Abstract

Swine influenza virus (SIV) and Streptococcus suis are common pathogens of the respiratory tract in pigs, with both being associated with pneumonia. The interactions of both pathogens and their contribution to copathogenesis are only poorly understood. In the present study, we established a porcine precision-cut lung slice (PCLS) coinfection model and analyzed the effects of a primary SIV infection on secondary infection by S. suis at different time points. We found that SIV promoted adherence, colonization, and invasion of S. suis in a two-step process. First, in the initial stages, these effects were dependent on bacterial encapsulation, as shown by selective adherence of encapsulated, but not unencapsulated, S. suis to SIV-infected cells. Second, at a later stage of infection, SIV promoted S. suis adherence and invasion of deeper tissues by damaging ciliated epithelial cells. This effect was seen with a highly virulent SIV subtype H3N2 strain but not with a low-virulence subtype H1N1 strain, and it was independent of the bacterial capsule, since an unencapsulated S. suis mutant behaved in a way similar to that of the encapsulated wild-type strain. In conclusion, the PCLS coinfection model established here revealed novel insights into the dynamic interactions between SIV and S. suis during infection of the respiratory tract. It showed that at least two different mechanisms contribute to the beneficial effects of SIV for S. suis, including capsule-mediated bacterial attachment to SIV-infected cells and capsule-independent effects involving virus-mediated damage of ciliated epithelial cells.

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory diseases in swine are responsible for high economic losses in the pig industry worldwide. The upper respiratory tract is a reservoir for a heterogeneous community of (potentially) pathogenic microorganisms and commensals (1). Pneumonia often represents a multifactorial disease complex caused by mixed infections with different pathogens, including viruses and bacteria. Furthermore, unfavorable environmental conditions facilitate the development of the disease (2). Thus, it is termed porcine respiratory disease complex (PRDC) (1). Often primary viral agents, such as porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, porcine circovirus type 2, and swine influenza virus (SIV), lead to damage of the mucociliary barrier and a decreased immune response, predisposing pigs to secondary infections and pneumonia by opportunistic bacterial pathogens, such as Pasteurella multocida, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, and Streptococcus suis (3). However, very little is known about interactions between viral and bacterial pathogens and their role in the copathogenesis of such complex diseases.

SIV is an infectious agent causing respiratory disease in pig herds, and it is associated with morbidity of up to 100%. Acute symptoms are high fever, depression, tachypnea, abdominal breathing, and, infrequently, coughing (4). SIV subtypes H1N1, H1N2, and H3N2 are pervasive and cocirculating in the swine population worldwide. Subtype H1N1 viruses prevalent in Europe are of avian origin and presumably were introduced into the swine population in 1979. While the early H1N1 isolates were pathogenic, the virulence decreased in the following years. Subtype H1N1 viruses isolated in the last decade hardly induce signs of disease in pig infection experiments and in a porcine precision-cut lung slice (PCLS) model. In contrast, subtype H3N2 and H1N2 viruses are virulent. These viruses have retained the internal proteins of the H1N1 virus but acquired the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase from human H3N2 viruses (5). The HA proteins of swine influenza viruses preferentially recognize alpha-2,6-linked sialic acid. Binding to this receptor determinant is used to initiate infection of host cells.

S. suis is one of the most important swine pathogens, causing invasive diseases associated with meningitis, arthritis, septicemia, and bronchopneumonia. Furthermore, in recent years, S. suis has been considered an important human pathogen, leading to bacterial meningitis and the life-threatening streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome in humans (6, 7). S. suis is a very diverse organism consisting of different capsular serotypes, of which serotype 2 is most frequently isolated worldwide from diseased pigs and humans (6, 8, 9). The sialic acid-rich polysaccharide capsule of serotype 2 strains is an essential virulence factor (10, 11). It protects the bacterium against killing by professional phagocytes. Furthermore, the capsule interferes with the ability of S. suis to adhere to and invade host cells, since unencapsulated mutant strains showed a much higher adherence (and invasion) capacity when analyzed with different epithelial cell lines (12, 13). Many virulent S. suis strains express a cholesterol-dependent pore-forming cytolysin, suilysin (14, 15), which is the main bacterial factor causing host cell damage (13, 16, 17). It has been suggested that suilysin plays a role in the invasion of S. suis (13, 16) as well as in immunomodulation and evasion of opsonophagocytosis (18–20), but its precise role in pathogenesis remains to be resolved.

Most studies on coinfection, including those on SIV and S. suis coinfection, have been performed with epithelial cell lines, which allow only limited conclusions on the biological relevance of respective results. In contrast, cultures of differentiated respiratory epithelial cells, such as PCLS, are much closer to the in vivo situation. PCLS consist of primary, well-differentiated, respiratory multicellular tissues containing all relevant cell types of the lung, e.g., ciliated cells, mucus-producing cells, and pneumocytes, maintained in the natural setting. Moreover, an important advantage of this ex vivo system compared to (primary and immortalized) host cells cultured as monolayers is the preserved and sustained ciliary activity of epithelial cells lining the bronchiolar surface (4).

The objective of the present study was to establish a novel PCLS model for analyses of the coinfection of differentiated airway epithelial cells by S. suis and SIV. Using this model, we were able to characterize SIV-promoted adherence, colonization, and invasion of S. suis at different time points and could show that these effects are based on at least two mechanisms, one which is dependent on the bacterial capsule and one which is mediated by virus-induced impairment of the ciliary epithelial cell barrier.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

If not stated otherwise, all materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Ethics statement.

Pigs used for these experiments were kept in the Clinic for Swine and Small Ruminants and Forensic Medicine for demonstration and student veterinary training (approval number 33.9-42502-05-09A627). All studies were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations of the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes (European Treaty Series, no. 123 [http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/123.htm] and 170 [http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/170.htm]). The protocol was approved by the national permitting authorities (animal welfare officer of the University of Veterinary Medicine, Lower Saxony State Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety). All measures were in accordance with the requirements of the national animal welfare law. Killing and tissue sampling were performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Strains and growth conditions.

The virulent Streptococcus suis serotype 2 wild-type (wt) strain 10 and its isogenic unencapsulated mutant strain 10cpsΔEF (generated by insertional mutagenesis) were kindly provided by H. Smith, Lelystad, Netherlands (10). The corresponding suilysin-deficient mutant of wt strain 10, 10Δsly, was constructed as described in a previous study by insertion of an erythromycin resistance cassette into the suilysin gene (21). Streptococci were grown in Todd Hewitt broth medium (THB; Becton Dickinson Diagnostics) or on Columbia agar supplemented with 7% sheep blood (Oxoid) overnight under aerobic conditions at 37°C. For infection experiments, cryo-conserved bacterial stocks were grown in THB medium overnight, adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.02 in prewarmed media the next day, and further grown to late exponential growth phase (OD600 of 0.8). Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (6,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C), washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in THB medium containing 15% (vol/vol) glycerol. Aliquots were immediately shock frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Numbers of viable bacteria were determined by serial plating on Columbia agar plates supplemented with 7% sheep blood and counting CFU the next day.

