ABSTRACT

H3N8 influenza viruses are a commonly found subtype in wild birds, usually causing mild or no disease in infected birds. However, they have crossed the species barrier and have been associated with outbreaks in dogs, pigs, donkeys, and seals and therefore pose a threat to humans. A live attenuated, cold-adapted (ca) H3N8 vaccine virus was generated by reverse genetics using the wild-type (wt) hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) genes from the A/blue-winged teal/Texas/Sg-00079/2007 (H3N8) (tl/TX/079/07) wt virus and the six internal protein gene segments from the ca influenza A virus vaccine donor strain, A/Ann Arbor/6/60 ca (H2N2), the backbone of the licensed seasonal live attenuated influenza vaccine. One dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine induced a robust neutralizing antibody response against the homologous (tl/TX/079/07) and two heterologous influenza viruses, including the recently emerged A/harbor seal/New Hampshire/179629/2011 (H3N8) and A/northern pintail/Alaska/44228-129/2006 (H3N8) viruses, and conferred robust protection against the homologous and heterologous influenza viruses. We also analyzed human sera against the tl/TX/079/07 H3N8 avian influenza virus and observed low but detectable antibody reactivity in elderly subjects, suggesting that older H3N2 influenza viruses confer some cross-reactive antibody. The latter observation was confirmed in a ferret study. The safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine in mice and ferrets support further evaluation of this vaccine in humans for use in the event of transmission of an H3N8 avian influenza virus to humans. The human and ferret serology data suggest that a single dose of the vaccine may be sufficient in older subjects.

IMPORTANCE Although natural infection of humans with an avian H3N8 influenza virus has not yet been reported, this influenza virus subtype has already crossed the species barrier and productively infected mammals. Pandemic preparedness is an important public health priority. Therefore, we generated a live attenuated avian H3N8 vaccine candidate and demonstrated that a single dose of the vaccine was highly immunogenic and protected mice and ferrets against homologous and heterologous H3N8 avian viruses.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza is an important disease in humans and animals. Influenza A viruses can cross the species barriers intact or following reassortment and have the potential to cause devastating pandemics in humans (1). Pandemic preparedness for influenza has generally been focused on highly pathogenic H5 and H7 avian influenza viruses. However, it is impossible to predict when and where an influenza pandemic will appear, how severe it will be, and which subtype of influenza will emerge as a pandemic strain. Several influenza viruses bearing novel viral gene segments from an animal source have arisen in humans and animals. An example of such an event that underscores the need to consider all influenza virus subtypes was the emergence of the novel H1N1 influenza virus in 2009 despite the ongoing circulation of seasonal H1N1 viruses (2).

Avian influenza viruses (AIV) bearing 16 antigenic subtypes of hemagglutinin (HA) and 9 antigenic subtypes of neuraminidase (NA) have been isolated from waterfowl and shorebirds (3, 4), and genetic evidence of H17N10 and H18N11 viruses has been found in bats (5). H3N8 influenza viruses are commonly found in wild birds but are not associated with disease; however, they have been associated with disease outbreaks in dogs (6), horses (7), pigs (8), donkeys (9), and most recently seals (10). Although there have been no known avian H3N8 human cases to date, infections in other mammalian species highlight the ability of this influenza virus subtype to cross the species barriers and establish infection in mammals.

In 2011, an H3N8 AIV, A/harbor seal/New Hampshire/179629/2011 (seal/NH/11), was isolated from seals on the New England coast of the United States (10). This virus contained mutations in the HA gene that are associated with mammalian pathogenicity and that were shown to confer the ability to transmit via respiratory droplets on highly pathogenic avian H5N1 viruses (10–12). In addition, Karlsson et al. have recently shown that the seal/NH/11 virus has increased affinity for α2,6-linked sialic acids, replicates in human lung cells, and transmits via respiratory droplets in ferrets (13).

We had recently analyzed and reported the replicative capacity and the antigenic relatedness of H3N8 avian influenza viruses using postinfection (p.i.) mouse and ferret sera (14). We selected A/blue-winged teal/Texas/Sg-00079/2007 (H3N8) (tl/TX/079/07) virus for vaccine development because it induced the most broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies (Abs) and replicated to a high titer in the upper and lower respiratory tract of mice and ferrets (14). We used reverse genetics to generate a live attenuated, cold-adapted (ca) H3N8 candidate vaccine virus bearing wild-type (wt) HA and NA genes from the tl/TX/079/07 wt virus and the six internal protein gene segments from the ca influenza A master donor virus, A/Ann Arbor/6/60 ca (H2N2) (AA ca). The immunogenicity and protective efficacy against challenge with the homologous and heterologous viruses were evaluated in mice and ferrets. Because the emergence of the seal/NH/11 virus was reported during the course of this study, we included this virus as a heterologous challenge virus in addition to the A/northern pintail/Alaska/44228-129/2006 (H3N8) (npin/AK/06) virus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

H3N8 AIV were provided by Michael Osterholm, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN (tl/TX/079/07), John M. Pearce, U.S. Geological Survey, Anchorage, AK (npin/AK/06), and Hon Ip, U.S. Geological Survey, Wisconsin (seal/NH/11).

The HA amino acid sequence identities between tl/TX/079/07 and seal/NH/11 and npin/AK/06 are 97% and 96.6%, respectively. The A/Hong Kong/1968 (A/HK/68), A/Wuhan/359/1995 (A/WU/95), A/California/7/2004 (A/CA/04), A/Wisconsin/67/2005 (A/WI/05), and A/Texas/50/2012 (A/TX/12) viruses were provided by Hong Jin (MedImmune). The A/Port Chalmers/1973 (A/PC/73) virus was provided by Zhiping Ye (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). The A/Los Angeles/1987 (A/LA/87) virus was provided by Brian Murphy (NIH/NIAID). Virus stocks were propagated in the allantoic cavities of 9- to 11-day-old embryonated specific-pathogen-free hen eggs (Charles River Laboratories, North Franklin, CT) at 35°C. Allantoic fluid was harvested at 72 h postinoculation, tested for hemagglutinating activity using 0.5% turkey red blood cells (Lampire Biological Laboratories, Pipersville, PA), pooled, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until use. Virus titers were determined in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and calculated using the Reed and Muench method (15).

Generation of reassortant tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine virus by reverse genetics.

The HA and NA gene segments of tl/TX/079/07 (H3N8) were amplified from viral RNA (vRNA) by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using “universal” PCR primers for influenza A virus gene segments, sequenced, and cloned into the plasmid vector pAD3000 (16). The 6:2 reassortant vaccine virus was generated by cotransfecting the two plasmids encoding the HA and NA of the tl/TX/079/07 virus and the 6 internal protein gene segments of AA ca into cocultured 293T and MDCK cells. At 3 to 5 days posttransfection, the transfected cell supernatant was inoculated into the allantoic cavity of 10- to 11-day-old embryonated chicken eggs (Charles River Laboratories, Franklin, CT) and incubated at 33°C for 2 days. Virus titer was determined by immunostaining plaques using an anti-nucleoprotein (NP) monoclonal antibody and expressed as log10 PFU/milliliter as previously described (17). The HA and NA sequences of the rescued virus were verified by sequencing the genes amplified from viral RNA by RT-PCR.

Mouse studies.

Six- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice (Taconic Farms, Inc., Germantown, NY) were used in all mouse experiments. Animal studies were conducted in biosafety level 2 laboratories (BSL2) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and protocols were approved by the National Institutes of Health Animal Care and Use Committee. Studies were done once, and 4 mice per group were used.

Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of the H3N8 ca virus.

