Abstract

A growing body of evidence suggests that parenting influences the development of youth callous unemotional (CU) behavior. However, less is known about the effects of parenting or contextual risk factors on ‘limited prosocial emotions’ (LPE), a recent conceptualization of CU behavior added to the DSM-5. We focused on LPE at ages 10–12 and age 20 among low income, urban males (N = 310), and examined potential developmental precursors, including contextual risk factors assessed during infancy and observed maternal warmth during the toddler period. We found unique direct associations between maternal warmth, maternal aggression, and low empathetic awareness on LPE at ages 10–12, controlling for concurrent self-reported antisocial behavior. Further, there were indirect effects of maternal aggression, low empathetic awareness, and difficult infant temperament assessed in infancy on LPE at ages 10–12 via their influence on maternal warmth at age 2. Finally, there were lasting indirect effects of parental warmth on LPE at age 20, via LPE at ages 10–12. We discuss the implications of these findings for ecological models of antisocial behavior and LPE development, and preventative interventions that target the broader early parenting environment.

Keywords: callous-unemotional, parental warmth, limited prosocial emotions, contextual risk, antisocial behavior

In the last twenty years, there has been a significant research focus on callous unemotional (CU) traits among antisocial youth (Frick, Ray, Thornton, & Kahn, 2014). The CU construct comprises a set of behaviors (i.e., what we refer to as CU behavior), characterized by low empathy and guilt, callousness, and low emotionality. When compared to youth low on CU behavior, high CU designates more severe forms of aggression and a unique etiological pathway to antisocial behavior (AB), characterized by specific neurocognitive correlates and greater heritability (Blair, 2013). Although parenting has been established as a risk factor for CU behavior (Waller, Gardner, & Hyde, 2013), little is known about how other early environmental risk factors, particularly those that affect parenting, influence the development of CU behavior. Research examining early risk factors that affect parenting and that may also be linked to CU behavior, has implications for prevention and intervention efforts, including the potential to identify specific patterns of individual- and family-level risk factors. A CU behavior specifier for the diagnosis of Conduct Disorder was recently added to the DSM-5, termed ‘with limited prosocial emotions’ (LPE), which reflects the growing body of studies that have examined CU behavior (Frick et al., 2014). The primary goal of this study was to examine risk factors for the development of LPE in both early adolescence and emerging adulthood. We refer to CU behaviors as ‘LPE’ to be in line with the DSM-5 specifier, but conceptualize our measurement and the DSM-5 LPE category as representing the same underlying construct as CU traits. To provide a robust measurement of LPE with increased measurement of low empathy and prosociality, we include broader items tapping youth displays of prosociality, moral regulation, and empathetic concern.

An ecological model of parenting and AB

Models of AB have benefited from adopting an ecological perspective, whereby broader contextual risk factors are thought to affect later child behavior, especially via their effects on parenting (Belsky, 1984). Parenting practices are a well-recognized risk factor for the development of AB (Shaw & Shelleby, 2014) and are also related to the development of CU behavior (Waller et al., 2013). However, parenting does not occur in a vacuum and is subject to individual and contextual factors that may undermine the ability of parents to be effective, particularly with a more difficult child. Belsky (1984) proposed three domains of risk factors that he conceptualized as ‘determinants of parenting’. These domains comprise maternal psychological resources, social context, and child characteristics (Belsky, 1984), all of which may affect parenting and put children at greater risk for developing AB. In support of this theoretical premise, an extensive literature has linked risk factors that undermine parenting to subsequent youth AB, including greater parental stress and low social support (Shaw, Criss, Schonberg, & Beck, 2004), living in an impoverished neighborhood (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002), and having a child that is difficult to manage (e.g., Patterson, 1982). Indeed, in some but not all cases (Shaw, Gilliom, & Bell, 2000), these risk factors appear to predict youth AB via their effect on parenting. For example, in the current sample, youth AB at age 15 was predicted by maternal aggression via rejecting parenting assessed at ages 1.5 and 2 (Trentacosta & Shaw, 2008).

Parenting and CU behavior

Much of the recent empirical research has focused on the neurobiological basis of AB among youth high on CU behavior, demonstrating high heritability of AB in the context of CU behavior (e.g., Viding, Frick, & Plomin, 2007) and neural correlates in the functioning of the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (for recent reviews, see Blair, 2013; Hyde, Shaw, & Hariri, 2013). However, although studied in relation to youth AB more broadly, we know comparatively little about whether early environmental risk factors (e.g., parental characteristics or social context) are related to the development of CU behavior, particularly via their influence on parenting. The one risk factor in the environment that has been linked to CU behavior is parenting (Waller, et al., 2013). Specifically, prospective longitudinal studies have shown that harsh parenting predicts increases in CU behavior over time across different samples and developmental stages, including high risk preschoolers (Waller et al., 2012) and aggressive 9–12 year olds (Pardini, Lochman, & Powell, 2007). Fewer studies have examined positive parenting in relation to CU behavior. Parental warmth, a key component of positive parenting, is thought to facilitate children’s ability to internalize parental expectations. For example, reciprocal warmth within parent-child interactions is theorized to be rewarding, such that positive affect becomes reinforcing (MacDonald, 1992). Throughout the toddler years, a positive emotional foundation is hypothesized to enable children to develop empathic concern (Kochanska, 1997).

As such, a focus on parental warmth may improve our understanding of the development of CU behavior. In particular, examining parental warmth (or a lack thereof), may be important in understanding why some youth go on to develop AB in the presence of low empathic concern or prosociality (i.e., LPE/CU behavior). Among the few studies that have examined parental warmth during early and middle childhood, lower levels of warmth have been shown to predict increases in child CU behavior over time among both normative children (ages 3–10, Hawes, Dadds, Frost, & Hasking, 2011), aggressive children (ages 9–12, Pardini et al., 2007), and high-risk preschoolers (Waller et al., 2014). However, previous studies examining associations between parental warmth and CU behavior are limited by short follow-up periods ranging from 1–4 years. Thus, the current study examined the possible long-reach of parenting on LPE, that is whether maternal warmth, observed in the home at age 2, predicted LPE in early adolescence (ages 10–12) and emerging adulthood (age 20).

Relating early risk factors to the development of LPE

In addition, while parenting has been the focus of recent studies, there has been little consideration of the multiple pressures, stressors, and potential sources of support, which could influence parental caregiving quality and children’s LPE/CU behavior. A few studies have suggested that social context, including high levels of chaos in the home (Fontaine, McCrory, Boivin, Moffitt, & Viding, 2011) and low socioeconomic status (e.g., Barker, Oliver, Viding, Salekin, & Maughan, 2011) are related to CU behavior. Further, Loney and colleagues (2007) provided a preliminary cross-sectional test of the association between maternal and child ‘psychopathic traits’, which was almost fully mediated via dysfunctional parenting practices. Barker et al. (2011) also found that infant characteristics at age 2 were related to increases in harsh parenting at age 4, which in turn predicted increased CU behavior at age 13. However, beyond these studies, there has been little examination of contextual risk factors for CU behavior, especially factors that may be affect the one robust early environmental risk factor for CU behavior – parenting. Moreover, previous studies have not examined direct or indirect (via parenting) links between contextual risks in the family environment during infancy and the development of CU behavior within an ecological perspective.

