Abstract

The potential involvement of intestinal microsomal cytochrome P450 (P450) enzymes in defending against colon inflammation and injury was studied in mice treated with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) to induce colitis. Wild-type (WT) mice and mice with intestinal epithelium (IE)–specific deletion of the P450 reductase gene (IE-Cpr-null) were compared. IE-Cpr-null mice have little microsomal P450 activity in IE cells. DSS treatment (2.5% in drinking water for 6 days) caused more severe colon inflammation, as evidenced by the presence of higher levels of myeloperoxidase and proinflammatory cytokines [tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-1β], and greater weight loss, colonic tissue damage, and colon shortening, in IE-Cpr-null mice than in WT mice. The IE-Cpr-null mice were deficient in colonic corticosterone (CC) synthesis, as indicated by the inability of ex vivo cultured colonic tissues from DSS-treated IE-Cpr-null mice (in contrast to DSS-treated WT mice) to show increased CC production, compared with vehicle-treated mice, and by the ability of added deoxycorticosterone (DOC), a precursor of CC biosynthesis via mitochondrial CYP11B1, to restore ex vivo CC production by colonic tissues from DSS-treated null mice. Intriguingly, null (but not WT) mice failed to show increased serum CC levels following DSS treatment. Nevertheless, cotreatment of DSS-exposed mice with DOC, which did not restore DSS-induced increase in serum CC, abolished the hypersensitivity of IE-Cpr-null mice to DSS-induced colon injury. Taken together, our results strongly support the notion that microsomal P450 enzymes in the intestine play an important role in protecting colon epithelium from DSS-induced inflammation and injury, possibly through increased local CC synthesis in response to DSS challenge.

Introduction

Human inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are chronic and prevalent disorders that involve inflammation and tissue damage in the intestine (Loftus, 2004). Typical clinical symptoms of IBD include loose stools or bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain. Although major advances have been made in the identification of the causes of IBD, which may include genetic, environmental, microbial, and inflammatory factors, the etiology and pathogenic mechanisms of IBD are not fully understood. Given the high prevalence of IBD and the associated enormous health care costs (http://www.cdc.gov/ibd/), efforts to identify modifying factors for IBD risks are important.

Several experimental animal models of chemical-induced colitis have been established to investigate pathogenesis of IBD. One of the most commonly used models involves oral administration of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) to mice. DSS-induced acute colitis in mice displays many symptomatic, morphologic, and pathophysiologic features that are found in human ulcerative colitis, including diarrhea, weight loss, superficial ulceration, mucosal damage, production of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators, and neutrophil infiltration (Cooper et al., 1993; Elson et al., 1995; Vowinkel et al., 2004). Although the mechanism of DSS-induced colitis is not fully understood, direct toxic effects of DSS on colonic epithelium, increased epithelial permeability, macrophage activation, and disruption of colonic microflora have all been suggested as possible explanations (Cooper et al., 1993; Okayasu et al., 2002).

The intestine is recognized as the largest immune organ that protects the host from the constant challenges by ingested pathogens and xenobiotics. There is increasing evidence that the intestinal epithelium (IE) is capable of synthesizing and releasing substantial amounts of glucocorticoids (GCs), which can potently inhibit the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and thus play an important role in the regulation of the immune system (Chrousos, 1995; De Bosscher et al., 2003; Cima et al., 2004). GCs and their synthetic derivatives have been used therapeutically to treat inflammatory diseases, including IBD (Truelove and Witts, 1959).

GC production in the intestine is induced upon immunologic stress, through transcriptional activation of several steroidogenic cytochrome P450 (P450) enzymes, including mitochondrial CYP11A1, CYP11B1, and microsomal CYP21. Previous studies have shown that the protein LRH-1 (liver homologue-1) is a potent regulator of some of these CYP genes in the adrenal glands and ovaries (Fayard et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2005), as well as in the intestine (Mueller et al., 2006). LRH-1 expression is induced upon immune stimulation, coincident with the induction of CYP11A1 and CYP11B1. Lrh-1+/− and Lrh-1vil−/− mice, in which Lrh is deleted either in the whole body, or else specifically in IE, had impaired GC synthesis in the intestine and were hypersensitive to DSS-induced colon inflammation (Coste et al., 2007). The latter results suggested importance of local GC homeostasis in the control of intestinal immunity and the pathogenesis of IBD. These findings prompted us to investigate whether intestinal microsomal P450 activities play a significant role in protection against colon inflammation.

The NADPH-P450 reductase [cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR)] is the essential redox partner for all microsomal P450 enzymes; therefore, deletion of the Cpr gene causes the inactivation of all microsomal P450 enzymes in targeted cells. In the IE-specific Cpr knockout (IE-Cpr-null) mouse model, Cpr is specifically deleted in the enterocytes (Zhang et al., 2009). The null mice were found to be normal in growth, development, and reproduction, and their intestines have normal morphology. Pharmacologic studies revealed deficiencies of the IE-Cpr-null mice in the first-pass metabolism of oral drugs and dietary toxicants (Zhang et al., 2009; Fang and Zhang, 2010; Zhu et al., 2011). Given the known involvement of microsomal P450 enzymes in the synthesis of many endogenous compounds, including GC, we hypothesized that the loss of enterocyte CPR expression will lead to a defect in GC synthesis in the colon, thus predisposing the null mice to the inflammation induced by DSS in colon.

In this study, we compared IE-Cpr-null and wild-type (WT) mice for the extents of DSS-induced colon inflammation and injury. We determined the impact of the CPR loss on DSS-induced changes in serum and colonic corticosterone (CC; the main active form of GC in mice) levels and CC production in colonic explant cultures. We investigated the effects of supplementation with deoxycorticosterone (DOC), a microsomal P450 product and precursor for mitochondrial CYP11B1-mediated CC production, on colonic CC production and DSS-induced colitis in IE-Cpr-null mice. Our results strongly support the hypothesis that intestinal microsomal P450 enzymes play an essential role in protection against DSS-induced inflammation and tissue injury in the colon.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents.

DSS (molecular mass, 36–50 kDa) was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Irvine, CA). Formalin (10% buffered) was from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Myeloperoxidase (MPO) antiserum was from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Western blotting reagents were from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). GCs and standards were obtained from Steraloids (Newport, RI). All solvents (acetonitrile, methanol, and water) were of high-performance liquid chromatography grade (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Animals and Treatments.

All studies with mice were approved by the Wadsworth Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Albany, NY). Adult (2- to 3-month-old, male) IE-Cpr-null (Zhang et al., 2009) mice and age-matched WT littermates were studied. Animals were given free access to food and water. DSS colitis was induced, as described (Okayasu et al., 2002; Coste et al., 2007). Briefly, DSS (w/v, 2.5%) was added to the drinking water; control group received drinking water alone. IE-Cpr-null mice and their WT littermates were exposed to DSS for 6 days. For DOC supplementation, DOC (50 µg/ml) was added (in ethanol) to the drinking water (final concentration of ethanol was 0.1%, w/v). Mice were treated with DSS in combination with DOC for 6 days. Control groups were given DOC or DSS only (both in 0.1% ethanol).

Histopathologic Examination of Inflammation in the Colon.

