Abstract

Context

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) intoxication produces an acute depression in cardiac contractility-induced circulatory failure, which has been shown to be one of the major contributors to the lethality of H2S intoxication or to the neurological sequelae in surviving animals. Methylene blue (MB), a phenothiazinium dye, can antagonize the effects of the inhibition of mitochondrial electron transport chain, a major effect of H2S toxicity.

Objectives

We investigated whether MB could affect the immediate outcome of H2S-induced coma in unanesthetized animals. Second, we sought to characterize the acute cardiovascular effects of MB and two of its demethylated metabolites—azure B and thionine—in anesthetized rats during lethal infusion of H2S.

Materials and methods

First, MB (4 mg/kg, intravenous [IV]) was administered in non-sedated rats during the phase of agonal breathing, following NaHS (20 mg/kg, IP)-induced coma. Second, in 4 groups of urethane-anesthetized rats, NaHS was infused at a rate lethal within 10 min (0.8 mg/min, IV). Whenever cardiac output (CO) reached 40% of its baseline volume, MB, azure B, thionine, or saline were injected, while sulfide infusion was maintained until cardiac arrest occurred.

Results

Seventy-five percent of the comatose rats that received saline (n = 8) died within 7 min, while all the 7 rats that were given MB survived (p = 0.007). In the anesthetized rats, arterial, left ventricular pressures and CO decreased during NaHS infusion, leading to a pulseless electrical activity within 530 s. MB produced a significant increase in CO and dP/dtmax for about 2 min. A similar effect was produced when MB was also injected in the pre-mortem phase of sulfide exposure, significantly increasing survival time. Azure B produced an even larger increase in blood pressure than MB, while thionine had no effect.

Conclusion

MB can counteract NaHS-induced acute cardiogenic shock; this effect is also produced by azure B, but not by thionine, suggesting that the presence of methyl groups is a prerequisite for producing this protective effect.

Keywords: Hydrogen sulfide, Pulseless electrical activity, Cardiac function, Methylene blue, Azure B

Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) intoxication provokes a rapid circulatory failure1 which either leads to a cardiac arrest2 or creates, in the surviving animals, potential severe cortical or subcortical necrosis3 through the concomitant effects of a cerebral ischemia and the toxicity on neurons of sulfide poisoning per se. We have recently found that the circulatory failure produced during sulfide poisoning is primarily related to a profound depression in cardiac function rather than a vasodilation.1,2 H2S can depress cardiac contractility through various mechanisms: 1- an inhibition of L-type calcium channels on cardiomyocytes,4,5 2- an acute reduction in the mitochondrial cytochrome C activity leading to a drop in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production,6,7 and 3- a potentiation of the depressive effect of nitric oxide (NO) on cardiac function,8,9 an interaction which has been established in various tissues.10,11

The term “Phenothiazinium chromophores” has been coined to describe a family of molecules that share a common structure with phenothiazine and which are primarily used as dyes.12 The main compounds of this family are certainly methylene blue (MB, containing four methyl groups) along with its various demethylated “variations”. The latter comprises, for instance, azure B (containing three methyl groups) one of the main metabolite of MB in the body13 or thionine, in which the 4 methyl groups of MB are replaced by amine groups. Azure B seems to be found in larger proportion than MB after systemic administration of MB and to exert similar effects, leading to the contention that MB could be the pro-drug for Azure B.14

MB can support the transfer of protons through the mitochondrial membrane against a concentration gradient, essential to the production of ATP, and can bypass the normal electron flow when mitochondrial respiration is impeded.15–17 In addition, reduced MB has been shown to increase the cytochrome C oxidase activity.18 These effects clearly antagonize the mechanism of hydrogen sulfide toxicity on mitochondrial function.6,7,19,20 In keeping with this property, MB has been shown to exert a remarkable protection against the toxic effects of sodium azide,21 which is, like H2S, a poison of the mitochondrial activity. This effect has been observed when MB was injected only once after sodium azide exposure,21 or for a few days during chronic sodium azide intoxication.22 Anecdotal reports also found a protective effect of MB during cyanide intoxication.23,24 Finally, MB has been suggested to reduce post-anoxic brain injury produced by a cardiac arrest.25–29

In addition, MB inhibits guanylyl cyclase (GC), leading to a decrease in cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP),29,30 that is, the second messenger used by NO to transduce its cellular effects.28,31,32 This anti-NO effect28 has been demonstrated in many animal models and is the basis for treating refractory shock in humans, including post-operative vasoplegia or anaphylactic shock33–40 and to a much lesser extent septic shock.41–43 As H2S toxicity can be understood in the light of the recent data demonstrating a strong positive interaction between NO and H2S,10,11,44 the possibility to reduce the depressing effect of NO effects on cardiac function using MB is an intriguing path to explore.

The aims of our study were 1- to test the effects of MB on the survival from H2S -induced coma in un-anesthetized rats, 2- to determine whether the cardiac depression produced by H2S could be antagonized by MB and could account for the change, if any, in the outcome of H2S poisoning induced coma, and 3- to characterize the effects of azure B and thionine on the acute depressive effects of H2S on cardiac contractility.

Methods

1- H2S induced coma in un-anesthetized rat

Animal preparation

Twenty male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 578 ± 141 g (Charles River) were studied in this protocol. All the experiments were approved by the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

A series of pilot experiments were performed (not reported in this study) to determine the dose and concentrations of NaHS required to produce a coma. We found that intraperitoneal (IP) administration of 20 mg/kg of NaHS (5 mg/ml) led to a rapid coma in about one-third of rats weighing 500–600 g after one injection. Interestingly, a second injection performed 10 min later produced a coma in two-thirds of the remaining rats. Administration of more than 20 mg/kg at once or at a higher concentrations produced coma leading to rapid death, while at lower doses, animals would display brief episode of somnolence only but more rarely, a coma.

Protocol and Measurements

Four hours before IP injection of NaHS, animals were sedated with isoflurane (5%, then 2%) using small mask. Body temperature was maintained around 37° C using a heating pad. A tunneled catheter (PE-50) was placed in the right jugular vein, which was accessible at the back of the neck. Catheter was filled with heparinized saline (25 units/ml in saline). This procedure lasted no more than 30 min. Every animal recovered within minutes following the cessation of isoflurane inhalation and spent the following three and half hours in their cage under heating lamps. They all displayed strictly normal behavior before starting the protocol. In keeping with our pilot data, the following protocol was chosen: A first injection of NaHS was administered IP; typically, coma occurs in less than 3 min after an injection. The animals that did not present a coma within 10 min received a 2nd IP injection.

Clinical examination was performed every minute for 10 min following NaHS administration. This examination comprised the search or determination of 1- an auditory startle in response to hand clapping as well as head shaking in response to a quick air puff, to explore medullary reflexes; 2- the flexion reflex, a spinal cord reflex, which produces a flexion of the limb in response to a pinch of the toes; 3- the righting reflex, a marker of the level of coma or sedation, typically testing the integrity of the pons and mesencephalon, determined by the presence or absence of immediate turn over when the animal was placed on its back or in lateral position; and 4- the corneal reflex, which tests the integrity of the medulla during deep form of coma.45

Breathing pattern and the presence of a cardiac pulse were monitored. Coma was defined by the disappearance of response to clapping and air puff along with a loss of the righting reflex. Animals that displayed a phase of somnolence, while all reflexes were still preserved were therefore not considered to present a coma. Corneal reflex was tested when the animal was in coma. Breathing movements were monitored to identify tachypnea (breathing frequency above 400/min), hypopnea (breathing frequency below 100), and production of abrupt and large breaths at a low frequency (gasping). As soon as the animal presented with gasping, 1 ml of saline or 4 mg/kg of MB was intravenously administered. All animals received second injection one minute later. The injection of vehicle or MB was randomized, but not blinded.

During the first 24 h following H2S intoxication, each surviving animal was watched carefully for signs of distress or discomfort including signs of prostration; inability to walk, eat, and drink; paralysis; or visual deficit. The observations for the intoxicated animals were performed every 1 h in the first 8 h after the coma, and then observed 16 and 24 h after the coma.

2- H2S poisoning in anesthetized rats, effects of antidotes versus saline

Animal preparation

A total of twenty-eight adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 525 ± 146 g were studied. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition (National Research Council (US) Institute for Laboratory Animal Research). The study was approved by the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Anesthesia was induced with inhalation of isoflurane 3.5% in O2, followed by the IP injection of urethane (1.2 g/kg). Rats were tracheostomized (14G SURFLO catheter, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) and mechanically ventilated (frequency of breathing: 80 breath/min and minute ventilation (VE): ~400 ml/min) to maintain PaO2 around 80 mmHg.

A catheter (PE-50 tubing) was inserted into the right femoral artery for continuous monitoring of systemic arterial blood pressure and arterial blood sampling. A similar catheter was inserted into left ventricle through the right carotid artery for continuous monitoring of left ventricular pressure (LVP). Additional catheters were inserted into the right femoral vein for NaHS infusion and in the right jugular vein for antidote administration.

Aortic blood flow was determined as follows: a median sternotomy and a small incision of the pericardium were performed to expose the ascending aorta. A transonic flow probe (MA2PSB) was placed around the ascending aorta just above the coronary arteries. Great care was taken to prevent compression of vessels or obstruction of circulation during the procedure.

Adequate ventilation was monitored by periodic arterial blood gas measurements using i-STAT1 blood gas analyzer (Abaxis, Union City, CA).

Measurements

The arterial catheter was connected to a pressure transducer (BD DTX Plus Transducer, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ; amplifier TA-100, CWE, Ardmore, PA) to monitor blood pressure.

Aortic blood flow was measured using MA2PSB flow probe (Transonic Systems Inc. Ithaca, NY) connected to the transit-time flowmeter (TS420, Transonic Systems Inc., Ithaca, NY).

