ABSTRACT

The elongation factor Tu GTP binding domain-containing protein 2 (EFTUD2) was identified as an anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) host factor in our recent genome-wide small interfering RNA (siRNA) screen. In this study, we sought to further determine EFTUD2's role in HCV infection and investigate the interaction between EFTUD2 and other regulators involved in HCV innate immune (RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3) and JAK-STAT1 pathways. We found that HCV infection decreased the expression of EFTUD2 and the viral RNA sensors RIG-I and MDA5 in HCV-infected Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells and in liver tissue from in HCV-infected patients, suggesting that HCV infection downregulated EFTUD2 expression to circumvent the innate immune response. EFTUD2 inhibited HCV infection by inducing expression of the interferon (IFN)-stimulated genes (ISGs) in Huh7 cells. However, its impact on HCV infection was absent in both RIG-I knockdown Huh7 cells and RIG-I-defective Huh7.5.1 cells, indicating that the antiviral effect of EFTUD2 is dependent on RIG-I. Furthermore, EFTUD2 upregulated the expression of the RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) RIG-I and MDA5 to enhance the innate immune response by gene splicing. Functional experiments revealed that EFTUD2-induced expression of ISGs was mediated through interaction of the EFTUD2 downstream regulators RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3. Interestingly, the EFTUD2-induced antiviral effect was independent of the classical IFN-induced JAK-STAT pathway. Our data demonstrate that EFTUD2 restricts HCV infection mainly through an RIG-I/MDA5-mediated, JAK-STAT-independent pathway, thereby revealing the participation of EFTUD2 as a novel innate immune regulator and suggesting a potentially targetable antiviral pathway.

IMPORTANCE Innate immunity is the first line defense against HCV and determines the outcome of HCV infection. Based on a recent high-throughput whole-genome siRNA library screen revealing a network of host factors mediating antiviral effects against HCV, we identified EFTUD2 as a novel innate immune regulator against HCV in the infectious HCV cell culture model and confirmed that its expression in HCV-infected liver tissue is inversely related to HCV infection. Furthermore, we determined that EFTUD2 exerts its antiviral activity mainly through governing its downstream regulators RIG-I and MDA5 by gene splicing to activate IRF3 and induce classical ISG expression independent of the JAT-STAT signaling pathway. This study broadens our understanding of the HCV innate immune response and provides a possible new antiviral strategy targeting this novel regulator of the innate response.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) poses a threat to public health by infecting approximately 170 million people worldwide and causing chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (1, 2). Fifty to ninety percent of acute infections become chronic due to failure to mount a productive immune response to clear the virus. The innate immune system is the first line of defense responsible for recognizing viral pathogens and is therefore one of the crucial elements in determining the outcome of HCV infection.

It is known that HCV RNA is recognized by the combined actions of protein kinase R (PKR), retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 (RIG-I), and Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) after viral entry into host cells (3–5). Pathogen recognition triggers downstream signaling to activate transcription factors, such as interferon (IFN) regulatory factors (IRFs), to induce type I interferon secretion and stimulation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, leading to the expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), which presumptively mediate control of viral replication (6). Our previous studies have demonstrated that signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) is the critical signaling component in innate antiviral immunity to HCV and that HCV core protein and nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) are associated with decreased STAT1 levels (7–9). However, the precise mechanisms for HCV persistence are still incompletely understood. Moreover, full restriction of HCV may be mediated by additional actions of innate immune signaling amplifiers, IRFs, and other virus response pathways (10). Melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) is an RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) that senses cytoplasmic viral RNA (11). Although some studies suggest that MDA5 does not bind to the secondary structure of HCV RNA, its role in HCV sensing remains unknown (12). HCV has evolved multiple means to counter the innate immune response, such as using NS3/4A protease to cleave the mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) protein and ablate RIG-I-mediated innate immune signaling and using NS4B to block the interaction of the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) and TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), resulting in the persistence of infection (13, 14).

A recent high-throughput whole-genome small interfering RNA (siRNA) library screen in our laboratory identified 22 genes forming a novel regulatory network of host factors mediating antiviral effects against HCV (15). A key regulator in the network, elongation factor Tu GTP binding domain-containing protein 2 (EFTUD2), was discovered to restrict HCV infection through IFN-independent stimulation of the innate immune response. EFTUD2 is a spliceosomal GTPase with a regulatory function in catalytic splicing and post-splicing complex disassembly (16).

However, EFTUD2's role in HCV infection remains unknown. To better understand how EFTUD2 participates in the antiviral response against HCV, we studied the interaction of EFTUD2 and other immune regulators related to HCV sensing and the IFN-induced JAK-STAT signaling pathway using liver samples from HCV-infected patients and state-of-the-art HCV cell culture models (17).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines, inhibitors, and liver specimens.

Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (0.1 mg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin). Polyethylene glycol (PEG)–IFN-α was obtained from Schering Corporation (Kenilworth, NJ). The RLR signaling inhibitor BX795 was purchased (InvivoGen) and dissolved in 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells stably expressing EFTUD2 and short hairpin RNA targeting EFTUD2 (shEFTUD2) were generated via lentiviral gene transfer using a transfer plasmid containing EFTUD2/shEFTUD2 and green fluorescent protein (GFP), a packaging plasmid, and an envelope plasmid, as described previously (18), followed by selection in medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml G418.

Human liver specimens (eight with chronic HCV infection and eight healthy liver tissues from non-HCV-infected control individuals) were collected from Anhui Provincial Hospital and stored in RNAlater solution (Ambion). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Anhui Provincial Hospital.

HCVpp and HCV cell culture.

HCV pseudoparticle (HCVpp) production has been described previously (19). Huh7 or Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with HIV-based HCVpp bearing envelope glycoproteins of JFH1. Establishment of HCV cell culture has been described previously (20, 21). Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with infectious HCV JFH1 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.2 or with HCV Jc1/Gluc (22) bearing a secreted Gaussia luciferase reporter at an MOI of 1. Viral infection was assessed by quantitative PCR or luciferase activity as described previously (22–24).

siRNA transfection.

siRNAs were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen). Dharmacon On-Target Plus Smart Pool human siRNAs (Fisher Scientific Life Science Research) were used for gene knockdown for EFTUD2 (siEFTUD2), RIG-I (siRIG-I), MDA5 (siMDA5), TBK1 (siTBK1), IRF3 (siIRF3), and a nontargeting negative control (siNeg). Protein levels for each gene knockdown were confirmed by Western blotting.

Plasmid transfection.

Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were seeded on plates for 24 h and transfected with the selected plasmids using FuGene HD transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocol. pEFTUD2 and empty vectors were purchased from OriGene Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD). pRIG-I, pΔRIG-I, and pMDA5 vectors were obtained from Michaela Gack (Harvard Medical School).

qPCR.

