Abstract

Background

Mismatch negativity (MMN) and visual P1 event-related potentials (ERPs) are established markers of impaired auditory and visual sensory dysfunction in schizophrenia, respectively. Differential relationships of these measures with premorbid and present function and with clinical course have been noted in independent cohorts, but measures have not been compared previously within the same patient group.

Methods

26 patients with schizophrenia and 19 controls participated in a simultaneous visual and auditory ERPs experiment. Attended visual ERPs were obtained to low- and high-spatial frequency stimuli. Simultaneously, MMN was obtained to unattended pitch, duration and intensity deviant stimuli. Permorbid function, symptom and global outcome measures were obtained as correlational measures.

Results

Patients showed substantial P1 reductions to low-, but not high- SF stimuli, unrelated to visual acuity. Patients also exhibited reduced MMN to all deviant types. No significant correlations were observed between visual ERPs and either premorbid or global outcome measures or with illness duration. In contrast, MMN amplitude correlated significantly and independently with premorbid educational achievement, cognitive symptoms and global function, as well as duration of illness. MMN to duration vs. other deviants was differentially reduced in individuals with poor premorbid function.

Conclusion

Visual and auditory ERP measures were differentially related to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Visual deficits correlated poorly with both functional measures and illness duration, and so may be viewed best as trait vulnerability markers. Deficits in MMN are independently related to premorbid function and illness duration, suggesting independent neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative contributions. Findings suggest that different underlying pathophysiological mechanisms may account for impaired visual and auditory neurophysiological dysfunction in schizophrenia.

Introduction

Cognitive deficits represent a core feature of schizophrenia and involve early sensory, as well as higher cortical, dysfunction. In the auditory system, deficits are observed both in behavioral tasks, such as ability to match tones following brief delay (1, 2), and in the generation of auditory event-related potentials (ERP), such as mismatch negativity (MMN) (3–5) . In the visual system, deficits are reflected particularly in activity of the magnocellular visual system, one of the two subcortical systems, which is generally associated with depth and motion perception (6). Both auditory and visual findings have been observed consistently in schizophrenia across patient samples, and have been reported to show differential association with demographic and clinical patient characteristics (7). To date, however, the two sets of deficits have yet to be studied within the same patient sample, leaving open the interrelationship between measures. In the present study, auditory and visual ERP deficits were assessed simultaneously in a group of chronic, stabilized individuals with schizophrenia vs. controls. Relative relationships with symptoms, premorbid function, and functional outcome were also assessed.

MMN is elicited in the context of the auditory oddball paradigm, in which sequences of repetitive auditory stimuli are interrupted infrequently by physically deviant oddball stimuli (8). Deviants may differ from standards in any (9)of a range of physical features including pitch, duration, location or intensity, as well as abstract physical changes, such as rule violations (10, 11). Deficits in MMN generation in schizophrenia were first demonstrated almost 20 years ago for duration (4) and pitch (3) deviant stimuli. Findings have been extensively replicated since that time (7, 12, 13) and linked to structural (14–16) and functional (17, 18) impairment within auditory sensory cortex . In addition, deficits have been linked to impaired tone matching ability (19–21), which, in turn, correlates with impairments in processes such as auditory emotion recognition (28, 29) or attentional allocation (29, 30). Correlations with persistent negative and cognitive symptoms (12, 22–24) in schizophrenia, and impaired social and global function in both schizophrenia patients (25, 26) and normal controls (27) have also been reported. Thus, MMN appears to index neural processes critical for psychosocial success across diagnostic groups.

MMN deficits are variably observed in unaffected family members of schizophrenia probands (31–35) and were at one time thought to develop only following illness onset (14, 15, 34). Most recently, however, deficits have been reported in individuals at symptomatic high risk (36, 37). Further, duration MMN has been found to predict conversion to psychosis (38). These findings suggest that the deficits are present premorbidly in at least a subset of patients. We have also observed that in first episode subjects, MMN amplitudes are not reduced in the group as a whole, but are reduced in a specific subgroup with poor premorbid function as reflected in premorbid educational achievement (39). The present study further investigates this finding. In addition, we used an optimized design including several deviants, as has also been employed by other groups in schizophrenia research (40). Therefore, we were able to explore the relative deficits in the MMN to different types of deviants.

Deficits in early visual processing have also become increasingly well-documented over the past decade (41–44). By comparison to MMN, deficits in early visual processing have been observed in unaffected family members of schizophrenia probands (45). Furthermore, within schizophrenia, deficits are not highly linked to symptoms or global outcome, although they are related to specific impairments in more complex forms of cognitive processing including stimulus encoding, perceptual closure (46), reading (47), and face emotion recognition (48). Visual ERPs have yet to be studied relative to premorbid function, leaving open the relative sensitivity of these measures to demographic and clinical characteristics that have been linked to impaired MMN generation.

Despite the extensive literature on MMN and visual ERP deficits individually, no studies have yet obtained both measures within the same patient samples. The present study investigates both MMN and visual ERPs relative to measures of premorbid and present functioning (39). Present function was assessed using symptom ratings, Global Assessment of Function (GAF) and the Independent Living Scale (ILS), a problem solving measure that serves as a proxy measure for “functionally meaningful” cognition in schizophrenia (49, 50). A multivariate regression approach was used to investigate relative contributions of premorbid, clinical and demographic factors to impaired sensory ERP generation.

We hypothesized that both auditory and visual ERPs would be impaired in schizophrenia patients relative to controls, but that associations with both premorbid and present functioning would differ. Specifically, within auditory measures, we predicted associations not only to premorbid function but also to illness duration and global outcome. In contrast, we predicted that such associations would be absent for visual measures, suggesting differential contribution to disease etiopathogenesis, and hence different utility in the diagnosis, management and etiological investigation of schizophrenia.

Methods and Materials

Participants

Participants were recruited from inpatient and chronic residential care settings associated with the Nathan Kline Institute (Orangeburg, New York) and from community and staff volunteers. Informed consent was obtained from 26 patients diagnosed with either schizophrenia (n=14) or schizoaffective disorder (n=12) and 19 controls (Table 1). Individuals with organic brain disorders, mental retardation, past drug or alcohol dependence, current drug or alcohol abuse or hearing/vision impairments were excluded. All procedures were approved by the Nathan Kline Institute Institutional Review Board. All subjects provided written informed consent. Subjects were corrected to near-normal visual (20/32 or better) prior to participation.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Patients and Controls

| Characteristic | Mean, SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Controls | Patients | |

| Age | 35.8 ± 9.9 | 36.0 ± 10.5 |

| Gender (M/F) | 16/3 | 25/1 |

| Parental socioeconomic status (SES) | 42.2 ± 12.8 | 42.8 ± 18.8 |

| Education | 16.1 ± 2.8 | 12.5 ± 2.2* |

| Individual SES | 46.8 ± 13.8 | 27.2 ± 10.0* |

| Visual Acuity, Near | 0.96 ± 0.1 | 0.98 ± 0.1 |

| Visual Acuity, Far | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.99 ± 0.2 |

| PANSS-positive | ---- | 10.6 ± 2.8 |

| PANSS-negative | ---- | 14.8 ± 4.5 |

| PANSS-cognitive | ---- | 11.5 ± 3.2 |

| Independent Living Scale (ILS-PB) | ---- | 38.3 ± 12.1 |

| GAF | ---- | 41.4 ± 7.6 |

p<.001

Procedure

ERPs were collected in a single session. Auditory stimuli were presented passively though headphones and consisted of a sequence of four complex tones (1 standard tone and duration, intensity, and frequency deviants) presented in random order at SOAs of 500–505 ms. The standard stimulus (70% sequential probability) was a harmonic tone composed of three superimposed sinusoids (500, 1000, and 1500 Hz) as suggested by (51) to maximize MMN amplitude, and was 100 ms in duration, approximately 85 dB, and with 5 ms rise and fall time. Duration, pitch and intensity deviants (10% probability each) were 150 ms in length, 10% lower in pitch, of 10 dB lower in intensity, respectively, relative to standards, each presented with sequential probability of 10%. At the beginning of each run, the first 15 auditory stimuli were standards.