Swine influenza viruses (SIV) of the H1N1 subtype (A/sw/Bad Griesbach/IDT5604/2006; H1N1) and the H3N2 subtype (A/sw/Herford/IDT5932/2007; H3N2) were obtained from IDT Biologika GmbH, Dessau-Rosslau, Germany. The strains originally had been isolated from pigs with respiratory disease during surveillance programs initiated by Ralf Dürrwald, Dessau-Rosslau (IDT Biologika GmbH). Virus stocks were propagated by infection of MDCK II cells at a low multiplicity of infection and incubation in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM; Life Technologies) containing 1 μg/ml acetylated trypsin. Supernatants were clarified by low-speed centrifugation (200 × g, 10 min, room temperature) and stored at −80°C.

MDKC II cells, a subline of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (22), were maintained in EMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 5 mM glutamine (Life Technologies). The cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C and passaged every 2 to 3 days.

PCLS.

Precision-cut lung slices were prepared from lungs of 3-month-old healthy crossbred pigs, which were obtained from conventional farms and housed in the Clinics for Swine and Small Ruminants and Forensic Medicine at the University of Veterinary Medicine, Hannover, Germany. The animals had a good health status and no clinical symptoms. The cranial, middle, and intermediate lobes of the fresh lungs were carefully removed and filled with 37°C low-melting-point agarose (Gerbu) as previously described (4, 23, 24). After the agarose became solidified on ice, the tissue was stamped out as cylindrical portions (8-mm tissue coring tool), and approximately 250-μm-thick slices were prepared by using a Krumdieck tissue slicer (model MD4000-01; TSE Systems) with a cycle speed of 60 slices/min. PCLS were incubated in 1 ml of RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies) containing antibiotics and antimycotics (1 mg/liter clotrimazole, 10 mg/liter enrofloxacin, 50 mg/liter kanamycin, 100,000 U/liter penicillin, 100 mg/liter streptomycin/ml, 50 mg/liter gentamicin, 2.5 mg/liter amphotericin B) in a 24-well plate at 37°C and 5% CO2. In order to remove the agarose, culture medium was changed every hour during the first 4 h and once per day for further culture. These extensive washings also may have removed preexisting antibodies, because no neutralizing activity was ever observed. Viability was analyzed by observing the ciliary activity under a Nikon TMS light microscope equipped with 4×, 0.12-numerical aperture (NA) and 10×, 0.25-NA objectives (Leitz, Wetzlar).

Infection of PCLS with SIV and S. suis and determination of bacterial growth.

For infection experiments, three slices were used for each treatment and all experiments were repeated three times. Slices were maintained without antibiotics and antimycotics 1 day before infection and washed three times with PBS before inoculation. For bacterial monoinfection, PCLS were inoculated with approximately 107 CFU of S. suis strain 10, 10cpsΔEF, or 10Δsly in 500 μl RPMI/well for 4 h. Slices were washed three times, and fresh media was added to remove nonadhered bacteria. Infected slices then were incubated for an additional 20 h in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C.

For coinfection experiments, PCLS were preinfected with SIV subtype H1N1 or H3N2 in a volume of 300 μl RPMI/well at 105 TCID50/ml (50% tissue culture infectious dose/milliliter) for 1 h, followed by a washing step with PBS and a coinfection with S. suis strain 10 or 10cpsΔEF, as described above for bacterial monoinfection. Slices monoinfected with bacteria or virus served as controls. Infected PCLS were incubated until 72 h postinfection (hpi) with bacteria in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Supernatants of monoinfected, coinfected, and uninfected control slices were collected at different time points. The bacterial replication rates and growth kinetics were determined by replicate plating of supernatants on Columbia agar supplemented with 7% sheep blood 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hpi.

For virus infectivity analysis, virus titers were determined at time points −1, 4, 8, 24, 48, and 72 hpi by endpoint dilution titration on MDCK cells in 96-well plates as described previously (4). Briefly, for each sample, 10-fold serial dilutions were prepared, and of each dilution, 100 μl per well was added to confluent MDCK cells in a 96-well plate; every sample had 6 replicates. Plates were incubated for 72 h, and the wells were visually analyzed for virus-induced cytopathic effects.

Ciliary activity assay.

PCLS were analyzed under a light microscope to estimate the ciliary activity as described previously (4). Each bronchus was divided virtually into 10 segments, each of which was monitored for the presence or absence of ciliary activity. The ciliostatic effect was determined by estimating the percentage of the luminal surface showing ciliary activity. Slices that showed 100% ciliary activity were selected for further infection experiments. Ciliary activity was monitored 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hpi for bacterial monoinfection of PCLS and extended for an additional 48 and 72 hpi for viral monoinfection and coinfection experiments.

Cryosections.

For immunofluorescent analysis of PCLS, slices were mounted on small filter paper with tissue-freezing medium (Jung), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80°C prior to cutting. Slices were cut at 10-μm thickness by a cryostat (Reichert-Jung). The sections were dried overnight at room temperature and kept frozen at −20°C until staining.

Immunofluorescence analysis and confocal microscopy of cryosections and quantification.

Slices were fixed with 3% formaldehyde for 20 min, followed by a 5-min incubation with 0.1 M glycine and three washing steps with PBS. The sections then were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature, followed by 3 washing steps with PBS. All antibodies were diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS and incubated with the sections for 1 h at room temperature in a humid incubation chamber. For detection of virus particles, monoclonal antibodies against the influenza A virus nucleoprotein (NP; 1:750; AbDSeroTec) were used, followed by incubation with a green fluorescent anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG [H+L] antibody; Life Technologies). For detection of S. suis, a rabbit anti-S. suis antiserum (1:200) (18) was used, followed by a red fluorescent anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 568 anti-rabbit IgG [H+L] antibody; Life Technologies). Ciliated and mucus-producing cells were visualized using antibodies against β-tubulin and mucin, respectively. In brief, PCLS were probed with a Cy3-labeled monoclonal antibody against β-tubulin (1:500) or with a mucin-5 AC antibody (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by a red fluorescent anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 568 anti-mouse IgG [H+L] antibody; Life Technologies). Nuclei were stained by DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Finally, all of the samples were embedded in Mowiol and stored at 4°C until examination under a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S inverse immunofluorescence microscope equipped with 10×, 0.30-NA and 100×, 1.30-NA CFI Plan Fluor objectives (Nikon). Subsequently, the area of the luminal bronchiolar surface positive for green fluorescent bacteria was analyzed by applying the analySIS 3.2 software (Soft Imaging System) to quantify bacterial attachment. Confocal microscopy of PCLS was performed using a TCS SP5 confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a 63×, 1.30-NA glycerin HC PL Apochromat objective (Leica). Image stacks with a z-distance of 0.3 μm per plane were acquired using a 1-Airy-unit pinhole diameter in sequential imaging mode to avoid bleed through. Maximum intensity projections were calculated for display purposes and adjusted for brightness and contrast using ImageJ/Fiji.