After 6 days of DSS treatment, the colon was dissected and rinsed with ice-cold saline [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] to remove luminal content; colons were then measured for length. For histopathologic examination, colon tissue was fixed for 24 hours in the shape of a “Swiss roll” in 10% buffered formalin. H&E-stained tissue sections (embedded in paraffin and cut at 4 μm thickness; three per mouse) were prepared, which show the entire length of the colon. Images were obtained at the Light Microscopy Core of the Wadsworth Center. The colon damage was scored according to Ameho criteria (Ameho et al., 1997) at original magnification (100×), using the SPOT imaging software (Sterling Heights, MI).

MPO Level Determination.

Colon mucosa was obtained from both control and DSS-treated animals and was stored at −80°C until thawed for MPO determination. For MPO determination, colon mucosa was homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL); a Kinematica Polytron homogenizer (Littau-Lucerne, Switzerland) was used (3000 rpm for 15 seconds). The homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000g for 15 minutes to pellet cell debris. The supernatant fraction (lysate) was resolved on 10% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies), prior to immunoblot analysis, with a goat polyclonal anti-MPO antibody. Peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-goat IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), and immunoblot quantification was carried out using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS+System (Hercules, CA). Levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were routinely determined as a loading control, with use of a goat anti-GAPDH antibody (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RNA-Polymerase Chain Reaction.

Colon mucosa was processed immediately after dissection for RNA preparation, essentially as described (Zhang et al., 2003). Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed using 2 µg total RNA, as described previously (Zhang et al., 2003). The primers used (Coste et al., 2007) were as follows: TNF-α forward, 5′-gggacagtgacctgcactgt-3′, and reverse, 5′-aggctgtgcattgcacctca-3′; interleukin (IL)-1β forward, 5′-caaccaacaagtgatattctccatg-3′, and reverse, 5′-gatccacactctccagctgca-3′; and IL-6 forward, 5′-gaggataccactcccaacagacc-3′, and reverse, 5′-aagtgcatcatcgttgttcataca-3′. The levels of target gene mRNAs in various total RNA preparations were normalized by the level of GAPDH mRNA in a given sample (with primers 5′-tgtgaacggatttggccgta-3′ and 5′-tcgctcctggaagatggtga-3′).

Determination of Serum and Colonic CC Levels.

Mice were individually housed in a holding room 1 hour before sacrifice, to reduce potential stress caused by other mice in the same cage. The animals were sacrificed quickly, by direct cervical dislocation, to further minimize procedure-induced stress and associated interindividual variations. Blood samples collected through cardiac puncture were used for preparation of sera. Colon mucosa was obtained, as previously described (Zhu et al., 2011). All samples were stored at −80°C until use. CC extraction was performed as described elsewhere (Carvalho et al., 2008). Briefly, each tissue sample was prepared in 3 volumes of a methanol:water mixture (2:1, v/v). Each homogenate (1 ml) was spiked with internal standard (13C2-progesterone, ∼16 µM, 10 µl) and then centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was collected, diluted with 2 ml water, and then purified by solid-phase extraction on Isolute C18 cartridges (200 mg/3 ml; Biotage, Charlottesville, VA). For serum samples, 50 µl serum was mixed with the internal standard and 300 µl methanol; the mixture was spun at 20,000g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was diluted by 0.8 ml water and processed through solid-phase extraction, as described for tissue samples. The C18 cartridges were activated with 3 ml methylene chloride, followed by 3 ml methanol, and then equilibrated with 3 ml water. After loading of the diluted samples, the cartridges were washed with 2 ml water. The analytes, which were eluted sequentially using 1 ml methanol and 1 ml methylene chloride, were pooled and then dried under nitrogen. The residues were reconstituted in methanol (100 µl) for liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis, at atmospheric pressure chemical ionization positive mode (20 µl injection volume).

Method of LC-MS/MS analysis of CC was essentially as previously described (Carvalho et al., 2008). A Phenomenex Luna Phenyl-Hexyl column (3 µm particle size; 2.0 × 150 mm; Torrance, CA) was used, with a mobile phase consisting of solvents A (0.1% formic acid in water) and B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). The column was equilibrated with 30% B for 10 minutes between injections. A linear gradient was developed at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min (30% B, 2 minutes; changing to 90% B, 10 minutes; changing to 100% B, 3 minutes; 100% B, 5 minutes; changing to 30% B, 1 minute). The mass spectrometry conditions were as follows: curtain gas (nitrogen, 30 psi); gas 1 (nitrogen, 50 psi); collision gas (nitrogen, “medium”); nebulizer current (3 μA); gas temperature (500°C); declustering potential (85 V); entrance potential (10 V); collision energy (32 eV); and collision cell exit potential (15 V). The multiple reaction monitoring transitions for the determination of the analytes (m/z 347→121 and 347→97 for CC; m/z 331→97 and 331→107 for DOC; m/z 317→97 and 317→111 for 13C2-progesterone) were based on product-ion spectra of the standards reported previously (Carvalho et al., 2008).

Determination of CC Synthesis in Intestinal Tissue Cultures.

Method for tissue culture was essentially as described (Coste et al., 2007), with minor modifications. Briefly, the entire colon was collected and washed extensively in cold PBS containing 2% steroid-free fetal bovine serum (FBS) to remove the luminal content. Then the colon was opened longitudinally and incubated for 10 minutes in PBS/2% steroid-free FBS containing 1 mM 1,4-dithiothreitol at 4°C to remove the excess mucus. After additional washing in PBS/2% steroid-free FBS, the colon was cut into 5-mm-long segments, which were equally distributed into wells of a 24-well plate (BD Falcon, Brea, CA) and incubated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (with 4.5 g/l glucose and 584 mg/l l-glutamine; Invitrogen) containing 10% steroid-free FBS, at 37°C and 5% CO2. For DOC supplementation in colon explant culture, DOC (100 ng/ml) was added in culture media. In control experiments, 200 μg/ml metyrapone was added to the tissue culture, to block P450-mediated CC synthesis. After a 6-hour incubation, cell-free supernatant was harvested, and CC was extracted and measured using LC-MS/MS, as described above. Results are expressed as the difference between samples cultured with and without metyrapone (Coste et al., 2007).

Other Methods.

Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL), with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Statistical significance of differences between two groups in various parameters was examined using Student's t test, with use of the SigmaStat software (SPSS, Chicago, IL), or two-way analysis of variance, with use of GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Impact of IE-CPR Deficiency on DSS-Induced Colitis.

