Abstract

The epidemiology of carbapenemases worldwide is showing that OXA-48 variants are becoming the predominant carbapenemase type in Enterobacteriaceae in many countries. However, not all OXA-48 variants possess significant activity toward carbapenems (e.g., OXA-163). Two Serratia marcescens isolates with resistance either to carbapenems or to extended-spectrum cephalosporins were successively recovered from the same patient. A genomic comparison using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and automated Rep-PCR typing identified a 97.8% similarity between the two isolates. Both strains were resistant to penicillins and first-generation cephalosporins. The first isolate was susceptible to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, was resistant to carbapenems, and had a significant carbapenemase activity (positive Carba NP test) related to the expression of OXA-48. The second isolate was resistant to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, was susceptible to carbapenems, and did not express a significant imipenemase activity, (negative for the Carba NP test) despite possessing a blaOXA-48-type gene. Sequencing identified a novel OXA-48-type β-lactamase, OXA-405, with a four-amino-acid deletion compared to OXA-48. The blaOXA-405 gene was located on a ca. 46-kb plasmid identical to the prototype IncL/M blaOXA-48-carrying plasmid except for a ca. 16.4-kb deletion in the tra operon, leading to the suppression of self-conjugation properties. Biochemical analysis showed that OXA-405 has clavulanic acid-inhibited activity toward expanded-spectrum activity without significant imipenemase activity. This is the first identification of a successive switch of catalytic activity in OXA-48-like β-lactamases, suggesting their plasticity. Therefore, this report suggests that the first-line screening of carbapenemase producers in Enterobacteriaceae may be based on the biochemical detection of carbapenemase activity in clinical settings.

INTRODUCTION

Ambler class D β-lactamases (oxacillinases) are widely disseminated among clinically relevant Gram-negative bacteria (1). They exhibit a high degree of diversity of hydrolysis activity ranging from narrow to broad-spectrum hydrolysis activity toward β-lactams (1). Among the class D β-lactamases, several enzymes hydrolyze carbapenems. Most carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases (CHDLs) are from Acinetobacter spp. (e.g., OXA-23, OXA-40, OXA-58, OXA-143) (2, 3), whereas OXA-48-type enzymes are identified in Enterobacteriaceae only (4). The OXA-48-derived CHDLs have initially been identified in Turkey (5), first in Klebsiella pneumoniae and then in other enterobacterial species (4). The known OXA-48 variants are currently as follows: (i) OXA-162, identified from K. pneumoniae isolates in Turkey (6); (ii) OXA-163, identified from K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae isolates in Argentina (7, 8); (iii) OXA-181, identified from a K. pneumoniae isolate in India (9); (iv) OXA-204, identified from K. pneumoniae isolates in patients having a link with North Africa (10); (v) OXA-232, identified in France from a K. pneumoniae isolate recovered from a patient who had been transferred from India to Mauritius (11); (vi) OXA-244 and OXA-245, from K. pneumoniae isolates collected in Spain (12); (vii) OXA-247, identified from a K. pneumoniae isolate recovered in Argentina (13); and (viii) OXA-370, reported from an Enterobacter hormaechei isolate in Brazil (14). These variants differ from OXA-48 by one to five amino acid substitutions and/or by a four-amino-acid deletion which results in a modified β-lactam hydrolysis spectrum.

The epidemiology of carbapenemases worldwide shows that OXA-48 variants are becoming the predominant carbapenemase type in Enterobacteriaceae in many regions and countries, such as North Africa, Turkey, France, Germany, and the Middle East.

The aim of this study was to characterize the peculiar molecular mechanisms of resistance to β-lactams, involving a switch from a carbapenem resistance/expanded-spectrum cephalosporin susceptibility profile to a carbapenem susceptibility/expanded-spectrum cephalosporin resistance profile, among two successive Serratia marcescens isolates from the same patient.

(This work was presented in part at the 54th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 5 to 9 September 2014, Washington, DC.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Identification of clinical isolates was performed by using the API20E system (bioMérieux, La Balme-les-Grottes, France) and confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MALDI Biotyper CA system, Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA). Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen, Saint-Aubin, France) was used for cloning experiments, and azide-resistant E. coli J53 was used for conjugation assays.

