Abstract

Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) and tetanus toxin (TeNT) are the most potent toxins for humans and elicit unique pathologies due to their ability to traffic within motor neurons. BoNTs act locally within motor neurons to elicit flaccid paralysis, while retrograde TeNT traffics to inhibitory neurons within the central nervous system (CNS) to elicit spastic paralysis. BoNT and TeNT are dichain proteins linked by an interchain disulfide bond comprised of an N-terminal catalytic light chain (LC) and a C-terminal heavy chain (HC) that encodes an LC translocation domain (HCT) and a receptor-binding domain (HCR). LC translocation is the least understood property of toxin action, but it involves low pH, proteolysis, and an intact interchain disulfide bridge. Recently, Pirazzini et al. (FEBS Lett 587:150–155, 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2012.11.007) observed that inhibitors of thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) blocked TeNT and BoNT action in cerebellar granular neurons. In the current study, an atoxic TeNT LC translocation reporter was engineered by fusing β-lactamase to the N terminus of TeNT [βlac-TeNT(RY)] to investigate LC translocation in primary cortical neurons and Neuro-2a cells. βlac-TeNT(RY) retained the interchain disulfide bond, showed ganglioside-dependent binding to neurons, required acidification to promote βlac translocation, and was sensitive to auranofin, an inhibitor of thioredoxin reductase. Mutation of βlac-TeNT(RY) at C439S and C467S eliminated the interchain disulfide bond and inhibited βlac translocation. These data support the requirement of an intact interchain disulfide for LC translocation and imply that disulfide reduction is a prerequisite for LC delivery into the host cytosol. The data also support a model that LC translocation proceeds from the C to the N terminus. βlac-TeNT(RY) is the first reporter system to measure translocation by an AB single-chain toxin in intact cells.

INTRODUCTION

The clostridial neurotoxins (CNTs) include tetanus toxin (TeNT) and botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs), serotypes A to G. The CNTs contain ∼35% primary sequence identity and ∼65% sequence conservation (1). CNTs are ∼150-kDa single-chain proteins which are cleaved into dichains that remain linked by an interchain disulfide bond (2). The dichain is composed of a light chain (LC), a Zn2+ protease, and a heavy chain (HC) that contains a translocation domain (HCT) and receptor-binding domain (HCR) (1). CNTs intoxicate neurons by a four-step mechanism: binding neuronal receptors by the HCR, entry by receptor-mediated endocytosis, HCT-mediated LC translocation, and cleavage of a cytosolic SNARE protein by the LC (3).

CNTs are potent toxins with an estimated 50% lethal dose (LD50) of ∼1 ng/kg of body weight for humans (4). Currently, tetanus toxoid immunization prevents tetanus, a spastic paralysis characterized by involuntary contraction of skeletal muscles (5), while there are no current vaccines that prevent botulism, a flaccid paralysis. In contrast, BoNT/A and BoNT/B are therapies for dystonias, spasms, and migraines (6–8). The potential to utilize BoNT to deliver therapies for treatment against neurological diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, or Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, requires a detailed understanding of mechanisms of CNT action.

The HCR domain of CNTs binds neuron-specific receptors. TeNT and BoNT/C bind dual gangliosides, while the HCRs of the remaining characterized BoNTs bind one ganglioside and a synaptic vesicle-associated protein (9–15). BoNTs enter synaptic vesicles upon membrane depolarization of motor neurons and act locally to inhibit acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction (16, 17). TeNT enters signaling endosomes shared by neurotrophin receptor p75NTR, avoiding intracellular degradation by transcytosis into the intersynaptic cleft where TeNT binds and enters inhibitory interneurons; cleavage of vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2) inhibits neurotransmitter vesicle fusion and the subsequent release of inhibitory neurotransmitters, such as glycine (18–21). Recent studies have implicated a role for multiple domains in the entry of full-length TeNT into primary neurons (22, 23).

Similar to other AB toxins, the HCT of CNTs translocate the catalytic LC into the host cytosol in response to vesicle acidification (24, 25). The HCT is comprised of an N-terminal belt region, which wraps around the LC, and a C-terminal 11-nm helical bundle (26). The mechanism of LC translocation, although not well understood, appears to be conserved among CNTs. LC translocation is triggered by pH acidification and a redox gradient, and it requires an intact interchain disulfide bridge, unfolding of the LC, and proteolytic cleavage to release the LC from the HC (27–29). Acidification stimulates a conformational change that leads to HCT insertion into the membrane and unfolding of the LC. Upon translocation into the cytosol, the LC refolds and the interchain disulfide is reduced, releasing the LC into the cytosol (30, 31). The LCs cleave soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment receptor (SNARE) proteins, which inhibits formation of tertiary complexes required for neurotransmitter vesicle fusion to the plasma membrane (32).

Recently, we engineered TeNT(R372A, Y375F) [TeNT(RY)], which is ∼125,000-fold reduced in toxicity relative to native TeNT and binds gangliosides with specificity and affinity similar to those of the HCR of TeNT (33). In the current study, a β-lactamase (βlac) was fused to TeNT(RY) to generate a reporter that allows mechanistic studies on the translocation process (vesicle entry, pH sensing, pore formation, and delivery of the LC). βlac-TeNT(RY) is the first single-chain AB toxin LC translocation reporter and is used to investigate the role of the interchain disulfide during LC translocation in intact cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Engineering and production of βlac-TeNT(RY) and βlac variants.

βlac-TeNT(RY) was engineered by amplifying the gene encoding Escherichia coli mature TEM-1 β-lactamase (βlac; residues 23 to 286; accession number YP_009082236) with 5′ SacI and 3′ AATII restriction sites. The LC of pTeNT(RY) (33) was amplified to add a 5′ AATII site, and the βlac gene was subcloned between the DNA encoding the 3×-FLAG epitope and TeNT(RY) (Fig. 1A) in pET28a [pβlac-TeNT(RY)]. βlac(S70A)-TeNT(RY), a catalytic null variant, and the interchain disulfide variant βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S, C467S) (see Fig. 7A) were engineered using mutagenesis primers designed for QuikChange II kit (Agilent) specifications. βlac-HCR/T (Fig. 1A) was engineered by subcloning the βlac gene containing 5′ SacI and 3′ BamHI sites into pET28a containing the receptor binding domain of TeNT (HCR/T) (34) between the 3×-FLAG epitope and HCR/T (pβlac-HCR/T). For each reporter, the open reading frames were sequenced to confirm DNA sequences. Expression plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3), selecting for kanamycin resistance. Confluent lawns (100-mm plates) of each transformant were inoculated into 400 ml of LB (Difco) supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and cultured for 3 h, with shaking (250 rpm) at 34°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.6 to 0.8 before addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and overnight culturing at 16°C. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 15 min and suspended in 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.9), 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, RNase, DNase, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) before lysis with a French press. The soluble fraction was centrifuged at 43,000 × g for 20 min and passed through a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate filter (Nalgene). TeNT(RY) or βlac-TeNT(RY) variants in the filtered, soluble fraction were purified by tandem gravity-chromatography using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose (Qiagen), p-aminobenzamidine-agarose (Sigma-Aldrich), and Strep-tactin Superflow high-capacity resin (IBA-LifeSciences); fractions containing the TeNT(RY) variants were dialyzed into 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.9), 100 mM NaCl, 40% glycerol and stored at −20°C. βlac-HCR/T was purified as described for HCR/T (34), and FLAG-HCR/A was purified as described previously (35). Typically, proteins were purified from 2.4 liters of E. coli, and soluble recovery was 2 mg/liter for TeNT(RY), 0.5 mg/liter for βlac-TeNT(RY) and variants, and 12 mg/liter for βlac-HCR/T.

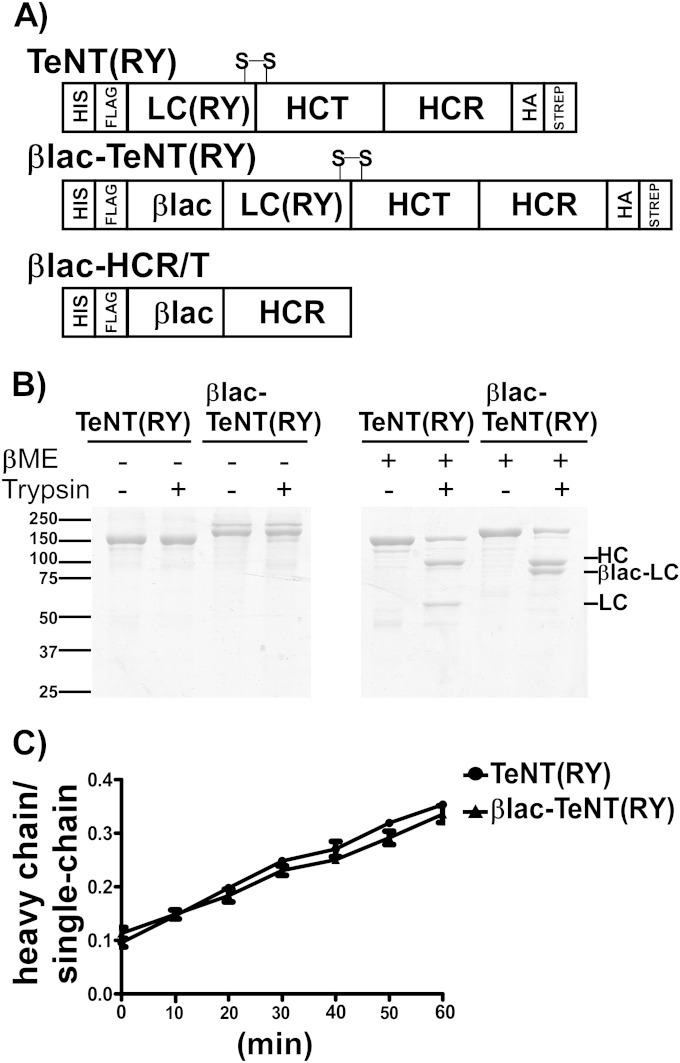

FIG 1.

