA) that is distinct from all currently used therapeutics. It is a specific, time dependent, inhibitor (Ki ∼ 0.2 nM) of inositol phosphorylceramide (IPC) synthase, an enzyme in the fungal sphingolipid biosynthesis pathway.5,6 IPC synthase is essential in fungi, and attempts to develop spontaneous resistance mutants have to date been unsuccessful, suggesting that development of resistance to AbA, in clinical settings, will be slow.7 Unfortunately, although native AbA is quite active against a number of fungi, including several clinically important pathogens such as Candida spp. and Crytococcus neoformans, it shows little activity against Aspergillus fumigatus, another important pathogen4 that has an efflux pump(s) capable of efficiently clearing the drug.4,8 However, since broad-spectrum antibiotics are preferred in the clinic, this lack of (A. fumigatus) activity has to date prevented the development of AbA into a marketable drug9 and a derivative capable of avoiding or blocking the pump(s) would have significantly improved development potential.

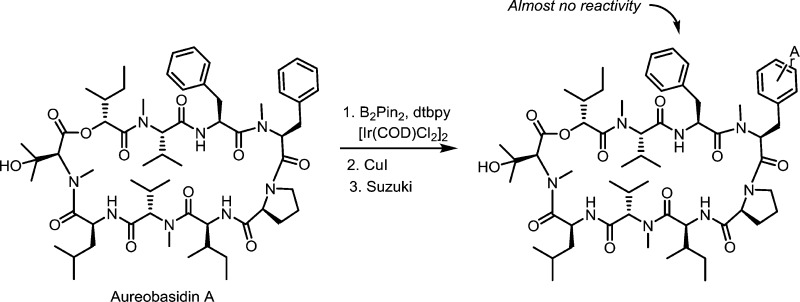

Scheme 1.

Published structure activity relationship (SAR) studies have demonstrated that AbA’s pharmacological properties, including the activity against A. fumigatus, can be altered by modifying and/or exchanging amino acids in the sequence (reviewed in ref (9)). Substitution of an N-methyl-d-Ala, or a sarcosine, for the N-methyl-l-Phe residue at position #4 (in the molecule), results in a compound with significantly improved activity, and combining this substitution with modifications to the side chain of the l-Phe residue in position #3 produces compounds with A. fumigatus MIC values in the low single digit microgram/mL range.9 Importantly, these derivatives retain their potent activities against other fungi. Nonetheless, the complexity and low (<1%) overall yield of the 21 step synthesis used to produce these derivatives have to date represented a considerable barrier against continued development. Several groups have tried to develop more tractable approaches,9 but none has (to date) produced a chemistry compatible with development. This report describes an approach to produce AbA derivatives with A. fumigatus activity that involves no more than three synthesis steps and that currently has overall yields (without any directed effort for improvement) in the 50–70% range.

In a recent report Meyer et al.10 described the specific functionalization of aromatic side chains, such as the Phe residues in AbA by iridium catalyzed borylation. This suggested the possibility of preparing AbA derivatives with improved A. fumigatus activity with just two or three synthetic steps. Nonetheless, at the initiation of the research reported here, it was not known whether this chemistry could be used on a large and complex molecule such as AbA, without modifying other parts of it. It was also not known if one, and if so which, or if both of the phenylalanine side chains in AbA would be modified. X-ray crystallographic data suggested that most of the polar functionalities in the AbA structure are buried in the central core of the molecule and that the side chain on mPhe4 may be more accessible than that on Phe3.9,11

Initial results clearly indicated that the boronate chemistry outlined in Scheme 1 can be applied to the Phe residues in AbA without modifying other parts of the molecule. Silica gel chromatography yielded one well-defined spot, and LC-MS analysis showed that the majority of the reaction products had the mass of native AbA conjugated to one boronate moiety, indicating that one of the Phe residues may be more accessible than the other and that derivatives with both phenyl side chains substituted were formed only to a minor extent (data not shown).

