Abstract

Several studies have examined the impact of a number of minimum legal drinking age 21 (MLDA-21) laws on underage alcohol consumption and alcohol-related crashes in the United States. These studies have contributed to our understanding of how alcohol control laws affect drinking and driving among those who are under age 21. However, much of the extant literature examining underage drinking laws use a “Law/No law” coding which may obscure the variability inherent in each law. Previous literature has demonstrated that inclusion of law strengths may affect outcomes and overall data fit when compared to “Law/No law” coding. In an effort to assess the relative strength of states’ underage drinking legislation, a coding system was developed in 2006 and applied to 16 MLDA-21 laws. The current article updates the previous endeavor and outlines a detailed strength coding mechanism for the current 20 MLDA-21 laws.

Introduction

Background

It is a widely maintained misperception that the minimum legal drinking age of 21 (MLDA-21) in the United States (US) is embodied in a single law and, therefore, all states have the same law. In actuality, the MLDA-21 has multiple provisions targeting outlets that sell alcohol to minors; adults who provide alcohol to minors; and underage persons who purchase or attempt to purchase, possess, or consume alcohol. The Federal Government adopted legislation in 1984 that provided strong incentives—the risk of losing substantial highway construction funds—for the states to adopt a uniform minimum drinking age of 21. By 1988, each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) had passed laws that made it illegal for persons under the age of 21 to possess and purchase or attempt to purchase alcohol. Later, all states and DC enacted laws prohibiting the furnishing or selling of alcohol to individuals under the age of 21 years. To support the core MLDA-21 laws, states have also expanded MLDA-21 laws that target youth. For example, since drivers under age 21 are not supposed to consume any alcohol, zero tolerance (ZT) laws were adopted that provide for lower blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limits for drivers under the age of 21 years. Graduated driver licensing (GDL) laws with nighttime driving restrictions have also been adopted which limit underage drivers’ availability to alcohol and their drinking and driving. Laws making it illegal for youth to use fake identification in order to purchase alcohol have also been passed by the states. Other MLDA-21 laws focus on affecting the behavior of those who sell or furnish alcohol such as those that mandate beer keg registration (or regulation), prohibitions on hosting underage drinking parties, and civil liability laws targeting commercial and non-commercial providers of alcohol to underage youth, among others. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) within the US Department of Transportation estimates that MLDA-21 laws have reduced traffic fatalities involving youth by 13% (NHTSA 2014). However, these laws vary considerably from state to state, and only one state has all 20 legal components that we have documented (i.e. Utah). Comparatively, Kentucky has adopted only 9 of the 20 MLDA-21 laws we document in this article. In addition, many MLDA-21 laws in the states have numerous exceptions, weak sanctions for violations, and make enforcement very difficult. Thus, the current U.S. effort to control underage drinking involves a variable package of legislative measures, some of which have very strong provisions while others contain numerous exemptions and make enforcement difficult.

Several studies have been conducted to determine the impact of drinking age laws on underage alcohol consumption and alcohol-related crashes. Many of these studies have demonstrated that the prohibition of youth from possessing alcohol and the prohibition of youth from purchasing alcohol (the two core MLDA-21 laws) reduce underage drinking-and-driving fatalities substantially (e.g., Arnold, R. 1985; Decker, M.D., Graitcer, P.L., and Schaffner, W. 1988; O'Malley, P.M. and Wagenaar, A.C. 1991; Ponicki, W.R., Gruenewald, P.J., and LaScala, E.A. 2007; Shults, Ruth A. et al. 2001; Toomey, Traci L., Rosenfeld, Carolyn, and Wagenaar, Alexander C. 1996; Wagenaar, A.C. and Toomey, T.L. 2002; Williams, A.F. et al. 1983; Womble, K. 1989).

These studies have contributed to our understanding of how MLDA-21 laws affect drinking and driving behaviors among those who are too young to legally consume alcohol. Specifically, Fell and his colleagues (Fell, James C. et al. 2009) examined six laws that: (1) make it illegal for underaged individuals to publicly possess alcohol, (2) make it illegal for underaged individuals to purchase or attempt to purchase alcohol, (3) mandate that beer kegs be registered to the purchaser, (4) establish negligible BAC limits (i.e., zero tolerance) for alcohol in underage drivers, (5) establish GDL systems with nighttime restrictions to reduce youth access to alcohol, and (6) implement “use and lose” penalties resulting in an underaged driver’s license being suspended in the event of an alcohol violation. In that 2009 study, researchers examined the effective dates for each of these laws to determine if their enactment significantly affected the ratios of underage drinking drivers to underage non-drinking drivers in fatal crashes (called the crash incidence ratio [CIR], in the corresponding year and beyond. The CIR measure has been recommended for these types of studies [see (Voas, R.B. et al. 2007)]. The authors found that the possession and purchase laws—which were combined because the two had identical effective dates—were significantly associated with a reduction in the CIR outcome measure of 16%, while use and lose laws and ZT laws were associated with reductions of about 5% each. Curiously, Fell and colleagues in that study found that keg registration laws were associated with increases in the CIR measure by about 12%, whereas GDL with nighttime restrictions had no significant impact on the underage CIR.

Despite the utility of this work, the 2009 study focused on the presence/absence of laws, without taking into account inherent variations across states in the provisions of these laws that may influence their effectiveness. For researchers and policy makers to have a clearer understanding of how laws affect various outcomes—such as underage alcohol-related fatal crashes—studies need to account for variations in the strengths of each of these laws that occur from state to state. Polychotomous variables that address variations and exceptions in laws have been shown to be more useful in descriptive policy studies than dichotomous “Law/No Law” variables, which may obscure variability in law. This kind of research can also bring to light any unintentional consequences of these laws. The process for measuring a law for evaluation and public health research is described in detail in two recent publications (Tremper, C., Thomas, S., and Wagenaar, A.C. 2010a and 2010b).

In the United States, Nelson et al. (2013) used a panel of ten alcohol policy experts to rate the efficacy of alcohol control policies for reducing binge drinking and alcohol-impaired driving among both youth and adults. A total of 47 policies were nominated on the basis of scientific evidence and potential for public health impact. Policies limiting price received the highest efficacy ratings and the efficacy ratings for all the policies were positively correlated with reducing binge drinking (r=0.50) and alcohol-impaired driving (r=0.45). This study differed from our scoring in that the ratings were for the potential effectiveness of the policies rather than the strengths and weaknesses of the policies as we have performed.

Internationally, although not focused on laws pertaining specifically to underage drinking, Brand et al. (2007) developed an Alcohol Policy Index (API) to gauge the strength of alcohol control policies in 30 countries based on 16 policy topics comprising five domains: alcohol availability, drinking context, price, advertising, and motor vehicles. The authors found that the overall API was inversely associated with per capita alcohol consumption in the 30 countries. Then, Paschall, Grube & Kypri (2009) used the Brand et al. data and found that the overall API score, and the alcohol availability domain rating in particular, were inversely related to national prevalence rates of any past-30-day alcohol use and frequent alcohol consumption among adolescents.

