Abstract

Objective

I examine Twitter discussion regarding the Texas omnibus abortion restriction bill before, during, and after Wendy Davis’ filibuster in summer 2013. This critical moment precipitated wide public discussion of abortion. Digital records allow me to characterize the spatial distribution of participants in Texas and the United States and estimate the proportion of participants who were Texans.

Study design

Building a dataset based on all hashtags associated with the bill between June 19th and July 14th, 2013, I use GPS locations and text descriptions of locations, to classify users by county of residence. Mapping tweets from accounts within the continental US by day, I describe the residential composition of the conversation in total and over time. Using indirect estimation, I compute an estimate of the number of Texans who participated.

Results

About 1.66 million tweets were sent using hashtags associated with the bill from 399,081 user accounts. I estimate counties of residence for 160,954 participants (40.3%). An estimated 115,500 participants (29%) were Texans and Texans sent an estimated 48.8% of all tweets. Tweets were sent from users estimated to live in every region of Texas, including 189 of Texas’ 254 counties. Texans tweeted more than non-Texans on every day except the filibuster and the day after.

Conclusion

The analysis measures real-life responses to proposed abortion restrictions from people across Texas and the US. It demonstrates that Twitter users from across Texas counties opposed HB2 by describing the geographical range of US and Texan abortion rights supporters on Twitter.

Implications

The Twitter discussion surrounding Wendy Davis’ filibuster revealed a geographically diverse population of individuals who strongly oppose abortion restrictions. Texans from across the state were among those who actively voiced opposition. Identifying rights supporters through online behavior may present a new way of classifying individuals’ orientations regarding abortion rights.

Keywords: Abortion opinion, social media, reproductive health, variability

1. Introduction

On June 25, 2013, Wendy Davis stood on the floor of the Texas Senate for 11 hours to filibuster HB2, an omnibus abortion bill that promised to dramatically decrease the number of clinics providing abortion care in Texas, ban abortions after 20 weeks “post fertilization,” require all physicians providing abortion care to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the facility where they worked, and impose restrictions on the provision of medication abortion. As she spoke, the Texas Capitol filled with thousands of supporters and opponents of abortion rights while 180,000 watched via livestream. Supporters of abortion rights had been rallying in the days before Davis’ filibuster and they returned day after day to oppose the bill. A hashtag, #StandWithWendy, arose on Twitter as supporters online expressed their outrage with the bill and their support for Davis.

Tweets about the bill and the filibuster represent real-world responses to the proposed restrictions. Johnson-Hanks and coauthors [1] propose a theory of action situating individuals’ behaviors within conjunctures, or short-term sets of conditions under which action occurs. Wendy Davis’ filibuster and the prospect of HB2's passage presented Twitter users in Texas with a conjuncture. How they responded to that conjuncture reveals the orientation and degree of their reaction to the prospect of their very large state being left with only six or seven abortion clinics. Texans living in or near Austin had the option of marching on the Capitol to express their opposition to the bill, but those living far away were likely less able to express themselves this way. While tweeting is not equivalent to marching in the streets, it is something more than privately holding an opinion, and thus measuring tweets from the conjuncture during which HB2 was being debated measures an avenue of action available to all Texans who used Twitter. Taking this interpretation, tweets in support of abortion rights provide data for describing a population of particularly impassioned abortion rights supporters without relying on responses to survey questions. This approach obviates design effects because it measures responses to real-world events rather than hypothetical vignettes, but the fact that Twitter users are substantially different from the general population means that generalization beyond the description of the discussion is impossible [2-5]. Thus, this analysis describes the spatial range of the Twitter conversation around HB2 and Davis’ filibuster, not the distribution of abortion opinions in general in Texas.

