Abstract

Introduction

As one of the leading causes of death and disability in the world, human trauma and injury disproportionately affects individuals in developing countries. To meet the need for improved trauma care in Egypt, the Sequential Trauma Emergency/Education ProgramS (STEPS) course was created through the collaborative effort of U.S. and Egyptian physicians. The objective of course development was to create a high quality, modular, adaptable and sustainable trauma care course that could be readily adopted by a lower- or middle- income country.

Methods

We describe the development, transition and host-nation sustainability of a trauma care training course between a high income Western nation and a lower-middle income Middle Eastern/Northern African country, including number of physicians trained and challenges to program development and sustainability.

Results

STEPS was developed at the University of Maryland, based in part on World Health Organization’s Emergency and Trauma Care materials, and introduced to the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) and Ain Shams University in May 2006. To date, 639 physicians from multiple specialties have taken the 4-day course through the MOHP or public/governmental universities. In 2008, the course transitioned completely to the leadership of Egyptian academic physicians. Multiple Egyptian medical schools and the Egyptian Emergency Medicine Board now require STEPS or its equivalent for physicians in training.

Conclusions

Success of this collaborative educational program is demonstrated by the numbers of physicians trained, the adoption of STEPS by the Egyptian Emergency Medicine Board, and program continuance after transitioning to in-country leadership and trainers.

Introduction

As one of the leading causes of death and disability in the world, human trauma and injury disproportionately affects individuals in developing countries. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), road traffic crashes alone injure between 20 and 50 million individuals and kill 1.24 million people worldwide per year.1 The majority of individuals affected are young adults, especially men, from low-income and middle-income countries.1,2 The Eastern Mediterranean Region has some of the highest injury burden in the world, and Egypt, as a lower middle-income country in this region, has a particularly high burden of injury with a need for trauma care systems infrastructure development.3,4 Estimates of the road traffic death from injuries vary from 7,400 to 12,300 depending on the source and the year.5,6 However, these are likely underestimates, especially considering the relatively poor transportation infrastructure, limited enforcement efforts and as well as the general driving behavior of the population.

The Injury Prevention Research Training in Egypt and the Middle East program, supported through grants from the National Institutes of Health’s Fogarty International Center, was designed to help the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) and other Egyptian health professionals increase their knowledge and understanding of human trauma and injury prevention. It was also designed to help them apply this knowledge in public health and clinical practice in order to decrease the significant morbidity and mortality caused by injuries. During initial program development, senior MOHP physicians stated there was a critical need for a portable and flexible educational course on the clinical care of injured patients. The need was based upon the recognition of the multiple fatalities and injuries occurring on the roads in Cairo and other areas in Egypt, as well as frequent major transportation disasters. The Advanced Trauma Life Support Course® was not available in Egypt. In response to this need, we developed a comprehensive educational program titled Sequential Trauma Education ProgramS (STEPS). This paper describes course development from 2006–2013, highlighting the challenges and solutions of creating a successful and sustainable in-country trauma care training program.

Methods

Curriculum Development

STEPS was developed in 2006 at the University of Maryland, based in part on WHO’s emergency and surgical care materials and designed to introduce course participants to basic concepts of injury management. Following award of the NIH Fogarty grant to develop injury prevention research training, Egyptian officials at the MOHP and Ain Shams University requested that the University of Maryland faculty provide the American College of Surgeons Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS™) course. This was not possible at the time due to the lack of in-country infrastructure required by the international ATLS™ process, implementation costs, and difficulty in adapting it to limited resource settings. Implementation costs included the development of the training infrastructure, the need to import certified trainers for courses, and the costs related to accreditation. Often, ATLS™ is not applicable to low and middle income countries since it is designed for clinical scenarios in high-income countries that have access to computerized tomography (CT scan), massive transfusion resources, and interventional radiology. STEPS includes the basic "ABCDEs" of ATLS™ but also incorporates more basic techniques for resource-poor environments as promoted by the World Health Organization. As an alternative, we created a course based upon current scientific knowledge that was flexible enough to meet the needs of health care providers functioning in well-equipped, tertiary level centers, and also in resource-poor environments. We began by contacting the (WHO) to request use of the Integrated Management for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care toolkit7; the faculty of the Liverpool Hospital in Sydney Australia who were running a successful trauma care training program in India8; the Defense Military Operations office in charge of training U.S. military prior to combat missions; and consulting the trauma guidelines handbook from the R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, USA, to create STEPS.