Expiratory flow was measured using a pneumotachograph (1100 Series, Hans Rudolph, Inc. Shawnee, KS), as previously described.46 Mixed expired O2 (FchO2), CO2 (FchO2), and H2S fractions (FchH2S) were measured continuously using O2 (Oxystar-100, CWE Inc. Ardmore, PA), CO2 (model 17630, VacuMed, Ventura, CA), and H2S (Interscan RM series; range: 0–200 ppm, Interscan Corporation, Simi Valley, CA) analyzers.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded by a bioelectric amplifier (Differential AC amplifier, Model 1700, A-M Systems, Sequim, WA).

All signals were digitized at 400 Hz using an analog-to-digital data acquisition system (Power Lab 16/35, AD Instruments, Inc. Colorado Springs, CO) and were visualized online. All data were stored for further analysis by LabChart7 (AD Instruments, Inc. Colorado Springs, CO).

Data analysis

All data analyses were performed in blinded manner by one of the investigators. Aortic blood flow was determined by positive integration of the raw flow signals every 3 s and then expressed in ml/min. Aortic blood flow was considered as a surrogate for cardiac output (CO) in this study and the term “cardiac output (CO)” is used for convenience throughout the manuscript. Finally, as shown in the “Results” section, the changes in central venous pressure (CVP) were relatively small, in keeping with the magnitude of the drop in blood pressure during NaHS infusion; for simplicity, systemic vascular resistances were estimated by dividing mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) by CO (MABP/CO). This point is debated in the “Discussion” section.

Breathing frequency (f) and tidal volume (VT) were determined using peak detection and integration of the expiratory flow signal, respectively, and VE was computed as f × VT in body temperature and pressure saturated or BTPS conditions.

Oxygen uptake ( ) and mixed expired fraction of H2S (FEH S) were computed as previously described.46 The partial pressure of expired H2S (PEH2S) was then calculated as FEH2S × barometric pressure (PB, 760 mmHg). Then alveolar partial pressure of H2S (PAH2S) assimilated to the arterial partial pressure of H2S (PaH2S) was computed.46 Finally, the concentration of gaseous H2S in the blood (CgH2S) was then calculated as CgH2S = 0.00012 × PaH2S, with 0.00012 being the coefficient of solubility of H2S (0.09 mole/l/760 mmHg at 37°C in saline) (see Klingerman et al.46 for further details). Assuming that H2S is under the form of H2S gas and its sulfhydryl anion HS– at a ratio of 1/3 in the arterial blood,46,47 the concentration of dissolved H2S was estimated as three times CgH2S.

Experimental protocols: IV NaHS infusion

H2S solution was prepared using sodium hydrosulfide hydrate (NaHS, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The molecular weight of the “hydrated” form of NaHS was 74.08 g/mol as the crystals used for preparing the solution contained 75% NaHS–25% H2O. NaHS was diluted in saline at a concentration of 0.8 mg/ml (10.8 mM), and prepared immediately prior to each experiment and kept in airtight syringes. The level of exposure to H2S was determined based on the relationship we have previously established between the blood concentrations, the rate of exogenously administered H2S, and the corresponding clinical symptoms, that is, H2S-induced apnea46 and cardiac toxicity2 using continuous infusion of NaHS solution.48

The rats were divided into the following groups: 7 animals received MB (4 mg/kg in 1-ml saline, Akorn, Inc., Lake Forest, IL) during NaHS infusion, seven others received equal volume of saline, while 10 animals received azure B (4 mg/kg, Sigma, n = 5) and thionine (3.6 mg/kg, Sigma, n = 5) in keeping with the molecular weight of each agent. After 30 min of stable recording, NaHS was infused at the rate (0.8 mg/min, 1 ml/min corresponding to 10.8 micromol/min) that we previously found to decrease CO within 2–3 min and to be lethal within 10 min. If this rate did not produce hypotension or reduction in CO within 2 min, infusion rate was increased by 10% (see “Results” section). Then infusion was maintained at the same rate until death occurred. Animals received a bolus injection of 4 mg/kg of MB or saline intravenously as soon as the CO reached 40% of the baseline (see “Results” section), typically corresponding to CgH2S of about 9–10 microM. The type of injection, saline versus MB, was randomly selected. Azure B or thionine was injected following the same protocol. A second injection of MB or saline was administered in each animal when CO reached 10% of its baseline value. As H2S poisoning provoked pulseless electrical activity (PEA; lack of effective contractions, while electrical signal was still present), the time to PEA, rather than survival time, was computed from the time at which the maximum rate of NaHS infusion was initiated until left ventricular peak pressure reached a value of less than 5 mmHg for more than 10 s.

In 4 additional rats, the effect of bolus injection of MB was tested without NaHS infusion. Intravenous bolus injections of 1 mg/kg of saline and 4 mg/kg of MB were performed with a 5-min interval in a random order. The same sequences of injection (MB or saline) were repeated 30 min later.

3- In vitro experiments

The interaction between MB and H2S was determined in vitro using two different approaches: First, H2S concentration was determined after reaction with N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine (NNDP) and iron chloride (FeCl3) in acidic conditions.49–51 Briefly, the reagent comprised a 20 mM solution of NNDP sulfate (Sigma) in 7.2 N hydrochloric acid (Sigma), and 30 mM FeCl3 (Sigma) in 1.2 N hydrochloric acid. Each reagent was added to different solutions containing 1- NaHS (15 or 70 microM), 2- MB (25 or 10 microM), and 3- NaHS mixed with MB for 2 min at the same concentrations as 1- and 2-. Reagents were added in all conditions at 2 min. Absorbance of the solutions between 550 and 700 nm wavelengths was measured by spectrophotometer (DU730, Beckman Coulter). The concentration of MB monomers and dimers was determined at 665 nm and 610 nm, respectively.

The concentration of NaHS with and without adding 10 microM MB was also determined by the monobromobimane method as previously described.46,52 Samples were analyzed using a high-performance liquid chromatography or HPLC system (Shimadzu) with a Phenomenex (Torrance, CA) C-18 Bondclone (4.6 × 300 mm, 10 micron) column. Under these chromatographic conditions, sulfide–bimane eluted at 19.4 min. The levels of sulfide–bimane were determined based on standard curves constructed for these analyses.

Statistical analysis

Model of coma in unsedated animals

All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). As a general frame of reference and based on preliminary data, we found that about 3 out of 4 animals do not survive the episode of coma. We therefore estimated that a sample size of 8 per group would provide 88% power to detect a difference in the mortality proportion of 0.75 in the untreated group and 0.001 (no death) in the treated group using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test having a significance level of 0.05. As presented in the “Results” section, in order to limit the number of animals that need to be sacrificed as much as possible, this figure was adjusted in keeping with the probability to produce the outcome actually observed during our experiments (see “Results” section).

Anesthetized model

A sample size of 5 per group would provide 80% power to detect a difference in blood pressure means of 25 mmHg between the two groups, assuming an SD of blood pressure of about 15 mmHg (in keeping with preliminary data), using a two-sided test having a significance level of 0.05. A sample size of 3 per group would provide 90% power to detect a difference in blood pressure means of 60 mmHg between the two groups. The number of animals used in this part of the protocol was thus determined in keeping with the ability of an antidote to restore blood pressure during H2S-induced cardiogenic shock (see “Results” section). Besides blood pressure, secondary variables of interest were compared between the saline group and the MB group using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measurements. Post-hoc comparisons were performed using a Bonferroni correction. Also, a one-way ANOVA was used to compare the change of any parameters versus time within a group. If significant, difference between specific time points was compared using Mann–Whitney test. The same analysis was performed with azure B and thionine. Survival time was compared between the saline control group and the group receiving MB using Mann–Whitney test. Survival analysis was carried out using the Kaplan–Meier method, and comparisons between groups were made using the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

H2S induced coma in un-anesthetized rats

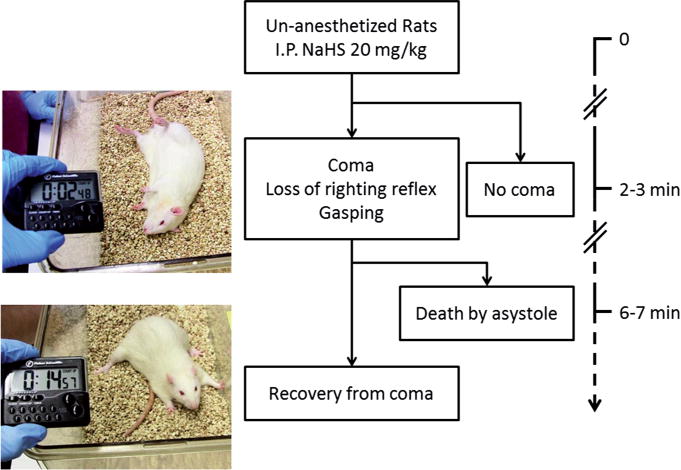

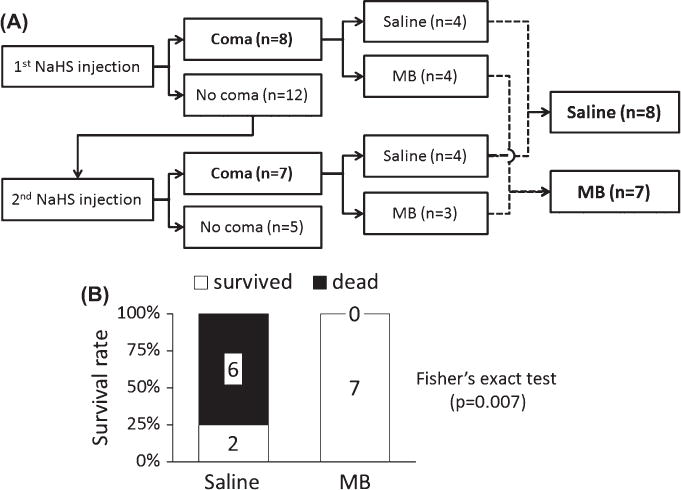

The period following NaHS administration was stereotypical in the animals presenting with a coma: during the first 70s, animals were agitated with a phase of hyperventilation, while a typical smell of rotten egg could be perceived. This phase was followed by a period of akinesia and limb paralysis leading to a coma, with a complete loss of response to clapping and the righting reflex (see Fig. 1 for more details). The phase of coma occurred with an average of 2.5 min. The animals that did not display a coma presented either short periods of somnolence but were still responsive or had no visible symptoms at all. The phase of coma rapidly led to a period of hypoventilation with slow and large breaths, clinically corresponding to gasps or agonal breathing after 3–4 min, leading either to death within 7 min or spontaneous recovery. In our present study, 20 animals were used in keeping with the algorithm shown in Fig. 2. The number of IP injections of NaHS required to produce a coma was similar in both groups (Fig. 2): 4 rats in the MB group and 4 rats in the saline group presented a coma after one injection (40%); 3 rats in the MB group and 4 in the saline group, 50% and 66%, respectively, of the remaining animals did present a coma after a second injection. The remaining animals (3 in the MB group and 2 in the saline group) did not display a coma after the second injection; therefore, they did not receive MB or saline and were excluded from the study (Fig. 2). Saline or MB were injected during the “agonal phase” when slow and deep breathing movements were observed in the comatose animals.