Total cellular RNA isolation, reverse transcription to cDNA, and quantitative PCR (qPCR) were performed according to a previously published protocol (25). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a control for basal RNA levels. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

| Gene target | Forward primer (5′–3′)a | Reverse primer (5′–3′)b |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | ACAGTCCATGCCATCACTGCC | GCCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTG |

| JFH1 | CTGTCTTCACGCAGAAAGCG | TCGCAACCCAACGCTACTCG |

| EFTUD2 | CAATATCATGGACACTCCAGGAC | CGGTCAATCTTGTTGATGCACA |

| Mx1 | CCCTTCCCAGAGGCAGCGGG | CTGATTGCCCACAGCCACTC |

| OAS1 | GGTGGTAAAGGGTGGCTCCTC | TCTGCAGGTAGGTGCACTCC |

| PKR | CCAGTGATGATTCTCTTGAGAGC | CCCCAAAGCGTAGAGGTCCA |

| JAK1 | ACCTCTTTGCCCTGTATGACGA | CCCAGTCACCATCACTTCGTAGTAG |

| STAT1 | GAGAGCTGTCTAGGTTAACGTTCGC | AGTCAAGCTGCTGAAGTTCGTACC |

| INFR1 | AACAGGAGCGATGAGTCTGTC | TGCGAAATGGTGTAAATGAGTCA |

| IRF9 | GGAGCTCTTCAGAACCGCCTA | CCTTACAGATGAAAGAGGGCGTATATC |

| RIG-I | CCTACCTACATCCTGAGCTACAT | TCTAGGGCATCCAAAAAGCCA |

| MDA5 | TCGAATGGGTATTCCACAGACG | GTGGCGACTGTCCTCTGAA |

| RIG-I (pre-mRNA) | GGAGGGAAACGAAACTAGCC (F1) | GGCTGTGCCTCACTAGCTTT (R1) |

| RIG-I (mature mRNA) | CCCTGGTTTAGGGAGGAAGA (F2) | TGGTCTAGGGCATCCAAAAA (R2) |

| MDA5 (pre-mRNA) | AACCTCCTTCAGCCCACTCT (F1) | CCCAAAGAGGTCAAGCACAT (R1) |

| MDA5 (mature mRNA) | CGCTACATGAACCCTGAGC (F2) | CAATCCGGTTTCTGTCTTC (R2) |

Primers F1 and F2 are forward primers designed to target pre-mRNA and mature mRNA, respectively.

Primers R1 and R2 are reverse primers designed to target pre-mRNA and mature mRNA, respectively.

Western blotting.

Proteins were obtained, separated, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as reported previously (26, 27). The target proteins were detected with the following specific primary antibodies: mouse anti-HCV core protein (C7-50; Fisher Scientific); mouse anti-actin, rabbit anti-EFTUD2, rabbit anti-RIG-I, rabbit anti-MDA5, rabbit anti-TBK1, rabbit anti-MxA1, and rabbit anti-OAS1 (Sigma Life Science and Biochemicals); and rabbit anti-IRF3 and anti-phospho-IRF-3 (Ser396) (Cell Signaling Technology). The secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) donkey anti-rabbit IgG and HRP-conjugated ECL sheep anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare Biosciences). The blots were detected by chemiluminescence using an Amersham ECL Western blot detection kit (GE Healthcare Biosciences).

Immunofluorescence analysis.

Immunofluorescence was performed as previously reported (28). Huh7.5.1 or Huh7 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin in PBS. A 1:100 dilution of rabbit anti-EFTUD2 (Sigma Life Science and Biochemicals) and of goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) was used to detect EFTUD2 expression. 4′,6′-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen) was added to stain nuclear structures. Cells were imaged with an EVOS FL Cell Imaging System (Life Technologies).

Cell cycle analysis.

Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were harvested, fixed, and stained with a cycle analysis kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's protocol 2 days after transfection with empty plasmid (pEmpty) or EFTUD2 (pEFTUD2). Cell cycle distribution was analyzed by a FACScan instrument (BD Biosciences) and CellFIT software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student's t test. Unless otherwise stated, data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD) of at least three sample replicates.

RESULTS

EFTUD2 restricts HCV infection in HCV cell culture models.

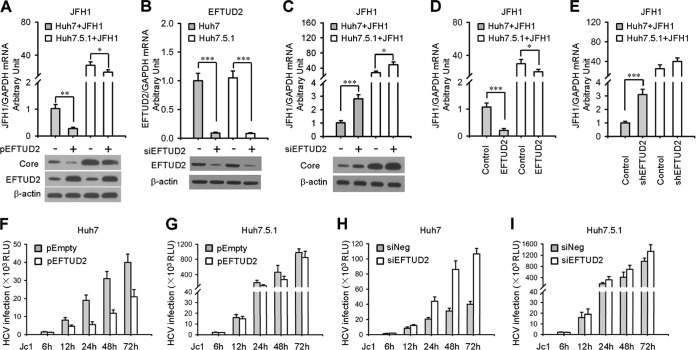

We first overexpressed or silenced EFTUD2 in Huh7 cells to test EFTUD2's role in HCV replication in the JFH1 infection model. We found that EFTUD2 overexpression resulted in a 72.4% ± 4.9% (P < 0.01) decrease in HCV RNA replication, while silencing EFTUD2 with a specific siRNA significantly enhanced HCV replication by 2.8- ± 0.4-fold (P < 0.001) at 24 h postinfection in Huh7 cells (Fig. 1A to C). Western blotting confirmed HCV core and EFTUD2 protein expression (Fig. 1A to C). These results were further confirmed using an Huh7 cell line stably expressing EFTUD2 or shEFTUD2 (Fig. 1D and E). Time course infection of HCV Jc1/Gluc upon overexpression or silencing of EFTUD2 in Huh7 cells showed that EFTUD2 inhibited HCV infection at 12 h postinfection and that the effect reached a plateau at 24 h postinfection (Fig. 1F to I), indicating its role in restricting HCV infection at the viral postentry stage.

FIG 1.

EFTUD2 restricts HCV infection in Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells. (A) Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with pEFTUD2 or empty vector for 48 h before infection with HCV JFH1(MOI of 0.2) for another 24 h. HCV infection was determined by qPCR and Western blotting of HCV core protein. EFTUD2 expression was assessed by Western blotting. (B) Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with siRNA specifically targeting EFTUD2 (siEFTUD2) or a negative-control siRNA (siNeg) for 48 h. EFTUD2 expression was assessed by qPCR and Western blotting. (C) Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with siEFTUD2 or siNeg for 48 h before infection with HCV JFH1 (MOI of 0.2) for another 24 h. HCV infection was determined by qPCR and Western blotting of HCV core protein. (D and E) Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cell lines stably expressing EFTUD2 (D) or shEFTUD2 (E) were generated as described in Materials and Methods and infected with HCV JFH1. HCV infection was assessed by qPCR at 24 h postinfection. (F to H) Huh7 or Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with HCV Jc1/Gluc (MOI of 1) 2 days after transfection with empty plasmid (pEmpty)/EFTUD2 (pEFTUD2) or with a negative-control siRNA (siNeg)/siRNA targeting EFTUD2 (siEFTUD2). HCV infection was assessed by luciferase activity at 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection.*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. RLU, relative light units.

In contrast to EFTUD2's significant inhibitory effect against HCV infection in Huh7 cells, overexpression or silencing of EFTUD2 resulted in negligible changes in HCV infection levels in RIG-I-defective Huh7.5.1 cells (Fig. 1), suggesting that RIG-I participates in the EFTUD2-induced anti-HCV effect. In addition, we found that EFTUD2 has no effect on the expression of HCV entry factors (data not shown) and HCV cell proliferation (data not shown), indicating that it functions at a postentry stage.