During auditory stimulus presentation, subjects were asked to attend to a sequence of visual stimuli and to mouse-press in response to a pre-designated target stimulus (a schematic picture of an animal) that occurred on 11% of trials while ignoring all other stimuli. A distractor animal (an animal that resembled the target animal) appeared on another 11% of the trials. Additional visual stimuli consisted of high (HSF, 5 cycles/degree) and low (LSF, 1 cycle/degree) spatial frequency, 100% contrast horizontal gratings (39% sequential probability each). At a viewing distance of 114 cm, the stimulus field subtended 6.1 · 4.6 degrees of visual angle. All stimuli were presented centrally against a 50% gray background that was isoluminant with the mean luminance of the sinewave gratings, which had a light/dark contrast of 80%. The stimulus onset asynchronies were 875 ms ± 25 ms. Sequences were timed to prevent stimulus overlap. Auditory and visual stimuli were presented simultaneously in 250 s blocks, with brief pauses in between.

Eight blocks were collected per participant.

Data acquisition

Continuous EEG data, along with digital timing tags for both auditory and visual stimuli, were acquired using a 168-channel BioSemi Active II system (BioSemi, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) with custom, evenly spaced electrodes on a cap using standard reference and ground procedures (http://www.biosemi.com/faq/cms&drl.htm). Data were filtered with a zero-phase shift 40 Hz low-pass filter (12 dB/octave). No highpass filter was applied. Epochs (−100 to 750 ms) were created off-line and were baseline-corrected from 80 ms pre-stimulus to 20 ms post-stimulus onset and artifact-rejected at ± 100 µV. Epochs were then averaged off-line for each participant for each stimulus type. MMN was defined from deviant minus standard difference waves. Similar numbers of sweeps were included in patient and control averages (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean Number of Accepted Sweeps

| Mismatch Negativity | ||

| Deviant Type |

Controls (n=19) Mean ± SD |

Patients (n=26) Mean ± SD |

| Duration | 367.3± 59.3 | 333.2± 51.6 |

| Frequency | 361.6 ± 59.5 | 329.0 ± 49.4 |

| Intensity | 361.9 ± 58.8 | 329.3 ± 48.3 |

| Standard | 1087.6 ± 177.4 | 987.8 ± 151.9 |

| Visual Measures | ||

|

High Spatial Frequency |

771.2 ± 119.5 | 700.4 ± 111.9 |

|

Low Spatial Frequency |

775.8 ± 118.7 | 696.4 ± 114.5 |

ERP Components

Auditory components of interest consisted of MMN to the three deviant types. The latency ranges for the duration, intensity, and frequency deviants were 200–250 ms post-stimulus onset, 140–200 ms, and 100–190 ms, respectively. Amplitudes were measured at frontocentral electrodes relative to average mastoids. Visual components were measured relative to nose reference and consisted of early (90–125 ms) and late (125–160 ms) P1 to LSF stimuli, and C1 (90 – 125 ms) and P1 (125 – 160 ms) to HSF. The electrodes for each component were chosen based upon visual inspection of the data and published distributions of auditory and visual ERPs (44, 52). For each component, the primary dependent measures were amplitude and latency within pre-specified latency ranges. Amplitudes were determined as peaks within each specified latency window.

Clinical measures

Symptoms were analyzed using a 5-factor model (53). Current functional level was assessed using the GAF (9) and ILS problem solving scale (54). Premorbid function was assessed by dividing subjects into poor (12 or fewer years of education) and good (more than 12 years of education) premorbid groups (5). Clinical measures were evaluated by centrally trained and certified raters with interrater reliability maintained at ≥.8).

Statistical analysis

Separate repeated measures multivariate analyses of variance (rmMANOVAs) were conducted for amplitude and latency of identified components. For MMN, deviant type (pitch/duration/intensity) was included as a within-subjects factor. For the visual P1, latency range and hemisphere were included as within-subjects factors. For C1, only a single latency range was used. Since it was a midline component, hemisphere was not included as a factor. For visual components, visual acuity was included as a covariate. Split-half reliability was computed for key measures using Cronbach’s alpha across the 8 separate acquisition runs.

Relationship of ERP amplitudes to clinical measures was assessed using multivariate regression vs. indicated measures. For regressions across group, a stepwise approach was used with group entered at step 1 and additional variables (e.g. MMN, P1) entered at subsequent steps. Overall regression significance was assessed based upon multivariate regression coefficient (R) values, while significance of individual variables was evaluated based upon partial correlation taking into account group membership. Correlations were analyzed hierarchically in that multivariate regressions were performed first, and individual correlations were reported only if the multivariate regression showed significance. Correlations with symptoms, medication, and functional outcome were based upon uncorrected Pearson correlations and were considered exploratory.