The theory and method for analyzing social media data are in their infancy, so I therefore ask simple, basic questions about how many people participated, where they lived, and which side they supported. Whether Texans were among the Twitter users who supported abortion rights in the conversation can help us interpret the outpouring on Twitter as either local resistance or outside resistance to the proposed law. Estimating where users lived within Texas could combat a perception that the protests at the Capitol reflected Austin's liberal population, not a broad base of Texans from across the state. While election results indicate that Democrats live throughout Texas, not all Democrats support abortion rights. Thus, I use the Twitter data to investigate whether or not a geographically diverse population of Texans participated in the digital resistance to HB2. If Texans from across the state participated in the discussion and expressed their outrage with the bill, the long-term prospects of abortion access in the state may be more malleable than if the resistance was concentrated in Austin and outside the state.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data Sources

I formulated an initial list of hashtags – which are used on Twitter to build conversations and identify positions – by reviewing Twitter activity during HB2's proposal, debate, and passage. I validated the list through interviews with key informants (journalists, bloggers, and social media managers) and checked it against the Twitter feeds of organizations and politicians on both sides. Hashtags used at least five times in reference to the filibuster and HB2 on a given side were included. The final list included the following: neutral bill name hashtags (#sb1 #hb2, #hb60, and #sb5 ), hashtags used by supporters of abortion rights (#StandWithWendy, #prochoice, #StandWithTXWomen, #SWTW, and #feministarmy), and hashtags used by opponents of abortion rights (#SitDownWendy and #prolife).

Based on this list of hashtags, I purchased a comprehensive dataset of tweets with any of the hashtags from June 19 through July 14, 2013 from TweetReach. The dataset includes both tweets and retweets. The dates covered include all major events involved in the bill's passage through the Texas legislature. June 19 was the day before the bill's first large public hearing and July 13 was the day the bill finally passed. Wendy Davis’ filibuster was June 25. The tweet data include tweet text, user name, tweet day and time, and other technical information.

2.2. Measures and Analysis

The tweets themselves do not have locations. In order to build the dataset needed to estimate a location for each user account, I used the Twitter Application Programming Interface (Twitter REST API v1.1) to collect data on user accounts. The Twitter API is a feature of the Twitter website that allows direct access to some Twitter data from a computer. For each account whose tweets had GPS data, I collected 100 tweets from the Twitter REST API v1.1. For all accounts, I collected location data from user profiles in the form of text strings. The text strings sometimes included latitude and longitude coordinates. Using geocoded text strings in addition to a sample of GPS encoded tweets, this method generates location estimates for about four times as many Twitter user accounts as typical analyses that rely solely on GPS data [6, 7].

I estimated counties of residence in up to two ways, first using GPS encoded tweets and second by geocoding text strings from the user profiles. For user accounts with GPS coded tweets, I determined the county of each of the 100 tweets by joining the tweet's GPS coordinates with a shapefile of the US. I estimated the user's residence as the most frequent county of tweet origin, as long as more than 50 tweets originated in it. When GPS locations were outside the United States, I coded them as outside Texas for the purposes of this analysis. I performed these processes with Python and the geopy package.

For all user accounts with non-missing text location data, I geocoded text strings at the county level using the Google Maps API v3, which uses gazetteer as well as map data to code location names like “The Big Apple” as well as names of cities, counties, and states. Location data from user profiles were predominately user-generated text strings like “Austin, TX”. Some users reported their location whimsically, such as “between a rock and a hard place” or “Milky Way.” Some valid locations were outside the United States and thus had no county and some valid locations were identifiably inside the US but had insufficient precision to determine a county. I coded these with a binary indicator for outside or inside Texas.

When user accounts had only one residential location estimate based on GPS data or based on text string data, I assigned that location as their residence. When estimates from both sources were available I used the GPS estimate. The two estimates were identical in 79% of accounts with both estimates.

