Abstract

Na+/Cl−-coupled biogenic amine transporters are the primary targets of therapeutic and abused drugs, ranging from antidepressants to the psychostimulants cocaine and amphetamines, and to their cognate substrates. Here we determine x-ray crystal structures of the Drosophila melanogaster dopamine transporter (dDAT) bound to its substrate dopamine (DA), a substrate analogue 3,4-dichlorophenethylamine, the psychostimulants D-amphetamine, methamphetamine, or to cocaine and cocaine analogues. All ligands bind to the central binding site, located approximately halfway across the membrane bilayer, in close proximity to bound sodium and chloride ions. The central binding site recognizes three chemically distinct classes of ligands via conformational changes that accommodate varying sizes and shapes, thus illustrating molecular principles that distinguish substrates from inhibitors in biogenic amine transporters.

Introduction

Signals by the biogenic amine neurotransmitters – dopamine (DA)1, serotonin2 and noradrenaline3 -- at chemical synapses are terminated by the cognate neurotransmitter sodium symporters (NSSs)4–7. Biogenic amines play profound roles in the development and function of the nervous system, as well as in animal behavior and activity, thus NSSs are central to normal neurophysiology and are the targets of a spectrum of therapeutic and illicit agents, from antidepressants and antianxiety medications to cocaine and amphetamines8. Experimental and computational studies have shown that the DA, serotonin (SERT) and norepinephrine (NET) transporters harbor a conserved structural fold9,10, first seen in the structure of LeuT11. Due to variations in amino acid sequences12, however, the biogenic amine transporters possess distinct yet overlapping pharmacological ‘fingerprints’13.

The dopamine transporter (DAT)14 removes DA from synaptic and perisynaptic spaces, thus extinguishing its action at G-protein coupled DA receptors. To drive the vectorial ‘uphill’ movement of extracellular DA into presynaptic cells, DAT couples substrate transport to pre-existing sodium and chloride transmembrane gradients. Congruent with the multifaceted roles of DA in the nervous system, perturbation of dopaminergic signaling by disruption of native DAT function has profound consequences15–17. On the one hand, the amphetamines – potent and widely abused psychostimulants – are DAT substrates that enhance synaptic levels of DA both by competing with DA transport by DAT and by inducing the release of DA from synaptic vesicles into the cytoplasm, from where DA is then effluxed through DAT into the synaptic space18–24. On the other hand, the Erythroxylon coca leaf-derived alkaloid, cocaine, as well as synthetic cocaine derivatives are competitive inhibitors of DAT and enhance extracellular DA concentrations by locking the transporter in a transport inactive conformation14,25–27. Widely prescribed antidepressants specifically inhibit serotonin and noradrenaline uptake and typically have weaker affinities towards DAT28,29.

Mutagenesis, chemical modification, binding and transport studies have implicated the central or S1 binding site in DAT, akin to the leucine and tryptophan site in LeuT, as the binding site occupied by DA, amphetamines, cocaine and antidepressants25,26,30. Moreover, the x-ray structure of a transport-inactive Drosophila melanogaster DAT (dDAT) in complex with nortriptyline shows the antidepressant bound at the central site 9,31. Nevertheless, none of these studies have visualized the binding of DA, amphetamine or cocaine to an active DAT, nor have they illuminated distinctions in ligand pose and transporter conformation between substrates and inhibitors. Here we present x-ray structures of dDAT with substrates DA, methamphetamine or D-amphetamine, with the DA analogue 3,4-dichlorophenethylamine (DCP), and with cocaine or cocaine analogues.

Resurrection of transport activity

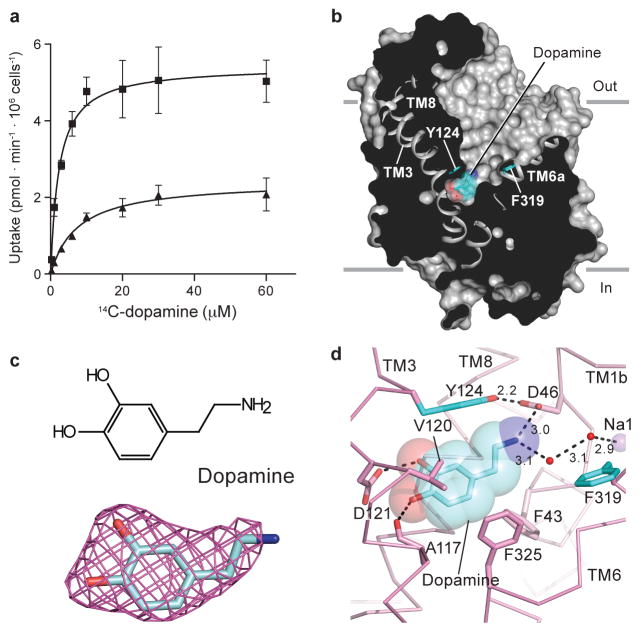

The previously reported structure of the dDAT-nortriptyline complex exploited a transport-inactive variant with five thermostabilizing mutations (dDATcryst)9. We recovered transport function yet retained favorable crystallization properties by reverting three thermostabilizing mutations (V275A, V311A, and G538L) to their wild-type identities and by shifting the deletion of extracellular loop 2 (EL2; Extended Data Fig. 1). This minimal functional construct, dDATmfc, has a melting temperature of 48 °C32, exhibits DA transport with a KM of 8.2 ± 2.3 μM and Vmax of 2.4 ± 0.2 pmol/min/106 cells, compared to wild-type dDAT (dDATwt) with a KM of 2.1 ± 0.7 μM and Vmax of 4.5 ± 0.4 pmol/min/106 cells (s.e.m., Fig. 1a). The dDATmfc construct binds nisoxetine with a Kd of 36 nM compared to a Ki of 5.6 nM for wild-type dDAT31 (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Dopamine occupies central binding site.

a, Michaelis-Menten plots of specific DA uptake by dDATwt and dDATmfc in squares and triangles, respectively. Graph depicts one representative trial of two independent experiments. Error bars represent s.d. values for individual data points measured in triplicate. b, Surface representation of the dDATmfc – DA complex viewed parallel to the membrane, with DA displayed as cyan spheres. Residues Y124 and F319 are shown as cyan sticks on the left and right sides of DA, respectively. c, Chemical structure and Fo-Fc density for DA (3.0 σ). d, Close-up view of DA in the binding pocket with hydrogen bonds shown as dashed lines. Sodium ions and water are shown as purple and red spheres, respectively.

The central binding site in DAT, NET and SERT can be divided to subsites A, B and C29,33. Subsites A and C are well conserved in dDAT versus human DAT (hDAT) whereas subsite B, a pocket sculpted by TMs 3 and 8, differs from hDAT in that residues lining this pocket in dDAT are Asp 121 and Ser 426 (Extended Data Fig. 3). We introduced mutations D121G (TM 3) and S426M (TM 8) into the dDATcryst and dDATmfc constructs to mimic hDAT subsite B33. These mutations enhanced the affinities for nisoxetine, β-CFT, and DCP (Extended Data Figs. 2, 4). While constructs harboring subsite B substitutions improved crystallization propensity, transport activity was extinguished (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Nevertheless, structures bearing these mutations were solved in complexes with cocaine, β-CFT, RTI-55, or DCP (Supplementary Table 1). In the cocaine, RTI-55 and DCP complexes, superposition of structures with subsite B mutations onto structures of dDATmfc did not reveal prominent structural changes in the binding pocket or deviations in the positions of bound ligand (Extended Data Table 1).

Dopamine bound to central binding site

The structure of dDATmfc bound to DA displays an outward-open conformation (Fig. 1b) where DA is situated in the central binding site, surrounded by TMs 1, 3, 6, and 8. The amine group points toward subsite A and interacts with the carboxylate of Asp 46 at a distance of 3 Å. The catechol group occupies a subsite B cavity sculpted by Ala 117, Val 120, Asp 121, Tyr 124, Ser 422 and Phe 325 (Fig. 1c, d), residues predicted to interact with DA using homology models of DAT based on the substrate-bound occluded state of LeuT, analysis of uptake kinetics, and cysteine labeling studies 10,25,26,34. Despite a lack of steric interference from DA, Phe 319, which is equivalent to Phe 253 in LeuT— in which it occludes solvent access to the LeuT binding pocket, remains splayed away from DA, in an orientation seen in the nortriptyline-bound structure9,11.

The location and interactions of DA with dDAT recall predictions made through homology models of hDAT although discrepancies with the cocrystal structure are also evident. Site-directed mutagenesis and molecular dynamics simulations pointed to the crucial role of Asp 46 (Asp 79 in hDAT) in the recognition of DA10,25,34,35, a residue conserved amongst biogenic amine neurotransmitters. GAT (γ-amino butyric acid transporter), GlyT (glycine transporter), and LeuT contain glycine at the equivalent position due to the presence of a compensatory carboxylate group in the substrates11. One notable difference between the dDATmfc-DA structure and previous hDAT models, however, is a rotation in the χ1 torsion angle of ~130° in the side chain of Asp 46 to maintain a 3 Å distance to the amine group of DA. This rotation severs the indirect coordination between Asp 46 and the sodium ion at site 1 as observed in the nortriptyline-dDATcryst complex9. Unlike previous simulation studies where DA binds in a dehydrated pocket34, we observed non protein electron density 3.1 Å from the amine group of DA, into which a water molecule was modeled. This water molecule forms a hydrogen bond with the water molecule that coordinates the sodium ion at site 1, resulting in a molecular network that links DA to the ion-binding sites. In the case of LeuT, substrate interaction with sodium site 1 is direct, with the carboxylate of leucine coordinating the sodium ion 11.

