Abstract

The μ-opioid receptor (MOR) system, well known for dampening physical pain, is also hypothesized to dampen “social pain.” We used positron emission tomography scanning with the selective MOR radioligand [11C]carfentanil to test the hypothesis that MOR system activation in response to social rejection and acceptance is altered in medication-free patients diagnosed with current major depressive disorder (MDD, n = 17) compared to healthy controls (HCs, n = 18). During rejection, MDD patients showed reduced MOR activation (e.g., reduced endogenous opioid release) in brain regions regulating stress, mood, and motivation, and slower emotional recovery compared to HCs. During acceptance, only HCs showed increased social motivation, which was positively correlated with MOR activation in the nucleus accumbens, a reward structure. Abnormal MOR function in MDD may hinder emotional recovery from negative social interactions and decrease pleasure derived from positive interactions. Both effects may reinforce depression, trigger relapse, and contribute to poor treatment outcomes.

Keywords: depression, mu, opioid, PET, social, rejection, acceptance, stress

INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD) often develops in the context of negative social environments including childhood abuse and neglect1,2, adolescent peer victimization3,4, and romantic break-ups5,6. In particular, rejection-related stressors have been shown to be among the best predictors of MDD compared to other types of stressors5–10. One reason why rejection may be particularly depressogenic is that devaluation of the self by others, real or perceived, leads directly to low self-esteem11,12, a causal factor for MDD13,14. Once MDD develops, poor emotional regulation during rejection can continue to reinforce symptoms, contributing to the maintenance of MDD15,16. Furthermore, in MDD reduced pleasure from social interactions can contribute to withdrawal, reduced social support, and the persistence of a depressive episode15,17,18.

Endogenous opioid peptides acting at μ-opioid receptors (MORs) have been shown in animal models to both alleviate distress behaviors following social separation19–23, and promote social play behaviors in the presence of conspecifics24–28. Our recent study in healthy humans demonstrated that social rejection activated the MOR system in structures involved in mood and motivation including the amygdala, thalamus, and ventral striatum29. This pattern of MOR activation was similar to that during physical pain29,30, supporting the theory that emotional “hurt” during rejection is regulated by opioid pathways for physical pain31,32. In addition, during social acceptance MOR activation in the ventral striatum was correlated with increased social motivation29, supporting the theory that social rewards are regulated by opioid pathways27,33.

The present study examined the function of the MOR system in response to social rejection and acceptance in patients with MDD, compared to a matched sample of healthy controls (HCs). Given the adaptive role of the opioid system in reducing social distress and promoting social motivation, we hypothesized that MDD patients would show deficient MOR activation during rejection and acceptance, with associated alterations in behavior and levels of the stress hormone cortisol. We tested this hypothesis using a salient, ecologically-relevant task for social rejection and acceptance during positron emission tomography (PET) scanning with the selective MOR radioligand [11C]carfentanil.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Participants were 18 HCs from a previous study29 and 17 patients with current MDD, recruited through local advertisements. HCs and MDD patients were group-matched for gender, age, education, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and relationship status (Supplementary Table 1, P’s > 0.05). HCs were free of psychiatric disorders as assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) for non-patients, version 2.0. Patients were diagnosed with current MDD using the SCID-I for patients, version 2.0, were free of psychotropic medication for at least six months at the time of the study, and had moderate to severe depression (mean score ± SD for 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, 18.5 ± 5.6). No subjects were taking hormones or hormonal contraception in the three months prior to study. Phase of menstrual cycle was not controlled – hormonal fluctuations may impact sensitivity to social rejection, but MOR binding potential in vivo is not influenced by phase in the menstrual cycle34. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan Medical School, and written informed consent was obtained.

Social Feedback Task

The social feedback task with PET has been previously described29 (Supplementary Methods). After each feedback trial participants rated how “sad,” “rejected,” “happy,” and “accepted” they felt. The scores for “sad” and “rejected,” and “happy” and “accepted” during each trial were averaged for analysis. Word order was randomized in each trial. After each block, subjects completed the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale35, the Desire for Social Interaction Scale29, and again rated how “sad,” “rejected,” “happy,” and “accepted” they felt. All items were presented on a personal computer, and responses were obtained using a five-button response box. Scores for Ego Resiliency36, a trait for successful psychological adjustment37, were obtained prior to scanning. Planned two-tailed t-tests were performed to compare changes in ratings within subjects (paired analysis) and between groups.

PET and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Acquisition and reconstruction of PET images, quantification of binding potential, and co-registration with structural MRs have been previously described29 (Supplementary Methods).

Image Data Analysis

A priori volumes of interest (VOIs) included structures that are rich in MORs, respond to social rejection and/or physical pain29–31,38,39 and were identical to those in a previous study29 (Supplementary Methods). “MOR activation” was defined as the reduction in MOR binding potential from baseline to rejection or acceptance block (i.e., baseline-rejection, baseline-acceptance). This metric represents competition between radiotracer and endogenous opioids, changes in the conformational state of the receptor after activation, and/or changes in receptor concentration (e.g., via internalization, trafficking), all of which are related to endogenous opioid neurotransmission40,41.