Groups of eight mice were lightly anesthetized and inoculated intranasally (i.n.) with one or two doses of 106 PFU of the H3N8 ca vaccine virus in 50 μl. Mock-inoculated controls received Leibovitz-15 (L15) medium alone. Serum neutralizing antibody (NtAb) responses to homologous (tl/TX/079/07) and heterologous (npin/AK/06 or seal/NH/11) H3N8 wt viruses were determined prior to inoculation (prebleed) and 38 days after the first or second dose of vaccine by microneutralization (MN) assay (18). The reason for the 38-day interval instead of the conventional 28-day interval was a delay in obtaining the seal/NH/11 virus that we used as a heterologous virus. Briefly, serial 2-fold dilutions of heat-inactivated serum were prepared starting from a 1:20 dilution. Equal volumes of serum and virus were mixed and incubated for 60 min at room temperature. The residual infectivity of the virus-serum mixture was determined in MDCK cells using 4 wells for each dilution of serum. NtAb titer was defined as the reciprocal of the serum dilution that completely neutralized the infectivity of 100 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) of the virus as determined by the absence of cytopathic effect (CPE) on MDCK cells at day 4. A cross-reactive antibody response was defined as a ≤4-fold difference between the homologous NtAb titer and the titer generated against the heterologous virus.

On day 38 after one or two doses of vaccine, groups of eight mice were challenged i.n. with 105 TCID50 of the H3N8 avian wt viruses, tl/TX/079/07, seal/NH/11, or npin/AK/06. Four mice per challenge virus were sacrificed on days 2 and 4 postchallenge (p.c.), and lungs and nasal turbinates (NTs) were harvested and stored at −80°C. We chose these time points based on previous observations that replication of the tl/TX/079/07 and npin/AK/06 wt viruses was detected at moderate to high titers in the lungs of mice from days 2 to 4 after infection (14). Lungs and NTs were weighed and homogenized in L15 medium containing 2× antibiotic-antimycotic (penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin B) (Invitrogen-GIBCO) to make 10% and 5% (wt/vol) tissue homogenates, respectively. Tissue homogenates clarified by centrifugation were titrated on MDCK cell monolayers, and the infectivity was determined by recording the presence of CPE. The dilution at which 50% of the wells were infected (TCID50) was computed using the Reed and Muench method (15), and titers are expressed as log10 TCID50/gram of tissue.

Ferret studies.

Ten- to 12-week-old ferrets (Triple F Farms, Sayre, PA) that were seronegative for hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) antibodies to circulating H3N2, H1N1, and B human influenza viruses were used in the following studies at MedImmune or NIH under protocols approved by the MedImmune and NIH Animal Care and Use Committees. Studies were done once, and 3 ferrets per group were used.

Level of replication of the avian H3N8 wt and ca viruses in the respiratory tract.

Groups of ferrets were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane and inoculated i.n. with 500 μl containing 107 PFU of wt or ca viruses. At days 3 and 5 p.i., ferrets were euthanized and virus titers in the NTs and lungs were determined by immunostaining plaque assay and are expressed as log10 PFU/gram of tissue.

Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of the H3N8 ca virus.

Groups of ferrets were inoculated i.n. with one or two doses, 28 days apart, of 107 PFU of tl/TX/079/07 ca or L15 medium (mock immunized) in 500 μl, and serum samples were collected on day 0 (prebleed), 28, or 56 p.i. Antibody titers in pre- and postvaccination sera were determined by MN assay (18) as described above and by HAI assay according to standard protocols (19). For the HAI assay, nonspecific inhibitors were removed by overnight treatment with receptor-destroying enzyme (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan). By convention, antibody titers were considered significantly different if they differed by more than 4- to 8-fold.

On day 28 or 56 p.i., ferrets were challenged i.n. with 107 PFU of the H3N8 avian wt viruses, tl/TX/079/07, seal/NH/11, or npin/AK/06. On days 3 and 5 p.c., groups of three ferrets were euthanized, and the NTs and lungs (right middle lobe and the caudal portion of the left cranial lobe) were harvested and stored at −80°C. We chose these time points based on previous observations in our laboratory that replication of avian wt viruses was detected at high titers in the NTs and lungs of ferrets from days 1 to 5 after infection (14).

Tissues were homogenized in a 10% (wt/vol) suspension that was clarified by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 10 min and titrated in 24- and 96-well tissue culture plates containing MDCK cell monolayers. Infectivity was determined as described above, and titers are expressed as log10 TCID50/gram of tissue.

Human sera.

Sera from a clinical trial of the monovalent inactivated 2009 pH1N1 vaccine (20), collected in 2009 from healthy adult men and nonpregnant women before vaccination, were provided by John Treanor (University of Rochester). Subjects were enrolled in 3 age cohorts: 18 to 32 years (n = 19), 60 to 69 years (n = 19), and ≥70 years (n = 18). The study was conducted under a protocol approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant.

Antibody response and effect of seasonal H3N2 priming on subsequent infection with tl/TX/079/07 wt virus.

Twenty- to 24-month-old male and female ferrets (n = 6/group) from Simonsen Laboratories (Gilroy, CA) that were seronegative to circulating H3N2, H1N1, and B human influenza viruses were used in this study. The study was conducted at MedImmune, and the protocol was approved by the MedImmune Animal Care and Use Committee.

Groups of six ferrets were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane and inoculated i.n. with 107 TCID50 in a volume of 0.5 ml (0.25 ml per nostril) of one of the following human H3N2 influenza viruses: A/HK/68, A/PC/73, A/LA/87, A/WU/95, A/CA/04, and A/TX/12. Serum samples from experimentally infected animals were collected before and 42 days after infection. Antibody titers were determined by MN and HAI assays as previously described above (18, 19). After 42 days, the ferrets were challenged with a similar dose of tl/TX/079/07 wt virus. On days 2 and 4 p.c., groups of three ferrets were euthanized, and the NTs and lungs were harvested and stored at −80°C. Challenge virus titers were determined in MDCK cells and expressed as log10 TCID50/gram of tissue, as described above.

HA/NA purification and ELISA.

HA and NA from each seasonal H3N2 and the tl/TX/079/07 wt viruses were purified following a previously described protocol (21, 22). Briefly, virus amplified in embryonated eggs was pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm overnight at 4°C and purified on a linear 30 to 60% sucrose gradient in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4). The virus band at the 30 and 60% sucrose interface was collected, pelleted, and resuspended in 1 ml of sodium acetate buffer (0.05 M sodium acetate, 2 nM NaCl, 0.2 nM EDTA [pH 7.0]), and an equal volume of 15% octyl glucoside (1-octyl-n-β-d-glucopyranoside; Sigma) in sodium acetate buffer was added with mild agitation. The HA and NA proteins were separated from the internal core proteins by centrifugation at 19,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant containing the purified HA and NA was collected and stored at −80°C. Purified HA-NA preparations were diluted in carbonate buffer (pH 9.8) and added to 96-well enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates at a concentration of 50 HA units in 50 μl. Control wells were coated with carbonate buffer alone. The plates were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) carbonate buffer and washed three times with PBS-0.05% Tween (PBST). Heat-inactivated sera were serially diluted 4-fold, starting at a 1:20 dilution in 1% BSA carbonate buffer. After incubation for 2 h at 37°C, plates were washed, goat anti-ferret horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-IgG (Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Inc.) was added, and plates were incubated for 2 h at room temperature and washed six times. Subsequently, 100 μl of SureBlue TMB Microwell peroxidase substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) was added and allowed to develop for 10 min. Color development was stopped by adding 100 μl of TMB BlueSTOP solution (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD), absorbance was measured at 650 nm, and wells with an optical density (OD) of >0.2 were considered positive.

RESULTS

One dose of tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine candidate was highly immunogenic and protected mice against challenge with homologous and heterologous H3N8 avian viruses.

The immunogenicity of the tl/TX/079/07 ca virus was evaluated in mice following 1 or 2 doses. A single dose of tl/TX/079/07 ca induced a robust NtAb response against the homologous virus, with a geometric mean titer (GMT) of 387 (range of 202 to 1,016). The GMT against the heterologous seal/NH/11 virus was 113 (range of 28 to 320) and against the npin/AK/06 virus was 132 (range of 57 to 403). When two doses of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine were administered to mice, the GMT against the homologous virus was 199 (range of 57 to 403) 28 days following the first dose, with a further increase after the second dose (GMT of 1,335; range of 226 to 3,225) (Table 1). The GMT against the heterologous seal/NH/11 virus was 88 (range of 57 to 226) after the first dose of vaccine and 596 (range of 160 to 905) after the second dose. A similar profile was observed against the heterologous npin/AK/06 virus (Table 1). As expected, mock-immunized mice did not develop detectable NtAb. These results demonstrate that the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine candidate is highly immunogenic in mice, and serum antibodies cross-reacted well with the heterologous viruses.