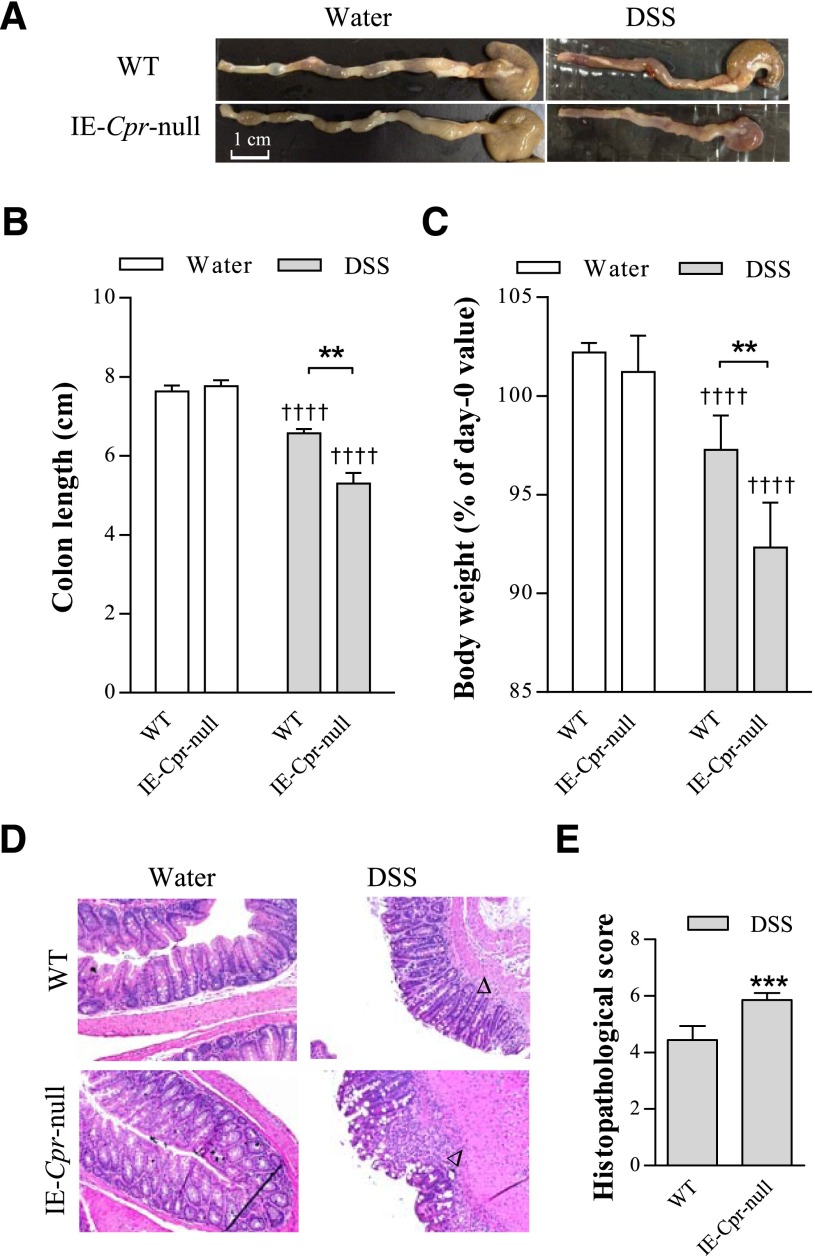

The extent of DSS-induced colon toxicity was assessed by measurements of body weight, colon length, and histologic scoring of the colon damage, and through analysis of colonic expression levels of MPO, an indicator of neutrophil infiltration, and three major proinflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. No difference was found in amounts of liquid consumption either between water and DSS groups, or between WT and IE-Cpr-null mice (data not shown). DSS induced colon inflammation in both mouse strains, evident as significant colon shortening and body weight loss after the 6-day treatment period, compared with water-treated group (Fig. 1, A–C). However, the null mice were more sensitive to DSS-induced colitis. Colons from DSS/IE-Cpr-null group displayed more extensive bleeding (see representative images in Fig. 1A) and colon shortening (by ∼2-fold; Fig. 1B), relative to WT mice; the body weight loss was also significantly greater in IE-Cpr-null mice (by 3-fold; Fig. 1C). There was no difference in either colon length or body weight change between the two mouse strains in the water-treated groups (Fig. 1, B and C). Histopathologic examination of colons from DSS-treated mice showed neutrophil infiltration and loss of epithelial integrity; in contrast, water-treated mice showed normal epithelial structure. The tissue damage was more severe in IE-Cpr-null, compared with WT, mice (see representative images in Fig. 1D), evident by significantly higher histopathologic scores (Fig. 1E), assessed based on the Ameho histopathologic grading scale (Ameho et al., 1997).

Fig. 1.

Induction of colitis by DSS in WT and IE-Cpr-null mice. Mice were treated with DSS (shaded bar) (2.5% [w/v] in drinking water), or water (open bar) alone, for 6 consecutive days. (A) Representative images of the colon from WT and IE-Cpr-null mice after the 6-day DSS or vehicle treatment. Scale bar, 1 cm. (B) Colon length after the 6-day treatment regimen. (C) Extent of body weight loss after the 6-day treatment regimen. Values are relative to weights at day 0 (before DSS treatment). **P < 0.01, compared with WT/DSS; ††††P < 0.0001, compared with corresponding water group; means ± S.D., n = 8–9, two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (D) Histopathologic analysis of DSS-induced colon inflammation. Representative H&E-stained colon tissue sections are shown at 100× magnification for WT and IE-Cpr-null mice, treated with either DSS or water. Signs of DSS-induced inflammation, which was more severe in the null mice, include loss of villi, damage to the submucosa, and infiltration of neutrophil (indicated by arrowheads). (E) Histopathologic score of DSS-induced colitis according to the Ameho criteria, as described in Materials and Methods. ***P < 0.001, compared with WT/DSS mice; means ± S.D., n = 8–9, Student’s t test.