Statistical analyses.

If not stated otherwise, experiments were performed at least three times, and results were expressed as means with standard deviations (SD). Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey or Dunnett's multiple-comparison test or Mann-Whitney U test using the GraphPad Prism 5 software. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Encapsulated and nonencapsulated S. suis efficiently adhere to and colonize bronchiolar epithelial cells.

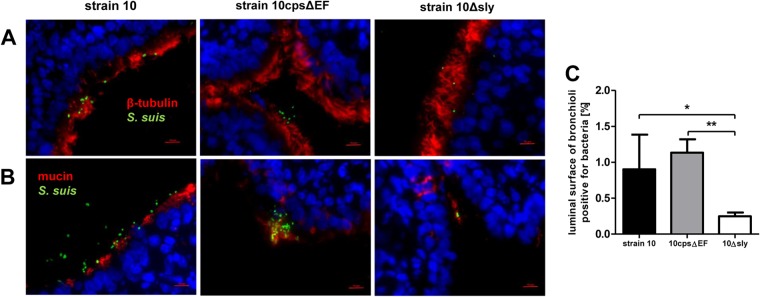

Since precision-cut lung slices (PCLS) have not yet been used as an infection model for S. suis, we first established and characterized monoinfection of PCLS with this pathogen. The ability of S. suis to adhere to and colonize ciliated and mucus-producing cells of porcine bronchioli was determined by immunofluorescence microscopy of PCLS cryosections stained at 24 hpi. For this, PCLS were infected with approximately 107 CFU of S. suis per slice for 4 h to allow bacterial adherence. PCLS then were washed thoroughly to remove nonadherent bacteria and incubated for a further 20 h to determine bacterial colonization. As shown in Fig. 1A and B, the encapsulated virulent serotype 2 wild-type (wt) strain 10 adhered to and colonized the bronchiolar epithelium of PCLS. S. suis was found to adhere to ciliated cells (upper) and to mucus (lower). Bacterial replication during infection was analyzed by determination of CFU from platings of supernatants from infected PCLS. Results revealed proliferation of S. suis during the first 4 h of incubation and, after replacement of the cell-supernatant to remove nonadherent bacteria, until the end of the experiment (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

S. suis adherence to and colonization of porcine PCLS. PCLS were infected with approximately 107 CFU of S. suis strain 10, 10Δsly, or 10cpsΔEF per slide for 4 h, washed thoroughly to remove nonadherent bacteria, and incubated for an additional 20 h. (A and B) Cryosection of PCLS followed by immunostaining was performed 24 h after bacterial infection. Streptococci are labeled in green, and nuclei were stained by DAPI (blue). Bars represent 10 μm. Ciliated cells were stained using anti-β-tubulin antibody (A, red) and mucus-producing cells labeled with anti-Muc5Ac antibody (B, red). (C) Number of bacteria attached to ciliated cells determined by measuring the area of the luminal surface of bronchioli positive for green fluorescent bacteria. Results are expressed as means with SD, and significance, indicated by one (P < 0.05) or two (P < 0.01) asterisks, was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post hoc test.

Since previous in vitro studies using immortalized epithelial cell lines had shown that nonencapsulated S. suis strains adhered (and invaded) more efficiently than encapsulated strains (12, 13, 25), we included the capsule-deficient mutant strain 10cpsΔEF in our studies. In contrast to previous findings with conventional monolayer cell cultures, the adherence levels of the encapsulated wt strain and its unencapsulated mutant were nearly equal (Fig. 1A and B). This was confirmed by quantification of bacterial adherence by measuring the area of the luminal surface of bronchioli positive for green fluorescent bacteria (Fig. 1C). Notably, the pattern of adherence appeared to differ between the wt and the mutant strain. The encapsulated wt strain adhered in a more homogenous pattern, whereas the nonencapsulated mutant strain showed a cluster-like adherence and formation of microcolonies mainly associated with mucus (Fig. 1B).

In addition, we tested a suilysin-deficient strain, 10Δsly, since we had found in previous studies that suilysin contributes to adherence and invasion of S. suis using HEp-2 epithelial cells (13). In good agreement with our previous findings, only very few bacteria of strain 10Δsly adhered to bronchiolar epithelial cells, as shown by visual inspection and quantification of microscopic images (Fig. 1).

In control experiments, we have monitored bacterial replication during infection, confirming that the observed effects were not due to differences in growth properties of the different strains (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material).

SIV promotes adherence and colonization of S. suis in a capsule-dependent manner.