Schematics of βlac-TeNT(RY) translocation reporter proteins. (A) βlac-TeNT(RY) is a chimeric protein containing the mature domain of βlac TEM-1 from E. coli fused to the N terminus of TeNT(RY). TeNT(RY) and βlac-TeNT(RY) contain N-terminal 6×-His and 3×-FLAG epitopes and C-terminal di-HA and Strep epitopes for purification and immunoprobing. S-S designates the interchain disulfide (C439-C467). βlac-HCR/T contains the mature domain of β-lactamase fused to the N terminus of HCR/T (865-1315). (B) TeNT(RY) and βlac-TeNT(RY) were incubated with trypsin (1/1,000, wt/wt) for 1 h at 37°C. The reaction mix was inhibited and boiled in oxidizing (−) or reducing (+) βME-SDS loading buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE. (C) TeNT(RY) and βlac-TeNT(RY) were incubated with trypsin (1/2,000, wt/wt) as described above, and samples were boiled in reducing buffer at the times indicated. Quantitation of the ratio of HC to single chain was measured and plotted; standard errors of the means (SEM) are shown.

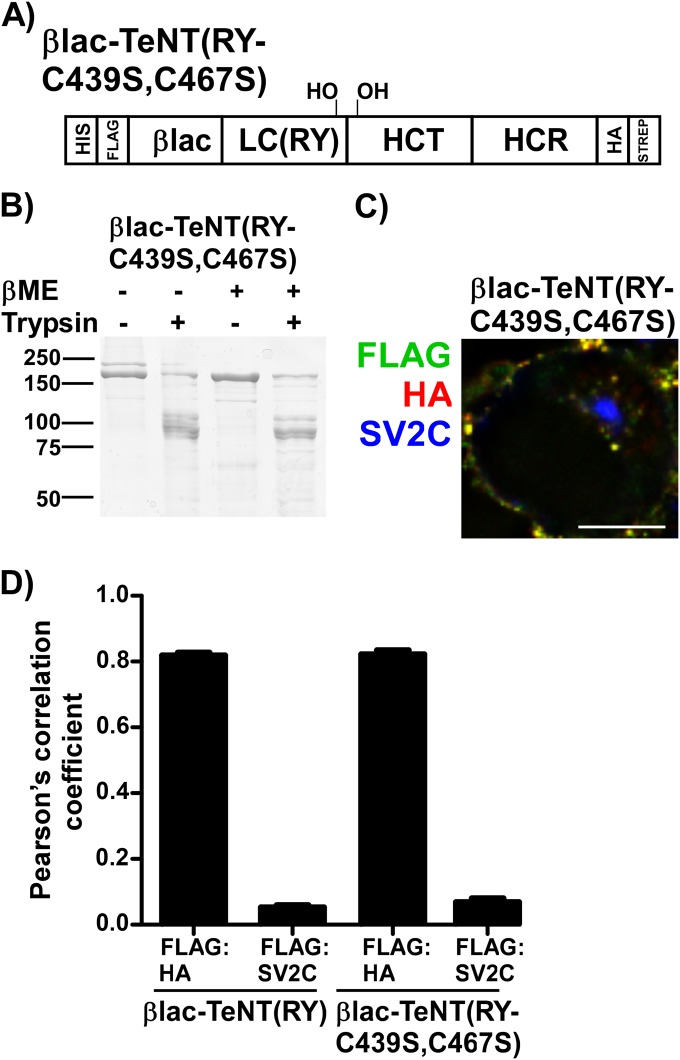

FIG 7.

Characterization of βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C67S). (A) Schematic of βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S). (B) Trypsin sensitivity of βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S) interchain variant subjected to oxidizing (−) or reducing (+) βME-SDS buffer followed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. (C) Representative deconvolved single cell of 40 nM single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S) following incubation for 20 min at 37°C with Neuro-2a cells. The scale bar is 10 μm. (D) Pearson's correlation coefficient of deconvolved cells was performed to assess FLAG-HA and FLAG with synaptic vesicle protein FLAG:SV2C; βlac-TeNT(RY) is shown for comparison.

In vitro βlac assay.

βlac was assayed in a 96-well format, using 10 nM βlac-TeNT(RY) or variants in 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.9), 50 nM NaCl with 2 μM fluorocillin green substrate (Life Technologies) in 120-μl reaction mixtures. The rate of fluorocillin green hydrolysis (fluorescence) was measured every 5 min using a 480/535 (excitation/emission) fluorescein filter on a Victor 3 microplate reader (PerkinElmer).

Trypsin sensitivity of TeNT variants.

βlac-TeNT(RY) and TeNT(RY) were incubated with trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:1,000 (wt/wt) trypsin to variant in 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.9), 50 mM NaCl for 1 h at 37°C. To assess the kinetics of trypsin digestion, 1:2,000 (wt/wt) trypsin to variant was incubated as described above with samples inhibited every 10 min with a 5 M excess of soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). Proteins were subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE (with or without beta-mercaptoethanol [βME]) and stained with Coomassie blue.

Cell culture protocols.

Reagents were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY) unless otherwise indicated. Neuro-2a cells (ATCC CCL-131), from Mus musculus neuroblastoma, were seeded (60,000 cells/well) on HCl-etched 12-mm glass coverslips in 24-well plates in minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 0.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1× penicillin-streptomycin, 0.1% sodium bicarbonate, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 1% nonessential amino acids in humidified 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were assayed 2 days after plating at around ∼70% confluence. E18 rat cortex from Sprague Dawley rat (BrainBits, LLC) were triturated to single cells as described by the supplier and plated in complete neurobasal medium (50,000 cells/well) on glass-bottom TIRF plates (MatTek). TIRF plates were precoated with 20 μg/ml poly–d-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight, followed by 3 μg/ml mouse laminin for 3 h, and equilibrated with neurobasal medium for 30 min in humidified 5% CO2 at 37°C before plating cells in complete neurobasal media. Complete neurobasal medium contains 1× B27, 1 mg/ml primacin (InvivoGen), and 140 μl GlutaMAX. Neurons were cultured for 10 to 14 days with a half-fresh medium change on days 4 and 7 postplating.

Entry of TeNT(RY) variants into Neuro-2a cells.

Two days after plating as described above, cells were loaded (10 μg/well) with sonicated ganglioside GT1b (Matreya) in MEM containing 0.5% FBS for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were washed with prewarmed Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and incubated with 40 nM TeNT(RY), βlac-TeNT(RY), or receptor binding domain of BoNT/A (HCR/A) at 37°C in low-K+ buffer (15 mM HEPES, 145 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4) for 20 min, when cells were washed and processed for immunofluorescence (described below).

Binding of TeNT(RY) variants on primary rat cortical neurons.

Single-chain TeNT(RY), βlac-TeNT(RY), and variants with mutations to the R and W ganglioside binding pockets (R1226L/W1289A) were incubated at 5, 10, 20, and 40 nM in precooled low-K+ buffer containing 17.5 nM CTxB-647 (Cholera toxin B subunit-Alexa 647; loading control) for 30 min on ice. Cells were washed with ice-cold DPBS and processed for immunofluorescence.

LC translocation assay.

Rat cortical neurons were incubated in prewarmed neurobasal media with 40 nM single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY) or variants for 1 h at 37°C. Neurons were washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution lacking Ca2+ and Mg2+ (HBSS−/−) (Life Technologies) and cooled to room temperature for 10 min before loading with 1 μM CCF2-AM (Life Technologies) and 1 mM probenecid (Life Technologies), an anion transport inhibitor, in HBSS−/− for 30 min. Neurons were washed and processed for immunofluorescence. The inhibitor-treated translocation assay was performed as described above, with the following preincubation modifications: bafilomycin A1, a vesicular ATPase inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich), was preincubated with neurons at 100, 200, and 400 nM in neurobasal media for 1 h at 37°C before aspiration and application of 40 nM single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY) in neurobasal media containing inhibitor at the indicated concentrations. The thioredoxin reductase inhibitor auranofin (Sigma-Aldrich) was preincubated with neurons at 0.125, 0.250, 0.500, and 1 μM for 1 h at 37°C before removal and addition of 40 nM single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY) in neurobasal media containing appropriate concentrations of inhibitor. After incubation with βlac-TeNT(RY) for 1 h at 37°C, cells were washed and loaded with CCF2 as described above before washing and fixation.

Immunofluorescence (IF).

Neuro-2a cells and primary cortical neurons were fixed as previously described (36) at room temperature for 15 min in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in DPBS (fixing solution). Cells were washed and permeabilized in DPBS plus 0.1% Triton-X and 4% formaldehyde for 15 min. Cells were blocked in 10% FBS, 2.5% cold-water fish skin gelatin, 0.1% Triton-X, and 0.05% Tween 20 for 15 min. Cells were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C with 1:1,000 neuron-specific nuclear protein (NeuN) (EMD Millipore), 1:12,000 FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich), 1:2,000 hemagglutinin (HA; Roche), 1:2,000 synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2C (SV2C) (Synaptic Systems), 1:400 wheat germ agglutinin, and 1:400 CTxB-647 (Life Technologies) in 5% FBS, 1% cold-water fish skin gelatin, 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X, and 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 in DPBS (antibody solution). Cells were washed 3× for 5 min each with DPBS plus 0.005% Tween 20. Alexa-conjugated secondary antibody was incubated for 1 h in antibody solution at room temperature before cells were washed again 3× as described above and incubated in fixing solution. For Neuro-2a cells, coverslips were mounted and cured in ProLong Gold (Life Technologies) on glass slides. For neurons, Citifluor AF-3 antifade reagent (Electron Microscopy Sciences) was added prior to analysis. Images were collected using a Nikon inverted microscope by epifluorescence using a CFI Plan Apo 60× oil objective (numeric aperture, 1.49) and a Photometrics CoolSnap HQ2 camera.

Data analysis.