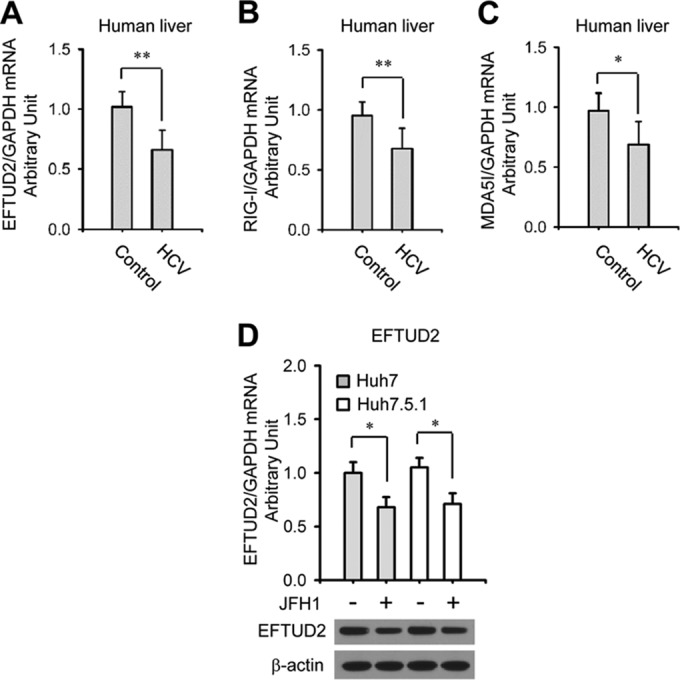

Decreased expression of EFTUD2 and viral RNA sensors RIG-I and MDA5 in the liver of patients with chronic HCV infection.

To assess the clinical relevance of EFTUD2, eight liver biopsy specimens of patients with chronic HCV infection and eight healthy liver specimens from patients without HCV infection (Table 2) were collected to measure the expression of EFTUD2 in liver by qPCR. As shown in Fig. 2A, EFTUD2 expression in liver was significantly lower in patients with chronic hepatitis C than in tissues of uninfected control individuals. Since recent studies have reported EFTUD2's role in regulating the innate immune response (29), we tested the expression of viral RNA sensors RIG-I and MDA5 in parallel and observed decreased expression of RIG-I and MDA in the liver of patients with chronic hepatitis C. These results strongly suggest a role for EFTUD2 in chronic hepatitis C and suggest its potential mechanistic linkage with the immune regulators RIG-I and MDA5.

TABLE 2.

| Patient no. | HCV infection status | Characteristic(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Negative | Liver steatosis |

| 2 | Negative | Liver steatosis |

| 3 | Negative | Liver steatosis |

| 4 | Negative | Brain death |

| 5 | Negative | Brain death |

| 6 | Negative | With hepatic hemangioma |

| 7 | Negative | With hepatic hemangioma |

| 8 | Negative | With hepatic hemangioma |

| 9 | Positive | HCV genotype 1b, no fibrosis |

| 10 | Positive | HCV genotype 1b, no fibrosis |

| 11 | Positive | HCV genotype 1b, Ishak fibrosis score 1/6 |

| 12 | Positive | HCV genotype 1b, Ishak fibrosis score 2/6 |

| 13 | Positive | HCV genotype 1b, Ishak fibrosis score 2/6 |

| 14 | Positive | HCV genotype 2a, no fibrosis |

| 15 | Positive | HCV genotype 2a, Ishak fibrosis score 1/6 |

| 16 | Positive | HCV genotype 2a, Ishak fibrosis score 2/6 |

FIG 2.

Decreased expression of EFTUD2 in liver specimens from patients with chronic HCV infection and in hepatic cells from an HCV cell culture model. The expression of EFTUD2 (A), RIG-I (B), and MDA5 (C) was assessed by qPCR and normalized to the level of the endogenous control (GAPDH) using liver biopsy specimens from eight chronically HCV-infected patients (HCV) and eight HCV-uninfected controls. Details of patient characteristics are described in Table 2. (D) The expression of EFTUD2 in Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells with or without HCV JFH1 infection was assessed by qPCR. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

In line with the decreased EFTUD2 expression in liver from patients with chronic hepatitis C, EFTUD2 expression was downregulated in both Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells at 48 h after JFH1 infection (Fig. 2D) (P < 0.05), indicating that HCV may circumvent EFTUD2's restrictive effects by reducing its expression level.

Immunofluorescence staining showed that EFUTD2 was mainly localized in the nuclei of hepatic cells (data not shown), and its distribution was not changed upon HCV infection (data not shown), suggesting that it regulates pre-mRNA processing.

EFTUD2 upregulates RIG-I and MDA5 expression by pre-mRNA splicing.

We next studied the role of RIG-I and MDA5 in the EFTUD-induced antiviral effect. In line with previous reports (30), we found that HCV RNA levels in RIG-I-defective Huh7.5.1 cells were 27.7- ± 4.4-fold higher than in Huh7 cells (P < 0.001) in JFH1 HCV infection (Fig. 1A and C), corroborating the role of the RIG-I innate immune sensor in controlling viral infection.

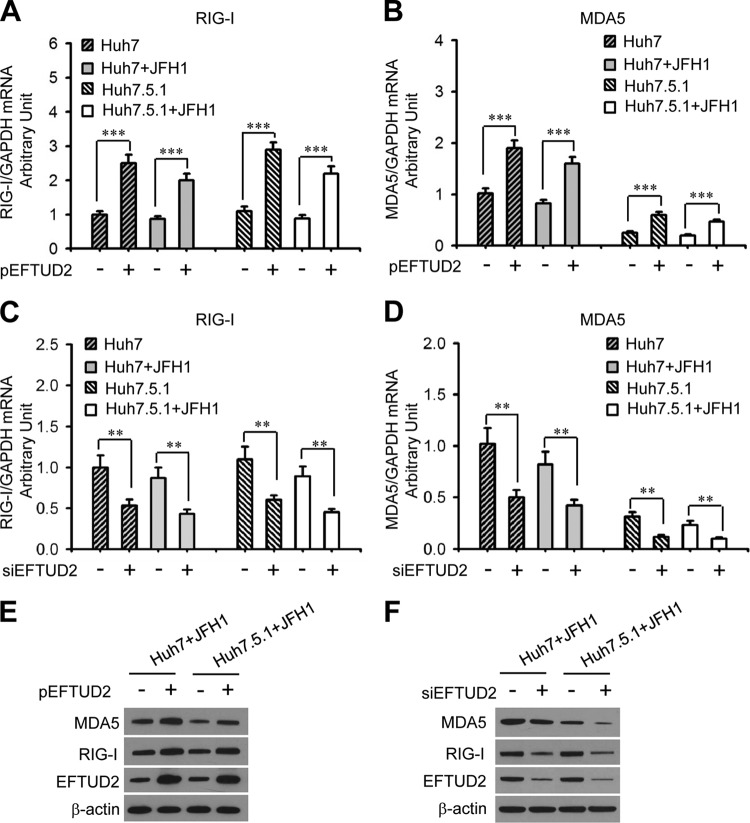

As shown in Fig. 3A and B, EFTUD2 overexpression significantly increased RIG-I and MDA5 mRNA expression levels in Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells with or without HCV infection by around 2-fold (P < 0.01). Similarly, knockdown of EFTUD2 significantly decreased RIG-I and MDA5 mRNA levels in Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells by around 50% independently of HCV infection (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3C and D). Western blotting confirmed EFTUD2 regulation of RIG-I and MDA5 protein expression (Fig. 3E and F).

FIG 3.