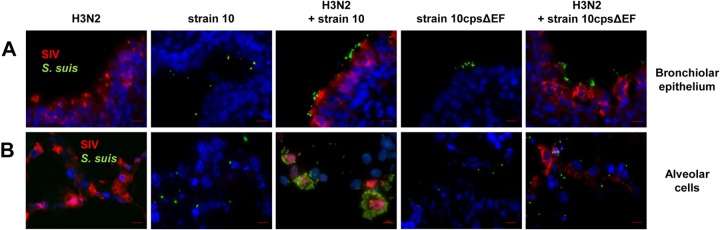

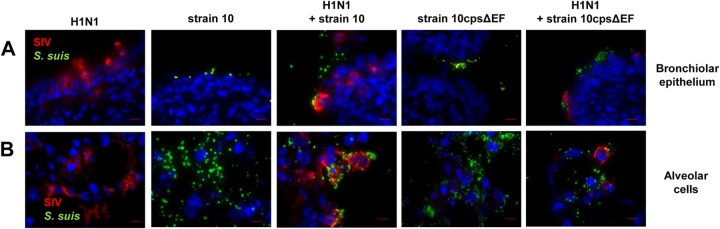

Copathogenesis of influenza virus and bacteria are commonly found in severe pneumonia (26). Recently it has been reported that influenza virus enhances pneumococcal colonization and growth in the upper respiratory tract (27) and that, vice versa, coinfection with Streptococcus pneumoniae complicates influenza-induced pneumonia (28). For S. suis it has been shown that preinfection of a porcine tracheal epithelial cell line with swine influenza virus (SIV) increased bacterial adherence and invasion (25). To investigate possible effects of SIV on S. suis adherence and colonization in a model that is closer to the in vivo situation, we used the PCLS model and preinfected slices with SIV followed by infection with S. suis strain 10 or the unencapsulated mutant strain 10cpsΔEF. SIV infection was done either with a subtype H3N2 strain, previously described as highly virulent in experimentally infected pigs (4), or a less virulent subtype H1N1 strain, both at a concentration of 105 TCID50/ml. After incubation for 1 h and a washing step, S. suis was added and incubation continued until 24, 48, or 72 hpi. Monoinfected slices with virus or bacteria only served as controls. Infected PCLS were coimmunostained for detection of SIV and S. suis. Representative images are shown in Fig. 2 (primary infection with H3N2 for 24 hpi) and Fig. 3 (primary infection with H1N1 for 48 hpi). In monoinfected PCLS, most of the bronchial epithelial cells (Fig. 2A) and many of the alveolar cells (Fig. 2B) were infected by H3N2 at 24 hpi. Compared to subtype H3N2, infection of PCLS by subtype H1N1 virus was detected in about 50% of the respiratory epithelial cells at 48 hpi (Fig. 3A and B), possibly due to the lower replication rate of this strain (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In PCLS monoinfected with bacteria, strain 10 and the mutant 10cpsΔEF both were found attached to the bronchiolar mucosa (Fig. 2A and 3A) as well as to alveolar cells (Fig. 2B and 3B). In PCLS preinfected with either H3N2 (Fig. 2) or H1N1 (Fig. 3), adherence of the encapsulated S. suis strain was clearly enhanced. In both experiments, S. suis selectively attached to SIV-infected cells, as shown by a clear colocalization. This was not seen with the unencapsulated mutant (Fig. 2 and 3). In control experiments, we have monitored bacterial replication until 24 hpi, confirming that the observed effects were not due to differences in growth (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). Quantification of the microscopic images (as described above) confirmed the adherence-promoting effects of SIV (Fig. 4). Preinfection of PCLS with either SIV subtype strain resulted in a significant increase of adherence of the encapsulated S. suis wt strain, but not of its unencapsulated mutant, both at 24 and 48 hpi (Fig. 4A and B). Interestingly, at 72 hpi these effects were different in that preinfection of PCLS with subtype H3N2 resulted in significantly enhanced adherence and colonization of both the wt strain and the unencapsulated S. suis mutant (Fig. 4C). Notably, these late effects were not seen with subtype H1N1-preinfected PCLS (Fig. 4C). The different effects of H3N1 and H1N1 were not due to differences in viral replication, as shown by determination of viral titers in the supernatant of infected PCLS (see Fig. S2). These results suggest that adherence-promoting effects of SIV involved capsule-dependent attachment of S. suis at earlier times after infection and, in addition, mechanisms occurring at later time points of coinfection.

FIG 2.

S. suis adherence to and colonization of H3N2 preinfected porcine PCLS. Porcine PCLS were preinfected with 105 TCID50/ml H3N2 for 1 h, washed, and subsequently infected with S. suis strain 10 or 10cpsΔEF as described for bacterial monoinfection. Slices monoinfected with strain 10, 10cpsΔEF, and H3N2 served as controls. Cryosection of slices followed by immunostaining was performed 24 h after bacterial infection. Streptococci are labeled in green, nucleoproteins of SIV are stained in red, and nuclei are shown in blue (DAPI). (A) Mono- and coinfected cells of the bronchiolar epithelium. Bars represent 10 μm. (B) Mono- and coinfected alveolar cells of PCLS. Bars represent 10 μm.

FIG 3.

S. suis adherence to and colonization of H1N1-preinfected porcine PCLS. Porcine PCLS were preinfected with 105 TCID50/ml H1N1 for 1 h, washed, and subsequently infected with S. suis strain 10 or 10cpsΔEF as described for bacterial monoinfection. Slices monoinfected with strain 10, 10cpsΔEF, and H1N1 served as controls. Cryosection of slices followed by immunostaining was performed 48 h after bacterial infection. Streptococci are labeled in green, nucleoproteins of SIV are stained in red, and nuclei are shown in blue (DAPI). (A) Mono- and coinfected cells of the bronchiolar epithelium. Bars represent 10 μm. (B) Mono- and coinfected alveolar cells of PCLS. Bars represent 10 μm.

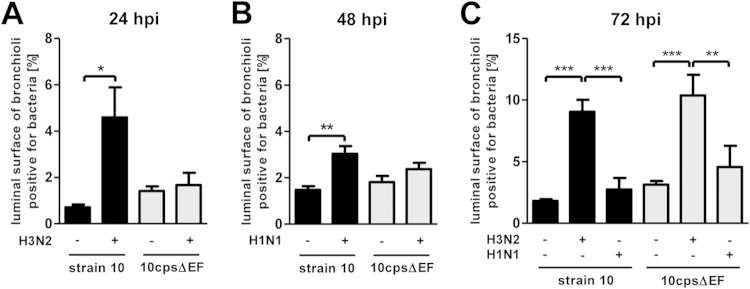

FIG 4.

Quantification of adherent and invasive S. suis in porcine PCLS preinfected with SIV. Porcine PCLS were preinfected with 105 TCID50/ml H3N2 or H1N1 for 1 h, washed, and subsequently infected with S. suis strain 10 or 10cpsΔEF as described for bacterial monoinfection. Slices monoinfected with strains 10 and 10cpsΔEF served as a control. The number of bacteria attached to ciliated cells was determined by measuring the area of the luminal surface of bronchioli positive for green fluorescent bacteria based on immunofluorescent overview images (see Fig. S3 to S5 in the supplemental material). (A) Determination of adherent bacteria 24 h after bacterial infection on H3N2-preinfected PCLS. (B) Determination of adherent bacteria 48 h after bacterial infection on H1N1-preinfected PCLS. (C) Determination of adherent and invasive bacteria 72 h after bacterial infection on H3N2- and H1N1-preinfected PCLS. Results are expressed as means with SD, and significance, indicated by one (P < 0.05), two (P < 0.01), or three (P < 0.001) asterisks, was determined by one-way-ANOVA followed by a Tukey post hoc test.

SIV promotes adherence and invasion of S. suis in a capsule-independent manner by damaging ciliated epithelial cells.

The results described above prompted us to further study capsule-independent SIV-promoted effects at later time points, i.e., 72 hpi. Notably, these effects were seen with the subtype H3N2 strain but not with H1N1 (Fig. 4C). In our previous studies, we had observed that both SIV strains differed in their ciliostatic effect, in that the subtype H3N2 but not the H1N1 strain significantly reduced ciliary activity in a PCLS infection model (4). Thus, we wondered whether virus-induced damage of ciliated epithelial cells contributed to the capsule-independent adherence-promoting effects of SIV.

