Abstract

There are currently no data to support the suggestion that the dose of therapeutic immunoglobulin (Ig) should be capped in obese patients for pharmacokinetic (PK), safety and economic reasons. We compared IgG trough levels, increment and efficiency in matched pairs of obese and lean patients receiving either replacement or immunomodulatory immunoglobulin therapy. Thirty-one obese patients were matched with a clinically equivalent lean patient across a range of indications, including primary antibody deficiency or autoimmune peripheral neuropathy. Comprehensive matching was carried out using ongoing research databases at two centres in which the dose of Ig was based on clinical outcome, whether infection prevention or documented clinical neurological stability. The IgG trough or steady state levels, IgG increments and Ig efficiencies at times of clinical stability were compared between the obese and lean cohorts and within the matched pairs. This study shows that, at a population level, obese patients achieved a higher trough and increment (but not efficiency) for a given weight-adjusted dose compared with the lean patients. However at an individual patient level there were significant exceptions to this correlation, and upon sub-group analysis no significant difference was found between obese and lean patients receiving replacement therapy. Across all dose regimens a high body mass index (BMI) cannot be used to predict reliably the patients in whom dose restriction is clinically appropriate.

Keywords: autoimmune peripheral neuropathies, dosing, immunomodulation, lean versus obese patients, replacement, therapeutic immunoglobulin

Introduction

Therapeutic immunoglobulin (Ig) is a high-cost drug; the core Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) recommends dosing based upon actual body weight (ABW) 1. However, obese patients are frequently excluded (directly or indirectly) from clinical trials for licensing medicinal products, and therefore the resulting SPC dosage recommendations may not reflect the increasingly obese nature of western populations 2,3. Although clinicians have considered for at least 20 years that ABW dosing may not be optimal for obese patients 4,5, sufficient evidence to make a robust recommendation on the dosing of Ig in obese patients is currently lacking.

Although there is no empirical evidence, there are theoretical pharmacokinetic and physiological factors that suggest that ABW may be inappropriate for obese patients:

IgG is a relatively polar molecule with a small volume of distribution (VD) 6. Therefore, penetration of the active ingredient into adipose tissue/lipophilic environments has been postulated to be poor, although this will be affected by active transport and inflammation 7,8.

Perfusion of adipose tissue relative to lean tissue is also known to be poor 9.

Blood volume relative to ABW is reduced in obese patients compared with lean patients (50 versus 75 ml/kg) 10.

The IgG receptor, FcRn, which is responsible for the long half-life of IgG in vivo, is distributed widely throughout the body. However, there is some evidence that expression in adipose tissue is lower than in other tissues, e.g. skin and muscle 11,12.

The majority of the above factors lead to the hypothesis that infused Ig concentrates in the blood and the extracellular space due to relative exclusion from the lipid compartment. If obese patients achieve a higher plasma IgG concentration for any given dose of Ig compared with lean patients, obese patients would require less Ig to achieve a positive clinical outcome, as the therapeutic action of Ig, whether immunomodulatory or infection prevention, is dependent upon the concentration at the site of action 13,14. Obese patients are recommended to receive a lower dose of Ig by health-care payers to reduce costs and save resources 15,16; however, there is limited evidence for dose reduction in obese patients 17. Three unpublished reports recommend such a reduction: the Western Australia pilot study, in which 30 overweight patients received a reduced dose for replacement and no deterioration was seen; the Hospital Corporation of America advice document, in which Ig doses are based on ideal body weight; and the Ohio State University Medical Centre which routinely uses ideal body weight-adjusted dosing of Ig.

In contrast, there are also two recently published studies: a UK-based retrospective audit involving 107 common variable immunodeficiency disorder (CVID) patients across four centres, which was unable to find any relationship between annual dose and trough level despite normalizing for weight and body mass index (BMI). These authors concluded that individualization rather than fixed weight-based dosing should be used 18 and called for prospective trials. A US study involving 173 primary immunodeficiency (PID) patients showed that there was no difference in bioavailability (determined by IgG trough level) between obese versus lean patients, and concluded that there was no justification for dosing adjustments in obese patients relative to lean patients 19.

Both these studies considered only patients receiving Ig replacement therapy, but a significant portion of Ig is now used in high-dose immunomodulation therapy (in the United Kingdom 43% was used in neurology in 2012) 20, and data are urgently required in both situations.

In addition to expense, there are patient safety and convenience considerations for using the minimum but clinically effective dose in obese patients:

An increase in the incidence of adverse events is associated with larger doses of IVIg 21.

Obese patients are at a higher risk of suffering serious adverse drug reactions independent of dose, due to additional vascular risk factors 22.

Administration of large volumes of IVIg is time-consuming, and therefore inconvenient for the patient and costly to the health system.

To provide data rather than anecdote for both replacement and immunomodulatory Ig therapies, we analysed 31 matched pairs of obese and lean patients to determine if the obese patients required less Ig/kg body weight to achieve a given clinical outcome when compared with the matched lean partner. It was important to consider both replacement and immunomodulation, due to the differing dose regimens and divergent patient characteristics involved.