Course Content

STEPS was designed in an effort to contain modular units - from basic to advanced - that could be adapted to any given environment; that is, hospitals that contain clinical resources as in a high-income nation and rural clinics that have little diagnostic or treatment modalities. The course content includes trauma care basics for physicians, from pre-hospital to initial resuscitation, anesthetic, and surgical management. The material is covered through a combination of didactic lectures, interactive sessions (radiology review, splinting workshop, airway workshop), and a ½ day veterinary procedure laboratory. For the animal lab, dogs are selected 3 weeks prior to a course, vaccinated and quarantined. The veterinary hospital is organized into a lecture area and a large OR suite with 5 individual stations, each with an anesthetized animal, surgical equipment and full protective gear for the staff and participants. A typical course schedule has been included as a supplement to highlight the various topics covered.

Course Implementation

The first two courses (2006 and 2007) were held with only U.S. trainers. From these courses we learned that objective structured clinical evaluations (OSCE’s) were needed to aid in the evaluation of course participants, as multiple-choice exams were relatively unknown to the Egyptian physicians at that time. Subsequently, to encourage course sustainability and continuity, a ‘ train-the-trainer’ process was implemented in order to transition control of the course to in-country. The subsequent five courses were a transition phase incorporating experienced Egyptian clinicians as lecturers and pairing them with a U.S. physician. The fifteen courses subsequent to these have been run entirely by Egyptians. Our stated aim was to create an independent didactic activity primarily organized and conducted by Egyptian physicians.

RESULTS

Course Participants

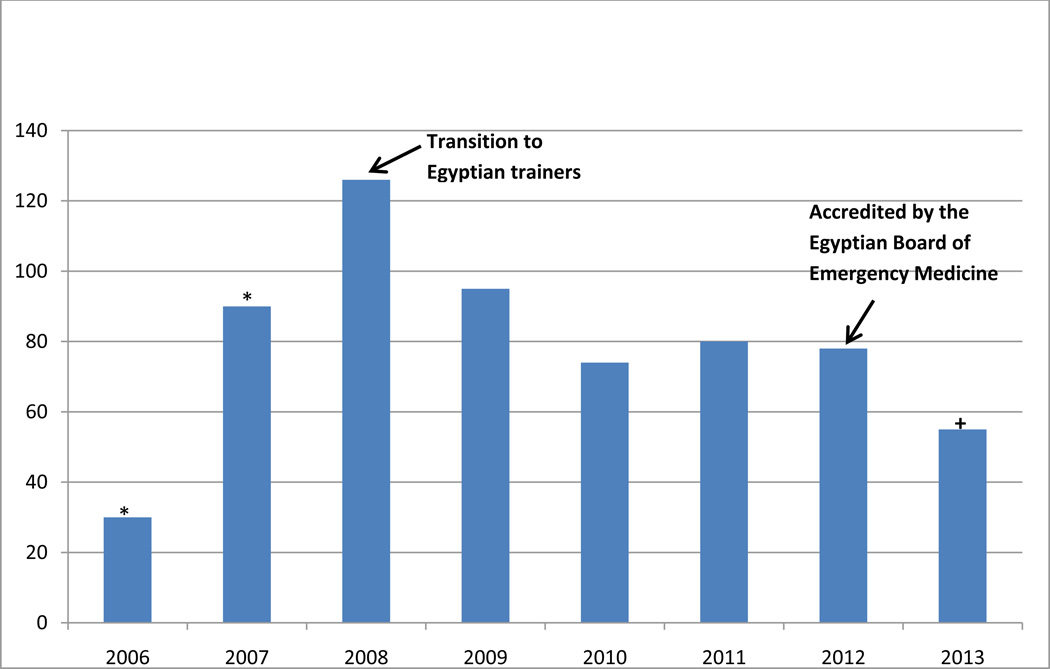

A total of 22 courses have been conducted to date: 10 at the National Training Institute of the Egyptian MOHP, 9 in Ain Shams University, Cairo, and 3 in Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt. Course participants have primarily included surgeons, anesthesiologists, emergency physicians, orthopedists, and neurosurgeons. Participants have come from academia, the Egyptian Board of Emergency Medicine, private hospitals, and private companies (e.g. petroleum industry). Since October 2008, courses have been taught primarily or solely by Egyptian trainers. Course size is limited (ideally <30) and has ranged from 20 to 37 students. A total of 639 students, primarily from Egypt, but also from Sudan, Palestine, Syria, Yemen and Saudi Arabia have been trained in STEPS (FIG. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Number of Sequential Trauma Emergency/Education ProgramS (STEPS) Trainees per Year, 2006–2013.

* Estimated number; + Partial Year

Implementation Challenges

During initial implementation, there were multiple logistical challenges as well as the need to develop shared expectations. For example, there was the desire to develop a Focused Abdominal Sonography for Trauma ultrasound module, but due in part to the high expenses of portable ultrasound machines, this was not done. Due to cultural sensitivities, the use of a cadaver procedure laboratory was not possible, so a veterinary procedure laboratory was developed. Different anesthetized animals, including sheep and goats, were utilized before deciding to use dogs. Language barriers also occurred. While medical education in most Middle Eastern countries is conducted in English, the level of English comprehension by the trainees varied. Most of the course implementation challenges were addressed through the integration of senior Egyptian physicians during the first 5 courses, and then careful choosing of trainers from the initial cohort of trainees.