To identify the amino acid(s) functionalized by the borylation reaction, the bromide derivative 3 (prepared from 2; Scheme 1) was hydrolyzed in 12 M hydrochloric acid/TFA (Supporting Information, Scheme S2). The resulting amino acids were converted to the corresponding acetamides, separated on HPLC, and identified by MS and NMR (Supporting Information Figure S1, panels A and B). To allow positive identification of all bromated species in the hydrolysate, authentic standards 8 and 9 were prepared, characterized (by HPLC-MS and NMR), and cochromatographed with the hydrolysis products (Scheme S2). This allowed both identification of the substituted amino acids and determination of the regiochemistry on the substituted phenyl groups. Ninety percent of the brominated amino acids in the hydrolysate were recovered as the brominated N-methyl-Phe isomers 6 and 7 (Figure S1, panel A). Since the phenylalanine residue at position 3 in AbA is not N-methylated, this suggests, consistent with the crystallography data discussed above, that primarily the N-methyl-Phe residue at position 4 was brominated. The vast majority of the remaining 10% of the brominated amino acids was phenylalanine, indicating that a smaller portion of the compound was instead borylated on Phe3. As discussed above, LC-MS analysis of the intact brominated compound suggests <1% of dibrominated AbA (likely modified on both mPhe4 and Phe3). The analysis also revealed that bromine atoms linked to the phenyl group of both amino acids were located in the meta and para positions of the phenyl ring, in a 2-to-1 ratio, suggesting essentially random borylation of these two positions, under the conditions used. Consistent with a sterically driven process, no substitution at the ortho position was found (Figure S1, panels A and B). MS-MS analysis of the intact brominated compound produced three diagnostic fragment ions confirming the preferential borylation of mPhe4 (Data not shown). The preferential borylation of the mPhe4 residue has been a consistent and repeatable result in several experiments, suggesting that the conformation of AbA, in the solvent (hexane/MTBE) used for the borylation reaction, is similar to that adopted upon crystallization and that the reaction is quite specific for mPhe4.

The boronate 2 could be hydrolyzed to the boronic acid 10 without affecting the rest of the molecule. More importantly, however, following substitution of the pinacol boron moiety with bromine or iodine, the resulting halogenated derivatives 3 and 4 can be used as a starting material for the addition of a wide range of larger, more complex structures (biaryls A) to the mPhe4 side chain, using the Suzuki biaryl coupling.12 A large number of the precursor boronic acids required for this type of substitution are available commercially. This allows for extensive SAR work, which was not possible with previous chemistries. The use of the boronate 2 in the Suzuki coupling does give the expected products but since, in general, the boronates are used in excess it was more efficient to convert the boronate 2 to the bromide 3 or iodide 4 and use this in the coupling reaction.

The meta and para isomers could not be separated by silica gel chromatography and were thus used as a mixture in (most of) the biological evaluation of the compounds. Moreover, evaluation of derivatives synthesized to date suggests that the isomeric mixture likely will have sufficient activity to allow development of a clinically useful drug. Currently ongoing development efforts are pursued according to this strategy. However, should a derivative be identified for which separation of the two isomers is considered necessary, or advantageous, this could be accomplished by simulated moving bed (SMB) chromatography. SMB chromatography is readily scaleable.

