Abstract

The polyene antifungal amphotericin B (AmB) is widely used to treat life-threatening fungal infections. Even though AmB resistance is exceptionally rare in fungi, most Aspergillus terreus isolates exhibit an intrinsic resistance against the drug in vivo and in vitro. Heat shock proteins perform a fundamental protective role against a multitude of stress responses, thereby maintaining protein homeostasis in the organism. In this study, we elucidated the role of heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) family members and compared resistant and susceptible A. terreus clinical isolates. The upregulation of cytoplasmic Hsp70 members at the transcriptional as well as translational levels was significantly higher with AmB treatment than without AmB treatment, particularly in resistant A. terreus isolates, thereby indicating a role of Hsp70 proteins in the AmB response. We found that Hsp70 inhibitors considerably increased the susceptibility of resistant A. terreus isolates to AmB but exerted little impact on susceptible isolates. Also, in in vivo experiments, using the Galleria mellonella infection model, cotreatment of resistant A. terreus strains with AmB and the Hsp70 inhibitor pifithrin-μ resulted in significantly improved survival compared with that achieved with AmB alone. Our results point to an important mechanism of regulation of AmB resistance by Hsp70 family members in A. terreus and suggest novel drug targets for the treatment of infections caused by resistant fungal isolates.

INTRODUCTION

Amphotericin B (AmB) is a first-line antifungal that has been applied in clinics for decades to treat severe fungal infections, like invasive aspergillosis. Aspergillus fumigatus is the major cause of invasive aspergillosis, followed by Aspergillus terreus and Aspergillus flavus. However, A. terreus infections especially show a poor treatment response (1–3). As shown earlier, AmB targets the fungal cell membrane and promotes ergosterol sequestration and channel-mediated membrane permeabilization (4). Additional studies support the hypothesis that AmB induces common oxidative damage death pathways (5). In order to counteract and adapt to environmental stresses like oxidative damage, cells have evolved a diverse spectrum of molecular strategies. In particular, fungal pathogens have developed robust stress responses to counteract and overcome antimicrobial defenses encountered within hosts (6). One of the most powerful and highly conserved adaptation mechanisms comprises the heat shock response, which induces an array of cytoprotective genes encoding heat shock proteins (Hsps) (7). Hsps function as molecular chaperones, which repair and adapt to cell damage caused by aggregated proteins and ensure proper folding of newly synthesized proteins. They are found in all kingdoms of life. Several studies have highlighted the importance of Hsp90 in the AmB resistance of fungal pathogens (8, 9), and Hsp90-specific antibodies have been used to treat invasive candidiasis (10, 11). Some of the Hsps best characterized at the functional and molecular levels belong to the 70-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70) family. These ATP-dependent chaperones constitute central components of the cellular surveillance network. Hsp70 members are highly conserved in all species except some archaea. Prokaryotic Hsp70 proteins are about 50% similar to eukaryotic Hsp70 proteins. Eukaryotic Hsp70 family members are found in all cellular compartments, and they possess common structural and sequence features. Hsp70 family members display a highly conserved regulatory amino-terminal nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) of approximately 40 kDa and a less conserved carboxy-terminal substrate-binding domain of about 25 kDa.

Several studies have indicated that AmB induces the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (4, 5, 12, 13), which damage DNA, lipids, and proteins and result in cellular impairment. Hsps are triggered by various stressors and initiate adaptation mechanisms in response to cellular stress as well as protein folding processes (14). Unlike Hsp90, Hsp70 proteins promiscuously interact with all proteins in their unfolded, misfolded, or aggregated forms.

In the study described here, we evaluated the role of the various Hsp70 members in AmB resistance in A. terreus and show that susceptible and resistant isolates have distinct expression patterns. Resistant A. terreus isolates exert a strong induction of most Hsp70 family members upon AmB exposure. In contrast, susceptible A. terreus isolates display a much lower Hsp70 response. Furthermore, Hsp70 inhibitors considerably increased the susceptibility of resistant A. terreus isolates to AmB but had little impact on susceptible isolates. Also, in in vivo experiments involving cotreatment with AmB and the Hsp70 inhibitor pifithrin-μ, significantly improved survival was found upon infection with resistant strains. Our results point to an important mechanism of regulation of AmB resistance by Hsp70 family members in A. terreus and suggest novel drug targets for the treatment of infections caused by resistant fungal isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and culture conditions.

The clinical isolates of A. terreus and A. fumigatus used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. All clinical isolates were identified using internal transcribed spacer sequencing (15). Experiments were performed with three AmB-susceptible A. terreus (ATS) and three AmB-resistant A. terreus (ATR) isolates as well as three AmB-susceptible A. fumigatus isolates. Strains were cultured on Aspergillus complete medium and routinely incubated at 37°C. Aspergillus complete medium is composed of 20 g glucose, 2 g peptone, 1 g tryptone, 1 g yeast extract, 20 ml 50× salt solution (50× salt solution is [per liter] 26 g KCl, 26 g MgSO4·7 H2O, 76 g KH2PO4), 1 ml trace element stock solution (trace element stock solution is [per liter] 0.04 g Na2B4O7·10H2O, 0.4 g CuSO4·5H2O, 0.741 g MnSO4·H2O, 8 g ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.8 g Na2MoO4·2H2O), and 12.5 g agar per liter (pH 6.5) (16). Conidia were harvested after 7 days in saline–Tween 80 (0.9% NaCl, 0.01% Tween 80), filtered through 10-μm-pore-size filters (CelTrics; Partec), and immediately transferred to RPMI 1640 liquid or solid medium. Where indicated, the medium was supplemented with AmB deoxycholate (Bristol Meyer Squibb, Vienna, Austria), pifithrin-μ (Tocris Bioscience), Ver1550008, or KNK423. Conidia were washed and resuspended in insect physiological saline (IPS) for Galleria mellonella larva infection studies.

Susceptibility testing of fungal strains.

In vitro susceptibility testing was performed according to the EUCAST methodology (17). Strains displaying AmB MICs of ≤1 μg/ml and AmB MICs of ≥2 μg/ml were categorized as AmB susceptible and AmB resistant, respectively (18, 19). AmB MICs ranged from 0.062 to 0.125 μg/ml for ATS strains (n = 3) and from 4 to >8 μg/ml for ATR strains (n = 3); tests were confirmed by Etest, by which MICs ranged from 0.094 to 0.125 μg/ml and 8 to 32 μg/ml for ATS and ATR strains, respectively. Inhibition assays were done according to the instructions provided with the Etest (bioMérieux, France), with RPMI 1640 agar being supplemented with Hsp inhibitors where indicated (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Hsp70 inhibitors enhance AmB susceptibility of ATR isolates

| Hsp70 inhibitor (concn [μM]) | MICa (μg/ml) |

|

|---|---|---|

| ATR | ATS | |

| Control | ≥32 | 0.27 ± 0.097 |

| Pifithrin-μ (5) | 1.666 ± 0.288** | 0.168 ± 0.037 |

| Pifithrin -μ (10) | 0.916 ± 0.144** | 0.168 ± 0.037 |

| Pifithrin-μ (20) | 0.833 ± 0.288** | 0.058 ± 0.010* |

| Ver155008 (5) | 29.333 ± 4.618 | 0.168 ± 0.037 |

| Ver155008 (10) | 26.666 ± 4.618 | 0.084 ± 0.017* |

| Ver155008 (20) | 4.666 ± 1.154** | 0.084 ± 0.017* |

| KNK423 (5) | 21.333 ± 4.618* | 0.168 ± 0.037 |

| KNK423 (10) | 24.000 ± 0.000* | 0.058 ± 0.010* |

| KNK423 (20) | 21.333 ± 4.618* | 0.058 ± 0.010* |

Etest MICs (48 h) are given as means ± standard deviations. Strains were categorized as AmB susceptible (MICs ≤ 1 μg/ml) and AmB resistant (MICs ≥ 2 μg/ml). Tests were performed at least thrice in duplicate for ATS (n = 3) and ATR (n = 3) strains. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, P = 0.05; **, P = 0.01) compared to the results for the controls.