Susceptibility testing.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities were determined by the disk diffusion technique on Mueller-Hinton agar (Bio-Rad, Marnes-La-Coquette, France) and interpreted according to the EUCAST breakpoints, updated in 2014 (http://www.eucast.org). MICs were determined using the Etest technique (bioMérieux).

Detection of carbapenemase activity.

The carbapenemase activity was searched for using two techniques: the updated Carba NP test (15) and UV spectrophotometry (16). The updated Carba NP test, which detects imipenemase activity, was performed after plating the culture on a Trypticase soy agar medium supplemented with ZnSO4, as previously described (17). The UV spectrophotometry technique used has been detailed elsewhere (16).

PCR, cloning experiments, and DNA sequencing.

Whole-cell DNAs of the two S. marcescens isolates and of OXA-48-producing and OXA-163-producing K. pneumoniae isolates (8) were extracted using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and were then used as a template to amplify the blaOXA-48-like genes. The PCR, using the primers preOXA-48A (5′-TATATTGCATTAAGCAAGGG-3′) and preOXA-48B (5′-CACACAAATACGCGCTAACC-3′), was able to amplify blaOXA-48,blaOXA-163, and blaOXA-405 genes. The amplicons obtained were then cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-Topo plasmid (Invitrogen) downstream from the pLac promoter, in the same orientation. The recombinant pTOPO-OXA plasmids were electroporated into the E. coli TOP10 strain. Plasmid DNAs extraction was performed using the Qiagen miniprep kit. Both strands of the inserts of the recombinant plasmids were sequenced using a T7 promoter and M13 reverse primers with an automated sequencer (ABI Prism 3100; Applied Biosystems). The nucleotide sequences were analyzed using software available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Plasmid characterization and mating-out assay.

Plasmid DNAs of both clinical S. marcescens isolates and OXA-163-producing K. pneumoniae 6299 were extracted using the Kieser method (18). Plasmids of ca. 154, 66, 48, and 7 kb of Escherichia coli NCTC 5019 were used as plasmid size markers. Plasmid DNA was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Transfer of the β-lactam resistance markers was attempted by liquid mating-out assays at 37°C using E. coli J53 as the recipient strain and by electroporation of the plasmid DNA suspension of clinical isolates into E. coli TOP10. Selection of transconjugants was performed on agar-supplemented plates with ticarcillin (100 mg/liter) and with azide (100 mg/liter). Plasmids were typed using the PCR-based replicon typing (PBRT) scheme, as described previously (19), and using the specific primers RepA-A (5′-GACATTGAGTCAGTAGAAGG-3′) and RepA-B(5′-CGTGCAGTTCGTCTTTCGGC-3′) designed for the detection of the IncL/M OXA-48 plasmid replicase (20).

The blaOXA-405-carrying plasmid was characterized by PCR mapping followed by DNA sequencing. Fourteen primer pairs were used for the mapping of the 61,881-bp IncL/M plasmid carrying the blaOXA-48 gene (Table 1). The blaOXA-48-carrying plasmid sequence (GenBank accession number JN626286) was used as a positive control for PCR mapping (20).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for mapping of plasmids carrying blaOXA-48-type genes

| Primer name | Nucleotide data according to GenBank accession no. JN626286 |

Location | Amplicon size (bp) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | Stop | 5′ to 3′ sequence | |||