The catechol ring of DA interacts with TMs 3 and 8 by hydrogen bonds with the carboxylate group of Asp 121 (Fig. 1d). Modeling studies predicted that DA occupies multiple poses within the binding pocket with the meta-hydroxyl either interacting with residues in TM8 equivalent to Ser 421 or to Ser 422 (dDAT numbering)34. By contrast, in the structure of dDATmfc-DA, the para-hydroxyl group interacts with both the carbonyl oxygen of Ala 117 and the carboxylate of Asp 121 at distances of 2.8 and 3.1 Å, respectively, whereas the meta-hydroxyl group interacts with the side chain of Asp 121 at a distance of 2.7 Å and faces Ser 422 in TM8 at a distance of 3.8 Å.

The residues poised to interact with the catechol ring vary across DAT orthologs with invertebrate DAT orthologs retaining alanine and aspartate at positions equivalent to residues 117 and 121, respectively, whereas in most mammalian DATs residue Asp 121 is replaced by glycine and Ala 117 by serine9, the latter of which could act as a surrogate hydrogen bond partner for the catechol group. With hNET, the equivalent residues at 117 and 121 are Ala and Gly, raising the possibility of the catechol group of noradrenaline interacting with the hydroxyl of Ser 420 in hNET (TM8; equivalent to Ser 422 of dDAT and Ala 423 in hDAT). We propose that these compensatory variations within subsite B dictate catecholamine recognition common to both DAT and NET. To explain why NET binds noradrenaline and DA with nearly equal apparent affinity yet DAT prefers DA31, we must invoke longer range, indirect interactions, perhaps involving subsite B and the non-helical TM6a-6b ‘linker’ because the ‘Phe-box’ surrounding the β-carbon position is conserved between NET and DAT.

Recognition of D-amphetamine and methamphetamine

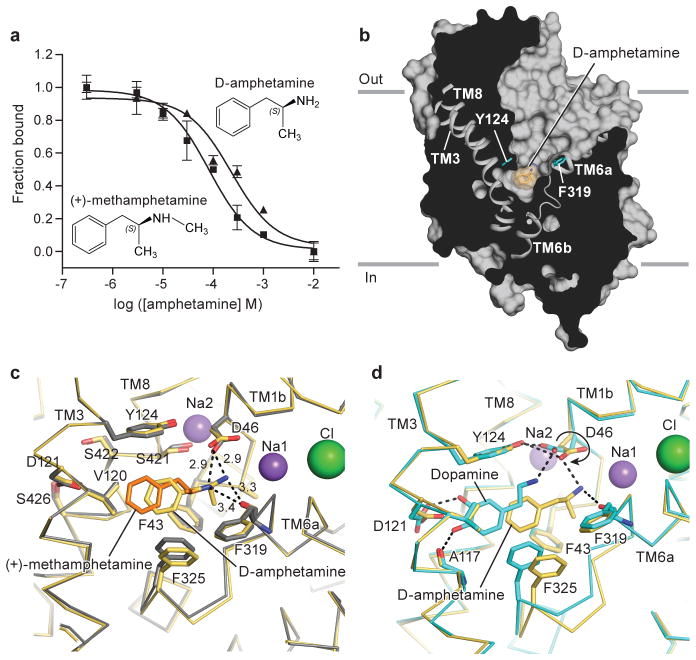

To understand how amphetamines are transported by DAT despite lacking the hydroxyl groups of the catecholamines, we characterized the interactions between amphetamines and dDAT by binding assays and crystallographic studies. (+)-Methamphetamine displaces 3H-nisoxetine binding to dDATmfc with a Ki value of 31 μM, whereas D-amphetamine, which lacks the N-methyl group present in methamphetamine, has a Ki of 86 μM (Fig. 2a). D-amphetamine is 10–100 fold weaker in its ability to inhibit DA transport in the dDAT as compared to its mammalian counterparts31. The weaker affinities of dDAT for amphetamines compared to mammalian DATs may be due in part to differences in residues of subsite B. Indeed, the presence of Asp 121 and Ser 426 in invertebrate DATs creates a polar environment that does not complement the non polar benzyl groups of amphetamines (Fig. 1d). In mammalian DATs both methamphetamine (Ki = 0.5 μM) and D-amphetamine (Ki = 0.6 μM) are nearly as effective as cocaine (0.2 μM) at inhibition of DA uptake36. Although the maximal rate of transport (Vmax) for D-amphetamine in hDAT is 5-fold lower than for DA, the KM values range from 0.8–2 μM22, consistent with the notion that mammalian subsite B is more complimentary toward the binding of amphetamines than subsite B in invertebrate DATs.

Figure 2. Amphetamines bind to central site.

a, Displacement of bound 3H-nisoxetine by methamphetamine (Ki = 31 μM) and D-amphetamine (Ki = 86 μM). Graph depicts one representative trial of two independent experiments. Error bars represent s.e.m values for individual data points measured in triplicate. b, Surface representation of D-amphetamine-dDATmfc complex viewed parallel to the membrane with ligands shown as light-orange sphere. Residues Y124 and F319 are shown as cyan sticks on the left and right sides of DA, respectively. Superposition of binding pockets of the D-amphetamine-dDATmfc structure in pale orange with binding pockets of c, methamphetamine-dDATmfc (drug in orange, backbone in gray) and d, DA-dDATmfc in teal. Hydrogen bond interactions are represented as dashed lines. Asp 46 undergoes a χ1 torsion angle shift from -168° in DA bound state to +62° in the D-amphetamine-dDATmfc.

The structures of (+)-methamphetamine-dDATmfc and D-amphetamine-dDATmfc displayed outward open conformations with electron densities for the drugs found in the central binding site (Extended Data Fig. 5; Fig. 2b). The amine groups of methamphetamine and D-amphetamine lie closer to Asp 46 at subsite A with hydrogen bonding distances of 2.9 Å, and the main chain carbonyl of Phe 319 is positioned nearby at 3.3 Å (Fig. 2c). The amine group of D-amphetamine interacts with Asp 46, which does not undergo the rotameric shift as seen in the DA-bound structure because D-amphetamine is situated in the center of the pocket and not displaced by 2.8 Å toward TMs 3 and 8 as seen with DA (Fig. 2d). By contrast with earlier findings25, we do not observe a disruption of the hydrogen bond between Asp 46 and Tyr 124 despite Asp 46 clearly forming a hydrogen bond with the primary amine of D-amphetamine. Phe 325 retains edge-to-face aromatic interactions with the phenyl group of amphetamines by way of a contraction of the TM6a-6b linker in comparison to the DA-bound state. Amphetamines adopt poses in the central binding that allow for interactions between their amino and aromatic groups and transporter subsites, thus explaining how the sterically smaller amphetamines compete with DA and act as substrates despite the absence of catechol-like hydroxyl groups.

Dopamine analog stabilizes partially occluded state

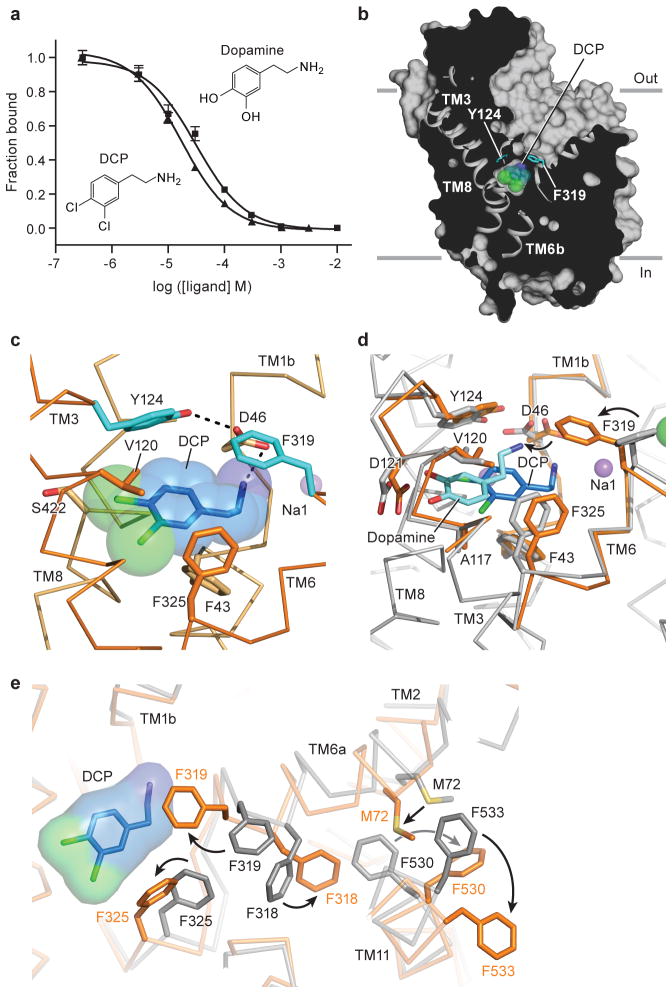

DA is prone to oxidation and thus we sought a stable analogue for crystallographic and biochemical studies. Multiple high-affinity biogenic amine transporter inhibitors harbor halogen groups on the aromatic rings predicted to occupy subsite B33,37 and thus we screened halogenated phenethylamine derivatives for binding to dDAT (Extended Data Fig. 4d). We discovered that 3,4-dichlorophenethylamine (DCP) possessed the greatest affinity and, because it is approximately isosteric to DA, was selected for further study (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. DCP induces partial occlusion of central site.

a, DCP and DA inhibit binding of 3H-nisoxetine to dDATmfc with Ki constants of 4.5 and 8.3 μM, respectively. Graph depicts one representative trial of two independent experiments, and data points indicate average values for DA and DCP in squares and triangles, respectively. Error bars represent s.d. values for individual data points measured in triplicate. b, Surface representation of the DCP-dDATmfc complex viewed parallel to the membrane with DCP shown as blue spheres and chloride in green. Residues Y124 and F319 are shown as cyan sticks on the left and right sides of DCP, respectively. c, Close-up view of DCP in the binding pocket showing the hydrogen bond between the primary amine of DCP and D46 with a distance of 3.2 Å. Sodium ions are shown as purple spheres. d, Superposition of DA- and DCP-bound dDATmfc structures reveals a 3.1 Å displacement in ligand position. The DA-dDATmfc and DCP-dDATmfc structures are colored gray and orange, respectively. e, Conformational changes of phenylalanine side chain positions in the partially occluded state of DCP-dDATmfc compared to the outward open state of nortriptyline-dDATcryst, colored orange and gray, respectively.