EFTUD2 upregulates expression of RIG-I and MDA5 with or without HCV JFH1 infection. Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with pEFTUD2 or empty vector for 48 h (A, B, and E) or with an siRNA specifically targeting EFTUD2 (siEFTUD2) or siNeg for 48 h (C, D, and F) before infection with HCV JFH1 (MOI of 0.2) or a mock control for another 24 h. (A to D) mRNA expression of RIG-I and MDA5 was measured by qPCR. (E and F) Protein expression of RIG-I, MDA5, and EFTUD2 was assessed by Western blotting with β-actin as a loading control. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

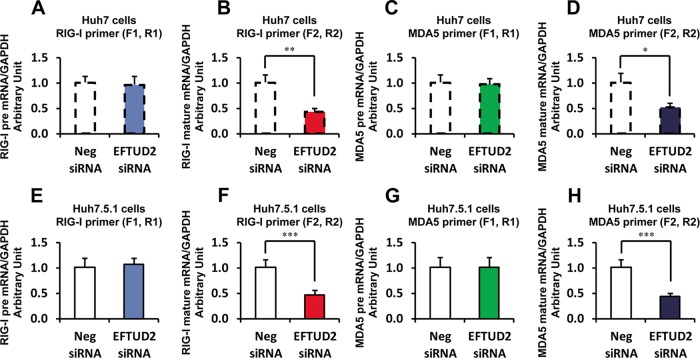

We then explored the interaction of EFTUD2 and RIG-I using a specific siRNA targeting EFTUD2. We designed the specific primers (Table 1) to assess RIG-I and MDA5 pre-mRNA and mature mRNA in Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells. We found that EFTUD2 siRNA significantly reduced RIG-I and MDA5 mature mRNA levels but not pre-mRNA levels in both Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells (Fig. 4), confirming EFTUD2's efficient splicing of the pre-mRNAs of RIG-I and MDA5.

FIG 4.

EFTUD2 siRNA significantly reduces RIG-I and MDA5 mature mRNA levels in Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells. To assess RIG-I or MDA5 pre-mRNAs, we designed primer F1 or R1 (Table 1), which located within intron 1. To monitor RIG-I or MDA5 mature mRNA, we designed primer F2 or R2 (Table 1) that located across exons 1 and 2. We found that EFTUD2 siRNA significantly reduced RIG-I and MDA5 mature mRNAs, but not pre-mRNAs, in both Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells.

Taken together, these data indicate that EFTUD2 regulates RIG-I and MDA5 expression by pre-mRNA splicing.

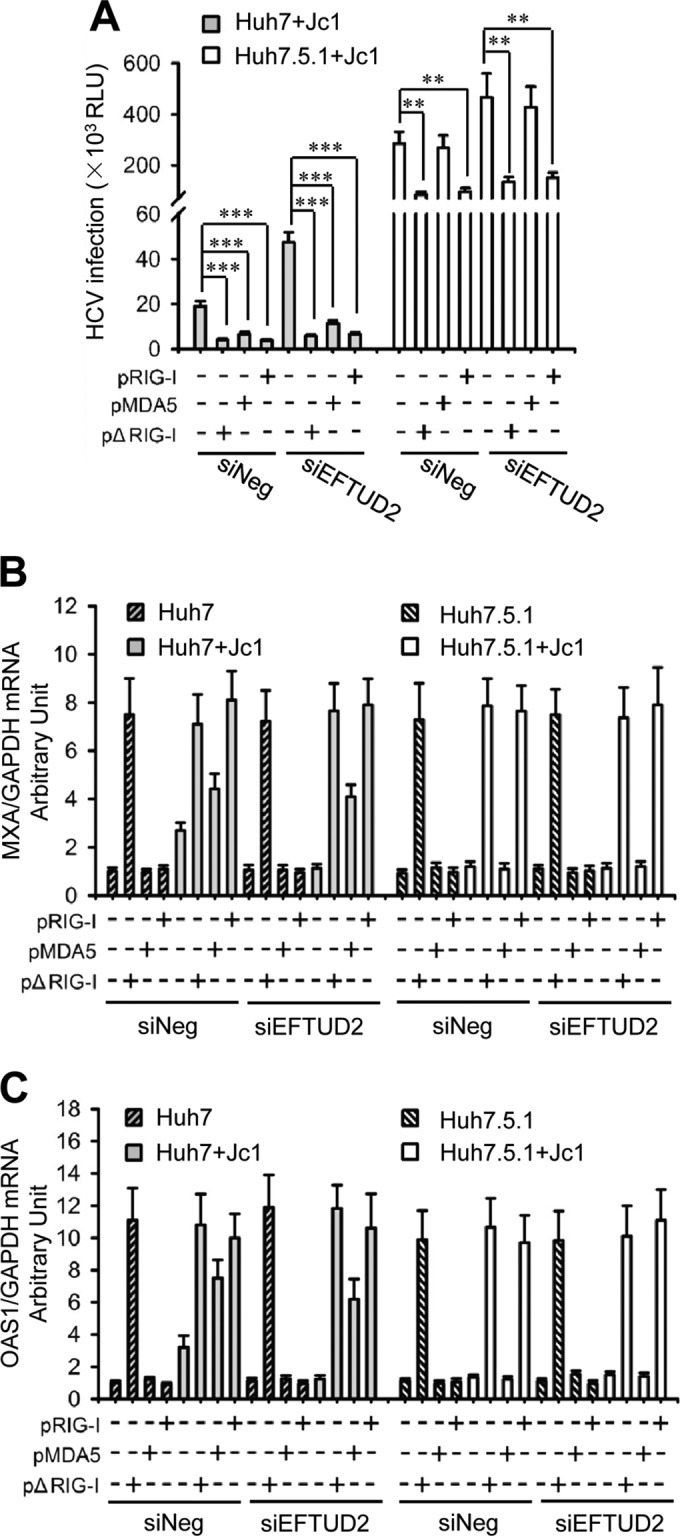

EFTUD2 induced ISG expression through RIG-I/MDA5.

To investigate the role of RIG-I and MDA5 in the EFTUD2-induced antiviral effect, we overexpressed wild-type RIG-I (pRIG-I), constitutively active RIG-I (pΔRIG), or wild-type MDA5 (pMDA5) in EFTUD2 knockdown Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells. Overexpression of pRIG-I, pΔRIG-I, or pMDA5 significantly inhibited the infection of highly infectious HCV Jc1/Gluc in Huh7 cells independent of the EFTUD2 expression level (Fig. 5A), indicating that RIG-I and MDA5 are downstream of EFTUD2. Silencing EFTUD2 resulted in increased HCV infection, which could be reversed by transfection of RIG-I or MDA5 into Huh7 cells (Fig. 5A), confirming that EFTUD2's anti-HCV effect is RIG-I and MDA5 dependent. MDA5 overexpression did not have an impact on HCV infection in RIG-I-defective Huh7.5.1 cells (Fig. 5A), indicating that the inhibitory effect of MDA5 on HCV infection is dependent on RIG-I. Furthermore, pRIG-I, pΔRIG-I, or pMDA5 overexpression promoted the expression of ISGs 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1) and MxA significantly upon HCV infection (Fig. 5B and C), demonstrating that EFTUD2 induces ISG expression through RIG-I and MDA5 to inhibit HCV infection. Overexpression of MDA5 failed to induce ISG expression in RIG-I-defective Huh7.5.1 cells (Fig. 5B and C), indicating that MDA5-induced ISG expression is dependent on RIG-I. RIG-I and MDA5 were able to induce ISG expression independently of EFTUD2 expression (Fig. 5B and C), confirming that RIG-I and MDA5 are downstream of EFTUD2. Notably, overexpression of pRIG-I and pMDA5 induced ISG expression only in the presence of HCV (Fig. 5B and C), confirming the role of RIG-I and MDA5 in viral sensing. Taken together, these results demonstrate that EFTUD2 induces ISG expression through its downstream effectors RIG-I/MDA5.

FIG 5.

EFTUD2 induces ISG expression through RIG-I/MDA5. Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were cotransfected with EFTUD2 siRNA (siEFTUD2) or a negative siRNA (siNeg) and pΔRIG-I, pMDA5, pRIG-I, or empty vector for 48 h before infection with HCV Jc1/Gluc at an MOI of 1 for 24 h. (A) HCV infection was assessed by luciferase activity. Results are expressed in relative light units (RLU). (B and C) mRNA expression of MxA and OAS1 was measured by qPCR. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

EFTUD2 activates IRF3 to induce ISG expression through RLR signaling.