Autofluorescence and fluorescence emitted by cells treated only with secondary Alexa-conjugated antibodies were used for background subtractions. For the trypsin digestion time course, samples were analyzed in reducing buffer by plotting the ratio of HC to the intact single-chain variant. For protein binding to neurons, neuron plasma membrane was localized with CTxB-647, and FLAG fluorescence was measured and normalized to that for CTxB-647. Ganglioside-independent binding was attributed to fluorescence measured in TeNT(RY) RW, a variant of TeNT(RY) that has mutations in the two ganglioside-binding pockets of the HCR. For the measurement of LC translocation, clusters of 3 to 6 neurons were located using NeuN-positive fields and assayed for FLAG intensity, uncleaved CCF2 substrate, and cleaved CCF2 substrate. At least 25 fields were analyzed per experiment, and at least 3 independent experiments were performed. Ratiometric analysis of the emission wavelength (Em) corresponding to net cleaved CCF2/net uncleaved CCF2 (excitation wavelength [Ex], 409 nm; Em, 447 nm/520 nm), as well as net cleaved CCF2 normalized to net FLAG intensity, was determined.

Measurement of TeNT(RY) and βlac-TeNT(RY) variant entry into Neuro-2a cells.

Cells were located with SV2C-positive fields, and Z-stacks were taken at 0.4-μm steps followed by cropping individual cells and blinded deconvolution to estimate the point spread function (PSF) with 15 iterations. Nikon software assessed Pearson's correlation colocalization (PCC) values between selected slices. PCC was measured between the N-terminal FLAG and C-terminal HA of TeNT(RY) variant epitopes, as well as the N-terminal FLAG of TeNT(RY) variants and SV2C, a synaptic vesicle marker protein.

Statistics.

Student's unpaired, two-tailed t test was utilized to determine if two data sets were significantly different where appropriate.

RESULTS

βlac-TeNT(RY) as a model for studying LC translocation.

There are several approaches to measure LC translocation to the cytosol, including channel conductance using patch clamping, ion release from liposomes, and substrate cleavage in cultured cells (31, 37–39). To investigate LC translocation from intracellular vesicles into the cytosol of intact neuronal cells, βlac was engineered to the N terminus of the atoxic TeNT(RY). Earlier studies have utilized the βlac reporter to measure cytosolic delivery of the lethal factor of anthrax toxin, Yersinia type III effectors, and domains within MARTXVC (40–43). Delivery of the βlac fusion proteins into the cytosol was measured by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) disruption of CCF2, a fluorescent substrate containing a coumarin and fluorescein molecule connected by a cephalosporin backbone cleaved by βlac (44).

The gene for the mature domain of E. coli TEM-1 βlac (23-286) was subcloned 5′ to the gene encoding TeNT(RY) (Fig. 1A, top) (33, 44). βlac-TeNT(RY) (Fig. 1A, middle) retained N-terminal 6×-His and 3×-FLAG epitopes and C-terminal HA and Strep epitopes for purification and intracellular detection (33). βlac-TeNT(RY) expressed as a soluble ∼180-kDa protein in E. coli. Trypsin-digested TeNT(RY) and βlac-TeNT(RY) resolved by SDS-PAGE in oxidizing conditions (without βME) as single bands of 150 kDa and 180 kDa, respectively (Fig. 1B, left). Trypsin-digested TeNT(RY) and βlac-TeNT(RY) resolved by SDS-PAGE in reducing conditions (with βME) as two bands; TeNT(RY) possessed a 50-kDa N-terminal LC and a 100-kDa C-terminal HC, while βlac-TeNT(RY) possessed an an 80-kDa N-terminal βlac-LC and a 100-kDa C-terminal HC (Fig. 1B, right). Thus, fusion of βlac onto the N terminus of TeNT(RY) did not alter the preferred trypsin cleavage between the interchain disulfide, and, like TeNT(RY), the βlac-TeNT(RY) dichain remained associated with the interchain disulfide (C439-C467). To assess the kinetics of trypsin digestion between TeNT(RY) and βlac-TeNT(RY), the ratio of HC to the single chain in reduced samples was plotted over time and indicated the two proteins were similarly cleaved (Fig. 1C). βlac-HCR/T also was engineered as a control to measure cellular CCF2 cleavage by a TeNT variant that lacked the HCT. βlac-HCR/T contained an N-terminal 3×-FLAG epitope which allowed the measurement of cell interactions independent of the HCT (Fig. 1A, bottom) (34). βlac-HCR/T was expressed as a soluble ∼80-kDa protein in E. coli.

Cell-based assays were performed in either Neuro-2a cells, a mouse neuroblastoma cell line, or rat primary cortical neurons. Neuro-2a cells measured ganglioside-dependent binding and compared intracellular trafficking of the TeNT(RY) variants, since primary neurons have overlapping dendrites and axons that complicate quantification of intracellular movement. Primary cortical neurons measured βlac translocation, since βlac translocation was more efficient in primary cortical neurons than in Neuro-2a cells.

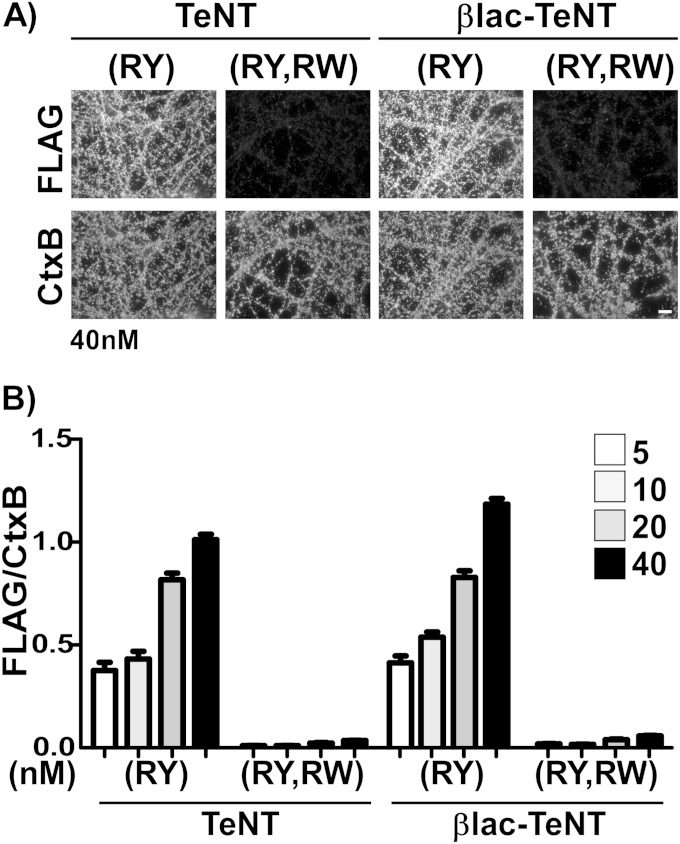

Binding of βlac-TeNT(RY) to cortical neurons.

TeNT interacts with both acidic lipids and gangliosides (45–48) and utilizes dual gangliosides to bind and enter neuronal cell lines (9). Ganglioside-dependent binding and entry is attributed to two binding regions within the receptor binding domain (HCR), termed the sialic acid R and the ganglioside W pockets (34). To assess if βlac-TeNT(RY) binding to neurons also was ganglioside dependent, βlac-TeNT(RY), TeNT(RY), and corresponding RW variants, where RW signifies the double-pocket mutations R1226L and W1289A, were incubated with primary rat cortical neurons on ice. Cholera toxin B subunit-Alexa 647 (CTxB-647), which binds GM1, was coincubated as a loading control and membrane marker for FLAG epitope normalization. Both TeNT(RY) and βlac-TeNT(RY) showed a dose-dependent binding to cortical neurons (Fig. 2B), while TeNT(RY, RW) and βlac-TeNT(RY,RW) showed negligible binding. At 40 nM, βlac-TeNT(RY) had an ∼1.2-fold increased binding on neurons compared to TeNT(RY) (Fig. 2A and B). Overall, the data established that βlac-TeNT(RY) bound neurons in a ganglioside-dependent manner, similar to TeNT(RY).

FIG 2.

TeNT(RY) and variants binding to cortical neurons. (A) Primary rat cortical neurons were incubated with 5 to 40 nM single-chain TeNT(RY), βlac-TeNT(RY), or RW variants with ganglioside pocket mutations (R1226L, W1289A) and 17.5 nM CTxB-647, as a loading control, at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were washed, fixed, and probed for N-terminal FLAG epitope. The scale bar is 10 μm. (B) Quantification of binding assessed by net FLAG signal normalized to CTxB-647. TeNT (at 40 nM) was set to 1.0; values are shown with SEM.

