Abstract

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is an urgent public health concern causing considerable clinical and economic burdens. CDI can be treated with antibiotics, but recurrence of the disease following successful treatment of the initial episode often occurs. Surotomycin is a rapidly bactericidal cyclic lipopeptide antibiotic that is in clinical trials for CDI treatment and that has demonstrated superiority over vancomycin in preventing CDI relapse. Surotomycin is a structural analogue of the membrane-active antibiotic daptomycin. Previously, we utilized in vitro serial passage experiments to derive C. difficile strains with reduced surotomycin susceptibilities. The parent strains used included ATCC 700057 and clinical isolates from the restriction endonuclease analysis (REA) groups BI and K. Serial passage experiments were also performed with vancomycin-resistant and vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. The goal of this study is to identify mutations associated with reduced surotomycin susceptibility in C. difficile and enterococci. Illumina sequence data generated for the parent strains and serial passage isolates were compared. We identified nonsynonymous mutations in genes coding for cardiolipin synthase in C. difficile ATCC 700057, enoyl-(acyl carrier protein) reductase II (FabK) and cell division protein FtsH2 in C. difficile REA type BI, and a PadR family transcriptional regulator in C. difficile REA type K. Among the 4 enterococcal strain pairs, 20 mutations were identified, and those mutations overlap those associated with daptomycin resistance. These data give insight into the mechanism of action of surotomycin against C. difficile, possible mechanisms for resistance emergence during clinical use, and the potential impacts of surotomycin therapy on intestinal enterococci.

INTRODUCTION

Clostridium difficile is a Gram-positive anaerobic spore-forming bacterium and a causative agent of health care-associated infections (HAIs). C. difficile infection (CDI; alternatively called C. difficile-associated diarrhea) can occur after disruption of the normal microbiota of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, thereby decreasing colonization resistance and allowing for C. difficile outgrowth (1). Toxin production by C. difficile can lead to severe disease. Over the last two decades, the incidence of CDI has increased dramatically, especially among elderly health care patients (1–3). A recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report on antibiotic resistance threats in the United States classifies C. difficile as an urgent public health threat, as it causes an estimated 250,000 infections per year, leading to an estimated 14,000 deaths and at least $1 billion in medical costs (2).

CDI can be treated with antibiotics, but recurrence can occur after a successful therapy and is a persistent concern (3). Vancomycin, metronidazole, and the recently FDA-approved drug fidaxomicin are used to treat CDI (1, 3, 4). Surotomycin (CB-183,315) is a cyclic lipopeptide antibiotic and daptomycin analogue that is currently in phase 3 clinical trials for CDI treatment. Surotomycin is dosed orally, not absorbed, and rapidly bactericidal against C. difficile (5, 6). Surotomycin is likely to have a mechanism of action similar to that of daptomycin, as treatment with either antibiotic leads to membrane depolarization but not increased membrane permeability in Staphylococcus aureus and C. difficile (6, 7). Importantly, the MIC values of surotomycin for normal GI tract microbiota such as Bacteroides species and enterobacteria are higher than surotomycin concentrations recorded in situ during clinical trials (8). This suggests that surotomycin therapy leaves these commensal populations intact, which could restore colonization resistance and reduce the likelihood of CDI relapses. In accordance with this, surotomycin was superior to vancomycin in CDI recurrence prevention in phase 2 clinical trials (9). Note that although C. difficile is susceptible to daptomycin in vitro (10, 11), the drug is not approved to treat CDI. The oral bioavailability of daptomycin given intravenously is limited, probably due to poor GI permeability (Cubist Pharmaceuticals, unpublished data).

A recent study utilized in vitro serial passage experiments to derive C. difficile strains with reduced surotomycin susceptibilities (5). Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium were also investigated in that study (5). Like C. difficile, enterococci colonize the human GI tract (12), are common causative agents of HAIs (13–15), and are susceptible to surotomycin (5, 16). Further, daptomycin is commonly used to treat difficult enterococcal infections, and several studies have identified genetic variations in enterococci that are associated with reduced daptomycin susceptibility (17). This makes enterococci useful comparators for surotomycin susceptibility studies. Here, we used Illumina sequencing to identify mutations associated with reduced surotomycin susceptibility in C. difficile, E. faecalis, and E. faecium. These data give insight into the mechanism of action of surotomycin against C. difficile, possible mechanisms for resistance emergence during clinical use, and the potential impacts of surotomycin therapy on GI tract enterococci.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Bacterial strains used in this study are shown in Table 1, and their derivation was previously described (5). Parent strains were used as inocula for in vitro serial passage experiments with surotomycin. Pass strains are isolates obtained by colony purification from day 15 of serial passage experiments. Pass strains have decreased susceptibility to surotomycin relative to the parent strains. Prior to genome sequencing, pass strains were passaged three times in drug-free medium and retested for surotomycin susceptibility to ensure stability of the surotomycin MIC. Surotomycin MICs of parent and pass strains are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this studya

| Bacterium and strainb | Description | MIC (μg/ml) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUR | VAN | DAP | FDX | MET | ||

| C. difficile | ||||||

| Cdi2179 (ATCC 700057) | Quality control strain for MIC testing | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Cdi2179 pass | Day 15 serial passage isolate | 8 | 1 | 8 | 0.0625 | 0.25 |

| Cdi2989 | REA type BI isolate from phase 2 clinical trial | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| Cdi2989 pass | Day 15 serial passage isolate | 8 | 1 | 16 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| Cdi2994 | REA type K isolate from phase 2 clinical trial | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 0.0625 | 0.25 |

| Cdi2994 pass | Day 15 serial passage isolate | 4 | 2 | 8 | 0.0625 | 0.25 |

| E. faecalis | ||||||

| Efs201 (ATCC 49452) | VSE | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | NT | NT |

| Efs201 pass | Day 15 serial passage isolate | 2 | 1 | 16 | NT | NT |

| Efs807 (ATCC 700802) | VRE | 1 | 64 | 2 | NT | NT |

| Efs807 pass | Day 15 serial passage isolate | 4 | >64 | 32 | NT | NT |

| E. faecium | ||||||

| Efm14 (ATCC 6569) | VSE | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | NT | NT |

| Efm14 pass | Day 15 serial passage isolate | 8 | 0.25 | 64 | NT | NT |

| Efm277 (ATCC 51559) | VRE | 1 | >64 | 4 | NT | NT |

| Efm277 pass | Day 15 serial passage isolate | 16 | 0.5c | >64 | NT | NT |

Abbreviations: SUR, surotomycin; VAN, vancomycin; DAP, daptomycin; FDX, fidaxomicin; MET, metronidazole; VSE, vancomycin-sensitive Enterococcus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; NT, not tested.

Alternate strain names are shown in parentheses. Pass strains were generated by Mascio et al. (5).

Efm277 became vancomycin sensitive over the course of serial passage (5).

Enterococcal gDNA isolation.

