Abstract

Researchers have examined selection and influence processes in shaping delinquency similarity among friends, but little is known about the role of gender in moderating these relationships. Our objective is to examine differences between adolescent boys and girls regarding delinquency-based selection and influence processes. Using longitudinal network data from adolescents attending two large schools in AddHealth (N = 1,857) and stochastic actor-oriented models, we evaluate whether girls are influenced to a greater degree by friends' violence or delinquency than boys (influence hypothesis) and whether girls are more likely to select friends based on violent or delinquent behavior than boys (selection hypothesis). The results indicate that girls are more likely than boys to be influenced by their friends' involvement in violence. Although a similar pattern emerges for nonviolent delinquency, the gender differences are not significant. Some evidence shows that boys are influenced toward increasing their violence or delinquency when exposed to more delinquent or violent friends but are immune to reducing their violence or delinquency when associating with less violent or delinquent friends. In terms of selection dynamics, although both boys and girls have a tendency to select friends based on friends' behavior, girls have a stronger tendency to do so, suggesting that among girls, friends' involvement in violence or delinquency is an especially decisive factor for determining friendship ties.

Keywords: peer influence, social networks, gender

Criminologists generally agree that delinquency and crime are committed disproportionately by males and that the gender gap in offending becomes even larger when the focus turns toward violent offenses (Steffensmeier et al., 2005). Two explanations have been offered for the gender gap in offending. “Differential exposure” explanations argue that boys and girls are differentially exposed to risk factors that are conducive to crime or delinquency. “Differential reaction” explanations argue that although boys and girls may be exposed to similar risk factors, they will be affected differently by them. Although these explanations are not mutually exclusive, criminologists often draw on one or the other especially when considering gender differences in delinquency. One factor often used to evaluate these perspectives is the role of delinquent peer exposure. Indeed, research has suggested that peer delinquency can account for some of the gender gap in delinquency (Mears, Ploeger, and Warr, 1998; Piquero et al., 2005). That is, girls are exposed to lower levels of peer delinquency than boys (differential exposure), and when exposed, girls are influenced differentially by delinquent peers compared with boys (differential reaction). In addition, there is increasing awareness of the role of friendship selection in shaping peer-delinquency similarity and the need to account for selection processes when examining the role of delinquent peer exposure for youths' involvement in delinquency. The goal of the current study is to use longitudinal network models to test whether girls are differentially influenced by their friends' delinquency (differential reaction) and whether girls are more likely than boys to make friends based on their friends' delinquent behaviors (selection).

The number of studies examining the effects of peers on delinquency has grown substantially over the last two decades (Brechwald and Prinstein, 2011; Haynie, 2001; Matsueda and Anderson, 1998; Weerman and Hoeve, 2012; Weerman and Bijleveld, 2007; Zimmerman and Messner, 2010). Much of this research has suggested that the association between an adolescent's delinquent behavior and his or her friends is stronger than that of other risk factors considered (Birkbeck and LaFree, 1993; Warr, 2002). Recently, scholars have argued that prior findings are compromised by overlooking the network structures in which adolescents are embedded (Haynie, 2001; Haynie and Osgood, 2005; Weerman and Hoeve, 2012). In response, research has begun to apply longitudinal network methods to determine the role of selection and influence processes in shaping delinquency similarity among adolescents who are friends (Dijkstra et al., 2010; Weerman, 2011; Weerman and Bijleveld, 2007).

Absent from the longitudinal network studies on delinquent peers has been a focus on gender dynamics and the role they play in shaping delinquency similarity among friends. This absence is surprising as many studies have indicated that girls' friendships differ in several important ways from boys' friendships (Erwin, 1998; Rose and Rudolph, 2006; Weerman and Hoeve, 2012). Additionally, recent research has indicated gender variation in the association between peer delinquency and individual delinquency (Zimmerman and Messner, 2010). Such differences may imply that peers influence girls differently than boys, or that girls are more likely than boys to select friends based on shared delinquency profiles.

The current study adds to the understanding of gender dynamics in delinquency by applying dynamic longitudinal network methods to determine whether gender moderates the effect of influence and selection on the tendency for adolescents to be similar to their friends. We focus on two outcomes: involvement in violence or nonviolent delinquency. Using longitudinal friendship network data from adolescents attending two large schools participating in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (hereafter, AddHealth), we test whether girls are more likely to be influenced by friends' behavior than boys and whether girls are more likely to select friends based on violent or delinquent behavior than boys.

Background

The role of friend and peer influence is central to explanations of crime, delinquency, and other problem behaviors. Compared with children and adults, adolescents attribute greater importance to friends, spend more time socializing with friends, and are more strongly influenced by friends' behaviors and attitudes (Giordano, Cernkovich, and Holland, 2003). Not surprisingly, then, one of the most consistent findings in the criminological literature is that individuals with delinquent friends are likely to be delinquent themselves. Robust associations between peer and individual delinquency have led some to argue that peer processes are among the most important in explaining delinquent outcomes, regardless of the type of delinquency considered (Akers, 1973; Haynie, 2001; Warr, 2002).

Even though all agree that there is similarity in delinquency among friends, prominent criminological theories present different mechanisms by which similarity emerges. In particular, control theories (Gottfredson and Hirschi, 1990; Hirschi, 1969) and influence theories (Akers, 1973; Sutherland, 1947) are prevailing perspectives that discuss the role of peers for adolescent delinquency. However, these theories offer opposing explanations regarding the ways that peers shape individual delinquency. Accordingly, criminologists have focused on different features of peer contexts to assess the plausibility of the different proposed theoretical mechanisms.

Gottfredson and Hirschi's (1990) general theory of crime describes the process through which individuals self-select into peer groups. In their 1990 article, they argued that peers have little to no influence on individual offending; rather, individual variation in self-control (i.e., the ability to regulate impulsive behavior), which is relatively stable by early adolescence, shapes how adolescents cluster together in peer settings. Delinquent adolescents with low self-control are likely to end up with other delinquents as friends, as a result of their similar levels of self-control. Apart from determining the types of friends one makes, low self-control is also a primary cause of delinquent behavior. Thus, delinquency and associations with delinquent others are both directly caused by low self-control.1 Therefore, according to control theorists, the association between delinquent peers and individual offending is spurious and the peer-delinquency association is a result of selection processes and not because friends' influence individual delinquency.

In contrast to traditional control theories, Sutherland's (1947) differential association theory suggests that delinquency is learned from intimate social relationships with others, such as friendships, through the transference of attitudes and definitions that encourage criminal behavior. Akers's (1973) social learning theory builds on this by emphasizing behavioral modeling and operant conditioning's role in the learning process. This model assumes that the adoption of delinquent behavior occurs through the imitation of peers' behavior and the observation of its positive or negative consequences. Both Sutherland's and Akers' theories represent prototypical influence theories in their argument that delinquency, like any behavior, is learned in intimate relationships, including friendships. These theories then explain the peer-delinquency association as a result of influence dynamics.

In sum, two prominent criminological theories—control and influence theories—offer differing explanations for the similarity of delinquency found among friends. Social learning theory and differential association theory emphasize influence as the driving mechanism, whereas control theories of crime emphasize the role of selection in producing delinquency similarity. To address this longstanding debate, researchers have begun using longitudinal social network analyses to evaluate the relative explanation of influence and selection for understanding adolescent delinquency and the contribution of peers (Carrington, 2011).

A social network perspective offers a unique method to study complex interdependencies between individuals. It emphasizes both the configuration of ties connecting individuals in a social structure and the characteristics of individuals in that structure to explain delinquent outcomes. Scholars interested in applying a social network perspective to understand delinquency require data on the ties or connections among individuals within a particular setting. Although ties can take on different forms, studies of adolescent behavior most often examine friendships. This perspective argues that the behavior and structure of adolescent friendship networks offers great explanatory power for understanding delinquency and other social behavior.