Blood Collection and Plasma Cortisol Analysis

All scans were conducted in the afternoon (1:30pm – 5:00pm), when cortisol levels are more stable and approaching their nadir. Blood samples were collected from an indwelling venous catheter every 10 min for a total of 10 samples per scan (0–90 min). Samples were collected on ice and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Plasma was collected and stored at μ80°C until assay. Samples were not collected in four HCs and three MDD patients due to failed venous access, leaving a total of fourteen subjects in each group for cortisol analysis.

Plasma cortisol assays were performed using IMMULITE 1000 (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostic Division), a solid-phase competitive chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay system. Intra- and inter-assay variabilities were < 8%. Areas under the curve (AUCs) were calculated for the last 4 time points (of 5 total) in each block in order to minimize potential carryover effects from the previous block. Planned two-tailed t-tests were performed to compare changes in AUCs within subjects (paired analysis) and between groups.

RESULTS

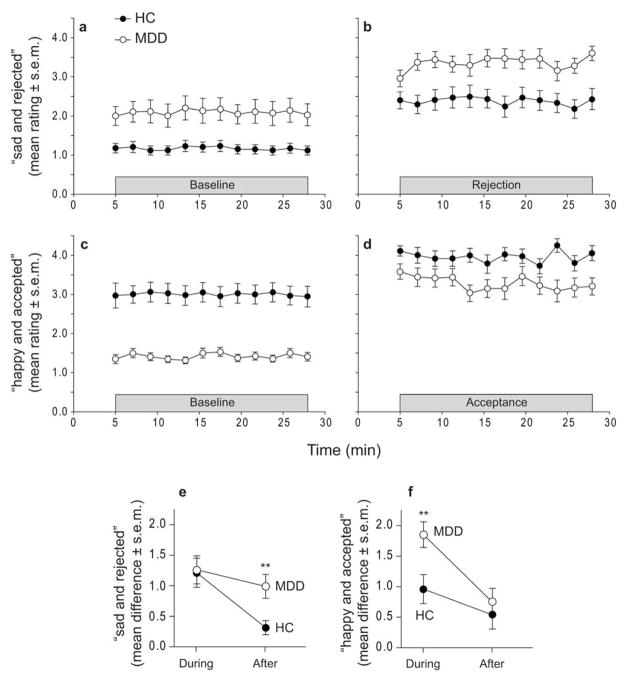

HCs and MDD patients reported feeling more “sad and rejected” during rejection relative to baseline (HC, t16 = 5.11, P = 0.0001; MDD, t16 = 5.47, P = 0.00005); these increases were not statistically different between groups (Fig. 1a,b, Supplementary Table 2). During acceptance, both groups reported feeling more “happy and accepted” (HC, t16 = 3.71, P = 0.002; MDD, t15 = 8.89, P < 0.0001); these increases were greater in MDD patients compared to HCs (t32 = 2.79, P = 0.009) (Fig. 1c,d, Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1. Changes in affect during PET scans.

Ratings for “sad and rejected” during (a) baseline and (b) rejection. Ratings for “happy and accepted” during (c) baseline and (d) acceptance. (e) Ratings for “sad and rejected” during rejection relative to baseline (trial ratings averaged), and measured again after each block. f) Ratings for “happy and accepted” during acceptance relative to baseline (trial ratings averaged), and measured again after each block. ** P < 0.01, two-tailed t-test (HC vs. MDD)

After rejection, MDDs but not HCs reported a significant decrease in self-esteem (MDD, t16 = 2.51, P = 0.02). In addition, after rejection both groups reported a significant decrease in desire for social interaction (HC, t16 = 2.14, P = 0.048; MDD, t16 = 5.38, P = 0.00006); these decreases were not statistically different between groups (Supplementary Table 2). After acceptance, HCs but not MDD patients reported an increase in self-esteem (HCs, t15 = 2.16, P = 0.048) and desire for social interaction (HCs, t15 = 2.91, P = 0.01) (Supplementary Table 2).

Ratings for “sad and rejected” were measured again five minutes after the last rejection trial, indicating how quickly their ratings returned toward baseline. At that time point, HCs returned toward baseline levels whereas MDD patients remained elevated (t31 = 3.02, P = 0.005) (Fig. 1e). Ratings for “happy and accepted” were also measured five minutes after the last acceptance trial. At this time point, both HCs and MDD patients returned toward baseline levels (Fig. 1f).