Enterococcal strains were cultured on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar at 37°C, and isolated colonies were used to inoculate BHI broth. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from overnight cultures using a modified version of a previously published protocol (18). Cells were washed once with Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (pH 8.0; 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA) and resuspended in 180 μl enzymatic lysis buffer (pH 8.0; 20 mM Tris-HCl, 2 mM sodium EDTA, 1.2% [vol/vol] Triton X-100) amended with 20 mg/ml lysozyme, 10 μl of a 2.5 kU/ml mutanolysin stock, and 15 μl of a 10 mg/ml preboiled RNase A stock. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 1 to 2 h prior to proteinase K treatment and column purification of gDNA using the Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit per the manufacturer's instructions.

C. difficile gDNA isolation.

C. difficile stocks were passaged once on brucella agar, and a single colony was used to inoculate thioglycolate broth. Liquid cultures were grown for 48 h prior to gDNA extraction using a modified phenol-chloroform prep. Three milliliters culture was split into three 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes and pelleted at 14,000 × g for 2 min. Pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of phosphate-buffered saline and combined into one tube for a second round of centrifugation. The cell pellets were then resuspended in 570 μl of a resuspension buffer (60 μl of 500 mM EDTA, 30 μl of a 20-mg/ml lysozyme stock, 30 μl of a 10-kU/ml mutanolysin stock, 30 μl of a 10-mg/ml lysostaphin stock, 420 μl water). Solutions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and then 30 μl 10% (wt/vol) SDS was added. Solutions were incubated at 37°C for an additional 30 min. An equal volume of TE-saturated phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (Sigma) was added, tubes were mixed by inversion, and aqueous and organic layers were separated by centrifugation. The aqueous fraction was extracted again and then extracted once with chloroform alone. The gDNA was ethanol precipitated and the pellet resuspended in 100 μl of DNA rehydration solution. Prior to Illumina sequencing, C. difficile gDNA samples were treated with RNase A as described above and then treated with proteinase K and column purified using the Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit per the manufacturer's instructions.

Illumina genome sequencing.

Illumina library preparation and sequencing were performed at the Tufts University DNA Core Facility. All gDNA samples were treated as low-abundance samples, and libraries were prepared using the NuGen Ovation Ultralow DR Multiplex System 1-96 kit. The average library fragment size was ∼390 bp, with high variability in fragment sizes due to low DNA inputs. Libraries were multiplexed and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2500, yielding paired reads of 151 × 2 bases. Single-end (SE) reads were used for analysis.

Mutation detection in pass genomes.

SE reads from parent strains were assembled into draft contigs using CLC Genomics Workbench default parameters. Contigs were annotated using the Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) server with default parameters (rast.nmpdr.org) (19, 20). Draft genome assemblies are summarized in Table S1 in the supplemental material. SE reads from pass strains were mapped to RAST-annotated parent assemblies using CLC Genomics Workbench with default mapping parameters. Sequence variations were identified using the “Quality-based variant detection” tool in CLC Genomics Workbench with default parameters (≥10-fold coverage of the reference position and sequence variation in ≥35% of mapped reads). All variations were manually analyzed. All variations that fell within two read lengths (300 bp) from a contig end were removed from consideration. Next, the variant frequency was considered. All sequence variations occurring with a frequency of ≥90% (occurring in ≥90% of mapped reads) were confirmed to be true mutations by additional PCR and Sanger sequencing (discussed below). For variations occurring with <90% frequency, parent and pass strain read assemblies were manually inspected. If sequence variation was observed in the pass but not parent strain assembly, PCR and additional Sanger sequencing were performed. In all instances, either these were found to not be true sequence variations or sequence heterogeneity occurred in both parent and pass strains (data not shown). Finally, the “Find low coverage” tool in CLC Genomics Workbench was used to identify regions of zero coverage in pass strain read mappings, which represent possible large deletions. These regions were manually inspected, and PCR and additional Sanger sequencing were performed where appropriate.

Analysis of Efs807 sequence reads.

A complete reference sequence is available for Efs807 (V583) (21). Single-end reads from the Efs807 parent and pass samples were mapped to the Efs807 chromosome (GenBank accession number AE016830) and three plasmids (pTEF1, GenBank accession number AE016833; pTEF2, GenBank accession number AE016831; and pTEF3, GenBank accession number AE016832) using CLC Genomics Workbench with default mapping parameters. Read assemblies are summarized in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Sequence variations were identified using the “Quality-based variant detection” tool in CLC Genomics Workbench with default parameters as described above. Variants occurring in nonspecific regions of the read assemblies (rRNA operons, insertion sequences, etc.) were ignored. Previously described sequence variations occurring in the Efs807 parent strain relative to the GenBank reference (22) were removed from analysis.

Confirmation of mutations.

Primers were designed to amplify genomic regions that included putative mutations. Primers used are shown in Table S3 in the supplemental material. gDNA was used as the template for a 50-μl PCR volume with Phusion polymerase (Fermentas). Reactions were performed for parent and pass strains to confirm absence of variation in the parent strains. PCR products were purified with the Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and sequenced at the Massachusetts General Hospital DNA Core Facility (Boston, MA).

Bioinformatic analyses of candidate genes.

Transmembrane helices were predicted by TMHMM, version 2.0 (23). Subcellular location was predicted by Psortb, version 3.0 (24). RNA secondary structure prediction was from RNAfold (25). Pfam 27.0 (26) and NCBI Conserved Domains were used for analysis of conserved protein domains and for substrate-binding and catalytic sites. C. difficile 630 (27, 28), E. faecalis V583 (21, 29), and E. faecium DO (30) are commonly used model strains, and we identified homologues of our genes of interest in those strains using NCBI BLAST (Table 2; see also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). For consistency with existing literature on C. difficile 630, in the text we express locus identifiers in the “CD####” format.

TABLE 2.

Mutations occurring in surotomycin serial passage strainsa

| Bacterium and strain | Description of gene | Nucleotide variation in gene (frequency of variation in assembly)b | Amino acid change in predicted protein | Best BLASTP hit in reference genomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. difficile | ||||

| Cdi2179 pass | Cardiolipin synthase | G235A (599/603) | D79N | CD3404 Cls |

| Cdi2989 pass | Enoyl-ACP reductase | G434T (849/850) | G145V | CD1180 FabK |

| Cell division protein FtsH | G1387T (868/868) | E463Stop | CD3559 FtsH2 | |

| Cdi2994 pass | Transcriptional regulator PadR | G17T (102/102) | R6I | CD1345 |

| E. faecium | ||||

| Efm14 pass | HD family hydrolase | 29–39del | E10fs | HMPREF0351_11908; EF2470 |

| Aminopeptidase S | C1065A (826/828) | F355L | HMPREF0351_10886 | |

| ATP-dependent nuclease subunit A | C2283G (776/777) | H761Q | HMPREF0351_11280 AddA; EF1113 RexA | |

| Alpha/beta family hydrolase | C582T (788/789) | Silent | HMPREF0351_11299; EF1536 | |

| Hypothetical protein | A165G (828/830) | Silent | HMPREF0351_11264 | |

| Intergenic region between two glycosyltransferase genes | C → G (631/631) | NAd | HMPREF0351_10908- HMPREF0351_10909 | |

| Intergenic region upstream of catabolite control protein A | T → A (443/444) | NA | HMPREF0351_12002 CcpA | |

