Abstract

Parental hostility may have widespread effects across members of the family, whereby one parent's hostility might disrupt the other parent's ability to maintain a positive relationship with his or her children. The present study prospectively examined crossover effects of parental hostility on parent-child relationship quality in a sample of 210 families. At child ages 3, 4, and 5, mothers and fathers completed questionnaires assessing feelings of hostility. In addition, mother-child and father-child dyadic relationship quality were coded at each age during naturalistic home observations. Results from structural equation analyses indicated that mother and father hostility were relatively stable over the two year period. Further, results were consistent with notions of fathering vulnerability, such that the father-child relationship might be especially susceptible to parental hostility. Possible compensatory processes, wherein mothers may compensate for father hostility, were also explored. Child and parent gender add further complexity to the results, as the father-son relationship appears most susceptible to crossover effects of parental hostility, whereas the father-daughter relationship might be somewhat protected in the early childhood period. Findings from the current investigation highlight the need for broader perspectives on family functioning, considering influences across family subsystems and the effects of both parent and child gender.

Keywords: parenting, parent-child relationships, hostility, fathering, crossover

Introduction

When parents experience and express feelings of hostility, such emotional displays may have far-reaching effects across both marital and parent-child relationships. Yet, the multiple mechanisms by which hostility influences systemic family process have not been well documented, despite their implications for well-being. Indeed, hostility, a more externalizing, outwardly-directed emotion, seems especially prone to the transmission of negativity across members of the family, such that hostility in one parent may specifically affect the quality of the relationships between the other parent and children, potentially creating a harsh, unsupportive family environment. The transmission of affect or behavior from one person to another has been described as crossover (Song, Foo, & Uy, 2008), a dynamic process that addresses one element of the complexity inherent in the family system.

Parents' internal feelings of hostility are likely to have significant consequences for interpersonal relationships within the family as a function of the outwardly-expressed behaviors that are closely linked with these hostile feelings. As opposed to feelings of depression or anxiety, hostile feelings are associated with “externalized anger,” the propensity toward expressing aggression to people or objects (Bridewell & Chang, 1997; Spielberger, 1988). Further, when feelings of hostility are stable over time, they may represent trait anger (Deffenbacher, 1992; Deffenbacher et al., 1996), a more enduring personality characteristic that is associated with more frequent and intense subjective feelings and outward expressions of anger. Those experiencing high trait anger are likely to report more outward expressions of anger as well as anger across a range of situations (Deffenbacher et al., 1996).

The externalization of angry emotion has implications for both the marital and parent-child relationship subsystems. When one member of a marital couple is high in hostility, the couple tends to exhibit more conflict during interactions, especially among couples with hostile husbands (Newton, Kiecolt-Glaser, Glaser, & Malarkey, 1995; Smith, Sanders, & Alexander, 1990). Likewise, both mothers and fathers who report symptoms of hostility are more likely to engage in harsh parenting practices with their children, possibly because a hostile personality manifests in increased aggressive behaviors towards others (Simons, Whitbeck, Conger, & Chyi-In, 1991). Hostility expressed in the parent-child relationship is associated with child behavior problems and aggression (Carrasco, Holgado, Rodríguez, & del Barrio, 2009; Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon, & Lengua, 2000). Although the particular pathways by which parental hostility influences children's externalizing behaviors remain somewhat unclear, it is possible that hostile parents have more difficulty forming secure parent-child relationships and children may develop a model for aggressive behaviors (Carrasco et al., 2009). Parental hostility may, in fact, mediate the relation between marital conflict and children's adjustment (Harold, Fincham, Osborne, & Conger, 1997; Stocker, Richmond, Low, Alexander, & Elias, 2003), thereby playing a critical role in not only the initiation of conflict but also in contributing to maladjustment across subsystems of the family.

The seemingly expansive effects of hostility demand a clearer understanding of the mechanisms by which hostility negatively influences the family environment. The set of feelings and behaviors associated with parental hostility may initiate a cascading effect across family members, such that hostility from one parent might interfere with the other's ability to form a positive, supportive relationship with his or her children. As noted above, crossover refers to a process by which affect or behavior is transferred from one person to another (Song et al., 2008). Crossover effects have been typically studied in work-family research, with mixed results regarding the effects of one partner's work pressures on the other partner's distress (Perry-Jenkins, Repetti, & Crouter, 2000). However, crossover equally well describes within-family, inter-individual processes, including the short- and possibly long-term transfer of affect and behavior from one parent to another within the family setting.

Negative mood appears more “contagious” among family members than positive mood (Larson & Almeida, 1999), possibly due to the subtle (e.g., negative facial expressions) or overt (e.g., arguing, yelling) behaviors associated with a negative mood. Parental feelings of and behaviors associated with hostility may lead to the transmission and reinforcement of aggression across family subsystems within an escalating coercive cycle of parent-child interactions (Patterson, 1982). Parental anger incites harsh, negative parent-child interactions, which, in turn, increases levels of child anger (Downey, Purdie, & Schaffer-Neitz, 1999). Moreover, families experiencing high levels of distress appear to prolong conflict and tension over time, thereby maintaining negative patterns (Margolin, Christensen, & John, 1996). It seems apparent that feelings of hostility spread among family members, making it difficult to attain and maintain a positive parent-child relationship. Nevertheless, questions remain regarding whether hostility crosses over from one parent to the other parents' relationship with the child, and just how that might occur.

A fundamental issue involves specificity in crossover relations; in this case, which family member is the sender of anger and hostility and which is the receiver. Considerable research on marital and parent-child relationships indicates that the father-child relationship is more susceptible to disturbances in the marital relationship, especially during early childhood (Belsky, Youngblade, Rovine, & Volling, 1991; Brody, Pellegrini, & Sigel, 1986; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000). Indeed, the fathering vulnerability hypothesis suggests that the father-child relationship is more at risk in the face of marital discord than the mother-child relationship (Cummings, Merrilees, & George, 2010). The discrepancy may be due to the stresses associated with fathers' roles being less clearly defined than mothers', with mothers more able to compartmentalize stress within their more scripted roles, or the tendency of fathers to be more susceptible to problems across domains (Belsky et al., 1991; Cummings et al., 2010). Although there is evidence that fathers may be more susceptible to crossover effects involving parental hostility, the mixed evidence at later points in the lifespan necessitates further exploration of parenting vulnerability hypotheses.