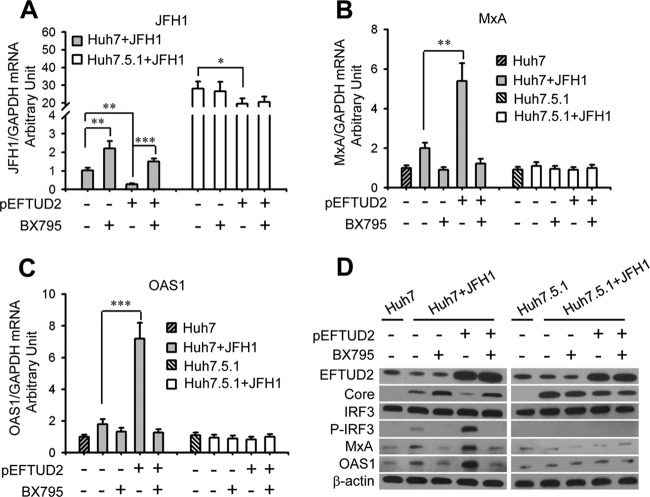

To evaluate the role of RIG-I/MDA5 signaling in EFTUD2's antiviral effect, an RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) signaling inhibitor specifically targeting TBK1, BX795, was used to block RLR signaling in HCV-infected EFTUD2-overexpressing Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells (31). Compared with mock treatment, BX795 significantly increased HCV infection in JFH1-infected Huh7 cells with or without EFTUD2 overexpression (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6A), while this effect was not observed in RIG-I-defective Huh7.5.1 cells infected with JFH1, indicating that EFTUD2 restricts HCV infection through RIG-I-dependent RLR signaling. IRF3 is a key transcriptional factor that induces IFN synthesis and ultimately production of ISGs (32). The increased expression of ISGs (MxA and OAS1) and phosphorylation of IRF3 induced by EFTUD2 overexpression were completely reversed by BX795 in HCV-infected Huh7 cells (Fig. 5B to D), demonstrating that EFTUD2 activates IRF3 phosphorylation and ISG expression through RLR signaling.

FIG 6.

The RLR inhibitor BX795 abrogates ISG production and reverses EFTUD2-mediated inhibition of HCV in an RIG-I dependent manner. Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with pEFTUD2 vector and treated with the RLR signaling inhibitor BX795 or a mock control for 48 h and then infected with JFH1 (MOI of 0.2) for 24 h. HCV infection (A) and mRNA expression of MxA (B) and OAS1 (C) were determined by qPCR. (D) Protein expression of EFTUD2, MxA, OAS1, IRF3, phosphorylated-IRF3 (P-IRF3), and HCV core protein was assessed by Western blotting. *, P < 0.05;**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

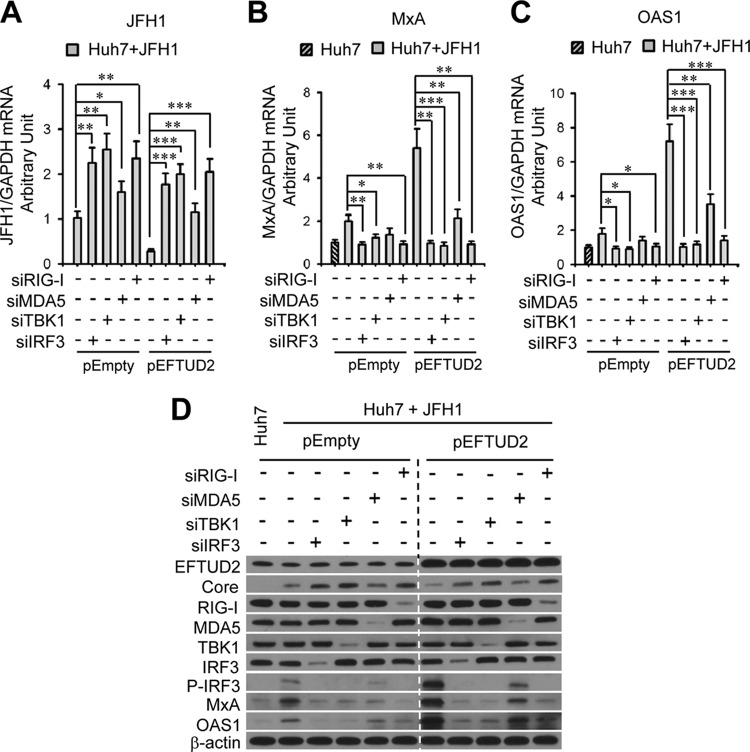

EFTUD2 governs its downstream regulators RIG-I, MDA5, IRF3, and TBK1 to induce ISG expression.

To determine the relationship between EFTUD2 and the main regulators involved in the RIG-I/MDA5 pathways, including RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3, we silenced RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3 in EFTUD2-overexpressing Huh7 cells, followed by HCV JFH1 infection. As shown in Fig. 6A, silencing RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3 significantly increased HCV infection in JFH1-infected Huh7 cells independent of EFTUD2 overexpression (P < 0.05), confirming that EFTUD2 lies upstream of RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3.

To assess whether EFTUD2 downstream regulators RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3 are required for EFTUD-mediated ISG expression, ISG (MxA and OAS1) mRNA and protein expression levels were measured after knockdown of RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3 in JFH1-infected Huh7 cells with or without EFTUD2 overexpression. As shown in Fig. 7B and C, MxA and OAS1 mRNA levels in these cells were markedly reduced by knockdown of RIG-I, IRF3, or TBK1 in JFH1-infected Huh7 cells with or without EFTUD2 overexpression (P < 0.05). In contrast, MDA5 siRNA moderately, but significantly, inhibited MxA and OAS1 mRNA expression compared to expression with negative siRNAs in JFH1-infected Huh7 cells with EFTUD2 overexpression (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7B and C). Western blot analysis confirmed these results (Fig. 7D). Similarly, silencing of RIG-I, IRF3, or TBK1 completely abolished IRF3 phosphorylation, in contrast to results with negative siRNA treatment in JFH1-infected Huh7 cells with or without EFTUD2 overexpression (Fig. 6D).

FIG 7.

EFTUD2 activates TBK1 and IRF3 through RIG-I/MDA5 to promote ISG production and inhibit HCV infection. Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were cotransfected with pEFTUD2 or empty vector together with one of the following siRNAs: IRF3 (siIRF3), TBK1 (siTBK1), MDA5 (siMDA5), or RIG-I (siRIG-I) siRNA or with a negative siRNA (siNeg) for 48 h before infection with HCV JFH1 (MOI of 0.2) for 24 h. HCV infection (A) and mRNA expression of MxA (B) and OAS1 (C) were determined by qPCR. (D) Protein expression of RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, IRF3, P-IRF3, MxA, OAS1, and HCV core protein was analyzed by Western blotting. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Taken together, these results demonstrated that EFTUD2 governs its downstream effectors RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3 to induce ISG expression, which has been reported to confer anti-HCV activity (33).