| Efm277 pass | Cardiolipin synthase | G632T (345/350) | R211L | HMPREF0351_11068 Cls; EF0631 Cls |

| HD family hydrolase | 159delA (132/136) | A53fs | HMPREF0351_11908; EF2470 | |

| Ribosomal large subunit methyltransferase A | G801T (160/160) | K267N | HMPREF0351_12412 RrmA; EF2666 RrmA | |

| RNA polymerase, beta subunit | T2789G (661/670) | V930G | HMPREF0351_12666 RpoB; EF3238 RpoB | |

| Lead, cadmium, zinc, mercury transporting ATPase | C552G (199/203) | F184L | HMPREF0351_11880 CopB; EF0875 | |

| Sucrose-6-phosphate hydrolase | C700A (260/273) | P234T | Not present in E. faecium DO; EFA0069 ScrB-2 | |

| Intergenic region upstream of putative phage repressor | GA → AG (105/105) | NA | Not present in E. faecium DO; Efm408 EFUG_02666 | |

| E. faecalis | ||||

| Efs201 pass | Sensor histidine kinase LiaS | G330A (1115/1117) | M110I | EF2912c |

| Fe-S cluster binding subunit | G509T (849/868) | G170V | EF1109 | |

| Efs807 pass | EF0797 hypothetical protein | T155C (715/718) | L52P | EF0797 |

| EF1027 MprF2 | G85A (485/486) | A29T | EF1027 MprF2 | |

| EF1797 hypothetical protein (DrmA) | 449delA (565/608) | N150fs | EF1797 DrmA | |

| Intergenic region downstream of EF1367 | 31-bp del | NA | EF1367 |

Boldface indicates that the gene or pathway has been associated with daptomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, and/or Staphylococcus aureus. See the text and Data Set S1A in the supplemental material for extended analysis.

Shown in parentheses are raw sequence variation data from pass strain read assemblies, indicating the number of mapped reads with indicated sequence variation/total coverage at that position. del, deletion.

The Efs201 LiaS protein is N-terminally truncated relative to the V583 LiaS protein. See Data Set S2 in the supplemental material for the Efs201 LiaS sequence.

NA, not applicable.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequence reads generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive, and the accession numbers can be found via BioProject record number PRJNA281633.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Strains used for Illumina sequencing analysis.

In a previous study, C. difficile, E. faecalis, and E. faecium strains were serially passaged in broth in the presence of surotomycin for a period of 15 days (5). The protocol for and results of the serial passage experiments were previously reported (5). C. difficile strains used in passage experiments included an American Type Culture Collection quality control strain (ATCC 700057; referred to as Cdi2179 in this study) and two clinical isolates obtained during the phase 2 dose-ranging study (LCD-DR-09-03) (9). One clinical isolate (Cdi2989) is from the restriction endonuclease analysis (REA) type BI, representing the epidemic C. difficile strain (1, 3), and the other (Cdi2994) is REA type K. Vancomycin-resistant and vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis and E. faecium strains obtained from the ATCC were similarly used as parents for serial passage (Table 1). For genome sequencing, a single colony isolate obtained from each serial passage culture at day 15 was passaged three times in drug-free medium and then retested for surotomycin MIC to confirm stable reduced susceptibility to the drug. We refer to these strains as pass strains (Table 1). Note that strains with other genotypes may have coexisted in the day 15 serial passage cultures (i.e., representing other mutational paths to reduced surotomycin susceptibility). Therefore, our selection of only a single isolate from each serial passage experiment for genome sequencing is a possible limitation of our study.

MIC data for parent and pass strains are shown in Table 1. Susceptibility to ampicillin and rifampin was not affected in pass strains (data not shown). For all strain pairs, pass strains have elevated surotomycin and daptomycin MICs relative to their parents.

To identify mutations occurring in pass strains, we generated Illumina sequence data from genomic DNA isolated from parent and pass strains. Draft genome assemblies were generated for the parent strains (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and sequence reads obtained for pass strains were mapped to the draft parent assemblies to identify sequence variations. Because a complete reference genome is available for the vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis strain Efs807 (also called V583) (21, 29), Efs807 parent and pass sequence reads were mapped to the existing GenBank reference sequence (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). For all genome comparisons, candidate mutations identified from read assemblies were confirmed to be true mutations by independent Sanger sequencing. Data are summarized in Table 2 (see also Data Set S1A in the supplemental material), and gene and protein sequences of interest are in Data Set S2 in the supplemental material. To facilitate comparisons with the laboratory model strains C. difficile 630 (27, 28), E. faecalis V583 (21, 29), and E. faecium DO (30), NCBI BLAST was used to identify orthologues of genes of interest in those strains (Table 2; see also Data Set S1A and B in the supplemental material).

Mutations associated with reduced surotomycin susceptibility in C. difficile.

Mutations in cls (encoding cardiolipin synthase), fabK (encoding enoyl-ACP reductase II, where ACP is acyl carrier protein), ftsH2 (encoding ATP-dependent membrane-bound metalloprotease), and a gene encoding a PadR family transcriptional regulator were detected among the C. difficile surotomycin pass strains (Table 2).

Cdi2179 pass.

The Cdi2179 pass strain has a surotomycin MIC of 8 μg/ml, a 16-fold increase over that of the parent (Table 1). A G-to-A transition was detected in a gene coding for a predicted cardiolipin synthase (Cls; TIGR04265 bac_cardiolipin family; E value, 2.72e−117). This mutation results in a D79N substitution in the Cls protein. Cls proteins synthesize cardiolipin (bisphosphatidylglycerol), a phospholipid that is enriched in septal and polar regions of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial cells (31–33). As expected for a Cls protein, two catalytic HKD (phospholipase D) motifs are present in the Cdi2179 Cls, as are two predicted N-terminal transmembrane helices (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The D79N substitution in the Cdi2179 pass strain Cls occurs outside transmembrane helix 2, between the helix and HKD motif 1. This substitution may result in altered synthesis and/or localization of cardiolipin in the C. difficile membrane. No C. difficile strains currently deposited in GenBank possess the D79N substitution in Cls.

Mutations in cls have been detected in daptomycin-resistant E. faecalis, E. faecium, and S. aureus strains (22, 34–39; see also a summary in Data Set S1A in the supplemental material). The fact that a cls mutation arose in Cdi2179 during surotomycin exposure suggests that commonalities exist in the way the two drugs interact with cell surfaces and/or in the ways that cells cope with stresses imposed by these drugs.

Cdi2989 pass.

The Cdi2989 pass strain has a surotomycin MIC of 8 μg/ml, a 16-fold increase over that of the parent. The Cdi2989 pass strain possesses two G-to-T transversions. The first occurs in a gene coding for a predicted enoyl-ACP reductase II (TIGR03151 enACPred_II family; E value, 1.3e−142), resulting in a G145V substitution in the protein. The second is a nonsense mutation occurring in a gene coding for the membrane-bound metalloprotease FtsH (TIGR01241 FtsH_fam; E value, 0).