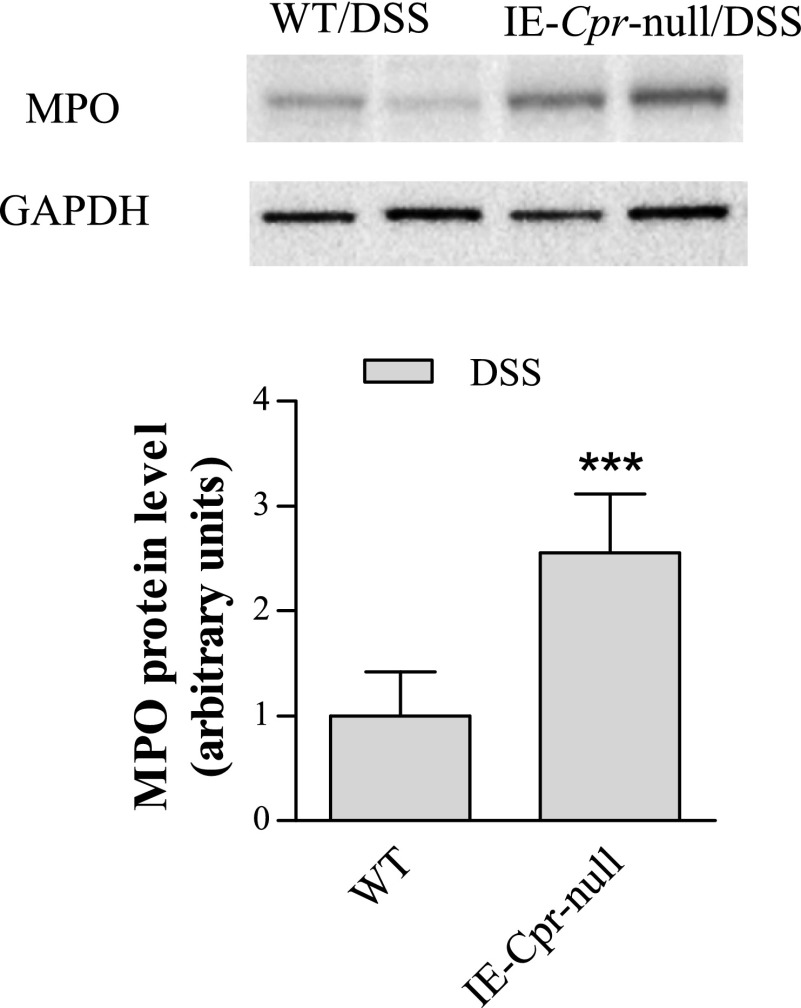

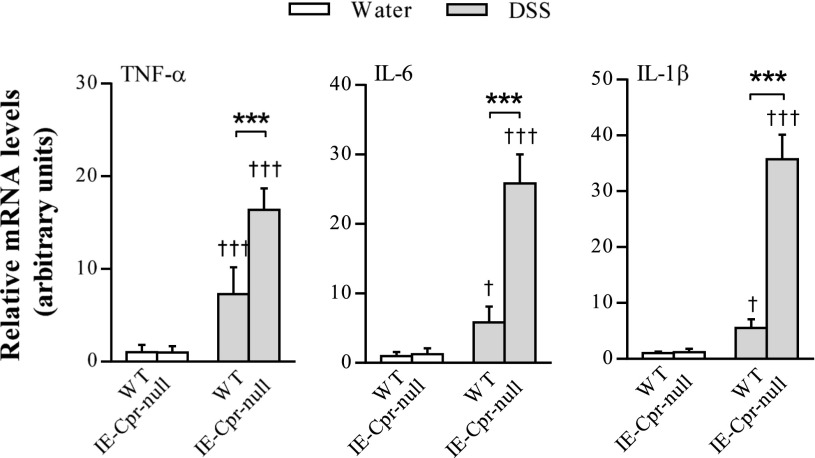

Consistent with the aforementioned increase in colon tissue inflammation, tissue levels of MPO were also significantly higher (by ∼2-fold) in the colons of the null mice, relative to WT mice (Fig. 2), after the 6-day period; MPO expression was below detection limit in water-treated mice (data not shown). Furthermore, mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β were also significantly increased (by 2.3-, 4.4-, and 6.5-fold, respectively) in the colons of IE-Cpr-null mice, relative to WT mice, by the DSS treatment (Fig. 3). Taken together, these data strongly indicate a heightened sensitivity of the null mice to DSS-induced colon inflammation and damage, a result suggesting that colon P450/CPR activity can protect colon epithelium from the inflammation induced by DSS.

Fig. 2.

Immunoblot analysis of MPO expression in colon. WT and IE-Cpr-null mice (2–3 months old, male) were treated with DSS, as described in Fig. 1. Colon epithelial cells were obtained after the 6-day treatment protocol. Aliquots of cell lysates (20 μg protein per lane) were analyzed (in duplicate) on immunoblots, with use of an anti-MPO or anti-GAPDH (loading control) antibody. MPO was not detected in vehicle-treated groups (data not shown). The immunoblots shown represent typical results from three independent experiments. The bar graph shows normalized densitometry results for all experiments (***P < 0.001, compared with WT/DSS mice; means ± S.D., n = 6, Student’s t test).

Fig. 3.

Cytokine levels in colon epithelium of WT and IE-Cpr-null mice after DSS or vehicle administration. Mice were treated with DSS or water, as in Fig. 1. Total RNA samples were prepared from colon epithelium. TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β mRNA levels were determined using polymerase chain reaction, as described in Materials and Methods. The level of GAPDH mRNA was used as an internal control. The results are shown in arbitrary units, with the averaged level in WT/water group being 1. ***P < 0.001, compared with WT/DSS group; †P < 0.05, †††P < 0.001, compared with corresponding water-treated group of the same strain; means ± S.D., n = 5, two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

Impact of IE-CPR Loss on CC Levels In Vivo and CC Production in the Colon Ex Vivo.

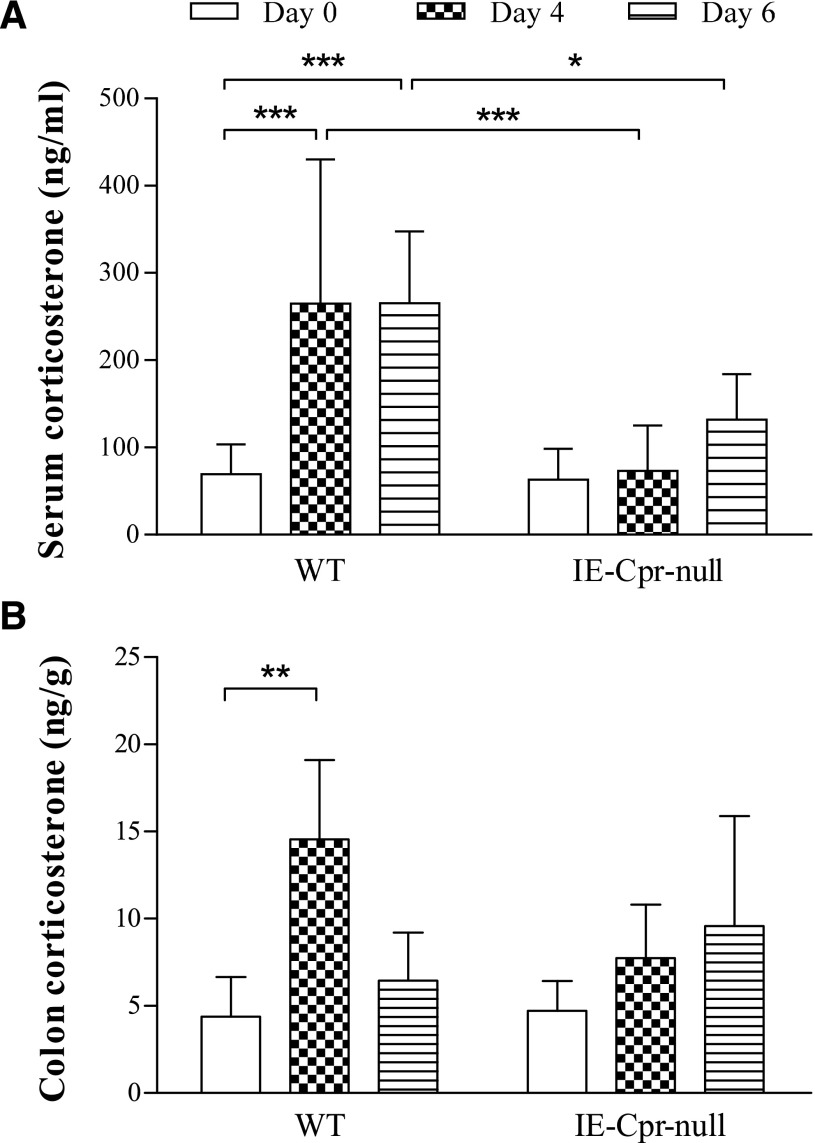

CC levels were determined in mice before and at different times after the onset of DSS treatment. CC levels were similar between WT and null mice before DSS treatment (day 0), in either serum or colon mucosa (Fig. 4). At days 4 and 6, serum CC levels in WT mice were significantly increased (by ∼4-fold), compared with day 0, but these increases were not observed in IE-Cpr-null mice, and the levels in the null mice were significantly lower than in the WT mice (by 50–70%) (Fig. 4A). For colon CC levels, there was a significant increase in WT mice at day 4, although not at day 6, compared with day 0. As was for serum CC levels, a significant increase in colon CC levels was not observed in the null mice at either DSS day 4 or day 6 (Fig. 4B). These results indicated that the null mice did not respond to the oral DSS challenge as strongly as the WT mice did, by increasing serum as well as local GC levels, despite the fact that the colon of the IE-Cpr-null mice sustained greater damage by the DSS treatment, compared with WT mice.

