Abstract

Longitudinal research suggests that efforts at the national, state, and local levels are leading to improved follow-up and data reporting. Data now support the assumption that the number of deaf or hard-of-hearing infants identified through newborn hearing screening increases with a reduction in the number of infants lost to follow-up. Documenting the receipt of services has made a noticeable impact on reducing lost to follow-up rates and early identification of infants with hearing loss; however, continued improvement and monitoring of services are still needed.

Keywords: audiology, diagnostic evaluation, follow-up, EHDI, hearing loss, hearing screening, intervention, lost to documentation, lost to follow-up

Hearing is critical for speech, language, social, and emotional development. Consequently, undetected hearing loss among infants increases the chance for developmental delays. The average age of hearing loss identification in the United States is close to 3 years, which typically constitutes the most important period for language and speech development.1 This has led nationally recognized organizations to recommend hearing screening for all newborns. This includes the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, whose members include national professional and advocacy organizations.2 The US Preventive Services Task Force also recommends screening for hearing loss in all newborn infants (grade B).3 In addition, hearing screening is also included as one of the core conditions of Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children Recommended Uniform Screening Panel.4 Every US state, territory, freely associated state, and the District of Columbia has implemented an Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) program to ensure the identification of hearing loss in infants as soon as possible. These public health programs are largely based on the EHDI “1-3-6” plan, consisting of 3 core national goals: (1) screening all infants no later than 1 month of age, (2) ensuring diagnostic audiological evaluation no later than 3 months of age for those who do not pass the screening, and (3) enrolling infants identified with hearing loss in early intervention services no later than 6 months of age. To monitor progress of identifying infants with hearing loss and provide recommended services in accordance with the “1-3-6” plan, EHDI programs need hospitals, audiologists, interventionists, and other providers to consistently report accurate and complete information. According to data submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than 3.7 million infants born in calendar year (CY) 2011 in the United States were screened for hearing loss and more than 94% of these infants were documented as being screened before 1 month of age.5

Typically, hospital-based newborn hearing screening programs report results to the jurisdictional EHDI program on a consistent basis; however, the same is not true for diagnostic audiological evaluations. National estimates based on CY 2011 data indicate that approximately 35% of infants failing their hearing screening are not confirmed as having received the recommended audiological evaluation needed to diagnose a hearing loss by 3 months of age. It is unclear whether these infants have been seen by an audiologist or whether the results are not being reported to the jurisdictional EHDI program. Infants referred for testing who do not receive it and cannot be contacted by the EHDI program are commonly classified as lost to follow-up (LFU). Infants who did receive the recommended follow-up testing but the results were never reported to the EHDI program are referred to as lost to documentation (LTD). Because it is typically not possible for EHDI programs to differentiate between those infants who were LFU and those who were LTD, both terms are used together.

As part of the national effort to identify infants with hearing loss, the CDC, the Health Resources and Service Administration, and the American Academy of Pediatrics have each established EHDI initiatives. The CDC currently provides funding to 52 jurisdictions to develop and enhance EHDI information systems that are capable of capturing and reporting accurate screening and follow-up data on all occurrent births. These systems are used by programs to help ensure infants receive recommended services and assess progress toward national goals. The Health Resources and Service Administration provides grant funds to jurisdictions to help them reduce their levels of LFU/LTD and has also engaged the National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality to work directly with EHDI programs. Since 2007, the National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality has conducted a series of collaborative improvement projects to help jurisdictions identify best practices to improve the delivery and documentation of services. Among the practices developed and implemented by participating jurisdictions are routine communication of results and recommendations among all EHDI stakeholders and having the birth facility make an appointment for any recommended follow-up testing before an infant is discharged.6 In addition, the American Academy of Pediatrics established the Task Force on Improving the Effectiveness of Newborn Hearing Screening, Diagnosis and Intervention, which focuses on increasing the involvement of primary care pediatricians and other providers by linking EHDI follow-up services more closely to an infant’s medical home.7

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to analyze data to determine what, if any, association there is between the number of infants reported as LFU/LTD in the years 2005-2011 and the number of infants who are deaf or hard of hearing identified during the same period.

Methods

The CDC EHDI program collects data through the Hearing Screening and Follow-up Survey (HSFS), which is an annual, online survey approved by the US Office of Management and Budget, administered by the CDC, and sent to the EHDI Program coordinator in each US state, territory, freely associated state, and the District of Columbia. The HSFS requests aggregate, nonestimated information related to the receipt of hearing screening, diagnostic testing, and enrollment in early intervention for every occurrent birth within a jurisdiction. Error checks are included in the online survey to help avoid over- and underreporting. This survey has been used to collect data for the years 2005-2011, and it consists of 3 parts. Part 1 requests information on screening, diagnosis, and intervention. Part 2 requests data about the type and severity of all permanent cases of diagnosed hearing loss. Part 3 requests aggregate demographic data for selected items reported in part 1. The survey requires respondents to account for the screening, diagnostic, and intervention status for all infants reported in the survey. Part 1 was the primary focus for this study. Data for parts 2 and 3 are available online at: www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/ehdi-data.html

The HSFS has made it possible to assess how many infants not passing the final or most recent hearing screening are documented to have received follow-up services (ie, diagnostic evaluation and intervention services) and how many are LFU/LTD. The percentage of LFU/LTD in each reporting year was calculated by dividing the number of infants not receiving a diagnosis for the reasons unable to contact the parents or family, contact made but the family is unresponsive, or unknown by the total number of infants failing their hearing screening.8 Results from the HSFS for the years 2005-2011 were captured in a Microsoft Access database and then exported into Microsoft Excel. The data were reviewed by the CDC EHDI program staff to ensure accuracy and completion. Microsoft Excel and SAS 9.3 software programs were used for analysis. Data for each year were compared at the national level. Although the number of respondents varied each year from 44 to 52, weighting was not included in the analysis because the small differences would not significantly affect the results. The differences were still accounted for in the calculations for key indicators (eg, LFU/LTD) by basing the denominator on the number of total occurrent births for participating EHDI jurisdictions, instead of the total number of occurrent births in the United States for that year.