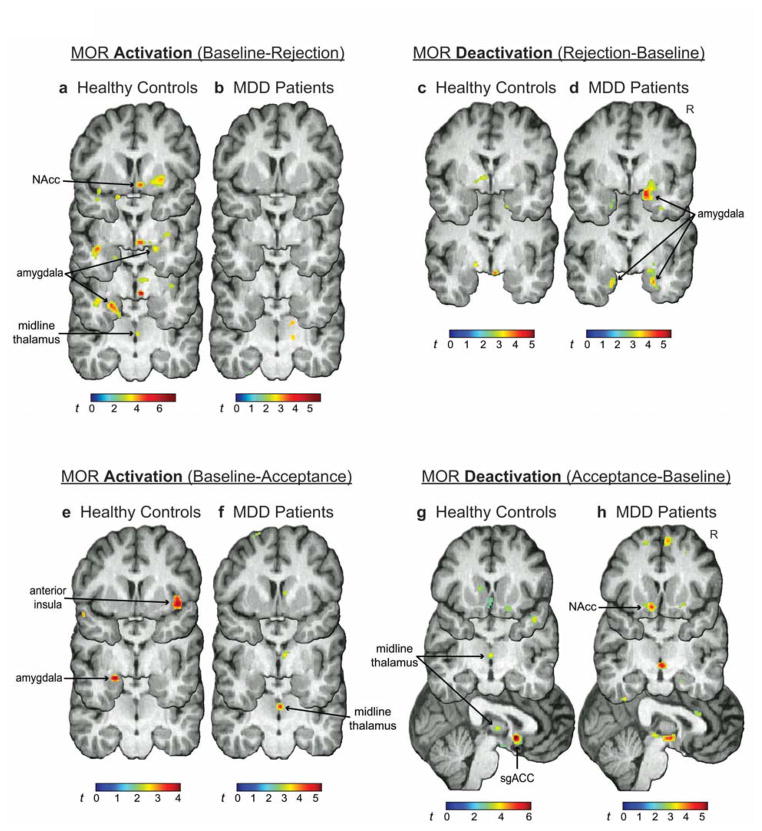

During rejection, MOR activation was significant in the right nucleus accumbens (NAcc), left and right amygdala, midline thalamus, and periaqueductal gray (PAG) in HCs. Significant activation was not found in MDD patients (Fig. 2a,b, Table 1). MOR deactivation was not found in HCs, but was significant in the left and right amygdala in MDD patients (Fig. 2c,d, Table 1). Expected patterns of MOR activation were obtained from group comparisons (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 2. MOR activation/deactivation.

MOR activation during rejection in (a) HCs and (b) MDD patients, and deactivation during rejection in (c) HCs and (d) MDD patients. MOR activation during acceptance in (e) HCs and (f) MDD patients, and deactivation in (g) HCs and (h) MDD patients. For all images, contrast t maps are rendered onto a template brain in MNI space. Display threshold: P < 0.01, uncorrected. NAcc, nucleus accumbens; sgACC, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex; R, right

Table 1. MOR activation/deactivation during rejection and acceptance: within-group analyses.

Locations of peaks shown in x, y, z coordinates (mm) in MNI space.

| VOI | MOR Activation (Baseline – Rejection) | MOR Deactivation (Rejection – Baseline) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| HC | MDD | HC | MDD | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Peak | t | Peak | t | Peak | t | Peak | t | |

|

| ||||||||

| NAcc (R) | 16, 12, −6 | 3.90* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Amygdala (L) | −26, −4, −23 | 4.53** | -- | -- | -- | -- | −20, −3, −27 | 3.61* |

| Amygdala (R) | 23, 2, −17 | 3.62* | -- | -- | -- | -- | 16, 3, −18 | 5.45** |

| Midline Thalamus | 3, −18, 6 | 3.68** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| PAG | 0, −33, −12 | 2.30* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

|

| ||||||||

| MOR Activation (Baseline – Acceptance) | MOR Deactivation (Acceptance – Baseline) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| NAcc (L) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −10, 15, −12 | 4.26** |

| Amygdala (L) | −22, −3, −17 | 3.91* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Midline Thalamus | -- | -- | 2, −16, 9 | 4.18** | 0, −12, 4 | 3.83** | -- | -- |

| Anterior Insula (R) | 44, 8, −6 | 3.91* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| sgACC | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0, 9, −6 | 6.09*** | -- | -- |

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001, small volume correction.

Dashes indicate no clusters detected at P < 0.05. Significant MOR activation/deactivation were not found in the left anterior insula, dACC, or pgACC. VOI, volume of interest; MOR, μ-opioid receptor; HC, healthy control; MDD, major depressive disorder; NAcc, nucleus accumbens; PAG, periaqueductal gray; sgACC, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex; L, left; R, right

During acceptance, MOR activation was significant in the right anterior insula and left amygdala in HCs (Fig. 2e, Table 1), and in the midline thalamus in MDD patients (Fig. 2f, Table 1). MOR deactivation was significant in the midline thalamus and subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC) in HCs (Fig. 2g, Table 1), and in the left NAcc in MDD patients (Fig. 2h, Table 1). Expected patterns of MOR activation were obtained from group comparisons (Supplementary Table 3).

