Abstract

Background

There is a growing recognition that individuals at clinical high risk need intervention for functional impairments, along with emerging psychosis, as the majority of clinical high risk (CHR) individuals show persistent deficits in social and role functioning regardless of transition to psychosis. Recent studies have demonstrated reduced reading ability as a potential cause of functional disability in schizophrenia, related to underlying deficits in generation of mismatch negativity (MMN). The present study extends these findings to subjects at CHR.

Methods

The sample consisted of 34 CHR individuals and 33 healthy comparisons subjects (CNTLs) from the Recognition and Prevention (RAP) Program at the Zucker Hillside Hospital in New York. At baseline, reading measures were collected, along with MMN to pitch, duration, and intensity deviants, and measures of neurocognition, and social and role (academic/work) functioning.

Results

CHR subjects showed impairments in reading ability, neurocognition, and MMN generation, relative to CNTLs. Lower-amplitude MMN responses were correlated with worse reading ability, slower processing speed, and poorer social and role functioning. However, when entered into a simultaneous regression, only reduced responses to deviance in sound duration and volume predicted poor social and role functioning, respectively.

Conclusions

Deficits in reading ability exist even prior to illness onset in schizophrenia and may represent a decline in performance from prior abilities. As in schizophrenia, deficits are related to impaired MMN generation, suggesting specific contributions of sensory-level impairment to neurocognitive processes related to social and role function.

Keywords: Early Intervention, social functioning, clinical high risk, mismatch negativity, reading

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder associated with significant disruptions in functioning. Impairments in social and occupational functioning reduce independence, limit educational attainment, and decrease quality of life(Green, 2006; Harvey et al., 2012), placing a substantial burden on patients, family members, friends and wider society(Awad and Voruganti, 2008; Knapp et al., 2004). Given that functional impairments in schizophrenia are rooted early in development, pre-illness social problems and school difficulties can provide a pivotal pathway to understanding the determinants of long-term disability. Recent research in schizophrenia has, therefore, focused on the detection of individuals at clinical high-risk (CHR) for developing the illness, with the ultimate goal of permitting focused intervention to prevent both conversion to psychosis and functional disability.

In established schizophrenia, several factors including neurocognition, negative symptoms, and social cognition are strongly connected to everyday functioning. In addition, over recent years there has been increasing appreciation of the importance of impaired sensory processing. For example, amplitudes of the auditory mismatch negativity (MMN) are strongly associated with work, community, and independent functioning both in patients with schizophrenia (Kawakubo and Kasai, 2006; Kim et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2014; Light and Braff, 2005a, b; Wynn et al., 2010) and first-episode psychosis (Friedman et al., 2012). The MMN is an auditory event-related potential (ERP) that reflects deviance-detection within the primary auditory cortex(Light and Näätänen, 2013; Wible et al., 2001). MMN amplitude reductions in schizophrenia were first demonstrated over 20 years ago (Javitt et al., 1993; Shelley et al., 1991) and were tied to impaired neurotransmission at N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors(Javitt, 2009; 1996; Umbricht et al., 2000). Since then, impairments have been replicated multiple times, with patients showing deficits of approximately 1 standard deviation (SD) across a range of deviant types(Todd et al., 2008; Umbricht and Krljes, 2005). Deficits in reading ability have also been increasingly documented over recent years (Martinez et al., 2012; Revheim et al., 2006; Whitford et al., 2013). In a recent study in patients with schizophrenia, reading ability deficits were related with impaired MMN generation(Revheim et al., 2014), suggesting that deficits in early auditory processing may cascade up to produce impairments in higher-order abilities that are in turn linked to functioning in the environment.

To date, studies of sensory function in individuals at CHR have focused primarily on MMN from the vantage of transition to schizophrenia. Such studies have demonstrated consistent reductions of MMN in CHR individuals, albeit of smaller magnitude (typically 0.6-0.8 SDs vs. controls) than those observed in schizophrenia(Atkinson et al., 2012; Bodatsch et al., 2011; Higuchi et al., 2013; Jahshan et al., 2012; Perez et al., 2013; Shaikh et al., 2012; Solis-Vivanco et al., 2014). In addition, reductions in MMN amplitudes significantly predict conversion to psychosis among CHR individuals(Atkinson et al., 2012; Bodatsch et al., 2011; Higuchi et al., 2013; Perez et al., 2013; Shaikh et al., 2012). However, a relationship between MMN and functioning in this vulnerable population has remained relatively unexplored.

Given that the antecedents of functional disability associated with schizophrenia are present years prior to the onset of the illness, adolescents and young adults at CHR may provide a timely window for investigating the contributions of early cortical processing to social and role functioning. Although prior MMN studies in CHR individuals have focused primarily on predictions of conversion to psychosis, the present study focuses as well on early sensory contributions to social and role functioning within the CHR population. In recent studies (Carrión et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2014; Olvet et al., 2013), we have demonstrated significant social and role (i.e., work/academic) functioning impairments in individuals meeting CHR criteria. Furthermore, patients showed neurocognitive impairments that were highly predictive of impaired social and role functioning. Moreover, initial CHR classification is associated with persistent and long-standing functional difficulties independent of emerging psychotic symptoms (Carrión et al., 2013), suggesting that functional impairments may be viewed as an important component of the CHR state irrespective of ultimate conversion status. The present study was designed to replicate and extend these investigations by utilizing a neurophysiological biomarker of early auditory cortical function, along with standard neuropsychological measures, to further examine pathways to impaired functioning in CHR individuals. In addition, given recent reports of impaired reading ability in schizophrenia, the present study includes measures of reading ability. Passage reading is a skill that comes into play in a wide set of circumstances and is critical for academic success(Herbers et al., 2012). Passage reading, in contrast to reading single words, requires the manipulation of visual symbols into smaller speech sounds and depends on the detection of rapidly changing auditory stimuli. Although reading deficits have recently been reported in a limited sample of CHR subjects(Revheim et al., 2014), their relationship with underlying sensory impairments and functioning remains to be determined.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1 Participants

