Abstract

The oocytes of the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) comprise one of the most widely used membrane protein expression systems. While frequently used for studies of transporters and ion channels, the application of this system to the study of mechanosensitive ion channels has been overlooked, perhaps due to a relative abundance of native expression systems. Recent advances, however, have illustrated the advantages of the oocyte system for studying plant and bacterial mechanosensitive channels. Here we describe in detail the methods used for heterologous expression and characterization of bacterial and plant mechanosensitive channels in Xenopus oocytes.

Keywords: Mechanosensitive ion channel, Heterologous expression, Xenopus laevis oocytes, Patch-clamp electrophysiology, Pressure-clamp

1 Introduction

Oocytes of the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) have been used for several decades for the expression of transporters and receptors from bacteria [1], plants [2, 3], and mammals [4–6] due to the simplicity and reliability of this experimental system [7]. Relatively low background ion channel activity [8], large size (1–1.5 mm), low cost, and ease of handling make these cells a favored system for the expression of human, plant and bacterial channels. Xenopus oocytes have also been used as a model system for the study of processes unrelated to ion transport such as apoptosis [9, 10], gene expression [11], the structure and function of the nuclear envelope [12] and many others [13].

While most mechanosensitive channels (MSCs) have been characterized under native conditions [14–16], we have recently expressed and characterized two MSCs in Xenopus oocytes, MscS from Escherichia coli and MSL10 from Arabidopsis thaliana [17, 18]. Our analyses were made possible by previous studies showing that the endogenous MSCs known to be present in the oocyte membrane [8, 19, 20] can be effectively blocked or inactivated [21, 22]. A number of useful papers on frog maintenance [23], oocyte expression and transport systems [3, 24–28], oocyte isolation, and the methods used for characterization of ligand- and voltage-gated channels in the Xenopus oocyte system [29–33] have been published to date. Here we focus on the methods we used for the heterologous expression and characterization of MscS and MSL10 at the single-channel level. We describe in detail the techniques for surgery, oocyte isolation and preparation, in vitro RNA production and injection into oocytes, and basics of MSC electrophysiology, including patch-clamp and pressure-clamp.

2 Materials

Special attention must be paid to water quality at several stages in this procedure. The water used for surgery solutions should be the same water in which the frog is maintained in the animal facility. Water used in buffers for oocyte isolation and patch-clamp should be distilled and filter-sterilized (0.2 μm) or autoclaved. Water used for complimentary RNA (cRNA) production must be DNase- and RNase-free. All solutions (apart from those made right before the experiment or requiring freezer storage) should be kept in a refrigerator. Gentamycin-containing buffers should be stored together with oocytes at 16–18°C.

2.1 Frog Surgery

Anesthetic solution: 0.5-1 L of 1.5 g/L MS-222 (ethyl-3-aminobenzoate methanesulfonate) buffered with 840 mg/L NaHCO3 and dissolved in pretreated water from the animal facility.

Complete N96 buffer: 96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.38.

Penicillin streptomycin (Pen Strep) solution (100× solution).

Sterile autoclaved forceps and scissors.

Sutures (2 pieces each of Monocryl undyed monofilament (Ethicon) and Ethilon black monofilament (Ethicon)).

Parafilm.

50-ml conical tube with 20 ml of ND96 buffer.

Lab coat, gloves and eye protection.

70 % ethanol or Lysol for benchtop sterilization.

2.2 Oocyte Isolation

Ca2+ -free N96 buffer: 96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.38.

0.1 g collagenase A type I, in 20 ml Ca2+ -free ND96.

250 ml of 0.1 % BSA in Ca2+ -free ND96.

30 ml of 50 mM KH2PO4/50 mM K2HPO4 with 0.01 % BSA in water, pH 6.5 (made in advance and stored as 45 mL aliquots at −20°C).

Complete ND96 buffer supplemented with 50 mg/ml gentamycin.

50-ml conical tubes.

100 mm × 15 mm petri dishes.

Plastic transfer pipettes (62 μl aperture, large bulb).

Incubator capable of maintaining 16–18°C (such as a wine cooler).

2.3 RNA Preparation

mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion).

RNase-free water.

RNase-free pipette tips and tubes.

Spectrophotometer suitable for measuring the concentration and purity of nucleic acids (e.g., NanoPhotometer, Implen).

2.4 Oocyte Injection

RNase-free water.

Mineral oil.

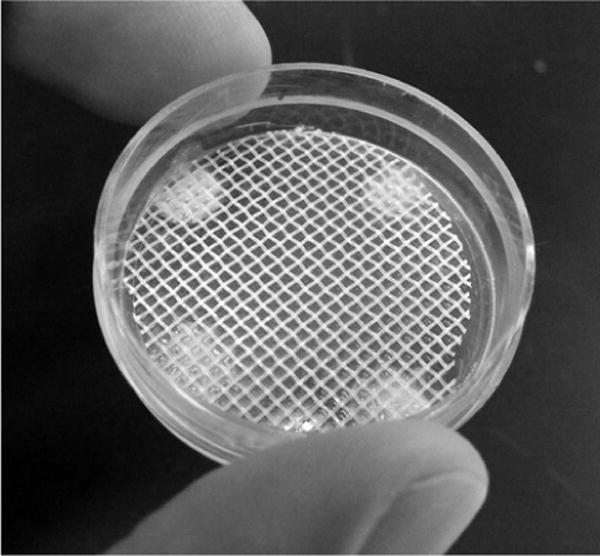

Gridded petri dish (a regular 35 mm petri dish with a polypropylene mesh glued to its bottom, see Fig. 1).

Capillary glass for an injection pipette. We use a thin-walled 8 in.-long pipette.

