Abstract

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disease of gastrointestinal tract characterized by segmental and transmural involvement of gastrointestinal tract. Ileocolonic and colonic/anorectal is a most common and account for 40% of cases and involvement of small intestine is about 30%. Isolated involvement of stomach is an extremely unusual presentation of the disease accounting for less than 0.07% of all gastrointestinal CD. To date there are only a few documented case reports of adults with isolated gastric CD and no reports in the pediatric population. The diagnosis is difficult to establish in such cases with atypical presentation. In the absence of any other source of disease and in the presence of nonspecific upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and histological findings, serological testing can play a vital role in the diagnosis of atypical CD. Recent studies have suggested that perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and anti-Saccharomycescervisia antibody may be used as additional diagnostic tools. The effectiveness of infliximab in isolated gastric CD is limited to only a few case reports of adult patients and the long-term outcome is unknown.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal tract, Crohn’s disease, Isolated gastric involvement, Perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, Anti-Saccharomycescervisia antibody

Core tip: The stomach is rarely the sole or predominant site of Crohn’s disease (CD) accounting for less than 0.07% of all gastrointestinal CD. Serological testing and meticulous histopathological examination by excluding other causes of granulomatous gastritis can play a vital role to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) can affect any region from mouth to the anus. Isolated Gastroduodenal involvement is an extremely unusual event. The CD is diagnosed usually on the basis of clinical, laboratory, upper gastrointestinal (GI) scopy and histopathology. The anti-Saccharomycescervisia antibody (ASCA) is relatively good specific marker with minimal sensitivity. However, it is difficult to diagnose it in patients with isolated involvement of stomach and duodenum. In such circumstances other granulomatous conditions must be excluded with careful evaluation of the patient to hit the accurate pathological cause[1,2].

The famous criteria to diagnose this rare condition are: (1) evidence of noncaseating granulomas on histopathology; and (2) confirmation of changes of Crohn’s disease on endoscopy or radiography[3-10].

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Incidence

It occurs in 0.5% to 4% patients of CD[3-6]. Isolated stomach and duodenum involvement accounts for less than 0.07% of all cases of CD[1].

Pattern of involvement

Most patients show involvement of terminal ileum and distal segment of large intestine[4,5,7]. Contiguous involvement of stomach and duodenal involvement is most common (60%)[6,10-12].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

For pathogenesis of isolated gastric CD multiple hypothesis were postulated: (1) the hygiene hypothesis relatively less trained and weak immunological system leading to ineffective immune response to newer antigens; (2) the environmental factors i.e., geography, smoking, drugs, diet are also main contributing factors[13,14]; (3) immune mechanism - It is being postulated that the immune reactivity in this disease is due to “loss of immune tolerance” to self antigens of intestinal flora, resulting into an inappropriate granulomatous immune response of Chron’s disease[15,16]; and (4) role of chemical mediators - interferon-γ, interleukin (IL)-12, IL-18 and increased expression of T-bet[17-19]. T-cells are not undergoing apoptosis [20-25].

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS

Age

The disease mainly seen in the age group 30-40 years[6].

Sex predilection

Symptoms and signs

Majority of the patients are usually symptomless[9]. Most of the patients are presenting with pain in epigastric region, relieved by antacids and food intake[4,9,11]. In cases with stricture formation persistent pain, nausea and vomiting are common[4]. Many times,it may simulates acid peptic disease clinically[4]. Acute blood loss may rarely occur[4,9,11,26,27].

Uncommon presentations

Uncommon presentations of CD may manifest as a single symptom or sign, such as impairment of linear growth, delayed puberty, perianal disease, mouth ulcers, clubbing, chronic iron deficiency anemia or extra-intestinal manifestations preceding the gastrointestinal symptoms, mainly arthritis or arthralgia and rarely osteoporosis[2]. In such cases, the diagnosis is challenging and can remain elusive for some time.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Radiological signs

Aphthous ulcer is the early feature on radiography[28]. The characteristic features are presence of nodularity in the mucosa giving classic appearance of “cobblestone”[4]. Radiography examination using double-contrast medium is useful in cases with stenoses or strictures which are mainly seen in advanced disease[6,12,27,29,30]. A barium enema should be done in suspected cases of gastro colic fistula[4].