In addition, a network perspective emphasizes the need to account for important structural characteristics of networks that play a key role in shaping behavior similarity among connected individuals. This includes the density of network ties (the ratio of number of connections to number of possible connections), reciprocity (the tendency for nominated friends to reciprocate friendships), triadic closure (i.e., the tendency for friends of friends to become friends), and the tendency toward homophily in friendship based on characteristics of individuals in the network (e.g., gender, race, and age). Most important for our study, a social network perspective expands on prevailing criminological theories by arguing that embeddedness in social networks must be analyzed as a dynamic process in which adolescents are making and losing friends and maintaining or changing behavior over time. This unique approach allows us to control for important network properties to evaluate more accurately how selection and influence processes bear on changes in violence or nonviolent delinquency among adolescents and their friends.

Longitudinal Network Approaches to Peer Delinquency

Recent years have witnessed growing interest in applying longitudinal network methods to understand criminal and delinquent outcomes. Much of this work has been spurred on by the development of new stochastic actor-oriented models (SAOMs) that allow for the analysis of the coevolution of networks and behavior (Snijders, 1996, 2001; Snijders, Steglich, and Schweinberger, 2007). In particular, SAOMs allow one to differentiate the tendencies for youth to select friends like themselves (selection) from the propensity to change behavior to be similar to that of their friends (influence).

To address the relative importance of selection and influence, Baerveldt, Rossem, and Volker (2008) drew on data from students in 16 Dutch high schools and found that although influence operated in all of the schools resulting in similarity in friends' delinquency, evidence for selection was found in only 4 of the 16 schools and depended in part on network differences between the schools. Similarly, using comparable data, Weerman (2011) also found limited evidence that selection operates to induce delinquency similarity once other network properties are accounted for. Rather, he found evidence that influence was more important, although he noted smaller influence effects compared with prior non–network-based studies (Weerman, 2011). Using longitudinal network data from students in Sweden, researchers found evidence of both selection and peer influence playing a role in friends' delinquency similarity (Burk, Kerr, and Stattin, 2008; Burk, Steglich, and Snijders, 2007); however, peer influence played a larger role in shaping behavioral similarity among friends. In contrast, work by Knecht (2008) using the Dutch data found evidence of selection for delinquency and alcohol use with no significant evidence of influence operating to shape behavior. A more recent study also concluded that selection is more evident than influence in explaining peer similarity in alcohol use among Dutch adolescents (Knecht et al., 2010). Overall, this growing body of research has so far provided mixed evidence regarding the role that selection and influence play in shaping adolescent delinquency. As there has been no consistent pattern in prior research and some evidence for both the role of selection and influence, we anticipate that in our sample of U.S. school-aged youth, both influence (hypothesis 1) and selection (hypothesis 2) will play roles shaping the violence or nonviolent delinquency similarity of connected peers.

Gender and Peer Influence

Absent from almost all work evaluating both selection and influence processes in delinquency are considerations of how gender shapes selection or influence mechanisms. Although many studies found similarities between girls' and boys' friendships (e.g., both value trust in friendships), they noted important gender differences in the nature and structure of friendships. Boys tend to have larger friendship networks oriented around common activities (e.g., sports), whereas girls have smaller networks with one or a few best friends (Benenson, 1990). Girls are more likely than boys to characterize friendships as having high intimacy, emotional involvement, and confidentiality (Waldrop and Halverson, 1975).

Girls also may communicate in different ways than boys by exhibiting higher levels of responsiveness, reciprocity, and harmony in their dialogue with one another (Dishion et al., 2004; Piehler and Dishion, 2007). Others suggested that girls also feel more empathy and prosocial feelings toward their friends than boys (Rose and Rudolph, 2006). Additionally, girls' friendships often are characterized as representing sources of social control that suppress and discourage delinquent behavior, whereas delinquency is more likely to be encouraged among boys' friendship groups (Brown, 2003). Boys also have friendship networks characterized by more hierarchy, greater emphasis on activities, and less inclination to discuss intimate matters with friends than those of girls (Rose and Rudolph, 2006). A common theme that has emerged from these studies is that boys are more likely to do things with friends, whereas girls are more likely to discuss personal matters with friends.

As a result of gender differences in friendship relationships, it seems likely that gender will alter peers' influence on girls' and boys' involvement in delinquency. On the one hand, girls may be more influenced by friends' behavior (whether prosocial or delinquent) than boys. This greater influence may be a result of girls being more emotionally invested in their friendships and more likely to disclose intimate matters with friends than boys, resulting in girls' greater investment in their friendships (Rose and Rudolph, 2006). This greater investment in friendships is important to consider as evidence indicates that friends are especially influential at higher levels of friendship quality (Agnew, 1991). If girls are more emotionally invested in their friendship relationships than boys, then friends' participation in either prosocial or delinquent behavior may be especially important in shaping girls' involvement in delinquency.

A related argument can be made regarding greater network cohesion and closure operating in girls' friendship networks compared with those of boys. Peer groups composed of mostly female adolescents tend to exhibit higher levels of cohesion (e.g., density), reciprocation of friendship nominations, stability in friendships over time, and network closure than groups composed of largely boys (Kreager, Rulison, and Moody, 2011). This greater cohesion and network closure combined with girls' more intimate friendship relations suggest that acquiescing to group norms and behavior is likely to be more important for girls than for boys.

Developmental psychologists also have noted that maintaining interpersonal relationships—including friendships—is particularly important for adolescent girls' sense of self and self-esteem (Impett et al., 2008). The importance of maintaining friendships for girls' mental health may lead them to engage in inauthentic behavior—actions that are incongruent with what one thinks and feels (Impett et al., 2008)—to avoid relationship conflict with peer group members (Brown and Gilligan, 1992). Girls' enhanced desire to maintain harmony within their friendship groups through behavioral congruence with their friends may make them more susceptible to peer influence than boys.

Moreover, because delinquency, especially violence, is generally less condoned among girls, girls may need additional encouragement from their friends to engage in this type of gender non-normative behavior. Friends' involvement in violence or delinquency may serve this purpose and act as a more critical factor in determining whether girls become involved in violence or delinquency compared with boys. In contrast, because it is more socially acceptable for boys to engage in violence or delinquency, friends' involvement in delinquency may matter less for boys' involvement. That is, boys may be drawn to risky behavior regardless of their friends' participation. Overall, this possibility suggests that friends' behavior will be more influential for girls than for boys in shaping their involvement in delinquency.

On the other hand, it has been argued that girls may be less influenced by friends' delinquent behavior than boys. As a result of the greater emphasis placed on protecting girls' virtue and keeping them safe (Steffensmeier and Allan, 1996), female friendships are likely to be supervised more closely by parents than are boys' friendships. Female friends are more likely to meet in places supervised by parents and other adults, whereas male friends spend more time in public settings away from family and other supervision where friends have greater opportunities to participate in delinquency (McCarthy, Felmlee, and Hagan, 2004). This body of literature has suggested that gender norms and values may offer girls greater immunity (than boys) from any influence of peers they encounter.

Rather than offering immunity, gendered norms and values may operate to make boys more susceptible to peer influence toward violence or delinquency. That is, boys may face greater pressure to subscribe to friends' behavior because of the greater status hierarchy and competitive nature involved in male friendships (Agnew, 2009). Male friendships also are more prone to displays of masculinity, competition, risk taking, flaunting of boundaries, and character contestations that often are associated with delinquent or violent behavior (Steffensmeier and Allan, 1996). Therefore, friendship dynamics among boys may increase the likelihood that 1) boys' activities involve delinquency or violence and 2) boys face more pressure to go along with the group when it comes to participating in any group activities.