| C1F | 57425 | 57444 | ATCCGGTCCCCCTGATTATC | IncL/M replicase | 4531 |

| C1R | 55 | 74 | GTCTGCGACTGACAGACGAT | trbA | |

| C2F | 1208 | 1227 | CGAAAGCCAAACCACATCAC | trbA | 4469 |

| OXA-48-3′external | 5655 | 5676 | TATTGTCAAACAAGCCATGCTG | blaOXA-48 | |

| OXA-48-5′external | 6099 | 6119 | ATTCCAGAGCACAACTACGCC | blaOXA-48 | 3025 |

| C3R | 9104 | 9123 | CCGTCGTTGTTGCTGAGAAC | mucB | |

| C4F | 10248 | 10267 | CGCAGTGGAAGGATATTCCC | mucB | 4077 |

| C4R | 15005 | 15024 | TTCAGGGCGCTGGATTCAAG | orf12 | |

| C5F | 15480 | 15499 | GCGTGACCGCCTCAAATTCT | orf12 | 4207 |

| C5R | 19667 | 19686 | CGAGCACTTACGGTTATCAG | parB | |

| C6F | 20083 | 20102 | CATCTGTTCCCGGATGATGA | parB | 3892 |

| C6R | 23955 | 23974 | TCTATGCCGCCCTGTATTCC | orf25 | |

| C7F | 25154 | 25173 | CAGTGAAGGACTGAGCCACT | orf25 | 4240 |

| C7R | 29374 | 29393 | GGCGGGTTGATTCAGTTCAG | klcA | |

| C8F | 29786 | 29805 | GATTTACCGCGCGATTGACT | klcA | 3757 |

| C8R | 33523 | 33542 | GACTTTTTGTCCCTTCGGCC | mobA | |

| C9F | 35370 | 35389 | GCAGGCGTATGCTCAAAACG | mobA | 2913 |

| C9R | 38263 | 38282 | ACGTTGGCGATCGTCAAAGG | pri | |

| C10F | 41356 | 41375 | CAGCCTCAGCATTTACAAGC | pri | 4613 |

| C10R | 45949 | 45968 | TCAGCAGGCTTAGCAGACAC | traP | |

| C11F | 46577 | 46596 | CAAGTAAAGGCCTTATCCGC | traP | 4597 |

| C11R | 51154 | 51173 | CTGACCGTTTTGCTTTTCCG | traW | |

| C12F | 52321 | 52340 | GAGTGTGAACGCGGGAGTAT | traW | 4144 |

| C12R | 56445 | 56464 | ATGAACTCCGGCGAAAGACC | IncL/M replicase | |

Hydrolysis analysis.

The specific activities of the β-lactamases OXA-48, OXA-163, and OXA-405 were determined using the supernatant of a whole-cell crude extract obtained from an overnight culture of E. coli clones expressing those β-lactamases (pTOPO-OXA-48, pTOPO-OXA-163, and pTOPO-OXA-405 in E. coli TOP 10) with the UV spectrophotometer Ultrospec 2000 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), as previously described (10).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the blaOXA-405 gene has been submitted to the EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the accession number KM589641.

RESULTS

Patient features and characteristics of the S. marcescens clinical isolates.

In January 2011, a 26-year-old woman was admitted at the emergency unit of the University Hospital of Besançon (eastern part of France) for an acute pulmonary infection. After 2 days of hospitalization, blood cultures and a tracheal aspirate identified S. marcescens isolates with identical antibiotic susceptibility profiles (these isolates were denoted Sm1). They were resistant to ticarcillin, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, piperacillin-tazobactam, and temocillin (MIC, >256 mg/liter), had decreased susceptibility to carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, and doripenem), and remained susceptible to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (Table 2). A positive Carba NP test indicated the expression of a carbapenemase, and PCR experiments were carried out on purified DNA of Sm1 with primers specific to common carbapenemase genes (blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaNDM, and blaOXA-48). A blaOXA-48-like gene was amplified and was later identified as blaOXA-48 according to sequencing results. The patient was successfully treated with cefepime and amikacin for 15 days. Furthermore, due to the irradiation of the nasopharynx for a carcinoma at the age of 14, the patient presented with important locoregional sequelae composed of sclerosis of the thorax and cervical regions and the persistence of a right laryngeal-cervical fistula. More than 18 months later (October 2012), another S. marcescens strain (Sm2) was isolated from a breast hematoma. This S. marcescens isolate was resistant to ticarcillin, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, and piperacillin-tazobactam, had a decreased susceptibility to ertapenem, but remained susceptible to the other tested carbapenem molecules (imipenem, meropenem, and doripenem). The Carba NP test did not reveal carbapenemase activity. Unlike isolate Sm1, isolate Sm2 was resistant to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime) and aztreonam (Table 2) and recovered susceptibility to temocillin (MIC, 8 mg/liter). PCR using whole-cell DNA of Sm2 as the template was positive for a blaOXA-48-like gene. Sequencing results identified a novel blaOXA-48-like gene, designated the blaOXA-405 gene.