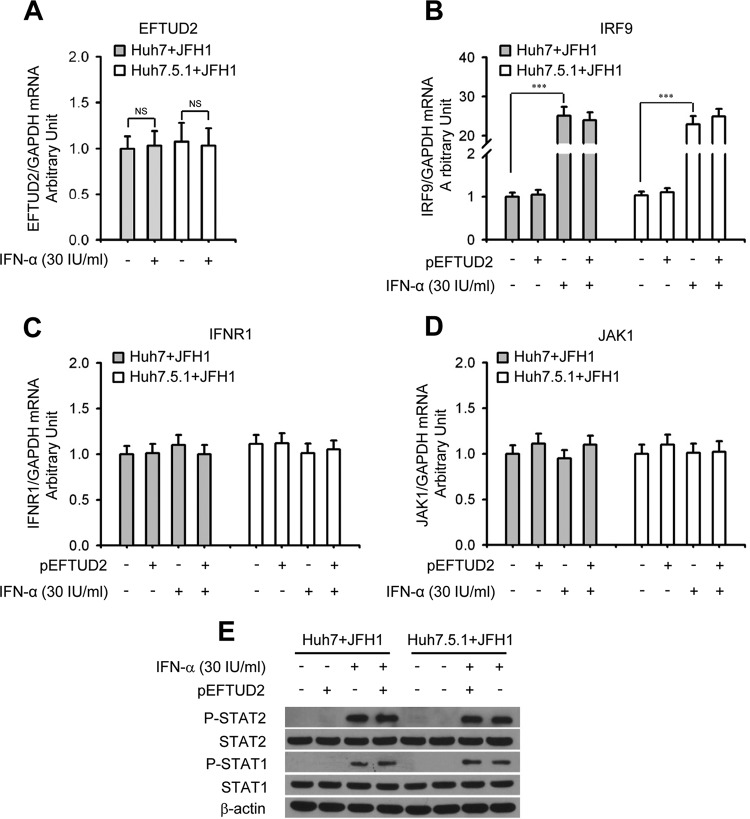

The EFTUD2-induced antiviral effect is independent of the classical IFN-induced JAK-STAT pathway.

We next assessed the relationship between EFTUD2 and the canonical IFN-induced JAK/STAT1 pathway and found that IFN-α treatment had no impact on EFTUD2 mRNA expression in either Huh7 or Huh7.5.1 cells with JFH1 infection (Fig. 8A), demonstrating that EFTUD2 expression is not regulated by IFN-α. Furthermore, we found that IFN-α significantly increased mRNA expression of IRF9 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 8B) but not of IFNR1 and JAK1 (Fig. 8C and D) in JFH1-infected Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells. However, EFTUD2 overexpression had no effect on mRNA expression levels of IFNR1, JAK1, and IRF9 in JFH1-infected Huh7 or Huh7.5.1 cells (Fig. 8B to D). Western blot analysis further indicated that EFTUD2 overexpression did not induce phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2 (STAT1/2) in JFH1-infected Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells without IFN-α treatment (Fig. 8E), indicating that EFTUD2's antiviral activity is independent of the IFN-induced JAK-STAT pathway.

FIG 8.

EFTUD2 overexpression does not induce JAK-STAT component expression and phosphorylation of STAT1/STAT2 in JFH1-infected Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells. (A) Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were incubated with IFN-α or mock treated for 24 h. mRNA expression of EFTUD2 was determined by qPCR. (B to D) Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with pEFTUD2 or empty vector for 48 h and infected with HCV JFH1 (MOI of 0.2) for 12 h and then incubated with IFN-α or mock treated for another 24 h. mRNA expression of IRF9, IFNR1, and JAK1 was determined by qPCR. (E) HCV JFH1-infected Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with pEFTUD2 or empty vector for 24 h before incubation with 30 IU/ml IFN-α or mock treated for 15 min. STAT1, STAT1 phosphorylation (P-STAT1), STAT2, and STAT2 phosphorylation (P-STAT2) were assessed by Western blotting.

DISCUSSION

The host innate immune system senses HCV and elicits local antiviral defenses to control infection. However, the majority of individuals infected with HCV fail to mount an adequate immune response to clear infection. The strong association of a polymorphism of the innate immune gene IFNL3 with spontaneous HCV clearance supports the importance of the innate immune apparatus to the outcome of viral infection (34). In this study, we discovered a novel innate immune regulator, EFTUD2, and elucidated how it activates RLR signaling and coordinates with its downstream molecules, RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3, to induce ISG expression and exert an anti-HCV effect.

EFTUD2 is a GTPase responsible for pre-mRNA splicing and was recently identified as a novel regulator of innate immunity (29). Using a genome-wide siRNA screen, our laboratory recently identified EFTUD2's role in restricting HCV infection. In this study, we confirm that EFTUD2 expression can restrict HCV replication independently of IFN. The induction of ISG expression by EFTUD2 indicates its role in innate immune regulation. HCV has developed multiple strategies to evade the innate immune response. For example, HCV NS3-NS4A blocks RIG-I signaling and cleaves MAVS protein to attenuate innate immunity (35). Our previous studies have demonstrated that HCV infection, HCV core protein, or NS5A protein expression selectively decrease phospho-STAT1 (P-STAT1) accumulation to block the type I IFN pathway response (7, 8, 9). In this study, we found that HCV evaded the restriction of EFTUD2 by downregulating its expression, providing another mechanism for HCV immune evasion. We therefore speculate that HCV, like other persistent viral infections, has evolved many mechanisms to disarm the innate immune system, including through inhibition of EFTUD2 expression. Further characterization of mechanisms by which HCV reduces EFTUD2 expression is warranted.

Furthermore, we demonstrated that EFTUD2-induced ISG expression was dependent on cytosolic RLR signaling, indicating that RLRs transduce the EFTUD2-induced antiviral response. RLRs, including RIG-I and MDA5, sense viral RNAs as foreign invaders in the cytosol and subsequently bind through their N-terminal caspase recruitment domains (CARDs) to the signaling adaptor MAVS (36). This binding activates the kinases TBK1 and IKKε, which phosphorylate IRF3 (37). Upon phosphorylation, IRF3 dimerizes, translocates to the nucleus, and subsequently induces the type I interferon (IFN) genes and ISG expression that are critical for antiviral activity (38, 39). Although RIG-I and MDA5 have highly homologous structures consisting of two CARD domains, a DEXD/H box RNA helicase, and a C-terminal domain (CTD), RIG-I and MDA5 sense distinct subsets of viral RNAs (40). According to previous reports, RIG-I detects paramyxoviruses, influenza virus, and vesicular stomatitis virus. However, MDA5 mainly senses picornaviruses (41, 42). It has been shown that RIG-I recognizes HCV to induce an innate immune response (3). In contrast, MDA5's role in the innate immune response to HCV has been uncertain. In this study, we identified EFTUD2 as an upstream immune effector upregulating the expression of RIG-I and MDA5 to induce ISGs. RIG-I's pivotal role in HCV innate immunity was confirmed. Furthermore, we showed that the expression of MDA5 inhibited HCV infection in an RIG-I-dependent manner, indicating that RIG-I and MDA5 each induce innate immunity against HCV.

As a downstream kinase of the RIG-I/MDA5 signaling pathway, TBK1 has the ability to phosphorylate transcription factor IRF3 at Ser396. The RLR inhibitor BX795 acts as an ATP competitive inhibitor of TBK1 to inhibit the catalytic activity of TBK1-catalyzed phosphorylation of IRF3 and decreases type I interferon production in mesenchymal stem cells (43, 44). In this study, we report, for the first time, that BX795 abrogates EFTUD2-induced IRF3 activation and ISG expression by blocking TBK1 signaling in JFH1-infected Huh7 cells. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the RIG-I/MDA5 downstream effector TBK1 is required to activate IRF3 and ISG expression in EFTUD2-induced anti-HCV activity. Thus, RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3 are EFTUD2 downstream regulators that interact to induce ISG expression. It is known that EFTUD2 encodes a GTPase, which is a component of the spliceosome complex, and processes precursor mRNAs to produce mature mRNAs. The intranuclear distribution of EFTUD2 suggests that it participates in pre-mRNA spicing at a posttranscriptional stage.