Fig. 4.

CC levels in serum (A) and colon (B) after DSS treatment. CC levels were measured in serum (ng/ml) and colon (ng/g wet tissue weight) for adult male WT and IE-Cpr-null mice before, or 4 or 6 days after, DSS treatment, using LC-MS/MS. Results are shown as means ± S.D. (n = 6–8). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, for comparison groups, as indicated; two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

We further tested the hypothesis that the capacity of the colon to locally produce CC in response to DSS-induced inflammation was decreased by the loss of intestinal P450/CPR activities. Given the fact that the colonic CC levels were much lower than the serum CC levels, and the high probability of contamination of the colon mucosa samples by serum, we wondered whether the measured levels of CC in the colon mucosa samples can be taken to indicate rates of CC production in the colon. Thus, to directly demonstrate dissimilarities between WT and null mice in the capacity of their colons to produce CC, we measured rates of CC synthesis in a colon explant culture system. As shown in Fig. 5, with colons from DSS-treated group, CC production was significantly greater in WT mice than in IE-Cpr-null mice. Furthermore, compared with water-treated group, colonic CC production in the DSS-treated group was significantly increased only in the WT mice, but not in IE-Cpr-null mice. This result strongly supports the conclusion that DSS-stimulated colonic CC production was critically dependent on microsomal CPR/P450 activities and that the capability of the IE-Cpr-null colon to produce CC in response to DSS was compromised.

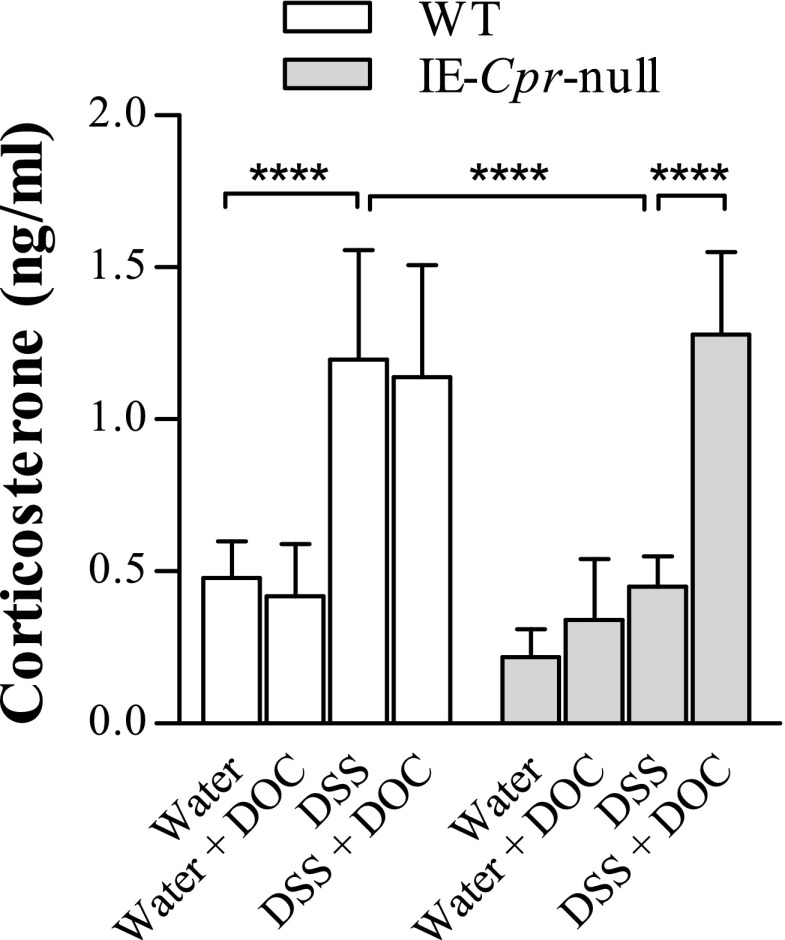

Fig. 5.

CC synthesis in colonic organ cultures from water- or DSS-treated WT and IE-Cpr-null mice. Isolated colon tissue from water- or DSS-treated WT and IE-Cpr-null mice was cultured ex vivo for 6 hours, and CC in the cell-free supernatant was determined using LC-MS/MS, as described in Materials and Methods. For DOC supplementation study, DOC (100 ng/ml) was added in the culture media. Results are shown as means ± S.D. (n = 6–8). ****P < 0.0001, for comparison groups, as indicated; two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

Effects of DOC Supplementation on Colon CC Synthesis Ex Vivo and on DSS-Induced Colitis In Vivo.

The deficiency in colonic CC production in the IE-Cpr-null mice could be a causal factor for the hypersensitivity to DSS-induced inflammation, as the absence of a surge in local CC production may exacerbate DSS-induced local inflammatory response. Thus, we further tested the hypothesis that hypersensitivity of the null mice to DSS-induced colitis is due to impaired local CC production. We reasoned that supplementation with DOC, a precursor used for CC biosynthesis by mitochondrial CYP11B1 (which is not dependent on CPR for activity, and thus still functional in the IE-Cpr-null colon), should be able to restore the capacity of the colon to produce CC, and consequently abolish the hypersensitivity of the null mice to DSS-induced colitis.

The effectiveness of DOC to augment colonic CC production was demonstrated ex vivo. Addition of DOC (100 ng/ml) to colon explant culture media significantly increased CC production in IE-Cpr-null colon and abolished the differences in colonic CC production between WT and IE-Cpr-null mice (Fig. 5). Interestingly, DOC supplementation did not increase CC production in WT colon explant (Fig. 5), a result consistent with the notion that WT colon epithelium has adequate capability to produce DOC (via microsomal CYP21), and thus, excess DOC (at the dose tested) would have little effect on local CC synthesis.

