Abstract

Objective

Discontinuities in health insurance coverage may make it difficult for individuals early in psychosis to receive the services that are critical in determining long-term outcome. This study reports on the rates and continuity of insurance coverage among a cohort of early-psychosis patients enrolled in Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis (STEP) at the Connecticut Mental Health Center.

Methods

Insurance status at baseline, six months, and 12 months was collected from 82 participants from a combination of self-reports, clinical chart review, clinician reports, and a database maintained by the state Department of Social Services.

Results

A total of 34 participants did not know whether they had health insurance or did not appear for follow-up assessments at six and 12 months. Among the remaining 48 participants, at baseline 18 had private insurance, 13 had public insurance, and 16 had no insurance. By the 12-month assessment, 13 (72%) privately insured and five (38%) publicly insured participants had lost coverage; less than one-third of the 48 participants (N=14) maintained continuous coverage.

Conclusions

Specialty services for individuals experiencing early psychosis should address the difficulty of maintaining health insurance coverage during a period of illness in which continuity of care is critical to recovery.

Shorter duration of untreated psychosis is associated with better response to treatment (1,2), and specialized early intervention programs have been shown to improve both severity of illness and quality of life (3–5). Together, these findings suggest that increasing individuals’ use of services early in the course of illness may be one key to altering the course of illness.

One modifiable barrier to treatment is lack of health insurance. Being uninsured predicts delayed help seeking following onset of psychosis (6) as well as less use of community mental health treatment and greater likelihood of using only crisis or emergency services (7). In the Suffolk County (New York) Mental Health Project, 44% of patients with a first admission for psychosis were uninsured (8). These patients were less likely to have received prior out-patient treatment and were more likely to be hospitalized involuntarily than those with either public or private insurance.

Health insurance status is not stable over time. Of the Suffolk County patients who initially had private insurance (between 1989 and 1995), 12% had become uninsured and 14% had become publicly insured by two-year follow-up (9). At least one-fourth, therefore, were at risk of experiencing discontinuities in care or disruption of treatment relationships. Similarly, 6% of those who initially had had public insurance had become uninsured by the two-year follow-up. These results, however, do not indicate how many people were uninsured at some point during those two years and, therefore, likely underestimate the frequency of discontinuities in insurance coverage.

Patterns of insurance coverage also likely vary between states, based on differences in regulation of the private market and in public assistance. Two public health insurance programs specific to Connecticut are Healthcare for Uninsured Kids and Youth (HUSKY) and State Administered General Assistance (SAGA) programs.

HUSKY is Connecticut’s two-part health insurance program for low-income children and caregivers. HUSKY A consists of Medicaid coverage for children and adult caregivers in families with income up to 185% of the federal poverty level (FPL). HUSKY B, funded in part by the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), provides subsidized coverage for children whose families’ income is between 185% and 300% of FPL. Families earning more than 300% of FPL may also buy into the program but are not eligible for subsidy (10).

During the study period, SAGA consisted of both a cash assistance program and a medical assistance program and was entirely state funded. The medical assistance program filled an important gap in the medical safety net by covering adults with very low income who were ineligible for Medicaid and Medicare because they did not have children, were not disabled, and were younger than 65. SAGA also acted as a temporary source of insurance for people awaiting determination of their eligibility for Medicaid or Medicare (11). In June 2010, Connecticut transferred SAGA beneficiaries to Medicaid for Low Income Adults, under new guidelines in the federal health care reform act, but continued to restrict eligibility to individuals with incomes of less than 56% to 68% of FPL (12).

In this study, we explored the absence or discontinuity of health insurance coverage among patients being treated early in a first episode of psychosis in Connecticut.

Methods

Data for this study came from Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis (STEP), a program funded by the National Institutes of Health in which patients with early psychosis are randomly assigned either to a specialized early psychosis treatment program at the Connecticut Mental Health Center, to a general psychiatric team at the same center, or to other traditional sources of treatment in the community (13). A total of 82 participants enrolled in STEP between April 2006 and December 2009. The study design was approved by Yale University’s Human Investigations Committee, and participants gave written informed consent to participate in direct research assessments and for the researchers to obtain collateral information from current or former providers and state databases.

