Abstract

Desformylflustrabromine (dFBr) is a positive allosteric modulator (PAM) of α4β2 and α2β2 nAChRs that, at concentrations >1 µM, also inhibits these receptors and α7 nAChRs. However, its interactions with muscle-type nAChRs have not been characterized, and the locations of its binding site(s) in any nAChR are not known. We report here that dFBr inhibits human muscle (αβεδ) and Torpedo (αβγδ) nAChR expressed in Xenopus oocytes with IC50 values of ∼1 μM. dFBr also inhibited the equilibrium binding of ion channel blockers to Torpedo nAChRs with higher affinity in the nAChR desensitized state ([3H]phencyclidine; IC50 = 4 μM) than in the resting state ([3H]tetracaine; IC50 = 60 μM), whereas it bound with only very low affinity to the ACh binding sites ([3H]ACh, IC50 = 1 mM). Upon irradiation at 312 nm, [3H]dFBr photoincorporated into amino acids within the Torpedo nAChR ion channel with the efficiency of photoincorporation enhanced in the presence of agonist and the agonist-enhanced photolabeling inhibitable by phencyclidine. In the presence of agonist, [3H]dFBr also photolabeled amino acids in the nAChR extracellular domain within binding pockets identified previously for the nonselective nAChR PAMs galantamine and physostigmine at the canonical α-γ interface containing the transmitter binding sites and at the noncanonical δ-β subunit interface. These results establish that dFBr inhibits muscle-type nAChR by binding in the ion channel and that [3H]dFBr is a photoaffinity probe with broad amino acid side chain reactivity.

Introduction

nAChRs are pentameric ligand-gated ion channels that are expressed at the vertebrate neuromuscular junction (muscle-type nAChR) and at postsynaptic and presynaptic nerve terminals throughout the nervous system (neuronal-type nAChR) (Dani and Bertrand, 2007; Gotti et al., 2009). Drugs that modulate nAChR function have potential therapeutic uses in the treatment of many cognitive and neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Gotti and Clementi, 2004; Jensen et al., 2005; Taly et al., 2009).

Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of nAChRs have been introduced as a novel physiologic approach to enhance nAChR function (Faghih et al., 2008; Arias, 2010; Williams et al., 2011). A nAChR PAM, by definition, binds at site(s) distinct from the ACh binding (i.e., orthosteric) site and enhances the effects of ACh. Endogenous and exogenous compounds with a variety of structural motifs have been shown to potentiate the action of ACh at nAChRs, which suggests the presence of more than one class of nAChR PAM binding sites (Bertrand and Gopalakrishnan, 2007; Changeux and Taly, 2008). In agreement with this notion, potential PAM binding sites have been identified within the extracellular domain (ECD) and transmembrane domain (TMD) of nAChRs. Within the TMD, an intrasubunit PAM binding site in α7 nAChR was identified by mutational analyses (Young et al., 2008; daCosta et al., 2011), and photoaffinity labeling identified an intersubunit site in muscle-type nAChR (Nirthanan et al., 2008). Within the ECD, PAM binding sites were identified in secondary pockets at the agonist-binding canonical interfaces (Ludwig et al., 2010; Hamouda et al., 2013), at noncanonical interfaces (Seo et al., 2009; Hamouda et al., 2013; Olsen et al., 2014), and near the M2-M3 loop (Bertrand et al., 2008).

Desformylflustrabromine (dFBr) (Fig. 1), isolated originally from the marine bryozoan Flustra foliacea (Peters et al., 2002), acts as a neuronal nAChR PAM, enhancing, at concentrations <1 µM, peak ACh responses of α4β2 (Sala et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2007; German et al., 2011) and α2β2 (Pandya and Yakel, 2011) nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. At higher concentrations, dFBr inhibited these receptors and α7 nAChRs (Kim et al., 2007). Subcutaneous administration of dFBr to rats resulted in reduced nicotine self-administration (Liu, 2013). Whereas the effects of dFBr at several neuronal nAChRs have been characterized, its interactions with muscle-type nAChRs have not been characterized, and there has been no localization of its binding site(s) in any nAChR.

Fig. 1.

Structure of dFBr.

Here, we use two-electrode voltage clamp recording to assess the effects of dFBr on human and Torpedo muscle-type nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. We also use the intrinsic photoreactivity of the newly synthesized ligand, [3H]dFBr, to identify its binding sites within the Torpedo nAChR. Adult human and Torpedo muscle-type nAChRs have subunit stoichiometries of α2βεδ and α2βγδ, respectively. Each nAChR subunit comprises an extracellular N-terminal domain consisting of a 10-strand β sandwich, a TMD consisting of four transmembrane helices (M1–M4), and an unstructured cytoplasmic domain comprised of the M3–M4 intracellular loop (Unwin, 2005). ACh-binding sites are located within the ECD at the two α subunit interfaces (α-ε/γ and α-δ) and the ion channel is lined by each subunit’s M2 helix. We found that dFBr inhibits muscle-type nAChRs due to high-affinity binding in the ion channel, but it also binds within the Torpedo nAChR ECD at binding sites identified previously for galantamine and physostigmine, i.e., nonselective nAChR PAMs (Hamouda et al., 2013).

Materials and Methods

dFBr hydrochloride and des-methyl dFBr hydrochloride (6-bromo-2-(1,1-dimethylallyl)tryptamine) were synthesized as previously described (German et al., 2011). [3H]dFBr (76 Ci/mmol) was prepared by custom tritiation (Vitrax, Placentia, CA) by reaction of des-methyl dFBr hydrochloride with [3H]CH3I.

nAChR Expression in Xenopus Oocytes.

Plasmids with cDNA encoding human α1 (pSPα64T), β1 (pBSII), δ [pBS(SK)], and ε (pBSII) nAChR subunits were generously provided by Dr. Jon Lindstrom (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia). Plasmids with cDNA encoding the Torpedo α1, γ and δ (pMXT), and Torpedo β1 (pSP6) were gifts from Dr. Michael M. White (Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia) and Dr. Henry Lester (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA), respectively. Plasmids were linearized with BsaAI (Hδ), FspI (Hα1 and Tβ), ScaI (Hβ1), XbaI (Tα, Tγ, and Tδ), and XhoI (Hε). cRNA transcripts were prepared from linearized plasmids using SP6 (Torpedo α, β, γ, and δ and Human α1) or T3 (Human β1, δ, and ε) polymerase using mMESSAGE mMACHINE high-yield capped RNA transcription kits (Ambion/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Leucine-to-serine substitutions at position M2-9′ (αLeu251, βLeu257, γLeu260, and δLeu265) were introduced into plasmid expression vectors coding for the Torpedo nAChR subunits using the Quick Change II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and custom-designed oligos containing the desired mutation (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). Mutations were confirmed by sequencing the entire coding region.

Ovarian lobules were removed surgically from adult, female Xenopus laevis following animal use protocols approved by the Texas A&M Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The lobules were treated with 3 mg/ml collagenase type 2 (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) with gentle shaking for 3 hours at room temperature in Ca+2-free OR2 buffer (85 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.6). Stage V and VI oocytes were selected, injected with cRNA, and incubated at 18°C in ND96-gentamicine buffer (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 50 µg/ml gentamicin, pH 7.6) for 24–72 hours to allow receptor expression. For Torpedo and human muscle nAChRs, oocytes were injected with 20–50 ng total mRNA mixed at ratios of 2α:1β:1γ:1δ and 2α:1β:1δ:1ε, respectively.

Electrophysiological Recording.

The effects of dFBr on ACh-induced current responses were examined using standard two-electrode voltage clamp techniques. Oocytes in the recording chamber were perfused with ND96 recording buffer (100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5), and voltage-clamped at −50 mV using Oocyte Clamp OC-725B (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT), and whole cell currents were digitized using Digidata 1440A/Clampex 10.4 (Axon Instruments/Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). An automated perfusion system (Warner Instruments) was used to control recording chamber perfusion and drug application. Each recording run included 3–6 applications of ACh or dFBr alone or in combination. Drug applications were separated by 1–3-minute wash intervals. Each drug concentration was tested at least three times and repeated on at least two oocytes. Currents were quantified using pCLAMP 10.4 (Axon Instruments), and then normalized to the peak current elicited by ACh alone. Data (average ± S.E.) were fit to a single-site model of inhibition (see Data Analyses).

Radioligand Binding Assays.

Centrifugation assays (Hamouda et al., 2011) were used to determine the effects of dFBr on the equilibrium binding by Torpedo nAChR of [3H]ACh (1.9 Ci/mmol), phencyclidine hydrochloride (PCP; 27 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Billerica, MA), and [3H]tetracaine (30 Ci/mmol; SibTech, Brookfield, CT), and the effects of dFBr, PCP, and tetracaine on the equilibrium binding of [3H]dFBr. nAChR-rich membranes, isolated from Torpedo californica electric organs as previously described (Middleton and Cohen, 1991), were resuspended in Torpedo physiologic saline (250 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 3 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0). Binding of [3H]ACh (15 nM) was determined using 40 nM ACh binding sites to allow detection of either enhancement or inhibition of binding. These membrane suspensions were pretreated with 0.5 mM diisopropylphosphofluoridate to inhibit acetylcholinesterase. Binding of [3H]tetracaine (10 nM), [3H]PCP (10 nM), and [3H]dFBr (4 nM) was determined using 0.7 µM ACh binding sites in the presence of the competitive antagonist α-bungarotoxin (α-BgTx; 5 μM) or the agonist carbamylcholine chloride (Carb; 1 mM) to stabilize the nAChR in the resting or desensitized state, respectively. Bound and free 3H were separated by centrifugation (18,000g for 1 hour), then quantified by liquid scintillation counting. Specifically bound 3H (total-nonspecific) was normalized to the specifically bound 3H in the absence of competitor. Binding (total-nonspecific) were: for [3H]ACh (±1 mM Carb, 7200 ± 60/83 ± 3 cpm); for [3H]PCP (+Carb, ±300 µM proadifen, 9000 ± 80/1310 ± 15 cpm; +α-BgTx, ±300 µM tetracaine, 3300 ± 90/1520 ± 15 cpm); and for [3H]tetracaine (+α-BgTx, ±300 µM tetracaine, 23,600 ± 1800/4360 ± 35 cpm). For direct [3H]dFBr binding, the total bound 3H was converted to the concentration (in nanomolar) of bound dFBr.