Methods

Initial Scoring

To assess the relative strength of states’ underage drinking legislation, a coding system was initially developed in 2006 that was applied to the provisions of the myriad MLDA-21 laws in an effort to distinguish relatively strong laws from those that are comparatively weaker. Based on the coding, each state received a score for each law that ranged from 0 (no law) to a maximum total score reflecting the strongest existing law. These scores varied considerably across the different laws (Fell, J.C. et al. 2008). The scoring system was developed to code the different provisions of the laws such that scores would reflect the potential deterrence value of each law. To do this, the absence of a law resulted in a total score of 0. Because the number and types of provisions that are available for coding in data sources such as APIS vary across laws, we used the following strategy. If a law's provisions related to exceptions to the law's application, which should facilitate youth access (e.g., laws regarding possession, consumption), then we selected a starting score for the law that was 1 point higher than the sum of all exceptions that could possibly be applied (highest values of different distinct variables). With this approach, a state that had a law but that provided many exceptions would get a final score of 1; fewer or less expansive exceptions would yield a higher score. In the case of laws where the information in data sources related to provisions that strengthen the law (e.g., different types of license sanctions for violations by youth, different lengths of time for license suspensions for Zero Tolerance), the values of different provisions were added to a starting score of 0. In each case—whether starting with a total score and deducting points for provisions that facilitate youth access/drinking or starting with a score of zero and adding points for provisions that should deter youth access/drinking—the different options within each ordered variable/provision were weighted so that more liberal exceptions led to greater deductions and stronger supporting factors received higher additions to scores.

Applying the Scoring

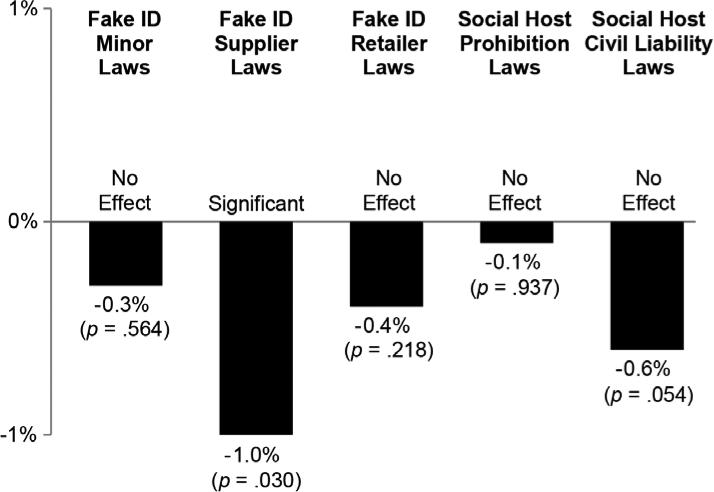

With this refined scoring methodology, Fell and his colleagues (Fell, J.C. et al. 2014, in press) later expanded on their original study by examining five new laws that : (1) make it illegal for underage individuals to possess false identifications (FID), (2) support retailers by allowing them to take action against minors using FID, (3) prohibit the production or transfer of FID, (4) impose civil liability on noncommercial alcohol providers for injuries or damages caused by their intoxicated or underage drinking guests (social host civil liability) and (5) impose liability on individuals responsible for underage drinking events on property they own, lease, or otherwise control (prohibitions against hosting underage drinking parties). They found that prohibiting the transfer/production of FID was associated with reductions in underage drinking driver fatal crash ratios by 1.0% (p<.03) and social host civil liability laws were associated with reductions in underage drinking driver crash ratios by 0.6% (p<.054), not quite statistically significant. Neither of the other two FID laws nor the underage drinking party prohibition laws were found to have a significant impact on underage drinking driver fatal crash ratios. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Effects of Five MLDA-21 Laws on the Ratio of <Age 21 Drinking Drivers to <Age 21 Non-Drinking Drivers in Fatal Crashes Using Law Scores [Source: FARS 1982-2010]

Of note, in the above study, Fell and his colleagues examined the strengths of the laws. Specifically, all three FID laws, prohibitions on hosting underage drinking parties, and social host civil liability laws were given a score for each state based on the sanctions imposed, exemptions made to enforcing the law, or policies affecting the law while simultaneously controlling for a host of non-alcohol related factors. To do this, the research team utilized the previous cited research in which they conducted an extensive review of 16 MLDA laws and scored them according to the sanctions imposed for violating the law and exemptions to the enforcement of the law (Fell, J.C. et al. 2008).

The study of fake identification and laws imposing criminal and civil sanctions for serving as social hosts illuminated an important factor in the examination of how laws affect fatal crash ratios. In particular, their work provided support for the necessity to more accurately gauge how a law and its strength may affect underage drinking driver fatal crashes. Indeed, that study found that including the strength of the laws into structural equation models (SEM) resulted in altered outcomes; inclusion of law strengths into the SEM model slightly increased the overall fit statistics when compared to the model without the law strengths. The comparative fit index went from .404 in the model without the strengths to .414 in the model with the strengths. The normed-fit index went from .400 without the strengths to .410 with the strengths. Finally, the root mean square error of approximation was reduced from .194 without the strengths to .186 with the strengths. These changes may seem trivial, but they are important changes in analyses such as these. As MLDA-21 laws are amended or new laws are adopted by states, the nature of prohibitions, penalties and exceptions may change over time. Hence, it will be necessary to reexamine the laws that are scored and how the scoring was performed. To this end, this article updates and enhances the scoring scheme for the laws outlined in the 2006 endeavor and adds four new laws that were previously unexamined and unscored.

Theoretical Model

Theoretically, a law that is strong, is able to be enforced, has few or no exceptions, and has meaningful sanctions for any violations should have a general deterrent effect on the behavior of would-be violators (Ross, 1982; 1992). For example, if a possession law has no location or family exceptions, it can be easily enforced by law enforcement at underage drinking parties, and a drivers’ license suspension of 6 months is the administrative sanction for a violation, that law is considered strong and should have an effect. On the contrary, a law that is weak, difficult to enforce, has numerous exceptions and limited, if any, sanctions, should not have the same general or specific deterrent effect.

Using the lessons from these prior attempts in the U.S. and internationally to create a comprehensive scoring system for underage laws pertaining to alcohol use, this article updates the scoring scheme for the laws outlined in our earlier endeavor and adds four new laws which were previously unexamined.

Data Sources for Underage Drinking Laws

The primary source for data on underage-drinking laws in the United States is the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism's (NIAAA) Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) dataset (NIAAA 2013). Coverage in APIS varies among policy topics due to the availability of historical data. APIS provides information on 17 of the 20 laws examined in this study. For GDL laws, information from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) (2013) was used. Finally, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA) Report to Congress on the Prevention and Reduction of Underage Drinking (SAMHSA 2012) was used to obtain information on dram shop liability and social host civil liability laws. The process for documenting these laws is described in Tremper et al. (2010a and 2010b).

Updates to the 2006 Law Strength Scores

For the current update, we used the same system for scoring that was used in 2006 scoring project. The system was developed by specialists in alcohol policy including two members of the APIS team who code all the policy topics on APIS. These experts assigned points for provisions of laws that are meant to deter young people from using alcohol and deducted points (i.e., reduced scores) for provisions that increase the likelihood of underage alcohol use or that make law enforcement more difficult. These assessments of the core and expanded laws were based on empirical evidence, where it exists, and/or reasoned theoretical arguments. Provisions such as family member and location exceptions, the type and severity of sanctions for violations, and applicability of the law across situations or substances (e.g., beer, wine, and distilled spirits) were among the variables coded. In all cases, the scoring was designed so that a value of zero corresponds with a state not having a law and higher values represent stronger laws. Such a scoring scheme is similar to that developed by the IIHS in its assessment of key components of GDL (IIHS, 2007). Because each law differs in the number of provisions assessed (and possible point additions or deductions), the base scores and total scores that are possible vary across the laws. Thus, the maximum possible number of points for a law does not imply relative importance of that law compared to the other laws. Each law's point scale is independent, and the magnitudes of scores are not comparable between laws. These differences between laws in range and absolute value of their scores, however, do not affect the statistical analyses (i.e., do not make one law inherently more likely to predict the outcome measure). This is the case because the analyses examine whether each law's distribution of scores correlates with the variation in underage drivers in fatal traffic crashes.