Results

Auditory Analyses

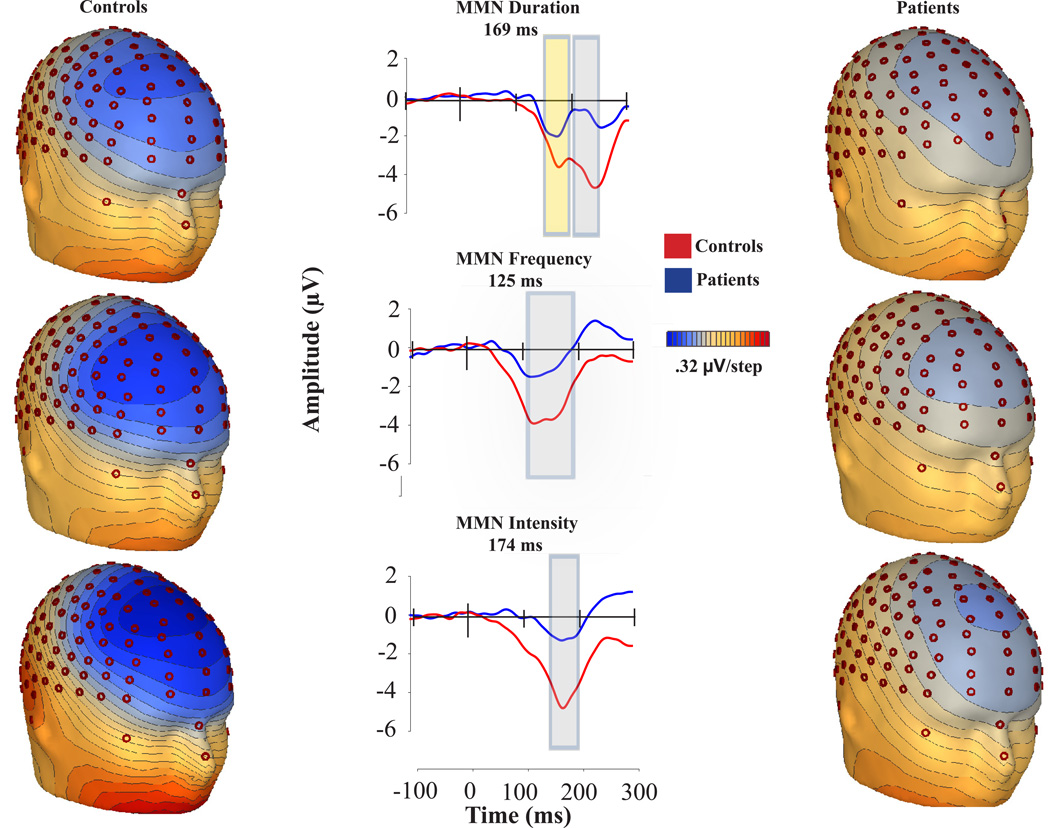

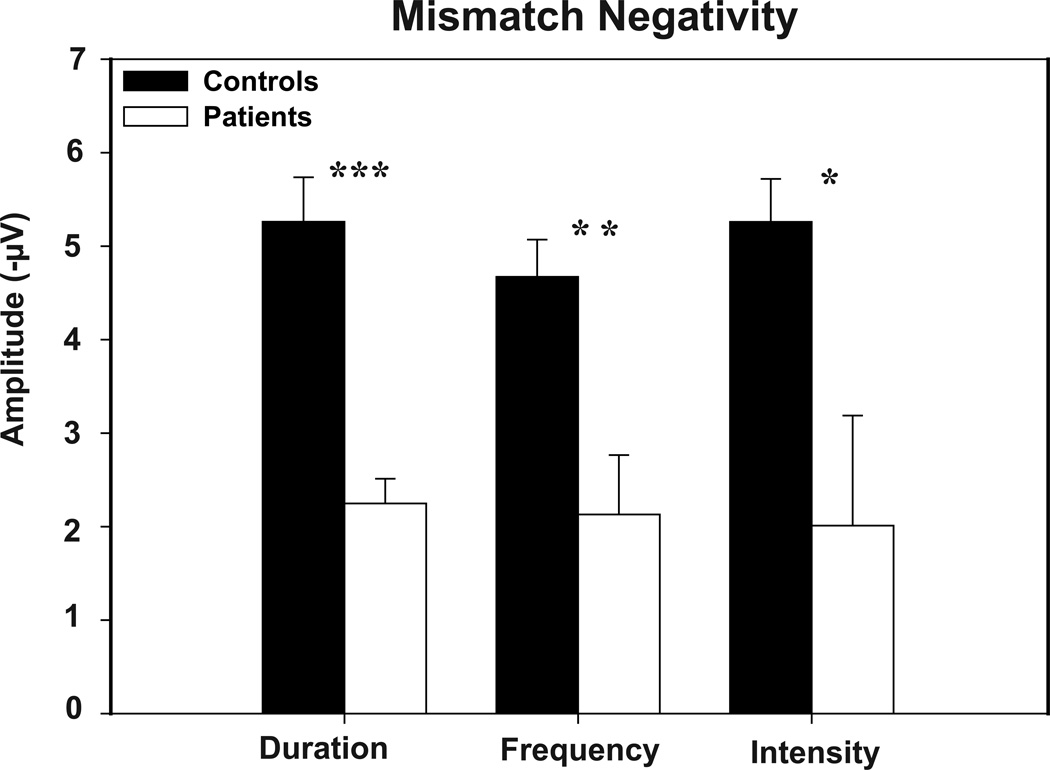

MMN showed a typical distribution, with peak amplitude at frontocentral electrodes across groups and conditions (Figure 1). Patients showed a highly significant reduction in MMN amplitude relative to controls across all deviants (F(1,43)=14.2, p<.0001), with no significant deviant-type X group interaction (F(2,42)=1.04, p=.36). Moreover, deficits were significant for each deviant type considered individually (Figure 2). Effect size of reduction was somewhat larger for duration (d=1.29) and pitch (d=1.17) than intensity (d=.77) deviants. Split-half reliability across the 8 acquisition runs was similar across deviant types (.92, .90 and .91 for duration, pitch and intensity, respectively).

Figure 1.

Voltage topography maps and group-averaged MMN waveforms for controls and patients. High-density electrodes were selected from the vicinity of Fz, FCz, and Cz.

Figure 2.

Patients’ v. controls’ MMN amplitudes in response to duration, frequency, and intensity deviants. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for patients and controls.

* p <.05, ** p <.005, *** p<.0001

Average MMN latency was comparable between groups (F(1,43)= 2.24; p= 0.14) for each deviant type (Table 3). For duration deviants, an early MMN component was also observed. Both the amplitude (−2.54 and −4.09 µV for patients and controls, respectively) and the latency (171.67 and 180.19 ms from stimulus onset for patients and controls, respectively) were significantly different across groups. (t=3.83, p<.0001 and t= −2.21, p=.03, respectively)

Table 3.

Latencies of Patients and Controls

| Mismatch Negativity | |||

| Deviant Type |

Controls (n=19) Mean ± SD (ms) |

Patients (n=26) Mean ± SD (ms) |

|

| Duration | 237.3 ± 13.5 | 233.8 ± 16.8 | |

| Frequency | 144.3 ± 23.6 | 133.8± 25.7 | |

| Intensity | 175.4 ± 12.4 | 172.9 ± 16.3 | |

| Visual Measures | |||

|

Spatial Frequency |

Component | ||

| High | C1 | 105.9 ± 9.8 | 111.1 ± 7.4* |

| Late P1 | 152.5 ± 7.1 | 151.9 ± 10.2 | |

| Low | Early P1 | 103.1 ± 2.8 | 104.4 ± 2.4 |

| Late P1 | 146.1 ± 9.3 | 148.05 ± 11.5 | |

| N1 | 189.7 ± 7.5 | 188.7 ±10.6 | |

p=.05

Visual ERPs

Low spatial frequency (LSF)