Although crossover has been typically treated as a micro-level process that focuses on minute-to-minute or day-to-day transactions, there is both conceptual and empirical value in likewise considering that crossover can involve longer time spans. The aggregation of minute-to-minute emotion transmission processes may set into motion a pattern of cross-parent behaviors, with significant long-term implications for parents and children, as well as their relationships. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that parental well-being crosses over to influence the other parent's experience of stress over a two year period (Gerstein, Crnic, Blacher, & Baker, 2009). Thus, interest in the possibility of more stable, long-term crossover effects requires that conceptualizations of crossover not be limited to short-term micro-processes, but extended to understand predictive crossover relations across time.

Multiple aspects of parent-child interactions are shaped by the gender of the child (e.g., Chaplin, Cole, & Zahn-Waxler, 2005; Raley & Bianchi, 2006). For example, both mothers and fathers may display more sensitivity during interactions with daughters and more hostility during interactions with sons (Lovas, 2005). Investigations of the complex interactions between parent and child gender further reveal that mothers may treat daughters and sons more consistently than do fathers (Cowen, Cowen, & Kerig, 1993), and, in turn, young daughters may respond to both parents in a more similar, coordinated manner than do sons (Power, McGrath, Hughes, & Manire, 1994). Focusing more specifically on hostility, evidence suggests that more parental hostility is displayed in same-sex versus cross-sex dyads, with father-son dyads showing the most hostility in interactions during infancy and childhood (Lovas, 2005). As patterns of parent-child interactions appear to be differentially influenced by gender over the course of development (Steinberg, 1981; Werner & Silbereisen, 2003), developmental period must also be considered to fully reveal gender differences in parent-child interactions.

Child gender may influence the extent to which mother or father hostility crosses over to affect the parent-child relationship, and understanding the ways in which the family system responds to hostility in the marital relationship provides clues to possible gendered crossover effects. For example, some research on early childhood has suggested that boys may be more susceptible to adverse effects of family discord (Davies & Lindsay, 2001; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994). Although it is possible that boys are inherently more sensitive to interparental displays of hostility, it may also be the case that boys are more frequently exposed to parental conflict and hostility (Cummings, Davies, & Simpson, 1994). In homes with greater marital discord, boys were found to experience more hostile coparenting and harsh discipline (Davies & Lindsay, 2001; McHale, 1995), and were more likely to withdraw from parent-to-child directed hostility (Gordis, Margolin, & John, 1997). In contrast to apparent male vulnerability, the parental relationship with daughters might be more affected by interparental conflict and hostility (Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000; Stroud, Wilson, Durbin, & Mendelsohn, 2011), particularly during adolescence (Werner, 2003). Still other studies report no differences between boys and girls in the extent to which interparental conflict affects the parent-child relationship (Erel & Burman, 1995). Thus, the conditions under which boys and girls might be differentially affected by crossover from parental hostility to the parent-child relationship remains somewhat unclear. The influence of child and parent gender certainly increases complexity for the study of parent-child relationships, but is necessary given the variability in research to date and the potential contribution to differences in parent-child relationships over time.

Although there is a great deal of support for the assumption that negative mood generates more negativity among other family members, the alternative possibility of compensatory processes remains feasible in the context of family relations. Compensatory processes suggest that parents may compensate for poorer relationships with their spouse by creating a stronger, more positive relationship with their child (Erel & Burman, 1995). Thus, one parent may compensate for another parent's hostility by creating a more positive, protective parent-child relationship. Mothers appear to do just that in the presence of marital problems (Belsky et al., 1999; Brody et al., 1986), suggesting the need to attend to multiple processes in understanding the interplay of family relationships in emotional contexts.

The possible cascading effects of parents' feelings of hostility on their spouses and children are not yet fully understood. The present study aims to identify the crossover effects between maternal and paternal hostility and mother- and father-child relationships across a two year period in early childhood. We examined three major aims. First, relations among maternal and paternal hostility are explored. Although we expect significant associations between parental hostility overall, given evidence of negative mood spreading across family members, it was expected that fathers would be more vulnerable to the negative effects of maternal hostility, consistent with the parenting vulnerability hypothesis. Consequently, we hypothesized that stronger relations would emerge from maternal hostility to paternal hostility than in the other direction. Second, crossover effects of parental hostility on parent-child relationships were examined for both mothers and fathers. It was hypothesized that, again, the father-child relationship would be more at risk of crossover influence from maternal hostility, but intra-individual, direct relations (i.e., from paternal hostility to the father-child relationship) were expected for both mothers and fathers. Finally, differential effects of child gender across these family processes were examined in an exploratory fashion. Although there has been speculation that boys may be more affected by family stressors than girls, particularly in response to marital conflict, research remains inconclusive (Cummings & Davies, 2002; Davies & Lindsay, 2001) and no specific hypothesized directions were determined a priori.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from a larger longitudinal investigation that prospectively explored family processes and the emergence of behavior problems in children with and without developmental delays across ages 3 to 9 years. Participants for the current study included 210 families at child ages 3, 4, and 5 for whom mother and father were present and neither caregiver changed over the two year period. With regard to the present study, 18 families were lost between 36 and 60 months, reflecting an attrition rate of 8.6% over 2 years. There were no significant differences between families who attrited and families who remained in the study.

Participants were recruited from central Pennsylvania and southern California through community agencies, including early childhood centers, family resource centers, preschools, and early intervention programs, and through flyers posted in the community. Families were excluded from the larger study if the child had severe neurological impairment, was non-ambulatory, or had a history of abuse, as assessed through parent-report or observation by study staff. Demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1, separate for child gender. Ethnicity was representative of the populations at each site; for children in the current study, 63.3% were Caucasian, 13.3% were Hispanic, 6.7% were African-American, 2.9% were Asian, and 13.8% were “other” (typically multi-racial). Ethnicity was explored as a possible covariate, but was not significantly related to any constructs of interest.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics Split by Child Gender.

| Variable | Girls (n=88) | Boys (n=122) | t score | Chi square |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child variables | ||||

|

| ||||

| Bayley scale: MDI mean scorea | Mean=91.14 SD=24.78 | Mean=82.89 SD=24.78 | 2.35 | |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 60.2% | 65.6% | 0.63 | |

| Siblings (% only children) | 21.6% | 30.3% | 2.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Parent variables | ||||

|

| ||||

| Marital status at child age 3 (% married) | 92.0% | 95.1% | .81 | |

| Mother's race (% Caucasian) | 64.8% | 68.0% | 0.25 | |

| Mother's education (% college degree) | 47.7% | 51.6% | .31 | |

| Father's race (% Caucasian) | 65.9% | 69.7% | 0.33 | |

| Father's education (% college degree) | 51.7% | 48.3% | .23 | |

| Biological father | 94.3.0% | 95.9% | .28 | |

| Median family income | $50,000-$70,000 | $50,001-70,000 | .36 | |

Note. Values in bold are significantly different between groups at p<.05.