Methods

The data were retrieved retrospectively from databases in Oxford and London as part of an audit; the patients were informed that the information is documented. Data on 32 patients (16 pairs) who received Ig for PID (replacement therapy) and 30 patients (15 pairs) who had received Ig for autoimmune neurological conditions (immunomodulation) were collected, including: the cumulative dose (g/kg/month) of Ig during a 12-month period, BMI, mean IgG trough level (prior to infusion), infusion interval and residual (pretreatment) serum IgG. Patient details are given in Table1. Patients had been treated and followed for > 5 years in each centre.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all patients included in the study.

| Patient ID | Replacement dose (0) high dose 1 | Lean (0) Obese 1 | Dx | Sex | Age | Residual IgG (g/l) | Dose (g/kg/month) | BMI | Trough IgG (g/l) | Increment | i.v./s.c. | Infusion Frequency (days) | Efficiency Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1·1 | 0 | 1 | CVID | F | 48 | 1 | 0·6 | 37·8 | 10·1 | 9·1 | s.c. | 7 | 8·7 |

| 1·2 | 0 | 0 | CVID | F | 44 | 0·89 | 0·8 | 18·5 | 8·4 | 7·5 | s.c. | 7 | 5·4 |

| 2·1 | 0 | 1 | CVID | M | 69 | 0·5 | 0·7 | 38·1 | 10·2 | 9·7 | i.v. | 14 | 4·0 |

| 2·2 | 0 | 0 | CVID | M | 60 | 1·3 | 0·3 | 26·7 | 11·8 | 10·5 | i.v. | 21 | 6·7 |

| 3·1 | 0 | 1 | IgG Sub | F | 64 | 5 | 0·4 | 30·6 | 10·9 | 5·9 | s.c. | 10 | 5·9 |

| 3·2 | 0 | 0 | IgG Sub | F | 56 | 6·6 | 0·4 | 25·4 | 13·3 | 6·7 | s.c. | 7 | 9·6 |

| 4·1 | 0 | 1 | IgG sub and IgA | F | 35 | 7·4 | 0·7 | 30·4 | 16·5 | 9·1 | s.c. | 7 | 7·4 |

| 4·2 | 0 | 0 | IgG sub and IgA | F | 26 | 4·8 | 0·4 | 23·9 | 10·7 | 5·9 | s.c. | 7 | 8·4 |

| 5·1 | 0 | 1 | CVID | F | 79 | 3·7 | 0·5 | 33·6 | 8·9 | 5·2 | s.c. | 7 | 5·9 |

| 5·2 | 0 | 0 | CVID | F | 61 | 0·32 | 0·6 | 26 | 10·7 | 10·4 | s.c. | 7 | 9·9 |

| 6·1 | 0 | 1 | CVID | M | 65 | 4·1 | 0·5 | 33 | 6·8 | 2·7 | s.c. | 7 | 3·1 |

| 6·2 | 0 | 0 | CVID | F | 59 | 0·25 | 0·4 | 24 | 5·4 | 5·2 | s.c. | 7 | 7·4 |

| 7·1 | 0 | 1 | CVID | M | 47 | 0·35 | 0·8 | 31 | 8·9 | 8·6 | i.v. | 14 | 3·1 |

| 7·2 | 0 | 0 | CVID | F | 35 | 0·8 | 0·9 | 21·5 | 7·3 | 6·5 | i.v. | 14 | 2·1 |

| 8·1 | 0 | 1 | IgG sub | F | 61 | 4·55 | 0·4 | 33·7 | 8·8 | 4·3 | s.c. | 7 | 6·1 |

| 8·2 | 0 | 0 | IgG sub | F | 60 | 8·7 | 0·4 | 18·3 | 9 | 0·3 | s.c. | 10 | 0·3 |

| 9·1 | 0 | 1 | CVID | F | 76 | 4·3 | 0·4 | 32·5 | 6·9 | 2·6 | s.c. | 7 | 3·7 |

| 9·2 | 0 | 0 | CVID | F | 66 | 0·7 | 0·6 | 24·5 | 10·9 | 10·2 | s.c. | 7 | 9·7 |

| 10·1 | 0 | 1 | CVID | F | 35 | 2·65 | 0·4 | 37·7 | 9·1 | 6·5 | i.v. | 21 | 3·1 |

| 10·2 | 0 | 0 | CVID | F | 37 | 0·1 | 0·5 | 28·8 | 13·3 | 13·2 | i.v. | 14 | 7·5 |

| 11·1 | 0 | 1 | XLA | M | 20 | 1 | 0·5 | 34·3 | 12·4 | 11·4 | i.v. | 21 | 4·3 |

| 11·2 | 0 | 0 | XLA | M | 14 | 1·54 | 0·4 | 19·9 | 11·4 | 9·9 | i.v. | 21 | 4·7 |

| 12·1 | 0 | 1 | IgG sub | F | 68 | 3·8 | 0·4 | 37·3 | 8·1 | 4·3 | s.c. | 7 | 6·1 |

| 12·2 | 0 | 0 | IgG sub | F | 24 | 4·9 | 0·6 | 21·9 | 10·5 | 5·6 | s.c. | 7 | 5·3 |

| 13·1 | 0 | 1 | CVID | F | 18 | 0·16 | 0·5 | 36·1 | 10·7 | 10·5 | i.v. | 21 | 4·0 |

| 13·2 | 0 | 0 | CVID | M | 54 | 0·96 | 0·45 | 28·1 | 10·3 | 9·3 | i.v. | 21 | 4·0 |