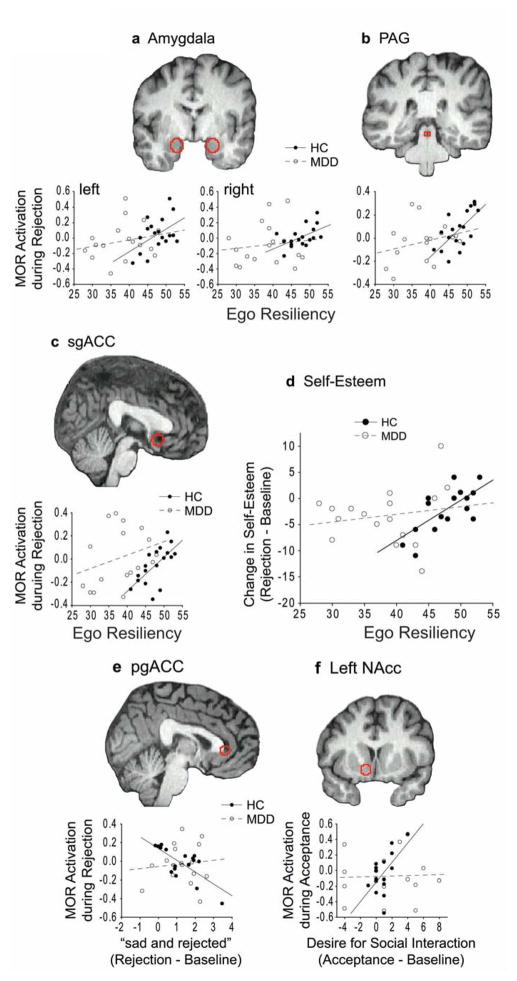

Ego Resiliency ratings were higher in HCs compared to MDD patients (t33 = 5.52, P = 4 × 10−6), and were positively correlated with MOR activation during rejection in the amygdala (left, r = 0.48, P = 0.04; right, r = 0.54, P = 0.02), PAG (r = 0.66, P = 0.003), and sgACC (r = 0.65, P = 0.003) in HCs but not MDD patients (Fig. 3a–c). In HCs, those with higher Ego Resiliency had smaller reductions in self-esteem following rejection (r = 0.67, P = 0.003). This relationship was not found in MDD patients (Fig. 3d). During acceptance, no significant correlations were found between Ego Resiliency and MOR activation or changes in self-esteem in HCs or MDD patients (P’s > 0.24).

Figure 3. Trait Ego Resiliency and state changes.

Ego Resiliency ratings vs. MOR activation during rejection in VOIs (red outlines) in the a) amygdala, b) PAG, and c) sgACC. d) Ego Resiliency vs. changes in self-esteem during rejection. e) Ratings for “sad and rejected” vs. MOR activation in the pgACC during rejection. f) Ratings for the desire for social interaction vs. MOR activation in the left NAcc during acceptance. PAG, periaqueductal gray; sgACC, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex; pgACC, pregenual anterior cingulate cortex; NAcc, nucleus accumbens

Ratings for “sad and rejected” during rejection relative to baseline were negatively correlated with MOR activation in the pgACC in HCs (r = −0.73, P < 0.001), but not MDD patients (P = 0.69) (Fig. 3e). Increased desire for social interaction was positively correlated with MOR activation in the left NAcc following acceptance in HCs (r = 0.60, P = 0.01) but not MDD patients (Fig. 3f).

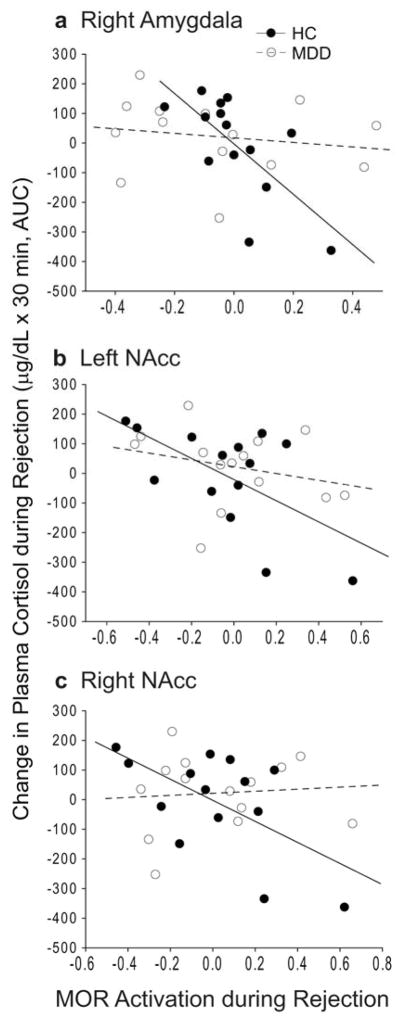

Plasma cortisol levels were not statistically different between rejection or acceptance relative to baseline in either HCs or MDD patients, and no group differences were found (Supplementary Table 2). In HCs but not MDD patients, MOR activation was negatively correlated with cortisol changes during rejection. This relationship was found in the right amygdala (r = −0.69, P = 0.006), and NAcc (left, r = −0.60, P = 0.02; right, r = −0.59, P = 0.03) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. MOR activation vs. plasma cortisol.