In general, the 20 MLDA-21 laws used in this study were scored based upon (1) the sanctions enacted for violating the law, (2) any exceptions or exemptions affecting the application and enforcement of the law, and (3) any provisions that could affect the law or its enforcement negatively or positively. Two legal researchers initially scored the laws for half the states, then exchanged states and checked each other for accuracy. Those resultant scores were then reviewed by the rest of the expert panel: a research psychologist, a senior statistician, a clinical psychologist, a social psychologist and a human factors engineer, all familiar with underage drinking laws and research on these laws. Any altered scores were reviewed again and approved by all the experts. The Expert Panel is presented in Appendix A.

In 2006, a total of 16 laws were coded; in 2012, 20 laws related to alcohol use by minors were coded. The increase in 4 laws occurred for two reasons. First, in the interim 6 years between studies, data on dram shop liability and social host civil liability laws became available from SAMHSA's Report to Congress on the Prevention and Reduction of Underage Drinking. Second, in 2012, provisions for two sets of laws—possession of alcohol and age of on-premises servers and bartenders—were separated into more distinct policy topics. In 2006, the provision for internal possession (i.e., the use of biological evidence such as breath, blood, or urine to establish a minor's use of alcohol without evidence of possession or consumption) was coded as part of the possession statute. However, in 2012, this provision was coded as a separate law. Similarly, in 2006, provisions regarding age and other requirements for on-premises alcohol servers (e.g., waiters, waitresses) and bartenders were coded as a single law; in 2012, these provisions were coded as separate laws, one for servers and the other for bartenders.

In addition to the increase in sets of coded laws, some changes were made from the 2006 coding either in the number of provisions coded within a policy or the weights assigned to provisions. Typically, such changes altered the maximum possible score for a law coded in 2006, to more adequately address the importance of the provision to the overall law. For nine of the 20 laws coded in 2012, no changes were made in the manner of coding from 2006. There are three reasons for this type of expansion. First, additional laws are available in APIS that were not in the 2006 version of our research; second, APIS augmented variables in some of its policy topics, thereby providing additional information to add to our scores; and third, additional analysis of some of the policy topics led to more sophisticated delineation of the impact of the laws.

In 2012, the coding of four of the laws—underage possession, consumption, internal possession, and furnishing of alcohol—was augmented. In addition to including six conditional and unconditional location exceptions (e.g., youth can consume alcohol in a private location/private residence/parent or guardian's home with or without a parent or spouse's permission, respectively), there was a deduction of points for family member exceptions not predicated on location exceptions (see Results section for specific strength coding criteria). That is, if a state allows a youth under age 21 to consume or possess alcohol with a parent's or spouse's permission in any location (public or private), this was given a higher deduction of points than any of the conditional location exceptions because more opportunities for drinking are permitted which results in a weaker law. This unconditional family member exception resulted in a separate deduction of points separate from any other unconditional location exceptions that might exist in a state.

For laws relating to age requirements for on- and off-premises servers/sellers, the coding was adjusted slightly. In 2006, a requirement that servers/bartenders be age 21 was allotted 4 points. For States that allowed youth under the age of 21 to serve/sell alcohol, credit (+1 point each) was given for three required conditions (manager present, beverage service training, and parental consent). In 2012, because only one condition for allowing underage 21 youth to sell/serve alcohol was coded (i.e., manager present), the weight for requiring servers/sellers to be 21 was reduced to 2 points.

For Beverage Service Training in 2012, the category of trained personnel, “licensee”, was coded in addition to categories of “manager” and “server”, both of which were the only personnel coded in 2006. Additionally, in the 2012 coding scheme, the points applied to the training of personnel were scaled (+1 for licensee, +2 for manager, and +3 for server), whereas, in 2006, training of a manager and server were each allotted 1 point.

Finally, the policy prohibiting hosting of underage drinking parties also underwent revised scoring. The weights for the type of statute were +2 for general laws and +1 for laws that specifically applied to underage parties in 2006, and +4 and +3, respectively, in 2012. The remaining changes to the scoring of this law were associated with changes in the information provided in APIS. Between 2006 and 2012, an additional evidentiary standard (recklessness) was added to the level of knowledge required for legal liability against the person(s) who owns, leases, or controls the property in question. Also, one of the previous exceptions, in addition to family and resident, “other,” was eliminated. See Table 1 for a brief summary of the 20 MLDA-21 laws and any noted scoring changes or new laws that occurred between 2006 and 2012.

Table 1.

Minimum Legal Drinking Age 21 (MLDA-21) Law Components: Descriptions and Scoring Changes

| MLDA-21 LAW COMPONENTS | Description and Comment on Scoring |

|---|---|

| CORE LAWS THAT APPLY TO YOUTH: | |

| 1.Possession 2.Purchase |

Illegal for youth under age 21 to possess alcohol. Scoring change. Illegal for youth under age 21 to purchase or attempt to purchase alcohol. Possession and purchase were treated together as the laws that met federal standards by 1988 |

| EXPANDED LAWS THAT APPLY TO YOUTH: | |

| 3.Consumption 4.Internal Possession 5.Use and Lose |

Illegal for youth under age 21 to consume alcohol. Scoring change. Evidence of possession and consumption via a BAC test. New law. Alcohol citation for youth under age 21 results in drivers' license suspension |

| 6. Use of Fake Identification | FID minor – illegal for youth under age 21 to use a fake identification to purchase alcohol |

| APPLY TO YOUTH DRIVING: | |

| 7. Zero Tolerance | ZT – illegal for a driver under age 21 to have any alcohol in their system when driving |

| 8. Graduated Driver Licensing with Night Restrictions | GDL – youth with intermediate or provisional license prohibited from driving without an adult in the vehicle past a certain hour at night |

| APPLY TO PROVIDERS: | |

| 9.Furnishing or Selling | Illegal to furnish or sell alcohol to a youth under age 21. Scoring change. |

| 10.Age of On-Premise Servers | Minimum age set for selling/serving alcohol. Scoring change. |

| 11.Age of On-Premise Bartenders | Minimum age for bartenders. New law |

| 12.Age of Off-Premise Sellers | Minimum age set for selling/serving alcohol. Scoring change. |

| 13.Keg Registration | Identification number for beer keg and purchaser required |

| 14.Responsible Beverage Service Training | RBS – responsible beverage training mandatory or voluntary. Scoring change. |

| 15.Retailer Support Provisions for Fake Identification | FID Retailer – provisions to assist retailers in avoiding sales to youth under age 21 |

| 16.Social Host Prohibition | SHP – prohibits social hosting of underage 21 drinking parties. Scoring change. |

| 17.Dram Shop Liability | Action against commercial provider of alcohol. New law |

| 18.Social Host Civil Liability | Action against non-commercial (private) provider of alcohol. New law |

| APPLY TO MANUFACTURERS OR SUPPLIERS OF FAKE IDENTIFICATION: | |

| 19. Transfer/Production of Fake Identification | FID Supplier – prohibits manufacturing and/or supplying fake identification to youth for the purposes of buying alcohol |

| APPLY TO STATES CONCERNING CONTROL OF ALCOHOL DISTRIBUTION: | |

| 20. State Control of Alcohol Sales | State Control – a state-run retail distribution system of one or more of the alcohol beverage types |