| 14·1 | 0 | 1 | SPAD | F | 48 | 7·8 | 0·3 | 38·2 | 11·5 | 3·7 | s.c. | 7 | 7·0 |

| 14·2 | 0 | 0 | SPAD | F | 56 | 8·5 | 0·5 | 24·8 | 12·6 | 4·1 | s.c. | 7 | 4·7 |

| 15·1 | 0 | 1 | CVID | F | 72 | 4·6 | 0·8 | 36·8 | 8 | 3·4 | s.c. | 7 | 2·4 |

| 15·2 | 0 | 0 | CVID | F | 74 | 2·8 | 0·5 | 29·6 | 6·9 | 4·1 | s.c. | 7 | 4·7 |

| 16·1 | 0 | 1 | Thymoma | F | 50 | 0·9 | 0·6 | 30 | 7·4 | 6·5 | i.v. | 21 | 2·1 |

| 16·2 | 0 | 0 | Thymoma | F | 59 | 3 | 0·5 | 21·1 | 9·5 | 6·5 | i.v. | 21 | 2·5 |

| 17·1 | 1 | 1 | CIDP | F | 64 | 5·1 | 0·8 | 37 | 15·9 | 10·8 | s.c. | 7 | 7·7 |

| 17·2 | 1 | 0 | CIDP | F | 61 | 9·49 | 0·7 | 28·3 | 16·9 | 7·4 | s.c. | 7 | 6·0 |

| 18·1 | 1 | 1 | CIDP | F | 46 | 10 | 0·9 | 44·7 | 17·1 | 7·1 | i.v. | 14 | 2·3 |

| 18·2 | 1 | 0 | CIDP | F | 52 | 8·4 | 1·2 | 21·5 | 17·3 | 8·9 | i.v. | 14 | 2·1 |

| 19·1 | 1 | 1 | CIDP | M | 66 | 8 | 1·4 | 37·4 | 26·8 | 18·8 | i.v. | 14 | 3·8 |

| 19·2 | 1 | 0 | CIDP | M | 73 | 10·1 | 1·3 | 27·6 | 18·8 | 8·7 | i.v. | 14 | 1·9 |

| 20·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | M | 44 | 11·2 | 0·7 | 36·8 | 16 | 4·8 | s.c. | 7 | 3·9 |

| 20·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | M | 49 | 10·7 | 0·7 | 24·3 | 16·9 | 6·2 | s.c. | 7 | 5·1 |

| 21·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | M | 67 | 13·4 | 1·2 | 34·4 | 25·1 | 11·7 | s.c. | 7 | 5·6 |

| 21·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | M | 68 | 9·4 | 0·8 | 25·1 | 14·3 | 4·9 | s.c. | 7 | 3·5 |

| 22·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | M | 70 | 11·9 | 1·3 | 30·2 | 20·1 | 8·2 | s.c. | 3·5 | 7·2 |

| 22·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | M | 67 | 10·3 | 0·6 | 25·9 | 15·1 | 4·8 | s.c. | 7 | 4·6 |

| 23·1 | 1 | 1 | CIDP | M | 62 | 10·4 | 1 | 44·4 | 16·6 | 6·2 | i.v. | 14 | 1·8 |

| 23·2 | 1 | 0 | CIDP | M | 66 | 9·9 | 2·1 | 24·1 | 30·2 | 20·3 | i.v. | 28 | 1·4 |

| 24·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | M | 38 | 8·99 | 1·6 | 32·9 | 26·8 | 17·8 | s.c. | 7 | 6·4 |

| 24·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | F | 57 | 8·6 | 2 | 24 | 18·6 | 10·0 | s.c. | 7 | 2·9 |

| 25·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | M | 51 | 12·1 | 1 | 30·2 | 15·5 | 3·4 | s.c. | 7 | 1·9 |

| 25·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | M | 59 | 9·8 | 1·6 | 26·7 | 18·8 | 9·0 | s.c. | 3·5 | 6·4 |

| 26·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | F | 56 | 9·2 | 1·1 | 30·9 | 21·7 | 12·5 | s.c. | 3·5 | 13·0 |

| 26·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | F | 39 | 11·6 | 0·7 | 27·8 | 17·9 | 6·3 | s.c. | 7 | 5·1 |

| 27·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | F | 45 | 7·3 | 0·5 | 40·8 | 7·3 | 0·0 | i.v. | 84 | 0·0 |

| 27·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | F | 42 | 10·6 | 1·6 | 17·5 | 13·1 | 2·5 | i.v. | 35 | 0·2 |

| 28·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | M | 58 | 10·6 | 1·3 | 37·2 | 15·9 | 5·3 | i.v. | 28 | 0·6 |

| 28·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | M | 55 | 10·6 | 2·1 | 23·9 | 14·8 | 4·2 | i.v. | 28 | 0·3 |

| 29·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | M | 67 | 10·6 | 1·2 | 30 | 18 | 7·4 | i.v. | 21 | 1·2 |

| 29·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | M | 66 | 10·6 | 1·2 | 25·2 | 14·6 | 4·0 | i.v. | 28 | 0·5 |

| 30·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | F | 72 | 10·6 | 2 | 36·9 | 33·1 | 22·5 | i.v. | 21 | 2·1 |

| 30·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | F | 67 | 10·6 | 1·4 | 19·4 | 12·3 | 1·7 | i.v. | 42 | 0·1 |

| 31·1 | 1 | 1 | MFMN | F | 58 | 10·6 | 1 | 35·9 | 12·4 | 1·8 | i.v. | 42 | 0·2 |

| 31·2 | 1 | 0 | MFMN | F | 62 | 10·6 | 1·3 | 26·6 | 26·8 | 16·2 | i.v. | 42 | 1·2 |

BMI = body mass index; Ig = immunoglobulin; CVID = common variable immunodeficiency; XLA = X-linked agammaglobulinaemia; SPAD = specific antibody deficiency; CIDP = chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; MFMN = Multifocal motor neuropathy; F = female; M = male; i.v. = intravenous; s.c. = subcutaneous.