Fig. 1.

General outcome following IP injection of NaHS. Animals that did not present with a coma displayed either no visible change in their behavior or became drowsy for 1–2 min. Whenever a coma occurs, it took 2–3 min to develop, following a phase wherein the animals stopped their spontaneous locomotor activity. Then the rats lost their righting reflex and became irresponsive, a phase which was associated with a slow and irregular breathing pattern, leading to gasping. At this stage, rats will either spontaneously and progressively recover or will much more typically continue to gasp while heart beats will stop being perceived within 7 min.

Fig. 2.

(A) Specific outcome following IP NaHS injections (20 mg/kg, IP) in the population of 20 rats that was studied. Out of 20 rats, 15 rats fell into a deep coma following 1 or 2 injections of NaHS. The rats that presented with a coma, received either saline (n = 8) or MB (n = 7) during agonal breathing. (B) Survival rate following the treatment of coma: Six out of 8 animals died within 7 min in the saline/control group, while all 7 animals survived in the MB-treated group (significantly different from saline).

Among the 8 rats that presented with coma and were treated with saline, 6 died seven minutes after the onset of coma, and 2 recovered with no obvious abnormal behavior at least during the following 24 h—mortality was therefore 75% (Fig. 2). Asystole occurred during the phase of agonal breathing and was objectivated by a discoloration of the normal red color of retina (easily seen in albino rats), which was associated with a complete disappearance of the perception of the cardiac pulsations obtained by palpation of the thorax. Gasping continued for few minutes eventually leading to a terminal apnea. It is of note that we could determine the ECG signal in 2 rats, which continued to show a normal rhythm despite the lack of cardiac contractions. In contrast, all the 7 rats that presented with a coma and received MB, during the agonal phase, survived (Fig. 2B, p = 0.007). We decided to interrupt the study after 7 animals since the probability of observing seven animals in a row surviving after receiving MB, with a 75% mortality of sulfide-induced coma, is ∼6 × 10−5. Agonal breathing persisted for one or 2 more minutes but heart pulsations were always perceived, and the animals, which otherwise were considered as moribund by the experimenters, improved their conditions within less than 4 min.

All animals, including the ones recovering spontaneously after saline, presented a phase of akinesia recovering progressively their grasping reflex and limb motility. All the rats remained drowsy with a low reactivity to external stimuli for 20–40 min following the sulfide exposure. After 1 h, all surviving animals, but one, displayed a normal behavior with no motor deficit; these animals resumed eating and drinking within few hours after the recovery from the coma. One animal remained drowsy for 12 h. All animals were alive at 24 h, before being euthanized.

Circulatory effects of MB during lethal infusion of H2S in anesthetized rats

Effects of saline injection (control group, n = 7)

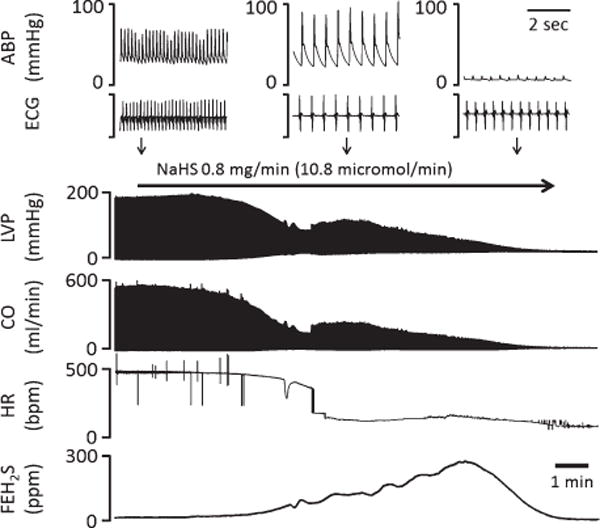

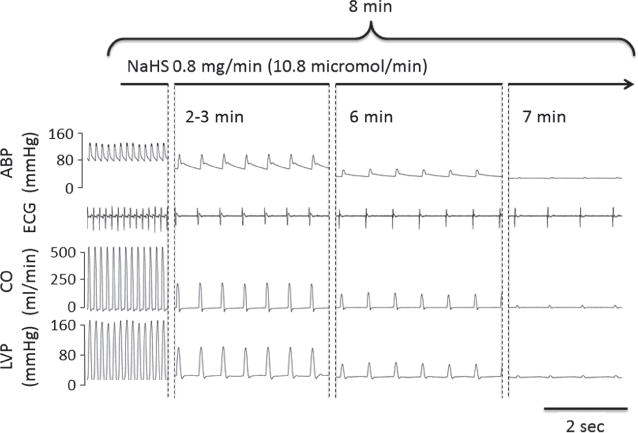

Figs. 3, 4, and 5 are examples of the circulatory effects of NaHS infusion, while averaged data are displayed in Figs. 6, 8, and 9. At the rate of NaHS infusion of 0.8 mg/min (10.8 micromol/min), MABP dropped from 82 ± 16 mmHg to 74 ± 17 mmHg as soon as CgH2S exceeded 3 microM, which occurred within 2–3 mins (average delay: 122 ± 29 sec). Then MABP continued to drop reaching 41 ± 9 mmHg (p = 0.001 vs. −60 s), when CgH2S reached 9 microM, which was the moment when the first injection of MB or the saline solution was performed. The decrease in MABP was clearly related to a decrease in cardiac function: CO and left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP) dropped from 97 ± 29 to 35 ± 15 ml/min (p < 0.001 vs. −60 s) and from 132 ±34 to 84 ±22 mmHg (p <0.001 vs. −60 s), respectively, before saline injection. Heart rate (HR) decreased from 440 ±52 beats/min to 291 ± 54 (p < 0.001 vs. −60 s). Along with the decrease in CO, VO2 dropped from 12 ± 5 ml/min to 8 ± 4 ml/min (p < 0.05) and dP/dtmax decreased from 5941 to 2699 mmHg/s. Following the bolus injection of 1-ml saline, all cardiac parameters kept decreasing, then stabilized at a lower level (MABP, 36 ± 16 mmHg; CO, 17 ± 14 ml/min; HR, 131 ± 41 beats/min; VO2, 4 ± 3 ml/min; and dP/dtmax, 2092 ± 1381 mmHg/s) 60 s later, before dropping again until terminal cardiac arrest occurred. Of note is that in all animals, the decrease in HR was very rapid and abrupt occurring about 3 min after infusion (see Figs. 3 and 4) leading to a severe bradycardia (108 ± 12 bpm), which persisted until PEA. As described in the “Methods” section, peripheral resistances were estimated using MABP/CO ratio, neglecting the change in CVP. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the increase in CVP during the period of cardiogenic shock was very modest in keeping with the change in blood pressure, likely related to the severe drop in CO. MABP/CO ratio increased throughout the period of sulfide exposure. Six out of the 7 rats died by PEA, while one rat presented with a ventricular tachycardia leading to fatal ventricular fibrillation (VF) at 180 s. In the 6 rats that presented PEA, a complete loss of pulse pressure occurred within 532 ± 52 (median: 530) s following NaHS infusion. In these 6 rats, CgH2S reached its peak level (22 ± 11 microM) about 180 s after saline injection and then mixed FEH2S started to decrease, when the level of CO dropped below 4.7 ml/min (about 20 times less than the baseline values). In all these tests, the ECG showed a sustained activity for 820 ± 46 (median: 831) s. The survival time for all the groups—including the rat that presented VF—averaged 481 ± 141 s.

Fig. 3.

Effects of continuous infusion of NaHS (0.8 mg/min, corresponding to 10.8 micromol/min) on circulation and mixed FEH2S in one rat. ABP, arterial blood pressure; ECG, electrocardiogram; LVSP, left ventricular systolic pressure; CO, cardiac output; HR, heart rate; FEH2S, expired fraction of H2S. LVP and CO decreased very rapidly according to the rise in H2S concentration. HR abruptly dropped during infusion, resulting in a transient increase in arterial pulse pressure. Note that asystole was associated with a typical PEA.

Fig. 4.

Recording in one rat showing the evolution of ABP, ECG signal, CO, and LVP at various times during H2S infusion. Note 1- the rapid decrease in CO and LVP leading to PEA, as demonstrated by the persistence of an electrical activity, and 2- the severe bradycardia which occurred very abruptly in all animals.