Participants’ self-reported insurance information was collected at six-month intervals with an adapted version of the Service Use and Resources Form (SURF) (14) used in the CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) study (15). The original form, which allowed for coding only of private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid, was expanded to include SAGA and HUSKY. Insurance data were also collected retrospectively from participants’ clinical charts, from discussions with their clinicians, and from a Department of Social Services database of enrollment in public insurance during the previous year.

To handle missing data at either six months or 12 months in the time trends analysis, we assumed that participants with insurance had maintained the same coverage unless they were found to have become uninsured.

Results

Insurance data were available at baseline and at six-month or 12-month follow-up or both for 48 of the 82 STEP participants (59%). A total of 14 participants (17%) did not know whether they had insurance, and 20 participants (24%) missed both their six- and 12-month follow-up assessments. The 48 participants had a mean±SD age of 22.2±4.8 years; 43 (90%) were male, and five (10%) were female. A total of 22 (46%) were African American, 18 (38%) were Caucasian, and eight (17%) were Hispanic. Diagnoses consisted of schizophrenia (N=15), schizophreniform disorder (N=11), schizoaffective disorder (N=9), psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (N=6), bipolar disorder (N=6), and delusional disorder (N=1).

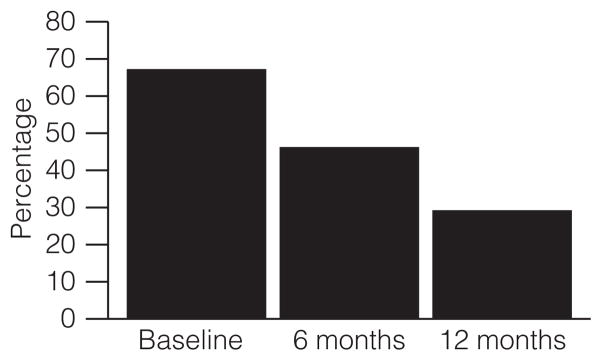

Two-thirds of the 48 participants (N=31) had insurance at baseline, 18 with private insurance and 13 with public insurance. However, fewer than one-third (N=14) maintained continuous insurance coverage throughout the first year of follow-up (Figure 1). Thirteen of the 18 participants (72%) with private insurance at baseline lost it during the first year of follow-up, and only three of them successfully transitioned to public insurance coverage. Of the 13 participants with public insurance at baseline, five (38%) had become uninsured at six or 12 months—two who had been enrolled in HUSKY A or B, two in Medicare, and one in SAGA. Participants’ clinicians attributed this loss of public insurance primarily to aging out of eligibility or failing to renew enrollment.

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants (N=48) in Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis (STEP) with uninterrupted health insurance coverage during follow-up

Nine participants (19%) were incarcerated during the first year of follow-up. Five had private insurance at baseline, and all of them had lost it by six- or 12-month follow-up. The only incarcerated participant with public insurance coverage at baseline had maintained it through the 12-month follow-up. Loss of insurance was not found to correlate with sex, race, or age.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is a striking discontinuity of health insurance coverage, both public and private, early in the course of psychotic illness. Although 67% of the participants for whom longitudinal data were available had insurance at baseline, just 29% at most enjoyed uninterrupted insurance coverage during the first year of follow-up.

Moreover the actual frequency of uninterrupted coverage may have been even lower than the data suggest. By assessing insurance status at discrete time points, we may have missed gaps in coverage between assessments. In addition, participants were presumed to have maintained insurance coverage unless loss of coverage was clearly documented, even if follow-up data were incomplete.

This study did not systematically examine why participants lost insurance, but a variety of causes likely contributed. Participants may have lost employer- or school-based private insurance if they or their parents lost a job, if they withdrew or graduated from college, or if they aged out of their families’ health plans. Those enrolled in HUSKY would have aged out of the program when they reached 19 years of age. Those on SAGA could easily have become ineligible by getting a job, given the very low monthly income limits of $506 to $611, depending on the region of the state (16).