TABLE 1.

Immunogenicity of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine in micea

| Test antigen used in MN assay | GMT of serum NtAb achieved at indicated day(s) postimmunization in miceb |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 dose (day 38) | 2 doses (days 28/66) | |

| tl/TX/079/07 | 387 | 199/1,335 |

| seal/NH/11 | 113 | 88/596 |

| npin/AK/06 | 132 | 82/434 |

Groups of eight mice were inoculated i.n. with 106 PFU of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine. Sera were collected on the indicated days after immunization. Homologous antibody titers are in bold.

Mice were bled on day 38 after the first and second immunizations because there was a delay in obtaining the seal/NH/11 virus.

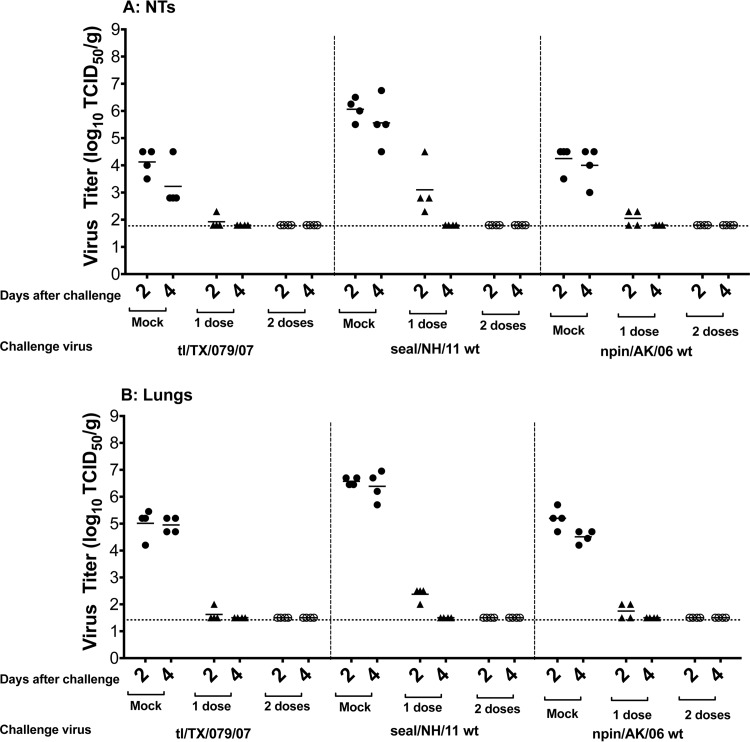

To determine whether immunization with one or two doses of the tl/TX/079/07 ca virus induced protection, vaccinated mice were challenged with 106 PFU of the homologous (tl/TX/079/07) or heterologous (seal/NH/11 or npin/AK/06) wt viruses. The mean virus titers on days 2 and 4 p.c. in the NTs of the mock-immunized mice challenged with the tl/TX/079/07 wt were 104.1 and 103.2 TCID50/g, respectively, and the mean virus titers in the lungs were 105.0 and 104.9 TCID50/g on days 2 and 4 p.c., respectively. The mean virus titers on days 2 and 4 p.c. in the NTs of mock-immunized mice challenged with the heterologous seal/NH/11 and npin/AK/06 wt viruses were 106.1 and 105.6 and 104.2 and 104.0 TCID50/g, respectively, and the mean virus titers in the lungs were 106.6 and 106.4 and 105.2 and 104.5 TCID50/g on days 2 and 4 p.c., respectively (Fig. 1). A single dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca virus provided near-complete protection against challenge with homologous virus (only one mouse out of four had detectable virus on day 2 p.c.) in both the upper and lower respiratory tracts (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Protection conferred by the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine against homologous and heterologous challenge in the upper (A) or lower (B) respiratory tracts of mice. Animals were intranasally inoculated with either L15 (mock) or 1 or 2 doses of 106 PFU/mouse of tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine and challenged 38 days following the last vaccine dose with 106 PFU/mouse of the indicated challenge virus. Virus titers were determined on days 2 and 4 postchallenge. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (unpaired t test). Vaccinated groups had a statistically significant reduction in virus titers of the homologous (P < 0.003) and heterologous H3N8 (P < 0.005) viruses in the NTs and lungs, compared to the titers in the mock-immunized group. The dashed horizontal line represents the lower limit of detection.

Mice that received one dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine and were challenged with the heterologous seal/NH/11 wt virus had mean virus titers of 103.1 and 102.4 on day 2 p.c. in the NTs and lungs, respectively, and challenge virus was completely cleared by day 4. Mice challenged with npin/AK/06 wt virus had low titers (102.3 TCID50/g) of challenge virus (two out of four mice) on day 2, and challenge virus was completely cleared by day 4 p.c., in both the upper and lower respiratory tracts. As expected, two doses of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine conferred complete protection against all three challenge viruses.

Thus, the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine was highly immunogenic and offered robust protection against challenge with homologous and heterologous avian H3N8 viruses.

One dose of tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine candidate was attenuated, highly immunogenic, and protected ferrets against challenge with homologous and heterologous H3N8 avian viruses.

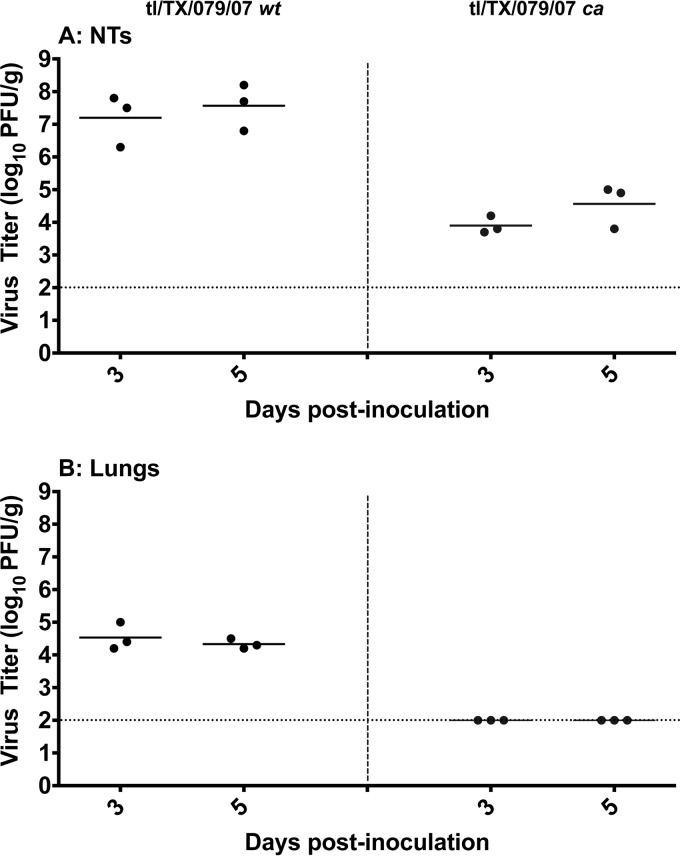

Preclinical assessment of attenuation of vaccines on the AA ca backbone is conducted in ferrets by comparing clinical signs of disease and the level of replication of the wt and corresponding ca viruses in the NTs and lungs. Clinical signs of disease were not observed in ferrets infected with the tl/TX/079/07 ca or wt viruses. The mean titers of the tl/TX/079/07 wt virus on days 3 and 5 p.i. were 107.2 and 107.6 PFU/g, respectively, in the NTs, and the corresponding titers of the tl/TX/079/07 ca virus were 103.9 and 104.6 PFU/g (Fig. 2). We have observed similar kinetics of replication with an equine H3N8 live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) candidate (23). The mean titers of the tl/TX/079/07 wt virus on days 3 and 5 were 104.5 and 104.3 PFU/g, respectively, in the lungs, while replication of the tl/TX/079/07 ca virus was not detected in the lungs, presumably because these temperature-sensitive viruses are restricted in replication at the core body temperature of ferrets. These data confirm that the inclusion of the 6 internal protein genes of the AA ca virus attenuate the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine reassortant.