Only patients whose symptoms, Ig dose and infusion interval were stable during the period studied were included. For replacement patients, a ‘stable’ IgG level was defined as: < 1·5 g/l variation in trough IgG for 12 months and free of bacterial infections. Infection-free is defined as ≤ 2 moderate (i.e. treated only with oral antibiotics) bacterial infections per year 13. For autoimmune neurological patients receiving immunomodulation therapy, ‘stable’ was defined as persistent remission of neurological symptoms using a series of validated scores, appropriate and tailored to their disease and disability. This included MRC score (70 points), sensory sum score, 10 m walk, overall neuropathy disability score, Rasch-built overall disability scale (R-ODS) and, in some cases, formal hand dynamometry. BMI varied within patients over time by < 3·5 kg/m2.

The lean patients acting as immunomodulation controls were matched for age (usually within 8 years), diagnosis of particular autoimmune peripheral neuropathy, route of delivery of Ig, residual IgG titre (within 2·5 g/l) and gender. The replacement controls were also matched for type of primary antibody deficiency, presence of bronchiectasis, presence of splenomegaly and CVID phenotype, if relevant. Eighty-one per cent of pairs (25 of 31) were matched with every criterion stated, and the remaining 19% of pairs were matched for the majority of criteria. Priority was given to matching for diagnosis and complications, including bronchiectasis, that are known to affect efficacy 13,23. Matching was completed with the operator blinded to the dose received by each patient.

Standard Ig doses 1,17 were used as the starting point for dosing at both participating centres. However, crucially for this analysis, the physicians titrated the doses and infusion intervals up or down depending on clinical outcome. This study relies upon achieving the best clinical outcome and then determining retrospectively how much Ig was required to achieve that clinical outcome in the presence or absence of obesity, given that other significant factors have been matched. Within a matched pair, the lean partner had an average or low BMI (< 30 kg/m2) while the obese partner had a BMI > 30 kg/m2. The mean dose/month and the IgG increment was calculated from the mean stable IgG trough level minus the residual (pretreatment) IgG.

To determine if there was a significant difference between the dose of Ig required to achieve a given clinical outcome (i.e. stability) in lean and obese patients, two statistical analyses were undertaken.

A comparison was made between the slopes of the linear regression relationship between IgG trough and Ig dose, and IgG increment and Ig dose for lean and obese patients using t-tests for the comparison of intercepts and slopes. The significance of the regression relationship was tested using the t-test for the regression slope.

The mean Ig efficiency index was compared between controls and patients using a two-sample t-test. The formula used here to calculate efficiency was:

Efficiency = increment per day/Ig dose per week

This is adapted from the original efficiency concept described by Gouilleux-Gruart et al. 23, to take into account the fact that in patients dosed by the subcutaneous (s.c.) route the IgG trough (steady state) may be measured at days 4 or 7, as well as the larger variability in infusion interval in those using the intravenous (i.v.) route (manuscript submitted).

These analyses were performed on the entire cohort (n = 62) and repeated for the immunomodulation and replacement subgroups (n = 30 immunomodulation and n = 32 replacement).

Results

IgG trough versus Ig dose

In order to determine if obese patients achieved a higher IgG trough level for a particular dose of Ig, the weight-adjusted dose (g/kg/month) was plotted against IgG trough level (g/l) for all 62 patients; the resulting graph is shown in Fig. 1a. The obese cohort achieved significantly higher trough levels than lean patients (P = 0·00009).

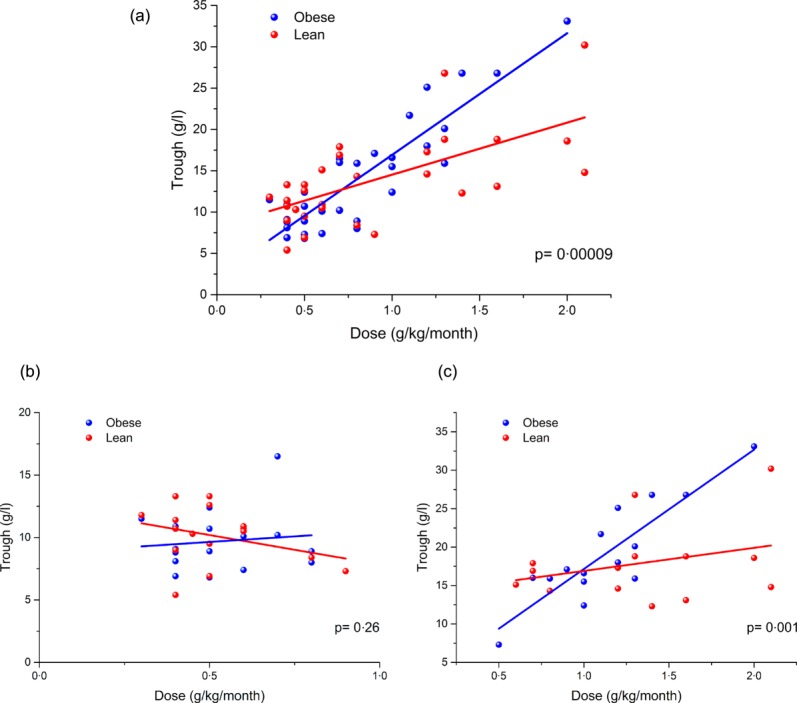

Figure 1.