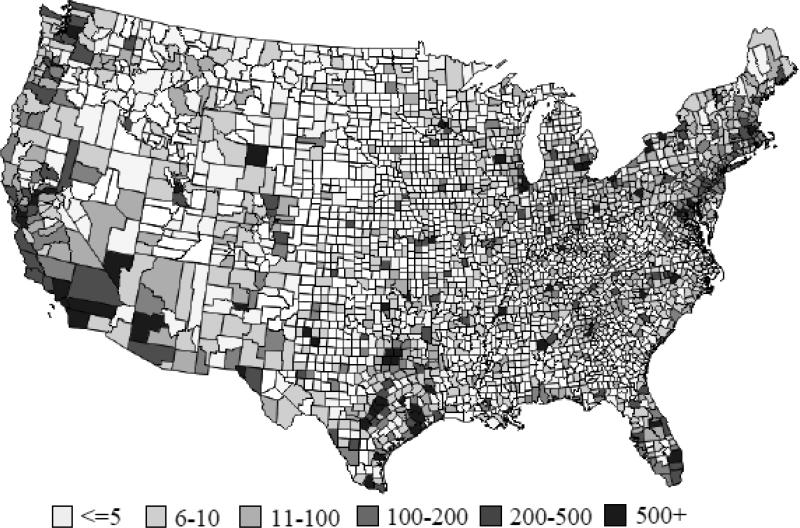

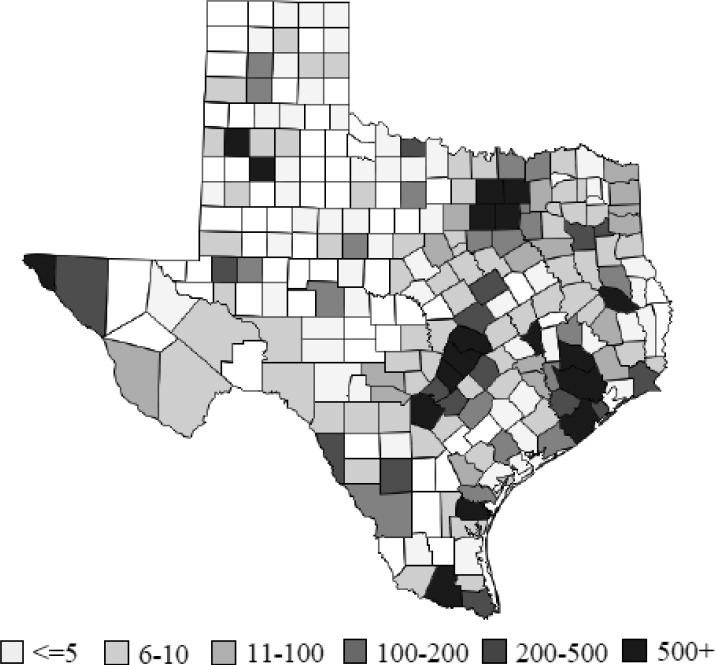

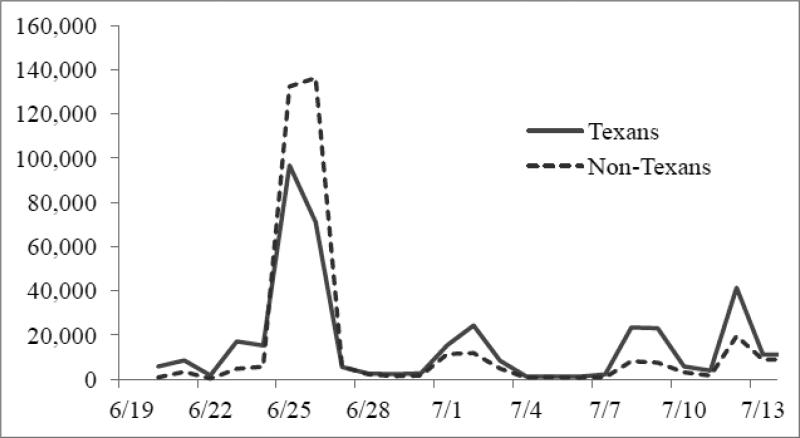

I generate a map displaying the volume of tweets over the entire period from users estimated to live in each county in the continental US, and a map of the same data for Texas alone. Maps were generated using SAS® 9.3. Focusing on Texas, I also generate a line chart of the number of active user accounts (one or more tweet) with estimated residence in Texas by day and active user accounts with estimated residence outside of Texas by day.

In order to estimate the total number of Texans who participated in the conversation, I applied the proportion of Texans among all user accounts with valid locations (including locations outside the US) to all user accounts to indirectly estimate the total number of Texans who participated. This calculation relies on the assumption that the proportion of user accounts with missing location data who resided in Texas was the same as to the proportion of user accounts with non-missing location data who resided in Texas.