One DCP molecule is lodged in the central binding pocket, with the amine group forming a hydrogen bond with Asp 46, and the dichlorophenyl ring bordered by Val 120 and Phe 325 in subsites B and C, respectively (Fig. 3b to d, Extended Data Fig. 6). The position of DCP in the pocket is closer to that of D-amphetamine in dDAT and of substrate leucine in LeuT11, whereas the position of DA is shifted toward TMs 3 and 8, likely due to hydrogen bonding between the catechol hydroxyl groups and Asp 121. As a result, the position of Asp 46 in the DCP-bound structure is superimposable with the positions seen in the amphetamine-bound structures. Interestingly, the side chain of Phe 319 rotates to occlude the binding pocket, a conformational change not seen in any of the inhibitor- or DA-bound structures (Fig. 3c and d). This rotamer of Phe 319 prevents solvent access to the pocket, leaving an aperture only ~1 Å wide on the extracellular side of DCP. The equivalent residue in LeuT, Phe 253, adopts the same orientation in the occluded substrate-bound form, supporting the notion that the rearrangements seen in the DCP-dDATmfc structure are on the pathway to a LeuT-like occluded state of dDAT11. Unlike the DA-bound state, there is no evidence of a water molecule associated with DCP in the structures, suggesting that formation of an occluded state is associated with dehydration of the binding pocket (Fig. 3c and d), similar to LeuT.

The partially occluded binding pocket of the DCP-dDATmfc structure primarily results from rotations of TM1b and 6a ‘into’ the binding pocket, toward scaffold helices 3 and 8 and around axes centered near the non helical regions of TMs 1b and 6a (Extended Data Fig. 6a, c). In LeuT, studies of the transporter in solution and in the crystal show that TMs 1b and 6a, along with EL4, undergo conformational changes to close the extracellular gate11,38,39. Comparisons with the outward-open nortriptyline-bound state of dDAT9 and the occluded state of LeuT indicate that although the DCP ligand is nearly inaccessible to the extracellular solution, the inward rotations of TMs 1b (5.6°) and 6a (~7°) are less pronounced in dDAT than in LeuT11 (Extended Data Fig. 6f and g). Nevertheless, these helical rotations position the side chain of Phe 319 over the extracellular face of the binding pocket, and are associated with a series of phenylalanine sidechain reorientations (Fig. 3e). TM11 undergoes an outward movement of 6° to accommodate these side chain shifts, and an inward movement of 5° is observed in TM2 (Extended Data Fig. 6b and d). Interestingly, TMs 2, 7 and 11 at the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane form a second cholesterol binding site (site 2) where a density for cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS) was observed in all the reported structures. Indeed, CHS enhances dDAT inhibitor affinity and we speculate that in native membranes, cholesterol binds to sites 1 and 2, perhaps stabilizing DAT in an outward-open state (Extended Data Fig. 7)39–41.

The occluded state is a Michaelis-Menten-like transport intermediate for LeuT and related transporters such as BetP, Mhp1, and MhsT42–44 when bound to substrate. Disparities in conformations observed between LeuT and dDAT in the presence of substrate, however, may reflect bona fide differences that are dependent on the relative stabilities of distinct substrate-bound states. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude crystal lattice effects, Fab binding, lipid, or solutes present in the crystallization solutions that may favor the outward open conformation observed for the dDAT-substrate complexes reported here.

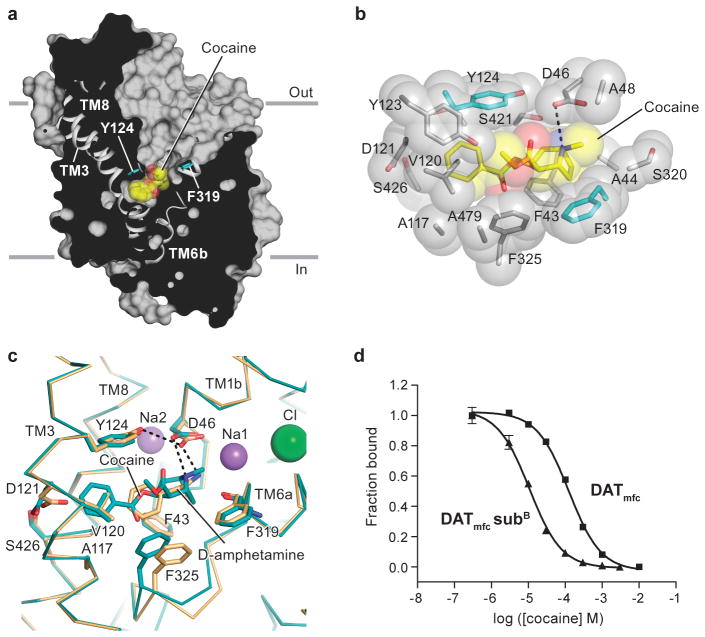

Cocaine binds in the central site

The structure of the dDATmfc - cocaine complex exhibits an outward-open conformation (Fig. 4a) with cocaine bound to the central pocket at a site overlapping the nortriptyline site45, adjacent to the Na1 and Na2 sodium ions and the chloride ion. The tertiary amino group of cocaine forms a salt bridge with Asp 46 (TM1b) (Fig. 4b). We observe that the TM6a-6b “linker” contracts, allowing Phe 325 to form edge-to-face aromatic interactions with the benzyl ring of cocaine (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4. Multivalent binding of cocaine.

a, Surface representation of the structure of cocaine-dDATmfc viewed parallel to the membrane, with cocaine displayed as yellow spheres. Residues Y124 and F319 are shown as cyan sticks on the left and right sides of cocaine, respectively. b, Close-up view of cocaine in the binding pocket with residues interfacing with cocaine shown as spheres. The tertiary amine of cocaine is 3.4 Å from the carboxylate of D46. c, Superposition of the binding pocket of the D-amphetamine-dDATmfc structure in pale orange with the binding pocket of the cocaine-dDATmfc structure in teal. d, Displacement of 3H-nisoxetine by cocaine for dDATmfc (squares) and dDATmfc subB (triangles) constructs with inhibition constant (Ki) values of 33 ± 3 μM and 3 ± 0.3 μM, respectively.

The negative electrostatic potential of subsite B in dDAT compared to mammalian DATs likely underlies the reduced affinity of dDAT for cocaine. Altering this charged pocket to mimic mammalian DATs with the mutations D121G and S426M yielded a dDAT construct with enhanced binding affinities for cocaine and β-CFT, but not for RTI-55 (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 4a and b). We speculate that the carboxylate group of Asp 121 does not form favorable interactions with the 4-fluorophenyl and 4-iodophenyl groups of β-CFT and RTI-55 respectively, perhaps accounting for some of the discrepancies in relative binding affinities between hDAT and dDAT.

Ligand docking studies using a homology model of DAT, in combination with biochemical binding assays and ligand-dependent disulfide trapping experiments, have probed the orientation of cocaine in the central binding site25,26,30. These studies predicted that the fluorophenyl moiety of β–CFT forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain equivalent to Asn 125 in dDAT. Furthermore, the methyl ester of cocaine was thought to displace the side chain of Tyr 124 to abrogate the hydrogen bond between Tyr 124 and Asp 46 as a mechanism of inhibiting transporter function. The dDATmfc-cocaine structure contradicts the finding that cocaine disrupts the Asp 46-Tyr 124 interaction and does not place the side chain of Asn 125 in a location where it could interact with the fluorophenyl group of β-CFT.

To validate the cocaine-bound structure and conclusively identify residues that interact with tropane-based ligands, structures of dDAT were solved in the presence of the cocaine analogues β-CFT and RTI-55. Anomalous scattering by the iodide of RTI-55 corroborated the location and placement of the aromatic moiety of cocaine proximal to TMs 3 and 8 (Extended Data Fig. 8a). The Fo-Fc ‘omit’ electron density maps for cocaine, β-CFT, and RTI-55 are consistent with the methyl ester group protruding into the base of the extracellular vestibule without disrupting the Asp 46-Tyr 124 interaction (Extended Data Fig. 5, Extended Data Fig. 8b). The position of β-CFT places the fluoro group 6 Å from the amide nitrogen of Asn 125, indicating that Asn 125 does not directly participate in binding of β-CFT. Superpositions of the cocaine-dDATmfc, β-CFT-dDATcryst, and RTI-55-dDATmfc structures exhibited overall mean root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) values below 0.7 Å, and residues that make close contacts with the ligands overlap nearly entirely, indicating that the halide-substituted phenyl groups of β-CFT and RTI-55 do not significantly affect the architecture of the binding pocket (Extended Data Table 1).