Empirical Evidence on Gender Differences in Peer Influence

Because the body of literature reviewed previously offers competing arguments for gender differences in peer influence, an examination of empirical studies of this particular topic is warranted. Several studies have investigated whether girls are more or less influenced by friends' delinquency than boys. The bulk of this prior work has reported similarly sized correlations between boys' and girls' individual delinquency and that of their friends (Hartjen and Priyardarsini, 2003; Laird et al., 2005; Mears, Ploeger and Warr, 1998). Meta-analyses of gender differences in the correlates of delinquency have found that the effect of friends' delinquency on respondent's delinquency is similar for boys and girls (Hubbard and Pratt, 2002; Simourd and Andrews, 1994; Wong, Slotboom, and Bijleveld, 2010). In general, this body of research has found that although boys are more likely than girls to have delinquent friends, influence dynamics operate similarly across gender when girls are exposed to delinquent friends.

Although most studies have reported that the influence of delinquent friends is similar for boys and girls, a few notable studies have found gender differences in the relationship between friends' and individual delinquency. Mears, Ploeger, and Warr (1998) found that boys were more strongly affected than girls by their delinquent friends. Similarly, Piquero et al. (2005) found that friends' delinquency had stronger effects on boys' delinquency than on that of girls.2 In contrast, Zimmerman and Messner (2010) found that friends' violence was more strongly associated with girls' violent behavior than that of boys. These latter authors argued that girls are more influenced by peers than boys are a result of the more intimate and emotionally invested friendships characterizing girls' friendships.

A limitation of these studies, however, is that they have not used network data, instead relying on reports by respondents on the extent to which their friends participate in delinquency. Basing measures of peer delinquency on respondents' reports of their friends' behavior (rather than directly collecting the information from the friends themselves) may lead to overestimating the association between peer and individual delinquency because of the tendency for individuals to project their own behavior onto their friends (Haynie, 2001; Jussim and Osgood, 1989). Moreover, gender norms may operate to make boys more likely to overreport friends' misbehaviors (or to perceive higher levels) and girls less likely to do so, resulting in increased avenues for error to contaminate perceptual estimates of delinquent peer exposure. To address this concern, studies have begun to use network data and measured peer delinquency directly from identified friends. For instance, Haynie and Osgood (2005) found that peer delinquency had a modest effect on individual delinquency and that these effects were similar for boys and girls. Similarly, Brendgen, Vitaro, and Bukowski (2000) reported that peer delinquency had a short-term effect on individual delinquency that was similar for boys and girls. In contrast, a more recent study by Weerman and Hoeve (2012) drew on school-based friendship network data representing a sample of students attending secondary schools in a major Dutch city to examine gender differences in peer influence. Using multivariate analyses and two waves of data, these authors found that exposure to delinquent peers had a slightly larger effect for girls than for boys. Additionally, a self-report measure of deviant peer pressure was significantly associated with girls' delinquency but not with that of boys. This latter study provided some evidence that friends' behavior may be more influential for girls than for boys, perhaps as a result of the more intimate nature of girls' friendships providing greater avenues for peer influence to operate.

In sum, the literature has offered a mixed picture of whether girls or boys are more influenced by friends' delinquency. On the one hand, because girls are supervised more closely by parents and other adults, they may be less influenced by friends' behavior compared with boys. Alternatively, because of the greater emotional investment and intimacy with friends, the greater network closure among female friendships, and a greater desire to acquiesce to group norms in order to avoid conflict or peer rejection, girls may be more influenced by friends' behavior whether prosocial or delinquent. Boys, on the other hand, may be drawn to risky behavior such as delinquency or violence regardless of their friends' behavior. Based on these latter arguments, the more recent findings from Zimmerman and Messner (2010) and Weerman and Hoeve (2012), and consistent with previous findings regarding gender differences in friendships, we hypothesize that girls will be more influenced toward the average level of their friends' violent or delinquent behavior compared with boys (hypothesis 3).

Ultimately, whether girls are more or less influenced by peers remains an unanswered question because the prior studies examining gender differences in peer influence could not incorporate longitudinal network models allowing for the simultaneous estimation of both selection and influence parameters. As discussed, research that applies dynamic longitudinal network methods allows for the estimation of selection and influence parameters simultaneously, while accounting for other important characteristics of the friendship network. No published work has used these methods to evaluate whether influence and selection processes on delinquency are moderated by gender. In addition, no work to our knowledge has considered whether selection processes can help explain why girls experience peer-delinquency homophily.

Gender and Selection

Empirically, it has yet to be determined whether selection processes toward delinquency operate differently among boys and girls. However, there is some reason to expect that selection processes may be more important for girls than for boys. The idea that adolescents prefer similar individuals as friends has a long history in the social sciences (Homans, 1974; Lazarsfeld and Merton, 1954). Individuals have a tendency to select similar individuals as friends because those who are similar (i.e., sociodemographic background, attitudes, and behaviors) tend to have more common experiences to draw on, making these friendships easier to initialize, more rewarding, and more durable. Because girls tend to have smaller and more intimate friendship networks than boys, and because they are more likely to disclose intimate feelings and experiences, girls may be more discerning about whom they select as friends. In particular, girls may be more likely to consider carefully the behavior of their potential friends, especially that behavior that is inconsistent with gendered norms and values such as violence or delinquency.

Moreover, because gender norms are more likely to stigmatize delinquency, especially violence among girls, nondelinquent girls may be especially likely to spur violent or delinquent adolescents as friends. In contrast, violent or delinquent girls who are engaging in more non-normative gender behavior may be especially motivated to select other similarly behaved friends to find a supportive or accepting environment for their behavior. This position implies that the delinquent or violent behavior of a friend may be a critical factor determining whether girls select one another as friends.

Boys, in contrast, have larger, more fluid networks that often are organized around shared activities or space (Clampet-Lundquist et al., 2011). In this sense, the overlap in shared activities or interactional contexts may take precedence over the delinquent behavior of friends when boys consider potential friends. In addition, because delinquency is less condoned or stigmatizing among boys, boys may be less likely to consider the delinquent behavior of others (or be turned off by potential friends' delinquency) when selecting friends. Other selection factors, such as overlapping involvement in sports or other extracurricular activities, may take center stage for boys' friendship relationships. Considering how gendered processes are constructed and enacted, especially regarding the meaning and display of delinquency and violence among adolescent friendship groups, we hypothesize that selection processes will be more important in explaining violence or delinquency similarity among girls than among boys (hypothesis 4).

Data and Methods

AddHealth is a nationally representative longitudinal school-based study that explores the etiology of health outcomes and behaviors among young people in the United States. All U.S. high schools that included an 11th grade and had at least 30 enrollees were eligible for participation. A random sample of 80 high schools was compiled that was stratified by region, urbanicity, school type, ethnic makeup, and size. Each high school's largest feeder school was recruited when available, resulting in a sample of more than 130 schools ranging in size from fewer than 100 students to more than 3,000. More than 90,000 respondents completed in-school surveys between 1994 and 1995. Demographic information collected in this survey was used to select respondents for in-home interviews, which gathered more detailed information on respondents' delinquency. Roughly 20,000 adolescents completed the first in-home interview, whereas nearly 15,000 respondents completed wave II interviews, which took place approximately 1 year after the first in-home interview.