Identification of Hsp70 orthologs and phylogenetic analyses.

Genomic data for A. terreus were obtained from the Broad Institute (http://www.broadinstitute.org/fetgoat/index.html, accessed 11 November 2014), the Central Aspergillus Data REpository (CADRE), and the Comparative Fungal Genomics Platform (CFGP; v2.0) using the conserved Hsp70 family sequence with Interpro accession number IPR013126 as the query sequence (20–22). Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast Hsp70 members were received from the Saccharomyces genome database (http://www.yeastgenome.org, accessed 5 November 2014) and the EMBL-EBI website (http://www.ebi.ac.uk, accessed 1 November 2014) (23). For PSI-BLAST searches, S. cerevisiae protein sequences were compared with A. terreus sequences by BLAST analysis (24). Multiple-protein-sequence alignments were performed with the ClustalW program and the sequences in the Pasteur bioweb (v2.0) database. On the basis of this alignment, an unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Phylip phylogeny inference package (v3.67) with the Kimura formula distance model (25). The confidence level was analyzed using bootstraps of 1,000 iterations. Moreover, Hsp70 homologs were analyzed using the MitoProt II (v1.101) algorithm and the WoLF PSORT protein subcellular localization prediction tool (26, 27), in order to predict their cellular localization according to the localizations described for the well-characterized S. cerevisiae Hsp70 proteins (28–33).

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR analyses.

Harvested mycelia were washed thrice with distilled water and frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was extracted from the ground mycelia by the TRIzol method according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Samples were dissolved in 100 μl of RNase-free water. cDNA was synthesized from 750 ng RNA using iScript reverse transcription (RT) supermix prior to quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses. For qPCR, SsoFast EvaGreen master mix, forward and reverse primers, and cDNA were mixed, and the volume was made to 20 μl with RNase-free water. Cycling conditions were as follows: 3 min at 98°C and 40 cycles of 5 s at 98°C and 5 s at 58°C, followed by melt curve analyses. The expression levels were analyzed using the gene expression software of the CFX96 real-time detection system (the 2−ΔΔCT threshold cycle [CT] method; CFX manager software; Bio-Rad). The genes and primer sequences used are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Primers were designed to span exon-intron boarders, and amplicon lengths ranged from 104 to 138 bp.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting.

Protein extractions and immunoblotting were performed as described by Valiante et al. (34) with slight modifications. Briefly, mycelia were ground in liquid nitrogen, resuspended in 50 mM ice-cold sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) supplemented with a proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and incubated for 1 h on ice. Samples were spun at 18,000 × g and 4°C for 15 min, and cleared supernatants were transferred to a new tube. Forty micrograms of protein was loaded onto 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and the gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). The blots were incubated with a recombinant Hsp70 monoclonal mouse antihuman antibody (monoclonal antibody 3A3; Novus Biologicals) to detect A. terreus homologs of Ssa and Ssb. A rabbit polyclonal anti-alpha-tubulin antibody (Abcam) was used as a loading control. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Dako and detected with the LumiGLO reagent (Cell Signaling Technology).

A. terreus proteome profiles after AmB treatment.

Fungal strains were incubated with sublethal AmB concentrations (1 and 2 μg/ml for ATR strain and 0.1 μg/ml for ATS strains) in RPMI 1640 liquid medium for 24 h at 37°C and 200 rpm. Protein extraction and two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis were performed as described by Arnitz et al. (35). Protein spots were visualized by silver staining, and the gels were analyzed using ImageMaster 2D software (v5.0; Amersham Bioscience). Protein spots were excised from the gels, cysteines were blocked with iodoacetamide, and gel pieces were dried with acetonitrile. Proteolytic digestion was carried out with trypsin, and the extracted peptides were separated on a preconcentrator in combination with a fritless nanospray column packed with reverse-phase C18 material. Peptides were further analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS; LTQ ion trap instrument; Thermo Finnigan). An Aspergillus database was searched for MS/MS spectra matching those obtained in the presented study using the SEQUEST program (BioWorks; Thermo Finnigan).

Overexpression of Ssa and Ssb and generation of GFP-tagged versions.

Constructs of Ssa and Ssb carrying a carboxy-terminal green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion were generated by fusion PCR (36). In brief, the respective gene with a 1.7-kbp promoter fragment was amplified by PCR with primers harboring overlap extensions for the GFP fragment. In a second PCR, gfp was accumulated from plasmid psidLgfp (37) with primers harboring overlap extensions for the terminator region of the genes. The terminator regions were amplified with overhangs complementary to the gfp 3′ end. A fusion PCR using the three distinct purified PCR products was employed to produce the transformation constructs. Transformation constructs were utilized in cotransformations with the hygromycin resistance plasmid pAN7.1 (38) in ATS strain T77. All primers are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Southern blots of the transformants used for further experiments are shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

Cotreatment with AmB and the Hsp70 inhibitor pifithrin-μ using an in vivo Galleria mellonella model.

Galleria mellonella larvae (Handler, Lebendköder-Großhandel, Leobersdorf, Austria) were stored in the dark at 18°C prior to use. Freshly harvested conidial suspensions were filtered through a 40-μm-pore-size nylon cell strainer (BD Falcon). The fungal pathogens (1 × 106 conidia per larva) and therapeutic agents were injected into the larvae as previously described (39–42). Briefly, the conidial suspension and the drug were injected into the hemocoel via a distinct proleg. The larvae were incubated at 37°C, and the daily survival rate was monitored. IPS-treated control larvae and larvae treated with AmB (5 mg/kg of body weight, corresponding to 1.5 μg/ml in larvae) or AmB (5 mg/kg) plus pifithrin-μ (5 μM) were investigated (10 larvae per group, with an average larval weight of 300 ± 20 mg), and the experiments were repeated twice (20 larvae in total).

Statistical analyses.

All in vitro assays were performed in three independent experiments in technical duplicate or triplicate. The number performed in each experiment is indicated in the appropriate figure legend. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's unpaired t test or two-way analysis of variance. In vivo experiments were performed using 20 larvae per individual group. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed with the Mantel-Cox test. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The Aspergillus terreus genome encodes nine Hsp70 family members.