Mental Development Index

For the larger study, children were classified as either typically developing or developmentally delayed based on scores on the Mental Developmental Index (MDI) subscale of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II (Bayley, 1993) administered at age 3; developmental delay was indicated by MDI scores below 85. For purposes of the present investigation, families were not separated on the basis of developmental status, rather MDI scores were covaried in all analyses. Although more intense relations between constructs might be anticipated for families facing risk associated with early developmental delay, we expect that family affective processes operate comparably across families that vary in developmental status, and that studying children across the broader range of developmental capabilities allows for a better understanding of the variability inherent in the processes of interest (Hoffman, Crnic, & Baker, 2006). Previous findings using the present sample (e.g., Newland & Crnic, 2011) have found comparable family processes for families of typically developing children and families of children with undifferentiated developmental delays. Regardless, tests of moderation by developmental delay status were tested in an exploratory fashion for all final models, and no evidence of moderation was found. Thus, all families were examined together for all analyses reported below.

Procedures

All procedures were completed at child ages 3, 4, and 5 years, with data collection visits conducted within two weeks of the child's birthday. Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Pennsylvania State University, University of California, Los Angeles, and University of California, Riverside.

Initial assessment

During an initial home visit at 3 years, a trained graduate student administered the Bayley Mental Scale. Basic demographic information was also collected from the families at this time.

Home observations

Home visits were conducted at child ages 3, 4, and 5, to obtain naturalistic observational data. Visits were scheduled at times when the entire family would be present. During these observations, trained graduate students collected information over 6 periods of coding at child ages 3 and 4, and 4 periods of coding at child age 5. Each period lasted 10 minutes, followed by a 5-minute period wherein coders rated the behaviors and interactions. Observers were instructed to try to be as unobtrusive as possible and to follow the child as the focal object of the observation, but likewise attend to each parent and all dyadic interactions.

Questionnaire data

Each year within two weeks of the child's birthday, mothers and fathers independently completed a series of questionnaires to assess child and family functioning, and returned them by mail.

Measures

Developmental level

Developmental level of the child was assessed using the Mental Development Index (MDI) subscale of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II (BSID-II), a well established measure of mental development in children (Bayley, 1993). A trained graduate student administered the BSID-II to all child participants at the initial home visit at 3 years. The MDI is normed, with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15.

Parental hostility

Parental hostility was assessed using the hostility subscale of the Symptom Checklist-35 (SCL-35; Derogatis, 1993), a widely used measure of perceived levels of distress. The SCL-35 is a shortened version of the SCL-90 and the Brief Symptom Inventory. The hostility subscale included 5 items, including items referring to feelings of distress about temper outbursts, feeling easily annoyed, having the urge to harm someone, and getting into arguments. This measure of hostility is proposed to capture thoughts, feelings, and actions associated with hostile behavior (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). Reliability for the measure in the present study was adequate; reliability for mothers' hostility subscale across child ages 3, 4, and 5 ranged from Cronbach's α of .73 to .80, and reliability for fathers' hostility subscale ranged from .67 to .79.

Although the hostility subscale measures perceived levels of expressed hostility, rather than actual levels of outwardly expressed hostility, the hostility scale of the SCL-90 has been found to be significantly associated with trait anger, as assessed by the Trait Anger Scale (TAS; Spielberger, 1988), and high trait anger on TAS is related to outward, uncontrolled, and negative expressions of anger (Deffenbacher et al, 1996). The SCL and BSI, including the hostility scale, have shown good construct validitiy (Derogatis & Cleary, 1977; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). Further, previous work has utilized the SCL to represent a hostile personality and hostile interpersonal style (e.g., Simons et al, 1991) and has shown relations between the hostility scale of the SCL and constructs related to expressed anger. These important associations suggest that high levels of hostile feelings assessed by the SCL-35 likely represent high levels of outwardly expressed hostility and anger.

Parent-child relationship quality

The Parent-Child Interaction Rating System (PCIRS; Belsky, Crnic, & Gable, 1995) was used during the naturalistic home observations to assess dyadic relationship quality, in addition to a number of other behaviors. The mother-child and father-child dyadic pleasure scales were each composited across the six observation periods at child ages 3 and 4 the two observation periods at age 5, providing a single score for analyses at each point. Reliability across coding periods for mother-child relationship quality ranged from Cronbach's α of .63 to .85 and reliability for father-child relationship quality ranged from .63 to .83. The dyadic pleasure scales measure the level of joyfulness, enthusiasm, and the sense that the parent and child enjoy being together. Energy level, facial expressions, tone, content on conversation, and cheerfulness were all considered when determining the score on a 1 to 5 scale. A score of 1 reflects no mutual enjoyment and/or dyadic enthusiasm, whereas a score of 5 reflects a characteristically joyful and enthusiastic interaction. Graduate student observers were trained with home-based video and in vivo contexts to reach 70% exact agreement, and greater than 95% agreement within one scale point, with a master coder. Periodic reliability checks were accomplished over time to monitor coding shift, and reliability was maintained at kappa of .6 or higher at each age period.

Data Analyses

Analyses focused on transactional relations between mother hostility, father hostility, and mother- and father-child relationship quality across a two year period. Two path analysis models were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM) in Mplus 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010), in order to jointly test the primary aims of the study. A percentile bootstrap resampling procedure was employed to adjust for non-normally distributed data and to correct for bias in the central tendency of the path estimates (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). Confidence intervals (CIs) based on 1,000 bootstrap samples were reported for all analyses, and significance of paths was determined by both p value and a confidence interval that did not include zero. The first model examined within-person and crossover effects on mother-child relationships, and the second model focused on father-child relationships. Both analyses used three-tiered autoregressive path models with cross-lagged associations among mother hostility, father hostility, and either observed mother-child relationship quality or father-child relationship quality over three time points. This analytic strategy allows for an estimation of construct stability across time, as each construct at age 5 was regressed on itself at age 4, and each construct at age 4 was regressed on itself at age 3. Moreover, cross-lagged paths were estimated between each of the constructs. This model requires that relations between constructs exist even after controlling for within-construct stability. Overall fit was tested with χ2, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and comparative fit index (CFI). To account for missing data, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used in all analyses (Enders & Bandalos, 2001).