Trough immunoglobulin (Ig)G plotted against Ig dose for (a) all patients, (b) replacement patients only and (c) immunomodulation patients only. Data points relating to obese patients are shown in blue and lean patients are shown in red. Simple linear regression of the data sets is shown in the respective colour.

However, when separated by indication (Fig. 1b,c), no significant difference was detected when comparing obese and lean patients receiving replacement therapy (P = 0·26), although there was a significant difference (P = 0·001) between those treated for immunomodulation despite the reduction in patient numbers.

IgG increment versus Ig dose

Because the high-dose patients are immunocompetent in terms of IgG level and have normal (residual) IgG levels before treatment, we analysed the increment for each patient (i.e. the trough level minus the residual IgG concentration at baseline) to calculate the increase in IgG plasma concentration for a unit dose of Ig. If the adipose tissue of obese patients is penetrated poorly by Ig, then plasma concentrations should be increased disproportionately in obese patients.

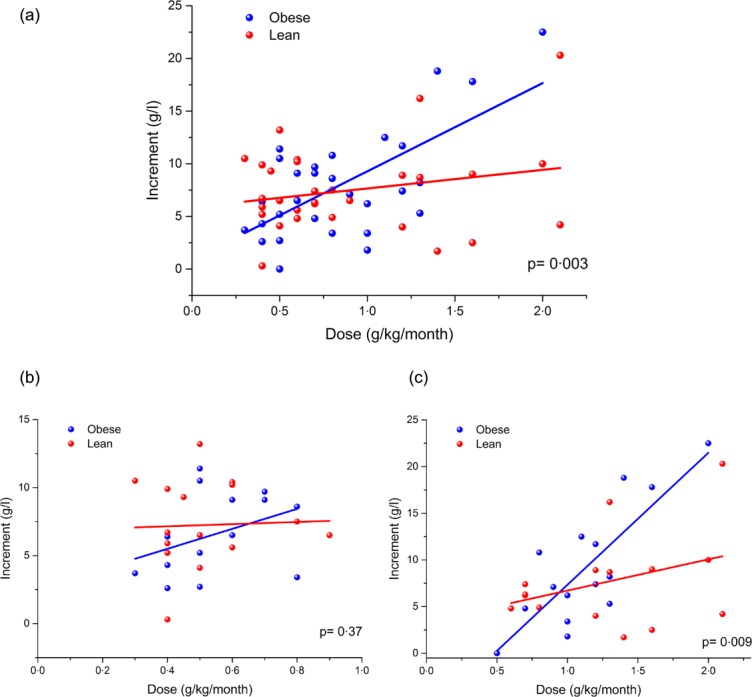

The calculated IgG increment is plotted against Ig dose for all patients in Fig. 2a, and a trend towards a larger increment/dose for obese patients is demonstrated by the steeper linear regression gradient in the obese cohort. The difference in the gradient of the linear regression for obese and lean was statistically significant (P = 0·003), and the analysis was repeated with the patients separated by indication (Fig. 2b,c). No statistically significant difference could be detected in those patients receiving Ig replacement therapy (P = 0·37); however, a statistically significant (P = 0·009) difference was found in the immunomodulation cohort.

Figure 2.

Immunoglobulin (Ig)G increment plotted against weight-adjusted Ig dose for (a) all patients, (b) replacement patients only and (c) immunomodulation patients only. Data points relating to obese patients are shown in blue and lean patients are shown in red. Simple linear regression of the data sets is shown in the respective colour.

Clinical impact of pharmacokinetic differences

The data show that, on average, for every gram of Ig prescribed, obese patients receiving immunomodulatory therapy will exhibit a greater increase in plasma concentration, but that there is no difference between obese and lean patients at lower replacement doses. As the doses used in these patients were adjusted to maximize clinical outcome, we also compared the weight-adjusted doses needed to achieve the desired clinical outcome. The use of a matched-pairs design minimizes population bias, resulting in comparable cohorts, but also ensures that each obese patient can be compared directly with a clinically equivalent lean control. Figure 3 shows the difference in the weight-adjusted monthly dose received by the obese and lean partner in each matched pair. The matched pairs were dosed according to clinical outcome, and therefore the difference is indicative of whether the lean or obese patient required more Ig to achieve the clinician's therapeutic aim.