Research into the efficacy of various alcohol-related policies have frequently examined their impact on two specific variables alcohol-related crash data and beer consumption (e.g., Brand et al., 2007; Fell et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 2003). To demonstrate the potential impact of incorporating law strengths, we sought to examine the differences between laws defined as strong using the current scoring method and those considered weak on measures of underaged alcohol related crash ratios and per capita beer consumption. However, because conducting detailed analyses on twenty laws in a single article would be impractical, two laws were selected to examine more thoroughly. Specifically, we selected Use and Lose laws and Zero Tolerance laws to examine as previous research has indicated that these two laws to be particularly effective in reducing both beer consumption and alcohol-related fatal crashes (Fell et al., 2009).

Underaged alcohol-related crash ratios

Annual traffic fatality data for each state was derived from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's (NHTSA) Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) from 1982 to 2012. The FARS is a continuous census of vehicular crashes which resulted in the death of an individual within the 30 days following the incident. To be registered in the FARS database, the crash must have (1) occurred on the U.S. public roadways, and (2) been attended and reported by police. The involvement of alcohol in the crash is derived from crash data to determine if there was sufficient information to conclude the driver had been drinking (e.g., positive BAC data from tests or police-reported alcohol involvement). This information was available in FARS for all years examined in the current study.

Beer Consumption

Per capita beer consumption rates were obtained for individuals aged 14 years and older by year and state. These data were obtained from the annual publication of the NIAAA's Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System.

Law Scores for All 50 States and Washington, DC as of January 2012

Table 2 provides each state's scores on each of the 20 key elements of state laws relating to underage drinking and underage drinking and driving discussed in the current article. Scores of “0” indicate that a state does not have a particular law or rather that they do have that particular law, but also have so many exemptions to the law as to make it largely ineffective and/or unenforceable. Generally, the higher score a state receives on a given law, the stronger the law is deemed or assessed to be. A state may receive a maximum score of 1.0 if they have a law at its maximum strength with no exemptions. The table represents a summary of the status (law/no law) and the relative strength of the 20 laws as of January 1, 2012. The highest overall standardized score was in the state of Utah and the lowest was in Kentucky. To obtain standardized law scores as demonstrated in Table 2, scores (as demonstrated in Tables 3 through 22 in Appendix B) are divided by the total possible scores for each law. For example, the maximum score for the Possession law is 11 points, and Maryland (MD) has a scored law strength of 9, then the standardized score for Maryland would be 9 (score MD received on Possession law)/11(total possible points any state can receive for Possession law) = 0.82. Below is a description of how each of the 20 laws was scored for each state.

Table 2.

Status and Strength of Key Underage Drinking Laws in the United States as of 2012

| #1 Possession | #2 Purchase | #3 Consumption | #4 Internal Possession |

#5 Use/Lose | #6 Fake ID Use | #7 Zero Tolerance | #8 GDL Night | #9 Furnishing | #10 Age Server | #11 Age Bartender | #12 Age Seller | #13 Keg Reg | #14 RBS | #15 Fake ID Retail | #16 Social Host Prohibition |

#17 Dram Shop | #18 Social Host Civil |

#19 Fake ID Production |

#20 Alcohol Control | Overall Standardized Score |

Number of Laws | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 15 |

| AK | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 15 |

| AZ | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 14 |

| AR | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 14 |

| CA | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 15 |

| CO | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 16 |

| CT | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 12 |

| DE | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 10 |

| DC | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 12 |

| FL | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 12 |

| GA | 0.91 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 11 |

| HI | 0.46 | 1.00 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 15 |

| ID | 0.82 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.52 | 14 |

| IL | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 12 |

| IN | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 15 |

| IA | 0.82 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 10 |

| KS | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 16 |

| KY | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.20 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 9 |

| LA | 0.27 | 0.50 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 14 |

| ME | 0.82 | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.55 | 18 |

| MD | 0.82 | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 12 |

| MA | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 13 |

| MI | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 15 |

| MN | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 13 |

| MS | 0.09 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 12 |

| MO | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 14 |

| MT | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 14 |

| NE | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 14 |

| NV | 0.09 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 14 |

| NH | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.58 | 17 |

| NJ | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.20 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 13 |

| NM | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 15 |

| NY | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 10 |

| NC | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 15 |

| ND | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 14 |

| OH | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 14 |

| OK | 0.46 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 13 |

| OR | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.91 | 0.40 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.56 | 15 |

| PA | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 15 |

| RI | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 13 |

| SC | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 15 |

| SD | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 11 |

| TN | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 12 |

| TX | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 12 |

| UT | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 20 |

| VT | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.44 | 12 |

| VA | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 13 |

| WA | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 16 |

| WV | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 11 |

| WI | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 14 |

| WY | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 17 |

| Avg. Str. | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.56 | 0.16 | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.75 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.48 | |

| Total with Law | 51 | 48 | 35 | 9 | 40 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 13 | 24 | 23 | 31 | 38 | 45 | 28 | 45 | 33 | 24 | 11 |

Core Laws

Laws That Apply to Youth

Possession

All states prohibit possession of alcoholic beverages by underaged individuals; however, many states apply various statutory exceptions. Location exceptions permit youth to legally possess alcohol in certain places, such as a private residence. Family exceptions allow youth to possess alcohol under certain conditions, such as the presence or permission of a family member (e.g., a parent/guardian or spouse). Possession refers to a container, not alcohol in the body. Several states have enacted separate internal possession provisions that permit police to press charges against underage drinkers because of the level of alcohol in their bodies (see Internal Possession law below).

The three location exceptions (any private location, any private residence, and parents’/guardians’ home only) represent an ordered variable. For any given state, only one location exception applies. Any private location is the least restrictive location exception and, thus, results in a larger point deduction from a state's base score than the exception for parents’/guardians’ home only, which is the most limited location exception. In addition, location exceptions may be conditioned on family variables (i.e., a minor may possess in any private location if a parent gives consent). Such situations are more circumscribed than a location exception that is unconditional (i.e., minor can possess in any private location). For any given location exception, conditional exceptions result in one-half the point deduction from the base score than the same unconditional location exception. In some cases, the parental or spousal exception is not conditioned on location. Because the parental or spousal exceptions may allow alcohol to be consumed in any location (public or private), it results in a higher deduction of points than any of the conditional scoring. With a base score of 11 points allotted for having a possession law, scores can range from 0 (no law) to a maximum of 11 (law with no location or family exceptions). See Table 3 for Possession scoring criteria and weights. Note that Tables 3 through 22 appear in Appendix B.

Purchase

States were coded as having this law if their policies specifically prohibit the purchase or attempted purchase of alcoholic beverages by minors. Many States have one or more exceptions to this law. See Table 4 for Purchase law scoring criteria and weights. With a base score of 1 point (for having an underage purchase law), states are coded as 0 (no law), and a maximum of 2 (law plus ability to use minors in compliance checks).