The JAK-STAT pathway is the dominant signaling cascade for the transcription of many ISGs. The binding of IFN to its receptor leads to the activation of receptor-associated Janus-activated kinase 1 (JAK1) and tyrosine kinase 2 (Tyk2) (45, 46). The activated kinases phosphorylate the downstream signal transducer and STAT1 and STAT2. The activated STAT1/2 complex combines with IRF9 in a complex that binds to the IFN-stimulated response elements (ISREs) on cellular DNA, leading to the expression of multiple ISGs, including MxA, OAS3, and PKR (47). In this study, we found that EFTUD2-induced ISG expression was independent of the JAK-STAT pathway, highlighting the existence and importance of a JAK-STAT-independent innate immune response.

In general, ISG expression accompanies type I interferon (IFN-α and IFN-β) induction upon activation of the RIG-I/IRF3 pathway (39, 48). In this study, the level of IFN-α/β was under the limit of detection (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] kits; BD Biosciences) in the supernatant of JFH1-infected Huh7 cells or Huh7.5.1 cells after pEFTUD2 overexpression (data not shown). Furthermore, JAK-STAT was not activated after pEFTUD2 overexpression. Therefore, EFTUD2's role in induction of endogenous IFN is negligible in our hepatocyte-based cell lines. We do not rule out a role for EFTUD2 in inducing IFN secretion in the liver, considering the existence of resident or infiltrating immune cells, such as plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and Kupffer cells, that can produce IFN after stimulation by viral products from hepatocytes (10). It will be of interest to investigate EFTUD2's role in inducing IFN induction in the liver using other cell types or mouse models.

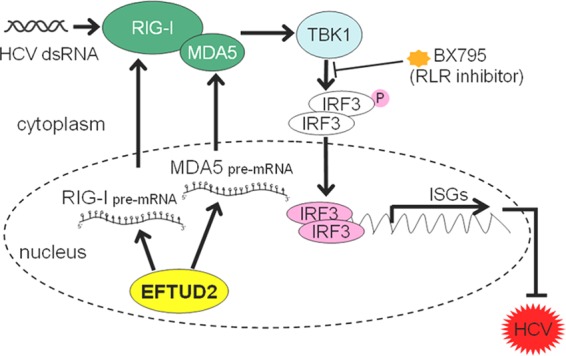

Based on our findings, we propose a model of EFTUD2 in innate immune regulation (Fig. 9), in which EFTUD2 regulates RIG-I/MDA5 mRNA expression through splicing and then activates TBK1 and IRF3 to induce classical ISG expression, independent of IFN, to exert its antiviral effect.

FIG 9.

A proposed model for EFTUD2 in inhibition of HCV infection. EFTUD2 upregulates RIG-I/MDA5 through mRNA editing to activate TBK1 and IRF3, thus inducing ISG production to inhibit HCV infection. dsRNA, double-stranded RNA.

In summary, we identified EFTUD2 as a novel innate immune regulator against HCV and elucidated its interaction with its downstream regulators RIG-I, MDA5, TBK1, and IRF3 to induce ISG expression and inhibit HCV infection, broadening our understanding of the HCV innate immune response and providing a possible new antiviral strategy targeting this novel regulator of the innate response.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the following investigators and institutes for supplying the reagents listed here: Takaji Wakita, Japan National Institute of Infectious Diseases (infectious HCV virus JFH1 DNA construct); Francis Chisari, Scripps Institute, La Jolla, CA (Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cell lines); and Michaela Gack, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA (pRIG-I, pΔRIG-I, and pMDA5).