The enoyl-ACP reductase proteins FabK and FabI catalyze the final step in the bacterial type II fatty acid elongation cycle (40, 41). FabI is highly conserved among many bacteria; however, some bacteria lack FabI and instead possess FabK (42, 43). FabK and FabI are distinct in sequence (41), and the enoyl-ACP reductase identified in the Cdi2989 pass strain belongs to the FabK family. C. difficile does not possess fabI (see Data Set S1B in the supplemental material); therefore, fabK is likely to be an essential gene in C. difficile. The fabK gene is significantly upregulated (4-fold) in C. difficile 630 during growth with subinhibitory amoxicillin (44).

FabK utilizes flavin mononucleotide (FMN) as a cofactor and NADH as an electron donor (42) and is similar in sequence to members of the 2-nitropropane dioxygenase-like enzyme family (41). Using the 2-nitropropane dioxygenase-like proteins as references, we used conserved domain analysis to map FMN-binding residues and a catalytic site to the Cdi2989 FabK sequence (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The G145V substitution in the Cdi2989 pass strain occurs near the putative catalytic site of the enzyme (at position H143). The G145V substitution could alter FabK activity and membrane fatty acid composition in the Cdi2989 pass strain.

The second mutation in the Cdi2989 pass strain occurs in a gene annotated as ftsH2 in C. difficile 630 (Table 2; see also Data Set S1A in the supplemental material). The ftsH2 gene was reported to be significantly upregulated (1.5-fold) in C. difficile 630 cells during growth with subinhibitory levels of either amoxicillin or metronidazole (44). FtsH is essential for Escherichia coli, in which it is important for turnover of misfolded membrane proteins, among other functions (45). Less is known about its function in Gram-positive bacteria. In Bacillus subtilis and Lactobacillus plantarum, ftsH is nonessential, but inactivation has a number of effects on the cell, including a reduced ability to cope with extracellular stresses (46, 47) and filamentous growth and a sporulation defect in B. subtilis (47). In B. subtilis, deletion of ftsH leads to induction of the σw regulon, which is involved in extracytoplasmic stress response (48).

For Cdi2989 FtsH2, two N-terminal transmembrane helices, an AAA domain (ATPase family associated with various cellular activities; E value, 1.5e−42), and a peptidase domain (peptidase_M41; E value, 5.7e−77) are predicted (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The protease active-site motif HEXXH (45) is present. The ftsH2 mutation in the Cdi2989 pass strain generates a premature stop codon and a 194-amino-acid C-terminal truncation of the FtsH2 protein. The premature stop codon occurs within the peptidase domain of FtsH2, after the HEXXH motif. This inactivating mutation could lead to pleiotropic effects on C. difficile.

Three observations link FtsH to mechanisms associated with reduced daptomycin (and now, surotomycin) susceptibility. First, FtsH is localized to the division septum in B. subtilis (49). Second, YvlB is among the proteins produced in elevated amounts in a B. subtilis ftsH mutant (48); frameshift mutations in the yvlB homologue in E. faecalis, EF1753, are present in daptomycin-resistant E. faecalis strains (22, 35). Finally, L. plantarum ftsH mutant and overexpression strains have an altered surface charge relative to that of the wild type (46). All of these observations suggest that FtsH has roles in division septum architecture, surface charge modulation, and/or phospholipid metabolism in Gram-positive bacteria.

Since the Cdi2989 parent strain was a clinical isolate (5), it is possible that mutations identified in the Cdi2989 pass strain are actually reversion mutations that occurred as a result of in vitro growth (i.e., they could be unrelated to surotomycin exposure). The fabK mutation in the Cdi2989 pass strain is unlikely to be a reversion, since C. difficile strains currently deposited in GenBank, like the Cdi2989 parent strain, possess G145 in orthologues of FabK. Similarly, truncated FtsH2 proteins are not encoded by C. difficile GenBank strains.

Cdi2994 pass.

The Cdi2994 pass strain has a surotomycin MIC of 4 μg/ml, an 8-fold increase over that of the parent. The Cdi2994 pass strain possesses a G-to-T transversion in a gene coding for a predicted PadR family transcriptional regulator (Pfam E value, 2.1e−20), resulting in an R6I substitution in the protein. To distinguish this protein from the three other PadR family transcriptional regulators encoded by C. difficile, we have named this protein SurR. The mutation in surR does not appear to be a reversion, since C. difficile strains currently deposited in GenBank possess R6 in orthologues of SurR.

PadR-like transcriptional regulators are widespread in bacteria, but few have been experimentally characterized (reviewed by Fibriansah et al. [50]). These proteins possess an N-terminal winged helix-turn-helix (wHTH) DNA binding domain and a C-terminal domain of variable size that participates in dimerization. A model PadR family transcriptional regulator is Lactococcus lactis LmrR (51). LmrR represses expression of lmrCD genes, which are cotranscribed with lmrR (52, 53) and encode an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transport system that confers multidrug resistance (52–54). Mutations in lmrR can lead to constitutive lmrCD expression and multidrug resistance (54). Crystal structures are available for LmrR (51) and for two Bacillus cereus PadR-like regulator proteins, which also regulate proximally borne genes with likely roles in drug transport (50). Cdi2994 SurR is shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material with the predicted wHTH DNA binding domain mapped. The R6I substitution in the Cdi2994 pass strain occurs just within the wHTH domain. This position was identified as being important for protein dimerization in B. cereus PadR-like regulators (50). The R6I substitution in SurR may lead to derepression of genes in the SurR regulon.

Based on bioinformatic analysis, we hypothesize that SurR regulates the expression of itself and two downstream genes, as well as a predicted diacylglycerol glucosyltransferase gene that is divergently transcribed from surR. The organization of this region is identical in Cdi2994 and C. difficile 630. In C. difficile 630, CD1345 encodes SurR, CD1346 encodes a predicted membrane protein possessing three central transmembrane helices (RhaT family; E value, 2.04e−3), and CD1347 encodes a predicted membrane protein with a single N-terminal transmembrane helix. No intergenic regions are present between these genes, suggesting that they are cotranscribed. The surR gene is divergently transcribed from CD1344, which encodes a predicted diacylglycerol glucosyltransferase (PRK13609; E value, 9.67e−49). Because C. difficile 630 produces a number of glycolipids (55), this provides a potential link between SurR and membrane structure and biogenesis. Global gene expression comparisons between the Cdi2994 parent and pass strains as well as specific investigation of the CD1344 gene would be of interest for future studies.

Enterococci with reduced surotomycin susceptibilities.

Each of the four enterococcal surotomycin pass strains possesses a mutation in at least one gene previously associated with daptomycin resistance (Table 2; see also Data Set S1A in the supplemental material). The locations of amino acid substitutions in enterococcal proteins are shown in Fig. S2 to S5 in the supplemental material. Because Efs807 (V583) has been used previously for the selection of daptomycin-resistant derivatives (22), we discuss this model strain in depth.

Efs807 pass.

The Efs807 pass strain has a surotomycin MIC of 4 μg/ml, a 4-fold increase over that of the parent. Three nonsynonymous mutations and a 31-bp deletion in an intergenic region were identified for this strain. Mutations occur in mprF2 and drmA (EF1797), each of which has been associated with daptomycin resistance (22, 35, 37, 56) (see Data Set S1A in the supplemental material).