Expanded Laws

Laws that Apply to Youth

Consumption

Most states specifically prohibit underaged individuals from consuming alcoholic beverages. Note that, in most cases, this means observed drinking, not merely the presence of a positive BAC from a breath test. As with possession, many states have one or more statutory exceptions to this law. With a base score of 11 points allotted for having a consumption law, scores can range from 0 (no law or a law with so many exceptions as to make it ineffective) to a maximum of 11 (law with no location or family exceptions). See Table 5 for Consumption law scoring criteria and weights.

Internal Possession

Internal Possession provisions require evidence of alcohol in an underaged individual's body, as determined by a blood, breath or urine test, but that does not require any specific evidence of possession or consumption (such as a witness observation or an admission on the part of the minor). Similar to Possession laws, Internal Possession law scores can range from 0 (no law or a law with so many exceptions as to make it ineffective) to a maximum of 11 (law with no location or family exceptions). See Table 6 for Internal Possession law scoring criteria and weights.

Use and Lose: Driving Privileges

This term describes laws that authorize driver licensing actions against persons found to be using or in possession of illicit drugs, and against young people found to be drinking, purchasing and/or in possession of alcoholic beverages. States vary in how many of the alcohol violations (i.e., underage purchase, possession, consumption) lead to a Use and Lose violation as well as whether the license suspension or revocation for violating the law is mandatory versus discretionary. Scores range from 0 (no use and lose law) to a maximum of 8 (license sanction is mandatory for all three violations—purchase, possession, and consumption; minimum length of license suspension is 91+ days, and law applies to all youth younger than 21). See Table 7 for Use and Lose law scoring criteria and weights.

False Identification Provisions for Minors

All states prohibit the use of false identification cards by minors, therefore, scores range from 1 (law with no license sanction procedure) to a maximum of 3 (law with administrative or both administrative and judicial license sanction procedures). See Table 8 for False Identification law scoring criteria and weights.

Apply to Youth Driving

Zero Tolerance

In all states it is illegal for underaged individuals to drive with any measurable level of alcohol in their systems. States were coded as having this law if the minimum BAC limit for underage operators of noncommercial automobiles, trucks, and motorcycles was <.02. Scores range from 1 (discretionary criminal license sanction only with maximum suspension length of 30 days or less) to a maximum of 10 (mandatory administrative license sanction of 91 days or longer; minimum and mandatory criminal license sanction of 91 days or longer). See Table 9 for Zero Tolerance law scoring criteria and weights.

Graduated Driver License (GDL) with Nighttime Restrictions

GDL is a system in which beginning drivers are required to go through three stages of limited driving privileges. The first stage is a supervised learner's period; the second stage is an intermediate period in which unsupervised driving in high-risk situations is limited; and the final stage is a full-privilege driver's license. States were coded as having this law if they had a three-stage GDL system and if they had restrictions on unsupervised nighttime driving during the intermediate stage. Limitations on nighttime driving are designed to reduce drinking and driving by underage drivers. Nighttime restrictions for underage novice drivers may also reduce underage drinking since there may be limited means to get to the place of drinking. Scores range from 0 (no three-stage GDL with nighttime driving restrictions in intermediate phase) to a maximum of 3 (three-stage GDL with nighttime restriction starting at 10 p.m. or earlier). See Table 10 for GDL with nighttime restriction law scoring criteria and weights.

Laws Applying to Providers

Furnishing

All states have laws prohibiting the furnishing of alcoholic beverages to underaged individuals. As with possession and consumption, many states have one or more exceptions to this law. In some states, offenders may employ an affirmative defense on their behalf to mitigate consequences of violating this law. An affirmative defense example would be that the furnisher inspected the youth's identification and came to a reasonable conclusion, based on the appearance, that it was valid. With a base score of 12 points for having a furnishing law, scores range from 0 (no law) to a maximum of 12 (law with no location exceptions and no affirmative defense for sellers). See Table 11 for Furnishing law scoring criteria and weights.

Age of Seller – On-premises Servers

State laws specify a minimum age for employees who serve or dispense alcoholic beverages in on-premise establishments. In some states, the minimum age for serving beer, wine, and/or spirits is 21; however, some states permit those younger than 21 to sell alcohol. Additionally, some states specify conditions that must be met if employees younger than 21 are permitted to serve, such as having a manager present. Scores range from 0 (law does not require age 21 for serving and the law does not provide for any conditions that must be met for underage youth to serve) to a maximum of 2 (law requires age 21 for serving at on-premise establishments). See Table 12 for Age of On-premise seller law scoring criteria.

Age of Seller – On-premise Bartenders

Similar to servers, state laws specify a minimum age for employees who dispense alcoholic beverages in on-premise establishments. In some states, the minimum age for bartending beer, wine, and/or spirits is 21; however, other states permit those younger than 21 to bartend. Additionally, some states specify conditions that must be met if employees younger than 21 are permitted to dispense alcohol, such as having a manager present. Scores range from 0 (law does not require minimum age of 21 for bartending and the law does not provide for any conditions that must be met for underage youth to bartend) to a maximum of 2 (law requires age 21 for bartending at on-premise establishments). See Table 13 for Age of On-premise bartender scoring criteria and weights.

Age of Seller – Off-premises

Again, similar to the on-premises laws, most states have laws that specify the ages at which employees may sell alcohol in off-premise establishments. As with laws regarding the minimum age for on-premise servers and sellers, some states require employees be age 21 to sell beer, wine, and/or spirits; those that allow minors to sell may require certain conditions to be satisfied. Scores range from 0 (law does not require minimum age of 21 to sell alcohol) to a maximum of 2 (21 minimum age to sell alcohol at off-premise establishments). See Table 14 for Age of Off-premise seller scoring criteria and weights.

Keg Registration

Keg registration laws require sellers to tag beer kegs and collect information on those who purchase them so that the purchaser can be tracked and sanctioned if underage drinkers are served alcohol from the keg. States were coded as having this law if they required wholesalers or retailers to attach an identification number to their kegs and collect identifying information from the keg purchaser. The State of Utah bans kegs altogether. For this study, Utah was coded as having a keg registration law, since banning kegs is considered a stronger method of keg regulation. Thus, for states that allow keg sales, scores range from 0 (no law) to 7 for most states (law prohibiting both unregistered/unlabeled kegs and destruction of the label on keg, requiring a deposit regardless of amount, requiring two additional pieces of information be collected from purchaser beyond name and address, requiring active warning to purchaser). Utah, which prohibits kegs altogether, received a maximum score of 8. See Table 15 for Keg Registration law scoring criteria and weights.

Beverage Service Training

Beverage service training and related practices establish requirements or incentives for retail alcohol outlets to participate in programs (often referred to as “responsible beverage service (RBS)” or “server training” programs) to (1) develop and implement policies and procedures for preventing alcohol sales and service to minors and intoxicated persons and (2) training managers and servers/clerks to implement policies and procedures effectively. Such programs may be mandatory or voluntary. In APIS, a program is considered to be mandatory if State provisions require at least one specified category of alcohol retail employees (e.g., clerks, managers, or owners) to attend training. States with voluntary programs offer incentives to licensees to participate in RBS training such as discounts on dram shop liability insurance and protection from license revocation for sales to minors or intoxicated persons. Scores primarily range from 0 (no RBS law) to 12 for most states (mandatory program requiring both managers and servers to be trained, covering both on- and off-premise outlets and both new and existing licensees). A few states have both a mandatory program and a voluntary program (booster sessions), so scores could be as high as a maximum of 21 if a state had both a strong mandatory program and a voluntary or booster program each of which included all four incentives. See Table 16 for Beverage Service Training law scoring criteria and weights.