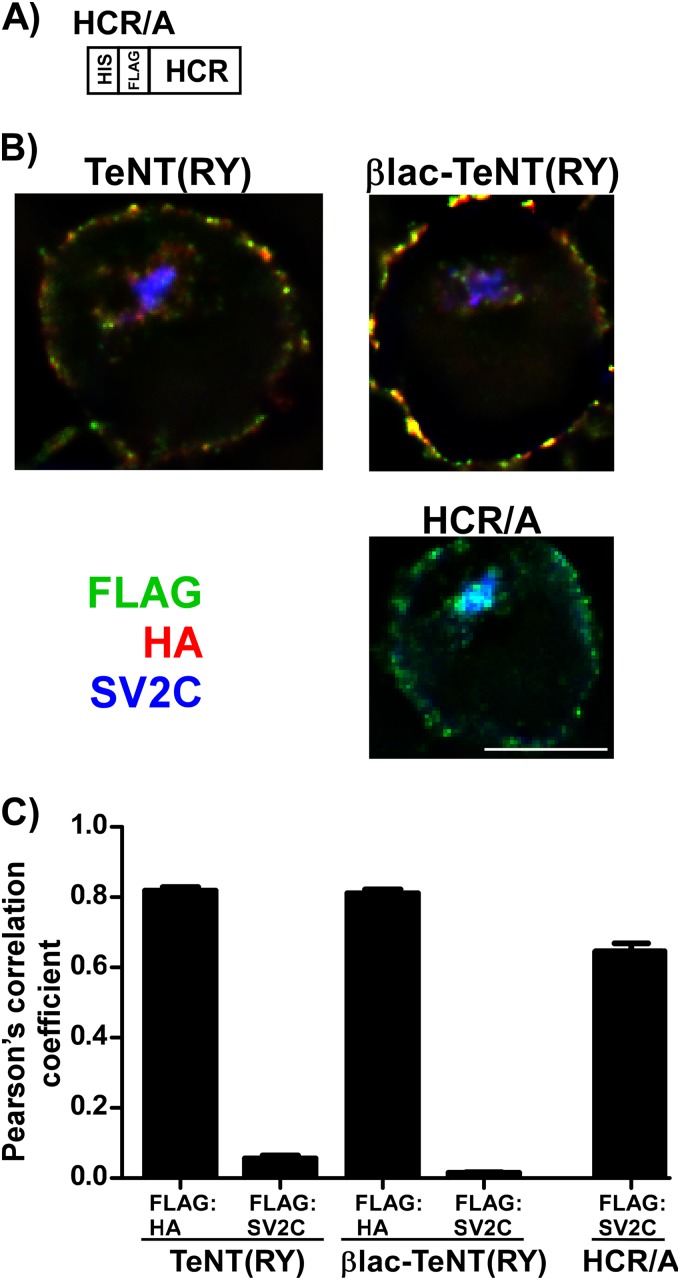

βlac-TeNT(RY) binding and entry into Neuro-2a cells.

CNT internalization and localization has been measured in Neuro-2a cells. TeNT(RY) and HCR/T entered and segregated from the synaptic vesicle marker SV2C, while the heavy-chain receptor of BoNT/A (HCR/A) colocalized with SV2C (33). To establish if βlac-TeNT(RY) enters and localizes similarly to TeNT(RY), Neuro-2a cells preloaded with GT1b were incubated with βlac-TeNT(RY) and TeNT(RY), and intracellular TeNT was analyzed in individual cells by microscopy using whole-field Z-stacks subjected to deconvolution. Internalized TeNT(RY), βlac-TeNT(RY), and HCR/A localized to the perinuclear region (Fig. 3B). Measurement of colocalization using Pearson's correlation coefficients showed that the N-terminal (FLAG) epitopes for βlac-TeNT(RY) and TeNT(RY) segregated from SV2C, indicating that neither protein colocalized with SV2C-positive vesicles, while HCR/A colocalized (Fig. 3C). N-terminal FLAG and C-terminal (HA) epitopes of TeNT(RY) and βlac-TeNT(RY) remained colocalized in vesicles and on the cell membrane (Fig. 3C), comparable to the colocalization of the epitopes at 4°C (data not shown). We have examined the localization of the synaptic vesicle marker proteins SV2C, VAMP2, and synaptophysin and found that the three proteins colocalize within these vesicles in addition to HCR/A, but not HCR/T, supporting the presence of a mixed and segregated population of vesicles within this intracellular pool. These results support a physiological distribution of these intracellular vesicles. Thus, βlac-TeNT(RY) internalization follows a ganglioside-dependent pathway, similar to TeNT(RY).

FIG 3.

Entry of βlac-TeNT(RY) and TeNT(RY) into Neuro-2a cells. (A) Schematic of HCR/A with N-terminal FLAG epitope. Ganglioside-enriched Neuro-2a cells were incubated with 40 nM single-chain TeNT(RY), βlac-TeNT(RY), or FLAG-tagged HCR/A at 37°C for 20 min. Cells were washed, fixed, and probed for the N-terminal epitope (FLAG), the C-terminal epitope (HA), and SV2C (synaptic vesicle marker protein). (B) Randomized single cells containing SV2C signal were deconvolved, and a representative slice is shown. The scale bar is 10 μm. (C) Pearson's correlation coefficients were determined for FLAG:HA and FLAG:SV2C; values are shown with SEM.

βlac-TeNT(RY) cleaves CCF2 in rat primary cortical neurons.

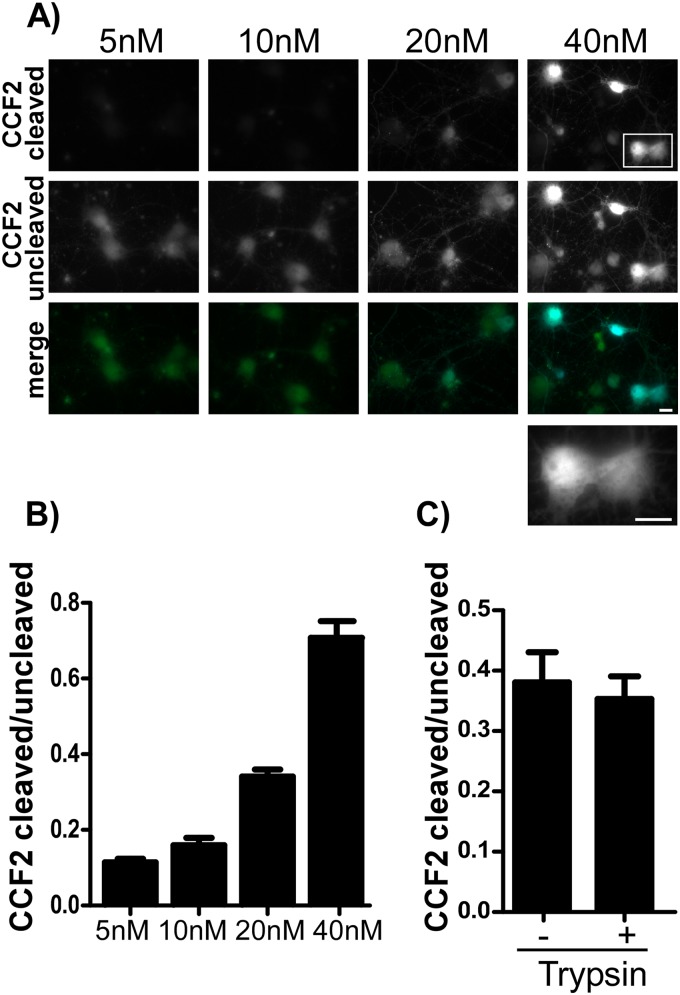

The CCF2-βlac reporter system identified immune cells targeted by Yersinia pestis (41) following type III secretion system delivery of βlac-effector fusions. CCF2-AM, a membrane-permeable and nonfluorescent substrate, diffuses into a cell and is processed by cytosolic host esterases to yield membrane-impermeable, fluorescent CCF2 (44). CCF2 undergoes FRET (Ex of 409 nm to Em of 520 nm), which is lost upon cleavage by βlac, yielding a blue-shifted fluorescence (Ex of 409 nm to Em of 447 nm). Translocation was quantified by taking the cleaved CCF2/uncleaved CCF2 ratio (Em of 447 nm/520 nm) for βlac-TeNT(RY)-treated cells. In primary cortical neurons, single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY) cleaved CCF2 (Fig. 4A, top), and cleaved CCF2 intensity increased proportional to increasing amounts of βlac-TeNT(RY) added to neurons (Fig. 4B). Cleaved CCF2 appeared throughout the cell cytosol (Fig. 4A, lower magnified cell bodies), consistent with the translocation of βlac from the lumen of the endosome into the host cell. The cleaved CCF2 was comparable in both trypsin-digested dichain and single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY)-treated neurons (Fig. 4C). In cells positive for translocation (cleaved CCF2), an increase in uncleaved CCF2 also was observed. For cells with a translocated reporter, cleaved CCF2 may shift the intact substrate equilibrium, increasing diffusion of extracellular uncleaved CCF2 into those cells. This is the first report that βlac can be used as a reporter to measure translocation by a single-chain AB toxin in intact cells.

FIG 4.

CCF2 cleavage in primary neurons by βlac-TeNT(RY). (A) Primary rat cortical neurons were incubated with 5 to 40 nM single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY) for 1 h at 37°C, followed by loading with CCF2-AM at 25°C for 30 min. Cell bodies were magnified to show cytosolic staining. The scale bar is 10 μm. (B) Quantification of random fields with ratios of cleaved/uncleaved CCF2 substrate (Em, 447 nm/520 nm) in arbitrary units shown with SEM. (C) Quantification of random fields with cleaved/uncleaved ratios for cortical neurons incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 40 nM trypsin-digested or single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY); values with SEM are shown.