EF1797 encodes a predicted membrane protein for which a biochemical function is unknown. In previous work (22), three daptomycin-resistant derivatives of Efs807 were generated by serial passage, and each was found to possess mutations in EF1797. The Efs807 surotomycin pass strain possesses a predicted frameshift (N150fs) in EF1797 (Table 2). An N150fs was recently reported for an E. faecalis daptomycin-adapted strain (35). Collectively, mutations identified in EF1797 from daptomycin and surotomycin studies localize a region of interest in the protein: the QKNKNL sequence occurring between the predicted transmembrane helices 4 and 5 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). As a result of the frameshift mutation in the Efs807 surotomycin pass strain, the amino acid sequence occurring between predicted TM helices 4 and 5 is QKIKTF. EF1797 has a limited phylogenetic distribution (22) and does not occur in C. difficile (see Data Set S1A in the supplemental material).

MprF in S. aureus catalyzes the addition of lysine to phosphatidylglycerol moieties, thereby mitigating the negative charge of the outer surface of the cytoplasmic membrane (57). Mutations in mprF are associated with daptomycin resistance emergence in S. aureus (37, 56, 58), are sufficient for daptomycin resistance (59), and confer gain of function (59, 60). Enterococcal MprF2 has an expanded substrate range compared to S. aureus MprF, producing lysine-, alanine-, and arginine-modified phosphatidylglycerol moieties (61, 62). The A29T substitution in the Efs807 pass strain occurs within the first predicted transmembrane helix of MprF2 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In S. aureus, the N-terminal transmembrane helices of MprF are required for translocation of the modified lipid from the inner to outer membrane leaflet (63). The A29T substitution in E. faecalis MprF2 could impact phospholipid flipping. MprF is not encoded by C. difficile (see Data Set S1A in the supplemental material).

The other two mutations occurring in the Efs807 pass strain are in the EF0797 open reading frame (ORF) and in the intergenic region downstream of the EF1367 ORF. EF0797 encodes a predicted hypothetical protein in E. faecalis V583. Conserved domain analysis did not yield clues to its function. Analysis with Psortb failed to resolve a predicted cellular location for the EF0797 protein; however, one N-terminal transmembrane helix is predicted by TMHMM (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The amino acid substitution (L52P) in the Efs807 pass strain occurs in a predicted extracellular region. The EF0797 orthologue in E. faecalis OG1RF is upregulated in cells treated with 1.25× MIC levels of the antibiotics ampicillin, bacitracin, cephalothin, or vancomycin, and deletion of EF0797 led to an increase in virulence in a Galleria mellonella infection model (64). EF0797 may be involved in stress response to cell wall-active antimicrobials. EF0797 is not encoded by C. difficile (see Data Set S1A in the supplemental material).

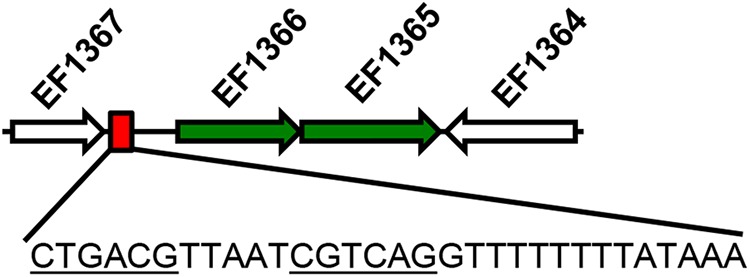

A 31-bp deletion occurs in the Efs807 pass genome, downstream of the EF1367 gene (Fig. 1). EF1367 encodes a cold shock domain-containing protein (65). RNAfold analysis of the deleted 31-bp sequence revealed that the sequence is likely a Rho-independent terminator for EF1367. Deletion of the EF1367 transcription terminator may result in increased expression of the downstream genes EF1366 and EF1365, which are likely cotranscribed (16-bp intergenic region between the two genes). The EF1366 protein possesses six predicted transmembrane helices and a C-terminal YdcF-like domain (E value, 8.86e−40). Conserved domain analysis indicates that this protein may be involved in cell wall synthesis. The EF1365 protein possesses eight predicted transmembrane helices, and its function is unknown.

FIG 1.

Deleted region in Efs807 (V583) pass strain. A region of the E. faecalis V583 genome encompassing ORFs EF1364 to EF1367 is shown. The figure is not drawn to scale. As described in the text, EF1367 encodes a predicted cold shock protein. EF1366 and EF1365 encode two membrane proteins of unknown function. The red box indicates where the 31-bp deletion in the Efs807 pass strain occurs. The deleted sequence is shown. The underlined sequence could base pair in mRNA to form a stem-loop structure.

Summary and implications.

Surotomycin, like daptomycin, dissipates the membrane potential of S. aureus and C. difficile (6, 7). A recently proposed model for daptomycin's mechanism of action (66) posits that at sub-MIC levels and in the presence of phosphatidylglycerol and calcium, daptomycin inserts into the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane and aggregates. This process alters the local curvature of the outer leaflet, to which the cell responds by making compensatory changes in the inner leaflet, potentially including increased cardiolipin content. Cell division proteins and other proteins responsive to membrane ultrastructure changes are recruited to these sites, resulting in aberrant septation. At supra-MIC daptomycin levels, many of these sites are generated, and the cell is not able to mitigate the stress imposed on the membrane. This leads to dissipation of the membrane potential, among other deleterious effects, and ultimately cell death. Additional mechanistic experiments with surotomycin and C. difficile will be required to determine whether surotomycin has similar phospholipid dependencies and impacts on membrane ultrastructure.

Daptomycin resistance is an active area of research. Most studies have focused on S. aureus, B. subtilis, E. faecium, and E. faecalis. Many different adaptive paths to resistance have been discovered for these species, and a few mechanistic models for resistance have been proposed and are well supported by experimental data (reviewed recently by Humphries et al. [17]). Collectively, many of these data indicate that modulation of membrane phospholipid content and localization (especially relative to the division septum and other sites of membrane curvature), cell surface charge, and the transcriptional networks responding to cell surface stress are each involved in daptomycin resistance. For enterococci, a recently proposed model by Tran et al. (67) centers on the LiaFSR signal transduction system and its regulon. In B. subtilis, this system perceives stress imposed by cell wall-active antimicrobials, resulting in differential expression of genes in the LiaR regulon (68–70). Mutations in liaFSR genes are frequently detected in daptomycin-resistant enterococci (34, 35, 71, 72), and the LiaFSR system is activated and protective of B. subtilis in the presence of daptomycin (73). In the study by Tran et al., a liaF mutation in E. faecalis led to redistribution of cardiolipin and diversion of daptomycin away from the division septum, resulting in low-level daptomycin resistance (67). The underlying mechanism for this is likely dysregulation of as-yet-unknown genes in the LiaR regulon of E. faecalis. Additional mutations in cls and gdpD (encoding glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase) further increased the daptomycin MIC and altered the membrane phospholipid content of the cell (67). In this study, we detected a liaS mutation in an E. faecalis strain with reduced surotomycin susceptibility (Table 2).