TABLE 2.

MICs of β-lactams for S. marcescens OXA-48 (Sm1), S. marcescens OXA-405 (Sm2), E. coli pTOPO-OXA-48, E. coli pTOPO-OXA-405, E. coli pTOPO-OXA-163, and E. coli TOP10

| β-Lactams | MIC (mg/liter) of: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. marcescens OXA-48 (Sm1) | S. marcescens OXA-405 (Sm2) | E. coli TOP10 (pTOPO-OXA-48) | E. coli TOP10 (pTOPO-OXA-405) | E. coli TOP10 (pTOPO-OXA-163) | E. coli TOP10 | |

| Amoxicillin | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | 2 |

| Amoxicillin + CLAa | >256 | >256 | 192 | >256 | 96 | 2 |

| Piperacillin | >256 | >256 | 128 | >256 | >256 | 1.5 |

| Piperacillin + TZBb | 96 | >256 | 12 | 24 | 32 | 1 |

| Temocillin | >256 | 8 | >256 | 32 | 32 | 4 |

| Ticarcillin | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | 2 |

| Cefalotin | >256 | >256 | 8 | 32 | 64 | 2 |

| Cefepime | 0.25 | 3 | 0.032 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.023 |

| Cefepime + TZBb | 0.25 | 2 | 0.032 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.023 |

| Cefotaxime | 1.5 | 6 | 0.19 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.06 |

| Cefotaxime + TZBb | 1.5 | 4 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 1 | 0.06 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25 | 4 | 0.25 | 3 | 16 | 0.12 |

| Ceftazidime + TZBb | 0.25 | 2 | 0.25 | 1 | 3 | 0.12 |

| Imipenem | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.19 |

| Meropenem | 4 | 0.19 | 0.094 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.01 |

| Ertapenem | >32 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.06 |

| Doripenem | 3 | 0.125 | 0.064 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.023 |

| Aztreonam | 0.125 | 4 | 0.064 | 1 | 2 | 0.047 |

CLA, clavulanic acid at a fixed concentration of 4 mg/liter.

TZB, tazobactam at a fixed concentration of 4 mg/liter.

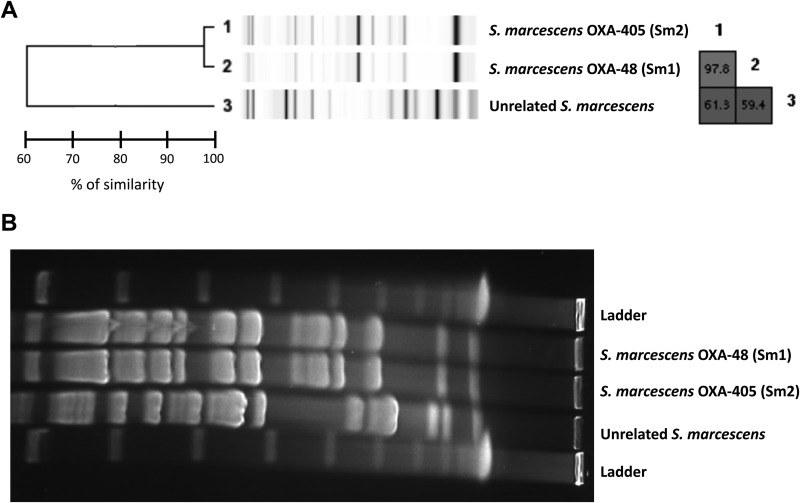

Genomic comparison using a Rep-PCR-based technique (DiversiLab, bioMérieux) identified a 97.8% genomic similarity between the S. marcescens Sm1 and Sm2 isolates (Fig. 1A). Therefore, these strains were considered to be clonally related. This clonality has been confirmed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

(A) Rep-PCR analysis using the Diversilab technique. Dendrogram and computer-generated image of Rep-PCR banding patterns of OXA-48-producing S. marcescens, OXA-405-producing S. marcescens, and an unrelated strain of S. marcescens. (B) Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of OXA-48-producing S. marcescens, OXA-405-producing S. marcescens, and an unrelated strain of S. marcescens.