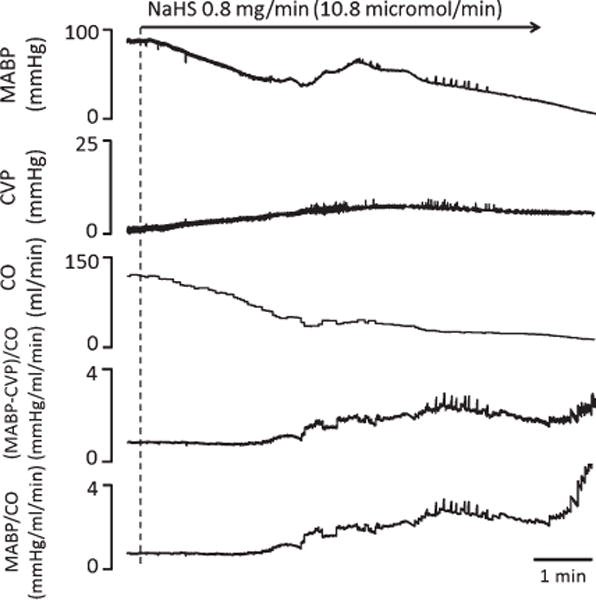

Fig. 5.

MABP, CVP, and CO were monitored in one rat during NaHS infusion, and vascular resistance was computed accordingly. MABP and CO largely dropped, while CVP rose up to 6–8 mmHg. The relatively small increase of CVP did not affect the kinetics of the changes in vascular resistance computed by the original formula (MABP-CVP)/CO or its simplified version (MABP/CO).

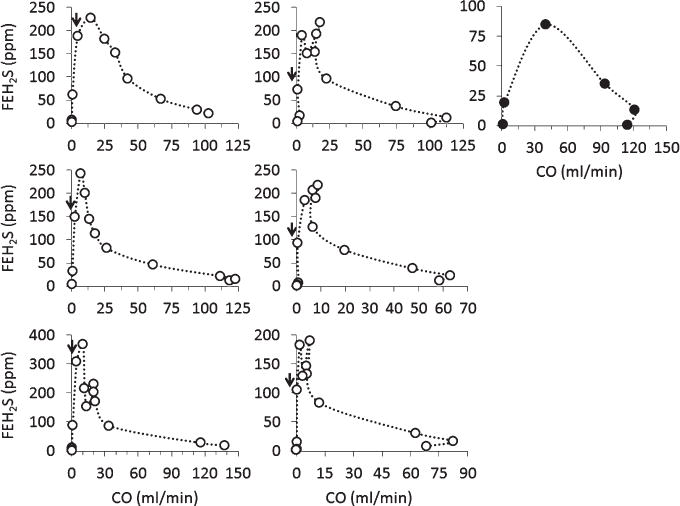

Fig. 6.

Individual plots of mixed FEH2S as a function of CO in the 7 control rats during NaHS infusion. Six rats (depicted using open-circle) presented a gradual decrease of CO until PEA was observed. The plot displaying the closed-circles was obtained from the only rat presenting a VF during NaHS infusion (see “Results” section). As this rat presented a sudden death, while its CO was still elevated, its response pattern was different from all the other rats. CO dropped in all the rats along with a rise in FEH2S, until very low levels of CO (less than 5 ml/min) were reached wherein FEH2S started to drop (arrow heads).

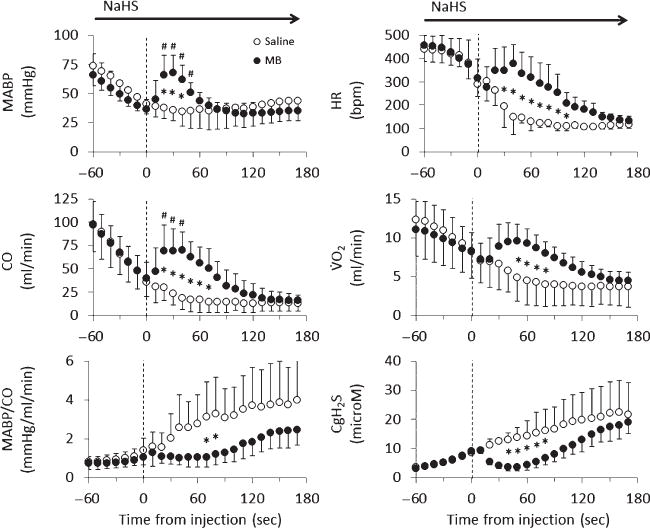

Fig. 8.

Mean ± SD values of MABP, CO, peripheral resistance (MABP/CO), HR, VO2, and CgH2S in rats receiving saline (open-circle) or 4 mg/kg MB (closed-circle) during lethal infusion of NaHS (n = 14). Saline and MB were injected at time 0 (dashed line), and data were averaged every 10 s. Continuous NaHS infusion decreased all circulatory parameters, while increasing CgH2S. Saline injection did not affect the decrease in MABP, CO, HR, and VO2. In contrast, MB had an immediate effect on circulation, significantly increasing MABP, CO, HR, and VO2 for about 2 min. *Significantly different from saline/control, p < 0.05. #Significantly different from pre-injection values, p < 0.05.

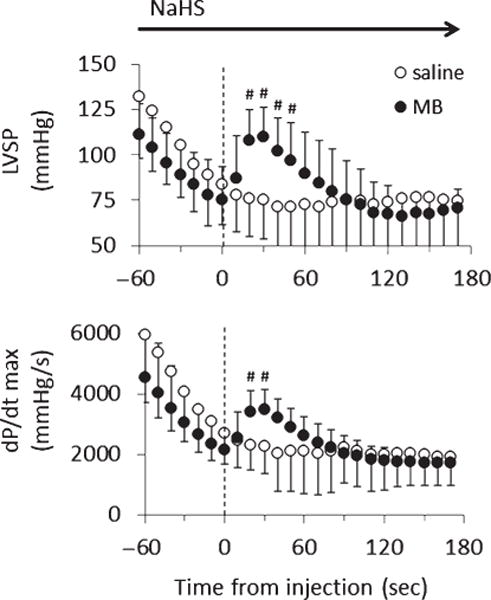

Fig. 9.

Mean ± SD values of LVSP and dP/dtmax in the rats receiving saline (open-circle) or 4 mg/kg MB (closed-circle) during lethal infusion of NaHS (n = 14). Same legends as in Fig. 8.

Effect of MB injection (n = 7)

Figure 7 displays an example of effects of MB injection while the averaged data are displayed in Figs. 8 and 9. There was no difference in the rate of NaHS infusion, the change in CO, MABP, or VO2 between the 2 groups of rats before infusion of MB versus control animals. In contrast to the saline injection, the infusion of 4 mg/kg of MB induced a rapid increase in MABP, CO, dP/dtmax, VO2, and HR. Thirty seconds after MB injection, MABP rose from 36 8 mmHg to 67 ± 13 mmHg (p < 0.001), while CO and LVSP rose from 40 ± 17 ml/min to 70 ± 20 ml/min (p < 0.05) and from 75 ± 18 mmHg to 110 ± 17 mmHg (p < 0.001), respectively (1st MB, Fig. 10). VO2 rose from 8 2 ml/min to 10 ± 2 ml/min. These effects were sustained for up to 120 s and significantly different from that with saline infusion (Fig. 8). Along with the recovery of these circulatory parameters, CgH2S dropped by half even though NaHS infusion was maintained at the same rate (Fig. 8). Two to three minutes later, MABP, CO, and HR decreased again returning toward the values observed during saline injection. The second injection of MB was able to produce a new increase in CO, arterial and ventricular pressures (Fig. 10). These 2 injections of MB led to a significantly longer survival time compared to that of saline infusion by about 2.5 min (p = 0.012, Fig. 11). More specifically, MB-treated rats’ survival time averaged 650 ± 112 s (median: 610 s, p = 0.0293 vs. all control rats). The ECG showed a sustained activity for 1050 ± 396 (median: 944) s. Interestingly, one of the MB-treated rats presented an episode of ventricular tachycardia during NaHS infusion, which recovered spontaneously; this rat presented a PEA later on at 830 s.

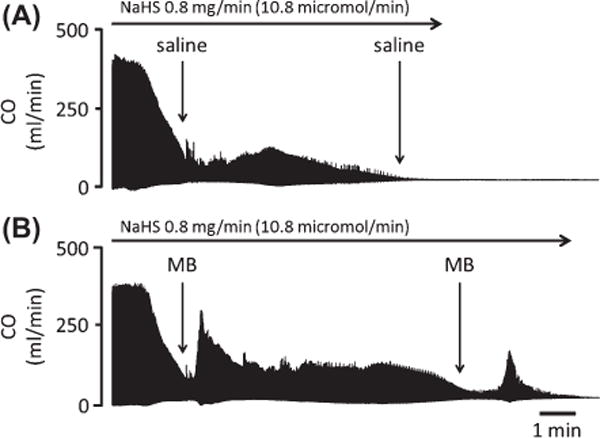

Fig. 7.

Effects of continuous infusion of NaHS (0.8 mg/min, 10.8 micromol/min) on CO in two rats. (A) Saline was injected intravenously as soon as CO decreased by ∼60%. CO became undetectable at 530 s. (B) Injection of 2 mg of MB, in another rat, induced a large increase in CO. CO was also able to rise following a second MB injection late into the period of intoxication. Time to PEA was prolonged by more than 2 min, when compared with saline injection.

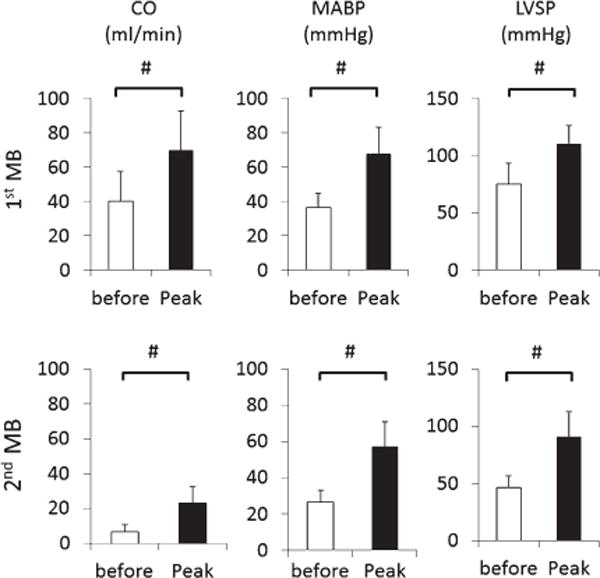

Fig. 10.