Thirty-four subjects (age range, 12-22) met Clinical High-Risk, Positive (CHR+) criteria based on the presence of one or more moderate, moderately severe, or severe (scores of 3, 4, or 5) Scale of Prodromal Symptoms rated (scale of 0-6) attenuated positive symptoms(SOPS(Miller et al., 2003; 2002; 1999). Referrals to the RAP Program were made by affiliated outpatient and inpatient psychiatry departments, local mental health providers, school psychologists or counselors, or were self-referred.

Thirty-three healthy comparison subjects (CNTLs) were also enrolled and recruited through announcements in local newspapers and within the medical center during the same time period as the patients. Inclusion criteria were a baseline age between 12-25 years. Exclusion criteria for all participants included: (1) Schizophrenia-spectrum diagnosis(Orvaschel and Puig-Antich, 1994); (2) Non-English speaking; (3) History of neurological disorder; (4) IQ<70; (5) Healthy controls with a first-degree relative with a diagnosed Axis I psychotic disorder were also excluded.

This cross-sectional report includes a subsample of CHR+ participants enrolled in the larger second phase of the Recognition and Prevention (RAP) Program (2006-2012, total N=139), an NIMH funded (2000-2012) longitudinal investigation. This subsample was recruited from all CHR+ subjects that consecutively entered the RAP Program from 2010-2012 who were willing to participate in the ERP protocol. Written informed consent (≥18 years-old) or assent (<18) with consent from parents was obtained. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the North Shore-LIJ Health System.

2.2 Measures

Prodromal symptoms were assessed by the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS) and the companion SOPS (Miller et al., 2003; 2002; 1999). Social and role functioning was assessed using the GF:Social and GF:Role scales(Cornblatt et al., 2007). The GF:Social scale assesses peer relationships, peer conflict, age-appropriate intimate relationships, and involvement with family members. The GF:Role scale rates performance and amount of support needed in one’s specific role (i.e., school, work).

Reading ability was assessed with the Gray Oral Reading Test (GORT-4, (Wiederholt and Bryant, 2001), Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP, (Wagner, 1999) and Wide Range Achievement Test-3 (WRAT-3, (Wilkinson, 1993). The GORT-4 Overall Reading Quotient (ORQ, M=100, S.D.=15) measured overall reading ability and subscale scores (M=10, S.D.=3) measure Rate (time taken to read a story), Accuracy (correct pronunciation), Fluency (Rate+Accuracy), and Comprehension (accuracy on multiple-choice questions). The CTOPP Phonological Awareness Composite Score (PACS) and Alternate PACS (APACS) measured phonological processing abilities(Revheim et al., 2006). The WRAT-3 Reading subtest measured single-word reading skills. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB, (Green and Nuechterlein, 2004; Green et al., 2004) assessed neurocognitive performance in six domains: Processing Speed, Attention/Vigilance, Working Memory, Verbal Learning, Visual Learning, and Reasoning/Problem Solving. Estimated full-scale IQ scores were derived from the Vocabulary and Block Design subscales of the WISC-III(Wechsler, 1991) for subjects<16 years old and WAIS-R(Wechsler, 1981) for subjects≥16 years old.

2.3 Auditory Stimuli Presentation

Stimulus parameters were based on a previous report (Friedman et al., 2012). Sound stimuli were presented binaurally through foam insert headphones (ER-1, Etymotic, Illinois, USA) in a fixed order at stimulus onset asynchronies of 500-505ms using stimulus delivery software (Presentation, Neurobehavioral Systems, California, USA). Sound stimuli were a standard harmonic tone (p=.67, 85dB, 100ms duration, 5ms rise and fall time, overlapping 500, 1000, and 1500Hz sinusoids). Deviant tones (p=.11 for each) included a frequency (three superimposed sinusoids at 450, 900 and 1650Hz), intensity (75dB), and duration deviant (150ms). Stimuli occurred in a fixed order (2 standards, 1 deviant). Deviant stimuli were also presented in a fixed order (duration, intensity, and frequency). Auditory stimuli were presented simultaneously with a visual distractor task in which subjects were asked to attend to a sequence of visual stimuli presented at central fixation and respond to a designated target stimulus that occurred on 11% of trials. Responses to visual stimuli were not analyzed as part of the present report. Auditory and visual sequences were uncorrelated and timed to prevent stimulus overlap.

2.4 EEG Recording and Analysis

EEG activity was recorded with a BioSemi Active-Two system (Biosemi Instrumentations, Amsterdam, Netherlands) from 32 pin-type active Ag/AgCl electrodes mounted in an elastic cap according to the international 10–20 system. Flat-type active electrodes were attached to the nose, left and right mastoids, and above and below the left eye (VEOG) and at the outer canthi of both eyes (HEOG). Additional pin-type active (CMS-common mode sense) and passive (DRL-driven right leg) electrodes were used to comprise a feedback loop for amplifier reference. EEG and EOG were recorded continuously with a sampling frequency of 1024Hz (band-pass .16–100Hz).