MOR activation during rejection vs. plasma cortisol levels in the a) right amygdala, b) left NAcc, and c) right NAcc. NAcc, nucleus accumbens; AUC, area under the curve

DISCUSSION

Altered endogenous opioid activity may be a mechanism for impaired emotion regulation during social rejection and acceptance in MDD. Despite strong, sustained negative affect during rejection in both groups, MOR activation in multiple brain regions was found only in HCs, whereas MDD patients showed MOR deactivation in the amygdala and slower emotional recovery from rejection. During acceptance, both groups reported increased positive affect, with MDD patients showing greater increases from baseline compared to HCs. However, this increase returned rapidly toward baseline after acceptance trials had ended. In MDD patients, MOR deactivation during acceptance was found in the NAcc, a reward structure. MOR activation in the NAcc in HCs but not MDD patients was positively correlated with increases in the desire for social interaction, suggesting opioid involvement in the motivation to seek out positive social interaction during acceptance in HCs, but not MDD patients.

During social rejection, MDD patients did not show significant activation in VOIs, whereas in HCs, MOR activation was found in the right NAcc, left and right amygdala, midline thalamus, and PAG (Fig. 2a,b, Table 1), as previously described29. These structures are high in MOR concentrations and part of a pathway by which stressors can influence mood and motivation42; thus, MOR activation in these structures may reduce the negative impact of stressors. In contrast, MDD patients showed MOR deactivation in the amygdala (Fig. 2c), which may contribute to blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) hyperactivity in the amygdala in MDD patients in response to negative social cues such as peer rejection43. The present study also found a strong negative correlation between MOR activation in the pgACC, an area involved in emotion regulation44, and increased ratings of negative affect during rejection in HCs but not in MDD patients (Fig. 3e). Similarly, previous studies found a strong negative correlation between MOR activation in the pgACC and increased ratings of negative affect during self-induced sadness in HCs40 but not MDD patients45. Thus, in MDD an absence of MOR activation plus greater MOR deactivation in the amygdala, and the lack of relationship between MOR activation in the pgACC and negative affect may contribute to sustained negative affect after rejection.

Ego Resiliency is a trait conceptualized by Block36 as the ability to psychologically adapt across situations, and has been shown to correlate with faster emotional and physiological recovery from threat37. Consistent with this concept, levels of Ego Resiliency were positively correlated with MOR activation in the amygdala, PAG, and sgACC in HCs during rejection, as previously described29. This relationship was not found in any VOI in MDD patients (Fig. 3a–c), possibly due to significantly lower Ego Resiliency ratings in MDD patients. The positive relationship between Ego Resiliency and MOR activation in HCs suggests that MOR activation during rejection is protective or adaptive. This hypothesis is consistent with the finding that Ego Resiliency was positively correlated with changes in self-esteem in HCs but not MDD patients during rejection (Fig. 3d). Path analyses in a larger sample size may test the hypothesis that MOR activation mediates the relationship between Ego Resiliency and changes in self-esteem during rejection.

As with social rejection, there were marked differences between groups during social acceptance, including MOR activation/deactivation, changes in affect, and relationships between those measures. HCs showed activation in the left anterior insula and right amygdala, and deactivation in the midline thalamus and sgACC, whereas MDD patients showed activation in the midline thalamus and deactivation in the left NAcc (Fig. 2e–h). In HCs, this pattern of MOR activation is consistent with increased MOR activation in the anterior insula following amphetamine administration46 and in the amygdala during an amusing video clip47, suggesting that MOR activation in these areas is related to positive affect. Also in HCs, MOR deactivation during acceptance in the midline thalamus and sgACC, both of which project heavily to the NAcc42,48, is a possible mechanism for facilitating positive affect. In rats, a MOR agonist injected into the medial thalamus raised the threshold for both pain and reward49. Similarly, MOR deactivation in the sgACC may facilitate increased NAcc activity when one is liked50. In contrast, MDD patients showed MOR activation in the midline thalamus, which may impede sustained positive affect. MDD patients also did not show MOR deactivation in the sgACC, a region shown to be functionally associated with anhedonia51,52. Unexpectedly, MDD patients reported a greater increase in positive affect relative to baseline during acceptance compared to HCs, however this increase was short-lived (Fig. 1f), consistent with a recent study showing that MDD patients can indeed experience positive affect, but with a shorter duration compared to HCs53. Moreover, only HCs showed significant increases in self-esteem and the desire for social interaction after acceptance (Supplementary Table 2). Thus, in response to social acceptance MDD patients showed short-lived increases in positive affect that did not significantly increase self-esteem or social motivation.