Mean ± SD values of CO, MABP, and LVSP before and after the first (top panel) and second (bottom panel) injections of 4 mg/kg of MB during NaHS infusion. For convenience, responses are 10-second averaged peak responses occurring 30 sec following MB injection. Both 1st and 2nd injection of MB produced significant increase in MABP and LVSP as well as CO. #Significantly different from pre-injection values (before), p < 0.05.

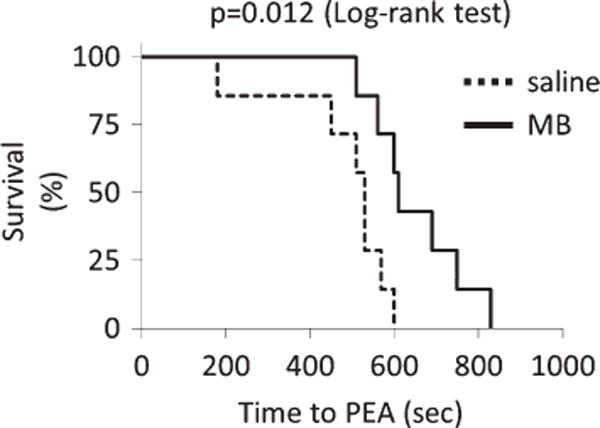

Fig. 11.

Survival curve (Kaplan–Meier plot) during continuous infusion of NaHS. In saline/control group, all animals died within 600 s with a median of 530 s, following the onset of NaHS infusion. MB-treated animal survived significantly longer than the control animals and died within 830 s of NaHS infusion (median: 610 s, p = 0.012 log-rank test).

Effects of MB versus saline injection in baseline condition

Figure 12 shows the circulatory changes before and after IV bolus injection of saline or MB at 2 different concentrations (1 and 4 mg/kg) in baseline condition (n = 8 for each injection). Bolus injection of 1-ml saline induced small and transient significant increase in MABP (+5 ± 2 mmHg, p < 0.05) and rise in CO (+11 ± 3 ml/min, p < 0.05) 20–30 s after the injection, which resulted in a decrease in peripheral resistance (−7 ± 4%). The injection of MB produced an increase in CO which was not different from the change produced by saline, averaging +11 ± 3 ml/min and +14 ± 6 ml/min 20–30 s after administration of 1 and 4 mg/kg of MB, respectively. The change in CO produced by MB appears, therefore, to be primarily related to the volume of solution injected. However, MABP increased up to 6 times more after 4 mg/kg of MB (+32 ± 6 mmHg) than after saline (p < 0.001). As a result, and in major contrast to saline infusion, peripheral resistance increased by 42 ± 9% after MB (p < 0.001, vs. saline).

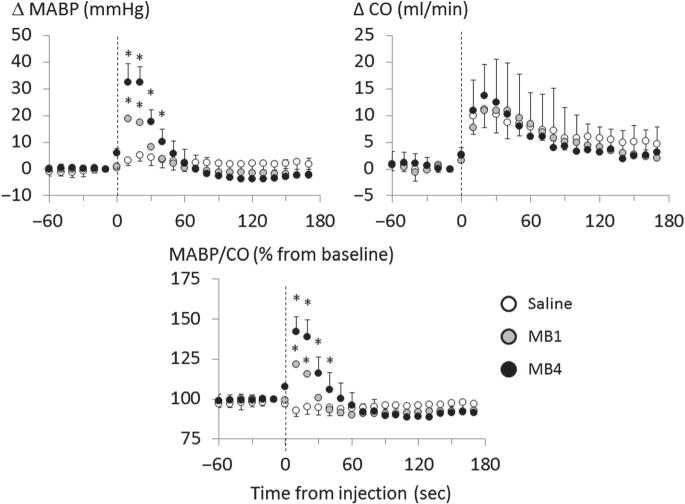

Fig. 12.

Averaged changes in MABP, CO, and % changes in MABP/CO ratio in 4 rats receiving saline (white circle), 1 mg/kg of MB (MB1, gray circle), and 4 mg/kg of MB (MB4, black circle) in baseline condition. Bolus injection of saline increased CO by 11 ml/min and MABP by 5 mmHg, but slightly decreased MABP/CO. Both 1 mg/kg and 4 mg/kg of MB increased CO, just like with saline. In contrast to saline infusion, 1 mg/kg and 4 mg/kg of MB increased MABP by 19 mmHg and 32 mmHg (peak response), respectively, along with MAP/CO, suggesting that, in baseline condition, the circulatory effects are primarily the result of a peripheral effect on the vascular tone, with little effect on cardiac function of MB. Values are shown as mean ± SD. *Significantly different from saline/control at p < 0.05.

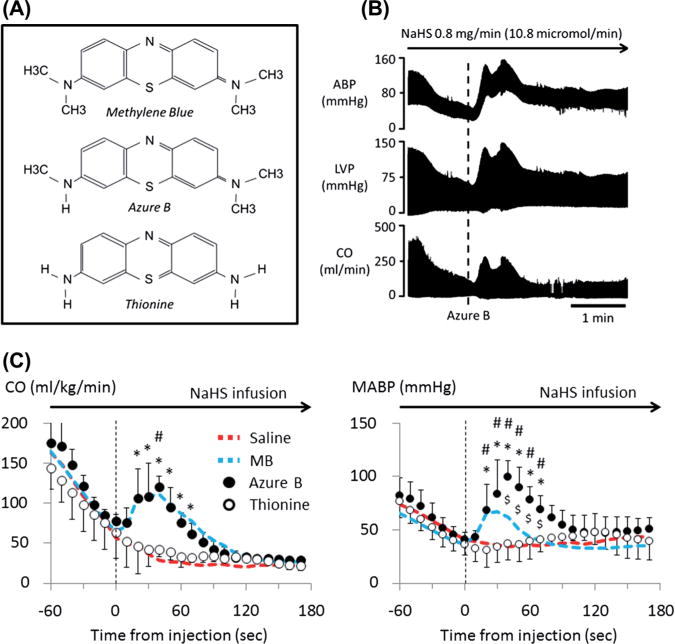

Effects of azure B and thionine

As shown in Fig. 13, the effects of azure B on CO were similar to those produced by MB. The only difference was that the increment in MABP was significantly higher and more prolonged than following MB (99 ± 16 vs. 67 ± 15 mmHg), while CgH2S dropped from 10.5 to 3.3 microM. In major contrast, thionine administration had the same effect as saline.

Fig. 13.

Circulatory effects of azure B and thionine during NaHS infusion. (A) Molecular structure of phenothiazine compounds MB, azure B, and thionine. MB is oxidized to mono-demethylated form, azure B. Thionine is a demethylated form of MB and Azure B. (B) Example of the effect of Azure B on cardiac function during sulfide intoxication. Azure B injected during the period of cardiogenic shock (vertical dashed line) induced large increase in arterial pressure and LVP. C) Mean ± SD values of CO and MABP in rats receiving thionine (open-circle) or 4 mg/kg of azure B (closed-circle) during NaHS infusion (n = 10). Data from the saline/control (red) and the MB (blue) group of rats shown in Fig. 8 are also displayed by dashed line. Thionine and azure B were injected at time 0 (vertical dashed line), and data were averaged every 10 s. The effects of thionine injection was not different from saline, in major contrast to azure B which had an effect on CO similar to MB, while the increase of MABP was significantly greater than the effects of MB. *Significantly different from saline/control, p < 0.05. #Significantly different from pre-injection values, p < 0.05. $Signify different from MB, p < 0.05.

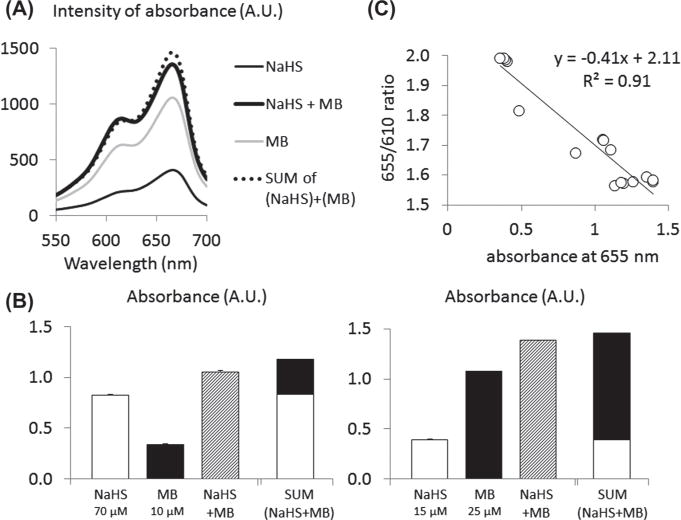

In vitro Interactions between MB and H2S

Figure 14A shows one example of the absorbance spectrum between 550 and 700 nm after final dilution by half of solutions containing 1- MB (25 microM) with reagents, 2- NaHS (15 microM) with reagents, and 3- MB + NaHS with reagents, for 2 min. The difference between the sum of absorbance at 665 nm of NaHS and MB solution and the absorbance of the solution containing both NaHS and MB averaged −7.4 ± 2.1% (Fig. 14B). Of note is that the peak absorbance, at 610 nm, thought to be associated with MB dimers, increases when the concentration of MB rises (Fig. 14C). This implies that the determination of the concentration of MB monomers may have underestimated the actual concentration of MB in the MB + NaHS solution as only the absorbance at 665 nm was used.

Fig. 14.