FIG 2.

Level of replication of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine virus compared with the corresponding wt virus in the upper (A) and lower (B) respiratory tracts of ferrets. Lightly anesthetized ferrets were inoculated intranasally with 107 PFU/ferret, and tissues were harvested on days 3 and 5 postinfection. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (unpaired t test). tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine had a statistically significant reduction in virus titers in the NTs (P < 0.006) and lungs (P ≤ 0.0005) compared to the titers in the wt group. The dashed horizontal line represents the lower limit of detection.

NtAb or HAI antibodies were not detected in ferrets prior to vaccination or following mock vaccination. All animals that received a single dose of tl/TX/079/07 ca virus developed NtAb and HAI Ab to the homologous wt virus at titers that ranged from 226 to 640 (GMT of 357) and from 40 to 320 (GMT of 148), respectively. The tl/TX/079/07 ca virus also elicited cross-reactive NtAb and HAI Ab to the heterologous seal/NH/11, with titers ranging from 113 to 806 (GMT of 298) and from 80 to 320 (GMT of 173), respectively (Table 2). Cross-reactive NtAb and HAI Ab to the heterologous npin/AK/06 wt virus were lower, at 195 (range of 63 to 640) and 50 (range of 40 to 80), respectively.

TABLE 2.

Immunogenicity of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine in ferretsa

| Test antigen used in serological assay | Assay | GMT of serum HAI or NtAb achieved at indicated day(s) postimmunization |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 dose (day 28) | 2 doses (days 28/56) | ||

| tl/TX/079/07 | MN | 357 | 278/700 |

| HAI | 148 | 83/113 | |

| seal/NH/11 | MN | 298 | 259/595 |

| HAI | 173 | 52/66 | |

| npin/AK/06 | MN | 195 | 42/366 |

| HAI | 50 | 25/54 | |

Groups of 12 ferrets were inoculated i.n. with 107 PFU of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine. Sera were collected at the indicated days after immunization. Homologous antibody titers are in bold.

When two doses of vaccine were administered 28 days apart, the first dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine induced a homologous and heterologous NtAb and HAI Ab response consistent with the data described above. The second dose induced a further increase in homologous Ab titer, to GMTs of 700 (range of 226 to 2,032) and 113 (range of 80 to 160), respectively. The second dose of vaccine also induced a boost in NtAb and HAI Ab to the heterologous seal/NH/11 virus, to GMTs of 595 (range of 160 to 1,810) and 66 (range of 20 to 160), respectively, as well as to the heterologous npin/AK/06 virus, to GMTs of 366 (range of 202 to 806) and 54 (range of 20 to 160) (Table 2).

Similar to the study in mice, these data indicate that a single dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca virus was immunogenic in ferrets and elicited serum antibodies that cross-reacted with heterologous avian H3N8 viruses.

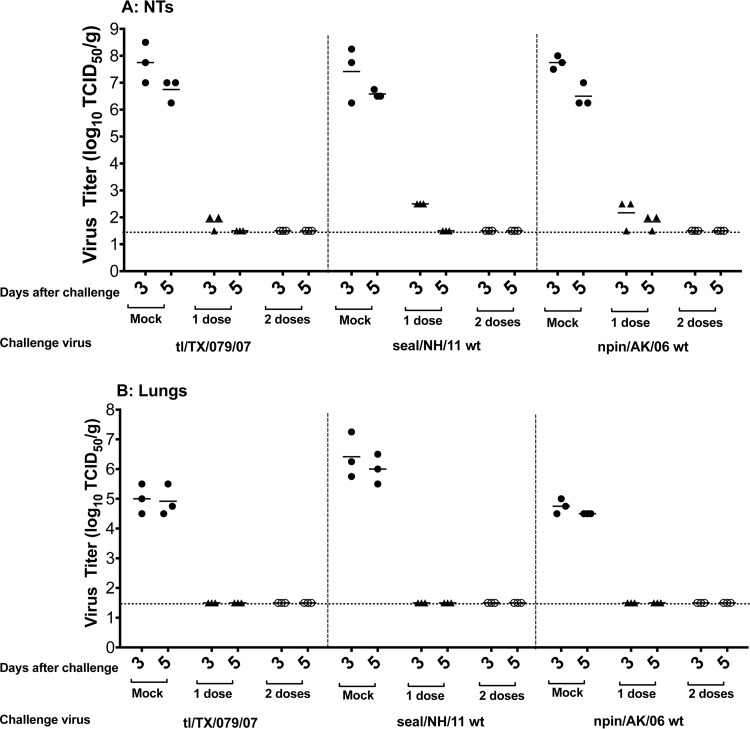

To evaluate the protective efficacy of the tl/TX/079/07 ca virus in ferrets, we vaccinated animals with one or two doses of the vaccine and challenged them 28 days later with 107 PFU of the homologous (tl/TX/079/07) or the heterologous (seal/NH/11 and npin/AK/06) wt viruses. The mean titers of the tl/TX/079/07 wt challenge virus on days 3 and 5 p.c. in mock-immunized ferrets were 107.7 and 106.7 TCID50/g, respectively, in the NTs, and 105.0 and 104.9 TCID50/g, respectively, in the lungs.

The corresponding mean titers of the heterologous seal/NH/11 wt virus in mock-vaccinated ferrets were 107.4 and 106.6 TCID50/g, respectively, in the NTs, and 106.4 and 106.0 TCID50/g, respectively, in the lungs. The corresponding mean titers of the heterologous npin/AK/06 wt virus in the NTs of mock-vaccinated ferrets were 107.7 and 106.5 TCID50/g, respectively, and 104.7 and 104.5 TCID50/g, respectively, in the lungs (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Protection conferred by the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine against homologous and heterologous challenge in the upper (A) and lower (B) respiratory tracts of ferrets. Animals were intranasally inoculated with either L15 (mock) or 1 or 2 doses of 107 PFU/ferret of tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine and challenged 28 days following the last vaccine administration with 107 PFU/ferret of the indicated challenge virus. Virus titers were determined on days 3 and 5 postchallenge. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (unpaired t test). Vaccinated groups had a statistically significant reduction in virus titers of the homologous (P ≤ 0.0003) and heterologous (P < 0.0004) H3N8 viruses in the NTs and lungs, compared to the titers in the mock-immunized group. The dashed horizontal line represents the lower limit of detection.

A single dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine provided nearly complete protection against replication of the homologous challenge virus in the upper respiratory tract (two out of three ferrets had 102.0 TCID50/g on day 3 p.c., and challenge virus was completely cleared by day 5) (Fig. 3A). In the lungs, one dose of the vaccine conferred complete protection on day 3 p.c. (Fig. 3B). Ferrets that received one dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine and were challenged with the heterologous seal/NH/11 wt virus had a low titer of challenge virus in the upper respiratory tract (102.5 TCID50/g) on day 3, with complete clearance on day 5 p.c. (Fig. 3A) and no detectable replication of the challenge virus in the lungs (Fig. 3B).

Ferrets that received one dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine and were challenged with the heterologous npin/AK/06 wt virus had low titers (means of 102.2 and 101.8 TCID50/g) of challenge virus in the upper respiratory tract at both time points, and the vaccine completely prevented replication of the npin/AK/06 wt virus in the lungs.

Consistent with these data, two doses of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine conferred complete protection from replication of the three challenge viruses in the upper and lower respiratory tract of ferrets.

In summary, one dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine virus offers very robust protection against challenge with homologous and heterologous avian H3N8 viruses in ferrets.

Presence of cross-reactive antibodies in sera from humans older than 60 years of age.