Residues in the binding pocket that interact with cocaine are shared by β-CFT and RTI-55, with slight deviations in subsite B due to the presence of halide substituents on these latter two inhibitors. At the distal end of the ligand, the halophenyl rings of β-CFT and RTI-55 or the benzoate of cocaine form van der Waals interactions primarily with Ala 117, Val 120, Tyr 124, Phe 325, and Ser 422, all of which were previously predicted to interact with these tropane-based inhibitors25,46,47 (Fig. 4b). A comparison with the antidepressant nortriptyline-dDATcryst structure9 reveals that the smaller benzoate group of cocaine is accommodated with a shift of the TM6a-6b “linker” and a rotation of Phe 325 into the binding pocket, which was not previously predicted. The tropane rings of cocaine, β-CFT, and RTI-55 are bordered by Phe 43, Ala 44, Asp 46, Ala 48, Phe 319, and Ser 421. The side chain of Phe 319 maintains a similar orientation as seen in the dDAT-nortriptyline structure due to the bulky tropane ring and the methyl ester group present in all three tropane inhibitors. Overall, the docking and photolabeling studies predicted the location and orientation of cocaine and its analogues to overlap with the DA-binding site of DAT25,26,30. Our structures validate these findings yet indicate distinctions that have implications for the mechanism of inhibition by tropane ligands. Taken together, structures of dDAT in complex with tropane ligands suggest that inhibition is achieved by combining a free amine with bulky tropane and aromatic moieties to limit conformational movements of the transporter.

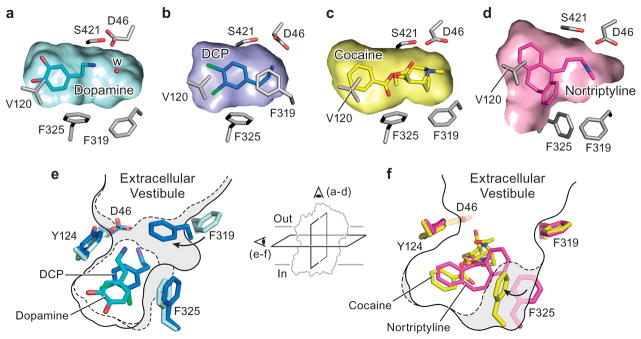

Plasticity of the substrate binding pocket

The inhibitor- and substrate-bound structures of dDAT indicate that the binding pocket of dDAT accommodates ligands of varying sizes largely by adjusting the orientation of the discontinuous region of TM 6 and the side chains of Phe 319 and Phe 325 (Fig. 5; Extended Data Table 2a). Ligand recognition by dDAT is bipartite and requires an amine group that interacts with the carbonyl oxygens of Phe 43 and Phe 319 or the carboxylate of Asp 46 in subsite A, in combination with an aromatic group that is stabilized by van der Waals interactions with residues lining a hydrophobic cleft formed by TMs 3, 6, and 8 of subsite B. The substrates DA, D-amphetamine, and methamphetamine each contain one phenyl ring linked to an ethylamine chain, requiring Phe 325 to rotate inward to contract the size of the pocket and maintain edge-to-face aromatic interactions with these ligands (Extended Data Fig. 8c, Fig. 5a, e). In the DCP-dDATmfc structure, Phe 319 also rotates inward to cover the ligand, and similar to LeuT, this reorientation of Phe 319 is required for the formation of the occluded state (Extended Data Fig. 8d, Fig. 5b, e). In order for Phe 319 to cover DCP in the pocket, rotation of Phe 319 is accompanied by the inward tilting of TM 6a to bring the hinge region of TM 6 toward the ligand (Extended Data Fig. 6). Accommodation of the single phenyl rings in tropane inhibitors requires Phe 325 to assume a position similar to that seen in the DA-bound structure to provide edge-to-face aromatic interactions (Fig. 5c, f). To enlarge the binding pocket for multiple aromatic rings, the side chains of Phe 319 and Phe 325 are splayed outward as seen in the antidepressant-bound structures (Fig. 5d, f).

Figure 5. Plasticity confers versatile recognition.

Transverse sections of the binding pocket of dDATmfc are shown as surface representations in the a, DA, b, DCP, c, cocaine and d, nortriptyline-bound structures. A water molecule (W) is observed in the vicinity of DA in a. Schematic representing plasticity within the substrate and drug binding pockets in e, occluded state of DCP-dDATmfc (broken lines) with DA-dDATmfc (solid line) and f, cocaine-dDATmfc (broken lines) with nortriptyline-dDATcryst (gray, PDB id 4M48) (solid line). Inset represents schematic to show field of view for a–d and e–f.

These structures provide a molecular explanation for the distinction between substrates and inhibitors of biogenic amine transporters. Substrates such as DA and amphetamines contain amine and aromatic functional groups at opposing ends of the molecule that interact with both the extracellular gate of TMs 1b and 6a and the scaffold TMs 3 and 8. In contrast, inhibitors exploit the flexibility of the binding pocket to bind to the outward open transporter with high affinity, acting like wedges to lock the transporter in an outward-open conformation. Tropane ligands achieve inhibition by inserting benzyl or halo-phenyl groups into the cavity of subsite B, with the tropane ring oriented to sterically hinder the movement of the extracellular gate. Antidepressants, like nortriptyline, differ from tropane inhibitors by coupling bulky aromatic moieties with an amine group to block conformational flexibility in the transporter.

Conclusions

Structures of dDAT in complex with both substrates and inhibitors emphasize the role of subsites in the pocket of dDAT in defining ligand specificity, a concept that can be expanded to understand variation in pharmacological profiles between biogenic amine transporters33. The DA-bound structure suggests that interactions between the catechol ring and subsite B, together with hydrogen bonding between the amine group of DA and Asp 46, drive closure of the extracellular gates TMs 1b and 6a to form the occluded state. D-amphetamine and methamphetamine are bound in a manner distinct from DA in the pocket, and the absence of hydroxyl groups in amphetamines indicates that hydrophobic interactions must be sufficient for amphetamines to interact with subsite B residues and bridge the scaffold TMs 3 and 8 with the extracellular gating helices. The conformations of the DA, amphetamine, and DCP-bound complexes likely represent snapshots following substrate and ion binding but prior to full closure of the extracellular gate, rather than the occluded conformation seen in LeuT bound to its substrates11,48,49. Questions extending from the substrate-bound structures involve the conformational changes required for DAT to transition to other states of the transport cycle and the roles of subsites A and B in neurotransmitter transport by mammalian DATs. Furthermore, the inhibitor-bound structures of dDAT provide a scaffold for addressing the mechanistic distinction between addictive and non-reinforcing analogs of cocaine 25,45,50.

Methods

Constructs

dDAT constructs employed in this study include:

subsite B mutations (subB)

Denotes the addition of mutations D121G (TM helix 3) and S426M (TM helix 8) in the binding pocket.

dDATwt

full-length dDAT without thermostabilizing mutations, fused to a C-terminal GFP tag.

dDATdel

Contains an N-terminal deletion from 1–20 (Δ1–20) and a deletion in extracellular loop 2 (EL2) from 164–191, with thermostabilizing mutations V74A and L415A.

ts2 dDATcryst

Contains thermostabilizing mutations (V74A, G538L), Δ1–20, a deletion in EL2 from Δ164–206, and a thrombin site replacing residues 602–607.

(Supplementary Table 1. Structure reported of this construct with subB mutations in complex with cocaine and RTI-55).

ts5 dDATcryst

Identical to ts2 dDATcryst except that it contains three additional thermostabilizing mutations (V275A, V311A, L415A). (Supplementary Table 1. Equivalent construct containing subB mutations reported for β-CFT)

dDATmfc

Contains thermostabilizing mutations (V74A, L415A), Δ1–20, a modified deletion in EL2, i.e. Δ162–202, and a thrombin site (LVPRG) replacing residues 602–607.

(Supplementary Table 1. Structures in complex with cocaine, RTI-55, D-amphetamine, (+)-methamphetamine, DA and 3,4-dichlorophenethylamine (DCP) are reported. Structure of dDATmfc containing subB mutations reported in complex with DCP)

dDATmfc 201

Identical to dDATmfc except the deletion in EL2 is from Δ162–201.

(Supplementary Table 1. Structure of dDATmfc 201 containing subB mutations reported in complex with DCP)

Expression and purification

The dDAT constructs were expressed as C-terminal GFP-His8 fusions using baculovirus-mediated transduction of mammalian HEK-293s GnTI− cells51,52. Membranes harvested from cells post-infection were homogenized with 1x TBS (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl) and solubilized with a final concentration of 20 mM n-dodecyl β-D-maltoside (DDM) and 4 mM cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS) in 1x TBS. Detergent-solubilized material was incubated with cobalt-charged metal affinity resin and eluted with 1x TBS containing 1 mM DDM and 0.2 mM CHS along with 80 mM imidazole (pH 8.0). The GFP-His8 tag was removed using thrombin digestion followed by concentrating the metal ion affinity purified protein. The thrombin-digested protein was subjected to size exclusion chromatography through a Superdex 200 10/300 column pre-equilibrated with buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 4 mM decyl β-D-maltoside, 0.2 mM CHS and 0.001% (w/v) 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE). Peak fractions greater than 0.5 mg/ml− were collected and pooled together. Ascorbic acid (25 mM) was added to the protein solution used to crystallize the DA-dDATmfc complex, to serve as antioxidant. All procedures were carried out at 4 °C.