Incarceration may have been another factor related to loss of insurance. All five privately insured participants who were incarcerated during the study period lost their insurance. Many states, including Connecticut, terminate Medicaid benefits upon incarceration (17). However, in Washington and Florida, states whose policies require termination of Medicaid upon incarceration, 97% of people with severe mental illness enrolled in Medicaid upon incarceration were still enrolled upon release, suggesting low enforcement of the policy (17). Even though our sample was too small to draw definitive conclusions, incarceration does not explain the loss of public health insurance experienced by five participants; none of them had been incarcerated over the course of the follow-up period.

National health care reform will likely help to address some, but not all, of the problems (18). People with early psychosis can be expected to have greater access to the private market because insurers will be prohibited from refusing people with preexisting conditions, children will be allowed to remain on their parents’ insurance until age 26, and a wider range of businesses will be required to provide their employees with health benefits. Already national health care reform allows states to extend Medicaid eligibility to all people earning less than 133% of FPL. However, although the state of Connecticut has indeed transferred SAGA enrollees to Medicaid for Low Income Adults, it has continued to impose extremely low income limits of 56% to 68% of FPL (12). Many of the major reforms, moreover, will not take effect until 2014 (19), and it is unclear if they will help address the prolonged interruption of insurance coverage that accompanies job loss.

If, as our findings suggest, a substantial number of people with private insurance become uninsured or publicly insured early in the course of psychotic illness, community mental health centers (CMHCs) should view these privately insured people as potential future clients. Through offering assertive clinical care and case management services, CMHCs may be able to decrease two factors that appear to play a prominent role in loss of private insurance in this population—the loss of employment and the loss of housing when a family decides it can no longer bear the burden of housing and caring for a family member whose symptoms are unmanaged.

There is no simple relationship between category of insurance coverage (public or private) and quality of care received. Nevertheless, changes in coverage early in the course of a psychotic illness may disrupt treatment relationships for those who have engaged with services, at a time when care could be particularly transformative for their long-term prognosis (20). Proactive and early engagement by CMHCs could help minimize disruptions in the care of those who lose private insurance.

The generalizability of this analysis is limited by the small size of our sample compared with the incidence of early psychosis that could be expected in Connecticut during this period. Also, patients who agreed to enroll in STEP may not be representative of all people with first-episode psychosis in the state. Indeed, males and African Americans clearly appeared to be overrepresented in our sample, though loss of insurance was found not to correlate in this sample with sex, race, or age. We attempted to address this limitation by conducting a follow-up study using two databases containing billing records from all of the acute care hospitals in Connecticut, but both prohibit access to patient-level data, making it impossible to track insurance trajectories over time.

We recognize several limitations. Beyond starting with a relatively small pool of participants, the sample was further whittled because 41% of participants either did not know whether they had insurance or missed both the six- and 12-month follow-up assessments. Participants lost to follow up, however, may have been even less likely to have had continuous insurance coverage. In support of this hypothesis, the 31 participants who came for the 12-month assessments were more likely to be insured if they also had attended the six-month assessment, a finding that approached statistical significance. Therefore, we believe that if anything, attrition bias may conceal even greater loss of insurance.

The results from this analysis validate the approach taken by the Connecticut Mental Health Center, which since opening the STEP program in 2006, randomly assigns half its patients in early psychosis with private insurance to receive free public-sector care (13). The goal is to determine whether this proactive model of care, delivered within the resources of a public mental health center, is more cost-effective than usual care in the community. Among other policy goals, the program will explore how partnerships between institutions in the public and private sectors may be used to improve the continuity of care during this critical clinical period.

Conclusions

This study is one of the first to track changes in insurance status early in the course of psychotic illness. Loss of both private and public insurance occurred frequently among these participants. In fact, 71% of participants lacked continuous insurance coverage during their first year of follow-up. Efforts to provide services to individuals early in a psychotic episode must address the reality that health insurance coverage in this population may be interrupted at a critical juncture in treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Connecticut State Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services and grants from the Don-aghue Foundation (DF07-014) and the National Institute of Mental Health (1-RC1-MH088971-01).