False Identification – Retailer Support Provisions

Some States include provisions to assist retailers in avoiding sales to potential buyers who present false identification. An example would be distinctive driver’s licenses for persons under age 21 such as a portrait format for under 21 and a landscape format for those age 21 and over. Some states have provisions that allow offenders to enact an affirmative defense. This affirmative defense requires the offender to admit to violating the law, however, may also provide a defense by demonstrating mitigating circumstances which excuse or justify his/her behaviors. Scores range from 0 (no retailer support provisions for false ID) to a maximum of 5 (all provisions except general affirmative defense). See Table 17 for scoring criteria and weights for this law.

Hosting Underage Drinking Parties

Prohibitions against hosting underage drinking parties are laws that impose state penalties on individuals (social hosts) responsible for underage-drinking events on property they own, lease, or otherwise control. In a court case against a social host, the prosecution must present sufficient evidence to meet a knowledge standard to establish a violation. The more demanding the standard in terms of the evidence required, the lower the likelihood of a successful prosecution. These knowledge standards in descending order regarding evidence required include:

Overt Act - the host must have actual knowledge of specific aspects of the party, and must commit an act that contributes to its occurrence.

Knowledge - the host must have actual knowledge of specific aspects of the party; no action is required.

Recklessness - the host may not have acted with actual knowledge of the party, but must act with intentional disregard for the probable consequences of her or his actions.

Negligence - the host knew or should have known of the event's occurrence (in legal terminology, this is referred to as “constructive knowledge”).

In some jurisdictions, preventive action by the social host may negate state-imposed sanctions. A preventive action constitutes an affirmative defense or absence of preventive action as an element of the offense. An affirmative defense must be established by a defendant in order to avoid liability; an element of the offense is something the prosecution must prove in order to establish the defendant's guilt. Scores range from 0 (no law) to a maximum of 12 (general statute covering all underage actions, all property types, with negligence as the knowledge standard and no exceptions). See Table 18 for scoring criteria and weights for this law.

Dram Shop Liability

Dram shop liability is a private cause of action against a commercial alcohol provider (retailer) for injuries or damages caused by an intoxicated or underage patron. Note that the scoring applied to this policy topic is limited to laws allowing injured third parties to sue retailers for injuries caused by their underage patrons. The typical factual scenario is that a licensed retailer furnishes alcohol to a minor who, in turn, causes an alcohol-related motor vehicle collision that injures a third party. Although the state may impose separate penalties for violations of other underage drinking laws (such as furnishing laws), dram shop liability may only be imposed by injured third parties.

Dram shop liability is established by statute and/or by state court through common law. A designation of dram shop liability signifies that liability may be imposed for the negligent provision of alcohol to a minor arising under common law, statutory law, or both. Variables used in scoring statutory laws are limitations on when a third party may sue. These limits are separated into (1) those involving who may be sued (such as the type of retailer or servers over a certain age), and (2) requirements that additional facts or more rigorous evidentiary standards than those required under common law be met (such as proving the retailer knew the patron was underage or proving evidence “beyond a responsible doubt”). Limitations are significant only when liability is available solely under statutory law as they do not pertain to common law. And, when both are available, a plaintiff may choose to pursue legal action under either. Presumably, he or she will choose the legal option that will grant the greatest relief. With a base score 3 points allotted for having a dram shop liability law, scores can range from 0 (no law) to a maximum of 3 (common law, common law and statutory law, or statutory law with no limitations). See Table 19 for Dram Shop Liability law scoring criteria and weights.

Social Host Civil Liability

Social host civil liability refers to a private cause of action against a non-commercial alcohol provider (social host) for injuries or damages caused by an intoxicated or underage guest. Note that, as reported by SAMHSA (SAMHSA 2012) the scoring applied to this policy topic is limited to those laws allowing injured third parties to sue social hosts for injuries caused by their underage guests. The typical factual scenario is one in which a social host furnishes alcohol to a minor who, in turn, causes an alcohol-related motor vehicle collision that injures a third party. Although the state may impose separate penalties for violations of other underage drinking laws (such as hosting underage parties), social host civil liability may only be imposed by injured third parties.

Social host civil liability is established by statute and/or by state court through common law and may be imposed for the negligent provision of alcohol to a minor arising. Variables used in scoring statutory laws are limitations on when a third party may sue. These limits are separated into (1) those involving who may be sued (such as social hosts 21 and older only), and (2) requirements that additional facts or more rigorous evidentiary standards than those required under common law be met (such as proving the social host knew the guest was underage or proving evidence “beyond a responsible doubt”). Limitations are significant only when liability is available solely under statutory law as they do not pertain to common law. And, when both are available, a plaintiff may choose to pursue legal action under either. Presumably, he or she will choose the legal option that will grant the greatest relief. With a base score 3 points allotted for having a social host civil liability law, scores can range from 0 (no law) to a maximum of 3 (common law, common law and statutory law, or statutory law with no limitations). See Table 20 for scoring criteria and weights of Social Host Civil Liability laws.

Apply to Manufacturers of False Identification

False Identification: Provisions That Target Suppliers

In some States, it is illegal to produce false IDs and/or to lend/transfer/sell an ID to another person. Scores range from 0 (no law against providing false ID) to 1 (one action above prohibited) to a maximum of 2 (both actions— production and lend/transfer/sale prohibited). See Table 21 for False Identification laws applying to manufacturers scoring criteria and weights.

Apply to States Concerning Control of Alcohol Distribution

Alcohol Control Systems: Retail Distribution Systems

There are two types of retail alcohol distribution systems: license and control (APIS uses the term “State-run”). For each alcohol beverage type (beer, wine, distilled spirits), a state may use a state-run retail distribution system, a system of private licensed sellers, or some combination of these. Because the type of retail distribution may vary based on the alcohol content of an alcohol beverage, an index beverage has been used for scoring. The index beverage represents the beverage with the largest market share for its type: (1) beer with 5% alcohol by volume (ABV), (2) wine with 12% ABV, (3) spirits with 40% ABV. Scores range from 0 (no part of retail distribution system is state-run) to a maximum of 3 (state-run retail system for all three beverage types). See Table 22 for scoring criteria and weights of Alcohol Control System laws.

Analyses

First, a series of simple bivariate correlation analyses were conducted to examine how use/lose laws and zero tolerance laws were related to (1) underaged alcohol-related fatal crash ratios and (2) per capita beer consumption. Second, a series of multivariate analyses of variance were conducted to determine if states with stronger use/lose and zero tolerance laws (scored 0.50 law strength or greater) predicted lower underaged alcohol-related crash ratios and per capita beer consumption when compared to states with weaker laws (scored law strength .049 or less). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS v.21 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Note the wide variability of the scores for each law in Table 2 and in the number of states that have adopted the underage drinking laws. The number of states adopting each law ranged from only 9 states with Internal Possession laws to all states and DC adopting Possession, Fake ID Use, Zero Tolerance, Graduated Driver Licensing with Night Restrictions and Furnishing. Kentucky has adopted only 9 of the 20 underage drinking laws while Utah has adopted all 20 laws. The average standardized strength of the laws range from 0.09 for State Alcohol Control to 0.77 for Possession laws.