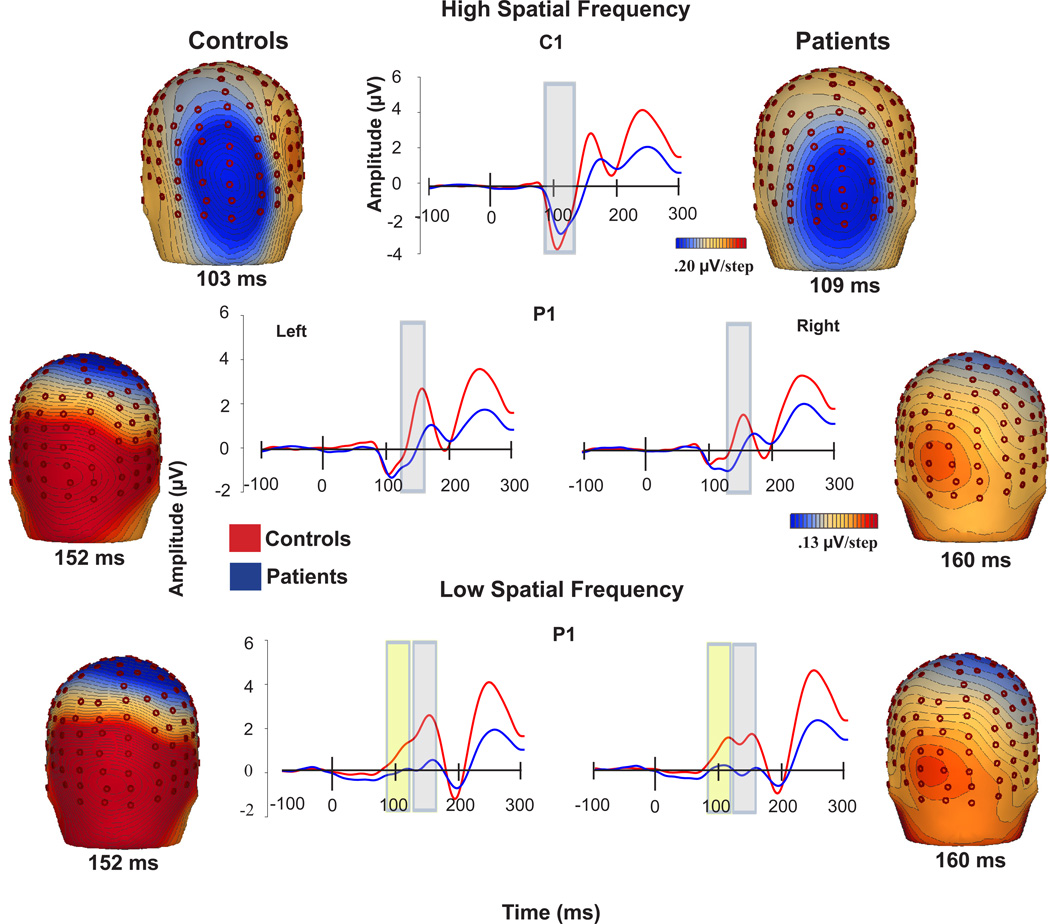

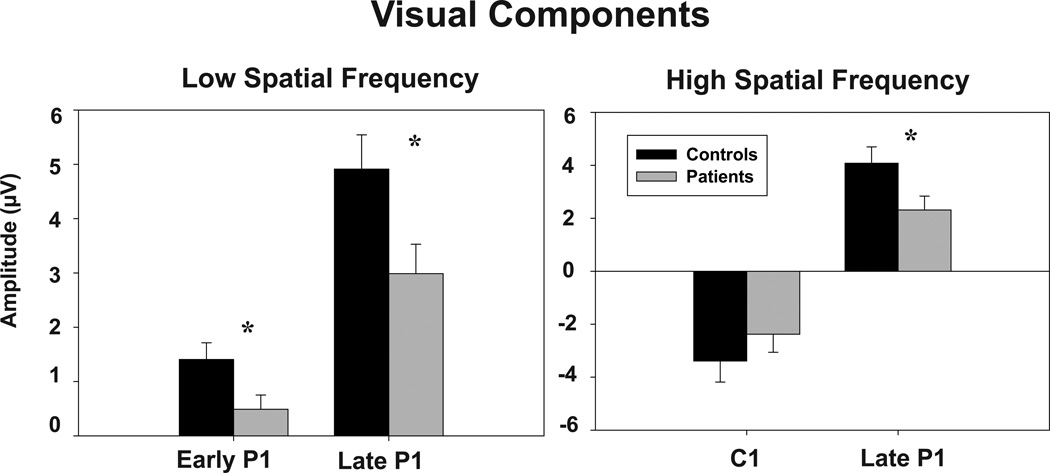

LSF responses consisted of bilateral dorsal early and late P1 components (Figure 3). P1 was significantly reduced in patients across both early and late latency ranges (F(1,43)=7.19, p=.01) (Figure 4). Differences remained strongly significant following covariation for visual acuity (F(1,39)=7.62, p=.009). There were no significant main effects of hemisphere (F(1,43)=.88, p=.35), group X hemisphere (F(1,43)=.11, p=.7) or group X latency range (F(1,43)=1.73, p=.2) interactions (Table 3). Split half reliability for P1 across runs was .91.

Figure 3.

Voltage topography maps and group-averaged waveforms of responses of controls and patients to low and high spatial and frequency gratings. High-density electrodes were selected from the vicinity of PO3, PO7, P5, and PO9 for the waveforms for the left hemisphere P1 and from PO4, PO8, P6, and PO10 for the right hemisphere P1.

Figure 4.

Patients’ v. controls’ amplitudes in response to low spatial frequency and high spatial frequency stimuli. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for patients and controls.

* p <.05

P1 latency was similar across groups (F(1,43)= 0.13 p=0.7) (Table 3). There was a significant main effect for hemisphere (F(1,43)= 10.03; p=.003). The hemisphere x group interaction was not significant (F(1,43)= 1.18; p=.28).

High Spatial Frequency (HSF)

As expected, C1 amplitude was comparable between groups (F(1,43) = 0.93; p =0.34). P1 amplitude was significantly reduced before covariation for visual acuity (F(1,43)=4.75, p=.035) (Figure 4), but not significant following covariation (F(1,40)=4.04, p=.088). There was a significant main effect of hemisphere (F(1,43)=18.9, p<.001), but no significant group X hemisphere interaction (F(1,43)=1.41, p=.24). C1 latency was marginally significant between groups (F(1,43)=4.05, p=.05), but became non-significant following covariation for visual acuity (F(1,39)=2.90, p=.1) P1 latency to HSF stimuli was not significantly different between groups (F(1,43)= .04; p=.84) (Table 3).

Premorbid function

Premorbid function was characterized based upon educational achievement. Patients as a group showed significantly lower educational achievement (t=5.35, p<.001) and individual SES (t=6.17, p<.001) than controls despite similar parental SES (t=.65, p=.6) (Table 1). Patients who did not progress beyond high school were otherwise demographically and symptomatically similar to those who did, although medication doses were much higher among patients with poor premorbid function (Table 4).

Table 4.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Poor vs. Good Premorbid Patients

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Premorbid | Good Premorbid | |

| Age | 34.5 ± 11.2 | 38.3 ± 9.3 |

| Gender (M/F) | 16/0 | 9/1 |

| Parental socioeconomic status (SES) | 39.6 ± 21.1 | 49.4 ± 11.7 |

| Education (yrs) | 11 ± 1.2 | 14.8 ± 1.3* |

| Individual SES | 21.9 ± 7.6 | 35.2 ± 7.8* |

| Age at first hospitalization (yrs) | 18.3 ± 4.4 | 22.3 ± 5.7 |

| Time: end of education to onset (yrs) | 1.3 ± 4.7 | 2.6 ± 4.4 |

| Duration of illness (yrs) | 16.3 ± 9.6 | 15.2 ± 9.1 |

| PANSS-positive | 11.6 ± 2.3 | 9.3 ± 3.4 |

| PANSS-negative | 15.6 ± 4.7 | 13.7 ± 4.6 |

| PANSS-cognitive | 11.4 ± 2.9 | 10.8 ± 2.4 |

| Independent Living Scale (ILS-PB) | 36.6 ± 11.6 | 43.0 ± 11.6 |

| GAF | 37.9 ± 5.7 | 46.8 ± 7.7* |

| Medication dose (mg CPZ equiv) | 1426.2 ± 965.9 | 527.4 ± 354.6* |

p<.05. Patients were included in the “poor premorbid” group if they completed 12th grade or below and in the “good premorbid” group if they completed any education beyond 12th grade.