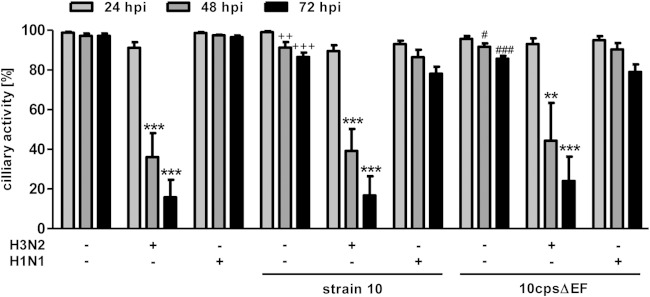

First, we analyzed coinfected PCLS by light microscopy and determined the ciliary activity by estimating the percentage of the luminal surface showing ciliary activity and comparing it to the initial activity at the start of the experiment (i.e., the control [Ctr]). Results were expressed as percent reduction compared to the control and are shown in Fig. 5 (detailed data are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material). Monoinfection with S. suis strain 10 and the mutant 10cpsΔEF had only a minor effect on the ciliary activity during the whole time of infection. Viral monoinfection did not affect ciliary activity of PCLS until 24 hpi, irrespective of the viral strain. In contrast, at 48 and 72 hpi, the proportion of the epithelial cells showing ciliary activity was reduced in H3N2-infected PCLS to 36% (48 hpi) and 17% (72 hpi). In H1N1-infected PCLS, ciliary activity remained almost unaffected. These results are consistent with our earlier studies concerning the different virulence levels of the strains. Secondary infection by S. suis did not affect the low ciliostatic effect of the H1N1 virus or the high ciliostatic effect of the H3N2 virus. From these results, we conclude that at 72 hpi, SIV subtype H3N2 significantly reduced ciliary activity, thereby promoting S. suis adherence and invasion into deeper tissues independent of bacterial encapsulation.

FIG 5.

Ciliary activity of SIV-preinfected porcine PCLS coinfected with S. suis. PCLS were preinfected with 105 TCID50/ml of either H3N2 or H1N1 for 1 h, washed, and subsequently infected with S. suis strain 10 or 10cpsΔEF as described for bacterial monoinfection. Slices monoinfected with only a viral or bacterial strain served as controls. Ciliary activity was estimated by analyzing ciliary beating of mono-, co-, and uninfected PCLS (Ctr) under the light microscope at 24, 48, and 72 h after bacterial infection (hpi). Results are expressed as means with SD. Significant differences are indicated for Ctr versus infected slices (**, P < 0.01) and (****, P < 0.001), for strain 10 versus H3N2 plus strain 10 (++, P < 0.01; +++, P < 0.001), for 10cpsΔEF versus H3N2 plus 10cpsΔEF (#, P < 0.05; ###, P < 0.001), and for H1N1 versus H3N2 (††, P < 0.01; †††, P < 0.001) and were determined by one-way-ANOVA followed by a Tukey post hoc test.

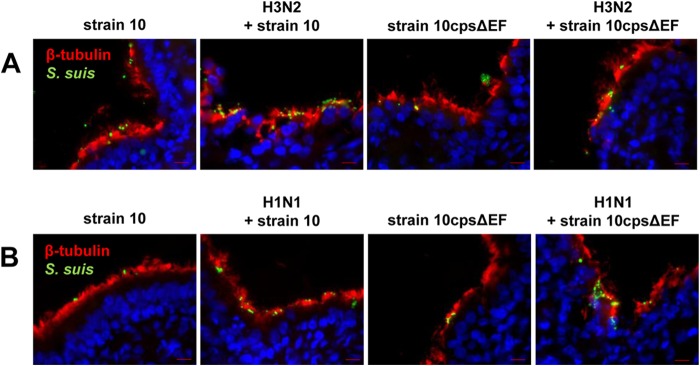

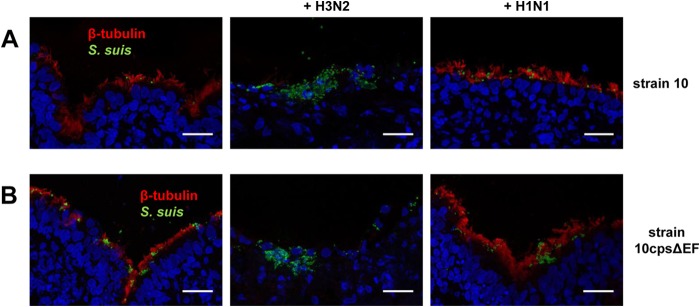

Second, we analyzed PCLS coinfected for up to 72 h by immune fluorescence microscopy of cryosections costained for ciliated cells and S. suis. At 24 and 48 hpi, an intact layer of ciliated cells was detected in mono- and coinfected PCLS slices. Both S. suis strains adhered preferentially to these cells (Fig. 6). In contrast, at 72 hpi, ciliated cells could be detected only in PCLS monoinfected with S. suis and those which had been coinfected with subtype H1N1 strain and S. suis but not in PCLS coinfected with H3N2 and S. suis (Fig. 7). Furthermore, only in the latter case was S. suis detected in deeper layers of the PCLS. These observations were similar to those for the S. suis wt strain and the unencapsulated mutant, indicating that the bacterial capsule was not involved in the attachment to the subepithelial cells.

FIG 6.

Costaining of ciliated epithelial cells and S. suis in porcine PCLS preinfected with SIV and coinfected with S. suis at early stage of infection. Porcine PCLS were preinfected with 105 TCID50/ml H3N2 or H1N1 for 1 h, washed, and subsequently infected with S. suis strain 10 or 10cpsΔEF as described for bacterial monoinfection. Slices monoinfected with strains 10 and 10cpsΔEF served as a control. Streptococci are shown in green, ciliated cells were stained using anti-β-tubulin antibody (red), and nuclei were labeled by DAPI (blue). Bars represent 10 μm. (A) Immunostained cryosections of adherent bacteria of PCLS slices preinfected with H3N2 24 h after bacterial infection. (B) Immunostained cryosections of adherent bacteria of PCLS slices preinfected with H1N1 48 h after bacterial infection.

FIG 7.

Invasion and damage of the bronchiolar epithelium of porcine PCLS preinfected with SIV and coinfected with S. suis at late stage of infection. Porcine PCLS were preinfected with 105 TCID50/ml H3N2 or H1N1 for 1 h, washed, and subsequently infected with S. suis strain 10 (A) or 10cpsΔEF (B) as described for bacterial monoinfection. Slices monoinfected with strain 10 and 10cpsΔEF only served as a control. Cryosection of slices followed by immunostaining was performed 72 h after bacterial infection. Maximum intensity projections of confocal stacks showing streptococci are in green, ciliated cells were stained using anti-β-tubulin antibody (red), and nuclei were labeled by DAPI (blue). Bars represent 25 μm.