Likewise, although previous studies linking parenting to CU behavior have examined preschool and school-age children, there has been less of a focus on measurement across multiple developmental stages. Two important transitions, key to the development of AB and the emergence of behaviors related to LPE, such as prosociality, are (a) the toddler years (i.e., 1.5–3 years old), during which time children peak in their expression of physical aggression, lack cognitive understanding to appreciate the consequences of their behavior, and may be particularly difficult for parents to manage (Shaw & Bell, 1993); and (b) the transition to adolescence (i.e., ages 10–12 years old), when children are faced with increasing independence and a variety of challenges, but immature regulatory systems (Arnett, 2004). Interestingly, toddlerhood also heralds the emergence and rapid maturation of behaviors related to the development of prosocial emotions, including conscience (Kochanska, 1997). These behaviors also appear to be influenced by early parenting (Kochanska, 1997; Waller et al., 2012), which makes studying this age period important in understanding parental and contextual effects on LPE. A final important developmental milestone also exists during early adulthood (age 20), when frequencies of AB peak (Arnett, 2004). Thus, it is important to follow the effect of early risk factors into emerging adulthood to determine the true severity and continuity of LPE across adolescence into adulthood.

Current study

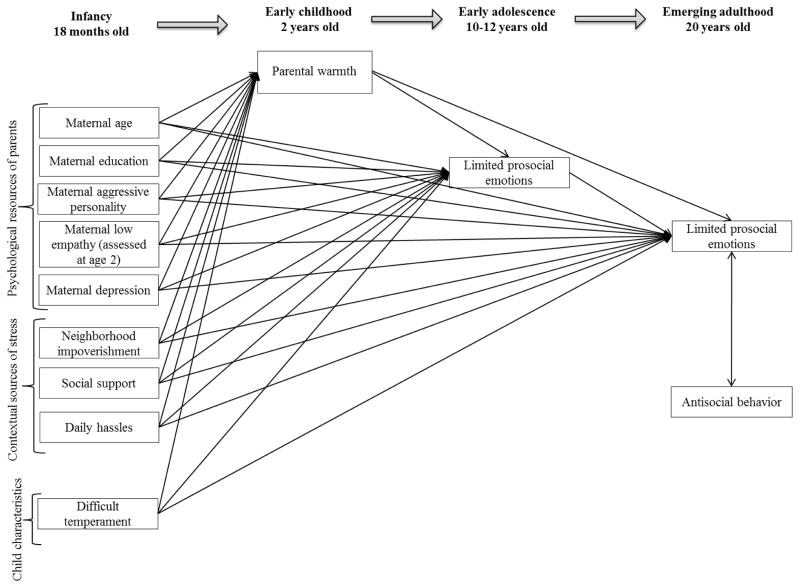

To address the need for a greater emphasis on developmental and contextually-influenced parenting models in understanding LPE, we examined whether risk factors, drawn from Belsky’s (1984) domains of ‘determinants of parenting’, and parental warmth were related to LPE in early adolescence and early adulthood (Figure 1). We focused on maternal psychological resources that have been linked to children’s AB, but that could also create an environment that would put children at risk of developing LPE, including parental personality and psychopathology (e.g., aggressive personality or uncaring beliefs). We also examined contextual risk factors that might disrupt parents’ ability to provide a warm environment, or that could be directly related to increases in child LPE, including neighborhood impoverishment, lack of social support, and daily childrearing stressors. Finally, based on a child effects model (Bell & Harper, 1977; Shaw & Bell, 1993) and the well-established link between difficult temperament and AB (DeLisi, & Vaughn, 2014), we examined the effect of difficult infant temperament on parenting and subsequent LPE. In particular, we were interested in examining whether a temperamentally difficult infant (e.g., irritable, fussy, hard to settle) might subsequently experience lower parental warmth, putting them at greater risk of LPE of AB later in life.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model showing hypothesized direct and indirect links between contextual risk factors, parental warmth, LPE in early adolescence and emerging adulthood, controlling for concurrent self-reported antisocial behavior (informed by Belsky, 1984).

Study questions were examined in a sample of at-risk low-income males who were assessed at 18 months of age and followed through adolescence. We focused on low-income males from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds because they appear are at elevated risk of developing AB (Loeber et al., 1998) and thus we could examine outcomes dimensionally, but in a sample enriched with higher rates of more serious behaviors. We examined study aims within a prospective longitudinal design across four time points: contextual risk factors at 18 months; parental warmth, derived from observational and interview methods at 2 years old; LPE and AB in early adolescence (10–12 years old); and again in emerging adulthood (20 years old). We hypothesized links between toddler-age contextual risk factors and LPE in both early adolescence and emerging adulthood, as well as mediated pathways via parental warmth at age 2 (Figure 1). By examining LPE at both ages 10–12 and age 20, we could examine stability in the construct across adolescence beyond links to AB. We examined the direct effects of contextual risk factors and parental warmth on LPE at ages 10–12 and age 20 separately. However, in a final model, we also sought to test the extent to which the effects of early contextual risk factors and parenting were mediated via LPE in early adolescence.

Methods

Participants

The participants in this study are part of the Pitt Mother and Child Project, an ongoing longitudinal study of child risk and resiliency in low-income families (Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003). In 1991 and 1992, 310 infant boys and their mothers were recruited from Women, Infants, and Children Nutrition Supplement Clinics in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, when boys were between 6–17 months old. At the time of recruitment, 53% of the sample were European American, 36% were African American, 5% were biracial, and 6% were of other races (e.g., Hispanic American). Race (0 = European American; 1 = non-European American) was included as a covariate in subsequent analyses. Two-thirds of mothers in the sample had 12 years of education or less. The mean per capita income was $241 per month, and mean Hollingshead socioeconomic status score was 24.5. Thus, many boys in this study were considered at elevated risk for antisocial outcomes because of their socioeconomic standing. Retention rates were generally high at follow-up assessments, with data available for 86% participants (n = 268) across ages 10, 11, or 12 and 83% (n = 257) at age 20. Boys retained at age 20 were compared with boys who were lost to follow-up. There were no significant differences in maternal age, education, maternal depression scores, or family income data collected at 18 months or on any measures used in the present study including parental warmth, with one exception: boys retained at age 20 were rated as having lower infant difficult temperament scores at 18 months (p < .05).

Visit Procedure

Target children and their mothers were seen for 2- to 3-hour visits almost every year from ages 1.5–20. Data were collected in the laboratory, on the phone, and/or at home. During home and lab assessments, parents and adolescents completed questionnaires regarding sociodemographic characteristics, family issues, and child behavior, as well as diagnostic interviews. Participants were reimbursed for their time at the end of each assessment. All assessments and measures were approved by the IRB of the University of Pittsburgh. The informed consent process conformed with the Declaration of Helsinki and University Institutional Review committee approval and oversight.

Measures

Maternal psychological resources

Maternal age and educational attainment

Maternal age at first birth and educational attainment (number years in school; e.g., 8 = grade school diploma, 12 = high school diploma) was measured during a demographic interview at the age 18-month assessment.

Maternal depressive symptoms (18 months)

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelon, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961), a well-established and widely used measure of depressive states was administered to mothers at child age 18 months. The BDI contains 21 items that are rated on a 0 to 3 scale and were summed. In the present sample, internal consistency of the BDI was high (α=.82; Shaw, Hyde, & Brennan, et al., 2012). Mean scores on the BDI were quite high (M = 8.98, SD = 6.59), indicating the presence of mild-moderate depressive symptoms, consistent with the stressors associated with child-rearing in a low income-context (Shaw & Shelleby, 2014).

