Abstract

Background & Aims

Production of interferon (IFN)γ by natural killer (NK) cells is attenuated during chronic infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). We investigated whether this is due to intrinsic or extrinsic mechanisms of NK cells.

Methods

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were collected from patients with chronic HCV infection or uninfected blood donors (controls); NK cells and monocytes were isolated or eliminated. We cultured hepatoma cells that express luciferase-tagged subgenomic HCV replicons (Huh7/HCV replicon cells), or their HCV-negative counterparts (Huh7), with NK cells in the presence or absence of other populations of PBMC. Antiviral activity, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production were assessed.

Results

NK cells produced greater amounts of IFN-γ when PBMC were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV replicon cells than with Huh7 cells; NK cells and PBMC from controls suppressed HCV replication to a greater extent than those from patients with chronic HCV infection. This antiviral effect was predominantly mediated by tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α and IFNγ. The antiviral activity of NK cells and their production of IFNγ were reduced when they were used in co-culture alone (rather than with PBMC), or after depletion of CD14+ monocytes, following knockdown of the inflammasome in monocytes, or after neutralization of interleukin (IL)18, which is regulated by the inflammasome. These findings indicate the role for monocytes in NK cell activation. Compared with control monocytes, monocytes from patients with chronic HCV infection had reduced TNFα-mediated (direct) and reduced NK-cell mediated (indirect) antiviral effects. Control monocytes increased the antiviral effects of NK cells from patients with chronic HCV infection and their production of IFNγ.

Conclusions

Monocytes sense cells that contain replicating HCV and respond by producing IL18, via the inflammasome and by activating NK cells. Patients with chronic HCV infection have reduced monocyte function, attenuating NK cell IFNγ-mediated responses.

Keywords: immune response, cytokine production, hepatocyte, viral replication

Introduction

Viral infections typically elicit a rapid response of the innate immune system, which limits viral spread and stimulate the adaptive immune system to clear the infection. NK cells constitute an important innate effector population. They can be activated by cytokines, by a relative reduction of inhibitory signals or by an increase in signals from activating receptors. In an optimal situation, their activation results in the elimination of infected cells via antiviral cytokines and cytotoxicity, and in the recruitment of cells of the adaptive immune response 1.

NK cells are activated in patients with chronic HCV infection 2, 3, 4, but their effector function is biased towards cytotoxicity, and IFN-γ production is attenuated 2, 3. IFN-γ is an important antiviral cytokine, because it inhibits HCV replication in vitro 5 and is detected in the liver in acute HCV infection at the time of T-cell mediated HCV clearance 6, 7. The mechanism for the attenuation of IFN-γ production by NK cells is unknown.

Due to the lack of small animals models of HCV infection, several in vitro models have been used to study the activation and effector function of NK cells. The first studies reported that recombinant HCV E2 protein and HCV virions, when coated on tissue culture plates, crosslink CD81 on NK cells 8-10 and inhibit NK cell activation and IFN-γ production. However, soluble HCV virions do not have this effect 11, suggesting that E2 protein and/or HCV virions must be immobilized, perhaps on the surface of infected cells, if they were to exert an immunosuppressive effect in vivo. Other studies described that cell-to-cell contact between isolated NK cells and HCV-infected hepatocytes impairs the capacity of NK cells to produce IFN-γ and to degranulate and lyse target cells 12. However, these studies were performed with isolated NK cells and did not take into account cytokine- and/or contact-dependent signals from accessory cells, which have been reported to optimize NK cell responses 13. Indeed, a recent study reported activation rather than inhibition of NK cells if these were incubated with HCV-infected hepatoma cells in the presence of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) 14.

Here, we show that NK cells respond to HCV-replicating hepatocytes with IFN-γ-mediated downregulation of HCV replication. This antiviral mechanism requires monocytes, which stimulate NK cell cytokine production by inflammasome-dependent secretion of IL-18. We also demonstrate that a decreased ability of monocytes to respond to HCV-replicating hepatoma cells rather than an intrinsic NK cell defect is responsible for the attenuated IFN-γ response of NK cells in chronic HCV infection.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of PBMC and PBMC subfractions

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated from buffy coats or heparin-anticoagulated blood from chronically HCV-infected (Suppl. Table 1) or uninfected subjects on Ficoll-Histopaque (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) and washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Mediatech). Monocytes or pDCs were depleted with CD14+ or CD304 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), respectively. Alternatively, NK cells and monocytes were negatively selected with NK and Pan-Monocyte isolation kits, respectively (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of CD14- PBMC, CD3-CD14+ monocytes and CD3-CD56+ NK cells was 90–97%. All subjects consented under protocols approved by the institutional review boards of NIDDK/NIAMS or NCI.

Co-culture of PBMC or their subsets with Huh7-derived cell lines

Huh7 cells transfected with a subgenomic HCV replicon (Huh7/HCV-replicon cells) 15, Huh7 cells, or Huh7 cells stably transfected with HCV NS3–NS5A-expressing or NS5B-expressing (Huh7/HCV NS3-5A+5B) lentiviral vectors or an empty vector (Huh7/BLR) were cultured with or without PBMC or their indicated subpopulations in RPMI1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Serum Source International, Charlotte, NC), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine (Mediatech) at 37°C, 5% CO2. After 24h, the following parameters were assessed:

Antiviral activity

Huh7/HCV-replicon cells were washed twice with PBS, and luciferase activity was determined with the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) using a POLARstar Omega instrument (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC).