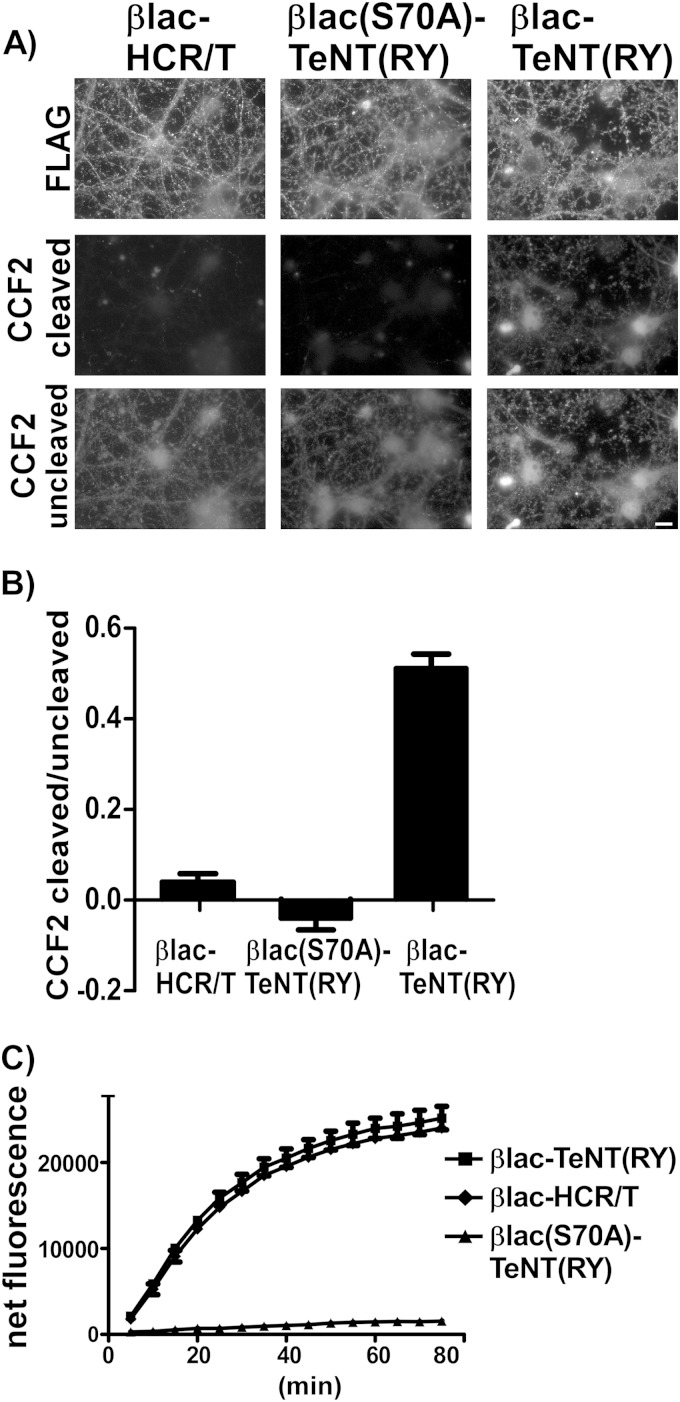

βlac-HCR/T was engineered to determine if CCF2 cleavage was HCT dependent, while the catalytically inactive βlac(S70A)-TeNT(RY) was engineered to determine if CCF2 cleavage required a functional βlac. While βlac-TeNT(RY) and βlac-HCR/T contained comparable in vitro βlac activity, the S70A mutation reduced βlac catalysis to background levels (Fig. 5C). βlac-HCR/T, βlac(S70A)-TeNT(RY), and βlac-TeNT(RY) associated with primary cortical neurons with similar efficiency (Fig. 5A); however, only βlac-TeNT(RY) cleaved CCF2 (Fig. 5B). These data indicate that CCF2 cleavage is due to translocation of a functional βlac. A third βlac reporter variant containing βlac fused directly to the HC of TeNT (βlac-HC/T) was engineered; however, the protein was not stable when expressed in E. coli, preventing a direct assessment of the contribution of the LC in βlac-TeNT(RY) translocation (data not shown).

FIG 5.

βlac translocation by βlac-TeNT(RY). (A) βlac-HCR/T (40 nM), single-chain βlac-S70A-TeNT(RY) (catalytic null), and single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY) were incubated with primary rat cortical neurons for 1 h at 37°C before addition of CCF2-AM at 25°C for 30 min. The scale bar is 10 μm. (B) Quantification of random fields of net cleaved/uncleaved substrate (Em 447/520 nm), in arbitrary units, is shown for each reporter with SEM. (C) In vitro βlac activity was measured over time, using 10 nM βlac reporter proteins and 2 μM fluorocillin green, a colorless substrate that emits fluorescence when cleaved.

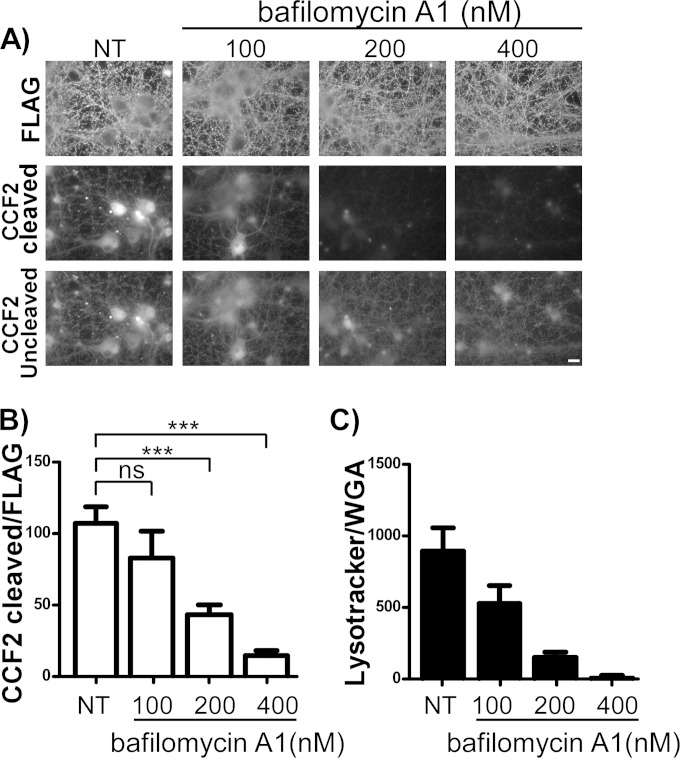

βlac translocation by βlac-TeNT(RY) is sensitive to bafilomycin A1.

TeNT and BoNT, like diphtheria toxin, require low pH for productive LC translocation. To determine if low pH contributes to βlac translocation, cells were treated with bafilomycin A1, an inhibitor of vesicular ATPase (vATPase), and βlac translocation was assessed. Preincubation of primary cortical neurons with increasing bafilomycin A1 concentrations resulted in a proportional reduction in CCF2 cleavage by βlac-TeNT(RY) (Fig. 6A and B). In addition, as bafilomycin A1 inhibition increases, there is a decrease in the observed cleavage of CCF2, which results in less import of uncleaved CCF2 relative to that of untreated cells. In this and subsequent experiments, cleaved CCF2 is normalized to FLAG epitope intensity. Quantification in this manner eliminated false negatives caused by the large denominator (uncleaved CCF2) due to increased uptake of uncleaved CCF2 in cells with cleaved CCF2. These data suggest that βlac translocation is pH dependent (Fig. 6B). LysoTracker (a reagent that accumulates in acidic vesicles) confirmed that bafilomycin A1 inhibited vesicle acidification, as LysoTracker fluorescence decreased in bafilomycin A1-treated neurons compared to levels in untreated neurons (Fig. 6C). These data indicate that βlac translocation, like LC translocation by TeNT, requires a pH-dependent response. The similarities of βlac translocation by βlac-TeNT(RY) with TeNT suggests βlac-TeNT(RY) can be used as a model to study the cellular and molecular properties of LC translocation by TeNT.

FIG 6.

βlac translocation is bafilomycin A1 sensitive. (A) Neurons were preincubated for 1 h at 37°C with bafilomycin A1 (100, 200, or 400 nM). The medium was aspirated and replaced with 40 nM single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY) in media containing bafilomycin A1 at the concentrations indicated for 1 h at 37°C, and cells were loaded with CCF2-AM for 30 min at 25°C. NT indicates an untreated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) carrier alone. The cells were washed before fixation and processed for IF. The scale bar is 10 μm. (B) Quantification of βlac-TeNT(RY) translocation to random fields by normalized cleavage (Em, 447 nm) normalized to net FLAG signal in arbitrary units shown with SEM. Student's t test indicates P < 0.0001 (***) between untreated and treated conditions at the concentrations indicated. ns, not significant. (C) Quantification of 50 nM LysoTracker controls incubated with neurons at the bafilomycin A1 concentrations used for panel A normalized to glycolipid marker wheat germ agglutinin-647 (WGA), with SEM.

βlac-TeNT(RY) requires an interchain disulfide for βlac translocation.

While earlier studies reported that chemical reductants reduced TeNT neurotoxicity in mice by ∼80-fold (28), the cellular basis for the reduction in toxicity has not been established. Patch clamp studies reported that in the presence of membrane-permeable chemical reductant, BoNT/A and BoNT/E produced channels of lower picosiemens (pS) than unreduced BoNT/A and BoNT/E and that chemically reduced BoNT/A and BoNT/E channels remained occluded, implying that translocation was arrested at an intermediate preceding LC delivery into the cytosol (27).

