Abstract

Histone proteins are key components of chromatin. Their N-terminal tails are enriched in combinatorial post-translational modifications (PTMs), which influence gene regulation, DNA repair and chromosome condensation. Mass spectrometry (MS)-based middle-down proteomics has emerged as technique to analyze co-occurring PTMs, as it allows for the characterization of intact histone tails (>50 aa) rather than short (<20 aa) peptides analyzed by bottom-up. However, a demonstration of its reliability is still lacking. We compared results obtained with the middle-down and the bottom-up strategy in calculating PTM relative abundance and stoichiometry. Since bottom-up was proven to have biases in peptide signal detection such as uneven ionization efficiency, we performed an external correction using a synthetic peptide library with known peptide relative abundance. Corrected bottom-up data were used as reference. Calculated abundances of single PTMs showed similar deviations from the reference when comparing middle-down and uncorrected bottom-up results. Moreover, we show that the two strategies provided similar performance in defining accurate PTM stoichiometry. Collectively, we evidenced that the middle-down strategy is at least equally reliable to bottom-up in quantifying histone PTMs.

Keywords: bottom-up proteomics, histones, mass spectrometry, middle-down proteomics, stoichiometry

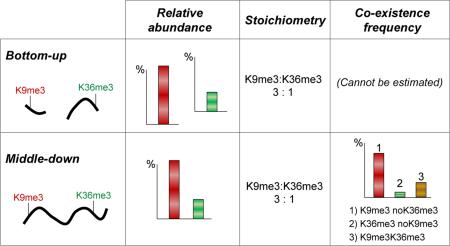

Graphical Abstract

Histone proteins are fundamental components of nuclear chromatin in eukaryotic organisms. Histones are assembled in octamers named nucleosomes, which are wrapped by DNA every ~200 base pairs. Histone N-terminal tails are exposed outside the nucleosome, and they are heavily modified by dynamic post-translational modifications (PTMs). The deposition of such PTMs modulates chromatin structure, which directly affects crucial cellular events such as gene expression, DNA repair, mitosis and meiosis1,2. Histone PTMs are also among the major drivers of epigenetic memory, as they can be inherited after cell division3. Aberrations in PTM relative abundance have been found in several diseases4,5, which highlights the direct link between histone marks and cell phenotype. However, such PTMs often act in a synergistic manner, and gene transcription is triggered by multiple modifications rather than single marks6. This calls for development of techniques that can accurately define not only single PTM relative abundance, but also their stoichiometry and possibly their co-existence frequency, which allows for the investigation of PTM interdependency7.

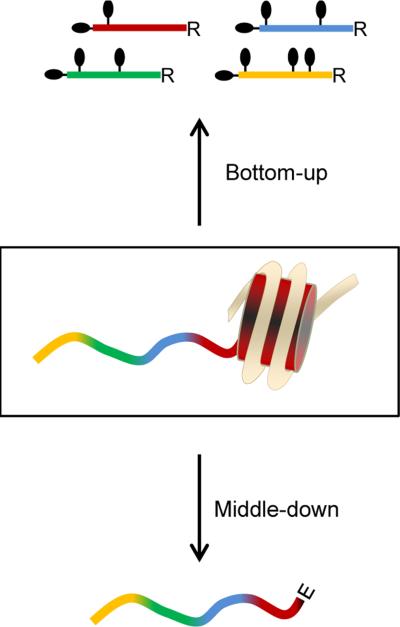

Currently, the most widely adopted technology to analyze histone PTMs in a large scale manner is mass spectrometry (MS)8,9. The most popular workflow for the quantification of single PTMs, namely bottom-up proteomics (Fig. 1), includes histone digestion into short peptides (<20 aa), followed by liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis (Fig. S1). However, the MS signal of a histone peptide can be dramatically different depending on its modification state or amino acid composition10. This is mostly due to the ionization efficiency of a given peptide, but also the poor LC retention of short (<6 aa) and hydrophilic peptides plays a role in losing sensitivity. This bottom-up method is thus reliable to compare between samples, as all LC-MS runs are subjected to the same limitations, but it is limited for comparing relative abundance between PTMs. Lin et al. successfully proposed to utilize a library of synthetic modified histone peptides to correct the biases in ionization efficiency10.