Cytotoxicity and cytokine release

Lactate dehydrogenase was quantitated in the co-culture supernatant as a read-out for cytoxicity using the CytoTox 96 kit (Promega). IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12, IL-15, IL-17, IFN-γ, TNF-α, CCL2, CCL4, CCL5 and CXCL10 were quantitated in 1:4 diluted supernatants using the Luminex Assay (Biorad, Hercules, CA). IL-18, TNF-α and IFN-γ were quantitated in undiluted supernatants using EIAs for TNF-α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and for IL-18 and IFN-γ (eBioscience). IFN-α was quantitated by cytometric bead array (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Monocyte activation and NK cell IFN-γ production

PBMC were collected from the co-culture by careful pipetting. Monocyte activation was assessed by staining with ethidium monoazide (EMA), anti-CD19-PeCy5, anti-CD14-PB, anti-CD3-AlexaFluor700 and anti-CD16-Violet500, anti-HLA-DR-FITC and anti-CD69-PE (all from BD Biosciences). NK cell function was assessed after incubation with brefeldin A for the final 3h of the 24h co-culture with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells or Huh7 cells. Alternatively, lymphocytes were removed and exposed to IL-12 (0.5 ng/ml) and IL-15 (20 ng/ml; both from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for an additional 18h with addition of brefeldin A for the last 4h as described 2. Cells were then washed and stained with EMA, anti-CD19-PeCy5 (BD Biosciences), anti-CD14-PeCy5 (Abd-Serotec, Raleigh, NC) to exclude dead cells, B cells and monocytes, and with anti-CD3-AlexaFluor700, anti-CD56-PeCy7 and anti-CD16-PacificBlue to identify NK cells. Cells were washed again, fixed and permeabilized with the Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit, stained with anti-IFN-γ-Pe (BD Biosciences), washed, and immediately analyzed on an LSRII flow cytometer using FacsDiva Version 6.1.3 (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo Version 8.8.2 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) software.

Cytokine neutralization assay

Huh7/HCV-replicon cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml TNF-α inhibitor (Enbrel, Immunex Corporation, Seattle, WA), 2 μg/ml IFN-γ R1 antibody or isotype control, 0.5 μg/ml IL-18 binding protein (all from R&D Systems), 10 μg/ml anti-IFN-α (PBL Interferon Source, Piscataway, NJ) and 10 μg/ml anti-IFN-β (R&D Systems) or 0.2 μg/mL of the vaccinia virus–encoded B18 receptor protein (VV B18R, eBiosciences), which competes with the IFN-α/β receptor for IFN binding, prior to addition of PBMC. After 24h, antiviral activity and IFN-γ production were determined as described above.

Co-culture of PBMC or their subsets with HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells

Huh7.5 cells were infected with HCV (JFH-1 strain) at a multiplicity of infection of 1 in DMEM containing 3% FBS, 1 g/ml glucose, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine. After 6h, the culture medium was replaced with the same medium but containing 10% FBS. After 72h the culture medium was replaced with RPMI1640 containing 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine. The efficiency of HCV infection was verified by extraction of intracellular RNA using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), reverse transcription and HCV RNA quantitative PCR as described 16. The HCV RNA copy number was determined per μg total RNA. PBMC or CD14-depleted PBMC were added to Huh7.5 cells 72h after HCV infection at an E:T ratio of 20:1, and NK cell IFN-γ production was assessed after 24h of co-culture.

siRNA transfection of primary human monocytes

Negatively selected CD 14+ monocytes were incubated for 2h at 106 cells/well in 24-well plates (Ultra-Low Attachment Surface, Costar) in Optimem (Gibco) containing 1% FBS without antibiotics. 50 nm of siRNAs targeting NALP-3 (SR314415A, SR314415B, SR314415C), RIG-I (SR308383A, SR308383B, SR308383C) or non-target controls (SR30004, all from Origene, Rockville, MD) were incubated with 9 μl Hi-Perfect reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), respectively, for 15 min at RT to allow the formation of transfection complexes. The mix was added to the monocyte culture for 6h at 37°C, followed by addition of RPMI1640 with 10% human serum (GemCell BioProducts, West Sacramento CA) and 2 mM L-glutamine. After 48h, the transfected monocytes were mixed with autologous CD14-depleted PBMC, and co-cultured for 24h with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells as described.

To confirm target knockdown, 5 million cells/mL siRNA-transfected monocytes were in Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signal Technology, Danvers MA) and the cytoplasmic fraction was separated by SDS PAGE on 4-12% Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blotted using Western Breeze Rabbit Chemiluminescent Western Blot Immunodetection Kit (Life Technologies) and human NALP3 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Imgenex, San Diego CA), human RIG-I rabbit monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers MA), and human Actin rabbit monoclonal antibody (Sigma, St. Louis MO). Blots were developed with Anti Rabbit IgG (HRP Cell Signal Technology) and ECL Prime Western Blot Detection Reagents (Amersham, Pittsburg, PA).

Statistical Analysis

D'Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality tests were used to determine the data distribution. Wilcoxon-signed-rank tests, Mann-Whitney tests and linear regression analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0a (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Two-sided p-values <.05 were considered significant.

Results

PBMC exert a greater cytokine-mediated antiviral effect than isolated NK cells in co-cultures with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells

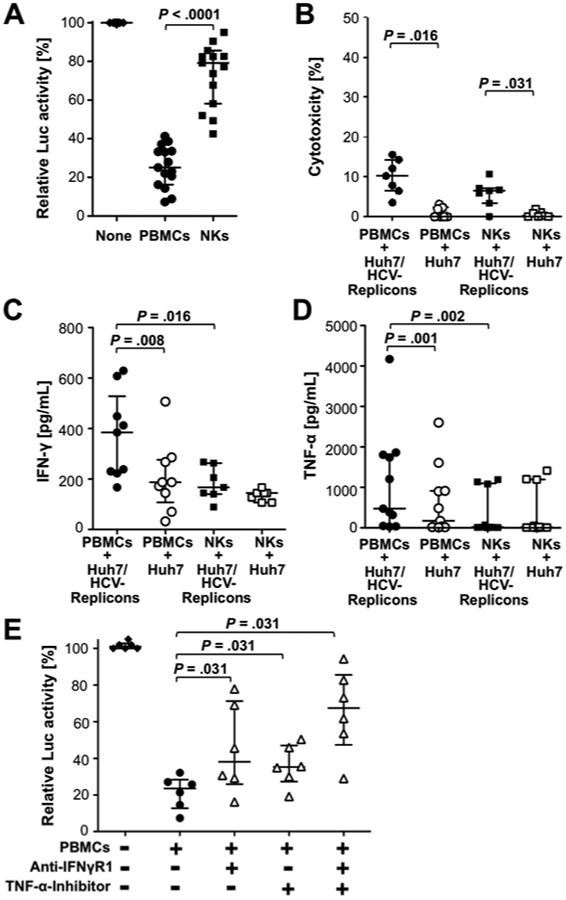

To assess the antiviral activity of NK cells, we co-cultured PBMC from healthy blood donors with Huh7 cells that were stably transfected with a luciferase-tagged subgenomic HCV-replicon (Huh7/HCV-replicon cells). Whereas PBMC downregulated HCV replication by 74.9%, isolated NK cells decreased replication by only 20.8% (P<.0001) at an E:T ratio adjusted to the frequency of NK cells in PBMC (Fig. 1A). Downregulation of HCV replication was associated with minimal cytotoxicity (Fig. 1B), but high levels of the antiviral cytokines IFN-γ (Fig. 1C) and TNF-α (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, higher cytokine levels were observed in the presence of PBMC than in presence of isolated NK cells (Fig. 1C, D). The addition of a IFN-γ receptor blocker and a TNF-α inhibitor increased HCV replication in an additive manner (P=.031, Fig. 1E). While low levels of IFN-α (7.5-9 pg/mL) were also detectable, they did not differ in co-cultures with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells and co-cultures with Huh7 cells (not shown).