The above sets of associations were tested using stacked models in SEM, so as to explore potential moderation in these relational processes as a function of child gender. Stacked models provide overall fit statistics with the full sample and individual parameter estimates for models with boys and their parents and for models with girls and their parents. Child MDI, in addition to maternal education, was covaried in these analyses, given the higher prevalence of developmental disabilities in boys (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). To test for differences between the boy and girl groups, each path coefficient that was significant in a single group was tested for invariance using equality constraints. Chi square difference tests then determined whether the unconstrained models fit the data significantly better than the models with constrained paths. When the unconstrained models fit the data significantly better than the constrained model, those path coefficients were considered moderated by child gender. Absent meaningful differences between the groups, models including the entire sample were maintained.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the full sample, as well as split by child gender, are presented in Table 2, and intercorrelations split by child gender, are shown in Table 3. Correlations between maternal hostility and paternal hostility, within the same time point, were generally in the small range (3 years, r = .27, p < .01; 4 years, r = .09, p = .24; 5 years, r = .15, p = .05). Mothers reported significantly higher levels of hostility than fathers at child ages 4 (t (179) = 3.16, p < .01) and 5 (t (175) = 2.56, p < .05) months, but not at child age 3 (t (200) = 1.45, p = .15).Levels of parental hostility were generally equivalent for parents of boys and parents of girls, except at age 4, wherein mothers of boys reported experiencing greater hostility than mothers girls.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables.

| Variable | Overall | Girls | Boys | t scorea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother hostility, age 3 | -1.56 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.05 (2.81) | 2.80 (2.85) | 3.22 (2.78) | |

| N | 209 | 87 | 122 | |

| Mother hostility, age 4 | -1.96 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.35 (3.21) | 2.81 (3.06) | 3.73 (3.27) | |

| N | 190 | 79 | 111 | |

| Mother hostility, age 5 | -.63 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.20 (2.91) | 3.04 (2.75) | 3.31 (3.03) | |

| N | 189 | 79 | 110 | |

| Father hostility, age 3 | .42 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.70 (2.91) | 2.80 (3.22) | 2.62 (2.67) | |

| N | 201 | 84 | 117 | |

| Father hostility, age 4 | .67 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.37 (2.32) | 2.51 (2.47) | 2.28 (2.22) | |

| N | 182 | 74 | 108 | |

| Father hostility, age 5 | .41 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.48 (2.79) | 2.59 (2.89) | 2.41 (2.74) | |

| N | 177 | 70 | 107 | |

| Mother-child relationship, age 3 | .01 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.76 (.76) | 1.76 (.73) | 1.76 (.78) | |

| N | 205 | 87 | 118 | |

| Mother-child relationship, age 4 | .79 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.56 (.55) | 1.60 (.57) | 1.53 (.54) | |

| N | 194 | 80 | 114 | |

| Mother-child relationship, age 5 | -.03 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.56 (.53) | 1.56 (.50) | 1.56 (.56) | |

| N | 190 | 80 | 110 | |

| Father-child relationship, age 3 | .85 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.80 (.81) | 1.86 (.81) | 1.76 (.81) | |

| N | 202 | 87 | 115 | |

| Father-child relationship, age 4 | -.45 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.55 (.57) | 1.53 (.57) | 1.57 (.57) | |

| N | 185 | 77 | 108 | |

| Father-child relationship, age 5 | -1.12 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.58 (.64) | 1.51 (.59) | 1.62 (.68) | |

| N | 155 | 72 | 104 |

Note. Values in bold are significantly different between groups at p<.05.

t score refers to comparison between girls and boys.

Table 3. Correlation Table Split by Child Gender.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child MDI | — | -.06 | .00 | .03 | .10 | -.06 | .02 | -.14 | -.07 | .06 | -.07 | -.20 | -.12 |

| 2. Mother hostility, 3 | -.09 | — | .71 | .30 | .18 | .19 | .09 | -.03 | -.15 | -.16 | .02 | -.04 | .17 |

| 3. Mother hostility, 4 | .00 | .73 | — | .40 | -.12 | -.01 | -.05 | -.05 | -.13 | -.03 | -.02 | -.16 | .34 |

| 4. Mother hostility, 5 | -.03 | .54 | .75 | — | -.06 | .00 | -.01 | -.06 | -.14 | -.07 | .05 | -.18 | .18 |

| 5. Father hostility, 3 | -.13 | .32 | .14 | .07 | — | .75 | .40 | -.08 | -.12 | -.19 | -.17 | .02 | -.27 |

| 6. Father hostility, 4 | .11 | .21 | .13 | .04 | .39 | — | .58 | -.11 | -.01 | -.14 | -.13 | .05 | -.14 |

| 7. Father hostility, 5 | -.08 | .16 | .22 | .18 | .54 | .56 | — | -.01 | .18 | .05 | -.09 | .05 | .00 |

| 8. M-C relationship, 3 | -.03 | -.18 | .21 | -.10 | -.04 | -.18 | .04 | — | .43 | .40 | .55 | .16 | .03 |

| 9. M-C relationship, 4 | .00 | -.13 | -.20 | -.19 | -.05 | -.09 | -.02 | .54 | — | .55 | .11 | .23 | .03 |

| 10. M-C relationship, 5 | -.09 | -.08 | -.13 | -.09 | -.03 | .05 | -.03 | .47 | .35 | — | .33 | .13 | .30 |

| 11. F-C relationship, 3 | -.04 | -.11 | -.06 | .08 | -.02 | -.13 | .09 | .69 | .35 | .38 | — | .30 | .40 |

| 12. F-C relationship, 4 | -.04 | .23 | -.12 | .03 | -.20 | -.18 | -.13 | .40 | .49 | .21 | .45 | — | .14 |

| 13. F-C relationship, 5 | -.01 | -.28 | -.17 | -.04 | -.07 | .04 | .05 | .30 | .15 | .40 | .40 | .36- | — |

Note. Correlations above the diagonal represent the scores for girls, scores below the diagonal represent the scores for boys. Correlations were estimated in Mplus using FIML. n for girls was 87 and n for boys was 114. M-C = mother-child; F-C = father-child. Numbers after variable name refer to child age. Values in bold are significant at p<.05.