Figure 1. the two proteomics strategies.

Schematic representation of the bottom-up and middle-down type peptides after digestion. Bottom-up type peptides are heavily derivatized on both N-terminal and lysine side chains by propionylation.

Middle-down proteomics has recently emerged as high throughput strategy to define PTM co-existence frequency11,12. In this workflow histones are usually cleaved by GluC, generating polypeptides corresponding to the entire histone N-terminal tail (Fig. 1). Separation is commonly performed using weak cation exchange – hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (WCX-HILIC), as such resin exploits the high hydrophilicity and basicity of histone tails. As middle-down leads to a highly complex population of isobaric peptides, each precursor mass corresponds to several different combinatorial PTM codes which cannot be separated by LC (Fig. S2). Thus, quantification is performed at the MS/MS level, preferably by using electron transfer dissociation (ETD)13, extracting the total ion intensity of spectra that were assigned to a given species12. However, the currently published workflows11,12 are described in terms of robustness and automation, but they still lack an estimation of the reliability of such quantification method.

In this work, we compared the performance of the two proteomics workflows in defining histone PTM abundance and stoichiometry using histone H3 purified from HeLa cells. As a reference we used the bottom-up analysis after performing an external correction of the peptide ionization efficiency using a library of 93 synthetic peptides, as previously described10. Briefly, the synthetic peptide library was prepared to obtain a mixture where all peptides were present in equal molarity, and the observed MS signal was used to estimate the deviation from the theoretical one (equal signal for all peptides). The obtained value was used to correct the signals of the histone H3 peptides detected in the bottom-up analysis. The bottom-up sample preparation and analysis was performed according to Lin et al.10, including histone derivatization with propionic anhydride and trypsin digestion. In parallel, the middle-down workflow was performed according to Sidoli et al.12. Both bottom-up and middle-down samples were analyzed using the same mass spectrometer (Orbitrap Fusion, Thermo Scientific).

Reversed-phase liquid chromatography (LC) was adopted to separate the bottom-up sized peptides (Fig. S1). The elution profile showed peaks of at least 40 sec (~10 sec at full width at half maximum, FWHM). Considering the MS duty cycle of about 2 sec, every peptide elution profile was accurately defined by around 20 data points. The number of peptides quantified from four replicates was 44 (Table S1). Middle-down sized polypeptides were separated using WCX-HILIC, which generated highly heterogeneous and wide peak widths (from 2 to 7 min), calculated by performing extracted ion chromatogram of peptide precursor masses (Fig. S2). Quantification was performed using isoScale slim12 (http://middle-down.github.io/Software), which uses the total ion intensity of identified MS/MS spectra to retrieve peptide abundance in a fragment ion relative ratio approach14. The number of total MS/MS spectra used for quantification was 1388, 1134, 1433 and 1565 for replicates 1-4, respectively. This corresponded to 287 non redundant combinatorial PTMs (Table S2). Calculation of a single histone PTM relative abundance was performed by summing the relative abundance of all peptides carrying the given PTM. The same PTM was found on no more than four different peptides in the bottom up study, but could be found on a large number of peptides in the middle-down study. For instance, the modification H3K9me2 was quantified using the two peptides aa 9-17 Kme2STGGKAPR and Kme2STGGKacAPR in bottom-up, while it was present in 91 combinatorial marks in the middle-down study (Table S1 and S2).