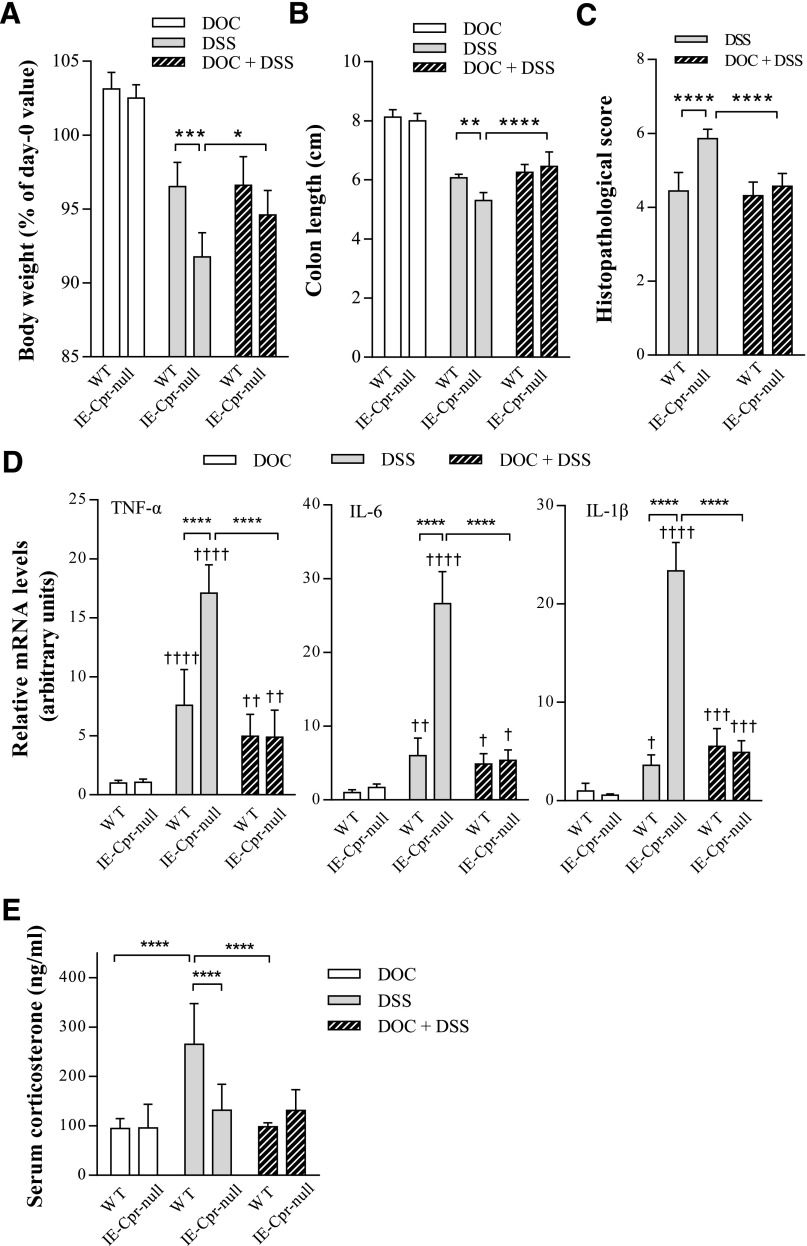

The effects of DOC on DSS-induced colitis were tested in vivo. Mice were treated with DOC in drinking water containing 0.1% ethanol. The addition of ethanol (0.1%) to DOC or DSS, or both, did not alter amounts of liquid consumption or DSS-induced toxicity (based on body weights, colon length), as compared with water-only or DSS (in water)-treated group (data not shown). DOC alone did not cause any abnormalities in either IE-Cpr-null or WT mice, in body weights, colon length, and colon histology. DOC cotreatment did not affect DSS-induced colitis in WT mice, but it abolished the hypersensitivity to DSS-induced colitis in IE-Cpr-null mice, as the differences between DSS-treated WT and DSS-treated IE-Cpr-null mice in body weight, colon length, degree of colon damage, and colonic mRNA levels of the three proinflammatory cytokines all disappeared (Fig. 6, A–D). Interestingly, DOC supplementation did not significantly alter the sensitivity of WT mice to DSS-induced colitis (Fig. 6), consistent with the lack of effect of DOC on colonic CC production (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6.

Effect of DOC supplementation on DSS-induced colitis in WT and IE-Cpr-null mice. Mice were treated with DOC in vehicle (0.1% ethanol in drinking water), DSS in vehicle, or DSS and DOC (50 µg/ml) in vehicle, for 6 days. All parameters were measured after the 6-day treatment regimen. (A) Extent of body weight loss (relative to weights at day 0). Values in all DSS or DOC + DSS were significantly lower than those in DOC/vehicle-treated groups (P < 0.0001). (B) Colon length. Values in all DSS or DOC + DSS groups were significantly lower than those in DOC/vehicle-treated groups (P < 0.0001). (C) Histopathologic score of WT and IE-Cpr-null mice assessed according to Ameho criteria. (D) Colonic cytokine levels. TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β mRNA levels were determined, as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The results are shown in arbitrary units, with the averaged level in WT/DOC group being 1. (E) Serum CC levels. All results are shown as means ± S.D. (A–C) n = 6; (D) n = 5–6; (E) n = 6–7; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, for comparison groups, as indicated. †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01, †††P < 0.001, ††††P < 0.0001; compared with WT/DOC group. All tests were performed using two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

The effects of DOC supplementation on serum CC levels were also determined. DOC treatment alone did not affect serum CC levels, when compared with water-only group (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 6E, DOC supplementation abolished DSS-induced increase in serum CC levels in WT mice, but did not alter serum CC levels in DSS-treated IE-Cpr-null mice.

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that intestinal microsomal CPR/P450 enzymes play a critical role as a protector against DSS-induced colon inflammation and tissue injury. We discovered a hypersensitivity to DSS-induced colon inflammation and tissue injury in IE-Cpr-null mouse model. We confirmed that the loss of microsomal CPR/P450 activities in the intestinal epithelium resulted in reduced production of CC in colon epithelium. Furthermore, we showed that cotreatment of the IE-Cpr-null mouse with DOC, a precursor used for CC biosynthesis by mitochondrial CYP11B1, obliterated its hypersensitivity to DSS-induced colitis. These findings suggest that patients harboring low CPR or microsomal P450 activities in the colon may also have a reduced rate of CC synthesis, and thus may have elevated risks of developing IBD.

The role of intestinal mucosa in the biosynthesis of extra-adrenal GC has been previously recognized (Cima et al., 2004). GC has potent anti-inflammatory properties (Riccardi et al., 2002). Local synthesis of GC in response to immune challenge in the intestine contributes to the maintenance of intestinal immunity (Cima et al., 2004), a notion also supported by results from other studies on mouse models of DSS or 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid–induced colitis (Coste et al., 2007; Noti et al., 2010). Impaired local synthesis of CC in colon, as a result of a deficiency in inducibility of two steroidogenic P450 enzymes (i.e., mitochondrial CYP11A1 and CYP11B1) in a Lrh-1 knockout mouse model, was found to predispose this mouse model to DSS-induced colitis (Coste et al., 2007). Microsomal CYP21 is also involved in GC synthesis, by metabolizing progesterone to DOC; the latter is further converted to CC by CYP11B1. Cyp21 knockout mice had significant reduction in serum CC levels and elevation in progesterone levels (Bornstein et al., 1999). Therefore, it is likely that disruption of intestinal CYP21 function, as would take place in the IE-Cpr-null mice, would also disturb the homeostasis of GCs in the intestine and impact the ability of the intestine to rapidly respond to intestinal inflammation. Notably, the role of microsomal P450 enzymes in the maintenance of intestinal GC homeostasis has not been previously defined. Our finding that CC levels in colon explant were significantly decreased in IE-Cpr-null, compared with WT mice, is definitive evidence that intestinal microsomal P450 are critical in the biosynthesis of GC in the colon.