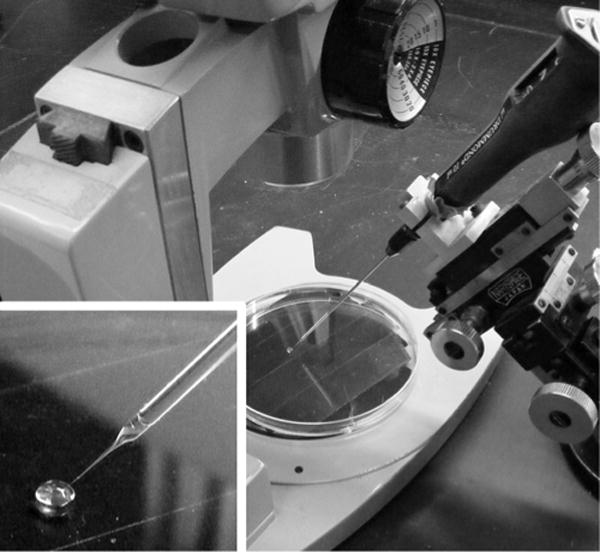

Micropipette or automatic injection system (see Fig. 2).

Pipette puller (P97, Sutter Instrument Co) (see Note 1).

RNase-free pipette tips.

6-well tissue culture plates.

Fig. 1.

Image of a custom-made gridded petri dish. Plastic mesh is glued to the bottom of a 35-mm dish. Each cell of the grid accommodates a single oocyte

Fig. 2.

Setup for oocyte injection. A manually driven micropipettor (on the right) should be capable of reproducibly and accurately injecting 50 nl of solution into a single oocyte. Inset: RNAse-free water is sucked into the pipette from a drop in a petri dish

2.5 Patch-Clamp

10 ml of hypertonic buffer: 200 mM K+ -aspartate, 20 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4.

10 ml of ND96 with 10 mM of MgCl2.

10 ml of TEA-Cl buffer: 98 mM TEA-Cl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.38 adjusted with TEA-OH, 0.2 μm filtered.

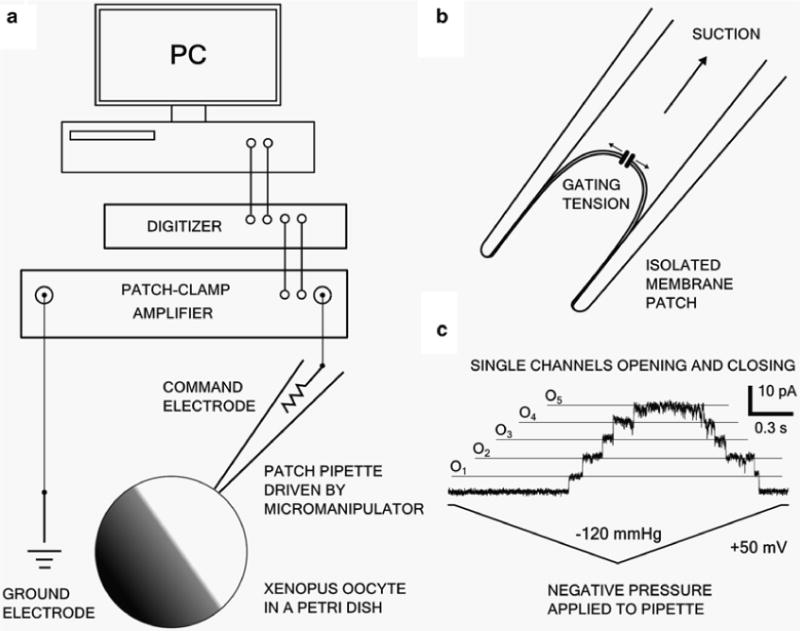

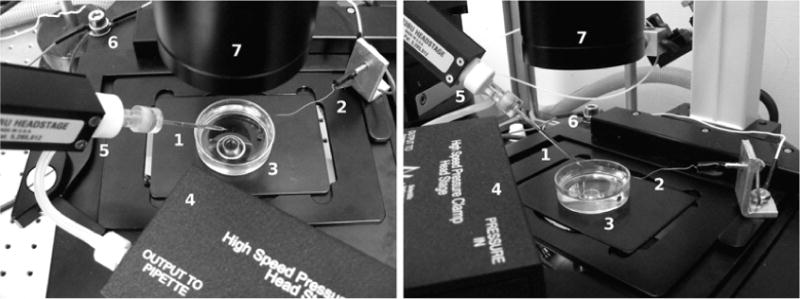

Patch-clamp rig: amplifier (Axopatch 200B, Molecular Devices), digitizer (Digidata 1440A, Molecular Devices), micromanipulator (Patchstar, Scientifica) and (preferably inverted) microscope with 20× lens (see Figs. 3a and 4).

Pressure-clamp machine (ALA Scientific Instruments HSPC-1) (see Note 2).

Anti-vibration table (Technical Manufacturing Corporation, system 63–533) with a Faraday cage.

Noise filter/surge suppressor (Isobar 12 Ultra, Tripp-Lite).

Pipette puller (P97, Sutter Instrument Co).

Capillary glass for a patch-pipette. We use a 1.5 mm inner diameter, 1.8 mm outer diameter, 100 mm long borosilicate pipette (see Note 3).

Fig. 3.

Diagram of the experimental setup and typical results. (a) Schematic representation of the patch-clamp setup. (b) Illustration of a membrane patch with applied suction and a single MSC opening in response to increased membrane tension. (c) Representative trace showing five opening and closing MSL10 channels. A 50 mV command potential and a −120 mmHg symmetric pressure ramp were used. The trace was sampled at 20 kHz with a 5 kHz low-pass Bessel filter (Axopatch 200B), then filtered at 1 kHz and exported as graphics via Clampfit software (Molecular Devices)

Fig. 4.