Offline data processing was performed blind to group membership with Brain Vision Analyzer 2 (BrainProducts, Gilching, Germany). Epochs were 500ms in duration (100ms pre- to 400ms post-stimulus onset). Gratton’s eye-movement correction algorithm reduced ocular artifacts.(Gratton et al., 1983) Trials with excessive eye or body movement (±75 μV) were excluded. On average, 3.1% of all trials were rejected for controls and 3.4% for CHR+ subjects. Grand-average ERPs to each trial type were created off-line by averaging the subject-averaged ERPs. The EEG signals were referenced to linked mastoids (average signal of electrodes placed over both mastoid bones), filtered (1-20Hz bandpass, zerophase shift, 24 dB/octave slope and 60Hz notch filter) and baseline corrected (100ms pre-stimulus interval). The MMN was obtained by subtracting the standard from the deviant ERP. Latency windows were indentified based on visual inspection of the ERP waveforms and in accordance with previous research(Friedman et al., 2012). Peak amplitudes (±12.5ms surrounding peak) of MMN components were measured across 10 fronto-central sites (Fz, F3, F4, F7, F8, Cz, C3, C4, CP1, CP2) within the following post-stimulus time windows: 110–170ms for frequency, 140-210ms for intensity, and 160–260ms for duration MMN.

2.5 Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 16 (SPSS Inc., Illinois, USA). Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared with Student’s T-tests for continuous variables or Pearson Chi-Square tests for categorical variables (Two-tailed, P<.05). Reading ability and neurocognitive scores were evaluated with analysis of variance (ANOVA). Repeated measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA) was also used to evaluate differences in the peak amplitudes of the MMN components, with group (CNTL, CHR+) as a between-subjects factor and deviant type (frequency, intensity, duration) as a within-subject factor.

Bivariate and partial correlation coefficients (r) among ERPs, reading ability and functioning were determined by multiple linear regressions. Multivariable linear regression models were constructed with backward (stepwise) inclusion (p<.05) with social and role functioning as dependent variables, and MMN amplitudes and reading measures (GORT ORQ, CTOPP, WRAT-3 reading scores) entered simultaneously as independent variables, adjusted for diagnostic group, neurocognitive performance.

3. Results

As shown in Table 1, the CNTL and CHR+ groups did not differ significantly on age, gender, handedness, race, or ethnicity. There was no difference in IQ, however, CNTLs had higher education levels. In addition, subjects at CHR+ demonstrated lower social and role functioning scores on the GF scales, along with higher positive, negative, disorganized, and general symptom levels when compared to CNTLs.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants at Baseline

| Characteristic | Healthy Comparison Group (n=33) |

Clinical High-Risk, Positive (n=34) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 18.18 (2.97) | 17.07 (2.18) | .09 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 11.84 (2.42) | 10.44 (1.94) | .02 |

| Estimated Current IQ, mean (SD) | 102.94 (14.96) | 97.53 (15.06) | .15 |

| Gender, No. (%) | |||

| Female | 15 (45.5) | 16 (47.1) | 1.00 |

| Handedness, right, No. (%) | 28 (84.8) | 28 (82.4) | 1.00 |

| Race, No. (%) | |||

| White | 16 (48.5) | 13 (38.2) | .33 |

| Ethnic Origin, No. (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 4 (12.1) | 8 (23.5) | .34 |

| SOPS score, mean (SD) | |||

| Positive | .94 (1.45) | 10.74 (3.89) | <.001 |

| Negative | 2.4 (2.73) | 12.76 (6.10) | <.001 |

| Disorganization | .70 (1.24) | 5.26 (3.52) | <.001 |

| General | .85 (1.95) | 10.71 (4.54) | <.001 |

| Global Functioning, mean (SD) | |||

| Social | 8.64 (1.32) | 5.68 (1.23) | <.001 |

| Role | 8.45 (1.87) | 5.85 (2.16) | <.001 |

| Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), mean (SD) | 81.73 (15.10) | 47.53 (11.70) | <.001 |

| Medication at Testing, No. (%) | |||

| No Medication | 34 (100) | 18 (52.9) | <.001 |

| Anti-psychotics | 0 (0.0) | 8 (23.5) | .001 |

| Anti-depressants | 0 (0.0) | 10 (29.4) | .005 |

Abbreviations: CHR, Clinical High-Risk; SOPS, Structured Interview for Prodromal Symptoms.

At the time of testing, a majority of CHR+ subjects (52.9%) were not receiving any medication. The remaining CHR subjects were receiving atypical antipsychotics (23.5%) and antidepressants (29.4%). Medication type or status did not account for any differences on any ERP component (p>.05) reported in this article.

3.1 Reading Ability and Neurocognitive Performance

CHR+ subjects and controls did not differ in estimated premorbid (single-word) reading ability as reflected in WRAT-3 (see Table 2). In contrast, CHR+ patients showed passage reading impairments with lower scores on the GORT-ORQ (p<.05), that persisted even when adjusting for WRAT-3 reading performance (F1,64=3.92, p=.05). When divided in subdomains, reading impairments as measured by the ORQ were primarily driven by reductions in fluency (p<.05), not comprehension (p=.29). CHR+ subjects also showed significant neurocognitive impairments relative to CNTLs in the domains of processing speed, working memory, visual learning, and verbal learning (p<.01), although other neurocognitive domains were not significantly affected. CHR+ subjects and CNTLs showed similar phonological processing as there were no significant differences on the CTOPP PACS (p=.92) or APACS (p=.20).