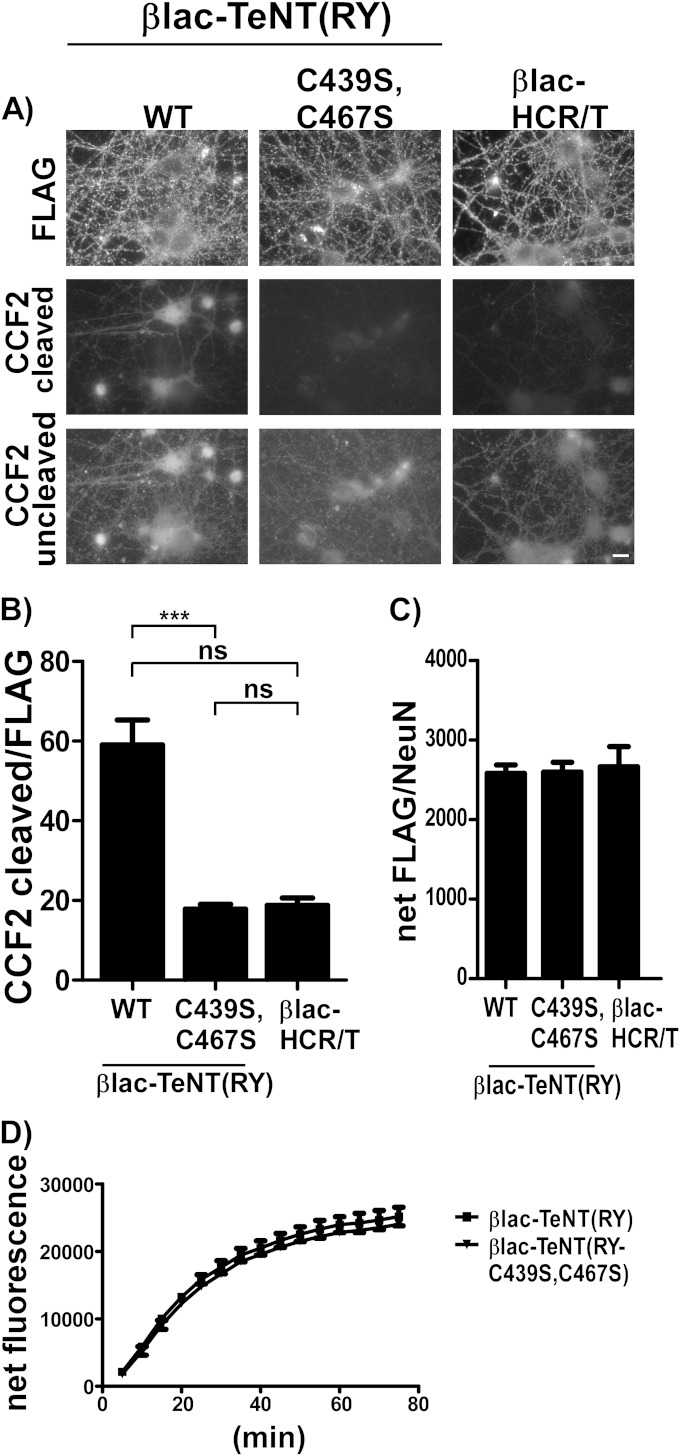

The role of an intact interchain disulfide (C439-C467) in LC translocation by βlac-TeNT(RY) was assessed next. Directed mutagenesis, rather than chemical reduction, eliminated the interchain disulfide without reduction of the intrachain disulfide (C869-C1093) within the HCR (49). βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S) was produced as a soluble protein (Fig. 7A and B) that did not form an interchain disulfide under either oxidized and reduced conditions when digested by trypsin. βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S), like βlac-TeNT(RY), contained bands at ∼100 kDa (HC) and an 80-kDa βlac-LC but also showed additional minor cleavage products, indicating more sites were accessible to cleavage in the interchain disulfide variant upon digestion by trypsin (Fig. 7B). Additional cleavage is not unexpected, as the interchain disulfide likely plays a role in shielding additional trypsin sites. In Neuro-2a cells, βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S) had a perinuclear internalization (Fig. 7C) similar to that of βlac-TeNT(RY) and was segregated from SV2C by Pearson's correlation coefficients (Fig. 7D). We observed that both the LC and HC of βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S) localized to intracellular vesicles. This indicated that the loss of the interchain disulfide did not affect toxin binding, entry, or trafficking. In contrast, βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S) did not cleave CCF2 in the translocation assay, indicating that βlac did not translocate into primary cortical neurons (Fig. 8A and B). As with the Neuro-2a entry, the FLAG and HA epitopes for βlac-TeNT(RY) and βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S) at various time points during entry into cortical neurons are comparable (data not shown), and βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S) associated with neurons comparably to other variants (Fig. 8C). Thus, we concluded that the loss of LC translocation was not due to the separation of the LC from the HC prior to vesicle entry but occurred later in the entry process during LC translocation. Additionally, we measured βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S) in vitro βlac activity to confirm the reporter was active (Fig. 8D). These data indicate that the interchain disulfide bond is required for initiation of LC translocation; alternatively, it may show that the cargo did not fully translocate into the cytosol.

FIG 8.

βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S, C467S) does not translocate βlac into cytosol. (A) Neurons were incubated with 40 nM single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY), βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S), and βlac-HCR/T for 1 h at 37°C before loading with CCF2-AM for 30 min at 25°C. The scale bar is 10 μm. (B) Quantification of reporter translocation in random fields by cleaved CCF2 (emission, 447 nm) normalized to net FLAG signal, with SEM. Student's t test indicates P < 0.0001 (***) between different reporters at 40 nM. (C) Quantification of cell-associated reporters shown by taking the ratio of net FLAG to NeuN (nuclear cell marker). (D) In vitro βlac activity was measured over time, using 10 nM βlac reporter proteins and 2 μM fluorocillin green, a colorless substrate that emits fluorescence when cleaved, with SEM shown.

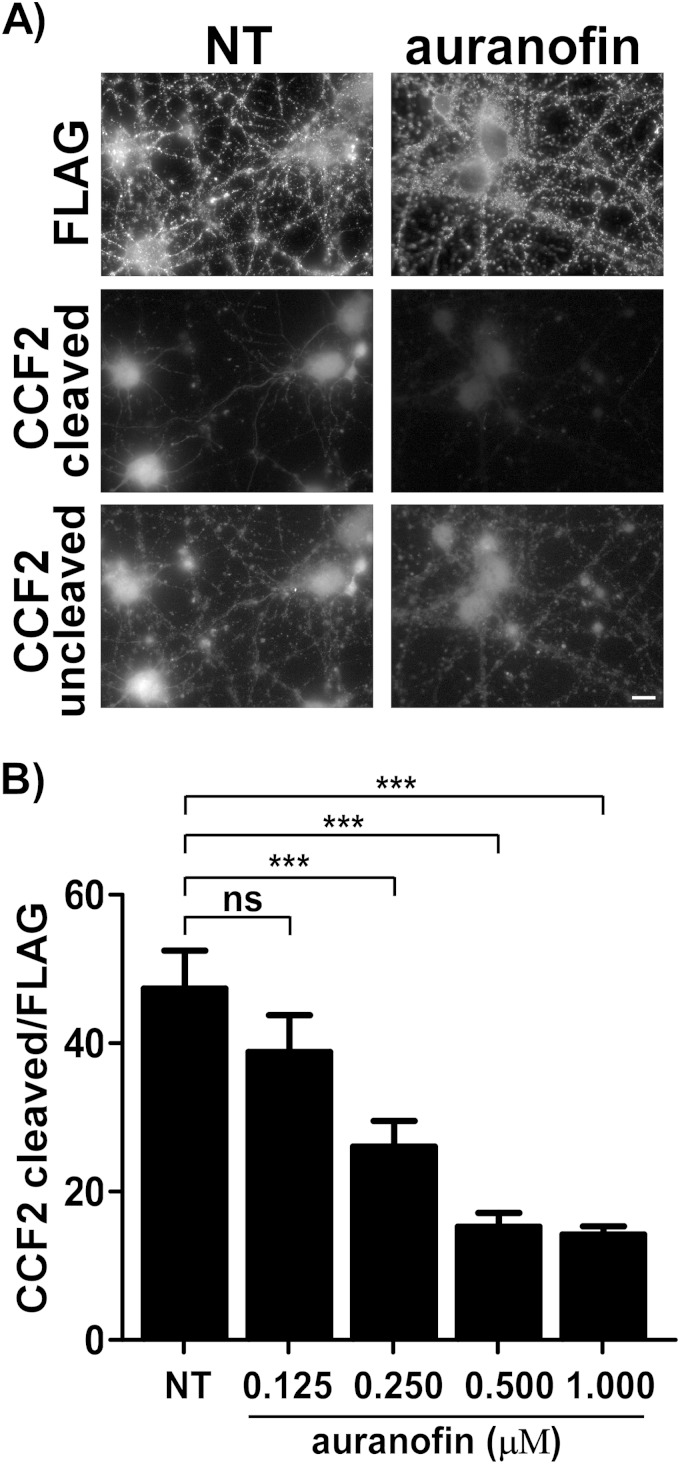

Auranofin inhibits βlac translocation by βlac-TeNT(RY).

The thioredoxin-thioredoxin reductase (Trx-TrxR) system has been demonstrated to reduce the interchain disulfide of TeNT in vitro (50). Two common isoforms of the thioredoxin system that are present in mammalian cells, including rat cortex, are cytosolic Trx-TrxR-1 and mitochondrion-associated Trx-TrxR-2 (51). These enzymes associate with the cytosolic face of purified synaptic vesicles in cerebellar granular neurons (52). Auranofin inhibits TrxR-1 more efficiently than TrxR-2 (53). Auranofin also inhibits TeNT and BoNT/A, BoNT/B, BoNT/C, BoNT/D, and BoNT/E intoxication of cerebellar granular neurons, presumably by inhibiting reduction of the interchain disulfide (52–54). Thus, the ability of auranofin to inhibit βlac translocation by βlac-TeNT(RY) was tested. Preincubation with increasing concentrations of auranofin showed a dose-dependent inhibition of βlac translocation by βlac-TeNT(RY) (Fig. 9A and B).

FIG 9.

Auranofin inhibits βlac translocation. (A) Neurons were preincubated with 1 μM auranofin for 1 h at 37°C or DMSO carrier pretreatment only (NT), and medium was replaced with 40 nM single-chain βlac-TeNT(RY) at the indicated concentration (1 μM) for 1 h at 37°C before loading with CCF2-AM for 30 min at 25°C. Cells were washed, fixed, and probed for FLAG. The scale bar is 10 μm. (B) Quantification for 40 nM βlac-TeNT(RY) translocation preincubated with auranofin (0.125, 0.250, 0.500, or 1 μM) as described for panel A. The results for cleaved CCF2 (Em, 447 nm) were normalized to net FLAG signal, with SEM shown. Student's t test indicates P < 0.0001 (***) between the indicated untreated and treated conditions.

DISCUSSION

In this study, βlac-TeNT(RY) was engineered to measure βlac translocation to the cytosol of intact primary cortical neurons, using CCF2 cleavage as a readout. βlac-TeNT(RY) retained an intact interchain disulfide, ganglioside-dependent binding, and intracellular trafficking in Neuro-2a cells as observed for TeNT(RY). βlac-TeNT(RY), like TeNT, was sensitive to bafilomycin A1 and requires an intact interchain disulfide to translocate βlac into the cytosol, as βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C467S) could bind, enter, and localize but did not translocate. Inhibition of thioredoxin reductase also reduced the ability of βlac-TeNT(RY) to cleave CCF2, indicating this redox system was involved in βlac translocation and that reduction of the interchain disulfide precedes LC translocation.