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 81271713 (C.Z.), National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 81170386 (H.Z.), an NIH-MGH Center for Human Immunology Pilot/Feasibility Study grant (W.L.), and NIH grants DA033541 (R.T.C.), DK098079 (R.T.C.), and AI082630 (R.T.C.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Lavanchy D. 2009. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int 29(Suppl 1):74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bostan N, Mahmood T. 2010. An overview about hepatitis C: a devastating virus. Crit Rev Microbiol 36:91–133. doi: 10.3109/10408410903357455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sumpter R Jr, Loo YM, Foy E, Li K, Yoneyama M, Fujita T, Lemon SM, Gale M Jr. 2005. Regulating intracellular antiviral defense and permissiveness to hepatitis C virus RNA replication through a cellular RNA helicase, RIG-I. J Virol 79:2689–2699. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2689-2699.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang N, Liang Y, Devaraj S, Wang J, Lemon SM, Li K. 2009. Toll-like receptor 3 mediates establishment of an antiviral state against hepatitis C virus in hepatoma cells. J Virol 83:9824–9834. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01125-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen HR. 2013. Emerging concepts in immunity to hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Invest 123:4121–4130. doi: 10.1172/JCI67714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metz P, Reuter A, Bender S, Bartenschlager R. 2013. Interferon-stimulated genes and their role in controlling hepatitis C virus. J Hepatol 59:1331–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumthip K, Chusri P, Jilg N, Zhao L, Fusco DN, Zhao H, Goto K, Cheng D, Schaefer EA, Zhang L, Pantip C, Thongsawat S, O'Brien A, Peng LF, Maneekarn N, Chung RT, Lin W. 2012. Hepatitis C virus NS5A disrupts STAT1 phosphorylation and suppresses type I interferon signaling. J Virol 86:8581–8591. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00533-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin W, Choe WH, Hiasa Y, Kamegaya Y, Blackard JT, Schmidt EV, Chung RT. 2005. Hepatitis C virus expression suppresses interferon signaling by degrading STAT1. Gastroenterology 128:1034–1041. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin W, Kim SS, Yeung E, Kamegaya Y, Blackard JT, Kim KA, Holtzman MJ, Chung RT. 2006. Hepatitis C virus core protein blocks interferon signaling by interaction with the STAT1 SH2 domain. J Virol 80:9226–9235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00459-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horner SM, Gale M Jr. 2013. Regulation of hepatic innate immunity by hepatitis C virus. Nat Med 19:879–888. doi: 10.1038/nm.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu B, Peisley A, Richards C, Yao H, Zeng X, Lin C, Chu F, Walz T, Hur S. 2013. Structural basis for dsRNA recognition, filament formation, and antiviral signal formation by MDA5. Cell 152:276–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito T, Hirai R, Loo YM, Owen D, Johnson CL, Sinha SC, Akira S, Fujita T, Gale M Jr. 2007. Proc Regulation of innate antiviral defenses through a shared repressor domain in RIG-I and LGP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:582–587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horner SM, Liu HM, Park HS, Briley J, Gale M Jr. 2011. Mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) form innate immune synapses and are targeted by hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:14590–14595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110133108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding Q, Cao X, Lu J, Huang B, Liu YJ, Kato N, Shu HB, Zhong J. 2013. Hepatitis C virus NS4B blocks the interaction of STING and TBK1 to evade host innate immunity. J Hepatol 59:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao H, Lin W, Kumthip K, Cheng D, Fusco DN, Hofmann O, Jilg N, Tai AW, Goto K, Zhang L, Hide W, Jang JY, Peng LF, Chung RT. 2012. A functional genomic screen reveals novel host genes that mediate interferon-alpha's effects against hepatitis C virus. J Hepatol 56:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lines MA, Huang L, Schwartzentruber J, Douglas SL, Lynch DC, Beaulieu C, Guion-Almeida ML, Zechi-Ceide RM, Gener B, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Nava C, Baujat G, Horn D, Kini U, Caliebe A, Alanay Y, Utine GE, Lev D, Kohlhase J, Grix AW, Lohmann DR, Hehr U, Böhm D, FORGE Canada Consortium, Majewski J, Bulman DE, Wieczorek D, Boycott KM. 2012. Haploinsufficiency of a spliceosomal GTPase encoded by EFTUD2 causes mandibulofacial dysostosis with microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet 90:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, Murthy K, Habermann A, Kräusslich HG, Mizokami M, Bartenschlager R, Liang TJ. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med 11:791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, Mandel RJ, Nguyen M, Trono D, Naldini L. 1998. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol 72:8463–8471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartosch B, Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. 2003. Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1-E2 envelope protein complexes. J Exp Med 197:633–642. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fusco DN, Brisac C, John SP, Huang YW, Chin CR, Xie T, Zhao H, Jilg N, Zhang L, Chevaliez S, Wambua D, Lin W, Peng L, Chung RT, Brass AL. 2013. A genetic screen identifies interferon-α effector genes required to suppress hepatitis C virus replication. Gastroenterology 144:1438–1449.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Jilg N, Shao RX, Lin W, Fusco DN, Zhao H, Goto K, Peng LF, Chen WC, Chung RT. 2011. IL28B inhibits hepatitis C virus replication through the JAK-STAT pathway. J Hepatol 55:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phan T, Beran RK, Peters C, Lorenz IC, Lindenbach BD. 2009. Hepatitis C virus NS2 protein contributes to virus particle assembly via opposing epistatic interactions with the E1-E2 glycoprotein and NS3-NS4A enzyme complexes. J Virol 83:8379–8395. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00891-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao F, Fofana I, Heydmann L, Barth H, Soulier E, Habersetzer F, Doffoël M, Bukh J, Patel AH, Zeisel MB, Baumert TF. 2014. Hepatitis C virus cell-cell transmission and resistance to direct-acting antiviral agents. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004128. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao F, Fofana I, Thumann C, Mailly L, Alles R, Robinet E, Meyer N, Schaeffer M, Habersetzer F, Doffoël M, Leyssen P, Neyts J, Zeisel MB, Baumert TF. 2015. Synergy of entry inhibitors with direct-acting antivirals uncovers novel combinations for prevention and treatment of hepatitis C. Gut 64:483–494. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jilg N, Lin W, Hong J, Schaefer EA, Wolski D, Meixong J, Goto K, Brisac C, Chusri P, Fusco DN, Chevaliez S, Luther J, Kumthip K, Urban TJ, Peng LF, Lauer GM, Chung RT. 2014. Kinetic differences in the induction of interferon stimulated genes by interferon-α and interleukin 28B are altered by infection with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 59:1250–1261. doi: 10.1002/hep.26653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin W, Tsai WL, Shao RX, Wu G, Peng LF, Barlow LL, Chung WJ, Zhang L, Zhao H, Jang JY, Chung RT. 2010. Hepatitis C virus regulates transforming growth factor β1 production through the generation of reactive oxygen species in a nuclear factor κB-dependent manner. Gastroenterology 138:2509–2518. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong J, Yuan Y, Wang J, Liao Y, Zou R, Zhu C, Li B, Liang Y, Huang P, Wang Z, Lin W, Zeng Y, Dai JL, Chung RT. 2014. Expression of variant isoforms of the tyrosine kinase SYK determines the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 74:1845–1856. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brownell J, Wagoner J, Lovelace ES, Thirstrup D, Mohar I, Smith W, Giugliano S, Li K, Crispe IN, Rosen HR, Polyak SJ. 2013. Independent, parallel pathways to CXCL10 induction in HCV-infected hepatocytes. J Hepatol 59:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Arras L, Laws R, Leach SM, Pontis K, Freedman JH, Schwartz DA, Alper S. 2014. Comparative genomics RNAi screen identifies Eftud2 as a novel regulator of innate immunity. Genetics 197:485–496. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.160499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhong J, Gastaminza P, Cheng G, Kapadia S, Kato T, Burton DR, Wieland SF, Uprichard SL, Wakita T, Chisari FV. 2005. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:9294–9299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503596102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutlu T, Nyström S, Gilljam M, Stellan B, Applequist SE, Alici E. 2012. Inhibition of intracellular antiviral defense mechanisms augments lentiviral transduction of human natural killer cells: implications for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 23:1090–1100. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grandvaux N, Servant MJ, ten Oever B, Sen GC, Balachandran S, Barber GN, Lin R, Hiscott J. 2002. Transcriptional profiling of interferon regulatory factor 3 target genes: direct involvement in the regulation of interferon-stimulated genes. J Virol 76:5532–5539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5532-5539.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helbig KJ, Lau DT, Semendric L, Harley HA, Beard MR. 2005. Analysis of ISG expression in chronic hepatitis C identifies viperin as a potential antiviral effector. Hepatology 42:702–710. doi: 10.1002/hep.20844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D, O'Huigin C, Kidd J, Kidd K, Khakoo SI, Alexander G, Goedert JJ, Kirk GD, Donfield SM, Rosen HR, Tobler LH, Busch MP, McHutchison JG, Goldstein DB, Carrington M. 2009. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature 461:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li XD, Sun L, Seth RB, Pineda G, Chen ZJ. 2005. Hepatitis C virus protease NS3/4A cleaves mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein off the mitochondria to evade innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:17717–17722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508531102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawai T, Takahashi K, Sato S, Coban C, Kumar H, Kato H, Ishii KJ, Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2005. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat Immunol 6:981–988. doi: 10.1038/ni1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy MY, Jones CT, Bieniasz P, Rice CM. 2011. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 472:481–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoneyama M, Fujita T. 2009. RNA recognition and signal transduction by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunol Rev 227:54–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lau DT, Fish PM, Sinha M, Owen DM, Lemon SM, Gale M Jr. 2008. Interferon regulatory factor-3 activation, hepatic interferon-stimulated gene expression, and immune cell infiltration in hepatitis C virus patients. Hepatology 47:799–809. doi: 10.1002/hep.22076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakhaei P, Genin P, Civas A, Hiscott J. 2009. RIG-I-like receptors: sensing and responding to RNA virus infection. Semin Immunol 21:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, Uematsu S, Jung A, Kawai T, Ishii KJ, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K, Tsujimura T, Koh CS, Reis e Sousa C, Matsuura Y, Fujita T, Akira S. 2006. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature 441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loo YM, Fornek J, Crochet N, Bajwa G, Perwitasari O, Martinez-Sobrido L, Akira S, Gill MA, García-Sastre A, Katze MG, Gale M Jr. 2008. Distinct RIG-I and MDA5 signaling by RNA viruses in innate immunity. J Virol 82:335–345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01080-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark K, Plater L, Peggie M, Cohen P. 2009. Use of the pharmacological inhibitor BX795 to study the regulation and physiological roles of TBK1 and IκB kinase epsilon: a distinct upstream kinase mediates Ser-172 phosphorylation and activation. J Biol Chem 284:14136–14146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang K, Wang J, Xiang AP, Zhan X, Wang Y, Wu M, Huang X. 2013. Functional RIG-I-like receptors control the survival of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Dis 4:e967. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darnell JE Jr, Kerr IM, Stark GR. 1994. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 264:1415–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stark GR, Darnell JE Jr. 2012. The JAK-STAT pathway at twenty. Immunity 36:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu XY, Kessler DS, Veals SA, Levy DE, Darnell JE Jr. 1990. SGF3, the transcriptional activator induced by interferon alpha, consists of multiple interacting polypeptide chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87:8555–8559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saito T, Owen DM, Jiang F, Marcotrigiano J, Gale M Jr. 2008. Innate immunity induced by composition-dependent RIG-I recognition of hepatitis C virus RNA. Nature 454:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature07106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]