Table 2.

Reading and Neurocognitive Domain scores for Clinical High Risk and Healthy Comparison subjects

| Healthy Comparison Group (n=33) |

Clinical High-Risk, Positive Group (n = 34) |

Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | F1,65 | P Value | |

| WRAT3 Reading Subtest (SS) | 105.18 (11.29) | 100.15 (14.10) | 2.59 | .112 |

| GORT-4 (SS) | ||||

| Rate | 10.45 (1.89) | 9.03 (2.30) | 7.63 | .007 |

| Accuracy | 9.76 (2.50) | 8.17 (2.76) | 6.13 | .016 |

| Fluency | 10.45 (2.96) | 8.10 (3.55) | 8.58 | .005 |

| Comprehension | 9.05 (1.65) | 8.61 (1.761) | 1.12 | .293 |

| Overall Reading Quotient (ORQ) | 98.71 (11.64) | 90.94 (12.82) | 6.73 | .012 |

| CTOPP-Composite Scores (SS) | ||||

| Phonological Awareness | 91.94 (20.67) | 92.37 (16.41) | .01 | .924 |

| Alternate Phonological Awareness | 89.74 (14.49) | 85.70 (10.98) | 1.66 | .202 |

| MCCB Cognitive Domain Scores (z-scorea) | ||||

| Speed of Processing | .24 (.94) | −.98 (1.24) | 20.59 | .000 |

| Attention/Vigilance | .05 (1.05) | −.32 (1.19) | 1.82 | .182 |

| Working Memory | .09 (.92) | −.68 (1.69) | 5.29 | .025 |

| Verbal Learning | .13 (1.08) | −.84 (1.39) | 10.02 | .002 |

| Visual Learning | −.03 (.95) | −.78 (1.22) | 7.90 | .007 |

| Reasoning and Problem Solving | .00 (1.03) | −.13 (1.25) | .22 | .638 |

Raw test scores on the MCCB were transformed into standard Z-scores using age-stratified means and SDs of a local demographically-matched sample of healthy subjects (n=68).

Abbreviations: GORT-4, Gray Oral Reading Test (GORT-4), CTOPP, Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing; WRAT-3, Wide Range Achievement Test-3; ORQ, Overall Reading Quotient; MCCB, MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery.

3.2 Auditory MMN Analyses

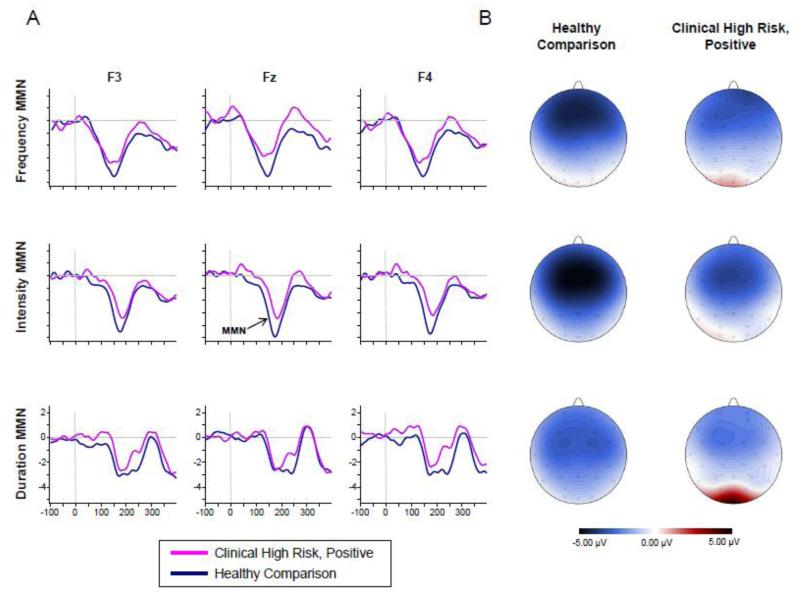

Figure 1 shows grand-averaged waveforms and 2D topographic maps for frequency, intensity, and duration MMN in the CNTL and CHR+ groups. Relative to CNTLs, the CHR+ group showed a reduced MMN across all the deviant types. RM-ANOVA of MMN peak amplitudes indicated a significant main effect of group (F1,65=11.75, p=0.001), but a non-significant main effect of deviant type (F2,64=2.40, p=0.10) or group × deviant type interaction (F2,64=0.38, p=0.68) as the degree of differences was similar across the deviant types. As shown in Table 3, there was a clear reduction in frequency (d=0.56), intensity (d=0.65), duration (d=0.68) MMN amplitudes in CHR+ subjects relative to CNTLs (see Table S1 for peak amplitudes at individual electrode sites). A RM-ANOVA of MMN latency indicated a difference in peak latency between deviant types (F2,64=101.66, p<0.001, ε=.89), with Frequency<Intensity<Duration, but no latency differences between groups (F2,64=1.56, df=1,63, p=.217) or group × deviant type interaction (F2,64=1.76, p=0.18).

Figure 1.