Interaction between H2S and MB in vitro. (A) Absorbance at 665 nm was measured in 3 solutions containing the reagents (see “Methods” section) and (1) NaHS (thin black line), (2) MB (gray line), and (3) NaHS + MB (black bold line). As NaHS with the reagents produces MB, the sum of absorbance of NaHS and MB (dashed line) should correspond to the absorbance of NaHS + MB solution. Absorbance of NaHS + MB solution was found with 7% of the sum of NaHS and MB absorbance taken separately. (B) Averaged absorbance at 665 nm (in triplicate). Left: absorbance of solutions containing the reagents with 1–70 microM NaHS, 2–10 microM MB, and 3–70 microM NaHS + 10 microM MB. Right: absorbance of solutions mixed with reagents containing 15 microM NaHS, 25 microM MB, and 15 microM NaHS + 25 microM MB. The sum of absorbance obtained from NaHS alone and MB alone is also depicted. Values are shown as mean ± SD (SD is too small to be seen on the figure). (C) Correlation between absorbance at 655 nm (corresponding to MB monomers) and the ratio of absorbance at 655 nm and 610 nm (MB dimers). This figure shows that the concentration in MB dimers increases as the concentration in MB monomers increases, details on the implications are given in the “Results” section.

Similar results were obtained while measuring H2S concentration by sulfide complexation with monobromobimane (CMBB H2S): H2S concentration in saline averaged 104 microM when 10 microM of MB was added into 100 microM NaHS solution.

Discussion

We found in non-sedated animals that the immediate mortality of H2S-induced coma was prevented by the injection of MB during the phase of agonal breathing, that is, after H2S exposure, while 75% of the animals died in the control group. Continuous infusion of lethal dose of NaHS, in a separate group of sedated animals, induced a rapid drop in CO and cardiac contractility leading to cardiac arrest by PEA. Intravenous administration of MB during the infusion produced a rapid rise in CO and cardiac functions during the phase cardiogenic shock produced by NaHS infusion. Bolus injections of MB (4 mg/kg) during the severe reduction in cardiac contractility induced by H2S did increase CO and ventricular pressure, a response that was not observed in baseline condition (i.e., without cardiac failure). The phenomenon persisted for more than 2 min and could even be produced when the CO was reduced by more than 90%. This transient restoration of cardiac contractility prolonged time to PEA. A similar effect was observed with azure B, a metabolite of MB, but not with its demethylated form, thionine.

H2S-induced cardiac dysfunction

NaHS infusion produces a marked decrease in cardiac function as soon as the concentration of dissolved H2S reached 2–3 microM. At a rate of infusion that would be lethal in less than 10 min, CO decreased by about 60% within 2 min, along with a decrease in left ventricular and thus arterial blood pressure, with no vasodilatory effects. In keeping with our previous report1,2 and the present data, we can postulate that the vasodilatory effects reported in vitro at a concentration of 50 microM and higher44,53–55 can only occur above the concentrations of H2S required to stop the heart. The powerful negative inotropic effects of H2S led to a complete electromechanical dissociation or PEA within minutes. As mentioned in the “Introduction” section, plausible mechanisms underlying NaHS-induced cardiac dysfunction comprise 1- an inhibition of calcium channels,4,5,56 mimicking an intoxication by calcium channel blockers, and 2- a potentiation of the effects of NO by H2S10,11 which in turn—just like in septic shock42,43—can lead to a profound depression in cardiac contractility. Finally, the reduction in ATP, via a complete blockage of the cytochrome C oxidase activity6,7 could have led to a depressed cardiac contractility, akin to the effects of cardiac anoxia.

MB and H2S

Whether the in vitro determination of H2S concentration was based on the production of MB50 or on the “monobromobimane technic”46,52 (Fig. 14), we did not find any significant interaction between soluble H2S and MB in saline at least within 2 min. A difference in H2S concentration of about 7%, at the most, was found when adding MB and H2S at similar orders of magnitude to those used in vivo.

While H2S does not appear to interact directly in vitro with MB, these results do not preclude MB to affect H2S metabolism in the tissue or the distribution of the pools of H2S between free gaseous H2S, HS-, and all the various forms of combined sulfides. Briefly, H2S is present in the blood46 in 2 distinct pools: first a gaseous form (CgH2S), which partial pressure is in equilibrium with the alveolar gas and with all tissues,57 and with the sulfhydryl anion HS,58,47 and second, a pool of H2S combined with various metalloproteins (e.g., the ferrous iron of hemoglobin) or proteins (e.g., cysteine residues),59,60 H2S in its gaseous form, being extremely soluble,57,61–63 diffuses immediately into the tissues or within the lungs and it is this form that was measured in our study. The majority of H2S oxidation takes place in the mitochondria,19,64 where H2S also expresses its main toxicity by blocking the cytochrome C activity and thus ATP formation. We have previously estimated the rate of elimination of H2S in vivo to be about 12 micromol/kg/min in severe intoxication,48 as the rate of infusion of our rat was as high as 16 micromol/kg/min, if MB was able to affect the rate of oxidation of sulfide by few %, whether through a direct effect or via it effects on tissular blood flow, a dramatic increase in H2S concentration is to be expected. Whether MB can affect the repartition of the various pools of sulfide in the blood due to its oxido-reducing properties remain to be also established.

Indeed, we did observe a drop in mixed FEH2S following MB or azure B administration. As CO dropped during H2S infusion, and then increased following MB injection, the concentration of H2S in the blood would be expected to increase and decrease, respectively, since the infusion rate of NaHS, in which concentration of sulfide is several orders of magnitude higher than that in the blood, remained constant. This led to a continuous increase in the infusion rate/CO ratio throughout the period of sulfide exposure (and immediate decrease in this ratio when the antidote was administered), which could account for a several fold increase or decrease on H2S concentration in the blood. We have already shown that during H2S infusion, moderate change in CO, by withdrawal and infusion of blood during continuous administration of NaHS, affects the concentration of exchangeable H2S in the blood in the opposite direction.48 Mixed FEH2S increases when CO decreases, and it decreases when CO increases. We have postulated that in addition to a “dilution–concentration mechanism,” the rate at which H2S combines to hemoglobin before reaching the lungs should decrease when CO decreases, that is, increasing in turn the pool of diffusible H2S. More importantly, the rate of disappearance of H2S depends critically on its oxidation in the tissues (liver, muscle, etc.) which is dictated by the rate of H2S delivery to the tissues. These factors can account for a decrease in free H2S in the blood when the level of CO is restored. This phenomenon could also explain the constant drift in H2S concentration throughout the period of exposure, while H2S infusion rate is constant (see Figs. 3, 6, and 8). This mechanism can be regarded as a form of deleterious positive feedback system (beneficial during the administration of the antidote): the progressive rise in H2S leads to a reduction in CO which in turn increases the level of soluble H2S in the blood and tissues until PEA occurs.

It is of note that the decrease in FEH2S that was observed when CO reached very low levels can be explained by the critical reduction in pulmonary blood flow and H2S flow to the lungs, analogous to the reduction in alveolar CO2 during severe drop in pulmonary blood flow. Due to the very high solubility of H2S in the blood, this only occurred when cardiac contractions became significantly impeded, with a CO of less than 10 ml/kg/min (see Fig. 6). As mentioned in the “Limitations” section, inhaled H2S will lead to a different effect, since severely diminished CO should in turn reduce H2S diffusion from the lungs into the blood.

Various treatments have been proposed against H2S poisoning, for example, hyperoxia,65,66 nitrite-induced methemoglobin,48,49,67–69 and hydroxocobalamin.2,48,49,70 The use of MB as an antidote for H2S intoxication represents a paradigm, which differs from the traditional strategy aimed at trapping or oxidizing H2S. We have suggested that this strategy is limited as gaseous H2S disappears very rapidly from the blood after cessation of exposure to sulfide.46,71

MB has been used as an anti-NO agent which inhibits NOS72 and soluble GC.73 Since 1- NO appears to exert inhibitory effects on the cardiac contractility,74 a phenomenon which has been proposed to account for the cardiogenic component of a septic shock, and 2- NO potentiates the effects of H2S,10,11,44,55 any compounds with some anti-NO properties could result in an improvement in circulation. During H2S poisoning, when CO falls, this anti-NO property could have therefore provided some positive inotropic effect. This hypothesis would imply that one of the mechanisms of H2S-induced cardiac depression is acting though a NO-related pathway, a contention, which has been suggested,10,11,44,55 but which certainly remains to be proven. In addition, whether the very rapid effect of MB is compatible with such a mechanism can be debated.

A second putative mechanism relates to the observation that MB is capable of maintaining a proton gradient across the mitochondrial membrane in conditions wherein the shift of protons is impeded by the blockade of cytochrome C oxidase activity.15 This effect has been put forward to explain the beneficial effects of MB during sodium azide21 or cyanide24 poisoning. Both these agents share the same inhibitory effect on mitochondrial function as H2S. Finally, MB may have antagonized the blocking effects of H2S on calcium channels.75,76

MB versus other phenothiazinium chromophores

Many chemical derivatives of MB are used as dyes, antiseptics, antimalarial drugs, or oxido-reducing agents.12 The central thiazine ring shared by all these compounds can be quite misleading as most of the members of this family are different from a chemical stand point. It is clear that azure B solution, which has a purity of about 89%, produced effects on blood pressure which were more powerful than MB, while their effects on CO were similar. Recently, it has been suggested that a large part of the effects of MB may be accounted for azure B, its main metabolite in the body.13,14 Azure B, which contains 3 methyl groups instead of 4 as for MB (Fig. 13), has been proposed to be more effective than MB in reducing the mortality of septic shock;77 very large doses of MB or azure B were used in that study. Similarly, azure B has been shown to be a much more potent monoamine oxidase inhibitor than MB.78 One of the possible mechanisms which might account for this “superiority” of azure B could rely on the presence of one NH-CH3 group instead of N-(CH3)2 in MB, allowing a quinoneimine compound to be formed leading to a better diffusion of azure B molecules.14 Thionine, a completely demethylated form of MB, had however no effects on H2S toxicity. This suggests that the presence of methyl groups in phenothiazine chromophores plays a fundamental role in counteracting the circulatory effects of sulfide poisoning.