With regard to the analyses, for the Use/Lose laws, including the strengths of the law demonstrated a negative correlation (r=-.309; p<.001) with underaged alcohol-related crash ratios and a negative correlation (r=-.187, p<.001) with per capita beer consumption. When the strength of the laws were omitted, the Use/Lose law demonstrated a negative correlation (r=-.338; p<.001) with underaged alcohol-related crash ratios and was negatively correlated (r=-.124; p<.001) with per capita beer consumption. A one-way between-groups multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to investigate the differences in strongly scored laws to weakly scored laws on measures of underaged alcohol-related crash ratios and per capita beer consumption. There was a statistically significant difference between weak laws and strong laws on both the underaged alcohol-related crash ratios F(1, 1,579) = 106.77, p < .001, partial η2 = .063 and per capita beer consumption F(1, 1,579) = 72.13, p < .001, partial η2 = .044. An inspection of the mean scores indicated that stronger laws demonstrated slightly improved underaged alcohol-related crash ratios (M = 0.24, SD = .12) and per capita beer consumption (M = 1.22, SD = .19) when compared to weaker laws (M = 0.35, SD = .23 and M = 1.32, SD = .23 respectively).

For Zero Tolerance laws, the inclusion of the law strengths demonstrated a negative correlation for both underaged alcohol-related crash ratios (r=-.451; p<.001) and per capita beer consumption (r=-.238; p<.001). Similarly, there was a smaller, but still significant negative correlation between Zero Tolerance laws excluding the law strengths and both underaged alcohol-related crash ratios (r=-.395; p <.001) and per capita beer consumption (r=-.144; p <.001). As was done with the Use/Lose laws, a one-way between-groups MANOVA was performed to investigate the differences in strongly scored laws to weakly scored laws on measures of underaged alcohol-related crash ratios and per capita beer consumption. There was a statistically significant difference between weak laws and strong laws on both the underaged alcohol-related crash ratios F(1, 1,579) = 181.29, p < .001, partial η2 = .103 and per capita beer consumption F(1, 1,579) = 27.43, p < .001, partial η2 = .017. Again, an inspection of the mean scores indicated that stronger laws demonstrated slightly improved underage alcohol-related crash ratios (M = 0.24, SD = .15) and per capita beer consumption (M = 1.25, SD = .22) when compared to weaker laws (M = 0.38, SD = .23 and M = 1.32, SD = .23 respectively).

Discussion

There have been numerous underage drinking laws adopted in the United States in an effort to reduce the harm caused by the use and misuse of alcohol by persons under the age of 21. We have documented 20 such laws and provided scores based upon their strengths and weaknesses. Only 5 of the 20 MLDA-21 laws have been adopted by all states and DC. The Use & Lose law and the Zero Tolerance law have both been shown to be effective in reducing the underage drinking driver rate in fatal crashes by 5% each without using the strengths (Fell et al., 2009). While all states have a Zero Tolerance law, not all have adopted a Use/Loose law (only 39 states and DC have these laws). Similar to previous work examining these laws, our analyses of Use & Lose and Zero Tolerance laws and their strengths, found that states which had implemented these laws but had stronger scores also had significantly improved underage alcohol-related fatal crash ratios and per capita beer consumption when compared to states which had these laws, but had more exemptions giving them a weaker strength score. This demonstrates that though an absent/present representation of law implementation may yield useful information, the inclusion of the law strengths provides a more accurate understanding of the impact of laws on related outcomes.

As researchers, we should determine which laws have been effective and have met their intended purpose. The scoring of these 20 MLDA-21 laws should help prove or disprove our theoretical model stated earlier when comprehensive evaluations are conducted. Evaluations of these laws without considering their strengths and weaknesses may result in misleading findings.

With respect to underage drinking laws, there is substantial variation in the completeness with which states have adopted all components of these laws and the strength of the adopted provisions in terms of coverage, sanctions, exceptions and enforcement. Additional research is necessary to determine how each law may affect underage alcohol consumption and resulting harm given various environmental, cultural and demographic variables. The intent of the current article is to provide a valuable tool for researchers to examine which types of underage drinking laws are the most effective and guidance for state policymakers regarding how states may improve their existing laws to reduce drinking and the consequences of drinking among underage 21 individuals. By assessing and coding the strengths of laws, future analyses will more accurately evaluate their effect. Public health officials and policymakers can then make informed decisions on recommending and introducing legislation that can potentially save lives and reduce injuries.

Limitations

It should be noted that scores are not comparable across policy topics, only across states within a policy topic. For example, a score of “8” in Table 2 (e.g., Alaska’s possession law) does not mean that the law is 4 times stronger than a score of “2” for another law (e.g. Alabama's fake identification use law). The individual scores only represent relative strengths of that individual law compared to the strength of that same law in other states. We recommend standardizing these scores when researchers are conducting evaluations of more than one law.

In general, many factors affect the policy environment in any state including the level of enforcement and the publicity given to laws. We do not have good measures of either of these factors on a state-by-state basis. However, in our studies of the effects of these underage drinking laws, we typically use impaired driving laws (BAC limits, license suspension), other traffic safety laws (primary seat belt use laws), vehicle miles travelled, beer consumption, and economic strength (unemployment rates) as control variables or covariates.

It is possible that some readers and/or researchers may not agree with our scoring of any particular law. While our criteria for scoring have an empirical basis, our individual scores may be considered arbitrary. We did not conduct a sensitivity analysis, but we did see a correlation of state laws with high scores and reductions in underage drinking drivers fatal crash rates.

Acknowledgements

The research for this article and the preparation of this manuscript were conducted under a grant from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R21 AA019539) and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2012-AH-FX-0005).

Appendix A

Expert Panel Used in Scoring 20 MLDA-21 Laws

Legal Researchers

Sue Thomas, Ph.D.

Dr. Thomas is an expert in research that melds legal data for social science research studies. She has served on the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism's (NIAAA) Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) project since its inception in 2001, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA) Report to Congress on the Prevention and Reduction of Underage Drinking since its inception in 2010; both of which develop databases of legal data on alcohol statutes and regulations. Additionally, she has, with colleagues, developed several other databases of legal data on state alcohol laws, DUI-child endangerment laws, and city-level data on municipal alcohol ordinances. She has received two grants for alcoholpolicy research, one from NIAAA and one from the The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. She has also co-authored several publications pertaining to measuring law for social science research, and has published articles on alcohol policy.

Ryan Treffers, JJ.D

Mr. Treffers is an expert in research that melds legal data for social science research studies and his current work involves legal research on the intersection of public health and law. His work in the specific area of alcohol policy includes the Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS), the STOP Act, a National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Prevention Research Center Grant city-ordinance study, and a Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (Calverton Center) Child Endangerment and Traffic Safety project; both of which focus on the definitions, collections, and analysis of legal data, including effective dates, for social science purposes. He is a trained legal researcher experienced in working with all levels of government regulation, including federal and state statutes and regulations, as well as local ordinances.

Research Psychologist

Robert B. Voas, Ph.D.