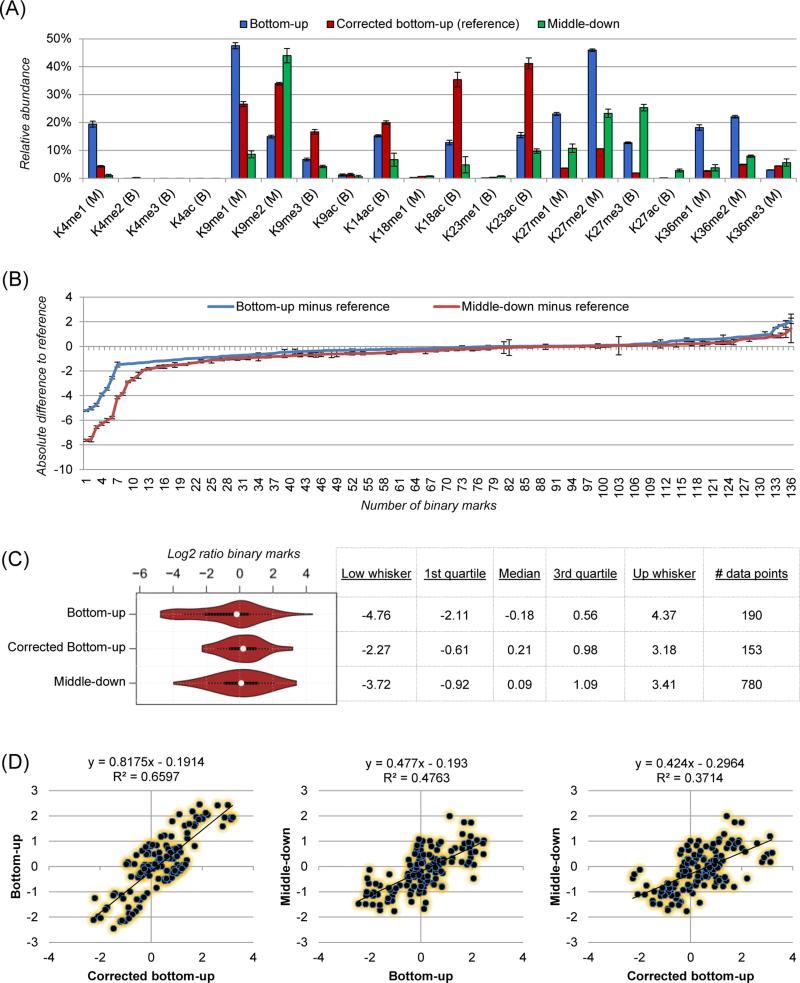

The relative abundance measurements calculated in the bottom-up analysis were then corrected by using the synthetic peptide library as an external standard, as previously described10. We used this correction as reference, and we compared such dataset with the bottom-up and the middle-down results. Not all PTMs could be compared among all datasets. For instance, only middle-down allows for quantification of arginine methylation, as in the bottom-up analysis unmodified arginines, but not modified, are targets of trypsin for digestion. On the other hand, bottom-up is overall more sensitive, and we could quantify all H3K4 methylation states, not possible with middle-down (Table S1 and S2). In the end, we could compare 20 histone H3 PTMs (Fig. 2A). Such comparison revealed that 9 out of 20 marks had a smaller difference in relative abundance values between reference and middle-down datasets, while 11 out of 20 were closer to the bottom-up dataset. However, the overall difference from the reference, calculated by summing all the individual differences for each PTM, was lower for middle-down (172.1%) than bottom-up (218.9%). This indicated that bottom-up provides remarkable errors for few relevant PTMs, e.g. K9me1, K27me2. The bottom-up analysis showed higher precision (18.5% average CV) as compared to the middle-down (42.1% average CV). Surprisingly, the histone marks K18ac and K23ac quantified in the reference analysis presented more than 2-fold change discrepancy to both bottom-up and middle-down results (Fig. 2A); since these PTMs are carried by the same peptide (aa 18-26) this suggests that the signal of the synthetic peptide used for the external correction might be underestimated. Overall, the middle-down strategy proved to have highly comparable accuracy to bottom-up in quantifying single histone marks.

Figure 2. single marks and stoichiometry analysis.