Characterization of the β-lactamase OXA-405.

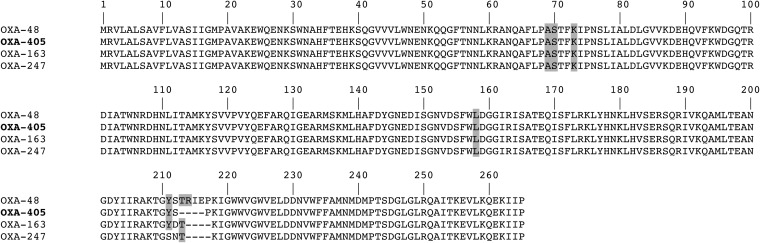

This blaOXA-405 gene differs from the blaOXA-48 gene by a 12-bp deletion leading to a four-amino-acid deletion in the OXA-405 protein sequence from residues Thr213 to Glu216 compared to the OXA-48 sequence (Fig. 2). The comparison of the hydrolysis spectra of OXA-405, OXA-48, and OXA-163 was done by cloning blaOXA-405, blaOXA-48, and blaOXA-163 genes in the pCR-Blunt II-Topo kit (Invitrogen) and expressing them in E. coli TOP10. OXA-405 and OXA-163 conferred similar resistance profiles, consisting of a decreased susceptibility to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and aztreonam compared to that conferred by OXA-48 (Table 2). As opposed to OXA-48, OXA-405, like the OXA-163 enzyme, once expressed in a reference E. coli strain was not associated with a decreased susceptibility to carbapenems (Table 2). Both the Carba NP test and the UV spectrophotometry analysis showed that OXA-405 and OXA-163 did not express significant imipenemase activity (Table 3). In addition, OXA-405 producers and also OXA-163 producers were 8-fold more susceptible to temocillin than OXA-48 producers (Table 2).

FIG 2.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of OXA-48, OXA-405, OXA-163, and OXA-247. Possible conserved residues of the active site of the OXA-48-type β-lactamases are highlighted in gray.

TABLE 3.

Specific activities of β-lactamases OXA-48, OXA-405, and OXA-163

| β-Lactams | Specific activity (mean mU/mg of protein ± SD) of: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| OXA-48 | OXA-405 | OXA-163 | |

| Amoxicillin | 981 ± 62 | 485 ± 35 | 795 ± 81 |

| Piperacillin | 450 ± 5 | 436 ± 4 | 214 ± 2 |

| Temocillin | 11 ± 2 | 5 ± 0.5 | 5 ± 0.4 |

| Ticarcillin | 647 ± 59 | 63 ± 6 | 80 ± 7 |

| Cefepime | 5 ± 0.5 | 27 ± 2 | 30 ± 3 |

| Cefotaxime | 60 ± 6 | 117 ± 10 | 167 ± 15 |

| Cefoxitin | 2 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.1 | 1 ± 0.1 |

| Ceftazidime | 2 ± 0.2 | 9 ± 0.8 | 53 ± 5 |

| Cefalotin | 75 ± 8 | 140 ± 12 | 130 ± 10 |

| Imipenem | 57 ± 4 | 3 ± 0.2 | 2 ± 0.2 |

| Meropenem | 3 ± 0.1 | 2 ± 0.2 | 2 ± 0.1 |

| Ertapenem | 2 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.1 | 1 ± 0.1 |

| Doripenem | 2 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.1 | 1 ± 0.1 |