Outcomes

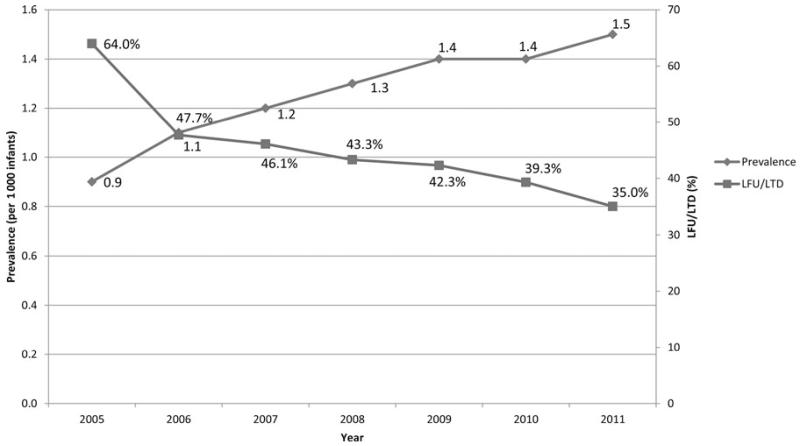

In CY 2005, 44 EHDI jurisdictions reported both screening and diagnostic data, which indicated that 93.7% (2 873 468 newborns) were screened for hearing loss. Over the next 6 years, the number of jurisdictions submitting data increased, with a corresponding increase in the percentage screened to 97.8% (3 416 085 infants) in CY 2011. During this 6-year period, the number of infants identified with a permanent hearing loss increased by more than 93% from 2634 in CY 2005 to 5118 in CY 2011. At the same time, the rate of infants LFU/LTD during this same period decreased from 2 of 3 (64.0%) to nearly 1 of 3 (35.0%). The Figure illustrates the strong inverse correlation between the percentage LFU/LTD and the prevalence of permanent hearing loss per 1000 infants screened between 2005 and 2011 (coefficient = −0.78).

FIGURE. Prevalence of Infants Identified With Hearing Loss and Lost to Follow-up/Documentation, United States, 2005-2011.

LFU indicates lost to follow-up; LTD, lost to documentation.

Discussion

The findings in this article are subject to at least 3 limitations. First, some jurisdictions did not respond to the HSFS in each year. Second, it is possible that some jurisdictions did not follow the guidance for the HSFS, which may have affected the comparability of some LFU/LTD data. Third, actual LFU/LTD rates may be lower than reported, as these depend on confirmed diagnostic results, which may not have been reported to the EHDI program.

These findings indicate that notable progress has been made in both identifying infants with hearing loss and decreasing the percentage of LFU/LTD. The 35% of infants still LFU/LTD in 2011 clearly highlights the need for further improvements in the standardization, collection, and reporting of EHDI information. Without documentation of follow-up diagnostic services, the benefits of newborn hearing screening may not be accurately evaluated.9 Incomplete reporting of all confirmatory test results to the EHDI program, including ongoing diagnostic evaluations and monitoring, also diverts valuable resources needed to assist children who have yet to receive recommended services, which, in turn, increases chance for developmental delays. The continued adoption of best practices and helping families understand the importance of the early identification of hearing loss are essential for the future success of deaf or hard-of-hearing infants and EHDI programs.

Footnotes

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Office of Disease Prevention. National Institute of Health Early identification of hearing impairment in infants and young children. NIH Consens Statement. 1993;11(1):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing Year 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120:898–921. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Preventive Services Task Force Universal screening for hearing loss in newborns: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2008;122:143–148. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children [Accessed December 19, 2012]; www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/mchbadvisory/heritabledisorders/recommendedpanel/uniformscreeningpanel.pdf.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed May 8, 2013];Annual data Early Hearing Detection and Intervention program. www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/ehdi-data.html.

- 6.National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality [Accessed December 17, 2012];IH-SIS: Improving Hearing Screening and Intervention Systems. www.nichq.org/our_projects/newborn_hearing.html.

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics [Accessed May 9, 2013];Taskforce on Improving the Effectiveness of Newborn Hearing Screening, Diagnosis, and Intervention Strategic Plan. http://www.medicalhomeinfo.org/downloads/pdfs/AAP_EHDI_Strategic_Plan.pdf.

- 8.Mason CA, Gaffney M, Green DR, Grosse SD. Measures of follow-up in early hearing detection and intervention programs: a need for standardization. Am J Audiol. 2008;17:60–67. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2008/007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaffney M, Green D, Gaffney C. Newborn Hearing Screening and Follow-up: are children receiving recommended services? Public Health Rep. 2010;125:199–207. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]