Sample

As a subset of the larger, more representative, school sample, the AddHealth research team attempted to interview in depth every student attending or on the rosters of 16 participating schools (14 small and 2 large) as part of the first two in-home interviews (referred to as the saturation sample). Because every student attending this saturation sample was interviewed at multiple time points, this subset of the AddHealth data contains information on a wide variety of attributes for almost every youth whose name appeared on school rosters. In addition, because every student identified their school friends at two waves of data collection, complete school networks can be replicated at two time points. Accordingly, we restrict our analysis to schools from the saturated sample.3 Of the 16 schools in the saturated sample, we focus on the two largest schools in this sample because they seem to be more representative of the average school experience (especially in contrast to the other saturated schools that contained very small student populations, typically less than 100 students per school). It is difficult to argue that friendship and behavior dynamics operate similarly in schools of such disparate size. Additionally, these smaller (excluded) saturated schools exhibited much lower involvement in violence or delinquency (and subsequently less variation) than the two larger saturated schools, which had greater variation in violence or delinquency and average levels comparable with schools in the larger more representative sample. One of the two large schools included in this study is a racially homogenous (primarily White) suburban school from the Midwest (often labeled “Jefferson” in the literature), whereas the other is a larger, racially heterogeneous urban school located on the West Coast (labeled “Sunshine”). These two schools are the largest schools with longitudinal network data, providing the greatest (although still limited) statistical power to detect gender differences in influence and selection parameters. We further restrict our sample to respondents who were in Grades 9–11 at the time of wave I because respondents who were in the Grade 12 at wave I were not interviewed at wave II. This approach (and sample) is similar to that used by de la Haye et al. (2013) and Haas and Schaefer (2014), who also studied friendship networks observed in the AddHealth study. After these selection criteria, our final sample consists of 1,857 adolescents nested within the two large schools from the saturated sample.

Measures

Friendship Networks

During both interviews and surveys, respondents identified up to five of their closest male and female friends (for a possible total of 10 friends).4 Errors with a small number of data collection computers at wave I resulted in some participants only being able to nominate one best male and one best female friend. This limitation affected approximately 5 percent of our analytic sample. For these respondents, we replaced the non–best-friend wave I nominations with friendship nominations from the initial in-school survey, which occurred roughly 6 months prior to the wave I in-home interview. Because these respondents have a longer time span between when the nominations were collected, they have had more time to change friendships compared with the rest of the sample. We adjust our models for this by constructing a binary variable restricted nominations (1 = yes), which indicates whether the respondent was affected by the error. We use the measure to allow the model rate parameters to vary depending on the amount of time a student had to alter his or her friendship network.

Dependent Variables

We focus on change in two types of behaviors, violence or nonviolent delinquency. For each outcome, we construct scales that capture the extent of involvement in the respective behavior at each interview wave. To scale the outcomes, we use Rasch models with delinquency items nested within individuals. Similar to item-response theory models, our Rasch models quantify latent levels of delinquency based on the extent of involvement in the delinquent behaviors in question. To measure the outcomes, we extract the empirical Bayes (EB) adjusted intercepts from unconditional Rasch models of each delinquency measure, measured at each study wave (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). The major benefit of this approach to measuring delinquency compared with simply using an additive scale is that Rasch models provide unequal weights to certain items based on their “severity,” or the frequency in which items occur within the sample. Thus, our measures of delinquency are sensitive to variation in the severity of certain offenses (e.g., fist fighting with others vs. stabbing someone). Because the SIENA software package requires that behavioral variables are integers equal to or greater than zero, we add to each EB adjusted intercept the minimum value to each respective measure (round the value to the nearest integer).

We examine both violence and nonviolent delinquency as outcomes. Violence captures involvement in the following seven items that occurred within the 12 months prior to the respective interview: 1) getting in a serious physical fight, 2) purposefully and seriously injuring someone, 3) taking part in a group fight, 4) using or threatening someone with a weapon, 5) pulling a knife or gun on someone, 6) stabbing or shooting someone, and 7) using a weapon in a fight (αwI = .770; αwII = .801). Our delinquency measure captures respondents' involvement in the following eight items prior to the respective interview: 1) shoplifting, 2) stealing something worth less than $50, 3) painting graffiti, 4) purposefully damaging property, 5) stealing a car, 6) stealing something worth more than $50, 7) burglarizing a building, and 8) selling drugs (αwI = .767; αwII = .765).

Control Variables

We include several variables to take into account confounding factors. We control for depression symptoms because this is associated with delinquency among adolescents (Haynie and South, 2005). We measure depression with 19 items adopted from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977) that measure prevalence of emotional and mental health problems (e.g., “felt sad”) throughout the past week. Item responses ranged from 0 (“never”) to 3 (“all or most of the time”). Our measure is composed of the mean of the standardized items (α = .822). We also include a measure of impulsivity, as it is positively associated with delinquency (Gottfredson and Hirschi, 1990). Following Vazsonyi, Cleveland, and Weibe (2006), our measure of impulsivity consists of four variables indicating self-control, such as “when you have a problem to solve, one of the first things you do is get as many facts about the problem as possible” (α = .742). Initial responses ranged from 1 (“strongly agree”) to 5 (“strongly disagree”). We measure impulsivity by calculating the mean of the standardized items, with larger values indicating higher impulsivity. In addition, we include a control for verbal ability as prior research found this to be associated with delinquency and violence (Bellair and McNulty, 2005). Verbal ability is measured using an abbreviated version of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised.

We include controls for age, female gender (female = 1), family structure (single-parent household = 1), receipt of public assistance (yes = 1), and a measure of socioeconomic status (SES) that consists of the mean of the standardized values of parental occupational status and education level, which refers to the parent with the highest occupational status or education level. Other important network characteristics are included as controls and will be described in the Network Effects section.

Analytic Strategy

To test our hypotheses, we use SAOMs of network dynamics developed initially by Snijders et al. (2007) for the analysis of coevolution of networks and actor behaviors. These models facilitate the simultaneous examination of the effect of peers on behavior (i.e., influence from friends) and the effect of behavior on network structure (e.g., selection based on common behavior). SAOMs are useful for estimating the strength of selection and influence processes among networks of actors while taking into account network dependencies (e.g., triadic closure and reciprocity) and selection on the basis of other characteristics (e.g., race and gender) that also contribute to network evolution. SAOMs were estimated using the SIENA statistical analysis package (Ripley, Snijders, and Preciado, 2013).

Model specification entails theory- and data-driven selection of terms referred to as effects, which represent processes that are hypothesized to drive friendship and behavior changes among study respondents. Each specified effect represents an additive term within a utility function. The utility function captures the value of the current state of the network and behavior(s) from the perspective of an actor (often referred to here as the focal actor or ego) compared with alternative states that are made possible to the actor through a small change that an actor could make in the form of adding or removing a friend or altering a behavior. SIENA estimates effect parameters that, when used in simulation, optimally reproduce the observed changes in the network and behaviors. Next, we define the effects that compose the utility function for actors in our models.

Network Effects

Recent research has highlighted the importance of network processes driving peer group homogeneity in adolescent networks (Goodreau, Kitts, and Morris, 2009; Haas and Schaefer, 2014; Young, 2011). Failing to include important network effects in our models may yield biased selection parameters. All of our models include five pure network effects that depend not on actor characteristics but only on an actor's incoming and outgoing network ties. The density effect controls for the overall density of the school network. Also known as the outdegree effect, this effect controls for the baseline probability of extending ties to others. The estimated parameter for the density effect is usually negative (as extending ties is costly to the actor) and is analogous to an intercept parameter in a logistic regression model. The probability of a tie occurring in a network is likely dependent on the presence of its reciprocal tie. Therefore, we include the reciprocity effect, which allows the model to capture tendencies for actors to reciprocate friendship choices by allowing the probability of a tie to depend on the existence of its reciprocal tie.

We include two effects for triadic network processes that are known to shape adolescent friendship networks. Transitivity is central to tie formation in general (Granovetter, 1973). For instance, a tie from i to j is typically more likely to appear when there exists a third actor k who nominated j and who has been nominated by i (i.e., i → k → j often leads to or supports the existence of i → j). We model this process with the transitive triplets effect, which takes into account the tendency for individuals to extend or maintain ties to the friends of their friends. Ripley, Snijders, and Preciado (2013) suggested that when local hierarchy is present in the network, as is expected in a high-school friendship network, it can be captured in the model by including the transitive triplets effect along with the three-cycles effect. The “three” in three cycles represents the fact that the structure is triadic, and “cycle” implies that the ties are configured cyclically (i.e., i → j → k → i). Each tie in such a structure is said to be more likely to appear or be maintained when the other two exist. The expected direction of the parameter is negative because of the expected hierarchical structure. The final pure network effect, indegree popularity, captures an expected increase in the likelihood of friendship nominations for proportional increases in existing received nominations. Indegree popularity can be thought of as preferential attachment and analogous to a network-based “Matthew effect.”