Figure 1. PBMC exert a greater cytokine-mediated antiviral effect than isolated NK cells in co-cultures with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells.

PBMC or NK cells from healthy donors were incubated for 24h with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells or Huh7 cells at an E:T ratio of 20:1 for PBMC and 2:1 for NK cells, as NK cells constitute about 10% of PBMC.

(A) Luciferase activity was assessed as a read-out for HCV replication.

(B) LDH release was assessed as a read-out for cytotoxicity. Results are relative to maximal cytotoxicity in the presence of 10% triton X.

(C, D) IFN-γ (C) and TNF-α (D) were quantitated in the supernatants.

(E) PBMC were incubated with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells with an antibody against the IFN-γ receptor 1 (IFN-γ R1), a TNF-α inhibitor or both, and luciferase activity was assessed. Statistical analysis: Wilcoxon-signed-rank test. Median and IQR are shown.

PBMC subpopulations contribute to the magnitude of the NK cell IFN-γ response

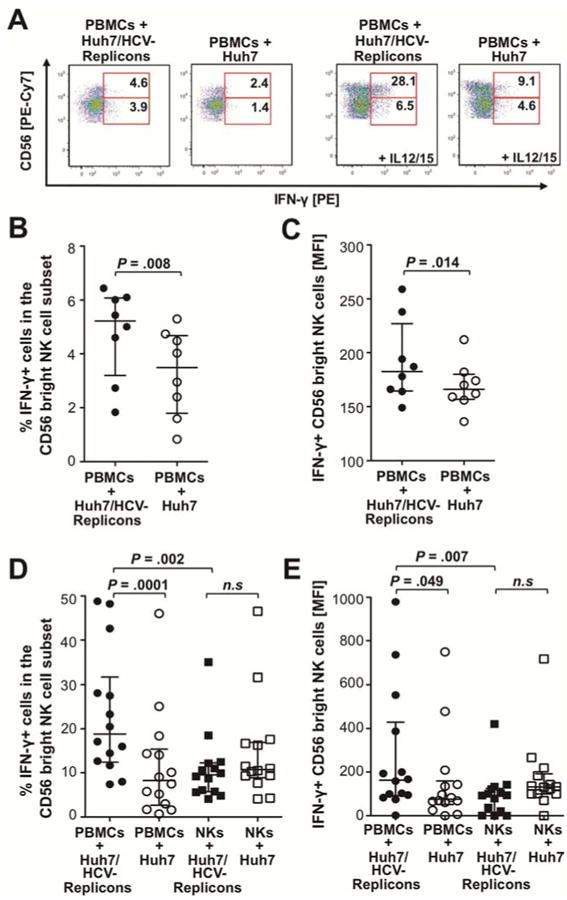

To identify the cytokine source we added brefeldin A during the final 3h prior of the 24 coculture. Brefeldin A prevents the release of cytokines, which can then be detected in defined lymphocyte subsets by flow cytometry (Fig. 2A, left graphs). As shown in figure 2B and 2C, both the frequency and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IFN-γ-producing cells in the CD56bright NK cell subset were greater when PBMC were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells than with Huh7 cells (P=.008 and P=.014, respectively). Similar results were obtained for frequency and MFI of IFN-γ-producing cells in the CD56dim NK cell subset (median frequency 4.1% with IQR 1.5-10.7% vs. 1.6% with IQR 1-5.1%, P=.004; median MFI 51 with IQR 26-106 vs. 15 with IQR 0-37, P=.025, not shown). In contrast, HCV-specific IFN-γ production by T cells was negligible, i.e. detectable in less than 0.2% CD3+ T cells of these healthy blood donor PBMC (not shown).

Figure 2. PBMC subpopulations contribute to the magnitude of the NK cell IFN-γ response.

(A) PBMC from healthy blood donors were incubated with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells or Huh7 cells at an E:T of 20:1. Brefeldin A was added for the last 3h of the 24h co-culture, followed by intracellular staining of the lymphocytes for IFN-γ (two dot plots on left). To increase the sensitivity of the NK cell readout lymphocytes were stimulated with IL-12 (0.5 ng/ml) and IL-15 (20 ng/ml) for additional 18h after removal from the co-culture, followed by intracellular IFN-γ staining (two dot plots on right). The numbers indicate the frequency of IFN-γ+ cells in the CD56bright and CD56dim NK cell subpopulations, respectively.

(B-C) The frequency (B) and MFI (C) of IFN-γ+ cells in the CD56bright NK cell population (without IL-12/15 stimulation) is summarized for all experiments in which PBMC from individual healthy blood donors were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells without further IL-12/IL-15 stimulation.

(D-E) The frequency (D) and MFI (E) of IFN-γ+ cells in the CD56bright NK cell population is summarized for all experiments, in which PBMC or isolated NK cells from individual healthy blood donors were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells, followed by removal and stimulation of the lymphocytes with IL-12/IL-15. Statistical analysis: Wilcoxon-signed-rank test. Median and IQR are shown. N.s., not significant.

To increase the sensitivity of the read-out for HCV-replicon-stimulated IFN-γ production by NK cells, lymphocytes were removed after the 24h co-culture with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells or Huh7 cells and exposed to IL-12 and IL-15 for additional 18h (Fig. 2A, right graphs). As shown in figures 2D and 2E the frequency and MFI of IFN-γ-producing cells in the CD56bright NK cell subset were higher when PBMC rather than isolated NK cells were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV replicon cells followed by IL-12/IL-15 stimulation (P=.002 and P=.007, respectively). Thus, the presence of other PBMC subpopulations contributed to the NK cell IFN-γ response.