| Aztreonam | 5 ± 0.5 | 14 ± 1 | 18 ± 2 |

The specific activities of OXA-405 and of OXA-163 were very similar for penicillins, broad-spectrum cephalosporins, and carbapenems. However, OXA-405 hydrolyzed less ceftazidime (6-fold less) than OXA-163 (Table 3). Both OXA-405 and OXA-163 had barely detectable activity against carbapenems compared to OXA-48 (∼25-fold less for imipenem) (Table 3). On the other hand, OXA-405 and OXA-163 hydrolyzed expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and aztreonam at high rates, while OXA-48 did not (Table 3). This activity against expanded-spectrum cephalosporins of OXA-405 was inhibited by the addition of tazobactam (Table 2).

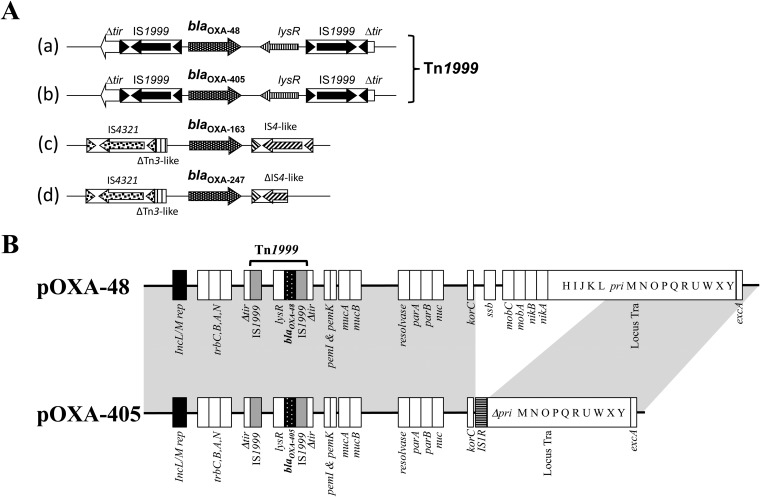

Genetic environment of the blaOXA-405 gene.

The blaOXA-405 gene was located on transposon Tn1999, as the blaOXA-48 gene usually is (4, 20). Plasmid DNAs of S. marcescens Sm1 (pOXA-48) and Sm2 (pOXA-405) were extracted and compared. A single plasmid was identified from each strain, of ca. 62 kb and ca. 46 kb for Sm1 and Sm2, respectively. A PCR-based replicon typing method revealed that these plasmids belonged to the same IncL/M incompatibility group. Whereas transformants in E. coli were obtained by using both plasmids, transconjugants were obtained with the pOXA-48 plasmid only. PCR mapping of plasmids pOXA-48 and pOXA-405 showed that pOXA-48 was structurally identical to the prototype IncL/M OXA-48-positive plasmid. Plasmid pOXA-405 had a backbone similar to that of pOXA-48 but had a 16,382-bp deletion from nucleotides 24210 to 40587 according to the reference blaOXA-48 plasmid (number JN626286, GenBank nucleotide database) (20). This deletion included the ssb gene, the mobC and mobA genes, the nikB and nikA genes, and a part of locus tra (traH, traI, traJ, traK, traL, and primase genes). This deleted DNA section was replaced by an insertion sequence, IS1R (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

(A) Schematic representation of the genetic environment of the blaOXA-48 (a), blaOXA-405 (b), blaOXA-163 (c), and blaOXA-247 (d) genes. The Tn1999 composite transposon is made of two copies of insertion sequence IS1999, bracketing a fragment containing the blaOXA-48 and blaOXA-405 genes. (B) Major structural features of the plasmid pOXA-405 from S. marcescens Sm2 in comparison with the prototype IncL/M blaOXA-48 plasmid (pOXA-48) (GenBank accession number JN626286). Common structures are highlighted in gray.