Our models also include covariate-based network effects that capture actors' tendencies to select others on the basis of exogenous personal characteristics (e.g., race, gender, and impulsivity) as well as the endogenous behavior of primary interest.5 Two common types of covariate-based effects, and those most prominent in this study, are similarity (for continuous variables) and same (for categorical variables) covariate effects. These effects capture the tendency of actors to select others who are similar (e.g., similar levels of depression) or identical (e.g., same race) with regard to personal characteristics. A similarity effect for delinquency involvement (either violence or nonviolent delinquency) allows for evaluation of the delinquency-based selection hypotheses. Other variables used with the similarity effect in our models include age, vocabulary ability, impulsivity, depression, and socioeconomic status. Variables included using the same effect are gender, race, romantic involvement status, public assistance status, and single-parent household status. All of these measures capture the tendency for respondents to select friends that are similar or the same as themselves based on these characteristics.

Two additional and less prominent covariate-based effects in our models are covariate activity (also called ego effects) and covariate popularity effects (also called alter effects). Both allow general tie creation and maintenance by an individual to depend on the value of a particular covariate of the focal actor (activity) or of the actor under consideration for nomination by the focal actor (popularity). For example, it could be that girls nominate more friends (higher activity), resulting in a positive ego female estimate, and they are nominated less frequently (lower popularity), resulting in a positive alter female estimate. We include both ego and alter effects for the female covariate and the behavioral variables violence or nonviolent delinquency.

Behavioral Effects

We include several effects that model changes in actors' violent or delinquent behavior with additive terms in a separate but associated utility function. The linear shape effect models the baseline tendency of the behavior across study waves net of other included behavior effects. The quadratic shape effect allows actors' behavior to depend on the current state of the actors' behavior. Together, the linear and quadratic shape effects describe the shape of the distribution of the behavior variable. Effects from covariates are interactions with the linear shape effect. For example, a positive estimate of the effect of age on delinquent behavior suggests that older adolescents tend to have higher levels of the behavior.

We test our influence hypotheses with average similarity effects, which allow changes in an actor's behavioral variable (e.g., violence or delinquency) to depend on the current state of the behavioral variable among the actor's connected peers (i.e., peers' average level of violence or nonviolent delinquency). A positive parameter for such an effect would indicate that actors tend to adjust their behavior toward the average behavior of their peers, whether high or low, thus, providing evidence that changes in the behavior are attributed to peer influence.

Modeling Strategy

We model each of two delinquent behaviors (violence or nonviolent delinquency) independently.6 For each delinquent behavior, model 1 is considered a baseline model and includes each of the pure network effects (i.e., density, reciprocity, indegree popularity, transitive triplets, and three cycles) and all of the covariate similarity, same covariate, and behavioral effect from covariate effects. Because selection and influence based on violent or delinquent behavior and gender are of primary importance, we include the covariate ego and covariate alter effects for female and delinquency to ensure our gender and delinquency selection estimates are not biased by an uneven tendency for boys or girls, or delinquents or nondelinquents, to nominate (ego effects) or be nominated (alter effects). We do not include ego and alter effects for other covariates to keep the complicated model as simple as possible.

Of particular interest, model 1 includes the similar delinquency (selection) estimate, which evaluates the presence of delinquency-based selection (i.e., overall, do adolescents select friends who have similar delinquency profiles to their own?). Model 1 also includes the average similarity (influence) estimate that evaluates the presence of peer influence on the delinquent behavior in question (i.e., overall, do adolescents' change their behavior to more closely match friends' delinquency?).7 Additionally, all covariates mentioned previously are included in exogenous covariate effects (effect from) to account for changes in the behavior that can be attributed to exogenous influences from these covariates. This model also is used to evaluate hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2.

Model 2, our gender moderator model, is our primary focus because it includes two important interaction terms to determine whether selection and influence operate differently among girls compared with boys. Delinquent behavior average similarity (influence) is interacted with female gender of the adolescent to determine whether females are differentially susceptible to influence from nominated peers compared with males (evaluate hypothesis 3), and similar delinquency (selection effect) is interacted with female gender to determine whether girls are more or less likely to select friends based on friends' behavior than boys (evaluate hypothesis 4). The main parameters of interest, which include influence, selection, and gender interactions with influence and selection, are highlighted in italics in tables 2 and 3 (as will be shown).

Table 2. Stochastic Actor-Based Models of Adolescent Involvement in Violence (N = 1,857).

| Parameter | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | (SE) | b | (SE) | |

| Network Rate Adjustment | ||||

| Early nominators | .576*** | (.143) | .562*** | (.138) |

| Network Structural Effects | ||||

| Outdegree (density) | –4.419*** | (.082) | –4.476*** | (.084) |

| Reciprocity | 2.514*** | (.062) | 2.517*** | (.069) |

| Transitive triplets | .868*** | (.035) | .871*** | (.037) |

| Three cycles | –.685*** | (.062) | –.686*** | (.065) |

| Indegree popularity | .012† | (.007) | .012† | (.007) |

| Exogenous Covariate Effects | ||||

| Similar age | 1.666*** | (.159) | 1.658*** | (.153) |

| Alter female | –.082* | (.036) | –.084* | (.039) |

| Ego female | .060 | (.038) | –.146† | (.085) |

| Same gender | .228*** | (.034) | .204*** | (.035) |

| Same race | .579*** | (.055) | .576*** | (.054) |

| Same public assistance | –.028 | (.055) | –.027 | (.060) |

| Same single parent household | .041 | (.037) | .044 | (.038) |

| Similar verbal ability | .814*** | (.199) | .823*** | (.203) |

| Similar impulsivity | .173 | (.153) | .187 | (.152) |

| Similar depression | .086 | (.141) | .065 | (.140) |

| Similar SES | .463*** | (.089) | .467*** | (.083) |

| School Dummies | ||||

| Outdegree × large school | –1.629*** | (.118) | –1.660*** | (.120) |

| Transitive triplets × large school | .207*** | (.043) | .205*** | (.043) |

| Same race × large school | 1.371*** | (.119) | 1.388*** | (.123) |

| Behavior-Related Network Effects | ||||

| Similar violence (selection) | .929** | (.303) | 1.344** | (.461) |

| Similar violence (selection) × ego female | 2.184* | (.918) | ||

| Alter violence | .014 | (.035) | .061 | (.049) |

| Ego violence | .089* | (.036) | .069 | (.048) |

| Ego violence × ego female | .030 | (.100) | ||

| Alter violence × ego female | .091 | (.105) | ||

| Effects on Violent Delinquency | ||||

| Average similarity (influence) | 1.738 | (1.300) | 2.675* | (1.178) |

| Average similarity (influence) × ego female | 4.141 | (2.652) | ||

| Linear shape | –1.064*** | (.069) | –1.028*** | (.060) |

| Quadratic shape | .088*** | (.019) | .082*** | (.016) |

| Effect from age | –.048 | (.040) | –.055 | (.042) |

| Effect from female | –.443*** | (.081) | –.257† | (.134) |

| Effect from public assistance | .165 | (.111) | .166 | (.116) |

| Effect from single parent household | .026 | (.079) | .018 | (.076) |

| Effect from verbal ability | –.002 | (.003) | –.002 | (.003) |

| Effect from impulsivity | .052 | (.059) | .049 | (.058) |

| Effect from depression | .081 | (.062) | .081 | (.065) |

| Effect from SES | –.089* | (.039) | –.088* | (.041) |

|

|

|

|

||

Abbreviations: SE = standard error; SES = socioeconomic status.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (two-tailed).