Data Analyses.

Current responses and binding data were analyzed using SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). The effects of drugs on [3H]dFBr binding were fit to one or two-site models using eqs. 1 and 2, respectively. All other inhibition data were normalized and fit to a single-site model using eq. 3

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where fx is radioligand binding or ACh current measured in the presence of inhibitor at concentration x; f0 is the specific radioligand binding/ACh current in the absence of inhibitor; IC50 is the total concentration of inhibitor that inhibits 50% of the total specific radioligand binding/ACh current, with H and L denoting the high- and low-affinity sites; and Bns is the nonspecific binding. For adjustable parameters, best-fit values ± S.E. are presented.

[3H]dFBr Photolabeling of Torpedo nAChR.

Analytical (150 pmol ACh binding sites/condition) and preparative (15 nmol ACh binding sites/condition) [3H]dFBr photolabeling of Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes were performed at 2 mg protein/ml in Torpedo physiologic saline and 0.5 µM [3H]dFBr, as previously described (Garcia et al., 2007; Hamouda et al., 2011). In initial analytical photolabeling experiments, [3H]dFBr photoincorporation into the nAChR was compared after photolysis at 254 nm (5 minutes), 312 nm (5 and 10 minutes), and 365 nm (30 minutes) using Spectronics Corporation (Westbury, NY) hand-held lamps. Only photolysis at 312 nm resulted in significant photoincorporation of [3H]dFBr into nAChR subunits, with equal photoincorporation observed at 5 and 10 minutes. For subsequent experiments, Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes were incubated with [3H]dFBr for 40 minutes at 4°C in the absence or presence of other drugs and then irradiated on ice at 312 nm for 5 minutes at a distance of less than 2 cm. Photolabeled nAChR-rich membranes were denatured in SDS sample buffer and then resolved on 8% polyacrylamide gels, with the polypeptides visualized by Coomassie Blue R-250 stain (White and Cohen, 1988). In analytical experiments, [3H]dFBr photoincorporation into polypeptides was visualized by fluorography and quantified by liquid scintillation counting of excised gel bands. For photolabeling on a preparative scale, gel bands containing nAChR subunits were excised. The α subunit band was transferred directly to 15% polyacrylamide gels and subjected to in-gel digestion with 100 μg Staph aureus endoproteinase Glu-C (V8 protease) (MP Biomedical, Santa Ana, CA) as previously described (Blanton and Cohen, 1994). The β, γ, and δ nAChR subunits and α nAChR subunit fragments (αV8-20, αV8-18, αV8-10, and αV8-4) were recovered from gel bands by passive elution, and then concentrated and resuspended in digestion buffer (15 mM Tris, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.1).

Proteolytic Digestion, Peptide Isolation, and N-Terminal Sequencing.

Enzymatic digestions of nAChR subunits and subunit fragments, reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (rpHPLC), and automated Edman protein microsequencing were performed as detailed previously (Chiara et al., 2009a). Briefly, rpHPLC was performed on an HP1100 binary system (Agilent Technologies) using a Brownlee Aquapore BU-300 column (PerkinElmer) with material eluted at 0.2 ml/min using a linear (0–100%) or nonlinear gradient (25–100%) of acetonitrile/isopropanol (3:2, 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid) over 100 minutes. Peak 3H rpHPLC fractions were loaded on trifluoroacetic acid–treated glass fiber filters and sequenced on an Applied Biosystems PROCISE 492 protein sequencer (Life Technologies). At each cycle of Edman degradation, 1/6 was used for amino acid identification/quantification and 5/6 for 3H counting. The efficiency of photolabeling (Ex, in cpm/pmol) for an amino acid in cycle x of Edman degradation was calculated using the equation  ; where cpmx is the counts per minute in cycle x, I0 is the calculated initial mass in picomoles of the peptide sequenced, and R is the calculated repetitive yield of Edman degradation.

; where cpmx is the counts per minute in cycle x, I0 is the calculated initial mass in picomoles of the peptide sequenced, and R is the calculated repetitive yield of Edman degradation.

To isolate nAChR subunit fragments beginning at βMet249, the N-terminus of βM2, at δPhe206 before δM1, and at δMet257, the N-terminus of δM2, l-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethylchloromethyketone–treated trypsin (Worthington Biomedical) digests of the β subunit (Chiara et al., 2009a) and Lysobacter enzymogenes endoproteinase Lys-C (EndoLys-C) (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) digests of the δ subunit (Arevalo et al., 2005) were fractionated on small pore (16.5%T, 6%C) Tricine SDS-PAGE gels (Schägger and von Jagow, 1987). The polypeptides eluted from gel bands with apparent molecular masses of ∼8 kDa (β) and 10–14 kDa (δ) were then fractionated by rpHPLC to isolate the peptide beginning at βMet249, which elutes at ∼80% organic (Chiara et al., 2009a), and the peptides beginning at δPhe206 and δMet257, which elute at ∼60 and 75% organic, respectively (Arevalo et al., 2005).

Peptides beginning at the N-terminus of αM2 (αMet243) and at αHis184 were isolated by rpHPLC fractionation of an EndoLys-C digest of the αV8-20 fragment, which begins at αSer-173 and contains agonist binding site Segment C and the αM1, αM2, and αM3 helices (Blanton and Cohen, 1994; Pratt et al., 2000). A peptide beginning at αLys77 that contains ACh binding site Segment A was isolated by rpHPLC fractionation of an EndoLys-C digest of the αV8-18 fragment, which begins at αThr52 (Ziebell et al., 2004). A fragment beginning at γVal102 that contains ACh binding site Segment E was isolated as previously described (Chiara et al., 2003) by rpHPLC fractionation of a V8 protease digest of a 30 kDa γ subunit fragment isolated by Tricine SDS-PAGE from an EndoLys-C digest of [3H]dFBr-photolabeled γ subunit.

Molecular Modeling and Computational Analyses.

For docking in the ECD, the Discovery Studio software package (Accelrys, Inc., San Diego, CA) was used to construct a homology model of the Torpedo nAChR ECD from the X-ray structure of the Carb-bound form of the L-AChBP PDB ID 1UV6 (Celie et al., 2004). This model (nAChR_TORCA_ECD_from_1UV6.pdb) is available in the Supplemental Material. AutoDock (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA) was used to dock dFBr in binding site grids centered at (1) the α-γ extracellular interface at the entrance to the agonist binding site, including γTyr111 and γTyr117; (2) the α-γ extracellular interface in the vestibule of the ion channel, including γTyr105; and (3) the δ-β extracellular interface, including δTyr212.

For dFBr docking in the ion channel, Discovery Studio was used to construct two Torpedo nAChR models, one based on the cryoelecton microscopy-derived structure of Torpedo marmorata nAChR (PDB ID 2BG9) (Unwin, 2005) and a second based on the X-ray structure of the mouse serotonin 5-HT3 receptor (5-HT3R) PDB ID 4PIR (Hassaine et al., 2014), which also contains a cation selective channel. The full subunit alignments used for the homology model based on the 5-HT3R structure are presented in the Supplemental Material. This model (nAChR_TORCA_from_4PIR.pdb) is available in the Supplemental Material. In the Torpedo 2BG9 nAChR and 4PIR 5-HT3R models, the same surface of the M2 helices line the lumen of the ion channel, but the vertical alignment of the M2 helix relative to the M1 and M3 helices differs, with that of the 5-HT3R being similar to the alignment in the other pentameric ligand-gated ion channels of known structure (Hibbs and Gouaux, 2011; Corringer et al., 2012; Miller and Aricescu, 2014). Recent cysteine cross-linking and photolabeling studies provide experimental evidence favoring nAChR homology models based on these X-ray structures for the structure of the nAChR TMD (Mnatsakanyan and Jansen, 2013; Chiara et al., 2014; Hamouda et al., 2014).

The CDOCKER module of Discovery Studio was used to dock dFBr in the ion channel. For each docking experiment 20 randomly oriented replicas of dFBr were seeded in the center of a binding site sphere (radius = 15 Å) positioned to contain the five M2 helices including amino acids M2-2 to M2-20 of each M2 helix. For each seed, CDOCKER was used to generate 10 ligand conformations and the 10 lowest-energy orientations were identified using random rigid-body rotations followed by simulated annealing and a full potential final minimization step. Docking results are shown as Connolly surface representations (1.4 Å diameter probe) of the ensemble of the 100 lowest-energy docking solutions.

Results

dFBr Is a Potent Noncompetitive Inhibitor of Muscle-Type nAChRs.