Monocytes are activated and secrete cytokines when co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells

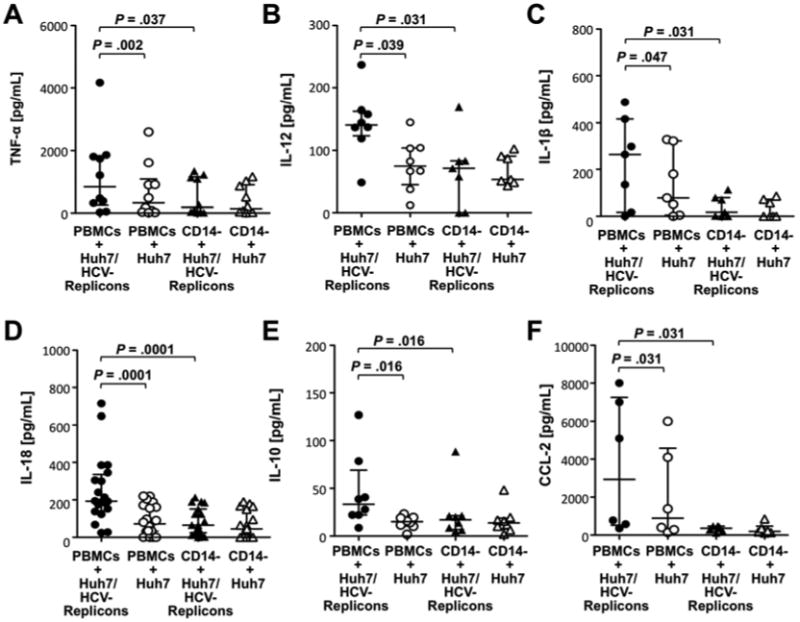

To identify the PBMC subpopulation(s) that enhance the NK cell IFN-γ response, we performed a multiplex analysis of secreted cytokines. Increased levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, IL-18, IL-10, and CCL-2 (Fig. 3) as well as IFN-γ (Fig. 1C) and CXCL10, IL-1RA, CCL4, CCL5, and IL-6 (not shown) were observed in PBMC co-cultures with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells as compared to co-cultures with Huh-7 cells. This cytokine profile was consistent with the presence of activated monocytes and abrogated when CD14+ monocytes were depleted (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Monocyte-derived cytokines are present in co-cultures of Huh7/HCV-replicon cells with PBMC.

PBMC or CD14-depleted PBMC were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells or Huh7 cells for 24h at an E:T ratio of 20:1. The co-culture supernatants were analyzed for TNF-α (A), IL-12 (B), IL-1β (C), IL-18 (D), IL-10 (E) and CCL2 (F) in a multiplex Luminex assay. Statistical analysis: Wilcoxon-signed-rank test. Median and IQR are shown.

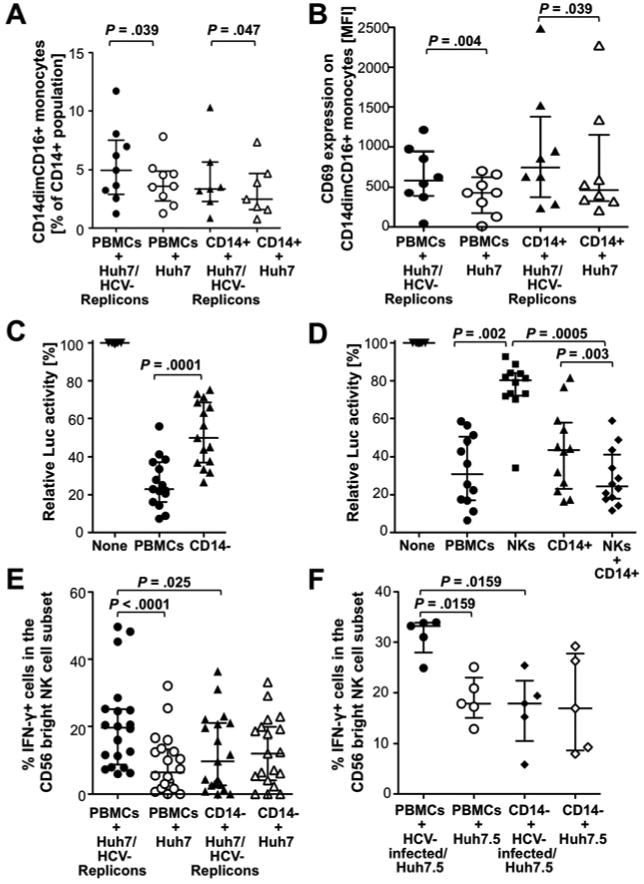

Flow cytometry allowed us to distinguish three monocyte subsets, namely CD14+CD16- monocytes, CD14+CD16+ monocytes and CD14dimCD16+ monocytes. CD14+CD16- monocytes constitute the largest monocyte subset in PBMC (Suppl. Fig. 1A). However, in the 24h co-culture of PBMC with Huh7 cells and in particular with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells, there was a significant increase in the size of the more mature CD14+CD16+ monocyte subset (median increase of 22% in co-cultures with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells compared to Huh7 cells, P=.009, not shown) and the CD14dimCD16+ monocyte subset (P=.039, Fig. 4A). The latter subset is known to respond to viruses and nucleic acids with production of proinflammatory cytokines 17. Moreover, in contrast to CD14+CD16- monocytes (Supp. Fig. 1B), CD14+CD16+ and CD14dimCD16+ monocytes also expressed higher levels of CD69 when they were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells rather than with Huh7 cells (P=.039, Suppl. Fig. 1C, Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Activated monocytes contribute to IFN-γ production and antiviral activity of CD56bright NK cells in the presence of Huh7/HCV-replicon cells.

(A-B) PBMC or CD14+ monocytes were co-cultured at E:T ratios of 20:1 and 5:1, respectively, with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells or Huh7 cells. After 24h, frequency (A) and CD69 expression (B) of CD14dimCD16+ monocytes were analyzed.

(C-D) PBMC and CD14-depleted PBMC at E:T ratios of 20:1 (C) or PBMC, NK cells and/or CD14+ monocytes at E:T ratios of 20:1, 2:1 and 5:1, respectively, (D) were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells for 24h, followed by assessment of luciferase expression as readout for HCV replication.