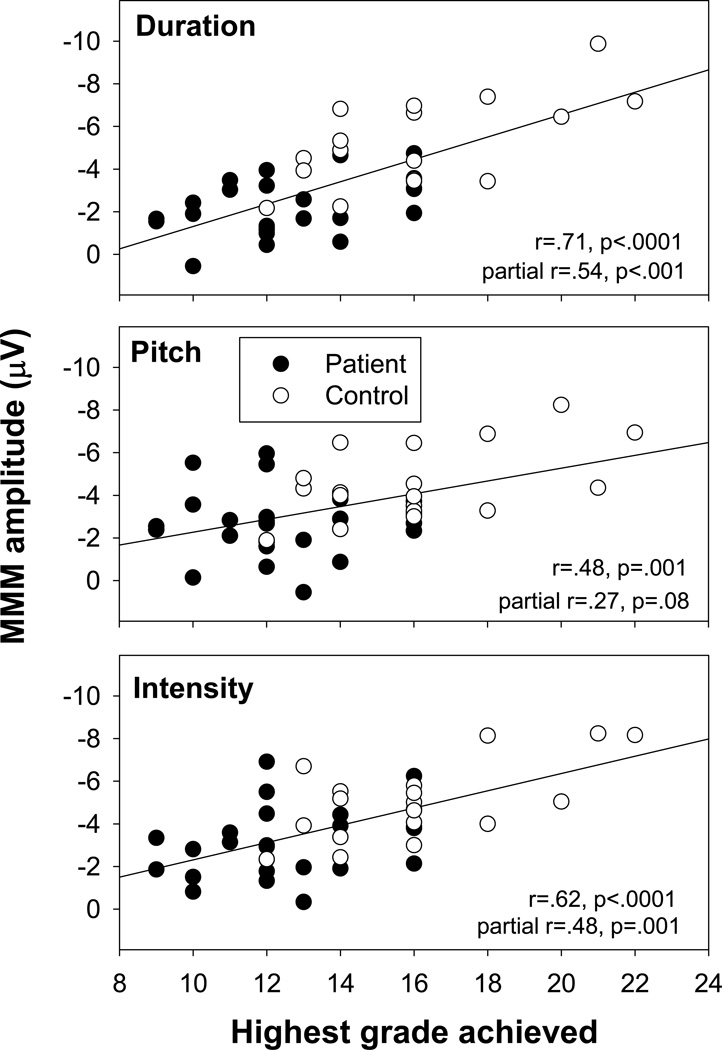

For both groups, the time between end of formal education and first hospitalization was similar and >2 yrs, suggesting that education was not interrupted by overt symptom onset, but may have been influenced by prodromal symptomatology. MMN amplitudes correlated significantly and strongly with premorbid educational achievement (r=.73, p<.0001) (Figure 5). This correlation remained strongly significant in a MANCOVA incorporating group as well as premorbid function (F(3,37)=5.79, p=.002). Furthermore, the group X premorbid function interaction was non-significant (F(3,37)=.78, p=.5), suggesting similar relationship across groups.

Figure 5.

Correlations between MMN amplitudes to each deviant type and premorbid educational status in patients and controls.

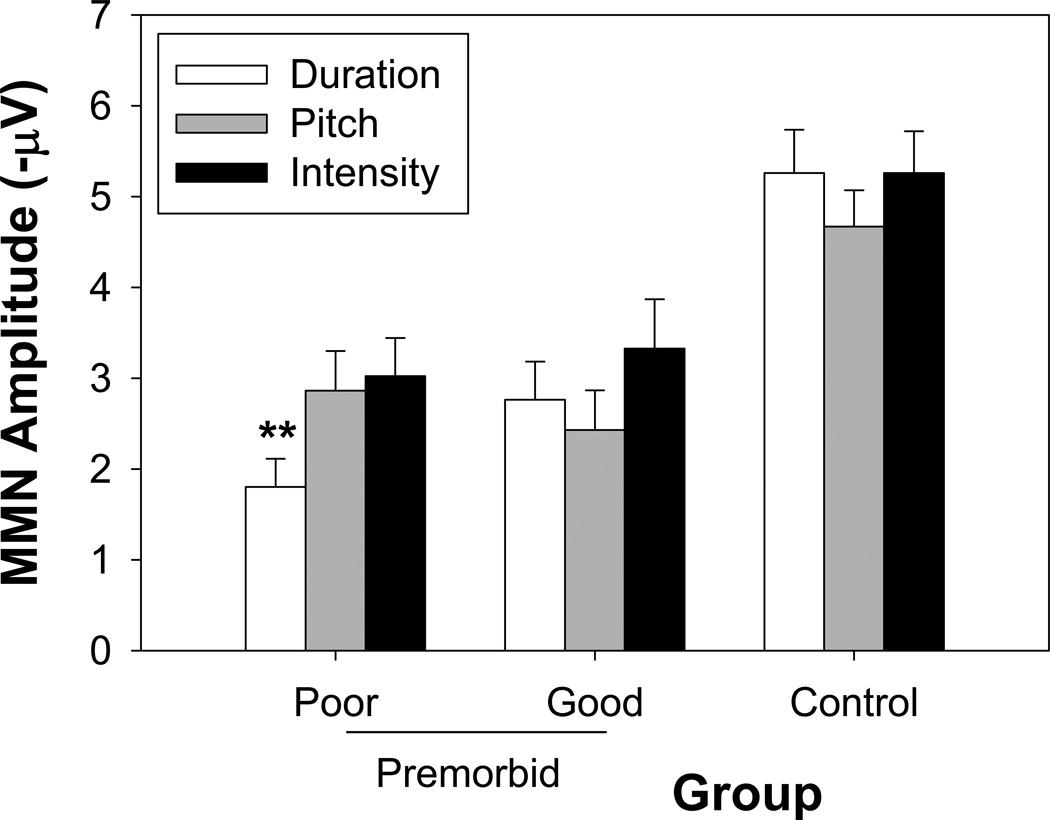

When assessed categorically across 3 groups (poor vs. good premorbid patients vs. controls), there was not only a significant main effect of group (F(2,41)=13.7, p<.0001), but also a group X MMN-type interaction (F(4,82)=3.79, p=.007), reflecting smaller duration vs. pitch (p<.002) and duration vs. intensity (p<.002) in patients with poor premorbid educational achievement but not in the other two groups (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

MMN amplitudes in response to deviant types in patients with good and poor premorbid functioning and in controls. ** p<.002

For visual measures, there was no significant relationship between visual measures to LSF stimuli and educational status (r=.33, p=.46). Although there was a weak correlation between premorbid education status and P1 to HSF stimuli (r=.30, p=.045), the correlation became non-significant once group was included in the model (r=.14, p=.23). No significant correlations were observed between visual measures and illness duration.

Duration of illness

Across deviant types, there was a marginal correlation between MMN amplitude and illness duration (R=.54, F(3,21)=2.91, p=.06). However, significant correlations were observed with illness duration and both duration- (r=.53, p=.007) and intensity- (r=.41, p=.04) MMN independently, with longer illness durations predicting smaller MMN amplitude. Despite the correlation with illness duration, no significant correlation was observed with age at time of testing (all p>.08).