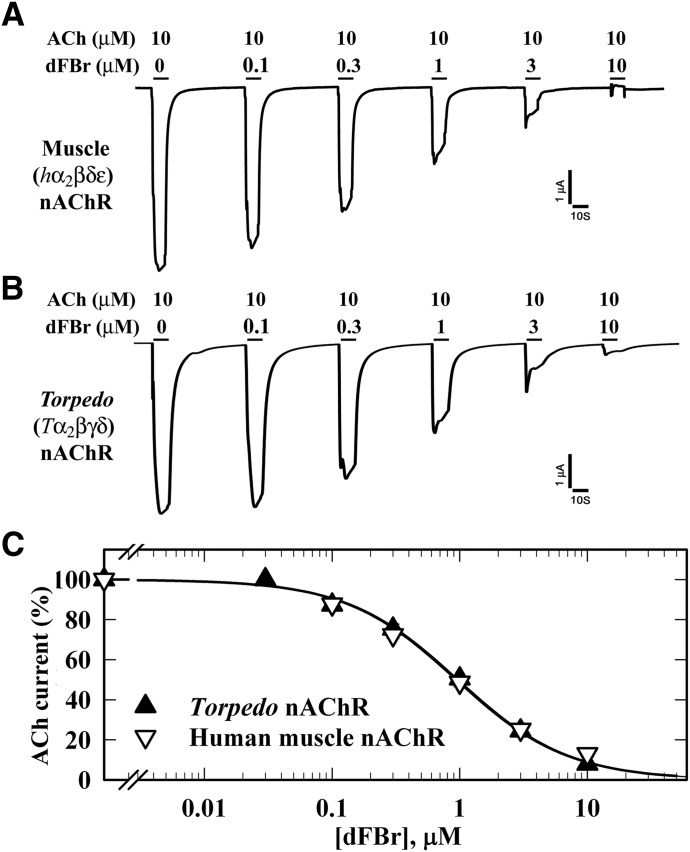

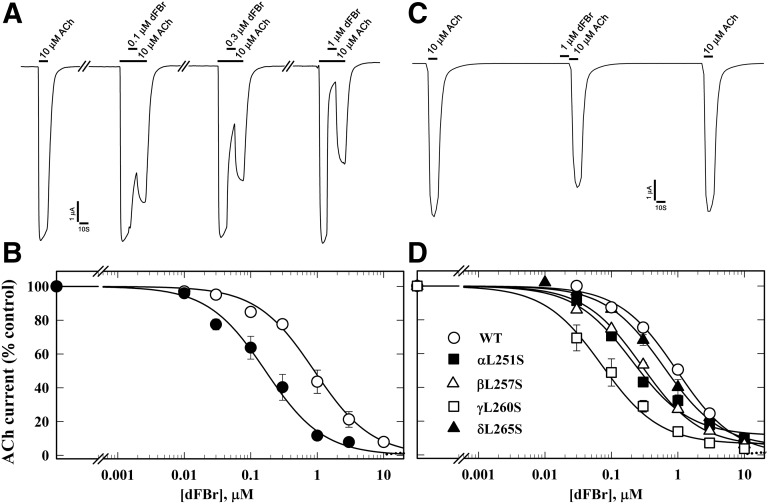

To characterize the effects of dFBr on muscle-type nAChRs, we recorded ACh-induced currents of Xenopus oocytes expressing human muscle (2α:1β:1δ:1ε) or Torpedo (2α:1β:1γ:1δ) nAChR. When tested at concentrations up to 10 µM, dFBr neither directly activated these nAChRs nor potentiated ACh-induced responses. Instead, dFBr was equipotent as an inhibitor of both nAChRs (Fig. 2). When co-applied with ACh for 10 seconds, dFBr reversibly reduced peak current responses with IC50 values of 1.0 ± 0.08 µM. dFBr was 10-fold more potent (IC50 = 0.1 ± 0.01 µM) as a Torpedo nAChR inhibitor when it was co-applied with ACh for 10 seconds immediately following a 10-second application of ACh than when co-applied without prior to exposure to ACh (Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, dFBr was not a potent desensitizing antagonist, because preincubation with 1 µM dFBr for 10 seconds reduced the subsequent ACh-induced response (in the absence of dFBr) by only ∼15% (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that inhibition by dFBr is state dependent and that dFBr might be most potent as an inhibitor of nAChRs in states stabilized only transiently by agonist. To test this, we examined dFBr inhibition of muscle-type nAChRs containing the leucine-to-serine substitutions at position M2-9′ (αLeu251, βLeu257, γLeu260, and δLeu265) that have been shown to decrease ACh EC50 values and increase nAChR channel mean open time (Filatov and White, 1995; Labarca et al., 1995). dFBr was 7-fold more potent as an inhibitor of the γ subunit mutant nAChR than of wild-type and ∼2-fold more potent for the α and β subunit mutants (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 2.

dFBr inhibition of muscle-type nAChRs. Xenopus oocytes expressing wild-type (A) human (2α:1β:1δ:1ε; ▽) or (B) Torpedo (2α:1β:1γ:1δ;▼) nAChR were voltage clamped at −50 mV, and currents elicited by 10 second applications of 10 µM ACh were recorded in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of dFBr. Each drug concentration was tested at least three times and peak currents were normalized to the peak current elicited by 10 µM ACh alone. (C) Data (average ± S.E.) from at least three oocytes were plotted and fit to a single-site model (eq. 3); human nAChR, IC50 = 1.0 ± 0.08 µM; Torpedo nAChR, IC50 = 1.0 ± 0.06 µM.

Fig. 3.

dFBr inhibition of Torpedo nAChR is enhanced in the presence of agonist and by mutations in the ion channel favoring the open state. (A) Representative traces showing the effect of dFBr on ACh-induced current responses when 10 µM ACh was applied for 10 seconds, followed by co-application of 10 µM ACh and dFBr for 10 seconds, and then 10 seconds of 10 µM ACh alone. (B) The concentration dependence of dFBr inhibition when co-applied with ACh as in (A), with the current measured at the end of dFBr co-application normalized to the current just before (⬤, IC50 = 0.12 ± 0.01 µM), compared with a parallel experiment quantifying dFBr inhibition of peak ACh responses without prior ACh exposure (○, dashed line, fit from Fig. 2 for data from 10 oocytes). (C) Representative traces showing the effect of preapplication of 1 µM dFBr for 10 seconds on nAChR sensitivity to ACh. The ACh responses were inhibited by ∼15 ± 3% (N = 6). (D) dFBr inhibition of mutant nAChRs containing leucine to serine substitutions at position M2-9′ within the ion channel, quantified from the peak current elicited by 10 µM ACh with co-application of dFBr normalized to the current in the absence of dFBr. IC50 values for wild type, α, β, γ, and δ M2-9′ mutants were 1.0 ± 0.07, 0.2 ± .04, 0.3 ± 0.03, 0.1 ± 0.02, and 0.5 ± 0.06 µM, respectively. For each dFBr concentration in (B) and (D), average ± S.E. of several replicas from at least three oocytes were plotted and fit to a single-site model.

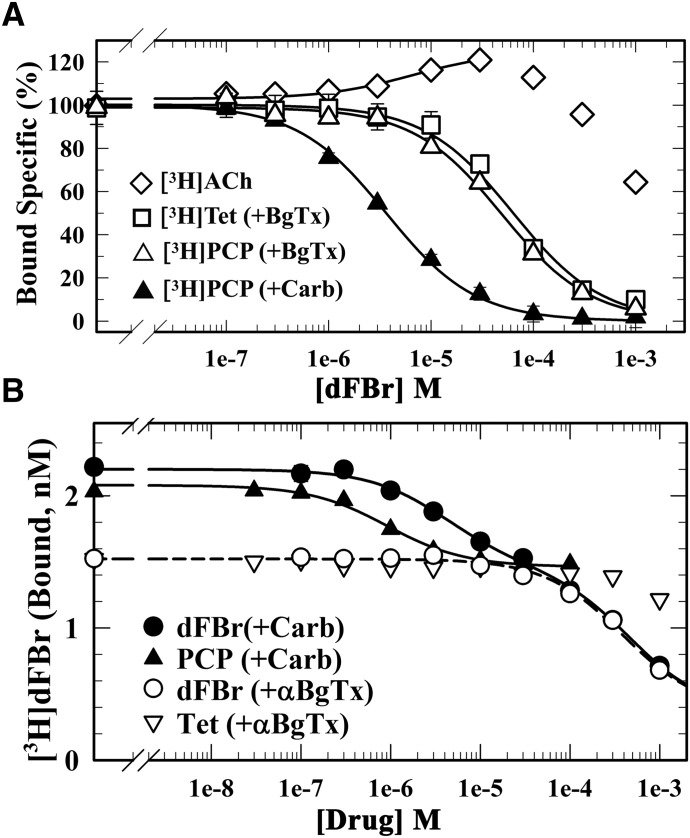

We also used equilibrium radioligand binding assays to characterize the effects of dFBr on the binding of ACh and known channel blockers to Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes (Fig. 4A). dFBr enhanced the equilibrium binding of [3H]ACh at concentrations up to 100 µM and only inhibited binding at higher concentrations. For Torpedo nAChR stabilized in the desensitized state in the presence of the agonist Carb, dFBr was a potent inhibitor of the equilibrium binding of [3H]phencyclidine ([3H]PCP) (IC50 = 3.6 ± 0.2 µM), a desensitized state-selective nAChR channel blocker (Oswald et al., 1983). dFBr was ∼10-fold less potent as an inhibitor of [3H]PCP binding to the nAChR stabilized in the resting, closed-channel state in the presence of the competitive antagonist α-BgTx (IC50 = 49 ± 6 µM) or as an inhibitor of binding of [3H]tetracaine (IC50 = 63 ± 11 µM), a resting state-selective nAChR ion-channel blocker (Middleton et al., 1999).