(E-F) PBMC or CD14-depleted PBMC from healthy donors were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells or Huh7 cells (E) or with HCV-infected or not infected Huh-7.5 cells (F) at an E:T ratio of 20:1 for 24h, followed by assessment of the frequency of CD56bright NK cells that responded to subsequent IL-12/IL-15 stimulation with IFN-γ production. Statistical analysis: Wilcoxon-signed-rank test. Median and IQR are shown.

Depletion of CD14+ monocytes from PBMC reduces antiviral activity and HCV-specific IFN-γ production of NK cells

To distinguish between a direct antiviral role of monocytes and an indirect role via stimulation of IFN-γ production by NK cells, we co-cultured PBMC or CD14-depleted PBMC with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells or Huh7 cells. The suppression of HCV replication decreased when CD14+ monocytes were depleted from PBMC (P=.0001, Fig. 4C). While isolated monocytes exhibited a greater antiviral effect than isolated NK cells at E:T ratios adjusted to their respective frequency in PBMC, both NK cells and monocytes were required to achieve the same antiviral effect as bulk PBMC (Fig. 4D). The effect of monocytes on NK cell function was evidenced by the decrease in the frequency of IFN-γ+ CD56bright NK cells when monocytes were depleted from PBMC (median frequency of IFN-γ+ CD56bright NK cells 19.6%, IQR 8.8-25.1% vs. 9.8%, IQR 2.6-21%, P=.025; Fig. 4E). Depletion of monocytes also abolished the differential NK cell response to Huh7/HCV-replicon cells and Huh7 cells (Fig. 4E, Suppl. Fig. 2A). The role of monocytes in NK cell IFN-γ production was confirmed in the HCV infection system, because depletion of CD14+ cells from PBMC prior to co-culture with HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells reduced the frequency (P=.0159, Fig. 4F) and the MFI (P=.032, Suppl. Fig. 2B) of IFN-γ-producing cells in the CD56bright NK cell subset and abrogated the differential response to infected and uninfected Huh7.5 cells (Fig. 4F, Suppl. Fig. 2B). In contrast, depletion of IFN-α-producing pDCs from PBMC or blocking of IFN-α/β did not affect NK cell function (not shown).

To evaluate whether HCV replication was required or whether expression of HCV antigens was sufficient for monocyte activation, we utilized Huh7 cells that were stably transfected either with HCV NS3-NS5A-expressing and NS5B-expressing lentiviral vectors (Huh7/HCV NS3-5A+5B) or with an empty vector (Huh7/BLR). Expression of HCV antigens in the absence of replication did neither induce IL-18 (Suppl. Fig. 3A) nor CD69 expression on monocytes (Suppl. Fig. 3B).

Monocyte–derived IL-18 activates NK cells

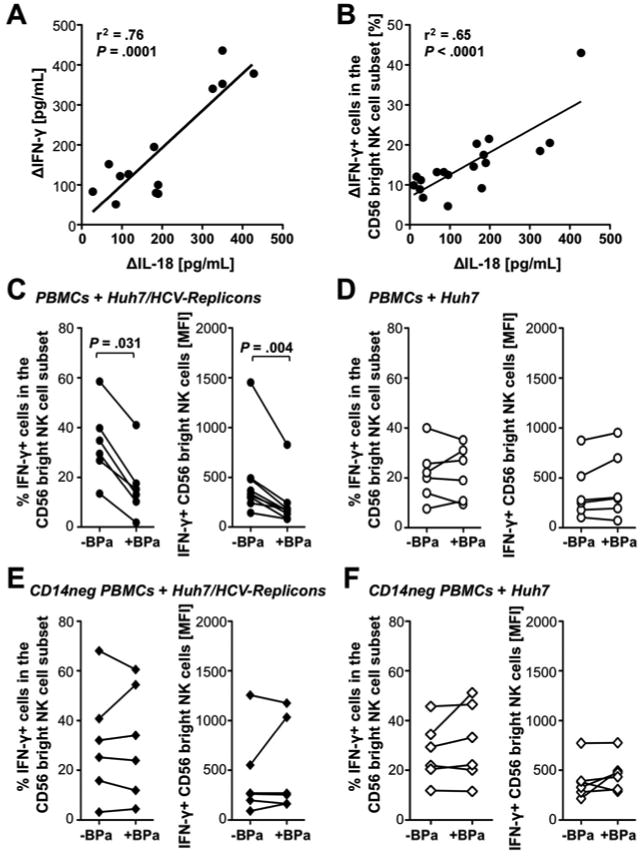

Having established that monocytes contribute to NK cell IFN-γ production, we tried to identify the underlying mechanism. As shown in Figure 5, the level of secreted IL-18 correlated with the level of secreted IFN-γ in the co-culture supernatant (r2=0.76, P=.0001; Fig. 5A) and with the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells in the CD56bright NK cell population (r2=.65, P<.0001, Fig. 5B). In contrast, IL-1β and IL-12 levels did not correlate with IFN-γ production by NK cells, IL-15 was detected at similar levels in co-cultures with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells and Huh7 cells and IFN-α was not detected (not shown).

Figure 5. Monocyte–derived IL-18 plays a central role in the activation of NK cells in response to Huh7/HCV-replicon cells.

(A-B) PBMC from healthy donors were incubated with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells or Huh7 cells at an E:T ratio of 20:1. The level of secreted IL-18 correlated in linear regression analyses with the level of secreted IFN-γ (A) and with the frequency of CD56bright NK cells that responded to subsequent IL-12/15 stimulation with IFN-γ production (B) in linear regression analyses. The delta indicates that the value in co-cultures with Huh7 cells was subtracted from the value in co-cultures with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells.

(C-F) PBMC (C, D) or CD14-depleted (CD14neg) PBMC (E, F) from healthy donors were incubated with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells (C, E) or Huh7 cells (D, F) with or without IL-18-binding protein (BPa) at an E:T ratio of 20:1. The frequency and MFI of CD56bright NK cells that responded to subsequent IL-12/15 stimulation with IFN-γ production were determined. Statistical analysis: Wilcoxon-signed-rank test.

To determine whether IL-18 contributed to monocyte-driven NK cell activation, PBMC or CD14-depleted PBMC from healthy blood donors were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells or Huh7 cells with or without the IL-18-binding protein BPa. Addition of BPa resulted in a decrease of both percentage and MFI of IFN-γ+ cells in the CD56bright NK cell population (P=.031 and P=.004, respectively, Fig. 5C), which was not observed when Huh7 (Fig. 5D) or CD14-depleted PBMC (Fig. 5E, F) were used.