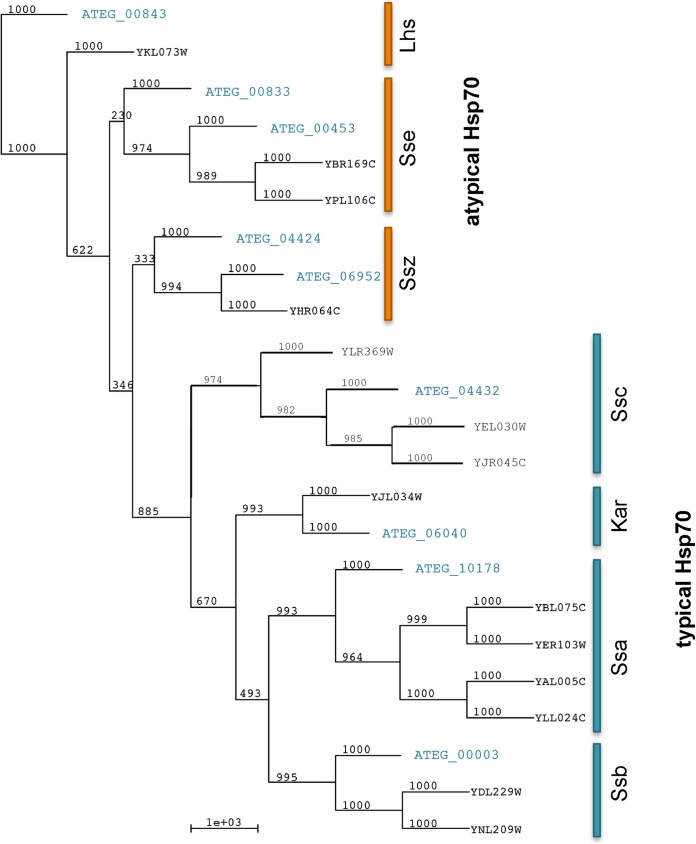

In a first step, we identified all Hsp70 family members present in the genome of A. terreus. Using the Hsp70 family domain sequence with Interpro accession number IPR013126 as a query template, we identified nine Hsp70 homologs in A. terreus, which was in contrast to the findings of a previous study, where eight Hsp70 family members were described (43). All 9 identified A. terreus Hsp70 proteins were homologous to the 14 well-characterized S. cerevisiae Hsp70 proteins. We found that the identified Hsp70 members clustered within the seven distinct subfamilies of S. cerevisiae, which constitute different groups according to subcellular localization and phenotypic effects. The additional Hsp70 in A. terreus, ATEG_00833, was annotated as a putative uncharacterized protein. However, the protein displays all features of an Hsp70 family member according to the TrEMBL data set containing the domains whose sequences have accession numbers IPR013126, PF00012, and PR00301. A phylogenetic tree of S. cerevisiae and A. terreus Hsp70 members is depicted in Fig. 1. All subfamilies described in yeasts were identified to have at least one homolog in A. terreus. Two homologs each for the putative Sse (ATEG_00833, ATEG_00453) and Ssz (ATEG_06952, ATEG_04424) homologs were characterized in the genome of A. terreus. Ssz is a ribosome-associated atypical Hsp70 member that interacts with Ssb (44). Ssa and Ssb homologs are cytoplasmic Hsp70 in yeast, whereas Ssc (ATEG_4432) and Kar2 (ATEG_06040) are localized in mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), respectively. Consistent with the sequences of the yeast Ssc and Kar2 proteins, the respective A. terreus homologs harbor an amino-terminal mitochondrial import sequence for the Ssc homolog (amino acids 1 to 33; probability, 0.9949) and the ER retention motif (KDEL) at the carboxy terminus for the Kar2 homolog, as assessed by use of the MitoProt II (v1.101) algorithm and the WoLF PSORT tool. The member of the LHS subfamily (ATEG_00843), an atypical subfamily and a nucleotide exchange factor (NEF) for Kar2, also possesses an ER retention motif (HDEL).

FIG 1.

An unrooted phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree of Hsp70 family members of S. cerevisiae and A. terreus reveals the evolutionary relationship among the Hsp70 members. Bootstrap values are depicted at the nodes, and branch lengths are shown, too. The distinct Hsp70 subfamilies of A. terreus are illustrated in blue.

AmB treatment elevates different Hsp70 genes in resistant and susceptible A. terreus isolates.

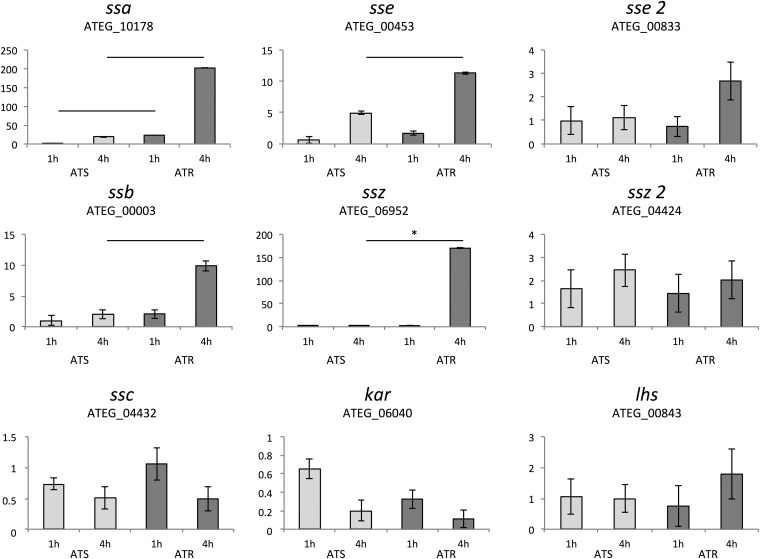

To gain insights into the influence of Hsp70 proteins on AmB resistance, we exposed clinical AmB-resistant A. terreus (ATR; n = 3) and AmB-susceptible A. terreus (ATS; n = 3) isolates (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) for 1 h and 4 h to AmB (1 μg/ml) and determined the expression levels of the Hsp70-encoding genes by RT-qPCR. The mRNAs of seven of the nine Hsp70 members increased due to AmB exposure and showed a time-dependent enhancement. The ssa and ssb cytosolic Hsp70 homologs were especially induced to significantly higher expression levels in ATR isolates after 1 h and 4 h of AmB exposure (23.38-fold and 201.95-fold, respectively, for ssa and 2.10-fold and 9.90-fold, respectively, for ssb; Fig. 2). In contrast, the ATS isolates exhibited an alleviated response even after 4 h of AmB exposure (0.39-fold and 18.34-fold at 1 and 4 h, respectively, in the case of ssa and 1.02-fold and 1.99-fold at 1 and 4 h, respectively, for ssb; Fig. 2). The gene expression levels of the ssc and kar2 homologs, present in the mitochondria and ER, respectively, decreased upon AmB exposure independently of time and strain (Fig. 2). The mRNAs of atypical Hsp70 members, which are assumed to serve as NEFs for the canonical Hsp70 in yeast, displayed significantly higher levels of expression in ATR isolates than ATS isolates (sse [ATEG_00453], 11.34-fold in ATR isolates and 4.94-fold in ATS isolates; ssz [ATEG_0952], 169.86-fold in ATR isolates and 1.41-fold in ATS isolates). We show here that ssb and ssz, which together with Zou1 form the ribosome-associated complex, are jointly upregulated in ATR isolates following AmB treatment.