The utility of the IE-Cpr-null mouse model was critical for demonstrating the involvement of intestinal microsomal P450 enzymes in the defense against DSS-induced colon inflammation. This model was previously used to demonstrate the in vivo influences of small intestinal P450s on the first-pass metabolism of numerous orally ingested drugs, on chemical-induced small intestinal toxicity, and on the systemic exposure of ingested dietary contaminants (Zhang et al., 2009; Fang and Zhang, 2010; Zhu et al., 2011; Zhu and Zhang, 2012). However, the present study is the first use of this mouse model to investigate the role of colon microsomal P450 enzymes in the homeostasis of endogenous compounds and in the regulation of tissue response to chemical-induced inflammation in the colon. The tissue-specific disruption of CPR expression in the enterocytes, which are present in both the small and large intestines, did not lead to any obvious disruption to biologic functions (Zhang et al., 2009). In contrast, it has been recently found that the loss of CPR expression in the enterocytes of IE-Cpr-null mice led to numerous gene expression changes in the small intestine, including upregulation of the major histocompatibility complex class II genes (D’Agostino et al., 2012). Furthermore, IE-Cpr-null mice were prone to acute mucosal damage in the small intestine induced by the ricin toxin, a finding in support of a role of microsomal P450 enzymes in mucosal homeostasis and immunity (Ahlawat et al., 2014). Thus, further studies are needed to define genomic changes in the colon resulting from the loss of CPR expression, to identify potential mechanistic links to the hypersensitivity to DSS-induced toxicity.

CPR is essential for the activities of microsomal P450 enzymes as well as heme oxygenases (HO) (Gu et al., 2003). Although the DOC supplementation experiment (Figs. 5 and 6) clearly demonstrated a major role of microsomal P450 enzymes in the protection of colon against inflammatory injury, our data do not exclude possible involvement of additional mechanisms or pathways, such as intestinal HO activity. Intestinal HO-1 expression was induced by intestinal inflammation in animal models, and increased HO-1 expression was found in colon biopsy from IBD patients (Otterbein et al., 1995; Willis et al., 1996; Paul et al., 2005; Tamion et al., 2007). Preinduction of HO-1 by cobalt protoporphyrin reduced extent of DSS-induced colitis in mice (Paul et al., 2005). However, a protective role of colon HO against IBD has not been definitively proven, as, to date, no tissue-specific knockout/inhibition experiment for colon HO has been reported. Previously, we have observed that, despite the loss of HO activity in IE-Cpr-null enterocytes, there was no decrease in intestinal levels of bilirubin (in unchallenged mice), a heme metabolite that is believed to mediate HO’s protective role, possibly due to compensatory changes in the expression of other genes important for heme homeostasis (D’Agostino et al., 2012). It remains to be determined whether deficit in colonic bilirubin occurs in DSS-treated IE-Cpr-null mice, and, if so, whether supplementation with bilirubin can abolish the heightened sensitivity of these mice to colitis. Notably, DSS induces HO-1 expression in both enterocytes and colonic immune cells (Zhong et al., 2010), whereas the CPR loss in the IE-Cpr-null mice occurs only in enterocytes, but not in immune cells. It is unclear whether HO-1 in enterocytes and HO-1 in other cells and/or tissues (including immune cells that infiltrate the inflamed colon) are both important for the protective role of HO induction against colon inflammation.

Our finding that serum CC levels in the IE-Cpr-null mice failed to increase significantly, as it did in WT mice, on both days 4 and 6 after DSS treatment is intriguing. Serum CC levels mainly reflect CC released from the adrenal glands. The mechanism for the apparently reduced systemic hormonal response to DSS challenge in IE-Cpr-null mice is not yet known, but is unlikely a direct result of the Cpr deletion (and the associated reduction in CC synthesis) in the intestine, given the fact that serum CC levels are much higher than the levels in the intestine. It remains to be determined whether the IE-Cpr-null mouse has adapted to the chronic reduction in intestinal capability to increase CC production in response to luminal bacterial challenge, by decreasing the adrenal hormonal responsiveness to stress signals from the gut, as elicited by the DSS challenge. In that connection, it is unlikely that the relatively lower serum CC levels in DSS-treated IE-Cpr-null mice than in DSS-treated WT mice (Fig. 6) contributed to the hypersensitivity in the null mice, given that the DOC supplementation blocked DSS-induced intestinal injury, but did not affect serum CC levels in the null mice. Similarly, DOC supplementation abolished DSS-induced increase in serum CC levels in WT mice, but did not affect DSS-induced colitis. The reason for the blockage of DSS-induced increase in serum CC levels by DOC in WT mice is unclear. However, given that DOC did not decrease serum CC level in naive WT mice, the effects of DOC in DSS-treated WT mice were unlikely due to a direct interference with CC synthesis.

DOC is normally in very low abundance in the circulation (Porcu et al., 2010) and would not be produced in the intestine of the IE-Cpr-null mice due to the absence of CYP21 activity. Serum DOC was below detection limit in either control or DSS-treated mice in our experiment (data not shown). By supplementing mice with DOC, we bypassed the involvement of microsomal CYP21, to increase local CC production in the intestine. Thus, DOC-supplemented IE-Cpr-null mice would have the capability to increase CC production as in WT mice, upon DSS challenge. Notably, long-term administration of DOC or DOC acetate has been previously used in studies of hypertension and the nervous system in mice and rats (Knowles and Berry, 1978; Weiss and Taylor, 2008). DOC can induce hypertension in adult rats when it is administered in combination with high salt or to animals from the very early phases of life (Dobrović-Jenik and Milković, 1988; Rodriguez-Sargent et al., 1990). In our study, we exposed mice to DOC via drinking water instead of via multiple injections, to minimize handling-derived stress. The dose of DOC used in our study (∼0.3 mg per mouse per day) was similar to those used in previous studies.

In summary, we have demonstrated an important function of colonic microsomal CPR/P450 enzymes in the regulation of colonic GC homeostasis. Our results provide strong support to the hypothesis that intestinal CPR/P450 enzymes protect against DSS-induced toxicity in the colon, by increasing local GC synthesis upon DSS exposure. Our results suggest that further investigations are warranted to identify possible relationships between intestinal CPR/P450 activities and susceptibility to IBD in people.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Nicholas Mantis for helpful discussions, Weizhu Yang for mouse production, and Jun Ma for mouse genotyping. The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of the Histopathology Core and the Advanced Light Microscopy and Image Analysis Core Facilities of the Wadsworth Center.

Abbreviations

- CC

corticosterone

- CPR

cytochrome P450 reductase

- DOC

deoxycorticosterone

- DSS

dextran sulfate sodium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GC

glucocorticoid

- HO

heme oxygenase

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IE

intestinal epithelium

- IL

interleukin

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- P450

cytochrome P450

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- WT

wild-type

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Zhu, Xie, X. Ding, Zhang.

Conducted experiments: Zhu, Xie, L. Ding, Fan, Zhang.

Performed data analysis: Zhu, Xie, Zhang.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Zhu, X. Ding, Zhang.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant R01-GM082978].