C. difficile possesses unique attributes that distinguish it from the species described above. First, the membrane structure of C. difficile appears to be distinct. C. difficile 630, like other clostridia (74), possesses membrane phospholipids with plasmalogen (having an ether, instead of ester, linkage at the sn-1 position of glycerol) fatty acid tails (55). C. difficile 630 produces phosphatidylglycerol, cardiolipin, and monohexosyldiradylglycerol lipids of both plasmalogen and di- or tetra-acyl forms (55). The relative ratios of these lipids are likely to impact C. difficile membrane fluidity, and the ratios may change in response to fluctuations in growth environment or in times of stress (55). Whether these lipids are differentially distributed in the C. difficile membrane is unknown. The genes required for clostridial plasmalogen biosynthesis have not been identified (74). Overall, the literature on C. difficile membrane structure and composition is very limited (55, 75). While relevant for our surotomycin discussion, this also highlights a critical gap in knowledge about C. difficile physiology that is relevant to future drug development.

Other attributes that distinguish C. difficile from daptomycin resistance model species are that C. difficile lacks MprF and LiaF (see Data Set S1B in the supplemental material). The absence of MprF suggests that C. difficile does not produce amino-acid-modified phospholipids, although this cannot be formally excluded using existing literature. Of note, an unusual amino-containing glycolipid has been identified in a study involving C. difficile 630, which the authors suggested could counterbalance the negative charges of phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin (55). The absence of LiaF suggests that information on cell surface stress in C. difficile is transduced to the transcriptional machinery of the cell by a distinct mechanism. Proteins with identity to LiaSR, VraSR, and YycFG, each of interest for daptomycin resistance in other species (17), were identified in C. difficile 630 (see Data Set S1B in the supplemental material) but were not altered in the surotomycin passage strains studied here.

For each of the three C. difficile strain pairs studied here, mutations arose in genes with probable or potential roles in C. difficile membrane structure and biogenesis (cls, fabK, and surR). Allelic replacement studies will ultimately be required to confirm whether the mutations detected are responsible for surotomycin MIC increases.

For the enterococci studied here, each surotomycin pass strain possessed at least one mutation that also occurs in daptomycin-resistant strains (Table 2), and the pass strains have elevated daptomycin MICs (Table 1). This suggests that enterococcal strains with elevated daptomycin MICs could be cross-resistant to surotomycin, allowing for their outgrowth in the GI tract during surotomycin therapy for CDI. Alternatively, surotomycin therapy for CDI could select for daptomycin resistance-conferring mutations in GI tract enterococci. These possibilities should be evaluated with further in vitro and in vivo studies. We note also that isolates with high (128- to 256-fold) increases in daptomycin MICs emerged in daptomycin serial passage experiments with the vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) species strain Efs807 (22). Here, a relatively modest (4-fold) increase in surotomycin MIC was observed for the same parent strain over a similar period of passage. These differing results may be related to the oxygen status of E. faecalis in the serial passage experiments. Surotomycin passage experiments were performed under anaerobic conditions (5), while daptomycin passage experiments were performed under oxygenated conditions (22). Interestingly, a recent metabolomic study found that E. faecalis membrane fatty acid content varies with oxygen status (76). Further investigation of enterococcal membrane physiology under various oxygen tensions could be informative for surotomycin and daptomycin studies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Anu Daniel and Jared Silverman of Cubist Pharmaceuticals for helpful discussions and Wenwen Huo for assistance with submission of sequence data to the Sequence Read Archive.

This work was supported by a Cubist Pharmaceuticals Sponsored Research Agreement to K.L.P.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00526-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rupnik M, Wilcox MH, Gerding DN. 2009. Clostridium difficile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:526–536. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013 Accessed 17 December 2014.