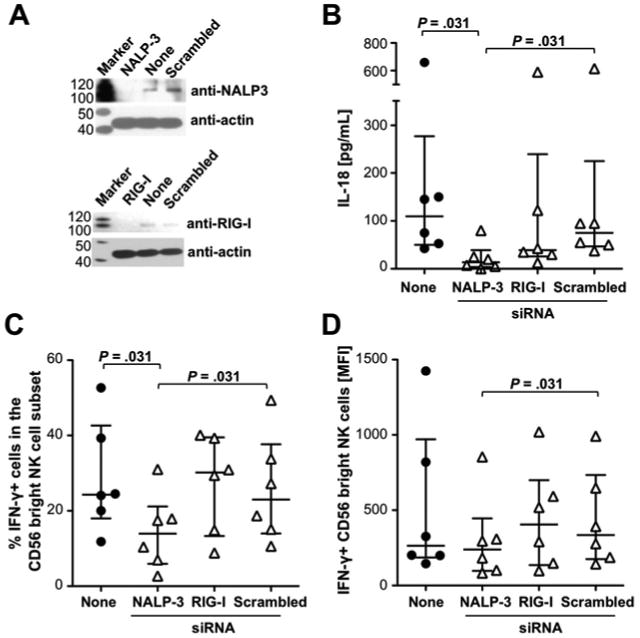

The production of IL-18 requires its release from a precursor protein by an intracellular caspase, which is activated by the NALP3 inflammasome 18. To evaluate whether IFN-γ production by NK cells was secondary to NALP3 inflammasome activation in monocytes, CD14+ monocytes were transfected with NALP3-specific siRNA, or with scrambled siRNA as a negative control. RIG-I-specific siRNA was used as a second control because HCV does not infect and replicate in monocytes 19 and thus, should not stimulate RIG-I in the cytoplasm. NALP3 and RIG-I knockdown were confirmed by Western Blot (Fig. 6A) and the transfected monocytes were added to autologous CD14-depleted PBMC and co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells. Silencing of NALP3 but not RIG-I resulted in a significant decrease of IL-18 levels compared to transfection with scrambled siRNA or no transfection (P=.031, Fig. 6B). Consistent with these results, silencing of NALP3 but not RIG-I resulted in a significant decrease in both the percentage and the MFI of IFN-γ+ CD56bright NK cells compared to transfection with scrambled siRNA (P=.031, Fig. 6C, D). Collectively, these results demonstrate that Huh7/HCV-replicon cells activate the NALP3 inflammasome in monocytes resulting in IL-18-mediated stimulation of NK cell IFN-γ production.

Figure 6. Knockdown of the NALP3 inflammasome but not RIG-I in primary human monocytes decreases IL-18 levels and NK cell-mediated IFN-γ production in response to HCV-replication.

(A) Knockdown of RIG-I and NALP-3 in CD14+ primary human monocytes 48h after transfection with or without the indicated siRNA assessed by Western Blot.

(B-D) si-RNA-treated or not treated (none) CD14+ monocytes were co-cultured with CD14-depleted autologous PBMC and Huh7/HCV-replicon cells. After 24h the level of secreted IL-18 (B) and the frequency (C) and MFI (D) of CD56bright NK cells that responded to subsequent IL-12/15 stimulation with IFN-γ production were determined. Statistical analysis: nonparametric Wilcoxon-signed rank test. Median and IQR are shown.

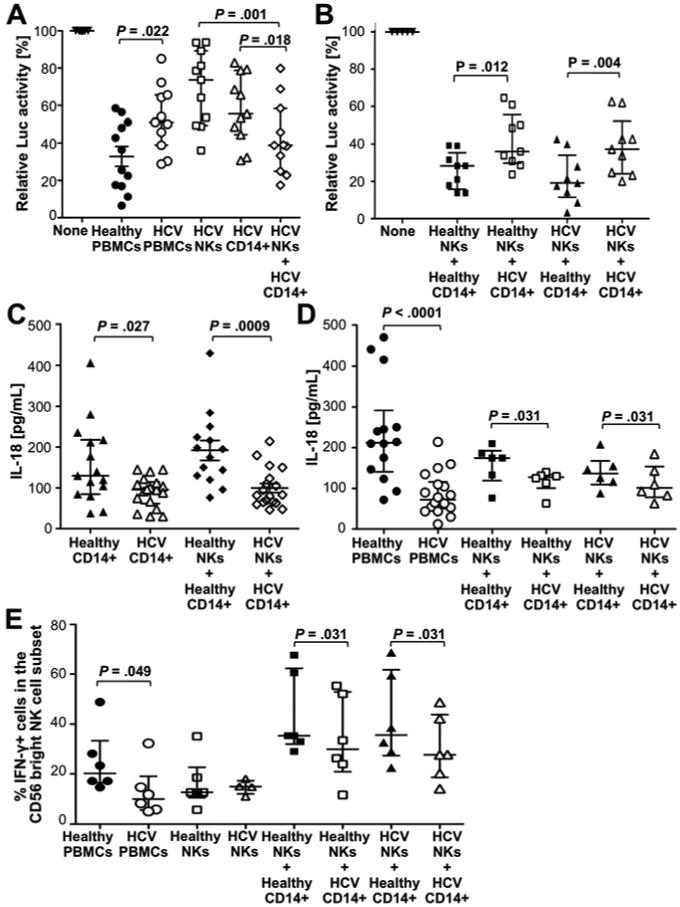

Monocytes from chronic HCV patients are less effective in inducing antiviral functions of NK cells than monocytes from healthy controls