Taken together, we established a PCLS coinfection model that allowed us to characterize interactions of SIV and S. suis with respiratory cells that are close to the in vivo situation. Results show that these interactions are beneficial for S. suis, in that its adherence, colonization, and invasion is promoted by SIV. Most interestingly, these effects are mediated not only by capsule-dependent adherence of S. suis to SIV-infected cells but also by SIV-induced damage of ciliated epithelial cells occurring at later time points. These findings show the dynamics of virus-bacterium interactions during coinfections and also suggest that the role of bacterial capsule in adherence, colonization, and invasion of S. suis has to be reconsidered.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to establish an ex vivo PCLS infection model for S. suis and to use this model to gain insights into interactions between SIV and S. suis during infection of differentiated respiratory epithelial cells. PCLS have been used previously to study a variety of viral infections, such as SIV and PRRS (4, 29), but has hardly been used for bacterial pathogens (30). Porcine PCLS have not yet been used for viral-bacterial coinfections. Few studies on coinfections of SIV and S. suis have been published recently (25, 31, 32), but these were performed with NPTr cells, an immortalized porcine tracheal cell line, which limits conclusions on the in vivo situation.

Our results of monoinfection experiments with porcine PCLS confirmed that this cell system is suitable to study S. suis adherence, colonization, and invasion. S. suis adhered to and efficiently colonized ciliated cells and mucus of the bronchiolar epithelium. In agreement with previous results (13, 16) but in contrast to findings by Wang et al. using new-born pig tracheal cells (25), attachment of S. suis to PCLS was facilitated by suilysin. Most interestingly, we found that the encapsulated strain was as adherent as the unencapsulated mutant, which differs from what we and others have observed using conventional immortalized monolayer cell culture systems (12, 13, 25). Notably, we observed different adherence patterns of the encapsulated S. suis strain, which adhered homogenously to all cell types, and the unencapsulated mutant strain, which showed a cluster-like adherence, preferentially to mucus. We speculate that biofilm formation contributes to these differences. Tanabe et al. reported a positive correlation between the absence of capsule and biofilm formation in S. suis, and in S. pneumoniae, downregulation of the capsule cpsA gene during biofilm growth has been reported (33, 34). In addition, mucin was found to enhance biofilm formation of other bacteria (35, 36). Hence, biofilms produced by S. suis adherent to mucin-producing cells may play a role in colonization, but this remains to be studied further. Taken together, our results show that the role of the capsule (and regulation of its expression) in colonization and infection of mucosal surfaces should be reconsidered and further studied.

Our main objective was to study coinfection of SIV and S. suis using the established PCLS model. Coinfections are known to be multifactorial and dynamic processes depending on the viral and bacterial strain, the initial dose of infectious agents, and host factors, including innate immunity (37, 38). Due to this complexity, it is difficult to dissect the different mechanisms of virus-bacterium-host interactions which contribute to copathogenesis in polymicrobial infections of the respiratory tract. As mentioned above, most coinfection studies, including the very few on SIV and S. suis, have been performed with immortalized cell lines which hardly reflect the complex in vivo situation. The PCLS coinfection model established in the present study has the advantage that it is comprised of different types of differentiated airway epithelial cells in the natural tissue context and, furthermore, that it allows us to analyze ciliary activity as part of the mucociliary barrier. Thus, it reflects in vivo conditions very well.

Our results show that coinfection is a dynamic process consisting of different effects of SIV on S. suis infection during early (adherence, colonization) and late stages of infection (damage to host cells and invasion of deeper tissues). At early stages (24 and 48 hpi), adherence and colonization of the encapsulated S. suis wt strain was efficiently enhanced by SIV preinfection, whereas the unencapsulated strain was not affected. The clear colocalization of encapsulated S. suis with SIV-infected cells suggests that the effect is mediated by a capsule-dependent interaction between S. suis and SIV, most likely involving sialic acid residues. The polysaccharide capsule of S. suis serotype 2 strains (including the strain used in this study) is composed of an oligosaccharide core structure that contains terminal sialic acid residues which are α-2,6-linked to galactose (39–41). During influenza virus replication, the release of new virions from a host cell is preceded by expression of viral surface proteins, including hemagglutinins, on the host cell membrane (42), which may serve as receptors for enhanced binding of sialic acid-containing (encapsulated) S. suis. Accordingly, it has been reported recently that capsular sialic acid plays a major role in interactions of SIV with S. suis in coinfected NPTr cells (25). Our results strengthen these findings and further indicate that sialic acid facilitates bacterial colonization of the airway.

Following coinfection of PCLS up to 72 hpi, we observed that enhanced adherence of S. suis at a later stage of infection was seen only with the subtype H3N2 strain, unlike the earlier time points. Furthermore, only at 72 hpi were these effects also observed with the unencapsulated mutant. Our previous studies had revealed differences between both virus strains in that only the subtype H3N2, but not the H1N1 strain, impaired ciliary activity in a PCLS infection model (4). It is known that viral propagation along the respiratory tract can lead to ciliostatic effects, resulting in a reduced mucociliary clearance and enhanced bacterial attachment (43). Therefore, we assume that virus-induced effects on ciliated epithelial cells are involved in the capsule-independent effects of SIV on S. suis infection observed at late infection stages. This assumption is supported by the clear correlation of H3N2-induced loss of ciliary activity and enhanced infection of S. suis shown in the present study.

Bacteria and bacterial toxins also can affect ciliary beat frequency. For instance, pneumolysin, the cytotoxin of S. pneumoniae, was shown to decrease the ciliary beat frequency and damage to the adenoid mucosa (44) and, in another study, to disintegrate the respiratory epithelium, accompanied by a persistent but uncoordinated ciliary beating (45). However, in the present study ciliary activity was unaffected by S. suis (and its cytotoxin, suilysin), as demonstrated in mono- and coinfection experiments. Hence, suilysin seems not to be involved in ciliostatic processes.

In addition to effects on ciliary activity, we found evidence for damage of ciliated epithelial cells in PCLS coinfected for 72 hpi, as revealed from confocal microscopy of immunostained cryosections (Fig. 7). Cellular damage was accompanied with enhanced bacterial invasion of deeper tissue layers. From these and the above-mentioned results, we conclude that SIV-induced reduction of ciliary activity and damage of ciliated cells at later time points of infection promote adherence and invasion of S. suis in a capsule-independent manner. The fact that PCLS allow us to analyze infection of both the ciliated epithelium and the subepithelial cells underlines the value of this culture system. Nevertheless, it has to be considered that the PCLS model does not include neutrophils and macrophages. Both are important cells of cellular innate immunity and are of crucial importance for the clearance of bacteria, e.g., as recently shown for S. pneumoniae (46).