Experimental setup, shown from two angles. The glass patch pipette (1) is located above the ground electrode (2) immersed into a petri dish filled with bath buffer (3). The microscope objective is located underneath. Also shown are the pressure-clamp headstage (4), the pipette holder (5), the common ground point (6), and the inverted microscope condenser (7)

3 Methods

Surgery is not performed until cRNA has been made and quantified (see Subheading 3.3). This prevents unnecessary surgeries. The surgery and oocyte isolation occur on the same day and injections are done the following day. Our protocol for surgery and oocyte isolation is based on [34].

3.1 Frog Surgery

Immerse a frog in the MS-222/NaHCO3 solution for 10–15 min, until she does not respond to pinching of the skin between the toes. 13 min is optimal in our hands.

Rinse the frog with pretreated animal facility water to remove the anesthetic from its skin.

Put the frog on a wet paper towel and perform the surgery with sterile instruments, on a benchtop sterilized by spraying with 70 % ethanol, using sterile gloves. Keep the frog moist with sterile ND96 solution (see Note 4).

Make a small incision through the skin of the abdomen, using sharp scissors, followed by an incision of about 1 cm in the muscle layer. Rinse with ND96. (If the skin is slippery, grasp it with two fingers through a piece of clean paper towel). Place a sheet of Parafilm with a square cut in the middle over the incision, so that oocytes extracted from the abdomen will not come in contact with the surface of the frog’s skin.

Pull 2–4 ml of oocytes out of the body cavity with dull forceps and place in 25 ml of ND96 in a 50 ml conical tube.

Repair the incision with two sets of sutures, one for the muscle tissue (undyed) and one for skin (black). Each stitch is made with two loops of single knots and a third loop of double knots (three stitches) per 1–1.5 cm incision. The last knot should be pulled tight, and the ends trimmed closely.

Wash the frog with 0.5 L of clean water taken from the facility in order to get rid of any blood and anesthetic on her skin.

Allow the frog to recover in 0.5 L of Pen Strep solution (5 ml of 100× Pen Strep stock in 0.5 L of treated water from the frog facility) for 40–60 min. Tilt the plastic bath 45° from the vertical so that most of the frog’s body is submerged in the buffer. Care must be taken that the frog does not drown (keep her nostrils above the water level) but her skin stays wet. When she starts to move in response to pinching, she’s almost recovered. Once the frog recovers, return her to a clean cage with fresh water.

Depending on institutional rules, a frog could be operated on up to 5 times, with the last operation terminal. The operations should be 4–6 weeks apart and alternating sides of the abdomen used. After the last operation the frog may be euthanized according to the rules of your institution (see Note 5).

3.2 Oocyte Isolation

Separate the ovarian tissue into clumps of 10–20 oocytes each in a petri dish, using forceps and working under a stereomicroscope. Transfer the clumps into Ca2+ -free ND96. Try to avoid damage to the oocytes.

Incubate the oocytes in a petri dish with slow shaking for 25–40 min at room temperature in 20 ml of Ca2+ -free ND96 with collagenase. Ca2+ -free medium is used to slow down the collagenase reaction as Ca2+ strongly activates collagenase [35]. Stop the process as soon as single oocytes are released.

Wash the oocytes 5 times with 25 ml ND96 + 0.1 % BSA in a 50 ml conical tube.

Add 25 ml 0.1 M potassium phosphate pH 6.5 buffer and incubate for 40–50 min on a slow shaker. At 15-min intervals, draw the oocytes into a wide-bore plastic pipette (made by trimming the tip) and pipette up and down to facilitate dispersal.

Wash the oocytes 5 times with 25 ml ND96 + 0.1 % BSA in a 50 ml conical tube.

Sort the oocytes in a petri dish under the microscope, selecting only mature oocytes (Dumont stage V-VI, [36]) with clear animal–vegetal pole divisions and without any spots, markings or residual ovarian tissue on the surface. Manipulate single oocytes with plastic transfer pipettes (see Subheading 2). Store the selected oocytes in complete ND96 with 50 mg/ml gentamycin at 16–18°C.

3.3 RNA Preparation

The sequence of the RNA of interest should first be cloned into an expression vector appropriate for cRNA production and its translation in oocytes. We use pOO2, a vector that allows cloning of a cDNA in between the 5′- and 3′-untranslated β-globin sequences from Xenopus [37].

Linearize approximately 5 μg of template DNA in a 70 μl reaction. Use a restriction enzyme that recognizes a single site in the vector downstream of the sequence to be transcribed (see Note 6).

Run 4 μl of the sample on a gel to ensure linearity.

Add 5 μl 0.5 M EDTA, 4 μl 5 M NaCl, 25 μl RNase-free water and mix well.

Add 200 μl 100 % ethanol.

Mix well and place at −20°C for at least 20 min.

Spin for 15 min on a benchtop centrifuge at top speed.

Carefully remove supernatant and dry the pellet.

Resuspend the pellet in 25 μl RNase-free water and calculate the concentration of DNA by measuring the OD260.

Follow the protocol supplied with Ambion mMessage mMachine kit to produce the cRNA of interest (see Note 7).

Aliquot the cRNA solution (it should be approximately 1 μg/μl) into 3 μl aliquots and store at −20°C.

3.4 Oocyte Injection

Place 10–40 oocytes into a gridded petri dish (see Fig. 1) filled with complete ND96. Place each oocyte into a square of the plastic grid with the light side (vegetal pole) up.

Thaw RNase-free water and cRNA on ice.