References

- Ahlawat S, Xie F, Zhu Y, D’Hondt R, Ding X, Zhang Q-Y, Mantis NJ. (2014) Mice deficient in intestinal epithelium cytochrome P450 reductase are prone to acute toxin-induced mucosal damage. Sci Rep 4:5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameho CK, Adjei AA, Harrison EK, Takeshita K, Morioka T, Arakaki Y, Ito E, Suzuki I, Kulkarni AD, Kawajiri A, et al. (1997) Prophylactic effect of dietary glutamine supplementation on interleukin 8 and tumour necrosis factor alpha production in trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid induced colitis. Gut 41:487–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein SR, Tajima T, Eisenhofer G, Haidan A, Aguilera G. (1999) Adrenomedullary function is severely impaired in 21-hydroxylase-deficient mice. FASEB J 13:1185–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho VM, Nakamura OH, Vieira JG. (2008) Simultaneous quantitation of seven endogenous C-21 adrenal steroids by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry in human serum. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 872:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GP. (1995) The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and immune-mediated inflammation. N Engl J Med 332:1351–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cima I, Corazza N, Dick B, Fuhrer A, Herren S, Jakob S, Ayuni E, Mueller C, Brunner T. (2004) Intestinal epithelial cells synthesize glucocorticoids and regulate T cell activation. J Exp Med 200:1635–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HS, Murthy SN, Shah RS, Sedergran DJ. (1993) Clinicopathologic study of dextran sulfate sodium experimental murine colitis. Lab Invest 69:238–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coste A, Dubuquoy L, Barnouin R, Annicotte JS, Magnier B, Notti M, Corazza N, Antal MC, Metzger D, Desreumaux P, et al. (2007) LRH-1-mediated glucocorticoid synthesis in enterocytes protects against inflammatory bowel disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:13098–13103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino J, Ding X, Zhang P, Jia K, Fang C, Zhu Y, Spink DC, Zhang QY. (2012) Potential biological functions of cytochrome P450 reductase-dependent enzymes in small intestine: novel link to expression of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. J Biol Chem 287:17777–17788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bosscher K, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G. (2003) The interplay between the glucocorticoid receptor and nuclear factor-kappaB or activator protein-1: molecular mechanisms for gene repression. Endocr Rev 24:488–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrović-Jenik D, Milković S. (1988) Regulation of fetal Na+/K+-ATPase in rat kidney by corticosteroids. Biochim Biophys Acta 942:227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson CO, Sartor RB, Tennyson GS, Riddell RH. (1995) Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 109:1344–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang C, Zhang QY. (2010) The role of small-intestinal P450 enzymes in protection against systemic exposure of orally administered benzo[a]pyrene. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 334:156–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayard E, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K. (2004) LRH-1: an orphan nuclear receptor involved in development, metabolism and steroidogenesis. Trends Cell Biol 14:250–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Weng Y, Zhang QY, Cui H, Behr M, Wu L, Yang W, Zhang L, Ding X. (2003) Liver-specific deletion of the NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase gene: impact on plasma cholesterol homeostasis and the function and regulation of microsomal cytochrome P450 and heme oxygenase. J Biol Chem 278:25895–25901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Havelock JC, Carr BR, Attia GR. (2005) The orphan nuclear receptor, liver receptor homolog-1, regulates cholesterol side-chain cleavage cytochrome p450 enzyme in human granulosa cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:1678–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles JF, Berry M. (1978) Effects of deoxycorticosterone acetate on regeneration of axons in the mammalian central nervous system. Exp Neurol 62:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus EV., Jr (2004) Management of extraintestinal manifestations and other complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 6:506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller M, Cima I, Noti M, Fuhrer A, Jakob S, Dubuquoy L, Schoonjans K, Brunner T. (2006) The nuclear receptor LRH-1 critically regulates extra-adrenal glucocorticoid synthesis in the intestine. J Exp Med 203:2057–2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noti M, Corazza N, Mueller C, Berger B, Brunner T. (2010) TNF suppresses acute intestinal inflammation by inducing local glucocorticoid synthesis. J Exp Med 207:1057–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okayasu I, Yamada M, Mikami T, Yoshida T, Kanno J, Ohkusa T. (2002) Dysplasia and carcinoma development in a repeated dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis model. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 17:1078–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein L, Sylvester SL, Choi AM. (1995) Hemoglobin provides protection against lethal endotoxemia in rats: the role of heme oxygenase-1. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 13:595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul G, Bataille F, Obermeier F, Bock J, Klebl F, Strauch U, Lochbaum D, Rümmele P, Farkas S, Schölmerich J, et al. (2005) Analysis of intestinal haem-oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in clinical and experimental colitis. Clin Exp Immunol 140:547–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcu P, O’Buckley TK, Alward SE, Song SC, Grant KA, de Wit H, Leslie Morrow A. (2010) Differential effects of ethanol on serum GABAergic 3alpha,5alpha/3alpha,5beta neuroactive steroids in mice, rats, cynomolgus monkeys, and humans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34:432–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi C, Bruscoli S, Migliorati G. (2002) Molecular mechanisms of immunomodulatory activity of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Res 45:361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Sargent C, Torres-Negron I, Cangiano JL, Martinez-Maldonado M. (1990) Deoxycorticosterone hypertension in the intact weanling rat without salt loading. Hypertension 15:I112–I116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamion F, Richard V, Renet S, Thuillez C. (2007) Intestinal preconditioning prevents inflammatory response by modulating heme oxygenase-1 expression in endotoxic shock model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 293:G1308–G1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truelove SC, Witts LJ. (1959) Cortisone and corticotrophin in ulcerative colitis. BMJ 1:387–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vowinkel T, Kalogeris TJ, Mori M, Krieglstein CF, Granger DN. (2004) Impact of dextran sulfate sodium load on the severity of inflammation in experimental colitis. Dig Dis Sci 49:556–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D, Taylor WR. (2008) Deoxycorticosterone acetate salt hypertension in apolipoprotein E-/- mice results in accelerated atherosclerosis: the role of angiotensin II. Hypertension 51:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis D, Moore AR, Frederick R, Willoughby DA. (1996) Heme oxygenase: a novel target for the modulation of the inflammatory response. Nat Med 2:87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QY, Dunbar D, Kaminsky LS. (2003) Characterization of mouse small intestinal cytochrome P450 expression. Drug Metab Dispos 31:1346–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QY, Fang C, Zhang J, Dunbar D, Kaminsky L, Ding X. (2009) An intestinal epithelium-specific cytochrome P450 (P450) reductase-knockout mouse model: direct evidence for a role of intestinal p450s in first-pass clearance of oral nifedipine. Drug Metab Dispos 37:651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W, Xia Z, Hinrichs D, Rosenbaum JT, Wegmann KW, Meyrowitz J, Zhang Z. (2010) Hemin exerts multiple protective mechanisms and attenuates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 50:132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, D’Agostino J, Zhang QY. (2011) Role of intestinal cytochrome P450 (P450) in modulating the bioavailability of oral lovastatin: insights from studies on the intestinal epithelium-specific P450 reductase knockout mouse. Drug Metab Dispos 39:939–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Zhang QY. (2012) Role of intestinal cytochrome p450 enzymes in diclofenac-induced toxicity in the small intestine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 343:362–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]