It has been reported that pulmonary coinfections result in reduced lung repair and impaired regeneration mechanisms of the respiratory mucosa (47). Furthermore, cell-degrading processes due to viral infection may provide nutrients for a rapid growth of cocolonizing pathogenic bacteria, and disruption of the epithelial cell layer may allow access to subepithelial cells and expose additional structures for bacterial attachment (48). For S. suis, future studies using ex vivo models, such as PCLS, and in vivo studies in mice and piglets are needed to further dissect the mechanisms of capsule-independent promotion of adherence, colonization, and invasion by SIV.

Taking our results together, we conclude that preinfection of respiratory epithelial cells by SIV is beneficial for S. suis, since bacterial adherence, colonization, and invasion of deeper tissues is efficiently promoted. These effects appear to be based on different mechanisms occurring at different time points during infection. At the early stage, bacterial adherence is facilitated by SIV in a capsule-dependent manner, whereas at later stages SIV-induced impairment of the mucociliary barrier seems to play a major role in promotion of bacterial infection, independent of bacterial encapsulation. Whether or not this can be applied to other encapsulated bacteria remains to be elucidated. Nevertheless, since S. suis is a zoonotic pathogen, the two-step mechanism discussed above also may occur in humans coinfected with influenza virus and S. suis. The PCLS infection model is an excellent tool to study this and other aspects of airway coinfections to better understand the role of multimicrobial interactions in the pathogenesis of pneumonia.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung to G.H. (FluResearchNet; project code 01KI1006D) and the Niedersachsen-Research Network on Neuroinfectiology (N-RENNT) of the Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony to P.V.-W. F.M. was a recipient of a fellowship from the China Scholarship Council. N.H.W. was a recipient of a Georg-Christoph-Lichtenberg scholarship from the Hannover Graduate School for Veterinary Pathobiology, Neuroinfectiology, and Translational Medicine (HGNI).

This work was performed by F.M. and N.H.W. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Ph.D. degrees from the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover.