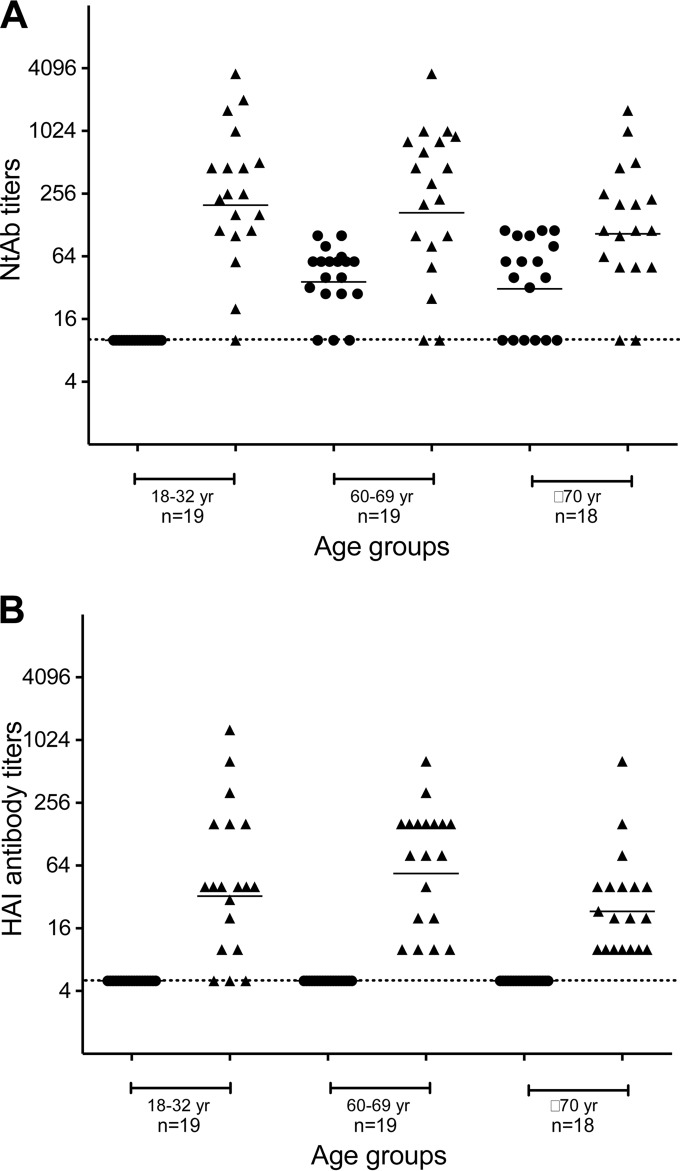

As human H3N2 viruses have been circulating since 1968, we were interested in determining whether prior exposure to seasonal H3N2 viruses induced cross-reactive Ab against the avian H3N8 virus. We assessed the presence of antibodies that cross-reacted with tl/TX/079/07 (H3N8) virus in human sera collected in 2009. As a control, we assayed the levels of antibodies against the seasonal influenza virus A/Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2) that was circulating at the time the sera were collected. Subjects from three age groups, 18 to 32 years old (n = 19), 60 to 69 years old (n = 19), and 70 years or older (n = 18), were enrolled in a clinical trial of a monovalent 2009 H1N1pdm vaccine that has been reported previously (20).

The 18- to 32-year-old subjects failed to show detectable NtAb against the avian H3N8 virus (Fig. 4A). However, subjects from the other two cohorts, 60 to 69 and ≥70 years old, had a GMT of 39 (range of 10 to 101) and 36 (range of 10 to 113), respectively. Specifically, in subjects older than 60 years of age (n = 37), nine had NtAb titers between 28 and 40, 12 between 57 and 80, and seven between 101 and 113. In total, 28 out of 37 (76%) individuals had NtAb titers of ≥20 against the avian H3N8 virus. We did not enroll subjects who were between 33 and 59 years of age in the study, so we cannot comment on the level of cross-reactive antibody in this age group. However, the study was conducted from 2009 to 2010, and therefore subjects born after 1968, when H3N2 viruses emerged and became established in humans, would have been 42 years of age or younger. Therefore, we would expect that people over 42 years of age would have been exposed to H3N2 viruses and could have some cross-reactive antibody. We recently reported (23) that the GMTs in the 18- to 32-year-old, 60- to 69-year-old, and ≥70-year-old subjects against the A/Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2) virus were 248 (range of 10 to 3,620), 223 (range of 10 to 3,620), and 129 (range of 10 to 1,613), respectively (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Serum neutralizing antibody (A) and hemagglutination inhibiting antibody (B) titers in individuals of different age groups. The serum antibody titers against tl/TX/079/07 (circles) and A/WI/67/05 (triangles) are shown for individual subjects. Bars identify geometric mean titers of the group. The dashed horizontal line represents the lower limit of detection.

Interestingly, none of the subjects had detectable HAI antibodies against the avian H3N8 virus (Fig. 4B). The GMTs of HAI antibodies in the 18- to 32-year-old, 60- to 69-year-old, and ≥70-year-old subjects against the A/Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2) virus were 46 (range of 5 to 1,280), 67 (range of 5 to 640), and 27 (range of 10 to 640), respectively (Fig. 4B). The detection of cross-reactive NtAb in the absence of HAI antibodies in 76% of subjects over 60 years of age suggests that the antibody was induced by prior or repeated exposure by infection with and/or vaccination against older seasonal H3N2 viruses and that the Abs could be directed at the HA stalk.

Ferrets primed with seasonal H3N2 viruses from 1968 to 2012 were nearly completely protected against challenge with the H3N8 avian tl/TX/079/07 virus.

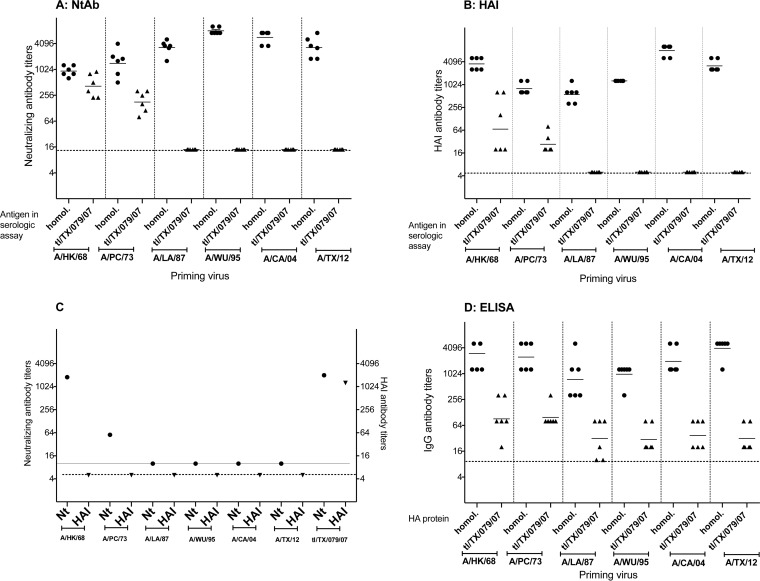

We explored the ability of previously circulating seasonal human H3N2 influenza viruses from different decades to induce cross-reactive antibodies and protection against the tl/TX/079/07 virus by infecting ferrets and testing their sera on day 42 p.i. in MN and HAI assays and ELISAs. The H3N2 viruses that we selected circulated during the 1960s (A/HK/68), 1970s (A/PC/73), 1980s (A/LA/87), 1990s (A/WU/95), 2000s (A/CA/04), and 2010s (A/TX/12). Sera from ferrets infected with the tl/TX/079/07 virus in a previous study (14) served as a positive control. The results are presented in Fig. 5. The ferrets were seronegative to influenza by HAI and MN assay prior to infection. Very low IgG ELISA antibody titers were detected in the prebleed sera (GMT range of 10 to 18) due to nonspecific binding to the ELISA plates. Ferrets achieved high postinfection homologous Ab titers by all assays (Fig. 5A, B, and D). Cross-reactive antibodies were detected only in the sera from ferrets infected with A/HK/68 and A/PC/73 viruses, with GMTs of 427 and 183 by MN assay and 90 and 28 by HAI assay, respectively. In the reciprocal assay, postinfection ferret antiserum against the tl/TX/079/07 virus cross-reacted with A/HK/68 and A/PC/73 by MN assay. However, the postinfection tl/TX/079/07 ferret serum did not show HAI activity against any of the seasonal H3N2 viruses (Fig. 5C). By ELISA, we detected a 4-fold rise in cross-reactive IgG antibody titer against the tl/TX/079/07 virus in sera from ferrets infected with A/HK/68 and A/PC/73 viruses (GMT of 101). Lower titers of ELISA Ab were detected in sera from ferrets infected with A/LA/87, A/WU/95, A/CA/04, and A/TX/12 viruses, with GMTs of 32, 32, 40, and 32, respectively (Fig. 5D).