Maternal aggressive personality (18 months)

An author-approved, abridged, three-factor version of the Personality Research Form (Jackson, 1989) was administered at 18 months. Because of its theoretical link to both increases in child CU behavior and/or lower parental warmth, we focused on the Aggression subscale, which comprises 16 statements, 8 of which indicate higher aggression (e.g., ‘I fly into a rage if things don’t go as I plan) and 8 of which are reverse scored (e.g., ‘I rarely get angry at other people’); items were rated as 0 = false, 1 = true. Aggression scores have been used previously in this sample with modest internal reliability (Trentacosta & Shaw, 2008; α =.63).

Empathetic awareness of the child’s needs (2 years)

The Adolescent Parenting Inventory (AAPI; Bavolek, Kline, McLaughlin, & Publicover, 1979) was administered at 2 years old. The AAPI is a 32-item measure, developed to assess maternal characteristics and beliefs. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and assess a range of attitudes and expectations. The empathetic awareness of the child’s needs factor contains eight items assessing empathetic attitudes relating to parenting practices, such as ‘sensitive parents spoil their children’ and ‘hugging children makes them grow up to be sissies’. The empathetic awareness scale has been used previously in this sample and exhibited good internal consistency (α =.81; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2008).

Contextual sources of stress

Neighborhood impoverishment (18 months)

Neighborhood impoverishment was assessed via geocoding of addresses when children were 18 months old using 1990 census data. Data were coded at the block group level. Based on Wikström and Loeber (2000), a neighborhood impoverishment factor was generated using: (1) median income, (2) percent families below the poverty level, (3) percent on public assistance, (4) percent unemployed, (5) percent single-mother households, (6) percent African-American, (7) percent Bachelor’s degree and higher. Across all census block groups in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania at 18 months, variables were standardized and summed to create an overall neighborhood impoverishment summary score of neighborhood impoverishment and exposure to community-level risk during this period of development factor score (Vanderbilt-Adriance & Shaw, 2008). Neighborhood impoverishment scores derived from geocoding census data were moderately related to mother reports at 18 months of family income (r =−.42, p <.001) and socioeconomic status (r =.29, p <.001), assessed using Hollingshead score (Hollingshead, 1975) and thus these other measures (e.g., income, SES) were not examined in the current study.

Social support (18 months)

The Marital Adjustment Test (Locke & Wallace, 1959) was administered to assess social support within the context of a significant romantic or co-parenting relationship (e.g., items adjusted for use with a partner, spouse, or co-caregiver and specific spousal items removed). The scale comprises 15 items relating to multiple issues within the family, including finances and conflict solving. Mothers rated the degree of support and agreement they perceived within their relationship for each item (e.g., ‘do you confide in this person [partner or co-caregiver]’ and ‘do you agree on values and attitudes towards life’). Scaling (i.e., 8-, 9- or 10-point Likert Scale) was item-dependent, so items were z-scored before summing. This measure has been used before in this sample at 18 months with high internal consistency (α =.77; Shaw, Criss, Schonberg, & Beck, 2004).

Daily parenting hassles (18 months)

Mothers completed the frequency subscale of the Parenting Daily Hassles questionnaire (PDH; Crnic & Greenberg, 1990). The PDH assesses typical stressors facing parents and is associated with child behavior outcomes to a greater degree than global life stresses (Crnic & Greenberg 1990). For the current study, mothers rated each of the 20 items on a scale of 1 (rarely) to 4 (constantly), and how much of a ‘hassle’ it represents on a scale of 1 (no hassle) to 5 (big hassle). The current study used the frequency of hassles factor (e.g., frequency that mothers felt they were ‘always cleaning up messes of toys or food’ or ‘having to change plans because of unexpected child needs’). Scores for each item were summed as in previous studies within this sample and demonstrated good reliability (α =.78; Beck & Shaw, 2005).

Infant characteristics

Difficult temperament (18 months)

Difficult temperament was assessed using the Difficultness factor of the Infant Characteristics Questionnaire (ICQ; Bates, Freeland, & Lounsbury, 1979). The ICQ is a seven-item maternal-reported measure of temperament that has demonstrated reliability, validity, and robust prediction of later behavior problems in samples of young children (Bates, Maslin, & Frankel, 1985). Mothers rated each item on a 7-point Likert Scale (e.g., ‘how much the infant fusses’, ‘how easily the infant gets upset’, and ‘how often the infant’s mood changes’). In the present sample, the scale demonstrated good internal reliability (α =.80; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2008).

Parenting

Parental warmth (age 2)

Parental warmth at age 2 was derived using the Responsivity and Acceptance subscales from the widely-used and validated Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME; Caldwell & Bradley, 1978). The HOME assesses the quality and quantity of support and stimulation in the home environment using both observations and parent interview. For the 11-item Responsivity Scale (α =.71), examiners rated mothers’ emotional responsivity to the child with items (e.g., ‘parent responds verbally to child’s verbalizations’ and ‘parent spontaneously praises child at least twice’). For the 8-item Acceptance Scale (α = .67), examiners rated mothers’ acceptance of the child’s behavior (e.g., ‘parent does not shout at child’ and ‘parent does not express overt annoyance with the child’). Mean scores on each subscale were z-scored and added together to create an observed warmth score as previously described in this sample (Sitnick, Shaw, & Hyde, 2014).

Youth Limited Prosocial Emotions (ages 10–12 and age 20)

We assessed LPE using two different measures that were combined in a latent construct. First, we used four items of the CU scale of the Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD; Frick & Hare, 2001; e.g., ‘concern about the feelings of others’, ‘feel(s) guilty after wrongdoing’) assessed via parent-reported at ages 10 and 11 and via youth self-report at age 20. Items of the APSD are rated on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = sometimes true, 2 = definitely true). Second, we used 10 items of the Prosociality/Empathy scale of the Child and Adolescent Dispositions Scale (CADS; Lahey, Rathouz, Applegate, Tackett & Waldman, 2010) via parent report at age 12 and youth self-report at age 20 (e.g., ‘help(s) others when they get hurt’, and ‘share(s) things with others’). Items are rated on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all; 4 = very much/very often). The 10 items were chosen, (1) if they had been assessed at both the age 12 and age 20 assessment points (the assessment framework changed over this period), (2) based on loadings within separate exploratory principal components analysis conducted at both ages, and (3) based on exploratory factor analytic results reported in previous studies in both this (Trentacosta, Hyde, Shaw, & Cheong, 2009) and other samples (e.g., Waldman, et al., 2011).

We combined the two scales at ages 10–12 and age 20 at the item level to address concerns surrounding the well-documented marginal internal consistency of the APSD CU scale (Kotler & MacMahon, 2010). Indeed, while we found acceptable internal consistency at age 10 (α =.70), it was lower at both ages 11 (α =.64) and 20 (α =.61). By combining these two scales, we provided more robust measurement of LPE, which represents a similar approach to previous studies that have combined different scales to improve measurement of the CU behavior construct (e.g., Viding et al., 2007). We found moderate inter-scale correlations at ages 10–12 (range, r = .30–.33, p < .001) and a strong inter-scale correlation at age 20 (r = .73, p < .001). At both ages 10–12 and age 20, we created a latent construct of LPE specifying items from across both measures to load onto a LPE factor using Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) with Weighted Least Squares Means Variance (WLSMV; appropriate for use with ordinal items) estimation in Mplus version 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). At age 20, a one-factor solution fit the data better than a correlated two-factor model (results available upon request). For LPE at ages 10–12, the best-fitting model involved us modeling age-specific variance to reflect the fact that scales were collected at three different time points (i.e., age was modeled as a ‘specific’ factor and LPE as a ‘general’ factor within a bifactor framework). This model fit the data better than a correlated three-factor model (results available on request). Model fit was good at both time points (ages 10–12, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .05; age 20, CFI = .93, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .099) and the LPE measures exhibited high internal consistency at ages 10–12 (α = .82) and age 20 (α = .83).