Mismatch negativity for Frequency (Top), Intensity (Middle), and Duration (Bottom) deviants. (A) Grand averaged ERPs elicited by CHR and healthy comparison subjects at three representative electrode sites (Fz, F3, and F4 re-referenced to linked mastoids). CHR and Healthy comparison subjects are shown in pink and blue, respectively. All waveforms are drawn on the same voltage scale (±5μV) as shown on the bottom plots. (B) Topography maps depicting the scalp distribution for the MMN (peak amplitude, ±12.5ms) for each deviant type for healthy comparison (left) and CHR subjects (right). All maps are drawn on the same voltage scale (±5μV) as shown in the legend.

Table 3.

Peak Amplitudes and Latencies of Auditory MMNa

| Healthy Comparison Group (n=33) |

Clinical High Risk, Positive (n=34) |

P Value | Effect Size (d)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude | ||||

| Frequency MMN | −4.33 (2.00) | −3.40 (1.78) | .049 | .49 |

| Intensity MMN | −4.71 (2.58) | −3.30 (1.69) | .01 | .65 |

| Duration MMN | −4.02 (1.53) | −2.91 (1.28) | .002 | .79 |

| Latency | ||||

| Frequency MMN | 145.63 (21.76) | 146.10 (20.89) | .93 | .02 |

| Intensity MMN | 176.44 (14.06) | 182.38 (16.12) | .11 | .39 |

| Duration MMN | 202.88 (22.87) | 200.59 (25.12) | .70 | .10 |

The MMN values are the mean of the response at the 10 fronto-central electrode sites (Fz, F3, F4, F7, F8, Cz, C3, C4, CP1, CP2).

Cohen’s d can be interpreted using the following categories: small = .20, medium = .50, large = .80.

3.3 Relationships between Auditory MMN, Reading Ability, and Functioning

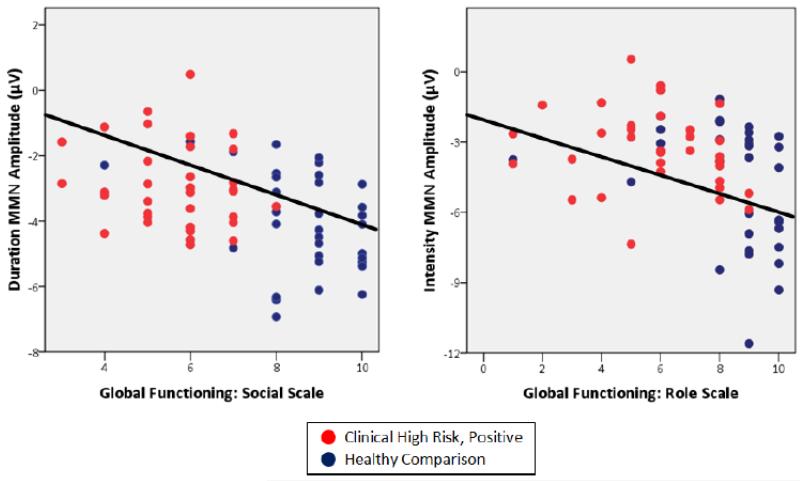

Lower social functioning was significantly correlated with reduced frequency (r=−.22, p=.03), intensity (r=−.30, p=.01), and duration (r=−.44, p<.001) MMN amplitudes in addition to lower processing speed (r=.35, p<.001), verbal learning (r=.21, p=.02), and GORT-ORQ (r=.23, p=.03) scores (see Table 4). However, when entered into a stepwise linear regression, only lower duration MMN amplitudes remained within the model (F2,64=51.11, β=−.181, p=.03, Adjusted R2=.60). Furthermore, this correlation remained significant, even after accounting for diagnostic group and neurocognitive performance (Partial r=−.26, p=.03).

Table 4.

Correlations between Auditory ERP components, neurocognitive performance, reading measures, and functioning across subjects at CHR and healthy controls.

| GF:Social | GF:Role | Frequency MMN | Intensity MMN | Duration MMN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency MMN | −.23* | −.06 | - | - | - |

| Intensity MMN | −.30* | −.37** | .44** | - | - |

| Duration MMN | −.44*** | −.27* | .34** | .41** | - |

| Processing Speed | .35** | .26* | −.25* | −.21* | −.18 |

| Working Memory | .18 | .03 | −.12 | −.10 | .00 |

| Attention/Vigilance | .04 | .01 | −.15 | .07 | −.02 |

| Verbal Learning | .24* | .31** | −.08 | −.09 | −.01 |

| Visual Learning | .21* | .07 | .08 | .14 | .03 |

| Reasoning/Problem Solving | .00 | −.12 | −.08 | .03 | −.01 |

| GORT-4 ORQ | .23* | .25* | .01 | −.21* | −.02 |

| CTOPP PACS | −.13 | −.18 | −.08 | .08 | .20 |

| CTOPP APACS | .11 | .17 | −.25* | −.21* | .06 |

| WRAT-III Reading | .15 | .10 | −.02 | −.22 | −.04 |

Abbreviations: GF:Social, Global Functioning Social Scale; GF:Role, Global Functioning Role Scale; MMN, Mismatch Negativity; GORT-4 ORQ, Gray Oral Reading Test Overall Reading Quotient; CTOPP PACS and APACS, Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing Phonological Awareness Composite Score and Alternate Phonological Awareness Composite Score; WRAT-III, Wide Range Achievement Test-III Reading subscale.