We 2 and others 3 have described that NK cells are attenuated in their capacity to produce IFN-γ in chronic HCV infection. We therefore asked whether this attenuation due to an altered monocyte function or to an intrinsic NK cell defect. Consistent with the results obtained with cells from healthy blood donors (Fig. 4D), both monocytes and NK cells from HCV-infected patients were required to reproduce the antiviral effect of PBMC from the same individuals (Fig. 7A). However, PBMC of HCV-infected patients had a significantly reduced antiviral effect compared to PBMC of healthy blood donors (median luciferase activity of 51.1.% [IQR, 38.8%-65.6%] vs 30.8% [IQR, 17%-50.3%], P=.022, Fig. 7A). In mix-and-match experiments, a greater antiviral effect was observed when monocytes from healthy blood donors rather than monocytes from HCV-infected patients were added to NK cells from either healthy controls (P=.012) or HCV patients (P=.004) (Fig. 7B). Thus, the attenuated antiviral function of NK cells from chronic HCV patients is monocyte-driven rather than an NK cell intrinsic. Indeed, monocytes but not NK cells from chronic HCV patients produced lower levels of the antiviral cytokine TNF-α than those from healthy controls (P=.0003, Suppl. Fig. 4). Monocytes from HCV-infected patients also produced lower amounts of IL-18 than monocytes from healthy controls when they were co-cultured alone (P=.027, Fig. 7C) or in the context of full PBMC (P<.0001, Fig. 7D) with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells. Finally, monocytes from HCV patients were less effective than monocytes from healthy controls in stimulating the IFN-γ production of CD56bright NK cells (P=.031, Fig. 7E). In contrast, in the absence of monocytes there was no difference in the IFN-γ response of CD56bright NK cells from HCV-infected patients and healthy controls (Fig. 7E). Thus, monocytes from HCV-infected patients produce less cytokines than monocytes from healthy controls, which reduces their direct antiviral effect, and, via impairment of NK cell IFN-γ production, their indirect antiviral effect.

Figure 7. Monocytes of chronic HCV patients are less effective in inducing antiviral functions of NK cells than those of healthy controls.

(A) PBMC from HCV-infected (HCV) or healthy subjects (healthy), or NK cells and/or CD14+ monocytes from HCV-infected patients were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells at E:T ratios of 20:1, 2:1 and 5:1, respectively. After 24h, luciferase expression was assessed as readout for HCV replication.

(B) Combinations of CD14+ monocytes and NK cells from HCV-infected (HCV) or healthy donors (healthy) were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells at E:T ratios of 2:1 and 5:1, respectively. Luciferase expression was assessed as in panel A.

(C-E) CD14+ monocytes (C), PBMC and combinations of monocytes and NK cells (D, E) from HCV patients and healthy controls were co-cultured with Huh7/HCV-replicon cells. The amount of secreted IL-18 (C, D) and the frequency of CD56bright NK cells that responded to subsequent IL-12/15 stimulation with IFN-γ production (E) were assessed.

Statistical analysis: Wilcoxon-signed-rank test or nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Median and IQR are shown.

Discussion

In this study we used an in vitro model of HCV replication to investigate mechanisms of NK cell activation and antiviral function. We showed that NK cells from healthy subjects sense HCV-replicating hepatoma cells even though no HCV virions are produced. Similar to CD8 T cells in this model 15, NK cells mediate their antiviral effect predominantly through cytokine production rather than cytotoxicity. Moreover, similar to CD8 T cells from patients with chronic HCV infection 20, 21, NK cells from patients with chronic HCV infection are attenuated in their IFN-γ-mediated antiviral activity 2, 3 (Fig. 7). In contrast to CD8 T cell exhaustion, however, this attenuation of NK cell IFN-γ production is not due to an intrinsic mechanism but due to a suboptimal function of monocytes (Fig. 7).

The role of monocytes as an important accessory cell population was demonstrated by a significant reduction of NK cell IFN-γ production and antiviral function when CD14+ cells were depleted from PBMC (Fig. 4), and when isolated NK cells rather than total PBMC were incubated with the Huh7/HCV-replicon cells (Fig. 1). In addition, the HCV-replicon-specific recognition was lost, i.e. NK cell function in the presence Huh7/HCV-replicon cells did not differ from that in the presence of Huh7 cells. These findings may explain why significant NK cell IFN-γ secretion was not observed in an earlier study, in which isolated NK cells were co-cultured with HCV-infected hepatoma cells in the absence of monocytes 12.

Thus, monocytes exert a direct antiviral function via production of TNF-α (Fig. 1E, Suppl. Fig. 4) and possibly other monokines (Fig. 3) and an indirect antiviral function via IL-18-mediated stimulation of NK cells. A role of IL-15 in NK cell activation is also possible because this cytokine is trans-presented on the IL-15 receptor 22 and thus, not necessarily detectable at increased concentrations in the co-culture supernatant.

These findings are of interest in the context of a recent study by Negash et al. who showed that phagocytosis of HCV virions by macrophages but not monocytes stimulates TLR7 and inflammasome-mediated production of IL-1β 23. The discrepant findings to our study can be explained by the differential functions of monocytes and macrophages, reflecting their separate roles in inflammation and host defense. In both cell populations TLR ligation induces the precursor forms of IL-1β and IL-18, but the requirements for posttranslational processing and release of these cytokines are different. Specifically, monocytes but not macrophages have constitutively increased intracellular levels of caspase-1 and thus can cleave the cytokines from their precursor form 24. In addition, monocytes release endogenous ATP 24 to bind to the P2X7 receptor, which results in the opening of a potassium channel, the decrease in intracellular potassium concentration 25 and ultimately cytokine secretion. Therefore, monocytes can release active IL-1β and IL-18 after a single TLR stimulation whereas macrophages need additional stimuli to convert inactive to active caspase and to process and secrete the cytokines 18. Phagocytosis of HCV virions rather than exposure to HCV RNA may provide these additional signals to macrophages. In contrast, monocyte activation may be triggered either by altered expression of cell surface molecules on the surface of HCV-replicating cells or by HCV RNA released in exosomes. Indeed, RNA-containing exosomes were recently described to activate pDCs 26, 27, nuclease-resistant HCV RNA-containing structures have been detected in the culture supernatant in our model 28, and inflammasome activation in monocytes is stimulated via TLR7/8-mediated sensing of RNA 17.

The inflammasome-mediated secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 by monocytes in response to HCV RNA may constitute an important negative feedback loop. While Negash et al. propose that macrophage-derived IL-1β drives liver inflammation and disease pathogenesis 23, we here show that monocyte-derived IL-18 activates NK cells. NK cell activation results in downregulation of HCV replication, which may have an anti-inflammatory effect by reducing monocyte and macrophage stimulation. These findings also extend the results by Zhang et al. who showed an induction of interferon-stimulated genes in co-cultures of PBMC with HCV-infected hepatoma cells but did not assess their antiviral effect 14. Furthermore, while Zhang et al. propose a primary role of pDCs rather than monocytes in NK cell activation we observed no significant effect of pDC depletion or IFN-α/β blockade on NK cell IFN-γ production (not shown). These results indicate that monocyte-derived IL-18 plays a greater role in NK cell stimulation than pDC-derived IFN-α in our model.