Prerequisite conditions for LC translocation by CNTs have been examined by several approaches. In vitro approaches have assessed CNT interaction with liposomes under defined conditions by photoactivable lipid probes or release of cations to measure penetration (25, 38, 55). These assays assessed individual toxin domains, lipid content of vesicles, and pH under controlled conditions. Potential issues include different interactions with the membrane without cellular factors, as observed for diphtheria toxin. Electrophysiology, using Neuro-2a patch clamping, detects conditions conducive for cation-conducting channel formation with physiological cell factors (29), where a higher conductance state or cation flow is correlated with productive LC translocation (31). Neuronal cultures provide a convenient model to measure LC translocation through the LC translocation-dependent enzymatic cleavage of SNARE substrates or delivery of LC fusion proteins (21, 39, 56, 57). In this study, we developed the translocation reporter βlac-TeNT(RY), which, unlike previous clostridial neurotoxin reporters (22, 57, 58), does not require cell fractionation to detect translocation. This allows intact cell-based analysis to resolve steps in the translocation process, identify steps in channel formation, pH sensing, and delivery, and potentially identify inhibitors of translocation in neurons.

Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) or the light chain of BoNT/A (LC/A) fused to the N terminus of BoNT/D and the light chain of BoNT/E (LC/E) fused to the N terminus of TeNT translocate the enzymatically active heterologous proteins into the cytosol of neurons (22, 57). Similarly, peptides and a tandem catalytic domain fused to the N terminus of diphtheria toxin resulted in translocation of these fusions into the cytosol of Vero cells (59, 60). If LC translocation proceeds from the N to C terminus, these data imply the amino acid sequence of N terminus is less important than the secondary structure for LC translocation initiation (29). Alternatively, the C-terminal portion of the LC may enter the cytosol first, facilitating delivery of heterologous reporters. The observation that methotrexate stabilization of DHFR-scBoNT/D reduced toxicity in mouse phrenic nerve assays supports a role for the C terminus of the LC to initiate translocation, where the reporter DHFR-scBoNT/D has been trapped in a translocation intermediate. In support of a role for the C terminus in translocation, diphtheria toxin catalytic domain with an engineered disulfide bridge near the N terminus was partially protected from pronase treatment, indicating that those regions were membrane associated but not yet translocated (61). Our observation of inhibition of βlac translocation upon treatment with the thioredoxin reductase inhibitor auranofin implies that the interchain disulfide is recognized by the cytosolic reductase and that reduction of the interchain disulfide precedes βlac entry into the host cytosol. If translocation of TeNT-LC proceeds N terminus to C terminus, we predict that auranofin would not inhibit βlac cleavage of CCF2.

The importance of the interchain disulfide for AB toxins is demonstrated by attenuation of neurotoxicity and channel formation for prereduced CNTs (27, 28). βlac-TeNT(RY-C439S,C476S) possessed in vitro βlac activity and entered cells, as did TeNT(RY). The absence of cleaved CCF2 indicates that the disulfide is required for initiation of LC translocation, with either a direct or structural role. After reduction, TeNT and diphtheria toxin dichains remain associated by noncovalent forces; however, in a study that measured intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of oxidized or reduced TeNT under acidic conditions, reduced TeNT had lower fluorescence, suggesting that the disulfide is required to trigger changes for translocation (62, 63). Electrophysiology experiments implicated that the interchain disulfide bond of BoNT/A is reduced in the trans chamber to facilitate LC translocation (27). Together, these results imply that an intact interchain disulfide is required for initiation of productive translocation, must be retained through passage into the cell cytosol, and then must be reduced as a prerequisite for LC delivery into the cytosol.

A role for the thioredoxin-thioredoxin reductase system has been demonstrated for TeNT in vitro and in vivo as inhibition of the redox system reduces VAMP2 cleavage in neuronal culture (54). Similarly, for diphtheria toxin, cytosolic TrxR-1 has been purified from cytosolic translocation factor (CTF) complexes and is necessary but not sufficient for in vitro translocation assays, suggesting a common mechanism among toxins (64). TrxR-1 has been postulated to act as a chaperonin to refold the LC prior to reduction; however, inhibition of βlac translocation upon treatment with auranofin implies reduction is prerequisite to βlac translocation into the cytosol (54). A requirement for reduction of the interchain disulfide prior to translocation of the LC also would explain why inhibitors of the Trx-TrxR system are not neuroprotective once the LC is in the cytosol (52). Trypsin-nicked diphtheria toxins like TeNT contain a dichain connected by an interchain disulfide bridge. In the presence of N-ethyl maleimide, which blocks interchain reduction of diphtheria, a 3-kDa N-terminal portion of the translocation domain and the catalytic domain were protected from extracellular pronase treatment; upon further treatment with the reductant dithiothreitol (DTT), the catalytic domain is released, suggesting that the interchain disulfide is cytosolic (65, 66). We propose that AB toxins utilize the N terminus of the translocation domain as an anchor to insert and facilitate the translocation of the A catalytic domain (LC) into the cytosol to a sufficient length to initiate refolding within the cytosol alone or facilitated by a chaperone (64, 67). A similar mechanism has been described for the translocation of mitochondrial proteins where an amphipathic helix anchors into the channel that facilitates translocation of posttranslationally synthesized proteins (66, 68).

The data presented in the current study indicate that βlac-TeNT(RY) can be utilized as a model to study LC translocation. Using this reporter and a variant lacking an interchain disulfide bridge, we found that the interchain disulfide is not necessary for binding, entering, or trafficking; however, the interchain disulfide is required to initiate translocation, and directed reduction is required to complete translocation. Together with the observed inhibition of βlac translocation, the reduction of a cytosolic, intact interchain disulfide may be prerequisite for LC translocation through the protein pore. Translocation of the βlac through the protein channel suggests that the N terminus does not play a rate-limiting role in LC translocation. Further assessment may resolve other steps in LC translocation and identify inhibitors of LC translocation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

These studies were supported by a grant to J.T.B. from the NIH (AI-030162).