I estimated orientation toward abortion rights at the level of the tweet and the user account. I classified tweets with two binary indicators, one indicating the presence of any hashtags associated with support for abortion rights and one indicating the presence of any hashtags associated with opposition to abortion rights. In order to evaluate this classification strategy I coded three random samples of 100 tweets. One sample contained tweets with supportive hashtags. The second contained tweets with opposing hashtags, and the third contained tweets with exclusively neutral hashtags. I coded all tweets in each sample for support, opposition, or neutrality with respect to abortion rights. Among the tweets with hashtags supportive of abortion rights, 99 of 100 were identifiably supportive of rights, while 1 was uninterpretable as supportive or opposed. Similarly, among the sample of 100 tweets with hashtags opposed to abortion rights, 100 were hand coded as opposed. In the sample of 100 tweets with only neutral hashtags, 87 were supportive of abortion rights, 7 were neutral, 3 were opposed, and 3 were uninterpretable. I classified the user accounts with an indicator of the presence of hashtags of each type in the full collection of their tweets in the dataset. Some tweets included emoticons, which could have corrupted the text encoding of special characters and may have led to errors in classification.

All data from the Twitter API were collected using Python and the package Twython. The historical tweets may be purchased without special approval and the Twitter API is public. This study was determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas at Austin.

3. Results

Table 1 describes the numbers of user accounts and tweets by estimated location and source of location estimate. Hashtag-based selection identified 1,656,252 tweets from 399,081 unique user accounts. Using residential location estimates based on text and GPS together, county of residence was directly estimated for 160,954 user accounts, or 40.3% of all accounts. Locations were estimated using GPS data for 11.7% of accounts and using geocoded text data for 36.1% of accounts. For 7.5% of accounts both estimates were available. Of user accounts with directly estimated residence, 29.0% were estimated to live in Texas. Multiplying this proportion by the total number of user accounts, an indirect estimate of the total number of Texans who participated is about 115,500 people. On average, each Texan who participated tweeted more times than each non-Texan and thus Texans are estimated to have sent 808,500 tweets, or 48.8% of the total tweets.

Table 1.

Users and Tweets by Location

| Users | Tweets | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 399,081 | 100.0% | 1,656,252 | 100.0% |

| Location estimates by source | ||||

| With any location estimate | 160,954 | 40.3% | 768,140 | 46.4% |

| With only text location estimate | 113,938 | 28.6% | 587,232 | 35.5% |

| With only GPS location estimate | 16,893 | 4.2% | 44,798 | 2.7% |

| With text and GPS location estimate | 30,123 | 7.5% | 136,110 | 8.2% |

| Missing location estimate | 238,127 | 59.7% | 888,112 | 53.6°% |

| Directly estimated locations | ||||

| In Texas | 46,614 | 29.0% | 374,993 | 48.8°% |

| Outside Texas | 114,340 | 71.0% | 393,147 | 51.2% |

| Indirect estimate: Total in Texas | 115,500 | ~29% | 808,500 | ~48.8% |

Figure 1 displays the number of tweets from user accounts estimated to reside in each county in the continental US for the 40.3% of user accounts had directly estimated residence. It illustrates the fact that Twitter users across the United States participated in the conversation. Concentrations of tweets in metropolitan areas throughout Texas, the West coast, the Mid-Atlantic, the Midwest, and the coastal North East are displayed.

Figure 1.

Tweets by county of user's of residence, continental US.

Figure 2 displays a map of Texas colored by the number of tweets sent from users estimated to live in each county. It illustrates the fact that the majority of Texas counties contained at least one participant in the discussion of the bill. Of Texas’ 254 counties, participants were directly estimated to live in 192. All of Texas’ counties classified as Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) were estimated to have had users who tweeted.

Figure 2.

Tweets by county of user's residence, Texas.

Figure 3 plots the number of tweets by day for Twitter user accounts directly estimated to be Texans and Twitter user accounts directly estimated to reside outside of Texas. Texans outnumber non-Texans, except on the day of the filibuster and the day after. Peaks in the plot correspond with legislative events, hearings, and votes. Texans’ tweets peaked on the day of the filibuster while tweets from non-Texans peaked the next day.

Figure 3.

Tweets by residence and day.

Based on the high level of agreement between hashtag-based classification and hand coding, I accepted hashtag-based classification as a proxy for tweet and user orientation. The majority of tweets and users appear to be supportive of abortion rights. Specifically, only 2.7% of tweets contained a hashtag associated with opposition to abortion rights, while 42.4% of tweets contained a hashtag supportive of abortion rights. Only 0.45% of tweets contained hashtags of both types. Among user accounts, 58.4% tweeted at least once with a hashtag supportive of abortion rights, while only 3.6% ever tweeted with a hashtag in opposition to abortion rights. About half of those who ever tweeted with a hashtag in opposition also tweeted with a hashtag in support (1.56%).