Pull long needles from 8 in. capillary glass on a puller. For a Sutter P-97 the following program may be a good starting point: heat = 560, pull = none, velocity = 120, time = 100. Trim the end of each needle with scissors 5–6 mm before the point where the pulled portion of the pipette becomes flexible.

Backfill the needle with 13–15 μl of mineral oil using a micropipette, then apply the needle to the pipette or injector apparatus. Make sure there are no bubbles in the oil, then pull approximately 500 nl of RNase-free water into the tip from a drop placed on a petri dish, followed by all 3 μl of your cRNA sample (see Note 8).

Using a microinjector or a micropipette attached to the glass needle (see Fig. 2), inject 50 nl of the cRNA solution into each oocyte, preferably into the light side and close to the animal/vegetative border (see Note 9).

Repeat steps 4 and 5 above with fresh oocytes and RNase-free water as a negative control.

Place the oocytes into a 6-well plate filled with complete ND96 with gentamycin.

Change the solution and remove defective oocytes on a daily basis until analysis (see Notes 10 and 11).

3.5 Patch-Clamp

The microscope stage setup, including a dish with bath medium, command and ground electrodes, patch pipette and a pressure clamp headstage, is presented in Figs. 3a (schematic view) and 4 (actual setup).

Conventional single-channel patch-clamp is carried out using pipettes with BN (“bubble number”, see ref. 38) of 4–7 in symmetric and asymmetric buffers.

Prior to patching, the transparent vitelline membrane of each oocyte should be removed with a pair of sharp forceps after 5–10 min incubation in hypertonic buffer, which makes the cell shrink and the vitelline membrane more visible (see Note 12). After removal of the vitelline membrane, the oocyte becomes very fragile, so it should not be exposed to the surface of the buffer and care should be taken when moving it. We suggest removing the vitelline membrane in the petri dish to be used for patch-clamp, already filled with patching bath buffer.

A patch-pipette should be fabricated using a pipette puller (see appropriate manual for measuring glass melting temperature and initial proxy settings that can be adjusted to get the pipette of desired size and shape). Typically, a pipette with tip size between 0.5 and 2 µm is required, which corresponds to BN 4–6 and a resistance of several MΩ, depending on the tips’ length and geometry.

The command (or pipette) electrode is a small piece of Ag wire that has been chlorinated either by immersion into 6 % bleach for 15–25 min or by subjecting it to proper potential in KCl buffer [ 39 ].

The ground electrode is an Ag/AgCl pellet, connected to the ground input of the amplifier’s headstage through the common ground (such as a Faraday cage or anti-vibration table) via Ag wire (see Note 13, Figs. 3a and 4). It does not matter where the electrode is grounded, only that everything metal be grounded at a single common point, with a stable electrical contact between the wires and grounding point. This can be tested with a standard multimeter. The ground electrode could be immersed into the bath solution directly or via an agar salt bridge (see Note 14). The Ag/AgCl pellet should be washed with distilled water after experiments are completed.

Back-fill the patch-pipette with buffer, making sure it is free of air bubbles. If bubbles form, they can sometimes be eliminated by tapping the pipette. Bubbles can be prevented in the first place by pulling some buffer into the empty pipette with a syringe before back-filling the rest of the pipette.

Before and during immersion of the pipette into the bath buffer, a positive pressure of 20–30 mmHg should be applied to it. After the pipette tip is immersed, the pressure may be lowered to 5–10 mmHg (see Note 15).

Bring the pipette tip close to the oocyte membrane. The state of the pipette tip should be monitored by periodic application of low amplitude square voltage pulses of approximately 5 mV to the command electrode. In Axopatch amplifiers, use the “seal test mode”, where steps are gated by the amplifier’s internal line frequency oscillator. If the tip resistance grows (the current decreases) before the tip touches the oocyte membrane, replace the pipette, as its tip is likely obstructed with debris.

The moment of touching the oocyte membrane is observed electrically as a decrease of the measured current. When it decreases to 2/3–1/2 of its initial value, stop pipette motion and immediately decrease the pressure in the pipette from slightly positive to about −10 mmHg.

Observe the gradual formation of the “gigaseal” between the membrane and the pipette as the resistance of the pipettemembrane contact increases to 1 GΩ or more (see Note 16). After a gigaseal is reached you have obtained the cell-attached configuration (see Note 17). Next, bring the pipette pressure to between −1 and −3 mm Hg.

Excise the patch by rapid removal of the pipette away from the oocyte membrane. If the patch is not stable, this may result in patch rupture. Alternatively a membrane vesicle may form in the pipette tip and block it (usually when the pipette is not moved away from the cell quickly enough, see Note 18).

Once the patch is in the “excised” (in this particular case, “inside-out”) patch configuration (see Notes 19 and 20 and Fig. 3b), one can proceed to stimulation of MSCs. We recommend using a fixed transmembrane voltage of −20 to −40 mV and applying triangular 4- or 5-second-long symmetric ramps of negative pressure to the patch pipette, allowing for the gradual opening and closing of individual MSCs (see Note 21). A typical trace obtained from the membrane patch of an oocyte expressing MSL10 from A. thaliana [18] is presented in Fig. 3c for reference.

Once a tension-induced channel activity is detected and recorded, be sure to repeat patch excision and current measurement on water-injected oocytes to ensure the absence of artifacts or unusually high endogenous channel activity.

We have observed that the localization of the channel usually is not uniform within the oocyte membrane and several patches from the same cell may be necessary to locate channel activity, especially if a small pipette diameter is used.

In our hands, the endogenous cation-selective MSCs that are often observed in the cell-attached configuration inactivate upon patch excision, especially in the presence of elevated MgCl2 or in TEA-Cl buffer (see Notes 22–24).