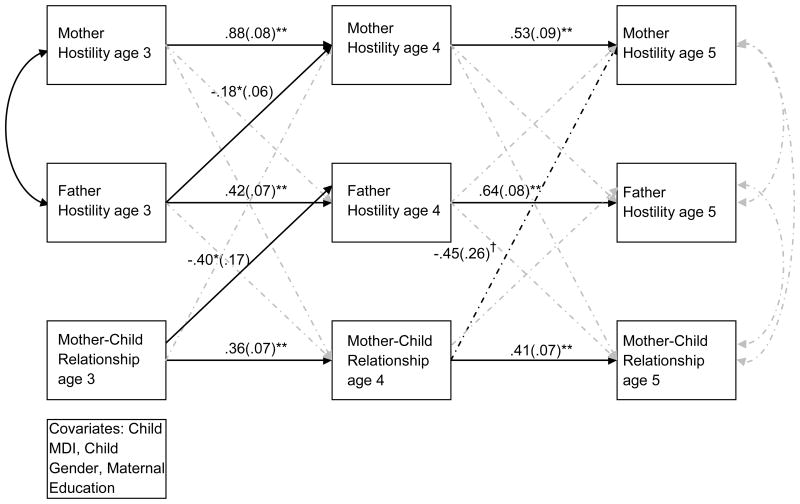

The first model, shown in Figure 1, tested the transactional relations between mother hostility, father hostility, and mother-child relationships across child ages 3, 4, and 5. The model was first tested split by child gender. However, a fully constrained model, wherein all path coefficients were equal across groups, did not show significant deterioration of fit from a fully unconstrained model, wherein all path coefficients varied across groups, Δχ2(31) = 37.34, ns. Thus, as there was no evidence of moderation by child gender, a more parsimonious model with the full sample analyzed as a single group was chosen as the final model. Given significant correlations with variables of interest, child MDI, child gender, and maternal education were included as covariates for all endogenous variables. The model had an acceptable fit to the data: χ2 (20) = 44.46, p < .01; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .04. Variance accounted for in the constructs ranged from 19% to 56%; more variance was explained in parental hostility than in mother-child relationship quality at each time point.

Figure 1.

Cross-lagged autoregressive model from child ages 3 to 5. Only significant path estimates are shown in figure for ease of readability. Numbers indicate raw path coefficients with standard errors in parenthesis. Solid lines indicate significant pathways, black dashed lines indicated marginally significant paths, and grey dashed lines indicate nonsignificant pathways. Direct paths were included from both covariates to all endogenous variables in the model, but are not shown. Model provides an adequate fit to the data: χ2 (20) = 44.46, p < .01; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .04. †p<09, *p<.05, **p<.001

Mother hostility, father hostility, and mother-child relationships showed significant stability across time but only two significant cross-lagged relations were found, and one approached significance. First, mother-child relationship quality at age 3 was negatively associated with father hostility at age 4, when controlling for previous levels of both father and mother hostility. Second, higher levels of father hostility at child age 3 were significantly related to lower levels of mother hostility at child age 4, after controlling for all age 3 constructs. The negative relation between mother-child relationship quality at age 4 and mother hostility at age 5 approached significance.

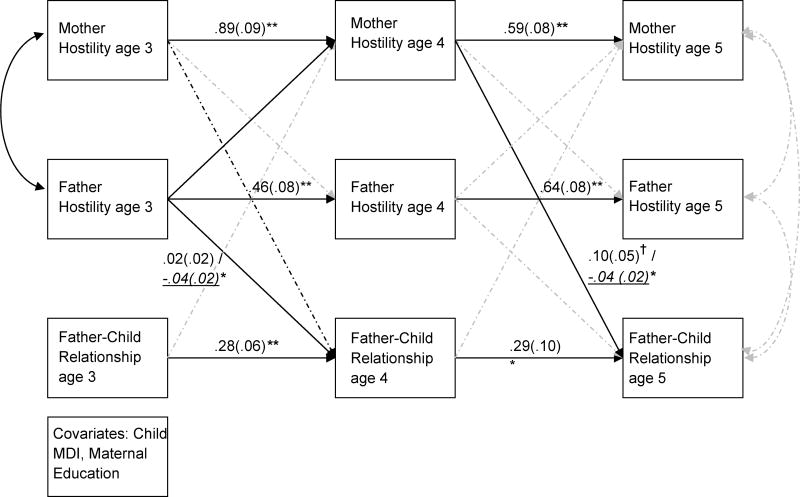

The second model, shown in Figure 2, tested the transactional relations between mother hostility, father hostility, and father-child relationships across child ages 3, 4, and 5. The path model was tested split by child gender. The fully constrained model caused a significant deterioration of fit from a fully unconstrained model, Δχ2(31) = 60.36, p < .01, suggesting that child gender moderated some of the paths in the model. Thus, each path showing potential differences in significance level between groups was tested for invariance with equality constraints. These analyses revealed that two paths were moderated by child gender, as evidenced by a significant deterioration of fit when the given path was constrained. The path from father hostility at age 3 to the father-child relationship at age 4 and the path from mother hostility at age 4 to the father-child relationship at age 5 were both moderated by child gender. A model with these two paths freely estimated and all other paths constrained across groups fit significantly better than the fully constrained model, Δχ2(2) = 21.55, p < .001, and was thus chosen as the final model. Maternal education and child MDI were included as covariates for all endogenous variables; child gender was not included as a covariate in this model, as the model was split by child gender. The model had an adequate fit to the data: χ2 (65) = 103.72, p < .01; CFI = .92; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .09. Variance accounted for ranged from 15% to 60%; again, more variance was explained in the hostility measures than in the father-child relationship variable.

Figure 2.