Fig. 4.

dFBr binds with high affinity to a site in the nAChR ion channel (desensitized state). The effects of dFBr on the equilibrium binding of [3H]ACh, [3H]PCP, and [3H]tetracaine (A) and the effect of dFBr, PCP, and tetracaine on the equilibrium binding of [3H]dFBr (B) to the Torpedo nAChR in the presence of α-BgTx (□, ▽, △) or Carb (⬤, ▴) were determined using centrifugation assays. (A) For each dFBr concentration, the specific binding of the radioligand was calculated from the total and nonspecific binding, normalized to the specific binding in the absence of dFBr, and fit to a single-site model using eq. 3. dFBr enhanced [3H]ACh binding (125% at 30 µM), inhibited [3H]PCP binding (+Carb) with IC50 = 3.6 ± 0.2 µM, and inhibited [3H]PCP and [3H]tetracaine binding in the presence of α-BgTx with IC50 values of 49 ± 6 and 63 ± 11 µM, respectively. (B) For each drug concentration, bound [3H]dFBr (in cpm/ml) was converted to nM [3H]dFBr. Inhibition curves were fit to a single-site model (eq. 1) or for inhibition by nonradioactive dFBr (+Carb) to a two-site model (eq. 2). For PCP (+Carb), IC50 = 0.9 ± 0.1 µM and Bns = 1.4 ± 0.1 nM, respectively. For dFBr (+α-BgTX), IC50 = 380 ± 70 µM, Bspec = 1.1 ± 0.08 nM, and Bns = 0.36 ± 0.09 nM. For inhibition by dFBr (+Carb), the high-affinity component of binding was fixed as the total binding [(+Carb) − (+α-BgTx)], the low-affinity component was equal to Bspec(+α-BgTx), and Bns was the same as in the presence of α-BgTx. With these assumptions, the calculated IC50 values for the high- and low-affinity components of binding were 4.1 ± 0.4 and 460 ± 30 µM, respectively.

Equilibrium Binding of [3H]dFBr.

We characterized the equilbrium binding of [3H]dFBr (4 nM) to Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes (0.7 µM ACh binding sites). As shown in Fig. 4B, [3H]dFBr binding was higher in the desensitized state (+Carb; ∼2.2 nM [3H]dFBr bound) than in the resting state (+α-BgTx; ∼1.5 nM [3H]dFBr bound). In the presence of Carb, PCP at high concentrations reduced [3H]dFBr binding to the level seen in the presence of α-BgTx. The concentration dependence of inhibition (IC50 = ∼1 µM) was consistent with PCP’s affinity for the ion channel binding site (Oswald et al., 1983). Nonradioactive dFBr also inhibited [3H]dFBr binding in the presence of Carb, but the concentration dependence was not consistent with a simple, single-site model. The inhibition was consistent with a two-site model: (1) a high-affinity component (IC50 = ∼6 µM) that reduced [3H]dFBr binding to the same extent as PCP, and (2) a low-affinity component that reduced [3H]dFBr binding with the same concentration dependence as seen for dFBr inhibition in the presence of α-BgTx (IC50 = ∼400 µM). Tetracaine, which in the presence of α-BgTx binds in the nAChR ion channel with high affinity (Keq = 0.5 µM) (Middleton et al., 1999), only inhibited [3H]dFBr binding at concentrations >100 µM. These results indicate that the high-affinity component of [3H]dFBr binding in the desensitized state results from [3H]dFBr binding in the ion channel, and dFBr inhibition of [3H]PCP binding establishes that dFBr binds in the channel with ∼10-fold higher affinity in the desensitized state (IC50 = ∼4 µM) than in the resting state. The low potency of tetracaine as an inhibitor of [3H]dFBr binding in the presence of α-BgTx indicates that this low-affinity component of binding is unlikely to be in the ion channel.

[3H]dFBr Photolabeling of Torpedo nAChR.

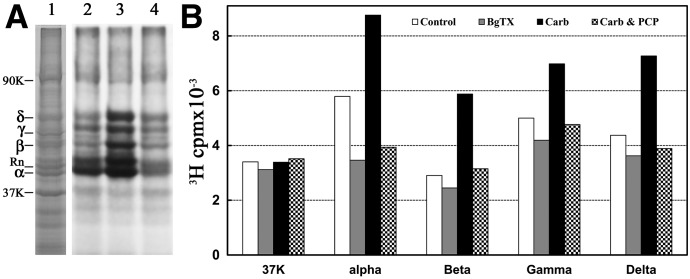

Covalent incorporation into Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes was determined by SDS-PAGE after membrane suspensions equilibrated with 0.5 µM [3H]dFBr were irradiated at 312 nm for 5 minutes (Fig. 5). Based on fluorography (Fig. 5A) and liquid scintillation counting of excised gel bands (Fig. 5B), [3H]dFBr was incorporated into each nAChR subunit. Carb enhanced 3H incorporation in each subunit (α/β/γ/δ, ∼25/100/40/60%). α-BgTx reduced 3H incorporation into the α subunit by 40% but by <15% in the β, γ, and δ subunits. The Carb-enhanced photolabeling within the nAChR subunits was inhibitable by PCP.

Fig. 5.

Photoincorporation of [3H]dFBr into Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes. Membranes were photolabeled on an analytical scale with 0.5 µM [3H]dFBr in the absence and presence of nAChR ligands. Polypeptides were resolved by SDS-PAGE on duplicate gels that were stained with Coomassie blue (A, lane 1). One gel was prepared for fluorography (A, lanes 2–4), and polypeptide bands were excised from the second gel for 3H determination by liquid scintillation counting (B). Drug additions for the fluorograph in (A): lane 2, no other ligand added; lane 3, +1 mM Carb; lane 4, +1 mM Carb and 100 µM PCP. The electrophoretic mobilities of the nAChR α, β, γ, and δ subunits, rapsyn (Rn), the Na+/K+-ATPase α subunit (90K) and calectrin (37K) are indicated on the left.

State-Dependent [3H]dFBr Photolabeling in the nAChR Ion Channel.

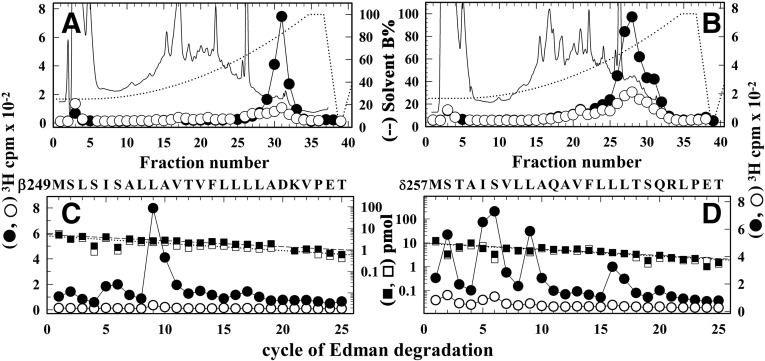

The effects of Carb and PCP on [3H]dFBr photoincorporation into the nAChR subunits and the results of the competition radioligand binding assays indicated the presence of a state-dependent, high-affinity dFBr binding site within the nAChR ion channel. To identify amino acid residues photolabeled by [3H]dFBr within the M2 helices that line the lumen of the ion channel, subunit fragments beginning at the N-termini of βM2 (βMet249) and δM2 (δMet257) were isolated from trypsin and EndoLys-C digests of [3H]dFBr-photolabeled β and δ subunits by Tricine SDS-PAGE (data not shown) followed by rpHPLC (Fig. 6, A and B). Upon N-terminal sequencing of the fragment beginning at βMet249 (Fig. 6C), there was a single major peak of Carb-enhanced 3H release in cycle 9, consistent with [3H]dFBr photolabeling of βLeu257 (βM2-9′; −Carb/+Carb, 2/50 cpm/pmol). For the fragment beginning at δMet257, there were peaks of 3H release in cycles 2, 5, 6, 9, and 16, indicating [3H]dFBr photolabeling of amino acids that line the ion channel: δSer258 (δM2-2′), δIle261 (δM2-5′), δSer262 (δM2-6′), δLeu265 (δM2-9′), and δLeu272 (δM2-16′). The efficiency of photolabeling of these amino acids was enhanced by ∼10-fold in the presence of Carb.

Fig. 6.

Agonist-enhanced [3H]dFBr photolabeling in βM2, and δM2. Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes were photolabeled at preparative scale with 0.5 µM [3H]dFBr in the absence (○, ⬜) or presence (⬤, ▪) of 1 mM Carb. (A and B) Elution of peptides (solid line) and 3H (○, ⬤) during rpHPLC purifications of an ∼8 kDa β subunit fragment isolated by from a trypsin digest (A) and an ∼14 kDa δ subunit fragment isolated from an EndoLys-C digest (B). (C and D) 3H (○, ⬤) and phenylthiohydantoin amino acids (⬜, ▪) released during sequence analyses of rpHPLC fractions 30 to 31 from (A) and fractions 27–29 from (B), respectively. (C) The only sequence detected began at the N-terminus of βM2 (βMet249; 5 pmol each condition), and the major peak of 3H release in cycle 9 indicates photolabeling of βLeu257 (βM2-9; −Carb/+Carb, 2/50 cpm/pmol). (D) The only sequence detected began at the N-terminus of δM2 (δMet257; 10 pmol each condition). The peaks of 3H release in cycles 2, 5, 6, 9, and 16 indicate photolabeling (−Carb/+Carb, in cpm/pmol) at δSer258 (δM2-2; 1/7), δIle261 (δM2-5; 1/14), δSer262 (δM2-6; 2/17), δLeu265 (δM2-9; 0.5/14), and δLeu272 (δM2-16; 1/12).