Endoscopy

Endoscopy with biopsy is an effective diagnostic modality[6,9,27,30]. Endoscopic findings include patchy erythema, gastric outlet narrowing (Figure 1) mucosa is friable, thickening of mucosa and ulcerations linear as well as aphthous[4,7,9,12]. The ulcers of CD are typically linear or serpiginous in contrast to the peptic ulcers[27]. In cases with diffuse stomach involvement a linitis plastica appearance,is seen[31,32]. Sophisticated endoscopic features such as, bamboo-joint-like appearance and notched sign can be seen[33].

Figure 1.

Endoscopic findings include patchy erythematic, gastric outlet narrowing.

Biopsy findings

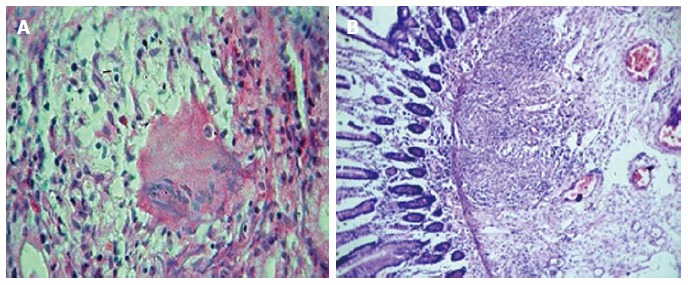

The biopsy findings are often nonspecific. Exclusion of other causes of granulomatous lesions is important. Granulomas without caseation are noted in 5% to 83% of cases (Figure 2)[9,12]. The differential diagnosis of granulomatous gastritis are H. pylori infection, gastric sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, etc[7,9,32]. So presence of granuloma is not a definitive criterion to arrive at the diagnosis. H. pylori negative chronic gastritis is common feature.

Figure 2.

Biopsy showing non-caseating granulomas and oedema in the submucosa (HE × 10). A: Non-caseating granulomas; B: Oedema alongwith granulation tissue.

Additional histological features are mucosal edema, crypt abscesses, lymphoid aggregates and fibrosis[32-34].

Serological markers

Currently, it has been stated that perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) and ASCA can be used as supportive diagnostic tools. Indeed, ASCA is detected in 55%-60% of children and adults with CD and only 5%-10% of controls with other gastrointestinal disorders. This finding pANCA highlights the relatively good specificity but poor sensitivity of ASCA as a marker for CD. pANCA on the other hand is more specific to ulcerative colitis.

Genetic studies

In addition, some NOD2/ CARD15 gene polymorphisms were found to be associated with CD with gastroduodenal involvement. It is possible that these genes might also help to support the diagnosis in the atypical presentation of CD in the future[2].

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis includes corrosive gastritis due to ingestion of lye, gastric scirrhous carcinoma, Ménétrier’s disease. Pseudolymphoma, amyloidosis can also mimic CD[29]. Although Ménétrier’s disease can involve the entire stomach and produce ulcérations, it does not cause transmural disease[29]. Malignant and infiltrative processes are to be ruled out by the histological findings.

TREATMENT

Medical treatment

Proton pump inhibitors in combination with steroids are the first line of treatment in active CD. Some of the studies proved steroid-induced remission in active disease[10,11,35-39]. But, 6-Mercaptopurine and azathioprine are proved to be helpful to maintain steroid induced remission.

Balloon dialation

Strictures are treated successfully with balloon dilation[4,5,40-43].

Surgical intervention

Some of the patients requires surgical intervention, where patients are not responding to medical treatment[44]. Other situations are massive and persistent upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, gastric outlet obstruction, and fistula or abscess formation[4,5,7,10,12,45]. The important indication is duodenal obstruction[6]. The surgical modalities of treatment include bypass surgery with gastrojejunostomy[6,7,9]. Gastrojejunostomy with highly selective vagotomy is an ideal line of management[44]. Delayed gastric emptying is a postoperative complication seen in 24% of cases, but this may be seen in stricturoplasty also[6,46,47]. Additional post operative complications are anastomotic leak, enterocutaneous fistula, intraabdominal abscess, and stomal ulceration[48].