DISCUSSION

A novel OXA-48-type β-lactamase, OXA-405, has been identified here. OXA-405, like the other OXA-48-type β-lactamases OXA-163 and OXA-247, has a significant activity toward expanded-spectrum cephalosporins but barely any activity toward carbapenems. Therefore, it should be underlined that OXA-48-like β-lactamases, as opposed to all known KPC, NDM, VIM, or IMP β-lactamases, are not all significant carbapenemases. In addition, it has been shown that OXA-48-type producers with carbapenemase activity are mostly resistant to temocillin. Here, we confirm that this temocillin resistance trait would be a good criterion for differentiating OXA-48-type producers with and without carbapenemase activity.

Structural protein analysis of OXA-405, OXA-163, and OXA-247 showed that they possess at least the same four-amino-acid deletion in a specific region, from Thr213 to Glu216 (8, 13). This result agrees with crystal structure analysis of OXA-48 showing that Arg 214 (which is part of a β5 strand) is critical for carbapenemase activity (21). In addition, recent studies point out the crucial role of this short loop connecting β5 and β6 strands in conferring carbapenemase activity of Ambler class D β-lactamases (22, 23).

Genetic analysis of the S. marcescens clinical isolates Sm1 and Sm2 producing OXA-48 and OXA-405, respectively, indicates that they are clonally related. This result suggests that the blaOXA-405 gene may derive from the same ancestor, a blaOXA-48 gene. This hypothesis is reinforced by the common genetic environment of those two genes. Actually, the blaOXA-48 and blaOXA-405 genes were bracketed by two copies of an identical IS element, IS1999, forming a composite transposon Tn1999. This genetic environment was completely different from the mosaic structures made of insertion sequences and the truncated mobile element that surrounds the blaOXA-163 gene and its derivative, blaOXA-247 (Fig. 3) (8, 13). In addition, the blaOXA-405 gene was identified on the plasmid pOXA-405, which possessed a backbone similar to that of the IncL/M blaOXA-48-bearing plasmid (pOXA-48) (20), except for a deletion of ca. 16 kb replaced by the insertion sequence IS1R. This deletion/insertion led to the loss of conjugative genes and the related self-conjugative property of pOXA-405 (20). The selection pressure of a cephalosporin-containing treatment (here, cefepime) remains to be determined for selecting an OXA-48-type β-lactamase with activity against expanded-spectrum cephalosporins from an OXA-48-type β-lactamase with carbapenemase activity.

In conclusion, this report underlines that OXA-48-type β-lactamases are more diverse than expected. As exemplified by OXA-405, the OXA-48-type β-lactamases are not all true carbapenemases. The same statement is valid for another group of serine β-lactamases, the GES group of enzymes, in which GES-1 is an extended-spectrum β-lactamase, while GES-2 is a carbapenemase (24). Therefore, the first-line screening of carbapenemase producers in Enterobacteriaceae may be best based on the biochemical detection of carbapenemase activity in clinical settings. The molecular biology techniques, although useful, may overreport OXA-48-like producers as being all carbapenemases and, conversely, may fail to detect carbapenemase producers related to totally novel or slightly structurally modified carbapenemase genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Christophe De Champs, who let us work on the OXA-405-producing S. marcescens isolate.

This work was partially funded by a grant from the INSERM (U 914).