Limitations

Animal models of H2S-induced comas represent a clinically relevant approach, faithful to human poisoning,3,79 which have been previously used to test the benefit on sulfide antidote. Our animal model differs from previous models of coma,79 in the sense that it was not the outcome of H2S poisoning per se that we were investigating but rather the outcome of the coma produced by H2S. With the present model, we could produce a coma in 40% of animals after the first IP injection of NaHS, while a second injection 10 min later was able to produce a coma in a much higher percentage of cases, without affecting the characteristic of the coma and its mortality (Fig. 2). The latter averaged 75%. Death occurred very rapidly while the animals are presenting agonal breathing. MB administered during the agonal phase was able to restore eupneic breathing and circulation, preventing death. These effects, akin to the cardiovascular effects observed in our anesthetized animals, suggest that the reduction in cardiac function is certainly an important contributor of the short-term outcome of sulfide poisoning.

In contrast to sulfide inhalation, infusion of H2S (IP or IV) does not produce a pulmonary edema, unless it is infused over a relatively long period of time (30 min or more), therefore at lower levels. At least in our hands, a protocol, which kills within 10 min or so, does not produce any change in PaO2 or clinical evidence for a pulmonary edema. This was also true for the animals that recovered rapidly from H2S-induced coma. In our experience, pulmonary edema will only be present if the animal is resuscitated by CPR maneuvers and epinephrine injection—this is also true in larger mammals.2 This difference between the effects of inhaled and infused sulfide has already been described by Lopez et al.,80 who found very similar results, that is, lack of pulmonary edema during lethal infusion of H2S, in contrast to inhaled exposure. In addition, we found that the peak values of alveolar H2S for 10 min were not high enough to produce any significant lung toxicity, since a similar rat model would require at least 400 ppm for one hour to produce a pulmonary edema.81

As mentioned above, another major issue with infused sulfide is the fact that as CO drops, the concentration of H2S increases in the blood since the rate of sulfide infusion remains unchanged. This continuous increase in the infusion rate/CO ratio throughout the period of sulfide exposure will create a positive feedback system, which does not occur during H2S intoxication by inhalation. In the latter, the rate of diffusion of H2S will be in large part limited by the reduction in pulmonary blood flow. As a consequence, infusion of sulfide represents a more severe model of intoxication than a model using inhaled H2S gas.

MB at a dose of 2 mg/kg is the treatment recommended for methemoglobinemia in humans. Higher doses seem to be harmless until a dose of 10 mg/kg is used.82,83 Incidentally, many studies have used a dose of MB higher than 2 mg/kg in shock,82,84,85 although duration of infusion was very variable among studies. There is no rational for using MB in a rat as a protection against H2S poisoning at the dose recommended for treating methemoglobinemia in humans. Since, as shown in Fig. 12, the cardiovascular response to MB was the largest at 4 mg/kg, this is the dose that was chosen.

Finally, it is obvious that the thoracotomy and the sedation may have blunted some of the effects of our compounds and/or magnified some of the outcomes of H2S toxicity, creating for instance much more “fragile” animal model. Since the same surgical preparation was used in our 4 groups (saline, MB, azure B, and thionine), we assume that the specificities of our model could not account, by itself, for the present findings.