- 3.Kelly CP, LaMont JT. 2008. Clostridium difficile—more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med 359:1932–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghose C. 2013. Clostridium difficile infection in the twenty-first century. Emerg Microbes Infect 2:e62. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mascio CT, Chesnel L, Thorne G, Silverman JA. 2014. Surotomycin demonstrates low in vitro frequency of resistance and rapid bactericidal activity in Clostridium difficile, Enterococcus faecalis, and Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3976–3982. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00124-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mascio CT, Mortin LI, Howland KT, Van Praagh AD, Zhang S, Arya A, Chuong CL, Kang C, Li T, Silverman JA. 2012. In vitro and in vivo characterization of CB-183,315, a novel lipopeptide antibiotic for treatment of Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:5023–5030. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00057-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alam MZ, Wu X, Mascio C, Chesnel L, Hurdle JG. 2014. Mode of action and bactericidal properties of surotomycin against growing and non-growing Clostridium difficile, abstr C-170 Abstr 54th Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother (ICAAC). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Citron DM, Tyrrell KL, Merriam CV, Goldstein EJ. 2012. In vitro activities of CB-183,315, vancomycin, and metronidazole against 556 strains of Clostridium difficile, 445 other intestinal anaerobes, and 56 Enterobacteriaceae species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1613–1615. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05655-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patino H, Stevens C, Louie T, Bernado P, Friedland I. 2011. Efficacy and safety of the lipopeptide CB-183,315 for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection, abstr K-205a Abstr 51st Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyrrell KL, Citron DM, Warren YA, Fernandez HT, Merriam CV, Goldstein EJ. 2006. In vitro activities of daptomycin, vancomycin, and penicillin against Clostridium difficile, C. perfringens, Finegoldia magna, and Propionibacterium acnes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2728–2731. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00357-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu X, Cherian PT, Lee RE, Hurdle JG. 2013. The membrane as a target for controlling hypervirulent Clostridium difficile infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:806–815. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebreton F, Willems RJL, Gilmore MS. 2014. Enterococcus diversity, origins in nature, and gut colonization. In Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N (ed), Enterococci: from commensals to leading causes of drug resistant infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A, Kallen A, Limbago B, Fridkin S, National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Team and Participating NHSN Facilities. 2013. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 34:1–14. doi: 10.1086/668770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidron AI, Edwards JR, Patel J, Horan TC, Sievert DM, Pollock DA, Fridkin SK, National Healthcare Safety Network T, Participating National Healthcare Safety Network Facilities. 2008. NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006-2007. Infect Control Hospital Epidemiol 29:996–1011. doi: 10.1086/591861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, Lynfield R, Maloney M, McAllister-Hollod L, Nadle J, Ray SM, Thompson DL, Wilson LE, Fridkin SK, Emerging Infections Program Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use Prevalence Survey Team. 2014. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med 370:1198–1208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snydman DR, Jacobus NV, McDermott LA. 2012. Activity of a novel cyclic lipopeptide, CB-183,315, against resistant Clostridium difficile and other Gram-positive aerobic and anaerobic intestinal pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3448–3452. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06257-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humphries RM, Pollett S, Sakoulas G. 2013. A current perspective on daptomycin for the clinical microbiologist. Clin Microbiol Rev 26:759–780. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00030-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manson JM, Keis S, Smith JMB, Cook GM. 2003. A clonal lineage of VanA-type Enterococcus faecalis predominates in vancomycin-resistant enterococci isolated in New Zealand. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:204–210. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.204-210.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. 2008. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, Disz T, Edwards RA, Gerdes S, Parrello B, Shukla M, Vonstein V, Wattam AR, Xia F, Stevens R. 2014. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res 42:D206–D214. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paulsen IT, Banerjei L, Myers GS, Nelson KE, Seshadri R, Read TD, Fouts DE, Eisen JA, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF, Tettelin H, Dodson RJ, Umayam L, Brinkac L, Beanan M, Daugherty S, DeBoy RT, Durkin S, Kolonay J, Madupu R, Nelson W, Vamathevan J, Tran B, Upton J, Hansen T, Shetty J, Khouri H, Utterback T, Radune D, Ketchum KA, Dougherty BA, Fraser CM. 2003. Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science 299:2071–2074. doi: 10.1126/science.1080613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer KL, Daniel A, Hardy C, Silverman J, Gilmore MS. 2011. Genetic basis for daptomycin resistance in enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3345–3356. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00207-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu NY, Wagner JR, Laird MR, Melli G, Rey S, Lo R, Dao P, Sahinalp SC, Ester M, Foster LJ, Brinkman FS. 2010. PSORTb 3.0: improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics 26:1608–1615. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Honer Zu Siederdissen C, Tafer H, Flamm C, Stadler PF, Hofacker IL. 2011. ViennaRNA package 2.0. Algorithms Mol Biol 6:26. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, Heger A, Holm L, Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Finn RD. 2012. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sebaihia M, Wren BW, Mullany P, Fairweather NF, Minton N, Stabler R, Thomson NR, Roberts AP, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Wang H, Holden MT, Wright A, Churcher C, Quail MA, Baker S, Bason N, Brooks K, Chillingworth T, Cronin A, Davis P, Dowd L, Fraser A, Feltwell T, Hance Z, Holroyd S, Jagels K, Moule S, Mungall K, Price C, Rabbinowitsch E, Sharp S, Simmonds M, Stevens K, Unwin L, Whithead S, Dupuy B, Dougan G, Barrell B, Parkhill J. 2006. The multidrug-resistant human pathogen Clostridium difficile has a highly mobile, mosaic genome. Nat Genet 38:779–786. doi: 10.1038/ng1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monot M, Boursaux-Eude C, Thibonnier M, Vallenet D, Moszer I, Medigue C, Martin-Verstraete I, Dupuy B. 2011. Reannotation of the genome sequence of Clostridium difficile strain 630. J Med Microbiol 60:1193–1199. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.030452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahm DF, Kissinger J, Gilmore MS, Murray PR, Mulder R, Solliday J, Clarke B. 1989. In vitro susceptibility studies of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 33:1588–1591. doi: 10.1128/AAC.33.9.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin X, Galloway-Pena JR, Sillanpaa J, Roh JH, Nallapareddy SR, Chowdhury S, Bourgogne A, Choudhury T, Muzny DM, Buhay CJ, Ding Y, Dugan-Rocha S, Liu W, Kovar C, Sodergren E, Highlander S, Petrosino JF, Worley KC, Gibbs RA, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. 2012. Complete genome sequence of Enterococcus faecium strain TX16 and comparative genomic analysis of Enterococcus faecium genomes. BMC Microbiol 12:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernal P, Munoz-Rojas J, Hurtado A, Ramos JL, Segura A. 2007. A Pseudomonas putida cardiolipin synthesis mutant exhibits increased sensitivity to drugs related to transport functionality. Environ Microbiol 9:1135–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumoto K, Kusaka J, Nishibori A, Hara H. 2006. Lipid domains in bacterial membranes. Mol Microbiol 61:1110–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawai F, Shoda M, Harashima R, Sadaie Y, Hara H, Matsumoto K. 2004. Cardiolipin domains in Bacillus subtilis Marburg membranes. J Bacteriol 186:1475–1483. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.5.1475-1483.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arias CA, Panesso D, McGrath DM, Qin X, Mojica MF, Miller C, Diaz L, Tran TT, Rincon S, Barbu EM, Reyes J, Roh JH, Lobos E, Sodergren E, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Quinn JP, Shamoo Y, Murray BE, Weinstock GM. 2011. Genetic basis for in vivo daptomycin resistance in enterococci. N Engl J Med 365:892–900. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller C, Kong J, Tran TT, Arias CA, Saxer G, Shamoo Y. 2013. Adaptation of Enterococcus faecalis to daptomycin reveals an ordered progression to resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5373–5383. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01473-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran TT, Panesso D, Gao H, Roh JH, Munita JM, Reyes J, Diaz L, Lobos EA, Shamoo Y, Mishra NN, Bayer AS, Murray BE, Weinstock GM, Arias CA. 2013. Whole-genome analysis of a daptomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium strain and its daptomycin-resistant variant arising during therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:261–268. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01454-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peleg AY, Miyakis S, Ward DV, Earl AM, Rubio A, Cameron DR, Pillai S, Moellering RC Jr, Eliopoulos GM. 2012. Whole genome characterization of the mechanisms of daptomycin resistance in clinical and laboratory derived isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 7:e28316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Humphries RM, Kelesidis T, Tewhey R, Rose WE, Schork N, Nizet V, Sakoulas G. 2012. Genotypic and phenotypic evaluation of the evolution of high-level daptomycin nonsusceptibility in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:6051–6053. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01318-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelesidis T, Tewhey R, Humphries RM. 2013. Evolution of high-level daptomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium during daptomycin therapy is associated with limited mutations in the bacterial genome. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1926–1928. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kitagawa H, Ozawa T, Takahata S, Iida M, Saito J, Yamada M. 2007. Phenylimidazole derivatives of 4-pyridone as dual inhibitors of bacterial enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductases FabI and FabK. J Med Chem 50:4710–4720. doi: 10.1021/jm0705354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang YM, Marrakchi H, White SW, Rock CO. 2003. The application of computational methods to explore the diversity and structure of bacterial fatty acid synthase. J Lipid Res 44:1–10. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R200016-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marrakchi H, Dewolf WE Jr, Quinn C, West J, Polizzi BJ, So CY, Holmes DJ, Reed SL, Heath RJ, Payne DJ, Rock CO, Wallis NG. 2003. Characterization of Streptococcus pneumoniae enoyl-(acyl-carrier protein) reductase (FabK). Biochem J 370:1055–1062. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heath RJ, Rock CO. 2000. A triclosan-resistant bacterial enzyme. Nature 406:145–146. doi: 10.1038/35018162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emerson JE, Stabler RA, Wren BW, Fairweather NF. 2008. Microarray analysis of the transcriptional responses of Clostridium difficile to environmental and antibiotic stress. J Med Microbiol 57:757–764. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langklotz S, Baumann U, Narberhaus F. 2012. Structure and function of the bacterial AAA protease FtsH. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bove P, Capozzi V, Garofalo C, Rieu A, Spano G, Fiocco D. 2012. Inactivation of the ftsH gene of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1: effects on growth, stress tolerance, cell surface properties and biofilm formation. Microbiol Res 167:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deuerling E, Mogk A, Richter C, Purucker M, Schumann W. 1997. The ftsH gene of Bacillus subtilis is involved in major cellular processes such as sporulation, stress adaptation and secretion. Mol Microbiol 23:921–933. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2721636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zellmeier S, Zuber U, Schumann W, Wiegert T. 2003. The absence of FtsH metalloprotease activity causes overexpression of the sigmaW-controlled pbpE gene, resulting in filamentous growth of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 185:973–982. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.973-982.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wehrl W, Niederweis M, Schumann W. 2000. The FtsH protein accumulates at the septum of Bacillus subtilis during cell division and sporulation. J Bacteriol 182:3870–3873. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.13.3870-3873.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fibriansah G, Kovacs AT, Pool TJ, Boonstra M, Kuipers OP, Thunnissen AM. 2012. Crystal structures of two transcriptional regulators from Bacillus cereus define the conserved structural features of a PadR subfamily. PLoS One 7:e48015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Madoori PK, Agustiandari H, Driessen AJ, Thunnissen AM. 2009. Structure of the transcriptional regulator LmrR and its mechanism of multidrug recognition. EMBO J 28:156–166. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agustiandari H, Lubelski J, van den Berg van Saparoea HB, Kuipers OP, Driessen AJ. 2008. LmrR is a transcriptional repressor of expression of the multidrug ABC transporter LmrCD in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol 190:759–763. doi: 10.1128/JB.01151-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agustiandari H, Peeters E, de Wit JG, Charlier D, Driessen AJ. 2011. LmrR-mediated gene regulation of multidrug resistance in Lactococcus lactis. Microbiology 157:1519–1530. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.048025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lubelski J, de Jong A, van Merkerk R, Agustiandari H, Kuipers OP, Kok J, Driessen AJ. 2006. LmrCD is a major multidrug resistance transporter in Lactococcus lactis. Mol Microbiol 61:771–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guan Z, Katzianer D, Zhu J, Goldfine H. 2014. Clostridium difficile contains plasmalogen species of phospholipids and glycolipids. Biochim Biophys Acta 1842:1353–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Friedman L, Alder JD, Silverman JA. 2006. Genetic changes that correlate with reduced susceptibility to daptomycin in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2137–2145. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00039-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peschel A, Jack RW, Otto M, Collins LV, Staubitz P, Nicholson G, Kalbacher H, Nieuwenhuizen WF, Jung G, Tarkowski A, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA. 2001. Staphylococcus aureus resistance to human defensins and evasion of neutrophil killing via the novel virulence factor MprF is based on modification of membrane lipids with l-lysine. J Exp Med 193:1067–1076. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.9.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mishra NN, Rubio A, Nast CC, Bayer AS. 2012. Differential adaptations of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to serial in vitro passage in daptomycin: evolution of daptomycin resistance and role of membrane carotenoid content and fluidity. Int J Microbiol 2012:683450. doi: 10.1155/2012/683450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang SJ, Mishra NN, Rubio A, Bayer AS. 2013. Causal role of single nucleotide polymorphisms within the mprF gene of Staphylococcus aureus in daptomycin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5658–5664. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01184-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rubio A, Conrad M, Haselbeck RJ, Brown-Driver G CKV, Finn J, Silverman JA. 2011. Regulation of mprF by antisense RNA restores daptomycin susceptibility to daptomycin-resistant isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:364–367. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00429-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bao Y, Sakinc T, Laverde D, Wobser D, Benachour A, Theilacker C, Hartke A, Huebner J. 2012. Role of mprF1 and mprF2 in the pathogenicity of Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS One 7:e38458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roy H, Ibba M. 2009. Broad range amino acid specificity of RNA-dependent lipid remodeling by multiple peptide resistance factors. J Biol Chem 284:29677–29683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ernst CM, Staubitz P, Mishra NN, Yang SJ, Hornig G, Kalbacher H, Bayer AS, Kraus D, Peschel A. 2009. The bacterial defensin resistance protein MprF consists of separable domains for lipid lysinylation and antimicrobial peptide repulsion. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000660. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abranches J, Tijerina P, Aviles-Reyes A, Gaca AO, Kajfasz JK, Lemos JA. 2014. The cell wall-targeting antibiotic stimulon of Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS One 8:e64875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Michaux C, Saavedra LF, Reffuveille F, Bernay B, Goux D, Hartke A, Verneuil N, Giard JC. 2013. Cold-shock RNA-binding protein CspR is also exposed to the surface of Enterococcus faecalis. Microbiology 159:2153–2161. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.071076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pogliano J, Pogliano N, Silverman JA. 2012. Daptomycin-mediated reorganization of membrane architecture causes mislocalization of essential cell division proteins. J Bacteriol 194:4494–4504. doi: 10.1128/JB.00011-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tran TT, Panesso D, Mishra NN, Mileykovskaya E, Guan Z, Munita JM, Reyes J, Diaz L, Weinstock GM, Murray BE, Shamoo Y, Dowhan W, Bayer AS, Arias CA. 2013. Daptomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis diverts the antibiotic molecule from the division septum and remodels cell membrane phospholipids. mBio 4(4):pii:e00281-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00281-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mascher T, Margulis NG, Wang T, Ye RW, Helmann JD. 2003. Cell wall stress responses in Bacillus subtilis: the regulatory network of the bacitracin stimulon. Mol Microbiol 50:1591–1604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolf D, Kalamorz F, Wecke T, Juszczak A, Mader U, Homuth G, Jordan S, Kirstein J, Hoppert M, Voigt B, Hecker M, Mascher T. 2010. In-depth profiling of the LiaR response of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 192:4680–4693. doi: 10.1128/JB.00543-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jordan S, Junker A, Helmann JD, Mascher T. 2006. Regulation of LiaRS-dependent gene expression in Bacillus subtilis: identification of inhibitor proteins, regulator binding sites, and target genes of a conserved cell envelope stress-sensing two-component system. J Bacteriol 188:5153–5166. doi: 10.1128/JB.00310-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Diaz L, Tran TT, Munita JM, Miller WR, Rincon S, Carvajal LP, Wollam A, Reyes J, Panesso D, Rojas NL, Shamoo Y, Murray BE, Weinstock GM, Arias CA. 2014. Whole-genome analyses of Enterococcus faecium isolates with diverse daptomycin MICs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4527–4534. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02686-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Munita JM, Panesso D, Diaz L, Tran TT, Reyes J, Wanger A, Murray BE, Arias CA. 2012. Correlation between mutations in liaFSR of Enterococcus faecium and MIC of daptomycin: revisiting daptomycin breakpoints. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4354–4359. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00509-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hachmann AB, Angert ER, Helmann JD. 2009. Genetic analysis of factors affecting susceptibility of Bacillus subtilis to daptomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:1598–1609. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01329-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goldfine H. 2010. The appearance, disappearance and reappearance of plasmalogens in evolution. Prog Lipid Res 49:493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Drucker DB, Wardle HM, Boote V. 1996. Phospholipid profiles of Clostridium difficile. J Bacteriol 178:5844–5846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Portela CA, Smart KF, Tumanov S, Cook GM, Villas-Boas SG. 2014. Global metabolic response of Enterococcus faecalis to oxygen. J Bacteriol 196:2012–2022. doi: 10.1128/JB.01354-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.