[3H]dFBr Photolabeling within the nAChR α Subunit: Ion Channel and ACh Binding Site.

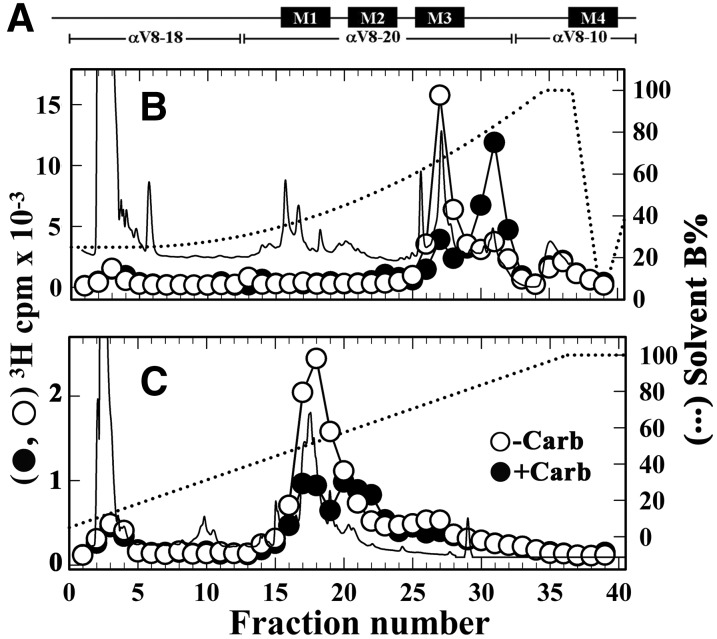

Similar to the other nAChR subunits, the Carb-enhanced photolabeling within the α subunit was inhibitable by PCP (Fig. 5), suggesting [3H]dFBr photolabeling within αM2. In contrast to the other nAChR subunits, in the resting state α-BgTx reduced α subunit photolabeling by ∼40%, suggesting potential [3H]dFBr photolabeling within the ACh binding site. Photolabeling within αM2 and in ACh binding site segments A (αTyr93) and C (αTyr190/αTyr197) can be readily determined by generating large α subunit fragments by limited in-gel digestion with endoproteinase Glu-C (V8 protease), followed by EndoLys-C digestion of those fragments and rpHPLC fractionation of the digests (see Materials and Methods). Limited digestion with V8 protease produces large subunit fragments (Fig. 7A): αV8-18 that begins at αThr52 and contains ACh binding site Segments A and B; αV8-20 that begins at αSer173 and contains binding site Segment C and the M1-M3 helices; and αV8-10 that begins at αAsn339 and contains the M4 helix (Blanton and Cohen, 1994). Fragments beginning at αHis186, containing ACh binding site Segment C, and at αMet243, the N-terminus of αM2, can be isolated by rpHPLC from EndoLys-C digests of αV8-20 (Pratt et al., 2000), while the fragment beginning at αLys77, containing binding site Segment A, can be isolated from an EndoLys-C digest of αV8-18 (Ziebell et al., 2004).

Fig. 7.

Isolation of [3H]dFBr-photolabeled α subunit peptides. The band for nAChR α subunit from the photolabeling experiment described in Fig. 6 was excised and transferred to a 15% acrylamide mapping gel and subjected to in-gel digestion with V8 protease to produce large nAChR α subunit fragments shown schematically in (A). rpHPLC fractionations of EndoLys-C digests of (B) αV8-20, which begins at αSer173, and (C) αV8-18, which begins at αThr52. Elution of peptides (solid line) and 3H (○-Carb, ⬤+Carb) were monitored. rpHPLC fractions 27–29 and 30–32 from the V8-20 digest and fractions 17–19 from the V8-18 digest were pooled for sequence analysis (Fig. 8).

We found that the αV8-20 and αV8-18 fragments contained >75% and ∼10% of α subunit 3H, respectively. When EndoLys-C digests of αV8-20 were fractionated by rpHPLC (Fig. 7B), there was a Carb-inhibitable peak of 3H at ∼60% organic, the expected location of the αHis186 fragment. In the presence of Carb, the major peak of 3H was at ∼80% organic, the expected location of the αMet243 fragment. For the EndoLys-C digests of αV8-18 (Fig. 7C), there was a single Carb-inhibitable peak of 3H at ∼50% organic, the expected location of the αLys77 fragment.

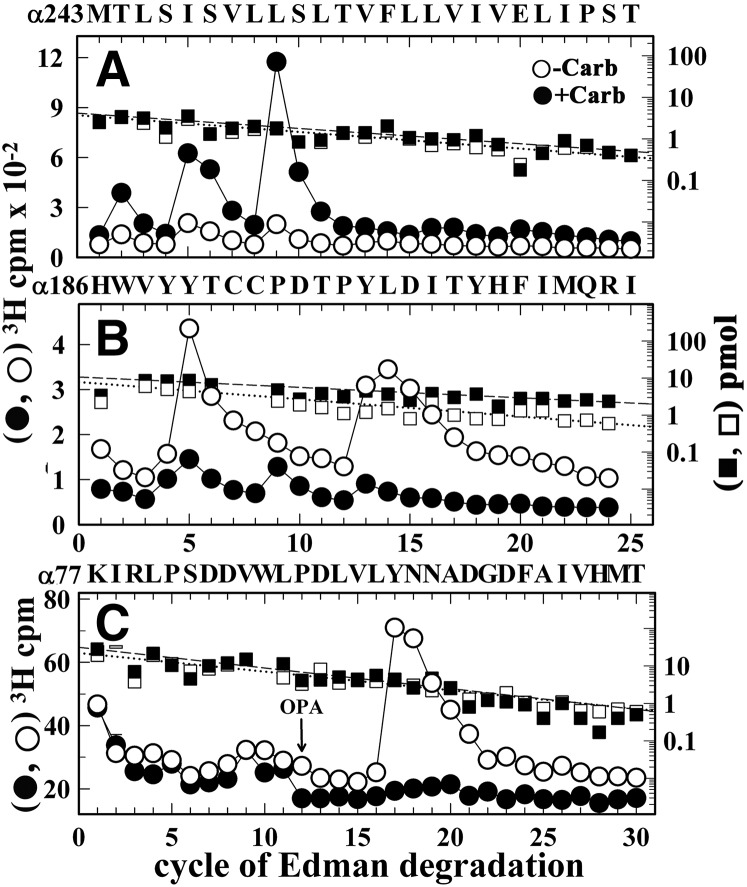

N-terminal amino acid sequencing of the hydrophobic 3H peak from the EndoLys-C digest of αV8-20 (Fig. 8A) established the presence of the αMet243 fragment, with peaks of 3H release at cycles 2, 5, 6, and 9 that indicated Carb-enhanced [3H]dFBr photolabeling of αThr244 (αM2-2′), αIle247 (αM2-5′), αSer248 (αM2-6′), and αIle251 (αM2-9′), amino acids that line the lumen of the ion channel. Sequence analyses of material in the hydrophilic peak of 3H from the EndoLys-C digest of αV8-20 (Fig. 8B) established the presence of the peptide beginning at αHis186 and peaks of 3H release at cycles 5 and 13 in the −Carb condition that identified [3H]dFBr photolabeling of the core aromatic amino acids in ACh binding site Segment C, αTyr190 and αTyr198. Carb inhibited photolabeling of those residues by >90%. Carb-inhibitable photolabeling of αTyr93, the core aromatic amino acid in ACh binding site Segment A, was established by sequence analysis of the material in the peak of 3H isolated by rpHPLC from the EndoLys-C digest of αV8-18 (Fig. 8C), with the Carb-inhibitable peak of 3H release in cycle 17 indicating photolabeling of αTyr93, the core aromatic amino acid in ACh binding site Segment A.

Fig. 8.

[3H]dFBr photolabeling within α subunit. 3H (○, ⬤) and phenylthiohydantoin amino acids (⬜, ▪) released during sequence analyses of rpHPLC fractions 30–32 (A) and 27–29 (B) from the fractionation of Endolys-C digests of αV8-20 (Fig. 7B) and fractions 17–19 (C) from the purification of the Endolys-C digest of αV8-18 (Fig. 7C). (A) The primary sequence began at the N-terminus of αM2 (αMet243; 4 pmol each condition) with a contaminating peptide beginning at βM249 (∼0.5 pmol each condition). The peaks of Carb-enhanced 3H release in cycles 2, 5, and 9 indicate [3H]dFBr photolabeling −Carb/+Carb, in cpm/pmol) at αThr244 (αM2-2, 4/15), αIle247 (αM2-5, 11/36), αSer248 (αM2-6, 7/31), and αIle251 (αM2-9, 15/101). (B) The only sequence began at αHis186 (⬜−Carb/▪+Carb, 8/10 pmol), with Carb-inhibitable peaks of 3H release at cycles 5 and 13 indicating [3H]dFBr photolabeling at αTyr190 and αTyr198 (−Carb/+Carb, 12/1 and 19/2 cpm/pmol, respectively). (C) The pool of material in rpHPLC fractions 17–19 from Fig. 7C was sequenced with the sequencing filter treated before cycle 12 with o-phthalaldehyde (OPA), which prevents sequencing of peptides not containing a proline at that cycle (Middleton and Cohen, 1991). After OPA treatment, sequencing continued only for the fragment beginning at αLys77 (⬜-Carb/▪+Carb, 22/31 pmol) that contains αPro88 in cycle 12. The peak of 3H release in cycle 17 indicated [3H]dFBr photolabeling of αTyr93 (−Carb/+Carb, 3/0.1 cpm/pmol).