Control variables

Self-reported AB (ages 10–12; age 20)

To confirm that any findings were specific to LPE and not just to broader AB, we assessed youth AB using the Self-report of the Delinquency Questionnaire (SRD; Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985), which assesses the frequency that an individual has engaged in aggressive and delinquent behavior, alcohol and drug use, and related offenses in the last year. Boys’ rated their engagement in different types of antisocial activities (e.g., stealing, drug use) via a 3-point scale (1 =never, 2 =once/twice, 3 =more often). At ages 10–12, the measure comprised 33 items, whereas at age 20, there were 53 items (Elliot et al., 1985) to reflect the greater range of antisocial acts likely engaged in during this period of emerging adulthood when AB is at its peak (Arnett, 2004). Internal consistencies were high (ages 10–12; α =.79 .92; age 20, α = .90; Shaw et al., 2012).

Analytic plan

First, descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations were explored (Table 1). Second, a series of multiple regression models were computed to examine our first two study aims and test whether contextual risk factors and observed parental warmth uniquely predicted LPE factor scores at ages 10–12 or 20, controlling for concurrent self-reported AB. Third, we specified a path model to examine indirect effects between contextual risk factors, observed parental warmth, and LPE. Models were examined with Mplus 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Zero-order and multiple regression analyses examining associations between contextual risk factors, parenting, and LPE at ages 10–12 and age 20 were examined within a latent factor framework using WLSMV. These analyses included all boys for whom had collected data at ages 10, 11, or 12 (n = 268; Shaw et al., 2012) and age 20 (n = 257). For our final path models, and to be able to estimate bootstrapped confidence intervals, we used extracted factor scores for LPE scores to estimate direct and indirect pathways within a maximum likelihood framework. Using maximum likelihood procedures, our final model included the full sample (N = 310). Model fit was considered adequate if the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) values met established guidelines for good fit (i.e., RMSEA < .06 and CFI > .95) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). All direct paths were examined for statistical significance. Indirect pathways were tested for statistical significance using bootstrapping methods to estimate confidence intervals based on unbiased standard errors.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations between study variables

| Age | Educ | Dep | Agg Pers | Low Emp | Neigh. Impov | Social Supp | Daily Hassle | Diff Temp | Warmth | LPE (10–12) | LPE (20) | AB (10–12) | AB (20) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contextual risk | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Maternal age (P) | ||||||||||||||

| Education (P) | .28*** | |||||||||||||

| Depression (P) | −.05 | −.08 | ||||||||||||

| Agg Personality (P) | −.19** | −.12* | .32*** | |||||||||||

| Low empathy (P) | −.16** | −.42*** | .08 | .20** | ||||||||||

| Neigh. impov. (P) | −.15* | −.11† | .16** | .25*** | .26*** | |||||||||

| Social support (P) | −.08 | −.01 | −.37*** | −.16** | −.03 | −.06 | ||||||||

| Daily hassles (P) | −.02 | −.001 | .38*** | .17** | −.02 | .09 | −.34*** | |||||||

| Diff. temp (P) | −.07 | .002 | .09 | .18** | −.02 | .01 | −.03 | .24*** | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Parenting | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Parental warmth (O) | .24*** | .19** | −.10 | −.25*** | −.35*** | −.24*** | .01 | −.05 | −.18** | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Youth outcomes | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| LPE (10–12) (P) | −.27*** | −.23** | −.03 | .28** | .35*** | .25** | −.04 | −.003 | −.04 | −.37*** | ||||

| LPE (20) (Y) | −.10† | −.13* | −.07 | .05 | .10 | .19** | .21** | −.01 | −.02 | −.13† | .31*** | |||

| AB (10–12) (Y) | −.22*** | −.05 | .23** | .25** | .08 | .21*** | −.01 | .09 | .15* | −.19** | .39*** | .17** | ||

| AB (20) (Y) | −.04 | .09 | .02 | −.004 | −.002 | −.01 | −.003 | .17** | .08 | .12 | .08 | .25*** | .26* | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| M | 27.87 | 12.63 | 8.87 | .6.91 | 16.92 | .38 | 100.00 | 42.92 | 23.43 | .02 | .00 | .00 | 3.53 | 1.22 |

| SD | 5.40 | 1.50 | 6.75 | 2.89 | 4.78 | 1.09 | 30.51 | 8.21 | 6.42 | .78 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.37 | .17 |

Note.

p < .10,

p <.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Age of assessment (in years) and informant/method of assessment (P = parent; Y = youth; O = observed) shown in parentheses. Agg. Pers. = maternal aggressive personality; Low emp = low empathetic awareness; Neigh. impov. = neighborhood impoverishment; Diff temp = difficult temperament; Limited prosocial emotions = LPE; AB = antisocial behavior

Results

Descriptive and zero-order associations between independent and dependent variables

As shown in Table 1, despite the long follow-up period and cross-informant reports, LPE at ages 10–12 and 20 were moderately correlated (r = .31, p < .001), and both were associated with concurrent self-reported AB (r = .39, p < .001 at ages 10–12; r = .25, p < .001 at age 20). In relation to our first study aim examining contextual correlates of later LPE, being a younger mother, having lower maternal educational attainment, higher maternal aggressive personality, lower maternal empathetic awareness, and higher neighborhood impoverishment were related to having higher LPE at ages 10–12. In addition, being a younger mother, lower maternal education, and higher neighborhood impoverishment were also linked to higher LPE at age 20. In contrast to our hypotheses, higher social support at 18 months was related to higher LPE at age 20.

In relation to our second aim examining parenting as a predictor of LPE, higher levels of observed parental warmth at age 2 were related to lower LPE at ages 10–12, and there was trend level association with LPE at age 20. Finally, in relation to our third study aim to examine indirect effects, we found significant, zero-order correlations between some of the contextual risk factors and parental warmth. Specifically, lower maternal age, lower education, higher aggressive personality, lower empathetic awareness, higher levels of neighborhood impoverishment, and greater child difficult temperament were associated with lower levels of parental warmth. In contrast, there were no zero-order associations between maternal depression, social support, and parenting daily hassles at 18 months and subsequent parental warmth.

Do contextual risk factors predict LPE?

We examined unique associations between contextual risk factors at 18 months and LPE, controlling for race and concurrent self-reported AB (Table 2; Models 1 & 2). First, lower maternal depression, higher maternal aggressive personality, lower maternal empathetic awareness, and low social support each uniquely predicted LPE at ages 10–12 after accounting for the overlap between all contextual factors. Second, lower maternal education attainment at 18 months uniquely predicted LPE at age 20 in similar multivariate models but other maternal psychological resources, contextual stressors, and child characteristics did not show unique associations. In contrast with our hypotheses, higher social support at 18 months continued to predict higher LPE at age 20 in multivariate models.

Table 2.