The rare appearance of an endogenous, large-conductance Ca2+ -activated chloride channel (see ref. 8) should also be taken into account (see Note 25). However, it usually does not present a serious problem as long as small patch-pipettes are used, due to its relatively low expression.

A good starting point for recording settings would include the following: (1) acquisition at 20 kHz with the amplifier’s low pass filter set to 5–10 kHz (depending on the available settings); (2) a 4–5 s pressure ramp of −20 to −80 mmHg (depending on the pipette size, see Note 26), which in most cases eliminates artifacts caused by a too rapid increase in tension; and (3) a holding potential of 20 mV to 40 mV (pipette voltage) for the inside-out configuration, which typically provides clean and artifact-free traces (see Notes 26 and 27).

Once several channels are activated in the patch, one may study the channel’s voltage dependence. To do so, repeat the measurement with the same transmembrane pressure but at various potentials (see Note 28).

Pressure may be gradually increased by increments of −10 to −40 mmHg in order to activate more channels in the patch and obtain a dose-response curve (see Note 29).

For additional recommendations on data collection and statistical analysis, see Notes 30 and 31.

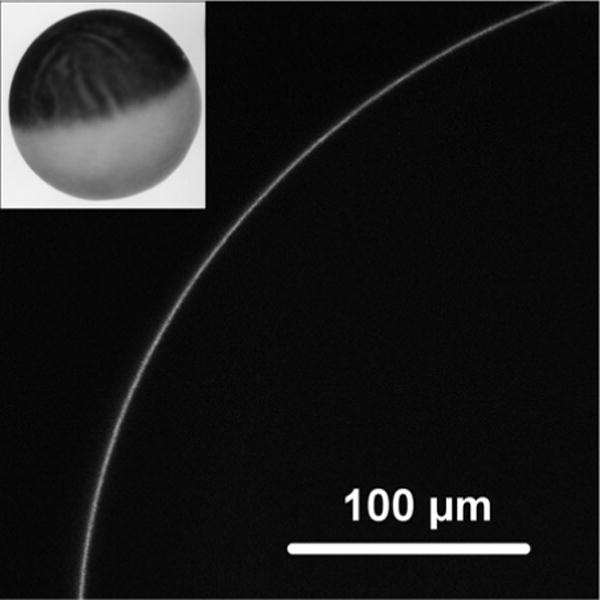

Fig. 5.

A laser-scanning confocal micrograph of the fluorescent signal from the periphery of an oocyte RNA 7 days after injection with MscS-GFP cRNA. An oocyte in ND96 buffer was placed onto a glass slide with concaved bottom and covered with a coverslip. Under bright field the lens was focused on the edge of the oocyte, then the confocal scan with GFP filters (488/510 nm) setup was performed. Inset: oocyte image in bright field

Acknowledgments

Our work on bacterial and plant MSC electrophysiology was supported in part by American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funds through grant number R01GM084211 to Doug Rees, Rob Phillips and E.S.H. from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health, and continues under NIH 2R01GM084211 to D.R., R.P. and E.S.H. and N.S.F. MCB-1253103 to E.S.H. We would also like to acknowledge Daniel Schachtman for initial training in the use of oocytes.

Footnotes

Pipettes at this step could be pulled over a standard gas burner.

The advantage of using a pressure clamp machine is that it can be easily integrated into patch-clamp software (such as Clampex, Molecular Devices) and programmed to produce pressure signals of nearly any shape and length that can be synchronized with the applied voltage. Pressure could be also applied to the patch-pipette manually using a syringe. Pressure in this case may be measured using a manometer.

Pipettes should be made of alumosilicate or borosilicate glass. Pipettes with thicker walls made of harder glass usually produce lower noise. Additionally, the noise introduced by interactions at the glass–air–water interface could be decreased by coating the pipette tip with a silicone polymer. To do so, place a thin layer of Sylgard (Dow) on the pipette and induce polymerization with a stream of hot air or by contact with a heated metal coil. Capillaries containing an additional thin filament designed to facilitate filling with buffer are not recommended, as they typically result in higher noise levels and “patch creep” (upward movement of the membrane patch within the pipette tip) under applied pressure.

One may also perform surgery on ice to enhance the anesthetic. Soaking a paper towel in anesthetic solution is not necessary and usually results in longer frog recovery time, but may be recommended for a beginner. Typically the surgery takes 15–20 min, from making the first incision to completed stitching.

Euthanasia may be performed in 5 g/L solution of MS-222 for at least 15 min. Note, that your institution regulations may require much longer treatment (up to an hour).

Linearity is essential for transcription and any uncut vector will greatly reduce the amount of cRNA produced.

NTP/CAP and 10× reaction buffer should be mixed very well before use, and vortexing for over a minute is recommended. At this stage, RNase-free technique should be used: use only RNase-free certified tubes, wipe working surfaces with alcohol or RNase removing solutions, minimize contact of gloves with any objects apart from the tubes of the kit and cover the working space with paper towel when not in use.

Care should be taken that the mineral oil does not directly contact the cRNA solution and is not injected into oocytes. To ensure this, approximately 500 nl of water should be pulled into the pipette tip prior to the cRNA solution.

We have not observed a substantial difference in expression level depending on the location of cRNA injection. However, we do observe a higher number of channels per patch at the vegetal pole (light half).