As previously reported in HCs, increased MOR activation in the NAcc was positively correlated with an increased desire for social interaction29, a finding consistent with a report in rats showing that MORs in the NAcc mediate social play behavior28. The present study showed that after acceptance, HCs but not MDD patients reported a greater desire for social interaction, and that MOR activation in the left NAcc was positively correlated with increased desire for social interaction (Fig. 3f). In contrast, MDD patients showed MOR deactivation in the left NAcc, which may contribute to abnormal NAcc activity related to anhedonia in MDD patients54. Thus, in addition to having short-lived positive affect, MDD patients did not show increased social motivation, which in HCs was related to MOR activation in the NAcc.

There were no significant differences in plasma cortisol levels between rejection or acceptance relative to baseline within groups, and no differences were found between groups. In HCs a significant negative correlation was found between MOR activation in the amygdala and NAcc and changes in cortisol levels during rejection, suggesting top-down MOR regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Previous studies suggest that the MOR system plays a role in dampening stress-induced HPA axis activity by inhibiting corticotropin-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus55,56. Consistent with the hypothesis, MOR activation in the right amygdala was negatively correlated with cortisol levels during rejection (Fig. 4a). Thus, MOR regulation of amygdala activity during rejection may dampen HPA axis activity, most likely through projections to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, which in turn projects to the hypothalamus57. MOR activation in the NAcc was also negatively correlated with cortisol (Fig. 4b,c), although the pathway from the NAcc to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus is less clear and likely involves multisynaptic pathways. The inhibitory influence of MOR activation on cortisol levels has also been reported in HCs during placebo administration for pain58. Thus, MOR activation may dampen HPA activity during rejection, a mechanism impaired in MDD by the lack of MOR activation and/or the uncoupling of the MOR system and HPA axis.

In HCs, the pattern of MOR activation during rejection was similar to that found during physical pain30,59, supporting the theory that the regulation of social rejection and physical pain share overlapping neural pathways29,31,32,38,39,60–62. In contrast to the present findings, previous studies found opposite patterns of MOR activity in HCs and MDD patients during recall of a sad autobiographical event (e.g., death of a friend or family member, romantic breakups or divorce). These studies found MOR deactivation in HCs (pgACC, ventral pallidum, amygdala, and inferior temporal cortex)40, and MOR activation in MDD patients (anterior insula, thalamus, ventral basal ganglia, and periamygdalar cortex)45. It is likely that different patterns of MOR activation are involved in responding to exteroceptive cues (i.e., pain, rejection) versus permissive, interoceptive cues (i.e., self-induced sadness). For example, in fMRI studies where subjects viewed a photo of a romantic ex-partner (exteroceptive cue), increased BOLD signal was found in the ventral striatum, thalamus, anterior insula, and ACC38,63. In contrast, recalling sad thoughts about a recent romantic breakup (interoceptive cue) resulted in deactivation in similar areas64.

The present study supports previous work in animal models and has the potential to translate into clinical applications. Interestingly, one of the earliest studies to show evidence for endogenous opioid release during social interactions was found in rats using subtractive autoradiography65, a method with conceptual similarities to the neuroimaging method used in the present study. This and other animal studies19–28 along with the present study in humans suggest that the endogenous opioids serve similar roles in social behavior across several species, supporting future translational work. For example, animal studies may provide more detailed analysis of the genetic substrates causing altered MOR function in the social environment. Indeed, a functional variation of the MOR gene has been shown in humans to be associated with the dispositional and neural sensitivity to social rejection31, and may be useful in the early detection of vulnerability to MDD in the social environment. In summary, the present study supports further investigation of the interaction between the endogenous opioid system, social environment, and pathophysiology and maintenance of MDD.

Conclusions

MDD patients showed a lack of regional activation as well as a greater deactivation of the MOR system during social rejection and acceptance. This may be a mechanism for slower/incomplete recovery from rejection and poorly sustained engagement in positive social interactions. Future studies will need to replicate these results and examine the causal relationship between these alterations and MDD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Health grants K01 MH085035 (DTH), K23 MH074459 (SAL), R01 DA022520 and R01 DA027494 (JKZ), a Brain & Behavior Research Foundation Young Investigator Award (DTH), Rachel Upjohn Clinical Scholars Award (DTH), pilot grants from the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research (DTH), and the Phil F. Jenkins Foundation (JKZ). We thank the Nuclear Medicine technologists for performing the PET scans, Ramin Ranjbar for performing the cortisol assays, and Dr. Audrey Seasholtz for analysis support of cortisol assays (University of Michigan).