(A) Relative abundance of single marks calculated using the bottom-up (blue), the reference (red) and the middle-down datasets (green). Error bars represent standard deviation of four technical replicates. In parenthesis the condition with the smaller difference from the reference (B: bottom-up, M: middle-down). (B) Difference between bottom-up (blue) or middle-down (red) stoichiometry values with values calculated in the reference dataset. Error bars represent standard deviation of four technical replicates. Values are sorted individually for the two datasets; the x-axis does not represent the same binary mark for both analyses. (C) Distribution of stoichiometry values after Log2 transformation. On the right, relevant data points of the violin plot. (D) Scatter plot between bottom-up and reference (left), bottom-up and middle-down (center) and middle-down and reference (right) datasets. Each dot represents one stoichiometry value after Log2 transformation.

Next, we compared the ability of the two strategies in calculating PTM stoichiometry, which is defined as the exact relative quantity of two PTMs between each other. To do so, we calculated the relative ratio of all PTMs quantified with each workflow. Such calculation could be performed for 190 binary marks in the bottom-up and 780 in the middle-down analysis, of which only 136 where quantified by both strategies. We subtracted the value obtained in either of the two strategies by the reference. Results evidenced that 83.1% and 78.7% of the PTM binary ratios were within 1 absolute difference unit for the bottom-up and the middle-down dataset, respectively (Fig. 2B). This demonstrated that both methods provided highly similar performance in calculating PTM stoichiometry. Bottom-up was once again more precise than middle-down, as they provided an average CV of 50.0% and 94.4%, respectively. Afterwards, stoichiometry values were Log2 transformed (e.g. Log2(K4me1/K9me2), Log2(K14ac/K36me3)...) to remodel the dataset into a Gaussian distribution. The distribution of the reference dataset was more similar to the middle-down than bottom-up, with the un-corrected bottom-up values being spread over a wider Log2 range (Fig. 2C). This indicated that the bottom-up stoichiometry analysis tends to provide erroneous outliers, as such wide distribution was not present after external correction (reference) neither in the middle-down analysis. This can be explained as different peptides and different modified forms having different ionization efficiencies, and thus they are detected with different sensitivity. For instance, the relative abundance of the peptide carrying H3K4me3 (bottom-up estimated abundance 0.0009%) is highly underestimated, as it is poorly retained by LC and intrinsically less efficiently ionized. The calculated stoichiometry with an abundant PTM generates a value of several orders of magnitude, which explains the wide distribution of the stoichiometry values with the bottom-up analysis (Fig. 2C). Such problem is not present in the middle-down analysis, as all PTMs are carried by the same peptide sequence.

Finally, we performed a direct comparison of the 136 binary Log2 stoichiometry values that could be estimated in all three datasets (Fig. 2D). Results highlighted a higher correlation between bottom-up and reference (R2: 0.66) as compared to the other two comparisons. This demonstrated that, despite the small differences between middle-down and reference (Fig. 2B), the bottom-up dataset still had a more correlated trend to the external correction we used as reference. Moreover, we could observe a slope remarkably low than 1 in the correlation between middle-down and bottom-up (0.477) as well as middle-down and reference (0.424). This indicated once again that the dynamic range of the middle-down analysis in calculating PTM stoichiometry was lower than the bottom-up, as previously discussed. This overall higher correlation between bottom-up and reference datasets was not surprising, as this last one was itself a bottom-up type analysis, which presents inevitable biases that are different from the ones that might be present in a middle-down analysis. For instance, bottom-up is intrinsically biased to (i) solubilization efficiency, which might vary between peptides obtained after digestion; (ii) digestion itself, as the enzyme might not cleave a modified form rather than an unmodified one; (iii) derivatization with propionic anhydride, which can be obstructed by steric hindrance in a given peptide isoform. A more accurate investigation of middle-down performance would require the use of a library of modified middle-down sized polypeptides. However, such library has a prohibitive cost for most proteomics laboratories.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that middle-down is a technique that provides histone PTM relative abundance values comparable to the more widely adopted bottom-up strategy. Proving the reliability of the middle-down workflow is highly relevant, as this is currently the only quantitative technique to estimate the co-existence frequency of histone PTM all along the N-terminal tail. Despite middle-down quantification being technically more challenging than bottom-up, and despite that we also adopted a bottom-up type analysis as reference, we could still demonstrate that middle-down provides an overall PTM quantification as accurate as bottom-up. This can be explained as the middle-down workflow analyzes large molecules which intrinsically have fewer changes in ionization efficiency once modified. Moreover, a given PTM in a middle-down analysis is present on a large number of combinatorial peptides all over the LC profile (Fig. S2 and Table S2). The presence of such PTM in several peptide isoforms normalizes the biases between modified and unmodified forms, both required to estimate its relative abundance, resulting in a more accurate PTM quantification.