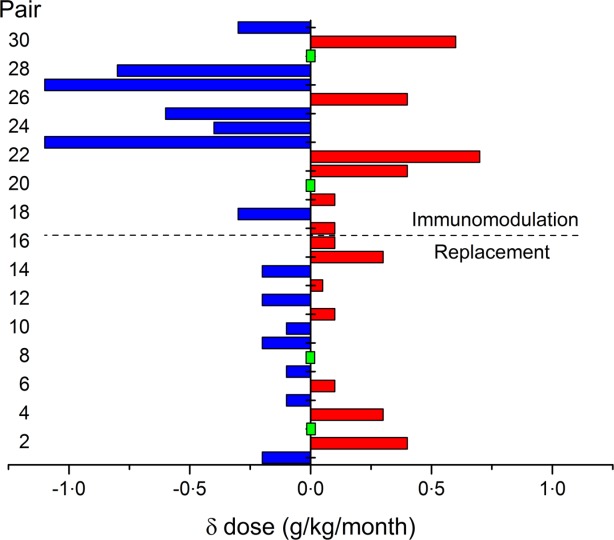

Figure 3.

The difference in the immunoglobulin (Ig) dose required to achieve the desired clinical outcome in matched pairs. In pairs where the obese patient required a larger weight adjusted dose (g/kg/month) compared with the lean match, the bar is coloured red and extends on the positive side of the x-axis. If the obese patient required a smaller dose than the lean match the bar is coloured blue and extends to the negative side. Where a green rectangle is shown, there was no difference in the monthly weight-adjusted dose for the matched pair. The replacement pairs are numbered 1–16 and the immunomodulation pairs are shown in bars 17–31.

Sixteen pairs received replacement Ig; in seven pairs, the obese partner required a larger weight-adjusted dose, in seven pairs the lean partner required a larger-weight adjusted dose and in two pairs there was no difference (pairs 1–16 in Fig. 3). In the majority of replacement pairs (nine versus seven) there was actually very little difference (≤ 0·1 g/kg/month) in the weight-adjusted dose required by obese and lean to achieve clinical equivalence.

In the immunomodulation regime (pairs 17–31), it was marginally more common (in seven versus six pairs – not statistically significant) for the obese patients to require a lower dose of Ig compared to the lean match, but in some cases the difference was large (up to 1·1 g/kg/month), and could amount to a significant cost saving. However, in a significant minority of pairs (40%, or six of 15 pairs) the opposite was true, and the obese patient actually required a larger weight-adjusted dose when compared with the lean partner. In the immunomodulation group there were four pairs where there was little or no difference (≤ 0·1 g/kg/month) in the weight-adjusted dose required to achieve clinical equivalence.

These data suggest that BMI is a poor predictor of the dose level that would achieve a good clinical outcome in individual patients.

Ig efficiency versus Ig dose

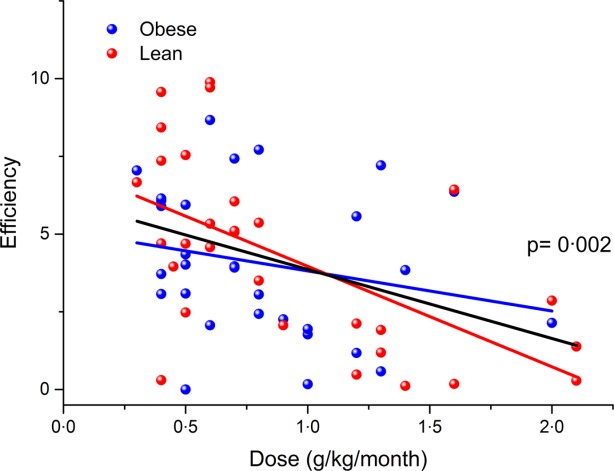

The Ig efficiency index, which is a measure of the increase in plasma IgG for a unit dose of Ig, was calculated 23. In order to take into account the different dosing frequencies of s.c. and i.v. formulations, the formula had been updated (see Methods). The resulting data are plotted in Fig. 4. No significant difference was observed in the efficiency of Ig doses when the obese cohort was compared with the lean cohort (P = 0·10), but a statistically significant negative association was found between dose and efficiency when both cohorts were considered as one population (P = 0·002). This shows that higher doses are less efficient, which may be due to saturation of FcRn and therefore increased catabolism.

Figure 4.

Immunoglobulin (Ig) efficiency index plotted against weight-adjusted IgG dose with obese patients shown in blue, and lean patients shown in red. Simple linear regression of the data sets is shown in the respective colour and the association between dose and efficiency is shown in black (with P-value).

Discussion

The findings in this study indicate that obese patients achieve a higher trough IgG level per unit dose of Ig on average when compared with lean patients, particularly those receiving Ig for immunomodulation therapy. This was confirmed by considering the increase in IgG plasma concentration for each gram of Ig prescribed. It was shown that the increment was greater in the obese patients compared with the lean patients, and was particularly evident in the subgroup receiving Ig for immunomodulation. No such differences were seen when the subgroup of patients receiving replacement Ig was analysed separately.

However, despite these findings, in some pairs the obese individual required a higher weight-adjusted dose to achieve the same clinical outcome as the lean match. This shows that clinical outcome depends on several factors unrelated to BMI and that patient characteristics other than BMI have a greater influence in determining the dose required for efficacy. The immunomodulatory indications for Ig treatment include numerous diseases with different basic characteristics. In order to ensure that these results are not confounded by such variables we have limited the conditions to autoimmune neuropathies, so similar studies may be required for other diseases in which immunodulation by high-dose Ig is efficacious.