FIG 2.

AmB treatment alters the abundance of mRNA of Hsp70 family members. For RNA extraction, all strains were cultured in RPMI 1640 liquid medium for 24 h at 37°C and 200 rpm. AmB (1 μg/ml) was added for 1 h and 4 h. Samples were analyzed by RT-qPCR. Lines above the bars indicate significant changes within the two groups (P < 0.05), and lines labeled with asterisks indicate highly significant changes (P < 0.01). The means ± standard deviations were calculated from three independent experiments for each condition with three ATS isolates (light gray) and three ATR isolates (gray). The y axes indicate relative fold expression (2−∆∆CT).

Proteomic analyses reveal differences in Hsp70 homologs of ATR and ATS isolates after AmB treatment.

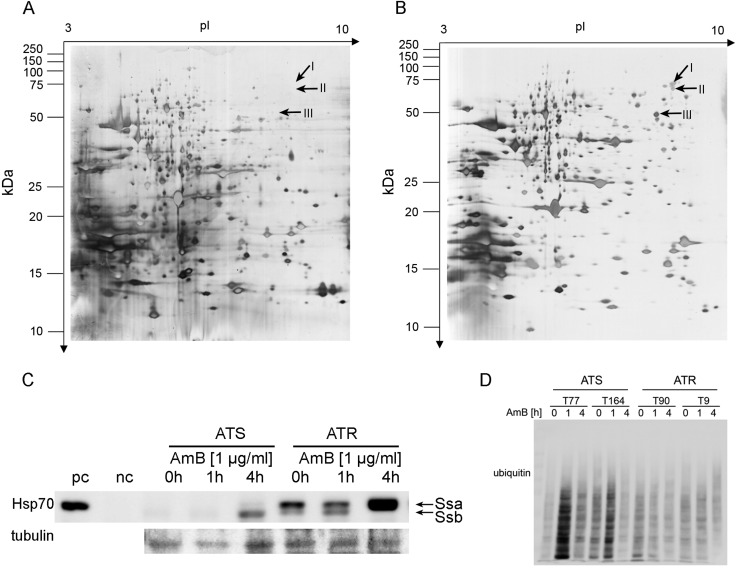

Next we studied the Hsp70 members Ssa and Ssb at the proteomic level to correlate gene expression levels and Hsp70 protein content upon AmB treatment. For this, we performed 2D SDS-PAGE followed by MS/MS analysis to detect proteins differentially expressed in ATR and ATS extracts upon AmB exposure. Ssa und Ssb homologs were analyzed by immunoblotting, using an anti-human Hsp70 (3A3) antibody, since fungus-specific antibodies are hardly available. In silico analysis revealed that Hsp70 homologs Ssa and Ssb displayed the highest similarity to their human counterparts (over 80%). By immunoblot analyses, two bands of approximately 70 kDa, corresponding to the molecular masses of Ssa and Ssb, were detected using the anti-human Hsp70 antibody. Additionally, immunoblots of GFP-tagged Ssa and Ssb lysates showed bands of about 100 kDa using the Hsp70 antibody or a GFP antibody. This finding additionally confirmed the specificity of the Hsp70 antibody for fungal strains.

For 2D SDS-PAGE experiments, strains were treated with 1 μg/ml AmB and untreated cultures served as positive controls. Interestingly, Ssb was found to be upregulated in ATR strains treated with AmB compared to the level of regulation in untreated controls, where no spot was detected in silver-stained 2D SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 3A and B). Compared to the spot intensity in ATS strains treated with AmB, the spot intensity was more than 80% higher in ATR strains. Hence, this protein spot was further investigated. MS/MS analysis revealed 29 distinct peptides corresponding to Ssb (ATEG_00003), and these represented 57.9% of all peptides identified in this spot.

FIG 3.

Hsp70 members Ssa and Ssb are upregulated by AmB treatment and display distinct patterns in ATS and ATR strains. (A, B) Representative silver-stained 2D gels of ATR protein extracts grown in the absence (A) or presence (B) of AmB (2 μg/ml). 2D gel electrophoresis was performed with different strains and at least two independent cultures with two AmB concentrations (1 and 2 μg/ml for ATR strains and 0.1 and 0.2 μg/ml for ATS strains). Spots I to III, marked with arrows, were present only under AmB treatment conditions and were further analyzed by MS/MS. (C) ATS and ATR strains displayed different Ssa and Ssb levels due to AmB treatment (1 μg/ml). A representative immunoblot is shown. Experiments were performed with all ATS (n = 3) and ATR (n = 3) strains and repeated twice. pc, positive control; nc, negative control. (D) AmB treatment increased the amounts of ubiquitinated proteins in ATS strains at early time points. Protein extracts of ATR and ATS strains were separated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The blots were probed with an ubiquitin-specific antibody that detects ubiquitinated and polyubiquitinated proteins. A representative immunoblot is shown.

As shown by immunoblotting, both Hsp70 members (Ssa, Ssb) were upregulated in ATR strains after 1 h of AmB treatment, but only the amount of Ssa was elevated after 4 h of AmB exposure (Fig. 3C). In contrast, only Ssb was activated in ATS strains after 4 h of AmB treatment (Fig. 3C). Ssa in ATS strains, however, displayed just a slight increase after 4 h of AmB treatment, reflecting ssa mRNA expression (Fig. 3C). A representative immunoblot is shown in Fig. 3C. Fang et al. (45) demonstrated that yeast cells carrying a thermosensitive ssa1 mutant allele and lacking the other three yeast ssa members (ssa2 to ssa4) respond to heat shock with increased levels of ubiquitinated proteins. In ATS strains, we observed an increase in the amounts of ubiquitinated proteins after 1 h of AmB treatment, which decreased again at the 4-h time point (Fig. 3D). In contrast, ATR strains did not show alterations in the amounts of ubiquitinated proteins upon AmB exposure (Fig. 3D).

Inhibition of Hsp70 increases AmB susceptibility in vitro.

In further experiments, we studied the efficacy of three different Hsp70 inhibitors (Ver1550008, KNK423, and 2-phenylacetylenylsulfonamide [PES; also known as pifithrin-μ]) on AmB susceptibility. Hsp70 inhibitors reported to date mediate inhibition by targeting either the ATP-binding site or allosteric sites in the NBD or the substrate-binding sites; the exact binding mechanisms remain unclear.