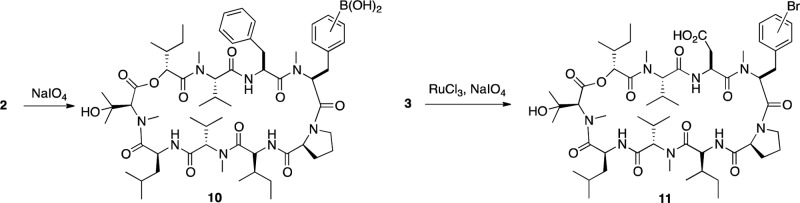

Additional experiments showed that Br-mPhe4-AbA 3 can also be used for selective modification of the Phe3 residue in AbA. RuO4 oxidation13 selectively oxidizes the more electron rich Phe3 group of Br-mPhe4-AbA 3 to give 11 (Scheme 2). Notably, while Phe3 was converted to an aspartic acid, the Br-mPhe4 residue as well as the rest of the AbA molecule remained intact. The correct structure of the Asp3-Br-mPhe4- AbA compound was verified with MS and MS-MS analysis (data not shown). The use of a halogenated AbA derivative as starting material for the generation of novel compounds A (Scheme 1) was verified and to some extent explored by the synthesis of compounds 12 through 30 in Table 1. The coupling with halides 3 or 4 was found to proceed quite efficiently with no side reactions, but using I-mPhe4-AbA 4 instead of Br-mPhe4-AbA 3 in the biaryl coupling gave improved yields of biaryls A.

Scheme 2.

Table 1. In Vitro Activities of AbA Derivatives Synthesized with the Borylation Chemistry.

| MIC (μg/mL) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | Modification | C. albicans | A. fumigatus |

| 1 | AbA (native) | <0.05 | >25 |

| 2 | boronate-mPhe4 | <0.5 | 10 |

| 3 | Br-mPhe4 | 0.031 | 2.5 |

| 4 | I-mPhe4 | 2.5 | >5 |

| 10 | B(OH)2-mPhe4 | <0.05 | >100 |

| 11 | Asp3-Br-mPhe4 | 5 | 10 |

| 12 | 4-MeO-Phe-mPhe4 | 5 | ND |

| 13 | Br-Phe3-Br-mPhe4 | 5 | >100 |

| 14 | Asp3-mAsp4 | 10 | >100 |

| 15 | phenyl-mPhe4 | <0.05 | <0.94 |

| 16 | 5-methyl-furan-1-yl-mPhe4 | ND | >5 |

| 17 | 4-N-methylamino carboxyphenyl-mPhe4 | ND | >5 |

| 18 | 5-methylthiophen-1-yl-mPhe4 | ND | >5 |

| 19 | 5-pyrimid-1-yl-mPhe4 | ND | >5 |

| 20 | 3-pyrid-1-yl-mPhe4 | <0.05 | <0.94 |

| 21 | 1-cyclohexenyl-mPhe4 | ND | >5 |

| 22 | 4-acetamidophenyl-mPhe4 | ND | >5 |

| 23 | 3-Cl-phenyl-mPhe4 | ND | >5 |

| 24 | 1-octene-1-yl-mPhe4 | ND | >5 |

| 25 | 2-Cl-phenyl-mPhe4 | <0.5 | <1.25 |

| 26 | 4-Cl-phenyl-mPhe4 | <0.5 | <2.5 |

| 27 | 4-pyridyl-mPhe4 | <0.025 | <1.25 |

| 28 | 3-biphenyl-mPhe4 | <5 | >5 |

| 29 | 4-biphenyl-mPhe4 | <5 | >5 |

| 30 | 2-chloropyridin-5-yl-mPhe4 | <0.025 | <1.25 |

ND, not determined.

The impact of the modifications discussed above, on the antifungal activity of the respective AbA derivatives, was investigated by determining their antifungal activities against C. albicans and A. fumigatus (Table 1). While the SAR information summarized in ref (9) suggest that both Phe residues in AbA should be modified to gain activity against Aspergillus spp., Table 1 shows that modification of mPhe4 alone provides an alternative approach to accomplish this. It is notable that even the boronate-mPhe4-AbA (Cmpd 2) and Br-mPhe4 -AbA (Cmpd 3) synthetic intermediates exhibited significantly improved A. fumigatus activity, while retaining robust activity against C. albicans and that the improved activity of these compounds was achieved with a completely unmodified Phe3 residue and a retained L configuration at mPhe4. Clearly, AbA derivatives with considerable Aspergillus spp. activity can be generated by modifying the mPhe4 residue only.