Experimental procedure

Histone purification from cells

HeLa S3 cells were grown in suspension as previously described15 and harvested using a standard protocol16. Histone purification was performed as previously described16. Briefly, nuclei were isolated by suspending cells into nuclei isolation buffer (15 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 15 mM NaCl, 60 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 250 mM sucrose, 0.2% NP-40) including the following inhibitors: 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM AEBSF and 10 mM sodium butyrate. Nuclei were separated by centrifugation (1000 g for 10 min) and 2 mL of cold 0.4 N H2SO4 was added on the nuclei pellet. Nuclei were incubated at 4 °C with shaking for 2 h. The nuclei were pelleted at 3400 g for 5 min, and proteins were precipitated from the supernatant with 25% TCA (w/v) as previously described16.

Histone H3 isolation and digestion

Purified total histones were resuspended in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and loaded onto a 4.6 mm i.d. Vydac C18 column (218TP) using an off-line Beckman Coulter (System Gold) HPLC (Buffer A: 0.1% TFA, Buffer B: 95% acetonitrile, 0.08% TFA) at 0.8 mL/min as previously described11. HPLC-UV separation was performed using a gradient from 0 to 60% buffer B in 60 min, followed by from 60 to 100% buffer B in 10 min. Purified histone H3 was resuspended in 30 μL of 50 mM NH4HCO3, pH 8.0, and divided in two equal volumes, one for bottom-up and one for middle-down digestion. Bottom-up derivatization and digestion were performed as previously described16. Trypsin was used at an enzyme:sample ratio of 1:20, overnight at room temperature. Middle-down was prepared as follows: GluC was added to the sample at an enzyme:sample ratio of 1:20 (overnight digestion at room temperature). Reaction was blocked by adding 1% formic acid for LC-MS analysis.

Synthetic peptide library preparation

93 synthetic peptides representing the most studied histone ArgC-like digested peptides were synthesized by Cell Signaling Technology (CST)® Protein Aqua™. In this library isobaric peptides were labeled with different isotopes to allow discrimination at the precursor mass level. Single peptide concentration was measured by amino acid analysis, and all peptides were mixed in equal molarity (0.27 pmol/μL). Derivatization was performed by using the standard propionylation protocol16.

Bottom-up nanoLC-MS/MS and data analysis

Samples were analyzed by using a nanoLC-MS/MS setup. nanoLC was configured with a 75 μm ID x 17 cm Reprosil-Pur C18-AQ (3 μm; Dr. Maisch GmbH, Germany) nano-column using an EASY-nLC nanoHPLC (Thermo Scientific, Odense, Denmark). The HPLC gradient was 0-35% solvent B (A = 0.1% formic acid; B = 95% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) over 40 min and from 34% to 100% solvent B in 7 minutes at a flow-rate of 250 nL/min. LC was coupled with an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). Spray voltage was set at 2.3 kV and capillary temperature was set at 275 °C. Full scan MS spectrum (m/z 300−1200) was performed in the Orbitrap with a resolution of 60,000 (at 200 m/z) with an AGC target of 5x10e5. By using the Top Speed MS/MS option set to 2 sec the most intense ions above a threshold of 2000 counts were selected for fragmentation. Fragmentation was performed with higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) with normalized collision energy of 29, an AGC target of 1x10e4 and a maximum injection time of 200 msec. MS/MS data were collected in centroid mode in the ion trap mass analyzer (normal scan rate). Only charge states 2-4 were included. The dynamic exclusion was set at 30 sec. Peak area was extracted from raw files by using our in-house software EpiProfile (manuscript submitted). The relative abundance of a given PTM was calculated by dividing its intensity by the sum of all modified and unmodified peptides sharing the same sequence.