REFERENCES

- 1.Lacy DB, Stevens RC. 1999. Sequence homology and structural analysis of the clostridial neurotoxins. J Mol Biol 291:1091–1104. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binz T, Rummel A. 2009. Cell entry strategy of clostridial neurotoxins. J Neurochem 109:1584–1595. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montecucco C, Schiavo G. 1994. Mechanism of action of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins. Mol Microbiol 13:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill DM. 1982. Bacterial toxins: a table of lethal amounts. Microbiol Rev 46:86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook TM, Protheroe RT, Handel JM. 2001. Tetanus: a review of the literature. Br J Anaesth 87:477–487. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dressler D, Bigalke H. 2005. Botulinum toxin type B de novo therapy of cervical dystonia: frequency of antibody induced therapy failure. J Neurol 252:904–907. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0774-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodick DW. 2003. Botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of migraine and other primary headache disorders: from bench to bedside. Headache 43(Suppl 1):S25–S33. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.43.7s.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen S. 2012. Clinical uses of botulinum neurotoxins: current indications, limitations and future developments. Toxins 4:913–939. doi: 10.3390/toxins4100913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C, Fu Z, Kim JJ, Barbieri JT, Baldwin MR. 2009. Gangliosides as high affinity receptors for tetanus neurotoxin. J Biol Chem 284:26569–26577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.027391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karalewitz AP, Fu Z, Baldwin MR, Kim JJ, Barbieri JT. 2012. Botulinum neurotoxin serotype C associates with dual ganglioside receptors to facilitate cell entry. J Biol Chem 287:40806–40816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.404244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rummel A, Karnath T, Henke T, Bigalke H, Binz T. 2004. Synaptotagmins I and II act as nerve cell receptors for botulinum neurotoxin G. J Biol Chem 279:30865–30870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rummel A, Hafner K, Mahrhold S, Darashchonak N, Holt M, Jahn R, Beermann S, Karnath T, Bigalke H, Binz T. 2009. Botulinum neurotoxins C, E and F bind gangliosides via a conserved binding site prior to stimulation-dependent uptake with botulinum neurotoxin F utilising the three isoforms of SV2 as second receptor. J Neurochem 110:1942–1954. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong M, Richards DA, Goodnough MC, Tepp WH, Johnson EA, Chapman ER. 2003. Synaptotagmins I and II mediate entry of botulinum neurotoxin B into cells. J Cell Biol 162:1293–1303. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu Z, Chen C, Barbieri JT, Kim JJ, Baldwin MR. 2009. Glycosylated SV2 and gangliosides as dual receptors for botulinum neurotoxin serotype F. Biochemistry 48:5631–5641. doi: 10.1021/bi9002138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong M, Yeh F, Tepp WH, Dean C, Johnson EA, Janz R, Chapman ER. 2006. SV2 is the protein receptor for botulinum neurotoxin A. Science 312:592–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1123654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgen ASV, Dickens F, Zatman LJ. 1949. The action of botulinum toxin on the neuro-muscular junction. J Physiol 109:10–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verderio C, Rossetto O, Grumelli C, Frassoni C, Montecucco C, Matteoli M. 2006. Entering neurons: botulinum toxins and synaptic vesicle recycling. EMBO Rep 7:995–999. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deinhardt K, Berninghausen O, Willison HJ, Hopkins CR, Schiavo G. 2006. Tetanus toxin is internalized by a sequential clathrin-dependent mechanism initiated within lipid microdomains and independent of epsin1. J Cell Biol 174:459–471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deinhardt K, Salinas S, Verastegui C, Watson R, Worth D, Hanrahan S, Bucci C, Schiavo G. 2006. Rab5 and Rab7 control endocytic sorting along the axonal retrograde transport pathway. Neuron 52:293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lalli G, Schiavo G. 2002. Analysis of retrograde transport in motor neurons reveals common endocytic carriers for tetanus toxin and neurotrophin receptor p75NTR. J Cell Biol 156:233–239. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williamson LC, Fitzgerald SC, Neale EA. 1992. Differential effects of tetanus toxin on inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitter release from mammalian spinal cord cells in culture. J Neurochem 59:2148–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Zurawski TH, Meng J, Lawrence GW, Aoki KR, Wheeler L, Dolly JO. 2012. Novel chimeras of botulinum and tetanus neurotoxins yield insights into their distinct sites of neuroparalysis. FASEB J 26:5035–5048. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-210112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blum FC, Tepp WH, Johnson EA, Barbieri JT. 2014. Multiple domains of tetanus toxin direct entry into primary neurons. Traffic 15:1057–1065. doi: 10.1111/tra.12197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandvig K, Olsnes S. 1980. Diphtheria toxin entry into cells is facilitated by low pH. J Cell Biol 87:828–832. doi: 10.1083/jcb.87.3.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boquet P, Duflot E. 1982. Tetanus toxin fragment forms channels in lipid vesicles at low pH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 79:7614–7618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacy DB, Tepp W, Cohen AC, DasGupta BR, Stevens RC. 1998. Crystal structure of botulinum neurotoxin type A and implications for toxicity. Nat Struct Biol 5:898–902. doi: 10.1038/2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer A, Montal M. 2007. Crucial role of the disulfide bridge between botulinum neurotoxin light and heavy chains in protease translocation across membranes. J Biol Chem 282:29604–29611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiavo G, Papini E, Genna G, Montecucco C. 1990. An intact interchain disulfide bond is required for the neurotoxicity of tetanus toxin. Infect Immun 58:4136–4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer A, Montal M. 2007. Single molecule detection of intermediates during botulinum neurotoxin translocation across membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:10447–10452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700046104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cai S, Kukreja R, Shoesmith S, Chang TW, Singh BR. 2006. Botulinum neurotoxin light chain refolds at endosomal pH for its translocation. Protein J 25:455–462. doi: 10.1007/s10930-006-9028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koriazova LK, Montal M. 2003. Translocation of botulinum neurotoxin light chain protease through the heavy chain channel. Nat Struct Biol 10:13–18. doi: 10.1038/nsb879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutton RB, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger AT. 1998. Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4[thinsp]A resolution. Nature 395:347–353. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blum FC, Przedpelski A, Tepp WH, Johnson EA, Barbieri JT. 2014. Entry of a recombinant, full-length, atoxic tetanus neurotoxin into Neuro-2a cells. Infect Immun 82:873–881. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01539-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C, Baldwin MR, Barbieri JT. 2008. Molecular basis for tetanus toxin coreceptor interactions. Biochemistry 47:7179–7186. doi: 10.1021/bi800640y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baldwin MR, Barbieri JT. 2007. Association of botulinum neurotoxin serotypes a and B with synaptic vesicle protein complexes. Biochemistry 46:3200–3210. doi: 10.1021/bi602396x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blum FC, Chen C, Kroken AR, Barbieri JT. 2012. Tetanus toxin and botulinum toxin a utilize unique mechanisms to enter neurons of the central nervous system. Infect Immun 80:1662–1669. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00057-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boquet P, Duflot E, Hauttecoeur B. 1984. Low pH induces a hydrophobic domain in the tetanus toxin molecule. Eur J Biochem 144:339–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burns JR, Baldwin MR. 2014. Tetanus neurotoxin utilizes two sequential membrane interactions for channel formation. J Biol Chem 289:22450–22458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.559302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller JE, Cai F, Neale EA. 2004. Uptake of botulinum neurotoxin into cultured neurons. Biochemistry 43:526–532. doi: 10.1021/bi0356698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu H, Leppla SH. 2009. Anthrax toxin uptake by primary immune cells as determined with a lethal factor-β-lactamase fusion protein. PLoS One 4:e7946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marketon MM, DePaolo RW, DeBord KL, Jabri B, Schneewind O. 2005. Plague bacteria target immune cells during infection. Science 309:1739–1741. doi: 10.1126/science.1114580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dolores JS, Agarwal S, Egerer M, Satchell KJ. 2014. Vibrio cholerae MARTX toxin heterologous translocation of beta-lactamase and roles of individual effector domains on cytoskeleton dynamics. Mol Microbiol 95:590–604. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jobling MG, Holmes RK. 1992. Fusion proteins containing the A2 domain of cholera toxin assemble with B polypeptides of cholera toxin to form immunoreactive and functional holotoxin-like chimeras. Infect Immun 60:4915–4924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zlokarnik G, Negulescu PA, Knapp TE, Mere L, Burres N, Feng L, Whitney M, Roemer K, Tsien RY. 1998. Quantitation of transcription and clonal selection of single living cells with beta-lactamase as reporter. Science 279:84–88. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montecucco C, Schiavo G, Gao Z, Bauerlein E, Boquet P, DasGupta BR. 1988. Interaction of botulinum and tetanus toxins with the lipid bilayer surface. Biochem J 251:379–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williamson LC, Bateman KE, Clifford JC, Neale EA. 1999. Neuronal sensitivity to tetanus toxin requires gangliosides. J Biol Chem 274:25173–25180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.25173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calappi E, Masserini M, Schiavo G, Montecucco C, Tettamanti G. 1992. Lipid interaction of tetanus neurotoxin. A calorimetric and fluorescence spectroscopy study. FEBS Lett 309:107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helting TB, Zwisler O, Wiegandt H. 1977. Structure of tetanus toxin. II. Toxin binding to ganglioside. J Biol Chem 252:194–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qazi O, Bolgiano B, Crane D, Svergun DI, Konarev PV, Yao ZP, Robinson CV, Brown KA, Fairweather N. 2007. The HC fragment of tetanus toxin forms stable, concentration-dependent dimers via an intermolecular disulphide bond. J Mol Biol 365:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kistner A, Habermann E. 1992. Reductive cleavage of tetanus toxin and botulinum neurotoxin A by the thioredoxin system from brain. Evidence for two redox isomers of tetanus toxin. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 345:227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arner ES, Holmgren A. 2000. Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Eur J Biochem 267:6102–6109. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pirazzini M, Azarnia Tehran D, Zanetti G, Megighian A, Scorzeto M, Fillo S, Shone CC, Binz T, Rossetto O, Lista F, Montecucco C. 2014. Thioredoxin and its reductase are present on synaptic vesicles, and their inhibition prevents the paralysis induced by botulinum neurotoxins. Cell Rep 8:1870–1878. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rackham O, Shearwood AM, Thyer R, McNamara E, Davies SM, Callus BA, Miranda-Vizuete A, Berners-Price SJ, Cheng Q, Arner ES, Filipovska A. 2011. Substrate and inhibitor specificities differ between human cytosolic and mitochondrial thioredoxin reductases: implications for development of specific inhibitors. Free Radic Biol Med 50:689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pirazzini M, Bordin F, Rossetto O, Shone CC, Binz T, Montecucco C. 2013. The thioredoxin reductase-thioredoxin system is involved in the entry of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins in the cytosol of nerve terminals. FEBS Lett 587:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Montecucco C, Schiavo G, Brunner J, Duflot E, Boquet P, Roa M. 1986. Tetanus toxin is labeled with photoactivatable phospholipids at low pH. Biochemistry 25:919–924. doi: 10.1021/bi00352a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Habig WH, Bigalke H, Bergey GK, Neale EA, Hardegree MC, Nelson PG. 1986. Tetanus toxin in dissociated spinal cord cultures: long-term characterization of form and action. J Neurochem 47:930–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bade S, Rummel A, Reisinger C, Karnath T, Ahnert-Hilger G, Bigalke H, Binz T. 2004. Botulinum neurotoxin type D enables cytosolic delivery of enzymatically active cargo proteins to neurones via unfolded translocation intermediates. J Neurochem 91:1461–1472. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang J, Meng J, Lawrence GW, Zurawski TH, Sasse A, Bodeker MO, Gilmore MA, Fernandez-Salas E, Francis J, Steward LE, Aoki KR, Dolly JO. 2008. Novel chimeras of botulinum neurotoxins A and E unveil contributions from the binding, translocation, and protease domains to their functional characteristics. J Biol Chem 283:16993–17002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stenmark H, Moskaug JO, Madshus IH, Sandvig K, Olsnes S. 1991. Peptides fused to the amino-terminal end of diphtheria toxin are translocated to the cytosol. J Cell Biol 113:1025–1032. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Madshus IH, Olsnes S, Stenmark H. 1992. Membrane translocation of diphtheria toxin carrying passenger protein domains. Infect Immun 60:3296–3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Falnes PO, Olsnes S. 1995. Cell-mediated reduction and incomplete membrane translocation of diphtheria toxin mutants with internal disulfides in the A fragment. J Biol Chem 270:20787–20793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li L, Singh BR. 2000. Spectroscopic analysis of pH-induced changes in the molecular features of type A botulinum neurotoxin light chain. Biochemistry 39:6466–6474. doi: 10.1021/bi992729u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kistner A, Sanders D, Habermann E. 1993. Disulfide formation in reduced tetanus toxin by thioredoxin: the pharmacological role of interchain covalent and noncovalent bonds. Toxicon 31:1423–1434. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(93)90208-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ratts R, Zeng H, Berg EA, Blue C, McComb ME, Costello CE, vander Spek JC, Murphy JR. 2003. The cytosolic entry of diphtheria toxin catalytic domain requires a host cell cytosolic translocation factor complex. J Cell Biol 160:1139–1150. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Madshus IH, Wiedlocha A, Sandvig K. 1994. Intermediates in translocation of diphtheria toxin across the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 269:4648–4652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Madshus IH. 1994. The N-terminal alpha-helix of fragment B of diphtheria toxin promotes translocation of fragment A into the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. J Biol Chem 269:17723–17729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Slater LH, Hett EC, Clatworthy AE, Mark KG, Hung DT. 2013. CCT chaperonin complex is required for efficient delivery of anthrax toxin into the cytosol of host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:9932–9937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302257110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vogtle FN, Wortelkamp S, Zahedi RP, Becker D, Leidhold C, Gevaert K, Kellermann J, Voos W, Sickmann A, Pfanner N, Meisinger C. 2009. Global analysis of the mitochondrial N-proteome identifies a processing peptidase critical for protein stability. Cell 139:428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]