Note:

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Similarly, lower role functioning correlated significantly with lower GORT-ORQ (r=.25, p=.03) and processing speed (r=.26, p=.02) scores, and reduced duration MMN (r=−.27, p=.02) and intensity MMN (r=−.37, p<.01) amplitudes (see Figure 2). When entered into a stepwise regression, only intensity MMN reached significance (F2,64=16.62, β=−.219, p=.04, Adjusted R2=.32). A significant correlation was observed as well between GORT-ORQ scores and Intensity MMN (r=−.21, p=.04).

Figure 2.

Correlations between MMN amplitudes and social (left) and role (right) functioning across subjects at CHR and healthy comparison subjects. The correlations were significant across diagnostic groups (Duration MMN vs. Social functioning, r=−.44, p<.001; Intensity MMN vs. Role functioning, r=−.38, p<.01) and remained significant even after accounting for diagnostic group, neurocognitive performance, and WRAT-3 reading scores (Duration MMN vs. Social functioning, r=−.26, p=.03; Intensity MMN vs. Role functioning, r=−.25, p=.04).

4. Discussion

Consistent with previous reports, the current study found significant MMN reductions in subjects at CHR+ across three different forms of auditory deviance. CHR+ subjects also showed significant impairments in social and role functioning, consistent with studies from our group (Carrión et al., 2011; 2013; Cornblatt et al., 2012) and others (Addington et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2011; Niendam et al., 2006; Velthorst et al., 2013). Furthermore, beyond replicating previous reports on MMN reductions in CHR+ subjects, our study found significant relationships between MMN amplitudes and both social and role functioning, over and above the contributions of previously described neurocognitive impairments. Overall, these findings extend recent studies with adult patients demonstrating a link between MMN amplitudes and functioning, and implicate emerging sensory processing deficits as prevention targets for functional impairments prior to the onset of psychosis.

In addition to showing MMN deficits, CHR+ subjects showed impairments in reading ability that appear to represent a decline in ability from premorbid levels, as reflected in single-word (WRAT-3) reading scores. Consistent with the developmental dyslexia literature(Kujala et al., 2006; Lovio et al., 2012) as well as a prior schizophrenia study(Revheim et al., 2014), reading deficits were associated with MMN reductions, suggesting sensory contributions. Moreover, reading deficits in turn were associated with impaired role functioning, suggesting that they may represent an important target of intervention. In one prior CHR study(Revheim et al., 2014), isolated deficits were observed in rate, but not accuracy, and were somewhat less severe than in the present sample. In established schizophrenia, deficits were present in both reading fluency and comprehension(Revheim et al., 2006; 2014), suggesting a potential progression with reduced fluency in reading in CHR patients leading to reduced time spent in reading activities, and thus potential atrophy of abilities. Similarly, in established schizophrenia, deficits were also observed in phonological processing, which represents the ability to “sound out” novel words and is a critical component of reading. Despite the MMN deficits, CHR+ subjects did not show the phonological processing deficits seen in schizophrenia. The relative preservation of phonological processing may reflect the lesser degree of MMN deficit observed in CHR vs. established schizophrenia, and also supports early intervention to prevent further deterioration.

Overall, the present study confirms our earlier reports of social and role dysfunction in individuals at CHR+(Carrión et al., 2011). Processing speed and verbal learning were significantly correlated with social/role functioning, reinforcing the importance of cognitive dysfunction as a predictor of present dysfunction. Impairments in overall reading ability were also related to role functioning, consistent with findings in dyslexia. However, MMN amplitude contributed unique variance to functioning above and beyond neurocognitive performance, suggesting additional contributions of early sensory dysfunction. Previous studies in CHR subjects have generally not found significant relationships between MMN amplitudes and functioning. However, most studies to date have relied on global functioning measures that are confounded with symptoms (e.g., GAF), rather than measures more directly related to social and role functioning.

Our findings need to be viewed in the context of certain limitations. First, the potential impact of medication treatment on the ERP responses should be acknowledged as half the sample was receiving some type of psychotropic medication. However, there was no significant relationship between medication treatment and ERP responses. Second, our cross-sectional baseline data does not allow us to determine whether MMN deficits are predictors of long-term functional difficulties in CHR subjects. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the relationship between MMN deficits, long-term functioning, and the transition to full-blown psychosis. Nevertheless, given recent reports of long-term functional impairments in CHR subjects regardless of transition to psychosis (Addington et al., 2011), our findings highlight the importance of early intervention as basic auditory processing impairments may impact baseline functioning.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate a relationship between early auditory processing and functioning in the stages leading up to illness and provide potential pathways by which underlying biology may contribute to present dysfunction within the population meeting symptomatic CHR criteria. Regardless of transition status, CHR individuals are experiencing significant current impairments in functioning, neurocognition, and reading ability that require identification and intervention in order to limit long-term functional disability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants and entire staff of the RAP Program for their time and effort. In particular, the authors would like to thank Rita C. Barsky, Ph.D and Stephanie Snyder, Psy.D for their assistance in carrying out this study.