Table 3. Stochastic Actor-Based Models of Adolescent Involvement in Nonviolent Delinquency (N = 1,857).

| Parameter | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | (SE) | b | (SE) | |

| Network Rate Adjustment | ||||

| Early nominators | .573*** | (.171) | .561*** | (.155) |

| Network Structural Effects | ||||

| Outdegree (density) | –4.466*** | (.091) | –4.474*** | (.089) |

| Reciprocity | 2.524*** | (.064) | 2.526*** | (.065) |

| Transitive triplets | .871*** | (.034) | .870*** | (.034) |

| Three cycles | –.690*** | (.060) | –.687*** | (.061) |

| Indegree popularity | .014* | (.007) | .014* | (.007) |

| Exogenous Covariate Effects | ||||

| Similar age | 1.673*** | (.158) | 1.668*** | (.164) |

| Alter female | –.061† | (.036) | –.061† | (.035) |

| Ego female | .053 | (.040) | –.051 | (.059) |

| Same gender | .238*** | (.035) | .236*** | (.037) |

| Same race | .579*** | (.054) | .575*** | (.053) |

| Same public assistance | –.019 | (.054) | –.020 | (.057) |

| Same single parent household | .048 | (.036) | .046 | (.035) |

| Similar verbal ability | .809*** | (.197) | .800*** | (.214) |

| Similar impulsivity | .153 | (.146) | .162 | (.154) |

| Similar depression | .069 | (.141) | .048 | (.143) |

| Similar SES | .458*** | (.087) | .458*** | (.084) |

| School Dummies | ||||

| Outdegree × large school | –1.624*** | (.115) | –1.633*** | (.119) |

| Transitive triplets × large school | .203*** | (.043) | .201*** | (.046) |

| Same race × large school | 1.380*** | (.111) | 1.389*** | (.118) |

| Behavior-Related Network Effects | ||||

| Similar nonviolent delinquency (selection) | .980*** | (.295) | 1.069*** | (.255) |

| Similar nonviolent delinquency (selection) × ego female | 1.110* | (.526) | ||

| Alter nonviolent delinquency | .053 | (.034) | .067† | (.036) |

| Ego nonviolent delinquency | .028 | (.036) | .023 | (.033) |

| Ego nonviolent delinquency × ego female | .026 | (.069) | ||

| Alter nonviolent delinquency × ego female | .087 | (.071) | ||

| Effects on Nonviolent Delinquency | ||||

| Average similarity (influence) | 1.413 | (1.155) | 1.420 | (1.182) |

| Average similarity (influence) × ego female | 3.797† | (2.254) | ||

| Linear shape | –1.087*** | (.069) | –1.101*** | (.069) |

| Quadratic shape | –.027 | (.043) | –.043 | (.039) |

| Effect from age | –.182** | (.059) | –.184** | (.061) |

| Effect from female | –.220* | (.101) | –.059 | (.122) |

| Effect from public assistance | .245 | (.154) | .256 | (164) |

| Effect from single parent household | –.002 | (.110) | .003 | (.107) |

| Effect from verbal ability | –.009* | (.004) | –.009* | (.004) |

| Effect from impulsivity | .092 | (.085) | .096 | (.083) |

| Effect from depression | .091 | (.090) | .103 | (.086) |

| Effect from SES | .099† | (.058) | .104† | (.059) |

Abbreviations: SE = standard error; SES = socioeconomic status.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (two-tailed).

An additional important note about the interaction between female gender and similar delinquency (the selection effect) is that it is effectively a three-way interaction. Similarity effects by their nature depend on the level of the behavior (or covariate) of both ego (sending the tie) and alter (receiving the tie). Indeed, an alternative specification for testing a homophilous selection hypothesis is to include an interaction between the covariate-based ego effect and the covariate-based alter effect. To then interact it with gender (the female ego effect) constitutes a three-way interaction. Thus, along with the addition of the gender interaction for selection in model 2, we include the appropriate two-way interactions to support it. These include the main similarity estimate itself (not interacted with gender), an ego female × ego delinquent behavior interaction, and an ego female × alter delinquent behavior interaction. Of the latter two interactions, the former allows for the moderation of the effect of delinquency on tie creation or maintenance by the gender of the nominator. The latter allows for the moderation of the effect of delinquency on nomination popularity of alters by the gender of the nominator.

Meta-Analysis Strategy

We have described an SAOM of a single network. The current study involves the analysis of two large school networks and is concerned with producing an aggregate estimate of model parameters (also see Haas and Schaefer, 2014). In the current study, we model each school network and behavior evolution process using the multigroup analysis available in SIENA. Because there is reason to suspect that certain parameter estimates may differ between the two large schools, we use this approach's capability to capture this variability. For instance, because the two schools differ in size, it is likely that the effect of transitive closure also will differ. As Goodreau, Kitts, and Morris (2009) found, the effect of transitive closure increases (with a diminishing positive slope) as network size increases. Thus, we would expect to observe a somewhat larger transitivity coefficient in the larger school.

The two schools also vary in racial composition; one is predominately White (“Jefferson”), and the other school exhibits much more racial diversity (“Sunshine”). This difference in racial composition may mean that the estimate for the same race effect differs between schools. Because of these expected differences, we conducted a test for heterogeneity of effects across schools. We tested all parameters in a constrained model for heterogeneity across schools (see Ripley, Snijders, and Preciado, 2013: 84). As expected, the tests revealed that the transitivity and same race estimates were those parameters that differed most strongly across the schools. The multigroup analysis offers a natural way to estimate variation in parameter estimates across schools via school dummy interactions. We include school dummy interactions with the transitivity, same race, and density estimates (a density school dummy is automatically included when other school dummies are included) in our models. The multigroup analysis method also allows the network and behavior change rate parameters to vary across schools.

Centered Covariates and Calculating Male and Female Estimates

The default behavior of the SIENA software is to center all individual-level covariates, including binary covariates such as female, by subtracting out their mean. This approach mildly complicates the calculation of gender-specific parameter estimates. Because female is centered, interpretation of an interaction involving gender is not as simple as saying the interaction estimate is the female effect difference (assuming female is coded as 1), whereas the main effect is the male effect. Rather, the centered gender codes must be accounted for in this calculation. Fortunately, the interaction terms for the selection and influence estimates and their standard errors allow us to test directly the hypotheses of gender differences on the selection and influence effects.8

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for male and female adolescents in our sample. This table shows many of the typical gender differences reported in prior research (e.g., girls score higher on verbal ability and depression than boys). Of more importance to our study are gender differences in network characteristics. At both waves, girls are more likely to reciprocate friendship nominations than boys (wave I: 49 percent vs. 43 percent; wave II: 56 percent vs. 43 percent; all values are rounded from table 1), reflecting their greater intimacy with friends. There is much less evidence of gender differences in the size of friendships groups with girls and boys, on average, sending (outdegree) and receiving (indegree) similar numbers of nominations from peers. Finally, examining average levels of involvement in both violence and delinquency indicates that girls report much lower levels of involvement than boys at both waves of data collection. This difference is larger when we consider violence compared with delinquency (delinquency wave I: .9 vs. 1.2; wave II: .5 vs. .7; violence wave I: .6 vs. 1.3; wave II: .3 vs. .8; all values are rounded from table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Two Large “Saturated” Schools in AddHealth Disaggregated by Gender.