Pifithrin-μ proved to be the most potent of the tested inhibitors; in ATR strains, cotreatment with AmB resulted in decreased MICs, and these decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Table 1). In ATS strains and A. fumigatus, only the highest concentration (20 μM) tested resulted in a significant decrease in the MICs (Table 1). Ver155008, an ATP-binding-site inhibitor, affected only ATR strains (Table 1). KNK423 decreased the MICs of all AmB-resistant strains but did so to a lesser extent than pifithrin-μ. KNK423 lowered the MICs of both the ATS and AFS strains, but the effect was less pronounced; these data emphasize that different Hsp70 inhibitors cause distinct responses.

Inhibition of Hsp70 increases AmB susceptibility in vivo.

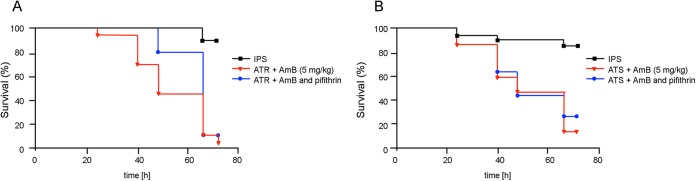

In order to determine the effects of Hsp70 inhibition in vivo, we performed G. mellonella infection experiments using pifithrin-μ and AmB. Consistent with the effects observed in vitro, combinatorial treatment significantly increased the survival of larvae infected with ATR compared to that of ATR-infected larvae (Fig. 4A). In contrast to the results for the ATR strains, pifithrin-μ exerted little effect on ATS strains in vivo (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Combinatorial treatment with AmB and pifithrin-μ significantly decreases the virulence of A. terreus ATR in the Galleria mellonella infection model. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of 20 G. mellonella larvae per group infected with ATR (A) or ATS (B) at 1 × 106 conidia per larva. IPS served as a control. All combinatorial treatments were injected 2 h after fungal infection. Results display the means from two independent experiments with two different batches of larvae (n = 20).

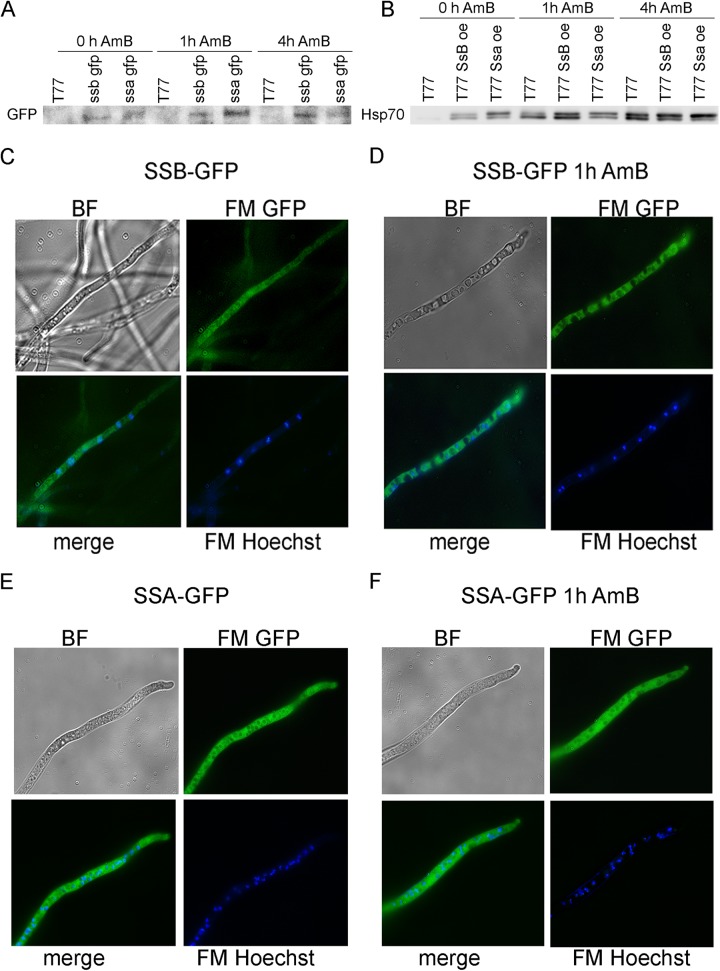

Overexpression of ssa and ssb causes phenotypic alterations in ATS strains but does not influence AmB susceptibility.

To assess the role of the most-upregulated typical Hsp70 proteins, Ssa and Ssb, we aimed to introduce multiple copies of the respective genes into ATS strains. In an additional approach, a carboxy-terminal GFP tag was introduced into these proteins in ATS strains.

The resulting transformants displayed phenotypic differences from the progenitor strain. Wild-type ATS strains displayed decreased sporulation compared to ATR strains, whereas ATS strains with additional copies of either ssa or ssb showed sporulation rates similar to those of the ATR strains. At the protein level, GFP tagging and overexpression were confirmed by immunoblotting and fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5A and B). Despite the overexpression of Ssa and Ssb in the ATS strains, no significant differences in AmB resistance compared to that of the progenitor ATS strains was observed.

FIG 5.

Overexpression of Ssa and Ssb increases the respective protein levels upon exposure to AmB. (A and B) Immunoblots of strains harboring GFP-tagged versions of Ssa or Ssb (A) and protein extracts of transformants with multiple copies of Ssa or Ssa probed with an Hsp70 antibody (B). The ATS progenitor strain T77 served as a control in the immunoblots. (C and E) Micrographs of Ssb-GFP (C) and Ssa-GFP (E), confirming the cytoplasmic localization of Ssa and Ssb. (D and F) Ssb-GFP (D) and Ssa-GFP (F) are induced by AmB (1 μg/ml) exposure. Hoechst33342 was used to stain the nuclei. BF, bright-field microscopy; FM, fluorescence microscopy.

DISCUSSION

We studied the role of A. terreus Hsp70 family members upon AmB treatment using susceptible and resistant clinical isolates. In vitro, blocking of Hsp90 reduced the AmB MICs in A. terreus but failed to improve the in vivo outcome in a murine infection model (9). This was possibly due to the immunosuppressive side effects of the drug (9). Here, we illustrate diverging Hsp70 expression patterns at the transcriptional and proteomic levels in ATR and ATS strains. Consistent with the results of studies performed in yeast, in silico analyses revealed that A. terreus possesses members of all seven Hsp70 subfamilies. Two members of the fast-evolving Sse and Ssz subfamilies were found in the genome of A. terreus, consistent with the predicted evolutionary dynamics of fungal Hsp70 (43). Interestingly, that study predicted eight Hsp70 homologs in A. terreus (43), while we identified nine homologs in the present study. This difference might result from distinct identification criteria, i.e., those used in BLASTp and TBlastN versus IPRO domain searches. The additional Hsp70 member, ATEG_00833, a conserved hypothetical protein, consists of 716 amino acid residues and within the Sse subfamily clusters together with ATEG_00453. The phylogenetic relationship of ATEG_00833 to the Sse subfamily was more distant than that of ATEG_00453. At the transcriptional level, ATEG_00833 was expressed in all tested strains and was upregulated in ATR strains compared to its level of regulation in ATS strains (fold change, 2.68 ± 0.82 versus 1.12 ± 0.51).