Analysis can take place as early as 24 h and as late as 14 (up to 21 in rare cases) days after injection. Dead or damaged oocytes release substances that appear to damage the remaining healthy cells, so it may be useful to split the cells into several groups for longer storage times. The indications that an oocyte is damaged include, in order of increasing severity: the appearance of bright spots on the animal pole (dark half), blurring of the animal/vegetal pole dividing line, substantially increased cell size, and the appearance of white material extruded from the cell. If the damage is not too severe, patching is still possible as only a small fraction of intact membrane is required. In the case of a heavily damaged oocyte it becomes impossible to remove the vitelline membrane without oocyte rupture.

A good practice is to check for expression of the protein of interest. One option is to label the protein with a fluorescent tag (e.g., Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)) and check for signal from the periphery of the oocyte using a confocal microscope (see Fig. 5). This approach allows one to see if the fusion protein is localized to the plasma membrane. Another option is to use a tagged version and to detect it via Western blotting (using, for example, the isolation method described in ref. 40). This approach allows one to evaluate level of expression more quantitatively, but is more time-consuming.

If proper care is taken, this procedure could be carried out in regular ND96 buffer.

It is important that the anti-vibration table, Faraday cage, and microscope with its stage all be in good electric contact, which insures the absence of electric interference from external sources. Our recommendation is to physically connect all pieces with metal wires, preferably in a single place (see Fig. 4). Noise levels may be monitored visually with a command electrode attached to the amplifier’s headstage via acquisition software; noise should be at least 2–3 times lower than the expected signal from a single channel opening (see patch-clamp amplifier manual for typical acceptable noise levels). Induced low-frequency modulations (50 or 60 Hz) are typically caused by loopbacks and can be eliminated by connecting all power cables to the same noise filter/surge suppressor. In many cases, noise can be reduced with acquisition software suites such as Clampfit (Molecular Devices). However, these approaches may result in partial data loss, and it is preferable to make the initial recording with minimal noise. Note that any additional equipment (such as peristaltic pumps for a perfusion system, manipulators, etc.) most likely will require grounding too. A detailed step-by-step procedure for testing the amplifier’s internal noise is usually described in the user manual and should be performed at least once during the initial amplifier setup. It is recommended to repeat this test from time to time during standard use.

An agar bridge is an L-shaped glass capillary (the same diameter as used for patch-pipettes and bent in the flame of a gas burner) filled with 2–3 % agar in a 1 M KCl solution [41]. A heated agar solution is sucked into the capillary and then left to cool. The agar salt bridge should be rinsed with water and kept in salt solution in a fridge as it subject to bacterial invasion. If any signs of bacterial growth are detected, the bridge should be discarded and a new one made.

It is also often recommended that during immersion of the tip into the buffer, a stream of air should be applied to the buffer surface by blowing on it. This is intended to move away any debris and fragments of lipid monolayers from the water–air interface.

If this does not happen in a reasonable period of time (30–60 s) or at least a slow but steady growth of patch resistance is not observed, additional suction may be applied to the pipette (usually −20 to −50 mmHg), but it should not be very high as high suction may result in patch rupture (or inactivation for some kinds of MSCs). Additionally, a slightly negative potential (−10 to −20 mV) may be applied to the command electrode to facilitate “sealing” of the patch.

At this point, it is already possible to carry out measurements of currents in response to increased membrane tension. However, to remove the complicating contributions of the cell’s resting potential, series resistance, and endogenous MSCs we recommend proceeding to the excised patch configuration for further measurements.

The production of such a vesicle typically can’t be seen through the microscope (unless high magnification and DIC are used), but its formation results in a drop in current in response to high command potentials and the appearance of slow capacitive transient currents in response to voltage steps. Lifting the pipette tip into the air and then immediately immersing it into the bath buffer can disrupt the vesicle. If the vesicle collapses and the new seal is good, one can observe a slight increase of conductance.

The inside-out excised patch preserves the orientation of the membrane leaflets—i.e., it is the same as it was in the moment the pipette touched the cell membrane. In certain cases the opposite orientation (when the outer leaflet of the patch faces the bath solution but not the inner volume of the pipette (outside-out configuration)) may be of interest. In order to achieve the outside-out configuration, one should obtain a proper gigaseal in the cell-attached mode and then rupture the patch with a short pulse of either high voltage or negative pressure, thus obtaining direct electric access to the inner volume of the cell (whole-cell mode). Rapid backward removal of the pipette from the cell in this case typically results in the production of a membrane patch in the outside-out configuration. Outside-out patches are often less stable than inside-out patches.

The whole-cell mode is not of particular interest for characterization of MSCs in ooctyes due to a very high level of noise (caused by a huge size of the oocyte membrane) and high probability of membrane rupture under applied tension.

Membrane tension for the patch in the pipette obeys the law of Laplas and therefore is proportional to transmembrane pressure and curvature radius of the membrane patch. Large patches formed in large pipettes require lower transmembrane pressure in order to be exposed to the same tension as small patches formed in small pipettes.

The amount of endogenous MSC activity present in oocytes varies depending on the batch of oocytes, the frog, and the season of the year. Some scientists report that the season with the highest background activity is summer. Endogenous cation-selective MSCs may be inhibited by high concentrations of Mg2+ ions (see ref. 22) or very low concentrations of lanthanides (approximately 10 μM La3+ or Gd3+), strong blockers of calcium, potassium and many mechanosensitive channels (see ref. 21). However, it has been shown in the latter case that the inhibition of at least some non-selective MSCs (like MscS) by gadolinium is mediated by membrane lipids and may affect all MSCs at high enough levels [42].