Parenting factors predicting limited prosocial emotions (LPE) in early adolescence and early adulthood, controlling for race and concurrent antisocial behavior

| Study Aim 1 Contextual risk factors as predictors |

Study Aim 2 Contextual risk factors and parental warmth as predictors |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Model 1 LPE (P) ages 10–12 |

Model 2 LPE (Y) age 20 |

Model 3 LPE (P) ages 10–12 |

Model 4 LPE (Y) age 20 |

|||||

|

| ||||||||

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | |

| Additional covariate | ||||||||

| Child race (P) | .08 (.28) | .03 | −.30 (.15) | −.13* | .38 (.30) | .15 | −.30 (.15) | −.13* |

|

| ||||||||

| Maternal psychological resources | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Maternal age (P) | −.02 (.02) | −.11 | −.001 (.01) | −.01 | −.02 (.02) | −.09 | .001 (.01) | .01 |

| Educational attainment (P) | −.06 (.07) | −.08 | −.10 (.05) | −.14† | −.06 (.07) | −.08 | −.10 (.06) | −.14† |

| Maternal depressive symptoms (P) | −.04 (.02) | −.24** | −.01 (.01) | −.05 | −.04 (.02) | −.23* | .01 (.01) | −.05 |

| Maternal aggressive personality (P) | .07 (.03) | .17* | .01 (.03) | .03 | .07 (.04) | .17* | .01 (.03) | .03 |

| Low maternal empathetic awareness (P) | .05 (.02) | .22* | −.003 (.02) | −.01 | .03 (.02) | .14* | −.01 (.02) | −.04 |

|

| ||||||||

| Contextual sources of stress | ||||||||

| Neighborhood impoverishment (O) | .10 (.12) | .10 | .13 (.09) | .10 | .20 (.13) | .19 | .14 (.09) | .11 |

| Social support (P) | −.01 (.004) | −.22* | .01 (.003) | .21** | −.01 (.004) | −.23* | .01 (.003) | .21** |

| Parenting daily hassles (P) | −.01 (.01) | −.05 | .004 (.01) | .03 | −.01 (.01) | −.07 | .004 (.01) | .03 |

|

| ||||||||

| Child characteristics | ||||||||

| Child difficult temperament (P) | −.01 | .07 | −.008 (.01) | −.05 | −.02 (.02) | −.08 | −.01 (.01) | −.06 |

| Concurrent antisocial behavior (Y) | .10 (.04) | .27** | .03 (.01) | .27*** | .09 (.04) | .24** | .04 (.01) | .27*** |

|

| ||||||||

| Parenting | ||||||||

| Parental warmth (O) | −.08 (.04) | −.20* | −.03 (.03) | −.08 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| R2 | .29*** | .17*** | .33*** | .18*** | ||||

Note:

p < .10,

p <.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

P=parent-reported; Y=youth self-reported; O=observed. Model 1 examines prediction of LPE at ages 10–12 and includes race, concurrent self-reported antisocial behavior (ages 10–12) and contextual risk factors. Model 2 examines prediction of LPE at 20 and includes race, concurrent self-reported antisocial behavior (age 20) and contextual risk factors. Model 3 examines prediction of LPE at ages 10–12 and extends Model 1 by including observed parental warmth at age 2. Likewise, Model 4 examines LPE at age 20 and extends Model 2 by including observed parental warmth at age 2.

Does early parental warmth predict LPE?

We next examined unique associations between parental warmth and LPE, controlling for child race, concurrent self-reported AB, and contextual risk factors (Table 2; Models 3& 4). Lower levels of parental warmth were significantly related to LPE at ages 10–12 (Model 3), but not LPE at age 20 (Model 4), when controlling for covariates and self-reported AB. Lower levels of maternal depression, higher maternal aggressive personality, lower maternal empathetic awareness, and lower social support continued to predict LPE at ages 10–12, controlling for age 2 parenting. Interestingly, maternal depression showed the opposite effect to that reported in a previous study (Barker et al., 2011). Specifically, lower maternal depression was associated with higher levels of LPE at ages 10–12. Lower levels of maternal educational attainment and higher social support continued to be related to LPE at age 20 when we accounted for observed parental warmth.

Does parental warmth mediate links between contextual risk and outcomes?

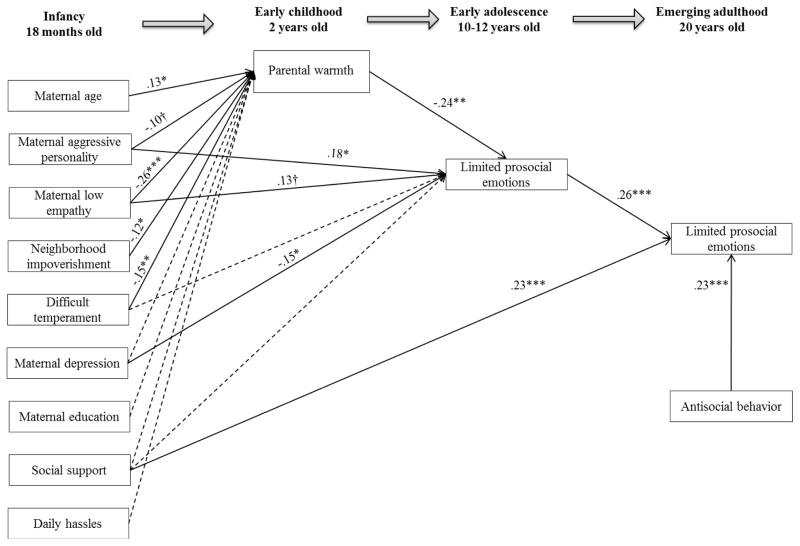

To examine our third hypothesis, we tested indirect effects between contextual risk factors and LPE at ages 10–12 and 20 via parental warmth. We specified direct links between parental warmth, contextual risk factors, and LPE at ages 10–12 and 20 and tested indirect links between contextual risk factors and LPE via parental warmth. We also tested indirect links between contextual risk factors, warmth, and LPE at age 20, via LPE at ages 10–12 (see Figure 1). Our first model included direct pathways from all contextual risk factors and observed parental warmth to LPE at 10–12 and 20, as well as all possible indirect effects (as per Figure 1). This model had acceptable fit (χ2 (df = 2) = 3.27, p = .19; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .05) but, unsurprisingly based on the earlier regression analyses (Table 2), the model featured a number of non-significant paths. To obtain the most parsimonious solution, we trimmed the model removing non-significant direct pathways based on model estimates and the earlier multiple regression models (i.e., p > .10). The final model (Figure 2) fit the data significantly better than the original model (Δχ2(df = 12) = 21.05, p < .05) and showed overall acceptable model fit (χ2(df = 14) = 24.32, p = .04; CFI = .92; RMSEA = .04). The model featured significant direct paths from parental warmth, maternal depression, maternal aggressive personality, and low maternal empathetic awareness to LPE at ages 10–12. There was also a direct effect of LPE at ages 10–12 (parent-reported) on LPE at age 20 (youth-reported), controlling for concurrent self-reported AB at 20 and contextual risk factors and parental warmth. As per the multiple regression analyses, we continued to find a direct effect of higher social support at 18 months on LPE at age 20. Two mediated pathways emerged between contextual risk factors and LPE at ages 10–12 via maternal warmth at age 2, for low maternal empathetic awareness (αβ = .06, SE = .03, p < .05) and infant difficult temperament (αβ = .04, SE = .02, p = .05). In addition, lower observed parental warmth (αβ = .06, SE = .03, p < .05) and higher maternal aggressive personality (αβ = .05, SE = .02, p < .05) were indirectly related to LPE at age 20 via their influence on LPE at ages 10–12. Finally, low maternal empathetic awareness showed a trend level indirect association with LPE at age 20 via both observed warmth and LPE at ages 10–12 (αβ = .02, SE = .01, p < .10).