Maintaining course continuity and quality were key challenges during the turnover to in-country leadership. There is a STEPS oversight committee that reviews and approves new sites for course delivery. Also, there is significant communication between sites and the use of a number of the same trainers at the different courses. Additionally, the high quality course organization and material has been maintained though periodic involvement by U.S. physicians as guest lecturers as well as an external audit in April 2013 by two academic physicians from the USA. (MM, ACS)

Sustainability Challenges

Since its initial deployment in 2006, the STEPS course has become an independent didactic activity primarily organized and conducted by Egyptian physicians. This has occurred through sustained and committed leadership in Egypt and the dissemination of the course to multiple Faculties of Medicine in Egypt. Through partnerships with key individuals within the MOHP, the Egyptian Board of Emergency Medicine and the Egyptian Society of Intensive care and Trauma “NGO” and the Regional WHO office in Egypt, the Egyptian Board of Emergency Medicine has accredited STEPS. The STEPS course or its equivalent is now required for all emergency medicine trainees by the Egyptian Board of Emergency Medicine and is being included in the curriculum of the Masters in Emergency Medicine being offered by Alexandria University. Official accreditation by the Egyptian Medical Syndicate, the highest physician organization within Egypt, is currently in progress.

DISCUSSION

We have learned a number of important lessons throughout this project. First, working directly with the MOHP was difficult primarily because our key contacts changed frequently and political considerations often delayed or deferred important decisions. These delays retarded our initial efforts by 18 to 24 months. After refocusing the project partnership between academic institutions (University of Maryland and Ain Shams University), STEPS rapidly became a consistent and desired educational course. Sustainability required committed in-country leadership and clear communication about the expectations for course development. Considering the current circumstances in Egypt, challenges remain in providing a high quality, self-sustaining educational trauma training course that provides young physician with didactic training which is specific, high quality and consistent. Providing this training increases the likelihood of surgeons, anesthesiologists, and emergency physicians being successful in trauma team performance, appropriate resuscitation and potentially improved outcomes in the treatment of the injured.

CONCLUSION

The STEPS educational program has fostered the growth of key relationships between U.S. and Egyptian leaders in emergency medicine and trauma surgery, while allowing for important education and research into implementing practice-changing educational programs in a developing country. We believe that we have made significant progress in emergency care capacity in Egypt and have demonstrated sustainability based on seven years of course conduct, and present here our experience in the process of transitioning trauma care training from a high-income (U.S.) to a low-middle income (Egypt) country. We hope lessons we have learned, as well as our program, can be disseminated and implemented in other lower-and middle-income countries, particularly in the Middle East and sub-Saharan African countries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge funding support from National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center Grant 5D43TW007296.

Abbreviations

- STEPS

Sequential Trauma Emergency/Education ProgramS

- WHO

World Health Organization

- MOHP

Ministry of Health and Population

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions: MES is the lead trainer for the program and had a primary role in conceiving and drafting the manuscript; MM developed the educational program and helped with conceiving the manuscript and its development and review; ACS assisted with program and manuscript development; MES helped with manuscript development and editing; JMH is the program lead and had a primary role in conception, drafting and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The International Acute Care Research Collaborative (IACRC), located within the University of Maryland Global Health Initiative, is dedicated to saving lives and limbs through improvement in the global access and quality of acute care services. This is accomplished through groundbreaking research and strategic advocacy efforts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Road traffic injuries. Geneva: World Health Organization; [Accessed 8.December.2013]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs358/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith GS, Barss PG. Unintentional injuries in developing countries: the epidemiology of a neglected problem. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1991;13:228–266. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soori H, Hussain SJ, Razzak JA. Road safety in the Eastern Mediterranean Region--findings from the Global Road Safety Status Report. East Mediterr Health J. 2011 Oct;17(10):770–776. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.10.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puvanachandra P, Hoe C, El-Sayed HF, Saad R, Al-Gasseer N, Bakr M, Hyder AA. Road traffic injuries and data systems in Egypt: addressing the challenges. Traffic Inj Prev. 2012;13(Suppl 1):44–56. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2011.639417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global status report on road safety 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization; [Accessed 8.December.2013]. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2013/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global status report on road safety: time for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; [Accessed 8.December.2013]. Available from: www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Integrated Management for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (IMEESC) toolkit. Geneva: World Health Organization; [Accessed 8.December.2013]. Available from: http://www.who.int/surgery/publications/imeesc/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 8. [Accessed 8.December.2013];Comprehensiva Trauma Life Support. Available from: http://ctlsindia.org/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.