Fab complexation and crystallization

Antibody fragment (Fab) 9D5 was used to complex with the protein at a molar ratio of 1.2 (Fab):1 (protein). The Fab-DAT complex solution was incubated with 1–2 mg solid drug for 30 minutes on ice followed by concentration in a 100 kDa cutoff concentrator to 3.5–5 mg/ml. The concentrated protein was spun down to remove excess drug and insoluble aggregates and plates were set up by hanging drop vapour diffusion. Crystals of Fab-DAT complex grew primarily in conditions containing PEG 400 or PEG 350 monomethyl ether or PEG 600 as the precipitant (Extended Data Table 2b). The pH range of crystallization was 8.0–9.0 for dDATcryst based constructs and in the range of 6.5–8.0 with dDATmfc based constructs (Extended Data Table 2b). Crystals of dDATmfc were primarily obtained by streak seeding with a cat whisker dipped in crystals formed with subB containing constructs, 2–5 days after drops were set up. All crystals were grown at 4 °C.

Data collection and structure refinement

Crystals were directly flash cooled in liquid nitrogen when the PEG 400 concentration in the mother liquor exceeded 36%. For crystals grown in wells containing less than 36% PEG 400, crystals were transferred into cryoprotection solution identical to the reservoir solution but with 40% PEG 400. In conditions with 30–34% PEG 600 as the primary precipitant, 10% of ethylene glycol was added to provide additional cryoprotection. Data were collected either at ALS (5.0.2; 8.2.1) or APS (24-IDC and IDE). Anomalous data for iodine containing RTI-55 complexed with dDAT was collected at 1.6 Å as described in the crystallographic data table. Data were processed using either HKL200052,53 or XDS54. Molecular replacement was carried out for all datasets using coordinates 4M48 with Fab 9D5 and dDATcryst used as independent search models, using PHASER in the PHENIX software suite55,56. Iterative cycles of refinement and manual model building were carried out using PHENIX and COOT57, respectively till the models converged to acceptable levels of R-factors and stereochemistry.

Radiolabel binding and uptake assays

All binding assays were carried out by scintillation proximity assay (SPA) method58. Reactions contained 5–20 nM protein, 0.5 mg/ml−1 Cu-YSi beads, SEC buffer, and [3H-nisoxetine] from 0.1–300 nM for saturation binding assays. Competition binding assays were done with 30 nM 3H-nisoxetine and increasing concentrations of unlabeled competitor. Ki values were estimated from IC50 values using the Cheng-Prusoff equation. Fits were plotted using Graphpad Prism v4.0.

For uptake assays HEK 293S cells were infected with baculovirus expressing dDATmfc or dDATwt, and sodium butyrate was added to 10 mM 8–12 hours post-infection. At 24 hours, infected cells were adhered to Cytostar-T plates for 2 hours, after which the culture media were replaced with uptake buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 10 mM D-glucose, 1 mM tropolone, 1 mM L-ascorbic acid 59,60. Uptake assays were carried out using 14C-DA over a range of 0.3–60 μM in 100 μl total volume. Samples were read every five minutes for a time course over twenty-five minutes. The linear initial rate of uptake was plotted in the presence and absence of 10 μM nortriptyline to calculate the specific uptake rate. Data were fitted to a standard Michaelis-Menten equation to obtain KM and Vmax values. The significance of specific uptake was assessed at each concentration of DA using a two-tailed Welch’s t-test with 2 degrees of freedom.

Extended Data

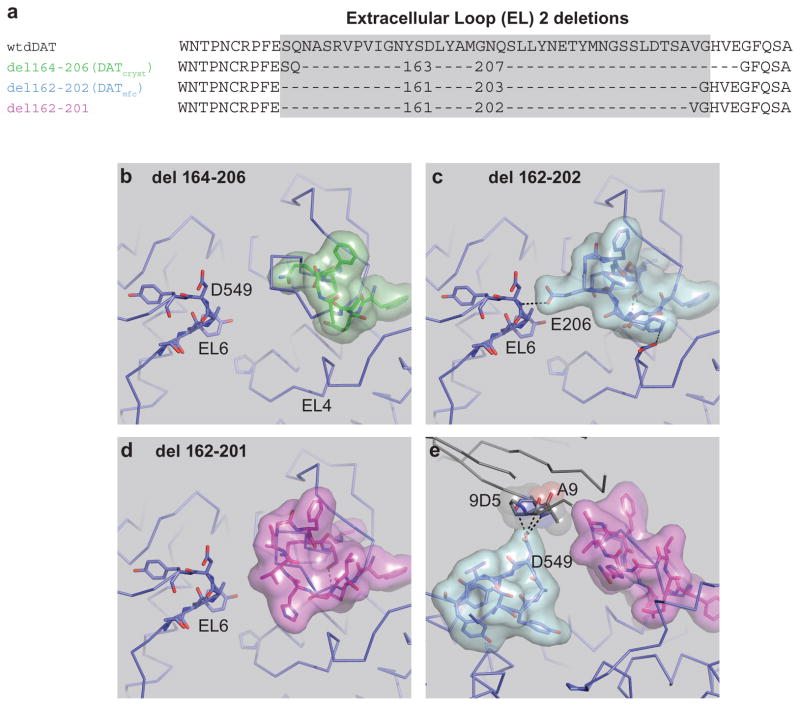

Extended Data Figure 1. Design of the minimal functional construct.

Thermostabilizing (ts) mutations V275A, V311A, G538L were removed. a, Modification of the EL2 deletion from 164–206 to 162–202, which recovered transport activity. The del 162–201 construct has robust dopamine uptake activity. b, Structural organization of EL2 regions. Organization of dDATcryst with a deletion of region 164–206 depicted as green surface. c, EL2 structure in dDATmfc with the deletion 162–202 depicted as cyan surface showing contacts between EL2 and EL6. d, EL2 organization in the construct with a deletion from 162–201 depicted as magenta surface. e, Fab 9D5 interferes with the interaction between EL2 and EL6 in the crystal lattice, with loops depicted as magenta and cyan surfaces, respectively. Fab disrupts the EL organization in all structures. The del 162–201 subB structure is shown.

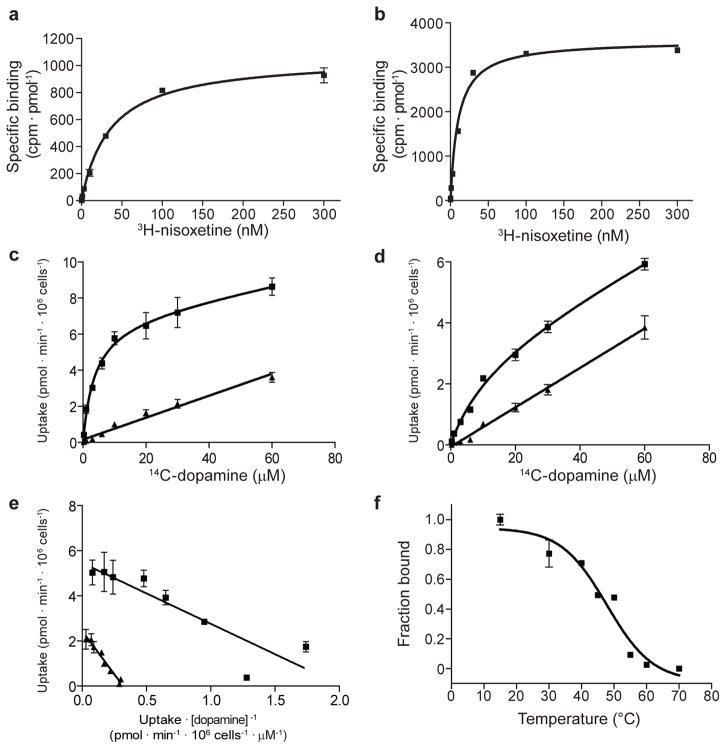

Extended Data Figure 2. Measurement of dissociation constants using purified dDATmfcp rotein, and dopamine uptake in whole cells.

a, dDATmfc binds 3H-nisoxetine with a Kd of 36 ± 3 nM (s.e.m.). b, dDATmfc with subB mutations binds 3H-nisoxetine with a Kd of 10 ± 1 nM (s.e.m.). c, d, Michaelis-Menten plots of 14C-dopamine uptake by HEK293S cells expressing dDATwt or dDATmfc, respectively, which yielded a KM of 2.1 ± 0.7 μM and Vmax of 4.5 ± 0.4 pmol/min/106 cells for dDATwt and a KM of 8.2 ± 2.3 μM and Vmax of 2.4 ± 0.2 pmol/min/106 cells for dDATmfc (s.e.m.). One representative plot of total and background counts (in the presence of 10 μM nortriptyline) is shown of two experimental trials as squares and triangles, respectively. Data points and error bars show the average and standard deviation, respectively, of technical replicates (n=3). Welch’s t-test indicates that the specific uptake signal at each concentration of dopamine is significant with a two-tailed p value < 0.02. e, Eadie-Hofstee plot of specific dopamine uptake shown in Fig. 1a and panels c and d of this figure. Data for dDATwt and dDATmfc are shown as squares and triangles, respectively, and error bars denote s.d. of technical replicates (n=3). f, The thermal melting curve of dDATmfc solubilized from HEK293S membranes in the presence of 100 nM 3H-nisoxetine exhibits a melting temperature of 48 ± 2 °C (s.e.m.). The fraction bound describes the signal remaining after incubation at the specified temperature for 10 minutes, normalized to the signal at 4°C. Data points show the mean values for one experimental trial, and error bars show the s.d. of technical replicates (n=3).