Middle-down nanoLC-MS/MS and data analysis

Samples were separated using an Eksigent 2D+ nanoUHPLC (Eksigent, part of ABSciex). The nanoLC was equipped with a two column setup, a 2 cm pre-column (100 μm ID) packed with C18 bulk material (ReproSil, Pur C18AQ 3 μm; Dr. Maisch) and a 12 cm analytical column (75 μm ID) packed with Polycat A resin (PolyLC, Columbia, MD, 1.9 μm particles, 1000 Å). Loading buffer was 0.1% formic acid (Merck Millipore) in water. Buffer A and B were prepared according to Young et al.11. The gradient was delivered as follows: 5 min 100% buffer A, followed by a not linear gradient from 55 to 85% buffer B in 120 min and 85-100% in 10 min. Flowrate for the analysis was set to 250 nL/min. MS acquisition was performed in an Orbitrap Fusion (Thermo) with the same source settings as the bottom-up study. Data acquisition was performed in the Orbitrap for both precursor and product ions, with a mass resolution of 60,000 for MS and 30,000 for MS/MS. MS acquisition window was set at 660-720 m/z. Dynamic exclusion was disabled. Precursor charges accepted for MS/MS fragmentation were 6-10. Isolation width was set at 2 m/z. The 8 most intense ions with MS signal higher than 5,000 counts were isolated for fragmentation using ETD with an activation time of 20 msec. 3 microscans were used for each MS/MS spectrum, and the AGC target was set to 2x10e5. Data processing was performed as previously described12. Briefly, spectra were deconvoluted with Xtract (Thermo) and searched with Mascot (v2.5, Matrix Science, London, UK), including mono- and dimethylation (KR), trimethylation (K) and acetylation (K) as dynamic modifications. Mascot result files were processed with isoScale slim12 (http://middle-down.github.io/Software) using a tolerance of 30 ppm. All raw files were uploaded in the Chorus database (https://chorusproject.org/, project ID: 724).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from an NIH Innovator grant (Grant DP2OD007447) from the Office of the Director and NIH Grant R01GM110174.

References

- 1.Xu D, Bai J, Duan Q, Costa M, Dai W. Cell cycle. 2009;8:3688–3694. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.22.9908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Cell Res. 2011;21:381–395. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alabert C, Groth A. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:153–167. doi: 10.1038/nrm3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portela A, Esteller M. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi P, Allis CD, Wang GG. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2010;10:457–469. doi: 10.1038/nrc2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger SL. Nature. 2007;447:407–412. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwammle V, Aspalter CM, Sidoli S, Jensen ON. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2014;13:1855–1865. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O113.036335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young NL, Dimaggio PA, Garcia BA. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2010;67:3983–4000. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0475-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sidoli S, Cheng L, Jensen ON. Journal of proteomics. 2012;75:3419–3433. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin S, Wein S, Gonzales-Cope M, Otte GL, Yuan ZF, Afjehi-Sadat L, Maile T, Berger SL, Rush J, Lill JR, Arnott D, Garcia BA. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2014;13:2450–2466. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O113.036459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young NL, DiMaggio PA, Plazas-Mayorca MD, Baliban RC, Floudas CA, Garcia BA. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2009;8:2266–2284. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900238-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidoli S, Schwammle V, Ruminowicz C, Hansen TA, Wu X, Helin K, Jensen ON. Proteomics. 2014;14:2200–2211. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikesh LM, Ueberheide B, Chi A, Coon JJ, Syka JE, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2006;1764:1811–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pesavento JJ, Mizzen CA, Kelleher NL. Analytical chemistry. 2006;78:4271–4280. doi: 10.1021/ac0600050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas CE, Kelleher NL, Mizzen CA. Journal of proteome research. 2006;5:240–247. doi: 10.1021/pr050266a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin S, Garcia BA. Methods in enzymology. 2012;512:3–28. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391940-3.00001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.