FIG 5.

Serum neutralizing antibody titers (A), hemagglutination inhibiting antibody titers (B), and IgG ELISA antibody titers (D) detected in sera from ferrets infected with seasonal human H3N2 influenza viruses from different decades. Groups of six ferrets were inoculated i.n. with 107 TCID50 of the indicated H3N2 seasonal influenza viruses. Sera were collected 42 days postinoculation. Neutralizing or hemagglutination inhibiting antibody titers (C) in the serum from a ferret infected with the tl/TX/079/07 wt virus against each of the H3N2 seasonal influenza viruses. Bars represent the geometric mean titers of the group. The dashed horizontal line represents the lower limit of detection for each assay.

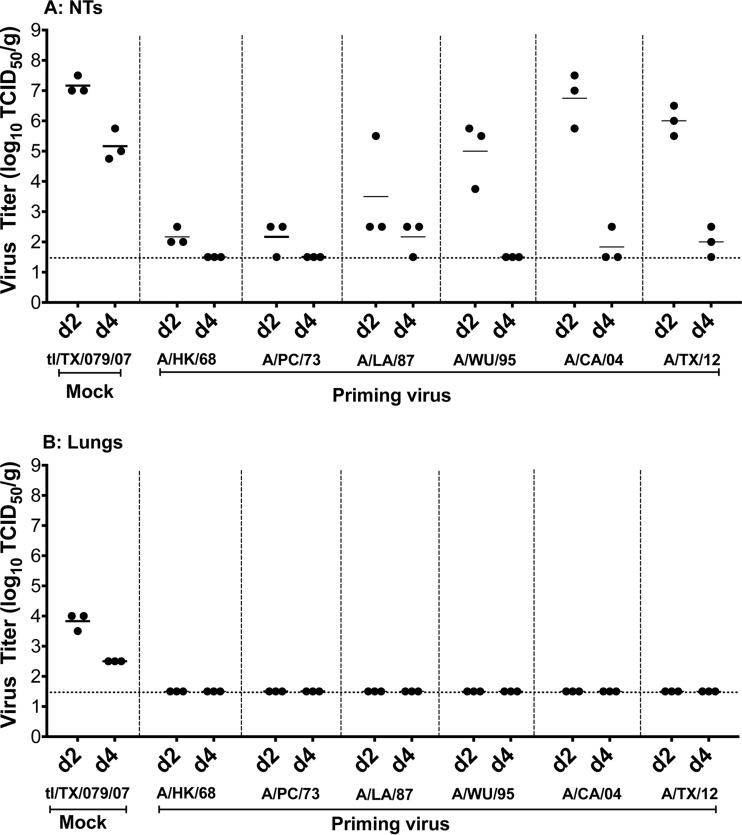

The effect of prior H3N2 virus infection on replication of the tl/TX/079/07 virus was evaluated by challenging ferrets that had been infected with seasonal H3N2 influenza viruses 6 weeks earlier. The ferrets did not show any clinical signs of influenza virus infection after primary or challenge infection. Primary infection with the seasonal A/HK/68 and A/PC/73 viruses provided robust protection from challenge with tl/TX/079/07 in the upper respiratory tract, with low virus titers on day 2 p.c. that were cleared by day 4 (Fig. 6A). Mean challenge virus titers in the NTs on day 2 p.c. in ferrets primed with seasonal H3N2 viruses A/LA/87, A/WU/95, A/CA/04, and A/TX/12 were 103.5, 105.0, 106.75, and 106.0, respectively, and virus was nearly or completely cleared by day 4 p.c. Although the replication of the challenge virus in the lungs of ferrets was modest (103.7 and 102.5 on days 2 and 4 p.c., respectively), presumably because the ferrets were older than those shown in Fig. 3, pulmonary virus replication was not detected in ferrets primed with any of the seasonal H3N2 influenza viruses (Fig. 6B). In summary, the data suggest that prior infection with seasonal H3N2 influenza viruses protects ferrets against tl/TX/079/07 infection.

FIG 6.

Replication of tl/TX/079/07 wt virus in ferrets previously primed with the indicated seasonal human H3N2 influenza viruses from different decades. Animals were intranasally inoculated with either L15 (mock) or one of the H3N2 influenza viruses. On day 42 postpriming, ferrets were challenged with the tl/TX/079/07 wt virus, and nasal turbinates (A) and the lungs (B) were harvested and virus titers were determined on days 2 and 4 postchallenge (p.c.). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (unpaired t test). Animals primed with A/HK/68 and A/PC/73 had a statistically significant reduction in virus-challenged titers in the NTs (P ≤ 0.0001) on day 2 p.c., compared to the titers in the nonprimed animals. The P values for the animals primed with A/LA/87, A/WU/95, A/CA/04, and A/TX/12 were 0.0026, 0.0003, 0.0018, and 0.0016, respectively, on day 4 p.c. In the lungs, P values were 0.0002 and 0.0001 on days 2 and 4, respectively. The dashed horizontal line represents the lower limit of detection.

DISCUSSION

Avian influenza viruses of H5, H6, H7, H9, and H10 subtypes present a potential pandemic threat because they have crossed the species barrier and infected humans (24), though fortunately, these viruses still lack the ability to spread efficiently between humans. Vaccines play an important role in pandemic preparedness, which is an important public health priority. Seasonal live attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIV) have been licensed in the United States since 2003. LAIV are attractive as pandemic vaccine candidates because they stimulate mucosal and systemic humoral and cellular immunity (25, 26) and may provide protection against a broader range of viruses within a subtype.

We have previously generated live attenuated vaccines against H1N1, H2N2, equine H3N8, H5N1, H6N1, H7N3, H7N7, H7N9, and H9N2 animal influenza viruses and found that these candidate vaccines were safe and efficacious in conferring protection against wild-type viruses in mice and ferrets (23, 27–31). Several of these vaccines have also been evaluated in phase 1 clinical trials (32–38).

In this study, we selected the tl/TX/079/07 H3N8 influenza virus for vaccine development based on the replicative capacity and antigenic cross-reactivity of postinfection sera from mice and ferrets infected with avian H3 viruses (14). We evaluated the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of the vaccine candidate against challenge with homologous and heterologous influenza viruses in mice and ferrets. In mice, a single dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine virus induced robust NtAb titers against the homologous and heterologous wt challenge viruses, including the seal/NH/11 virus that emerged in seals off the New England coast during the course of this study. The replication of the homologous and the heterologous challenge viruses was completely cleared by day 4 p.c. in both the upper and lower respiratory tracts. We observed a similar pattern in the ferret model. Neither the wt nor the ca tl/TX/079/07 virus induced significant pneumonitis in ferrets; histopathologic evaluation of ferret lungs showed minimal to mild bronchointerstitial pneumonitis in mock-inoculated animals as well as in animals inoculated with the tl/TX/079/07 wt or ca virus (data not shown).

Since H3N8 influenza viruses have crossed the species barrier and infected horses and dogs, we assessed the ability of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine to elicit cross-reactive antibody against two horse (A/equine/Georgia/1/1981 and A/equine/Newmarket/5/2003) and two canine (A/canine/Colorado/67238/2008 and A/canine/New York/1201262/11) influenza strains. Ferrets vaccinated with one or two doses of the avian virus vaccine did not cross-react with eq/Newm/03 by MN or HAI assays. However, the avian vaccine elicited cross-reactive NtAb titers with GMTs of 151 and 187, respectively, against an older virus, eq/GA/81. Notably, we did not detect an HAI antibody response. The detection of cross-reactive NtAb in the absence of HAI antibodies suggests that the Abs could be directed at the HA stalk. One or two doses of the avian vaccine elicited cross-reactive Ab against A/canine/Colorado/67238/2008 virus with GMTs of 32 and 67 by MN assay and 23 and 20 by HAI assay, respectively. Cross-reactivity was also observed against the A/canine/New York/1201262/11 virus with GMTs of 170 and 160 by MN assay and 106 and 92 by HAI assay, suggesting that the avian vaccine elicited cross-reactive Abs directed at shared epitopes on the HA head. Taken together, these findings suggest that the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine elicits some cross-reactivity against equine and canine influenza viruses.