The individual Hsp70 subfamily members exhibited different expression patterns in ATS and ATR strains when the strains were treated with AmB. The abundances of ssa and ssb mRNAs were significantly increased in ATR strains after AmB exposure. After 1 h and 4 h of AmB treatment, ATR strains displayed 23.38- and 201.95-fold increases in the ssa mRNA expression level, respectively, correlating to 59.97-fold and 11.01-fold higher levels of ssa expression compared to those in the ATS strains. Also, ssb mRNA expression increased in the ATR strains upon AmB treatment, albeit to a lower extent (2.10 ± 0.74 and 9.90 ± 0.84 compared to the level of expression in the untreated control at 1 h and 4 h, respectively). The AmB-mediated upregulation of ssb mRNA in ATR strains was 2.05- and 4.98-fold higher than that in ATS strains at 1 and 4 h, respectively.

Interestingly, AmB treatment reduced the levels of the Hsp70 members ssc and kar, which are present in the mitochondria and ER, respectively. Consistent with the higher levels of expression of ssa and ssb mRNA, particularly in ATR strains, the respective putative nucleotide exchange factors of the Hsp70 family, sse and ssz, were also upregulated. Sse1 of S. cerevisiae belongs to the Hsp110 subfamily of Hsp70-related chaperones and is found in association with the cytosolic Hsp70 proteins Ssa and Ssb in yeast (31, 46, 47). The Sse and Ssz homologs, which were more closely related to their counterparts in S. cerevisiae than to their counterparts in other species, displayed higher levels of enhancement by AmB treatment than in ATS.

The majority of A. terreus Hsp70 genes were immediately induced in the ATR strains by AmB treatment, pointing to a role of the Hsp70 stress response in resistance mechanisms. We illustrated at the transcriptional level that in ATR strains an immediate Hsp70 response is initiated upon AmB treatment, suggesting that ATR is better able than ATS to cope with cellular stress. Also, at the protein level, Ssb was found to be upregulated after AmB exposure only in ATR strains, as assessed by 2D electrophoresis followed by mass spectroscopy. Additionally, by immunoblotting we detected higher Ssb levels in ATR strains than ATS strains shortly after exposure to AmB. In contrast, Ssb upregulation was detectable in ATS strains only at a later time point, where the resistant strains already displayed high levels of Ssa.

In yeast, Ssa Hsp70 members were described to constitute the major cytosolic Hsp70 mediating protein folding (48). The ubiquitin proteasome system comprises a major route for protein degradation, and damaged proteins are ubiquitinated by an enzymatic E1/E2/E3 cascade and targeted for degradation by the 26S proteasome. Studies in yeast illustrated that hampered Ssa proteins cause elevated levels of ubiquitinated proteins (45). Since we observed severe differences in Ssa and Ssb abundance in ATS and ATR strains, especially when the strains were treated with AmB, and because of the absence of Ssa protein in ATS strains at the early time point and a weak signal at the later time point, we were interested in whether ATS displays higher levels of ubiquitinated proteins. Several studies have suggested that AmB induces oxidative stress and, in turn, fosters protein misfolding (5, 8). Remarkably, we observed elevated levels of ubiquitinated proteins in the ATS strains at the early time point, indicating that the cytosolic Hsp70 members Ssa and Ssb are required for proteostasis when cells are stressed by AmB treatment.

Due to the differences between the ATS and ATR strains mentioned above, we next investigated if inhibition of Hsp70 members impacts the efficacy of AmB and renders ATR isolates susceptible to the drug. Indeed, we found that ATR strains had greater susceptibility to AmB when three different Hsp70 inhibitors were used in combination with AmB. Hsp70 inhibitors had only limited effects on the ATS strains. Since the tested inhibitors interfere with distinct Hsp70 sites, the various modes of action might explain the different inhibition efficacies (49). The Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin and its derivative, 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG), displayed a more pronounced efficacy against ATR strains than the Hsp70 inhibitors tested in the present study. Hsp90, a central and highly conserved chaperone in eukaryotes, was found to be essential in A. fumigatus (50). Thus, the inhibition of one essential target might result in a marked decline in viability and a concomitant decrease in the MIC. Ver155008, an adenosine-derived Hsp70 inhibitor that targets the ATP-binding site and inhibits chaperone activity, caused a significant reduction in the MIC for ATR strains at the highest concentration tested. The AmB MIC values for ATS and A. fumigatus also decreased. These effects could result from the broad specificity of Ver155008 for other Hsp family members, mainly because it is a nucleotide derivative. Additionally, this adenosine analogue possesses two labile benzyl groups that may cause unspecific reactivity toward proteins (51). KNK423, a benzylidene lactam compound, blocks the induction of Hsp70, Hsp72, and Hsp105 (52). In vitro inhibition experiments with KNK423 resulted in decreased MICs in ATR strains at all concentrations tested compared to those achieved with AmB treatment alone. However, this decline in the MIC for ATR strains was not sufficient to abrogate resistance in the ATR strains.

Pifithrin-μ, which inhibits chaperone activity by interactions with the substrate-binding site and causes an allosteric inhibition, displayed the most effective outcome in decreasing the AmB MICs of ATR strains, which decreased from ≥32 μg/ml to ≤1 μg/ml, therefore rendering ATR isolates susceptible (19). Hence, we tested this inhibitor in vivo in the invertebrate G. mellonella infection model, and the results correlated well with those obtained in vitro. ATR-infected G. mellonella larvae survived after AmB and pifithrin-μ treatment, whereas they did not after treatment with AmB alone. In contrast, ATS-infected Galleria larvae exhibited no increased survival upon combinatorial treatment. This efficacy of cotreatment in ATR-treated Galleria larvae was especially detectable at early time points. The decline in efficiency at later time points is thought to go along with the diminished stability or metabolism of pifithrin-μ in the host, since only a single dose was administered at 2 h postinfection. The results obtained in the Galleria invertebrate model of A. fumigatus infection correlated well with those of virulence studies performed in mice (53); however, this model exhibits some limitations with respect to multiple administrations of a compound. Repeated administrations might result in higher toxicity, especially upon application of several substances (54). In murine infection models, pifithrin-μ was repeatedly applied at higher concentrations (25 mg/kg [138 μM] on each of 3 days) (55), which might in part explain the lower rates of survival in our in vivo Galleria infection experiments at later time points.

Additionally, we overexpressed Ssa and Ssb in ATS strains to study the impact of these Hsp70 members on susceptibility to AmB. Overexpression of either Ssa or Ssb alone did not impact susceptibility to AmB, which suggests that Hsp70 members function in a cooperative manner and elevation of the level of only one of the typical Hsp70 members is not able to compensate for AmB susceptibility in ATS strains. Typical Hsp members like Ssa and Ssb function through a nucleotide-dependent cycle and require cochaperones, the nucleotide exchange factors, for the release and exchange of ADP for ATP. The nucleotide exchange factors for yeast Ssa and Ssb Hsps are the Sse and Ssz proteins, and they also belong to the Hsp70 family (56). Taking into account the fact that nucleotide exchange factors control the functionality of typical Hsps and that Sse or Ssz is expressed at a lower level in ATS strains, overexpression of a typical Hsp might not improve the performance of a functional complex, as was also observed herein.