[3H]dFBr Photolabeling within the nAChR ECD in the Presence of Agonist.

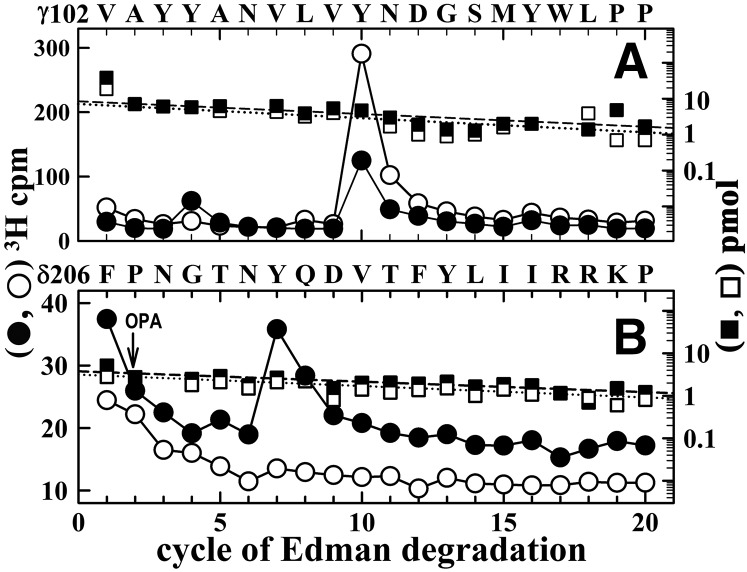

In a Torpedo nAChR photolabeling study with nonselective nAChR allosteric potentiators (Hamouda et al., 2013), [3H]galantamine and [3H]physostigmine were found to photolabel in the presence and absence of agonist γTyr105 and γTyr111 in ACh binding site Segment E at the canonical α-γ interface and δTyr212 at the noncanonical δ-β extracellular interface. To determine whether [3H]dFBr also photolabeled amino acids in binding site Segment E, the fragment beginning at γVal102 was isolated for sequence analysis from [3H]dFBr-photolabeled γ subunits by sequential proteolytic digests, Tricine SDS-PAGE, and rpHPLC (see Materials and Methods). During N-terminal sequencing of the γVal102 fragment isolated from nAChRs photolabeled in the absence of Carb, there was a peak of 3H release in cycle 10, consistent with [3H]dFBr photolabeling of γTyr111 at 18 cpm/pmol (Fig. 9A). This photolabeling was reduced by ∼60% in the presence of Carb. There was also a small peak of Carb-enhanced 3H release at cycle 4, indicating that [3H]dFBr also photolabeled γTyr105 (−Carb/+Carb, 0.2/1.4 cpm/pmol). We characterized [3H]dFBr photolabeling around δTyr212 by sequencing the δ subunit fragment beginning δPhe-206 (Fig. 9B). The Carb-enhanced peak of 3H release at cycle 7 indicated photolabeling of δTyr212 (−Carb/+Carb, 0.2/1.4 cpm/pmol). [3H]dFBr photolabeling of γTyr105, γTyr111, and δTyr212 and the effect of Carb on that photolabeling mirror those seen for [3H]physostigmine and [3H]galantamine, which suggests that dFBr binds at the physostigmine/galanthamine sites in the nAChR ECD at the canonical α-γ and noncanonical δ-β subunit interfaces.

Fig. 9.

[3H]dFBr photolabels γTyr105, γTyr111, and δTyr212 in the presence of agonist. 3H (○, ⬤) and phenylthiohydantoin amino acids (⬜, ▪) released during sequence analyses of a γ subunit fragment beginning at γVal102 (∼8 pmol each condition) (A) and a δ subunit fragment beginning at δPhe206 (∼4 pmol each condition) (B), each isolated as described in Materials and Methods from the nAChR photolabeling of Fig. 6 (−Carb (○, ⬜), +Carb (⬤, ▪)). (A) The major peak of 3H release at cycle 10 indicates [3H]dFBr photolabeling of γTyr111 (−Carb/+Carb, 18/6 cpm/pmol). The small peak of Carb-enhanced 3H release at cycle 4 indicates photolabeling of γTyr105 (−Carb/+Carb, 0.2/1.4 cpm/pmol). (B) During sequencing of the fragment beginning at δPhe206, recovered from rpHPLC fractions 23–25 in Fig. 6B, the peak of Carb-enhanced 3H release at cycle 7 indicates photolabeling of δTyr212 (-Carb/+Carb, 0.2/1.4 cpm/pmol). OPA, o-phthalaldehyde.

Discussion

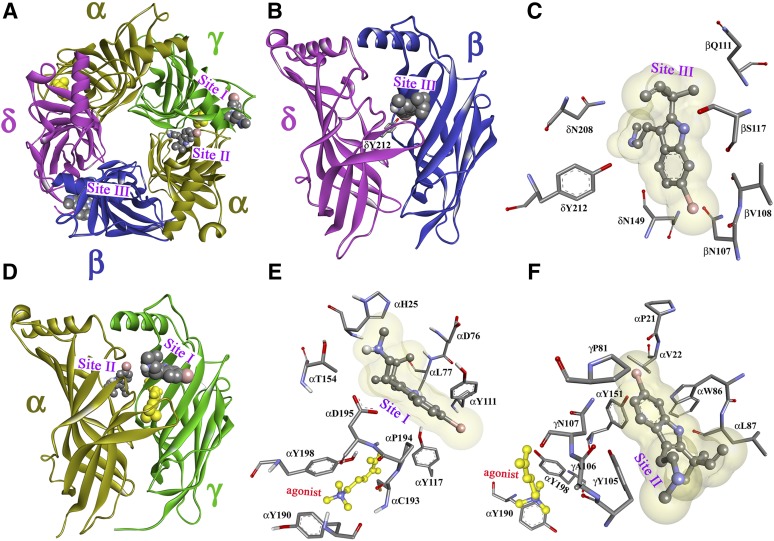

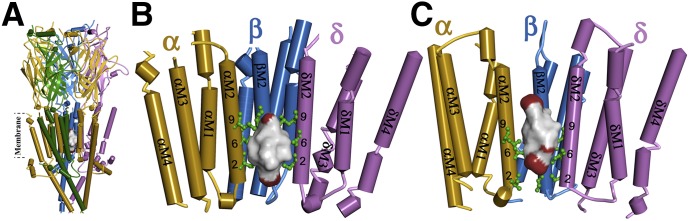

In addition to being a potent α4β2 nAChR PAM, the results presented here demonstrate that dFBr is a potent inhibitor of muscle-type nAChRs and that its intrinsic photoreactivity makes it well suited to identify the amino acids contributing to its binding sites in nAChRs by photoaffinity labeling. dayFBr is equipotent as an inhibitor (IC50 = ∼1µM) of adult human and Torpedo muscle-type nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. For the Torpedo nAChR, equilibrium radioligand binding assays established that dFBr binds with 10-fold higher affinity in the ion channel in the desensitized state (IC50 = ∼4 µM) than in the closed-channel state and that it binds only weakly (IC50 = ∼1 mM) to the ACh binding sites. Photoaffinity labeling of the Torpedo nAChR with [3H]dFBr allowed the identification of amino acids contributing to the high-affinity binding site in the ion channel and to three classes of binding sites in the nAChR ECD. The locations of the photolabeled amino acids in the ion channel and in the ECD are shown in nAChR homology models in Figs. 10 and 11, along with the orientations of dFBr in these sites predicted by computational docking.

Fig. 10.

dFBr binding site in the Torpedo muscle-type nAChR ion channel. (A and B) Side view (A) and view from within the ion channel toward the α-β-δ subunits (B) of a nAChR homology model based on the X-ray structure of the mouse serotonin 5-HT3R (PDB ID 4PIR) (Hassaine et al., 2014) and (C) a homology model based on the cryo-electron microscopy structure of Torpedo marmorata nAChR (PDB ID 2BG9) (Unwin, 2005). The nAChR α, β, γ, and δ subunits are colored in gold, blue, green, and violet, respectively. Amino acids photolabeled by [3H]dFBr within the α/β/δM2 helices are colored in green and identified by their position numbers from the N-terminus of the M2 helices. In each model, the ensemble of the 100 lowest energy dFBr docking solutions within the channel is shown as a Connolly surface representation colored by atom (C, black; H, white; Br, red), defining volumes of 905 Å3 (B) and 821 Å3 (C) compared with the dFBr molecular volume of 241 Å3.

Fig. 11.

dFBr binding sites in the Torpedo nAChR ECD. Views of the homology model, the Torpedo nAChR ECD based on the x-ray structure of the L-AChBP in the presence of Carb (PDB ID 1UV6) (Celie et al., 2004) with the α, β, γ, and δ subunits colored in gold, blue, green, and violet, respectively. A view from the top (A) and side views from the exterior (B and D) are shown with dFBr, in space-filling representation, docked at three distinct sites in the presence of the agonist Carb (yellow). Sites I and II are at the agonist-binding canonical interface near entry to the ACh binding site (Site I; A, D, and E) and in the vestibule of the ion channel (Site II; A, D, and F). Site III (A, B, and C) is at the δ-β subunit interface. Views from the exterior (C and E) and a view from the ion channel vestibule (F) showing dFBr docked in its predicted lowest energy orientations in Site I (E), Site II (F), and Site III (C).

dFBr Is a Broad-Spectrum Photoaffinity Probe.