As we recently reported with an equine H3N8 influenza vaccine candidate (23), there was a direct correlation between serum Ab response and protection against challenge in mice and ferrets that received one dose of the tl/TX/079/07 ca vaccine virus, although we cannot exclude contributions from other arms of the immune system, such as the cellular or mucosal immune response.

In order to determine whether people who have been vaccinated or naturally infected with seasonal H3N2 influenza viruses during the course of their lives would have cross-reactive antibodies against the H3N8 wt virus, we measured the cross-reactivity in sera from 56 subjects in three age groups, who were enrolled in a previous study. Most subjects in each cohort reported receiving the 2009 to 2010 seasonal trivalent influenza vaccine 2 to 4 months before their sera were collected (20). We observed low but detectable levels of reactivity against the tl/TX/079/07 virus in individuals over 60 years of age and speculate that the detectable cross-reactive NtAbs were induced by previously circulating human influenza A H3N2 viruses. In the event of a pandemic caused by a related virus, such as the seal H3N8 virus that recently crossed the species barrier and infected mammals, this segment of the human population may be immunologically primed due to previous exposure to seasonal H3N2 influenza viruses.

To examine this hypothesis, we explored the effect of prior infection of ferrets with seasonal H3N2 influenza viruses of variable antigenic distance that circulated during different decades on the generation of antibodies that cross-reacted with the tl/TX/079/07 virus. The HA amino acid sequence identities between the tl/TX/079/07 virus and the A/HK/68, A/PC/73, A/LA/87, A/WU/95, A/CA/04, and A/TX/12 seasonal H3N2 viruses are 93.9, 92.6, 86.1, 86.1, 85.4, and 83.6%, respectively. The seasonal H3N2 influenza viruses induced high homologous Ab titers measured by MN and HAI assays and ELISAs. However, only ferrets infected with the seasonal A/HK/68 and A/PC/73 H3N2 viruses had detectable cross-reactive antibodies against the H3N8 avian influenza virus. We detected low levels of IgG ELISA antibody titers in ferrets infected with the A/LA/87, A/WU/95, A/CA/04, and A/TX/12 H3N2 influenza viruses. A correlation was observed between the cross-reactivity of antibodies induced by primary infection with A/HK/68 and A/PC/73 viruses and protective efficacy against the tl/TX/079/07 virus; these ferrets were almost completely protected from replication of the challenge virus in the upper and lower respiratory tract. Interestingly, although challenge virus replicated in the NTs on day 2 p.c. of ferrets primed with A/LA/87, A/WU/95, A/CA/04, or A/TX/12 H3N2 influenza virus, the challenge virus was cleared from the upper respiratory tract on day 4 p.c. and was not detected in the lungs. In the absence of a cross-reactive antibody response, we speculate that this protection may be due to cell-mediated immunity, in particular to cross-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes (39–43) that were selectively expanded upon challenge with the tl/TX/079/07 virus in previously primed ferrets. However, we cannot exclude contributions from other arms of the immune system, such as mucosal antibody responses. Taking together the data obtained from the human sera and ferrets primed with seasonal H3N2 influenza viruses and challenged with the tl/TX/079/07 wt virus, we speculate that if an avian H3N8 influenza virus related to the tl/TX/079/07 virus infects humans causing disease, one dose of the avian H3N8 vaccine will be sufficient to boost an Ab response and to confer protection against the new strain in older adults, as was the case when the H1N1 pandemic influenza virus emerged in 2009. During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, a single dose of inactivated H1N1 pandemic vaccine was sufficient in all except children younger than 3 years of age, indicating that most of the population had been primed by prior infection or vaccination with seasonal H1N1 viruses (44). We can also speculate that if a pandemic caused by an H3N8 influenza virus arises, it may resemble the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in being relatively mild.

In conclusion, we generated a candidate LAIV against an avian H3N8 influenza virus and demonstrated that a single dose of the vaccine was highly immunogenic and efficacious in protecting naive mice and ferrets from challenge with the homologous and antigenically distinct heterologous avian H3N8 viruses, including the recently emerged H3N8 influenza virus in seals, which has the ability to transmit by respiratory droplets in ferrets. We found evidence of cross-reactive antibodies in subjects >60 years of age, and although data from persons between 32 and 60 years of age are lacking, it appears that a segment of the human population may be previously primed for a robust response to an avian influenza H3N8 vaccine. We have also shown that even when previous infection with seasonal human H3N2 influenza viruses elicits little or no cross-reactive Ab against an avian H3N8 influenza virus, ferrets are protected from challenge. These promising preclinical data support further evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of the tl/TX/079/07 vaccine candidate in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIAID, NIH, and was performed as part of a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, NIAID, and MedImmune, LLC.