Footnotes

disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Dr. Tyler J. Dodds, Email: tyler.dodds@aya.yale.edu, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, 300 George St., Suite 901, New Haven, CT 06511

Dr. Vivek H. Phutane, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, 300 George St., Suite 901, New Haven, CT 06511. Connecticut Mental Health Center in New Haven, as is Mr. Stevens

B. Jamie Stevens, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, 300 George St., Suite 901, New Haven, CT 06511. Connecticut Mental Health Center in New Haven, as is Mr. Stevens

Dr. Scott W. Woods, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, 300 George St., Suite 901, New Haven, CT 06511. Connecticut Mental Health Center in New Haven, as is Mr. Stevens

Dr. Michael J. Sernyak, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, 300 George St., Suite 901, New Haven, CT 06511. Connecticut Mental Health Center in New Haven, as is Mr. Stevens

Dr. Vinod H. Srihari, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, 300 George St., Suite 901, New Haven, CT 06511. Connecticut Mental Health Center in New Haven, as is Mr. Stevens

References

- 1.Perkins D, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1785–1804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, et al. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:975–983. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, et al. A randomized multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. British Medical Journal. 2005;331:602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38565.415000.E01. (Epub) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig T, Garety P, Power P, et al. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialized care for early psychosis. British Medical Journal. 2004;329:1067. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38246.594873.7C. (Epub) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larsen T, Melle I, Auestad B, et al. Early detection of first-episode psychosis: the effect on one-year outcome. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:758–764. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compton M, Ramsay C, Shim R, et al. Health services determinants of the duration of untreated psychosis among African-American first-episode patients. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:1489–1494. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.11.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yanos P, Lu W, Minsky S, et al. Correlates of health insurance among persons with schizophrenia in a statewide behavioral health care system. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:79–82. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabinowitz J, Bromet E, Lavelle J, et al. Relationship between type of insurance and care during the early course of psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1392–1397. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabinowitz J, Bromet E, Lavelle J, et al. Changes in insurance coverage and extent of care during the two years after first hospitalization for a psychotic disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:87–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen RK. HUSKY and Medicaid. Hartford, Conn, State of Connecticut General Assembly: Office of Legislative Research; Nov 20, 2008. Available at www.cga.ct.gov/2008/rpt/2008-R-0615.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reilly M. Health Insurance for Disabled Residents Under Age 65. Hartford, Conn, State of Connecticut General Assembly: Office of Legislative Research; Feb 27, 2008. Available at www.cga.ct.gov/2008/rpt/2008-R-0139.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 12.In Brief: Connecticut’s New Medicaid for Low-Income Adults. Hartford, Conn, State of Connecticut: Department of Social Services; Jun 30, 2010. Available at www.ct.gov/dss/lib/dss/pdfs/brochures/medicaid_lia_in_brief.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srihari V, Breitborde N, Pollard J, et al. Early intervention for psychotic disorders in a community mental health center. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:1426–1428. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.11.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, et al. Multiple outcome assessment in a study of the cost-effectiveness of clozapine in the treatment of refractory schizophrenia: Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Clozapine in Refractory Schizophrenia. Health Services Research. 1998;33:1237–1261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sindelar J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics and perphenazine in a randomized trial of treatment for chronic schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:2080–2089. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.State Administered General Assistance (SAGA) Hartford, Conn, State of Connecticut: Department of Social Services; Jun 25, 2010. Available at www.ct.gov/dss/cwp/view.asp?a=2353&q=305152#SAG. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrissey J, Dalton K, Steadman H, et al. Assessing gaps between policy and practice in Medicaid disenrollment of jail detainees with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:803–808. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman HH. Will health insurance reform in the United States help people with schizophrenia? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:893–894. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aaron H, Reischauer R. The war isn’t over. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362:1259–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1003394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birchwood M, Todd P, Jackson C. Early intervention in psychosis: the critical period hypothesis. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement. 1998;172:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]