| Variable | Female | Male | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/ Proportion | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Mean/ Proportion | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Dependent Variables | ||||||||

| Violence (wave I) | .620 | 1.074 | .000 | 6.000 | 1.298 | 1.519 | .000 | 6.000 |

| Violence (wave II) | .335 | .768 | .000 | 5.000 | .847 | 1.260 | .000 | 5.000 |

| Nonviolent delinquency (wave I) | .900 | 1.128 | .000 | 5.000 | 1.186 | 1.317 | .000 | 5.000 |

| Nonviolent delinquency (wave II) | .492 | .777 | .000 | 4.000 | .689 | .957 | .000 | 4.000 |

| Control Variables | ||||||||

| Age | 16.625 | .852 | 14.029 | 19.953 | 16.9 | .874 | 14.661 | 19.669 |

| Verbal ability | 95.917 | 13.8 | 41.000 | 131.000 | 98.3 | 14.218 | 20.000 | 130.000 |

| Impulsivity | –.024 | .571 | –1.411 | 2.582 | .033 | .592 | –1.411 | 2.937 |

| Depression | .140 | .601 | –.853 | 3.102 | –.052 | .484 | –.853 | 2.885 |

| SES | –.056 | .864 | –1.422 | 1.971 | –.010 | .864 | –1.422 | 1.894 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | .372 | .000 | 1.000 | .396 | .000 | 1.000 | ||

| Black | .159 | .000 | 1.000 | .148 | .000 | 1.000 | ||

| Latino | .239 | .000 | 1.000 | .221 | .000 | 1.000 | ||

| Other | .215 | .000 | 1.000 | .224 | .000 | 1.000 | ||

| Public assistance | .086 | .000 | 1.000 | .062 | .000 | 1.000 | ||

| Single-parent household | .281 | .000 | 1.000 | .275 | .000 | 1.000 | ||

| Friendship Network Variables | ||||||||

| Reciprocity (wave I) | .489 | .426 | ||||||

| Reciprocity (wave II) | .564 | .433 | ||||||

| Outdegree (wave I) | 1.812 | 1.463 | .000 | 5.000 | 1.745 | 1.495 | .000 | 5.000 |

| Outdegree (wave II) | 1.280 | 1.314 | .000 | 5.000 | 1.155 | 1.387 | .000 | 5.000 |

| Indegree (wave I) | 1.815 | 1.688 | .000 | 9.000 | 1.745 | 1.837 | .000 | 10.000 |

| Indegree (wave II) | 1.280 | 1.439 | .000 | 9.000 | 1.155 | 1.541 | .000 | 10.000 |

| Sample Size wave I | 882 | 975 | ||||||

| Sample Size wave II | 785 | 834 | ||||||

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation; SES = socioeconomic status.

Parameter estimates (coefficients) for the SIENA model fits are presented in tables 2 and 3.9 We first present models for violence (table 2) and then those for nonviolent delinquency (table 3). Because we are primarily interested in the estimates capturing gender variation in selection and influence, we refrain from discussing coefficients for the estimates of covariates (i.e., control variables) on network formation; however, all coefficient estimates are presented in the tables.

Violence

The results for violence are displayed in table 2. We first focus on the coefficients of interest in model 1: the influence and selection coefficients. These results indicate that the average similarity (influence) coefficient is positive but not statistically significant (b = 1.738, n.s.), providing little evidence that adolescents' violent behavior (combining influence estimates for boys and girls) changes toward the mean of their friends' violent behavior (failing to support hypothesis 1). The positive and significant coefficient for similar violence (selection), however, indicates that adolescents are more likely to extend ties to others who have similar levels of violence (b = .929, p < .01), providing support for hypothesis 2. Before we consider gender differences in the influence and selection coefficients, these results indicate that although adolescents choose their friends based on friends' involvement in violence, they do not seem to be influenced toward changing their violence as a result of associating with more or less violent friends. These results may change when we partition the influence and selection estimates by gender (model 2).

Briefly examining other estimates included in model 1, results show a negative and significant coefficient for linear shape (b = –1.064, p < .001) and a positive and significant quadratic shape effect (b = .088, p < .01). Taken together with the overall mean of violence being less than 1, these estimates suggest that violent behavior tends to be low on average. The negative and significant coefficient for effect from female (b = –.443, p < .001) indicates that girls tend to exhibit lower levels of violence than boys. The reciprocity (b = 2.514, p < .001) and transitivity (b = .868, p < .001) coefficients are positive and significant, indicating that adolescents have a tendency to reciprocate friendships and to form transitive relationships with others in the school. The coefficient for three cycles is negative and significant (b = –.685, p < .001), indicating that adolescents avoid closing triads cyclically. The coefficient for indegree popularity is positive and marginally significant (b = .012, p < .10), suggesting a possible feedback effect of received nominations—the more nominations an adolescent has, the more he or she receives from others. The direction of coefficients described previously is consistent with prior longitudinal network studies on adolescent social networks (e.g., Schaefer et al., 2011). Model 1 also shows a negative and significant coefficient for alter female (b = –.082, p < .01), indicating that adolescents are less likely to extend ties to or maintain ties with girls than boys, likely reflecting girls' more intimate friendship networks. The positive and significant coefficient for same gender (b = .228, p < .001) provides evidence that adolescents are more likely to select friends who are of the same gender. In addition, we find evidence of friendship selection depending on similarity of race, verbal ability, and family SES.

Turning to model 2, our gender moderator model, the results reveal that the average similarity (influence) × ego female coefficient is positive but not significant (b = 4.141, n.s.), providing little evidence that boys and girls differ in susceptibility to influence of friends' violence; however, as noted next, additional calculations are necessary to clarify these results. Moving to selection coefficients, the results show that the similar violence (selection) × ego female coefficient is positive and statistically significant (b = 2.184, p < .05), indicating that girls show a stronger tendency than boys to select friends based on similarity in their violence.

As noted, centering the female variable at its mean somewhat complicates the interpretation of the selection and influence parameters. To determine gender-specific estimates of influence and selection, we must combine the main effect estimates and the interaction effect estimates scaled by the appropriate gender variable code. The male influence estimate can be estimated using the sum of the influence estimate and the interaction estimate multiplied by the male gender code (2.675 + (–.475 × 4.141) = .708). Because the variance–covariance matrix is available from our SIENA results, we also can calculate a standard error for the gender-specific estimates (1.037).10 Although these calculations offer consistent evidence that the male influence estimate is not significant (b = .708, standard error [SE] = 1.037, p = .495), the same is not true for girls. The influence estimate for girls is calculated similarly (2.675 + (.525 × 4.141)) and is significantly different from zero (b = 4.849, SE = 2.329, p = .037). Although there is no evidence that boys are significantly influenced by friends' violence, for girls, influence dynamics are apparent and operate to shape their involvement in violence.11 Similar calculations are done for violence selection estimates. Again, although the male selection estimate is not statistically significantly different from zero (b = .307, SE = .367, n.s.), the female estimate is significantly different from zero (b = 2.491, SE = .861, p < .01), providing evidence that girls do consider the violent behavior of potential friends. Overall, these results present a consistent, although mildly complicated, story, with little evidence that boys choose friends based on similarity in violence compared with girls who do consider behavioral similarity when selecting friends. Likewise, we find no evidence that boys' violence is influenced by their friends' behavior, whereas the evidence indicates that girls do change their violent behavior to become more similar to their friends.

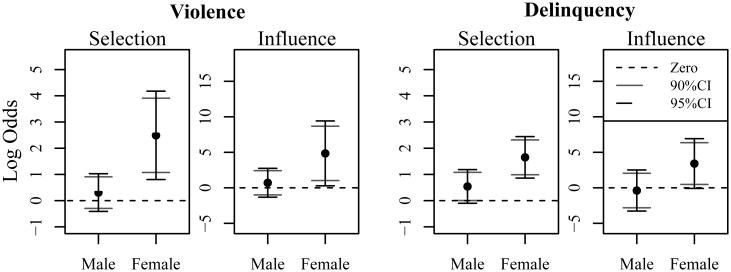

We present the male and female estimates for selection and influence in figure 1 (focusing on the left two panes). The y-axis represents the parameter estimate scale in log-odds, whereas the x-axis denotes the gender represented by the estimate. Each plot shows a separate estimate for boys and girls along with an indication of the 90 percent and 95 percent confidence intervals around the estimate. These results display evidence for our conclusion that girls but not boys experience selection and influence dynamics playing a role in shaping their involvement in violence.