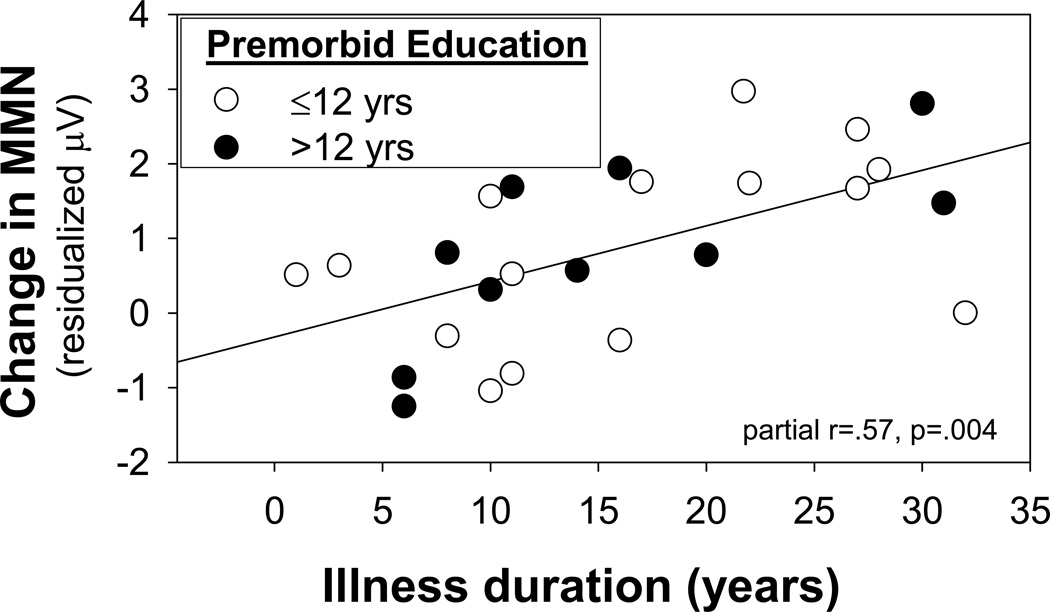

When premorbid education achievement and duration of illness were considered simultaneously, both were significant independent predictors (education: partial r= −.48, p=.018; illness duration: partial r=.57, p=.004) (Figure 7). When analyses were stratified by premorbid education, a significant group x MMN-type interaction was observed in patients with poor premorbid function (F(2,31)=8.19, p=.001) with greater reduction in MMN to duration (t=5.72, p<.0001) than to pitch (t=3.05, p=.005) or intensity (t=3.51, p=.001) deviants. In contrast, no significant relationship between illness duration and MMN was observed in this group (R=.45, F(3,11)=.95, p=.45). Patients with good premorbid status showed no differential reduction across MMN types (F(2,26)=0.55, p=.58), but a significant reduction with increasing illness duration (R=.90, F(3,6)=8.40, p=.014).

Figure 7.

Correlations between change in MMN amplitudes and years of illness duration for patients with good v. poor premorbid function. MMN values are residualized relative to contributions of good vs. poor premorbid function.

Clinical correlations

Symptoms

In addition to being associated with premorbid educational status, MMN amplitude across deviant types correlated significantly with degree of cognitive symptoms, which were measured using the PANSS (r=.70, p=.003). Significant independent correlations were observed between MMN to pitch (r=.61, p=.002) and intensity (r=.63, p=.001) deviants, with no significant correlation with MMN to duration deviants (r=.24, p=.26). No significant correlations with positive or negative symptoms were observed for any of the MMN types. No significant correlations were observed with symptoms and visual measures to either LSF or HSF stimuli.

Functional capacity

Functional capacity was assessed using both ILS and GAF. Across deviant types, reduced MMN amplitude was significantly associated with reduced score on the ILS (r=.62, p=.02), with significant independent correlation for duration- (r=−.45, p=.021) and intensity- (r=−.41, p=.047), but not pitch- (r=−.18, p=.4), MMN. In contrast, no significant correlation was observed between MMN and GAF. No significant correlation was observed between any visual measures and either ILS or GAF.

Medication

No significant relationship with medication dose, as reflected in CPZ equivalents, was observed for any of the experimental measures.

Correlations between visual and auditory measures

Across groups, amplitude of P1 to HSF (r=−.31, p=.04) and LSF (r=−.36, p=.02) stimuli correlated significantly with mean MMN amplitude. However, these correlations were no longer significant following control for group membership.

Discussion

Sensory deficits, as revealed by behavior, ERP and fMRI, have become increasingly well established in schizophrenia over recent years (55). The present study evaluates two sensory neurophysiological measures – auditory MMN and visual P1 - that are now widely used in schizophrenia research (6, 13, 55) with the goal of assessing their relative association with clinical features of the disorder. Primary findings are that, within the same patient sample, both auditory and visual ERP measures are reduced, but are differentially associated with demographic and clinical features. In particular, the study confirms our prior report of a significant association between poor premorbid educational achievement and MMN generation (39), while differentiating relative contributions of premorbid and disease related factors in overall MMN generation. Finally, the study adds to the growing list of social/occupational measures that have been linked to impaired MMN generation in schizophrenia.

Deficits in MMN generation have been reported consistently in chronic schizophrenia patients relative to age-matched controls. In a prior study, we noted the post-hoc observation that among first-episode subjects, MMN deficits were observed only in individuals who had failed to progress beyond high school, whereas in chronic patients deficits were observed among patients both with and without college education (39). In the present study, an extremely strong association between premorbid educational status and MMN was again observed, not only within schizophrenia subjects, but also across patients and controls (Figure 6). Furthermore, once the patient group was divided by premorbid function, differential patterns of dysfunction were observed. Thus, only for patients with poor premorbid function, was a greater deficit to duration than other deviant types observed (Figure 7). This may be particularly relevant given that reports of normal premorbid MMN derive primarily from studies which utilized pitch deviants (14, 15), whereas more recent studies showing relationship of MMN to prodromal status have utilized duration deviants (37, 38).

Such findings emphasize the need to use “optimized” MMN paradigms with independent pitch, duration and other deviant types per run, and to consider deviant type when discussing discrepancies within the MMN literature. In addition, this study demonstrates the need to consider potential neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative factors independently, with a discrepancy between MMN to duration vs. pitch deviance serving as a potential marker for a form of schizophrenia most associated with poor premorbid function. For both groups of patients, reductions were observed across MMN type, with increased deficit within increasing illness duration.

In the present study, a significant correlation was also observed between MMN and ILS. ILS measures problem solving ability for daily living, and is a proxy measure for ability to live independently. ILS has previously been shown to be related to impaired sensory processing, as reflected in impaired tone matching ability (56). There was no significant relationship between the GAF and MMN in the present study despite a prior report of significant association (26), suggesting that such correlations may be variable across cohorts (12). The present findings thus suggest that MMN may be most strongly associated with trait cognitive deficits and functional impairments, and less strongly with more labile symptom clusters and medication-sensitive variables.

In the present study, deficits in P1 generation to magnocellular-biased (LSF) stimuli were observed as in prior studies. Consistent with prior research, P1 was unrelated to premorbid function, symptoms, illness duration or functional outcome. However, this is the first study to demonstrate absence of these associations in the same cohort where associations with MMN were independently observed. The present study also demonstrates that both active visual and passive auditory ERP can be obtained within the same session, further optimizing ERP acquisition in neuropsychiatric research.

While confirming differential associations of auditory and visual ERPs to premorbid, demographic and clinical measures in schizophrenia, this study leaves unresolved the basis for the differential association. Both auditory (16, 18, 57, 58) and visual (59–61) ERP deficits in schizophrenia are linked to anatomical and histological changes within underlying generator regions. A potential basis for the differential association is the different timecourse of histological changes in auditory vs. visual regions during the development of schizophrenia. Thus, little progressive change in occipital gray matter is observed over the course of schizophrenia (62), suggesting that reductions in occipital volume likely predate onset of illness and play a permissive role in illness onset.