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at Molecular Psychiatry’s website.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. RAK is a consultant for Avid Corp., Merck, and Johnson & Johnson; Dr. BJM received salary support from St. Jude Medical for research unrelated to this manuscript. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:49–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Pariante CM, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:1135–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nolan SA, Flynn C, Garber J. Prospective relations between rejection and depression in young adolescents. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:745–755. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witvliet M, Brendgen M, van Lier PAC, Koot HM, Vitaro F. Early adolescent depressive symptoms: prediction from clique isolation, loneliness, and perceived social acceptance. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:1045–1056. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9426-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monroe SM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn PM. Life events and depression in adolescence: relationship loss as a prospective risk factor for first onset of major depressive disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:606–614. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller PD, Matthew, Neale PD, Michael, Kendler MD, Kenneth Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1521–1529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown GW, Harris TO, Hepworth C. Loss, humiliation and entrapment among women developing depression: a patient and non-patient comparison. Psychol Med. 1995;25:7–21. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002804x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammen C. Adolescent depression: stressful interpersonal contexts and risk for recurrence. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:200–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slavich GM, Thornton T, Torres LD, Monroe SM, Gotlib IH. Targeted rejection predicts hastened onset of major depression. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2009;28:223–243. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2009.28.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leary MR, Tambor ES, Terdal SK, Downs DL. Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: the sociometer hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;68:518–530. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenberger NI, Inagaki TK, Muscatell KA, Byrne Haltom KE, Leary MR. The neural sociometer: brain mechanisms underlying state self-esteem. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011;23:3448–3455. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck AT. Depression: causes and treatment. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:213–240. doi: 10.1037/a0028931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joiner TE, Coyne JC. The interactional nature of depression: advances in interpersonal approaches. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, USA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lara ME, Klein DN. Psychosocial processes underlying the maintenance and persistence of depression: implications for understanding chronic depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 1999;19:553–570. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fredman L, Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Bruce ML. Social functioning in community residents with depression and other psychiatric disorders: results of the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. J Affect Disord. 1988;15:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joiner TE, Jr, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. The core of loneliness: lack of pleasurable engagement--more so than painful disconnection--predicts social impairment, depression onset, and recovery from depressive disorders among adolescents. J Pers Assess. 2002;79:472–491. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7903_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson EE, Panksepp J. Brain substrates of infant-mother attachment: contributions of opioids, oxytocin, and norepinephrine. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;22:437–452. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panksepp J, Herman BH, Vilberg T, Bishop P, DeEskinazi FG. Endogenous opioids and social behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1980;4:473–487. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(80)90036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herman BH, Panksepp J. Ascending endorphin inhibition of distress vocalization. Science. 1981;211:1060–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.7466377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Barksdale CM. Opiate modulation of separation-induced distress in non-human primates. Brain Res. 1988;440:285–292. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90997-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Lynn DE. Opiate systems in mother and infant primates coordinate intimate contact during reunion. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:735–742. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beatty WW, Costello KB. Naloxone and play fighting in juvenile rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;17:905–907. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegel MA, Jensen RA, Panksepp J. The prolonged effects of naloxone on play behavior and feeding in the rat. Behav Neural Biol. 1985;44:509–514. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(85)91024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanderschuren LJ, Niesink RJ, Spruijt BM, Van Ree JM. Mu- and kappa-opioid receptor-mediated opioid effects on social play in juvenile rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;276:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00040-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trezza V, Baarendse PJJ, Vanderschuren LJMJ. The pleasures of play: pharmacological insights into social reward mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trezza V, Damsteegt R, Achterberg EJM, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Nucleus accumbens μ-opioid receptors mediate social reward. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6362–6370. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5492-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu DT, Sanford BJ, Meyers KK, Love TM, Hazlett KE, Wang H, et al. Response of the μ-opioid system to social rejection and acceptance. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:1211–1217. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zubieta JK, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu Y, Kilbourn MR, Jewett DM, et al. Regional mu opioid receptor regulation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Science. 2001;293:311–315. doi: 10.1126/science.1060952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Way BM, Taylor SE, Eisenberger NI. Variation in the mu-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) is associated with dispositional and neural sensitivity to social rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15079–15084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812612106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eisenberger NI. The pain of social disconnection: examining the shared neural underpinnings of physical and social pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:421–434. doi: 10.1038/nrn3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chelnokova O, Laeng B, Eikemo M, Riegels J, Løseth G, Maurud H, et al. Rewards of beauty: the opioid system mediates social motivation in humans. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:746–747. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith YR, Zubieta JK, del Carmen MG, Dannals RF, Ravert HT, Zacur HA, et al. Brain opioid receptor measurements by positron emission tomography in normal cycling women: relationship to luteinizing hormone pulsatility and gonadal steroid hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:4498–4505. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.12.5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Block J. The challenge of response sets: unconfounding meaning, acquiesence, and social desirability in the MMPI. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York, NY, USA: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prince-Embury S. Resilience in children, adolescents, and adults: translating research into practice. Springer Science + Business Media; New York, NY: 2013. The ego-resiliency scale by Block and Kremen (1996) and trait ego-resiliency; pp. 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kross E, Berman MG, Mischel W, Smith EE, Wager TD. Social rejection shares somatosensory representations with physical pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6270–6275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102693108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dewall CN, Macdonald G, Webster GD, Masten CL, Baumeister RF, Powell C, et al. Acetaminophen reduces social pain: behavioral and neural evidence. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:931–937. doi: 10.1177/0956797610374741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zubieta J-K, Ketter TA, Bueller JA, Xu Y, Kilbourn MR, Young EA, et al. Regulation of human affective responses by anterior cingulate and limbic mu-opioid neurotransmission. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1145–1153. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Narendran R, Frankle WG, Mason NS, Rabiner EA, Gunn RN, Searle GE, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in the human cortex: a comparative evaluation of the high affinity dopamine D2/3 radiotracers [11C]FLB 457 and [11C]fallypride. Synap N Y N. 2009;63:447–461. doi: 10.1002/syn.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsu DT, Kirouac GJ, Zubieta J-K, Bhatnagar S. Contributions of the paraventricular thalamic nucleus in the regulation of stress, motivation, and mood. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:73. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silk JS, Siegle GJ, Lee KH, Nelson EE, Stroud LR, Dahl RE. Increased neural response to peer rejection associated with adolescent depression and pubertal development. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1093/scan/nst175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bush, Luu, Posner Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;4:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kennedy SE, Koeppe RA, Young EA, Zubieta J-K. Dysregulation of endogenous opioid emotion regulation circuitry in major depression in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1199–1208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colasanti A, Searle GE, Long CJ, Hill SP, Reiley RR, Quelch D, et al. Endogenous opioid release in the human brain reward system induced by acute amphetamine administration. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koepp MJ, Hammers A, Lawrence AD, Asselin MC, Grasby PM, Bench CJ. Evidence for endogenous opioid release in the amygdala during positive emotion. NeuroImage. 2009;44:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferry AT, Ongür D, An X, Price JL. Prefrontal cortical projections to the striatum in macaque monkeys: evidence for an organization related to prefrontal networks. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425:447–470. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000925)425:3<447::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carr KD, Bak TH. Medial thalamic injection of opioid agonists: μ-agonist increases while κ-agonist decreases stimulus thresholds for pain and reward. Brain Res. 1988;441:173–184. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davey CG, Allen NB, Harrison BJ, Dwyer DB, Yücel M. Being liked activates primary reward and midline self-related brain regions. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:660–668. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mayberg HS, Liotti M, Brannan SK, McGinnis S, Mahurin RK, Jerabek PA, et al. Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:675–682. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pizzagalli DA, Oakes TR, Fox AS, Chung MK, Larson CL, Abercrombie HC, et al. Functional but not structural subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in melancholia. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:325, 393–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horner MS, Siegle GJ, Schwartz RM, Price RB, Haggerty AE, Collier A, et al. C’mon get happy: reduced magnitude and duration of response during a positive-affect induction in depression. Depress Anxiety. 2014:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1002/da.22244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pizzagalli DA, Holmes AJ, Dillon DG, Goetz EL, Birk JL, Bogdan R, et al. Reduced caudate and nucleus accumbens response to rewards in unmedicated individuals with major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:702–710. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson EO, Kamilaris TC, Chrousos GP, Gold PW. Mechanisms of stress: a dynamic overview of hormonal and behavioral homeostasis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16:115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drolet G, Dumont EC, Gosselin I, Kinkead R, Laforest S, Trottier JF. Role of endogenous opioid system in the regulation of the stress response. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001;25:729–741. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herman JP, Ostrander MM, Mueller NK, Figueiredo H. Limbic system mechanisms of stress regulation: hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peciña M, Azhar H, Love TM, Lu T, Fredrickson BL, Stohler CS, et al. Personality trait predictors of placebo analgesia and neurobiological correlates. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:639–646. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zubieta J-K, Bueller JA, Jackson LR, Scott DJ, Xu Y, Koeppe RA, et al. Placebo effects mediated by endogenous opioid activity on mu-opioid receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7754–7762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0439-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD. Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science. 2003;302:290–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1089134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ehnvall A, Mitchell PB, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Malhi GS, Parker G. Pain during depression and relationship to rejection sensitivity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:375–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.MacDonald G, Jensen-Campbell LA, editors. Social pain: neuropsychology and health implications of loss and exclusion. 1. American Psychological Association (APA); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fisher HE, Brown LL, Aron A, Strong G, Mashek D. Reward, addiction, and emotion regulation systems associated with rejection in love. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:51–60. doi: 10.1152/jn.00784.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Najib A, Lorberbaum JP, Kose S, Bohning DE, George MS. Regional brain activity in women grieving a romantic relationship breakup. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2245–2256. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Panksepp J, Bishop P. An autoradiographic map of (3H)diprenorphine binding in rat brain: effects of social interaction. Brain Res Bull. 1981;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(81)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.