REFERENCES

- 1.Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P. 2010. Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:24–38. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01512-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins PG, Poirel L, Lehmann M, Nordmann P, Seifert H. 2009. OXA-143, a novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamase in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:5035–5038. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00856-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2006. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms and epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Infect 12:826–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poirel L, Potron A, Nordmann P. 2012. OXA-48-like carbapenemases: the phantom menace. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:1597–1606. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poirel L, Heritier C, Tolun V, Nordmann P. 2004. Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:15–22. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.1.15-22.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasap M, Torol S, Kolayli F, Dundar D, Vahaboglu H. 2013. OXA-162, a novel variant of OXA-48, displays extended hydrolytic activity towards imipenem, meropenem and doripenem. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 28:990–996. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2012.702343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdelaziz MO, Bonura C, Aleo A, El-Domany RA, Fasciana T, Mammina C. 2012. OXA-163-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Cairo, Egypt, in 2009 and 2010. J Clin Microbiol 50:2489–2491. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06710-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poirel L, Castanheira M, Carrer A, Rodriguez CP, Jones RN, Smayevsky J, Nordmann P. 2011. OXA-163, an OXA-48-related class D β-lactamase with extended activity toward expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2546–2551. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00022-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potron A, Nordmann P, Lafeuille E, Al Maskari Z, Al Rashdi F, Poirel L. 2011. Characterization of OXA-181, a carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamase from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4896–4899. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00481-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potron A, Nordmann P, Poirel L. 2013. Characterization of OXA-204, a carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamase from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:633–636. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01034-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potron A, Rondinaud E, Poirel L, Belmonte O, Boyer S, Camiade S, Nordmann P. 2013. Genetic and biochemical characterisation of OXA-232, a carbapenem-hydrolysing class D β-lactamase from Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Antimicrob Agents 41:325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oteo J, Hernandez JM, Espasa M, Fleites A, Saez D, Bautista V, Perez-Vazquez M, Fernandez-Garcia MD, Delgado-Iribarren A, Sanchez-Romero I, Garcia-Picazo L, Miguel MD, Solis S, Aznar E, Trujillo G, Mediavilla C, Fontanals D, Rojo S, Vindel A, Campos J. 2013. Emergence of OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and the novel carbapenemases OXA-244 and OXA-245 in Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:317–321. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez S, Pasteran F, Faccone D, Bettiol M, Veliz O, De Belder D, Rapoport M, Gatti B, Petroni A, Corso A. 2013. Intrapatient emergence of OXA-247: a novel carbapenemase found in a patient previously infected with OXA-163-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Infect 19:E233–E235. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampaio JL, Ribeiro VB, Campos JC, Rozales FP, Magagnin CM, Falci DR, da Silva RC, Dalarosa MG, Luz DI, Vieira FJ, Antochevis LC, Barth AL, Zavascki AP. 2014. Detection of OXA-370, an OXA-48-related class D β-lactamase, in Enterobacter hormaechei from Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3566–3567. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02510-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordmann P, Poirel L, Dortet L. 2012. Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1503–1507. doi: 10.3201/eid1809.120355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernabeu S, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2012. Spectrophotometry-based detection of carbapenemase producers among Enterobacteriaceae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 74:88–90. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dortet L, Brechard L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2014. Impact of the isolation medium for detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae using an updated version of the Carba NP test. J Med Microbiol 63:772–776. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.071340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kieser T. 1984. Factors affecting the isolation of CCC DNA from Streptomyces lividans and Escherichia coli. Plasmid 12:19–36. doi: 10.1016/0147-619X(84)90063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. 2005. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods 63:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poirel L, Bonnin RA, Nordmann P. 2012. Genetic features of the widespread plasmid coding for the carbapenemase OXA-48. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:559–562. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05289-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Docquier JD, Calderone V, De Luca F, Benvenuti M, Giuliani F, Bellucci L, Tafi A, Nordmann P, Botta M, Rossolini GM, Mangani S. 2009. Crystal structure of the OXA-48 β-lactamase reveals mechanistic diversity among class D carbapenemases. Chem Biol 16:540–547. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Luca F, Benvenuti M, Carboni F, Pozzi C, Rossolini GM, Mangani S, Docquier JD. 2011. Evolution to carbapenem-hydrolyzing activity in noncarbapenemase class D β-lactamase OXA-10 by rational protein design. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:18424–18429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110530108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell JM, Clasman JR, June CM, Kaitany KC, LaFleur JR, Taracila MA, Klinger NV, Bonomo RA, Wymore T, Szarecka A, Powers RA, Leonard DA. 2015. Structural basis of activity against aztreonam and extended-spectrum cephalosporins for two carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases from Acinetobacter baumannii. Biochemistry 54:1976–1987. doi: 10.1021/bi501547k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poirel L, Weldhagen GF, Naas T, De Champs C, Dove MG, Nordmann P. 2001. GES-2, a class A β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa with increased hydrolysis of imipenem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:2598–2603. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.9.2598-2603.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]