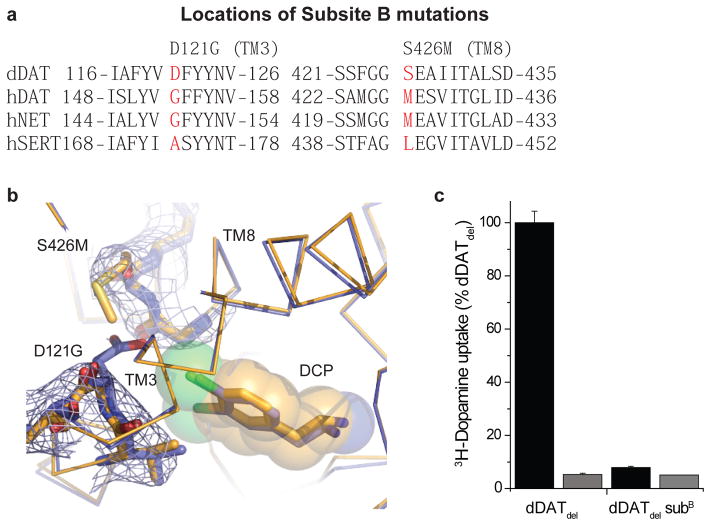

Extended Data Figure 3. Mutagenesis and effects of DAT subsite B.

a, Sequence alignment of subsite B regions for dDAT and human NSS orthologues. b, 2Fo-Fc density contoured at 0.9 σ around the vicinity of the D121G (TM3) and S426M mutations (TM8). c, Abrogation of dopamine transport activity by dDATwt bearing both subsite B mutations in infected HEK293S cells. Data show the average uptake and error bars show the data range of technical duplicates for a single trial. Reactions were performed without and with 100 μM desipramine in black and gray bars, respectively.

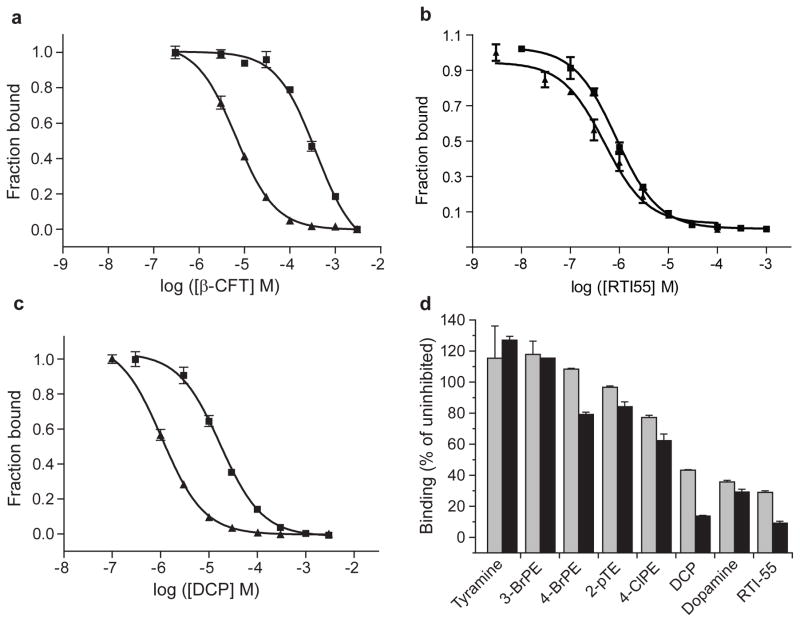

Extended Data Figure 4. Measurement of inhibition constants using purified dDAT protein.

a, b, c, Inhibition of 3H-nisoxetine binding to dDATmfc (squares) and dDATmfc subB (triangles). Ki inhibition constants for dDATmfc and dDATmfc subB are, respectively, 98 ± 4 μM, and 1.4 ± 0.1 μM, (panel a, β-CFT), 371 ± 25 nM and 271 ± 59 nM (panel b, RTI-55), and 4.5 ± 0.3 μM, and 267 ± 20 nM (panel c, DCP). All errors are s.e.m. One representative trial of two is shown for all experiments in panels a, b, c, and data points and error bars denote the average values for fraction bound and standard deviation, respectively, for technical replicates (n=3). d, Inhibition of 3H-nisoxetine (50 nM) binding to dDATdel by 1 and 10 μM unlabeled compound (gray and black bars, respectively). Error bars show the data range of technical replicates (n=2). Abbreviations: 3-BrPE, 3-bromophenethylamine; 4-BrPE, 4-bromophenethylamine; 2-pTE, 2-(p-Tolyl)ethylamine, 4-ClPE, 4-chlorophenethylamine; DCP, 3,4-dichlorophenethylamine.

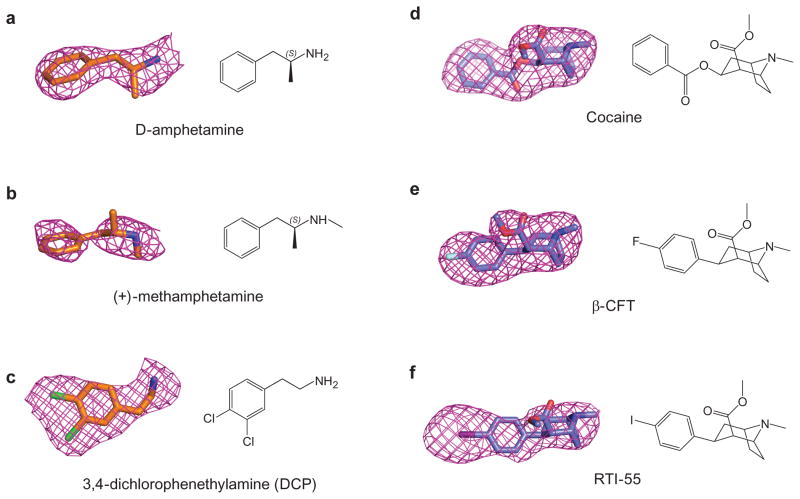

Extended Data Figure 5. Fo-Fc densities for ligands complexed with dDAT.

a, D-amphetamine (2.4 σ); b, (+)-methamphetamine (1.8 σ); c, DCP (2.2 σ); d, cocaine (2.2 σ); e, β-CFT (2.2 σ); f, RTI-55 (2.6 σ).

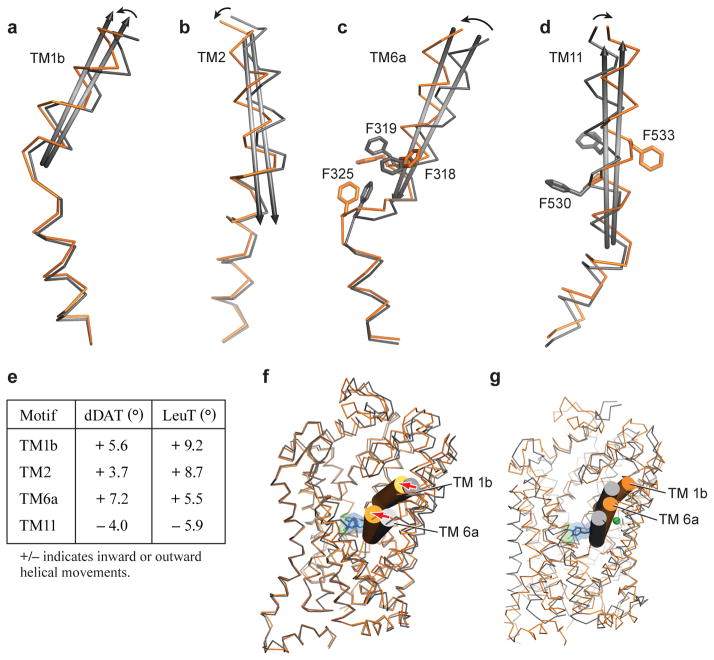

Extended Data Figure 6.

Helical movements in dDATmfc upon binding to substrate analogue DCP (orange) and inhibitor nortriptyline (grey). Helices undergoing maximal shifts are a, TM1b; b, TM2; c, TM6a; d, TM11. Arrows in black represent direction of shift. e, Table comparing angular shifts between nortriptyline-dDATcryst (PDB id 4M48) and DCP-dDATmfc structures in column one, and between the outward-open Trp-LeuT (PDB id 3F3A) and outward-occluded Leu-LeuT (PDB id 2A65) structures in column two. f, Superposition of the outward open state of nortriptyline-dDATcryst (PDB id. 4M48) and DCP-dDATmfc structures in gray and orange ribbon, respectively. Extracellular gating TMs 1b and 6a are shown as cylinders. Arrows in red indicate inward movement of TMs 1b and 6a. g, Superposition of the occluded state of LeuT (PDB id. 2A65) and DCP-dDATmfc structures in gray and orange ribbon, respectively.