While the photoreactive intermediates formed upon UV irradiation of dFBr are unknown, radical intermediates, based on the diversity of identified photolabeled amino acids (Ser, Leu, and Ile residues in the channel; Tyr in the ECD), are likely. Photolytic cleavage of the C–Br bond to form a reactive radical is one likely mechanism, based on the known susceptibility of haloindoles to photodehalogenation (Yang et al., 1989).

dFBr Binding in the Ion Channel.

The photolabeling of the amino acids at M2-2′,-5′,-6′, and -9′ in the nAChR α, β, and δ subunits provides an experimental definition of the high-affinity dFBr binding site in the ion channel in the desensitized state. This site, near the cytoplasmic end of the channel, extends over two helical turns (∼10 Å), a distance similar to the length of dFBr in an extended conformation (9.1 Å from the allyl group to the Br). This site, first identified by photoaffinity labeling with [3H]chlorpromazine (Giraudat et al., 1986), is the binding site in the channel for many other cationic and uncharged channel blockers. The [3H]dFBr photolabeling of δM-16′ and 20′ suggests an alternative mode of binding near the extracellular end of the ion channel, as has been found for [3H]chlorpromazine (Chiara et al., 2009a). Strikingly, neither [3H]dFBr nor [3H]chlorpromazine photolabeled the valines at position M2-13′, which contribute to the binding site for resting state-selective channel blockers including 3-(trifluoromethyl)-3-(m-[125I]iodophenyl)diazirine, [3H]tetracaine, and [3H]AziPm, a photoreactive propofol analog (White and Cohen, 1992; Gallagher and Cohen, 1999; Jayakar et al., 2013). Because the photoreactive intermediates formed upon irradiation of dFBr react readily with aliphatic side chains, the lack of photolabeling of M2-13′ indicates that dFBr does not bind at this level in the ion channel.

For the Torpedo nAChR homology model based on the 5-HT3R structure, dFBr docked within the ion channel in two distinct orientations with similar energies: (1) with the allyl group of dFBr at the level of M2-6′ and the 6-Br below the level of M2-2′, and (2) with the allyl group at the level of M2-4′ and the 6-Br at the level of M2-9′ (Fig. 10B). Similar docking clusters were seen for dFBr docked within the channel in the homology model based on the T. marmorata nAChR structure; however, for both clusters the allyl group was centered near M2-9′ with the Br either above M2-2′ or near M2-13′ (Fig. 10C).

dFBr Binding Sites in the nAChR ECD.

To visualize the locations of photolabeled amino acids in the ECD, we used a homology model derived from Carb-bound form of the L-AChBP (PDB ID 1UV6) (Celie et al., 2004). The amino acids photolabeled by [3H]dFBr in the presence of agonist identified three distinct sites (Fig. 11). Sites I and II are at the canonical α-γ subunit interface, with Site I (Fig. 11, A and D), near the entry to the transmitter binding site (Fig. 11E), and Site II, in the vestibule of the ion channel (Fig. 11F), identified by photolabeling of γTyr111 and γTyr105, respectively. Site III, identified by photolabeling of δTyr212, is at the noncanonical δ-β subunit interface (Fig. 11, B and C) and is equivalent to the benzodiazepine site in the GABAA receptor (Sigel and Buhr, 1997; Richter et al., 2012). dFBr affinity for these sites must be much lower than for the site in the ion channel, which was identified as the high-affinity component of [3H]dFBr binding. These three binding sites in the ECD are the same as those photolabeled by [3H]physostigmine and [3H]galantamine, low-efficacy Torpedo nAChR PAMs that did not bind with high-affinity, or photolabel amino acids in the ion channel (Hamouda et al., 2013).

Figure 11, C, E, and F depicts dFBr in ball-and-stick format in the lowest-energy orientations predicted by computational docking to these sites in a model containing Carb at the transmitter binding sites. In Site I dFBr is predicted to bind above the level of α subunit ACh binding site Loop C with the bromine carbon (C6) within 5 Å of γTyr111. In Site II dFBr is predicted to bind in the vestibule of the ion channel with C6 within 5 Å of the photolabeled γTyr105 and αTyr151, whose photolabeling was not characterized. In Site III at the δ-β subunit interface, dFBr is predicted to bind between δ subunit extracellular loop 10, homologous to ACh binding site Loop C in α subunit, and β strands 5 and 6 of the β subunit (Fig. 11, B and C). dFBr C6 is closest to δAsn152 and βAsn107 and within 7 Å of photolabeled δTyr212, which is homologous to αTyr198 in ACh binding site Loop C.

Differential Effects of dFBr at Muscle-Type and α4β2 nAChR: Relevance to PAM Binding Sites.

Our results establish that dFBr binds with high affinity to a site in the ion channel and with much lower affinity to multiple sites in the ECD. Equilibrium radioligand binding assays established that dFBr binds with higher affinity to the ion channel in the desensitized state than in the closed-channel state, and our electrophysiological assays using wild-type and mutant receptors indicate that dFBr interacts preferentially with the open-channel state compared with the closed-channel or equilibrium-desensitized state. Further studies using rapid perfusion techniques to measure responses at millisecond times will be necessary to determine whether dFBr inhibits nAChRs in the open-channel state without enhancing desensitization, as is seen for classic open-channel blockers. Presumably dFBr inhibits nAChR in the open state by binding in the ion channel; however, photoaffinity labeling studies using rapid mixing and freeze quench techniques will be necessary to determine whether the binding site in the open-channel state is the same as that seen in the desensitized state, as seen for a photoreactive etomidate analog (Chiara et al., 2009b), or whether there is preferential, transient binding to a nonchannel site (Arevalo et al., 2005; Yamodo et al., 2010).

While inhibition of muscle-type nAChR due to high-affinity binding in the ion channel precludes the ability to study the functional contribution of dFBr binding at the extracellular sites, dFBr binding to one or more of those sites in α4β2 nAChRs is likely to result in potentiation of ACh responses. Our results establish that dFBr can photoincorporate into a wide range of amino acid side chains; however, we did not find photolabeling of amino acids in the TMD that contribute to the known intersubunit or intrasubunit binding sites for Torpedo nAChR positive and negative allosteric modulators (Nirthanan et al., 2008; Hamouda et al., 2011, 2014; Jayakar et al., 2013). Mutational analyses provide evidence for PAM binding sites in the ECD at noncanonical interfaces analogous to dFBr Site III in α3β2 nAChRs at the β2/α3 interface (Seo et al., 2009) and in α4β2 nAChRs at the α4/α4 interface, which is also an ACh binding site (Mazzaferro et al., 2014; Olsen et al., 2014). Mutational analyses and computational docking also provide evidence for negative allosteric modulator binding sites equivalent to dFBr Site I at the canonical interfaces in α4β2 and α3β4 nAChRs (Grishin et al., 2010; Henderson et al., 2012). Based on our results, [3H]dFBr should serve as an appropriate photoreactive PAM to identify its binding sites in α4β2 nAChRs and to identify other allosteric modulators that competitively inhibit photolabeling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. David Chiara for construction of the nAChR homology model based on the 5-HT3R structure PDB ID 4PIR and for useful comments about the manuscript and Dr. Hamed I. Ali (Texas A&M Health Sciences Center) for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- α-BgTx

α-bungarotoxin

- Carb

carbamylcholine chloride

- dFBr

desformylflustrabromine

- ECD

extracellular domain

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- PCP

phencyclidine hydrochloride

- rpHPLC

reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- TMD

transmembrane domain

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Hamouda, Wang, Stewart, Cohen.

Conducted experiments: Hamouda, Wang.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Jain, Glennon.

Performed data analysis: Hamouda, Cohen.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Hamouda, Cohen.

Footnotes

>This research was supported in part by the Edward and Anne Lefler Center of Harvard Medical School; the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant GM-58448] (J.B.C.); the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke [Grant NS-066059] (R.A.G.); and the Faculty Development Fund of Texas A&M Health Sciences Center (A.K.H.).