The finding that lean and obese patients exhibit different pharmacokinetics at a population level supports the very low volume of distribution (Vd = 0·04–0·1 l/kg) that has been calculated for Ig 24 and is consistent with a drug that is largely confined to the plasma and extracellular spaces.

The analyses here were carried out by cohort (all obese versus all lean), but also analysed further by indication (replacement or immunomodulation). The finding that PK differences could not be detected in PID patients receiving Ig is wholly consistent with the two large replacement-only studies 18,19, and is further evidence that if obesity has any effect on trough level, it is too small to impact upon clinical practice in PID.

Patient characteristics, including FcRn genotype, presence of bronchiectasis and inflammatory state, etc. result in huge individual variability of Ig PK in seemingly homogeneous populations 24–26. For this reason, individualization of Ig dosing is already recommended in PID 1,13,26–28; this study lends further support to the appropriateness of this approach, and extends this principle to immunomodulation. Immunologists are advised to continue to strive for the minimum clinically effective dose in all individuals.

This study indicates that it may be possible to reduce the dose in some individual obese patients without compromising clinical outcome, and also conserve resources. However, the contrary is also true for those obese patients in whom a poor clinical response indicates that they should be tried on an increased Ig dose. An example from this cohort is a 96-kg female who required 190 g Ig/month to keep multi-focal motor neuropathy under control. The wide variation in the Ig dose required to control multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN) effectively in individuals was confirmed in a recent report that cited that doses in the range of 20–200 g/month were necessary for efficacy 29. Increases in dosage should be carried out cautiously in view of the increased risk of complications in obese patients. Headaches are the most common side effect and treatable with mild analgesia, but potentially serious adverse reactions, such as renal complications or thromboembolic events, are likely to be more common in obese patients 30.

No significant difference in efficiency was found between lean and obese patients (Fig. 4); however, a significant association was observed when the entire patient population was considered, whereby the efficiency dropped with increasing Ig dose. This may reflect that patients who receive low doses recycle IgG through the FcRn more effectively, which is of pivotal importance for Ig half-life 31. Saturation of this pathway by high-dose Ig treatment 32 or a specific FcRn genotype that has a significant effect in individuals 33 could result in a patient exhibiting low efficiency. Additionally, chronic inflammation including bronchiectasis may increase Ig catabolism or loss34.

A further flaw in the use of a purely PK argument or BMI for dosing is that these measures do not take into account variations in muscle mass and bone density and would prejudice against any individuals of athletic build 5, and no such individuals were included in this study. Also of note is the fact that men and women of the same BMI have a significantly different adipose tissue content 35,36. Gender distribution in this study was equal, but gender differences may be important on an individual basis.

Ig immunomodulatory dosing in obese patients should be on an individual basis according to clinical outcome, starting with the recommended dose for the disease, and then titrated up or down to the most clinically effective dose.

Conclusion

In this study we have shown that the pharmacokinetics of Ig in obese and lean patients is significantly different at a cohort level. However, due to the huge amount of patient variability, the influence of obesity on the clinically appropriate dose of Ig is too unreliable at an individual level to justify application of a general reduction in dose for all patients with a BMI exceeding 30. This is particularly true for PID patients where no difference in the two cohorts could be demonstrated, and individualized dosing is already practised. In patients receiving Ig for immunomodulation we conclude that it may be possible to reduce the dose in some obese patients relative to their lean equivalents without affecting outcome; however, this should only be undertaken on an individual basis once the patient has been stabilized, and is not appropriate for all patients.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients and their primary care physicians for excellent data capture, including BMI information, and also to the clinicians who look after the patients: Drs Siraj Misbah, Smita Patel, Jenny Lortan, Rashmi Jain, Hadi Manji and Professor Mary Reilly. We are also grateful to the staff at the Immunology Laboratory at the Churchill Hospital and the Biochemistry Department at UCLH for the monitoring of serum IgG levels. This study was funded by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre Programme and by the UK Primary Immunodeficiency Association (PIA) Centre of Excellence award, Jeffrey Model Foundation NYC and Baxter Healthcare LA (H. C., M. L.). M. P. L. is partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

Author contributions

J. H. designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the paper. M. L. collated the Oxford data and reviewed the paper. M. Lee carried out the statistical analysis. M. H. and M. P. L. collated the London data and reviewed the paper. H. C. designed the study, analysed the data and reviewed the paper.

Disclosures

J.P.H. is employed by a manufacturer of IVIg. M. P. L. has received honoraria from Baxter Pharmaceuticals, Grifols UK, CSL Behring and LFB within the last 10 years and was a co-investigator on a study of IVIg in CIDP (Comi et al. (2002) J Neurol 249:1370–7). H. C. is a consultant for Biotest and LFB and has worked as a consultant for Baxter Healthcare, Grifols and CSL Behring. M. H. has received an honoraria payment for speaking at the British Association of Neurology Nurses conference for Grifols. In addition he received reimbursement of travel and hotel costs from Grifols for speaking at this conference. He has received travel reimbursement for attending a meeting hosted by CSL Behring in Madrid relating to an immunoglobulin research study and also travel and hotel reimbursement for attending a site meeting and meeting of UK Neurology Nurses Forum, hosted by CSL Behring in Switzerland. His previous employer (UCLH NHS Foundation Trust) also received funding for 2 years to fund his previous post of Home IVIg Clinical Nurse Specialist, from a number of the companies who manufacture immunoglobulin including Grifols, Baxter Pharmaceuticals, CSL Behring, Octopharma and BPL.