Table 1 also shows that comparatively large functionalities can be added to the mPhe4 phenyl group without any deleterious impact on the antifungal activity. Compounds 2, 3, 10, 15, 20, 25, 26, 27, and 30 all retain C. albicans MIC values very close to that of native AbA. By contrast, other modifications, in particular the addition of polar moieties, produced significant increases in C. albicans MIC values. Nonetheless, several of the derivatives synthesized to date have gained significant activity against A. fumigatus. Compounds 15, 20, 25, 26, 27, and 30 are of particular interest because they all retain essentially unaltered activities against C. albicans (MIC values in the sub 50 ng/mL range) while their A. fumigatus MICs have dropped more than an order of magnitude (Table 1). The SAR data reported in ref (9) suggest that adding a hydrophilic (−OH) functionality, to the phenyl ring or to the β-carbon, of the mPhe4 residue on AbA has no impact on the MIC against A. fumigatus, while the MIC against C. albicans remains unchanged (phenyl ring) or increases by about an order of magnitude (β-carbon). A possible explanation for the improved activity of 2 could be that the pinacol portion of the boronate masks the underlying hydrophilic components of the compound. It is notable that the SAR reported in ref (9) indicates that additions of fluorine to the mPhe4 phenol ring, in combination with the same addition to Phe3, do not impact the activity against C. albicans, or improve the activity against A. fumigatus. This suggests that halogenation of Phe3 may counteract the improved A. fumigatus MIC, provided by halogenation of mPhe4, and is consistent with the observation that compound 13 (which is brominated at both Phe3 and mPhe4) has less potency than the wild type compound against both organisms. Still, there is a considerable difference in mass and size between fluorine and bromine and a determination of the MIC values for F-mPhe4-AbA (yet to be made) must be considered essential before any firm conclusions can be made.

The poor performance of compounds 11 and 14, which both contain an Asp residue at position 3, is consistent with previous observations9 that the addition of a hydrophilic functionality at this location increases the C. albicans MIC to >5 μg/mL. The free acid group on the side chain of the mAsp4 residue of 14 further increases the deleterious impact on the antifungal activity. The significantly increased polarity of the side group at position 4 (and/or 3) may influence the compound’s capacity to partition through the cell wall and/or membrane—alternatively it may directly impact the interaction with the target enzyme. Both substrates for IPC synthase are lipids, and the enzyme is an integral membrane protein and as such is located in a very hydrophobic environment.14 It is notable that the methoxy-biphenyl compound (12) lost a considerable amount of activity. The added bulkier side chain on mPhe4 may impact the compound’s interaction with the target enzyme, rather than (or more than) the A. fumigatus drug pump(s). In addition, although the side chain extension on this compound is largely hydrophobic, the methoxy group does add significant hydrogen bonding capacity to the structure

Considering that the overall objective of the SAR studies reported here is to identify an AbA derivative with improved A. fumigatus activity, most of compounds 16 to 30 were evaluated against this organism first and if insufficient improvement was found, the compound was not evaluated further. To date, compounds 15 and 20 clearly have the lowest A. fumigatus MICs. And as can be seen in Table 1, the activities of both compounds against C. albicans are very similar to that of the wild type compound. Nonetheless, of the two, compound 20 appears to provide a more complete eradication of the pathogen cells (in the assays). Consequently, this compound was (tentatively) chosen for a more detailed evaluation against a panel of fungal pathogens. The results, shown in Tables 2 and 3, are in good agreement with the initial evaluation. Compound 20’s MICs against both evaluated A. fumigatus strains are 1–2 μg/mL, i.e. only about one dilution step higher than against the reference strain used in Table 1.

Table 2. In Vitro Activity of Compound 15 against Filamentous Fungi.