If there are indications that the MSC of interest is non-selective or anion-selective, one may utilize tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA-Cl) buffer to investigate the ion selectivity of the channel. The TEA+ molecule is a blocker of many potassium channels [43] and due to its size (approximately 8 Å) is not able to permeate smaller channels. In our hands it blocked endogenous potassium MSCs, permeated E. coli MscS and did not permeate nor block A. thaliana MSL10 [17, 18]. Symmetric 100 mM TEA-Cl buffer usually works well and provides a very clean background, but it also requires the addition of Mg2+ (or other divalent ions) to form a tight membraneglass seal. In extreme cases, when sealing does not occur, a buffer consisting of 50–60 mM MgCl2 only (with no other ions) may be an option.

The formation of a seal between the membrane patch and the pipette occurs more slowly in TEA-Cl buffer. In order to facilitate the process, the concentration of MgCl2 in the buffer may be increased up to 20 mM.

If this problem persists, the Ca2+ -activated chloride channel may be inhibited by exclusion of Ca2+ ions from the buffer, or the addition of chelators or specific blocking agents. If the channels of interest are expected to be cation-selective (or, in some cases, non-selective) large non-permeant molecules such as 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid (MES) could be used instead of chloride.

Membrane potential is defined as the potential of the inner monolayer minus the potential of the outer monolayer, so that the membrane potential of a live cell is negative. For an insideout patch, a positive command potential (i.e., the potential applied through the amplifier to the command electrode in the patch-pipette) corresponds to a negative membrane potential. In case of the outside-out configuration, when the orientation of the monolayers is reversed (i.e., the inside one faces patchpipette), a positive command potential corresponds to a positive membrane potential of the same amplitude.

Higher membrane potentials (up to–100 mV for oocytes) on the one hand often result in better signal to noise ratio, but on the other hand may induce the appearance of multiple subconducting states of the channel and always reduce membrane stability. Positive membrane potentials, though they almost never appear in live cells (with an obvious exception of excitable ones), are still of interest as they allow one to characterize a channel’s behavior under asymmetric conditions and may provide information on its gating mechanism and even molecular structure.

This may be done either by changing the amplifier settings manually before each recording, or by using the software suite programming capabilities. In the latter case, the program will automatically execute several consecutive measurements with different settings (in this case—by changing command potential) and record the data for further analysis. Subsequently, the channel characteristics (such as its conductance) may be extracted from the data file using dedicated or third party software and plotted against membrane potential to produce a current/voltage (I/V)-curve. If the curve goes through zero point (i.e., zero current at zero potential but not zero in the vicinity of 0 mV), the channel is not clearly voltage-gated. Otherwise, the channel requires a certain voltage threshold to open and is, to some degree, voltage-gated. In cases where the I/V-curve is not linear, the channel is considered to be a rectifier, i.e., membrane potential modulates its conductance.

If the current saturates (does not increase with tension after certain tension value is reached) one may wish to evaluate the channel’s midpoint pressure, the pressure at which a half of the channel population is open, or its threshold tension, the tension at which the very first channel of the population opens. These are distinctive features of a mechanosensitive channel and generally speaking, characterize its tension sensitivity. It should be noted though, that these are statistical values, and several measurements under the same conditions (including membrane patch size) must be carried out in order to obtain an average value and standard deviation. Of course, patches containing more channels produce more reliable values. In our hands, oocytes can survive pressures as high as −160 mmHg with pipettes with BN 4–5, which is enough to reach saturation for MscS [17]. However, the oocyte membrane seems to be more fragile than the membranes of giant E. coli spheroplasts previously used for characterization of MscS [14].

As channels may be distributed over the oocyte surface nonuniformly, several patches may be necessary to find them. Usually 3–4 patches per oocyte are enough to make sure that the oocyte is or is not expressing MSCs. Patching 4–5 oocytes from 2 batches isolated from different frogs should give reliable data on a particular channel’s presence and properties. For beginning stages of an investigation, we can also recommend expressing a previously characterized channel (like MscS, see ref. 17) for an introduction to the method and a positive control. Co-expression of the channel of interest with MscS as an internal standard may be also very useful.

Recorded traces may be later processed using either dedicated software (e.g., Clampfit, Molecular Devices) or a number of third party suites. Typical procedures include data filtering at 0.5–2 kHz, which reduces noise level but may eliminate fast events, and slight baseline correction. After that one may proceed to a statistical analysis of the events in a trace, including single channel current amplitudes, threshold and midpoint pressures, dwell time in open or closed states, and so on. Typically dedicated software suites provide a wide set of tools for initial data analysis. For more specific aims one may be interested in using such software suites as Origin (http://originlab.com), QtiPlot (http://www.qtiplot.ro) or QuB (http://www.qub.buffalo.edu).