4. Discussion

The photographs and reports from the June 2013 protests at the Texas Capitol document thousands of Texans’ opposition to HB2, but little has been reported about the volume and composition of the individuals contributing to the digital outpouring that accompanied these protests. The present analyses demonstrate that at least 1.66 million tweets were sent using hashtags associated with the discussion, and that the tweets were largely in support of abortion rights. Further work will more precisely classify the tweets and users by support for or opposition to abortion rights, but the finding that only 2.7% of tweets contained hashtags opposed to abortion rights bolsters the interpretation that most of the discussion surrounding the bill was supportive of abortion rights. The volume of tweets is large considering that the hashtag #YesAllWomen, used by people worldwide to discuss misogyny, also yielded 1.6 million tweets in its peak four days of use [8].

By estimating user residences, I find that a large fraction (48.8%) of the tweets were from Texans themselves. Furthermore, users who tweeted came from all over Texas. Had the outrage on Twitter not included a geographically diverse contingent of Texans, the protests last summer could have been an artifact of Texas’ Capitol being in one of its most liberal cities. Instead, the findings here point to the existence of a broad network of Texans who strongly oppose restrictions on abortion access. The presence of relatively ardent (at least impassioned enough to speak out on Twitter) rights supporters throughout Texas rebuts the narrative of Texas’ monolithically conservative culture. In that narrative, the true Texans are deeply conservative. While Texas still generally votes Republican in statewide elections, the present analysis demonstrates that Texans throughout the state – including in rural areas – oppose abortion restrictions.

The finding that such a small fraction of all tweets supported abortion restrictions should not be interpreted as evidence of a high prevalence of abortion rights supporters in the general population, but instead as evidence that social media users who used hashtags to discuss HB2 and the filibuster were supportive of abortion rights. This is consistent with Twitter users being younger, better educated, and more urban than the general population of internet users [5]. The differences between the Twitter users described here and the general public probably arise jointly from the selection process that leads people to become Twitter users and the fact that individuals who react strongly to restrictions on abortion rights may differ substantially from the general population. While this analysis does not measure political opinion generally, the power of social media to facilitate mass demonstration together with the support for abortion rights among Twitter users could be welcome news to advocates of abortion rights. Furthermore, the breadth of engagement in the conversation outside of Texas indicates that social media users across the US and beyond may have a role to play in conversations about local abortion restrictions, an increasingly common phenomenon in the states[9].

If abortion opinions are indeed polarizing over time, as many researchers have argued [10-12], identifying and understanding the extremes of support for and opposition to abortion rights may assist social scientists in predicting the future of abortion politics and could guide advocates’ efforts to shape that future. The power of understanding the extremes is underscored by evidence that engagement in social movements about abortion may diffuse extreme ideology rather than result from it [13, 14]. If this is the case, at the individual level even marginal engagement may predict more fervent views in the future. Analogously, at the aggregate level the most extreme views of the present may become more widespread as polarization increases. Thus the population of abortion rights supporters in Texas who responded to the conjuncture of HB2's proposal and Wendy Davis’ filibuster with public outrage may influence the future of abortion politics in Texas as a “left flank” of strong supporters of abortion rights. These individuals could participate in the diffusion of support for abortion rights in Texas. Their energy and passion could be harnessed to further discussion, change opinions, and mobilize voters.