Figure 1.

Male and Female Specific Selection and Influence Parameter Estimate.

Nonviolent Delinquency

The results for models of nonviolent delinquency are presented in table 3. Focusing on the influence estimate in model 1 reveals that the coefficient for average similarity (influence) is positive but not statistically significant (b = 1.413, n.s.), indicating that on average, youth in our sample do not show a tendency to change their nonviolent delinquency to be similar to that of their friends (again failing to support hypothesis 1). The similar nonviolent delinquency (selection) coefficient is positive and significant (b = .980, p < .001), indicating that adolescents are more likely to nominate peers as friends when they exhibit similar levels of nonviolent delinquency than they are to nominate adolescents who display different levels of delinquency (also, again supporting hypothesis 2). These results are similar to those presented in model 1 for violence.

Model 2 (gender moderator model) introduces the interaction effects between gender and the main effects of interest. The results indicate that the average similarity (influence) × ego female coefficient is positive and marginally significant (b = 3.797, p < .10), providing some evidence that girls have a higher propensity to change their delinquency toward the mean of their friends than do boys (support for hypothesis 3). In terms of selection, the similar nonviolent delinquency (selection) × ego female coefficient also is positive and statistically significant (b = 1.110, p < .05), indicating that girls are more likely than boys to select friends based on their delinquency levels (supporting hypothesis 4).

Based on the coefficients presented in model 2, we again calculate gender-specific selection and influence estimates for nonviolent delinquency. The male nonviolent delinquency influence estimate (1.420 + (–.475 × 3.797)) is negative and not significant (b = –.384, SE = 1.476, n.s.), whereas the female influence estimate (1.420 + (.525 × 3.797)) is positive and marginally significant (b = 3.413, SE = 1.789, p < .10). The male delinquency selection estimate (1.069 + (–.475 × 1.110)) is positive and marginally significant (b = .542, SE = .327, p < .10), whereas the female selection estimate (1.069 + (.525 × 1.110)) is positive and significantly different from zero (b = 1.65, SE = .404, p < .001). These results are displayed in the right panels of figure 1. This figure illustrates our finding that girls but not boys are influenced by friends' nonviolent delinquency. In addition, this figure shows that although boys have some propensity to select friends based on their delinquency profile, girls are even more likely to do so.

In sum, the results for delinquency provide no evidence for male susceptibility to influence and some evidence that boys nominate friends based on similarity in their delinquency. In contrast, evidence suggests that girls are influenced toward the average delinquent behavior of their friends (one-tailed test of significance) and have an even greater preference than boys to select friends based on delinquency similarity. These findings for delinquency, although not as strong, are largely consistent with results for violence.

Supplementary Analyses

Although these results support our hypotheses regarding girls' greater susceptibility to influence and their experience of stronger selection dynamics playing a role in peer-delinquency homophily compared with boys, our finding of little or no evidence of boys being influenced by friends' behavior is inconsistent with prior research. One possibility is that combining influence from both less and more delinquent friends averages away the influence estimate (also Haas and Schaefer, 2014). Considering that influence dynamics may depend on whether friends were relatively prosocial or antisocial, we extend our model to allow the influence estimate to differ depending on whether the influence was in the direction of delinquency or prosocial behavior. This approach allows influence to operate in two ways: 1) influence to become more delinquent (after associating with relatively delinquent friends) and 2) influence to become less delinquent (after associating with relatively nondelinquent friends). In the SAOM framework, this consists of adding an endowment effect for peer influence in addition to the traditional evaluation (“constrained”) version of the influence effect that normally would model influence in both directions to occur with equal force. The inclusion of the endowment effect creates a new model parameter that captures the difference between the constrained influence estimate and influence purely in the downward direction. Notably, in the presence of the endowment version of the effect, the evaluation version captures influence either to maintain behavior or to increase it to align more closely with friends' greater violence or delinquency.12

We include an endowment effect for a total of two model effects: the average similarity effect capturing peer influence and the average similarity × ego female effect capturing the gender difference in peer influence. To gain a deeper understanding of adolescent preferences for upward versus downward peer influence, the school-level average similarity of the behavior must be incorporated so that preference values can be calculated for specific scenarios of adolescent and peer behavior (Haas and Schaefer, 2014). These additional models are in contrast to our earlier models (model 2 in tables 2 and 3) that did not contain the endowment effects and, therefore, constrained peer influence in both directions to be equal (captured in a single-model coefficient).

In the endowment model examined in this study, a positive downward influence estimate for boys would suggest that boys in a relatively nondelinquent peer group reduce their delinquent behavior to become more similar to the average of their peers.13 A zero estimate would suggest boys are indifferent to downward movements to become more like their peers. Finally, a negative estimate would imply that boys are resistant to changing their behavior to be similar to their friends when that change is toward lowered delinquency.

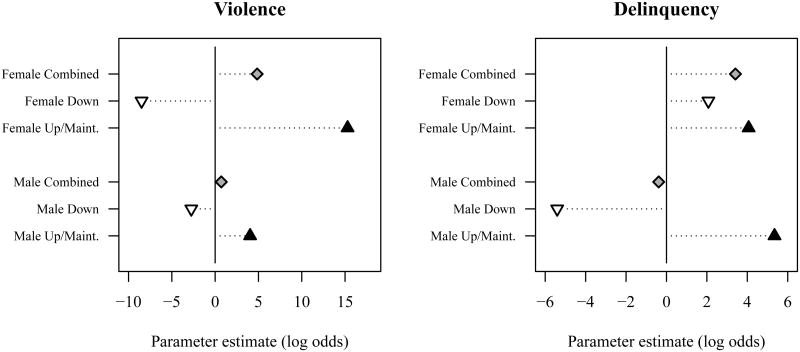

Focusing first on results for violence, we find that although the more complicated unconstrained model converged well on the data, the peer influence estimates were largely nonsignificant, likely because of the added complexity of incorporating additional parameters to an already complex model with limited power. Nevertheless, the estimates from this model are enlightening regarding the unexpected findings showing little or no evidence for influence dynamics shaping boys' behavior, as presented earlier in tables 2 and 3. A table showing the unconstrained model results is available in appendix A. We represent the gender-specific estimates in figure 2, which shows the male and female estimates (calculated by summing the appropriate parameter estimates scaled by the gender codes [male = –.475, female = .525]) for upward or maintenance (black upward arrow) and downward (white downward arrow) movement estimated in the endowment model. For the sake of comparison, the figure also shows, with a gray diamond, the constrained peer influence estimates calculated from the constrained model estimates appearing in tables 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Male and Female Influence Estimates Varying by Direction of Influence.

As illustrated in figure 2, the gray diamond representing results from the constrained model presented in table 2 falls much closer to the center of the upward and downward influence estimates. Because the constrained influence estimates must capture upward and downward movements in the same parameter, it will be an average of the influence estimates in the upward and downward directions (i.e., assumes influence in the upward and downward directions is equivalent). The unconstrained model, however, allows a more interesting but complicated story to emerge. Here, we find a pattern suggestive of girls experiencing a stronger positive effect of upward influence toward maintaining or increasing their violence in response to exposure to violent friends and a negative effect of downward influence suggesting resistance to changing their violent behavior when associating with nonviolent peers (as indicated by the negative estimate portrayed in “female down” in figure 2). Although combining these two influence patterns resulted in an overall positive estimate for girls' influence in the constrained model presented in table 2, the influence estimate was just marginally significant for girls in model 2, as a result of averaging both the upward and downward estimates. The same seems to be true, but on a smaller scale, for boys. Boys also seem to be influenced toward maintaining or increasing violence when associating with violent friends and resistant to influence toward reducing violence when associating with nonviolent friends. These results help to explain the nonsignificant peer influence effect for boys presented in table 2 (i.e., the upward and downward estimates canceled each other out when an average peer influence effect was estimated).