References

- 1.Hilf RJC, Bertozzi C, Zimmermann I, et al. Structural basis of open channel block in a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(11):1330–1337. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schroeder JI. Heterologous expression and functional analysis of higher plant transport proteins in Xenopus oocytes. Methods. 1994;6:70–81. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller AJ, Zhou JJ. Xenopus oocytes as an expression system for plant transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1465:343–358. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maroto R, Raso A, Wood TJ, et al. TRPC1 forms the stretch-activated cation channel in vertebrate cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(2):179–185. doi: 10.1038/ncb1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zwart R, Vijverberg HP. Four pharmacologically distinct subtypes of a4b2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:1124–1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karim N, Wellendorph P, Absalom N, et al. Potency of GABA at human recombinant GABAA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes: a mini review. Amino Acids. 2013;44:1139–1149. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1456-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurdon JB, Lane CD, Woodland HR, et al. Use of frog eggs and oocytes for the study of messenger RNA and its translation in living cells. Nature. 1971;233:177–182. doi: 10.1038/233177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terhag J, Cavara NA, Hollmann M. Cave Canalem: how endogenous ion channels may interfere with heterologous expression in Xenopus oocytes. Methods. 2010;51:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nutt LK. The Xenopus oocyte: a model for studying the metabolic regulation of cancer cell death. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:412–418. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Englund UH, Gertow J, Kågedal K, et al. A voltage dependent non-inactivating Na+ channel activated during apoptosis in Xenopus oocytes. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sommerville J. Using oocyte nuclei for studies on chromatin structure and gene expression. Methods. 2010;51:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stick R, Goldberg MW. Oocytes as an experimental system to analyze the ultrastructure of endogenous and ectopically expressed nuclear envelope components by field-emission scanning electron microscopy. Methods. 2010;51:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown DD. A tribute to the Xenopus laevis oocyte and egg. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(44):45291–45299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.X400008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naismith JH, Booth IR. Bacterial mechanosensitive channels—MscS: evolution’s solution to creating sensitivity in function. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:157–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-101211-113227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kloda A, Petrov E, Meyer GR, et al. Mechanosensitive channel of large conductance. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel A, Sharif-Naeini R, Folgering JR, et al. Canonical TRP channels and mechanotransduction: from physiology to disease states. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460:571–581. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maksaev G, Haswell ES. Expression and characterization of the bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscS in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2011;138(6):641–649. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maksaev G, Haswell ES. MscS-like10 is a stretch-activated ion channel from Arabidopsis thaliana with a preference for anions. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:19015–19020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213931109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang XC, Sachs F. Characterization of stretch-activated ion channels in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1990;431:103–122. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Gao F, Popov VL, et al. Mechanically gated channel activity in cytoskeleton-deficient plasma membrane blebs and vesicles from Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 2000;523(1):117–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang XC, Sachs F. Block of stretchactivated ion channels in Xenopus oocytes by gadolinium and calcium ions. Science. 1989;243:1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.2466333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu G, McBride DW, Jr, Hamill OP. Mg2+ block and inward rectification of mechanosensitive channels in Xenopus oocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1997;435:572–574. doi: 10.1007/s004240050554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delpire E, Gagnon KB, Ledford JJ, et al. Housing and husbandry of Xenopus laevis affect the quality of oocytes for heterologous expression studies. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2011;50(1):46–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King ML, Messitt TJ, Mowry KL. Putting RNAs in the right place at the right time: RNA localization in the frog oocyte. Biol Cell. 2005;97:19–33. doi: 10.1042/BC20040067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobczak K, Bangel-Ruland N, Leier G, et al. Endogenous transport systems in the Xenopus laevis oocyte plasma membrane. Methods. 2010;51:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldin AL. Expression of ion channels in Xenopus oocytes. In: Clare JJ, Trezise DJ, editors. Expression and analysis of recombinant ion channels. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KgaA; Weinheim: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sigel E, Minier F. The Xenopus oocyte: system for the study of functional expression and modulation of proteins. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49:228–234. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soreq H, Seidman S. Xenopus oocyte microinjection: from gene to protein. Methods Enzymol. 1992;207:225–265. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papke RL, Smith-Maxwell K. Highthroughput electrophysiology with Xenopus oocytes. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2009;12(1):38–50. doi: 10.2174/138620709787047975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musa-Aziz R, Boron WF, Parker MD. Using fluorometry and ion-sensitive microelectrodes to study the functional expression of heterologously-expressed ion channels and transporters in Xenopus oocytes. Methods. 2010;51:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dargan SL, Demuro A, Parker I. Imaging Ca2+ signals in Xenopus oocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;322:103–119. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-000-3_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tammaro P, Shimomura K, Proks P. Xenopus oocytes as a heterologous expression system for studying ion channels with the patch-clamp technique. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;491:127–139. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-526-8_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stűhmer W. Electrophysiological recor dings from Xenopus oocytes. Methods Enzymol. 1992;207:317–339. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07021-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colman A. Translation of eucaryotic messenger RNA in Xenopus oocytes. In: Hames BD, Higgins SJ, editors. Transcription and translation: a practical approach. IRL Press; Oxford: 1984. Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigma-Aldrich. Product information. http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/content/dam/sigma-aldrich/docs/Sigma/Product_Information_Sheet/c0130pis.pdf. Accessed 05 June 2014.

- 36.Dumont JN. Oogenesis in Xenopus laevis (Daudin). I. Stages of oocyte development in laboratory maintained animals. J Morphol. 1972;136:153–179. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051360203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ludewig U, von Wirén N, Frommer WB. Uniport of NH4+ by the root hair plasma membrane ammonium transporter LeAMT1;1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(16):13548–13555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnorf M, Potrykus I, Neuhaus G. Microinjection technique: routine system for characterization of microcapillaries by bubble pressure measurement. Exp Cell Res. 1994;210:260–267. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warner Instrument Corporation. Chloriding silver wire, Rev 9.1.99. http://www.warnerinstrument.com/pdf/whitepapers/chloriding_wire.pdf. Accessed 05 June 2014.

- 40.Dixit R, Rizzo C, Nasrallah M, et al. The Brassica MIP-MOD gene encodes a functional water channel that is expressed in the stigma epidermis. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;45:51–62. doi: 10.1023/a:1006428007826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warner Instrument Corporation. Salt bridge formation, Rev 9.1.99. http://www.warneronline.com/pdf/whitepapers/agar_bridges.pdf. Accessed 05 June 2014.

- 42.Ermakov YA, Kamaraju K, Sengupta K, et al. Gadolinium ions block mechanosensitive channels by altering the packing and lateral pressure of anionic lipids. Biophys J. 2010;98(6):1018–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Armstrong CM. Interaction of tetraethylammonium ion derivatives with the potassium channels of giant axons. J Gen Physiol. 1971;58:413–437. doi: 10.1085/jgp.58.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]