In this study, we provide evidence that susceptible and resistant A. terreus isolates exhibit distinct Hsp70 responses when treated with AmB. ATS strains displayed a mitigated Hsp70 stress response along with a high level of susceptibility to AmB. Especially, cytosolic Hsp70 members displayed an increase in level in ATR strains due to AmB treatment. Inhibition of Hsp70 resulted in increased AmB susceptibility in vitro which was more pronounced in ATR strains. In vivo treatment with the Hsp70 inhibitor pifithrin-μ and AmB significantly enhanced the survival of G. mellonella larvae infected with ATR. Overexpression of the cytoplasmic Hsp70 Ssa or Ssb had only a small effect on AmB susceptibility in ATS strains, indicating that a single Hsp70 member is not able to change the promiscuous Hsp70 response. These results underline a role for the Hsp70 stress response in AmB treatment and might suggest novel targets in the treatment of infections caused by AmB-resistant A. terreus strains.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Anna Maria Tortorano (Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milan, Milan, Italy) for providing the AmB-susceptible A. terreus strain and Barbara Kainzner and Caroline Hörtnagl for technical support.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (I 661 to C.L.-F., P25491 to P.G.), the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Anniversary Fund (project 14875 to W.P.), and the Tiroler Wissenschaftsfonds (2012-1-19 to E.J.).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.05164-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pastor FJ, Guarro J. 2014. Treatment of Aspergillus terreus infections: a clinical problem not yet resolved. Int J Antimicrob Agents 44:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanafani ZA, Perfect JR. 2008. Antimicrobial resistance: resistance to antifungal agents: mechanisms and clinical impact. Clin Infect Dis 46:120–128. doi: 10.1086/524071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lass-Flörl C, Griff K, Mayr A, Petzer A, Gastl G, Bonatti H, Freund M, Kropshofer G, Dierich MP, Nachbaur D. 2005. Epidemiology and outcome of infections due to Aspergillus terreus: 10-year single centre experience. Br J Haematol 131:201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson TM, Clay MC, Cioffi AG, Diaz KA, Hisao GS, Tuttle MD, Nieuwkoop AJ, Comellas G, Maryum N, Wang S, Uno BE, Wildeman EL, Gonen T, Rienstra CM, Burke MD. 2014. Amphotericin forms an extramembranous and fungicidal sterol sponge. Nat Chem Biol 10:400–406. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belenky P, Camacho D, Collins JJ. 2013. Fungicidal drugs induce a common oxidative-damage cellular death pathway. Cell Rep 3:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chauhan N, Latge JP, Calderone R. 2006. Signalling and oxidant adaptation in Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:435–444. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vabulas RM, Raychaudhuri S, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU. 2010. Protein folding in the cytoplasm and the heat shock response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a004390. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent BM, Lancaster AK, Scherz-Shouval R, Whitesell L, Lindquist S. 2013. Fitness trade-offs restrict the evolution of resistance to amphotericin B. PLoS Biol 11:e1001692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blum G, Kainzner B, Grif K, Dietrich H, Zelger B, Sonnweber T, Lass-Flörl C. 2013. In vitro and in vivo role of heat shock protein 90 in amphotericin B resistance of Aspergillus terreus. Clin Microbiol Infect 19:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutherland A, Ellis D. 2008. Treatment of a critically ill child with disseminated Candida glabrata with a recombinant human antibody specific for fungal heat shock protein 90 and liposomal amphotericin B, caspofungin, and voriconazole. Pediatr Crit Care Med 9:e23–e25. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31817286e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pachl J, Svoboda P, Jacobs F, Vandewoude K, van der Hoven B, Spronk P, Masterson G, Malbrain M, Aoun M, Garbino J, Takala J, Drgona L, Burnie J, Matthews R, Mycograb Invasive Candidiasis Study Group. 2006. A randomized, blinded, multicenter trial of lipid-associated amphotericin B alone versus in combination with an antibody-based inhibitor of heat shock protein 90 in patients with invasive candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis 42:1404–1413. doi: 10.1086/503428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brajtburg J, Elberg S, Kobayashi GS, Medoff G. 1989. Effects of ascorbic acid on the antifungal action of amphotericin B. J Antimicrob Chemother 24:333–337. doi: 10.1093/jac/24.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JH, Faria NC, Martins MDL, Chan KL, Campbell BC. 2012. Enhancement of antimycotic activity of amphotericin B by targeting the oxidative stress response of Candida and Cryptococcus with natural dihydroxybenzaldehydes. Front Microbiol 3:261. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagao J, Cho T, Uno J, Ueno K, Imayoshi R, Nakayama H, Chibana H, Kaminishi H. 2012. Candida albicans Msi3p, a homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sse1p of the Hsp70 family, is involved in cell growth and fluconazole tolerance. FEMS Yeast Res 12:728–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2012.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binder U, Maurer E, Lackner M, Lass-Flörl C. 2015. Effect of reduced oxygen on the antifungal susceptibility of clinically relevant aspergilli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1806–1810. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04204-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reyes G, Romans A, Nguyen CK, May GS. 2006. Novel mitogen-activated protein kinase MpkC of Aspergillus fumigatus is required for utilization of polyalcohol sugars. Eukaryot Cell 5:1934–1940. doi: 10.1128/EC.00178-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arendrup MC, Lass-Flörl C, Hope WW, Howard SJ, Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AFST) of the ESCMID European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). 2014. Method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for conidia forming moulds, EUCAST definitive document EDef 9.2. European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, Basel, Switzerland: http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/AFST/Files/EUCAST-AFST_EDEF_9_2_Mould_testing_20140815.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arendrup MC, Cuenca-Estrella M, Lass-Flörl C, Hope WW, European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing. 2012. EUCAST technical note on Aspergillus and amphotericin B, itraconazole, and posaconazole. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:E248–E250. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing. 2014. Antifungal agents, breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs, version 7.0, valid from 2014-08-12. European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, Basel, Switzerland: http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/AFST/Antifungal_breakpoints_v_7.0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi J, Cheong K, Jung K, Jeon J, Lee GW, Kang S, Kim S, Lee YW, Lee YH. 2013. CFGP 2.0: a versatile web-based platform for supporting comparative and evolutionary genomics of fungi and oomycetes. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D714–D719. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mabey Gilsenan J, Cooley J, Bowyer P. 2012. CADRE: the Central Aspergillus Data REpository 2012. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D660–D666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, McWilliam H, Maslen J, Mitchell A, Nuka G, Pesseat S, Quinn AF, Sangrador-Vegas A, Scheremetjew M, Yong SY, Lopez R, Hunter S. 2014. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McWilliam H, Li W, Uludag M, Squizzato S, Park YM, Buso N, Cowley AP, Lopez R. 2013. Analysis tool web services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W597–W600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altschul SF, Gertz EM, Agarwala R, Schaffer AA, Yu YK. 2009. PSI-BLAST pseudocounts and the minimum description length principle. Nucleic Acids Res 37:815–824. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neron B, Menager H, Maufrais C, Joly N, Maupetit J, Letort S, Carrere S, Tuffery P, Letondal C. 2009. Mobyle: a new full web bioinformatics framework. Bioinformatics 25:3005–3011. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horton P, Park KJ, Obayashi T, Fujita N, Harada H, Adams-Collier CJ, Nakai K. 2007. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res 35:W585–W587. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Claros MG, Vincens P. 1996. Computational method to predict mitochondrially imported proteins and their targeting sequences. Eur J Biochem 241:779–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steel GJ, Fullerton DM, Tyson JR, Stirling CJ. 2004. Coordinated activation of Hsp70 chaperones. Science 303:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1092287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goeckeler JL, Stephens A, Lee P, Caplan AJ, Brodsky JL. 2002. Overexpression of yeast Hsp110 homolog Sse1p suppresses ydj1-151 thermosensitivity and restores Hsp90-dependent activity. Mol Biol Cell 13:2760–2770. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-04-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh HJ, Easton D, Murawski M, Kaneko Y, Subjeck JR. 1999. The chaperoning activity of hsp110. Identification of functional domains by use of targeted deletions. J Biol Chem 274:15712–15718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaner L, Wegele H, Buchner J, Morano KA. 2005. The yeast Hsp110 Sse1 functionally interacts with the Hsp70 chaperones Ssa and Ssb. J Biol Chem 280:41262–41269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503614200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrams JL, Verghese J, Gibney PA, Morano KA. 2014. Hierarchical functional specificity of cytosolic heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) nucleotide exchange factors in yeast. J Biol Chem 289:13155–13167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.530014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gautschi M, Mun A, Ross S, Rospert S. 2002. A functional chaperone triad on the yeast ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:4209–4214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062048599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valiante V, Jain R, Heinekamp T, Brakhage AA. 2009. The MpkA MAP kinase module regulates cell wall integrity signaling and pyomelanin formation in Aspergillus fumigatus. Fungal Genet Biol 46:909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnitz R, Sarg B, Ott HW, Neher A, Lindner H, Nagl M. 2006. Protein sites of attack of N-chlorotaurine in Escherichia coli. Proteomics 6:865–869. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szewczyk E, Nayak T, Oakley CE, Edgerton H, Xiong Y, Taheri-Talesh N, Osmani SA, Oakley BR. 2006. Fusion PCR and gene targeting in Aspergillus nidulans. Nat Protoc 1:3111–3120. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blatzer M, Schrettl M, Sarg B, Lindner HH, Pfaller K, Haas H. 2011. SidL, an Aspergillus fumigatus transacetylase involved in biosynthesis of the siderophores ferricrocin and hydroxyferricrocin. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:4959–4966. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00182-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Punt PJ, van den Hondel CA. 1992. Transformation of filamentous fungi based on hygromycin B and phleomycin resistance markers. Methods Enzymol 216:447–457. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)16041-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuchs BB, O'Brien E, Khoury JB, Mylonakis E. 2010. Methods for using Galleria mellonella as a model host to study fungal pathogenesis. Virulence 1:475–482. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.6.12985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mylonakis E. 2008. Galleria mellonella and the study of fungal pathogenesis: making the case for another genetically tractable model host. Mycopathologia 165:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s11046-007-9082-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly J, Kavanagh K. 2011. Caspofungin primes the immune response of the larvae of Galleria mellonella and induces a non-specific antimicrobial response. J Med Microbiol 60:189–196. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.025494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mesa-Arango AC, Forastiero A, Bernal-Martinez L, Cuenca-Estrella M, Mellado E, Zaragoza O. 2013. The non-mammalian host Galleria mellonella can be used to study the virulence of the fungal pathogen Candida tropicalis and the efficacy of antifungal drugs during infection by this pathogenic yeast. Med Mycol 51:461–472. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.737031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kominek J, Marszalek J, Neuveglise C, Craig EA, Williams BL. 2013. The complex evolutionary dynamics of Hsp70s: a genomic and functional perspective. Genome Biol Evol 5:2460–2477. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hundley H, Eisenman H, Walter W, Evans T, Hotokezaka Y, Wiedmann M, Craig E. 2002. The in vivo function of the ribosome-associated Hsp70, Ssz1, does not require its putative peptide-binding domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:4203–4208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062048399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fang NN, Ng AH, Measday V, Mayor T. 2011. Hul5 HECT ubiquitin ligase plays a major role in the ubiquitylation and turnover of cytosolic misfolded proteins. Nat Cell Biol 13:1344–1352. doi: 10.1038/ncb2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yam AY, Albanese V, Lin HT, Frydman J. 2005. Hsp110 cooperates with different cytosolic HSP70 systems in a pathway for de novo folding. J Biol Chem 280:41252–41261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaner L, Sousa R, Morano KA. 2006. Characterization of Hsp70 binding and nucleotide exchange by the yeast Hsp110 chaperone Sse1. Biochemistry 45:15075–15084. doi: 10.1021/bi061279k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young JC, Agashe VR, Siegers K, Hartl FU. 2004. Pathways of chaperone-mediated protein folding in the cytosol. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:781–791. doi: 10.1038/nrm1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taldone T, Ochiana SO, Patel PD, Chiosis G. 2014. Selective targeting of the stress chaperome as a therapeutic strategy. Trends Pharmacol Sci 35:592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lamoth F, Juvvadi PR, Fortwendel JR, Steinbach WJ. 2012. Heat shock protein 90 is required for conidiation and cell wall integrity in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell 11:1324–1332. doi: 10.1128/EC.00032-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Massey AJ. 2010. ATPases as drug targets: insights from heat shock proteins 70 and 90. J Med Chem 53:7280–7286. doi: 10.1021/jm100342z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yokota S, Kitahara M, Nagata K. 2000. Benzylidene lactam compound, KNK437, a novel inhibitor of acquisition of thermotolerance and heat shock protein induction in human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 60:2942–2948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slater JL, Gregson L, Denning DW, Warn PA. 2011. Pathogenicity of Aspergillus fumigatus mutants assessed in Galleria mellonella matches that in mice. Med Mycol 49(Suppl 1):S107–S113. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.523852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cowen LE, Singh SD, Kohler JR, Collins C, Zaas AK, Schell WA, Aziz H, Mylonakis E, Perfect JR, Whitesell L, Lindquist S. 2009. Harnessing Hsp90 function as a powerful, broadly effective therapeutic strategy for fungal infectious disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:2818–2823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813394106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monma H, Harashima N, Inao T, Okano S, Tajima Y, Harada M. 2013. The HSP70 and autophagy inhibitor pifithrin-μ enhances the antitumor effects of TRAIL on human pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 12:341–351. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaner L, Morano KA. 2007. All in the family: atypical Hsp70 chaperones are conserved modulators of Hsp70 activity. Cell Stress Chaperones 12:1–8. doi: 10.1379/CSC-245R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.