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Arevalo E, Chiara DC, Forman SA, Cohen JB, Miller KW. (2005) Gating-enhanced accessibility of hydrophobic sites within the transmembrane region of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor’s δ-subunit. A time-resolved photolabeling study. J Biol Chem 280:13631–13640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR. (2010) Positive and negative modulation of nicotinic receptors. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 80:153–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D, Bertrand S, Cassar S, Gubbins E, Li J, Gopalakrishnan M. (2008) Positive allosteric modulation of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: ligand interactions with distinct binding sites and evidence for a prominent role of the M2-M3 segment. Mol Pharmacol 74:1407–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D, Gopalakrishnan M. (2007) Allosteric modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 74:1155–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton MP, Cohen JB. (1994) Identifying the lipid-protein interface of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: secondary structure implications. Biochemistry 33:2859–2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celie PHN, van Rossum-Fikkert SE, van Dijk WJ, Brejc K, Smit AB, Sixma TK. (2004) Nicotine and carbamylcholine binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as studied in AChBP crystal structures. Neuron 41:907–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux JP, Taly A. (2008) Nicotinic receptors, allosteric proteins and medicine. Trends Mol Med 14:93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Dangott LJ, Eckenhoff RG, Cohen JB. (2003) Identification of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor amino acids photolabeled by the volatile anesthetic halothane. Biochemistry 42:13457–13467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Gill JF, Chen Q, Tillman T, Dailey WP, Eckenhoff RG, Xu Y, Tang P, Cohen JB. (2014) Photoaffinity labeling the propofol binding site in GLIC. Biochemistry 53:135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Hamouda AK, Ziebell MR, Mejia LA, Garcia G, 3rd, Cohen JB. (2009a) [3H]chlorpromazine photolabeling of the torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor identifies two state-dependent binding sites in the ion channel. Biochemistry 48:10066–10077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Hong FH, Arevalo E, Husain SS, Miller KW, Forman SA, Cohen JB. (2009b) Time-resolved photolabeling of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by [3H]azietomidate, an open-state inhibitor. Mol Pharmacol 75:1084–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corringer PJ, Poitevin F, Prevost MS, Sauguet L, Delarue M, Changeux JP. (2012) Structure and pharmacology of pentameric receptor channels: from bacteria to brain. Structure 20:941–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- daCosta CJB, Free CR, Corradi J, Bouzat C, Sine SM. (2011) Single-channel and structural foundations of neuronal α7 acetylcholine receptor potentiation. J Neurosci 31:13870–13879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Bertrand D. (2007) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47:699–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faghih R, Gopalakrishnan M, Briggs CA. (2008) Allosteric modulators of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Med Chem 51:701–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filatov GN, White MM. (1995) The role of conserved leucines in the M2 domain of the acetylcholine receptor in channel gating. Mol Pharmacol 48:379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MJ, Cohen JB. (1999) Identification of amino acids of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor contributing to the binding site for the noncompetitive antagonist [3H]tetracaine. Mol Pharmacol 56:300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G, 3rd, Chiara DC, Nirthanan S, Hamouda AK, Stewart DS, Cohen JB. (2007) [3H]Benzophenone photolabeling identifies state-dependent changes in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor structure. Biochemistry 46:10296–10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German N, Kim JS, Jain A, Dukat M, Pandya A, Ma Y, Weltzin M, Schulte MK, Glennon RA. (2011) Deconstruction of the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor positive allosteric modulator desformylflustrabromine. J Med Chem 54:7259–7267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudat J, Dennis M, Heidmann T, Chang JY, Changeux JP. (1986) Structure of the high-affinity binding site for noncompetitive blockers of the acetylcholine receptor: serine-262 of the δ subunit is labeled by [3H]chlorpromazine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83:2719–2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Clementi F. (2004) Neuronal nicotinic receptors: from structure to pathology. Prog Neurobiol 74:363–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Clementi F, Fornari A, Gaimarri A, Guiducci S, Manfredi I, Moretti M, Pedrazzi P, Pucci L, Zoli M. (2009) Structural and functional diversity of native brain neuronal nicotinic receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 78:703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishin AA, Wang CIA, Muttenthaler M, Alewood PF, Lewis RJ, Adams DJ. (2010) α-conotoxin AuIB isomers exhibit distinct inhibitory mechanisms and differential sensitivity to stoichiometry of α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem 285:22254–22263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Kimm T, Cohen JB. (2013) Physostigmine and galanthamine bind in the presence of agonist at the canonical and noncanonical subunit interfaces of a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Neurosci 33:485–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Stewart DS, Chiara DC, Savechenkov PY, Bruzik KS, Cohen JB. (2014) Identifying barbiturate binding sites in a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with [3H]allyl m-trifluoromethyldiazirine mephobarbital, a photoreactive barbiturate. Mol Pharmacol 85:735–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Stewart DS, Husain SS, Cohen JB. (2011) Multiple transmembrane binding sites for p-trifluoromethyldiazirinyl-etomidate, a photoreactive Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor allosteric inhibitor. J Biol Chem 286:20466–20477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassaine G, Deluz C, Grasso L, Wyss R, Tol MB, Hovius R, Graff A, Stahlberg H, Tomizaki T, Desmyter A, et al. (2014) X-ray structure of the mouse serotonin 5-HT3 receptor. Nature 512:276–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson BJ, González-Cestari TF, Yi B, Pavlovicz RE, Boyd RT, Li C, Bergmeier SC, McKay DB. (2012) Defining the putative inhibitory site for a selective negative allosteric modulator of human α4β2 neuronal nicotinic receptors. ACS Chem Neurosci 3:682–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs RE, Gouaux E. (2011) Principles of activation and permeation in an anion-selective Cys-loop receptor. Nature 474:54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayakar SS, Dailey WP, Eckenhoff RG, Cohen JB. (2013) Identification of propofol binding sites in a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with a photoreactive propofol analog. J Biol Chem 288:6178–6189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AA, Frølund B, Liljefors T, Krogsgaard-Larsen P. (2005) Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: structural revelations, target identifications, and therapeutic inspirations. J Med Chem 48:4705–4745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Padnya A, Weltzin M, Edmonds BW, Schulte MK, Glennon RA. (2007) Synthesis of desformylflustrabromine and its evaluation as an α4β2 and α7 nACh receptor modulator. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 17:4855–4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarca C, Nowak MW, Zhang H, Tang L, Deshpande P, Lester HA. (1995) Channel gating governed symmetrically by conserved leucine residues in the M2 domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature 376:514–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. (2013) Positive allosteric modulation of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as a new approach to smoking reduction: evidence from a rat model of nicotine self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 230:203–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J, Höffle-Maas A, Samochocki M, Luttmann E, Albuquerque EX, Fels G, Maelicke A. (2010) Localization by site-directed mutagenesis of a galantamine binding site on α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor extracellular domain. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 30:469–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaferro S, Gasparri F, New K, Alcaino C, Faundez M, Iturriaga Vasquez P, Vijayan R, Biggin PC, Bermudez I. (2014) Non-equivalent ligand selectivity of agonist sites in (α4β2)2α4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: a key determinant of agonist efficacy. J Biol Chem 289:21795–21806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton RE, Cohen JB. (1991) Mapping of the acetylcholine binding site of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: [3H]nicotine as an agonist photoaffinity label. Biochemistry 30:6987–6997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton RE, Strnad NP, Cohen JB. (1999) Photoaffinity labeling the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with [3H]tetracaine, a nondesensitizing noncompetitive antagonist. Mol Pharmacol 56:290–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PS, Aricescu AR. (2014) Crystal structure of a human GABAA receptor. Nature 512:270–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnatsakanyan N, Jansen M. (2013) Experimental determination of the vertical alignment between the second and third transmembrane segments of muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurochem 125:843–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirthanan S, Garcia G, 3rd, Chiara DC, Husain SS, Cohen JB. (2008) Identification of binding sites in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor for TDBzl-etomidate, a photoreactive positive allosteric effector. J Biol Chem 283:22051–22062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JA, Ahring PK, Kastrup JS, Gajhede M, Balle T. (2014) Structural and functional studies of the modulator NS9283 reveal agonist-like mechanism of action at α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem 289:24911–24921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald RE, Heidmann T, Changeux J-P. (1983) Multiple affinity states for noncompetitive blockers revealed by [3H]phencyclidine binding to acetylcholine receptor rich membrane fragments from Torpedo marmorata. Biochemistry 22:3128–3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya A, Yakel JL. (2011) Allosteric modulator Desformylflustrabromine relieves the inhibition of α2β2 and α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by β-amyloid(1-42) peptide. J Mol Neurosci 45:42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters L, König GM, Terlau H, Wright AD. (2002) Four new bromotryptamine derivatives from the marine bryozoan Flustra foliacea. J Nat Prod 65:1633–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MB, Husain SS, Miller KW, Cohen JB. (2000) Identification of sites of incorporation in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor of a photoactivatible general anesthetic. J Biol Chem 275:29441–29451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter L, de Graaf C, Sieghart W, Varagic Z, Mörzinger M, de Esch IJ, Ecker GF, Ernst M. (2012) Diazepam-bound GABAA receptor models identify new benzodiazepine binding-site ligands. Nat Chem Biol 8:455–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala F, Mulet J, Reddy KP, Bernal JA, Wikman P, Valor LM, Peters L, König GM, Criado M, Sala S. (2005) Potentiation of human α4β2 neuronal nicotinic receptors by a Flustra foliacea metabolite. Neurosci Lett 373:144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger H, von Jagow G. (1987) Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem 166:368–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S, Henry JT, Lewis AH, Wang N, Levandoski MM. (2009) The positive allosteric modulator morantel binds at noncanonical subunit interfaces of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 29:8734–8742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel E, Buhr A. (1997) The benzodiazepine binding site of GABAA receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 18:425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taly A, Corringer PJ, Guedin D, Lestage P, Changeux JP. (2009) Nicotinic receptors: allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8:733–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N. (2005) Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4A resolution. J Mol Biol 346:967–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White BH, Cohen JB. (1988) Photolabeling of membrane-bound Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with the hydrophobic probe 3-trifluoromethyl-3-(m-[125I]iodophenyl)diazirine. Biochemistry 27:8741–8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White BH, Cohen JB. (1992) Agonist-induced changes in the structure of the acetylcholine receptor M2 regions revealed by photoincorporation of an uncharged nicotinic noncompetitive antagonist. J Biol Chem 267:15770–15783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DK, Wang J, Papke RL. (2011) Positive allosteric modulators as an approach to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-targeted therapeutics: advantages and limitations. Biochem Pharmacol 82:915–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamodo IH, Chiara DC, Cohen JB, Miller KW. (2010) Conformational changes in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor during gating and desensitization. Biochemistry 49:156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang NCC, Huang A, Yang DDH. (1989) Photodehalogenation of 4-haloindoles. J Am Chem Soc 111:8060–8061. [Google Scholar]

- Young GT, Zwart R, Walker AS, Sher E, Millar NS. (2008) Potentiation of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors via an allosteric transmembrane site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:14686–14691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebell MR, Nirthanan S, Husain SS, Miller KW, Cohen JB. (2004) Identification of binding sites in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor for [3H]azietomidate, a photoactivatable general anesthetic. J Biol Chem 279:17640–17649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.