| MIC (μg/mL) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | ATCC # | Cmpd 20 | Am Ba |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 20435 | 1 | 0.25 |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | MYA-32626 | 2 | 0.25 |

| Aspergillus flavus | 204304 | 1 | 0.25 |

| Aspergillus flavus | 22546 | 2 | 0.25 |

| Aspergillus flavus | 64025 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Aspergillus candidus | 13686 | 0.008 | 0.03 |

| Aspergillus clavatus | 10058 | 0.03 | 0.004 |

| Aspergillus niger | 16888 | 0.125 | 0.03 |

| Aspergillus niger | 64028 | 0.03 | 0.015 |

| Aspergillus ochraceus | 96919 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Emericella nidulans | 96921 | 0.125 | 1 |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 48112 | >64 | 1 |

| Rhizopus oryzae | 11886 | >64 | 0.03 |

| Sporothrix schenkii | 14284 | >64 | 0.5 |

| Trichophyton mentagrophytes | MYA-4439 | 0.5 | 0.06 |

| Trichophyton mentagrophytes | 28185 | 1 | 0.06 |

| Trichophyton rubrum | MYA-4438 | 2 | 0.03 |

Am B, amphothericin B.

Table 3. In Vitro Activity of Compound 20 against Yeasts.

| MIC (μg/mL) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | ATCC # | Cmpd 20 | Am B |

| Candida albicans | 90028 | 0.015 | 0.03 |

| Candida albicans | 90029 | 0.5 | 0.03 |

| Candida albicans | 10231 | 1 | 0.03 |

| Candida albicans | 204276 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Candida albicans | MYA-2732 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Candida albicans | 24433 | 0.125 | 0.03 |

| Candida guilliermondii | 34134 | 0.03 | 0.008 |

| Candida krusei | 14243 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| Candida lusitaniae | 66035 | 0.125 | 0.015 |

| Candida parapsilosis | 90018 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Candida parapsilosis | 22019 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| Candida glabrata | 90030 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Candida tropicalis | 750 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Candida tropicalis | 90874 | 0.015 | 0.06 |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | 901142 | 0.03 | 0.015 |

| Issatchenkia orientalis | 6258 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 7754 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

Am B, amphothericin B.

Tables 2 and 3 also show that compound 20 has improved activity, against all other evaluated aspergilli, as well as against Crytococcus neoformans (>10×) and Trichophyton spp.,4 while the activity against a range of other fungal pathogens remains similar to that of native AbA.4 In addition, preliminary in vivo data generated with compound 20 suggest a significantly improved plasma half-life, as compared to native AbA.