We thank Hilde E. Smith (Lelystad, Netherlands) for providing S. suis strains 10 and 10cpsΔEF and Ralf Duerrwald (IDT Biologika GmbH, Dessau-Rosslau, Germany) for the SIV strains.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00171-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Opriessnig T, Gimenez-Lirola LG, Halbur PG. 2011. Polymicrobial respiratory disease in pigs. Anim Health Res Rev 12:133–148. doi: 10.1017/S1466252311000120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch AA, Biesbroek G, Trzcinski K, Sanders EA, Bogaert D. 2013. Viral and bacterial interactions in the upper respiratory tract. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003057. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fablet C, Marois C, Kuntz-Simon G, Rose N, Dorenlor V, Eono F, Eveno E, Jolly JP, Le Devendec L, Tocqueville V, Queguiner S, Gorin S, Kobisch M, Madec F. 2011. Longitudinal study of respiratory infection patterns of breeding sows in five farrow-to-finish herds. Vet Microbiol 147:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meng F, Punyadarsaniya D, Uhlenbruck S, Hennig-Pauka I, Schwegmann-Wessels C, Ren X, Durrwald R, Herrler G. 2013. Replication characteristics of swine influenza viruses in precision-cut lung slices reflect the virulence properties of the viruses. Vet Res 44:110. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-44-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyriakis CS, Rose N, Foni E, Maldonado J, Loeffen WL, Madec F, Simon G, Van Reeth K. 2013. Influenza A virus infection dynamics in swine farms in Belgium, France, Italy and Spain, 2006–2008. Vet Microbiol 162:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottschalk M, Xu J, Calzas C, Segura M. 2010. Streptococcus suis: a new emerging or an old neglected zoonotic pathogen? Future Microbiol 5:371–391. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang J, Wang C, Feng Y, Yang W, Song H, Chen Z, Yu H, Pan X, Zhou X, Wang H, Wu B, Wang H, Zhao H, Lin Y, Yue J, Wu Z, He X, Gao F, Khan AH, Wang J, Zhao GP, Wang Y, Wang X, Chen Z, Gao GF. 2006. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome caused by Streptococcus suis serotype 2. PLoS Med 3:e151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva LM, Baums CG, Rehm T, Wisselink HJ, Goethe R, Valentin-Weigand P. 2006. Virulence-associated gene profiling of Streptococcus suis isolates by PCR. Vet Microbiol 115:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei Z, Li R, Zhang A, He H, Hua Y, Xia J, Cai X, Chen H, Jin M. 2009. Characterization of Streptococcus suis isolates from the diseased pigs in China between 2003 and 2007. Vet Microbiol 137:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith HE, Damman M, van der Velde J, Wagenaar F, Wisselink HJ, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Smits MA. 1999. Identification and characterization of the cps locus of Streptococcus suis serotype 2: the capsule protects against phagocytosis and is an important virulence factor. Infect Immun 67:1750–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charland N, Harel J, Kobisch M, Lacasse S, Gottschalk M. 1998. Streptococcus suis serotype 2 mutants deficient in capsular expression. Microbiology 144(Part 2):325–332. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benga L, Goethe R, Rohde M, Valentin-Weigand P. 2004. Non-encapsulated strains reveal novel insights in invasion and survival of Streptococcus suis in epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol 6:867–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seitz M, Baums CG, Neis C, Benga L, Fulde M, Rohde M, Goethe R, Valentin-Weigand P. 2013. Subcytolytic effects of suilysin on interaction of Streptococcus suis with epithelial cells. Vet Microbiol 167:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs AAC, Loeffen PLW, van den Berg AJG, Storm PK. 1994. Identification, Purification, and characterization of a thiol-activated hemolysin (Suilysin) of Streptococcus suis. Infect Immun 62:1742–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu L, Huang B, Du H, Zhang XC, Xu J, Li X, Rao Z. 2010. Crystal structure of cytotoxin protein suilysin from Streptococcus suis. Protein Cell 1:96–105. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0012-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norton PM, Rolph C, Ward PN, Bentley RW, Leigh JA. 1999. Epithelial invasion and cell lysis by virulent strains of Streptococcus suis is enhanced by the presence of suilysin. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 26:25–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tenenbaum T, Adam R, Eggelnpohler I, Matalon D, Seibt A, Novotny GE, Galla HJ, Schroten H. 2005. Strain-dependent disruption of blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier by Streptococcus suis in vitro. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 44:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benga L, Fulde M, Neis C, Goethe R, Valentin-Weigand P. 2008. Polysaccharide capsule and suilysin contribute to extracellular survival of Streptococcus suis co-cultivated with primary porcine phagocytes. Vet Microbiol 132:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lecours MP, Gottschalk M, Houde M, Lemire P, Fittipaldi N, Segura M. 2011. Critical role for Streptococcus suis cell wall modifications and suilysin in resistance to complement-dependent killing by dendritic cells. J Infect Dis 204:919–929. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du H, Huang W, Xie H, Ye C, Jing H, Ren Z, Xu J. 2013. The genetically modified suilysin, rSLY(P353L), provides a candidate vaccine that suppresses proinflammatory response and reduces fatality following infection with Streptococcus suis. Vaccine 31:4209–4215. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seitz M, Beineke A, Singpiel A, Willenborg J, Dutow P, Goethe R, Valentin-Weigand P, Klos A, Baums CG. 2014. Role of capsule and suilysin in mucosal infection of complement-deficient mice with Streptococcus suis. Infect Immun 82:2460–2471. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00080-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson JC, Scalera V, Simmons NL. 1981. Identification of two strains of MDCK cells which resemble separate nephron tubule segments. Biochim Biophys Acta 673:26–36. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(81)90307-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goris K, Uhlenbruck S, Schwegmann-Wessels C, Kohl W, Niedorf F, Stern M, Hewicker-Trautwein M, Bals R, Taylor G, Braun A, Bicker G, Kietzmann M, Herrler G. 2009. Differential sensitivity of differentiated epithelial cells to respiratory viruses reveals different viral strategies of host infection. J Virol 83:1962–1968. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01271-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Punyadarsaniya D, Liang CH, Winter C, Petersen H, Rautenschlein S, Hennig-Pauka I, Schwegmann-Wessels C, Wu CY, Wong CH, Herrler G. 2011. Infection of differentiated porcine airway epithelial cells by influenza virus: differential susceptibility to infection by porcine and avian viruses. PLoS One 6:e28429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Gagnon CA, Savard C, Music N, Srednik M, Segura M, Lachance C, Bellehumeur C, Gottschalk M. 2013. Capsular sialic acid of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 binds to swine influenza virus and enhances bacterial interactions with virus-infected tracheal epithelial cells. Infect Immun 81:4498–4508. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00818-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCullers JA. 2014. The co-pathogenesis of influenza viruses with bacteria in the lung. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siegel SJ, Roche AM, Weiser JN. 2014. Influenza promotes pneumococcal growth during coinfection by providing host sialylated substrates as a nutrient source. Cell Host Microbe 16:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chertow DS, Memoli MJ. 2013. Bacterial coinfection in influenza: a grand rounds review. JAMA 309:275–282. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.194139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobrescu I, Levast B, Lai K, Delgado-Ortega M, Walker S, Banman S, Townsend H, Simon G, Zhou Y, Gerdts V, Meurens F. 2014. In vitro and ex vivo analyses of co-infections with swine influenza and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses. Vet Microbiol 169:18–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebsen M, Mogilevski G, Anhenn O, Maiworm V, Theegarten D, Schwarze J, Morgenroth K. 2002. Infection of murine precision cut lung slices (PCLS) with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and Chlamydophila pneumoniae using the Krumdieck technique. Pathol Res Pract 198:747–753. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang K, Lu C. 2008. Streptococcus suis type 2 culture supernatant enhances the infection ability of the Swine influenza virus H3 subtype in MDCK cells. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 121:198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dang Y, Lachance C, Wang Y, Gagnon CA, Savard C, Segura M, Grenier D, Gottschalk M. 2014. Transcriptional approach to study porcine tracheal epithelial cells individually or dually infected with swine influenza virus and Streptococcus suis. BMC Vet Res 10:86. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-10-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall-Stoodley L, Nistico L, Sambanthamoorthy K, Dice B, Nguyen D, Mershon WJ, Johnson C, Hu FZ, Stoodley P, Ehrlich GD, Post JC. 2008. Characterization of biofilm matrix, degradation by DNase treatment and evidence of capsule downregulation in Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates. BMC Microbiol 8:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanabe S, Bonifait L, Fittipaldi N, Grignon L, Gottschalk M, Grenier D. 2010. Pleiotropic effects of polysaccharide capsule loss on selected biological properties of Streptococcus suis. Can J Vet Res 74:65–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landry RM, An D, Hupp JT, Singh PK, Parsek MR. 2006. Mucin-Pseudomonas aeruginosa interactions promote biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. Mol Microbiol 59:142–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mothey D, Buttaro BA, Piggot PJ. 2014. Mucin can enhance growth, biofilm formation, and survival of Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 350:161–167. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metzger DW, Sun K. 2013. Immune dysfunction and bacterial coinfections following influenza. J Immunol 191:2047–2052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith AM, Adler FR, Ribeiro RM, Gutenkunst RN, McAuley JL, McCullers JA, Perelson AS. 2013. Kinetics of coinfection with influenza A virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003238. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charland N, Kellens JT, Caya F, Gottschalk M. 1995. Agglutination of Streptococcus suis by sialic acid-binding lectins. J Clin Microbiol 33:2220–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith HE, de Vries R, van't Slot R, Smits MA. 2000. The cps locus of Streptococcus suis serotype 2: genetic determinant for the synthesis of sialic acid. Microb Pathog 29:127–134. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2000.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Calsteren MR, Gagnon F, Lacouture S, Fittipaldi N, Gottschalk M. 2010. Structure determination of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 capsular polysaccharide. Biochem Cell Biol 88:513–525. doi: 10.1139/O09-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neumann G, Noda T, Kawaoka Y. 2009. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature 459:931–939. doi: 10.1038/nature08157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pittet LA, Hall-Stoodley L, Rutkowski MR, Harmsen AG. 2010. Influenza virus infection decreases tracheal mucociliary velocity and clearance of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 42:450–460. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0417OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rayner CF, Jackson AD, Rutman A, Dewar A, Mitchell TJ, Andrew PW, Cole PJ, Wilson R. 1995. Interaction of pneumolysin-sufficient and -deficient isogenic variants of Streptococcus pneumoniae with human respiratory mucosa. Infect Immun 63:442–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fliegauf M, Sonnen AF, Kremer B, Henneke P. 2013. Mucociliary clearance defects in a murine in vitro model of pneumococcal airway infection. PLoS One 8:e59925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Z, Clarke TB, Weiser JN. 2009. Cellular effectors mediating Th17-dependent clearance of pneumococcal colonization in mice. J Clin Investig 119:1899–1909. doi: 10.1172/JCI36731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kash JC, Walters KA, Davis AS, Sandouk A, Schwartzman LM, Jagger BW, Chertow DS, Li Q, Kuestner RE, Ozinsky A, Taubenberger JK. 2011. Lethal synergism of 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae coinfection is associated with loss of murine lung repair responses. mBio 2:e00172–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00172-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCullers JA, Rehg JE. 2002. Lethal synergism between influenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization of a mouse model and the role of platelet-activating factor receptor. J Infect Dis 186:341–350. doi: 10.1086/341462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.