In contrast, progressive volume reduction occurs in auditory regions over the course of the illness (14, 15) and thus may be more related to illness onset and disease progression. In histological studies, differential involvement of primary (core) vs. secondary (belt, parabelt) auditory cortex has been reported (57, 58), potentially accounting for the differential association of pitch/intensity vs. duration deviants in patients with poor premorbid function. Within auditory regions, pitch and intensity MMN have been localized to primary auditory cortex, whereas duration MMN is generated primarily within secondary auditory regions which may mature later (63), potentially accounting for the differential association of pitch/intensity vs. duration MMN with premorbid function in schizophrenia.

Differential genetic architecture may also be important. For example, dysbindin risk haplotypes appear to affect anatomy of occipital and frontal, but not temporal brain regions (64), potentially accounting for the impaired visual ERP findings observed in carriers vs. non-carriers of the risk haplotype (65). Although both auditory and visual deficits have been linked to underlying glutamatergic dysfunction, particularly at N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDAR)-type glutamate receptors (55), the paths to NMDAR dysfunction are unknown and may differ across brain regions. Auditory and visual ERPs may therefore serve as biomarkers for different forms of schizophrenia and may help elucidate convergent pathological processes and risk mechanisms.

There are specific limitations to the study. First, all patients were receiving medication at the time of testing, so potential effects of medication cannot be discounted. Furthermore, patients with poor premorbid function, as assessed by education achievement, were receiving markedly high doses of antipsychotics despite similar levels of symptoms. Nevertheless, no correlation of medication dose with sensory function was observed either within or across patient groups. Thus, the greater MMN deficits observed in poor premorbid patients is unlikely to be a direct result of higher medication dosage.

Second, our division of patients into good vs. poor premorbid function was based on education achievement alone. In a prior study (39), we observed that other measures, such as retrospective assessment of social function, were not predictive of MMN. Objective data regarding premorbid patient status can be observed for limited patient samples (e.g. army database registries), suggesting need for future studies investigating such patients. Educational achievement can also be obtained objectively, but may be confounded by educational opportunites. At present, the specific premorbid features (including premorbid IQ) related to MMN deficits at illness onset (or prior) remain to be determined, and will be an important area of research.

In sum, although auditory MMN and visual P1 deficits are reliably associated with schizophrenia and are both present in the same subject sample, these measures have distinct functional correlates. MMN shows significant correlation with both premorbid and current functional status and illness duration, whereas visual P1, especially to LSF stimuli, shows deficits irrespective of these measures. In addition, present findings provide the first evidence for separate neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative “paths” to impaired MMN generation in schizophrenia, with duration MMN most specifically linked to poor premorbid, presumed neurodevelopmental dysfunction. Overall, present findings demonstrate that sensory dysfunction, while reliably present, is not a unitary phenomenon in schizophrenia, suggesting that these measures may index differential underlying functional and neurogenetic mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R37MH49334 and P50MH086385 to DCJ.

The authors would like to thank Drs. John Foxe and Sophie Molholm for assistance with paradigm development and supervision of data collection, and Erica Saccente for her assistance in data analysis.