Cross-lagged autoregressive model from child ages 3 to 5. Paths for which two numbers are listed showed significant moderation by child gender. For these paths, numbers in standard font represent girls, numbers underlined and italicized represent boys. Only significant path estimates are shown in figure for ease of readability. Numbers indicate raw path coefficients with standard errors in parenthesis. Solid lines indicate significant pathways for at least one group, black dashed lines indicated marginally significant paths, and grey dashed lines indicate nonsignificant pathways. Direct paths were included from both covariates to all endogenous variables in the model, but are not shown. Model provides an adequate fit to the data: χ2 (65) = 103.72, p < .01; CFI = .92; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .09. †p<09, *p<.05, **p<.001

This model reveals significant stability of the father-child relationship across ages 3, 4, and 5. In addition, crossover relations from mother hostility to the father-child relationship emerged above and beyond earlier levels of the father-child relationship and father hostility, beginning somewhat weaker early but growing in strength over the preschool period. From age 3 to 4, associations from mother hostility to the father-child relationship approached significance such that higher levels of mother hostility were associated with somewhat lower levels of father-child relationship quality one year later. From age 4 to 5, the association between mother hostility and the father-child relationship quality was significant and moderated by child gender. For girls, higher levels of mother hostility trended to higher levels of father-daughter relationship quality, whereas for boys, higher levels of mother hostility were significantly related to lower levels of father-son relationship quality. The relation between father hostility at age 3 and the father-child relationship at age 4 was also moderated by child gender, wherein father hostility at age 3 was negatively associated with the father-son relationship at age 4, but no significant association was found for girls.

Given the apparent pathway from father hostility at age 3 to father-child relationship quality at age 5 via mother hostility at age 4, mediation analysis was conducted post-hoc to examine the possible role of mother hostility at a mediator between father hostility and father-child relationship. The indirect effect was tested with percentile bootstrap resampling, which produces greater accuracy in the estimation of standard errors (MacKinnon, 2008). Results revealed a conditional indirect effect, in that mother hostility did not act as a mediator for girls (B = -.02, p = .11, CI [-.04 - .001]), but there was a mediated effect for boys when using the 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals (B = .01, p = .08; CI [.001 - .018]). Thus, mother hostility mediated the relation between father hostility and the father-son relationship.

For purposes of model comparison, the mother-child relationship and father-child relationship variables were included in the same model. Paths of interest were tested for invariance using equality constraints, to determine whether apparent differences between mothers and fathers when analyzed separately were truly moderated by parent gender. Comparisons revealed a significant deterioration of fit in the model when the paths from mother hostility at 48 months to father-child relationship quality at 60 months and from father hostility at 48 months to mother-child relationship quality at 60 months were constrained to be equal, Δχ2(3) = 13.74, p < .01, suggesting moderation of these crossover relations by parent gender. In contrast, a constraint placed on the corresponding paths from the 36 to 48 month period did not cause a significant deterioration of fit, Δχ2(3) = .92, ns. The other paths which appeared different in the two models (mother-child relationship and father-child relationship) did not reveal significant moderation by parent gender when tested for invariance.

Discussion

Family and parenting research has often focused exclusively on the parent-child dyad, typically the mother-child dyad, without attention to the greater family context. In contrast, the current study highlights crossover effects across the mother- and father-child relationships, while also drawing attention to specific pathways of influence involving parental hostility and the gendered effects of hostility on the parent-child relationship. Findings support notions of fathering vulnerability (Cummings et al., 2010), whereby the father-child relationship appears more susceptible to the influence of parental hostility than the mother-child relationship. However, specific effects of child gender suggest that the father-son relationship is most at risk to crossover influences of hostility, while the father-daughter relationship might be somewhat more protected in early childhood.

Parental hostility may disrupt dyadic relationships in the family and increase conflict within the home environment, especially over time. In the current study, both mother and father hostility, or the thoughts, feelings, and actions associated with hostile, angry, or irritable behavior, were stable over a two year period. This relative stability suggests that those reporting high hostility over a two year period may in fact be experiencing more trait-like anger (Deffenbacher et al., 1996), rather than only brief, transitory periods of hostility that would be common to micro-crossover processes. Continuity in hostile affect and behavior, whether from mothers or fathers, that crosses over to adversely influence parent-child relationships supports a conceptualization of more longstanding, cross-parent, negative patterns within the family.

Contrary to expectations, mother and father hostility were generally unrelated across the early childhood period of the present study, with one notable exception. Father hostility at child age 3 was associated with lower levels of mother hostility at child age 4, suggesting a possible compensatory process. When interacting with a highly hostile partner, mothers may attempt to compensate by reducing their own levels of hostility in interpersonal relationships. Alternatively, paternal hostility may shift affective form in the transfer to maternal experience, rather than directly transmitting hostility from father to mother. For example, mothers may be more likely to feel depressed or withdrawn in the presence of paternal hostility. This shift may simply reflect gender differences in the prevalence of depression versus hostility (Kessler, McGonagle, Swartz, Blazer, & Nelson, 1993; Nolen-Hoeksma & Rusting, 1999), and in fact, mean levels of depressive symptoms are higher for mothers than for fathers in our sample. Moreover, this may suggest a particular interactional style, wherein women react to partner hostility with more internalizing emotions (Proulx, Buehler, & Helms, 2009). However, caution in generalizing this potentially compensatory effect is warranted given that only one such compensatory process was found across all of the tested relations.

Direct and crossover relations of hostility were examined with respect to both the mother-child and the father-child relationship. In regard to the determinants of mother-child relationship quality, neither mother nor father hostility seemed connected to levels of mother-child relationship quality, suggesting that the mother-child relationship quality remains stable in the face of either mothers' own experience of hostile feelings or fathers' hostile emotions. Belsky et al. (1991) surmised that women may be more skilled at maintaining boundaries between their relationships with spouses and children, providing some explanation for how the quality of the mother-child relationship is able to withstand the effects of familial hostility. Further, this pattern held true for both mother-son and mother-daughter relationships, suggesting broad stability in the quality of the relationships mothers have with their children. This is consistent with previous work indicating mothers use similar parenting styles with sons and daughters (Cowan et al., 1993) and respond to sons and daughters similarly in both positive and negative interactions (Kerig, Cowan, & Cowan, 1993; Margolin & Patterson, 1975).