This study is limited by the fact that it must estimate locations and by factors associated with the data sources. Twitter users may tweet from non-home counties (for example from work) and they may misrepresent or not update residence in their profiles. However, if rural users travel to urban areas for work, such travel would bias away from finding users in rural areas, making my finding of geographic diversity conservative. Moreover, this study's method of estimating locations is an improvement over relying solely on GPS data, since social media users who enable and use GPS coding of their activities have been found to be unrepresentative of the total population of social media users [6, 15]. Thus, while the estimates here are not perfect, they may be less biased than previous work using solely GPS data. Limitations also arise from the data and methods. First, because Twitter users are not representative of the general population, this study solely seeks to describe the locations of Twitter users who tweeted with the hashtags and cannot be used to describe abortion opinions in the general population. Additionally, selecting tweets on hashtags means that the many tweets without hashtags and user accounts that tweeted about HB2 and the filibuster without ever using a hashtag are omitted from this analysis[16]. This bias leads to conservative estimates of the number of participants and tweets. It may also mean that my sample includes more experienced Twitter users, which may contribute to the observation that few tweets or user accounts are opposed to abortion rights. Hashtag-based classification also does not clearly classify the very small number of user accounts and tweets with hashtags of both types. This analysis treats organizations and individuals in the same way, and it may overestimate the number of individuals participating if individuals used more than one Twitter account. A final limitation is that error in classification of tweets by support for abortion rights may arise from undetected irony, retweeting for purposes other than support, or the strategic use of hashtags to insert oneself into the other side's conversation. Hand coding was used to estimate that this error leads to the misclassification of less than 5% of all tweets. Unfortunately, special symbols may have obscured a small proportion of hashtags, which also may have contributed to errors in classification.

This analysis only scratches the surface of what is possible to learn from these data. Further work should investigate the correlates of persistent engagement in political action among these users, the network diffusion of engagement, and spatial variation in the ratio of supporters to opponents of abortion rights. These efforts will require collaborations across reproductive justice, sociology, computer science, and communications. The findings of such work could inform advocacy and help predict the future direction of reproductive healthcare access in the states.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Jonathan Rosenberg for expert programming assistance and Joseph Potter, Kristine Hopkins, Celia Hubert, David McClendon, and three anonymous reviewers for insights and feedback on previous versions. This work was supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant for Infrastructure for Population Research at the University of Texas at Austin, Grant 5 R24 HD042849, NICHD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Johnson-Hanks JA, et al. Understanding Family Change and Variation. Toward a Theory of Conjuctural Action. In: Stillwell J, editor. Understanding Population Trends and Processes. Vol. 5. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bumpass LL. The Measurement of Public Opinion on Abortion: The Effects of Survey Design. Family Planning Perspectives. 1997;29(4):177–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tourangeau R, Rasinski KA. Cognitive processes underlying context effects in attitude measurement. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(3):299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zigerell LJ, Rice HM. In: Intense Ambivalence, in Improving Public Opinion Surveys: Interdisciplinary Innovation and the American National Election Studies. John KMM, Aldrich H, editors. Princeton University Press; 2011. p. 402. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner J, Smith A. 72% of Online Adults are Social Networking Site Users. Pew Research Center; Washington, D.C.: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hecht B, Stephens M. ICWSM 2014. AAAI Press; Menlo Park, CA: 2014. A Tale of Cities: Urban Biases in Volunteered Geographic Information. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takhteyev Y, Gruzd A, Wellman B. Geography of Twitter networks. Social Networks. 2012;34(1):73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofherr J. [June 18, 2014];#Yesallwomen Takes Twitter by Storm: A Rundown of the Numbers. 2014 Available from: http://www.boston.com/news/nation/2014/05/27/yesallwomen-takes-twitter-storm-rundown-the-numbers/dtjOWwQvol6upAwOY2hAUK/story.html.

- 9.Nash EG, R. B., Rowan A, Rathburn G, Vierboom Y. Laws Affecting Reproductive Health and Rights: 2013 State Policy Review. The Guttmacher Institute; NY:NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolzendahl CI, Myers DJ. Feminist Attitudes and Support for Gender Equality: Opinion Change in Women and Men, 1974-1998. Social Forces. 2004;83(2):759–789. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hout M. Abortion politics in the United States, 1972–1994: From single issue to ideology. Gender Issues. 1999;17(2):3–34. doi: 10.1007/s12147-999-0013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouw T, Sobel Michael E. Culture Wars and Opinion Polarization: The Case of Abortion. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106(4):913–943. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munson ZW. The making of pro-life activists: How social movement mobilization works2009: University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yardi S, Boyd D. Dynamic Debates: An Analysis of Group Polarization Over Time on Twitter. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 2010;30(5):316–327. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leetaru K, et al. Mapping the global Twitter heartbeat: The geography of Twitter. First Monday. 2013;18(5) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu YK-S, C, Mislove A. The Tweets They Are a-Changin’: Evolution of Twitter Users and Behavior.. Proceedings of the Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media; Ann Arbor, MI.. 2014. [Google Scholar]