Funding

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): MH61523 (Dr. Cornblatt), the Conte Center for Schizophrenia Research P50 MH086385 (Dr. Javitt) the Zucker Hillside Hospital Advanced Center for Intervention and Services Research for the Study of Schizophrenia MH 074543 (John M Kane, M.D.). Supported in part by a Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (NARSAD) Young Investigator Grant (Dr. Carrión) and research partners at the Let the Sun Shine Run/Walk (Kathy and Curt Robbins, Cold Spring, MN).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

Drs. Cornblatt and Javitt designed the study and wrote the protocol. Ms. Olsen and McLaughlin, Mr. Chang, and Drs. Carrión, Auther, and Cornblatt acquired the data. Drs. Carrión, Javitt, and Cornblatt interpreted the data. Dr. Carrión wrote the first draft of the manuscript and undertook the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Financial Disclosures

Drs. Carrión, Auther, Mr. Chang, and Ms. Olsen and McLaughlin report no financial relationships with commercial interests. Dr. Cornblatt was the original developer of the CPT-IP and has been an advisor for Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Javitt has intellectual property rights for use of glycine, D-serine and glycine transport inhibitors in schizophrenia, holds equity in Glytech, and has received honoraria from Vindico, Clearview healthcare, Envivo, Rockpointe, and Sunovion.

References

- Addington J, Cornblatt BA, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Heinssen R. At clinical high risk for psychosis: outcome for nonconverters. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):800–805. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RJ, Michie PT, Schall U. Duration mismatch negativity and P3a in first-episode psychosis and individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;71(2):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad AG, Voruganti LN. The burden of schizophrenia on caregivers: a review. PharmacoEconomics. 2008;26(2):149–162. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodatsch M, Ruhrmann S, Wagner M, Muller R, Schultze-Lutter F, Frommann I, Brinkmeyer J, Gaebel W, Maier W, Klosterkotter J, Brockhaus-Dumke A. Prediction of psychosis by mismatch negativity. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;69(10):959–966. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrión RE, Goldberg TE, McLaughlin D, Auther AM, Correll CU, Cornblatt BA. Impact of neurocognition on social and role functioning in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):806–813. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrión RE, McLaughlin D, Goldberg TE, Auther AM, Olsen RH, Olvet DM, Correll CU, Cornblatt BA. Prediction of functional outcome in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(11):1133–1142. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Auther AM, Niendam T, Smith CW, Zinberg J, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. Preliminary findings for two new measures of social and role functioning in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33(3):688–702. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Carrion RE, Addington J, Seidman L, Walker EF, Cannon TD, Cadenhead KS, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Tsuang MT, Woods SW, Heinssen R, Lencz T. Risk factors for psychosis: impaired social and role functioning. Schizophr. Bull. 2012;38(6):1247–1257. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman T, Sehatpour P, Dias E, Perrin M, Javitt DC. Differential relationships of mismatch negativity and visual p1 deficits to premorbid characteristics and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;71(6):521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Coles MG, Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1983;55(4):468–484. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF. Cognitive impairment and functional outcome in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;67(10):e12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Nuechterlein KH. The MATRICS initiative: developing a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials. Schizophr. Res. 2004;72(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Gold JM, Barch DM, Cohen J, Essock S, Fenton WS, Frese F, Goldberg TE, Heaton RK, Keefe RS, Kern RS, Kraemer H, Stover E, Weinberger DR, Zalcman S, Marder SR. Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: the NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004;56(5):301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Heaton RK, Carpenter WT, Jr., Green MF, Gold JM, Schoenbaum M. Functional impairment in people with schizophrenia: focus on employability and eligibility for disability compensation. Schizophr. Res. 2012;140(1-3):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbers JE, Cutuli JJ, Supkoff LM, Heistad D, Chan C-K, Hinz E, Masten AS. Early Reading Skills and Academic Achievement Trajectories of Students Facing Poverty, Homelessness, and High Residential Mobility. Educ Res. 2012;41(9):366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi Y, Sumiyoshi T, Seo T, Miyanishi T, Kawasaki Y, Suzuki M. Mismatch negativity and cognitive performance for the prediction of psychosis in subjects with at-risk mental state. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahshan C, Cadenhead KS, Rissling AJ, Kirihara K, Braff DL, Light GA. Automatic sensory information processing abnormalities across the illness course of schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2012;42(1):85–97. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC. Sensory processing in schizophrenia: neither simple nor intact. Schizophr. Bull. 2009;35(6):1059–1064. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Doneshka P, Zylberman I, Ritter W, Vaughan HG., Jr. Impairment of early cortical processing in schizophrenia: an event-related potential confirmation study. Biol. Psychiatry. 1993;33(7):513–519. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Steinschneider M, Schroeder CE, Arezzo JC. Role of cortical N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in auditory sensory memory and mismatch negativity generation: implications for schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93(21):11962–11967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakubo Y, Kasai K. Support for an association between mismatch negativity and social functioning in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(7):1367–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Kim SN, Lee S, Byun MS, Shin KS, Park HY, Jang JH, Kwon JS. Impaired mismatch negativity is associated with current functional status rather than genetic vulnerability to schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp M, Mangalore R, Simon J. The global costs of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2004;30(2):279–293. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala T, Lovio R, Lepisto T, Laasonen M, Näätänen R. Evaluation of multi-attribute auditory discrimination in dyslexia with the mismatch negativity. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006;117(4):885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Sung K, Lee KS, Moon E, Kim CG. Mismatch negativity is a stronger indicator of functional outcomes than neurocognition or theory of mind in patients with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;48:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light GA, Braff DL. Mismatch negativity deficits are associated with poor functioning in schizophrenia patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005a;62(2):127–136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light GA, Braff DL. Stability of mismatch negativity deficits and their relationship to functional impairments in chronic schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005b;162(9):1741–1743. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light GA, Näätänen R. Mismatch negativity is a breakthrough biomarker for understanding and treating psychotic disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110(38):15175–15176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313287110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Wood SJ, Nelson B, Brewer WJ, Spiliotacopoulos D, Bruxner A, Broussard C, Pantelis C, Yung AR. Neurocognitive predictors of functional outcome two to 13 years after identification as ultra-high risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2011;132(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovio R, Halttunen A, Lyytinen H, Näätänen R, Kujala T. Reading skill and neural processing accuracy improvement after a 3-hour intervention in preschoolers with difficulties in reading-related skills. Brain Res. 2012;1448:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A, Revheim N, Butler PD, Guilfoyle DN, Dias EC, Javitt DC. Impaired magnocellular/dorsal stream activation predicts impaired reading ability in schizophrenia. Neuroimage Clin. 2012;2:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EC, Carrión RE, Cornblatt BA, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Heinssen R, Seidman LJ, the N.g. The Relationship of Neurocognition and Negative Symptoms to Social and Role Functioning Over Time in Individuals at Clinical High Risk in the First Phase of the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study. Schizophr. Bull. 2014 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Cannon T, Ventura J, McFarlane W, Perkins DO, Pearlson GD, Woods SW. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr. Bull. 2003;29(4):703–715. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Somjee L, Markovich PJ, Stein K, Woods SW. Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):863–865. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, Stein K, Driesen N, Corcoran CM, Hoffman R, Davidson L. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(4):273–287. doi: 10.1023/a:1022034115078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niendam TA, Bearden CE, Johnson JK, McKinley M, Loewy R, O’Brien M, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Cannon TD. Neurocognitive performance and functional disability in the psychosis prodrome. Schizophr. Res. 2006;84(1):100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvet DM, Carrion RE, Auther AM, Cornblatt BA. Self-awareness of functional impairment in individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1111/eip.12086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J. Center for Psychological Studies. Nova Southeastern University; Fort Lauderdale, FL: 1994. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiologic Version. [Google Scholar]