A limitation of the current and previous studies is the use of mononuclear cell populations from the blood rather than liver. However, several points support the biological relevance of our findings. First, high levels of IL-18 mark both acute 29 and chronic hepatitis C 23. Second, hepatic macrophages show increased inflammasome activity in chronic HCV infection 23. Collectively, these results demonstrate that NK cells should be studied within a network of other immune cells rather than in isolation. They also point to monocytes as interesting modulators of the intrahepatic immune response.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Xenia Chepa-Lotrea for technical support and Nevitt Morris for clinical support.

Financial Support: This study was supported by the NIDDK, NIH intramural research program. J. M. W. was supported by grant We-4675/1-1 from the Deutsche Forschungs-gemeinschaft (DFG), Bonn, Germany.

Abbreviations

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- NK

natural killer

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- Luc

luciferase

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis α

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- MIP-1β

Macrophage-inducing protein 1β

- IL

interleukin

- CCL-2

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

- BPa

binding protein a

- RIG-I

retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 RNA helicase

- NALP3

nod-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3

Footnotes

Author Contributions: ES, JMW and BR designed the study. ES, JMW and MAC performed experiments. MAC, ALC and VL provided critical input into experimental design, and VL provided reagents. ES, JMW and BR wrote the manuscript, which was critiqued by all authors.

Financial Disclosures and Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Elisavet Serti, Email: elisavet.serti@nih.gov.

Jens M. Werner, Email: Jens.Werner@ukr.de.

Michael Chattergoon, Email: chattergoon@jhu.edu.

Andrea L. Cox, Email: acox@jhmi.edu.

Volker Lohmann, Email: volker_lohmann@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

References

- 1.Vivier E, Raulet DH, Moretta A, et al. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science. 2011;331:44–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1198687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahlenstiel G, Titerence RH, Koh C, et al. Natural killer cells are polarized toward cytotoxicity in chronic hepatitis C in an interferon-alfa-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:325–35. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliviero B, Varchetta S, Paudice E, et al. Natural killer cell functional dichotomy in chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C virus infections. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1151–60. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rehermann B. Pathogenesis of chronic viral hepatitis: Differential roles of T cells and NK cells. Nat Med. 2013;19:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nm.3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frese M, Schwarzle V, Barth K, et al. Interferon-gamma inhibits replication of subgenomic and genomic hepatitis C virus RNAs. Hepatology. 2002;35:694–703. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su AI, Pezacki JP, Wodicka L, et al. Genomic analysis of the host response to hepatitis C virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202608199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin EC, Seifert U, Kato T, et al. Virus-induced type I IFN stimulates generation of immunoproteasomes at the site of infection. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3006–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI29832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crotta S, Stilla A, Wack A, et al. Inhibition of natural killer cells through engagement of CD81 by the major hepatitis C virus envelope protein. J Exp Med. 2002;195:35–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tseng CT, Klimpel GR. Binding of the hepatitis C virus envelope protein E2 to CD81 inhibits natural killer cell functions. J Exp Med. 2002;195:43–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crotta S, Brazzoli M, Piccioli D, et al. Hepatitis C virions subvert natural killer cell activation to generate a cytokine environment permissive for infection. J Hepatol. 2010;52:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon JC, Shiina M, Ahlenstiel G, et al. Natural killer cell function is intact after direct exposure to infectious hepatitis C virions. Hepatology. 2009;49:12–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.22624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon JC, Lim JB, Park JH, et al. Cell-to-cell contact with hepatitis C virus-infected cells reduces functional capacity of natural killer cells. J Virol. 2011;85:12557–12569. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00838-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newman KC, Korbel DS, Hafalla JC, et al. Cross-talk with myeloid accessory cells regulates human natural killer cell interferon-gamma responses to malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e118. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang S, Saha B, Kodys K, et al. IFN-gamma production by human natural killer cells in response to HCV-infected hepatoma cells is dependent on accessory cells. J Hepatol. 2013;59:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jo J, Aichele U, Kersting N, et al. Analysis of CD8+ T-cell-mediated inhibition of hepatitis C virus replication using a novel immunological model. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1391–401. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park H, Serti E, Eke O, et al. IL-29 Is the dominant type III interferon produced by hepatocytes during acute hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2012;56:2060–2070. doi: 10.1002/hep.25897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cros J, Cagnard N, Woollard K, et al. Human CD14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity. 2010;33:375–86. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Netea MG, Nold-Petry CA, Nold MF, et al. Differential requirement for the activation of the inflammasome for processing and release of IL-1beta in monocytes and macrophages. Blood. 2009;113:2324–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-146720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marukian S, Jones CT, Andrus L, et al. Cell culture-produced hepatitis C virus does not infect peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Hepatology. 2008;48:1843–50. doi: 10.1002/hep.22550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wedemeyer H, He XS, Nascimbeni M, et al. Impaired effector function of hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ T cells in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:3447–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seigel B, Bengsch B, Lohmann V, et al. Factors that determine the antiviral efficacy of HCV-specific CD8(+) T cells ex vivo. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:426–36. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mortier E, Woo T, Advincula R, et al. IL-15Ralpha chaperones IL-15 to stable dendritic cell membrane complexes that activate NK cells via trans presentation. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1213–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negash AA, Ramos HJ, Crochet N, et al. IL-1beta production through the NLRP3 inflammasome by hepatic macrophages links hepatitis C virus infection with liver inflammation and disease. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003330. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrari D, Chiozzi P, Falzoni S, et al. Purinergic modulation of interleukin-1 beta release from microglial cells stimulated with bacterial endotoxin. J Exp Med. 1997;185:579–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, et al. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1583–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi K, Asabe S, Wieland S, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense hepatitis C virus-infected cells, produce interferon, and inhibit infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7431–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002301107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dreux M, Garaigorta U, Boyd B, et al. Short-range exosomal transfer of viral RNA from infected cells to plasmacytoid dendritic cells triggers innate immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:558–70. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pietschmann T, Lohmann V, Kaul A, et al. Persistent and transient replication of full-length hepatitis C virus genomes in cell culture. J Virol. 2002;76:4008–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.4008-4021.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chattergoon MA, Levine JS, Latanich R, et al. High plasma interleukin-18 levels mark the acute phase of hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1730–40. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.