Figure 2. Direct and indirect effects between contextual risk factors, parental warmth, and LPE (ages 10–12 and age 20).

Note: † p < .10, *p <.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001. CI = confidence intervals. For indirect effects, we provide an estimate of the product of the coefficients (αβ), (i.e., the ‘sobel test’) as an index of gross effect size. However, we also present the bootstrapped CI of this effect (p < .10), as bootstrapped results have been shown to be more powerful and accurate and less dependent on the likely non-normal distribution of the product term. Thus, we focus on bootstrapped CI in the Results, but present effect sizes for comparability and ease of interpretation: (a) low empathetic awareness → parental warmth → LPE ages 10–12 (αβ=.06, p=.02; bootstrapped CI =.02, .10); (b) infant difficult temperament → parental warmth → LPE ages 10–12 (β = .04, p = .04; bootstrapped CI =.01, .07); (c) parental warmth → LPE ages 10–12 → LPE age 20 (αβ=.06, p=.02; bootstrapped CI =.02, .10); (d) maternal aggressive personality → LPE ages 10–12 → LPE age 20 (αβ=.05, p=.04; bootstrapped CI =.02, .09); (e) higher maternal depression → LPE ages 10–12 → LPE age 20 (αβ=.04, p=.06; bootstrapped CI =.01, .07); (f) low empathetic awareness → parental warmth → LPE ages 10–12 → LPE age 20 (αβ=.02, p=.05; bootstrapped CI =.002, .03). All pathways shown were modeled in the final model. Solid lines are those pathways that were significant in the final model; dashed lines represent pathways that were modeled in the final model but were not significant.

Discussion

The current study examined the role of parental warmth and contextual risk factors in the development of LPE. We adopted a multi-method, multi-informant approach, and employed measurement of predictors and youth outcomes at key developmental transitions in toddlerhood, early adolescence, and emerging adulthood. Our results highlight the influence of early risk factors on increased risk for LPE in early adolescence, including direct effects of higher maternal aggression, and lower empathetic awareness. Low parental warmth also predicted LPE at ages 10–12 and the effects of lower empathetic awareness, and higher infant difficult temperament on LPE appeared to operate via their influence on parental warmth. There was moderate stability in LPE from ages 10–12 to age 20, which is striking given the follow-up period and the different reporters at each time point (parent vs. youth). Finally, although there were few direct effects of early risk factors and parental warmth on LPE at age 20, there were indirect effects of low warmth, high maternal aggressive personality, higher depression, and lower maternal empathetic awareness via their influence on LPE at ages 10–12.

Contextual risk factors

Our first hypothesis was that contextual family risk factors would be related to LPE at ages 10–12 and age 20. In relation to this hypothesis, we found that higher levels of maternal aggressive personality and low social support at child age 18 months, and low empathetic awareness at 24 months were related to more LPE at ages 10–12. It is noteworthy that associations emerged over and above overlap with other maternal psychological resources (age and education) and contextual sources of stress (social support and daily parenting hassles). Further, maternal aggressive personality at 18 months was related to LPE at age 20 via its influence on LPE at ages 10–12. It is striking that this indirect association emerged, not just because of the 18 year follow-up period, but also because these measures were assessed across informant (maternal report of their aggressive personality traits vs. youth-reported LPE at 20, controlling for youth-reported AB). The finding that maternal aggressive personality at 18 months was directly related to LPE at ages 10–12 and indirectly related to LPE at 20 could indicate that more aggressive parents provide an environment that does not nurture the development of empathy or prosociality. However the finding could also reflect shared and passive genetic vulnerability, resulting in direct associations between personality features in children and their parents consistent with other recent reports (Dadds et al., 2014; Loney et al., 2007; also see Hyde, Waller, & Burt, 2014). The possibility of gene-environment correlation appears to be more likely because parenting did not mediate these associations. Thus, parental aggressive personality appears important in the development of LPE possibly via heritable or non-parenting contextual effects.

Indeed, it was striking that we found robust and direct effects of several early family contextual risk factors, such as low maternal empathetic awareness and aggressive personality, on LPE at ages 10–12, which did not appear to operate via parenting and thus may be ‘stand-alone’ risk factors. Indeed, while we focused on contextual risk factors that we hypothesized would influence parenting practices, our findings highlight the need for future studies to examine risk factors beyond parenting in relation to a developmental model of LPE, especially as there has been little attention to these factors in the broader literature exploring CU behavior development. In particular, our findings fit with a recent conceptualization of the family stress model, positing both direct and indirect (via parenting) effects of parental resources on risk for child behavior problems in the context of low income families (Shaw & Shelleby, 2014), and extends it to development of CU behaviors.

We also found that higher maternal depression at 18 months was related to lower LPE at 10–12, which contrasts with the findings of a previous study that found that prenatal cumulative risk, including maternal psychopathology, was associated with higher CU behavior at age 13 (Barker et al., 2011). Further, there is a well-documented association between maternal depression and risk for children developing emotional and behavioral problems (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999), including within the current sample (Gross, Shaw, & Moilanen, 2008). In particular, depressive symptoms are thought, among various pathways, to compromise mothers’ ability to provide adequate caregiving or nurturance (Shaw & Shelleby, 2014). However, it has also been hypothesized that associations between maternal depression and child externalizing outcomes are related to concurrent aggressive traits in mothers (Kim-Cohen, Moffitt, Taylor, Pawlby, & Caspi, 2005). In support of this premise, we found that maternal depression was not related to LPE at ages 10–12 in zero-order analysis, but only in regression models controlling for overlap with other risk factors (including maternal aggressive personality and neighborhood impoverishment). Thus, it may be that once these factors are partialled, a suppression effect emerges in which variance left in low maternal depression acts as a marker for heritable factors such as low fear, low anxiety, or lower internalizing, which could put children at risk for higher LPE. This explanation would be consistent with theories of CU behavior and adult psychopathy as having a core aspect of low anxiety and depression (e.g., Blair, 2013). However, this finding and explanation needs much more examination in future studies and was certainly in the opposite direction to that predicted. Also somewhat surprisingly, we found that maternal reports of low social support at 18 months predicted higher parent-reported LPE at ages 10–12 but lower youth-reported LPE at age 20. The direct effect of social support on LPE at 20 emerged in zero-order associations, regression models controlling for overlap with other sources of contextual risk and parenting, and in our final path model. The opposite pattern of findings for ages 10–12 and age 20 may be due, at least in part, to the different informants (i.e., parent-reported LPE at ages 10–12 and youth-reported LPE at age 20). Beyond differences in informant, it is difficult to offer other simple post-hoc explanations that explain the robustness of this association in an unexpected direction across both zero-order and multivariate models. However, this finding again highlights the need for more research into contextual correlates of LPE.