- Perez VB, Woods SW, Roach BJ, Ford JM, McGlashan TH, Srihari VH, Mathalon DH. Automatic Auditory Processing Deficits in Schizophrenia and Clinical High-Risk Patients: Forecasting Psychosis Risk with Mismatch Negativity. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revheim N, Butler PD, Schechter I, Jalbrzikowski M, Silipo G, Javitt DC. Reading impairment and visual processing deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2006;87(1-3):238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revheim N, Corcoran CM, Dias E, Hellmann E, Martinez A, Butler PD, Lehrfeld JM, DiCostanzo J, Albert J, Javitt DC. Reading deficits in schizophrenia and individuals at high clinical risk: relationship to sensory function, course of illness, and psychosocial outcome. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014;171(9):949–959. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13091196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh M, Valmaggia L, Broome MR, Dutt A, Lappin J, Day F, Woolley J, Tabraham P, Walshe M, Johns L, Fusar-Poli P, Howes O, Murray RM, McGuire P, Bramon E. Reduced mismatch negativity predates the onset of psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2012;134(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley AM, Ward PB, Catts SV, Michie PT, Andrews S, McConaghy N. Mismatch negativity: an index of a preattentive processing deficit in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 1991;30(10):1059–1062. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis-Vivanco R, Mondragon-Maya A, Leon-Ortiz P, Rodriguez-Agudelo Y, Cadenhead KS, de la Fuente-Sandoval C. Mismatch Negativity reduction in the left cortical regions in first-episode psychosis and in individuals at ultra high-risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2014;158(1-3):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd J, Michie PT, Schall U, Karayanidis F, Yabe H, Näätänen R. Deviant matters: duration, frequency, and intensity deviants reveal different patterns of mismatch negativity reduction in early and late schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;63(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht D, Krljes S. Mismatch negativity in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2005;76(1):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht D, Schmid L, Koller R, Vollenweider FX, Hell D, Javitt DC. Ketamine-induced deficits in auditory and visual context-dependent processing in healthy volunteers: implications for models of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57(12):1139–1147. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velthorst E, Nelson B, Wiltink S, de Haan L, Wood SJ, Lin A, Yung AR. Transition to first episode psychosis in ultra high risk populations: does baseline functioning hold the key? Schizophr. Res. 2013;143(1):132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner RK, Torgesen JK, Rashotte CA. CTOPP: Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing. PRO-ED; Austin, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Revised (WAIS-R) The Psychological Corp.; San Antonio, Texas: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 3rd ed. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Whitford V, O’Driscoll GA, Pack CC, Joober R, Malla A, Titone D. Reading impairments in schizophrenia relate to individual differences in phonological processing and oculomotor control: evidence from a gaze-contingent moving window paradigm. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2013;142(1):57–75. doi: 10.1037/a0028062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wible CG, Kubicki M, Yoo SS, Kacher DF, Salisbury DF, Anderson MC, Shenton ME, Hirayasu Y, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, McCarley RW. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of auditory mismatch in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):938–943. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederholt J, Bryant B. Gray Oral Reading Tests (GORT-4) 4th ed. Pro-Ed; Austin, TX: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS. Wide Range Achievement Test–Revision 3. Jastak Association; Wilmington, DE: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn JK, Sugar C, Horan WP, Kern R, Green MF. Mismatch negativity, social cognition, and functioning in schizophrenia patients. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.