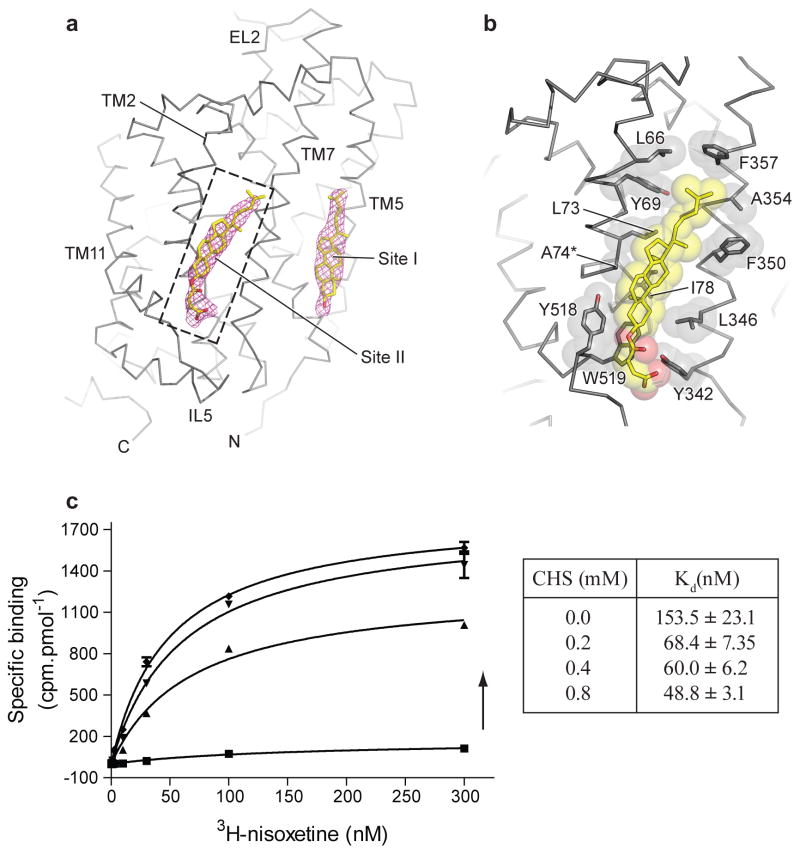

Extended Data Figure 7. Cholesterol binding sites in DAT.

a, Cholesterol binding sites seen on the dDAT surface corresponding to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, with a second novel cholesterol site into which a cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS) could be modelled. Fo-Fc densities for cholesterol contoured at 2.0 σ. b, Close-up view of cholesterol site II at the junction of TM2, TM7 and TM11 interacting with multiple hydrophobic residues. Asterisk denotes thermostabilizing mutant V74A. c, Effect of CHS concentration on 3H-nisoxetine binding to DATmfc construct. Graph depicts one representative trial of two independent experiments. Total and background counts were measured in triplicate (n=3) for each binding curve at each CHS concentration. Arrow represents increasing concentration of CHS. Error bars represent s.d.

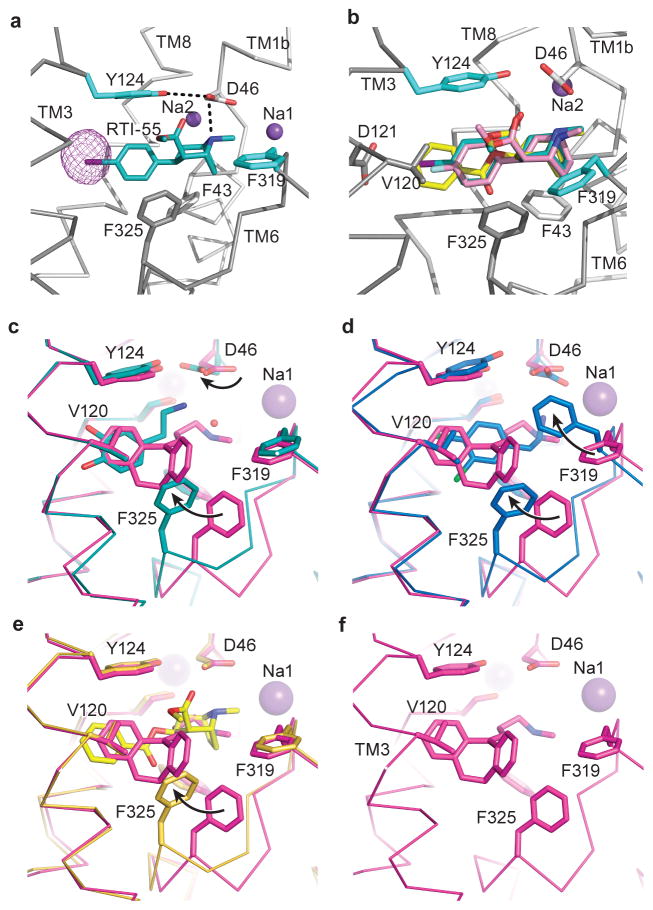

Extended Data Figure 8. Analogues of cocaine and binding site comparisons.

a, The position of RTI-55 in the binding pocket with anomalous difference density for iodide displayed as purple mesh and contoured at 4σ. b, Superposition of cocaine, β-CFT, and RTI-55 using the RTI-55-dDATmfc structure. Ligands are shown as sticks and colored yellow (cocaine), pink (β-CFT), and teal (RTI-55). Sodium ions are shown as purple spheres. (c–f), Residues that line the binding pocket are superposed between the nortriptyline-dDATcryst (magenta, PDB id 4M48) and those of c, DA-dDATmfc (cyan), d, DCP-dDATmfc (marine), e, cocaine-dDATmfc (yellow). f, Organization of S1 binding site in complex with nortriptyline (PDB id 4M48). Black arrows describe the change in rotamers and positions of D46, F319, and F325 compared to the nortriptyline-bound structure.

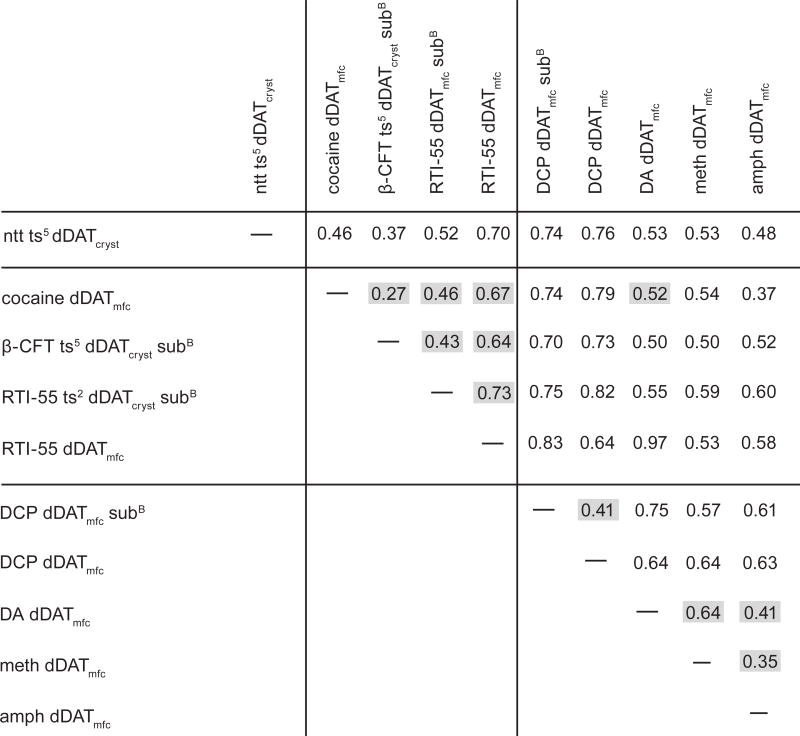

Extended Data Table 1.

Superposition statistics of dDAT structures

|

Superpositions were performed by aligning Cα atoms across all residues of dDAT

Construct abbreviations: see Materials & Methods and legend of Table 1.

Ligand abbreviations: ntt, nortriptyline; DA, dopamine; DCP, 3,4-dichlorophenethylamine; meth, (+)-methamphetamine, amph, D-amphetamine.

Values shaded in gray are referenced directly in the text.

Extended Data Table 2a.

Ligand surface and interface areas*

| Ligand | Total surface area (Å2) | Buried Surface area (Å2) | % Buried |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nortriptyline (4M48) | 475.9 | 448.4 | 94.2 |

| Cocaine | 484.7 | 447 | 92.2 |

| RTI-55 | 466.2 | 416.7 | 89.4 |

| β-CFT | 439.2 | 403.1 | 91.8 |

| dopamine | 311.9 | 279.1 | 89.5 |

| DCP | 337.3 | 321.5 | 95.3 |

| methamphetamine | 325.7 | 301 | 92.4 |

| D-amphetamine | 308.3 | 284.5 | 92.3 |

surface areas calculated by PDBePISA. (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/)

Extended Data Table 2b.

Crystallization conditions for ligand-dDAT complexes

| Ligand | Construct | Condition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cocaine | dDATmfc | PEG 400 37%, Na MES pH 6.8 (0.1M) |

| 2 | RTI-55 | dDATmfc | PEG 400 41%, Tris pH 8.0 (0.1M) |

| 3 | Methamphetamine | dDATmfc | PEG 400 38%, Tris pH 8.0 (0.1M) |

| 4 | D-amphetamine | dDATmfc | PEG 600 36%, MOPS pH 7.0 (0.1M) |

| 5 | DA (dopamine) | dDATmfc | PEG 600 31%, Tris pH 8.0 (0.1M) |

| 6 | DCP | dDATmfc | PEG 400 38%, Tris pH 8.0 (0.1M) |

| 7 | Cocaine | dDATcryst ts2 subB | PEG 400 38%, Tris-Bicine pH 8.5 (0.1M) |

| 8 | RTI-55 | dDATcryst ts2 subB | PEG 400 39%, Bicine pH 8.8 (0.1M) |

| 9 | β-CFT | dDATcryst subB | PEG 400 38%, Bicine pH 8.8 (0.1M) |

| 10 | DCP | dDATmfc subB | PEG 400 33%, Na MES pH 6.5 (0.1M) |

| 11 | DCP | dDATmfc 201 subB | PEG400 34%, Na MES pH 6.5 (0.1M) |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonathan Coleman, Chia-Hsueh Lee, Steve Mansoor, and other Gouaux lab members for helpful discussions, L. Vaskalis for assistance with figures and H. Owen for help with manuscript preparation. We acknowledge the staff of the Berkeley Center for Structural Biology at the Advanced Light Source and the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team at the Advanced Photon Source for assistance with data collection. This work was supported by an NIMH Ruth Kirschstein postdoctoral fellowship and Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Young Investigator research award (K.H.W.), a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (A.P.) and by the NIH (E.G) and the Methamphetamine Abuse Research Center of OHSU (P50DA018165 to E.G). E.G. is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Author contributions

A.P., K.H.W., and E.G. designed the project. A.P. and K.H.W. performed protein purification, crystallography, and biochemical assays. A.P., K.H.W., and E.G. wrote the manuscript.