References

- 1.Holcomb HH, Ritzl EK, Medoff DR, Nevitt J, Gordon B, Tamminga CA. Tone discrimination performance in schizophrenic patients and normal volunteers: impact of stimulus presentation levels and frequency differences. Psychiatry research. 1995;57(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strous RD, Cowan N, Ritter W, Javitt DC. Auditory sensory ("echoic") memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 1995;152(10):1517–1519. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.10.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Javitt DC, Doneshka P, Zylberman I, Ritter W, Vaughan HG., Jr. Impairment of early cortical processing in schizophrenia: an event-related potential confirmation study. Biological psychiatry. 1993;33(7):513–519. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shelley AM, Ward PB, Catts SV, Michie PT, Andrews S, McConaghy N. Mismatch negativity: an index of a preattentive processing deficit in schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 1991;30(10):1059–1062. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Umbricht D, Bates J, Lieberman J, Kane J, Javitt D. Electrophysiological Indices of Automatic and Controlled Auditory Information Processing in First-Episode, Recent-Onset and Chronic Schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 2006;59(8):762–772. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler PD, Javitt DC. Early-stage visual processing deficits in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18(2):151–157. doi: 10.1097/00001504-200503000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Javitt DC. When doors of perception close: bottom-up models of disrupted cognition in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:249–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naatanen R. The mismatch negativity: A powerful tool for cognitive neuroscience. Ear Hear. 1995;16:6–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington: American Psychiatric Press Inc; 2000. Text Revision ed. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bendixen A, Prinz W, Horvath J, Trujillo-Barreto NJ, Schroger E. Rapid extraction of auditory feature contingencies. Neuroimage. 2008;41(3):1111–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroger E, Wolff C. Mismatch response of the human brain to changes in sound location. Neuroreport. 1996;7(18):3005–3008. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199611250-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umbricht D, Krljes S. Mismatch negativity in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia research. 2005;76(1):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naatanen R, Kahkonen S. Central auditory dysfunction in schizophrenia as revealed by the mismatch negativity (MMN) and its magnetic equivalent MMNm: a review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(1):125–135. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salisbury DF, Shenton ME, Griggs CB, Bonner-Jackson A, McCarley RW. Mismatch negativity in chronic schizophrenia and first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(8):686–694. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salisbury DF, Kuroki N, Kasai K, Shenton ME, McCarley RW. Progressive and interrelated functional and structural evidence of post-onset brain reduction in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):521–529. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasser PE, Schall U, Todd J, Michie PT, Ward PB, Johnston P, et al. Gray Matter Deficits, Mismatch Negativity, and Outcomes in Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Javitt DC, Steinschneider M, Schroeder CE, Arezzo JC. Role of cortical N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in auditory sensory memory and mismatch negativity generation: implications for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(21):11962–11967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Javitt DC. Intracortical mechanisms of mismatch negativity dysfunction in schizophrenia. Audiol Neurootol. 2000;5(3–4):207–215. doi: 10.1159/000013882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Todd J, Michie PT, Jablensky AV. Association between reduced duration mismatch negativity (MMN) and raised temporal discrimination thresholds in schizophrenia. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114(11):2061–2070. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Javitt DC, Shelley A, Ritter W. Associated deficits in mismatch negativity generation and tone matching in schizophrenia. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111(10):1733–1737. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Todd J, Michie PT, Jablensky AV. Association between reduced duration mismatch negativity (MMN) and raised temporal discrimination thresholds in schizophrenia. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2003;114(11):2061–2070. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiang M, Light GA, Prugh J, Coulson S, Braff DL, Kutas M. Cognitive, neurophysiological, and functional correlates of proverb interpretation abnormalities in schizophrenia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13(4):653–663. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turetsky BI, Bilker WB, Siegel SJ, Kohler CG, Gur RE. Profile of auditory information-processing deficits in schizophrenia. Psychiatry research. 2009;165(1–2):27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiang M, Light GA, Prugh J, Coulson S, Braff DL, Kutas M. Cognitive, neurophysiological, and functional correlates of proverb interpretation abnormalities in schizophrenia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2007;13(4):653–663. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wynn JK, Sugar C, Horan WP, Kern R, Green MF. Mismatch negativity, social cognition, and functioning in schizophrenia patients. Biological psychiatry. 2010;67(10):940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Light GA, Braff DL. Mismatch negativity deficits are associated with poor functioning in schizophrenia patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(2):127–136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Light GA, Swerdlow NR, Braff DL. Preattentive sensory processing as indexed by the MMN and P3a brain responses is associated with cognitive and psychosocial functioning in healthy adults. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2007;19(10):1624–1632. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.10.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leitman DI, Laukka P, Juslin PN, Saccente E, Butler P, Javitt DC. Getting the cue: sensory contributions to auditory emotion recognition impairments in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):545–556. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leitman DI, Laukka P, Juslin PN, Saccente E, Butler P, Javitt DC. Getting the cue: sensory contributions to auditory emotion recognition impairments in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36(3):545–556. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leitman DI, Sehatpour P, Higgins BA, Foxe JJ, Silipo G, Javitt DC. Sensory deficits and distributed hierarchical dysfunction in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):818–827. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09030338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jessen F, Fries T, Kucharski C, Nishimura T, Hoenig K, Maier W, et al. Amplitude reduction of the mismatch negativity in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2001;309(3):185–188. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michie PT, Innes-Brown H, Todd J, Jablensky AV. Duration mismatch negativity in biological relatives of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Biological psychiatry. 2002;52(7):749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01379-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bramon E, Croft RJ, McDonald C, Virdi GK, Gruzelier JG, Baldeweg T, et al. Mismatch negativity in schizophrenia: a family study. Schizophrenia research. 2004;67(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magno E, Yeap S, Thakore JH, Garavan H, De Sanctis P, Foxe JJ. Are auditory-evoked frequency and duration mismatch negativity deficits endophenotypic for schizophrenia? High-density electrical mapping in clinically unaffected first-degree relatives and first-episode and chronic schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 2008;64(5):385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jessen F, Fries T, Kucharski C, Nishimura T, Hoenig K, Maier W, et al. Amplitude reduction of the mismatch negativity in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;309(3):185–188. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brockhaus-Dumke A, Tendolkar I, Pukrop R, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkotter J, Ruhrmann S. Impaired mismatch negativity generation in prodromal subjects and patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2005;73(2–3):297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shin KS, Kim JS, Kang DH, Koh Y, Choi JS, O'Donnell BF, et al. Pre-attentive auditory processing in ultra-high-risk for schizophrenia with magnetoencephalography. Biological psychiatry. 2009;65(12):1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bodatsch M, Ruhrmann S, Wagner M, Muller R, Schultze-Lutter F, Frommann I, et al. Prediction of Psychosis by Mismatch Negativity. Biological psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Umbricht DS, Bates JA, Lieberman JA, Kane JM, Javitt DC. Electrophysiological indices of automatic and controlled auditory information processing in first-episode, recent-onset and chronic schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 2006;59(8):762–772. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Todd J, Michie PT, Schall U, Karayanidis F, Yabe H, Naatanen R. Deviant matters: duration, frequency, and intensity deviants reveal different patterns of mismatch negativity reduction in early and late schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 2008;63(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butler PD, Schechter I, Zemon V, Schwartz SG, Greenstein VC, Gordon J, et al. Dysfunction of early-stage visual processing in schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1126–1133. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foxe JJ, Doniger GM, Javitt DC. Early visual processing deficits in schizophrenia: impaired P1 generation revealed by high-density electrical mapping. Neuroreport. 2001;12(17):3815–3820. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schechter I, Butler PD, Zemon VM, Revheim N, Saperstein AM, Jalbrzikowski M, et al. Impairments in generation of early-stage transient visual evoked potentials to magno- and parvocellular-selective stimuli in schizophrenia. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116(9):2204–2215. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butler PD, Martinez A, Foxe JJ, Kim D, Zemon V, Silipo G, et al. Subcortical visual dysfunction in schizophrenia drives secondary cortical impairments. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 2):417–430. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeap S, Kelly SP, Sehatpour P, Magno E, Javitt DC, Garavan H, et al. Early visual sensory deficits as endophenotypes for schizophrenia: high-density electrical mapping in clinically unaffected first-degree relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(11):1180–1188. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sehatpour P, Dias EC, Butler PD, Revheim N, Guilfoyle DN, Foxe JJ, et al. Impaired visual object processing across an occipital-frontal-hippocampal brain network in schizophrenia: an integrated neuroimaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(8):772–782. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Revheim N, Butler PD, Schechter I, Jalbrzikowski M, Silipo G, Javitt DC. Reading impairment and visual processing deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2006;87(1–3):238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butler PD, Abeles IY, Weiskopf NG, Tambini A, Jalbrzikowski M, Legatt ME, et al. Sensory contributions to impaired emotion processing in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(6):1095–1107. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Revheim N, Medalia A. The independent living scales as a measure of functional outcome for schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(9):1052–1054. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Green MF, Schooler NR, Kern RS, Frese FJ, Granberry W, Harvey PD, et al. Evaluation of functionally-meaningful measures for clinical trials of cognition enhancement in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030414. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zion-Golumbic E, Deouell LY, Whalen DH, Bentin S. Representation of harmonic frequencies in auditory memory: a mismatch negativity study. Psychophysiology. 2007;44(5):671–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Javitt DC, Shelley AM, Silipo G, Lieberman JA. Deficits in auditory and visual context-dependent processing in schizophrenia: defining the pattern. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(12):1131–1137. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kay SR. Positive-negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia: psychometric issues and scale comparison. Psychiatr Q. 1990;61(3):163–178. doi: 10.1007/BF01064966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loeb P. Independent Living Scales Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Javitt DC, Spencer KM, Thaker GK, Winterer G, Hajos M. Neurophysiological biomarkers for drug development in schizophrenia. Nature reviews. 2008;7(1):68–83. doi: 10.1038/nrd2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Revheim N, Schechter I, Kim D, Silipo G, Allingham B, Butler P, et al. Neurocognitive and symptom correlates of daily problem-solving skills in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2006;83(2–3):237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.12.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sweet RA, Pierri JN, Auh S, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Reduced pyramidal cell somal volume in auditory association cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(3):599–609. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smiley JF, Rosoklija G, Mancevski B, Mann JJ, Dwork AJ, Javitt DC. Altered volume and hemispheric asymmetry of the superficial cortical layers in the schizophrenia planum temporale. The European journal of neuroscience. 2009;30(3):449–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Butler PD, Zemon V, Schechter I, Saperstein AM, Hoptman MJ, Lim KO, et al. Early-stage visual processing and cortical amplification deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(5):495–504. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Butler PD, Hoptman MJ, Nierenberg J, Foxe JJ, Javitt DC, Lim KO. Visual white matter integrity in schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006;163(11):2011–2013. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dorph-Petersen KA, Pierri JN, Wu Q, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Primary visual cortex volume and total neuron number are reduced in schizophrenia. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501(2):290–301. doi: 10.1002/cne.21243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun D, Stuart GW, Jenkinson M, Wood SJ, McGorry PD, Velakoulis D, et al. Brain surface contraction mapped in first-episode schizophrenia: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Molecular psychiatry. 2009;14(10):976–986. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Molholm S, Martinez A, Ritter W, Javitt DC, Foxe JJ. The neural circuitry of pre-attentive auditory change-detection: an fMRI study of pitch and duration mismatch negativity generators. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15(5):545–551. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Donohoe G, Frodl T, Morris D, Spoletini I, Cannon DM, Cherubini A, et al. Reduced occipital and prefrontal brain volumes in dysbindin-associated schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 35(2):368–373. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Donohoe G, Morris DW, De Sanctis P, Magno E, Montesi JL, Garavan HP, et al. Early visual processing deficits in dysbindin-associated schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 2008;63(5):484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.