Quite different transactional processes emerged in regard to determinants of the father-child relationship. Specifically, crossover effects were more often found with the father-child relationship than the mother-child relationship. But the crossover effects suggest some complexity in the timing and nature of the connections between parental hostility and father-child relationship quality. Consistent with our hypotheses, mother hostility crosses over to predict less dyadic pleasure in the father-child relationship during the preschool period, somewhat marginally from ages 3 to 4, but more compellingly so between ages 4 and 5. This crossover association between parental hostility and parent-child relationships was significantly moderated by parent gender from ages 4 to 5, such that no association emerged between father hostility and mother-child relationships during the same time period. The specificity in crossover effects in parents corroborates notions of fathering vulnerability, in that father-child relationship may be more susceptible to disruptions than the mother-child relationship in the presence of family conflict (Cummings et al., 2010). Although the mechanisms of this vulnerability remain unclear, it may be that fathers' roles are less scripted than mothers, and fathers are less able to compartmentalize stress within particular domains (e.g., marital or work; Belsky et al., 1991; Cummings et al., 2010). Moreover, fathers might be less confident in their parenting competence than mothers and, thus, fathers' parenting may be more easily disrupted by other difficulties within the family. Crossover complexity arises in that the relation between mother hostility and dyadic father-child relationship quality from age 4 to 5 is moderated by child gender. The effects seem to reflect compensatory processes for father-daughter relations and spillover processes for father-son relations.

Discord and conflict within the family appear more detrimental to the father-child relationship than to the mother-child relationship (Lamb & Lewis, 2010), and there are suggestions that father-child relationship quality may be more contingent on the greater family context during the early childhood period (Schermerhorn, Cummings, & Davies, 2008). Our findings support that the father-child relationship, especially the quality of the father-son relationship, is more vulnerable in the presence of mother hostility. Crossover effects of mother hostility may be most damaging for sons given that higher levels of hostility are typically found in father-son interactions (Lovas, 2005). Further, fathering of boys might be especially vulnerable to family conflict (Kitzmann, 2000); boys may perceive interparental conflict as more threatening than girls, and additionally, the externalizing behavior of boys may elicit more harsh discipline and family conflict (Cummings et al., 1994). So, the lower quality father-son relationship in the face of parental hostility may reflect both crossover effects on father's mood as well as boys' sensitivity to negativity in the family environment.

In contrast to the risk for sons, fathers appear to compensate for mother hostility by creating a more positive relationship with their daughters, at least during the preschool period. The father-daughter dyad has been highlighted as a distinct subsystem within the family, wherein fathers have a unique role in their daughters' development that differs from mother-daughter or father-son relationships (Russell & Saebel, 1997). Evidence about whether fathers are more globally negative to their daughters than their sons is mixed (Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & McBridge-Chang, 2003; Kerig et al., 1993), but it is possible that the father-daughter relationships may be more positive before daughters reach adolescence (Collins & Russell, 1991). In fact, fathers may show more sensitivity with daughters during childhood (Lovas, 2005). The possible transformation in father-daughter relationship quality from childhood to adolescence implies that fathers feel a particular, protective role towards their daughters. Indeed, fathers in an unhappy marriage may create a warm, close relationship with their daughters to compensate for a more distant relationship with their wives (Jacobvitz & Bush, 1996). This distinct, protective father-daughter relationship during early childhood may serve to buffer against hostility and discord from other members of the family for girls, although more information is needed to understand this possibly unique relationship during the preschool period.

Finally, an intriguing mediational process emerged, whereby early father hostility affected later father-son relationship quality through its influence on mother hostility. The indirect path becomes even more complex when examining each component. Although mothers appear able to compensate for father hostility by decreasing their own levels of hostility, mother hostility still might have a damaging effect on the vulnerable father-son relationship. Mothers' behaviors appear multiply determined, wherein mothers must manage fathers' negative or hostile emotional expressions as well as the quality of parent-child relationships. This negotiation of multiple subsystems represents a complex dance in which mothers must engage. It is possible that mothers may be relatively capable of managing hostility within one subsystem, perhaps the marital relationship, but then face substantially greater challenge when needing to also modulate hostility in relation to their children. This additive challenge may result in the crossover effect of maternal hostility observed in this study. The intricacies of this process may represent a different level of parenting vulnerability for mothers, wherein mothers are differentially susceptible to stressors in various subsystems of the family. It might also be considered that this mediated process provides further evidence for father-son vulnerability in the face of maternal hostility. Despite mothers' attempts to compensate for father hostility by decreasing their own expressions of hostile emotions, the remaining levels of mother hostility might still be detrimental to the more susceptible father-son relationship.

Despite the multi-method and longitudinal design strengths of this study, several limitations should be noted. First, the measure of parental hostility captured current feelings of perceived distress, rather than expressed hostility in the family. Although feelings of the externalizing emotion of hostility presumably correspond to levels of expressed hostility, a self-report measure of hostility and observed hostility may show somewhat different associations to parent-child relationship quality. At the same time, it is likely that even stronger relations would have emerged if capturing observed hostility that was directed at spouses or children within the same measurement period, and thus, the findings may be a conservative estimate of the true processes within the family. Further, comparisons to other studies are somewhat limited, given the considerable variability in measures of hostility, which encompass self-report and observational measures across a number of definitions of hostility, anger, and conflict. Second, we did not examine possible mediators of the relations between parental hostility and parent-child relationships. Although not the focus of the study, it is possible that marital conflict or parenting behaviors mediated the associations between parental hostility and pleasure in the parent-child relationship. The mechanisms by which hostility directly and indirectly affect parent-child relationships deserve further exploration. Third, our sample includes children with and without developmental delays. Although we believe that this captures family processes across a broader range of developmental competencies, thereby making the results more generalizable, it is possible that somewhat different results would emerge within a purely “normative” sample.

Historically prominent within-parent, direct effect models likely wash over important crossover processes of parental distress on parent-child relationships. The longitudinal, multiple-method, multiple-subsystem design of the present study expands conceptualizations of the influence of parental hostility on the family by elucidating specific effects of hostility on mother- and father-child relationships. Clinical implications of the current findings suggest advantages of therapeutic interventions involving both parents or caregivers, as a sole focus on improving one caregiver's parenting approach or the parent-child relationship may not allow for substantial change within a context of another hostile parent. Further, an awareness of parents' mental health concerns, and hostility specifically, may be essential to creating widespread change for the child and family relationships. Greater attention to these transactional processes over earlier and later developmental periods not only sheds light on continuities or discontinuities of these associations over time, but also on more precise mechanisms by which parent and child gender influence the direct and crossover effects of parental hostility on parent-child relationship quality.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, Gable S. The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: Spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development. 1995;66:629–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Youngblade L, Rovine M, Volling B. Patterns of marital change and parent-child interaction. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;53:487–498. [Google Scholar]