Since the MIC values of the AbA derivatives described in this report all were obtained using a mixture of the two isomers produced by the borylation reaction, it was of interest to investigate whether individual isomers could differ in their antifungal activities. Thus, MIC values were determined for the purified para and meta isomers of 20 (separated by reverse-phase HPLC; data not shown). This revealed that while the A. fumigatus MIC for the meta isomer was approximately 0.6 μg/mL, the corresponding value for the para isomer was >2.5 μg/mL. Both isomers were equally active against C. albicans. As discussed above, (the degree of) interaction with pumps in A. fumigatus likely is a major contributor to the MIC value against this organism. Analysis of the properties of derivatives synthesized to date suggests that, to acquire significant A. fumigatus activity, substituents added to mPhe4 should overall be hydrophobic, with no or few polar functionalities. This is consistent both with the general properties of the derivatives discussed in ref (9) and with published observations on the apparent substrate specificities of ABC transporters (e.g., refs (15−17)) which suggest that the bulk (size) of added substituents (to a compound) can significantly impact its interaction with (ABC type) pump(s).18 Native AbA is a substrate for MDR pumps, as well as other ABC transporters,9,19,20 and it is notable, that a computational analysis of AbA’s interactions with Pgp-type transporters has revealed that mPhe4 is a key contributor in this regard.21 In addition, experimental work has shown that modifications of residues 3 and 4, alone, can convert AbA from a (human) MDR substrate to a nonsubstrate.22 However, since the specificities of drug pumps, both in A. fumigatus and in general, are only partly understood, the exact reason for the difference (in pump interaction) between the meta and para isomers of 20 is currently not clear. Additional SAR data and/or modeling studies may help clarify this issue.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental details, compound synthesis procedures, and (MIC) assay protocols. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00029.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Basha A.; Basha F.; Ali S. K.; Hanson P. R.; Mitscher L. A.; Oakley B. R. Recent Progress in the Chemotherapy of Human Fungal Diseases. Emphasis on 1,3-Glucan Synthase and Chitin Synthase Inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 4859–4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlin D. S. Resistance to echinocandin-class antifungal drugs. Drug Res. Updates 2007, 10, 121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escribano P.; Recio S.; Peláez T.; González-Rivera M.; Bouza E.; Guinea J. In Vitro Acquisition of Secondary Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus Isolates after Prolonged Exposure to Itraconazole: Presence of Heteroresistant Populations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 174–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takesako K.; Kuroda H.; Inoue T.; Haruna F.; Yoshikawa Y.; Kato I. Biological properties of Aureobasidin A, a cyclic depsipeptide antifungal antibiotic. J. Antibiot. 1993, 46, 1414–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester R. L.; Dickson R. C. Sphingolipids with inositolphosphate-containing head groups. Adv. Lipid Res. 1993, 26, 253–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aeed P. A.; Sperry A. E.; Young C. L.; Nagiec M. M.; Elhammer Å.P. Effect of Membrane Perturbing Agents on the Activity and Phase Distribution of C. albicans Inositol Phosphorylceramide Synthase; Development of a Novel Assay. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 8483–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidler S. A.; Radding J. A. The AUR1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes dominant resistance to the antifungal agent Aureobasidin A (LY295337). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 2765–2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa A.; Hashida-Okado T.; Endo M.; Yoshioka H.; Tsuruo T.; Takeasako K.; Kato I. Role of ABC transporters in Aureobasidin A resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 755–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurome T.; Takesako K. (2000). SAR and potential of the aureobasidin class of antifungal agents. Curr. Opin. Anti-Infect. Invest. Drugs 2000, 2, 375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer F.-M.; Liras S.; Guzman-perez A.; Perreault C.; Bian J.; James K. Functionalization of aromatic amino acids via direct C-H activation: generation of versatile building blocks for accessing novel peptide space. Org. Lett. 2010, 11, 3870–3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In Y.; Ishida T.; Takesako K. Unique molecular conformation of aureobasidin A, a highly amide N-methylated cyclic depsipeptide with potent antifungal activity: X-ray crystal structure and molecular modeling studies. J. Peptide Res. 1999, 53, 492–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A.Metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions; Diedrich, Stang, Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1998; pp 49–97. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen P. H. J.; Katsuki T.; Martin V. S.; Sharpless K. B. A greatly improved procedure for ruthenium tetroxide catalyzed oxidations of organic compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1981, 46, 3936–3938. [Google Scholar]

- Levine T. P.; Wiggins C. A. R.; Munro S. Inositol phosphorylceramide synthase is localized in the Golgi apparatus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 11, 2267–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West I. C. What determines the substrate specificity of the multi-drug-resistance pump?. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1990, 15, 42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K. In search of natural substrates and inhibitors of MDR pumps. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 3, 247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demel M. A.; Krämer O.; Ettmayer P.; Haaksma E. E. J.; Ecker G. F. Predicting ligand interaction with ABC transporters in ADME. Chem. Biodivers. 2009, 6, 1960–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raub T. P-glycoprotein recognition of substrates and circumvention through rational drug design. Mol. Pharmaceut. 2006, 3, 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino K.; Taguchi Y.; Yamada K.; Komano T.; Ueda K. Aureobasidin A an antifungal depsipeptide antibiotic is a substrate for both human MDR1 and MDR2/P-glycoproteins. FEBS Lett. 1996, 399, 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurome T.; Takesako K.; Kato I. Aureobasidins as new inhibitors of P-glycoprotein in multidrug resistant tumor cells. J. Antibiot. 1998, 51, 353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalloum H. M.; Taha M. O. Development of a predictive in silico model for cyclosporine- and aureobasidin-based P-glycoprotein inhibitors employing receptor surface analysis. J. Mol. Graphics Model. 2008, 27, 439–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiberghien F.; Kurome T.; Takesako K.; Didier A.; Wenandy T.; Loor F. Aureobasidins: structure-activity relationships for the inhibition of the human MDR1 P-glycoprotein ABC-transporter. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 2547–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.