We thank the staff of the Comparative Medicine Branch, NIAID, and the staff at MedImmune's Animal Care Facility for excellent technical support for animal studies. We are grateful to Michael Osterholm, John M. Pearce, Hon Ip, Zhiping Ye, and Brian Murphy for providing the viruses used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palese P. 2004. Influenza: old and new threats. Nat Med 10:S82–S87. doi: 10.1038/nm1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. 2009. Update: novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infections—worldwide. MMWR 58(17):453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fouchier RA, Munster V, Wallensten A, Bestebroer TM, Herfst S, Smith D, Rimmelzwaan GF, Olsen B, Osterhaus AD. 2005. Characterization of a novel influenza A virus hemagglutinin subtype (H16) obtained from black-headed gulls. J Virol 79:2814–2822. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2814-2822.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon SW, Webby RJ, Webster RG. 2014. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 385:359–375. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Y, Wu Y, Tefsen B, Shi Y, Gao GF. 2014. Bat-derived influenza-like viruses H17N10 and H18N11. Trends Microbiol 22:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford PC, Dubovi EJ, Castleman WL, Stephenson I, Gibbs EP, Chen L, Smith C, Hill RC, Ferro P, Pompey J, Bright RA, Medina MJ, Johnson CM, Olsen CW, Cox NJ, Klimov AI, Katz JM, Donis RO. 2005. Transmission of equine influenza virus to dogs. Science 310:482–485. doi: 10.1126/science.1117950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waddell GH, Teigland MB, Sigel MM. 1963. A new influenza virus associated with equine respiratory disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 143:587–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu J, Zhou H, Jiang T, Li C, Zhang A, Guo X, Zou W, Chen H, Jin M. 2009. Isolation and molecular characterization of equine H3N8 influenza viruses from pigs in China. Arch Virol 154:887–890. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qi T, Guo W, Huang W, Dai L, Zhao L, Li H, Li X, Zhang X, Wang Y, Yan Y, He N, Xiang W. 2010. Isolation and genetic characterization of H3N8 equine influenza virus from donkeys in China. Vet Microbiol 144:455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anthony SJ, St Leger JA, Pugliares K, Ip HS, Chan JM, Carpenter ZW, Navarrete-Macias I, Sanchez-Leon M, Saliki JT, Pedersen J, Karesh W, Daszak P, Rabadan R, Rowles T, Lipkin WI. 2012. Emergence of fatal avian influenza in new England harbor seals. mBio 3(4):e00166-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00166-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herfst S, Schrauwen EJ, Linster M, Chutinimitkul S, de Wit E, Munster VJ, Sorrell EM, Bestebroer TM, Burke DF, Smith DJ, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2012. Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets. Science 336:1534–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1213362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai M, Watanabe T, Hatta M, Das SC, Ozawa M, Shinya K, Zhong G, Hanson A, Katsura H, Watanabe S, Li C, Kawakami E, Yamada S, Kiso M, Suzuki Y, Maher EA, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. 2012. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature 486:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nature10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlsson EA, Ip HS, Hall JS, Yoon SW, Johnson J, Beck MA, Webby RJ, Schultz-Cherry S. 2014. Respiratory transmission of an avian H3N8 influenza virus isolated from a harbour seal. Nat Commun 5:4791. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baz M, Paskel M, Matsuoka Y, Zengel J, Cheng X, Jin H, Subbarao K. 2013. Replication and immunogenicity of swine, equine, and avian H3 subtype influenza viruses in mice and ferrets. J Virol 87:6901–6910. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03520-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg (Lond) 27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann E, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, Hobom G, Webster RG. 2000. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6108–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100133697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen GL, Lamirande EW, Yang CF, Jin H, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2010. Evaluation of replication and cross-reactive antibody responses of H2 subtype influenza viruses in mice and ferrets. J Virol 84:7695–7702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00511-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph T, McAuliffe J, Lu B, Jin H, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2007. Evaluation of replication and pathogenicity of avian influenza a H7 subtype viruses in a mouse model. J Virol 81:10558–10566. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00970-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. 2002. WHO manual on animal influenza diagnosis and surveillance. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/influenza/WHO_manual_on_animal-diagnosis_and_surveillance_2002_5.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sangster MY, Baer J, Santiago FW, Fitzgerald T, Ilyushina NA, Sundararajan A, Henn AD, Krammer F, Yang H, Luke CJ, Zand MS, Wright PF, Treanor JJ, Topham DJ, Subbarao K. 2013. B cell response and hemagglutinin stalk-reactive antibody production in different age cohorts following 2009 H1N1 influenza virus vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20:867–876. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00735-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallagher M, Bucher DJ, Dourmashkin R, Davis JF, Rosenn G, Kilbourne ED. 1984. Isolation of immunogenic neuraminidases of human influenza viruses by a combination of genetic and biochemical procedures. J Clin Microbiol 20:89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Donnell CD, Wright A, Vogel LN, Wei CJ, Nabel GJ, Subbarao K. 2012. Effect of priming with H1N1 influenza viruses of variable antigenic distances on challenge with 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus. J Virol 86:8625–8633. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00147-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baz M, Paskel M, Matsuoka Y, Zengel J, Cheng X, Treanor JJ, Jin H, Subbarao K. 2014. A live attenuated equine H3N8 influenza vaccine is highly immunogenic and efficacious in mice and ferrets. J Virol 89:1652–1659. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02449-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richard M, de Graaf M, Herfst S. 2014. Avian influenza A viruses: from zoonosis to pandemic. Future Virol 9:513–524. doi: 10.2217/fvl.14.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clements ML, Murphy BR. 1986. Development and persistence of local and systemic antibody responses in adults given live attenuated or inactivated influenza A virus vaccine. J Clin Microbiol 23:66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorse GJ, Campbell MJ, Otto EE, Powers DC, Chambers GW, Newman FK. 1995. Increased anti-influenza A virus cytotoxic T cell activity following vaccination of the chronically ill elderly with live attenuated or inactivated influenza virus vaccine. J Infect Dis 172:1–10. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen GL, Lamirande EW, Cheng X, Torres-Velez F, Orandle M, Jin H, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2014. Evaluation of three live attenuated H2 pandemic influenza vaccine candidates in mice and ferrets. J Virol 88:2867–2876. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01829-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Z, Santos C, Aspelund A, Gillim-Ross L, Jin H, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2009. Evaluation of live attenuated influenza a virus H6 vaccines in mice and ferrets. J Virol 83:65–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01775-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Min JY, Vogel L, Matsuoka Y, Lu B, Swayne D, Jin H, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2010. A live attenuated H7N7 candidate vaccine virus induces neutralizing antibody that confers protection from challenge in mice, ferrets, and monkeys. J Virol 84:11950–11960. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01305-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suguitan AL Jr, McAuliffe J, Mills KL, Jin H, Duke G, Lu B, Luke CJ, Murphy B, Swayne DE, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2006. Live, attenuated influenza A H5N1 candidate vaccines provide broad cross-protection in mice and ferrets. PLoS Med 3:e360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H, Subbarao K, Swayne D, Chen Q, Lu X, Katz J, Cox N, Matsuoka Y. 2003. Generation and evaluation of a high-growth reassortant H9N2 influenza A virus as a pandemic vaccine candidate. Vaccine 21:1974–1979. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00809-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karron RA, Callahan K, Luke C, Thumar B, McAuliffe J, Schappell E, Joseph T, Coelingh K, Jin H, Kemble G, Murphy BR, Subbarao K. 2009. A live attenuated H9N2 influenza vaccine is well tolerated and immunogenic in healthy adults. J Infect Dis 199:711–716. doi: 10.1086/596558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karron RA, Talaat K, Luke C, Callahan K, Thumar B, Dilorenzo S, McAuliffe J, Schappell E, Suguitan A, Mills K, Chen G, Lamirande E, Coelingh K, Jin H, Murphy BR, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2009. Evaluation of two live attenuated cold-adapted H5N1 influenza virus vaccines in healthy adults. Vaccine 27:4953–4960. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talaat KR, Karron RA, Callahan KA, Luke CJ, DiLorenzo SC, Chen GL, Lamirande EW, Jin H, Coelingh KL, Murphy BR, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2009. A live attenuated H7N3 influenza virus vaccine is well tolerated and immunogenic in a phase I trial in healthy adults. Vaccine 27:3744–3753. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talaat KR, Karron RA, Liang PH, McMahon BA, Luke CJ, Thumar B, Chen GL, Min JY, Lamirande EW, Jin H, Coelingh KL, Kemble GW, Subbarao K. 2013. An open-label phase I trial of a live attenuated H2N2 influenza virus vaccine in healthy adults. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 7:66–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talaat KR, Karron RA, Luke CJ, Thumar B, McMahon BA, Chen GL, Lamirande EW, Jin H, Coelingh KL, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2011. An open label phase I trial of a live attenuated H6N1 influenza virus vaccine in healthy adults. Vaccine 29:3144–3148. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babu TM, Levine M, Fitzgerald T, Luke C, Sangster MY, Jin H, Topham D, Katz J, Treanor J, Subbarao K. 2014. Live attenuated H7N7 influenza vaccine primes for a vigorous antibody response to inactivated H7N7 influenza vaccine. Vaccine 32:6798–6804. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talaat KR, Luke CJ, Khurana S, Manischewitz J, King LR, McMahon BA, Karron RA, Lewis KD, Qin J, Follmann DA, Golding H, Neuzil KM, Subbarao K. 2014. A live attenuated influenza A(H5N1) vaccine induces long-term immunity in the absence of a primary antibody response. J Infect Dis 209:1860–1869. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yewdell JW, Bennink JR, Smith GL, Moss B. 1985. Influenza A virus nucleoprotein is a major target antigen for cross-reactive anti-influenza A virus cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82:1785–1789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doherty PC, Kelso A. 2008. Toward a broadly protective influenza vaccine. J Clin Invest 118:3273–3275. doi: 10.1172/JCI37232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kreijtz JH, Bodewes R, van Amerongen G, Kuiken T, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF. 2007. Primary influenza A virus infection induces cross-protective immunity against a lethal infection with a heterosubtypic virus strain in mice. Vaccine 25:612–620. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epstein SL, Lo CY, Misplon JA, Bennink JR. 1998. Mechanism of protective immunity against influenza virus infection in mice without antibodies. J Immunol 160:322–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng X, Zengel JR, Suguitan AL Jr, Xu Q, Wang W, Lin J, Jin H. 2013. Evaluation of the humoral and cellular immune responses elicited by the live attenuated and inactivated influenza vaccines and their roles in heterologous protection in ferrets. J Infect Dis 208:594–602. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plennevaux E, Sheldon E, Blatter M, Reeves-Hoche MK, Denis M. 2010. Immune response after a single vaccination against 2009 influenza A H1N1 in USA: a preliminary report of two randomised controlled phase 2 trials. Lancet 375:41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]