CONCLUSION

To conclude, CD with isolated gastric involvement is an extremely unusual event in clinical practice. Endoscopic biopsy along with battery of laboratory tests is an effective tool to hit the correct diagnosis by exclusion of various causes of granulomatous gastritis. This prevents untoward mortality and/morbidity related to disease and treatment.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest: None is to be declared.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: November 22, 2014

First decision: December 12, 2014

Article in press: April 29, 2015

P- Reviewer: Chen JQ, Caviglia R, Hokama A S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Ingle SB, Pujari GP, Patle YG, Nagoba BS. An unusual case of Crohn’s disease with isolated gastric involvement. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:69–70. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingle SB, Hinge CR, Dakhure S, Bhosale SS. Isolated gastric Crohn’s disease. World J Clin Cases. 2013;1:71–73. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i2.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isaacs KL. Upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:451–462, vii. doi: 10.1016/s1052-5157(02)00006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burakoff R. Gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease. In: Bayless TM, Hanauer SB, editors. Advanced therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker; 2001. pp. 421–423. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee S, Peppercorn MA. Inflammatory bowel disease. Medical therapy of specific clinical presentations. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:185–202, x. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(01)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds HL, Stellato TA. Crohn’s disease of the foregut. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:117–135, viii. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Hogezand RA, Witte AM, Veenendaal RA, Wagtmans MJ, Lamers CB. Proximal Crohn’s disease: review of the clinicopathologic features and therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:328–337. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sands BE. Crohn’s disease. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, editors. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. pp. 2005–2038. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loftus EV. Upper gastrointestinal tract Crohn’s disease. Clin Perspect Gastroenterol. 2002;5:188–191. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nugent FW, Richmond M, Park SK. Crohn’s disease of the duodenum. Gut. 1977;18:115–120. doi: 10.1136/gut.18.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nugent FW, Roy MA. Duodenal Crohn’s disease: an analysis of 89 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagtmans MJ, Verspaget HW, Lamers CB, van Hogezand RA. Clinical aspects of Crohn’s disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a comparison with distal Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1467–1471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bach JF. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:911–920. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danese S, Sans M, Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: the role of environmental factors. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lodes MJ, Cong Y, Elson CO, Mohamath R, Landers CJ, Targan SR, Fort M, Hershberg RM. Bacterial flagellin is a dominant antigen in Crohn disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1296–1306. doi: 10.1172/JCI20295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Targan SR, Landers CJ, Yang H, Lodes MJ, Cong Y, Papadakis KA, Vasiliauskas E, Elson CO, Hershberg RM. Antibodies to CBir1 flagellin define a unique response that is associated independently with complicated Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:2020–2028. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neurath MF, Weigmann B, Finotto S, Glickman J, Nieuwenhuis E, Iijima H, Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Mudter J, Galle PR, et al. The transcription factor T-bet regulates mucosal T cell activation in experimental colitis and Crohn’s disease. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1129–1143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monteleone G, Biancone L, Marasco R, Morrone G, Marasco O, Luzza F, Pallone F. Interleukin 12 is expressed and actively released by Crohn’s disease intestinal lamina propria mononuclear cells. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pizarro TT, Michie MH, Bentz M, Woraratanadharm J, Smith MF, Foley E, Moskaluk CA, Bickston SJ, Cominelli F. IL-18, a novel immunoregulatory cytokine, is up-regulated in Crohn’s disease: expression and localization in intestinal mucosal cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:6829–6835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ina K, Itoh J, Fukushima K, Kusugami K, Yamaguchi T, Kyokane K, Imada A, Binion DG, Musso A, West GA, et al. Resistance of Crohn’s disease T cells to multiple apoptotic signals is associated with a Bcl-2/Bax mucosal imbalance. J Immunol. 1999;163:1081–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sturm A, Leite AZ, Danese S, Krivacic KA, West GA, Mohr S, Jacobberger JW, Fiocchi C. Divergent cell cycle kinetics underlie the distinct functional capacity of mucosal T cells in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2004;53:1624–1631. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.033613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:345–352. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maul J, Loddenkemper C, Mundt P, Berg E, Giese T, Stallmach A, Zeitz M, Duchmann R. Peripheral and intestinal regulatory CD4+ CD25(high) T cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1868–1878. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hart AL, Al-Hassi HO, Rigby RJ, Bell SJ, Emmanuel AV, Knight SC, Kamm MA, Stagg AJ. Characteristics of intestinal dendritic cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:50–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wehkamp J, Harder J, Weichenthal M, Schwab M, Schäffeler E, Schlee M, Herrlinger KR, Stallmach A, Noack F, Fritz P, et al. NOD2 (CARD15) mutations in Crohn’s disease are associated with diminished mucosal alpha-defensin expression. Gut. 2004;53:1658–1664. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.032805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogler G. Update in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2004;20:311–317. doi: 10.1097/00001574-200407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rutgeerts P, Onette E, Vantrappen G, Geboes K, Broeckaert L, Talloen L. Crohn’s disease of the stomach and duodenum: A clinical study with emphasis on the value of endoscopy and endoscopic biopsies. Endoscopy. 1980;12:288–294. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine MS. Crohn’s disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Radiol Clin North Am. 1987;25:79–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cary ER, Tremaine WJ, Banks PM, Nagorney DM. Isolated Crohn’s disease of the stomach. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:776–779. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61750-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danzi JT, Farmer RG, Sullivan BH, Rankin GB. Endoscopic features of gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alcántara M, Rodriguez R, Potenciano JL, Carrobles JL, Muñoz C, Gomez R. Endoscopic and bioptic findings in the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients with Crohn’s disease. Endoscopy. 1993;25:282–286. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Noffsinger AE, Stemmermann GN, Lantz PE, Listrom MB, Rilke FO. The non neoplastic stomach. In: Gastrointestinal Pathology., editor. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. pp. 153–236. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hashiguchi K, Takeshima F, Akazawa Y, Matsushima K, Minami H, Yamaguchi N, Shiozawa K, Ohnita K, Ichikawa T, Isomoto H, et al. Bamboo joint-like appearance of the stomach: a stable endoscopic landmark for Crohn’s disease regardless of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha treatment. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1918–1924. doi: 10.12659/MSM.891060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halme L, Kärkkäinen P, Rautelin H, Kosunen TU, Sipponen P. High frequency of helicobacter negative gastritis in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1996;38:379–383. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oberhuber G, Püspök A, Oesterreicher C, Novacek G, Zauner C, Burghuber M, Vogelsang H, Pötzi R, Stolte M, Wrba F. Focally enhanced gastritis: a frequent type of gastritis in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:698–706. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parente F, Cucino C, Bollani S, Imbesi V, Maconi G, Bonetto S, Vago L, Bianchi Porro G. Focal gastric inflammatory infiltrates in inflammatory bowel diseases: prevalence, immunohistochemical characteristics, and diagnostic role. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:705–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miehsler W, Püspök A, Oberhuber T, Vogelsang H. Impact of different therapeutic regimens on the outcome of patients with Crohn’s disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:99–105. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valori RM, Cockel R. Omeprazole for duodenal ulceration in Crohn’s disease. BMJ. 1990;300:438–439. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6722.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griffiths AM, Alemayehu E, Sherman P. Clinical features of gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease in adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;8:166–171. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198902000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korelitz BI, Adler DJ, Mendelsohn RA, Sacknoff AL. Long-term experience with 6-mercaptopurine in the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1198–1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsui T, Hatakeyama S, Ikeda K, Yao T, Takenaka K, Sakurai T. Long-term outcome of endoscopic balloon dilation in obstructive gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease. Endoscopy. 1997;29:640–645. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dancygier H, Frick B. Crohn’s disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 1992;24:555–558. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murthy UK. Repeated hydrostatic balloon dilation in obstructive gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:484–485. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70789-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcello PW, Schoetz DJ. Gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease: surgical management. In: Bayless TM, Hanauer SB, editors. Advanced therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker; 2001. pp. 461–463. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray JJ, Schoetz DJ, Nugent FW, Coller JA, Veidenheimer MC. Surgical management of Crohn’s disease involving the duodenum. Am J Surg. 1984;147:58–65. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Worsey MJ, Hull T, Ryland L, Fazio V. Strictureplasty is an effective option in the operative management of duodenal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:596–600. doi: 10.1007/BF02234132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto T, Bain IM, Connolly AB, Allan RN, Keighley MR. Outcome of strictureplasty for duodenal Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1999;86:259–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto T, Allan RN, Keighley MR. An audit of gastroduodenal Crohn disease: clinicopathologic features and management. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:1019–1024. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]