The influence of parental warmth

Our second hypothesis was that observed parental warmth at age 2 would be related to LPE at ages 10–12 and age 20. We found a direct effect of parental warmth on LPE at ages 10–12, which fits with previous studies that have demonstrated prospective links between lack of positive parenting and increases in youth CU behavior over time (e.g., Waller et al, 2014). We also hypothesized indirect effects of contextual risk factors on LPE outcomes via parental warmth. First, for LPE at ages 10–12, our results suggest that lower maternal empathetic awareness of her child’s needs indirectly influenced child outcomes by shaping less warm caregiving practices. However, it is noteworthy that parental empathetic awareness was measured at the same time point as parental warmth, which must be considered as a limitation in interpreting this finding. Nevertheless, previous studies have suggested that parenting attitudes and beliefs about parenting do appear relatively stable in the preschool period (e.g., Waller, Gardner, Dishion, Shaw, & Wilson, 2012). Second, we found evidence for indirect effects of difficult infant temperament on LPE. Specifically, it appears that more difficult infants evoke less warmth from their mothers, which may in turn contribute to the development of LPE. Future studies are needed to examine a possible cascade effects between these two domains and whether there are temperamental factors in the early toddler period that may be unique to the development of LPE (e.g., fearlessness; Barker et al., 2011; Blair, 2013), or whether negative feelings and lower parental warmth are evoked by a more universal parental perception or experience of infant difficultness. Finally, although there was no direct effect of parental warmth on LPE at age 20, we found a significant indirect effect via LPE at ages 10–12, indicating that very early parenting may only be important for LPE in emerging adulthood to the extent that it ‘sets the stage’ by contributing to earlier LPE. Further, the effect of low maternal empathetic concern on LPE at age 20 was mediated via parental warmth at age 2 and LPE at ages 10–12. This finding indicates that low maternal empathetic awareness of her child’s needs has lasting indirect effects on youth outcomes via effects on warm caregiving practices and subsequent LPE in early adolescence. These long-lasting but indirect pathways are consistent with other recent studies within this sample emphasizing the importance of early risk and cascading effects on later externalizing outcomes (e.g., Sitnick, et al., 2014).

Implications for development of LPE and/or models of AB

Taken together, these findings highlight ages 10–12 as an important transition when it may be possible to identify youth at risk of developing more severe and entrenched AB or LPE into adulthood. That being said, as our major focus was on risk in the toddler period, we did not examine environmental risk factors during the adolescent transition, so cannot speak to the contribution of youth characteristics versus the influence of contextual or environmental risk factors, including increasing engagement of adolescents with peers outside the home. Indeed, a previous study in this sample suggested that the effect of adolescent dispositions (i.e., daring, prosociality) on later AB was qualified by contextual factors (i.e., parental knowledge, neighborhood danger; Trentacosta et al., 2009). The current study also highlights the toddler years as an important period during which to intervene with vulnerable families, as experiences in this early period were linked to LPE in early adolescence, which in turn was related to LPE in emerging adulthood. In particular, mothers living in impoverished neighborhoods, who themselves demonstrate high levels of aggression and low empathetic awareness, appear to be at risk of displaying lower levels of warmth during the toddler years, which may place their child at risk for LPE, all above and beyond risk posed for AB.

Our findings add to a growing literature highlighting the importance of considering salient environmental influences on the broader development of CU behavior (see Lahey, 2014; Waller et al., 2013), and emphasize the need for more research on contextual factors beyond parenting in the development of CU behavior. In particular, our findings highlight the specificity of effects of parental warmth and other sources of contextual risk on CU behavior, as we stringently controlled for concurrent AB. The current study highlights a combination of risk factors, which begin to influence children early in life, and appear to have cascading effects on emerging features of psychopathy (i.e., callousness, low prosociality, and propensity for aggression) across childhood and adolescence (also see Sitnick et al., 2014). However, our findings should also be considered alongside a large body of literature that has examined neurobiological underpinnings of AB and the development of CU behavior (see Blair, 2013). In particular, high LPE/CU behaviors appear to be related to lower responsivity to emotional cues of distress or fear in others, which has been linked to hyporeactivity of the amygdala. Indeed, an ability to recognize or be responsive to emotions of distress/fear in others provides a very plausible neurobiological mechanism for the development of LPE. Future studies are needed that examine associations between putative environmental risk factors (e.g., low parental warmth) and neural structure and function (e.g., amygdala reactivity), and how and when these interact to produce an outcome of AB and LPE. Finally, it should be noted that LPE/CU behavior was added to the DSM-5 to be a specifier for the diagnosis of Conduct Disorder. Indeed, the use of the CU behavior construct in DSM-5 implies a person-centered approach in the diagnosis of AB. On one hand, it is important to recognize that the current sample, while high-risk, did not exhibit uniformly high rates of AB or Conduct Disorder that might typically be found in a clinic-referred or forensic sample, and among whom the DSM-5 specifier has obvious practical utility. On the other hand, recent research has highlighted the dimensional nature of psychopathology (e.g., Krueger & Markon, 2011), which may better capture the distribution of both normative and psychopathological aspects of LPE (i.e., normative individual differences in empathic concern and prosociality). Indeed, while not drawn from a forensic or clinic population, 38% of our sample had a juvenile petition against them, many of which involved violent offenses, highlighting that continued examination of risk factors for dimensions of LPE and across a range of different samples types is warranted.

Strengths and limitations of the current study

There were a number of strengths to the study, including its prospective longitudinal design, relatively large sample of at-risk mothers and their sons followed with high retention over 20 years, the use of multiple informants and assessment methods, and control for overlap between LPE and AB. Nevertheless, several limitations should be noted. First, we included only boys from low-income families living in an urban setting. These findings may not generalize to girls and higher socioeconomic or nonurban settings. Second, although we employed a robust measurement approach of LPE, we don’t know whether our measure relates to CU behavior assessed via ‘standard’ measures (e.g., Inventory of Callous Unemotional Traits; Frick, 2004), though we did include parent reports from a widely-used measure of CU behavior (APSD) into the LPE measure. Further, there was a moderate association between parent reports of LPE at 10–12 years and youth reports LPE at age 20, supporting the construct validity of the measure. However, at both age points it is also important to recognize that measures derived from single-informant ratings of behaviors do not equate to ‘CU traits’ or indeed to what can be considered as stable or ‘trait’-like personality features. That is, the measure does not equal the underlying construct, particularly when dependent on only one informant or method of assessment. Future studies are needed that employ multiple assessment methods to assess LPE (e.g., incorporating multiple informant data from across settings or observations of behavior). Third, recent studies have shown father’s personality traits to be related to boys’ CU behavior, which were not measured here (Dadds et al., 2014). Further, while the links between youth LPE and maternal aggressive personality and low empathy suggest the importance of considering particular parenting environments, our findings could equally reflect shared genetic vulnerability, which unfortunately, we weren’t able to address in this sample. Fourth, whereas our primary study goal was to examine the influence of early parental warmth on LPE in adolescence and emerging adulthood, we did not have measures available between ages 3–6 that assessed constructs relevant to LPE. In particular, ages 3–6 represent a salient developmental period in relation to the development of prosociality and empathic concern (Waller, Hyde, Grabell, Alves, & Olson, in press). Future studies are needed that examine whether parental warmth in the toddler years affects the development of LPE in early adolescence via its influence on these behaviors in middle-childhood. Finally, many of the indirect effects we reported were modest in magnitude, which might be expected over such a long follow-up and when controlling for the overlap of many related variables, but replication is needed. Finally, as we did not have reliability data on observations of parental warmth, replication in a separate sample is important.