Dr. Voas has been involved in research on alcohol and highway safety for 30 years, initially as director of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's Office of Program Evaluation and more recently as Principal Investigator for government research programs in drinking-driving and community alcohol problem prevention. Dr. Voas is a Fellow of the American Psychological Association and a Past President of the International Council on Alcohol, Drugs, and Traffic Safety. He is also a member of the Committee on Alcohol and Drugs, the National Safety Council, and the Committee on Alcohol and Other Drugs of the National Transportation Research Board and has served on the National Board of Mothers Against Drunk Driving. His recent research projects have included an evaluation of programs to reduce college student binge drinking, studies of underage binge drinkers crossing the border at San Diego and El Paso to drink in Mexico, where the drinking age is 18, and a national study of the impact of alcohol safety laws on alcohol-related fatal crashes, using the FARS.

Senior Statistician

A. Scott Tippetts, M.A.

Mr. Tippetts has served as the primary data analyst for more than 100 research projects in the fields of Alcohol & Drug Issues, and Traffic Safety Programs. These projects included evaluations of public policies and legislation, evaluations of private and public programs, assessment of technical equipment (accuracy, reliability), and general behavioral research (experimental, actuarial, survey, observational, and computer simulations). Additionally, he periodically performs consulting work for a broad range of academic researchers and program/process evaluators, including: health insurance companies, disease biologists, toxicologists, geneticists, epidemiologists, criminology researchers in the federal law enforcement and intelligence communities, mental health counselors treating post-traumatic stress disorder victims, and political activist groups. Over the past decade, Mr. Tippetts has served as regional director or coordinator for various public advocacy organizations, in which he has authored and produced public information materials, position papers, newspaper editorials, and lobbyist briefs for use by U.S. Congressional offices, and has served as Maryland State Coordinator for lobbying delegations.

Clinical Psychologist

Michael Scherer, Ph.D.

Dr. Michael Scherer has served as statistical consultant at Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation since May 2012. In that time he has been responsible for the preparation of articles for peer-reviewed journals, conducting simple and advanced descriptive and inferential data analyses, and managing data. He is familiar with the statistical analysis software SPSS, SAS, and M-Plus. Statistical analyses he has conducted for PIRE include, but are not limited to, Structural Equation Modeling, Hierarchical Linear Modeling, Latent Class Analysis, Multilevel Modeling, Confirmatory and Exploratory Factor Analysis, Multivariate Regression Analysis, and Analysis of Variance and Covariance. Additionally, he has relevant experience constructing comprehensive literature reviews using specific selection criteria in his previous work on other grants (e.g., NIAAA R21 AA022171).

Social Psychologist

Deborah Fisher, Ph.D.

Dr. Deborah Fisher has a background in social psychology, with broad interests and research experience in public health and traffic safety issues, particularly impaired driving. She has been actively involved in studies that have evaluated changes in alcohol-involved crash rates in relation to the intensity of impaired driving enforcement, community interventions to prevent overservice to youth at drinking establishments, and the presence and strength of provisions in minimum legal drinking age and related laws.

Human Factors Engineer

James C. Fell, M.S.

Mr. Fell is a senior research scientist with the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (PIRE) in Calverton, MD. He is currently working on three grants from the NIAAA studying the effects of various underage drinking laws on underage drinking and driving fatal crashes, the length of administrative license suspension on impaired driving recidivism, and a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of lowering blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limits for driving to .08 and to .05. Mr. Fell formerly worked at NHTSA from 1969 to 1999 and has 47 years of traffic safety and alcohol research experience. He has both a Bachelor's and Master's degree in Human Factors Engineering from the State University of New York at Buffalo. He received the Widmark Award from ICADTS in 2013 for outstanding, sustained and meritorious contribution to the field of alcohol, drugs and traffic safety.

Appendix B

Table 3.

Law Strength Scoring Criteria for Possession Law

| Scoring Criteria | Weight Point Values |

|---|---|

| Law present | + 11.0 points |

| Any private location exception | - 6.0 points for unconditional - 3.0 points for conditional |

| Any private residence exception | - 4.0 points for unconditional - 2.0 points for conditional |

| Parent/guardian home only exception | - 2.0 points for unconditional - 1.0 point for conditional |

| Parent and/or spousal exception not conditional on location exception | - 4.0 points |

Table 4.

Law Strength Scoring Criteria for Purchase Law

| Scoring Criteria | Weight Point Values |

|---|---|

| Law present | +1.0 point |

| Provision for youth to purchase alcohol for law enforcement purposes | +1.0 point |

Table 5.

Law Strength Scoring Criteria for Consumption Law

| Law present | +11.0 points |

| Any private location exception | - 6.0 points for unconditional - 3.0 points for conditional |

| Any private residence exception | - 4.0 points for unconditional - 2.0 points for conditional |

| Parent/guardian home only exception | - 2.0 points for unconditional - 1.0 point for conditional |

| Parent and/or spousal exception not conditional on location exception | - 4.0 points |

Table 6.

Law Strength Scoring Criteria for Internal Possession Law

| Scoring Criteria | Weight Point Values |

|---|---|

| Law present | +11.0 points |

| Any private location exception | - 6.0 points for unconditional - 3.0 points for conditional |

| Any private residence exception | - 4.0 points for unconditional - 2.0 points for conditional |

| Parent/guardian home only exception | - 2.0 points for unconditional - 1.0 point for conditional |

| Parent and/or spousal exception not conditional on location exception | - 4.0 points |

Table 7.

Law Strength Scoring Criteria for Use and Lose: Driving Privileges Law

| Scoring Criteria | Weight Point Values |

|---|---|

| License sanction applicable to underage purchase | + 2.0 points if mandatory + 1.0 point if discretionary |

| License sanction applicable to underage possession | + 2.0 points if mandatory + 1.0 point if discretionary |

| License sanction applicable to underage consumption | + 2.0 points if mandatory + 1.0 point if discretionary |

| Upper age limit less than 21 years | - 1.0 point |

| Minimum length of criminal license sanction | + 0.0 points for 30 days and less +1.0 point for 31 to 90 days + 2.0 points for 91 days or longer |

Table 8.

Law Strength Scoring Criteria for False Identification Law: Provisions that Target Minors

| Scoring Criteria | Weight Point Values |

|---|---|

| Law present | +1.0 point |

| Law sanction procedures | +2.0 administrative or both administrative and judicial sanctions |

| OR | |

| +1.0 for judicial only |

Table 9.

Law Strength Scoring Criteria for Zero Tolerance Law

| Scoring Criteria | Weight Point Values |

|---|---|

| Administrative license sanction | +4.0 points if mandatory +2.0 points if discretionary |

| Minimum length of administrative license sanction | + 0.0 points for 30 days and less +1.0 point for 31 to 90 days + 2.0 points for 91 days or longer |

| Criminal license sanction | +2.0 points if mandatory +1.0 point if discretionary |

| Minimum length of criminal license sanction | + 0.0 points for 30 days and less +1.0 point for 31 to 90 days + 2.0 points for 91 days or longer |

Table 10.

Law Strength Scoring Criteria for Graduated Driver's License with Nighttime Restrictions

| Scoring Criteria | Weight Point Values |

|---|---|

| Start time of nighttime driving restriction | + 3.0 points for 10pm or earlier + 2.0 points for 10:01 pm to midnight + 1.0 point for later than midnight |

Table 11.

Law Strength Scoring Criteria for Furnishing Laws

| Scoring Criteria | Weight Point Values |

|---|---|