Conclusions

H2S poisoning produces a rapid depression in cardiac function at concentration of tens of microM of soluble H2S in the blood. This effect tends to speed up the rate of H2S accumulation in the blood and thus in the tissues, leading to PEA within minutes. MB, which does not appear to interact with H2S in vitro, increases cardiac contractility during sulfide poisoning and can prolong survival time by more than 35% when compared with the saline group while sulfide is continuously infused. In un-anesthetized animals, which displayed a coma following IP NaHS, injecting MB during the agonal phase was able to prevent the animal from dying, allowing recovery with no obvious immediate clinical motor or behavioral deficit. Thionine, which is a completely demethylated form of MB, had no effects on H2S intoxication, while azure B displayed similar effects than MB, but with a larger increase in blood pressure. Both the mechanisms of action as well as the long-term effects of MB remain to be determined.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ms. Nicole Tubbs for her skillful technical assistance. This work has been supported by the CounterACT Program, National Institutes of Health Office of the Director (NIH OD), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), Grant Numbers: 1R21NS080788-01 and 1R21NS090017-01.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Sonobe T, Haouzi P. Sulfide Intoxication-Induced Circulatory Failure is Mediated by a Depression in Cardiac Contractility. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12012-015-9309-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haouzi P, Chenuel B, Sonobe T. High-dose hydroxocobalamin administered after H2S exposure counteracts sulfide-poisoning-induced cardiac depression in sheep. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015;53:28–36. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.990976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldelli RJ, Green FH, Auer RN. Sulfide toxicity: mechanical ventilation and hypotension determine survival rate and brain necrosis. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1993;75:1348–1353. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.3.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun YG, Cao YX, Wang WW, Ma SF, Yao T, Zhu YC. Hydrogen sulphide is an inhibitor of L-type calcium channels and mechanical contraction in rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:632–641. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang R, Sun Y, Tsai H, Tang C, Jin H, Du J. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits L-type calcium currents depending upon the protein sulfhydryl state in rat cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper CE, Brown GC. The inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase by the gases carbon monoxide, nitric oxide, hydrogen cyanide and hydrogen sulfide: chemical mechanism and physiological significance. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:533–539. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan AA, Schuler MM, Prior MG, Yong S, Coppock RW, Florence LZ, Lillie LE. Effects of hydrogen sulfide exposure on lung mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1990;103:482–490. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90321-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rastaldo R, Pagliaro P, Cappello S, Penna C, Mancardi D, Westerhof N, Losano G. Nitric oxide and cardiac function. Life Sci. 2007;81:779–793. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brady AJ, Poole-Wilson PA, Harding SE, Warren JB. Nitric oxide production within cardiac myocytes reduces their contractility in en-dotoxemia. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H1963–H1966. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coletta C, Papapetropoulos A, Erdelyi K, Olah G, Modis K, Panopoulos P, Asimakopoulou A, Gero D, Sharina I, Martin E, Szabo C. Hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide are mutually dependent in the regulation of angiogenesis and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9161–9166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202916109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altaany Z, Yang G, Wang R. Crosstalk between hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide in endothelial cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17:879–888. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wainwright M, Amaral L. The phenothiazinium chromophore and the evolution of antimalarial drugs. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:501–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warth A, Goeppert B, Bopp C, Schirmacher P, Flechtenmacher C, Burhenne J. Turquoise to dark green organs at autopsy. Virchows Arch. 2009;454:341–344. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0734-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schirmer RH, Adler H, Pickhardt M, Mandelkow E. Lest we forget you – methylene blue…. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:2325–e7. e16. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X, Rojas JC, Gonzalez-Lima F. Methylene blue prevents neurodegeneration caused by rotenone in the retina. Neurotox Res. 2006;9:47–57. doi: 10.1007/BF03033307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott A, Hunter FE., Jr Support of thyroxine-induced swelling of liver mitochondria by generation of high energy intermediates at any one of three sites in electron transport. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:1060–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindahl PE, Oberg KE. The effect of rotenone on respiration and its point of attack. Exp Cell Res. 1961;23:228–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callaway NL, Riha PD, Bruchey AK, Munshi Z, Gonzalez-Lima F. Methylene blue improves brain oxidative metabolism and memory retention in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;77:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouillaud F, Blachier F. Mitochondria and sulfide: a very old story of poisoning, feeding, and signaling? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:379–391. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckler KJ. Effects of exogenous hydrogen sulphide on calcium signalling, background (TASK) K channel activity and mitochondrial function in chemoreceptor cells. Pflugers Arch. 2012;463:743–754. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1089-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riha PD, Rojas JC, Gonzalez-Lima F. Beneficial network effects of methylene blue in an amnestic model. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2623–2634. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callaway NL, Riha PD, Wrubel KM, McCollum D, Gonzalez-Lima F. Methylene blue restores spatial memory retention impaired by an inhibitor of cytochrome oxidase in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002;332:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00827-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahlin B. The antagonism between methylene blue and cyan potassium. Skandinavisches Archiv Fur Physiologie. 1926;47:284–291. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eddy NB. Antagonism between Methylene Blue and Sodium Cyanide. J Pharmacol & Exper Therap. 1930;39:271. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martijn C, Wiklund L. Effect of methylene blue on the genomic response to reperfusion injury induced by cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in porcine brain. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miclescu A, Basu S, Wiklund L. Methylene blue added to a hypertonic-hyperoncotic solution increases short-term survival in experimental cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2806–2813. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000242517.23324.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miclescu A, Basu S, Wiklund L. Cardio-cerebral and metabolic effects of methylene blue in hypertonic sodium lactate during experimental cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2007;75:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiklund L, Basu S, Miclescu A, Wiklund P, Ronquist G, Sharma HS. Neuro- and cardioprotective effects of blockade of nitric oxide action by administration of methylene blue. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1122:231–244. doi: 10.1196/annals.1403.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiklund L, Zoerner F, Semenas E, Miclescu A, Basu S, Sharma HS. Improved neuroprotective effect of methylene blue with hypothermia after porcine cardiac arrest. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:1073–1082. doi: 10.1111/aas.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ginimuge PR, Jyothi SD. Methylene blue: revisited. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2010;26:517–520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin W, Villani GM, Jothianandan D, Furchgott RF. Selective blockade of endothelium-dependent and glyceryl trinitrate-induced relaxation by hemoglobin and by methylene blue in the rabbit aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;232:708–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olgart C, Wiklund NP, Gustafsson LE. Blockade of nitric oxide-evoked smooth muscle contractions by an inhibitor of guanylyl cyclase. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3355–3358. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199710200-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin RL, Degrange MA, Bruno GF, Del Mazo CD, Taborda DJ, Griotti JJ, Boullon FJ. Methylene blue reduces mortality and morbidity in vasoplegic patients after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:496–499. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gachot B, Bedos JP, Veber B, Wolff M, Regnier B. Short-term effects of methylene blue on hemodynamics and gas exchange in humans with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:1027–1031. doi: 10.1007/BF01700666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grayling M, Deakin CD. Methylene blue during cardiopulmonary bypass to treat refractory hypotension in septic endocarditis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:426–427. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kofidis T, Struber M, Wilhelmi M, Anssar M, Simon A, Harringer W, Haverich A. Reversal of severe vasoplegia with single-dose methylene blue after heart transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:823–824. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.115153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menardi AC, Capellini VK, Celotto AC, Albuquerque AA, Viaro F, Vicente WV, Rodrigues AJ, Evora PR. Methylene blue administration in the compound 48/80-induced anaphylactic shock: hemodynamic study in pigs. Acta Cir Bras. 2011;26:481–489. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502011000600013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evora PR, Ribeiro PJ, de Andrade JC. Methylene blue administration in SIRS after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1212–1213. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egi M, Bellomo R, Langenberg C, Haase M, Haase A, Doolan L, Matalanis G, Seevenayagam S, Buxton B. Selecting a vasopressor drug for vasoplegic shock after adult cardiac surgery: a systematic literature review. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:715–723. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leyh RG, Kofidis T, Struber M, Fischer S, Knobloch K, Wachsmann B, Hagl C, Simon AR, Haverich A. Methylene blue: the drug of choice for catecholamine-refractory vasoplegia after cardiopulmonary bypass? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:1426–1431. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(02)73284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donati A, Conti G, Loggi S, Munch C, Coltrinari R, Pelaia P, Pietropaoli P, Preiser JC. Does methylene blue administration to septic shock patients affect vascular permeability and blood volume? Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2271–2277. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200210000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preiser JC, Lejeune P, Roman A, Carlier E, De Backer D, Leeman M, Kahn RJ, Vincent JL. Methylene blue administration in septic shock: a clinical trial. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:259–264. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paciullo CA, McMahon Horner D, Hatton KW, Flynn JD. Methylene blue for the treatment of septic shock. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:702–715. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ali MY, Ping CY, Mok YY, Ling L, Whiteman M, Bhatia M, Moore PK. Regulation of vascular nitric oxide in vitro and in vivo; a new role for endogenous hydrogen sulphide? Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:625–634. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tupper DE, Wallace RB. Utility of the neurological examination in rats. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 1980;40:999–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klingerman CM, Trushin N, Prokopczyk B, Haouzi P. H2S concentrations in the arterial blood during H2S administration in relation to its toxicity and effects on breathing. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R630–R638. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00218.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Millero FJ. The Thermodynamics and Kinetics of the Hydrogen-Sulfide System in Natural-Waters. Mar Chem. 1986;18:121–147. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haouzi P, Sonobe T, Torsell-Tubbs N, Prokopczyk B, Chenuel B, Klingerman CM. In Vivo Interactions Between Cobalt or Ferric Compounds and the Pools of Sulphide in the Blood During and After H2S Poisoning. Toxicol Sci. 2014;141:493–504. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van de Louw A, Haouzi P. Ferric Iron and Cobalt (III) compounds to safely decrease hydrogen sulfide in the body? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:510–516. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van de Louw A, Haouzi P. Oxygen deficit and H2S in hemorrhagic shock in rats. Crit Care. 2012;16:R178. doi: 10.1186/cc11661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siegel LM. A Direct Microdetermination for Sulfide. Anal Biochem. 1965;11:126–132. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(65)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wintner EA, Deckwerth TL, Langston W, Bengtsson A, Leviten D, Hill P, Insko MA, Dumpit R, VandenEkart E, Toombs CF, Szabo C. A monobromobimane-based assay to measure the pharmacokinetic profile of reactive sulphide species in blood. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:941–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, Meng Q, Mustafa AK, Mu W, Zhang S, Snyder SH, Wang R. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science. 2008;322:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H(2)S as a novel endogenous gaseous K(ATP) channel opener. EMBO J. 2001;20:6008–6016. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hosoki R, Matsuki N, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:527–531. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Munaron L, Avanzato D, Moccia F, Mancardi D. Hydrogen sulfide as a regulator of calcium channels. Cell Calcium. 2013;53:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carroll JJ, Mather AE. The solubility of hydrogen-sulfide in water from 0 ° C to 90°C and Pressures to 1-Mpa. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta. 1989;53:1163–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Almgren T, Dyrssen D, Elgquist B, Johannsson O. Dissociation of hydrogen sulfide in seawater and comparison of pH scales. Mar Chem. 1976;4:289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Warenycia MW, Goodwin LR, Francom DM, Dieken FP, Kombian SB, Reiffenstein RJ. Dithiothreitol liberates non-acid labile sulfide from brain tissue of H2S-poisoned animals. Arch Toxicol. 1990;64:650–655. doi: 10.1007/BF01974693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Sen N, Kim S, Mu W, Gazi SK, Barrow RK, Yang G, Wang R, Snyder SH. H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra72. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Bruyn WJ, Swartz E, Hu JH, Shorter JA, Davidovits P, Worsnop DR, Zahniser S, Kolb CE. Henry’s law solubilities and Setchenow coefficients for biogenic reduced sulfur species obtained from gas-liquid uptake measurements. J Geophys Res. 1995;100:7245–7251. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Douabul AA, Riley JP. The solubility of gases in distilled water and seawater – V. Hydrogen sulphide. Deep-Sea Research. 1979;26A:259–268. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barrett TJ, Anderson GM, Lugowski JT. The solubility of hydrogen sulphide in 0–5 m NaCl solutions at 25–95 C and one atmosphere. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1988;52:807–811. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lagoutte E, Mimoun S, Andriamihaja M, Chaumontet C, Blachier F, Bouillaud F. Oxidation of hydrogen sulfide remains a priority in mammalian cells and causes reverse electron transfer in colonocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:1500–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitcraft DD, 3rd, Bailey TD, Hart GB. Hydrogen sulfide poisoning treated with hyperbaric oxygen. J Emerg Med. 1985;3:23–25. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(85)90215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smilkstein MJ, Bronstein AC, Pickett HM, Rumack BH. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for severe hydrogen sulfide poisoning. J Emerg Med. 1985;3:27–30. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(85)90216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith L, Kruszyna H, Smith RP. The effect of methemoglobin on the inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase by cyanide, sulfide or azide. Biochem Pharmacol. 1977;26:2247–2250. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(77)90287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith RP, Gosselin RE. On the mechanism of sulfide inactivation by methemoglobin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1966;8:159–172. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(66)90112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith RP, Gosselin RE. The influence of methemoglobinemia on the lethality of some toxic anions. Ii. Sulfide. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1964;6:584–592. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(64)90090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Truong DH, Mihajlovic A, Gunness P, Hindmarsh W, O’Brien PJ. Prevention of hydrogen sulfide (H2S)-induced mouse lethality and cytotoxicity by hydroxocobalamin (vitamin B(12a)) Toxicology. 2007;242:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haouzi P, Chenuel B, Sonobe T, Klingerman CM. Are H2S-trapping compounds pertinent to the treatment of sulfide poisoning? Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014;52:566. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.923906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mayer B, Brunner F, Schmidt K. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis by methylene blue. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;45:367–374. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gruetter CA, Kadowitz PJ, Ignarro LJ. Methylene blue inhibits coronary arterial relaxation and guanylate cyclase activation by nitroglycerin, sodium nitrite, and amyl nitrite. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1981;59:150–156. doi: 10.1139/y81-025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Flesch M, Kilter H, Cremers B, Lenz O, Sudkamp M, Kuhn-Regnier F, Bohm M. Acute effects of nitric oxide and cyclic GMP on human myocardial contractility. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:1340–1349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aggarwal N, Kupfer Y, Seneviratne C, Tessler S. Methylene blue reverses recalcitrant shock in beta-blocker and calcium channel blocker overdose. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 Jan;18:1–2. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jang DH, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS. Methylene blue in the treatment of refractory shock from an amlodipine overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:565–567. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Culo F, Sabolovic D, Somogyi L, Marusic M, Berbiguier N, Galey L. Anti-tumoral and anti-inflammatory effects of biological stains. Agents Actions. 1991;34:424–428. doi: 10.1007/BF01988739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petzer A, Harvey BH, Wegener G, Petzer JP, Azure B. A metabolite of methylene blue, is a high-potency, reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;258:403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Almeida AF, Nation PN, Guidotti TL. Mechanism and treatment of sulfide-induced coma: a rat model. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27:287–293. doi: 10.1080/10915810802210166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lopez A, Prior MG, Reiffenstein RJ, Goodwin LR. Peracute toxic effects of inhaled hydrogen sulfide and injected sodium hydrosulfide on the lungs of rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1989;12:367–373. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(89)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lopez A, Prior M, Lillie LE, Gulayets C, Atwal OS. Histologic and ultrastructural alterations in lungs of rats exposed to sub-lethal concentrations of hydrogen sulfide. Vet Pathol. 1988;25:376–384. doi: 10.1177/030098588802500507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cheng X, Pang CC. Pressor and vasoconstrictor effects of methylene blue in endotoxaemic rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1998;357:648–653. doi: 10.1007/pl00005220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haggard HW, Greenberg LA. Methylene blue a synergist, not an antidote, for carbon monoxide. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1933;100:2001–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paya D, Gray GA, Stoclet JC. Effects of methylene blue on blood pressure and reactivity to norepinephrine in endotoxemic rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993;21:926–930. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199306000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Young JD, Dyar OJ, Xiong L, Zhang J, Gavaghan D. Effect of methylene blue on the vasodilator action of inhaled nitric oxide in hypoxic sheep. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:511–516. doi: 10.1093/bja/73.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]