References

- European Medicines Agency. 2010. Guideline on core SmPC for human normal immunoglobulin for intravenous administration.

- Hall R, Jean G, Sigler M, Shah S. Dosing considerations for obese patients receiving cancer chemotherapeutic agents. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:1666–74. doi: 10.1177/1060028013509789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai MP. Drug dosing based on weight and body surface area: mathematical assumptions and limitations in obese adults. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:856–68. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2012.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasperek M, Wetmore R. Considerations in the use of intravenous immune globulin products. Clin Pharm. 1990;9:909–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolfrey S, Dewar M. Treatment of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura using a dose of immunoglobulin based on lean body mass. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:510–5. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Wang E, Balthasar J. Monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:548–58. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poduslo JF, Curran GL, Berg CT. Macromolecular permeability across the blood–nerve and blood–brain barriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5705–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubogu EE. The molecular and biophysical characterization of the human blood–nerve barrier: current concepts. J Vasc Res. 2013;50:289–303. doi: 10.1159/000353293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han P, Duffull S, Kirkpatrick C, Green B. Dosing in obesity: a simple solution to a big problem. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82:505–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leykin Y, Miotto L, Pellis T. Pharmacokinetic considerations in the obese. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2011;25:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S. Biologics: an update and challenge of their pharmacokinetics. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15:271–90. doi: 10.2174/138920021503140412212905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borvak J, Richardson J, Medesan C, et al. Functional expression of the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, in endothelial cells of mice. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1289–98. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas M, Lee M, Lortan J, Lopez-Granados E, Misbah S, Chapel H. Infection outcomes in patients with common variable immunodeficiency disorders: relationship to immunoglobulin therapy over 22 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misbah S, Kuijpers T, van der Heijden J, Grimbacher B, Guzman D, Orange J. Bringing immunoglobulin knowledge up to date: how should we treat today? Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;166:16–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demand management plan for immunoglobulin use. Department of Health. 2008.

- Department of Health . Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention agenda. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Qualityandproductivity/QIPP/index.htm (accessed 27 January 2012)

- 2011. Clinical Guidelines for Immunoglobulin use. Department of Health, 2nd edn. Updated edn.

- Khan S, Grimbacher B, Boecking C, et al. Serum trough IgG level and annual intravenous immunoglobulin dose are not related to body size in patients on regular replacement therapy. Drug Metab Lett. 2011;5:132–6. doi: 10.2174/187231211795305302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro R. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin (16 or 20%) therapy in obese patients with primary immunodeficiency: a retrospective analysis of administration by infusion pump or subcutaneous rapid push. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;173:365–71. doi: 10.1111/cei.12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Data Solutions and Services (MDSAS) Third National Immunoglobulin Database Report. Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Katz U, Achiron A, Sherer Y, Shoenfeld Y. Safety of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6:257–9. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrock DJ. Adverse events associated with intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouilleux-Gruart V, Chapel H, Chevret S, et al. Efficiency of immunoglobulin G replacement therapy in common variable immunodeficiency: correlations with clinical phenotype and polymorphism of the neonatal Fc receptor. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;171:186–94. doi: 10.1111/cei.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleba T, Ensom MH. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous immunoglobulin: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:813–27. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.6.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla FA. Pharmacokinetics of immunoglobulin administered via intravenous or subcutaneous routes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:803–19. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, Rojavin M, Kiessling P, Zenker O. Pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous immunoglobulin and their use in dosing of replacement therapy in patients with primary immunodeficiencies. Clin Immunol. 2011;139:133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonagura VR, Marchlewski R, Cox A, Rosenthal DW. Biologic IgG level in primary immunodeficiency disease: the IgG level that protects against recurrent infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:210–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orange JS, Grossman WJ, Navickis RJ, Wilkes MM. Impact of trough IgG on pneumonia incidence in primary immunodeficiency: a meta-analysis of clinical studies. Clin Immunol. 2010;137:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlam L, Cats EA, Willemse E, et al. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous immunoglobulin in multifocal motor neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:1145–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M. Adverse effects of IgG therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:558–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Zhao M, Hilario-Vargas J, et al. Complete FcRn dependence for intravenous Ig therapy in autoimmune skin blistering diseases. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3440–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI24394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao JJ. Pharmacokinetic models for FcRn-mediated IgG disposition. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:282989. doi: 10.1155/2012/282989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberger T, Grodecká L, Ravcuková B, et al. Association of FcRn expression with lung abnormalities and IVIG catabolism in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol. 2010;136:419–25. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cildir G, Akıncılar SC, Tergaonkar V. Chronic adipose tissue inflammation: all immune cells on the stage. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:487–500. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, Jebb SA, Murgatroyd PR, Sakamoto Y. Healthy percentage body fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:694–701. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deurenberg P, Weststrate JA, Seidell JC. Body mass index as a measure of body fatness: age- and sex-specific prediction formulas. Br J Nutr. 1991;65:105–14. doi: 10.1079/bjn19910073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M. Jeffrey A. Optimizing IgG therapy in chronic autoimmune neuropathies: a hypothesis driven approach. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51:315–26. doi: 10.1002/mus.24526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]