- Bridewell WB, Chang EC. Distinguishing between anxiety, depression, and hostility: Relations to anger-in, anger-out, and anger control. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;22:587–590. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Pellegrini AD, Sigel IE. Marital quality and mother-child and father-child interactions with school-aged children. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco MA, Holgado FP, Rodríguez MA, del Barrio MV. Concurrent and across-time relations between mother/father hostility and children's aggression: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Violence. 2009;24:213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge KA, McBridge-Chang C. Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:598–606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C. Parental socialization of emotion expression: Gender differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion. 2005;5:80–88. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Russell G. Mother-child and father-child relationships in middle childhood and adolescence: A developmental analysis. Developmental Review. 1991;11:99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Kerig PK. Mothers, fathers, sons, and daughters: Gender differences in family formation and parenting style. In: Cowan PA, editor. Family, self, and society: Toward a new agenda for family research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1993. pp. 165–195. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B, Harter K. Interparental conflict and parent-child relationships. In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and application. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic K, Pedersen y Arbona A, Baker B, Blacher J. Mothers and fathers together: Contrasts in parenting across preschool to early school age in children with developmental delays. In: Glidden LM, Seltzer MM, editors. International review of research in mental retardation. Vol. 37. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Inc.; 2009. pp. 3–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:31–63. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Simpson KS. Marital conflict, gender, and children's appraisals and coping efficacy as mediators of child adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Merrilees CE, George MW. Fathers, marriages, and families: Revisiting and updating the framework for fathering in family context. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. 5th. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010. pp. 154–176. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Lindsay LL. Does gender moderate the effects of marital conflict on children? In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and application. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 64–97. [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher JL. Trait anger: Theory, findings, and implications. In: Speilberger CD, Butcher JN, editors. Advancess in personality assessment. Vol. 9. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1992. pp. 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher JL, Oetting ER, Thwaites GA, Lynch RS, Baker DA, Stark RS, Eiswerth-Cox L. State-trait anger theory and the utility of the Trait Anger Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1996;43:131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Purdie V, Schaffer-Neitz R. Anger transmission from mother to child: A comparison of mothers in chronic pain and well mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein ED, Crnic KA, Blacher J, Baker BL. Resilience and the course of daily parenting stress in families of young children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research. 2009;53:981–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordis EB, Margolin G, John RS. Marital aggression, observed parental hostility, and child behavior during triadic family interaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick MJ, Nelson B, Hammon MA, Connor RT. Linkages between delayed children's social interactions with mothers and peers. Child Development. 2007;78:459–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Fincham FD, Osborne LN, Conger RD. Mom and dad are at it again: Adolescent perceptions of marital conflict and adolescent psychological distress. Developmental Pscyhology. 1997;33:333–350. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman C, Crnic KA, Baker JK. Maternal depression and parenting: Implications for children's emergent emotion regulation and behavioral functioning. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2006;6:271–295. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobvitz DB, Bush NF. Reconstructions of family relationships: Parent-child alliances, personal distress, and self-esteem. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:732–743. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK, Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Marital quality and gender differences in parent-child interaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:931–939. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1993;29:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM. Effects of marital conflict on subsequent triadic family interactions and parenting. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:3–13. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar A, Buehler C. Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Family Relations. 2000;49:25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME. How do fathers influence children's development? Let me count the way. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. 5th. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Lewis C. The development and significance of father-child relationships in two-parent families. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. 5th. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010. pp. 94–153. [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Almeida DM. Emotional transmission in the daily lives of families: A new paradigm for studying family process. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lovas GS. Gender and patterns of emotional availability in mother-toddler and father-toddler dyads. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2005;26:327–353. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams JM. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Patterson GR. Differential consequences provided by mothers and fathers for their sons and daughters. Developmental Psychology. 1975;11:537–538. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Christensen A, John RS. The continuance and spillover of everyday tensions in distressed and nondistressed families. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:304–321. [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP. Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:958–996. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 6th. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Newland RP, Crnic KA. Mother-child affect and emotion socialization processes across the late preschool period: Predictions of emerging behaviour problems. Infant and Child Development. 2011;20:371–388. doi: 10.1002/icd.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton TL, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Malarkey WB. Conflict and withdrawal during marital interaction: The roles of hostility and defensiveness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:512–524. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksma S, Rusting CL. Gender differences in well-being. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 330–350. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castilia Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins M, Repetti RL, Crouter AC. Work and family in the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:981–998. [Google Scholar]

- Power TG, McGrath MP, Hughes SO, Manire SH. Compliance and self-assertion: Young children's responses to mothers versus fathers. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:980–989. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx CM, Buehler C, Helms H. Moderators of the link between marital hostility and change in spouses' depressive symptoms. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:540–550. doi: 10.1037/a0015448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raley S, Bianchi S. Sons, daughters, and family processes: Does gender of children matter? Annual Review of Sociology. 2006;32:401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, Weisz JR. Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:55–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell A, Saebel J. Mother-son, mother-daughter, father-son, and father-daughter: Are they distinct relationships? Developmental Review. 1997;17:111–147. [Google Scholar]

- Schermerhorn AC, Cummings EM, Davies PT. Children's representations of multiple family relationships: Organizational structure and development in early childhood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:89–101. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, Conger RD, Chyi-In W. Intergenerational transmission of harsh parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Sanders JD, Alexander JF. What does the Cook and Medley Hostility Scale measure? Affect, behavior, and attributions in the marital context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:699–708. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z, Foo M, Uy MA. Mood spillover and crossover among dual-earner couples: A cell phone event sampling study. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2008;93:443–452. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory. Odessa: Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg LD. Transitions in family relations at puberty. Developmental Psychology. 1981;17:833–840. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker CM, Richmond MK, Low SM, Alexander EK, Elias NM. Marital conflict and children's adjustment: Parental hostility and children's interpretations as mediators. Social Development. 2003;12:149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak E, Bierman K, McMahon R, Lengua L. Parenting practices and child disruptive behaviors problems in early elementary school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:17–29. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud CB, Durbin CE, Wilson S, Mendelsohn KA. Spillover to triadic and dyadic systems in families with young children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:919–930. doi: 10.1037/a0025443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner NE, Silbereisen RK. Family relationship quality and contact with deviant peers as predictors of adolescent problem behaviors: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2003;18:454–480. [Google Scholar]