Author information

The coordinates for the structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes 4XP1, 4XP9, 4XP6, 4XPA, 4XP4, 4XP5, 4XPB, 4XPF, 4XPG, 4XPH, 4XPT (see Supplementary Table 1 for details).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Carlsson A, Lindqvist M, Magnusson T. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylalanine and 5-hydroxytryptophan as reserpine antagonists. Nature. 1957;180:1200. doi: 10.1038/1801200a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twarog BM, Page IH. Serotonin content of some mammalian tissues and urine and a method for its determination. Am J Physiol. 1953;175:157–161. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1953.175.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Euler U. Sympathin in adrenergic nerve fibres. J Physiol. 1946;105:26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hertting G, Axelrod J. Fate of tritiated noradrenaline at the sympathetic nerve-endings. Nature. 1961;192:172–173. doi: 10.1038/192172a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iversen LL. Role of transmitter uptake mechanisms in synaptic neurotransmission. Br J Pharmacol. 1971;41:571–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1971.tb07066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iversen LL, Kravitz EA. Sodium dependence of transmitter uptake at adrenergic nerve terminals. Mol Pharmacol. 1966;2:360–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kristensen AS, et al. SLC6 neurotransmitter transporters: structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:585–640. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pramod AB, Foster J, Carvelli L, Henry LK. SLC6 transporters: structure, function, regulation, disease association and therapeutics. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:197–219. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penmatsa A, Wang KH, Gouaux E. X-ray structure of dopamine transporter elucidates antidepressant mechanism. Nature. 2013;503:85–90. doi: 10.1038/nature12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koldso H, Christiansen AB, Sinning S, Schiott B. Comparative modeling of the human monoamine transporters: similarities in substrate binding. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013;4:295–309. doi: 10.1021/cn300148r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamashita A, Singh SK, Kawate T, Jin Y, Gouaux E. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl--dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature. 2005;437:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nature03978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beuming T, Shi L, Javitch JA, Weinstein H. A comprehensive structure-based alignment of prokaryotic and eukaryotic neurotransmitter/Na+ symporters (NSS) aids in the use of the LeuT structure to probe NSS structure and function. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1630–1642. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu H, Wall SC, Rudnick G. Stable expression of biogenic amine transporters reveals differences in inhibitor sensitivity, kinetics, and ion dependence. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7124–7130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilty JE, Lorang D, Amara SG. Cloning and expression of a cocaine-sensitive rat dopamine transporter. Science. 1991;254:578–579. doi: 10.1126/science.1948035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurian MA, et al. Homozygous loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding the dopamine transporter are associated with infantile parkinsonism-dystonia. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1595–1603. doi: 10.1172/JCI39060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giros B, Jaber M, Jones SR, Wightman RM, Caron MG. Hyperlocomotion and indifference to cocaine and amphetamine in mice lacking the dopamine transporter. Nature. 1996;379:606–612. doi: 10.1038/379606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mergy MA, et al. The rare DAT coding variant Val559 perturbs DA neuron function, changes behavior, and alters in vivo responses to psychostimulants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E4779–4788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417294111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaczek R, Culp S, Goldberg H, McCann DJ, De Souza EB. Interactions of [3H]amphetamine with rat brain synaptosomes. I. Saturable sequestration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;257:820–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonisch H. The transport of (+)-amphetamine by the neuronal noradrenaline carrier. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1984;327:267–272. doi: 10.1007/BF00506235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eshleman AJ, Henningsen RA, Neve KA, Janowsky A. Release of dopamine via the human transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:312–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodwin JS, et al. Amphetamine and methamphetamine differentially affect dopamine transporters in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:2978–2989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805298200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sitte HH, et al. Carrier-mediated release, transport rates, and charge transfer induced by amphetamine, tyramine, and dopamine in mammalian cells transfected with the human dopamine transporter. J Neurochem. 1998;71:1289–1297. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71031289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonders MS, Zhu SJ, Zahniser NR, Kavanaugh MP, Amara SG. Multiple ionic conductances of the human dopamine transporter: the actions of dopamine and psychostimulants. J Neurosci. 1997;17:960–974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00960.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall SC, Gu H, Rudnick G. Biogenic amine flux mediated by cloned transporters stably expressed in cultured cell lines: amphetamine specificity for inhibition and efflux. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beuming T, et al. The binding sites for cocaine and dopamine in the dopamine transporter overlap. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:780–789. doi: 10.1038/nn.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bisgaard H, et al. The binding sites for benztropines and dopamine in the dopamine transporter overlap. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorensen G, et al. Neuropeptide Y Y5 receptor antagonism attenuates cocaine-induced effects in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;222:565–577. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2651-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richelson E, Pfenning M. Blockade by antidepressants and related compounds of biogenic amine uptake into rat brain synaptosomes: most antidepressants selectively block norepinephrine uptake. Eur J Pharmacol. 1984;104:277–286. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen L, et al. Interaction of antidepressants with the serotonin and norepinephrine transporters: mutational studies of the S1 substrate binding pocket. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:43694–43707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.342212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dahal RA, et al. Computational and Biochemical Docking of the Irreversible Cocaine Analog RTI 82 Directly Demonstrates Ligand Positioning in the Dopamine Transporter Central Substrate Binding Site. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:29712–29717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.571521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porzgen P, Park SK, Hirsh J, Sonders MS, Amara SG. The antidepressant-sensitive dopamine transporter in Drosophila melanogaster: a primordial carrier for catecholamines. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:83–95. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdul-Hussein S, Andrell J, Tate CG. Thermostabilisation of the serotonin transporter in a cocaine-bound conformation. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:2198–2207. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang H, et al. Structural basis for action by diverse antidepressants on biogenic amine transporters. Nature. 2013;503:141–145. doi: 10.1038/nature12648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang X, Zhan CG. How dopamine transporter interacts with dopamine: insights from molecular modeling and simulation. Biophys J. 2007;93:3627–3639. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitayama S, et al. Dopamine transporter site-directed mutations differentially alter substrate transport and cocaine binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7782–7785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han DD, Gu HH. Comparison of the monoamine transporters from human and mouse in their sensitivities to psychostimulant drugs. BMC Pharmacol. 2006;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman AH, Zou MF, Ferrer JV, Javitch JA. [3H]MFZ 2–12: a novel radioligand for the dopamine transporter. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:1659–1661. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kazmier K, et al. Conformational dynamics of ligand-dependent alternating access in LeuT. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:472–479. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnamurthy H, Gouaux E. X-ray structures of LeuT in substrate-free outward-open and apo inward-open states. Nature. 2012;481:469–474. doi: 10.1038/nature10737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong WC, Amara SG. Membrane cholesterol modulates the outward facing conformation of the dopamine transporter and alters cocaine binding. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32616–32626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao Y, et al. Substrate-modulated gating dynamics in a Na+-coupled neurotransmitter transporter homologue. Nature. 2011;474:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature09971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malinauskaite L, et al. A mechanism for intracellular release of Na+ by neurotransmitter/sodium symporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:1006–1012. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez C, Koshy C, Yildiz O, Ziegler C. Alternating-access mechanism in conformationally asymmetric trimers of the betaine transporter BetP. Nature. 2012;490:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature11403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weyand S, et al. Structure and molecular mechanism of a nucleobase-cation-symport-1 family transporter. Science. 2008;322:709–713. doi: 10.1126/science.1164440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loland CJ, et al. Relationship between conformational changes in the dopamine transporter and cocaine-like subjective effects of uptake inhibitors. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:813–823. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.039800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee SH, et al. Importance of valine at position 152 for the substrate transport and 2beta-carbomethoxy-3beta-(4-fluorophenyl)tropane binding of dopamine transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:883–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen JG, Sachpatzidis A, Rudnick G. The third transmembrane domain of the serotonin transporter contains residues associated with substrate and cocaine binding. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28321–28327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh SK, Piscitelli CL, Yamashita A, Gouaux E. A competitive inhibitor traps LeuT in an open-to-out conformation. Science. 2008;322:1655–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.1166777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Claxton DP, et al. Ion/substrate-dependent conformational dynamics of a bacterial homolog of neurotransmitter:sodium symporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:822–829. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmitt KC, Rothman RB, Reith ME. Nonclassical pharmacology of the dopamine transporter: atypical inhibitors, allosteric modulators, and partial substrates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346:2–10. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.191056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reeves PJ, Callewaert N, Contreras R, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: high-level expression of rhodopsin with restricted and homogeneous N-glycosylation by a tetracycline-inducible N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I-negative HEK293S stable mammalian cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goehring A, et al. Screening and large-scale expression of membrane proteins in mammalian cells for structural studies. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:2574–2585. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Afonine PV, et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quick M, Javitch JA. Monitoring the function of membrane transport proteins in detergent-solubilized form. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3603–3608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609573104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eshleman AJ, et al. Metabolism of catecholamines by catechol-O-methyltransferase in cells expressing recombinant catecholamine transporters. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1459–1466. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dehnes Y, et al. Conformational changes in dopamine transporter intracellular regions upon cocaine binding and dopamine translocation. Neurochem Int. 2014;73:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.