Conclusions and future directions

Our findings suggest that early parental warmth has lasting effects on LPE, adding to growing evidence highlighting the importance of parenting to the development of CU behavior (Waller et al., 2013). Our results also suggest that parenting programs may benefit from targeting mothers who appear prone to aggression and hostility and who express low empathetic awareness for the needs of their child, as well as families living in low socioeconomic contexts. While these mothers often, but not always, represent those most difficult to engage in intervention programs (Dishion et al., 2008), successful efforts to enhance their ability to be warm early on may help to reduce risk of children developing CU behavior and/or more severe forms of AB. In addition to addressing parenting skills and caregiving, preventive interventions during the toddler years could also seek to help parents from low income neighborhoods cope with emotional, financial, and social challenges as these non-parenting contextual variables appear critical in addressing parenting and child development (Dishion et al., 2008; Shaw & Shelleby, 2014). Few studies have investigated the effect of such community-based interventions on CU behavior. However, evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that interventions targeting maternal harshness are effective in reducing child CU behavior (e.g., Somech & Elizur, 2012). Future research is needed to examine whether prevention efforts to reduce CU behavior that directly target contextual risk factors and parenting are more beneficial than those which target parenting only among at-risk groups. Finally, the novelty of this study in examining contextual risk factors and maternal warmth in the development of LPE over 18 years highlights the need for continued attention to longer follow-up periods and an examination of risk factors beyond parenting in the development of LPE.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants DA25630 and DA26222 awarded to D.S. Shaw and E.E. Forbes. We thank the staff of the Pitt Mother and Child Project and the study families for making the research possible. We also thank three anonymous reviewers and the editor for extremely valuable suggestions and comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AB

antisocial behavior

- CU

callous unemotional

- LPE

limited prosocial emotions

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Waller, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan.

Daniel S. Shaw, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh

Erika E. Forbes, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Luke W. Hyde, Department of Psychology, Center for Human Growth and Development, Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan

References

- Arnett JJ. Adolescence and emerging adulthood. Pearson Prentice Hall; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barker E, Oliver B, Viding E, Salekin R, Maughan B. The impact of prenatal maternal risk, fearless temperament, and early parenting on adolescent callous-unemotional traits: A 14-year longitudinal investigation. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2011;52:878–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Freeland CA, Lounsbury ML. Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Development. 1979;50:794–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Maslin CA, Frankel KA. Attachment security, mother-child interaction, and temperament as predictors of behavior-problem ratings at age three years. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50:167–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavolek S, Kline D, McLaughlin J, Publicover P. Primary prevention of child abuse and neglect: Identification of high-risk adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1979;3:1071–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4(6):561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck J, Shaw DS. The influence of perinatal complications and environmental adversity on boys’ antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ, Harper LV. Child effects on adults. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ. The neurobiology of psychopathic traits in youths. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14:786–799. doi: 10.1038/nrn3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Caldwell B. Screening the environment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1978;48:114–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1978.tb01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Greenberg MT. Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development. 1990;61:1628–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Allen JL, McGregor K, Woolgar M, Viding E, Scott S. Callous-unemotional traits in children and mechanisms of impaired eye contact during expressions of love: a treatment target? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:771–780. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi M, Vaughn MG. Foundation for a temperament-based theory of antisocial behavior and criminal justice system involvement. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2014;42:10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining Delinquency and Drug Use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:466–491. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine NM, McCrory EJ, Boivin M, Moffitt TE, Viding E. Predictors and outcomes of joint trajectories of callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems in childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(3):730–742. doi: 10.1037/a0022620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick P, Hare R. The Antisocial Process Screening Device. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Frick P. Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits. University of New Orleans; 2004. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Frick P, Ray J, Thornton L, Kahn R. Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:1–57. doi: 10.1037/a0033076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S, Gotlib I. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross HE, Shaw DS, Moilanen K. Reciprocal associations between boys’ externalizing problems and mothers’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:693–709. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9224-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes D, Dadds M, Frost A, Hasking P. Do callous-unemotional traits drive change in parenting practices? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:507–518. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. Four factor index of social status. New Haven, Conn: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Hariri AR. Understanding youth antisocial behavior using neuroscience through a developmental psychopathology lens: Review, integration, and directions for research. Developmental Review. 2013;33:168–223. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Waller R, Burt SA. Improving treatment for youth with Callous-Unemotional traits through the intersection of basic and applied science: Commentary on Dadds et al., (2014) Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:781–783. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D. Personality research form manual. 3. New York: Research Psychologists; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Moffitt T, Taylor A, Pawlby S, Caspi A. Maternal depression and children’s antisocial behavior: nature and nurture effects. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:173–181. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Multiple pathways to conscience for children with different temperaments: From toddlerhood to age 5. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:228–240. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotler J, McMahon R. Assessment of Child & Adolescent Psychopathy. In: Salekin R, Lynam D, editors. Handbook of Child & Adolescent Psychopathy. New York: Guildford; 2010. pp. 79–112. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE. A Dimensional-Spectrum Model of Psychopathology: Progress and Opportunities. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:10–11. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Applegate B, Tackett JL, Waldman ID. Psychometrics of a self-report version of the Child and Adolescent Dispositions Scale. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:351–361. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB. What we need to know about callous-unemotional traits: Comment on Frick, Ray, Thornton, and Kahn (2014) Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:58–63. doi: 10.1037/a0033387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke HJ, Wallace KM. Short marital-adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living. 1959;21(3):251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Loney B, Huntenburg A, Counts-Allan C, Schmeelk K. A preliminary examination of the intergenerational continuity of maternal psychopathic features. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:14–25. doi: 10.1002/ab.20163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald K. Warmth as a developmental construct: an evolutionary analysis. Child Development. 1992;63:753–773. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus Version 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Lochman JE, Powell N. The development of callous-unemotional traits and antisocial behavior in children: are there shared and/or unique predictors? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:319–333. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Castalia: Eugene, OR; 1982. A social learning approach. [Google Scholar]

- Sitnick SL, Shaw DS, Hyde LW. Precursors of adolescent substance use from early childhood and early adolescence: Testing a developmental cascade model. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26:125–140. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ. Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:493–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00916316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DS. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Criss M, Schonberg M, Beck J. The development of family hierarchies and their relation to children’s conduct problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:483–500. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Hyde LW, Brennan LM. Early predictors of boys’ antisocial trajectories. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:871–888. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Shelleby EC. Early-onset conduct problems: intersection of conduct problems and poverty. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153650. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS. Maternal predictors of rejecting parenting and early adolescent antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:247–259. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somech L, Elizur Y. Promoting self-regulation and cooperation in prekindergarten children with conduct problems: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viding E, Frick P, Plomin R. Aetiology of the relationship between callous–unemotional traits and conduct problems in childhood. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190:s33–s38. doi: 10.1192/bjp.190.5.s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman ID, Tackett JL, Van Hulle CA, Applegate B, Pardini D, Frick PJ, Lahey BB. Child and adolescent conduct disorder substantially shares genetic influences with three socioemotional dispositions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:57–70. doi: 10.1037/a0021351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Do harsh and positive parenting predict parent reports of deceitful-callous behavior in early childhood? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:946–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN. Validity of a brief measure of parental affective attitudes in high-risk preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:945–955. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9621-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde LW. What are the associations between parenting, callous–unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Viding E, Shaw DS, Dishion T, Wilson M, Hyde L. Bidirectional associations between parental warmth, callous unemotional behavior, and behavior problems in high-risk preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:1275–1285. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9871-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Hyde LW, Grabell A, Alves M, Olson SL. Differential associations of early callous-unemotional, ODD, and ADHD behaviors: multiple pathways to conduct problems? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12326. in press. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderbilt-Adriance E, Shaw DS. Protective factors and the development of resilience in the context of neighborhood disadvantage. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:887–901. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9220-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikström PO, Loeber R. Do disadvantaged neighborhoods cause well-adjusted children to become adolescent delinquents? Criminology. 2000;38:1109–1142. [Google Scholar]